| Issue |

A&A

Volume 642, October 2020

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A55 | |

| Number of page(s) | 28 | |

| Section | Extragalactic astronomy | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202037464 | |

| Published online | 07 October 2020 | |

Deciphering the Lyman α blob 1 with deep MUSE observations⋆,⋆⋆

1

European Southern Observatory, Av. Alonso de Córdova 3107, 763 0355 Vitacura, Santiago, Chile

e-mail: eherenz@eso.org

2

Department of Astronomy, Stockholm University, AlbaNova University Centre, 106 91 Stockholm, Sweden

3

Minnesota Institute for Astrophysics, School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Minnesota, 316 Church Str. SE, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA

Received:

8

January

2020

Accepted:

20

July

2020

Context. Lyman α blobs (LABs) are large-scale radio-quiet Lyman α (Lyα) nebula at high-z that occur predominantly in overdense proto-cluster regions. In particular, there is the prototypical SSA22a-LAB1 at z = 3.1, which has become an observational reference for LABs across the electromagnetic spectrum.

Aims. We want to understand the powering mechanisms that drive the LAB so that we may gain empirical insights into the galaxy-formation processes within a rare dense environment at high-z. Thus, we need to infer the distribution, the dynamics, and the ionisation state of LAB 1’s Lyα emitting gas.

Methods. LAB 1 was observed for 17.2 h with the VLT/MUSE integral-field spectrograph. We produced optimally extracted narrow band images, in Lyαλ1216, He IIλ1640, and we tried to detect C IVλ1549 emission. By utilising a moment-based analysis, we mapped the kinematics and the line profile characteristics of the blob. We also linked the inferences from the line profile analysis to previous results from imaging polarimetry.

Results. We map Lyα emission from the blob down to surface-brightness limits of ≈6 × 10−19 erg s−1 cm−2 arcsec−2. At this depth, we reveal a bridge between LAB 1 and its northern neighbour LAB 8, as well as a shell-like filament towards the south of LAB 1. The complexity and morphology of the Lyα profile vary strongly throughout the blob. Despite the complexity, we find a coherent large-scale east-west velocity gradient of ∼1000 km s−1 that is aligned perpendicular to the major axis of the blob. Moreover, we observe a negative correlation of Lyα polarisation fraction with Lyα line width and a positive correlation with absolute line-of-sight velocity. Finally, we reveal He II emission in three distinct regions within the blob, however, we can only provide upper limits for C IV.

Conclusions. Various gas excitation mechanisms are at play in LAB 1: ionising radiation and feedback effects dominate near the embedded galaxies, while Lyα scattering contributes at larger distances. However, He II/Lyα ratios combined with upper limits on C IV/Lyα are not able to discriminate between active galactic nucleus ionisation and feedback- driven shocks. The alignment of the angular momentum vector parallel to the morphological principal axis appears to be at odds with the predicted norm for high-mass halos, but this most likely reflects that LAB 1 resides at a node of multiple intersecting filaments of the cosmic web. LAB 1 can thus be thought of as a progenitor of a present-day massive elliptical within a galaxy cluster.

Key words: cosmology: observations / galaxies: high-redshift / galaxies: halos / techniques: imaging spectroscopy

The reduced MUSE datacube, the continuum subtracted datacube, and the derived data-products (Lyα narrow-band image, He II narrow-band image, and maps from the moment based analysis) are only available at the CDS via anonymous ftp to cdsarc.u-strasbg.fr (130.79.128.5) or via http://cdsarc.u-strasbg.fr/viz-bin/cat/J/A+A/642/A55

© ESO 2020

1. Introduction

Lyman α (Lyα) blobs (LABs) are very luminous (LLyα ≳ 1043.5 erg s−1) and very extended (≳102 kpc in projection) Lyα emitting nebulae. They were unexpectedly revealed in narrow-band imaging campaigns targeting Lyman α emitting galaxies (LAEs) at z ≳ 3 (Francis et al. 1996; Steidel et al. 2000). LABs have now been found in numerous, sometimes LAB-dedicated, high-z galaxy surveys (e.g. Matsuda et al. 2004; Nilsson et al. 2006; Prescott et al. 2012, 2013). Their presence has been confirmed from z ∼ 1 (Barger et al. 2012) up to z ∼ 7 (Ouchi et al. 2009; Sobral et al. 2015; Shibuya et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2020). Moreover, it has been proposed that a very rare class of extended z ∼ 0.3 [O III] nebulae share similarities with high-redshift LABs (Schirmer et al. 2016).

The distinctive observational feature of LABs with respect to similarly extended and luminous high-z Lyα nebulae around radio galaxies (e.g. Morais et al. 2017; Vernet et al. 2017; Marques-Chaves et al. 2019), radio-loud quasars (e.g. Smith et al. 2009; Roche et al. 2014), or radio-quiet quasars (e.g. Christensen et al. 2006; Borisova et al. 2016; Ginolfi et al. 2018; Husemann et al. 2018; Arrigoni Battaia et al. 2019; Drake et al. 2019; Farina et al. 2019; Travascio et al. 2020) is that the primary powering source driving their Lyα emission is usually not detected or not obvious from the rest-frame UV and rest-frame optical discovery data (see also review by Cantalupo et al. 2017, and references therein). However, the defining physical characteristic of LABs is their preferential occurrence within overdense high-z proto-cluster regions. In fact, the first LABs were found in narrow-band searches targeting known or presumed high-density structures (Francis et al. 1996; Steidel et al. 2000). Following these initial discoveries, other narrow-band surveys targeting redshift overdensities were able to replicate the success in unveiling LABs (e.g. Palunas et al. 2004; Erb et al. 2011; Mawatari et al. 2012; Cai et al. 2017; Kikuta et al. 2019). Conversely, LABs found in blind searches could be linked to over-densities (Prescott et al. 2008; Yang et al. 2009, 2010; Bădescu et al. 2017). Given that their preferred habitats are proto-cluster regions and their sizes are enormous, it appears natural to suspect LABs as the progenitors of extremely massive, if not the most-massive, galaxies in present-day cluster environments (see also review by Overzier 2016).

The required amount of hydrogen ionising photons to drive the observed Lyα output of the blobs via recombinations is  s−1 for a LLyα ≳ 1044 erg s−1 LAB in a standard case-B recombination scenario. This

s−1 for a LLyα ≳ 1044 erg s−1 LAB in a standard case-B recombination scenario. This  would correspond to star-formation rates ≳100 M⊙ yr−1 and absolute UV magnitudes of MUV < −23 using canonical conversion factors (e.g. Kennicutt 1998). The absence of such bright UV galaxies in the vicinity of the nebulae may indicate that the powering sources are heavily dust-obscured along the line of sight. Moreover, it might also hint at an additional source of Lyα photons in LABs: collisional excitations of neutral hydrogen by free electrons, a process which also cools the heated electron gas. As a coolant, Lyα is most effective for gas temperatures around 104 K. In the case of LABs, potential heating sources could be starburst-driven super-winds from the heavily obscured central galaxies (e.g. Taniguchi & Shioya 2000; Mori et al. 2004) or the gravitational potential of the halo hosting the blob (“gravitational cooling”, see e.g. Haiman et al. 2000; Rosdahl & Blaizot 2012).

would correspond to star-formation rates ≳100 M⊙ yr−1 and absolute UV magnitudes of MUV < −23 using canonical conversion factors (e.g. Kennicutt 1998). The absence of such bright UV galaxies in the vicinity of the nebulae may indicate that the powering sources are heavily dust-obscured along the line of sight. Moreover, it might also hint at an additional source of Lyα photons in LABs: collisional excitations of neutral hydrogen by free electrons, a process which also cools the heated electron gas. As a coolant, Lyα is most effective for gas temperatures around 104 K. In the case of LABs, potential heating sources could be starburst-driven super-winds from the heavily obscured central galaxies (e.g. Taniguchi & Shioya 2000; Mori et al. 2004) or the gravitational potential of the halo hosting the blob (“gravitational cooling”, see e.g. Haiman et al. 2000; Rosdahl & Blaizot 2012).

The gravitational cooling mechanism was initially deemed the dominant powering source for driving Lyα emission from LABs (Haiman et al. 2000; Dijkstra & Loeb 2009). This idea is especially intriguing, as theoretical models predict that gas accretion onto galaxies forms dense cold flow filaments (e.g., Kereš et al. 2005; Dekel & Birnboim 2006; Brooks et al. 2009; Stewart et al. 2017). Despite its theoretical importance, empirical evidence for these processes in high-z galaxies remains circumstantial (e.g. Rauch et al. 2016). The filamentary Lyα morphology of LABs as well as the alignment of their major axes with the surrounding large-scale structure are regarded as observational support for the gravitational cooling scenario (Erb et al. 2011; Matsuda et al. 2011).

The polarisation of the observed Lyα emission from the blob could potentially help to distinguish between the central engine hypothesis or the in-situ powering by gravitational cooling (Dijkstra & Loeb 2008; Eide et al. 2018). In the former case, the polarisation fraction is expected to increase with distance from the embedded sources. For Lyman α blob 1, the object examined in detail in this study, this characteristic polarisation was indeed detected (Hayes et al. 2011; Beck et al. 2016). These observations were thought to rule out the gravitational cooling scenario, but Trebitsch et al. (2016) showed that gravitational cooling may also be responsible for the observed polarisation pattern.

In spite of this, follow-up campaigns with X-ray, sub-mm, IR, and radio-facilities revealed that a significant fraction of LABs indeed harbour highly obscured starbursts with star-formation rates of ∼102 − 103 M⊙ yr−1 or, otherwise, an active galactice nucleus (AGN, e.g. Yang et al. 2011; Ao et al. 2015, 2017). Thus, mechanical heating or ionising radiation from these buried systems are definitely contributing and possibly dominating the energy budget that powers Lyα in LABs. In such a scenario, the filamentary morphology can still be reconciled with the cooling flow interpretation, as those flows are expected to fuel star-formation and AGN activity in the first place. But rather than being lit-up in Lyα by gravitational cooling, these filamentary flows could simply be illuminated from the systems that they are feeding (Prescott et al. 2015a). However, a potential counterargument to this scenario is that the gas in the cold flows is self-shielded from ionising radiation given the expected typical densities (nH > 1 cm−3; Dijkstra & Loeb 2009). Moreover, it appears counter-intuitive to assume that the heavily obscured embedded sources have high escape fractions of ionising photons into large-enough solid angles to power the blobs. As yet, there is no consensus on the importance of the possible Lyα powering mechanisms in LABs.

Integral-field spectroscopic (IFS; Bacon & Monnet 2017) observations are an especially promising observational line of attack for such studies. Disentangling the different Lyα powering mechanisms at work in LABs is warranted, as the relevant Lyα emission processes are linked to the physical processes that regulate the build-up of stellar mass and growth of super-massive black holes in the most massive galaxies of the present day universe. The modern integral-field spectrographs on 10 m class telescopes, such as the Keck Cosmic Web Imager (Morrissey et al. 2018) at the Keck II telescope and the Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE, Bacon et al. 2010, 2014) at ESO’s Very Large Telescope UT4, are ideally suited to cover the projected sizes of LABs. Analyses of combined spectral and spatial information from IFS can provide a detailed view of the Lyα morpho-kinematics. Specifically, cold-mode accretion filaments are expected to leave imprints on the velocity fields compared to simple Keplarian motions (Arrigoni Battaia et al. 2018; Martin et al. 2019). Moreover, gas which is not affected by star-formation or AGN driven feedback is expected to be kinematically more quiescent than feedback heated gas. Thus, these processes can potentially be distinguished by spatially mapping the observed Lyα line width.

The difficulty in interpreting line-of-sight velocities and line-widths from Lyα emission is that resonant scattering diffuses the intrinsic Lyα radiation field in real and in the frequency space (see review by Dijkstra 2019). The spatial diffusion can be envisioned as a projected smoothing processes (Bridge et al. 2018) that can enhance the apparent size of the Lyα blobs by reducing the steepness of their surface brightness profiles (Zheng et al. 2011; Gronke & Bird 2017). Moreover, it can also “wash-out” cold-accretion features of small angular size (Smith et al. 2019). The diffusion in frequency space, which is dependent on the kinematics and column densities of the scattering medium, can lead to significant modulations of the spectral profile (e.g. Laursen et al. 2009). Additionally, the transmission of the Lyα photons through the intergalactic medium also modifies the line profile (e.g. Laursen et al. 2011). However, the observed low-velocity shifts between Lyα and optically thin emission lines for galaxies within LABs appear at odds with the expectations from Lyα radiative transfer theory (e.g. McLinden et al. 2013). This might indicate that Lyα scattering does not significantly modulate the observable velocity field of LABs. Thus, it is possible to obtain a measure the angular momentum of the gas in the early formation stage of a massive halo, which directly relates to the action of tidal torques from the surrounding large-scale structure and the cosmic web (e.g. Forero-Romero et al. 2014; Lee et al. 2018).

Further insights into the thermodynamic properties of the emitting gas of z ∼ 3 blobs can be gained from ground-based IFS data due to the potential detectability of other rest-frame UV emission lines. In particular, He IIλ1640 and C IVλ1550 emission lines have been used as diagnostics for LABs (Prescott et al. 2009; Scarlata et al. 2009a; Arrigoni Battaia et al. 2015). Both lines act as gas-coolants, but for a higher temperature (T ≈ 105 K) gas phase compared to Lyα which cools the 104 K phase (Yang et al. 2006). Heating sources driving this phase could be feedback effects from the embedded galaxies (Mori et al. 2004; Cabot et al. 2016) or the gravitational potential of the halo hosting the blob (Yang et al. 2006; Dijkstra & Loeb 2009). Both lines can also be powered via photo-ionisation, but require the abundance of higher energy photons to produce the recombining species. Such hard ionising radiation is only expected in the vicinity of extreme low-metallicity stellar populations (e.g. Schaerer et al. 2013) or in the surroundings of an AGN (e.g. Humphrey et al. 2019). Analysing relative line strengths and comparing the spatial distribution of the He II and C IV emitting gas to the positions of potential ionising sources within blob may help to distinguish between photo-ionisation and cooling-radiation scenarios.

With the aim of deciphering the physical processes at work in LABs, we present the deepest IFS observations of a giant z ∼ 3 LAB obtained so far. Our target is the prototypical giant (Steidel et al. 2000) LAB – SSA-22a Lyman α blob 1 (LAB1). LAB 1 resides in one of the most overdense regions known at z = 3.1. This region, referred to as the SSA 22 proto-cluster, shows a significant density peak of Lyman-break galaxies (Steidel et al. 1998, 2003; Saez et al. 2015), Lyman α emitting galaxies (LAEs, Hayashino et al. 2004; Yamada et al. 2012), sub-mm galaxies (Tamura et al. 2009), AGNs (Lehmer et al. 2009a; Alexander et al. 2016), and also LABs (Matsuda et al. 2004, 2011). Interestingly, with an estimated cluster mass of 2–4 ×1014 M⊙, the SSA 22 proto-cluster may actually be a unique structure within the horizon (Kubo et al. 2015).

Since its discovery, LAB 1 has become the target of numerous follow-up observations and is thus the most well-studied LAB to-date. We provide an overview of those results in Sect. 2, followed by a description of our new 17.2 h MUSE observations in Sect. 3. In Sect. 4, we detail how we reduced the MUSE data. We present our analysis and results in Sect. 5, and in Sect. 6 we discuss the interpretations of our findings. Lastly, we summarise and present our conclusions in Sect. 7.

Throughout the paper, we assume a canonical 737-cosmology, that is, ΩΛ = 0.7, ΩM = 0.3, and H0 = 70 km s−1 Mpc−1. Adopted reference line wavelengths stem from the atomic line list compiled by van Hoof (2018), all wavelengths < 2000 Å refer to vacuum wavelengths. For conversions between air- and vacuum wavelengths, we follow the prescriptions adopted in the Vienna Atomic Line Database (Ryabchikova et al. 2015).

2. Summary of previous results on LAB 1

LAB 1 (RA: 22h17m26.0s, Dec: +00°12′36″) was discovered in a narrow-band image by Steidel et al. (2000). These observations targeted Lyα emission of a previously identified redshift overdensity at z = 3.1 that was revealed as a peak in the redshift distribution of a spectroscopic follow-up campaign for Lyman-break selected galaxies in the SSA-22 field (Steidel et al. 1998). With an isophotal area of 181 arcsec2 (10 523 kpc2 in projection) and a total Lyα luminosity of 8.1 × 1043 erg s−1 LAB 1 is one of the largest and one of most luminous LABs known (Matsuda et al. 2011). Directly north of LAB 1, offset by ≈12″ from its photometric centre, Matsuda et al. (2004) identified a companion blob: LAB 8 (RA: 22h17m26.1s, Dec: +00°12′55″, LLyα = 1.5 × 1043 erg s−1, isophotal area 40 arcsec2). As we demonstrate in the present analysis, LAB 1 and LAB 8 are, in fact, a contiguous structure (see Fig. 1).

|

Fig. 1. Positions of confirmed galaxies within the LAB 1/LAB 8 structure (Table 1) shown alongside Lyα surface brightness contours from our MUSE adaptive narrow band image (see Sect. 5.2). The red circle and red square mark the Lyman Break Galaxies SSA22a-C11 and SSA22a-C15 from Steidel et al. (2003), respectively. The green circle and blue square mark the ALMA 850 μm detections LAB1-ALMA1 and LAB1-ALMA2 (Geach et al. 2016; Umehata et al. 2017), respectively. The red cross marks the position of the 3 GHz radio-continuum detection VLA-LAB1a (Ao et al. 2017). The red diamond indicates the K-band selected and spectroscopically confirmed galaxy LAB01-K15b from Kubo et al. (2015, 2016). The green square marks the ALMA 850 μm plus [C II] 158 μm detected source (Geach et al. 2016; Umehata et al. 2017). This source is also detected at 3 GHz with the VLA (S10 cm = 7.3 μJy; Ao et al. 2017) and it has a tentative X-Ray counterpart in the 400 ks deep Chandra data from Lehmer et al. (2009b). The serendipitously found z = 3.1 [O III] emitter S1 from Geach et al. (2016) is marked with a green triangle. The symbols used to indicate the embedded galaxies within the blob is used throughout the paper. North is to the top and east is to the left. The contours correspond to Lyα surface-brightness levels SBLyα = [200, 100, 50, 25, 8.75] × 10−19 erg s−1 cm−2 arcsec−2. |

Two of the Lyman-break galaxies from Steidel et al. (1998) are within the combined LAB 1/LAB 8 structure. Adopting the nomenclature of Steidel et al. (2003), these are SSA22a-C11 and SSA22a-C15. We list the coordinates of both galaxies in Table 11. SSA22a-C11 is located in the south-west of LAB 1, while SSA22a-C15 is found close to the Lyα photometric centre of LAB 8. Both galaxies have their redshift confirmed via near-IR detections of their [O III] λλ4963, 5007 lines (McLinden et al. 2013). Interestingly, McLinden et al. (2013) find no offset between Lyα emission line redshifts and [O III] redshifts. This is not commonly the case for high-z Lyα emitting galaxies where the Lyα line is typically found to be offset by ≳200 km s−1 with respect to the systemic redshift (e.g. Rakic et al. 2011; Chonis et al. 2013; Trainor et al. 2015). Since positive Lyα redshift offsets are usually interpreted as signs of outflowing expanding gas, McLinden et al. (2013) argue that C11 and C15 have no such prominent outflows. Moreover, C11 has an inferred star-formation rate of ≲10 M⊙ yr−1 (Steidel et al. 1998, 2003); thus this would fall short by more than a factor of ten in terms of producing the required amount of ionising photons to power LAB 1.

Overview of known sources within the Lyα blob.

Given the potential of obscured star-formation or AGN activity in the blob, it naturally became the target of several sub-mm and radio campaigns (Chapman et al. 2001, 2003; Matsuda et al. 2007; Yang et al. 2012; Geach et al. 2014, 2016; Umehata et al. 2017; Ao et al. 2017). Initial studies provided a confusing picture with purported detections by some that were vastly incommensurate with upper limits reached by others (see Sect. 2 of Geach et al. 2014). Nevertheless, advances in sub-mm detector technology and collecting area have led to a significant detection of three 850 μm sources within the blob (Geach et al. 2014, 2016; Umehata et al. 2017). Adopting the nomenclature of Umehata et al. (2017), these ALMA detected systems are denoted LAB1-ALMA1, LAB1-ALMA2, and LAB1-ALMA3. We list their coordinates in Table 1. LAB1-ALMA1 and LAB1-ALMA2 are in close vicinity to each other and close to the peak of Lyα surface brightness. LAB1-ALMA3 is located in the south-eastern part of LAB 1. The total measured 850 μm flux density from these three resolved ALMA sources is S850 μm = 1.7 mJy. This corresponds to star-formation rates of ∼150 M⊙ yr−1 under standard dust-heating assumptions. Moreover, hints for an extended low-surface brightness dust-component which is not detected by ALMA are seen in the fact that the single-dish SCUBA-2 observations (Geach et al. 2014) yield a factor of 2.7 higher flux compared to the interferometric measurement.

Ao et al. (2017) report 3 GHz radio-continuum detection slightly south of LAB 1-ALMA1 and LAB1-ALMA2. This S10 cm = 7.3 ± 2.2 μJy radio source is denoted VLA-LAB1a and we list its coordinates in Table 1. Given the proximity to LAB 1-ALMA1 and LAB1-ALMA2 the radio source is believed to be physically associated with the S850 μm ≈ 1 mJy sub-mm galaxies. According to Ao et al. (2017) the S850 μm/S10 cm ratio is atypical for a purely star-forming system and thus could be indicative of AGN activity. Both systems have no spectroscopic redshift confirmation independent of Lyα. However, sources at the positions of LAB1-ALMA1 and LAB1-ALMA2 are reported as K-Band selected galaxies with photometric redshifts in the range of 2.6 < z < 3.6 (Uchimoto et al. 2012, their Fig. 10).

LAB1-ALMA3 is spectroscopically confirmed as a [C II] 158 μm emitting source with ALMA (I[CII] = 16.8 ± 2.1 Jy km s−1, z[CII] = 3.0993 ± 0.0004; Umehata et al. 2017). It is also detected as a 3 GHz radio-continuum source with the VLA (S10 cm = 7.3 ± 2.2 μJy; Ao et al. 2017). As the coordinates of this radio counterpart are identical to those of LAB1-ALMA3, we do not list it as a separate source. Moreover, Ao et al. (2017) report a tentative X-Ray signal at the position of LAB1-ALMA3 using the deep (400 ks) Chandra full-band (0.5–8 keV) image from Lehmer et al. (2009b). Based on these observations, Ao et al. (2017) suggest the potential existence of an AGN in this source. Moreover, LAB1-ALMA3 appears as a K-Band selected galaxy in the sample of Uchimoto et al. (2012) and has been spectroscopically confirmed via Hβ and [OIII] λ5007 emission with MOIRCS on the Subaru telescope (Kubo et al. 2015, 2016). The redshift derived from those rest-frame optical lines (z = 3.1000 ± 0.004) is commensurate with the [C II]-based redshift.

Two more galaxies have been identified spectroscopically as members of the blob. LAB01-K15b is a K-Band-selected galaxy detected in [O III] emission (Kubo et al. 2015, 2016) and S1 is a serendipitous [O III] detection from Geach et al. (2016). The coordinates and redshifts of both sources were presented by Umehata et al. (2017) and are reproduced in Table 1. Lastly, Kubo et al. (2016) display a faint K-Band selected galaxy slightly south-west of SSA22a-C11 at a compatible photometric redshift (their Fig. 2), however, no coordinates for this potential member of LAB 1 are provided.

In summary, the LAB 1/LAB 8 system contains five spectroscopically confirmed galaxies. Guided by the systemic redshifts of the galaxies associated with the blob (Table 1), we fix z = 3.1 as its systemic redshift in the following. One of the spectroscopically confirmed systems, LAB1-ALMA3, is detected in 850 μm dust-continuum, [C II] 158 μm emission, 3 GHz radio continuum, and tentatively in X-Rays (Ao et al. 2017). Additionally, two 850 μm sources (LAB1-ALMA1 and LAB1-ALMA2) which are accompanied by a 3 GHz sources (VLA-LAB1a) are detected in the centre of LAB 1. While these sources are not spectroscopically confirmed members of the blob, their physical association with the system appears likely, especially given their prominent central position within the blob’s structure. To provide a visual overview of the with the LAB 1/LAB 8 system associated galaxies, we plot their positions with respect to the Lyα surface brightness contours in Fig. 1. For the latter, we make use of the MUSE data discussed in the remainder of the paper.

The interpretation that LAB1-ALMA1 and LAB1-ALMA2 are physically associated with the blob is further supported by results from imaging-polarimetry with FORS2 on the VLT by Hayes et al. (2011). The radial polarisation profile as well as the orientation of the polarisation vectors from those observations are consistent with predictions from Lyα radiative-transfer theory for Lyα scattering from a central Lyα powering source (Dijkstra & Loeb 2008). Interestingly, LAB1-ALMA1 and LAB1-ALMA2 are at the centre of the circular pattern denoted by the polarisation vectors from Hayes et al. (2011). More recent spectro-polarimetry with FORS2 by Beck et al. (2016) appears consistent with this scenario, although the interpretation of spectro-polarimetric Lyα data is more complex (Lee & Ahn 1998), as different scattering geometries and kinematics are degenerate with respect to observable polarisation signal (Eide et al. 2018). Especially, Trebitsch et al. (2016) challenged the interpretation of Hayes et al. (2011) by showing that the observed polarisation signal can be reproduced in a pure cooling-flow scenario. Thus, despite significant observational efforts and numerous counterpart identifications, there is still considerable debate regarding the mechanisms that power the Lyα emission of the blob.

Previous IFS observations of LAB 1 were obtained with the SAURON instrument at the WHT (Bower et al. 2004; Weijmans et al. 2010). These observations revealed a complex morpho-kinematic structure of the system in Lyα. The identification of multiple clump-like features in these data was seen as evidence for the presence of multiple galaxies in the system, while the chaotic motions were interpreted as signs of galaxy-galaxy interactions. Moreover, Weijmans et al. (2010) found signatures of coherent velocity shear at the positions of the Lyman-break galaxies C11 and C15. While these observations provided first insights into the complex kinematic structure of the system, they were limited in depth and spatial resolution. Here, we present the new deep MUSE observations of the system that allow us to map the spatial and kinematic structure of blob in unprecedented detail.

3. ESO VLT/MUSE Observations of LAB 1

LAB 1 was observed with MUSE (Bacon et al. 2010) in its wide field mode configuration without adaptive optics at the European Southern Observatories Unit Telescope 4 (Antu) in three service-mode programmes from 2014 to 2016 (ESO Programme IDs 094.A-0605, 095.A-0570, and 097.A-0831 with principal investigators Hayes, Bower, and Hayes, respectively). A log of these observations is given in Table 2. The individual exposure times are typically 1500 s, only with one exposure being significantly shorter (510 s). In total, the three programmes accumulated a total open-shutter time of 63390 s (17.6 h) on the target.

MUSE observations of LAB 1 present in the ESO archive.

The three different programmes centred the instrument on different regions of the blob. While programmes 094.A-0605 and 095.A-0570 centred the 1′ × 1′ MUSE field of view slightly north of LAB 1 to encompass also the northern neighbouring Lyα blob LAB 8, programme 097.A-0831 centred on a region south-west of the brightest blob structure. This offset was motivated by the detection of a previously unknown low-surface brightness extension of the blob in a reduction of the data from programme 094.A-0605 (see Geach et al. 2016). Each programme used the dithering and rotation pattern that is recommended in the MUSE observing manual2. Unfortunately, one exposure suffered from a severe tracking error and could not be used in the final analysis. Thus the total integration time of the analysable dataset is 17.2 h.

The DIMM seeing reported by ESO for the observation ranges from 0.5″ to 1.7″, but with the majority of exposures taken at sub-arcsecond seeing (mean: 0.87″, median: 0.88″). A potentially more accurate measurement of the seeing is provided by the FHWM measurements of stars in the meteorology fields recorded by MUSE’s slow-guiding system (SGS column of Table 2). Despite having a slightly larger scatter, the measured image quality by the SGS is often a bit better than the site-wide values provided by the DIMM (mean: 0.83″, median: 0.78″),

Programmes 094.A-0605 and 097.A-0831 were taken without the blue cut-off filter in the fore-optics (extended wavelength mode), thus allowing the wavelength range from 465 nm to 930 nm to be sampled (although at the cost of second-order contaminations at λ > 900 nm), while programme 095.A-0570 was taken with the blue cut-off filter within the light path (nominal wavelength mode), thus sampling the wavelength range from 480 nm to 930 nm.

All observational raw data and the associated calibration frames were retrieved from the ESO Science Archive Facility using the raw-data query form3 and the cal-selector tool. For all exposures, the associated calibration frames (bias frames, arc lamp frames, continuum lamp frames, twilight flats, standard star exposures, and astrometric standard fields) were taken as part of the standard calibration plan for MUSE observations. This means, in particular, that twilight flats were taken typically once a week, while standard-star exposures are usually obtained daily. Nevertheless, some retrieved exposures were associated to standard star4 exposure that were taken one night before or after the science observations.

4. Data reduction

4.1. Production of the datacube

For the reduction of the 17.6 h of MUSE observations into a science-ready datacube we used version 2.4.2 of the MUSE Instrument Pipeline (MUSE DRS – Weilbacher et al. 2016) provided by ESO5 and version 3.0 of the MUSE Python Data Analysis Framework (MPDAF – Bacon et al. 2016; Piqueras et al. 2017) provided by the MUSE consortium6. The MUSE DRS version used here incorporates the so-called self-calibration procedure to improve the flat-fielding accuracy for deep datasets (Conseil et al. 2016). For our data reduction, we adopted a similar strategy as the one used for the reduction of the MUSE Hubble Ultra Deep Field (Bacon et al. 2017).

We first ran the MUSE DRS calibration recipes muse_bias, muse_flat, muse_wavecal, and muse_lsf on the calibration frames that are associated to each science and standard star exposure. We also used the muse_twilight recipe on the twilight frames. Next, we applied the resulting calibration data products to each science and standard star exposure using the recipe muse_scibasic. The resulting standard-star pixtables were fed into muse_standard to create response curves, which were then applied to each science exposure with the muse_scipost task, using its self-calibration feature, but without using its sky-subtraction capabilities. When running muse_scipost, we used the associated astrometric calibrations provided from the ESO archive instead of the astrometric calibrations shipped with the pipeline. This approach was necessary, as the instrument underwent several interventions over the long period of observation. Not using the correct astrometric calibrations would result in uncorrected geometric distortions within the pixtables.

In order for self-calibration to work optimally, regions containing sources that are bright in the continuum needed to be masked. While in principle the DRS can automatically detect such regions, we manually masked out bright continuum objects a bit more conservatively compared to the DRS-generated mask. Manual masking was performed by visual inspection of the datacubes with the ds9 software (Joye et al. 2003) using polygon-shaped and circular regions. These regions were then converted into datacube masks using the pyregion python package7. Additionally, four science exposures contained continuum bright linear trails from moving objects (likely satellite flares, meteors or aeroplanes – affected exposures are marked by a † in Table 2). These trails were also masked manually for the self-calibration.

We then removed night sky-emission with muse_create_sky and muse_subtract_sky. During this step, we iteratively masked out regions that contained emission from the Lyα blob, so that the blob’s emission is not subtracted from the final data.

Next, we resampled the individual sky-subtracted and flux-calibrated exposure tables to the final 3D grid with muse_scipost_make_cube. We defined this final grid via an initial run of muse_expcombine on a subset of pointings from each observing programme. Using MPDAF’s combine method, we then produced an unweighted mean stack of those individual datacubes to produce the final science-ready datacube. Prior to this stacking, we masked out bright linear trails that were present in some observations (marked by a † in Table 2). We also ensured that remaining cosmic-ray residuals in the individual datacubes were filtered out in the final stack by using the κ-σ clipping algorithm in the combine task (two maximum iterations with σclip = 5).

The resulting final datacube has 456 × 378 spatial elements (spaxels) that sample the sky parallel to right ascension and declination at 0.2″ × 0.2″. Each spaxel consists of 3802 spectral elements that sample the spectral domain from 4599.6 Å to 9350.8 Å linearly with steps of 1.25 Å.

Throughout the above procedure, a formal variance propagation is also carried out by each of the used routines, thus a second datacube containing the variance for each volume pixel (voxel) is also produced. However, the resampling procedure in muse_scipost_make_cube produces correlated noise between neighbouring voxels (see Fig. 5 in Bacon et al. 2017). Since this co-variance term between neighbouring voxels cannot easily be accounted for in the final reduction, the formal variance cube contains underestimates of the true variances. By processing artificial pixtables filled only with Gaussian noise, Bacon et al. (2017) demonstrated that the variance for a voxel in an individual exposure datacube must be corrected by a factor of (1/0.6)2. Following Bacon et al. (2017), we applied this correction to our final variance cube.

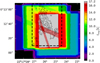

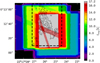

We display a map of the integration time for each spaxel in the MUSE datacube of LAB1 in Fig. 2. The maximum integration time of 61920 s (17.2 h) is reached in a 32″ × 48″ central region of our datacube. In this region, all three ESO observing programmes overlap. This region completely encompassed the known extent of LAB 1 and LAB 8 prior to the observations presented here. Moreover, Fig. 2 also illustrates the location of the masked out regions due to continuum-bright meteor trails or satellite tracks.

|

Fig. 2. Exposure map image for MUSE observations of LAB1 in the SSA22 field. The dashed rectangle indicates the zoomed-in region displayed in the spectral sequence shown in Fig. 3. Diagonal bands of lower exposure times are a result of masked out regions in the final cube stack due to contamination by bright satellite tracks or meteor trails in the individual exposures. To indicate the position and morphology of LAB 1 we also overlay the Lyα surface brightness contours from our MUSE adaptive narrow-band image (see Sect. 5.2). |

Lastly, we produce an emission line only datacube by subtracting a running median filter in spectral direction. This simple method for continuum removal has been proven effective in previous MUSE studies for isolating emission line signals (e.g. Borisova et al. 2016; Herenz & Wisotzki 2017; Herenz et al. 2017a,b; Arrigoni Battaia et al. 2019). Here we set the width of the median filter conservatively to 301 spectral layers (376.25 Å).

4.2. Astrometric alignment

We register the MUSE datacube to an absolute astrometric frame by using the 2MASS point-source catalogue (Skrutskie et al. 2006). Unfortunately, there are only two 2MASS sources within the limited FoV of the MUSE and STIS observations, with one of those sources actually being an extended galaxy. We therefore use the only real 2MASS point source (2MASS J22172397+0012359) to anchor our astrometric reference frame in both observational datasets.

By tying the astrometric reference frame only to one source, there still remain, in principle, several degrees of freedom with respect to geometrical distortions and rotation. However, rotation geometrical distortion are corrected for MUSE data at the pipeline level and the accuracy of this procedure is constantly monitored by ESO using astrometric calibration fields.

We verified our absolute astrometry against an archival HST/STIS 50CCD clear-filter image that is partially overlapping with our MUSE data (Proposal ID: 9174, presented and analysed in Chapman et al. 2001, 2004). We tied the absolute astrometry of this image also to the 2MASS point source. By visual inspection via blinking in ds9, we then ensured that no offsets exist between both datasets. We conservatively estimate that the absolute astrometric accuracy of our data to be on the order of one MUSE pixel (0.2″).

5. Analysis and results

5.1. Velocity sliced Lyα emission maps

We present a spectral sequence of pseudo-narrowband images over the Lyα line in Fig. 3. These images show that we can trace Lyα emission from LAB 1 over a bandwidth of ≈28 Å (±3000 km s−1 around zLy = 3.1). As can be seen from Fig. 3, the highest velocity gas emitting Lyα is located in the vicinity of the central sources LAB1-ALMA1, LAB1-ALMA2, and VLA-LAB1a. However, numerous other features with narrower spectral width appear only in a few velocity slices. Overall, the velocity slices reveal a complex spectral and morphological structure of Lyα emission throughout different parts of the blob. We label notable features in Fig. 3, where we indicate the following. (1) A circular structure devoid of strong Lyα emission towards the north of the sub-mm sources: this feature is labelled as a “bubble” in Fig. 3. It is most clearly seen in the slice around 4979 Å, where we indicate this feature with an arrow. In subsequent redder slices, this “bubble” appears with less contrast. It appears as if its radius increases from ∼20 kpc at 4979 Å to up to ∼40 kpc towards redder wavelengths. (2) A filamentary narrow bridge connecting LAB 1 to LAB 8 in the north: this bridge becomes visible in the slice at 4979 Å and can be clearly followed until the 4989 Å slice. For LAB 8, the flux shears from the north-west to the south-east with increasing wavelength and the filament shows the same velocity shearing. We indicate this by labelling it as “LAB1-8 bridge (blue arm)” and “LAB1-8 bridge (red arm)” of the bridge in the panel displaying the 4979 Å slice and 4989 Å slice, respectively. (3) A compact emission knot towards the north of LAB 8, which connects to LAB 8 via a faint low-surface brightness filament: this feature is seen in the slices at 4981.5 Å and 4984 Å, and we label it “LAE with filament” in the 4984 Å slice. This newly discovered LAE and filament is close to the edge of the field of view of the observations and, thus, only exposed at 8 h–12 h, so the noise in this part of the datacube is significantly larger. Nevertheless, as we discuss in the following Sect. 5.4, the compact emitter and the filament are significant detections. (4) A faint extended, slightly curved, shell-like region towards the south-west of LAB 1: along the major axis, the extent of the shell is ∼120 kpc and its projected thickness is ∼30 kpc. This low-surface brightness emission is visible in the slices from 4976.5 Å to 4981.5 Å, where we label it simply as a “shell”. The shell region appears to be connected to the main area of LAB 1 via a low-surface brightness filament trailing from the north-east to the south-west. The filament is most prominently visible in the 4981.5Å slice, where we label it a “shell connecting filament”. In the northern part of this shell-like region, a compact high-surface brightness knot is visible. This knot is accompanied by another slightly more diffuse knot. These two knots in the northern part of the shell can be traced in the velocity slices from 4974Å to 4981.5Å, and we label both features as “2 knots” in the 4974Å slice. (5) Another compact isolated Lyα line emitter towards the south-east of LAB 1 is seen in the slices from 4984 Å to 4989 Å. We show in the following, namely, in Sect. 5.2, that this emitter is one of four newly detected Lyα emitters in the proximity of the LAB 1/LAB 8. We label this emitter “LAE” in the 4984Å slice.

|

Fig. 3. Spectral sequence of pseudo-narrowband images of LAB 1 from 4971.5 Å to 4999.0 Å created from the continuum subtracted MUSE datacube. Each image has a band-width of 2.5 Å and in order to enhance low-surface brightness features the images have been smoothed with a σ = 1 px (0.2″) Gaussian kernel. In each panel, we indicate the positions of known galaxies within the blob (see Sect. 2 and Fig. 1). Moreover, we show in each panel a scale that indicates 50 kpc in projection at z = 3.1 (6.49″). The morphological features described in Sect. 5.1 are indicated in the bluest image where they become visible. We also indicate that we trace Lyα emission ±3000 km s−1 around the central sources of LAB 1. North is up and east is to the left. |

A closer inspection of the velocity slices reveals that there appears to be an overall velocity shear. The bluer v < 0 km s−1 slices show predominantly emission towards the west, while the redder v > 0 km s−1 slices are dominated by emission from the east. This structure of the velocity shear becomes more clear in our moment-based analysis of the Lyα line profiles (Sect. 5.3).

5.2. Detection and photometric measurements of Lyα emission

5.2.1. Method

To determine the overall Lyα surface-brightness morphology of LAB 1 from our MUSE datacube, it would not be optimal to create a simple narrow-band image by summing over a certain number of datacube layers. Choosing a single bandwidth for such an image would either decrease the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) for regions where the Lyα profiles are very broad if the bandwidth that is chosen too narrow; or, conversely, decrease the S/N in regions where Lyα is narrow if the adopted bandwidth would optimally encompass the broader profiles. Furthermore, such a simple summation would not account for the presence of velocity shear. Thus, we create an adaptive narrow-band image. For this image, we sum only over voxels that contain Lyα flux. Our method is similar to the creation of the narrow-band images in the analysis of extended Lyα emission around QSOs from MUSE data (e.g. Borisova et al. 2016; Arrigoni Battaia et al. 2019).

In order to find the spectral pixels over which we need to sum, we utilised the 3D cross-correlation procedure of the LSDCat software8 (Herenz & Wisotzki 2017). The LSDCat software produces an S/N datacube by cross-correlating the continuum subtracted datacube with a 3D Gaussian template. The parameters of the template are the amount of spatial and spectral dispersion of the 3D Gaussian. Cross-correlation suppresses high-frequency noise while maximising the S/N of signals within the data that match the template. Hence, the method is commonly called “matched filtering” (e.g. Vio & Andreani 2016; Loomis et al. 2018).

LSDCat was originally developed for the detection of Lyα emitting galaxies in blind MUSE surveys (see Herenz et al. 2017b; Urrutia et al. 2019). For this application, the parameters of the template are optimally chosen when they match the width of the seeing point spread function (PSF) and the average line width of LAEs (see Sects. 4.2 and 4.3 in Herenz & Wisotzki 2017). However, our goal here is not to optimise the template for compact emission line sources, but to maximise the detectability of faint low-surface brightness filaments in the outskirts of the blob. Simultaneously, we want to preserve the morphology of small-scale surface-brightness variations. As there is no optimal a priori solution to this problem, the final set of adopted parameters had to be chosen by parameter variation and visual inspection of the resulting images. By experimenting with different spatial filter widths, we found that a spatial full width at half medium (FWHM) of 1.8″ preserved most of the contrast of compact features and significantly enhanced the S/N of the extended filamentary features in the outskirts of the blob. The adopted filter FWHM is roughly twice the seeing PSF FWHM9 of 0.95″. As derived by Zackay & Ofek (2017), a filter width of twice of the seeing FWHM reduces10 the maximum S/N of compact sources only by 20%. Similarly, we varied the FWHM of the spectral part and found that 300 km s−1 is well suited for enhancing the detectability of the blob’s low-surface brightness features.

5.2.2. Maximum S/N image

In Fig. 4, we show the resulting map when taking the maximum S/N in from the LSDCat S/N datacube around zLyα = 3.1. We adopt an S/N threshold of six as a detection threshold to identify reliable regions from which Lyα emission is detectable. These regions are demarcated by a white dashed line in Fig. 4. An S/N threshold of six has previously been proven effective to maximise the ratio of real- to spurious detections in blind emission line searches with MUSE (Herenz & Wisotzki 2017; Herenz et al. 2017b; Urrutia et al. 2019). This is also visualised in Fig. 4, where we include spaxels in the display down to a S/N of four. Inspecting spectra extracted in the 4 < S/N < 6 regions revealed that in all those cases, a possible emission line signature is at most marginal, while the S/N > 6 regions are confident detections.

|

Fig. 4. Map of the maximum signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) after cross-correlating the datacube with a 3D Gaussian template (see Sect. 5.2 for details on the construction of this image). Pixels with S/Nmax < 4 and contaminating foreground sources are masked (regions in black). Thus, pixels shown in colour are a 2D projection of the 3D mask utilised to construct the adaptive narrow band image displayed in Fig. 5. The dashed contour demarcates region of connected pixels with S/Nmax ≥ 6. This highlights that LAB 1, LAB 8 and the newly detected shell comprise a significantly detected contiguous region. The four enumerated features in this image are regions that contain pixels with S/Nmax ≥ 6 that have no pixel connectivity at S/Nmax ≥ 6 with the LAB1/LAB8 + shell structure; these detections are LAEs in the vicinity of the blob and are further discussed in Sect. 5.4. Previously known galaxies at z = 3.1 are indicated using the symbols in Fig. 1 and interesting features are annotated. |

While our goal is to use the S/N datacube from the 3D cross-correlation as a mask to produce an optimally extracted narrow-band image, its 2D representation in the form of maximum S/N map in Fig. 4 provides us with a schematic visualisation of the main morphological features of the system. We annotate these in Fig. 4. Most of the features were already hinted at in the display of the velocity slices in Fig. 3.

Marked S/N peaks are found at the position of the LBG SSA22a-C11 in LAB 1 and near the LBG SSA22a-C15 in LAB 8. We point out that the LAB 8 peak shows a slight offset towards the south of SSA22a-C15. The centre of LAB 1 shows an extended region of high S/N, that exhibits its peak values at LAB1-ALMA2. This area is labelled “central high SB region” in Fig. 4. Interestingly, the sub-mm, [CII] and potentially X-Ray-detected source LAB1-ALMA3 do not have an associated prominent peak in the S/N map, and neither have the spectroscopically confirmed sources S1 and K15b associated peaks. However, these three sources (LAB1-ALMA3, S1, and K15b) demarcate the central high surface-brightness region from the south-east (LAB1-ALMA3, S1) to the north-west (K15b). In the north-west, another high surface-brightness region then curves back to the north-east. This feature is labelled “northern high surface-brightness region” in Fig. 4 and does not contain known sources. It is, however, spatially coincident with the northern edge of the “bubble” that we pointed out in Sect. 5.1 (see Fig. 3).

Our maximum S/N map also accentuates the two filamentary features that form a bridge between LAB 1 and LAB 8. Moreover, the newly detected “shell” region in the south west is clearly connected via a significantly detected filament to the central region of the blob. This shell harbours a compact high-S/N knot, accompanied by more diffuse emission knots towards the north and the south. We also find four isolated S/N > 6 peaks (labelled 1 to 4 in the figure) that are not connected to the central large S/N > 6 region. These isolated S/N > 6 peaks represent newly identified Lyα emitters in close vicinity to the blob and they are analysed separately in Sect. 5.4. With regard to LAE 4 to the north of LAB 8, it appears to be connected by a filamentary structure to the main body of the blob, but this potential filament is detected at lower significance than our adopted detection threshold. The map also hints a potential filament pointing towards LAE 3.

5.2.3. Adaptive narrow-band image

Equipped with the S/N datacube from LSDCat, we constructed the optimal 3D extraction mask for our adaptive narrow-band image. We do so by summing the flux datacube in the spectral direction only over voxels that contain at least an S/N value above four in the S/N datacube. We note that spaxels that do not contain a single voxel with S/N > 4 are blacked out in Fig. 4, thus the displayed spaxels in Fig. 4 can be interpreted as a 2D projection of the 3D extraction mask. The choice of this analysis threshold is motivated by our observation that some S/N > 4 regions in Fig. 4 may contain a marginal Lyα signal. The use of a second S/N threshold that is lower than the detection threshold is also core principle of the LSDCat software, which uses a detection threshold for finding emission lines and an analysis threshold for performing measurements on the detected lines (Herenz & Wisotzki 2017). In order to provide a visual representation of the background noise in source-free regions, we adopt the strategy from Borisova et al. (2016) and sum over four spectral bins. We centre the summation around 4983.4 Å (the wavelength of Lyα at z = 3.1). The adaptive narrow-band image constructed in this way is displayed in Fig. 5. The 1σ noise of the image estimated from placing random apertures in empty sky regions in the central parts of the image is 4 × 10−20 erg s−1 cm−2 arcsec−2.

|

Fig. 5. Adaptive narrow-band image of LAB1. The image is the result of summing only over voxels in the continuum-subtracted datacube that have a S/N > 4 in the LSDCat cross-correlated datacube. For spaxels that do not contain voxels above this threshold we simply sum over 5 Å (four datacube layers) around 4985.6 Å (=(1 + zLAB1) × λLyα). As in Fig. 4, we masked sources where the continuum subtraction with a running median filter failed. In order to further enhance low-SB Lyα features, we smoothed the final image with a σ = 0.2″ Gaussian kernel. The photometric centre and the principal axis of the blob are indicated by a cyan cross and a cyan dashed line, respectively. Previously known galaxies at z = 3.1 are indicated using the same symbols as in Fig. 1. |

The adaptive narrow-band image allows us to characterise the features that were pointed out above (Figs. 3 and 4) by Lyα surface brightness11 (SBLyα). We distinguish three fragments in the shell: (1) A bright compact knot with SBLyα ≈ 5 × 10−18 erg s−1 cm−2 arcsec−2; (2) a fainter, more diffuse knot to the north of the bright knot with SBLyα ≈ 2.8 × 10−18 erg s−1 cm−2 arcsec−2; and (3) an even more diffuse extended fragment in the south of the shell with SBLyα ≈ 1.6 × 10−18 erg s−1 cm−2 arcsec−2. The filament connecting the diffuse part of the shell (labelled as shell-connecting filament in Fig. 5) is characterised by SBLyα ≈ 1 × 10−18 erg s−1 cm−2 arcsec−2 emission, while the central- and northern high-surface brightness regions of LAB 1 show SBLyα ≳ 1 × 10−17 erg s−1 cm−2 arcsec−2. The high-SBLyα regions clearly demarcate a central circular region of lower SBLyα (SBLyα ≈ 5 × 10−18 erg s−1 cm−2 arcsec−2). This apparent cavity, first seen by Bower et al. (2004), was labelled “bubble” in Fig. 3. To the north of LAB 1 we find the two filaments connecting LAB 1 with LAB 8, with the eastern one showing higher SBLyα (SBLyα ≈ 4.5 × 10−18 erg s−1 cm−2 arcsec−2) than the western one (SBLyα ≈ 2.5 × 10−18 erg s−1 cm−2 arcsec−2). LAB 8 is characterised by SBLyα ≳ 1 × 10−17 erg s−1 cm−2 arcsec−2 and for the filament towards LAE 4 in the north, we measure SBLyα ≈ 1 × 10−18 erg s−1 cm−2 arcsec−2. However, in the northern part of the image, due to the lower number of contributing exposures (see Fig. 2), the background noise of the image is higher (σ ≈ 6 × 10−20 erg s−1 cm−2 arcsec−2). With S/Nmax values ∼5−5.5 after the 3D cross-correlation procedure, it misses the adopted detection threshold and we regard this filament conservatively only as a tentative feature.

5.2.4. Size and total Lyα luminosity

We define the size of the unveiled LAB 1 + LAB 8 + shell structure as the area of the region above the adopted detection threshold of S/Nmax = 6 (white contour in Fig. 4), excluding the isolated LAEs. In terms of surface brightness this threshold corresponds to a limit of ≈6 × 10−19 erg s−1 cm−2 arcsec−2. The corresponding limit in surface luminosity is 8.7 × 1038 erg s−1 kpc−2. At this threshold, Lyα emission from the LAB 1/LAB 8 structures covers an area of 553 arcsec2. This corresponds to a projected surface of 3.2 × 104 kpc2 at z = 3.1. The total measured Lyα flux from the structure is FLyα = 1.73 × 10−15 erg s−1 cm−2, which corresponds to a Lyα luminosity of LLyα = 1.45 × 1044 erg s−1.

While the Lyα structure revealed here is enormous, two even larger Lyα nebulae, namely the “Slug” nebulae, with an extent of ≈500 kpc (Cantalupo et al. 2014), and the MAMMOTH-1 nebula, with an extent of ≈440 kpc (Cai et al. 2017), are known. While the “Slug” nebulae surrounds a luminous (Lbol = 1047.3 erg s−1) type-I quasar, the MAMMOTH-1 nebulae surrounds a relatively faint broad-band source whose emission line spectrum appears to be consistent with a quasar. Nevertheless, both the “Slug” and the MAMMOTH-1 nebulae are also characterised by a factor of 3.4 and 1.5 higher luminosity than the LAB 1 + LAB 8 + shell structure, respectively. Both nebulae are at z ≈ 2.3 and, thus, the effect of cosmological surface brightness dimming is reduced by a factor of 2.4 compared to our observations. While no limiting surface brightness for the “Slug” observations has been published, Cai et al. (2017) report a surface brightness detection limit of 4.8 × 10−18 erg s−1 cm−2 arcsec−2 for MAMMOTH-1. This translates to limiting surface luminosity of 6.8 × 1038 erg s−1 kpc−2, which is comparable to our physical limit. The projected maximum extend of our structure, measured from the northernmost tip in LAB 8 to the southernmost point in the shell, is 45.4″ or, correspondingly, 346.3 kpc in projection, which is a factor of ≈0.8 smaller that the extent of the MAMMOTH-1 nebula. Similarly to the LAB 1 – LAB 8 structure, MAMMOTH-1 exists in an extreme overdense region of the universe.

5.2.5. Photometric centre and photometric principal axis

We applied the formalism of image moments (Hu 1962; Stobie et al. 1980; Stobie 1986) to the adaptive narrow-band image to calculate the photometric centre as well as the angle of the principal axis, θPA, of the LAB. In pixel-coordinates (x, y) of the adaptive narrow-band image Ixy the photometric centre  is defined as

is defined as

and the angle of the principal axis is defined as

with

and

For these calculations, we only considered pixels in the narrowband image Ixy that have a corresponding pixel above a S/N of six in the maximum S/N map. Moreover, the definition of the angle of the principal axis in Eq. (2) is such that 0° corresponds to the axis from S to N, and that the angle increases counterclockwise to the east. The photometric centre obtained in this way and converted to celestial coordinates (J2000), is located at RA = 22h17m25.94s, Dec = +00°12′39.338″, and for the angle of the principal axis, we find θPA = 20.9° east of north.

We show the position of the photometric centre in Fig. 5 by a cyan cross. As can be seen, the photometric centre is located slightly west to the “bubble”. We also indicate the principal axis in Fig. 5 by a dashed cyan line. Figuratively speaking, the principal axis is the axis along which the blob appears most elongated. Formally, it describes axis along which the variance in flux is maximised. For a light distribution of elliptical shape, the so defined principal axis would be oriented along the major axis of the ellipse. Thus, our θPA measurement is comparable to the measurements of LAB position angles via ellipse fitting in Erb et al. (2011). We discuss the alignment between principal axis and gas kinematics in Sect. 6.3.1.

5.3. Moment based maps of the Lyα line profile

By visually inspecting the Lyα spectral profile as a function of position with the QFitsView software12 (Davies et al. 2010; Ott 2012), we find that the line profile complexity varies strongly throughout the blob. We illustrate this by showing a selection of representative profiles in Fig. 6. As shown, in some regions, the profiles appear very broad and with a dominating peak (e.g. panel 12 in Fig. 6), while other regions are characterised by clearly double (e.g. panel 3) or even multi-component profiles (e.g. panel 5 or panel 9). The isolated LAEs in the outskirts (example in panel 4, see also Fig. 9) or in the shell-like region (panel 7) show narrower Lyα profiles.

|

Fig. 6. Examples of the variety and complexity of the Lyα line profiles encountered in LAB 1. All profiles are extracted in circular apertures of 1.2″ diameter, except for LAB 8, where a 4″ diameter aperture was used. The image in the centre is the adaptive narrow-band image shown in Fig. 5, but in a logarithmic scale. Green circles represent the extraction apertures with lines connecting to the individual panels that display the profiles. Four of the twelve panels show Lyα profiles at the position of known galaxies: LAB1-ALMA3 in panel 5, SSA22a-C11 in panel 6, LAB1-ALMA1 and LAB1-ALMA2 in panel 9, and SSA22a-C15 (LAB 8) in panel 12. For each profile, the wavelength axis (in Å) is fixed and centred on zLyα = 3.1, but the axis displaying the intensity (in erg s−1 cm−2 Å−1) is scaled to encompass the maximum flux value of each profile. We also indicate in each panel the flux-weighted central moment (Eq. (5), dashed line), and the non-parametric measure for the width of the line obtained from the second flux-weighted moment (from Eq. (6) with k = 2, dotted lines). Moreover, we display in the upper right corner of each panel the non-parametric descriptive measures skewness s (Eq. (10)), kurtosis κ (Eq. (11)), and bi-modality b (Eq. (12)) – see text for details. All non-parametric descriptive statistics are computed by considering only the range of connected positive spectral bins blue- and red-wards of the peak. |

The varying complexity of the Lyα profiles as a function of position prohibit parametric fits of a simple model to the spaxels of the datacube in order to create maps of, for example, the velocity centroid (vr) or line-width (σv). Such an analysis was presented for the much shallower SAURON data of LAB 1 (Bower et al. 2004; Weijmans et al. 2010), but the increased sensitivity and resolution of our MUSE data warrant a different approach. We thus resorted to a moment-based non-parametric analysis. Our method is rooted in descriptive statistics (e.g. Ivezić et al. 2014), but we needed to account for two differences when describing spectroscopic line profiles instead of statistical data with such an ansatz. First, the formal validity of the summarising parameters is only given when positive values are considered in the calculations. Second, the presence of noise and the usage of small sets of input values can lead to non-trivial biases in moment-based quantities, especially if the analysed profiles are of low S/N. To ensure positive values and in order to minimise low-S/N biases we first applied three preprocessing steps to the continuum-subtracted datacube: Firstly, we used the 3D mask that was already used for the creation of the adaptive narrow band image in Sect. 5.2.2. We recall that this 3D mask was constructed by thresholding the matched-filtered datacube with S/N > 4. Voxels that do not fulfil this criterion are set to 0 in the analysis. Secondly, we smoothed each layer of the flux datacube with a circular 2D Gaussian (σ 0.8″). This is done to reduce the spaxel-to-spaxel noise in the final maps, especially in low surface-brightness regions. This value significantly improved the S/N ratio of the Lyα profiles in the filaments and low surface-brightness regions of the blob. Lastly, we used a 2D mask by thresholding the maximum S/N map shown in Fig. 4 to exclude spaxels were only a very small number of spectral bins would contribute to the resulting moments. After visual inspection we set this “display threshold” to S/Nmax = 6, that is, the analysed regions are exactly the regions that we regarded as confident detections in Sect. 5.2.2. After these preparatory steps, we created a 2D array of the central flux-weighted moment (first moment) from the processed datacube voxels Fxyz,

as well as 2D arrays  of the kth flux-weighted moments,

of the kth flux-weighted moments,

for k = 2, k = 3 and k = 4. In Eqs. (5) and (6), as well as in the following equations below, x and y denote the indices of spatial axes of the flux datacube F, while z indexes the spectral direction.

The first moment map resulting from Eq. (5) directly translates into a line-of-sight velocity map

where c is the speed of light,  is the non-linear translation between MUSE spectral pixel coordinate and vacuum wavelength13 and zLAB1 is the systemic redshift of LAB 1. For this translation, we fix the systemic redshift of LAB 1 to zLAB1 = 3.1, which is in agreement with known redshifts of the galaxies within the blob. The so created

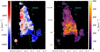

is the non-linear translation between MUSE spectral pixel coordinate and vacuum wavelength13 and zLAB1 is the systemic redshift of LAB 1. For this translation, we fix the systemic redshift of LAB 1 to zLAB1 = 3.1, which is in agreement with known redshifts of the galaxies within the blob. The so created  map is shown in the left panel of Fig. 7. There we also show the photometric centre and the principal axis that were computed from the adaptive narrow band image as described in the previous section. We point out that the principal axis is oriented orthogonal to the direction of the apparent large-scale velocity gradient. This feature is further discussed in Sect. 6.3.

map is shown in the left panel of Fig. 7. There we also show the photometric centre and the principal axis that were computed from the adaptive narrow band image as described in the previous section. We point out that the principal axis is oriented orthogonal to the direction of the apparent large-scale velocity gradient. This feature is further discussed in Sect. 6.3.

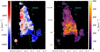

|

Fig. 7. Apparent line-of-sight-velocity (left panel) and apparent velocity dispersion (right panel) as measured from Lyα using the first and second flux weighted moments (Eqs. (7) and (8)). Before the moment-based analysis was carried out, each layer of the datacube was spatially smoothed with a σ = 0.8″ Gaussian kernel. In each spaxel, only spectral bins above a S/N threshold of four in the LSDCat S/N datacube were used in the summations in Eqs. (5) and (6). Moreover, the displayed map shows only spaxels that have a maximum S/N > 6. Thin grey contours indicate surface-brightness levels SBLyα = [200, 100, 50, 25, 8.75] × 10−19 erg s−1 cm−2 arcsec−2 as measured in the adaptive narrow-band image (Fig. 5). The positions of confirmed galaxies within the blob are indicated with the same symbols as in Fig. 1. The photometric centre and the principal axis of the blob (see Sect. 5.2 and Fig. 5) are indicated by a green cross and a green dashed line, respectively. The horizontal cyan line in the upper right of each panel indicates a projected proper distance of 50 kpc. |

By taking the square root of second moment map (Eq. (6), with k = 2) we compute a map that provides a measure of the width of the spectral profiles:

This σv map is shown in the right panel of Fig. 7. We express the width of the profiles σv in km s−1, but caution that this measurement cannot be directly interpreted as velocity dispersion as it is often done for non-resonant emission lines. For example, double- or multiple-peaked profiles generally have larger second moments than single-peaked profiles. Moreover, radiative transfer effects are also known to broaden the single-peaked Lyα line profiles when compared to non-resonant emission lines (see also Sect. 5.5). We thus call the second moment based measure “apparent velocity dispersion”. Lastly, the spectral resolution of MUSE also has an effect on the apparent velocity dispersion. Given the complexity of the profiles and the non-parametric nature of our measurement, the effect of broadening the profiles via convolution with the spectrograph’s line-spread function (LSF) is not easily quantifiable. The measured instrumental width for MUSE at 4980Å is σinst ≈ 75 km s−1 (Bacon et al. 2017). As a figure of merit estimate, this translates into resolution corrections, σcorr, of −34 km s−1, −20 km s−1, −15 km s−1, and −10 km s−1 for apparent velocity dispersions of 100 km s−1, 150 km s−1, 200 km s−1, and 300 km s−1, respectively, if the observed line profiles and the line spread function are well approximated by a Gaussian profile, that is,

Creating such moment-based maps of line-of-sight velocity and apparent velocity dispersion is common in the analysis of synthesised datacubes from radio-interferometric 21 cm observations of galaxies (e.g. Thompson et al. 2017, Section 10.5.4). It now is also routinely used in the analyses of extended Lyα nebulae surrounding quasars (e.g. Borisova et al. 2016; Arrigoni Battaia et al. 2018, 2019; Drake et al. 2019). Moreover, recent theoretical works by Remolina-Gutiérrez & Forero-Romero (2019) and Smith et al. (2019) resort on a moment-based analysis in the analysis of Lyα profiles from Lyα radiative transfer simulations. However, in order to create maps that characterise the varying complexity of the Lyα profile as a function of position in the blob, we use measurements involving higher-moments. Remolina-Gutiérrez & Forero-Romero (2019) suggest using the skewness, s, the kurtosis, κ, and the bimodality, b. These measurements are detailed in the following. To provide a visual guide on how to interpret these quantities, we also display their values next to the example profiles from the blob shown in Fig. 6.

We calculate a map of the Lyα profile skewness s via

The skewness defined in this way (−1 ≤ s ≤ 1) quantifies the asymmetry of the spectral profile with respect to m1. If s ≃ 0 the profile is symmetric around m1 (panel 1 in Fig. 6), while for s > 0 a tail is found redwards of m1 (e.g. panels 4 and 11 in Fig. 6) and for s < 0 a tail is bluewards of m1 (e.g. panels 6, 8, and 10 in Fig. 6). We show our computed map for sxy in the left panel of Fig. 8.

|

Fig. 8. Maps of higher moment-based non-parametric measurements for visualising the varying complexity of the Lyα profiles throughout the blob. We show maps of skewness s (left panel), kurtosis κ (centre panel), and bimodality b (right panel), as defined in Eqs. (10)–(12), respectively (see text for details). The displayed map in the left panel (middle and right panel) shows only spaxels that have a maximum S/N > 6 (maximum S/N > 13). Skewness s quantifies the asymmetry around the first central moment m1 (Eq. (5)), with s = 0 (yellow) indicating symmetric profiles, while s < 0 (shades of blue) indicate that the profile shows a larger tail towards the blue and s > 0 (shades of red) indicate that the profiles show a larger tail towards the red. Kurtosis quantifies the strength of wings (symmetric profiles) or tails (asymmetric profiles), with κ = 3 (white) indicating that the wings of the profile are comparable to a Gaussian wings, while κ > 3 (shades of purple) indicate larger tail extremity of the profiles (shades of brown), and κ < 3 indicate that there is less power in the tails compared to a Gaussian. Bimodality b is an attempt to quantify whether the profiles are double-component (b ≲ 2.6, green colours) or single-component (b ≳ 3, shown in violet) profiles (Remolina-Gutiérrez & Forero-Romero 2019). However, given the presence of noise and finite spectral resolution, a clear discriminatory power between single-component and double-component is not given by this measure in range 2.6 ≲ b ≲ 3 (light green and light violet colours). Contours and symbols are the same as in Fig. 7. |

We note that definitions other than Eq. (10) have been used in the literature to quantify the asymmetric Lyα line-profile morphology of LAEs. For example, Shimasaku et al. (2006) quantified the observed skewness in spectral profiles from Lyman α emitting galaxies by multiplying the definition given in Eq. (10) with a measure of the width of the line; however, we prefer to not entangle those two quantities. Other authors (Mallery et al. 2012; U et al. 2015) have quantified skewness s by fitting a skewed Gaussian profile. Yet this approach does not capture the complex Lyα spectral profiles seen here in LAB 1. Additionally, Childs & Stanway (2018) recently showed that the skewness values derived from fitting an asymmetric Gaussian do not accurately capture the true skewness of Lyα profiles in the presence of finite spectral resolution and background noise. Two other alternative definitions have been put forward by Dawson et al. (2007). These authors quantify asymmetry either via the ratio of flux blue- and redwards of the peak or via the ratio of the widths than encompass 90% of the flux blue- and redwards of the peak. However, given that the profiles in LAB 1 sometimes show multiple peaks at substantial spectral distance (e.g. panels 1 and 3 in Fig. 6), quantifying asymmetry around the higher peak would exaggerate the skew measure compared to the visual perception of symmetry in those profiles.

We obtain a map of the kurtosis of the Lyα profiles via

Kurtosis quantifies how much flux is in the wings of the profiles in comparison to the wings of Gaussian profile (i.e. their tail extremity). For κ = 3, the tails are comparable to the Gaussian profile, while profiles with κ > 3 show more pronounced tails (e.g. panels 6 and 11 in Fig. 6), while κ < 3 indicates the absence of pronounced tails (e.g. panels 1, 5, and 9 in Fig. 6). Of course, only wings that are significantly above the noise can contribute to this statistic. As a corollary, regions of low S/N are biased towards to low kurtosis values. We avoid these biases by increasing the display threshold to S/Nmax = 13. We show the resulting map for κxy in the centre panel of Fig. 8.

Following Remolina-Gutiérrez & Forero-Romero (2019) we calculate a map of the bi-modality of the Lyα line profiles using

Remolina-Gutiérrez & Forero-Romero (2019) introduced this quantity to discriminate whether their Lyα radiative transfer models result in single- or double component profiles. We point out that this measure is not a formal statistical test for bi-modality, but it can capture the visual appearance of the Lyα profile morphologies. We find that for b ≲ 2.6 profiles appear mostly to have clearly distinct double component structures (e.g. panels 1 and 4 in Fig. 6, but also see panel 5 and 9), while profiles with b ≳ 3 appear single peaked (e.g. panel 2, 6, and 7 in Fig. 6). However, some b ≳ 3 profiles may also have a subdominant second component, that is mainly contributing to the kurtosis (e.g. panel 11 in Fig. 6). In the range 2.6 ≲ b ≲ 3, however, the discriminatory power of b appears not strong, and visual inspection of those profiles indicates a high complexity with possible multiple components or peaks (see e.g. panels 3 and 10 in Fig. 6). Despite its potential lack of accuracy, qualitatively b captures the visual complexity of the profiles, with higher values indicating simple single component profiles and lower values indicating more complex profiles, and with the lowest values often corresponding to the presence of double component profiles. Moreover, since the κ is biased towards low values in regions of low S/N, also b is biased low in those regions. Thus, we hide the biased regions by setting the display threshold to S/Nmax = 13. We show our computed map for bxy in the right panel of Fig. 8.

It can be seen that most of the blob shows low values of b indicative of double component Lyα profiles. This impression is also on par with our visual inspection of the line profile variations throughout the blob. Moreover, in the central high surface-brightness region of LAB, where also the broadest profiles are observed, we obtain b values in the intermediate range – these profiles often appear to exhibit a high-degree of complexity. Lastly, only a few small island regions can be characterised by high values of b. These regions show clearly distinct single peaked profiles, often with very pronounced tails. The maps derived and presented here from the moment-based analysis are discussed in Sect. 6.3.

5.4. Newly discovered faint LAEs at z ≈ 3.1 in proximity to LAB 1

As mentioned in Sect. 5.2, our S/N map revealed four detections that are not embedded in the extended Lyα radiation from the blob. We labelled those sources 1 – 4 in Fig. 4. These sources are detected with S/N > 6 in the LSDCat cross-correlated datacube. Formally, one more detection with S/N > 6 at z = 3.1 exists close to the eastern border of Fig. 4, however this detection turned out to be an artefact near the edge of our field of view.

The coordinates, Kron-radii, and fluxes of the newly detected LAEs are listed in Table 3. These measurements have been obtained with the LSDCat software (Herenz & Wisotzki 2017). In Fig. 9, we show the spectral profiles of the detections. These 1D spectra have been extracted within a circular aperture of radius Rkron. No other lines are detected at these positions and thus we are confident that the sources are LAEs in physical proximity to the blob. Additionally, two of the line-profiles (LAE 3 & LAE 4) are reminiscent of the characteristic red-asymmetric line-profiles seen typically in LAEs (e.g. Dawson et al. 2007; Yamada et al. 2012). At z = 3.1 the range of the measured fluxes is log FLyα[erg s−1cm−2] = −17.2…−16.6, which corresponds to Lyα luminosities log LLyα[erg s−1] =41.7…42.3. Hence, those galaxies occupy the faint-end ( ) of the LAE luminosity function (Drake et al. 2017a,b; Herenz et al. 2019) and, thus, they are below the detection limit of classical narrow-band imaging surveys.

) of the LAE luminosity function (Drake et al. 2017a,b; Herenz et al. 2019) and, thus, they are below the detection limit of classical narrow-band imaging surveys.

Newly detected faint z = 3.1 LAEs around LAB1.

|

Fig. 9. Spectral profiles of the newly discovered LAEs 1 – 4 (as labelled in Fig. 4, clockwise from top-left to bottom-right). Spectra (black lines) have been extracted within a circular aperture of radius Rkron (see Table 3). The propagated error spectrum from the variance cube in this aperture is shown as a grey line. The vertical dashed line indicates zLyα = 3.1, whereas the vertical dotted lines indicate the measured redshifts from the profiles (see Table 3). |

From the spectral profiles we measure the LAEs redshifts using the first flux-weighted moment (Eq. (5)). These redshifts are indicated as a vertical dotted lines in Fig. 9. We list the velocity difference Δv with respect to z = 3.1 in Table 3. The two galaxies, 1 and 3, that are south-east of the blob show large positive Δv. In fact, their redshifts appear to be a continuation of the overall west-to-east line-of-sight velocity gradient seen in the blob. For such large values of Δv radiative transfer effects are unlikely the main cause for the redshift offsets. We speculate that the peculiar motion of those galaxies are driven by the gravitation potential of LAB 1’s dark matter halo. The peculiar motion of the compact sources embedded in the northern part of the south-western shell-like structure (labelled as “knots” in Fig. 4) could also be explained by this scenario. Moreover, the small blue-shift of our LAE 4 to the north of LAB 8 appears consistent with a smooth continuation of the overall blob velocity field. However, the base of the blob’s filament which points towards LAE 3 shows blue-shifts and thus deviates from a smooth velocity-field continuation. As we discuss in more detail in Sect. 6, such small-scale modulations of a velocity field could be interpreted as peculiar motions of individual galaxies or filamentary cooling flows. Lastly, the eastern-most galaxy (2) is significantly blue-shifted and does not follow any trend. This galaxy might thus be at a larger distance from LAB 1’s halo and thus not subject to its gravitational potential.