| Issue |

A&A

Volume 648, April 2021

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A31 | |

| Number of page(s) | 18 | |

| Section | Extragalactic astronomy | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202039803 | |

| Published online | 07 April 2021 | |

A blind ATCA HI survey of the Fornax galaxy cluster

Properties of the HI detections

1

INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Cagliari, Via della Scienza 5, 09047 Selargius, CA, Italy

e-mail: alessandro.loni@inaf.it

2

Dipartimento di Fisica, Universitá di Cagliari, Cittadella Universitaria, 09042 Monserrato, Italy

3

International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR), The University of Western Australia, 35 Stirling Hwy, Crawley, WA 6009, Australia

4

ARC Centre of Excellence for All-Sky Astrophysics in 3 Dimensions (ASTRO3D), Australia

5

CSIRO Astronomy and Space Science, Australia Telescope National Facility, PO Box 76 Epping, NSW 1710, Australia

6

Department of Astronomy, University of Cape Town, Private Bag X3, Rondebosch 7701, South Africa

7

School of Physics and Astronomy, Cardiff University, Queens Buildings The Parade, Cardiff CF24 3AA, UK

8

INAF-Astronomical observatory of Capodimonte, via Moiariello 16, Naples 80131, Italy

9

Kapteyn Astronomical Institute, University of Groningen, PO Box 800 9700 AV Groningen, The Netherlands

10

Australian Research Council, Centre of Excellence for All-sky Astrophysics (CAASTRO), Australia

11

Department of Physics and Electronics, Rhodes University, PO Box 94, Makhanda 6140, South Africa

Received:

30

October

2020

Accepted:

26

January

2021

We present the first interferometric blind HI survey of the Fornax galaxy cluster, which covers an area of 15 deg2 out to the cluster virial radius. The survey has a spatial and velocity resolution of 67″ × 95″(∼6 × 9 kpc at the Fornax cluster distance of 20 Mpc) and 6.6 km s−1 and a 3σ sensitivity of NHI ∼ 2 × 1019 cm−2 and MHI ∼ 2 × 107 M⊙, respectively. We detect 16 galaxies out of roughly 200 spectroscopically confirmed Fornax cluster members. The detections cover about three orders of magnitude in HI mass, from 8 × 106 to 1.5 × 1010 M⊙. They avoid the central, virialised region of the cluster both on the sky and in projected phase-space, showing that they are recent arrivals and that, in Fornax, HI is lost within a crossing time, ∼2 Gyr. Half of these galaxies exhibit a disturbed HI morphology, including several cases of asymmetries, tails, offsets between HI and optical centres, and a case of a truncated HI disc. This suggests that these recent arrivals have been interacting with other galaxies, the large-scale potential or the intergalactic medium, within or on their way to Fornax. As a whole, our Fornax HI detections are HI-poorer and form stars at a lower rate than non-cluster galaxies in the same M⋆ range. This is particularly evident at M⋆ ≲ 109 M⊙, indicating that low mass galaxies are more strongly affected throughout their infall towards the cluster. The MHI/M⋆ ratio of Fornax galaxies is comparable to that in the Virgo cluster. At fixed M⋆, our HI detections follow the non-cluster relation between MHI and the star formation rate, and we argue that this implies that thus far they have lost their HI on a timescale ≳1−2 Gyr. Deeper inside the cluster HI removal is likely to proceed faster, as confirmed by a population of HI-undetected but H2-detected star-forming galaxies. Overall, based on ALMA data, we find a large scatter in H2-to-HI mass ratio, with several galaxies showing an unusually high ratio that is probably caused by faster HI removal. Finally, we identify an HI-rich subgroup of possible interacting galaxies dominated by NGC 1365, where pre-processing is likely to have taken place.

Key words: galaxies: clusters: general / galaxies: evolution / galaxies: ISM

© ESO 2021

1. Introduction

It is known that the evolution of galaxies is faster in denser environments (Diaferio et al. 2001) and that, as a consequence, the relative abundance of red early-type galaxies and blue late-type galaxies changes with environment density (Hubble & Humason 1931; Oemler 1974; Dressler 1980). In this context, galaxy clusters are the most extreme environments within which galaxies evolve. They are characterised by a high number density of galaxies and by the presence of a dense intra-cluster medium (ICM), which galaxies move through. Thus, in clusters, both hydrodynamical and gravitational interactions such as ram-pressure stripping and tidal interactions, respectively, are likely to happen (Gunn et al. 1972; Toomre & Toomre 1972), as well as mergers between galaxies (at least in the cluster outskirts – Sheen et al. 2012; Oh et al. 2018). These interactions deplete the cold gas reservoirs of galaxies and, therefore, affect their star formation activity. The balance between these types of interactions depends both on galaxy properties – including their orbits – and on cluster properties, such as the number density of galaxies and the ICM density. Therefore, we expect galaxy evolution to proceed differently in different clusters.

The aim of this work is to study galaxy evolution in the Fornax cluster, which is a low mass cluster (7 × 1013 M⊙ within a radius of 1.4 Mpc – twice the virial radius, Rvir; Drinkwater et al. 2001a), located in the southern sky at a distance of 20 Mpc (Blakeslee et al. 2009). Fornax is thus the second closest galaxy cluster to us after Virgo. Fornax has roughly 200 spectroscopically confirmed galaxies within Rvir ∼ 700 kpc (Maddox et al. 2019). NGC 1399 is the central dominant galaxy, which coincides with the peak of the X-ray emission (Paolillo et al. 2002), and the majority of the massive galaxies in the cluster central region are of an early morphological type. Thus, Fornax shows a more dynamically evolved state than Virgo (Grillmair et al. 1994; Jordán et al. 2007), but its growth is not over at all.

The Fornax region includes two main substructures (Drinkwater et al. 2001a). The first is the cluster itself centred on NGC 1399, whose interaction with NGC 1404 is revealed by a perturbed ICM distribution (e.g., Sheardown et al. 2018). Here, three well defined groups of galaxies with different light and colour distributions, kinematics, and stellar populations were found by combining the Fornax Deep Survey imaging (Iodice et al. 2019a) with Fornax 3D spectroscopy (Iodice et al. 2019b) in the two-dimensional projected phase space: the core, the north-south clump and the infalling galaxies (see Fig. 7 in Iodice et al. 2019b). The core is still dominated by NGC 1399, which is one of only two slow-rotators inside the virial radius (NGC 1427 is the other one, located on the east side of the cluster). The NS-clump is located in the high-density region of the cluster (within 0.4Rvir ∼ 0.3 Mpc in projection), where the X-ray emission is still bright. It hosts the reddest and most metal-rich galaxies, all of them fast-rotating early-type galaxies. The bulk of the gravitational interactions between Fornax galaxies as well as most of the intra-cluster baryons (i.e. diffuse light, globular clusters and planetary nebulae) (Cantiello et al. 2018; Spiniello et al. 2018; Iodice et al. 2019a) are found in this NS clump, where galaxy growth is still ongoing through the accretion of mass onto galaxies’ outer regions (Spavone et al. 2020). The third group of objects in the cluster includes the infalling galaxies, which are distributed nearly symmetrically around the core in the low-density region outside ∼0.4 Rvir ∼ 0.3 Mpc in projection. The majority of these galaxies are late-types with ongoing star formation. Most of them exhibit signs of interaction with the environment and/or minor mergers in the form of tidal tails and disturbed molecular gas (Zabel et al. 2019; Raj et al. 2019). Previous works had also shown that numerous dwarf galaxies are currently falling into the centre of the cluster (Drinkwater et al. 2001b; Schröder et al. 2001; Waugh et al. 2002). Finally, the other major structure in the Fornax volume is the infalling group centred on NGC 1316 (Fornax A), located ∼1.5 Mpc south-west of the cluster centre and experiencing ongoing interactions between its members (Schweizer 1980; Horellou et al. 2001; Iodice et al. 2017; Serra et al. 2019).

The observation of galaxies’ atomic hydrogen through the 21 cm wavelength emission line (HI) gives us information on the evolutionary state of galaxies as well as a global picture of the cluster. The evolution of galaxies depends on the evolution of their atomic hydrogen reservoir, which is the primary reservoir of fuel for star formation. Since it typically extends to the outskirts of galaxies, HI gas is the first component that is affected by tidal interactions, ram-pressure stripping and mergers. Indeed, cluster galaxies are usually deficient in atomic hydrogen with respect to non-cluster galaxies (Giovanelli & Haynes 1983; Haynes & Giovanelli 1986; Boselli & Gavazzi 2006). HI is, therefore, a crucial observable for understanding galaxy evolution in dense environments (Hughes & Cortese 2009; Chung et al. 2009).

HI emission in the Fornax cluster was studied in several works. Bureau et al. (1996) used the Parkes radio telescope to measure the amount of atomic hydrogen in 21 undisturbed galaxies with morphologies S0/a or later, located within 6 deg from NGC 1399 and with cz ≤ 2520 km s−1. The eight galaxies within Rvir did not show any peculiar value in the MHI/I−band infrared luminosity ratio with respect to the rest of the sample. The same ratio evaluated for Ursa Major galaxies, a lower density environment than Fornax, led them to conclude that the observed Fornax galaxies are not HI deficient.

The first blind HI survey of Fornax was carried out by Barnes et al. (1997), also with the Parkes telescope. They detected HI in eight galaxies within an area of 8 × 8 deg2. Of those, two galaxies are within the cluster Rvir: ESO 358G-063 and NGC 1365. Thanks to the survey sensitivity, they excluded the existence of a significant population of optically undetected HI clouds with HI mass greater than 108 M⊙.

The number of HI detections within the Fornax central region increased with the targeted survey by Schröder et al. (2001). They found HI in 37 out of 66 galaxies. Of those, 14 are within Rvir, while the rest lies within 5 deg from the centre of the cluster. They found a lack of HI in the cluster centre, and measured the HI deficiency parameter to be 0.38 ± 0.09 (as defined in Solanes et al. 1996). This shows a modest HI depletion in Fornax (usually, galaxies with HI deficiency parameter > 0.3 are considered to be HI deficient, e.g., Dressler 1986; Solanes et al. 2001). Furthermore, the MHI−to−blue light ratio of Fornax galaxies – mean value (0.68 ± 0.15)M⊙/L⊙ – is a factor 1.7 lower than in the field. They also showed that the velocity dispersion of the sample of HI deficient galaxies is lower than that of the remaining HI detected galaxies. This difference in velocity dispersion agrees with the deficient galaxies having more radial orbits (as shown in Dressler 1986), which makes them good candidates for ram-pressure stripping (as discussed in Solanes et al. 2001).

Waugh et al. (2002) presented a blind survey of Fornax based on the HI Parkes All Sky Survey (HIPASS − Barnes et al. 2001) data with a MHI limit of 1.4 × 108 M⊙. They detected 110 galaxies within an area of ∼620 deg2 around the cluster. Of those, nine HI detections are within Rvir. The authors confirmed a HI depletion in the HI detections (all late types) near the centre of the cluster, and suggested that HI-rich galaxies detected in the outer parts of the cluster are infalling towards the cluster for the first time. HI detections are arranged in a large scale sheet-like structure with a negative velocity gradient from south-east to north-west.

Waugh (2005) presented the result of the deepest blind HI survey of the cluster so far: the Basketweave survey of Fornax carried out with the Parkes telescope. This survey used a new scanning technique, which improved the sampling and the noise level compared to HIPASS. HI was detected in 53 galaxies within 100 deg2 down to a detection limit of 108 M⊙. Of those, 15 were new detections, which confirmed the results of Waugh et al. (2002). In addition, the author presented higher resolution HI observations (2 arcmin, 3.3 km s−1) of 28 individual Fornax galaxies carried out with the Australia Telescope Compact Array (ATCA). Of those, six are within Rvir. Within this region, ESO LV-3580611 was marked as having an intriguing HI morphology with an elongation to the north-east of the system. As suggested in Schröder et al. (2001), also Waugh (2005) pointed out that this galaxy may be moving towards us.

The only other Fornax galaxy within Rvir with resolved HI imaging is NGC 1365 (van der Hulst et al. 1983; Jorsater & van Moorsel 1995). The latter study observed an elongated HI distribution to the west of the system. They suggested that it may be caused by the interaction with the ICM.

All previous blind HI surveys of Fornax were carried out with the Parkes telescope. Their angular resolution of 15 arcmin was insufficient to study the HI morphology of the detected galaxies, which is a powerful tracer of environmental effects. Better angular resolution was achieved with the interferometric observation of a few selected galaxies in Fornax (see references above), but those observations covered only a small portion of the cluster volume. Here we present the first, blind, interferometric HI survey of the Fornax cluster.

Our survey was carried out with the ATCA and covers an area of 15 deg2 centred on NGC 1399 with a spatial and velocity resolution of 67″ × 95″(∼6 × 9 kpc at a distance of 20 Mpc) and 6.6 km s−1, respectively. The average column density sensitivity within the survey area is 2 × 1019 cm−2 (3σ over 25 km s−1) and the MHI sensitivity is 2 × 107 M⊙ (3σ over 100 km s−1). Initially, a case study by Lee-Waddell et al. (2018) revealed the tidal origin of NGC 1427A using spatially resolved HI images from a subregion of our ATCA mosaic. Here we present the results of the full survey. In Sect. 2 we describe observations and data reduction. In Sect. 3 we present the HI detections, their HI images and spectra. We also compare their HI mass, H2 mass and SFR relative to non-cluster control samples, and compare their spatial and velocity distribution with those of the general Fornax population. In Sect. 4 we discuss our results, which we then summarise in Sect. 5. We include supplementary material on each galaxy in Appendix A.

2. ATCA observations and data reduction

Our blind Fornax survey covers an area of 15 deg2 (defined at a sensitivity level 3× higher than in the best region of the HI cube), spanning from the centre of the cluster to a distance slightly further than Rvir. The observations were carried out with the ATCA in the 750B configuration, from December 2013 to January 2014 (project code C2894)1. The cluster was observed for 336 hrs using 756 different pointings with a spacing of 8.6 arcmin (1/4 of the primary beam FWHM at 1.4 GHz)

The 64 MHz bandwidth, centred at 1396 MHz, was divided into 2048 channels, providing a velocity resolution of 6.6 km s−1. We reduced the data using the MIRIAD software (Sault et al. 1995). PKS B1934-638 and PKS 0332-403 were chosen as the bandpass calibrator and the phase calibrator, respectively. The latter was observed at 1.5 hr intervals between on-source scans. We flagged strong radio frequency interference based on Stokes V visibilities. After flagging and calibration we further processed a restricted frequency range 1407.2 MHz – 1419.6 (which corresponds to the velocity range of 166–2783 km s−1), which includes all spectroscopically confirmed Fornax galaxies (Maddox et al. 2019). Within this range we used the UVLIN task of MIRIAD to fit and subtract continuum emission using 2nd-order polynomials.

We obtained the dirty cube with the INVERT task using natural weights to maximise surface-brightness sensitivity. We used MOSMEM and RESTOR to clean and restore HI emission, respectively. The restoring Gaussian PSF has a major and minor axis full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 95 and 67 arcsec, respectively, and a position angle of 0.4 deg. The root mean square (RMS) noise level of the final cube goes down to 2.0 mJy beam−1 in the most sensitive region. Within the survey area the RMS noise is ≤6.0 mJy beam−1 and, on average, 2.8 mJy beam−1. This corresponds to a 3σ HI column density sensitivity of NHI ∼ 2 × 1019 cm−2 assuming a line width of 25 km s−1 and a 3σMHI sensitivity of ∼2 × 107 M⊙ over a linewidth of 100 km s−1. We searched for HI sources with the SoFiA source-finding package (Serra et al. 2015) within the survey footprint (see the green outline in Fig. 1). By smoothing and clipping, we convolve the input cube with a set of kernels and detect emission above 3.5σ of the local noise level of each kernel. Reliable detections are identified based on the reliability algorithm presented in Serra et al. (2012), which assumes that true sources have positive total flux and that the noise is symmetric around 0. For one faint source, NGC 1436, visual inspection was necessary to improve the SoFiA detection mask used to estimate galaxy parameters. Lastly, our final list of HI detections includes a faint source which did not pass the reliability test, but which we consider a genuine detection given its spatial correspondence with the known optical source FCC 323.

|

Fig. 1. Layout and detections of our ATCA HI survey. The green outline includes the 15-deg2 region where the average noise is 2.8 mJy beam−1 (see Sect. 2). The red contours represent the lowest reliable HI column density – 3σ over 25 km s−1 – of our 16 detections. The grey dashed circle is Rvir. The background optical image comes from the Digital Sky Survey (blue band). The yellow contours show the X-ray emission in the Fornax cluster detected with XMM-Newton (Frank et al. 2013) and convolved with a 3 arcmin FWHM gaussian kernel. These contours are spaced by a factor of 2, with the lowest level at 3.7 counts deg−2 s−1. |

3. H I detections in the Fornax cluster

3.1. H I detection properties

We detect HI in the 16 galaxies listed in Table 1. Of these, three are new HI detections: FCC 090, FCC 102, FCC 323. The last is the only galaxy with no previous redshift measurement. In Fig. 1 we show the location of our HI detections on the sky and in Fig. 2 we show the HI morphology of each galaxy. In these figures, red and white contours, respectively, represent the lowest reliable HI column density contour, defined as 3 times the local RMS assuming a typical HI linewidth of ∼25 km s−1 (see Table 1 and top-right corner of each panel in Fig. 2).

|

Fig. 2. ATCA HI contours overlaid on an optical image for all our HI detections, sorted according to increasing HI mass. The g-band optical images come from the Fornax Deep Survey (Iodice et al. 2016; Venhola et al. 2018; Peletier et al. 2020) for all galaxies except FCC 323, whose g-band optical image comes from the DESI Legacy Imaging Surveys, DR8 release (Dey et al. 2019). In each panel we show the 3σ column density sensitivity – values reported in the top right corner – with white colour, while cyan contours represent steps of 3n from it (n = 0, 1, 2, …). We show the PSF on the bottom-left corner of each panel, and a 5 kpc scale bar in the bottom-right corner. |

Parameters on the HI detected galaxies.

Figure 3 shows the integrated ATCA HI spectra of our 16 detections. We calculated the error bars by summing in quadrature the statistical uncertainty − derived from the local RMS (Table 1) and the number of independent pixels detected in each channel − and the flux-scale uncertainty. We find the latter to be ±20% based on the flux ratio calculated for a sample of selected bright point sources between our radio continuum image and the Northern VLA Sky Survey (Condon et al. 1998).

|

Fig. 3. Integrated HI spectra of our Fornax HI detections (in red) sorted according to increasing HI mass as in Fig. 2. We compare our spectra to spectra from the literature (shown in black; see top-left corner for details). We also show the barycentric velocity obtained from our HI spectra (vertical red line) and from optical spectra (vertical blue line; Maddox et al. 2019). |

We compare our spectra to those obtained from previous observations. In particular, we use HIPASS spectra from the BGC catalogue (Koribalski et al. 2004) or HIPASS data reprocessed by us. Since HIPASS data do not show any emission at the position of NGC 1436 and ESO 358-G016, we used Green Bank Telescope data (GBT – Courtois et al. 2009) and Parkes data (Bureau et al. 1996) as comparison, respectively. On the other hand, HIPASS spectra of ESO 358-G015 and ESO 358-G051 are noisy, so we used comparison spectra from Matthews et al. (1998) and Theureau et al. (1998), respectively, based on Nanacy data. Furthermore the literature spectra of ESO 358-G015 and ESO 358-G016 were rebinned to our ATCA channel-width. For consistency, we calculated the uncertainties in the comparison spectra by combining the noise in the spectrum and the flux-scale uncertainty of each survey, except for ESO 358-G016 for which the flux-scale uncertainty was not provided. For this galaxy, the error bars are shown as the RMS of the spectrum. In each panel of Fig. 3 we also show the velocity vopt derived from optical spectroscopy (Maddox et al. 2019) and the barycentric HI velocity vHI derived from our ATCA spectra.

We estimated the HI mass (MHI) of our detections from the integrated HI flux using Eq. (50) in Meyer et al. (2017) and adopting the same distance of 20 Mpc for all galaxies (Mould et al. 2000). The uncertainty on MHI is obtained from the error bars of the spectrum (Fig. 3). We report HI fluxes and masses in Table 1. Our HI fluxes agree with those in the literature within 1σ for nine out of 13 galaxies, and within 2σ for 11 of them. The two cases with a discrepancy larger than 2.5σ are NGC 1436 and ESO 358-G051. The comparison spectrum for NGC 1436 comes from GBT data (Courtois et al. 2009) and shows that we are most likely missing HI flux from the blue-shifted part of the system. For this galaxy, the total HI flux recovered by ATCA is lower than the GBT flux by 2.5σ (corresponding to a factor of 2.8). The reason of this discrepancy arises from a combination of low S/N and the presence, in at least some of the blue-shifted channels, of artefacts in this part of the ATCA cube. The case of ESO 358-G051 is less clear since the ATCA cube does not show any obvious artefacts and the galaxy well detected. However the total HI flux recovered by ATCA is lower than the Nancay flux by 3σ. Based on the current data it is possible that some of the emission is spread over multiple ATCA beams and therefore is too weak to be detected. Future MeerKAT data will clarify this issue Serra et al. (2016). Finally, the HI mass of FCC 323 is below the typical sensitivity of our data quoted in Sect. 2 because of the narrow linewidth as well as the low value of the local noise (Table 1). Our detections cover about three of magnitude in MHI, from FCC 323 (MHI = 8 × 106 M⊙) to NGC 1365 (MHI = 1.5 × 1010 M⊙). Figure 4 shows the cumulative histogram of the HI masses of our sample. A future study will analyse the HI mass function inferred from our data.

|

Fig. 4. Cumulative histogram of the ATCA HI masses of our Fornax sample. |

Due to the improved resolution of ATCA over a single dish, we detected, in half of the sample, a variety of HI morphologies (see Fig. 2) including offsets between optical and HI centres, truncated discs, asymmetries and HI tails, which we describe in this section and in Appendix A, following the same order in which galaxies are shown in Fig. 2 (from the lowest to the highest HI mass): the HI distribution in FCC 102 is offset with respect to the optical centre towards the north. We also notice a large difference between vopt and vHI, ∼100 km s−1. However, this is consistent with the large uncertainty on vopt given that the latter was measured from absorption lines for this galaxy (Natasha Maddox, priv. comm.); the HI peak of FCC 090 corresponds to the optical centre but the HI distribution has an elongation to the south; HI in ESO-LV 3580611 (FCC 306) is more extended to the north although there is no offset between optical and HI centre (Waugh 2005); the HI morphology of NGC 1437B (FCC 308) is asymmetric and more extended to the south; HI in NGC 1351A (FCC 067) shows an elongation towards the south; the HI of ESO 358-G063 (FCC 312) is more extended to the east side of the disc and the HI contours appear to be compressed on the west side; In NGC 1427A (FCC 235), we detected a HI tail which points to the south-east, away from the cluster centre, consistent with the tidal origin of this galaxy discussed in Lee-Waddell et al. (2018); the HI distribution in NGC 1365 (FCC 121) is extended to the north and appears to be compressed in the south-west part of the disc (see also Jorsater & van Moorsel 1995). We mark these HI disturbed galaxies with star markers in all subsequent figures.

The remaining half of the galaxies are either unresolved (or nearly so) and centred on the stellar body, or do not show noticeable asymmetries. One of them hosts a HI disc unusually truncated within the stellar disc, NGC 1436. This case will be discussed in detail in later sections.

A final case worth commenting on is FCC 120. This galaxy has been detected with Parkes and the spectrum in Schröder et al. (2001) shows an evident double horn profile that is ∼100 km s−1 wide, while we detect a single-peak profile (within the uncertainties – see Fig. 3). Careful visual inspection of our HI cube did not reveal any HI emission missing from our SoFiA detection mask. The regular HI morphology of this galaxy in Fig. 2 and the good agreement between vHI and vopt in Fig. 3 suggest that our HI characterisation of this galaxy is correct. Future, deeper data from the Meerkat Fornax survey may confirm this (Serra et al. 2016).

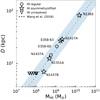

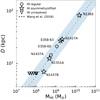

We estimated the HI size for all our resolved HI detections using the method of Wang et al. (2016) from the HI intensity maps of our galaxies. We considered a galaxy resolved if its surface brightness profile deviates from the shape of the point-spread function. We measured the HI diameter where the surface density is 1 M⊙ pc−2 and is then deconvolved with the HI beam. In Fig. 5 we show that both disturbed and regular galaxies follow the HI size-mass scaling relation of Wang et al. (2016) within the 3σ scatter. This can be understood as asymmetric HI features usually have a low surface brightness and do not significantly contribute to the total MHI of galaxies. In Fig. 5 we also show the HI unresolved galaxies. The upper limit on their size were set equal to the ATCA beam minor axis.

|

Fig. 5. HI disc size as a function of ATCA MHI for our resolved HI detections. Dashed line and the blue shaded area show the scaling relation and 3σ scatter respectively in Wang et al. (2016). |

3.2. MHI to M⋆ ratio

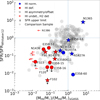

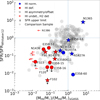

Given the abundant (albeit subtle) HI asymmetries and offsets in our Fornax sample, which might be tracing environmental interactions within or on their way to the Fornax cluster (whether with other galaxies, the large-scale potential or the intergalactic medium), we study the amount of HI in these galaxies in search of signs of HI depletion. In order to do so, we evaluated the ratio between MHI and stellar mass (M⋆) for each galaxy in our sample. The M⋆ values are derived using the WISE W1 (3.4 μm) in-band luminosity, W1–W2 colour and the prescription given by Cluver et al. (2014), with the custom photometry further defined in Jarrett et al. (2019), and assuming a common distance of 20 Mpc for all galaxies. We show the distribution of our sample on the MHI/M⋆ vs. M⋆ plane in Fig. 6.

|

Fig. 6. MHI to M⋆ ratio as a function of M⋆. Fornax galaxies (red+blue markers) are compared with non-cluster galaxies from VSG+HRS (grey circles). Red and blue colours show Fornax HI deficient and normal galaxies, respectively. We show Fornax galaxies with a distorted HI morphology with star-shaped markers (see Sect. 3). We show with a black solid line the xGASS scaling relation. The black dashed line is the linear extrapolation of this trend for M⋆ < 1.4 × 109 M⊙. The orange dashed line shows the ATCA average sensitivity evaluated as 3 × 2.8 mJy beam−1 with a linewidth of 100 km s−1. The vertical dashed line at 3 × 109 M⊙ separates low- from high-mass galaxies. |

We compare galaxies in Fornax with a sample consisting of void galaxies from the Void Galaxy Survey (VGS – Kreckel et al. 2012) and field galaxies from the Herschel Reference Survey (HRS – Boselli et al. 2014). We also used the xGASS M⋆-MHI/M⋆ scaling relation, which shows the weighted median of log10(MHI/M⋆) as a function of M⋆. This was obtained from 1177 galaxies selected only by stellar mass (M⋆ = 109 − 1011.5 M⊙) and redshift (0.01 < z < 0.05; Catinella et al. 2018). In Fig. 6 we extrapolate the xGASS trend down to 107 M⊙ (black dashed line) and show that it is consistent with the non-cluster sample of galaxies.

Our sample of Fornax HI detections appears to be systematically offset with respect to our VGS+HRS comparison sample and to the xGASS scaling relation. A two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test on the distribution of offsets from the xGASS scaling relation rejects the null hypothesis that Fornax and VGS+HRS galaxies are drawn from the same parent sample (p-value = 0.004, KS statistic = 0.43). Indeed, ten out of 16 Fornax galaxies are below or at the lower edge of the distribution of non-cluster galaxies. Their offset from the xGASS scaling relation is larger than the RMS deviation of VGS+HRS galaxies from it, thus indicating HI deficiency. For illustrative purposes we henceforth label these HI deficient galaxies in red colours in Fig. 6 and in all other upcoming figures in this paper.

HI deficiencies measured from plots like our Fig. 6 should be taken with caution because of the large MHI scatter at fixed M⋆ (e.g., Maddox et al. 2015). This scatter is to first order driven by Hubble type or, equivalently, by galaxy properties that correlate with Hubble type, such as the star formation rate (SFR). For this reason, in Sect. 3.3 we further analyse how the HI deficiency at fixed M⋆ relates to the H2 and SFR of these galaxies. Furthermore, in the present section we estimate HI deficiencies as proposed by Haynes & Giovanelli (1984) and recently revisited by Jones et al. (2018), where the measured MHI is compared with an expected MHI calculated based on galaxies optical size and Hubble type. For this purpose, we use the coefficients summarised by Boselli & Gavazzi (2009) and originally given in Haynes & Giovanelli (1984), Solanes et al. (1996), Boselli & Gavazzi (2009), and adopt the optical sizes and Hubble types listed in Table 1 for our galaxies. Figure 7 shows the comparison between the expected and the measured MHI. The dashed line, a factor of 3 below the 1:1 relation, is the typical threshold below which galaxies are considered HI deficient using the Haynes & Giovanelli’s (1984) method (e.g., Cortese et al. 2011). Also in this case, Fornax galaxies appear offset towards lower HI masses and there is a good match between galaxies labelled as HI deficient based on our Fig. 6 and those below the dashed line in Fig. 7.

|

Fig. 7. Expected MHI versus measured MHI. The former were evaluated with the Haynes & Giovanelli’s (1984) method with the coefficient summarised by Boselli & Gavazzi (2009). The latter are the ATCA MHI calculated as described in Sect. 3.1. The dashed line, a factor of 3 below the 1:1 relation, shows the typical threshold below which galaxies are considered deficient. |

From these figures, we see that not all galaxies with a disturbed HI morphology are HI deficient. Thus, HI morphological disturbances, whatever their exact nature (e.g., tidal or hydrodynamical, which is difficult to establish with the current data), allow us to identify cases of environmental interactions before a significant fraction of the cold interstellar medium is removed. Combining HI morphological information and MHI−M⋆ ratio may reveal likely new members of the cluster (we come back to this point in Sect. 4).

Fornax galaxies with a disturbed HI morphology cover the full M⋆ range. However, we measure a stronger HI depletion for low mass galaxies: the average offset from the xGASS scaling relation in Fig. 6 is −0.86 dex and −0.33 dex for M⋆ below and above 3 × 109, respectively. We show the threshold of 3 × 109 M⊙ with a vertical dashed blue line in Fig. 6.

We already mentioned the problematic detection of NGC 1436. Although we are probably missing some flux, it remains a deficient galaxy even if we estimate the HI mass from the GBT flux (Table 1) with a log10(MHI/M⋆) = −2.0 and an offset from the xGASS scaling relation of −0.93 dex.

Figure 6 shows also eight galaxies where we did not detect HI emission but H2 was detected with with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA; Zabel et al. 2019). For these galaxies we calculated the MHI upper limit as 3× the local noise (Table 1) of the cube and assuming the CO line width of these galaxies estimated by the PV diagrams in Zabel et al. (2019). Some of these galaxies appear to have too little HI given the molecular gas content and star formation rate, as we discuss in following sections. We show the optical morphology of these galaxies in Appendix B.

Finally, Fig. 8 shows the comparison between Fornax and Virgo galaxies (from HRS – Boselli et al. 2014) belonging to Virgo clouds A, B, N, E and S (as defined by Gavazzi et al. 1999) with 109 ≲ M⋆ ≲ 1011 M⊙. Here we show the Virgo cluster galaxies and the average scaling relation obtained from them in the same M⋆ range (Cortese et al. 2011). Since Virgo is populated by HI poor galaxies with respect to field galaxies (Davies & Lewis 1973; Chamaraux et al. 1980; Cayatte et al. 1994; Hughes & Cortese 2009; Chung et al. 2009), this scaling relation is shifted towards lower gas fractions with respect to xGASS (Fig. 6). Although Fornax and Virgo galaxies experience different cluster environments, the distribution of Fornax galaxies cover the whole range of MHI/M⋆ of Virgo galaxies, reaching the same level of HI deficiency.

|

Fig. 8. Comparison of Fornax galaxies (same colour coding of Fig. 6) with Virgo cluster galaxies from HRS (light purple circles). Dark purple circles show the average scaling relation obtained from Virgo cluster galaxies (Cortese et al. 2011). |

3.3. Linking HI properties with H2 and SFR

The ratio between molecular and atomic gas mass (MH2/MHI) can be useful to identify anomalous galaxies where, for example, only the atomic phase is affected by the environment or HI is not efficiently converted to H2. We thus compared the atomic and molecular gas reservoirs of our detections (see Fig. 9). For this purpose, we used H2 masses from Zabel et al. (2019) for all our HI detections except for FCC 323 (no molecular gas data available). We also include in this analysis the eight galaxies detected with ALMA (Zabel et al. 2019) that are not detected in HI (upper limits in Figs. 6 and 8; see Sect. 3.2). We also scaled the molecular upper limit from Zabel et al. (2019) to be consistent with a line width of 100 km s−1. As a comparison, we used the xGASS M⋆−MH2/MHI scaling relation in Catinella et al. (2018), which describes the typical MH2/MHI ratio as a function of M⋆ at z = 0.

|

Fig. 9. MH2/MHI as a function of M⋆. We use the same colour coding as Fig. 6. Blue shadow shows 1 × σ scatter from the xGASS weighted average of log10(MH2/MHI). We show upper limits with downward arrows. We show lower limits with upward arrows. |

For M⋆ > 109 M⊙, 55% of all HI detected galaxies are also H2 detected, while this fraction drops to zero for M⋆ < 109 M⊙ (likely because the lower metallicity of these objects makes CO progressively harder to detect). In the rest of this section we therefore focus on the higher M⋆ range. Here, we see that about half of the galaxies are consistent with the xGASS sample, while most of the remaining galaxies are above the xGASS scaling (see Fig. 9). In particular, galaxies with a distorted HI morphology are compatible with the xGASS trend with the exception of NGC 1427A whose lack of molecular gas is puzzling (see Zabel et al. 2019). Although this galaxy has a normal (and large) HI mass for its stellar mass, no molecular gas was detected with ALMA. The agreement with the scaling relation holds also for NGC 1437B, which is the only HI deficient galaxy with a distorted morphology in this range of M⋆.

The detection with the highest MH2/MHI ratio is NGC 1436. Although we might be missing HI flux (Sect. 3.2), this mass ratio remains high even if we use the MHI value estimated from the GBT flux (with a MH2/MHI = 1.7). Other three galaxies, NGC 1386, NGC 1387 and NGC 1380, may be even more peculiar as the lower limit on their MH2/MHI ratio is already an order of magnitude above the xGASS scaling relation. High MH2/MHI ratios have also been measured in Virgo galaxies (Cortese et al. 2016).

Given the broad distribution of MH2/MHI ratio in Fornax, we further investigate whether their star formation rate follows standard scaling with M⋆ and MHI. In particular, we are interested in understanding whether the general offset of Fornax galaxies towards low MHI/M⋆ ratios in Fig. 6 is associated with a decrease of SFR at fixed M⋆.

We start by comparing Fornax galaxies with the same sample of non-cluster galaxies used in Sect. 3.2. SFR of both samples of Fornax galaxies and non-cluster galaxies are evaluated using Eq. (2) in Boquien et al. (2016). We set the scaling coefficient for the infrared 24 μm band (W4) equal to 6.17. We adopted the calibration factor for near UV 231 nm band (NUV) to be log10C = −43.17 (Kennicutt & Evans 2012). NUV fluxes come from GCAT (Seibert et al. 2012) and IRSA catalogues (Leroy et al. 2019). Since the latter catalogue is more reliable for galaxies at z = 0, we used it to get the NUV flux from Fornax galaxies. W4 was obtained using custom software optimised for performing aperture photometry on resolved galaxies (Jarrett et al. 2013; Cluver et al. 2014; Jarrett et al. 2019). Then, we removed the contribution from the evolved stellar populations using the method of Helou et al. (2004) which consists of scaling and subtracting the W1 light (a proxy of evolved stellar population) from W4 as described in Cluver et al. (2017). For a fraction of galaxies, NUV and W4 fluxes were not available (3/212 non-cluster galaxies; 11/24 Fornax galaxies). In these cases, we calculate the SFR from the W3 (12μm) luminosity – with stellar emission subtracted (as for W4)– and the TIR-to-MIR relation using Eq. (4) in Cluver et al. (2017), where L12μm is the continuum-subtracted spectral (ν × Lν) luminosity. Our conclusions below do not change if we calculate SFR from WISE data alone.

Figure 10 shows that the majority of the Fornax galaxies have a SFR below the values predicted by the scaling relation of Whitaker et al. (2012). Furthermore, the difference between the SFR of Fornax galaxies and that predicted from Whitaker et al. (2012) increases towards lower M⋆. That is, the SFR-M⋆ relation in Fornax is steeper than that of non-cluster galaxies. This might indicate a stronger SFR decrease in low-mass galaxies, similar to what observed for their HI reservoirs (as discussed in Sect. 3.2) and their H2 reservoirs (Zabel et al. 2019). Also when compared to the HRS+VGS comparison sample, Fornax galaxies appear to be offset towards lower SFR values, mirroring the results in Fig. 6.

|

Fig. 10. SFR as a function of M⋆. We use the same colour coding as Fig. 6. We show upper limits in SFR with downward arrows. The dashed black line represents the SFR scaling relation in Whitaker et al. (2012). |

Among the four galaxies with the highest MH2/MHI ratio in Fig. 9, NGC 1386 is the only one with a higher SFR than expected. This is likely due to the presence of an AGN (Rodríguez-Ardila et al. 2017) which affects the SFR measurement. The other two HI undetected galaxies, NGC 1380 and NGC 1387, reside at the lower edge of the comparison sample. We notice that NGC 1380 is also highly H2 deficient in Zabel et al. (2019).

In Fig. 11 we investigate whether, in Fornax, the low SFR (at fixed M⋆; Fig. 10) can be related to the HI deficiency (Fig. 6). This figure plots the SFR and MHI/M⋆ deviations from the respective scaling relations (Figs. 10 and 6) against one another. We find that Fornax galaxies mostly populate the area of the plot of HI deficient galaxies with low SFR, following the trend of non-cluster galaxies in the comparison sample. That is, in Fornax, a decrease in MHI is accompanied by a decrease in SFR just like in non-cluster galaxies. In Sect. 4 we present an interpretation of this result.

|

Fig. 11. SFR deviation from the Whitaker et al. (2012) scaling relation (Fig. 10) plotted against the MHI/M⋆ deviation from the xGASS scaling relation (Fig. 6). We use the same colour coding as Fig. 6. We show upper limits in MHI with leftward arrows. The horizontal blue line represents no deviation from the SFR scaling relation, while the vertical blue line represents no deviation from the M⋆−MHI/M⋆ scaling relation. |

On top of this general trend we see a few outliers. The most evident ones are ESO 358-G060 and the HI undetected NGC 1386. While the high SFR in NGC 1386 might be an artefact caused by the presence of an AGN, the case of ESO 358-G060 is more complicated. We carefully inspected this galaxy’s WISE images and no SFR from W3/W4 with old stellar population subtraction was detectable. Therefore, we calculated its SFR the from NUV flux alone using Eq. (12) in Kennicutt & Evans (2012). Although ESO 358-G060 is HI rich, its SFR is lower than that any galaxy of the comparison sample with a similar M⋆. It is worth noting the cases of NGC 1436 which lies at the upper edge of the comparison sample of HI deficient galaxy (bottom-left quadrant of Fig. 11) and NGC 1427A which shows a low SFR although its large HI reservoir. All these cases will be discussed in Sect. 4.

3.4. HI properties as a function of 3D location in Fornax cluster

In Fig. 12, we compare the 2D distribution of our Fornax HI detections with that of all spectroscopic Fornax members (Maddox et al. 2019) included within our survey footprint. Keeping in mind that the area of the sky that we observed is not symmetric, most of the galaxies in our sample are located south of the centre of the cluster, while only four out of 16 detections are located north of it.

|

Fig. 12. Distribution of our Fornax HI detections on the sky (blue and red markers) compared to that of all Fornax galaxies in our footprint (grey circles; Maddox et al. 2019). The green and gray contours are the same as Fig. 1. |

Almost all our HI detections (88% of the sample) are located farther than 0.5 Rvir in projection (the only exceptions being NGC 1427A at 0.2 Rvir, and ESO 358-G051 at 0.4 Rvir). In contrast, only 33% of all Fornax galaxies in our footprint are outside 0.5 Rvir.

The same effect, with the addition of the kinematical information, can be seen in the projected phase-space diagram shown in Fig. 13. We used a cluster systemic velocity of vsys = 1442 km s−1 and a cluster velocity dispersion of σcl = 318 km s−1 (Maddox et al. 2019). In order to draw caustic curves we proceeded as in Jaffé et al. (2015) using Mvir = 5 × 1013 M⊙, Rvir = 700 kpc (Drinkwater et al. 2001a) and a cluster halo concentration parameter equal to 6 (Navarro et al. 1996; the exact value of this parameter does not change the result significantly). The inner triangle shows the virialised area where it is more likely to find old members of the Fornax cluster (Rhee et al. 2017). From the right histogram in Fig. 13, we see that the spectroscopic Fornax members have a peak at the cluster systemic velocity, while velocities of our HI detections cover all velocity range without any preferred velocity. Thus, both Figs. 12 and 13 show that the HI galaxy sample does not follow the distribution of spectroscopic galaxies.

|

Fig. 13. Phase space diagram of the Fornax cluster. Here, we used the same colour coding as Fig. 12. We show the caustic curves of the cluster with black dashed lines. Histograms: black and gray colours represent HI detected galaxies and all Fornax members, respectively. The area within the black triangle shows the virialised area of the cluster. |

In Fig. 13, we also see that 11 out of 16 galaxies are within the escape velocity boundary in projection (black lines). It is worth noting that the HI deficient galaxies FCC 120 and ESO-LV 3580611 are located outside the caustic curves. Among HI disturbed galaxies, six out of eight are redshifted with respect to the recessional velocity of the cluster.

Both Figs. 12 and 13 show that some galaxies in our sample are not just close by one another on the sky but also in velocity. The clearest case is that of NGC 1365 and its three neighbours: FCC 102, FCC 090 and ESO 358-G016. They are all within a region of 250 kpc and a velocity range of 200 km s−1. These galaxies might be part of a substructure which is accreting onto the cluster (as suggested by Drinkwater et al. 2001a). In addition, most galaxies in this substructure exhibit indications of ongoing interactions with one another and/or with the intergalactic medium. Both HI elongations in FCC 102 and NGC 1365 point in projection to the north, while HI in FCC 090 is elongated towards the south. FCC 090, FCC 102 and NGC 1365 form a triplet of galaxies which lies along a line that points towards the centre of the cluster. ESO 358-G016 has a regular HI distribution and it lies in projection to the north of NGC 1365. All but NGC 1365 are HI deficient galaxies. The existence of a sub-group centred on NGC 1365 is also consistent with the large scale structure around Fornax (the Fornax-Eridanus supercluster), which is mainly made by several groups of galaxies that are assembling to form the cluster along the filament (Nasonova et al. 2011).

On the east of the cluster centre, we also see that FCC 323 and NGC 1437B are near each other on the sky in projection (∼120 kpc apart), as well as in velocity (∼10 km s−1 difference). The unresolved HI morphology of FCC 323 does not reveal, at this time, whether there is an ongoing interaction between those galaxies. We mark it as a potential subgroup.

Another intriguing galaxy is ESO 358-G060. Among the galaxies with M⋆ ≤ 109 M⊙ it is the only one with a normal HI content compared to non-cluster galaxies (see Fig. 6), and it shows no evidence of on-going interactions with the Fornax environment (see Fig. 2). Given its position just outside the caustic curves in Fig. 13, we discuss in Sect. 4 whether it might not have entered the cluster yet. Another, similar case is NGC 1437A. It is a HI rich galaxy which shows a quite regular HI morphology. It is also just outside the caustic curves in Fig. 13. However, unlike the undisturbed ESO 358-G060, the optical appearance of NGC 1437A is peculiar, similar to that of NGC 1427A, since they both exhibit an arrow shaped optical morphology as pointed out in Raj et al. (2019). The MeerKAT Fornax Survey (Serra et al. 2016) will deliver a higher resolution HI image of this object and will be able to reveal any HI asymmetries that might be hidden by projection effects within the ATCA beam.

4. Discussion

The population of HI detected Fornax galaxies exhibits several interesting features. Despite the limited resolution of our data, half of all detections reveal HI asymmetries and offsets relative to the stellar body (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the HI sample as a whole is gas-poorer and is forming stars at a lower rate than samples of non−cluster galaxies in the same M⋆ range (Figs. 6 and 10), and half of the galaxies with M⋆ > 109 M⊙ have an anomalous MH2/MHI ratio. Finally, the HI detections are distributed in a noticeably different way with respect to the majority of cluster galaxies both on the sky and in projected phase space (Figs. 12 and 13). This body of evidence suggests that the Fornax environment is influencing the evolution of these galaxies, which may be the most recent arrivals in the cluster. In particular, the difference between the 3D distribution of HI detected galaxies compared with that of spectroscopically confirmed Fornax members (Maddox et al. 2019), indicates that HI is a crucial observable to test the volume of the cluster where HI rich galaxies become HI deficient, before a complete HI removal in the inner part of the cluster.

An outstanding question is how long it takes for a galaxy to lose its HI – the dominant component of the interstellar medium – as it falls into a cluster. In the case of Fornax we can gain some insight through a joint analysis of Figs. 11 and 13. If we assume that HI is being actively removed from within galaxies in Fornax (as suggested by the frequently disturbed HI morphologies – see Fig. 2), the lack of HI detections in the virialised region of Fig. 13 implies that HI removal happens on a time scale τHI, loss shorter than the cluster’s crossing time: τHI, loss ≤ τcross ∼ Rvir/σcl ∼ 2 Gyr (see Sect. 3.4; this τcross is similar to that estimated from simulations, 1.2 ± 0.5 Gyr independent of cluster mass; Rhee et al. 2017). Hence, we expect that our 16 detections will have lost most of their HI by the time they reach the pericentre.

On the other hand, Fig. 11 suggests that, so far, HI has been lost slowly in our HI detections (having been removed and/or consumed, and not replenished). In that figure, our Fornax HI detections are distributed along the same correlation defined by non-cluster galaxies. Thus, for those Fornax galaxies, the SFR has so far had sufficient time to respond to a variation in HI mass – just like outside clusters. Since the transition from HI to new stars happens through the intermediate phase of H2, this ‘equilibrium’ between HI and SFR implies that H2 is depleted faster than HI is lost in galaxies currently at the cluster’s outskirts, giving the entire cycle of HI-to-H2-to-SFR enough time to ‘see’ the varying HI content. Thus, while for Fornax as whole τHI, loss ≤ τcross ∼ 2 Gyr (see above), for our HI detections in the outer regions of Fornax τHI, loss has so far been ≥τH2, depl ∼ 1−2 Gyr (Bigiel et al. 2008). (The H2 depletion time τH2, depl is only marginally shorter in Fornax, in particular at its outskirts, and anyway with large variations from galaxy to galaxy; Zabel et al. 2020.)

It is likely that, further inside Fornax, HI is removed faster than what we estimated above for galaxies at the cluster’s outskirts. Indeed, simulations indicate that for a galaxy within 0.5 Rvir, τHI, loss < 0.5 Gyr (Marasco et al. 2016). Such a rapid HI removal may not leave sufficient time for the SFR to ‘track’ the decrease in HI mass in Fig. 11, resulting in galaxies moving to the left of the non-cluster sample. A confirmation of this effect may come from the eight H2-detected galaxies (most of them H2-deficient; Zabel et al. 2019) where HI has already been removed at least down to the ATCA MHI sensitivity (left-pointing arrows in Fig. 11), and possibly by some HI detections closer to the cluster centre (e.g., NGC 1436). Indeed, these galaxies occupy a region to the left of the comparison sample, showing that their SFR is still significant despite their low HI content. For these galaxies, HI is likely to have been removed faster than H2 is depleted: τHI, loss ≤ τH2, depl. This conclusion is supported by the anomalously high MH2/MHI ratio of these galaxies in Fig. 9 (in the M⋆ range where we have a reliable comparison).

Within the picture discussed above, HI-detected galaxies in the outer regions of Fornax are thus first infallers, which are starting to interact with the Fornax environment and will lose most of their HI by the time they reach the pericentre. Even at the current early stage of infall, they already show a relatively large diversity in HI morphology (Fig. 2) and mass (Fig. 6). More specifically, we found two morphologically undisturbed HI rich galaxies (12% of the HI detections); four morphologically disturbed HI rich galaxies (25% of the HI detections); four morphologically disturbed HI deficient galaxies (25% of the HI detections); six morphologically undisturbed – within the ATCA resolution – HI deficient galaxies (38% of the HI detections).

The morphologically undisturbed HI-rich galaxies are ESO 358-G060 and NGC 1437A. They both reside outside the caustic curves in projection (Fig. 13) and, given their low M⋆, they should be easily perturbed by the Fornax environment. Thus, we speculate that they are recent Fornax members which have not yet had enough time to be significantly affected by the cluster. One possible caveat is the low resolution of our images, which may hide HI disturbances in particular in the case of the optically peculiar galaxy NGC 1437A. Another possibility is that they are outside the cluster volume or in a region with lower ICM density. ESO 358-G060 is also an outlier in Fig. 11, where the relatively high MHI/M⋆ does not correspond to a high SFR. In this galaxy no SFR was detectable from WISE W3/W4 bands (after subtracting the old stellar population light), and the NUV contribution to star formation is low. Several physical processes might account for the low SFR with respect to the large HI reservoir: for example, an inefficient HI to H2 conversion due to a small amount of dust, a large angular momentum which prevents the HI from collapsing, and/or an HI external origin (e.g., see Geréb et al. 2016, 2018).

The morphologically disturbed HI-rich galaxies are ESO 358-G063, NGC 1351A, NGC 1427A, NGC 1365. We discuss the last galaxy when we focus our attention on the HI detected subgroup of interacting galaxies. ESO 358-G063 and NGC 1351A, are both disc galaxies north of NGC 1399. They are both quite isolated from all other Fornax Galaxies in RA, Dec and velocity in projection (see Figs. 12 and 13). Thus, their slightly HI disturbed morphologies described in Sect. 3 might be due to the interaction with the ICM of the Fornax cluster. Furthermore, the agreement of MH2/MHI of ESO 358-G063 and NGC 1351A with the xGASS scaling relation in Fig. 9 suggests that they are recent Fornax members, thus the cluster environment has not had enough time to significantly deplete their HI reservoirs. The last morphologically disturbed HI rich galaxy is NGC 1427A. This is the galaxy with the second-highest HI mass in our sample of Fornax HI detections. In Figs. 12 and 13, we see that NGC 1427A is the closest HI detected galaxy to the centre of the cluster in projection, but it has also the highest velocity. Thus, it may be a new Fornax member which is infalling from the foreground. As already mentioned, Lee-Waddell et al. (2018) studied the origin of the HI tail using the same data we present here. They concluded that, unlike previously suggestions, ram-pressure is unlikely to be the main process shaping the galaxy’s optical appearance. Instead, NGC 1427A is most likely a recent merger remnant, thus shaped by tidal forces. The recent merger might be the cause of the low molecular column density and/or its low metallicity, resulting currently undetected by ALMA (Zabel et al. 2019; it is the upper limit with the highest M⋆ in Fig. 9). NGC 1427A is also the second HI rich outlier with low SFR in Fig. 11. The HI-to-H2 conversion might be inefficient to have a SFR consistent with its MHI/M⋆ ratio.

The only HI deficient and morphologically disturbed galaxies which do not belong to the NGC 1365 subgroup are: ESO-LV 3580611 and NGC 1437B. They are very close to one another on the sky but have significantly different velocities. The former is outside the caustic curve in projection (Fig. 13), which supports the hypothesis of an new infalling Fornax member made by Schröder et al. (2001). The latter has a velocity similar to the recessional velocity of the cluster. HI and molecular morphologies (the latter detected by Zabel et al. 2019) are elongated in the same direction. This suggests that both gas phases are experiencing the same environmental interaction. Raj et al. (2019) detected a tidal tail in NGC 1437B, which may be due to a recent fly-by of another galaxy. As mentioned in Sect. 3.4, although the evidence is not strong, NGC 1437B might be part of a subgroup of interacting galaxies which includes FCC 323. Thus, FCC 323 might be the fly-by galaxy that NGC 1437B has interacted with.

It is difficult to comment on the morphologically undisturbed HI deficient galaxies, since their symmetric HI distribution may be a consequence of the ATCA resolution. However, a very peculiar case is the truncated HI disc of NGC 1436. It is the closest spiral galaxy to the centre of the cluster detected in HI. Raj et al. (2019) observed an ongoing morphological transition into lenticular: the spiral structure is found only in its inner region, while the outer disc has the smooth appearance typically found in S0 galaxies.

The inner part of NGC 1436 appears regular also in H2, and the galaxy is just moderately H2 deficient (Zabel et al. 2019). It is also the only galaxy detected both in HI and H2 which shows a high MH2/MHI ratio in Fig. 9. These results and the evidence of morphological distortions only in the outer part of the galaxy suggest that this galaxy may have gone through a quick interaction with the cluster environment, which did not affect the inner spiral structure yet. This idea is corroborated by the fact that NGC 1436 lies on the upper edge on the comparison sample in Fig. 11, which means that despite its HI deficiency it is still forming stars at a significant rate.

Finally, we focus on the NGC 1365 subgroup. We discussed all the HI morphologies and the 3D distribution of the subgroup members in Sects. 3.1 and 3.4, respectively. As mentioned earlier, NGC 1365 is the only HI rich galaxy of the subgroup (Fig. 6) with a MHI at least two orders of magnitude larger than the other members. The HI distribution both in NGC 1365 and in FCC 102 is elongated to the north, while it is elongated to the south in FCC 090. ESO 358-G016 is the only galaxy with a regular HI morphology. It is also the only galaxy located north of NGC 1365. We propose two scenarios in order to explain the properties of the subgroup and its members: the former is a case of interaction between galaxies and the cluster environment which is responsible of the high MHI/M⋆ ratio of the low mass members. In contrast, due to to its deep gravitational potential, NGC 1365 has been able to retain its HI, although some of it has been perturbed. The latter scenario we propose, it is a case of preprocessing in a group of galaxies where the local environment of the subgroup was able to affect the MHI/M⋆ ratio of the low mass members before the group began to interact with the cluster environment.

In general, although we found a large variety of HI properties in our sample of HI detections, we detected an overall trend towards HI disturbances and deficiency in Fornax. Figure 6 makes evident an already evolved state of Fornax HI galaxies where ∼2/3 of the galaxies are HI deficient. Figure 6 also shows that the Fornax environment is more effective in altering the gas content of galaxies with M⋆ < 3 × 109 M⊙ (see Sect. 3.2).

Zabel et al. (2019) presented a similar study, where they compare Fornax and field galaxies based on their molecular gas properties. They found some molecular deficiency in all their detections except NGC 1365. However, galaxies with M⋆ < 3 × 109 M⊙ are both more H2-deficient and morphologically disturbed with respect to more massive galaxies, whose molecular gas morphology is always regular. We do not observe such a clear difference in HI. Indeed, we observe disturbed HI morphologies across our entire M⋆ range, confirming that atomic hydrogen is the best tracer of early interactions. Despite this difference between HI and H2 morphologies, we also note some similarities between our results and those in Zabel et al. (2019). Indeed, the mass range of molecular disturbed galaxies is also characterised by a stronger HI depletion. Conversely, the HI depletion is weaker in the mass range in which galaxies show regular molecular-gas morphologies (M⋆ > 3 × 109 M⊙; Sect. 3.2). Thus, both gas phases show that the Fornax environment is more effective in altering the gas content of low-mass galaxies compared to high-mass galaxies.

Finally, our results are in agreement with the FDS&F3D results (Iodice et al. 2019b,a). Indeed, almost all galaxies with a disturbed HI morphology are of late type and belong to the group of the infalling galaxies in Iodice et al. (2019b), which are symmetrically distributed around the cluster’s central region. These galaxies have active star formation and are located in the low-density region of the cluster, where the X-ray emission is faint or absent. Our results show that they are interacting with the cluster environment. Deeper into the cluster, the lack of HI detections is consistent with the result that this region is dominated by evolved early-type galaxies. Some of these galaxies have been able to retain part of their H2 reservoirs (Zabel et al. 2019), but not their HI.

5. Summary

The blind ATCA HI survey of the Fornax galaxy cluster covers a field of 15 deg2 out to a distance of ∼Rvir from the cluster centre. It has a spatial and velocity resolution of 67″ × 95″and 6.6 km s−1, respectively, and a 3σNHI and MHI sensitivity of ∼2 × 1019 cm−2 and ∼2 × 107 M⊙, respectively. The survey revealed HI emission from 16 Fornax galaxies covering a mass range of about three orders of magnitude, from 8 × 106 to 1.5 × 1010 M⊙. These galaxies exhibit a variety of disturbances of the HI morphology, including asymmetries, tails, offsets between HI and optical centres and a case of a truncated HI disc (Fig. 2). This suggests environmental interactions within or on their way to Fornax (whether with other galaxies, the large-scale potential or the intergalactic medium), supported by the offset of Fornax galaxies towards low MHI/M⋆ ratios with respect to the xGASS M⋆-MHI/M⋆ scaling relation (Fig. 6), and resulting in HI deficiencies similar to those observed in the Virgo cluster (Fig. 8). The HI sample of Fornax galaxies is also forming stars at a lower rate than samples of non-cluster galaxies at fixed M⋆ (Fig. 10). This deficit of SFR is consistent with the deficit of HI when compared to non-cluster galaxies (Fig. 11).

Our 16 detections reside outside the virialised region of the cluster – where the distribution of the general population of Fornax galaxies is clustered – both on the sky and in the projected phase space diagram (Figs. 12 and 13). This result implies that HI is lost down to the ATCA sensitivity within a crossing time (τHI, loss ≤ τcross ∼ 2 Gyr), and that our HI detections are recent arrivals in the cluster. They still reside at the outskirts of Fornax, where their HI and SFR properties suggest that HI has so far been lost on a time scale longer than the H2 depletion time (τHI, loss ≥ τH2, depl ∼ 1−2 Gyr). In the cluster’s central regions HI removal is likely to proceed faster (τHI, loss < τH2, depl). This is supported by the relatively high SFR of HI-undetected, H2-detected galaxies and by the anomalously high MH2/MHI ratios of galaxies in those regions (Figs. 9, 12 and 13). These are galaxies where SFR is likely to be proceeding relatively unperturbed after rapid removal of the HI.

This picture is enriched by the new detection of the NGC 1365 subgroup – where both pre-processing and early interaction with the cluster environment are plausible scenarios to account for the HI properties of its members – and by the detection of several galaxies with peculiar ISM properties, such as some HI-rich but H2-poor and low-SFR galaxies (NGC 1427A, ESO 358-G060). The future MeerKAT Fornax Survey (Serra et al. 2016) will observe this cluster with a better resolution and sensitivity than those of our ATCA survey, enabling a further step forward in the study of the evolution of Fornax galaxies.

Data available on https://atoa.atnf.csiro.au/query.jsp

Acknowledgments

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 679627; project name FORNAX). Parts of this research were supported by the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for All Sky Astrophysics in 3 Dimensions (ASTRO 3D), through project number CE170100013. L. C. is the recipient of an Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (FT180100066) funded by the Australian Government. This publication has received funding from the European Union Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement number 721463 to the SUNDIAL ITN network. N. Z. acknowledges support from the European Research Council (ERC) in the form of Consolidator Grant CosmicDust (ERC-2014-CoG-647939). This work made use of the Digitized Sky Surveys, which were produced at the Space Telescope Science Institute under U.S. Government grant NAG W-2166. The Australia Telescope Compact Array is part of the Australia Telescope National Facility which is funded by the Australian Government for operation as a National Facility managed by CSIRO. We acknowledge the Gomeroi people as the traditional owners of the Observatory site.

References

- Barnes, D. G., Staveley-Smith, L., Webster, R. L., & Walsh, W. 1997, MNRAS, 288, 307 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, D. G., Staveley-Smith, L., de Blok, W. J. G., et al. 2001, MNRAS, 322, 486 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bigiel, F., Leroy, A., Walter, F., et al. 2008, AJ, 136, 2846 [Google Scholar]

- Blakeslee, J. P., Jordán, A., Mei, S., et al. 2009, ApJ, 694, 556 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Boquien, M., Kennicutt, R., Calzetti, D., et al. 2016, A&A, 591, A6 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Boselli, A., & Gavazzi, G. 2006, PASP, 118, 517 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Boselli, A., & Gavazzi, G. 2009, A&A, 508, 201 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Boselli, A., Cortese, L., & Boquien, M. 2014, A&A, 564, A65 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau, M., Mould, J. R., & Staveley-Smith, L. 1996, ApJ, 463, 60 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cantiello, M., D’Abrusco, R., Spavone, M., et al. 2018, A&A, 611, A93 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Catinella, B., Saintonge, A., Janowiecki, S., et al. 2018, MNRAS, 476, 875 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cayatte, V., Kotanyi, C., Balkowski, C., & van Gorkom, J. H. 1994, AJ, 107, 1003 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chamaraux, P., Balkowski, C., & Gerard, E. 1980, A&A, 83, 38 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Chung, A., van Gorkom, J. H., Kenney, J. D. P., Crowl, H., & Vollmer, B. 2009, AJ, 138, 1741 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cluver, M. E., Jarrett, T. H., Hopkins, A. M., et al. 2014, ApJ, 782, 90 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cluver, M. E., Jarrett, T. H., Dale, D. A., et al. 2017, ApJ, 850, 68 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Condon, J. J., Cotton, W. D., Greisen, E. W., et al. 1998, AJ, 115, 1693 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cortese, L., Catinella, B., Boissier, S., Boselli, A., & Heinis, S. 2011, MNRAS, 415, 1797 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cortese, L., Bekki, K., Boselli, A., et al. 2016, MNRAS, 459, 3574 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Courtois, H. M., Tully, R. B., Fisher, J. R., et al. 2009, AJ, 138, 1938 [Google Scholar]

- Davies, R. D., & Lewis, B. M. 1973, MNRAS, 165, 231 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- de Vaucouleurs, G., de Vaucouleurs, A., Corwin, H. G., et al. 1991, Third Reference Catalogue of Bright Galaxies [Google Scholar]

- Dey, A., Schlegel, D. J., Lang, D., et al. 2019, AJ, 157, 168 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Diaferio, A., Kauffmann, G., Balogh, M. L., et al. 2001, MNRAS, 323, 999 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dressler, A. 1980, ApJ, 236, 351 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dressler, A. 1986, ApJ, 301, 35 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Drinkwater, M. J., Gregg, M. D., & Colless, M. 2001a, ApJ, 548, L139 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Drinkwater, M. J., Gregg, M. D., Holman, B. A., & Brown, M. J. I. 2001b, MNRAS, 326, 1076 [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, H. C. 1989, AJ, 98, 367 [Google Scholar]

- Frank, K. A., Peterson, J. R., Andersson, K., Fabian, A. C., & Sanders, J. S. 2013, ApJ, 764, 46 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gavazzi, G., Boselli, A., Scodeggio, M., Pierini, D., & Belsole, E. 1999, MNRAS, 304, 595 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Geréb, K., Catinella, B., Cortese, L., et al. 2016, MNRAS, 462, 382 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Geréb, K., Janowiecki, S., Catinella, B., Cortese, L., & Kilborn, V. 2018, MNRAS, 476, 896 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Giovanelli, R., & Haynes, M. P. 1983, AJ, 88, 881 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Grillmair, C. J., Freeman, K. C., Bicknell, G. V., et al. 1994, ApJ, 422, L9 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn, J. E., Gott, J., & Richard, I. 1972, ApJ, 176, 1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hamraz, E., Peletier, R. F., Khosroshahi, H. G., et al. 2019, A&A, 625, A94 [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, M. P., & Giovanelli, R. 1984, AJ, 89, 758 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, M. P., & Giovanelli, R. 1986, ApJ, 306, 466 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Horellou, C., Black, J. H., van Gorkom, J. H., et al. 2001, A&A, 376, 837 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Hubble, E., & Humason, M. L. 1931, ApJ, 74, 43 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, T. M., & Cortese, L. 2009, MNRAS, 396, L41 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Iodice, E., Capaccioli, M., Grado, A., et al. 2016, ApJ, 820, 42 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Iodice, E., Spavone, M., Capaccioli, M., et al. 2017, ApJ, 839, 21 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Iodice, E., Spavone, M., Capaccioli, M., et al. 2019a, A&A, 623, A1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Iodice, E., Sarzi, M., Bittner, A., et al. 2019b, A&A, 627, A136 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffé, Y. L., Smith, R., Candlish, G. N., et al. 2015, MNRAS, 448, 1715 [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett, T. H., Masci, F., Tsai, C. W., et al. 2013, AJ, 145, 6 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett, T. H., Cluver, M. E., Brown, M. J. I., et al. 2019, ApJS, 245, 25 [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M. G., Espada, D., Verdes-Montenegro, L., et al. 2018, A&A, 609, A17 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Jordán, A., Blakeslee, J. P., Côté, P., et al. 2007, ApJS, 169, 213 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Jorsater, S., & van Moorsel, G. A. 1995, AJ, 110, 2037 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kennicutt, R. C., & Evans, N. J. 2012, ARA&A, 50, 531 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Koribalski, B. S., Staveley-Smith, L., Kilborn, V. A., et al. 2004, AJ, 128, 16 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kreckel, K., Platen, E., Aragón-Calvo, M. A., et al. 2012, AJ, 144, 16 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lauberts, A., & Valentijn, E. A. 1989, The Surface Photometry Catalogue of the ESO-Uppsala Galaxies (Garching: European Southern Observatory) [Google Scholar]

- Lee-Waddell, K., Serra, P., Koribalski, B., et al. 2018, MNRAS, 474, 1108 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Leroy, A. K., Sandstrom, K. M., Lang, D., et al. 2019, ApJS, 244, 24 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lupton, P. 2005, http://www.sdss3.org/dr8/algorithms/sdssUBVRITransform.php [Google Scholar]

- Maddox, N., Hess, K. M., Obreschkow, D., Jarvis, M. J., & Blyth, S. L. 2015, MNRAS, 447, 1610 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Maddox, N., Serra, P., Venhola, A., et al. 2019, MNRAS, 490, 1666 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Marasco, A., Crain, R. A., Schaye, J., et al. 2016, MNRAS, 461, 2630 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, L. D., van Driel, W., & Gallagher, J. S. I. 1998, AJ, 116, 1169 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, M., Robotham, A., Obreschkow, D., et al. 2017, PASA, 34, 52 [Google Scholar]

- Mould, J. R., Hughes, S. M. G., Stetson, P. B., et al. 2000, ApJ, 528, 655 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nasonova, O. G., de Freitas Pacheco, J. A., & Karachentsev, I. D. 2011, A&A, 532, A104 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, J. F., Frenk, C. S., & White, S. D. M. 1996, ApJ, 462, 563 [Google Scholar]

- Oemler, A. 1974, ApJ, 194, 1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Oh, S., Kim, K., Lee, J. H., et al. 2018, ApJS, 237, 14 [Google Scholar]

- Ondrechen, M. P., & van der Hulst, J. M. 1989, ApJ, 342, 29 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Paolillo, M., Fabbiano, G., Peres, G., & Kim, D. W. 2002, ApJ, 565, 883 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Peletier, R., Iodice, E., Venhola, A., et al. 2020, ArXiv e-prints [arXiv:2008.12633] [Google Scholar]

- Raj, M. A., Iodice, E., Napolitano, N. R., et al. 2019, A&A, 628, A4 [Google Scholar]

- Rhee, J., Smith, R., Choi, H., et al. 2017, ApJ, 843, 128 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Ardila, A., Prieto, M. A., Mazzalay, X., et al. 2017, MNRAS, 470, 2845 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sault, R. J., Teuben, P. J., & Wright, M. C. H. 1995, in A Retrospective View of MIRIAD, eds. R. A. Shaw, H. E. Payne, & J. J. E. Hayes, ASP Conf. Ser., 77, 433 [Google Scholar]

- Schröder, A., Drinkwater, M. J., & Richter, O. G. 2001, A&A, 376, 98 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer, F. 1980, ApJ, 237, 303 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Seibert, M., Wyder, T., Neill, J., et al. 2012, in American Astronomical Society Meeting Abstracts #219, Am. Astron. Soc. Meeting Abstr., 219, 340.01 [Google Scholar]

- Serra, P., Jurek, R., & Flöer, L. 2012, PASA, 29, 296 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Serra, P., Westmeier, T., Giese, N., et al. 2015, MNRAS, 448, 1922 [Google Scholar]

- Serra, P., de Blok, W. J. G., Bryan, G. L., et al. 2016, MeerKAT Science: On the Pathway to the SKA, 8 [Google Scholar]

- Serra, P., Maccagni, F. M., Kleiner, D., et al. 2019, A&A, 628, A122 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Sheardown, A., Roediger, E., Su, Y., et al. 2018, ApJ, 865, 118 [Google Scholar]

- Sheen, Y.-K., Yi, S. K., Ree, C. H., & Lee, J. 2012, ApJS, 202, 8 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Solanes, J. M., Giovanelli, R., & Haynes, M. P. 1996, ApJ, 461, 609 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Solanes, J. M., Manrique, A., García-Gómez, C., et al. 2001, ApJ, 548, 97 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Spavone, M., Iodice, E., van de Ven, G., et al. 2020, A&A, 639, A14 [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Spiniello, C., Napolitano, N. R., Arnaboldi, M., et al. 2018, MNRAS, 477, 1880 [Google Scholar]

- Su, A. H., Salo, H., Janz, J., et al. 2021, A&A, 647, A100 [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Theureau, G., Bottinelli, L., Coudreau-Durand, N., et al. 1998, A&AS, 130, 333 [Google Scholar]

- Toomre, A., & Toomre, J. 1972, ApJ, 178, 623 [Google Scholar]

- van der Hulst, J. M., Ondrechen, M. P., van Gorkom, J. H., & Hummel, E. 1983, in Internal Kinematics and Dynamics of Galaxies, ed. E. Athanassoula, IAU Symp., 100, 233 [Google Scholar]

- Venhola, A., Peletier, R., Laurikainen, E., et al. 2018, A&A, 620, A165 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Venhola, A., Peletier, R., Laurikainen, E., et al. 2019, A&A, 625, A143 [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J., Koribalski, B. S., Serra, P., et al. 2016, MNRAS, 460, 2143 [Google Scholar]

- Waugh, M. 2005, PhD Thesis, University of Melbourne, Australia [Google Scholar]

- Waugh, M., Drinkwater, M. J., Webster, R. L., et al. 2002, MNRAS, 337, 641 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker, K. E., van Dokkum, P. G., Brammer, G., & Franx, M. 2012, ApJ, 754, L29 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zabel, N., Davis, T. A., Smith, M. W. L., et al. 2019, MNRAS, 483, 2251 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zabel, N., Davis, T. A., Sarzi, M., et al. 2020, MNRAS, [Google Scholar]

Appendix A: Comments on individual H I -detected galaxies

In this section, we describe in detail each galaxy of our sample. Whenever possible we compare the information estimated from our HI data with observations at other wavelengths. The galaxies are sorted according to increasing HI mass as in Figs. 2 and 3.

A.1. FCC 323

According to Ferguson (1989), FCC 323 is a dE2/ImV. This is the faintest among our HI detections and, for the first time, we detected it in HI and thus measured its recessional velocity of vHI = 1502 km s−1. FCC 323 has a MHI = (0.8 ± 0.3) × 107 M⊙ and a M⋆ = (0.6 ± 0.6) × 108 M⊙. The Fornax environment might have strongly affected the HI reservoir of FCC 323. It has the highest MHI/M⋆ offset from the (extrapolated) xGASS scaling relation in Fig. 6. Its closest galaxy both on the sky and velocity is NGC 1437B (120 kpc and 12 km s−1 away), leading us to think that FCC 323 and NGC 1437B might be part of a subgroup or a pair of galaxies.

A.2. FCC 120

FCC 120 is classified as ImIV by Ferguson (1989). The HI emission associated with the galaxy seems to be quite regular. The ATCA spectrum in Fig. 3 shows one peak (within the uncertainties), which is different from the 100-km s−1 – wide double horn spectrum detected by Schröder et al. (2001) based on Parkes data. Even if the latter data shows strong RFI at a velocity of 1250 km s−1, this RFI does not affect the detection of the galaxy. However, vopt from Maddox et al. (2019), agrees with our vHI. Deeper HI data (Serra et al. 2016) may confirm this. FCC 120 has a MHI = (0.4 ± 0.1) × 108 M⊙ and a M⋆ = (1.6 ± 0.5) × 108 M⊙.

A.3. FCC 102