| Issue |

A&A

Volume 557, September 2013

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A22 | |

| Number of page(s) | 24 | |

| Section | Interstellar and circumstellar matter | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201321674 | |

| Published online | 20 August 2013 | |

Herschel–PACS observations of shocked gas associated with the jets of L1448 and L1157⋆,⋆⋆

1 Osservatorio Astronomico di Roma, via di Frascati 33, 00040 Monteporzio Catone, Italy

e-mail: gina.santangelo@oa-roma.inaf.it

2 Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri, Largo Enrico Fermi 5, 50125 Florence, Italy

3 LERMA, Observatoire de Paris, UMR 8112 of the CNRS, 61 Av. de l’Observatoire, 75014 Paris, France

4 Kavli Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics, Peking University, Yi He Yuan Lu 5, Hai Dian Qu, 100871 Beijing, PR China

5 Department of Earth and Space Sciences, Chalmers University of Technology, Onsala Space Observatory, 439 92 Onsala, Sweden

6 Observatorio Astronómico Nacional (IGN), Alfonso XII 3, 28014 Madrid, Spain

7 Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, PO Box 9513, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands

8 Max Planck Institut für Extraterrestrische Physik, Giessenbachstrasse 1, 85748 Garching, Germany

Received: 9 April 2013

Accepted: 21 June 2013

Aims. In the framework of the Water In Star-forming regions with Herschel (WISH) key program, several H2O (Eu > 190 K), high-J CO, [Oi], and OH transitions are mapped with Herschel-PACS in two shock positions along two prototypical outflows around the low-luminosity sources L1448 and L1157. Previous Herschel-HIFI H2O observations (Eu = 53−249 K) are also used. The aim is to derive a complete picture of the excitation conditions at the selected shock positions.

Methods. We adopted a large velocity gradient analysis (LVG) to derive the physical parameters of the H2O and CO emitting gas. Complementary Spitzer mid-IR H2 data were used to derive the H2O abundance.

Results. Consistent with other studies, at all selected shock spots a close spatial association between H2O, mid-IR H2, and high-J CO emission is found, whereas the low-J CO emission traces either entrained ambient gas or a remnant of an older shock. The excitation analysis, conducted in detail at the L1448-B2 position, suggests that a two-component model is needed to reproduce the H2O, CO, and mid-IR H2 lines: an extended warm component (T ~ 450 K) is traced by the H2O emission with Eu = 53−137 K and by the CO lines up to J = 22−21, and a compact hot component (T = 1100 K) is traced by the H2O emission with Eu > 190 K and by the higher-J CO transitions. At L1448-B2 we obtain an H2O abundance (3−4) × 10-6 for the warm component and (0.3−1.3) × 10-5 for the hot component and a CO abundance of a few 10-5 in both components. In L1448-B2 we also detect OH and blue-shifted [Oi] emission, spatially coincident with the other molecular lines and with [Feii] emission. This suggests a dissociative shock for these species, related to the embedded atomic jet. On the other hand, a non-dissociative shock at the point of impact of the jet on the cloud is responsible for the H2O and CO emission. The other examined shock positions show an H2O excitation similar to L1448-B2, but a slightly higher H2O abundance (a factor of ~4).

Conclusions. The two gas components may represent a gas stratification in the post-shock region. The extended and low-abundance warm component traces the post-shocked gas that has already cooled down to a few hundred Kelvin, whereas the compact and possibly higher-abundance hot component is associated with the gas that is currently undergoing a shock episode. This hot gas component is more affected by evolutionary effects on the timescales of the outflow propagation, which explains the observed H2O abundance variations.

Key words: stars: formation / stars: low-mass / ISM: jets and outflows / ISM: molecules / ISM: individual objects: L1448 / ISM: individual objects: L1157

Herschel is an ESA space observatory with science instruments provided by European-led Principal Investigator consortia and with important participation from NASA.

Appendix A is available in electronic form at http://www.aanda.org

© ESO, 2013

1. Introduction

During the earliest stages of star formation, young stars produce fast collimated jets, that collide with the dense parent cloud generating strong interstellar shocks. These processes strongly modify the chemical composition of the surrounding gas and are identified by intense line emission. Among the different tracers of shocks, water is a key molecule and a unique diagnostic tool of local conditions and energetic processes occurring in star-forming regions (e.g. van Dishoeck et al. 2011), since its abundance varies by many orders of magnitude during the shock lifetime (e.g. Bergin et al. 1998). In particular, water abundance with respect to H2 is expected to increase from <10-7 in cold regions to about 10-4 in the warm gas, due to the combined effects of evaporation of icy mantles and high-temperature chemical reactions which drive all the atomic oxygen into H2O.

Space instruments, such as SWAS, Odin, and ISO, have allowed the study of water in outflows. It was possible to resolve the water line profiles (e.g. Benedettini et al. 2002; Bjerkeli et al. 2009), to derive the excitation conditions of the emitting gas (e.g. Liseau et al. 1996; Ceccarelli et al. 1998; Nisini et al. 1999, 2000) and to measure the water abundance in shocks through comparison with CO emission. In particular, values within the range ~10-7 − 10-4 have been derived for the H2O abundance showing that it depends on the gas temperature and velocity (e.g. Giannini et al. 2001; Franklin et al. 2008). However, the limited spatial and spectral resolution of these instruments have prevented a clear association of the shocked gas with a specific kinematical component and with a specific region along the outflow, thus preventing the origin of the shocked gas from being derived. Thanks to the Herschel Space Observatory, we are now able to improve our view of the shock processes occurring during the very early stages of star formation and to test the model predictions for the water formation and abundance during these processes.

In this context, the low-luminosity Class 0 protostellar systems L1448 (7.5 L⊙) and L1157 (4 L⊙) are excellent targets. At the distance of 232 pc (Hirota et al. 2011), L1448 is the prototype of a source driving a molecular jet (Eislöffel 2000). It has a powerful and highly collimated outflow, which has been extensively studied (e.g. Guilloteau et al. 1992; Bachiller et al. 1995; Hirano et al. 2010). Gas excited in shocks has been detected along the outflow through near- and mid-IR emission of molecular hydrogen (e.g. Neufeld et al. 2009; Giannini et al. 2011). At a distance of 250 pc, L1157 is perhaps the most active outflow from a chemical point of view (Bachiller & Perez Gutierrez 1997; Bachiller et al. 2001), often quoted as being the prototype of the so-called chemically rich outflows. Detailed Herschel observations of the L1157 outflow by the Chemical HErschel Surveys of Star forming regions (CHESS) program have been presented by Codella et al. (2010); Lefloch et al. (2010); Codella et al. (2012a,b); Benedettini et al. (2012); Lefloch et al. (2012).

The Herschel key program Water In Star-forming regions with Herschel (WISH, van Dishoeck et al. 2011) employed more than 400 hours of telescope time to observe H2O and related molecules toward about 80 protostars at different evolutionary stages and masses to study the physical and chemical conditions of the gas in nearby star-forming regions. Within the WISH framework, several results concerning outflows have been presented (e.g. Bjerkeli et al. 2011; Kristensen et al. 2011, 2012; Bjerkeli et al. 2012; Herczeg et al. 2012; Tafalla et al. 2013). Both the L1448 and L1157 outflows have been mapped to study the spatial distribution of water and the results have been presented by Nisini et al. (2010a) for the L1157 outflow and Nisini et al. (2013) for the L1448 outflow. They show a clumpy water distribution, with emission peaks corresponding to shock positions along the outflow. Multi-transition observations (with excitation energies ranging from 53 to 249 K), performed with the Heterodyne Instrument for the Far Infrared (HIFI, de Graauw et al. 2010) toward two shock positions of each outflow, have been presented by Vasta et al. (2012) for the L1157 outflow and by Santangelo et al. (2012) for the L1448 outflow to constrain the water excitation conditions. These studies have shown strong variations of the H2O line profiles with excitation, which indicate that gas components with different physical and excitation conditions coexist at the shock positions. Complex line profiles have also been observed at the position of the central driving source of the L1448 outflow by Kristensen et al. (2012), with a broad velocity component possibly associated with the interaction of the outflow with the protostellar envelope and the extreme high-velocity gas (EHV) associated with the collimated molecular jet.

In this context as part of the WISH key program, we report here on the results of new Herschel observations of the same shock regions along the L1448 and L1157 outflows. A set of high excitation H2O lines and several transitions of CO, OH, and [Oi] have been mapped with the Photodetecting Array Camera and Spectrometer (PACS, Poglitsch et al. 2010) instrument. Unlike the previous HIFI observations, the PACS data will allow us to detect and characterize the higher excitation gas with a higher angular resolution, thus providing a complete and consistent picture of the shocked gas along the two outflows. This in turn will allow us to settle the conditions for water formation and to explore its ability to probe specific excitation regimes.

The paper is organized as follows. The PACS observations are described in Sect. 2. In Sect. 3 we present the PACS maps and the main observational results. A detailed analysis of the PACS maps is discussed in Sect. 4, starting from the study of the physical and excitation conditions in the B2 shocked position along the L1448 outflow and subsequently discussing the implications for the other selected shocked spots. The results are discussed in Sect. 5, in the context of current shock models. Finally, the conclusions are presented in Sect. 6.

2. Observations and data reduction

We performed a survey of key far-IR lines with the PACS instrument on board Herschel (Pilbratt et al. 2010; Poglitsch et al. 2010) toward two shock spots along each interested outflow (see Fig. 1): the B2 and R4 spots along L1448 (hereafter L1448-B2 and L1448-R4, respectively; Bachiller et al. 1990); and B2 and R along L1157 (hereafter L1157-B2 and L1157-R, respectively; Bachiller et al. 2001). The PACS instrument is an integral field unit (IFU), consisting of a 5 × 5 array of spatial pixels (hereafter spaxels). Each spaxel covers 9.′′4 × 9.′′4, providing a total field of view of 47′′ × 47′′.

|

Fig. 1 PACS H2O 179 μm images of L1448 and L1157 (Nisini et al. 2010a, 2013). The PACS line survey positions are indicated for L1448-B2 and R4 with crosses, for L1157-B2 and R with triangles. The field of view of the PACS observations is displayed as a box at the selected positions. CO(3 − 2) and SiO(3 − 2) emissions for L1448 and L1157, respectively, are superimposed on the H2O maps. |

The line spectroscopy mode was used to cover short spectral regions and thus observe selected lines at the interested shock positions. The line survey comprises ortho- and para-H2O transitions with excitation energies ranging from 194 to 396 K. In addition, high-J CO, [Oi], and OH lines have been observed (see Table 1 for a summary of the targeted lines). These observations are complementary to observations of lower excitation H2O transitions (Santangelo et al. 2012; Vasta et al. 2012) conducted with the HIFI heterodyne instrument (de Graauw et al. 2010) with excitation energies ranging from 53 to 249 K, and to PACS maps of the H2O 212 − 101 line at 179.5 μm along the two outflows (Nisini et al. 2010a, 2013, see also Fig. 1).

Fluxes of the lines observed with PACS and relative 1σ errors in parentheses.

The data were processed with the ESA-supported package Herschel interactive processing environment1 (HIPE, Ott 2010) version 4.2 (except for the data relative to the L1157-R position that were processed with HIPE version 5)2. The observed fluxes were normalized to the telescope background and then converted into absolute fluxes using Neptune as a calibrator. The flux calibration uncertainty of the PACS observations is 30%, based on the flux repeatability for multiple observations of the same target in different programs and on cross-calibration with HIFI and ISO. Further data reduction, to obtain continuum subtracted line maps, and the analysis of the data were performed using IDL and the GILDAS3 software.

The Herschel diffraction limit at 179 μm is 12.′′6 and for wavelengths below 133 μm it is smaller than the PACS spaxel size of 9.′′4. To correct for the different beam sizes in the excitation analysis presented in Sect. 4, we convolved all maps to the resolution of the transition with the longest wavelength, that is 12.′′6 at 179 μm, and then extracted the fluxes at each selected shock spot.

3. Results

The PACS spectra of all the lines detected in the four examined shocked positions are presented in Appendix A, whereas a summary of the main line parameters is given in Table 1, along with the fluxes of the detected lines. The source L1448-B2 represents the position in which we detected the largest number of lines and it is the only position where we detected the OH fundamental line at 119 μm.

|

Fig. 2 Overlay between PACS H2O 303 − 212 (174 μm), H2O 221 − 110 (108.1 μm), [Oi] |

|

Fig. 3 Same as in Fig. 2, but for the L1157 outflow. Contours are displayed for IRAM-30 m CO(2 − 1) and SiO(3 − 2) emission (HPBW equal to 11′′ and 18′′, respectively) from Bachiller et al. (2001) and are traced in steps of 5σ, starting from 5σ. Spitzer-IRAC 8 μm emission and Spitzer-IRS H2 S(1) emission at 17 μm from Neufeld et al. (2009) are shown. |

The original PACS maps of selected lines, not convolved to a common angular resolution, are shown in Figs. 2 and 3, respectively, for L1448 and L1157. The figures present the overlay between the H2O 303 − 212 (174 μm), H2O 221 − 110 (108.1 μm), CO(16 − 15), [Oi]  (63.2 μm), OH (119 μm) emission, and other tracers from complementary observations. Along the L1448 outflow several interesting features can be noticed. In particular, the peak of the H2O emission at L1448-B2 is at the apex of the bow-shock, as traced by the H2 emission at 2.12 μm, and at L1448-R4 it corresponds to the peak of the IRAC 8 μm emission. We found no shift at this angular resolution between the H2O emission at 174 μm and CO(16 − 15) emission, both in L1448-B2 and L1448-R4, which indicates that at this angular resolution high-J CO and H2O are spatially coincident and trace shocked gas.

(63.2 μm), OH (119 μm) emission, and other tracers from complementary observations. Along the L1448 outflow several interesting features can be noticed. In particular, the peak of the H2O emission at L1448-B2 is at the apex of the bow-shock, as traced by the H2 emission at 2.12 μm, and at L1448-R4 it corresponds to the peak of the IRAC 8 μm emission. We found no shift at this angular resolution between the H2O emission at 174 μm and CO(16 − 15) emission, both in L1448-B2 and L1448-R4, which indicates that at this angular resolution high-J CO and H2O are spatially coincident and trace shocked gas.

The bottom-right panel relative to L1448-B2 shows the comparison between H2O and CO(3 − 2). For CO, the EHV gas (i.e. v ≳ − 50 km s-1, Bachiller et al. 1990) has been separated from the standard outflow high-velocity (HV, v ≲ − 40 km s-1) gas emission. We see that the HV gas is totally uncorrelated with the water emission, a result already found in other studies (Santangelo et al. 2012; Nisini et al. 2013; Tafalla et al. 2013). The EHV gas, on the other hand, has a peak shifted north-west with respect to the H2O peak. Thus, the low-J CO emission traces entrained ambient gas and not the shocked gas, independent of the velocity components.

Finally, we do not see any significant spatial shift at this angular resolution between the peaks of H2O, [Oi], and [Feii] emission, although the H2O emission appears to be more extended than [Oi] and [Feii]. Nevertheless, at the L1448-B2 position, and possibly at the adjacent spaxels along the outflow direction, a hint of a velocity shift in the [Oi] line at 63 μm was detected: the line is blue-shifted by ~80 km s-1 (see Fig. A.1), which is comparable with the resolution element of PACS at this wavelength (~90 km s-1). Similar [Oi] velocity shifts have been found in HH46 by van Kempen et al. (2010a) and in Serpens SMM1 by Goicoechea et al. (2012), who suggested the presence of fast dissociative shocks close to the protostar, related with an embedded atomic jet. Moreover, Karska et al. (2013) analysed PACS spectra of a large sample of Class 0/I protostars and they found such profile shifts toward at least 1/3 of their targets. We point out that Fe has a ionization potential of 7.9 eV and thus we expected to find [Feii] co-spatial with [Oi] (ionization potential of 13.6 eV).

A much smaller number of lines was detected along the L1157 outflow. In particular, only four lines were detected at L1157-B2. Here the emission is elongated in the outflow direction, according to all tracers. Similarly to L1448, the H2O emission at 174 μm is spatially associated with the [Oi]  emission at 63.2 μm and the CO(16 − 15) emission. Two emission peaks can be identified in the PACS maps: the brightest one is found at the central spaxel and is spatially associated with the H2 emission, as seen from the overlay with the Spitzer-IRAC image at 8 μm; the other emission peak is at a position offset of (12′′,− 18′′) from the central spaxel, close to the edge of the PACS map. The SiO(3 − 2) emission (Bachiller et al. 2001) also appears to be elongated along the outflow direction with a peak roughly corresponding to the central spaxel of the PACS maps. On the other hand, the CO(2 − 1) emission is not spatially associated with any other molecular species. At L1157-R a bright emission peak is seen in H2O and in all species observed with PACS. This H2O peak is shifted with respect to the central spaxel of (2′′, − 9′′) and is spatially associated with the H2 emission. A second peak is found in the [Oi]

emission at 63.2 μm and the CO(16 − 15) emission. Two emission peaks can be identified in the PACS maps: the brightest one is found at the central spaxel and is spatially associated with the H2 emission, as seen from the overlay with the Spitzer-IRAC image at 8 μm; the other emission peak is at a position offset of (12′′,− 18′′) from the central spaxel, close to the edge of the PACS map. The SiO(3 − 2) emission (Bachiller et al. 2001) also appears to be elongated along the outflow direction with a peak roughly corresponding to the central spaxel of the PACS maps. On the other hand, the CO(2 − 1) emission is not spatially associated with any other molecular species. At L1157-R a bright emission peak is seen in H2O and in all species observed with PACS. This H2O peak is shifted with respect to the central spaxel of (2′′, − 9′′) and is spatially associated with the H2 emission. A second peak is found in the [Oi]  emission (63.2 μm), at a position offset of (− 12′′,8′′) from the central spaxel, and is also visible in H2O. On the other hand, the SiO(3 − 2) emission peaks at the central spaxel position, thus offset from the H2O emission. Finally, the CO(2 − 1) emission is more diffuse than the other tracers and has an emission peak at the central spaxel position, thus shifted with respect to the H2O and high-J CO emission.

emission (63.2 μm), at a position offset of (− 12′′,8′′) from the central spaxel, and is also visible in H2O. On the other hand, the SiO(3 − 2) emission peaks at the central spaxel position, thus offset from the H2O emission. Finally, the CO(2 − 1) emission is more diffuse than the other tracers and has an emission peak at the central spaxel position, thus shifted with respect to the H2O and high-J CO emission.

In conclusion, the inspection of the PACS maps highlights the following results: in both outflows the H2O emission is spatially associated with mid-IR H2 emission and high-J CO emission, whereas the low-J CO emission seems to be associated with a different gas component. Our findings are consistent with the results obtained by Nisini et al. (2010a, 2013) from mapping the H2O 212 − 101 emission along the L1448 and L1157 outflows and by Tafalla et al. (2013) from the analysis of H2O 110 − 101 and 212 − 101 emission in a large sample of shocked positions. Moreover, Karska et al. (2013) found a tight correlation between H2O 212 − 101 at 179 μm and high-J CO line fluxes, concluding that they likely arise in the same gas component. The SiO emission appears to be slightly shifted with respect to H2O, consistent with the two gas components tracing shock regions with different excitation conditions, as discussed in Santangelo et al. (2012) and Vasta et al. (2012). Finally, no shift is observed at the PACS angular resolution between the [Oi] and [Feii] lines and the H2O emission.

|

Fig. 4 Upper: rotational diagram at L1448-B2 for the H2 emission lines detected with Spitzer by Giannini et al. (2011). The values have been derived from the H2 fluxes integrated over a 13′′ area for comparison with the PACS data. The black dots are the observed values, whereas the empty dot represents the H2 S(1) line corrected for an ortho-to-para ratio equal to 1 (see Giannini et al. 2011). The green solid line represents the linear fit to the S(0)–S(3) H2 lines, while the green dotted line is the fit obtained using the S(0)–S(2) H2 lines. Finally, the blue line is the linear fit to the S(3)–S(7) lines. The resulting parameters (T,N) or range of parameters of the linear fits are reported in the diagram. Lower: H2 rotational diagram at L1157-R. The symbols are the same as in the upper panel. |

4. Analysis

In this section we discuss the excitation conditions of the observed lines, complemented with Spitzer H2 data, when available. In particular, we will concentrate our analysis on the L1448-B2 shock, where we detected the largest number of lines with high signal-to-noise ratio (S/N). Given the observed strict correlation between H2O and H2 mid-IR emission, we will first use the Spitzer H2 lines to constrain the H2O temperature. The H2O line ratios and absolute intensities will then be used to derive the density and column density of the gas and the size of the emitting region. The physical parameters derived for H2O are then used for the CO emission and both H2O and CO abundances with respect to H2 are estimated. Finally, the emission at the other shock spots with respect to the excitation conditions in L1448-B2 will be discussed.

4.1. The L1448-B2 shock

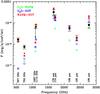

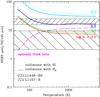

4.1.1. H2 rotational diagram

We used Spitzer H2 observations by Giannini et al. (2011) and converted the H2 intensities, averaged in a 13′′ beam, into column densities (Nu) to construct the H2 rotational diagram, which is presented in the upper panel of Fig. 4. The fluxes have not been corrected for visual extinction, since it is only a marginal effect (AV = 6 mag for L1448 Giannini et al. 2011; Nisini et al. 2000). As explained in Giannini et al. (2011), the ortho-to-para ratio is temperature dependent: in particular, an ortho-to-para ratio close to 1 is found for the low-J transitions that trace gas at T ≲ 400 K, while the high temperature equilibrium value of 3 is reached by the lines with J larger than 3.

The fact that the observed transitions do not align on a single straight line on the rotational diagram indicates that gas components at different temperatures are present within the spatial resolution element or along the line of sight. In particular, two temperature components can be identified in the diagram, in the assumption of LTE conditions: a warm component at T in the range ~350 − 450 K, where the uncertainty depends on the lines considered for the fit, i.e. the S(0)−S(2) or the S(0)−S(3) lines, and a hot component at T ~ 1100 K, by fitting the S(3) (or S(2)) to S(7) lines. The H2 column density is N(H2) ~ 0.8 − 1.2 × 1020 cm-2 for the warm component and N(H2) ~ 1.1 × 1019 cm-2 for the hot component. In conclusion, the properties of the hot component are well defined from the H2 rotational diagram, while a slightly larger range of parameters can be associated with the warm component.

4.1.2. The H2O emission

Previous HIFI observations in L1448-B2 of H2O lines with excitation energies Eu ranging from 53 to 137 K4 (Santangelo et al. 2012) are consistent with very dense gas with n(H2) ~ 106 cm-3 and T = 450 K and with moderate H2O column densities of ~3 × 1014 cm-2. The bulk of the HIFI H2O emission can be thus associated with the warm component identified from the H2 rotational diagram.

To analyse the excitation conditions of the H2O emission observed with PACS, we used the radiative transfer code RADEX (van der Tak et al. 2007) in the plane-parallel geometry, with the collisional rate coefficients from Dubernet et al. (2006, 2009) and Daniel et al. (2010, 2011), to build a grid of models with density ranging between 105 and 108 cm-3 and H2O column density between 1015 and 1018 cm-2. We adopted a typical line width Δv of 50 km s-1 (full-width at zero intensity, FWZI), from the spectrally resolved HIFI observations of H2O (Santangelo et al. 2012). An uncertainty on the assumed line width value translates into an uncertainty on the H2O column density determination, since the H2O line ratios depend on the ratio N(H2O)/Δv. An ortho-to-para ratio equal to 3 was assumed, as implied by the HIFI observations of the warm component.

|

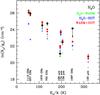

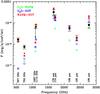

Fig. 5 Top: ratio between H2O 212 − 101 (179 μm) and 303 − 212 (174 μm) emission, as a function of T for two values of H2 density (nH2 = 5 × 105 cm-3 and 5 × 106 cm-3) and two values of H2O column density (NH2O = 3 × 1014 and 4 × 1015 cm-2) of L1448-B2. The shaded band highlights the H2O ratio observed with PACS and the arrows indicate that this ratio can be considered an upper limit (see text for details). Middle and bottom: ratios between H2O 303 − 212 (174 μm) and 313 − 202 (138.5 μm) emission and between H2O 303 − 212 (174 μm) and 404 − 313 (125.4 μm) emission, respectively, as a function of T. The symbols are the same as in the top panel. |

Figure 5 shows the ratios between H2O lines observed with PACS (having higher excitation than those observed with HIFI) as a function of temperature, for two values of H2 density and H2O column density. The warm component at T ~ 450 K does not reproduce the PACS H2O line ratios. In particular, the top panel shows the 179 μm/174 μm line ratio. The arrows in the plot indicate that the observed ratio (shaded band) is an upper limit, since the H2O 212 − 101 line (Eu ~ 114 K) is more contaminated than the H2O 303 − 212 line (Eu ~ 197 K) by the warm gas component traced by the lower excitation H2O lines observed with HIFI. The low H2O column density N(H2O) ~ 3 × 1014 cm-2, derived for the warm component from the HIFI H2O observations, does not reproduce the 179 μm/174 μm line ratio. This indicates the presence of an additional gas component with respect to the warm one traced by the bulk of the HIFI observations. In particular, a hot component with temperature higher than 600 K and H2O column density larger than a few 1015 cm-2 is required to reproduce the higher excitation H2O emission observed with PACS.

This evidence suggests that the bulk of the H2O emission observed with PACS is associated with the hot component which is seen in the H2 rotational diagram. Assuming a temperature T = 1100 K for this component from the H2 rotational diagram (see Fig. 4) and H2 density n(H2) ≥ 105 cm-3, as obtained by Giannini et al. (2011), the density and column density of this component are derived by fitting the intensity of all the PACS lines with excitation energy level Eu ≳ 190 K and varying n(H2), N(H2O) and the size of the emitting region θ. Table 2 summarizes the results of the fit: unlike the warm component, the emission region of the hot component should be compact (a few arcsec). In particular, assuming an emitting size of 1 arcsec, the hot component requires a density n(H2)~ 5 × 105 − 5 × 106 cm-3 and column density N(H2O) ~ 4 × 1015 − 2 × 1016 cm-2. The obtained column densities correspond to moderately optically thick lines (the optical depths of the H2O lines are lower than ~23, corresponding to the maxim optical depth of the 179 μm line).

A visualization of the obtained results is presented in Fig. 6, which shows the two separate models for the H2O emission, i.e. the warm and hot components, and the sum of the two models in red. The fluxes predicted by the models have been corrected for the filling factors (using  ) obtained by assuming the emitting size derived from the excitation analysis. Except for the H2O 221 − 110 line at 108.1 μm, which is over-estimated by a factor of 2.5, and the 211 − 202 line at 752 GHz, which is under-estimated by a factor of 2, all H2O lines are well reproduced by the two-component model.

) obtained by assuming the emitting size derived from the excitation analysis. Except for the H2O 221 − 110 line at 108.1 μm, which is over-estimated by a factor of 2.5, and the 211 − 202 line at 752 GHz, which is under-estimated by a factor of 2, all H2O lines are well reproduced by the two-component model.

We note that this model predicts that the hot component seen in L1448-B2 should contribute very little to the emission of the low-excitation H2O lines observed with HIFI (Santangelo et al. 2012) and indeed these lines show very similar profiles with no clear evidence of variations in shape with excitation. However, the HIFI observations of L1448-R4 and L1157-R show a different trend, with high velocity gas preferentially associated with the low-excitation lines (see Santangelo et al. 2012; Vasta et al. 2012). Nevertheless, in these cases geometrical effects related to the presence of bow shocks and self-absorption by cold H2O gas in the lines at lower excitation may contribute to modifying the line profiles.

Summary of the best-fit models derived for the two gas components at the L1448-B2 position.

|

Fig. 6 Comparison between the observed H2O fluxes (black dots) and the two best-fit models for L1448-B2, which are given in Table 2: the green model is the fit to the HIFI H2O lines and the two blue models are the extremes of the obtained density range that fits the PACS H2O lines (squares represent n(H2) = 5 × 105 cm-3 and circles represent n(H2) = 5 × 106 cm-3). The red model represents the sum of the fluxes predicted for each line by the green and the two blue models. The fluxes predicted by the models have been corrected for the relative predicted filling factors. Calibration uncertainties of 20% for the HIFI data and 30% for the PACS data have been assumed. The open triangle represents the upper limits of the HIFI H2O 312 − 303 line (Eu = 249 K). |

|

Fig. 7 H2O rotational diagram at L1448-B2. Calibration uncertainties of 20% for the HIFI data and 30% for the PACS data have been assumed. The predictions of the two best-fit models for L1448-B2, corrected for the relative predicted filling factors, are shown (see Table 2 and Fig. 6). Symbols are as in Fig. 6. |

|

Fig. 8 Rotational diagram at L1448-B2 for the CO emission lines (both the detections and the non-detections) observed with PACS (in a 12.′′6 beam) and the JCMT CO(3 − 2) line (empty symbol; beam size equal to 14′′). Calibration uncertainties of 30% have been assumed. The solid line represents the linear fit to the four detected CO lines, the dotted line the linear fit only to the three lower excitation CO lines. As in Fig. 7, the predictions of the two best-fit models for L1448-B2 corrected for the relative predicted filling factors are shown. |

Finally, Fig. 7 presents the H2O rotational diagram, with the flux predictions from the two separate models for H2O and from their sum. The models identify two gas components in the rotational diagram, with the blue one (associated with the hot component) showing more scatter than the green one (associated with the warm component), because of the larger associated optical depths. However, when the sum of the two separate models is considered, the two temperature components are no longer discernible. The total rotational ladder shows a single-temperature aspect, although the large scatter suggests that subthermal excitation and optical depth effects are significant. The rotational temperature obtained from a single-temperature fit is ~50 K, which is within the range of rotational temperatures obtained for low-mass Class 0 protostars (e.g. Herczeg et al. 2012; Goicoechea et al. 2012; Karska et al. 2013).

|

Fig. 9 Same comparison presented in Fig. 6, but for the CO fluxes measured with PACS toward L1448-B2 (both the detections and the non-detections). The two blue models represent the extremes of the density range derived from the H2O excitation analysis. |

4.1.3. The CO emission

Figure 8 shows the CO rotational diagram obtained by converting the fluxes of the high-J CO lines observed with PACS and the CO(3−2) line observed with the JCMT telescope (beam size equal to 14′′) into column densities (Nu). A global fit to the PACS CO lines reveals a gas with rotational temperature T ~ 290 K and CO column density, averaged in the 12.′′6 beam, of N(CO) ~ 1015 cm-2. This is consistent with the warm gas component identified from the H2 rotational diagram and associated with the bulk of the H2O emission observed with HIFI. Although only four CO lines have been detected with PACS, a hint of a possible curvature occurs at excitation energies Eu ≥ 1000 K, since the CO(24 − 23) transition lies above the straight line followed by the other PACS lines. If we assume that this line comes from a different gas component, a slightly lower temperature T ~ 240 K is found from the lower excitation PACS lines and correspondingly N(CO) ~ 2 × 1015 cm-2. The same diagram shows that the CO(3 − 2) line lies well above the other CO lines, which is consistent with its origin in a colder gas.

The presence of multiple excitation temperature components in the CO emission has been found by other studies of CO ladders in low-mass Class 0 protostars and their outflows (see e.g. van Kempen et al. 2010b; Benedettini et al. 2012; Goicoechea et al. 2012; Herczeg et al. 2012; Yıldız et al. 2012, 2013; Karska et al. 2013; Manoj et al. 2013). In particular, Karska et al. (2013) present CO rotational diagrams for a large sample of protostars, showing two distinct components, a warm component with Trot ~ 300 K and a hot component with Trot ~ 700 K, in addition to a cold component with Trot ~ 100 K, observed in the J ≲ 14 lines (Goicoechea et al. 2012; Yıldız et al. 2012, 2013). They found the break between warm and hot gas in the CO diagrams around Eu ~ 1500 K. Thus, the presence of different components in our PACS CO data, a warm and a hot component, is probably valid and may reflect true differences in the excitation conditions of the gas traced by the different ranges of CO transitions in Class 0 sources.

We can then use the physical conditions derived for the warm and hot H2O components to verify whether they are able to reproduce our PACS CO observations. The comparison is presented in Fig. 9. In particular, we used the temperature and density derived from the H2O analysis to fit the CO line ratios, normalizing the warm component to the CO(16−15) line and deriving the CO column density of the hot component so that the sum of the two components (warm plus hot) reproduced the observed CO fluxes and upper limits. The CO column densities derived in this fashion are reported in the last column of Table 2. The two blue models in Fig. 9 for the hot gas component represent the extremes of the density range obtained from the H2O excitation analysis (see Table 2). We obtained N(CO)= (1.5−3) × 1016 cm-2 for the hot gas component and N(CO)= 3 × 1015 cm-2 for the warm component, both averaged over the relative emitting size.

To summarize, the CO and H2O line ratios trace two gas components, a warm gas component at T ~ 450 K (with n(H2) = 106 cm-3), which is visible in the H2O emission with Eu = 53−137 K and the PACS CO data up to J = 22−21, and a hot gas component at T ~ 1100 K (with n(H2) = (0.5 − 5) × 106 cm-3), which is traced by the H2O observations with Eu > 190 K and the PACS higher-J CO emission. These two gas components are associated with a warm and hot component, respectively, in the Spitzer mid-IR H2 emission.

4.1.4. H2O and CO abundance ratios

A direct estimate of the H2O and CO abundances with respect to H2 for both gas components can be obtained by comparing the column density of these species, averaged over a 13′′ beam. We find an [H2O]/[H2] abundance ratio of (3 − 4) × 10-6 for the warm component and (0.3 − 1.3) × 10-5 for the hot component. The inferred H2O abundances are much higher than the typical value of ~10-9 − 10-8, which is found in cold interstellar clouds (e.g. Caselli et al. 2010). However, even for the hot component, this is lower than ~10-4, which is the value expected in hot shocked gas (e.g. Kaufman & Neufeld 1996; Flower & Pineau Des Forêts 2010). The derived H2O abundances for the warm component are consistent with the values obtained by Santangelo et al. (2012); Vasta et al. (2012); Nisini et al. (2013) from HIFI velocity-resolved observations. In particular, Nisini et al. (2013), from the analysis of H2O 212 − 101 and 110 − 101 maps of L1448, derived a relatively constant water abundance along the outflow of about (0.5 − 1) × 10-6, with an increase by roughly one order of magnitude at the protostar position. Similarly, low H2O abundances in the warm gas have been derived in other outflows by several authors (e.g. Bjerkeli et al. 2012; Tafalla et al. 2013).

On the other hand, we derive a [CO]/[H2] abundance of (3 − 4) × 10-5 for the warm component and (1 − 2) × 10-5 for the hot component. The derived [CO]/[H2] abundances do not depend on the emitting size, because both CO and H2 lines are optically thin; therefore, their absolute intensity depends on the beam diluted column density.

Our data suggest that the CO abundance is lower by a factor from 3 to 10 with respect to the canonical value of 2.7 × 10-4 measured for dense interstellar clouds (e.g. Lacy et al. 1994). Shocks that are non-dissociative, like those implied by our molecular observations (see Sect. 5), are not expected to alter the original CO/H2 abundance ratio in the cloud. We point out however that a CO abundance less than the canonical value has been recently measured in different environments, including the inner envelopes of low- and intermediate-mass protostars (e.g. Yıldız et al. 2010, 2012; Fuente et al. 2012) and toward the Orion region (Wilson et al. 2011), which indicates that such low values are indeed not peculiar to the considered shock regions.

By comparing the H2O and CO column densities, we find a [H2O]/[CO] abundance ratio of 0.1 for the warm and 0.1 − 1.3 for the hot component. Thus, an estimate of the H2O abundance, based on the assumption that the CO abundance with respect to H2 is equal to 10-4, would lead to higher values for the hot component (about 1 − 13 × 10-5). For this reason our obtained H2O abundance values are different from those obtained previously from ISO observations (e.g. Nisini et al. 1999, 2000; Giannini et al. 2001): our analysis points to a CO abundance with respect to H2 lower than the standard value of 10-4 for the hot component and correspondingly to a lower H2O abundance.

4.1.5. The spatial extent of the warm and hot components

According to the excitation analysis, different sizes are associated with the two H2O gas components: the warm gas is found to be rather extended (17′′), while the hot gas should be compact (<5′′). Based on our model, from Fig. 6 we expect the contribution of the warm component to the total H2O flux at 179 μm to be similar or stronger than that of the hot component, whereas at 174 μm the hot component dominates the H2O emission with little contribution from the warm component. One way of studying the spatial extent of the two components and verifying the results obtained from our analysis is to use the maps of these two H2O lines (179 and 174 μm), which are also the strongest H2O lines we detected with PACS, and analyse the relative contribution of the two predicted components from their line ratio. In particular, we expect the ratio between the 179 μm and the 174 μm H2O lines to increase going from the central position outwards, thanks to the dominant contribution of the compact central component to the H2O 174 μm flux.

Figure 10 presents the ratio between the PACS maps of the two H2O lines (at 179 μm and 174 μm). As predicted by our excitation analysis, the H2O line ratio increases going from the centre of the map toward the edges in both directions along the outflow. This result supports the scenario in which two gas components coexist: a compact component which dominates the H2O emission above Eu ~ 190 K and an extended component that dominates the H2O emission at lower excitation energies.

4.2. Excitation conditions and water abundance at the other shocked positions

At the other selected shock spots a detailed analysis like the one we performed for L1448-B2 is precluded because of the smaller number of lines, the lower S/N of the detections, and the lack of H2 data that would allow us to get a direct measure of the water abundance. The only other position, among the selected ones, where Spitzer spectroscopic data are available is L1157-R (Nisini et al. 2010b). Therefore, at this position an estimate of the water abundance can be obtained in a similar fashion.

The rotational diagram, constructed in L1157-R from the Spitzer mid-IR data (see lower panel of Fig. 4), shows once more the presence of two gas components: a warm component at a temperature of about T ~ 420 K and a hot component with T ~ 800 − 850 K. The break is found at approximately 2000 K. The corresponding H2 column densities are N(H2) ~ 1.2 × 1020 cm-2 for the warm component and N(H2) ~ (0.7 − 1.3) × 1019 cm-2 for the hot component, both averaged over 13′′.

As we did for L1448-B2, we assume that the bulk of the H2O emission observed with PACS is associated with the hot component identified from the H2 rotational diagram, and we adopt a RADEX analysis to derive the excitation conditions of this hot component. In particular, we derived the H2 density, the H2O column density, and the emitting size by fitting the PACS H2O lines with excitation energy level Eu ≳ 190 K, under the assumption of a temperature T ~ 800 − 850 K from the H2 data and a line width of 25 km s-1 from the HIFI observations by Vasta et al. (2012).

|

Fig. 10 Ratio between the H2O 212 − 101 map at 179 μm and the 303 − 212 map at 174 μm for L1448-B2. The ratio is shown only above a 5σ detection level in both maps. The crosses represent the pointing of the 25 spaxels. |

A compact gas component is found to be associated with the bulk of the PACS emission, with n(H2) ~ (0.1−5) × 106 cm-3 and N(H2O) ~ (0.2−6) × 1016 cm-2. The obtained excitation conditions appear to be similar to those derived for the hot component at L1448-B2, but a larger uncertainty on the H2O column densities is associated with L1157-R. The corresponding abundance, obtained by comparing the H2O column densities (corrected for the relative filling factor) with the H2 column density, is in the range (0.1 − 5) × 10-5 (see Sect. 4.1.4 for comparison).

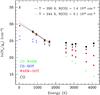

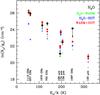

For the remaining two shock spots, namely L1448-R4 and L1157-B2, the lack of mid-IR H2 data in both cases does not allow us to get constraints on the temperature and to estimate the H2O abundance. To investigate the physical and excitation conditions of the hot gas component at these positions, we used the L1448-B2 shock position as a template and compared the ratios of the detected lines with the relative line ratios observed in L1448-B2. The comparison is presented for all the selected shock spots in Fig. 11, where all the line ratios are normalized with respect to the H2O 303 − 212 line at 174 μm. The observed H2O line ratios are roughly comparable within the relative errors with those observed in L1448-B2, within a factor of 2. We can thus conclude that the excitation conditions of the hot gas component are comparable in all selected shock positions, as already deduced for L1157-R. We note that the bright H2O 179/174 μm line ratio at the L1157-B2 shock position may provide evidence for an older shock with respect to the other selected positions. Because this line ratio is indicative of the relative contribution between the warm and the hot component, the high value observed at L1157-B2 may suggest a smaller contribution of the hot component relative to the warm component compared to the other shock positions. This is consistent with this position being the signpost of an older shock, as already suggested by previous studies (e.g. Bachiller & Perez Gutierrez 1997; Rodríguez-Fernández et al. 2010; Vasta et al. 2012). Assuming a constant shock propagation velocity, Gueth et al. (1998) derived a dynamical age for the L1157-B2 shock spot of ~ 3000 yr, which is larger than or similar to the typical cooling time of J-type and C-type shocks (≲ 102 − 103 yr, respectively, Flower & Pineau Des Forêts 2010). Therefore, in L1157-B2 the hot component has already had the time to cool down to a few hundred Kelvin.

|

Fig. 11 Line ratios between the H2O, CO, [Oi], and OH lines and the H2O 303 − 212 line at 174 μm at all selected shock positions. 1σ errors are indicated with errorbars. |

|

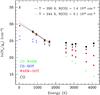

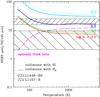

Fig. 12 Optically thin [Oi]63 μm/[Oi]145 μm flux ratios as a function of temperature are shown in dotted lines for collisions with atomic hydrogen H and in solid lines for collisions with molecular hydrogen H2 (as in Liseau et al. 2006). The logarithms of the density (in cm-3) are indicated for each curve. The broken line outlines the ratio of optically thick lines. Observed line ratios are depicted by the shaded areas for the L1448-B2 position and the L1157-R position. The data have been smoothed to a common angular resolution of 12.′′6. |

Figure 11 shows that CO/H2O line ratios lower by a factor of ~4 with respect to L1448-B2 are found at all other positions. Under the assumption of similar H2O excitation conditions, this would suggest a higher H2O abundance with respect to L1448-B2, which is in line with the range estimated for L1157-R using Spitzer mid-IR H2 data.

The L1448-R4 and L1157-B2 shock positions thus appear to be more similar to L1157-R than to L1448-B2 in terms of H2O abundance. This conclusion is supported by the PACS detection at L1448-B2 of OH and brighter [Oi] emission (see Fig. 11), which suggests either that not all oxygen has been converted into H2O or that water is partially dissociated. Indeed, the L1448-B2 shock position is intrinsically peculiar with respect to all the other selected positions, since it is close to the driving outflow source. Thus, this position may be affected by the strong UV radiation field coming from the central protostar or from dissociative internal jet shocks (e.g. Hollenbach & McKee 1989; van Kempen et al. 2009), which can photodissociate the freshly formed H2O.

4.3. The [Oi] ratio

It is useful to compare the observed ratio between the [Oi]  line at 63.2 μm and the [Oi]

line at 63.2 μm and the [Oi]  line at 145.5 μm to infer additional information on the gas excitation conditions (see Liseau et al. 2006). We detected both [Oi] lines only at the L1448-B2 and L1157-R positions (at the latter position the [Oi] line at 145 μm was detected only at ~2σ level) and the measured [Oi]63/145 μm ratios are ~20 and ~6, respectively. The observed line ratios are displayed in Fig. 12, along with the line ratios predicted from the RADEX code assuming optically thin lines, for collisions with atomic hydrogen or with molecular hydrogen; the predicted line ratio for optically thick lines is also shown. We have neglected O excitation due to collisions with electrons, since it becomes relevant (i.e. it contributes more than 10%) only for n(e)/n(H) fractions larger than 0.6, clearly in contrast with the mostly molecular/atomic gas observed in the considered shocks. Thus, assuming optically thin lines excited by collisions with H2, the ratio observed at L1448-B2 is consistent with a H2 volume density between 105 and a few 105 cm-3 and a temperature T ≳ 100 K, which is within the range of parameters derived from our excitation analysis (see Sects. 4.1.2 and 4.1.3). On the other hand, assuming collisions with H, it corresponds to n(H) ~ 103 − 104 cm-3 and T ≳ 100 K. We can thus distinguish two possibilities for the origin of the [Oi] emission at L1448-B2: either H2O, CO, and [Oi] emission arise from the same molecular gas with density n(H2) ~ 5 × 105 cm-3, or the [Oi] emission originates in a low-density component of atomic gas. This will be discussed further in Sect. 5. Instead, the lower line ratio measured at L1157-R is consistent either with n(H2) ~ 103 − 104 cm-3 and T ≳ 200 K for optically thin lines excited by collisions with H2, or with optically thick lines and temperatures lower than 200 K.

line at 145.5 μm to infer additional information on the gas excitation conditions (see Liseau et al. 2006). We detected both [Oi] lines only at the L1448-B2 and L1157-R positions (at the latter position the [Oi] line at 145 μm was detected only at ~2σ level) and the measured [Oi]63/145 μm ratios are ~20 and ~6, respectively. The observed line ratios are displayed in Fig. 12, along with the line ratios predicted from the RADEX code assuming optically thin lines, for collisions with atomic hydrogen or with molecular hydrogen; the predicted line ratio for optically thick lines is also shown. We have neglected O excitation due to collisions with electrons, since it becomes relevant (i.e. it contributes more than 10%) only for n(e)/n(H) fractions larger than 0.6, clearly in contrast with the mostly molecular/atomic gas observed in the considered shocks. Thus, assuming optically thin lines excited by collisions with H2, the ratio observed at L1448-B2 is consistent with a H2 volume density between 105 and a few 105 cm-3 and a temperature T ≳ 100 K, which is within the range of parameters derived from our excitation analysis (see Sects. 4.1.2 and 4.1.3). On the other hand, assuming collisions with H, it corresponds to n(H) ~ 103 − 104 cm-3 and T ≳ 100 K. We can thus distinguish two possibilities for the origin of the [Oi] emission at L1448-B2: either H2O, CO, and [Oi] emission arise from the same molecular gas with density n(H2) ~ 5 × 105 cm-3, or the [Oi] emission originates in a low-density component of atomic gas. This will be discussed further in Sect. 5. Instead, the lower line ratio measured at L1157-R is consistent either with n(H2) ~ 103 − 104 cm-3 and T ≳ 200 K for optically thin lines excited by collisions with H2, or with optically thick lines and temperatures lower than 200 K.

Finally, in both positions the [Oi] column density averaged over the PACS beam is of the order of 2 − 5 × 1015 cm-2 at L1448-B2 and 5 − 10 × 1015 cm-2 at L1157-R, which is consistent with optically thin lines.

5. Comparison with shock models

The observed fluxes are compared with the grid provided by Flower & Pineau Des Forêts (2010) for stationary C- and J-type shock models. The grid explores a range of shock velocities from 10 to 40 km s-1 and two pre-shock densities, 2 × 104 and 2 × 105 cm-3. In the upper panel of Fig. 13 we present the observed flux of the [Oi]  line at 63.2 μm with the shock model predictions. Unsmoothed peak line fluxes have been used to minimize beam dilution effects. At the L1448-B2 position only a J-type shock, with velocity vs > 20 km s-1 for pre-shock density n = 2 × 104 cm-3 and vs > 10 km s-1 for n = 2 × 105 cm-3, can reproduce the observed flux; C-type shocks under-estimate this line by at least one order of magnitude. A pre-shock density n = 2 × 105 cm-3, and a corresponding shock velocity vs > 10 km s-1, are not consistent with the results of the H2O and CO excitation analysis (Table 2). From the comparison between this pre-shock density and the maximum post-shock density that can be evinced from the [Oi] line ratio (see Sect. 4.3 and Fig. 12), a very small compression factor would be derived. In addition, a comparison with shock models by Hollenbach & McKee (1989) shows that even a lower pre-shock density of 103 cm-3 and shock velocity vs ≳ 30 km s-1 can reproduce our [Oi] data. This suggests that at L1448-B2 the [Oi] emission originates in a fast dissociative shock with pre-shock density n ≲ 2 × 104 cm-3 and vs > 20 km s-1. The presence of a dissociative shock giving rise to ionizing photons is also supported by the detection at the [Oi] peak of OH at 119 μm and [Feii] at 26 μm (see Fig. 2). On the other hand, at the other shock positions we are not able to discriminate between C- and J-type shocks. The observations are consistent either with a low-velocity (vs < 20 km s-1) C-type shock or with a J-type shock with velocity vs > 20 km s-1 for n = 2 × 104 cm-3 and vs > 10 km s-1 for n = 2 × 105 cm-3.

line at 63.2 μm with the shock model predictions. Unsmoothed peak line fluxes have been used to minimize beam dilution effects. At the L1448-B2 position only a J-type shock, with velocity vs > 20 km s-1 for pre-shock density n = 2 × 104 cm-3 and vs > 10 km s-1 for n = 2 × 105 cm-3, can reproduce the observed flux; C-type shocks under-estimate this line by at least one order of magnitude. A pre-shock density n = 2 × 105 cm-3, and a corresponding shock velocity vs > 10 km s-1, are not consistent with the results of the H2O and CO excitation analysis (Table 2). From the comparison between this pre-shock density and the maximum post-shock density that can be evinced from the [Oi] line ratio (see Sect. 4.3 and Fig. 12), a very small compression factor would be derived. In addition, a comparison with shock models by Hollenbach & McKee (1989) shows that even a lower pre-shock density of 103 cm-3 and shock velocity vs ≳ 30 km s-1 can reproduce our [Oi] data. This suggests that at L1448-B2 the [Oi] emission originates in a fast dissociative shock with pre-shock density n ≲ 2 × 104 cm-3 and vs > 20 km s-1. The presence of a dissociative shock giving rise to ionizing photons is also supported by the detection at the [Oi] peak of OH at 119 μm and [Feii] at 26 μm (see Fig. 2). On the other hand, at the other shock positions we are not able to discriminate between C- and J-type shocks. The observations are consistent either with a low-velocity (vs < 20 km s-1) C-type shock or with a J-type shock with velocity vs > 20 km s-1 for n = 2 × 104 cm-3 and vs > 10 km s-1 for n = 2 × 105 cm-3.

|

Fig. 13 Upper panel: comparison between the [Oi] |

Origin of the emission observed with PACS.

A comparison of the observed CO and H2O emission with shock models is presented in the lower panel of Fig. 13 for the L1448-B2 and L1448-R4 shock positions. At the L1448-B2 position the CO and H2O emissions are also consistent with a J-type shock having a pre-shock density n = 2 × 104 cm-3, but at a lower shock velocity (≲20 km s-1) with respect to the [Oi] emission. According to Flower & Pineau Des Forêts (2010), a high compression factor of about 100 is predicted for a low-velocity (vs ≲ 20 km s-1) J-type shock, as observed at this shock position. This corresponds to a post-shock density of about 2 × 106 cm-3, which is within the range of post-shock density derived from the H2O and CO excitation analysis (Table 2) for the hot gas component. Once more, the plot highlights that the physical conditions at this shock position are different with respect to the other selected shock spots. In particular, at the L1448-R4 position the observations are consistent with a C-type shock with pre-shock density n = 2 × 105 cm-3 and velocity larger than 20 km s-1, in contrast with the predictions from C-type shock models for the [Oi] emission at the same shock position. A lower compression factor with respect to L1448-B2, in the range 2.5 − 25, is suggested at L1448-R4 from the comparison between the derived pre-shock densities and the post-shock densities obtained from the excitation analysis. This is consistent with the proposed scenario in which CO and H2O emissions are produced in a C-type shock.

In conclusion (see Table 3 for a summary), our analysis suggests that at the L1448-B2 shock position the H2O and CO emissions are produced in a low-velocity non-dissociative J-type shock along the outflow cavity walls, whereas the [Oi] and maybe the OH emission originate in a fast dissociative shock. The bright and velocity-shifted [Oi] emission at 63 μm, along with the detection of the [Feii] line and the high [Oi]63/145 μm line ratio (~20), supports the presence of fast dissociative shocks related to the presence of an embedded atomic jet near the protostar (e.g. Hollenbach & McKee 1989; Flower & Pineau Des Forêts 2010).

At the other shock positions, we can conclude that the excited H2O and high-J CO emissions are produced in a C-type shock with velocity greater than 20 km s-1, whereas a partially dissociative J-type shock is needed to explain the [Oi] emission. As discussed in Sect. 4.2, the H2O abundance of the hot gas at these positions appears to be higher than at L1448-B2 by a factor of ~4. This is consistent with L1448-B2 being the signpost of a J-type shock, in which the predicted H2O abundance is of the order of 2 × 10-5 (see Flower & Pineau Des Forêts 2010).

Finally, our results are also consistent with previous HIFI observations by Santangelo et al. (2012), showing that the H2O line ratios at L1448-B2 are consistent with a non-dissociative J-type shock, with pre-shock density n = 2 × 104 cm-3. On the other hand, the authors found that in L1448-R4 the shock conditions of the low-velocity component, which dominates the emission in the relatively higher excitation lines, are more degenerate and a C-type shock origin could not be ruled out. The same degeneracy has been inferred for the two positions along the L1157 outflow by Vasta et al. (2012), thus consistent with a possible C-type shock origin for the H2O emission.

We point out, however, that any comparison with available shock models can only be roughly indicative of the real physical situation occurring in the investigated shock events. In particular, geometrical complexity as well as chemical effects induced by diffuse UV fields (both from the star and from associated fast shocks) would need to be properly included in a more realistic model.

6. Conclusions

Herschel-PACS observations of H2O, high-J CO, [Oi], and OH toward two selected positions along the bright outflows L1448 and L1157 have been presented, as part of the WISH key program. The main conclusions of this work are the following:

-

1.

Consistent with other studies, at all selected shock positions wefind a close spatial association, at the angular resolution of ourPACS observations, between H2O emission and high-J CO emission, whereas the low-J CO emission seems to trace a different gas component, not directly associated with shocked gas. A spatial association is also found between H2O emission and mid-IR H2 emission at all selected positions. Moreover, no shift is found at this angular resolution between H2O, [Oi], and [Feii] emission, although the H2O emission appears to be more extended than [Oi] and [Feii].

-

2.

The excitation conditions at the L1448-B2 shock position close to the driving outflow source indicate a two-component model to reproduce the H2O and CO emission. In particular, an extended warm component with temperature T ~ 450 K and density n(H2)= 106 cm-3 is traced by the bulk of the HIFI H2O emission (Eu = 53 − 137 K) and by the PACS CO emission up to J = 22 − 21; furthermore, a compact hot component with T = 1100 K and density n(H2) = (0.5 − 5) × 106 cm-3 is traced by the bulk of the PACS higher-excitation H2O emission (Eu > 190 K) and by the PACS higher-J CO emission. A similar stratification of gas components at different temperatures has been found for the Spitzer H2 gas.

-

3.

Among the selected positions L1448-B2 is found to be peculiar, possibly because of its proximity to the central driving source of the L1448 outflow. In particular, a non-dissociative J-type shock at the point of impact of the jet on the cloud seems to be responsible for the H2O and CO hot gas component at this position, whereas a C-type shock is needed to explain the origin of the hot component at the other selected positions. On the other hand, the observations suggest a dissociative J-type shock at L1448-B2, related to the presence of an embedded atomic jet, to explain the observed OH and [Feii] emission and the bright and velocity-shifted [Oi] emission. A J-type shock that is at least partially dissociative is needed to explain the [Oi] emission at the other selected positions as well.

-

4.

From the comparison between H2O and H2, at L1448-B2 we obtain a H2O abundance of (3−4) × 10-6 for the warm component and of (0.3−1.3) × 10-5 for the hot component. At the other examined shock positions the H2O abundance of the hot component appears to be higher by a factor of ~4, reflecting evolutionary effects on the timescales of the outflow propagation. The indication that the H2O abundance may be higher in the hotter gas in some shock positions is in line with ISO data by other authors (e.g. Giannini et al. 2001). This result is also consistent with L1448-B2 being closer to the driving outflow source than the other selected positions. This makes it more affected by the strong FUV radiation field coming from the nearby protostar that may photodissociate H2O in the post-shock gas and thus decrease the H2O abundance. An estimate of the CO abundance was also derived at L1448-B2 and is of the order of (3−4) × 10-5 for the warm component, whereas it is (1−2) × 10-5 for the hot component.

-

5.

These results, along with the spatial extent inferred for the different gas components, lead us to the conclusion that the two gas components represent a gas stratification in the post-shock region. In particular, the extended and low-abundance warm component traces the post-shocked gas that has already cooled down to a few hundred Kelvin, whereas the compact and possibly more abundant hot component is associated with the gas that is currently undergoing a shock episode, being compressed and heated to a thousand Kelvin. This hot gas component is thus possibly affected by evolutionary effects on the timescales of the outflow propagation, which explains the variations of H2O abundance we observed at the different positions along the outflows.

Online material

Appendix A: PACS maps

The PACS maps of all the lines observed at the four selected shock positions (B2 and R4 along L1448 and B2 and R along L1157) are presented in this section (see also Table 1) . In particular, Figs. A.1 and A.2 are relative to the L1448 outflow (B2 and L1157 positions, respectively), whereas Figs. A.3 and A.4 concern the L1157 outflow (B2 and R positions, respectively).

|

Fig. A.1 PACS spectra of the detected transitions at the L1448-B2 position. The centre of each spaxel box corresponds to its offset position with respect to the coordinates of the central shock position. The velocity (km s-1) and intensity scale (Kelvin) are indicated for one spaxel box and refer to all spectra of the relative transition. The labels in the top-right corner of every box indicate the relative transition. |

|

Fig. A.1 continued. |

|

Fig. A.1 continued. |

|

Fig. A.2 continued. |

|

Fig. A.4 continued. |

The ortho-H2O 312 − 303 line with Eu = 249 K was not detected in B2 (see Santangelo et al. 2012), therefore the H2O line with the highest energy used for the fit was the para-H2O 211 − 202 line with Eu = 137 K.

Acknowledgments

WISH activities at Osservatorio Astronomico di Roma are supported by the ASI project 01/005/11/0. G.S. and B.N. also acknowledge financial contribution from the agreement ASI-INAF I/009/10/0. Astrochemistry in Leiden is supported by NOVA, by a Spinoza grant and grant 614.001.008 from NWO, and by EU FP7 grant 238258. HIFI has been designed and built by a consortium of institutes and university departments from across Europe, Canada and the United States under the leadership of SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research, Groningen, The Netherlands and with major contributions from Germany, France and the US. Consortium members are: Canada: CSA, U.Waterloo; France: CESR, LAB, LERMA, IRAM; Germany: KOSMA, MPIfR, MPS; Ireland, NUI Maynooth; Italy: ASI, IFSI-INAF, Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri- INAF; Netherlands: SRON, TUD; Poland: CAMK, CBK; Spain: Observatorio Astronómico Nacional (IGN), Centro de Astrobiología (CSIC-INTA). Sweden: Chalmers University of Technology - MC2, RSS & GARD; Onsala Space Observatory; Swedish National Space Board, Stockholm University − Stockholm Observatory; Switzerland: ETH Zurich, FHNW; USA: Caltech, JPL, NHSC.

References

- Bachiller, R., & Perez Gutierrez, M. 1997, ApJ, 487, L93 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bachiller, R., Martin-Pintado, J., Tafalla, M., Cernicharo, J., & Lazareff, B. 1990, A&A, 231, 174 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Bachiller, R., Guilloteau, S., Dutrey, A., Planesas, P., & Martin-Pintado, J. 1995, A&A, 299, 857 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Bachiller, R., Pérez Gutiérrez, M., Kumar, M. S. N., & Tafalla, M. 2001, A&A, 372, 899 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Benedettini, M., Viti, S., Giannini, T., et al. 2002, A&A, 395, 657 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Benedettini, M., Busquet, G., Lefloch, B., et al. 2012, A&A, 539, L3 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bergin, E. A., Neufeld, D. A., & Melnick, G. J. 1998, ApJ, 499, 777 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [MathSciNet] [Google Scholar]

- Bjerkeli, P., Liseau, R., Olberg, M., et al. 2009, A&A, 507, 1455 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bjerkeli, P., Liseau, R., Nisini, B., et al. 2011, A&A, 533, A80 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bjerkeli, P., Liseau, R., Larsson, B., et al. 2012, A&A, 546, A29 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Caselli, P., Keto, E., Pagani, L., et al. 2010, A&A, 521, L29 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Ceccarelli, C., Caux, E., White, G. J., et al. 1998, A&A, 331, 372 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Codella, C., Lefloch, B., Ceccarelli, C., et al. 2010, A&A, 518, L112 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Codella, C., Ceccarelli, C., Lefloch, B., et al. 2012a, ApJ, 757, L9 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Codella, C., Ceccarelli, C., Lefloch, B., et al. 2012b, ApJ, 759, L45 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, F., Dubernet, M.-L., Pacaud, F., & Grosjean, A. 2010, A&A, 517, A13 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, F., Dubernet, M.-L., & Grosjean, A. 2011, A&A, 536, A76 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, C. J., & Smith, M. D. 1995, ApJ, 443, L41 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- de Graauw, Th., Helmich, F. P., Phillips, T. G., et al. 2010, A&A, 518, L6 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Dubernet, M.-L., Daniel, F., Grosjean, A., et al. 2006, A&A, 460, 323 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Dubernet, M.-L., Daniel, F., Grosjean, A., & Lin, C. Y. 2009, A&A, 497, 911 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Dutrey, A., Guilloteau, S., & Bachiller, R. 1997, A&A, 325, 758 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Eislöffel, J. 2000, A&A, 354, 236 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Flower, D. R., & Pineau Des Forêts, G. 2010, MNRAS, 406, 1745 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, J., Snell, R. L., Kaufman, M. J., et al. 2008, ApJ, 674, 1015 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fuente, A., Caselli, P., McCoey, C., et al. 2012, A&A, 540, A75 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Giannini, T., Nisini, B., & Lorenzetti, D. 2001, ApJ, 555, 40 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Giannini, T., Nisini, B., Neufeld, D., et al. 2011, ApJ, 738, 80 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Goicoechea, J. R., Cernicharo, J., Karska, A., et al. 2012, A&A, 548, A77 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Gueth, F., Guilloteau, S., & Bachiller, R. 1998, A&A, 333, 287 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Guilloteau, S., Bachiller, R., Fuente, A., & Lucas, R. 1992, A&A, 265, L49 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Herczeg, G. J., Karska, A., Bruderer, S., et al. 2012, A&A, 540, A84 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano, N., Ho, P. P. T., Liu, S.-Y., et al. 2010, ApJ, 717, 58 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota, T., Honma, M., Imai, H., et al. 2011, PASJ, 63, 1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenbach, D., & McKee, C. F. 1989, ApJ, 342, 306 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Karska, A., Herczeg, G. J., van Dishoeck, E. F., et al. 2013, A&A, 552, A141 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, M. J., & Neufeld, D. A. 1996, ApJ, 456, 611 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen, L. E., van Dishoeck, E. F., Tafalla, M., et al. 2011, A&A, 531, L1 [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen, L. E., van Dishoeck, E. F., Bergin, E. A., et al. 2012, A&A, 542, A8 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Lacy, J. H., Knacke, R., Geballe, T. R., & Tokunaga, A. T. 1994, ApJ, 428, L69 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lefloch, B., Cabrit, S., Codella, C., et al. 2010, A&A, 518, L113 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Lefloch, B., Cabrit, S., Busquet, G., et al. 2012, ApJ, 757, L25 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Liseau, R., Ceccarelli, C., Larsson, B., et al. 1996, A&A, 315, L181 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Liseau, R., Justtanont, K., & Tielens, A. G. G. M. 2006, A&A, 446, 561 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Manoj, P., Watson, D. M., Neufeld, D. A., et al. 2013, ApJ, 763, 83 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld, D. A., & Dalgarno, A. 1989, ApJ, 340, 869 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld, D. A., Nisini, B., Giannini, T., et al. 2009, ApJ, 706, 170 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nisini, B., Benedettini, M., Giannini, T., et al. 1999, A&A, 350, 529 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Nisini, B., Benedettini, M., Giannini, T., et al. 2000, A&A, 360, 297 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Nisini, B., Benedettini, M., Codella, C., et al. 2010a, A&A, 518, L120 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Nisini, B., Giannini, T., Neufeld, D. A., et al. 2010b, ApJ, 724, 69 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nisini, B., Santangelo, G., Antoniucci, S., et al. 2013, A&A, 549, A16 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Ott, S. 2010, Astronomical Data Analysis Software and Systems XIX, 434, 139 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Pilbratt, G. L., Riedinger, J. R., Passvogel, T., et al. 2010, A&A, 518, L1 [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Poglitsch, A., Waelkens, C., Geis, N., et al. 2010, A&A, 518, L2 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Fernández, N. J., Tafalla, M., Gueth, F., & Bachiller, R. 2010, A&A, 516, A98 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Santangelo, G., Nisini, B., Giannini, T., et al. 2012, A&A, 538, A45 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Tafalla, M., Liseau, R., Nisini, B., et al. 2013, A&A, 551, A116 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin, J. J., Looney, L. W., Mundy, L. G., Kwon, W., & Hamidouche, M. 2007, ApJ, 659, 1404 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- van der Tak, F. F. S., Black, J. H., Schöier, F. L., Jansen, D. J., & van Dishoeck, E. F. 2007, A&A, 468, 627 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- van Dishoeck, E. F., Kristensen, L. E., Benz, A. O., et al. 2011, PASP, 123, 138 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- van Kempen, T. A., van Dishoeck, E. F., Güsten, R., et al. 2009, A&A, 507, 1425 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- van Kempen, T. A., Kristensen, L. E., Herczeg, G. J., et al. 2010a, A&A, 518, L121 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- van Kempen, T. A., Green, J. D., Evans, N. J., et al. 2010b, A&A, 518, L128 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Vasta, M., Codella, C., Lorenzani, A., et al. 2012, A&A, 537, A98 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Visser, R., Kristensen, L. E., Bruderer, S., et al. 2012, A&A, 537, A55 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, T. L., Muders, D., Dumke, M., Henkel, C., & Kawamura, J. H. 2011, ApJ, 728, 61 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Yıldız, U. A., van Dishoeck, E. F., Kristensen, L. E., et al. 2010, A&A, 521, L40 [Google Scholar]

- Yıldız, U. A., Kristensen, L. E., van Dishoeck, E. F., et al. 2012, A&A, 542, A86 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Yıldız, U. A., Kristensen, L. E., van Dishoeck, E. F., et al. 2013, A&A, 556, A89 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

All Tables

Summary of the best-fit models derived for the two gas components at the L1448-B2 position.

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 PACS H2O 179 μm images of L1448 and L1157 (Nisini et al. 2010a, 2013). The PACS line survey positions are indicated for L1448-B2 and R4 with crosses, for L1157-B2 and R with triangles. The field of view of the PACS observations is displayed as a box at the selected positions. CO(3 − 2) and SiO(3 − 2) emissions for L1448 and L1157, respectively, are superimposed on the H2O maps. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Overlay between PACS H2O 303 − 212 (174 μm), H2O 221 − 110 (108.1 μm), [Oi] |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 Same as in Fig. 2, but for the L1157 outflow. Contours are displayed for IRAM-30 m CO(2 − 1) and SiO(3 − 2) emission (HPBW equal to 11′′ and 18′′, respectively) from Bachiller et al. (2001) and are traced in steps of 5σ, starting from 5σ. Spitzer-IRAC 8 μm emission and Spitzer-IRS H2 S(1) emission at 17 μm from Neufeld et al. (2009) are shown. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4 Upper: rotational diagram at L1448-B2 for the H2 emission lines detected with Spitzer by Giannini et al. (2011). The values have been derived from the H2 fluxes integrated over a 13′′ area for comparison with the PACS data. The black dots are the observed values, whereas the empty dot represents the H2 S(1) line corrected for an ortho-to-para ratio equal to 1 (see Giannini et al. 2011). The green solid line represents the linear fit to the S(0)–S(3) H2 lines, while the green dotted line is the fit obtained using the S(0)–S(2) H2 lines. Finally, the blue line is the linear fit to the S(3)–S(7) lines. The resulting parameters (T,N) or range of parameters of the linear fits are reported in the diagram. Lower: H2 rotational diagram at L1157-R. The symbols are the same as in the upper panel. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5 Top: ratio between H2O 212 − 101 (179 μm) and 303 − 212 (174 μm) emission, as a function of T for two values of H2 density (nH2 = 5 × 105 cm-3 and 5 × 106 cm-3) and two values of H2O column density (NH2O = 3 × 1014 and 4 × 1015 cm-2) of L1448-B2. The shaded band highlights the H2O ratio observed with PACS and the arrows indicate that this ratio can be considered an upper limit (see text for details). Middle and bottom: ratios between H2O 303 − 212 (174 μm) and 313 − 202 (138.5 μm) emission and between H2O 303 − 212 (174 μm) and 404 − 313 (125.4 μm) emission, respectively, as a function of T. The symbols are the same as in the top panel. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 6 Comparison between the observed H2O fluxes (black dots) and the two best-fit models for L1448-B2, which are given in Table 2: the green model is the fit to the HIFI H2O lines and the two blue models are the extremes of the obtained density range that fits the PACS H2O lines (squares represent n(H2) = 5 × 105 cm-3 and circles represent n(H2) = 5 × 106 cm-3). The red model represents the sum of the fluxes predicted for each line by the green and the two blue models. The fluxes predicted by the models have been corrected for the relative predicted filling factors. Calibration uncertainties of 20% for the HIFI data and 30% for the PACS data have been assumed. The open triangle represents the upper limits of the HIFI H2O 312 − 303 line (Eu = 249 K). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 7 H2O rotational diagram at L1448-B2. Calibration uncertainties of 20% for the HIFI data and 30% for the PACS data have been assumed. The predictions of the two best-fit models for L1448-B2, corrected for the relative predicted filling factors, are shown (see Table 2 and Fig. 6). Symbols are as in Fig. 6. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 8 Rotational diagram at L1448-B2 for the CO emission lines (both the detections and the non-detections) observed with PACS (in a 12.′′6 beam) and the JCMT CO(3 − 2) line (empty symbol; beam size equal to 14′′). Calibration uncertainties of 30% have been assumed. The solid line represents the linear fit to the four detected CO lines, the dotted line the linear fit only to the three lower excitation CO lines. As in Fig. 7, the predictions of the two best-fit models for L1448-B2 corrected for the relative predicted filling factors are shown. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 9 Same comparison presented in Fig. 6, but for the CO fluxes measured with PACS toward L1448-B2 (both the detections and the non-detections). The two blue models represent the extremes of the density range derived from the H2O excitation analysis. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 10 Ratio between the H2O 212 − 101 map at 179 μm and the 303 − 212 map at 174 μm for L1448-B2. The ratio is shown only above a 5σ detection level in both maps. The crosses represent the pointing of the 25 spaxels. |

| In the text | |

|