| Issue |

A&A

Volume 682, February 2024

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A102 | |

| Number of page(s) | 15 | |

| Section | Planets and planetary systems | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202346705 | |

| Published online | 08 February 2024 | |

Constraining the reflective properties of WASP-178 b using CHEOPS photometry★,★★

1

INAF, Osservatorio Astrofisico di Catania,

Via S. Sofia 78,

95123

Catania,

Italy

e-mail: isabella.pagano@inaf.it

2

Observatoire Astronomique de l’Université de Genève,

Chemin Pegasi 51,

1290

Versoix,

Switzerland

3

ETH Zurich, Department of Physics,

Wolfgang-Pauli-Strasse 2,

8093

Zurich,

Switzerland

4

Cavendish Laboratory,

JJ Thomson Avenue,

Cambridge

CB3 0HE,

UK

5

Physikalisches Institut, University of Bern,

Gesellschaftsstrasse 6,

3012

Bern,

Switzerland

6

Instituto de Astrofisica e Ciencias do Espaco, Universidade do Porto, CAUP,

Rua das Estrelas,

4150-762

Porto,

Portugal

7

Department of Astronomy, Stockholm University, AlbaNova University Center,

10691

Stockholm,

Sweden

8

Centre for Exoplanet Science, SUPA School of Physics and Astronomy, University of St Andrews,

North Haugh,

St Andrews

KY16 9SS,

UK

9

Aix-Marseille Univ, CNRS, CNES, LAM,

38 rue Frédéric Joliot-Curie,

13388

Marseille,

France

10

Space sciences, Technologies and Astrophysics Research (STAR) Institute, Université de Liège,

Allée du 6 Août 19C,

4000

Liège,

Belgium

11

Center for Space and Habitability, University of Bern,

Gesellschaftsstrasse 6,

3012

Bern,

Switzerland

12

Instituto de Astrofisica de Canarias,

Via Lactea s/n,

38200

La Laguna,

Tenerife,

Spain

13

Departamento de Astrofisica, Universidad de La Laguna,

Astrofísico Francisco Sanchez s/n,

38206

La Laguna,

Tenerife,

Spain

14

Institut de Ciencies de l’Espai (ICE, CSIC),

Campus UAB, Can Magrans s/n,

08193

Bellaterra,

Spain

15

Institut d’Estudis Espacials de Catalunya (IEEC),

Gran Capità 2–4,

08034

Barcelona,

Spain

16

Admatis,

5. Kandó Kálmán Street,

3534

Miskolc,

Hungary

17

Depto. de Astrofisica, Centro de Astrobiologia (CSIC-INTA),

ESAC campus,

28692

Villanueva de la Cañada (Madrid),

Spain

18

Departamento de Fisica e Astronomia, Faculdade de Ciencias, Universidade do Porto,

Rua do Campo Alegre,

4169-007

Porto,

Portugal

19

Space Research Institute, Austrian Academy of Sciences,

Schmiedlstrasse 6,

8042

Graz,

Austria

20

Université Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, IPAG,

38000

Grenoble,

France

21

INAF, Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova,

Vicolo dell’Osservatorio 5,

35122

Padova,

Italy

22

Université de Paris Cité, Institut de physique du globe de Paris, CNRS,

1 rue Jussieu,

75005

Paris,

France

23

ESTEC, European Space Agency,

Keplerlaan 1,

2201AZ

Noordwijk,

The Netherlands

24

Institute of Planetary Research, German Aerospace Center (DLR),

Rutherfordstrasse 2,

12489

Berlin,

Germany

25

INAF, Osservatorio Astrofisico di Torino,

Via Osservatorio, 20,

10025

Pino Torinese To,

Italy

26

Centre for Mathematical Sciences, Lund University,

Box 118,

221 00

Lund,

Sweden

27

Astrobiology Research Unit, Université de Liège,

Allée du 6 Août 19C,

4000

Liège,

Belgium

28

Centre Vie dans l’Univers, Faculté des sciences, Université de Genève,

Quai Ernest-Ansermet 30,

1211

Genève 4,

Switzerland

29

Leiden Observatory, University of Leiden,

PO Box 9513,

2300 RA

Leiden,

The Netherlands

30

Department of Space, Earth and Environment, Chalmers University of Technology,

Onsala Space Observatory,

439 92

Onsala,

Sweden

31

Dipartimento di Fisica, Universita degli Studi di Torino,

via Pietro Giuria 1,

10125,

Torino,

Italy

32

Department of Astrophysics, University of Vienna,

Türkenschanzstrasse 17,

1180

Vienna,

Austria

33

Science and Operations Department – Science Division (SCI-SC), Directorate of Science, European Space Agency (ESA), European Space Research and Technology Centre (ESTEC),

Keplerlaan 1,

2201-AZ

Noordwijk,

The Netherlands

34

Konkoly Observatory, Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences,

1121 Budapest,

Konkoly Thege Miklós

út 15–17,

Hungary

35

ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, Institute of Physics,

Pázmány Péter sétány 1/A,

1117

Budapest,

Hungary

36

German Aerospace Center (DLR), Institute of Optical Sensor Systems,

Rutherfordstraße 2,

12489

Berlin,

Germany

37

IMCCE, UMR8028 CNRS, Observatoire de Paris, PSL Univ., Sorbonne Univ.,

77 av. Denfert-Rochereau,

75014

Paris,

France

38

Institut d’astrophysique de Paris, UMR7095 CNRS, Université Pierre & Marie Curie,

98bis Arago,

75014

Paris,

France

39

Astrophysics Group, Lennard Jones Building, Keele University,

Staffordshire,

ST5 5BG,

UK

40

Institute of Optical Sensor Systems, German Aerospace Center (DLR),

Rutherfordstrasse 2,

12489

Berlin,

Germany

41

Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia “Galileo Galilei”, Universita degli Studi di Padova,

Vicolo dell’Osservatorio 3,

35122

Padova,

Italy

42

Department of Physics, University of Warwick,

Gibbet Hill Road,

Coventry

CV4 7AL,

UK

43

Zentrum für Astronomie und Astrophysik, Technische Universität Berlin,

Hardenbergstr. 36,

10623

Berlin,

Germany

44

Institut fuer Geologische Wissenschaften, Freie Universitaet Berlin,

Maltheserstrasse 74-100,12249

Berlin,

Germany

45

Department of Astrophysics, University of Vienna,

Tuerkenschanzstrasse 17,

1180

Vienna,

Austria

46

Physikalisches Institut, University of Bern,

Sidlerstrasse 5,

3012

Bern,

Switzerland

47

Université de Liège,

Allée du 6 Août 19C,

4000

Liège,

Belgium

48

ELTE Eötvös Loránd University, Gothard Astrophysical Observatory,

9700 Szombathely,

Szent Imre

h. u. 112,

Hungary

49

MTA-ELTE Exoplanet Research Group,

9700 Szombathely,

Szent Imre

h. u. 112,

Hungary

50

Institute of Astronomy, University of Cambridge,

Madingley Road,

Cambridge

CB3 0HA,

UK

51

Institute for Theoretical Physics and Computational Physics, Graz University of Technology,

Petersgasse 16,

8010

Graz,

Austria

Received:

19

April

2023

Accepted:

31

August

2023

Context. Multiwavelength photometry of the secondary eclipses of extrasolar planets is able to disentangle the reflected and thermally emitted light radiated from the planetary dayside. Based on this, we can measure the planetary geometric albedo Ag, which is an indicator of the presence of clouds in the atmosphere, and the recirculation efficiency ϵ, which quantifies the energy transport within the atmosphere.

Aims. We measure Ag and ϵ for the planet WASP-178 b, a highly irradiated giant planet with an estimated equilibrium temperature of 2450 K.

Methods. We analyzed archival spectra and the light curves collected by CHEOPS and TESS to characterize the host WASP-178, refine the ephemeris of the system, and measure the eclipse depth in the passbands of the two telescopes.

Results. We measured a marginally significant eclipse depth of 70 ± 40 ppm in the TESS passband, and a statistically significant depth of 70 ± 20 ppm in the CHEOPS passband.

Conclusions. Combining the eclipse-depth measurement in the CHEOPS (λeff = 6300 Å) and TESS (λeff = 8000 Å) passbands, we constrained the dayside brightness temperature of WASP-178 b in the 2250–2800 K interval. The geometric albedo 0.1< Ag<0.35 generally supports the picture that giant planets are poorly reflective, while the recirculation efficiency ϵ >0.7 makes WASP-178 b an interesting laboratory for testing the current heat-recirculation models.

Key words: planets and satellites: individual: wasp-178 b / techniques: photometric / planets and satellites: detection / planets and satellites: gaseous planets / planets and satellites: atmospheres

The CHEOPS photometric data used in this work are available at the CDS cdsarc.cds.unistra.fr or via https://cdsarc.cds.unistra.fr/viz-bin/cat/J/A+A/682/A102

© The Authors 2024

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. Subscribe to A&A to support open access publication.

1 Introduction

In the past few years, we have gained access to a detailed characterization of exoplanets. Ground-based and space-borne instrumentation have progressed such as to allow the analysis of the atmosphere of exoplanets in terms of thermodynamic state and chemical composition (Sing et al. 2016; Giacobbe et al. 2021). In particular, current photometric facilities allow us to observe the secondary eclipse of giant exoplanets in close orbits (Stevenson et al. 2017; Lendl et al. 2020; Wong et al. 2020; Singh et al. 2022). In this research area, (CHEOPS; Benz et al. 2021) contributes valuable data through its ultra-high photometric accuracy capabilities (Lendl et al. 2020; Deline et al. 2022; Hooton et al. 2022; Brandeker et al. 2022; Parviainen et al. 2022; Scandariato et al. 2022; Demory et al. 2023).

The depth of the eclipse quantifies the brightness of the planetary dayside with respect to its parent star. Depending on the temperature of the planet and on the photometric band used for the observations, the eclipse depth provides insight into the reflectivity and energy redistribution of the atmosphere.

WASP-178 b (HD 134004 b) is a hot Jupiter discovered by Hellier et al. (2019) that was independently announced by Rodríguez Martínez et al. (2020) as KELT-26 b. It orbits an A1 IV–V dwarf star (Table 1) at a distance of 7 stellar radii. These features place WASP-178 b among the planets that receive the highest energy budget from their host stars. It is thus an interesting laboratory for testing atmospheric models in the presence of extreme irradiation.

We analyze the eclipse depths measured using the data collected by the CHaracterising ExOPlanet Satellite (CHEOPS) and the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) space telescopes. The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the data acquisition and reduction, and in Sect. 3, we describe how we derived the stellar radius, mass, and age. In Sect. 4, we update the orbital solution of WASP-178 b, place an upper limit on the eclipse depth using TESS data, and obtain a significant detection using CHEOPS photometry. Finally, in Sect. 5 we discuss the implication of the extracted eclipse signal in terms of geometric albedo and atmospheric recirculation efficiency.

Stellar and system parameters.

2 Observations and data reduction

2.1 TESS observations

TESS (Ricker et al. 2014) observed the WASP-178 system in sector 11 (from 2019 April 23 to 2019 May 20) with a 30-min cadence and in sector 38 (from 2020 April 29 to 2020 May 26) with a 2-min cadence. Rodríguez Martínez et al. (2020) claimed a modulation with period of 0.369526 days in the photometry of sector 11, interpreting it as a δ Scuti pulsation mode. Later, Lothringer et al. (2022) reported that the TESS photometry is heavily contaminated by the background eclipsing binary ASASSN-V J150908.07-424253.6, located at a projected distance of 50.4″ from the target, whose orbital period matches the periodicity in the photometry of WASP-178. In order to optimize the photometric extraction and avoid the variable background contamination, we extracted the light curve (LC) corresponding to each pixel in the aperture mask defined by the TESS pipeline, and we excluded the pixels for which the periodogram shows a peak at the same orbital period as the binary system. We thus reextracted the photometry by retrieving the calibrated full frame imagess (FFIs) and target pixel files (TPFs) for sectors 11 and 38, respectively. We used a custom extraction pipeline combined with the default quality bitmask. The extracted LCs were then corrected for background after we determined the sky level using custom background masks on the FFIs and TPFs. A principal component analysis was then conducted on the pixels in these background masks in all frames in order to measure the flux contribution of scattered light in the TESS cameras. We detrended the data using these principal components as a linear model. Last, we further corrected for any photometric trends due to spacecraft pointing jitter by retrieving the co-trending basis vectorss (CBVs) and 2-s cadence engineering quaternion measurements for the specific cameras with wich WASP-178 was observed. For each sector, we computed the mean of the quaternions over the length of a science observation, that is, 30 min for the FFIs and 2 min for the TPFs. We subsequently used these vectors along with the CBVs to detrend the TESS photometry in a similar manner as in Delrez et al. (2021).

We clipped the photometry taken before BJD 2459334.7 and in the windows 2458610–2458614.5 and 2459346–2459348. These data present artificial trends due to the momentum dumps of the telescope. We also visually identified and excluded a short bump in the LC between BJD 2459337.6 and 2459337.9, most likely an instrumental artifact or some short-term photometric variability feature. The final LCs cover seven and eight transits for sectors 11 and 38, respectively.

2.2 CHEOPS observations

CHEOPS (Benz et al. 2021) observed the WASP-178 system during six secondary eclipses of the planet WASP-178 b with a cadence of 60 s. The aim was to measure the eclipse depth and derive the brightness of the planet in the CHEOPS passband (3500–11000 Å). Each visit was ~12 h long, scheduled in order to bracket the eclipse and equally long pre- and post-eclipse photometry. The logbook of the observations, which are part of the CHEOPS Guaranteed Time Observation (GTO) program, is summarized in Table 2.

The data were reduced using version 13 of the CHEOPS (DRP; Hoyer et al. 2020). This pipeline performs the standard calibration steps (bias, gain, nonlinearity, dark current, and flat fielding) and corrects for environmental effects (cosmic rays, smearing trails from nearby stars, and background) before the photometric extraction.

As for the case of TESS LCs, the aperture photometry is significantly contaminated by ASASSN-V J150908.07-424253. To decontaminate the LC of WASP-178, we performed the photometric extraction using a modified version of the package PIPE1 (Brandeker et al. 2022; Morris et al. 2021; Szabó et al. 2021), upgraded in order to compute the simultaneous point spread function (PSF) photometry of the target and the background contaminant.

The extracted LCs present gaps due to Earth occultations, which cover ~40% of the visits. The exposures close to the gaps are characterized by the high value of the background flux, which is due to straylight from Earth. The corresponding flux measurements are thus affected by stronger photometric scatter.

To avoid these low-quality data, we applied a 5σ clipping to the background measurements. This selection criterion removes less than 20% of the data with the highest background counts. Finally, for a better outlier rejection, we smoothed the data with a Savitzky–Golay filter, computed the residuals with respect to the filtered LC, and performed a 5σ clipping of the outliers. This last rejection criterion excluded a handful of data points in each LC.

Finally, we normalized the unsmoothed LCs by the median value of the photometry. These normalized LCs are publicly available at CDS.

Logbook of the CHEOPS observations of WASP-178.

|

Fig. 1 Out-of-transit and out-of-eclipse 30-min cadence TESS photometry of WASP-178 during sector 11 (left panel) and sector 38 (central panel). In each panel, the dashed vertical lines mark the planetary transit, and the solid blue line is a smoothing of the data points to emphasize the correlated noise. The right panel shows the GLS periodogram of sectors 11 and 38 (top and bottom box, respectively). In each box, we report the bootstrap-computed 0.1% and 1% FAP levels (horizontal dashes) and the planetary orbital period (vertical dotted red line). |

3 Stellar radius, mass, and age

We used a infra-red flux method (IRFM) in a Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) approach to determine the stellar radius of WASP-178 (Blackwell & Shallis 1977; Schanche et al. 2020). We downloaded the broadband fluxes and uncertainties from the most recent data releases for the following bandpasses: Gaia G, GBP, and GRP, 2MASS J, H, and K, and WISE W1 and W2 (Skrutskie et al. 2006; Wright et al. 2010; Gaia Collaboration 2021). Then we matched the observed photometry with synthetic photometry computed in the same band-passes by using the theoretical stellar spectral energy distributions (SEDs) corresponding to stellar atmospheric parameters (Table 1). The fit was performed in a Bayesian framework, and to account for uncertainties in stellar atmospheric modeling, we averaged the ATLAS (Kurucz 1993; Castelli & Kurucz 2003) and PHOENIX (Allard 2014) catalogs to produce weighted-average posterior distributions. This process yielded R★ = 1.722 ± 0.020 R⊙.

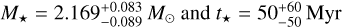

Assuming the Teff, [Fe/H], and R★ listed in Table 1 as input parameters, we also computed the stellar mass M★ and age t★ by using two different sets of stellar evolutionary models. In detail, we employed the isochrone placement algorithm (Bonfanti et al. 2015, 2016) and its capability of interpolating within pre-computed grids of PARSEC2 v1.2S (Marigo et al. 2017) to retrieve a first pair of mass and age estimates. A second pair of mass and age values was computed by the Code Liègeois d’Évolution Stellaire (CLES; Scuflaire et al. 2008), which generates the best-fit evolutionary track of the star by entering the input parameters into the Levenberg-Marquadt minimization scheme as described in Salmon et al. (2021). After carefully checking the mutual consistency of the two pairs of estimates through the χ2 based criterion broadly discussed in Bonfanti et al. (2021), we finally merged the outcome distributions, and we obtained  .

.

4 Light curve analysis

4.1 TESS photometry

To compare the LCs of sectors 11 and 38 in a homogeneous way, we rebinned the photometry of sector 38 to 30 min. The standard deviation of the TESS LCs after transits and secondary eclipses are clipped is ~300ppm for both sectors, and in both cases, the photometric uncertainty can account for only ~70% of the variance. This indicates that there is some noise in the LCs due to astrophysical signals and/or instrumental leftovers. To investigate whether the unexplained variance is related to periodic signals, we computed the generalized Lomb-Scargle (GLS) periodogram (Zechmeister & Kürster 2009) of the out-of-transit and out-of-eclipse photometry (Fig. 1) for both sectors. For sector 11, we found no significant periodic signal, while a strong peak at frequency v = 0.304 ± 0.003 d−1 with a FAP lower than 0.1% is found for sector 38. The amplitude of the corresponding sinusoidal signal is 90 ± 10 ppm.

The periodicity detected in sector 38 is consistent within the uncertainties with the planetary orbital period. Nonetheless, we can exclude that this signal has a planetary origin because it remained undetected in sector 11 and is not coherent from one orbit to the next in sector 38. This signal might be due to stellar rotation, and it is consistent with the typical amplitude reported by Balona (2011) for A-type stars. Its periodicity would correspond to the υ sin i★ in Table 1 if the inclination of the stellar rotation axis were ~15°. This speculation supports the hypothesis of Rodríguez Martínez et al. (2020) that the star is seen nearly pole-on. A significant misalignment between the stellar rotation axis and the planetary orbit axis is expected because of its young age (no time for realignment to occur) and the stellar temperature. Hot stars (Teff > 6200 K) are often observed to be strongly misaligned, which is thought to be due to their lack of a convective zone (Winn et al. 2010), which is needed to tidally align the planetary orbit with the stellar spin axis. Furthermore, Albrecht et al. (2021) found that misaligned orbits are most often polar, or close to polar, as seems to be the case of WASP-178 b. We expand the discussion of the photometric variability and the orientation of the stellar rotation axis in Appendix B.

The fact that the period of the correlated noise is similar to the orbital period of WASP-178 b makes it difficult to extract the complete planetary phase curve (PC) signal. We thus first tried a simpler and more robust approach to analyze the planetary transits and eclipses (Sect. 4.1.1), and then we attempted a more complex analysis framework aimed at retrieving the full PC of WASP-178 b (Sect. 4.1.2).

4.1.1 Fit of transits and eclipses

We computed the ephemeris of the planet by trimming segments of the LCs centered on the transit events (seven transits in sector 11, and eight transits in sector 8) and as wide as three times the transit duration. To further constrain the ephemeris of WASP-178 b, we included the WASP-South photometry (2006 May–2014 August) and EulerCAM I-band photometry (2018 March 26) presented in Hellier et al. (2019) in our analysis. For the WASP-South photometry, we also trimmed the LC around the transits and kept the 24 intervals containing more than 20 data points.

We fit the data using the same Bayesian approach as described in Scandariato et al. (2022). In summary, it consists of the fit of a model in a likelihood-maximization framework, which includes the transits, a linear term for each transit to detrend against stellar or instrumental systematics, and a jitter term to fit the white noise that is not included in the photometric uncertainties. The transit profile was formalized using the quadratic limb-darkening (LD) law indicated by Mandel & Agol (2002) with the reparameterization of the LD coefficients suggested by Kipping (2013). For TESS sector 11, the model was rebinned to the same 30-min cadence of the data. The likelihood maximization was performed with an MCMC using the python emcee package version 3.1.3 (Foreman-Mackey et al. 2013), using a number of samplings that are long enough to ensure convergence. We used flat priors for all the fitting parameters but the stellar density, for which we used the Gaussian prior N(0.43,0.02) given by the stellar mass and radius in Table 1. We also used the Gaussian priors for the LD coefficients given by the LDTk package3. For simplicity, we used the same LD coefficients for the three datasets. This was motivated by the fact that the WASP-South photometry is not accurate enough to constrain the LD profile, and because the TESS passband is basically centered on the standard I band. The same LD profile is therefore expected for the TESS and EulerCAM LCs. Because the model fitting is computationally demanding, we ran the code in the HOTCAT computing infrastructure (Bertocco et al. 2020; Taffoni et al. 2020).

The result of the model fitting is listed in Table 3. The orbital solution we derived is consistent with the solutions of previous studies (Hellier et al. 2019; Rodríguez Martínez et al. 2020) within 5σ. The best-fit model, corresponding to the maximum a posteriori (MAP) parameters, is overplotted on the phase-folded data in Fig. 2, where we rebinned the model and the LC of sector 38 to the same 30-min cadence as for sector 11 (we do not show the WASP-South and EulerCAM photometry for clarity). In Fig. A.1, we show the corner plot of the system parameters from the fit of the transit LCs.

Because the TESS LCs of sectors 11 and 38 show different levels of variability, we investigated any seasonal dependence on the apparent planet-to-star radius ratio. We used the same Bayesian framework as above, where we fixed the ephemeris of WASP-178. The planet-to-star radius ratio we derived is 0.1108 ± 0.0004 for sector 11 and 0.1141 ± 0.0004 for sector 38. The difference is thus 0.0033 ± 0.0006, that is, we found different transit depths with a 5.5cr significance. In particular, we remark that the planet looks larger in sector 38, where the rotation signal is stronger. We thus speculate that WASP-178 was in a low-variability state during sector 11, while 1yr later (~80 stellar rotations), during sector 38, the stellar surface hosted dark spots in corotation with the star. This hypothesis is consistent with that of Hümmerich et al. (2018), according to which magnetic chemically peculiar stars may show complex photometric patterns due to surface inhomogeneities.

We used a similar framework to extract the secondary-eclipse signal of WASP-178. We simultaneously fit segments of the TESS LCs centered on the planetary eclipses, for which we kept the ephemeris of WASP-178 fixed to the values listed in Table 3. We did not attempt the disjoint analysis of the two sectors as the expected eclipse depth is ~ 100 ppm (see below), and the photometric precision of the LCs is not good enough to appreciate differences in the eclipse depth with enough statistical evidence. The only free planetary parameter of the model therefore was the eclipse depth, which is δecl = 70 ± 40 ppm (MAP: 70 ppm). The detrended phase-folded eclipses are shown in Fig. 2 together with the MAP model.

4.1.2 Fit of the phase curve

As a more advanced data analysis, we jointly fit the two TESS sectors to extract the full planetary PC (for a homogeneous analysis, we rebinned sector 38 to the same 30-min cadence as sector 11). The fitting model now included the transits, secondary eclipses, the planetary PC, a Gaussian process (GP) to fit the correlated noise in the data, and for each TESS sector, a long-term linear trend and a jitter term. Given the system parameters listed in Table 1, the expected amplitude of ellipsoidal variations (Morris 1985) and Doppler boosting (Barclay et al. 2012) in the planetary PC are 2.5 ppm and 1 ppm respectively. This is beyond reach for TESS photometry. For the sake of simplicity, we therefore did not include them in the model fitting.

We jointly fit the two TESS sectors, starting with the simplest model where the out-of-transit PC is flat (i.e., we assumed that the planetary PC is not detectable) and the putative stellar rotation was modeled as a GP with the SHO kernel4, indicated for quasi-periodic signals. Checking the residuals of the fit, we realized that some aperiodic correlated noise was left. We thus increased the complexity of the GP model by adding a Matérn 3/2 kernel to capture the remaining correlated noise. This added only two free parameters to the model. This composite GP model ensured better convergence to the fit of the model.

Finally, we also included the planetary PC. When we assume that the planet is basically composed of two homogeneous day-sides and nightsides, the PC is in principle the combination of three components: the PC due to reflected light (with the amplitude Arefl), the PC of the planetary night side (with the amplitude An), and the PC of the planetary dayside, whose amplitude Ad is parameterized such as to be larger than An by an increment δd (this parameterization avoids the nonphysical case of a planetary nightside that is brighter than the dayside). The three terms were modeled assuming Lambert’s cosine law.

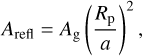

For the reflected PC, the amplitude can be expressed as

(1)

(1)

where Ag is the planetary geometric albedo (Seager 2010). When we assume a Lambertian reflective planetary surface, the geometric albedo is fixed by the Bond albedo AB by  . In the optimistic case of a perfectly reflecting body (AB = 1), the maximum amplitude for the reflected PC is thus Arefl = 167 ± 5 ppm, where we used the system parameters in Table 3.

. In the optimistic case of a perfectly reflecting body (AB = 1), the maximum amplitude for the reflected PC is thus Arefl = 167 ± 5 ppm, where we used the system parameters in Table 3.

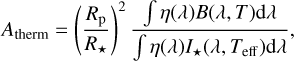

With a slight re-adaptation of the formalism in Seager (2010), the amplitude thermal component Atherm can be expressed as

(2)

(2)

where η(λ) is the optical throughput of the telescope, and I⋆(λ, Teff) is the expected stellar intensity computed with the NextGen model (Hauschildt et al. 1999), corresponding to the effective temperature Teff. We lack infrared information that can constrain the emission spectrum for the planetary thermal emission. We therefore assumed a blackbody spectrum B(λ, T) at a temperature T.

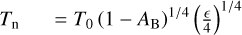

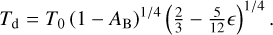

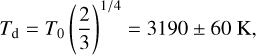

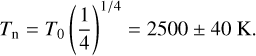

The amplitude of the thermal emission from the day- and nightside depends on the respective temperatures, which we estimated following Cowan & Agol (2011). The expected temperature of the substellar point of WASP-178 b is

(3)

(3)

where we used the stellar effective temperature in Table 1 and the scaled semimajor axis in Table 3.

The nightside temperature Tn and the dayside temperature Td depend on the Bond albedo AB and on the heat-recirculation coefficient ϵ,

(4)

(4)

(5)

(5)

The highest dayside temperature, corresponding to AB = 0 and no heat recirculation (ϵ = 0), is

(6)

(6)

while the maximum nightside temperature, obtained in the case of full energy recirculation (ϵ = 1 ), is

(7)

(7)

These maximum temperatures lead to an upper limit on the dayside (Ad) and nightside (An) thermal emission amplitude of

(8)

(8)

In Fig. 3, we plot the upper limits for the three PCs discussed so far. The figure shows that the three components may reach amplitudes of comparable orders of magnitude, meaning that none of them can in principle be neglected in the extraction of the planetary PC. We note that the two components belonging to the dayside (reflection and thermal emission) have the same shape, thus it is not possible to disentangle them. To simplify the model and avoid the degeneracy between dayside reflection and emission, we thus artificially set Arefl = 0 and let Ad absorb the whole signal belonging to the planetary dayside.

The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC, Burnham & Anderson 2002) favors the model that includes the planetary PCs. The simpler model with flat out-of-transit PC has a relative likelihood of 55% and cannot be rejected. The posterior distributions of the common parameters (system ephemeris and planet-to-star radius ratio) between the two models do not differ significantly.

For both models, the SHO GP has a frequency of v ~ 0.30 day−1, an amplitude of ~70 ppm, and a timescale of ~11 days. The frequency v and the amplitude of the quasi-periodic GP are consistent with the frequency and amplitude of the periodic signal found in the periodogram (Sect. 4.1). While the correspondence between the orbital period of WASP-178 b and the periodicity of the GP suggests that the red noise in the data has planetary origin, we do not have other strong evidence that would support this hypothesis. On the contrary, the planetary origin seems odd for the reasons discussed in Sect. 4.1. The aperiodic red noise fitted as a Matérn 3/2 GP has an amplitude of ~150 ppm and a timescale of ~50 min. Even though the aperiodic red noise evolves on timescales shorter than the transit duration (T14 = 3.53 h), the retrieved posterior distributions of the orbital parameters are similar to those obtained in Sect. 4.1.1.

For the retrieval of the planetary PCs, we derived an upper limit of An < 174 ppm at the 99.9% confidence level, while for the dayside, we derived a 1σ confidence band of 110 ± 40 ppm, which includes both the reflection and thermal emission components. We remark that the Ad parameter in our model corresponds to the eclipse depth δecl and is consistent within the uncertainties with the estimate reported in Table 3.

The fit of the full TESS LC thus confirms the results previously obtained in Sect. 4.1.1. Because of the similarities between the results obtained with the two approaches, we preferred the first approach because it is less prone to interference between the data detrending and the extraction of the orbital parameters and the eclipse depth.

Model parameters for the fit of the TESS WASP-South and EulerCAM data.

|

Fig. 2 Best fit of the transits and eclipses observed by TESS. Left: detrended and phase-folded planetary transits (top panel). The photometry of sectors 11 and 38 is shown with different colors to emphasize the difference in transit depth (the photometry of sectors 11 and 38 is systematically offset upward and downward, respectively, with respect to the best-fit transit profile). The solid blue line is the best-fit model, and the cyan lines represent 100 models corresponding to random samples of the MCMC fit. For the sake of comparison, the photometry of sector 38 and that of the theoretical models are rebinned to the same 30-min cadence as for sector 11. The black dots represent the rebinned photometry. The corresponding O-C diagram is shown in the bottom panel. Right: same as in the left panel, but centered on the eclipse. For clarity, we do not mark the two sectors with different colors. |

|

Fig. 3 Upper limits on the reflected PC, dayside thermal PC, and night-side thermal PC for WASP-178 b. |

4.2 CHEOPS photometry

To analyze the CHEOPS LCs, we used the same approach as for the fit of the eclipses observed by TESS (Sect. 4.1.1), with an additional module in the fitting model that took the systematics in the CHEOPS data into account. The CHEOPS photometry is affected by variable contamination from background stars in the field of view (e.g., Lendl et al. 2020; Deline et al. 2022; Hooton et al. 2022; Wilson et al. 2022; Scandariato et al. 2022). This variability is due to the interplay of the asymmetric PSF with the rotation of the field of view (Benz et al. 2021). By design, PIPE uses nominal magnitudes and coordinates of the stars in the field to fit the stellar PSFs, but residual correlated noise is present in the LCs due to inaccuracies in the assumptions. This signal is phased with the roll angle of the CHEOPS satellite, and in the case of WASP-178, it is clearly visible in the GLS periodogram of the data together with its harmonics. To remove this signal, we included a module in our algorithm that independently fits the harmonic expansions of the orbital period of the telescope and its harmonics for each visit. We found a posteriori that the roll-angle-phased modulation is adequately suppressed (i.e., the periodograms do not peak at the frequencies in the harmonic series) when we include the fundamental harmonic and its first two harmonics in the model.

We also realized that the photometry is significantly correlated with the coordinates of the centroid of the PSF on the detector. To decorrelate against this instrumental jitter, we thus included a bilinear function of the centroid coordinates in the model.

Finally, to take white noise into account that is not included in the formal photometric uncertainties, we added a diagonal GP kernel of the form

(9)

(9)

to our model, with an independent jitter term jv for each CHEOPS visit.

To fit the TESS data (Sect. 4.1.1), we searched the best-fit parameters through likelihood-maximization in an MCMC framework, and we found δecl = 70 ± 20 ppm. The ephemeris of the planet was locked to the MAP values listed in Table 3, which guarantee an uncertainty on the eclipse time smaller than 23 s for each CHEOPS visit. The phase-folded data detrended against stellar and instrumental correlated noise are shown in Fig. 4.

|

Fig. 5 BT-Settl synthetic stellar spectrum for WASP-178 together with the CHEOPS and TESS passbands. |

5 Discussion

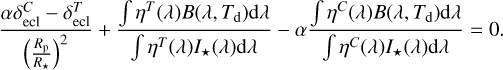

In the previous sections, we have analyzed the TESS and CHEOPS PCs of WASP-178 b in order to extract its planetary eclipse depth δecl. We obtained 70 ± 40 ppm and 70 ± 20 ppm, respectively. These two measurements take both the reflection from the planetary dayside and its thermal emission into account. With the assumptions discussed below, the combined information on the eclipse depth from two different instruments allows us to disentangle these two contributions. For a given telescope with a passband η(λ), we can combine Eqs. (1) and (2) and obtain

(10)

(10)

where Td is the planetary dayside temperature.

Solving for Ag, and indicating the wavelength-dependent quantities with the subscripts C (for CHEOPS) and T (for TESS), we obtain

![$\left\{ {\matrix{ {A_{\rm{g}}^C = {{\left( {{a \over {{R_ \star }}}} \right)}^2}\left[ {{{\delta _{{\rm{ecl}}}^C} \over {{{\left( {{{{R_{\rm{p}}}} \over {{R_ \star }}}} \right)}^2}}} - {{\int {{\eta ^C}} (\lambda )B\left( {\lambda ,{T_{\rm{d}}}} \right)d\lambda } \over {\int {{\eta ^C}} (\lambda ){I_ \star }\left( {\lambda ,{T_{{\rm{eff}}}}} \right)d\lambda }}} \right],} \hfill \cr {A_{\rm{g}}^T = {{\left( {{a \over {{R_ \star }}}} \right)}^2}\left[ {{{\delta _{{\rm{ecl}}}^T} \over {{{\left( {{{{R_{\rm{p}}}} \over {{R_ \star }}}} \right)}^2}}} - {{\int {{\eta ^T}} (\lambda )B\left( {\lambda ,{T_{\rm{d}}}} \right)d\lambda } \over {\int {{\eta ^T}} (\lambda ){I_ \star }\left( {\lambda ,{T_{{\rm{eff}}}}} \right)d\lambda }}} \right].} \hfill \cr } } \right.$](/articles/aa/full_html/2024/02/aa46705-23/aa46705-23-eq15.png) (11)

(11)

In the most general case,  and

and  differ according to the planetary reflection spectrum. Because we lack a spectroscopic analysis of the dayside of WASP-178 b, we defined the proportionality coefficient

differ according to the planetary reflection spectrum. Because we lack a spectroscopic analysis of the dayside of WASP-178 b, we defined the proportionality coefficient  to account for differences between the two passbands. Solving Eq. (11) for Td, we thus obtained the implicit function

to account for differences between the two passbands. Solving Eq. (11) for Td, we thus obtained the implicit function

(12)

(12)

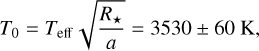

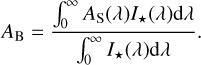

We initially assumed the simplest scenario of a gray albedo spectrum (α = 1) in the spectral range covered by CHEOPS and TESS (the respective bandpasses are shown in Fig. 5). In this scenario, we expect that the contribution of reflection to the eclipse depth is the same in the CHEOPS and TESS passbands. We also expect that the thermal emission from a T ≃ 3000 K blackbody contributes more strongly in the TESS passband because it favors redder wavelengths than CHEOPS (see Fig. 5).

To estimate the dayside temperature Td that best explains our best observations together with their corresponding uncertainty, we randomly extracted 10 000 steps from the Monte Carlo chains obtained in the fit of the transit and eclipse LCs (Sects. 4.1.1 and 4.2). We also generated 10 000 samples of the stellar effective temperature using a normal distribution with mean and standard deviations, as reported in Table 1. For each of the 10000 samples, we thus numerically solved Eq. (12) using the fsolve method of the scipy Python package and obtained 10 000 samples of Td. Then, we plugged all the samples back into Eq. (11) to derive  .

.

The root-finding algorithm failed for ~50% of the samples. These failures correspond to the combination of parameters that prevent Eq. (12) from having a Td root in the domain of real numbers. This happens in particular for the samples where  , which, as discussed above, are not consistent with the gray albedo hypothesis. We thus rejected these samples and show in Fig. 6 the

, which, as discussed above, are not consistent with the gray albedo hypothesis. We thus rejected these samples and show in Fig. 6 the  density map of the remaining samples. Our results indicate

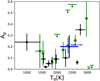

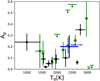

density map of the remaining samples. Our results indicate  and Td = 2400 ± 300 K, consistent with the temperature-pressure profile derived by Lothringer et al. (2022) at pressure higher that 1µ bar by means of ultraviolet transmission spectroscopy. Our result also follows the general trend that Ag increases with Td, as indicated by Wong et al. (2021, Fig. 7).

and Td = 2400 ± 300 K, consistent with the temperature-pressure profile derived by Lothringer et al. (2022) at pressure higher that 1µ bar by means of ultraviolet transmission spectroscopy. Our result also follows the general trend that Ag increases with Td, as indicated by Wong et al. (2021, Fig. 7).

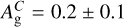

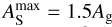

By definition, the geometric albedo Ag refers to the incident light reflected to the star at a given wavelength (or bandpass). Integrating at all angles, the spherical albedo AS is related to Ag by the phase integral q: AS = qAg (see, e.g., Seager 2010). Depending on the scattering law, exoplanetary atmospheres have 1 < q < 1.5 (Pollack et al. 1986; Burrows & Orton 2010). Unfortunately, for the reasons explained in Sect. 4.1.2, we could not extract a robustPC for WASP-178 b, hence we could not place any better constraint on q. In the following, we thus consider the two limiting scenarios  and

and  .

.

The Bond albedo AB is computed as the average of AS weighted over the incident stellar spectrum,

(13)

(13)

The conversion into AB thus relies on the measurement of AS across the stellar spectrum. We only covered the optical and near-infrared part of the spectrum, as shown in Fig. 5, and we lack the necessary information in the ultraviolet, mid-, and far-infrared domains. Following the approach of Schwartz & Cowan (2015), we explored the scenario of a minimum Bond albedo  obtained through Eq. (13) assuming

obtained through Eq. (13) assuming  in the spectral range covered by CHEOPS and TESS and AS = 0 otherwise. The opposite limiting case assumes

in the spectral range covered by CHEOPS and TESS and AS = 0 otherwise. The opposite limiting case assumes  at all wavelengths, which leads to

at all wavelengths, which leads to  . To compute the integrals in Eq. (13), we used the synthetic spectrum in the BT-Settl library that corresponds to the parameters of WASP-178 (Allard et al. 2012).

. To compute the integrals in Eq. (13), we used the synthetic spectrum in the BT-Settl library that corresponds to the parameters of WASP-178 (Allard et al. 2012).

Under the hypothesis that α = 1, we obtained samples of  , which now translate into samples of

, which now translate into samples of  and

and  with the assumptions discussed above. Moreover, inverting Eq. (5) yields

with the assumptions discussed above. Moreover, inverting Eq. (5) yields

![$ = {1 \over 5}\left[ {8 - {{\left( {{{{T_{\rm{d}}}} \over {{T_{{\rm{eff}}}}}}} \right)}^4}{{\left( {{a \over {{R_ \star }}}} \right)}^2}{{12} \over {1 - {A_{\rm{B}}}}}} \right].$](/articles/aa/full_html/2024/02/aa46705-23/aa46705-23-eq35.png) (14)

(14)

Equation (14) indicates that ϵ is a decreasing function of AB. Plugging in the samples of Td, Teff, a/R⋆, and alternatively,  and

and  , we obtained the corresponding samples ϵmax and ϵmin.

, we obtained the corresponding samples ϵmax and ϵmin.

The albedo–recirculation density maps of the two scenarios are shown in the right panel of Fig. 6. As expected, we find that the upper limit on AB is larger (~0.6) in the scenario in which all the factors concur to enhance the reflectivity of the atmosphere (high q and maximum AS), and it decreases to ~0.3 in the opposite scenario of minimum reflectivity.

The recirculation coefficient ϵ tends toward high values, eventually exceeding 1 due to measurement uncertainties in both scenarios. While ϵ > 1 is physically meaningless, the posterior distribution still indicates a high level of atmospheric-energy recirculation in both cases of minimum and maximum albedo (ϵmax = 1.0 ± 0.3 and ϵmin = 0.8 ± 0.3, respectively).

Following different atmospheric models (e.g., Perez-Becker & Showman 2013; Komacek & Showman 2016; Schwartz et al. 2017; Parmentier & Crossfield 2018), WASP-178 b is in a temperature regime in which heat recirculation of zonal winds is suppressed and recirculation efficiency is expected to be low. Nonetheless, Zhang et al. (2018) collected observational evidence that hot Jupiters with irradiation temperatures similar to the temperature of WASP-178 b are characterized by efficient day-to-night recirculation. The global circulation models of Kataria et al. (2016) ascribed this efficiency to the zonal winds, which also explain the eastward offset of the PC of the same planets. While the theoretical predictions on the offset (and correspondingly, the recirculation efficiency) likely overestimate the truth (see Fig. 15 in Zhang et al. 2018), the indication is that zonal winds might indeed explain the energy transfer from the day- to the nightside of WASP-178 b.

Unfortunately, as discussed in Sect. 4.1.2, it is difficult to disentangle the planetary PC and the stellar variability. By consequence, any measurement of the phase-curve offset is precluded. Another possibility is that ionized winds flow from the dayside, where temperatures higher that 2500 K lead to complete dissociation of H2, to the nightside, where lower temperatures allow the molecular recombination and the consequent energy release. This scenario is supported by several recent studies (Bell & Cowan 2018; Tan & Komacek 2019; Mansfield et al. 2020; Helling et al. 2021, 2023).

According to the synthetic models computed by Sudarsky et al. (2000), the albedo spectrum of highly irradiated giant planets is expected to show molecular absorption bands by H2O at about 1 µm and longer wavelength. Because the passband of TESS is more sensitive in the near-infrared than CHEOPS, it is plausible to assume that the geometric albedo in the TESS passband is lower than for CHEOPS. In order to assess how the assumption on α affects our results, we repeated our analysis assuming an extreme α = 0.5. The results are shown in Fig. 8. We find almost the same posterior distribution for dayside temperature, albedo, and recirculation, indicating that the most important source of uncertainty is not the assumptions we make, but the measurement uncertainties on the eclipse depth extracted from the CHEOPS and TESS LCs.

|

Fig. 6

|

|

Fig. 7 Adaptation of Fig. 10 in Wong et al. (2021) including our analysis of WASP-178 b (in blue). The green squares indicate the systems from the first and second year of the TESS primary mission. The black circles indicate the Kepler- and CoRoT-band geometric albedos for the targets that were observed by those missions. |

6 Summary and conclusion

We have analyzed the space-borne photometry of the WASP-178 system obtained with TESS and CHEOPS. For both telescopes, we tailored the photometric extraction in order to avoid strong contamination by a background eclipsing binary. We found evidence that the stellar host rotates with a period of ~3 days, consistent with the orbital period of its hot Jupiter, and that it is seen in a pole-on geometry.

The similarity between the stellar rotation period and the orbital period of the planet, coupled with the quality of the TESS data, does not allow a robust analysis of the full PC of the planet, nor we were we able to place strong constraints on the planetary nightside emission. Nonetheless, focusing on the transit and eclipse events, we were able to update the ephemeris of the planet and measure an eclipse depth of 70 ± 40 ppm and 70 ± 20 ppm in the TESS and CHEOPS passband, respectively.

The joint analysis of the eclipse depth measured in the two passbands allowed us to constrain the temperature in the 2250– 2750 K range, consistent with the temperature-pressure profile derived by Lothringer et al. (2022) at a pressure higher that 1 µbar. Moreover, we were also able to constrain the optical geometric albedo Ag < 0.4, which fits the general increasing albedo with stellar irradiation indicated by Wong et al. (2021).

Finally, we found an indication of an efficient atmospheric heat recirculation of WASP-178 b. If confirmed, this evidence challenges the models that predict a decreasing heat transport by zonal winds as the equilibrium temperature increases (e.g., Perez-Becker & Showman 2013; Komacek & Showman 2016; Schwartz et al. 2017; Parmentier & Crossfield 2018). Conversely, WASP-178 b is an interesting target for testing atmospheric models in which heat transport is granted by ionized winds from the day- to the nightside, where the recombination of H2 takes place (e.g. Mansfield et al. 2020; Helling et al. 2021, 2023). Additional observations of WASP-178 b are needed to better constrain its atmospheric recirculation and rank current competing models. At the time of writing (April 2023), the WASP-178 system is going to be observed again by TESS in sector 65, but this is not expected to add much to the two sectors analyzed in this work. Conversely, dedicated observations from larger space observatories might provide helpful insights of the physical and chemical equilibrium of the atmosphere of WASP-178 b.

Acknowledgements

We thank the referee, N. B. Cowan, for his valuable comments and suggestions. CHEOPS is an ESA mission in partnership with Switzerland with important contributions to the payload and the ground segment from Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. The CHEOPS Consortium would like to gratefully acknowledge the support received by all the agencies, offices, universities, and industries involved. Their flexibility and willingness to explore new approaches were essential to the success of this mission. IPa, GSc, VSi, LBo, GBr, VNa, GPi, and RRa acknowledge support from CHEOPS ASI-INAF agreement no. 2019-29-HH.0. ML acknowledges support of the Swiss National Science Foundation under grant number PCEFP2_194576. This work was also partially supported by a grant from the Simons Foundation (PI Queloz, grant number 327127). S.G.S. acknowledges support from FCT through FCT contract nr. CEECIND/00826/2018 and POPH/FSE (EC). ABr was supported by the SNSA. ACCa and TWi acknowledge support from STFC consolidated grant numbers ST/R000824/1 and ST/V000861/1, and UKSA grant number ST/R003203/1. V.V.G. is an F.R.S-FNRS Research Associate. Y.Al. acknowledges support from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) under grant 200020_192038. We acknowledge support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation and the European Regional Development Fund through grants ESP2016-80435-C2-1-R, ESP2016-80435-C2-2-R, PGC2018-098153-B-C33, PGC2018-098153-B-C31, ESP2017-87676-C5-1-R, MDM-2017-0737 Unidad de Excelencia Maria de Maeztu-Centro de Astrobiología (INTA-CSIC), as well as the support of the Generalitat de Catalunya/CERCA programme. The MOC activities have been supported by the ESA contract No. 4000124370. S.C.C.B. acknowledges support from FCT through FCT contracts nr. IF/01312/2014/CP1215/CT0004. X.B., S.C., D.G., M.F. and J.L. acknowledge their role as ESA-appointed CHEOPS science team members. This project was supported by the CNES. The Belgian participation to CHEOPS has been supported by the Belgian Federal Science Policy Office (BELSPO) in the framework of the PRODEX Program, and by the University of Liège through an ARC grant for Concerted Research Actions financed by the Wallonia-Brussels Federation. L.D. is an F.R.S.-FNRS Postdoctoral Researcher. This work was supported by FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia through national funds and by FEDER through COMPETE2020 – Programa Operacional Competitividade e Internacionalizacão by these grants: UID/FIS/04434/2019, UIDB/04434/2020, UIDP/04434/2020, PTDC/FIS-AST/32113/2017 & POCI-01-0145-FEDER-032113, PTDC/FIS-AST/28953/2017 & POCI-01-0145-FEDER-028953, PTDC/FIS-AST/28987/2017 & POCI-01-0145-FEDER-028987, O.D.S.D. is supported in the form of work contract (DL 57/2016/CP1364/CT0004) funded by national funds through FCT. B.-O.D. acknowledges support from the Swiss State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation (SERI) under contract number MB22.00046. This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research grant agreement no. 724427). It has also been carried out in the frame of the National Centre for Competence in Research PlanetS supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF). D.E. acknowledges financial support from the Swiss National Science Foundation for project 200021_200726 and innovation programme (project FOUR ACES). M.F. and C.M.P. gratefully acknowledge the support of the Swedish National Space Agency (DNR 65/19, 174/18). D.G. gratefully acknowledges financial support from the CRT foundation under Grant No. 2018.2323 “Gaseousor rocky? Unveiling the nature of small worlds”. M.G. is an F.R.S.-FNRS Senior Research Associate. M.N.G. is the ESA CHEOPS Project Scientist and Mission Representative, and as such also responsible for the Guest Observers (GO) Programme. M.N.G. does not relay proprietary information between the GO and Guaranteed Time Observation (GTO) Programmes, and does not decide on the definition and target selection of the GTO Programme. SH gratefully acknowledges CNES funding through the grant 837319. K.G.I. is the ESA CHEOPS Project Scientist and is responsible for the ESA CHEOPS Guest Observers Programme. She does not participate in, or contribute to, the definition of the Guaranteed Time Programme of the CHEOPS mission through which observations described in this paper have been taken, nor to any aspect of target selection for the programme. This work was granted access to the HPC resources of MesoPSL financed by the Region Ile de France and the project Equip@Meso (reference ANR-10-EQPX-29-01) of the programme Investissements d’Avenir supervised by the Agence Nationale pour la Recherche. P.M. acknowledges support from STFC research grant number ST/M001040/1. I.R.I. acknowledges support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation and the European Regional Development Fund through grant PGC2018-098153-B-C33, as well as the support of the Generalitat de Catalunya/CERCA programme. Gy.M.Sz. acknowledges the support of the Hungarian National Research, Development and Innovation Office (NKFIH) grant K-125015, a PRODEX Experiment Agreement No. 4000137122, the Lendület LP2018-7/2021 grant of the Hungarian Academy of Science and the support of the city of Szombathely. N.A.W. acknowledges UKSA grant ST/R004838/1. N.C.S. acknowledges funding by the European Union (ERC, FIERCE, 101052347). Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them. K.W.F.L. was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grants RA714/14-1 within the DFG Schwerpunkt SPP 1992, Exploring the Diversity of Extrasolar Planets. In this work, we use the python package PyDE available at https://github.com/hpparvi/PyDE. This research has made use of the SVO Filter Profile Service (http://svo2.cab.inta-csic.es/theory/fps/) supported from the Spanish MINECO through grant AYA2017-84089.

Appendix A Posterior distributions of the model parameters from the fit of the TESS transit LCs

|

Fig. A.1 Corner plot of the MCMC chains of planetary parameters from the fit of the TESS transits (see Sect. 4.1.1). In each plot, the solid blue lines mark the MAP values. |

Appendix B Analysis of the TESS transits in high cadence

In Sect. 4.1, we analyzed the TESS photometry at low cadence (30 min), and we found a significant difference between the transit depth between sectors 11 and 38. We speculated that the difference in transit depth is due to photospheric variability, which also manifests as a quasi-periodic signal in the LC of sector 38. This hypothesis is supported by the growing evidence that A-type stars show rotational signals that arise from photo-spheric inhomogeneities (e.g., Balona 2011; Böhm et al. 2015; Sikora et al. 2020). This scenario is further supported by the fact that the WASP-178 is classified as an Am star by Hellier et al. (2019).

To test whether the visible hemisphere of the star hosts dark spots, we searched for transit anomalies in the TESS LCs that are localized bumps in the residuals of the transit fits. If present, they indicate that the planetary projection on the stellar surface crosses a darker area compared to the quiescent photosphere (see, e.g., Béky et al. 2014; Scandariato et al. 2017). For this purpose, the low-cadence photometry analyzed in Sect. 4.1 is of little help because a finer time-sampling is needed. We thus compared the high-cadence (2 min) TESS photometry of sector 38 with the best-fit model discussed in Sect. 4.1.2, computed using Rp/R*=0.1141 (see Sect. 4.1.1). This comparison does not show any bump inside the transits (Figs. B.1–B.4), and we conclude that the eight transits observed in sector 38 do not include a spot-crossing event.

We also remark that in contrast with Rodríguez Martínez et al. (2020), we did not detect any systematic asymmetry in the transit profile. The stellar flux distribution along the transit path is symmetric with respect to the transit center. This either indicates that the star does not show any gravity darkening, which is unlikely if the stellar rotation period of ~3.2 days is confirmed, or it supports the hypothesis that the star is in a pole-on geometry, which leads to a radially symmetric flux distribution in the visible stellar hemisphere.

|

Fig. B.1 Detrended short-cadence LC of the first (left panel) and second (right panel) transit observed in TESS sector 38. In each panel, the top plot shows the model computed with the MAP parameters in Table 3 as the solid blue line. The bottom plots show the residuals of the short-cadence photometry with respect to the planetary model shown in the top panel. As a guide, we plot the smoothing of the residuals obtained with a Savitzky-Golay filter as the blue line. In all plots, the vertical dashed lines mark the first and fourth contact. |

|

Fig. B.2 Detrended short-cadence LC of the third (left panel) and fourth (right panel) transit observed in TESS sector 38. The details are the same as in Fig. B.1. |

|

Fig. B.3 Detrended short-cadence LC of the fifth (left panel) and sixth (right panel) transit observed in TESS sector 38. The details are the same as in Fig. B.1. |

|

Fig. B.4 Detrended short-cadence LC of the seventh (left panel) and eighth (right panel) transit observed in TESS sector 38. The details are the same as in Fig. B.1. |

References

- Albrecht, S. H., Marcussen, M. L., Winn, J. N., Dawson, R. I., & Knudstrup, E. 2021, ApJ, 916, L1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Allard, F. 2014, in Exploring the Formation and Evolution of Planetary Systems, 199, IAU Symp., 271 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Allard, F., Homeier, D., & Freytag, B. 2012, Philos. Trans. Roy. Soc. Lond. Ser. A, 370, 2765 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Balona, L. A. 2011, MNRAS, 415, 1691 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay, T., Huber, D., Rowe, J. F., et al. 2012, ApJ, 761, 53 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Béky, B., Holman, M. J., Kipping, D. M., & Noyes, R. W. 2014, ApJ, 788, 1 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bell, T. J., & Cowan, N. B. 2018, ApJ, 857, L20 [Google Scholar]

- Benz, W., Broeg, C., Fortier, A., et al. 2021, Exp. Astron., 51, 109 [Google Scholar]

- Bertocco, S., Goz, D., Tornatore, L., et al. 2020, ASP Conf. Ser., 527, 303 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell, D. E., & Shallis, M. J. 1977, MNRAS, 180, 177 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Böhm, T., Holschneider, M., Lignières, F., et al. 2015, A&A, 577, A64 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfanti, A., Ortolani, S., Piotto, G., & Nascimbeni, V. 2015, A&A, 575, A18 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfanti, A., Ortolani, S., & Nascimbeni, V. 2016, A&A, 585, A5 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfanti, A., Delrez, L., Hooton, M. J., et al. 2021, A&A, 646, A157 [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Brandeker, A., Heng, K., Lendl, M., et al. 2022, A&A, 659, L4 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Burnham, K. P., & Anderson, D. R., eds. 2002, Basic Use of the Information – Theoretic Approach (New York, NY: Springer New York), 98 [Google Scholar]

- Burrows, A., & Orton, G. 2010, in Exoplanets, ed. S. Seager, (Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press), 419 [Google Scholar]

- Castelli, F., & Kurucz, R. L. 2003, in Modelling of Stellar Atmospheres, eds. N. Piskunov, W. W. Weiss, & D. F. Gray, IAU Symposium, 210, A20 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan, N. B., & Agol, E. 2011, ApJ, 729, 54 [Google Scholar]

- Deline, A., Hooton, M. J., Lendl, M., et al. 2022, A&A, 659, A74 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Delrez, L., Ehrenreich, D., Alibert, Y., et al. 2021, Nat. Astron., 5, 775 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Demory, B. O., Sulis, S., Meier Valdés, E., et al. 2023, A&A, 669, A64 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Foreman-Mackey, D. 2018, RNAAS, 2, 31 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Foreman-Mackey, D., Hogg, D. W., Lang, D., & Goodman, J. 2013, PASP, 125, 306 [Google Scholar]

- Foreman-Mackey, D., Agol, E., Ambikasaran, S., & Angus, R. 2017, AJ, 154, 220 [Google Scholar]

- Gaia Collaboration (Brown, A. G. A., et al.) 2021, A&A, 649, A1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Giacobbe, P., Brogi, M., Gandhi, S., et al. 2021, Nature, 592, 205 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hauschildt, P. H., Allard, F., & Baron, E. 1999, ApJ, 512, 377 [Google Scholar]

- Hellier, C., Anderson, D. R., Barkaoui, K., et al. 2019, MNRAS, 490, 1479 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Helling, C., Worters, M., Samra, D., Molaverdikhani, K., & Iro, N. 2021, A&A, 648, A80 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Helling, C., Samra, D., Lewis, D., et al. 2023, A&A, 671, A122 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Hooton, M. J., Hoyer, S., Kitzmann, D., et al. 2022, A&A, 658, A75 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyer, S., Guterman, P., Demangeon, O., et al. 2020, A&A, 635, A24 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Hümmerich, S., Mikulášek, Z., Paunzen, E., et al. 2018, A&A, 619, A98 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Kataria, T., Sing, D. K., Lewis, N. K., et al. 2016, ApJ, 821, 9 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kipping, D. M. 2013, MNRAS, 435, 2152 [Google Scholar]

- Komacek, T. D., & Showman, A. P. 2016, ApJ, 821, 16 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kurucz, R. L. 1993, SYNTHE spectrum synthesis programs and line data (Cambridge, Mass.: Smithsonian) [Google Scholar]

- Lendl, M., Csizmadia, S., Deline, A., et al. 2020, A&A, 643, A94 [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Lothringer, J. D., Sing, D. K., Rustamkulov, Z., et al. 2022, Nature, 604, 49 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel, K., & Agol, E. 2002, ApJ, 580, L171 [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield, M., Bean, J. L., Stevenson, K. B., et al. 2020, ApJ, 888, L15 [Google Scholar]

- Marigo, P., Girardi, L., Bressan, A., et al. 2017, ApJ, 835, 77 [Google Scholar]

- Morris, S. L. 1985, ApJ, 295, 143 [Google Scholar]

- Morris, B. M., Delrez, L., Brandeker, A., et al. 2021, A&A, 653, A173 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Parmentier, V., & Crossfield, I. J. M. 2018, in Handbook of Exoplanets, 116 [Google Scholar]

- Parviainen, H., Wilson, T. G., Lendl, M., et al. 2022, A&A, 668, A93 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Becker, D., & Showman, A. P. 2013, ApJ, 776, 134 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack, J. B., Podolak, M., Bodenheimer, P., & Christofferson, B. 1986, Icarus, 67, 409 [Google Scholar]

- Ricker, G. R., Winn, J. N., Vanderspek, R., et al. 2014, SPIE Conf. Ser., 9143, 914320 [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Martínez, R., Gaudi, B. S., Rodriguez, J. E., et al. 2020, AJ, 160, 111 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon, S. J. A. J., Van Grootel, V., Buldgen, G., Dupret, M. A., & Eggenberger, P. 2021, A&A, 646, A7 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Scandariato, G., Nascimbeni, V., Lanza, A. F., et al. 2017, A&A, 606, A134 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Scandariato, G., Singh, V., Kitzmann, D., et al. 2022, A&A, 668, A17 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Schanche, N., Hébrard, G., Collier Cameron, A., et al. 2020, MNRAS, 499, 428 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, J. C., & Cowan, N. B. 2015, MNRAS, 449, 4192 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, J. C., Kashner, Z., Jovmir, D., & Cowan, N. B. 2017, ApJ, 850, 154 [Google Scholar]

- Scuflaire, R., Théado, S., Montalbán, J., et al. 2008, Ap&SS, 316, 83 [Google Scholar]

- Seager, S. 2010, Exoplanet Atmospheres: Physical Processes (Princeton University Press) [Google Scholar]

- Sikora, J., Wade, G. A., & Rowe, J. 2020, MNRAS, 498, 2456 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sing, D. K., Fortney, J. J., Nikolov, N., et al. 2016, Nature, 529, 59 [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V., Bonomo, A. S., Scandariato, G., et al. 2022, A&A, 658, A132 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Skrutskie, M. F., Cutri, R. M., Stiening, R., et al. 2006, AJ, 131, 1163 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, K. B., Line, M. R., Bean, J. L., et al. 2017, AJ, 153, 68 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sudarsky, D., Burrows, A., & Pinto, P. 2000, ApJ, 538, 885 [Google Scholar]

- Szabó, G. M., Gandolfi, D., Brandeker, A., et al. 2021, A&A, 654, A159 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Taffoni, G., Becciani, U., Garilli, B., et al. 2020, ASP Conf. Ser., 527, 307 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, X., & Komacek, T. D. 2019, ApJ, 886, 26 [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, T. G., Goffo, E., Alibert, Y., et al. 2022, MNRAS, 511, 1043 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Winn, J. N., Fabrycky, D., Albrecht, S., & Johnson, J. A. 2010, ApJ, 718, L145 [Google Scholar]

- Wong, I., Benneke, B., Shporer, A., et al. 2020, AJ, 159, 104 [Google Scholar]

- Wong, I., Kitzmann, D., Shporer, A., et al. 2021, AJ, 162, 127 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wright, E. L., Eisenhardt, P. R. M., Mainzer, A. K., et al. 2010, AJ, 140, 1868 [Google Scholar]

- Zechmeister, M., & Kürster, M. 2009, A&A, 496, 577 [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M., Knutson, H. A., Kataria, T., et al. 2018, AJ, 155, 83 [Google Scholar]

PAdova and TRieste Stellar Evolutionary Code: http://stev. oapd.inaf.it/cgi-bin/cmd

Provided by the celerite2 python package version 0.2.1 (Foreman-Mackey et al. 2017; Foreman-Mackey 2018

All Tables

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Out-of-transit and out-of-eclipse 30-min cadence TESS photometry of WASP-178 during sector 11 (left panel) and sector 38 (central panel). In each panel, the dashed vertical lines mark the planetary transit, and the solid blue line is a smoothing of the data points to emphasize the correlated noise. The right panel shows the GLS periodogram of sectors 11 and 38 (top and bottom box, respectively). In each box, we report the bootstrap-computed 0.1% and 1% FAP levels (horizontal dashes) and the planetary orbital period (vertical dotted red line). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Best fit of the transits and eclipses observed by TESS. Left: detrended and phase-folded planetary transits (top panel). The photometry of sectors 11 and 38 is shown with different colors to emphasize the difference in transit depth (the photometry of sectors 11 and 38 is systematically offset upward and downward, respectively, with respect to the best-fit transit profile). The solid blue line is the best-fit model, and the cyan lines represent 100 models corresponding to random samples of the MCMC fit. For the sake of comparison, the photometry of sector 38 and that of the theoretical models are rebinned to the same 30-min cadence as for sector 11. The black dots represent the rebinned photometry. The corresponding O-C diagram is shown in the bottom panel. Right: same as in the left panel, but centered on the eclipse. For clarity, we do not mark the two sectors with different colors. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 Upper limits on the reflected PC, dayside thermal PC, and night-side thermal PC for WASP-178 b. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4 Same as the right panel in Fig. 2 for the eclipses of WASP-178 observed by CHEOPS. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5 BT-Settl synthetic stellar spectrum for WASP-178 together with the CHEOPS and TESS passbands. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 6

|

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 7 Adaptation of Fig. 10 in Wong et al. (2021) including our analysis of WASP-178 b (in blue). The green squares indicate the systems from the first and second year of the TESS primary mission. The black circles indicate the Kepler- and CoRoT-band geometric albedos for the targets that were observed by those missions. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 8 Same as in Fig. 6 for α = 0.5. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. A.1 Corner plot of the MCMC chains of planetary parameters from the fit of the TESS transits (see Sect. 4.1.1). In each plot, the solid blue lines mark the MAP values. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. B.1 Detrended short-cadence LC of the first (left panel) and second (right panel) transit observed in TESS sector 38. In each panel, the top plot shows the model computed with the MAP parameters in Table 3 as the solid blue line. The bottom plots show the residuals of the short-cadence photometry with respect to the planetary model shown in the top panel. As a guide, we plot the smoothing of the residuals obtained with a Savitzky-Golay filter as the blue line. In all plots, the vertical dashed lines mark the first and fourth contact. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. B.2 Detrended short-cadence LC of the third (left panel) and fourth (right panel) transit observed in TESS sector 38. The details are the same as in Fig. B.1. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. B.3 Detrended short-cadence LC of the fifth (left panel) and sixth (right panel) transit observed in TESS sector 38. The details are the same as in Fig. B.1. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. B.4 Detrended short-cadence LC of the seventh (left panel) and eighth (right panel) transit observed in TESS sector 38. The details are the same as in Fig. B.1. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.