| Issue |

A&A

Volume 674, June 2023

Gaia Data Release 3

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A38 | |

| Number of page(s) | 50 | |

| Section | Galactic structure, stellar clusters and populations | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202243511 | |

| Published online | 16 June 2023 | |

Gaia Data Release 3

Chemical cartography of the Milky Way

1

Université Côte d’Azur, Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur, CNRS, Laboratoire Lagrange, Bd de l’Observatoire, CS 34229, 06304 Nice Cedex 4, France

2

INAF – Osservatorio Astrofisico di Torino, Via Osservatorio 20, 10025 Pino Torinese (TO), Italy

3

INAF – Osservatorio astronomico di Padova, Vicolo Osservatorio 5, 35122 Padova, Italy

4

GEPI, Observatoire de Paris, Université PSL, CNRS, 5 Place Jules Janssen, 92190 Meudon, France

5

Lund Observatory, Department of Astronomy and Theoretical Physics, Lund University, Box 43 22100 Lund, Sweden

6

University of Turin, Department of Physics, Via Pietro Giuria 1, 10125 Torino, Italy

7

Mullard Space Science Laboratory, University College London, Holmbury St Mary, Dorking, Surrey RH5 6NT, UK

8

Laboratoire d’astrophysique de Bordeaux, Univ. Bordeaux, CNRS, B18N, allée Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 33615 Pessac, France

9

INAF – Osservatorio di Astrofisica e Scienza dello Spazio di Bologna, Via Piero Gobetti 93/3, 40129 Bologna, Italy

10

Institut de Ciències del Cosmos (ICCUB), Universitat de Barcelona (IEEC-UB), Martí i Franquès 1, 08028 Barcelona, Spain

11

Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Knigstuhl 17, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany

12

Observational Astrophysics, Division of Astronomy and Space Physics, Department of Physics and Astronomy, Uppsala University, Box 516 751 20 Uppsala, Sweden

13

Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, Niels Bohrweg 2, 2333 CA Leiden, The Netherlands

14

European Space Agency (ESA), European Space Research and Technology Centre (ESTEC), Keplerlaan 1, 2201 AZ Noordwijk, The Netherlands

15

Univ. Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, IPAG, 38000 Grenoble, France

16

Astronomisches Rechen-Institut, Zentrum für Astronomie der Universität Heidelberg, Mönchhofstr. 12-14, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany

17

Institute of Astronomy, University of Cambridge, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0HA, UK

18

Department of Astronomy, University of Geneva, Chemin Pegasi 51, 1290 Versoix, Switzerland

19

European Space Agency (ESA), European Space Astronomy Centre (ESAC), Camino bajo del Castillo, s/n, Urbanizacion Villafranca del Castillo, Villanueva de la Cañada 28692 Madrid, Spain

20

Aurora Technology for European Space Agency (ESA), Camino bajo del Castillo, s/n, Urbanizacion Villafranca del Castillo, Villanueva de la Cañada, 28692 Madrid, Spain

21

Lohrmann Observatory, Technische Universität Dresden, Mommsenstraße 13, 01062 Dresden, Germany

22

CNES Centre Spatial de Toulouse, 18 avenue Edouard Belin, 31401 Toulouse Cedex 9, France

23

Institut d’Astronomie et d’Astrophysique, Université Libre de Bruxelles CP 226, Boulevard du Triomphe, 1050 Brussels, Belgium

24

F.R.S.-FNRS, Rue d’Egmont 5, 1000 Brussels, Belgium

25

INAF – Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri, Largo Enrico Fermi 5, 50125 Firenze, Italy

26

European Space Agency (ESA), Noordwijk, The Netherlands

27

DAPCOM for Institut de Ciències del Cosmos (ICCUB), Universitat de Barcelona (IEEC-UB), Martí i Franquès 1, 08028 Barcelona, Spain

28

Royal Observatory of Belgium, Ringlaan 3, 1180 Brussels, Belgium

29

ALTEC S.p.a, Corso Marche, 79, 10146 Torino, Italy

30

Sednai Sàrl, Geneva, Switzerland

31

Department of Astronomy, University of Geneva, Chemin d’Ecogia 16, 1290 Versoix, Switzerland

32

Gaia DPAC Project Office, ESAC, Camino bajo del Castillo, s/n, Urbanizacion Villafranca del Castillo, Villanueva de la Cañada, 28692 Madrid, Spain

33

Telespazio UK S.L. for European Space Agency (ESA), Camino bajo del Castillo, s/n, Urbanizacion Villafranca del Castillo, Villanueva de la Cañada, 28692 Madrid, Spain

34

SYRTE, Observatoire de Paris, Université PSL, CNRS, Sorbonne Université, LNE, 61 avenue de l’Observatoire, 75014 Paris, France

35

National Observatory of Athens, I. Metaxa and Vas. Pavlou, Palaia Penteli, 15236 Athens, Greece

36

IMCCE, Observatoire de Paris, Université PSL, CNRS, Sorbonne Université, Univ. Lille, 77 av. Denfert-Rochereau, 75014 Paris, France

37

Serco Gestión de Negocios for European Space Agency (ESA), Camino bajo del Castillo, s/n, Urbanizacion Villafranca del Castillo, Villanueva de la Cañada, 28692 Madrid, Spain

38

Institut d’Astrophysique et de Géophysique, Université de Liège, 19c, Allée du 6 Août, 4000 Liège, Belgium

39

CRAAG – Centre de Recherche en Astronomie, Astrophysique et Géophysique, Route de l’Observatoire, BP 63 Bouzareah, 16340 Algiers, Algeria

40

Institute for Astronomy, University of Edinburgh, Royal Observatory, Blackford Hill, Edinburgh EH9 3HJ, UK

41

RHEA for European Space Agency (ESA), Camino bajo del Castillo, s/n, Urbanizacion Villafranca del Castillo, Villanueva de la Cañada, 28692 Madrid, Spain

42

ATG Europe for European Space Agency (ESA), Camino bajo del Castillo, s/n, Urbanizacion Villafranca del Castillo, Villanueva de la Cañada, 28692 Madrid, Spain

43

CIGUS CITIC – Department of Computer Science and Information Technologies, University of A Coruña, Campus de Elviña s/n, A Coruña 15071, Spain

44

Université de Strasbourg, CNRS, Observatoire astronomique de Strasbourg, UMR 7550, 11 rue de l’Université, 67000 Strasbourg, France

45

Kavli Institute for Cosmology Cambridge, Institute of Astronomy, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0HA, UK

46

Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam (AIP), An der Sternwarte 16, 14482 Potsdam, Germany

47

CENTRA, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa, Edif. C8, Campo Grande, 1749-016 Lisboa, Portugal

48

Department of Informatics, Donald Bren School of Information and Computer Sciences, University of California, Irvine, 5226 Donald Bren Hall, 92697-3440 CA, Irvine, USA

49

INAF – Osservatorio Astrofisico di Catania, Via S. Sofia 48, 95123 Catania, Italy

50

Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia “Ettore Majorana”, Università di Catania, Via S. Sofia 64, 95123 Catania, Italy

51

INAF – Osservatorio Astronomico di Roma, Via Frascati 33, 00048 Monte Porzio Catone (Roma), Italy

52

Space Science Data Center – ASI, Via del Politecnico SNC, 00133 Roma, Italy

53

Department of Physics, University of Helsinki, PO Box 64 00014 Helsinki, Finland

54

Finnish Geospatial Research Institute FGI, Geodeetinrinne 2, 02430 Masala, Finland

55

Institut UTINAM CNRS UMR6213, Université Bourgogne Franche-Comté, OSU THETA Franche-Comté Bourgogne, Observatoire de Besançon, BP1615, 25010 Besançon Cedex, France

56

HE Space Operations BV for European Space Agency (ESA), Keplerlaan 1, 2201 AZ Noordwijk, The Netherlands

57

Dpto. de Inteligencia Artificial, UNED, c/ Juan del Rosal 16, 28040 Madrid, Spain

58

Konkoly Observatory, Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences, Eötvs Loránd Research Network (ELKH), MTA Centre of Excellence, Konkoly Thege Miklós út 15-17, 1121 Budapest, Hungary

59

ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, Institute of Physics, 1117, Pázmány Péter sétány 1A, Budapest, Hungary

60

Instituut voor Sterrenkunde, KU Leuven, Celestijnenlaan 200D, 3001 Leuven, Belgium

61

Department of Astrophysics/IMAPP, Radboud University, PO Box 9010 6500 GL Nijmegen, The Netherlands

62

University of Vienna, Department of Astrophysics, Türkenschanzstraße 17, 1180 Vienna, Austria

63

Institute of Physics, Laboratory of Astrophysics, Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Observatoire de Sauverny, 1290 Versoix, Switzerland

64

Kapteyn Astronomical Institute, University of Groningen, Landleven 12, 9747 AD Groningen, The Netherlands

65

School of Physics and Astronomy / Space Park Leicester, University of Leicester, University Road, Leicester LE1 7RH, UK

66

Thales Services for CNES Centre Spatial de Toulouse, 18 avenue Edouard Belin, 31401 Toulouse Cedex 9, France

67

Depto. Estadística e Investigación Operativa. Universidad de Cádiz, Avda. República Saharaui s/n, 11510 Puerto Real, Cádiz, Spain

68

Center for Research and Exploration in Space Science and Technology, University of Maryland Baltimore County, 1000 Hilltop Circle, Baltimore, MD, USA

69

GSFC – Goddard Space Flight Center, Code 698, 8800 Greenbelt Rd, 20771 MD Greenbelt, USA

70

EURIX S.r.l., Corso Vittorio Emanuele II 61, 10128 Torino, Italy

71

Porter School of the Environment and Earth Sciences, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv 6994801, Israel

72

Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden St., MS 15, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA

73

HE Space Operations BV for European Space Agency (ESA), Camino bajo del Castillo, s/n, Urbanizacion Villafranca del Castillo, Villanueva de la Cañada, 28692 Madrid, Spain

74

Instituto de Astrofísica e Ciências do Espaço, Universidade do Porto, CAUP, Rua das Estrelas, 4150-762 Porto, Portugal

75

LFCA/DAS, Universidad de Chile, CNRS, Casilla 36-D, Santiago, Chile

76

SISSA – Scuola Internazionale Superiore di Studi Avanzati, Via Bonomea 265, 34136 Trieste, Italy

77

Telespazio for CNES Centre Spatial de Toulouse, 18 avenue Edouard Belin, 31401 Toulouse Cedex 9, France

78

University of Turin, Department of Computer Sciences, Corso Svizzera 185, 10149 Torino, Italy

79

Dpto. de Matemática Aplicada y Ciencias de la Computación, Univ. de Cantabria, ETS Ingenieros de Caminos, Canales y Puertos, Avda. de los Castros s/n, 39005 Santander, Spain

80

Centro de Astronomía – CITEVA, Universidad de Antofagasta, Avenida Angamos 601, Antofagasta 1270300, Chile

81

DLR Gesellschaft für Raumfahrtanwendungen (GfR) mbH, Münchener Straße 20, 82234 Weßling, Germany

82

Centre for Astrophysics Research, University of Hertfordshire, College Lane, AL10 9AB Hatfield, UK

83

University of Turin, Mathematical Department “G.Peano”, Via Carlo Alberto 10, 10123 Torino, Italy

84

INAF – Osservatorio Astronomico d’Abruzzo, Via Mentore Maggini, 64100 Teramo, Italy

85

Instituto de Astronomia, Geofìsica e Ciências Atmosféricas, Universidade de São Paulo, Rua do Matão, 1226, Cidade Universitaria, 05508-900 São Paulo, SP, Brazil

86

APAVE SUDEUROPE SAS for CNES Centre Spatial de Toulouse, 18 avenue Edouard Belin, 31401 Toulouse Cedex 9, France

87

Mésocentre de calcul de Franche-Comté, Université de Franche-Comté, 16 route de Gray, 25030 Besançon Cedex, France

88

Theoretical Astrophysics, Division of Astronomy and Space Physics, Department of Physics and Astronomy, Uppsala University, Box 516 751 20 Uppsala, Sweden

89

ATOS for CNES Centre Spatial de Toulouse, 18 avenue Edouard Belin, 31401 Toulouse Cedex 9, France

90

School of Physics and Astronomy, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv 6994801, Israel

91

Astrophysics Research Centre, School of Mathematics and Physics, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast BT7 1NN, UK

92

Centre de Données Astronomique de Strasbourg, Strasbourg, France

93

Institute for Computational Cosmology, Department of Physics, Durham University, Durham DH1 3LE, UK

94

European Southern Observatory, Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 2, 85748 Garching, Germany

95

Max-Planck-Institut für Astrophysik, Karl-Schwarzschild-Straße 1, 85748 Garching, Germany

96

Data Science and Big Data Lab, Pablo de Olavide University, 41013 Seville, Spain

97

Barcelona Supercomputing Center (BSC), Plaça Eusebi Güell 1-3, 08034 Barcelona, Spain

98

ETSE Telecomunicación, Universidade de Vigo, Campus Lagoas-Marcosende, 36310 Vigo, Galicia, Spain

99

Asteroid Engineering Laboratory, Space Systems, Luleå University of Technology, Box 848 981 28 Kiruna, Sweden

100

Vera C Rubin Observatory, 950 N. Cherry Avenue, Tucson, AZ 85719, USA

101

Department of Astrophysics, Astronomy and Mechanics, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Panepistimiopolis, Zografos, 15483 Athens, Greece

102

TRUMPF Photonic Components GmbH, Lise-Meitner-Straße 13, 89081 Ulm, Germany

103

IAC – Instituto de Astrofisica de Canarias, Via Láctea s/n, 38200 La Laguna S.C., Tenerife, Spain

104

Department of Astrophysics, University of La Laguna, Via Láctea s/n, 38200 La Laguna S.C., Tenerife, Spain

105

Faculty of Aerospace Engineering, Delft University of Technology, Kluyverweg 1, 2629 HS Delft, The Netherlands

106

Radagast Solutions, Simon Vestdijkpad 24, 2321WD Leiden, The Netherlands

107

Laboratoire Univers et Particules de Montpellier, CNRS Université Montpellier, Place Eugène Bataillon, CC72, 34095 Montpellier Cedex 05, France

108

Université de Caen Normandie, Côte de Nacre, Boulevard Maréchal Juin, 14032 Caen, France

109

LESIA, Observatoire de Paris, Université PSL, CNRS, Sorbonne Université, Université de Paris, 5 Place Jules Janssen, 92190 Meudon, France

110

SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research, Niels Bohrweg 4, 2333 CA Leiden, The Netherlands

111

Astronomical Observatory, University of Warsaw, Al. Ujazdowskie 4, 00-448 Warszawa, Poland

112

Scalian for CNES Centre Spatial de Toulouse, 18 avenue Edouard Belin, 31401 Toulouse Cedex 9, France

113

Université Rennes, CNRS, IPR (Institut de Physique de Rennes) – UMR 6251, 35000 Rennes, France

114

INAF – Osservatorio Astronomico di Capodimonte, Via Moiariello 16, 80131 Napoli, Italy

115

Shanghai Astronomical Observatory, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 80 Nandan Road, Shanghai 200030, PR China

116

University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, No.19(A) Yuquan Road, Shijingshan District, Beijing 100049, PR China

117

Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen, Juliane Maries Vej 30, 2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark

118

DXC Technology, Retortvej 8, 2500 Valby, Denmark

119

Las Cumbres Observatory, 6740 Cortona Drive Suite 102, Goleta, CA 93117, USA

120

CIGUS CITIC, Department of Nautical Sciences and Marine Engineering, University of A Coruña, Paseo de Ronda 51, 15071 A Coruña, Spain

121

Astrophysics Research Institute, Liverpool John Moores University, 146 Brownlow Hill, Liverpool L3 5RF, UK

122

IPAC, Mail Code 100-22, California Institute of Technology, 1200 E. California Blvd., Pasadena, CA 91125, USA

123

IRAP, Université de Toulouse, CNRS, UPS, CNES, 9 Av. Colonel Roche, BP 44346, 31028 Toulouse Cedex 4, France

124

MTA CSFK Lendlet Near-Field Cosmology Research Group, Konkoly Observatory, MTA Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences, Konkoly Thege Miklós út 15-17, 1121 Budapest, Hungary

125

Departmento de Física de la Tierra y Astrofísica, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, 28040 Madrid, Spain

126

Ruđer Bošković Institute, Bijenička cesta 54, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia

127

Villanova University, Department of Astrophysics and Planetary Science, 800 E Lancaster Avenue, Villanova, PA 19085, USA

128

INAF – Osservatorio Astronomico di Brera, Via E. Bianchi, 46, 23807 Merate (LC), Italy

129

STFC, Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, Harwell, Didcot OX11 0QX, UK

130

Charles University, Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Astronomical Institute of Charles University, V Holesovickach 2, 18000 Prague, Czech Republic

131

Department of Particle Physics and Astrophysics, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot 7610001, Israel

132

Department of Astrophysical Sciences, 4 Ivy Lane, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA

133

Departamento de Astrofísica, Centro de Astrobiología (CSIC-INTA), ESA-ESAC. Camino Bajo del Castillo s/n., 28692 Villanueva de la Cañada, Madrid, Spain

134

naXys, University of Namur, Rempart de la Vierge, 5000 Namur, Belgium

135

CGI Deutschland B.V. & Co. KG, Mornewegstr. 30, 64293 Darmstadt, Germany

136

Institute of Global Health, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland

137

Astronomical Observatory Institute, Faculty of Physics, Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland

138

H H Wills Physics Laboratory, University of Bristol, Tyndall Avenue, Bristol BS8 1TL, UK

139

Department of Physics and Astronomy G. Galilei, University of Padova, Vicolo dell’Osservatorio 3, 35122 Padova, Italy

140

CERN, Esplanade des Particules 1, PO Box 1211 Geneva, Switzerland

141

Applied Physics Department, Universidade de Vigo, 36310 Vigo, Spain

142

Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, 1331 Pennsylvania Ave. NW, Washington, DC 20004, USA

143

European Southern Observatory, Alonso de Córdova 3107, Casilla 19, Santiago, Chile

144

Sorbonne Université, CNRS, UMR7095, Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris, 98bis bd. Arago, 75014 Paris, France

145

Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, University of Ljubljana, Jadranska ulica 19, 1000 Ljubljana, Slovenia

Received:

9

March

2022

Accepted:

25

May

2022

Context. The motion of stars has been used to reveal details of the complex history of the Milky Way, in constant interaction with its environment. Nevertheless, to reconstruct the Galactic history puzzle in its entirety, the chemo-physical characterisation of stars is essential. Previous Gaia data releases were supported by a smaller, heterogeneous, and spatially biased mixture of chemical data from ground-based observations.

Aims. Gaia Data Release 3 opens a new era of all-sky spectral analysis of stellar populations thanks to the nearly 5.6 million stars observed by the Radial Velocity Spectrometer (RVS) and parametrised by the GSP-Spec module. In this work, we aim to demonstrate the scientific quality of Gaia’s Milky Way chemical cartography through a chemo-dynamical analysis of disc and halo populations.

Methods. Stellar atmospheric parameters and chemical abundances provided by Gaia DR3 spectroscopy are combined with DR3 radial velocities and EDR3 astrometry to analyse the relationships between chemistry and Milky Way structure, stellar kinematics, and orbital parameters.

Results. The all-sky Gaia chemical cartography allows a powerful and precise chemo-dynamical view of the Milky Way with unprecedented spatial coverage and statistical robustness. First, it reveals the strong vertical symmetry of the Galaxy and the flared structure of the disc. Second, the observed kinematic disturbances of the disc – seen as phase space correlations – and kinematic or orbital substructures are associated with chemical patterns that favour stars with enhanced metallicities and lower [α/Fe] abundance ratios compared to the median values in the radial distributions. This is detected both for young objects that trace the spiral arms and older populations. Several α, iron-peak elements and at least one heavy element trace the thin and thick disc properties in the solar cylinder. Third, young disc stars show a recent chemical impoverishment in several elements. Fourth, the largest chemo-dynamical sample of open clusters analysed so far shows a steepening of the radial metallicity gradient with age, which is also observed in the young field population. Finally, the Gaia chemical data have the required coverage and precision to unveil galaxy accretion debris and heated disc stars on halo orbits through their [α/Fe] ratio, and to allow the study of the chemo-dynamical properties of globular clusters.

Conclusions. Gaia DR3 chemo-dynamical diagnostics open new horizons before the era of ground-based wide-field spectroscopic surveys. They unveil a complex Milky Way that is the outcome of an eventful evolution, shaping it to the present day.

Key words: Galaxy: abundances / stars: abundances / Galaxy: evolution / Galaxy: kinematics and dynamics / Galaxy: disk / Galaxy: halo

© The Authors 2023

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. Subscribe to A&A to support open access publication.

1. Introduction

The European Space Agency Gaia mission has transformed our understanding of the Milky Way, thanks to its ability to trace the motion of stars in the sky (Gaia Collaboration 2023a). The observation of these movements has allowed us to see the Galaxy as an evolving system. Components that were previously thought to be distinct (the thin disc in the Galactic plane with ongoing star formation, the more diffuse and older thick disc, the central bulge, and the extended stellar halo) now appear to be interlinked formation phases of a system in clear interaction with its environment. In particular, studies of stellar orbits and kinematics have uncovered a considerable proportion of merger debris in the halo (e.g. Helmi et al. 2018; Belokurov et al. 2018; Malhan et al. 2018; Myeong et al. 2019; Helmi 2020, and references therein) and the Galactic disc (e.g. Sestito et al. 2020; Re Fiorentin et al. 2021). Additionally, investigations of stellar motions have revealed the Galactic disc phase mixing process, which is subsequent to a mildly disturbed state (Antoja et al. 2018). A massive disc-crossing perturber (e.g. Binney & Schönrich 2018) – possibly akin to the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy (Laporte et al. 2019a; Bland-Hawthorn et al. 2019) – or a strong buckling of the stellar bar (e.g. Khoperskov et al. 2020) are the most likely interpretations of this phenomenon. A recent or ongoing encounter with a satellite galaxy seems also to be responsible for the rapidly precessing disc warp (Poggio et al. 2020, 2021a). In summary, the picture of a ‘living and breathing Galaxy’ has emerged thanks to Gaia data (Belokurov 2019; Brown 2021).

Despite the above-mentioned transformational results, stellar motions alone do not allow a complete reconstruction of the intricate puzzle of Galactic history. The orbit of a star evolves in response to fluctuations in the Galaxy’s gravitational field (e.g. Sellwood & Binney 2002). As a consequence, the reconstruction of the history of the Milky Way based on the interpretation of stellar motions in terms of evolutionary processes is hampered by degenerate explanations and the complex interplay of different physical mechanisms.

Indeed, understanding how galaxies like the Milky Way form and evolve remains a challenge. In the cold dark matter Universe, galaxies grow through a sequence of merger and accretion events. However, the impact of these events on the evolution of a galaxy is extremely difficult to predict because of the complex physics of baryons. As a consequence, studying the chemo-physical properties of matter is essential to comprehend the Galaxy in which we live. Fortunately, we have a powerful tool at our disposal: stellar spectroscopy.

The study of stellar spectra gave rise to the science of astrophysics in the 19th century (e.g. Huggins & Miller 1864; Huggins & Huggins 1899) and, since then, the varying characteristics of spectral absorption lines have been used by researchers to decipher the physical properties of stars (Maury & Pickering 1897; Cannon & Pickering 1918). Stellar parametrisation became a powerful decryption tool, allowing us to unveil the chemical composition of stellar atmospheres (Payne 1925a,b), and to provide observational evidence of the stellar nucleosynthesis theory (Burbidge et al. 1957). Stars form during the collapse of molecular clouds of gas and dust. Like alchemists, stars of different masses synthesise all chemical elements except hydrogen1; they partially return them in the later stages of their life into the interstellar medium, from which new stars are born. As a consequence, the stellar chemical composition evolves from one generation to the next, and reflects the gas conditions at the time and place of the formation of a star. Moreover, contrary to stellar motions, the chemical abundances of a star’s atmosphere are conserved2 from its birth, and can therefore be used to trace its origin. Chemical abundances break degenerated dynamical scenarios with a variety of conserved parameters (e.g. they play a key role in merger debris studies; e.g. Helmi 2020). Therefore, stellar atmospheres record the past in their chemical abundances, allowing a look-back time that varies between a few hundred million years and the age of the first stars in the Universe.

In this framework, previous intermediate Gaia data releases had to be complemented with chemical data from ground-based observations. However, ground-based spectroscopic surveys like GALAH (e.g. Buder et al. 2021), APOGEE (Abdurro’uf et al. 2022), Gaia-ESO Survey (Gilmore et al. 2022; Randich et al. 2022), and RAVE (Steinmetz et al. 2020), despite the recent improvement of multiplex capabilities, are still hampered by spatially biased samples. In addition, the inhomogeneity induced by different analysis procedures, targeted stellar types, and spectral configurations blur the collected chemical information. Moreover, ground-based spectroscopy suffers from time-dependent effects such as the Earth’s atmospheric absorption and instrumental systematic effects, which are difficult to model with discontinuous data collections.

Fortunately, the context is now evolving favourably. Gaia Data Release 3 (DR3; Gaia Collaboration 2023c) opens a new era of all-sky spectroscopy and chemo-physical characterisation of Galactic stellar populations, and includes a new transformational data set that confirms Gaia’s leading role in the golden age of Galactic archaeology: the largest homogeneous spectral analysis performed so far with a total of 5 594 205 stars observed by the Radial Velocity Spectrometer (RVS; Cropper et al. 2018; Katz et al. 2023) and parametrised by the General Stellar Parametriser - spectroscopy (GSP-Spec; Recio-Blanco et al. 2023). With continuous data collection for 34 months outside the Earth’s atmosphere, and a large volume coverage reaching distances of about 8 kpc from the Sun (thanks to the population of giant stars), the Gaia DR3 spectroscopic survey provides stellar parameters and chemical abundances in all major Galactic populations, sharpening our global view of the Milky Way. In addition to the sky coverage advantage, it is worth comparing this Gaia DR3 GSP-Spec catalogue with high-resolution ground-based surveys in other crucial characteristics for Milky Way studies, as the number of analysed stars, the limiting magnitude, and the explored chemical diagnostics. For magnitudes brighter than G = 13.63, there are more stars in the Gaia DR3 GSP-Spec catalogue than in any other ground-based survey (with both GALAH and APOGEE representing only ∼8% of Gaia GSP-Spec). For magnitudes fainter than 13.6, Gaia GSP-Spec has about 61 000 stars (reaching G = 16.1 mag), GALAH has about 130 000 stars (20% of the survey, reaching G = 18 mag) and APOGEE about 314 000 stars (43% of the survey, reaching G ≃ 20 mag). Concerning the nucleosynthesis diagnostics4 through individual abundance estimates, Gaia DR3 GSP-Spec explores five different nucleosynthetic channels with 13 chemical elements, while GALAH covers seven nucleosynthetic channels with 21 elements, and APOGEE six channels with 24 elements.

The goal of this paper is to demonstrate the scientific quality of Gaia’s chemical cartography through a chemo-dynamical analysis of disc and halo populations. To this purpose, Sect. 2 presents the data that are used, including (i) DR3 atmospheric parameters and chemical abundances (Sect. 2.1), (ii) DR3 radial velocities (Sect. 2.2), (iii) EDR3 astrometric data and distances (Sect. 2.3), (iv) a set of stellar velocities and orbits specifically derived for this work (Sect. 2.4), and (v) the definition of working subsamples (Sect. 2.5) allowing us to optimise the scientific analysis, and illustrating the use of quality flags defined in Recio-Blanco et al. (2023).

In Sect. 3 we present the global chemical properties of the Milky Way through sky and Galactic maps (Sect. 3.1) and explore selection function effects (Sect. 3.2). Section 4 presents the radial and vertical chemical gradients of field stellar populations. In Sect. 5 we present our analysis of large-scale chemo-kinematical correlations, while in Sect. 6 we explore the relation between the orbital parameters and stellar chemistry. Subsequently, Sect. 7 is dedicated to chemo-dynamical relations in solar cylinder populations using individual element abundances, and in Sect. 8 we use the open clusters population to study chemo-kinematical correlations and the temporal evolution of disc radial chemical gradients.

Finally, Sect. 9 summarises the results of our Galactic chemo-dynamical analysis using the Gaia RVS GSP-Spec database. In particular, we discuss the observed chemical markers of Milky Way structure (Sect. 9.1), disc kinematic disturbances (Sect. 9.2), and satellite accretion (Sect. 9.3). This is completed with the examination of the detected chemo-dynamical trends of the last billion years (Sect. 9.4) and, finally, with a discussion of the Sun’s chemo-dynamical properties in the context of its Galactic environment (Sect. 9.5). Our overall conclusions are presented in Sect. 10.

2. Data

2.1. Stellar atmospheric parameters and chemical data

This work makes use of the stellar physical parameters and chemical abundances derived from the Gaia RVS spectra by the GSP-Spec module and available through the astrophysical_parameters table of Gaia DR3. It is worth mentioning that the present work does not use the global metallicity [M/H] derived from BPRP spectra by the General Stellar Parametrizer from Photometry (GSP-Phot) and published in the GaiaSource and AstrophysicalParameters tables (mhgspphot field). Although GSP-Phot metallicities are suitable for different scientific purposes, their application to large-scale Galactic chemo-dynamical studies requires a calibration that at the time of writing this paper was not available.

GSP-Spec estimates the main atmospheric parameters (effective temperature Teff, stellar surface gravity log(g)5, global metallicity [M/H]6, and the global abundance of α-elements7 with respect to iron [α/Fe]), together with the individual abundances of 12 different chemical elements from RVS spectra of single stars. The RVS wavelength range is [845 − 872] nm, and its medium resolving power is R = λ/Δλ ∼ 11 500 (Cropper et al. 2018). This spectral parametrisation is based on the MatisseGauguin GSP-Spec workflow and is described in detail in the GSP-Spec processing paper (Recio-Blanco et al. 2023). It is worth recalling that the GSP-Spec [M/H] estimation considers all the non-α metallicity indicators in the observed spectra thanks to a four-dimensional synthetic spectra grid including not only the [M/H] dimension but also the [α/Fe] one. Non-α indicators are dominated by Fe lines in the RVS domain. As a consequence, the estimated [M/H] value follows the [Fe/H] abundance with a tight correlation.

In the following sections, Teff is taken from the teffteffgspspec field; log(g) comes from the logggspspec field; [M/H] is taken from mhgspspec; and [α/Fe] corresponds to alphafegspspec with a calibration8 imposed that requires a zero average value for [α/Fe] in the solar neighbourhood for any gravity (see Recio-Blanco et al. 2023, Table 4).

In a similar way, all the stellar individual chemical abundances come from the GSP-Spec estimates. In particular, this paper makes use of [N/Fe] (nfegspspec), [Mg/Fe] (mgfegspspec), [Si/Fe] (sifegspspec), [S/Fe] (sfegspspec), [Ca/Fe] (cafegspspec), [Ti/Fe] (tifegspspec), [Cr/Fe] (crfegspspec), [Fe/M] (femgspspec), [Ni/Fe] (nifegspspec), and [Ce/Fe] (cefegspspec). As for the [α/Fe] estimates, these individual abundances were calibrated following the prescriptions indicated in Table 4 of Recio-Blanco et al. (2023). It is important to note here that GSP-spec assumes the reference solar abundances of Grevesse et al. (2007).

In addition, we make use of the GSP-Spec quality flags reported in the flagsgspspec string chain (which consists of 41 characters) defined in Recio-Blanco et al. (2023). For example, we make use of the first three characters in this chain (that is, flagsgspspec[0], flagsgspspec[1], and flagsgspspec[2], reporting on the degree of parameter biases from line broadening) and called vbroadT, vbroadG, and vbroadM, respectively (see naming convention in Recio-Blanco et al. 2023).

Finally, the uncertainty on any derived parameter (Paramunc) or abundance ([X/Fe]unc) is defined as half of the difference between its upper and lower confidence levels (e.g. Teffunc = [teffgspspecupper − teffgspspeclower]/2).

2.2. Radial velocities

The complete GSP-Spec sample contains 5 594 205 stars in total (based on the query flagsgspspec is not null). DR3 provides radial velocities (radialvelocity, VRad) for 33 834 834 stars (Katz et al. 2023) through the gaia_source table. The GSP-Spec sample is a subset of the VRad sample because the GSP-Spec sample was selected based on the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) of the mean RVS spectra. An unpublished GSP-Spec S/N > 20 was used (Recio-Blanco et al. 2023). This was found to be very similar to rvexpectedsigtonoise9 in the gaia_source table. VRad is used to Doppler shift RVS CCD spectra to rest before combining them into a mean RVS spectrum (Seabroke et al., in prep.). The sensitivity of GSP-Spec parametrisation to spectra that are not perfectly corrected for their radial velocity shift is flagged in the GSP-Spec flagsgspspec string. In particular, characters 3 to 5 (flagsgspspec[3], flagsgspspec[4] and flagsgspspec[5]), called vradT, vradG, and vradM respectively, report on the degree of parameter biases from VRad uncertainties (see Recio-Blanco et al. 2023, for more details on these flags).

2.3. Astrometric data and distances

High-precision astrometric parameters (α, δ, μα*, μδ, ϖ) from Gaia EDR3 (Gaia Collaboration 2021a) complement the above-described radial velocities, allowing three-dimensional study of stellar velocity. Thanks to the bright magnitude limit of the spectroscopic sample, the median parallax uncertainty is better than 20 μas for most of our targets and the median uncertainty increases up to a maximum of ∼40 μas for the faintest stars with magnitude G ≃ 14.

Based on these Gaia EDR3 astrometric data, Bailer-Jones et al. (2021) geometric distances, rGeo, are adopted in this study. To test the implications on our analysis of the Galaxy prior (a 3D model of the stellar distribution and extinction) adopted by Bailer-Jones et al. (2021), we defined an astrometric control sample (ACS, Appendix A). This sample is composed of stellar distances, rϖ, exclusively based on the observed Gaia trigonometric parallaxes after removing the individual parallax zero points, Δϖ, following Lindegren et al. (2021). In addition, the ACS selection fulfills the following criteria: (i) a parallax uncertainty of less than 20% derived from (ii) five-parameter astrometric solutions with renormalised unit weight error (RUWE) < 1.4, (iii) sources not flagged as duplicated by the Gaia cross-matching algorithm (Torra et al. 2021), and (iv) with full photometry (G, GBP, GRP) and radial velocity available. To compare the two distance estimates, we consider the fractional residual (rGeo − rϖ)/rϖ for objects in common. The median value of the residuals is −0.04% and its median absolute deviation is 0.2%, showing very good overall agreement between both estimates. As shown in Appendix A, the main discrepancy occurs in the Galactic plane, where Bayesian distances are greater than the pure trigonometric parallax-based distances by ≲4%. These very small discrepancies have a negligible impact on the results of this work and, as a consequence, rGeo distances are adopted in the following.

2.4. Galactocentric positions, velocities, and orbits

For the computation of the stellar positions (Galactocentric Cartesian X, Y, and Z positions, and cylindrical radius R) and the Galactocentric cylindrical velocities (VR, Vϕ, and VZ in a right-handed frame with positive Vϕ for most of the disc stars), we adopted the Sun’s Galactocentric position (R, Z)⊙ = (8.249, 0.0208) kpc (Gravity Collaboration 2021; Bennett & Bovy 2019) and Galactocentric cylindrical velocities (VR, Vϕ, VZ)⊙ = ( − 9.5, 250.7, 8.56) km s−1 (Reid & Brunthaler 2020; Gravity Collaboration 2021), as well as Gaia’s α, δ, line-of-sight velocity, and Bailer-Jones et al. (2021) geometric distances for each target. The orbital parameters (actions JR, Jϕ, JZ, apocenter and pericenter distance Ra, Rp, maximum distance from the plane reached during the star’s orbit Zmax) are computed using the Stäckel fudge method Binney (2012) implemented in the Galpy code (Bovy 2015), combined with a rescaled version of the McMillan (2017) axisymmetric Galactic potential. In this model, the Galactocentric distance of the Sun is R⊙ = 8.249 kpc while the circular velocity of the Local Standard of Rest is set to 238.5 km s−1 (Gravity Collaboration 2021; Schönrich et al. 2010). The lower and upper confidence limits for each of these parameters are obtained by drawing Monte Carlo realisations of μα*, μδ, VRad, and distance, and propagating them through the positions, velocities, and orbits. We assumed Gaussian symmetric distributions for the proper motions and line-of-sight velocities, and a broken Gaussian distribution for distance (based on the lower and upper confidence limits of Bailer-Jones et al. 2021). The data on Galactocentric positions, velocities and orbits used in this paper can be retrieved via the Gaia archive table gaiadr3.chemical_cartography.

2.5. Working samples

To optimise the analysis of this work, different data selections and quality cuts are required. To this purpose, we defined several data samples with the following characteristics. The precise conditions used for these sample selections are presented in Appendix B, including the corresponding catalogue queries.

General sample (5 527 090 stars; Sects. 3 and 6): From the complete GSP-Spec sample (containing 5 594 205 stars in total), we excluded about 56 000 stars located near the cool end of the GSP-Spec parameter space and suffering from biases in different parameters (Recio-Blanco et al. 2023). The remaining objects without rGeo distances were removed. For this sample, the median uncertainty in [M/H] is 0.075 dex and the median uncertainty in [α/Fe] is 0.05 dex.

Medium quality sample (4 140 759 stars; Sect. 3, Sect. 5, Sect. 6): This results from additional quality criteria rejecting stars with grid border effects and large parameter uncertainties. For this sample, the median uncertainty in [M/H] is 0.06 dex and the median uncertainty in [α/Fe] is 0.04 dex.

Gradient analysis sample (2 762 809 stars, Sect. 4): This optimises the quality of the [M/H] and [α/Fe] parameters and the astrometric quality to ensure reliable distance estimates, with the goal of estimating radial and vertical gradients. For this sample, the median uncertainty in [M/H] is 0.05 dex and the median uncertainty in [α/Fe] is 0.035 dex.

High-quality sample (2 218 573 stars, Sect. 5): This selects the most precise stellar parameters and chemical abundances. We note, in particular, that the choice of the fluxNoise = 0 filter flag imposes a selection of stars with very low parameter uncertainties. For this sample, the median uncertainty in [M/H] is 0.03 dex and the median uncertainty in [α/Fe] is 0.015 dex.

Individual abundances samples (Sect. 3 and 7): these have been defined to optimise the individual abundance distributions of different chemical elements. The number of selected stars depends on the chemical element. Specifically, as expected, the precision of abundance measurements is a function of different conditions, such as the number of analysed lines, their equivalent widths, and possible blends, which vary with effective temperature, surface gravity, mean metallicity, and other individual abundances, and is different from one element to another.

3. Global chemical properties of the Milky Way

The ∼5.5 million star database of spectroscopic stellar parameters and chemical abundances (see Sect. 2.1), as part of the Gaia all-sky data collection, provides significant radial and vertical coverage of our Galaxy, but also probes a considerable range in azimuth. In this section, we first analyse the global spatial distribution of the stars in the Milky Way and their chemical properties, and then we illustrate the selection function in radial and vertical bins. Here, we show the chemical properties and spatial coverage of three representative stellar populations selected from the Kiel diagram of the near-plane objects: massive young stars, bright red giant branch (RGB) objects and hot turn-off (TO) stars.

3.1. Spatial and chemical trends

Sky maps in Galactic coordinates. The distribution of all the stars in the General sample is presented in Galactic coordinate maps colour coded according to distance (Fig. 1), metallicity (Fig. 2), and [α/Fe] abundance (Fig. 3).

|

Fig. 1. Milky Way stars in the GSP-Spec database (General sample). This HEALPix map (Górski et al. 2005) in Galactic coordinates has a resolution of 0.46°. The colour code corresponds to the median of the stellar distance from the Sun. This colour code enhances thin and thick disc populations in the Galactic plane, far from the solar neighbourhood. The Galactic bulge stars are also visible in the central region. Finally, the higher distance of the Magellanic Clouds and of several globular clusters reveal their presence in the regions far from the Galactic plane otherwise dominated by foreground stars of the solar neighbourhood. |

|

Fig. 2. Same as Fig. 1 but colour coded with the median of the stellar metallicity [M/H] in each pixel. In the Galactic plane, the higher metallicity values of the thin disc are visible. In the central Galactic regions, a more metal-poor mix of bulge and thick disc populations is present. Far from the disc plane, high-metallicity thin disc stars at low distances from the Sun and more distant metal-poor halo stars are present. |

|

Fig. 3. Same as Fig. 2 but colour-coded with the median of [α/Fe] in each pixel. The large structures close to the ecliptic poles are artifacts caused by the Gaia scanning law (see text). Thin disc stars are visible in the plane thanks to their low [α/Fe] values. |

We first note that the ecliptic pole scanning law (EPSL; Boubert & Everall 2020) pattern is visible in Fig. 3 with slightly higher [α/Fe] values. Between 25 July and 21 August 2014 (the first weeks of Gaia’s nominal mission), Gaia operated in EPSL mode (Gaia Collaboration 2016). During this period, stars close to the ecliptic poles and along great circles connecting them were observed a greater number of times than during Gaia’s nominal scanning law. This leads to spectra with higher S\N towards the EPSL footprint. As Gaia continues to observe in nominal scanning law, the S/N will homogenise over the sky for future data releases. The higher S/N of the spectra along the EPSL pattern allows the parameterisation of fainter (and hence more distant) stars in these regions, leading to a slightly lower mean metallicity and especially larger mean [α/Fe] values per pixel.

The metal-rich and relatively α-low thin disc is easily identified in Figs. 1–3. In the direction of the Galactic bulge, outside the Galactic plane, one sees a dominant metal-poor population. Indeed, due to the fact that the bulge is more radially concentrated, many thick disc stars are present in these regions, decreasing the median metallicity. The regions located far from the plane are filled with a mixture of nearby metal-rich α-low disc stars and more distant metal-poor α-rich halo stars (see also Sect. 4).

To complement this first global view, we cut Fig. 2 into different distance intervals from the Sun (see Fig. 4). Similar figures for the [α/Fe] distribution are provided in the Appendix (Fig. C.1). The scanning law features described above are visible in the closest distance bin (D < 0.5 kpc, upper left panel). Figures 4 and C.1 show that, whereas the sky is filled by metal-rich and α-low thin disc stars within 500 pc of the Sun, the Galactic discs start to progressively emerge with increasing distance. The more metal-poor and α-rich halo dominates beyond ∼4 kpc. In the more distant panel, beyond 6 kpc, the thick disc is well seen on both sides of the Galactic centre and the thin disc has almost disappeared because of interstellar extinction. An asymmetry can also be seen in the metallicity map close to the Galactic centre (with the central region being more metal-rich at positive longitudes than at negative ones), which may result from the presence of the central bar and an inhomogeneous distance distribution around the Galactic centre in this more distant bin due to extinction. Finally, the Small and Large Magellanic Clouds (SMC and LMC, respectively) are also clearly visible in this panel, both being rather α poor. We note that the LMC appears rather metal rich. Our LMC sample is indeed dominated by bright massive and young stars (referred to as blue loop stars by Gaia Collaboration 2021b), which likely sample the metal-rich LMC populations.

|

Fig. 4. Same as Fig. 2 but for different distance intervals shown from the closest (top panel of left column) to the most distant (bottom panel of right column). The distance ranges adopted in each panel are indicated in their lower right corner together with the number of stars in their bottom left corner. The colour code corresponds to the median of the metallicity and is continuous between the first four subpanels showing rather metal-rich stars, and the two last panels dominated by metal-poor populations. |

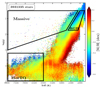

Galactic maps in Cartesian coordinates. Figure 5 (top panels) shows three maps in (X–Y) Cartesian coordinates of all the General sample stars superimposed on the Milky Way sketch of Hurt & Benjamin (Churchwell et al. 2009). From left to right, the maps are colour coded according to stellar counts, mean metallicity, and enrichment in α-elements with respect to iron. We note that, in the panels colour coded according to [M/H] and [α/Fe], the apparent bulge asymmetry described in Figs. 4 and C.1 is again seen between the Sun and the Bar.

|

Fig. 5. Galactic maps for the General sample stars colour coded according to stellar count, the median of [M/H], and the median of [α/Fe] (from left to right, respectively). Top row: the maps in Cartesian coordinates (X,Y), with the background image being the Milky Way sketch from Churchwell et al. (2009). Bottom row: R and Z are the distances from the Galactic centre and plane, respectively. |

The bottom row of Fig. 5 shows the distribution of the same stars in the (R, Z) plane, where R is the Galactic centre distance and Z the distance from the Galactic plane. It can be seen that the spatial coverage of this sample with measured [M/H] and [α/Fe] is very large, spanning several kiloparsec. Close to the Galactic plane and towards the inner regions, a thin stripe of metal-rich low-α stars is clearly seen. Its vertical extension is about 300 pc below and above the plane, which is the typical scale height of the thin disc. This stripe is therefore the thin disc seen edge-on. It is not detected for R ≲ 3.5 kpc because of interstellar extinction and the resultant lack of sufficiently bright stars for analysis by GSP-Spec at smaller Galactic radii. Towards the external regions near the plane, this thin disc is also seen up to ∼14 kpc from the Galactic centre. Its flare in the outer regions is traced by the progressive increase of high-metallicity low-[α/Fe] stars farther away from the plane, as we move towards higher R values (see Sect. 5 for a chemo-kinematical perspective of the disc flare). Moreover, the stars located close to the Galactic plane but in the external parts of the disc appear more metal poor and slightly more α rich: a clear gradient in [M/H] and [α/Fe] versus R is thus revealed (see also Sect. 4). As a consequence, at large heights from the Galactic plane, internal regions are dominated by low-metallicity thick disc and halo stars, while for R > 12 kpc, flared disc stars of higher metallicity and lower [α/Fe] values dominate.

3.2. Exploration of the selection function

The large spatial coverage of the Gaia chemical database requires a global presentation of the underlying parameter distribution across the Galaxy. In addition, the large variety of stellar types included in the catalogue demands that we understand the underlying spatial distribution across the Kiel diagram. Without entering into a detailed characterisation of the selection function, in this section we explore its impact so as to help DR3 users and to support the chemo-dynamical analysis of this paper.

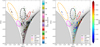

3.2.1. Stellar parameter distribution across the Galaxy

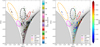

To dissect the covered spatial volume, we divided the (R, Z) plane into bins of 2 × 2 kpc2. The resulting [R, Z] grid of Kiel diagrams colour coded according to [M/H] is shown in Fig. 6, and that of [α/Fe] versus [M/H] distributions is presented in Fig. 7. In both figures, the global (R, Z) density contour plot is shown in the background. For the purpose of clarity, only the stars in the Medium Quality sample (4 140 759 objects) are included. As anticipated from the previous section, about 90% of this sample is found between 6 and 10 kpc in R and |Z|< 2 kpc.

|

Fig. 6. Kiel diagrams across the Milky Way for the Medium Quality sample, colour coded according to the median of the mean metallicity. The number of stars in each subpanel is indicated in its upper left corner. The global (R, Z) distribution of Fig. 5 (bottom row) is shown in the background with grey levels. Moving away from the Sun, the sample becomes dominated by intrinsically bright giants. |

The majority of the stars are metal-rich and alpha-poor dwarfs on the main sequence and belonging to the thin disc. Close to the Sun, all evolutionary stellar stages from main sequence stars up to the tip of the asymptotic giant branch (AGB) are encountered with a large mixture of [M/H] and [α/Fe] combinations. Moving away from the solar location in both directions, the selection function progressively favours intrinsically brighter stars with lower log(g) values. The radial and vertical metallicity gradients can also be qualitatively appreciated (see Sect. 4 for quantification of the gradients). For |Z|> 4 kpc, only metal-poor RGB and AGB stars are observed and most of them have metallicities of between ∼ − 2.5 and ∼ − 0.5 dex with high α-enrichment. Nevertheless, a few more metal-rich stars from the flared disc are visible in the outer regions. We also note a high symmetry with respect to the Galactic plane for the Kiel and [α/Fe] versus [M/H] diagrams. As illustrated in Fig. 7, the global standard decreasing trend of [α/Fe] with metallicity can be seen across the Galaxy.

3.2.2. Kiel diagram selections near the Galactic plane

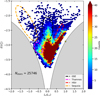

To further illustrate the selection function close to the Galactic plane, where stellar type variations are more important, we first show in Fig. 8 the Kiel diagram of the Medium Quality stars with |Z|< 1 kpc. We then define three subsamples by selecting: (i) the hottest dwarfs of the main sequence around the turn-off, (ii) the bright part of the RGB above the clump, and (iii) the massive bright stars hotter than the RGB, including blue loop stars and variables such as Cepheids. This last selection, which is biased towards young stars, is indeed dominated by stars located very close to the Galactic plane and an additional filter keeping stars at |Z|< 400 pc is applied to avoid contaminants (mainly from the RGB population that is nearby in the Kiel diagram). Hereafter, these subsamples are respectively labelled hot turn-off (HotTO), RGB, and Massive as indicated in Fig. 8.

|

Fig. 8. Kiel diagram of all the Medium Quality stars located within 1 kpc of the Galactic plane. The location of the HotTO, RGB, and Massive subsamples is illustrated. Their spatial distribution and chemical properties are detailed in Figs. 9–11, respectively. |

The (X,Y) spatial distribution and chemical properties of the three populations are shown in the left and central panels of Figs. 9–11, respectively. The metallicity colour scale is the same in the three figures for comparison purposes. In addition, the right top panels in the three figures show the evolution of the calcium abundance ratio with respect to iron, [Ca/Fe], as a function of metallicity for the three populations selected in the Kiel diagram of Fig. 8. The abundance of this chemical element is the easiest to derive from RVS spectra thanks to the presence of the strong absorption Ca II IR triplet lines. Finally, the abundance trends of additional elements are shown in the right bottom panels as a function of stellar type and therefore the presence or absence of the lines of an element in the related spectra. Sulfur lines are only detected for hot dwarfs (because of its rather high excitation energy) and its abundance is illustrated in Fig. 9. The only nickel line selected in the RVS range provides reliable estimates for bright cool giants and its corresponding abundance is shown in Fig. 10. Finally, nitrogen abundances are nicely illustrated using the hot massive population in Fig. 11.

|

Fig. 9. HotTO stars of the Medium Quality sample located within 1 kpc of the Galactic plane. Their XY spatial distribution is shown within ±4 kpc of the Sun, colour coded according to stellar count and the median of the mean metallicity (left and central panels, respectively). The solar position is indicated by a filled star coloured according to solar metallicity ([M/H] = 0.0 dex). Right panel: evolution of calcium (top) and sulfur (bottom) abundances with respect to iron abundances versus the mean metallicity. |

|

Fig. 10. Same as Fig. 9 but for RGB stars within 1 kpc of the Galactic plane and over a more extended XY domain (±6 kpc from the Sun). Nickel abundances are shown in the bottom-right panel. |

|

Fig. 11. Same as Fig. 9 but for Massive stars located within 400 pc of the Galactic plane, thus focusing attention on the thin disc. The spiral arm structure is visible in the left and central panels. Calcium and nitrogen abundance distributions are shown in the right top and bottom panels, respectively. For comparison, the distribution of the RGB stars in terms of calcium abundance is shown in grey in the top panel. |

To optimise the individual chemical abundance plots, the Individual abundance sample defined in Sect. 2.5 is used. We note that, even after applying rather strict selection criteria (cf. Sect. 2.5), the number of reported abundances is huge (from ∼104 to a couple of ∼106, depending on the chemical species) and generally much larger than any other published abundance catalogue. As shown below, the behaviour of these chemical species is in perfect agreement with previously published catalogues of stellar abundances and with Galactic chemical evolution models (see e.g. Prantzos et al. 2018; Kobayashi et al. 2020; Matteucci 2021, and references therein for observational datasets), confirming their high quality. Finally, we note here that the individual abundance calibrations proposed by Recio-Blanco et al. (2023) have been applied.

Spatial distributions in the disc plane. First, the left panels of Figs. 9–11 reveal that almost 680 000 HotTO stars are found within about 1 kpc of the Sun, because they are not bright enough to sample more distant regions. In contrast, the RGB sample contains somewhat fewer stars (about 580 000) but allows us to explore much more extended regions up to 5–6 kpc from the Sun. Similarly, Massive stars are distributed up to about 3 kpc from the Sun. Their spatial distribution is not homogeneous and nicely reveals the closest spiral arms, that is, the Sagittarius/Carina, Local, and Persus arms, in agreement with the spatial maps derived by Poggio et al. (2021b) from Gaia EDR3 astrometry and photometry. These massive stars also show the enhanced equivalent width of the diffuse interstellar band at 862 nm, confirming their nature as tracers of the spiral arms (Gaia Collaboration 2023b).

Metallicity distributions in the Galactic plane. The metallicity distributions in the (X,Y) plane of the three samples are shown in the central panels of Figs. 9–11. Most strikingly, we see that a large fraction of the HotTO stars are metal rich (up to [M/H] ∼ +0.5 dex). Indeed, the selection of the HotTO sample favours the younger and therefore more chemically enriched TO stars because of the temperature cut at Teff > 6000 K. Finally, the slightly more metal-poor yellowish feature centred on the solar position comes from an inhomogeneous Z distribution of these stars. In fact, near the Sun, the sample reaches slightly greater distances from the plane, with median values of around 0.2 kpc, while outside the solar vicinity, and probably driven by the younger objects in the sample, most of the HotTO stars are slightly hotter (in order to be brighter) and therefore closer to the plane at |Z|≲0.1 kpc. Therefore, the vertical metallicity gradient (see also Sect. 4) seems to explain the central metallicity feature. Nevertheless, the solar metallicity (represented by the colour of the central starred marker) is in agreement with the global [M/H] distribution of HotTO stars, as expected.

Regarding the RGB sample (cf. Fig 10), stars are on average more metal-poor than the HotTO ones, with values around [M/H] < –0.4 dex in most parts of the (X,Y) plane. However, there is a metallicity gradient that is visible for X ≳ 5 kpc, with [M/H] values decreasing with distance from the Galactic centre, as expected (see also Sect. 4). In this framework, the Sun’s metallicity is clearly higher that the average observed one in the solar surroundings. This is probably due to the underlying age distribution of RGB stars. In fact, the selected locus of the Kiel diagram is populated by a large range of stellar masses, corresponding to a wider age distribution of these objects. In addition, the Z distribution of this RGB sample includes stars farther away from the plane that reduce the median metallicity.

Interestingly, we clearly see that the distribution is not azimuthally symmetric. Stars with X in the range between 5 and 7 kpc and Y within [−2.0,+4.0] kpc seem to define a metal-rich sustructure, which probably coincides with the Sagittarius arm position. Moreover, stars with X in the range between 7 and 10 kpc show an azimuthal metallicity trend, with objects in azimuthal angles closer to the major axis of the Galactic bar (lower Y values in the figure) having higher metallicities. This could also be the consequence of the presence of the Local Arm and generally of the pitch angle of the spiral arms. For the innermost regions of the Galaxy, it could also partially result from a spatially inhomogeneous extinction distribution. In any case, these azimuthal dependencies reveal an inhomogeneous metallicity distribution, even for this upper RGB population for R ≳ 5–6 kpc. In this sense, it is worth noting that the innermost regions (X < 5 kpc) in this figure appear metal poor and therefore do not follow the radial metallicity gradient. However, as is visible in the bottom panels of Fig. 5, the inner Galaxy sample is dominated by metal-poor thick-disc stars, particularly at |Z|> 0.5 kpc.

Finally, the central panel of Fig. 11 shows that the arms internal to the position of the Sun and mapped by the Massive stars are much more metal-rich than the external ones, following again the expected radial gradient. It can also be noted that, as already discussed for the RGB sample, Massive stars show azimuthal dependencies in their metallicity distribution. In addition, it can be seen that the Sun lies between two distinct spiral arms and that its mean metallicity is higher than that of the surrounding younger Massive stars. This seems to indicate that the younger populations are chemically impoverished, which is in contradiction with a continuous chemical evolution where metallicity increases with time. It is also in contrast with the older but more metal-rich turn-off stars discussed above. This point is discussed in more detail below, when looking at other chemical diagnostics. It is worth noting that although the parametrisation of young stars from high-resolution spectra (R ≳ 100 000) can be difficult because of a combination of intrinsic factors (activity, fast rotation, magnetic fields; see for instance Zhang et al. 2021; Spina et al. 2020), this is mainly affecting particularly young stars (age ≲200 Myr) and does not alter the RVS parametrisation, which is performed at medium resolution (R ∼ 11 500). Visual inspection of the GSP-Spec parameter and individual abundance solution and synthetic spectral fitting for one typical star of the Massive population can be found in Recio-Blanco et al. (2023). No particular parametrisation problems are reported for these stars; they have generally very high S/N values. Additional support to the derived metallicities for this population comes from the validation by Clementini et al. (2023) of RR Lyrae metallicities. The authors show that spectroscopic GSP-Spec metallicities are in good agreement with those derived from the period–luminosity relation. RR Lyrae stars are indeed a subsample of our Massive population.

[Ca/Fe] distributions. We now look at the [Ca/Fe] abundances presented in the upper right panels of Figs. 9–11 (individual abundances samples). Concerning HotTO stars, Fig. 9 presents the [Ca/Fe] trend with metallicity. As expected for this faint nearby population, the distribution is dominated by a low-α thin-disc sequence, with [α/Fe] decreasing as metallicity increases and reaching [M/H] values as high as +0.5 dex. The relatively large metallicity range of this sample is therefore probably due to stars of different origins visiting the solar neighbourhood as already observed for ground-based surveys of dwarf stars. We emphasise that the decrease in [Ca/Fe] with [M/H] is continuous even for super-solar metallicity stars, in perfect agreement with Galactic evolution chemical models. This is seen for the first time with Gaia DR3 data thanks to an optimised spectral normalisation of metal-rich stars (Santos-Peral et al. 2020).

[Ca/Fe] abundances are presented for the RGB population in the right upper panel of Fig. 10. Two sequences are easily identifiable, with the thick disc population being more numerous for the RGB selection than for the HotTO one. As already mentioned, the metallicity distribution of the RGB is shifted to more metal-poor values than that of HotTO stars. We also note that the continuous decline in [Ca/Fe] abundance with metallicity seen for the HotTO sample is also visible here; however it is less clearly observable due to the presence of [Ca/Fe]-poor RGBs at metallicities larger than ∼ − 0.3 dex coming from the Massive sample, which is contiguous in our Kiel diagram selection. The [Ca/Fe] decline with [M/H] in the thin-disc sequence can also be seen by examining the upper envelope of the [Ca/Fe] distribution, which reaches [Ca/Fe] ∼ +0.0 dex at [M/H] ∼ +0.25 dex.

Finally, Fig. 11 illustrates the [Ca/Fe] abundance for about 7400 Massive stars. The corresponding distribution for the stars in the RGB population is shown in grey for reference. Surprisingly, most stars in the Massive sample are Ca poor, presenting [Ca/Fe] values down to ∼–0.3 dex with [M/H] varying between −0.5 and +0.0 dex. This confirms the apparent chemical impoverishment of this young population discussed above. We investigated whether these peculiarly low abundances could be due to a zero-point offset for the Massive stars or an artifact of the abundance calibration. The different tests that we performed, which are presented in Appendix D, allow us to conclude that, for all the combinations of calibration flavours including no calibration, the Massive sample is impoverished in [α/Fe] with respect to the thin disc sequence. In addition, the maximum metallicity reached by the Massive sample is also lower than that of the RGB and HotTO samples, independently of the chosen calibration flavour. It is also interesting to consider the fact that this type of young cool massive star in the spiral arms is rare (because of its shorter lifetime). Therefore, only a high number statistics survey, as in the Gaia/RVS one, can observe enough stars of this type to be statistically relevant in the different abundance distributions.

As noted above, the observed chemical impoverishment of the Massive population is in contradiction with a continuous chemical evolution of the thin disc. Moreover, because of the decreasing stellar density with Galactic radius, the mechanism whereby inward migration favours lower metallicities (as required to explain the chemical pattern of the Massive population) should not dominate. Chemical evolution models and/or simulations, which are beyond the scope of this paper, will be necessary to develop the interpretation of the chemical pattern seen in Massive stars.

Other individual abundance distributions. We now discuss the additional individual chemical abundance distributions presented in the right lower panels of Figs. 9–11. For HotTO stars, Fig. 9 shows the variation of sulfur abundance with metallicity for more than 36 000 stars. The behaviour of sulfur with metallicity, although exhibiting a larger spread than the [Ca/Fe], is in agreement with the observed global [α/Fe] trend, again showing a continuous decrease with metallicity. Indeed, the ratio [S/Ca] (and the [S/α] one) is almost equal to zero (with a median value of 0.02 dex) over the whole metallicity range, with a rather small median absolute deviation (MAD = 0.06 dex). This confirms the α-like nature of sulfur in agreement with previous studies (see Perdigon et al. 2021, for a recent review and consistent results derived from high-resolution spectra).

Regarding the RGB sample, about 28 000 nickel abundances are reported for the RGB sample in Fig. 10 (we adopt here [Ni/Fe]unc < 0.15 dex to increase the size of the sample). [Ni/Fe] stays close to zero for all metallicities, in agreement with the iron-peak nature for this chemical element. Regarding the Massive population in Fig. 11, the approximately 4000 calcium-poor stars located in the spiral arms have nitrogen abundances close to zero (with a very small dispersion) for metallicities varying between −0.5 and 0.0 dex.

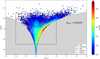

Finally, we show in Fig. 12 the behaviour of cerium with metallicity for the coolest part of the Massive stars plus the whole RGB sample. This allows us to select a disc stellar sample with a wide age distribution, from the younger populations in the spiral arms to the older stars in the RGB sample. The two populations show a large, and very similar spatial coverage. We remind the reader that cerium is a neutron-capture element that is predominantly produced by slow-neutron captures and belongs to the second peak of the s-elements. We find about 7000 stars with Ce estimates in these two subsamples, relaxing the Ce upper limit flag to allow values equal to 2. The upper panel of Fig. 12, which is colour coded according to stellar density, shows that the [Ce/Fe] abundance decreases with mean metallicity in agreement with previous studies (see also Sect. 7) and Galactic chemical evolution models. Moreover, there is a group of stars with very negative [Ce/Fe] for [M/H] between about −0.5 and −0.25 dex. As shown in the lower panel of Fig. 12, in which the [Ce/Fe] versus [M/H] distribution is colour coded according to [Ca/Fe] abundance, these low-[Ce/Fe] stars correspond to the Massive Ca-poor population located in the Galactic arms. Therefore, Ce abundances confirm the chemical impoverishment seen in metallicity and other chemical elements for this Massive star sample.

|

Fig. 12. Cerium abundances for the coolest Massive and RGB stars of the Medium Quality sample located close to the Galactic plane and colour coded according to stellar density and the median of [Ca/Fe] (top and bottom panel, respectively). |

4. Radial and vertical gradients

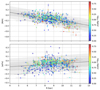

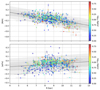

In this section, we investigate the overall radial and vertical gradients for metallicity and calibrated [α/Fe] (cf. Sect. 2.1 and Recio-Blanco et al. 2023), linking these results to the ones previously found in the literature. For this purpose, we use the Gradient analysis sample defined in Sect. 2.5.

Figure 13 shows the median metallicity (upper panel) and [α/Fe] (lower panel) radial values for five different distances below (dashed lines) and above (full lines) the Galactic midplane (i.e. in a total of ten different bins in Z). This is indeed achievable with good statistics, given the large number of stars for which we have parameters; however, we note that we do not separate our sample into chemically thin or thick disc (i.e. based on their [α/Fe]-[M/H] sequence). It is interesting to note the limited range in [α/Fe] enhancement in this figure, peaking at about ∼0.2 dex. This is explained by the fact that GSP-Spec [α/Fe] abundances are governed by calcium indicators dominating the RVS α-element information in many pixels. The calcium abundance range in the thin- and thick-disc distributions is more limited than in other elements such as magnesium, as already observed in the data from ground-based surveys such as the Gaia-ESO Survey (Mikolaitis et al. 2014) and APOGEE (Abdurro’uf et al. 2022). Figure 14 is similar to Fig. 13, showing this time the vertical gradients in metallicity (upper panel) and [α/Fe] (lower panel) for four different R bins.

|

Fig. 13. Radial gradients for metallicity (top) and [α/Fe] (bottom) for different distances from the Galactic midplane (in kpc; see the legend). The trends are computed as running medians in bins of 0.5 kpc, with a 40 percent overlap, provided that at least 50 stars are available to compute the median. The shaded areas represent the Poisson uncertainty on the trends. The colours, which are associated to Z distances from the plane, are similar if the |Z| range is the same. |

It is remarkable to find that both metallicity and [α/Fe] trends show similar behaviours above and below the plane, when the same |Z| range is considered. More specifically, we find that both metallicity and [α/Fe] gradients have a break in their slope at galactocentric radii R ∼ 7 kpc, which is particularly visible for |Z|≲1 kpc. This behaviour is in agreement with results from Haywood et al. (2019) using α-low stars from the APOGEE-DR14 catalogue, Kordopatis et al. (2020) from a compilation of spectroscopic catalogues of field stars (LAMOST, RAVE, GALAH-DR2, and APOGEE-DR14), and Katz et al. (2021) using both α-high and α-low stars from the APOGEE-DR16 catalogue. More specifically, we find that the median metallicity either flattens or even decreases towards the inner Galaxy, while, at the same R-position, the median [α/Fe] increases (see lower plot of Fig. 14). We note that this change of regime stays roughly similar when one selects stars based on Zmax and guiding radius (see Fig. 15).

|

Fig. 14. Vertical gradients for metallicity (top) and [α/Fe] (bottom), for different Galactocentric radial ranges. The trends are computed as running medians in bins of 0.5 kpc, with a 40 percent overlap, provided that at least 50 stars are available to compute the median. Shaded areas represent the Poisson uncertainties on the plotted values. |

|

Fig. 15. Same as Fig. 13, selecting this time the stars as a function of Zmax and plotting the guiding radius (defined as (Rapo + Rperi)/2) instead of the observed radius. |

Table 1 reports the linear [M/H] and [α/Fe] trends as a function of R, in the form of ax + b (and their associated uncertainties ea and eb, respectively), only considering the galactocentric radii larger than 7 kpc. We find that the metallicity slope for the closest bin to the plane is ≈ − 0.056 ± 0.007 dex kpc−1. This is slightly different from but still consistent with the metallicity gradients found using Cepheids (e.g. −0.060 ± 0.002 dex kpc−1Genovali et al. 2014, and −0.045 ± 0.07 dex kpc−1, Lemasle et al. 2018), open clusters (e.g. −0.076 ± 0.09 dex kpc−1Spina et al. 2021, and −0.068 ± 0.001 dex kpc−1, Donor et al. 2020), or thin disc (i.e. low α-sequence) field stars (e.g. ∼ − 0.053 to ∼ − 0.068 dex kpc−1Bergemann et al. 2014; Recio-Blanco et al. 2014; Hayden et al. 2015; Anders et al. 2017). The trends become flatter as one moves to larger |Z|, eventually becoming null or slightly positive for bins farther than 1.5 kpc from the plane (−0.005 ± 0.003 at 1.5 < Z < 2 kpc and +0.002 ± 0.004 at 1.5 < Z < 2 kpc). This flattening is again qualitatively consistent with previous results using field stars and interpreted as a smooth transition from a thin disc to more radially concentrated thick disc (see e.g. Boeche et al. 2014; Kordopatis et al. 2020; Nandakumar et al. 2022). We note that the metallicity gradient when considering the Massive stars sample (see the selection in Fig. 8; the gradient close to the plane is flatter than the one found using the RGB sample (−0.036 ± 0.002 dex kpc−1). This difference might be due to the difference in age between these two samples, and is consistent with the gradient found using the youngest sample of open clusters (see Sect. 8).

Radial metallicity and [α/Fe] gradients for R > 7 kpc and all of the stellar types, at different distances from the plane.

As far as the ∂[α/Fe]/∂R gradients are concerned (see Table 1), for R ≳ 7 kpc, we find a value of +0.007 ± 0.001 dex kpc−1 close to the plane, in agreement with the values published by Carrera & Pancino (2011), Yong et al. (2012), Mikolaitis et al. (2014), Genovali et al. (2015), Reddy et al. (2016), Casamiquela et al. (2019), Donor et al. (2020). The trend becomes steeper as one moves farther away from the Galactic plane, reaching eventually −0.016 ± 0.002 dex kpc−1 for 2 < |Z|< 2.5 kpc. Despite not reaching typical thick disc [α/Fe] enhancements at |Z| where the thick disc dominates10 (> 1.5 kpc; see e.g. Hayden et al. 2015; Kordopatis et al. 2015), the qualitative trends that we find show indeed that one moves from a thin-disc-dominated population to a thick-disc-dominated population as |Z| increases. This is also seen from the bottom plot of Fig. 14, for the curves with R < 11 kpc.

The points above, especially the breaks in ∂[M/H]/∂R and ∂[α/Fe]/∂R, are more clearly illustrated by Fig. 14, which shows the vertical gradients as a function of galactocentric radius. Only four R bins are investigated, each of 2 kpc in width, for which a sufficient number of stars are available at all Z (see Fig. 5). As anticipated from the shift in the slopes of Fig. 13, we find non-zero vertical gradients at all R. Considering stars at |Z|< 1 kpc, we find that the inner disc shows steeper vertical metallicity and [α/Fe] gradients. Eventually, at the outermost radii (R = [11 − 13] kpc), we see only a mild vertical metallicity gradient and a null [α/Fe] gradient. This is in agreement with Bensby et al. (2011), Hayden et al. (2015), Kordopatis et al. (2015), Mackereth et al. (2019), Katz et al. (2021), for example, who found that the thick disc is more radially concentrated than the thin disc.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that we also find some wiggles in the radial metallicity trends for |Z|< 0.5 kpc and R ∼ 8.5 kpc – both above and below the plane – that are not related to statistical noise (these bins contain a lot of stars, as they are relatively close to the Sun). While we cannot exclude the possibility that these wiggles could partly be due to dynamical effects (e.g. resonances Antoja et al. 2018; Kawata et al. 2018), it is clear that our geometrical selection biases play an important role in producing them. Indeed, hot TO stars, that is, relatively young and super-solar metallicity stars, can only be seen relatively close to the solar neighbourhood (see Fig. 9). This introduces an age (and metallicity) spatial bias in the sense that the local median metallicity is higher than farther away, simply because TO stars cannot be seen at large distances. Similarly, red clump stars are also lost in the most distant regions, creating a secondary but non-negligible spatial bias. Selecting only giant stars above the red clump (log(g) ≤2), which can be seen in a much more unbiased way at all radii, leads to trends without metallicity wiggles (see Fig. 16) with gradients that are similar (but slightly flatter by ∼0.01 dex kpc−1) than the ones quoted above (see Table 2). This indicates that the selection function plays an important role in the study of the metallicity gradients.

Radial metallicity and [α/Fe] gradients for R > 7 kpc, at different distances from the plane when only giants are considered.

5. Chemo-kinematical analysis

In this section, we present the large-scale chemo-kinematical properties of the Medium Quality and High Quality samples presented in Sect. 2.5. We imposed additional conditions on the quality of the astrometric parameters (see also A.1) to ensure the use of reliable kinematical velocities. In particular, we selected stars with both five- and six-parameter astrometric solutions and a quality index RUWE < 1.4. In addition, duplicated sources have been rejected. We also performed this analysis by means of the trigonometric distances, rϖ, from the ACS (see Appendix A). No significant difference was detected when using the trigonometric distances with respect to the chemo-kinematical distributions presented in the following sections.

The considered spatial range in this section covers the inner disc up to R = 16 kpc, as well as vertical distances from the Galactic plane in the range −6 < Z < +6 kpc.