| Issue |

A&A

Volume 674, June 2023

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A195 | |

| Number of page(s) | 21 | |

| Section | Interstellar and circumstellar matter | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202243992 | |

| Published online | 22 June 2023 | |

Abundance and temperature of the outer hot circumgalactic medium

The SRG/eROSITA view of the soft X-ray background in the eFEDS field

1

INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Brera,

Via E. Bianchi 46,

23807

Merate (LC), Italy

e-mail: gabriele.ponti@inaf.it

2

Max-Planck-Institut für extraterrestrische Physik,

Giessenbachstrasse,

85748,

Garching, Germany

3

Dipartimento di Matematica e Fisica, Università degli Studi Roma Tre,

Via della Vasca Navale 84,

00146

Roma, Italy

4

Argelander-Institut für Astronomie (AIfA), Universität Bonn,

Auf dem Hügel 71,

53121

Bonn, Germany

5

Remeis Observatory and ECAP, Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg,

Sternwartstrasse 7,

96049

Bamberg, Germany

Received:

10

May

2022

Accepted:

11

October

2022

Context. Despite their vital importance to understanding galaxy evolution and our own Galactic ecosystem, our knowledge of the physical properties of the hot X-ray emitting phase of the Milky Way is still inadequate. However, sensitive SRG/eROSITA large area surveys are now providing us with the long-sought data needed to mend this state of affairs.

Aims. Our aim is to constrain the properties of the Milky Way hot halo emission toward intermediate Galactic latitudes close to the Galactic anti-center.

Methods. We analyzed the spectral properties of the integrated soft X-ray emission observed by eROSITA in the relatively deep eFEDS field.

Results. We observe a flux of 12.6 and 5.1 × 10−12 erg cm−2 s−1 deg−2 in the total (0.3–2) and soft (0.3–0.6 keV) band. We measure the temperature and metal (oxygen) abundance of the hot circumgalactic medium (CGM) to be within kTCGM = 0.153–0.178 keV and ZCGM = 0.052–0.072 Z⊙, depending on the contribution of solar wind charge exchange (SWCX). Slightly higher CGM abundances ZCGM = 0.05–0.10 Z⊙ are possible, considering the uncertain extrapolation of the extragalactic cosmic X-ray background (CXB) emission below ~1 keV. To recover CGM abundances as high as ZCGM = 0.3 Z⊙, the presence of an additional component must be postulated, likely associated with the warm-hot intergalactic medium, providing ~15–20% of the flux in the soft X-ray band. We observe line widths of the CGM plasma smaller than Δυ ≤ 500 km s−1.

The emission in the soft band is dominated (~47%) by the circumgalactic medium (CGM), whose contribution reduces to ~30% if heliospheric SWCX contributes at the level of ~15% also during solar minimum. The remaining flux is provided by the CXB (~33%) and the local hot bubble (~18%). Moreover, the eROSITA data require the presence of an additional component associated with the elusive Galactic corona plus a possible contribution from unresolved M dwarf stars. This component has a temperature of kT ~ 0.4– 0.7 keV, a considerable (~ kiloparsec) scale height, and might be out of thermal equilibrium. It contributes ~9% to the total emission in the 0.6—2 keV band, and is therefore a likely candidate to produce part of the unresolved CXB flux observed in X-ray ultra-deep fields. We also observe a significant contribution to the soft X-ray flux due to SWCX, during periods characterized by stronger solar wind activity, and causing the largest uncertainty on the determination of the CGM temperature.

Conclusions. We constrain temperature, emission measure, abundances, thermal state, and spectral shape of the outer hot CGM of the Milky Way.

Key words: X-rays: diffuse background / Galaxy: halo / local insterstellar matter / Galaxy: abundances / ISM: structure / ISM: general

© The Authors 2023

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model.

Open Access funding provided by Max Planck Society.

1 Introduction

We are living in a golden age for Galactic astrophysics. On the one hand, the Gaia satellite, together with large spectroscopic surveys are allowing us to understand the dynamics and composition of the stars of the Milky Way to a degree never reached before (Gaia Collaboration 2016, 2021; Majewski et al. 2017). On the other hand, the standard cosmological model dictates that the formation and evolution of Milky Way-like galaxies is governed by the elusive dark matter halo (White & Rees 1978; White & Frenk 1991; Dodelson & Efstathiou 2004; Mo et al. 2010). In particular, state-of-the-art cosmological simulations suggest that the dominant component of galactic baryons in the present-day Universe should reside in their halos, within the circumgalactic medium (CGM; Crain et al. 2010; Tumlinson et al. 2017; Bogdán et al. 2015; Kelly et al. 2021; Oppenheimer et al. 2020; Truong et al. 2020). Additionally, they predict that the growth and evolution of galaxies critically depend on the physics of the multiphase interstel lar medium (ISM) and CGM (Putman et al. 2012; Tumlinson et al. 2017; Naab & Ostriker 2017). In particular, the latter is expected to be dominated by its hotter component, which forms a rarefied plasma close to the virial temperature (kT ~ 0.15−0.2 keV) and extends to the virial radius (R ~ 200 kpc). Therefore, this plasma is expected to form a diffuse emission component over the entire sky. Despite its vital importance, our knowledge of the hot Galactic plasma has yet to be attained.

Since its discovery, the study of the cosmic X-ray background (CXB) has been a major field of research (Giacconi et al. 1962). The CXB appears as a uniform X-ray glow over the entire sky, whose energy spectrum has been measured to be consistent with a power law with photon index of Γ ~ 1.45 in the 2–10 keV band, which then breaks to a steeper slope, therefore creating a peak in the energy spectrum at around ~30 keV; the CXB then rolls over at higher energies (Marshall et al. 1980; Vecchi et al. 1999; Revnivtsev et al. 2003, 2005; De Luca & Molendi 2004; Hickox & Markevitch 2006; Kushino et al. 2002; Gilli et al. 2007). In particular, the advent of XMM-Newton and Chandra have allowed us to make giant leaps forward in our understanding of the CXB, thanks to an array of extragalactic surveys going from the ultra-deep (~7 Ms) pencil beam exposures (Luo et al. 2017) to much larger area but shallower surveys (see Brandt & Yang 2022 for a review).

These extragalactic surveys reveal that the majority of the X-ray background above ~0.5 keV is composed of a large number of faint distinct sources. They allowed us to resolve more than ~80% and ~92% of the CXB flux into discrete sources (i.e., active galactic nuclei, AGN; clusters of galaxies; groups; normal galaxies) in the 0.5–2 and 2–7 keV band, respectively (Luo et al. 2017; Brandt & Yang 2022). Instead, the X-ray background appears to be truly diffuse at the softest energies below ~0.5 keV.

In the 1990s, the all-sky ROSAT maps revolutionized our understanding of the X-ray background in the softer energy band (Snowden et al. 1991, 1994, 1995, 1997). In particular, the sensitive ROSAT images revealed that the soft X-ray background is highly inhomogeneous and fills the entire sky (1991, 1997). The ROSAT data allowed astronomers to disentangle the emission from the local hot bubble (LHB) from the Galactic-scale emission. The former component manifests itself as a hot (kT ~ 0.1 keV) bubble surrounding the Sun with a radius of ~200 pc (Liu et al. 2017; Zucker et al. 2022), therefore dominating the cosmic X-ray background (CXB) in the softest band (E < 0.2 keV; Liu et al. 2017). At energies in the range ~0.2–0.6 keV the Galactic-scale emission dominates over the LHB and the CXB1. This Galactic component was interpreted as either a Galactic corona, which would be produced by a thickened disk with a scale height of a few kpc, or as the emission from the hot halo, extending out to the virial radius (rv ~ 200 kpc). Unfortunately, the low energy resolution of the ROSAT cameras did not allow astronomers to disentangle the emission lines from the thermal continuum. Therefore, accurate measurements of the temperature and abundances of this Galactic component was not feasible. One of the major results of this work is the characterization of the physical properties (i.e., temperature, emission measure, abundances) of the Galactic component. Another result is demonstrating that the CGM2 and the Galactic corona components are both required by the eROSITA data. Finally, it is important that we verified that the steep continuum (which we associate with hot baryons in the warm-hot intergalactic medium) can contribute with a flux of less than ~10−12 erg cm−2 s−1 deg−2, in the 0.3–0.6 keV band, if the CGM abundances are high (ZCGM ≫ 0.1 Ζ⊙).

Over the last two decades, by accumulating hundreds of XMM-Newton and Suzaku observations, astronomers have tried to constrain the soft X-ray emission from the Milky Way (Henley et al. 2010; Henley & Shelton 2012, 2013, 2015; Miller & Bregman 2013, 2015; Miller et al. 2016; Yoshino et al. 2009; Nakashima et al. 2018). They have shown that the Galactic X-ray emission, outside of the Fermi bubbles, can be reproduced by either a beta model with kT ~ 0.2 keV and an extension of several hundred kpc (with abundances assumed to be ZCGM = 0.3 Ζ⊙; Miller et al. 2016; Bregman et al. 2018) or by an exponential atmosphere with a scale height of a few kiloparsec (Yao & Wang 2005, 2007; Yao et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2005; Wang 2009, 2010). Additionally, studies of absorption lines imprinted on the spectrum of a few dozen bright AGN and of the dispersion measure of fast radio bursts provide further observational evidence for the presence of either a hot halo around the Milky Way or an exponential atmosphere (Fang et al. 2015; Miller & Bregman 2015; Prochaska & Zheng 2019). Some of the most recent results include both components; however, they often find the halo component to be dominant (Bregman et al. 2018).

Very instructive is the comparison of what is observed in nearby galaxies. Surprisingly, deep observations of single normal galaxies have often failed to detect an X-ray halo extending to the virial radius, such as the one believed to be surrounding the Milky Way (Wang et al. 2001, 2003; Anderson & Bregman 2011; Anderson et al. 2016; Li & Wang 2013a,b; Li et al. 2017). The clearest detections of hot Galactic plasma were reported around edge-on massive spirals where the hot plasma is observed to form a thick atmosphere, like a corona, extending several kilo-parsec above and below the disk (Anderson & Bregman 2011; Anderson et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2001, 2003). Only stacks of samples of galaxies allowed to reach the signal-to-noise ratio required to detect the hot halo beyond several tens of kiloparsec (Anderson et al. 2015; Li et al. 2018; Comparat et al. 2022).

In addition to the intrinsic challenges associated with the detection of such faint and extended galactic halos, an additional complication typically affects the soft X-ray band. It has been demonstrated that the process of charge exchange between the ionized particles of the solar wind with neutrals within the heliosphere can induce a time-variable component to the soft X-ray background, which can be significantly brighter than these galactic halos (Snowden et al. 2004; Kuntz 2019).

With more than three million photons in the soft X-ray band, the eROSITA (Predehl et al. 2021) Final Equatorial Depth Survey (eFEDS) provides us with an unprecedented possibility to study the characteristics of the soft X-ray background (Snowden et al. 1997). The survey, defined during the eROSITA performance verification phase, comprises about 142 square degrees, observed to a uniform depth of ~2.2 ks in 2019 (Brunner et al. 2022), and re-observed as part of the ongoing all-sky survey program in 2020 and 2021.

2 Dataset and data reduction

We use both the public eROSITA data from the eFEDS field collected during the performance verification (sometimes abbreviated as PV) phase, which we refer to as e0, and the data from the same region accumulated during the first three passes of the all sky survey, which we refer to as el, e2, and e3, respectively. We refer to the sum of the data from the first two passes3 as e12 (see our Fig. 1; Brunner et al. 2022).

The eFEDS field covers ~142 square degrees, extending from Galactic latitude / from ~220° to ~235° and from Galactic longitude b from ~20° to ~40° (see Fig. 1). To avoid possible complications occurring at the edges of the eFEDS region, we focus our analysis on the rectangular cyan region shown in Fig. 1, which spans 107.5 square degrees on the sky. A similar surface brightness and color is observed both within the eFEDS field and in regions away from the Galactic plane and away from the Galactic center (Fig. 1). This suggests that the diffuse X-ray emission from the eFEDS field is likely characteristic of the diffuse emission away from the Galactic plane and center. Therefore, it represents an excellent field to study the emission from the soft X-ray background, which is not impacted by the Galactic outflow (Sofue 2000; Bland-Hawthorn & Cohen 2003; Su et al. 2010; Ponti et al. 2019, 2021; Predehl et al. 2020). In this work we consider the total emission from this region, including point sources, extended sources, diffuse emission, and background.

We investigated the temporal evolution of the particle background during the eROSITA observations of the eFEDS field and we found, in e3, an instance (possibly associated with a coronal mass ejection) where the particle background is enhanced by ~80% and ~30% in the 2.3–4.5 and 0.3–1.4 keV bands, respectively. No such events are observed during e0, e1, or e2. In particular, Fig. B.1 shows the comparison between the e12 spectrum applying the filtering for background flares (with the FLAREGTI tool) and not. The consistency between these spectra corroborates that important background flares do not affect the e12 spectrum; therefore, they do not have an effect on the results obtained here.

The eFEDS field was observed with an exposure depth of approximately ~2.2 ks during the PV phase (e0), and for about ~250 s during each of the three all-sky surveys. The eFEDS field was scanned by eROSITA during the following periods: 3–9 November 2019 during e0; 30 April–14 May 2020 during e1; 1–14 November 2020 during e2; and 3–15 May 2021 during e3. We reduced the data with the eSASS Software version 947 (Brunner et al. 2022). In particular, we utilized the user release eSASSusers_201009 from October 2020, which has significant improvements in the energy calibrations of each camera (Dennerl et al. 2020). We considered only single and double events.

To avoid contamination from light leak (Predehl et al. 2021), which affects the cameras TM5 and TM7, we used only the “on-chip” filter cameras: TM1, TM2, TM3, TM4, and TM6.

We fit all spectra with the XSPEC software (Arnaud 1996) version 12.11.1. Uncertainties are reported at the 1σ confidence level for one interesting parameter unless stated otherwise. We used the χ2 statistics to fit separately the different TM cameras aboard eROSITA (although tying all parameters of the model reproducing the emission from the sky); however, we show the combined spectra and residuals for display purposes only. We assume the Lodders (2003) abundances and Verner et al. (1996) cross sections, unless stated otherwise.

|

Fig. 1 Footprint of the eFEDS field on the eROSITA RGB sky map, as observed during e12. Red, green, and blue indicate the emission in the 0.3–0.6, 0.6–1.0, and 1.0–2.3 keV energy bands. The radiation within the eFEDS field is rather homogeneous and characteristic of the soft X-ray emission observed at latitudes away from the Galactic plane and away from the Galactic center. The dark stripe along the Galactic plane is primarily the byproduct of higher extinction there. |

3 Absorption

We estimated the column density of Galactic neutral material from the HI4PI data cube4 (HI4PI Collaboration 2016). We divided the ~107.5 square degrees of the eFEDS field that we analyzed into pixels of 11.7 square arcminutes (0.00325 square degrees) and recorded the average column density in the HI4PI map within these pixels. By approximating the observed distribution with a log-normal, we measured a mean column density of neutral hydrogen of log(NH/cm−2) = 20.51 and standard deviation  . Hereafter, following Locatelli et al. (2022), we reproduce the effects of the observed distribution of the neutral absorption column densities by employing the disnht model.

. Hereafter, following Locatelli et al. (2022), we reproduce the effects of the observed distribution of the neutral absorption column densities by employing the disnht model.

4 Impact of the instrumental background

Figure 2 shows the total emission from the eFEDS field, including all point and extended sources, diffuse emission from the sky, and instrumental background. Thanks to the analysis of the filter wheel closed data, the eROSITA team developed a model of the instrumental background for each camera aboard eROSITA. These models are shown as dotted lines in Fig. 2 (see also Fraternali 2017). At energies above ~0.5–1 keV, the instrumental background is dominated by a flat power law with a photon index close to Γ = 0, plus a series of emission lines that are induced by interactions of particles with the detectors and other components of the satellite. At energies below ~0.5 keV, an increase in the background level is observed as a consequence of electronic noise (see the steep power-law shape dominating at low energy).

We observe that the instrumental background dominates over the sky emission at energies below E ≲ 0.25 keV and above E ≳ 1.5 keV (Fig. 2). We first perform a fit of the spectrum of each camera over the entire energy range from 0.2 to 3 keV. We use a different instrumental background model for each camera, as specified by the eROSITA team (Fraternali 2017). For each camera, all the parameters of the instrumental background model are fixed, apart from a normalization factor which is adjusted, to the value necessary to fit the data above 2 keV, where the background is almost a factor of ~5–10 stronger than the emission from the sky5. Then, for each camera, we fix the normalization of the internal background model to the observed best fit parameter and subsequently leave it fixed to that value. We note that this technique is able to adjust for the variations in the rate of particles inducing hard X-ray emission; however, it is not suitable for determining the noise component below 0.25 keV, which is caused by different effects, and thus not strictly correlated with the high energy background. We observe large residuals below ~0.3 keV (Fig. 2). Therefore, considering the still limited knowledge of the instrumental background and its evolution with time, we decided to fit the spectrum only within 0.3 and 1.4 keV to reduce the impact of the possible variations in the instrumental background on our best fit models.

|

Fig. 2 Total X-ray emission from the eFEDS field as observed by eROSITA. The spectra contain emission from all point-like and extended sources, diffuse emission from the sky, and instrumental background. Black, red, green, blue, and cyan data indicate the spectra observed with the TM1, TM2, TM3, TM4, and TM6 cameras aboard eROSITA, respectively. The solid lines show a model aiming to reproduce the integrated emission from the sky (point-like and extended sources plus diffuse emission), while the dotted lines show the model for the instrumental background derived from the filter wheel closed data (Fraternali 2017). |

5 Solar wind charge exchange (SWCX)

The interaction of the ionized particles of the solar wind with the flow of neutral ISM that constantly passes through the helio-sphere produces diffuse soft X-ray emission by charge exchange (Snowden et al. 2004; Kuntz 2019). The brightness of this component is expected and observed to be modulated by the properties of the solar wind, and therefore to be variable over time. Thanks to the scanning strategy of eROSITA, we can probe all these timescales, and thus verify the impact of any variable components on the observed emission.

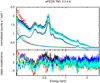

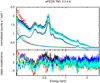

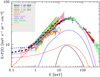

5.1 Variations induced by SWCX

The black, red, green, and blue data in the left panel of Fig. 3 show the total X-ray emission (including point sources, extended sources, diffuse emission, and background) as observed by eROSITA in the eFEDS field during e1, e2, e3, and e0 (the PV phase observations), respectively6. The diffuse emission has a low value and it is constant during e1 and e2. The data points of the e1 and e2 spectra are consistent with each other over the ~0.3–1.4 keV energy band (Fig. 3). On the other hand, enhanced emission is observed between ~0.3–0.7 keV during e3 and e0. In particular, the peak flux of the O VII line increases from ~2.6 to ~3.3 ph s−1 keV−1 cm−2, corresponding to an increase of ~25% during e3 (see inset of Fig. 3). For this reason, hereafter we consider primarily the data taken during e1 and e2.

To determine the total O VII and O VIII line intensities observed during e12, we fitted the e12 spectrum, within a narrow energy band (0.45–0.75 keV), with an absorbed power law and two narrow Gaussian lines plus the instrumental background7. We obtain best fit intensities for the O VII and O VIII of  and

and  , respectively.

, respectively.

5.2 Constraining SWCX from the difference spectrum

The right panel of Fig. 3 shows the spectrum of the variable component obtained from the difference of the spectrum observed during e3 minus that observed during e1. In this way, all constant components are subtracted, leaving only the variable emission.

We fit the difference spectrum with a solar wind charge exchange model (ACX2 model in XSPEC, which is part of the ATOMDB package; Smith et al. 2012; Foster et al. 2020). We assume solar abundances8 and single recombination9. Additionally, we assume a collision speed velocity of 450 km s−1, in order to reflect the solar wind speed; however, we tried two different implementations of this velocity. The first attempt assumes that 450 km s−1 corresponds to the center of mass velocity, while the second trial assumes that it corresponds to the donor ion velocity. The right panel of Fig. 3 shows that an acceptable fit can be obtained with the first attempt (black line), while the second trial leaves unacceptable residuals. Therefore, hereafter we assume a collision speed velocity of 450 km s−1, corresponding to the center of mass velocity.

The best fit plasma temperature of the ionized component and the fraction of neutral helium are kT = 0.136 ± 0.007 keV and FHe0 > 0.2, with a normalization of 0.25 ± 0.09, corresponding to an average flux of 7.4 × 10−11 erg cm−2 s−1 over the eFEDS area in the 0.4–0.6 keV band, which correspond to 6.9 × 10−13 erg cm−2 s−1 deg−2 (χ2 = 168.4 for 161 d.o.f.; see Table 1). On the one hand, we note that such values are consistent with this emission being produced by solar wind charge exchange. On the other hand, we note that the spectrum is composed of the variable component only (missing the emission from the constant component); therefore, it is most likely that the best fit values are biased, hampering us from going into a deeper investigation of this effect in this work.

|

Fig. 3 Left panel: Diffuse X-ray emission as observed by eROSITA in the eFEDS field during e1, e2, e3, and e0 (eRASS1, eRASS2, eRASS3, and PV phase observations) in black, red, green, and blue, respectively (the emission from different TMs is combined for display purposes). An enhancement at the energies of the soft X-ray emission lines is observed during e3, compared with e1 and e2. This enhancement is characterized by a spectral shape characteristic of the emission induced by SWCX. A similar enhancement is observed during e0. The inset shows an enlargement of the spectra around the O VII line where the enhancement is most evident. Right panel: Spectrum of the variable diffuse emission component fitted with a model for the SWCX. The black line shows the best fit model, while the red line shows a different implementation of the same model. |

Best fit parameters of the variable component of the emission observed in the eFEDS field, once the difference spectrum (e3 minus e1) is fitted with the acx2 model.

5.3 Spatial distribution of the excess emission and association with heliospheric SWCX

We investigated the map in the 0.5–0.6 keV band of the emission observed during e3, which is characterized by a more intense solar wind. From the map accumulated during e3, we subtracted the emission in the same band accumulated during e12. The difference map is consistent with a constant excess over the entire region. This confirms that the SWCX emission is associated with an increased glow over the entire eFEDS region (see Ponti et al. 2023), indicating that the excess of SWCX emission occurs on timescales longer than ~6 days, which is the time it took to scan the eFEDS region.

This behavior appears to be remarkably different from the variability pattern observed in XMM-Newton and Chandra data, where the variations induced by SWCX occur on timescales of hours or days. It is likely that the high Earth orbit of XMM-Newton and Chandra make them more sensitive to the rapidly variable SWCX emission occurring at the edge of the Earth’s magnetosphere (Snowden et al. 2004; Kuntz 2019), while for the orbit around L2 of eROSITA this component is missing, so that eROSITA is sensitive to the more slowly varying heliospheric component of the SWCX emission (Kuntz 2019; Dennerl et al., in prep.).

5.4 SWCX emission during e12

Our analysis demonstrates that SWCX is present during e0 and e3, while it still remains to be demonstrated whether SWCX is present also during e1 and e2. Theoretical arguments suggest that this component must also be present at solar minimum, although at a lower level.

Currently, various attempts are in progress to establish the contribution to the total emission due to SWCX during e1 and e2.

Through a preliminary investigation of the evolution in time of the SWCX component, Dennerl et al. (in prep.) are estimating a count rate in the 0.4–0.6 keV band of ~0.068, ~0.074, and ~0.16 ph s−1 cm−2 within the eFEDS field during e1, e2, and e3, respectively. These estimates are consistent with the flux of the SWCX component observed by analyzing the e3 minus e1 spectrum (with a count rate of 0.09 ph s−1 cm−2 and flux (6.9 ± 1.5) × 10−13 erg cm−2 s−1 deg−2 in the 0.4–0.6 keV band; see Table 1). Assuming the SWCX spectrum observed in Sect. 5.2, these values correspond to a flux of ~1.2 ph s−1 cm−2 sr−1 in the O VII line during e12.

Through the study of the nearby Ophiuchus dark cloud, Yeung et al. (2023) are preliminarily estimating the flux of the SWCX component observed by eROSITA. Yeung et al. (2023) observe a flux of FSWCX = (2.1 ± 0.6) × 10−13 and FSWCX = (6.1 ± 0.7) × 10−13 erg cm−2 s−1 deg−2 in the 0.4–0.6 keV band toward the Ophiuchus cloud during e1 and e2, respectively. These estimates are ~1.7 times lower than the previous values, and they might be the consequence of the different lines of sight or of the different times of observation10. Alternatively, they might reflect the intrinsic uncertainty in determining the intensity of the SWCX component. Considering the different SWCX model assumed by Yeung et al. (2023), the above 0.4–0.6 keV surface brightness translates into a flux of ≤ 1.0 ph s−1 cm−2 sr−1 in the O VII line during e12.

Qu et al. (2022) have studied the temporal variation of the O VII and O VIII flux, as observed by XMM-Newton, over one solar cycle. They found a significant variation induced by the heliospheric SWCX component, which shows a minimum close to the solar minimum. In particular, they estimated the true Galactic O VII and O VIII emission lines to have mean values on the order of ~5.4 and 1.7 ph s−1 cm−2 sr−1, respectively. We note that such values are about a factor of ~1.7 and ~6 times higher than the line intensities toward the eFEDS field. This is in line with the fact that we are looking toward a line of sight away from the Galactic outflow, and corroborates the fact that in the e12 spectrum the effects of SWCX are minimal. Additionally, we note that the O VII flux measured by Qu et al. (2022) close to solar minimum are consistent with being entirely due to the Galactic O VII emission. This suggests, therefore, a negligible contribution due to heliospheric SWCX during solar minimum, such as during e12.

We take the differences between these preliminary estimates of the normalization of the SWCX component during e12 as a measure of the current uncertainty on its contribution, which goes from a negligible fraction to a flux of ~1.2 ph s−1 cm−2 sr−1 in the O VII line.

6 Definition of the initial model

In this section we spell out all the ingredients that compose the initial model of the spectrum and that we consider in the following fits.

To minimize the contribution of the emission from SWCX, we fit the e12 spectra alone. Even though the e0 spectrum has a better signal-to-noise ratio, the large and not-well-tracked fluctuations of the flux of the various ions composing the solar wind would induce significant systematic uncertainties to the best fit of e0 and e3.

6.1 SWCX

We assume that the emission from SWCX is subdominant during e12. This is corroborated by the observation that i) the spectra observed during e1 and e2 are consistent with each other; ii) the energy of the O VII triplet is shifted toward the resonant line (Sect. 8.1); and iii) the lines and continuum are consistent with being produced by an optically thin thermal plasma. SWCX is expected to be intrinsically time-variable (as a consequence of the variability of the solar wind, among other effects; Dennerl et al., in prep.); it is characterized by O VII triplets dominated by the forbidden line and has a continuum different from a bremsstrahlung; therefore, it is unlikely to provide a dominant contribution during e1 and e2.

On the other hand, to quantify how our ignorance on the flux of the SWCX component during e12 propagates into our best fit results, we performed two sets of fits. One where we assume that the SWCX emission can be completely neglected. The second one assumes a SWCX component with an intensity as large as estimated by Dennerl et al. (in prep.), and therefore corresponding to a flux of (6.9 ± 1.5) × 10−13 erg cm−2 s−1 deg−2 in the 0.4–0.6 keV band and a spectral shape constrained by the e3-e1 difference spectrum (Table 1; Sect. 5.2).

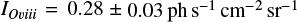

6.2 Cosmic X-ray background (CXB)

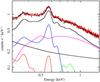

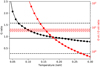

The integrated emission from the cosmic X-ray background, as measured by different X-ray instruments is shown in Fig. 4 (figure from Gilli et al. 2007)11. Over the ~1 to ~10 keV energy range, the CXB can be described with a simple absorbed power-law model (POWERLAW model in XSPEC) with photon index fixed to Γ = 1.45 and a normalization of ~10.5 ph cm−2 s−1 sr−1 at 1 keV (see red dotted line in Fig. 4)12. We refer to this model component as CXBh. Additionally, considering its extragalac-tic nature, we assume that the CXB is absorbed by the full column density of Galactic absorption. Detailed studies with Chandra, XMM-Newton, ROSAT, and other X-ray instruments have resolved more than ~95 % of this component into point sources (AGN) and galaxy clusters, in the 2–8 keV energy range (Hasinger et al. 1993; Hickox & Markevitch 2006; Revnivtsev et al. 2003; Liu et al. 2017). We note that the CXB normalization of ~ 10.5 ph cm−2 s−1 sr−1 at 1 keV for a photon index of Γ = 1.45 corresponds to a normalization of ~0.34 ph cm−2 s−1 at 1 keV within the eFEDS field of ~ 107.5 square degrees. Unless otherwise stated, we leave the normalization of the CXB component to be free in the fits and we verify a posteriori whether the normalization of the CXB is within the range allowed by the cosmic variance.

We note that the CXB synthesis models also containing the contribution from groups and clusters suggest that there might be a steepening of the CXB slope at energies below ~1 keV (Gilli et al. 2007). To reproduce this steepening we considered a double broken power-law model, which is assumed to be identical to the simple power-law model above 1.2 keV, but producing a higher flux at lower energies (black dashed line in Fig. 4). The double broken power law has a photon index of Γ1 = 1.9 below 0.4 keV, then Γ2 = 1.6 between 0.4 and 1.2 keV, and then Γ3 = 1.45 above 1.2 keV, with a normalization of 8.2 photons s−1 cm−2 sr−1 at 1 keV (corresponding to 0.269 photons s−1 cm−2 at 1 keV over the eFEDS area). This appears as the most realistic representation of the constraints on the CXB accumulated to date (Gilli et al. 2007), and therefore we use this component (which we refer to as CXB) in all our fits, unless stated otherwise.

We also note that the observed data show a large scatter below ~ 1 keV (Fig. 4). Therefore, we define a third model, which is still in rough agreement with the observational data and maximizes the emission in the soft X-ray band (see blue dashed line in Fig. 4). The model has a double broken power-law shape with a photon index of Γ1 = 1.96 below 0.6 keV, then Γ2 = 1.75 between 0.6 and 1.2 keV, and then Γ3 = 1.45 above 1.2 keV, with a normalization of 8.5 photons s−1 cm−2 sr−1 at 1 keV (black dashed line in Fig. 4). We refer to this model as CXBs and we employ it (alongside CXBh) in Sect. 8 in order to understand how our assumptions on the CXB might systematically impact our results.

|

Fig. 4 Cosmic X-ray background spectrum observed by different instruments (see legend at top left) (from Gilli et al. 2007). The solid lines show the predicted contribution from the different components. The black, blue, red, and magenta lines show the emission from Compton-thick, obscured Compton-thin, unobscured AGN, and total AGN plus galaxy cluster emission, respectively. The red dashed line shows the simplified CXB model often assumed in the literature, composed of a power-law shape with photon index Γ = 1.45 and normalization of 10.5 photons s−1 cm−2 sr−1 at 1 keV (referred to as CXBh in this work). In particular, this model fails to properly reproduce the data below ~1 keV. The black dashed line shows the double broken power-law model, defined in order to better reproduce the constraints on the cosmic X-ray background emission below ~1 keV (referred to as CXB in this work). It is composed of a power law with photon index of Γ1 = 1.9 below 0.4 keV, then Γ2 = 1.6 below 1.2 keV and then Γ3 = 1.45 above 1.2 keV, with a normalization of 8.2photons s−1 cm−2 sr−1 at 1 keV. The blue dashed line shows a double broken power law, chosen to maximize the cosmic X-ray emission from extragalactic sources, which is composed of a power law with photon index of Γ1 = 1.96 below 0.6 keV, then Γ2 = 1.75 below 1.2 keV, and then Γ3 = 1.45 above 1.2 keV, with a normalization of 8.5 photons s−1 cm−2 sr−1 at 1 keV (referred to as CXBs in this work). |

6.3 Local hot bubble

The Sun is located within a bubble of hot plasma with a temperature of kT ~ 0.1 keV and an extension of ~102 parsec, which fills the local cavity (therefore it is unabsorbed in the X-ray band). This bubble is typically called the local hot bubble (LHB), (Cox & Snowden 1986; Snowden & Schmitt 1990; Galeazzi et al. 2014; Liu et al. 2017). Following the work of Liu et al. 2017, we assume that the emission from the LHB is well reproduced by a hot plasma component in thermal equilibrium (APEC model in XSPEC) with a temperature of kT = 0.097 keV. Additionally, we assume that this component is unabsorbed, being located within only a few 102 parsec from the Sun. Finally, we assume that it has solar abundance. From Fig. 6 of Liu et al. (2017), we estimate the average emission measure associated with the LHB in the eFEDS field, which results to be 0.00266 cm−6 pc. The APEC normalization Napec is defined as  , where ne and nH are the electron and hydrogen densities (in cm−3), respectively, V is the volume (cm−3) and DA is the angular diameter distance (in cm; see Xspec User Manual13). This can be written as

, where ne and nH are the electron and hydrogen densities (in cm−3), respectively, V is the volume (cm−3) and DA is the angular diameter distance (in cm; see Xspec User Manual13). This can be written as  , where A is the section of the volume V perpendicular to the line of sight and whose extension along the line of sight is l, and θ is the subtended solid angle (in units of steradian). Considering the projected area on the sky of the eFEDS field, which is ~107.5 square degrees, corresponding to 0.0327 sr, this becomes

, where A is the section of the volume V perpendicular to the line of sight and whose extension along the line of sight is l, and θ is the subtended solid angle (in units of steradian). Considering the projected area on the sky of the eFEDS field, which is ~107.5 square degrees, corresponding to 0.0327 sr, this becomes ![${N_{{\rm{apec}}}} = {10^{ - 14}}{{0.0327} \over {4\pi }}3.09 \times {10^{18}} \times {\rm{EM}}\left( {{\rm{pc}}\,{\rm{c}}{{\rm{m}}^{ - 6}}} \right) \sim 80 \times {\rm{EM}}\,\left[ {{\rm{pc c}}{{\rm{m}}^{ - 6}}} \right]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2023/06/aa43992-22/aa43992-22-eq6.png) . Hereafter, we convert all best fit APEC normalizations from Xspec into Napec (pc cm−6). As for the CXB, we leave the normalization of the LHB free to vary and we check a posteriori whether its value agrees with that observed by ROSAT (Liu et al. 2017).

. Hereafter, we convert all best fit APEC normalizations from Xspec into Napec (pc cm−6). As for the CXB, we leave the normalization of the LHB free to vary and we check a posteriori whether its value agrees with that observed by ROSAT (Liu et al. 2017).

6.4 Circumgalactic medium

Finally, we assume that the emission from the circumgalactic medium is composed of hot plasma in thermal equilibrium (APEC model in XSPEC).

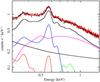

7 Detection of the elusive Galactic corona

We start our investigation by fitting the eFEDS spectrum with three components: two thermal components (APEC models in XSPEC) of which one for the LHB (red line in Fig. 5) and one for the CGM (blue line in Fig. 5) and a double broken power law for the CXB (magenta line in Fig. 5), in addition to the instrumental background (black line in Fig. 5 and Table A.1) and, when specified, the SWCX emission (cyan line in the right panels of Fig. 5). We note that, as a consequence of our assumptions, the spectral shape of the LHB and the CXB are fixed, and therefore only their normalizations are allowed to vary in the fit.

We first investigated the effects of assuming different sets of abundances (see Appendix A) and decided to assume the solar abundances measured by Lodders (2003).

7.1 Signature of the Galactic corona: What is the contribution from faint dwarf M stars?

Regardless of the assumed abundances and whether we include or not the SWCX component, the top panels of Fig. 5 show large residuals at the energy of the O VIII line and between ~0.7 and 1 keV. The spectrum shows a hump between ~0.7 and ~1 keV that cannot be fit by the power-law shape of the CXB (Fig. 5).

To reproduce this hump the continuum of the CGM component would need to have a temperature in excess of kT ≥ 0.2 keV. On the other hand, the O VII / O VIII line ratio forces the best fit temperature to be lower than ~0.2 keV. The result of this tension is displayed by the very bad residuals in the top panels of Fig. 5.

Such bad residuals represent incontrovertible evidence that an additional element is required to reproduce the eROSITA data. Therefore, we add to the model a second thermal component to fit the emission from the Galactic corona. We initially assume the Galactic corona to be collisionally ionized, in thermal equilibrium, and optically thin. Therefore, we assume that it can be described by an APEC model in XSPEC. We further assume the metal abundance within the Galactic corona to be relatively high (based on the belief that the plasma might be deeply related with fountains and outflows from the interstellar medium in the plane of the Milky Way), and therefore we assume solar abundances for this component (Shapiro & Field 1976; Spitzer 1990; Bregman 1980; Fraternali 2017)14.

A very significant improvement of the fit is observed by the addition of the spectral component describing the emission of the Galactic corona, which correspond to Δχ2 = 175.3 and Δχ2 = 107.6 for the addition of two free parameters in the case of negligible and high SWCX contribution, respectively (see Table 2). The model comprising the Galactic corona, in addition to the three other components, now reproduces the bulk spectral features in the soft X-ray spectrum (see Fig. 5). The best fit temperature of the Galactic corona is kTCoro ~ 0.70–0.75 keV, which is significantly higher than that of the CGM and somewhat lower but in line with what is typically observed along the Galactic plane (and at the Galactic center) and attributed to the hot phase of the interstellar medium (e.g., kT ~ 1 keV; Ponti et al. 2013 and references therein).

Along the Galactic disk a thermal component with a temperature of kT ~ 0.7 keV, therefore with characteristics similar to the Galactic corona, has been observed in Suzaku data and it has been attributed to the cumulative emission due to faint dwarf M stars (Masui et al. 2009). Additionally, observations with X-ray quantum calorimeters aboard sounding rockets achieved measurements of the soft X-ray emission with unprecedented spectral resolution from four large locations within field of view of ~1 sr (McCammon et al. 2002, 2008; Wulf et al. 2019). Wulf et al. (2019) detected a spectral feature at E ~ 0.9 keV that can be fitted with a hot emission component (kT ~ 0.7 keV), in addition to the CGM, the LHB, and the SWCX emission, in the two fields crossing the Galactic plane, while such emission was absent at high Galactic latitudes. In Masui et al. (2009), the authors attributed such emission to the contribution of faint dwarf M stars. From the M dwarf model in Wulf et al. (2019), we estimate a contribution from M dwarfs toward the direction of the eFEDS field to be about half of the observed value of 0.9 × 10−3 pc cm−6. Therefore, not only are stars expected to give a significant contribution to this coronal emission, but they could also, in principle, be dominating over the emission from the Galactic corona, according to the model proposed by Wulf et al. 2019).

However, we note that the uncertainty on the knowledge of the scale height of the Galactic disk can induce significant scatter in the predicted contribution due to stars. More recent models of the mass distribution and gravitational potential of the Milky Way refine the disk scale height assumed by Wulf et al. (2019), therefore predicting a different contribution due to stars at the relatively high Galactic latitudes characteristic of the eFEDS field. Although this will be the subject of a future investigation that carefully addresses this point, we note that the observation of super-virial plasma in absorption toward some bright AGN (Das et al. 2019a, 2021) corroborates the presence of truly diffuse Galactic hot coronal plasma.

For these reasons, hereafter we associate the hot emission toward the eFEDS field to the Galactic corona; however, we note that a fraction of this emission is most likely due to stars. Soon, by connecting the improved mass distributions of the Milky Way with the advances in our knowledge of the X-ray emission from stars allowed by eROSITA, it will be possible to obtain much improved understanding of the contribution by stars to the overall observed hot plasma emission.

Best fit parameters obtained by fitting the eFEDS e12 spectrum with different models.

7.2 Systematic uncertainty on the energy scale calibration?

The middle panels of Fig. 5 still show positive residuals at the energies of the blue wing of the O VII emission line and negative residuals at the energy of the red wing of the same line.

To investigate the origin of these residuals, we fitted the spectrum with a parametric continuum model plus an array of emission lines. To perform this task, we further restricted the energy band over which we perform the fit to the 0.3– 0.9 keV energy range, where the most prominent emission lines dominate over the continuum. We fitted the continuum with a power law (with photon index free to vary) plus a thermal component with no emission line (APEC component with no emission line). Additionally, we added four emission lines to reproduce the O VII, the O VIII, and the C VI emission, plus a weaker line at E ~ 0.423 keV to reproduce the N VI triplet.

The energies and normalizations of the emission lines are free to vary, while their widths are fixed to σ = 1 eV for the hydrogen-like lines, while to σ = 4 eV for helium-like lines, to account for the ensemble of the triplet lines. The top and bottom panels of Fig. 6 show the best fit energy of the O VII and O VIII emission lines, respectively, as observed by the different cameras aboard eROSITA, during e12 and e0 in black and red, respectively. The horizontal dashed lines indicate the expected energies of the lines (the three lines show the energies of the O VII triplet). The error bars reported in Fig. 6 correspond to the 1σ statistical uncertainty, as derived from the fit.

The energy of the O VII line in the e0 spectra (which has the highest signal-to-noise ratio) is determined with high precision (see Fig. 6). Such small statistical uncertainties reveal the systematic uncertainties associated with the reconstructed absolute line energy for each camera, which does not exactly match the incident line energy (see Dennerl et al. 2020). In particular, we observe a systematic shift that can be as large as ΔE ~ 2–3 eV at the energy of the O VII line15, which is consistent with the current calibration of the energy scale (Dennerl et al. 2020).

From the results above, we conclude that the analysis of spectra containing emission lines is very demanding with respect to the energy calibration as errors in the absolute energy scale of a few eV can already cause significant residuals and may lead to wrong conclusions. In order to mitigate this problem, we allow for fine adjustments of the absolute energy scale in the spectral fits of the total spectrum by using a velocity shift (VASHIFT component in Xspec; see Table 2 and bottom panel of Fig. 5). Although this technique should conceptually be understood only as an approximation, the resulting energy shifts seem to be sufficiently small to justify this simplified approach. A significant improvement of the fit (Δχ2 = 27.7 and Δχ2 = 30.5 for the addition of five free parameters in the case of negligible and high SWCX contribution, respectively; see Table 2) is observed by the addition of a shift in the energy scale. The standard deviation of the observed shifts is σ ~ 1 eV, at the O VII line energy, and it can be as large as ~3 eV.

|

Fig. 5 Top left panel: Diffuse emission as observed by eROSITA within the eFEDS field during e12, fitted with a three-component model (LHB-CGM-CXB in Table 2). The red, blue, magenta, and black solid lines show the contribution from the local hot bubble, circumgalactic medium, cosmic X-ray background, and instrumental background, respectively. The dotted lines show the various contributions to the instrumental background. Top right panel: Same as top left panel, once the contribution from SWCX is added to the model (LHB-CGM-CXB-SWCX). The cyan line shows the contribution due to SWCX. Central left panel: The addition of the emission from the Galactic corona (solid green) significantly improves the fit (LHB-CGM-Coro-CXB). However, significant positive residuals (at the position of the vertical dashed lines) remain at the energy of the blue wing of the very prominent O VII emission line as well as negative residuals on its red wing. Central right panel: Same as central left panel, with the addition of the SWCX component (LHB-CGM-CXB-Coro-SWCX model). Bottom left panel: The addition of a significantly different energy shift applied to the best fit model of each camera reduces the residuals around the O VII emission line (shift-LHB-CGM-Coro-CXB). Bottom right panel: Same as bottom left panel, with the addition of the SWCX component (shift-LHB-CGM-CXB-Coro-SWCX model). |

|

Fig. 6 Best fit energy of the O VII and O VIII emission lines (top and bottom, respectively), as measured by the different cameras aboard eROSITA. The black and red symbols and the dotted lines show the best fit energies obtained by fitting e12 and e0 spectra of each TM camera and the average best fit energy, respectively. A scatter larger than the statistical uncertainties is observed during both e0 (ΔE ~ 3 eV) and e12 (ΔE ~ 5 eV). The horizontal dashed lines indicate the expected energy of the transitions (three for the O VII helium-like triplet). |

7.3 Is the Galactic corona in thermal equilibrium?

To investigate the thermal equilibrium of the plasma in the Galactic corona we substitute the APEC model for the Galactic corona with a recombining plasma model (RNEI model in XSPEC). This model reproduces the emission from plasma that was initially hot and then rapidly cooled on a timescale shorter than the one required to reach thermal equilibrium. As a consequence of the low densities characteristic of the Galactic corona, we might expect that this plasma might be out of thermal equilibrium. One possible scenario for this might be in the form of a hot outflow (or the rising part of a fountain) from the Galactic disk, which would maintain the Galactic corona constantly replenishing it with energy, plasma, metals, and energetic particles (Bregman 1980; Fraternali et al. 2015; Putman et al. 2012). In addition to solar abundances, we also assumed an initial plasma temperature of 1.2 keV to match the typical temperatures of the hot plasma in the Galactic disk, while we left the current plasma temperature (kTCoro) as a free parameter in the fits.

A significant improvement of the fit (Δχ2 = 15.8 and Δχ2 = 15.2 for the addition of one free parameter in the case of negligible and high SWCX contribution, respectively; F-test probability of 3 × 10−4; see Table 2) is observed once a recombining plasma model is used. Both panels of Fig. 7 show that the recombining plasma component is able to better reproduce the data leaving lower residuals in the ~1 keV band.

The best fit plasma temperatures are kTCoro = 0.49 ± 0.09 keV and kTCoro = 0.47 ± 0.09 keV in the case of negligible and high SWCX contribution, respectively, and therefore significantly higher than that of the circumgalactic medium. From the normalization of the coronal emission, we derive an emission measure of 0.9 ± 0.3 × 10−6 cm−6 kpc, which corresponds to an electron density of ne ~ 0.9 × 10−3 cm−3 for a depth of ~1 kpc. Assuming that the recombining plasma model is an accurate description of the coronal emission, the best fit provides us with an estimate of the ionization timescale which results in τ = (10.7 ± 3) and (9.9 ± 3) × 1010 s cm−3 in the case of negligible and high SWCX contribution, respectively (see Table 2). For an electron density of ne ~ 0.9 × 10−3 cm−3, this timescale would correspond to an ionization timescale of about ~4 Myr, which is longer than the timescale needed for an outflow originating from hot plasma (kT ~ 1 keV) in the Galactic disk and moving at the sound speed (υc ~ 500 km s−1) in an outflow replenishing the Galactic corona. Such hot plasma would be able to cover ~1 kpc in ~2 Myr, which seems in line with the observation that the coronal plasma is possibly out of thermal equilibrium.

Both panels of Fig. 7 show that, even at its peak, the emission from the Galactic corona is comparable to, but lower than, the instrumental background and a factor of ~2.5–3 times lower than the emission from the CXB. The relative weakness of the emission from the Galactic corona is in line with the fact that it has only recently been recognized (Das et al. 2019a,b, 2021) as a separate feature in addition to the Galactic halo component and different from the emission from dwarf M stars (Masui et al. 2009; Wulf et al. 2019).

|

Fig. 7 Same spectrum and color scheme as in Fig. 5. Left panel: Best fit result with a recombining plasma emission model (RNEI in XSPEC) for the Galactic corona (solid green) in addition to the components considered in the bottom left panel of Fig. 5 (shiſt-LHB-CGM-Coro2-CXB in Table 2). Right panel: Same as left panel, but with the addition of the SWCX component (shiſt-LHB-CGM-CXB-Coro2-SWCX model). |

8 Constraining the properties of the hot CGM

The eROSITA data allow us to place robust constraints on the physical properties of the CGM.

8.1 Temperature of the CGM constrained by the Ο VII and Ο VIII emission lines

For optically thin hot plasma in thermal equilibrium, the energy and intensity of the emission lines can be used as a powerful tool to estimate the temperature of the plasma, independently from the shape of the underlying continuum.

During e12, the best fit energy of the Ο VII line is  keV (black dotted line in Fig. 6), and therefore consistent with being dominated by the recombination line, as expected in the case of collisionally ionized plasma. On the other hand, the best fit energy of the Ο VII line is observed to shift to

keV (black dotted line in Fig. 6), and therefore consistent with being dominated by the recombination line, as expected in the case of collisionally ionized plasma. On the other hand, the best fit energy of the Ο VII line is observed to shift to  keV during eO (black dotted line in Fig. 6). We attribute this shift of the best fit energy to a larger contribution of the forbidden line, which is dominant in the SWCX component. Therefore, this corroborates the idea that the higher flux of the Ο VIII emission line during eO is produced by enhanced SWCX.

keV during eO (black dotted line in Fig. 6). We attribute this shift of the best fit energy to a larger contribution of the forbidden line, which is dominant in the SWCX component. Therefore, this corroborates the idea that the higher flux of the Ο VIII emission line during eO is produced by enhanced SWCX.

For the Ο VII line in the e0 spectrum, the statistical uncertainties are significantly smaller than the differences in energies (ΔE ~ 2–3 eV) measured by the different instruments. This confirms that the observed scatter is due to systematic uncertainties in the calibration of the energy scale of the different cameras aboard eROSITA.

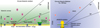

To measure the Ο VII G-ratio16 and the Ο VII-to-O VIII line ratio, we fitted the spectra of each TM with the same parametric model used in Sect. 7.2 (composed of a power law plus an apec component with no emission line); however, we substituted the four emission lines with six narrow emission lines with Gaussian profiles (three for the Ο VII triplet, plus C VI, Ο VIII, and the weaker line at ~O.423 keV, which reproduces the Ν VI triplet) with energies fixed at the expected values of each transition and shifted by a common value for each camera (produced by the VASHIFT component in XSPEC). To avoid degeneracy due to the fact that the lines of the Ο VII triplet cannot be separated at the CCD resolution of the eROSITA cameras (Predehl et al. 2021), we fixed the ratio of the forbidden to intercombination lines at 3.5, as expected for plasma at densities as low as those considered here. We expect that the combination of the C VI and Ο VIII lines will constrain the cross-calibration across the different cameras by determining the inter-camera shift of the energy scale. This will then allow us to estimate the G-ratio of the Ο VII triplet (Porquet & Dubau 2000; Porquet et al. 2001).

The black and red points in the top panel of Fig. 8 show the G-ratio of the Ο VII triplet in the e12 and eO spectra, respectively17. Because of the large error bars and scatter associated with the determination of the G-ratio, the top panel of Fig. 8 shows the y-axis in logarithmic scale. G-ratios as high as 20 are observed; however, these high values are characterized by very large uncertainties (Fig. 8). We compute the best fit G-ratio by performing a fit with a constant, which is equivalent to a weighted mean. In particular, we observe that during e12 a fit of the G-ratio observed by each camera provides the best fit value of  . It is well known that the G-ratio is a good temperature diagnostic (Porquet & Dubau 2000; Porquet et al. 2001). By comparing the measured G-value and its uncertainties (dashed lines in Fig. 9) with the expectations from the models of collisionally ionized plasma (black circles in Fig. 9), we obtain that the temperature of the plasma producing the Ο VII triplet must be higher than kT > 0.06 keV.

. It is well known that the G-ratio is a good temperature diagnostic (Porquet & Dubau 2000; Porquet et al. 2001). By comparing the measured G-value and its uncertainties (dashed lines in Fig. 9) with the expectations from the models of collisionally ionized plasma (black circles in Fig. 9), we obtain that the temperature of the plasma producing the Ο VII triplet must be higher than kT > 0.06 keV.

The bottom panel of Fig. 8 shows the ratio of the best fit intensities of the Ο VII to the Ο VIII lines, obtained by fitting the total spectrum. The fit of the ratio with a constant provides a best fit value of about 7.7 + 0.9. This line ratio is also a very sensitive temperature diagnostic tool. The red circles in Fig. 9 show the expected ratio as a function of the temperature of the plasma18, under the assumption that a single optically thin and collisionally ionized component is producing all of the flux from the Ο VII and Ο VIII lines. By comparing our measurement with the expected relation (see the dashed red lines in Fig. 9), we place a tighter constraint on the temperature of the plasma producing the Ο VII and Ο VIII lines of 0.152 < kT < 0.160 keV19.

The best fit temperature of the CGM component results to be kT = 0.157 + 0.004 keV, while it increases to kT = 0.173 + 0.005 keV for a high SWCX contribution. If the SWCX component provides a significant fraction of the O VII line, then the temperature estimate derived from the line ratio will be biased low.

Even though the statistical uncertainty on the measurement of the CGM temperature is as low as ~3%, we conclude that the systematic uncertainty induced by the uncertainty on the amplitude of the SWCX emission during e12 is as large as ~10%. In particular, assuming a larger contribution due to SWCX does result in a hotter CGM plasma (i.e., kT = 0.173 + 0.005 keV).

Finally, we estimate an upper limit to the soft X-ray line widths. After assuming that all six lines, which have been fitted, are broadened by the same amount, we measured an upper limit to the line widths of Δυ ≤ 500 km s−1.

|

Fig. 8 Best fit G-ratio (top) and Ο VII-to-O VIII emission line ratio (bottom), as observed by the different cameras. The same color scheme as in Fig. 6 is used. |

8.2 Determining the metal abundances of the hot CGM

We note that the best fit metal abundances of the CGM component is ZCGM = 0.068 + 0.004 Ζ⊙ and ZCGM = 0.058 + 0.006 Ζ⊙ for negligible and high SWCX contribution, respectively, which correspond to a statistical uncertainty on the order of ~5%. Such remarkable statistical accuracy is due to the fact that the CGM component produces both the soft X-ray emission lines as well as most of their underlying continuum. The systematic uncertainty on the metallicity induced by the poorly constrained SWCX contribution is only ~15%. In particular, the best fit with high SWCX contribution corresponds to lower abundances, in agreement with the fact that SWCX provides a larger contribution to the lines than to the continuum.

The best fit metal abundance appears to be remarkably low, with best fit values on the order of ZCGM ~ 0.06–0.07 Ζ⊙ for the Lodders (2003) abundances, regardless of the model employed (see Table 2). This is dictated by the low equivalent widths of the soft X-ray emission lines, such as O VII and Ο viii. Figures 5 and 7 both show that the thermal component associated with the emission of the CGM reproduces not only the bulk of the emission lines, but also the bulk of the soft X-ray continuum between these lines. In the next sections we investigate the order of magnitude of systematic uncertainties on the estimated abundances.

|

Fig. 9 G-ratio (left) and Ο VII-to-O VIII emission line ratio (right) as a function of plasma temperature. The black solid and dashed horizontal lines show the best fit and 1σ uncertainty on the G-ratio measured by fitting the lines of the O VII triplet from the e12 spectrum. The black filled dots and connecting line show the expected relation between the G-ratio and temperature, expected for collisionally ionized plasma in thermal equilibrium (obtained from the APEC model in Xspec). The measurement of the G-ratio implies that the temperature must be kT > 0.06 keV, if produced by a single plasma component in thermal equilibrium. The red solid and dashed horizontal line shows the best fit and 1σ uncertainty on the Ο VIII-to-O VII line ratio measured by fitting the e12 spectrum. The red filled dots and connecting line show the expected relation between Ο VIII-to-O VII line ratio and temperature, expected for collisionally ionized plasma in thermal equilibrium (obtained from the APEC model in Xspec). Under the assumption that a single optically thin and collisionally ionized component is producing both lines, the observed line ratio implies that the temperature must be within the range 0.152 < kT < 0.160 keV. The two completely independent estimates of the temperature are in agreement with each other, suggesting that the same plasma might produce the bulk of the O VII and Ο VIII emission. |

8.2.1 Impact of the CXB on the measured CGM abundances

As detailed in Sect. 6.2, the shape of the CXB is well known above ~ 1 keV, while significant uncertainties are related with its contribution below ~ 1 keV. To take into account the impact of these uncertainties on the determination of the metal abundances of the CGM component, we re-fitted the eFEDS spectrum substituting the CXB component first with its harder possible spectrum (CXBh; see Sect. 6.2).

The left columns of Table 3 show the best fit results once the CXB component is substituted with CXBh, for the case of negligible and high SWCX flux in the first and second column, respectively (Table 3). We observe, as a result of the introduction of the CXBh component, that the best fit CGM abundance drops significantly to values of ZCGM = 0.057 + 0.003 and ZCGM = 0.046 + 0.003 Ζ⊙ and the quality of the fit worsens (Δχ2 = −2.1 and −4.2 for the same degrees of freedom) in the case of negligible and high SWCX scenarios, respectively. This confirms the expectation that, if a smaller fraction of the soft X-ray continuum is produced by the CXB, then the CGM will be required to have lower metal abundances to produce the same lines and vice versa.

We then refitted the eFEDS spectrum substituting the CXB component with its softer possible spectrum (CXBs; see Sect. 6.2). Once the spectrum if fitted with this model, we observe that the normalization of the LHB component rises to high values (NLHB = 0.0041 + 0.0004 pc cm−6), which are inconsistent with those observed by ROSAT (NLHB ~ 0.0027 pc cm−6). If the LHB emission were so high, then it would predict a flux in the R1 and R2 ROSAT bands significantly larger than was observed. Therefore, we fix the normalization of the LHB to the value observed by ROSAT.

The central columns of Table 3 show the best fit results, once the CXB component is substituted with CXBs, for the case of negligible and high SWCX flux, respectively (Table 3). Again, the quality of the fit worsens (Δχ2 = −12.7 and −19.8 for one less degree of freedom); however, we observe that the best fit CGM abundance rises significantly to values of ZCGM = 0.093 ± 0.008 and ZCGM = 0.089 ± 0.009 Z⊙ in the case of negligible and high SWCX, respectively (Table 3). This suggests that CGM abundances as high as ZCGM = 0.1 Z⊙ are not excluded by the data if a soft CXB component is assumed. In particular, this exercise shows that, although the statistical uncertainty on the measurement of the CGM abundance is as small as ~5%, the uncertainty on the true contribution to the soft X-ray continuum of the CXB component induces a larger systematic uncertainty of ~70%. In fact, changing the assumptions on the shape of the CXB below ~1 keV, we measure an abundance within the range from Z = 0.046 ± 0.003 to Z = 0.093 ± 0.008 Z⊙.

Best fit parameters obtained by fitting the e12 spectrum with different models.

8.2.2 An additional non-thermal component to the soft X-ray diffuse emission?

An alternative option to recover larger metal abundances for the CGM would be to assume that a new hypothetical component would produce the bulk of the continuum in the ~0.3– 1 keV band. Such component shall not produce emission lines, therefore it must be non-thermal20. Additionally, such hypothetical component must be truly diffuse and be relevant only at low energies, providing a contribution smaller than ~10% of the CXB at energies above ~0.5 keV. Ultra-deep X-ray surveys with Chandra and XMM-Newton have resolved more than ~92% of the CXB in the 0.5–7 keV band (Luo et al. 2017).

To investigate such a possibility, we add a power-law component to the fit, which we assume to be absorbed by the full column density of absorbing Galactic material. Then, we fix the metal abundance of the CGM component to the significantly larger value of ZCGM = 0.3 Z⊙. Finally, we constrain the normalization of the LHB to be consistent with the value observed by ROSAT and the normalization of the CXB to lay within 10 % of its expected value (NCXB = 0.269 ph keV−1 cm−2 s−1 at 1 keV); therefore, it is constrained to lie within 0.242–0.296 ph keV−1 cm−2 s−1 at 1 keV. Both panels of Fig. 10 show that the addition of a steep power law can reproduce the bulk of the continuum emission in the soft X-ray band, therefore allowing the abundance of the CGM to be as high as ZCGM = 0.3 Z⊙. Furthermore, in the case of negligible and of high SWCX emission, the addition of the steep power law improves the fit by Δχ2 = 2.7 and 10.8, respectively, for the same degrees of freedom (see Table 3). The orange lines in both panels of Fig. 10 show the contribution from the hypothetical additional soft power-law component.

The best fit slope of the power law results to be extremely steep (Γ = 4.3 ± 0.3 and Γ = 4.8 ± 0.4, respectively). We observe that the main effect of this component is to try to mimic the emission of the continuum produced by the CGM component (bremsstrahlung plus recombination) in order to allow higher metal abundances of the CGM (Table 3).

The slope (Γ ~ 4.3–4.8) of this additional power law is too steep to be associated with a non-thermal phenomenon. Additionally, the lack of emission lines appears unlikely to be associated with a thermal phenomenon in the local Universe. Therefore, we conclude that either the CGM abundances are indeed as low as Z ~ 0.05–0.1 Z⊙ or this additional power law must be associated with a thermal component from the distant Universe21.

Filaments in the Universe as well as hot baryons in the outskirts of virialized regions are expected to have temperatures lower than 1 keV and to have low abundances Ζ ~ 0.05–0.1 Z⊙ (Roncarelli et al. 2012; Vazza et al. 2019). In theory, if filaments at different redshifts contributed to the soft X-ray emission, then the emission lines associated with the thermal spectra of the filaments would appear smeared out by the redshift distribution. Therefore, the resulting spectrum is expected to appear as a rather steep power law with slope of Γ ~ 1.5 and Γ ~ 3.8 at 0.3–0.8 and 0.8–2.0 keV, respectively (Roncarelli et al. 2012). Although the slope of the additional power law appears somewhat steeper than these values, we note the resemblance between the expected spectrum from the hot baryons in filaments at different redshifts and the power law observed here.

Roncarelli et al. (2012), after assuming different recipes for galactic winds and black hole feedback, estimated the surface brightness of the whole intergalactic medium (i.e., all the gas) and of only its warm-hot component. They find the surface brightness for the former and the latter to be ~3.1–24.5 × 10−13 erg cm−2 s−1 and ~0.9–3.2 ×10−13 erg cm−2 s−1, respectively, in the 0.5–2.0 keV band. Instead, in the 0.3–0.8 keV band they find a surface brightness of ~2.2û12.0 × 10−13 erg cm−2 s−1 deg−2 and ~ 1.0–3.3 × 10−13 erg cm−2 s−1 deg−2, respectively.

The observed surface brightness of the best fit additional power law is ~1.9–3.5 × 10−13 erg cm−2 s−1 deg−2, in the 0.6–2.0 keV band, in the case of high and negligible SWCX contribution, respectively. This is within the expected range of fluxes expected from the warm-hot intergalactic medium and, as expected, it is much fainter than the total intergalactic medium emission. The emission from galaxy clusters is already included in our fiducial CXB model (Gilli et al. 2007).

On the contrary, in the 0.3-0.8 keV band the observed surface brightness of the best fit power-law emission is ~7.6– 9.9 × 10−13 erg cm−2 s−1 deg−2, and therefore compatible with the highest estimates for the whole intergalactic medium and a factor of ~3–10 times higher than the surface brightness of only its warm-hot component. This indicates that either the contribution of clusters is underestimated in our fiducial CXB model or that the additional power law is physically not well justified and the CGM abundance is low. We note again that if all of the flux associated with the additional power-law component is associated with the warm-hot intergalactic medium, then it would be a lucky coincidence that the power law contributes to the total spectrum in such a way to reproduce the continuum of the CGM emission.

To conclude, it is most likely that the warm-hot intergalactic medium contributes to the soft X-ray background; however, to assess whether its contribution is strong enough to significantly affect the estimated CGM abundance, a self-consistent modelling of the contributions of the different components of the extragalactic CXB emission (i.e., AGN; galaxies; clusters; groups; warm-hot intergalactic medium) must be performed in a self-consistent way both in the data and in the simulations. Unfortunately, this is beyond the scope of the current work; however, this calls for a deeper understanding of the contribution of warm-hot intergalactic medium to the soft X-ray background.

|

Fig. 10 Same spectrum and color scheme as in Fig. 7. Left panel: Best fit model (shift-LHB-CGM-Coro2-CXB-PL in Table 3) after the inclusion of an additional non-thermal component (power law; shown with the orange solid line) to the same spectrum and model components shown in Fig. 7. Right panel: Same as left panel, but with the addition of the SWCX component (shift-LHB-CGM-Coro2-CXB-PL-SWCX model). |

8.2.3 Other biases on the observed CGM metal abundance

Early observations of non-virialized hot plasma have found somewhat lower abundances, compared with expectations, when fitted with a single temperature component (as done here). It is now recognized that plasma with a significant spread in temperature can obtain best fit values of the metal abundance that are biased toward lower values when fitted with single temperature models. In theory, this might also be a concern for the CGM of the Milky Way. On the other hand, the indication that the CGM temperature derived from the continuum, the oxygen line ratio, and the G-ratio of the O VII triplet agree with each other suggests that the spread in temperature of the CGM plasma might be small enough to induce only a small bias in the best fit metal abundances measured here. However, we leave the detailed investigation of this issue for future works.

We conclude that the best fit metal abundance of the CGM along the direction of the eFEDS field is ZCGM = 0.068 ± 0.004 (statistical), ZCGM = 0.052–0.072 Z⊙ once the systematic uncertainty on the contribution of the SWCX is considered, and ZCGM = 0.04-0.10 Z⊙ once the systematic uncertainties on the extrapolation of the CXB at low energy are also folded in. We also note that the abundances can be as high as ZCGM = 0.3 Z⊙ if the warm-hot intergalactic medium provides a contribution with a flux of 9.9 × 10−13 erg cm−2 s−1 deg−2 to the soft X-ray background in the 0.3–0.6 keV band.

|

Fig. 11 Oversimplified schematic view of the different components of the diffuse emission along the line of sight toward the eFEDS field. Left panel: Galactic disk (in yellow) with a scale height of ~100 pc. Energetic activity in the disk (yellow stars) generates copious amounts of hot plasma, which (when confined to the disk) inflates bubbles, super-bubbles (blue circles), forming features similar to the LHB (red circle). Sometimes the energetic activity has enough power to produce an outflow that breaks free into the Galactic corona, forming chimneys or fountains. Therefore, this process releases hot plasma, energy, metals, and particles that energize and sustain the Galactic corona. Within the corona the intermediate and high velocity clouds (IVC and HVC, respectively) are observed, composed primarily of atomic hydrogen (red ellipses). It is likely that the intermediate velocity HI clouds represent the other phase of a cycle where hot material is expelled from the disk to then come back as cold gas. Right panel: Extent of the virial radius of the Milky Way (blue sphere), which is a proxy for the extent of the CGM, compared with the extent of the Galactic disk (assumed here to have a diameter of 40 kpc). The Galactic corona (green) is depicted above and below the Galactic disk and within it the IVC (red ellipses), while within the CGM the very high velocity clouds (VHVC) are represented (red ellipses). The yellow bipolar ellipses at the center of the disk represent the eROSITA bubbles. |

9 Discussion

After removing the periods affected by emission from SWCX (during e0 and e3) and performing simplifying assumptions on the level of SWCX contamination during e12, we fitted the integrated X-ray emission observed by eROSITA in the eFEDS field with a combination of four components: the unabsorbed emission from the LHB; the CXB; the CGM; and the Galactic corona. We note that the presence of the Galactic corona, in addition to the CGM component, is indeed strictly required by the eROSITA data. Additionally, we tested the impact on our best fit results induced by a non-negligible SWCX flux during e12. This decomposition of the soft X-ray background is the first step toward the development of a comprehensive galaxy-CGM-corona model (Fig. 11). In particular, a schematic picture of this interaction is discussed in Sect. 9.6.

The mean surface brightness observed by eROSITA in the eFEDS field in the total (0.3û2 keV), the soft (0.3– 0.6 keV), and the medium (0.6–2 keV) bands is 12.6 × 10−12 erg cm−2 s−1 deg−2, 5.1 × 10−12 erg cm−2 s−1 deg−2, and 7.5 × 10−12 erg cm−2 s−1 deg−2, respectively (Table 4).

9.1 Is a contribution due to SWCX emission during e12 required?

When comparing the best fit models with the assumption of negligible and high SWCX fluxes, we note that the former provide significantly better fits (Δχ2 = 33.6 for the same degrees of freedom; see Table 2). However, the detailed comparison of the residuals shows that the highest deviations occur in the softer band, below ~0.35 keV, where a non-negligible contribution due to the electronic noise of the eROSITA cameras is possible. Therefore, we do not think that this evidence can be considered a demonstration that the SWCX emission must be negligible during e12. Instead, we leave this measurement for future works (which will better address the contribution of electronic noise and of the time variations of SWCX; Dennerl et al., in prep., Yeung et al. 2023).

9.2 Composition of the observed background and CXB resolved fractions

The emission in the 0.6–2 keV band is dominated by the CXB component, which alone composes more than > 83% of the flux, both in the case of negligible and high SWXC contribution. The remaining emission is due to the Galactic corona, which produces about ~8–9% of the flux, and the CGM, which contributes ~6–7% of the total. This is consistent with the fact that about ~81% of the flux in the 0.5–2 keV band has been resolved into discrete sources thanks to ultra-deep surveys with Chandra and XMM-Newton (Luo et al. 2017). Additionally, this suggests that the majority of the remaining X-ray flux (~15%) is truly diffuse and is likely due to the emission from the CGM and the Galactic corona22. However, we expect that the fractional contribution due to the Galactic emission varies greatly with Galactic latitude. In particular, we expect that the emission from the Galactic corona drops significantly at higher Galactic latitudes (see Locatelli et al., in prep.).

We note that most of the ultra-deep surveys were carried out at high Galactic latitudes (b > 50°). Therefore, we expect that the contribution from the Galactic corona might be smaller than the amount observed in the eFEDS field (~9%) along the lines of sight investigated in such ultra-deep fields (Brandt & Yang 2022).