| Issue |

A&A

Volume 653, September 2021

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A43 | |

| Number of page(s) | 22 | |

| Section | Numerical methods and codes | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202140986 | |

| Published online | 07 September 2021 | |

YARARA: Significant improvement in RV precision through post-processing of spectral time series

Astronomy Department of the University of Geneva, 51 ch. des Maillettes, 1290 Versoix, Switzerland

e-mail: michael.cretignier@unige.ch

Received:

2

April

2021

Accepted:

14

June

2021

Aims. Even the most precise radial-velocity instruments gather high-resolution spectra that present systematic errors that a data reduction pipeline cannot identify and correct for efficiently by simply analysing a set of calibrations and a single science frame. In this paper we aim at improving the radial-velocity precision of HARPS measurements by ‘cleaning’ individual extracted spectra using the wealth of information contained in spectral time series.

Methods. We developed YARARA, a post-processing pipeline designed to clean high-resolution spectra of instrumental systematics and atmospheric contamination. Spectra are corrected for: tellurics, interference patterns, detector stitching, ghosts, and fibre B contaminations, as well as more advanced spectral line-by-line corrections. YARARA uses principal component analysis on spectral time series with prior information to disentangle contaminations from real Doppler shifts. We applied YARARA to three systems, HD 10700, HD 215152, and HD 10180, and compared our results to the standard HARPS data reduction software and the SERVAL post-processing pipeline.

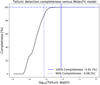

Results. We ran YARARA on the radial-velocity dataset of three stars intensively observed with HARPS: HD 10700, HD 215152, and HD 10180. For HD 10700, we show that YARARA enables us to obtain radial-velocity measurements that present an rms smaller than 1 m s−1 over the 13 years of the HARPS observations, which is 20% and 10% better than the HARPS data reduction software and the SERVAL post-processing pipeline, respectively. We also injected simulated planets into the data of HD 10700 and demonstrated that YARARA does not alter pure Doppler-shifted signals. For HD 215152, we demonstrated that the 1-year signal visible in the periodogram becomes marginal after processing with YARARA and that the signals of the known planets become more significant. Finally, for HD 10180, the six known exoplanets are well recovered, although different orbital parameters and planetary masses are provided by the new reduced spectra.

Conclusions. The post-processing correction of spectra using spectral time series allows the radial-velocity precision of HARPS data to be significantly improved and demonstrates that for the extremely quiet star HD 10700 a radial-velocity rms better than 1 m s−1 can be reached over the 13 years of HARPS observations. Since the processing proposed in this paper does not absorb planetary signals, its application to intensively followed systems is promising and will certainly result in advances in the detections of the lightest exoplanets.

Key words: methods: data analysis / techniques: radial velocities / techniques: spectroscopic

© ESO 2021

1. Introduction

During the last 25 years, discoveries of exoplanets by radial velocity (RV) have considerably improved our knowledge about the diversity of exoplanetary systems. Nevertheless, detections of exoplanets are somewhat biased towards the detections of massive and short-periods planets. The discovery of a sub-metre-per-second planetary signal with a period comparable to or longer than a year remains extremely challenging due to several factors, such as instrumental systematics, atmospheric contamination, and stellar activity.

Obtaining extremely precise radial velocities (EPRVs) is an art that requires: (1) a high-resolution super-stable spectrograph with high spectral fidelity to provide the cleanest possible spectra at the pre-calibration stage, (2) a data reduction pipeline that extracts, at best, the spectra from raw frames, corrects the instrumental systematics using a set of calibration frames, and extracts relevant information, such as the final RV of the spectrum, and (3) a post-processing of the RV time series to correct for stellar activity signals.

Due to tremendous progress in instrumentation, point (1) is becoming less of a concern due to the new generation of EPRV spectrographs, such as ESPRESSO (Pepe et al. 2014, 2021), EXPRES (Fischer et al. 2017), and MAROON-X (Seifahrt et al. 2018; Peck 2020; Sanchez et al. 2021), which have already demonstrated RV measurements with root mean square (rms) significantly smaller than 1 m s−1. The correction of stellar activity in the RV time series, point (3), has also been widely studied (e.g., Haywood et al. 2014; Grunblatt et al. 2015; Davis et al. 2017; Jones et al. 2017; Dumusque 2018; Cretignier et al. 2020a; Kosiarek & Crossfield 2020; Collier Cameron et al. 2021). Only point (2), corresponding to a better extraction of the RV content of a spectra, has not been intensively studied in the last decade. Only a few papers have recently addressed this question (Dumusque 2018; Errmann et al. 2020; Zechmeister et al. 2020; Trifonov et al. 2020). However, this step is essential for better understanding stellar activity if an improvement in RV precision can be obtained.

It is known that different systematics on the spectra introduce RV effects. As examples, we can cite the colour variation in a spectrum with airmass or a change in atmospheric conditions, tellurics, or micro-tellurics (Artigau et al. 2014), as well as more instrument-related systematics specific to the HARPS instrument, such as the detector stitching (Dumusque et al. 2015). All these contaminations can be somewhat tricky to resolve when considering individual spectra, and corrections can only be achieved by successfully modelling the effects using prior information.

A methodology for correcting for these features is to consider spectral time series instead of individual spectra, as the former contain a richness of information far more extended than the latter. For example, this methodology shows its potential in the WOBBLE code (Bedell et al. 2019), which is designed to remove telluric lines by performing a principal component analysis (PCA), or in the Gaussian process (GP) framework developed by Rajpaul et al. (2020).

Following the WOBBLE approach, we developed a post-processing RV pipeline called YARARA to cope with any known systematics in HARPS spectra. We show that by using the power of PCA on HARPS spectral time series, we can correct for any known systematics without the need for models for the different effects and with a limited amount of prior information. Such a data-driven approach is well suited to be applied to high signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) spectra of ultra-stable spectrographs and to stars that have been intensively observed. Fortunately, such datasets are the only ones in which we can hope to search for sub-metre-per-second planetary signals, and thus the methodology used by YARARA is perfectly fitted to reach the best RV precision and look for the lightest exoplanets.

In this paper we apply our new post-processing pipeline YARARA to HARPS (Pepe et al. 2002a; Mayor et al. 2003; Pepe et al. 2003) data to demonstrate that further improvements can still be accomplished on HARPS RV measurements. The theory behind YARARA is described in Sect. 2. The different corrections performed in this work are described in the same order as they are implemented in the pipeline for HARPS, namely by correcting for: cosmic rays (Sect. 2.2), interference patterns (Sect. 2.3), telluric lines (Sect. 2.4), stellar lines variations (Sect. 2.5), ghosts (Sect. 2.6), stitchings (Sect. 2.7), simultaneous calibration contamination (Sect. 2.8), and continuum correction (Sect. 2.9). The line-by-line (LBL) RV derivation is described in 2.10, and a more advanced LBL correction is presented in Sect. 2.11. The applications of YARARA to three stellar systems are presented in Sect. 3 (Sect. 3.1 for HD 10700, Sect. 3.2 for HD 215152, and Sect. 3.3 for HD 10180). We then conclude in Sect. 4.

2. Description of the pipeline

The pipeline can be described as a sequential cascade of recipes applied to correct for the different systematics. The sequence described below is optimised for HARPS and was chosen based on two criteria: (i) the constrain we can have on the correction and (ii) the amplitude of the systematic in flux. Having a correction that is well constrained allows us to reduce the degeneracy with other recipes. Moreover, since we mainly use multi-linear regression to perform our corrections, it is necessary to correct first for the contaminations with the largest flux variance.

We note that different instruments might have a different sequential cascade depending on if the same or other contaminations exist and if they have different intensities.

The assumption behind the sequential approach is to assume that the different contaminations are orthogonal to each other. We will see further that this is the case if prior information (e.g., systematic structure, wavelength domain) is used to constrain the different recipes and if the baseline of the observations is long enough to avoid spurious correlations. As a consequence, YARARA is mainly applicable to system intensively observed and for which a high S/N (> 100) can be obtained.

Our approach also assumes that the point spread function (PSF) does not vary significantly over time, and thus the data must come from the same stable spectrograph. We note that on HARPS, the change of the optical fibres in 2015 (Lo Curto et al. 2015) significantly changed the instrumental PSF. We therefore have to consider two instruments, one before and one after the upgrade. However, those two instruments are suffering from the same systematics, hence the same cascade of recipes can be applied. The only restriction is that spectral time-series objects before and after the fibre upgrade cannot be mixed in the pipeline and must be reduced separately.

In this work we call the map representing, in each row, a spectrum residual with respect to some reference a ‘river diagram map’. We note that here we always represent river diagrams as the difference with respect to the median spectrum of the spectral time series. Since all the spectra are on a common wavelength grid, the spectral time series can be seen as a matrix. We refer to the variation in the flux f(λj, t) as a function of the time t for a specific wavelength λj in this matrix as the ‘wavelength column’. Each column is assumed independent for simplicity. The general mathematical framework of the corrections applied in YARARA take the shape of a multi-linear model fitted on the wavelength columns:

where αi(λj) are the strength coefficients, fitted for using a weighted least-square considering as weight the inverse of the flux uncertainty squared, Pi(t) are the elements of the basis fitted and λj are the wavelengths either in the stellar or terrestrial rest frame. The data δf(λj, t) can be either a spectra difference or a ratio with respect to a master spectrum f0(λj), depending on the systematics we want to correct for. Each time an RV shift of the spectra is performed, a cubic interpolation is used to resample the shifted spectra on a common λj wavelength grid. The Pi(t) basis will be made either of cross-correlation function (CCF) moments (contrast and FWHM) obtained by a weighted least-square Gaussian fit, or principal components of a weighted PCA (Bailey 2012) trained on a specific set of wavelengths λj. In all cases, the weights are defined as the inverse of the flux uncertainty squared.

2.1. Data pre-processing

To be efficient, spectral time-series objects must be continuum normalised, which is difficult due to the varying extinction of the Earth’s atmosphere. A solution for echelle-grating instruments, consists in correcting the colour by scaling the spectra with a reference template or reference colour curve (e.g., Berdiñas et al. 2016; Malavolta et al. 2017). However, such corrections are usually performed order-by-order, which does not account for intra-order variations. A new approach based on alpha-shape regression was presented by Xu et al. (2019) on EXPRES spectra, where the authors demonstrated the better performance of alpha-shape algorithms compared to a more naive approach, such as iterative fitting methods (Tody 1986, 1993). Similarly, we developed a Python code called RASSINE (Cretignier et al. 2020b) and demonstrated its precision in flux on HARPS merged 1D spectra down to 0.10%. RASSINE therefore appears as a well-suited tool for normalising spectra at the precision required to correct for the instrumental systematics.

The initial products given as input to YARARA are normalised merged 1D spectra. In this work, we started from HARPS merged 1D spectra produced by the official data reduction software (DRS), pre-processed them as follow, and then continuum normalised them using RASSINE. All the spectra are shifted in the stellar rest frame, night-drift corrected and evaluated on the same wavelength grid by a linear interpolation. Wavelengths longer than 6835 Å were discarded due to the presence of the strong β oxygen band. If the data contains large Doppler shift variations, typically larger than ∼5 m s−1 on HARPS, induced by binary companion or massive planets, the spectra are shifted to cancel this RV shift before being interpolated on the common wavelength grid. Smaller RV variations do not need to be corrected for since smaller RV amplitudes do not produce strong flux signatures in river diagram. Such a correction was unnecessary for the three stellar systems studied in Sect. 3. Spectra are then nightly stacked to improve the S/N and finally normalised in automatic mode by RASSINE using the spectral time-series option, which allows the same local maxima to be selected on all the individual spectra (see Cretignier et al. 2020b for more information).

We note that we decided to bin the spectra within a day, to help the normalisation process, as the upper envelope approach used by RASSINE to find the continuum is biased at low S/N. In addition, nightly binning helps in mitigating granulations and stellar oscillations (Bouchy & Carrier 2001; Vázquez Ramió et al. 2005; Nordlund et al. 2009; Rieutord et al. 2010; Dumusque et al. 2011; Cegla et al. 2019), which induce RV variations with timescales smaller than a day.

2.2. Cosmic ray correction

Cosmic rays are high-energy particles that produce straight bright lines on raw images. When the anomaly created by a cosmic falls on the same pixel as the stellar spectrum, the real stellar flux is lost and the extracted stellar spectrum is significantly affected. This will thus strongly affect the derivation of RV locally on the spectra, as we will see further below1. In addition, in the context of YARARA, cosmic rays are seen as strong outliers and their impact has to be corrected for to improve the convergence of the different regressions that YARARA performs in the hereafter recipes.

In Cretignier et al. (2020b), the authors demonstrated that RASSINE is insensitive to cosmic rays since they can be flagged as local maxima with excessive derivative. Thus, cosmic rays will appear as spikes with values higher than one in normalised flux units (see Fig. 1). To detect them, for each wavelength column, we performed a 3-sigma clipping on the flux of all the spectra2 and only removed the outliers larger than one. Such a technique removes efficiently the highest contaminations as visible in Fig. 1. We note that more outliers could be removed by pushing down the threshold on the sigma clipping; however, this could also remove contaminations other than cosmic rays, and removing them at this stage would make it more difficult to correct for them afterwards.

|

Fig. 1. First flux correction performed by YARARA to remove cosmic rays contamination. The 277 RASSINE-normalised spectra of HD 215152 are represented superposed before (black) and after (blue) YARARA cosmic ray cleaning. Cosmic rays are corrected by replacing every 5-sigma outlier larger than one by its value in the median spectrum. |

2.3. Interference pattern correction

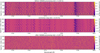

On HARPS, an interference pattern was produced by mistake on FLAT calibration frames due to the use of a black body minus filter to balance the spectral energy distribution of a new Tungsten lamp installed in 2007. This filter was positioned in a collimated beam path, which produced the observed pattern following the thin-film interference law. This issue was solved during an upgrade of the instrument in August 2009, by moving the filter in a diverging beam. Hence, these systematics are only visible during two years of the HARPS observations (see Fig. 2). If the pattern frequency is low enough, RASSINE will naturally correct the oscillation as shown for ESPRESSO spectra in Allart et al. (2020). If the pattern has a high frequency, like for HARPS, with a periodicity shorter than one Angström, it needs to be corrected for.

|

Fig. 2. Second and third flux corrections performed by YARARA to remove interference patterns and telluric absorption lines contaminations on HD 10700. The standard deviation of each residual map is indicated in the title. Top: river diagram before YARARA corrections. Spectra suffer from interference patterns on two observational seasons (from index 30 to 97). Middle: model fitted by YARARA for the contaminations. Bottom: residual river diagram after YARARA correction. |

The interference pattern has a unique frequency with time; however, the phase of the signal can change from day-to-day. We therefore decided to correct for the perturbing signal in the Fourier domain. To highlight at best the effect, we computed spectra ratio between each spectrum and the median of all excluding from the median all the spectra between 3 April 2007 and 24 July 2009, which are known to be affected. We then computed the fast fourier transform (FFT) of all the spectra ratio. For the spectra ratio that are showing excess of power around a width3 of 1.5 mm for a refractive index n = 1 (see Fig. 9 in Cretignier et al. 2020b), we replaced the region with the excess of power by the same region seen in the FFT of the highest S/N ratio spectra obtained outside of the contaminated time frame. The cleaned spectra are recovered by performing an inverse FFT followed by a multiplication with the median spectrum. This strategy successfully worked to remove the interference pattern as displayed in Fig. 2. We note that on HARPS we needed to treat the blue and red detectors differently as the gap in wavelength between the two charge-coupled devices (CCDs) was producing artefacts in the Fourier space.

2.4. Telluric line correction

Telluric lines are terrestrial atmospheric lines fixed in the barycentric Earth RV (BERV) rest frame that shift with respect to stellar lines and cross them due to the Earth reflex motion around the Sun, reducing the RV precision (Artigau et al. 2014; Cunha et al. 2014). In the visible, telluric lines come exclusively from water vapour or oxygen lines and both species will be corrected for differently. Indeed, whereas oxygen lines are stable with time and only show minor variations with airmass, water vapour lines exhibit large night-to-night and even intra-night variations (Li et al. 2018) depending on the humidity content in the air and the atmospheric conditions. Some methods based on line profile telluric modelling (Blake & Shaw 2011; Bertaux et al. 2014; Smette et al. 2015) try to remove this contamination by using some prior information as those measured at the observational site (Baker et al. 2017). Unfortunately, such measurements are only providing local information on the ground, whereas the real information should be the column density of water along the direction of the observations, which is not a commonly derived quantity (Kerber et al. 2012). Another method consists in getting a high S/N spectrum of an hot standard star in order to extract the telluric spectrum (e.g., Artigau et al. 2014), but such a method is time consuming and observationally expensive.

A more data-driven approach will take advantage that telluric lines are fixed in the BERV rest frame and can therefore be disentangled from the stellar spectrum. This method has been successfully used in Bedell et al. (2019), where the authors used a flexible data-driven model to remove the contamination. We use a similar approach, except that a PCA correction will solely be used as a second-stage correction, after applying a first step correction consisting of a multi-linear regression of the telluric CCF moments.

We use as prior information the position of the water and oxygen telluric lines as given by Molecfit (Smette et al. 2015). With these positions, a binary mask of water telluric lines is constructed in order to compute a telluric CCF. As a remark, the δ oxygen band around 5790 Å is missing from the Molecfit database. We added the line positions by hand as they were clearly visible in our river diagram maps (see Fig. 2).

Because telluric lines present shallower depth than stellar lines, performing a CCF directly on the spectra will mainly contain stellar information. Switching to transmission spectra, dividing the observed spectra by a telluric-free stellar spectrum f0(λj) removes the contribution of stellar lines. Since the density of the telluric lines is quite low for the visible, we can build such a telluric-free stellar spectrum from the observations. This requires that for each specific wavelength column λj, at least one observation is not affected by tellurics. This hypothesis is equivalent to asking that the observations are probing a wide range of BERV values, where wide mean a range larger than the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the telluric lines at the instrumental resolution. For HARPS, the FWHM is close to 3 km s−1 and therefore requires a minimum equivalent BERV span coverage.

To perform our first level correction by CCF moments, a master stellar spectrum free of telluric lines is built by a masked median of the spectral time series, where a mask fixed in the BERV rest frame is applied to hide the telluric lines according to our database. The binary mask of water telluric lines is used to compute the CCF of the spectral time series divided by the master spectrum. All the lines of the mask have the same weight, meaning that the obtained CCF can be seen as an average telluric line. Since its equivalent width (EW) can be interpreted as a proxy for water column density, this later is at first order proportional to the flux correction to apply. We note that a similar flux corrections is applied in Leet et al. (2019) with the SELENITE code, where the modelled correction is using as prior information both precipitable water vapour content and airmass.

To correct for telluric contamination, we shifted the ratio spectra in the BERV rest frame and performed a multi-linear regression (see Eq. (1)) by fitting both the contrast and FWHM time series of the telluric CCFs on each wavelength column. The correction was performed only if the Pearson coefficient between the flux column and the contrast or the FWHM was higher than 0.4. We note that telluric CCFs can still be contaminated by stellar lines and their moments can therefore be corrupted. This can fortunately be detected as a mismatch between the telluric CCF RV and the BERV. When those two quantities were diverging by more than 1 km s−1, we replaced the value of every moment by the median of the corresponding time series.

After performing this first correction, residuals were visible in telluric line cores, in particular at times where the telluric CCFs were really deep, which can be interpreted as a non-linear behaviour of water lines when the humidity content in the atmosphere is too high. We then decided to apply a second correction based on a weighted PCA4 (Bailey 2012). We performed a PCA on the previous residual matrix at the locations of clear telluric detection, which is estimated to be telluric deeper than 0.08% (see Appendix A). The PCA was weighted by the inverse of the flux uncertainty squared in order to prevent biasing the PCA algorithm with unusual low S/N observational epochs. The obtained PCA vectors were then fitted on each wavelength column of ratio spectra (see Eq. (1)). Only the three first principal components were fitted as adding more components did not reduce the variance further. The modelled telluric time series was extracted by taking the difference between the raw ratio spectral time series (in the terrestrial rest frame) and the residuals after CCF moments and PCA components fitted. The telluric time-series model was then shifted back in the stellar rest frame and use to correct the ratio time series. The corrected spectra, in classical flux units, were recovered by multiplying the corrected ratio time series by the telluric-free spectrum f0(λj).

The spectral time series after this cleaning process can be seen in the lower panel of Fig. 2 and we observe that the adopted methodology successfully remove telluric contamination at the precision level of around 0.21%. The second stage of correction can be seen as a refinement of the telluric correction and will mainly correct for residuals let by the first stage correction. This can be appreciated on the individual components extraction performed on HD 10700 (see Sect. 3.1) for which the RV amplitude of the second stage correction is one order of magnitude lower.

The same approach was used to correct for oxygen lines. On a final note, the method described here will certainly fail in the infrared where the lines density of water is too high. A possible solution would be to perform a first order correction by telluric lines modelling (Seifahrt et al. 2010; Ulmer-Moll et al. 2019) before applying the PCA as a second-stage correction on the residuals.

2.5. Point spread function variation and activity corrections

The stellar CCF moments, such as the bisector inverse slope (BIS), the FWHM, the contrast, and the EW, have been widely used in the past to probe stellar activity (e.g., Queloz et al. 2001; Povich et al. 2001; Boisse et al. 2011). In particular, since those moments are known to contain no Doppler information, they are still frequently used nowadays, to highlight power excess or deficit at specific periods in periodograms, when the purpose is to assess the nature of periodic signals. The CCF can be seen as a weighted average stellar line and its variation therefore represents the average behaviour of stellar lines. In the context of stellar activity, several works have shown that photospheric lines were changing in morphology due to stellar activity (Stenflo & Lindegren 1977; Cavallini et al. 1985; Basri et al. 1989; Brandt & Solanki 1990; Berdyugina & Usoskin 2003; Anderson et al. 2010; Thompson et al. 2017; Dumusque 2018; Wise et al. 2018; Ning et al. 2019; Löhner-Böttcher et al. 2019). In Cretignier et al. (2020a), we demonstrated how even symmetrical flux variations, which should a priori not induce an RV variation, can still introduce an RV effect if the line profile is asymmetric, such as in the case of a blended line (see also Reiners et al. 2013).

We note that in this paper we do not use the information of the CCF moments to correct for stellar activity; as for the quiet stars that will be presented in Sect. 3, no excess power is visible in any activity proxy, and thus stellar activity is not an issue. CCF moments that are tracing line-shape variations unrelated to Doppler shift (namely contrast and FWHM) can be used to probe and correct the variations in the instrumental PSF. To do so, we used an approach similar to the first-stage tellurics correction (see Sect. 2.4), except that the spectra are analysed in the stellar rest frame and spectra differences are used instead of spectra ratio as for tellurics. The stellar CCFs are extracted from the G2 or K5 CCF mask of HARPS depending on the stellar spectral type and a multi-linear regression (see Eq. (1)) of the contrast, the FWHM and the CaII S-index is fitted on each wavelength column.

The advantage of simultaneously fitting the S-index and moments of the CCFs is that whereas the former should only contain stellar activity effects, the latter can simultaneously contain instrumental and stellar activity components. Fitting all of them therefore leads to lifting the potential degeneracies that may exist. We can wonder if the fit in the flux of the S-index is motivated. Despite the higher sensitivity of the CaII H&K lines to active regions, it is known that all photospheric lines change in depth with stellar activity (Basri et al. 1989). Even if photospheric and chromospheric variations can differ due to their different formation layers, several deep broad lines are also formed in the chromosphere as the CaII lines and will therefore undergoes similar variation with different strengths. This is confirmed in Fig. 3 where we represented the five years of observations of α Cen B and the correlations of each wavelength column with the S-index. Several wavelength columns show a significant correlation (ℛ > 0.4) with the S-index. The modifications observed are equivalent to line core filling and line width broadening, which are effects already known from stellar activity on the 2010 dataset (Thompson et al. 2017; Wise et al. 2018; Ning et al. 2019; Cretignier et al. 2020a). We do not investigate further stellar activity since such an analysis is left for a future dedicated paper and the targets selected hereafter are quiet stars.

|

Fig. 3. Illustration of the flux variations induced by stellar activity on α Cen B and its correlation with the S-index on a small wavelength range in the extreme blue. Bottom: master normalised spectrum of α Cen B. Middle: river diagram of the five years of alpha Cen B observations. Some lines clearly show long trend flux variations corresponding to the magnetic cycle of the star. Top: Pearson correlation between the flux variations and the S-index showing, for several wavelengths, a significant correlation with |ℛPearson| > 0.4 (red horizontal lines). Such correlations were already reported by previous studies for the 2010 dataset, such as Thompson et al. (2017), Wise et al. (2018), Ning et al. (2019), and Cretignier et al. (2020a). The 2010 observational season is equivalent to index 102–150 on the figure, for which the rotational modulation is clearly visible. |

It is important to mention that CaII H&K lines can be contaminated by ghosts (see Sect. 2.6), which are not yet corrected for at that moment. Hopefully for HARPS, as demonstrated in Appendix B, ghosts never fall simultaneously on the CaII H and CaII K lines. In addition, the contamination depends on the systemic RV (RVsys) of the observed star that will shift the spectra and thus the position of the cores of the CaII H&K lines relative to ghosts that are fixed in the barycentric rest frame. Since both chromospheric lines react in a similar way, the activity proxy that we fit will be made of either one line (CaIIH or CaIIK) or both combined (S-index), depending on the RVsys of each star (see Fig. B.1). For an instrument strongly contaminated by ghosts, a careful extraction of the S-index should be performed (Dumusque et al. 2021).

When analysing the data of the extremely quiet star HD 10700, it is possible to observe the change of HARPS’s focus as a function of time, which is associated with the ageing of the instrument. Indeed, the CCF FWHM (top left panel of Fig. 4) and the contrast show a net increase and decrease with time, respectively. This is coherent with a slight decrease in the HARPS resolution with time, equivalent to a PSF broadening. The EW, which is at first order the product of the FWHM and the contrast, does not show such a long-term trend. It is, however, relevant to note that the FWHM variation observed is only about 1 m s−1 per year. It confirms the remarkable stability of the instrument along its lifetime, as well as the incredible stability of the star itself.

|

Fig. 4. Visualisation of the focus change due to HARPS ageing on the CCF FWHM and RV time series of HD 10700 obtained with the HARPS G2 mask. Top left: CCF FWHM time series of HD 10700. The star is known to be extremely quiet and the long-term trend observed is likely induced by the instrument ageing. The linear trend is about 1 m s−1 year−1, which proves the impressive stability of HARPS (and HD 10700) over a decade. A similar though decreasing trend is observed in the CCF contrast. Bottom left: RV difference obtained on the RV before and after applying the YARARA correction to the spectral time series. YARARA allows a long-term linear drift of 10 cm s−1 year−1 to be suppressed. Right: correlation plot of the previous time series, which shows the strong dependence between those two quantities, with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.82. The 21 cm s−1 rms that we can see in the residuals can be explained by the simultaneous fit of the CCF contrast and CaII S-index along with the FWHM or bad fit on some wavelength columns. |

To measure the RV impact of the instrument ageing, we computed the RV before and after applying the flux correction using the HARPS G2 cross-correlation mask and measured the difference between both RV time series. This difference is displayed in the bottom left panel of Fig. 4 and is strongly correlated with the FWHM variation as we can see in the right panel of the same figure, with a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.81. The RV impact of the instrument ageing is extremely small, with a linear slope of only 10 cm s−1 year−1. We note that even if such a linear correlation between FWHM and RV can theoretically be used to correct for instrumental ageing on the RV time series, correcting for the effect at the flux level is a more robust way of handling this issue.

2.6. Ghosts correction

Ghosts are spurious reflections of the physical orders occurring inside the instrument, which produce tilted-duplicated images of the spectral orders on the CCD. Due to their reflection nature, ghosts are at maximum a hundred times less luminous than the original echelle orders, as measured on a master FLAT raw frame (see Fig. 5). As a consequence, ghosts are difficult to distinguish from the read-out-noise of the detector on individual calibration frames, and no calibration frames can be produced to highlight ‘only’ ghosts since those are secondary reflection of the main echelle orders. However, ghosts always appear at the same position on the detector and can thus be highlighted on high S/N images obtained after stacking several raw frames together. As an example, we show on the left panel of Fig. 5 an image obtained after stacking two months of HARPS FLAT calibrations raw frames and we clearly see the contamination induced by ghosts as oblique bright lines.

|

Fig. 5. Derivation of the static product used in the fourth flux correction performed by YARARA dedicated to ghosts contamination. Left: master raw image of the blue detector obtained after stacking two months of FLAT calibration frames when only the science fibre was illuminated. The echelle spectrograph orders are the vertical parabola, which are masked here to highlight the ghosts visible in the background. Middle: ghosts as fitted by our models. Right: map of ghost contamination indicating the location of the ghost of the science fibre on itself. Bright colour highlights the intersection of the ghosts with the physical orders. A similar map was derived for the ghosts of the simultaneous calibration fibre crossing the order of the science fibre. |

The ghosts’ contamination is not corrected in the HARPS DRS because it is difficult to deal with it at the extraction level due to the relative small angle between ghosts and the main echelle orders, but mainly because when observing a star, the ghosts will be a copy of the stellar spectrum itself, and not the ‘flat’ spectrum of a tungsten lamp used for flat-fielding. To our knowledge, no study on HARPS has analysed to which main echelle orders the ghosts belong, thus making any correction extremely difficult.

A proper way of correcting for ghost contamination in the context of RV measurements was never investigated further as ghosts only contaminate spectral regions with very low flux, such as the extreme blue in the stellar observation, and those regions do not contribute significantly to the extracted RVs. However, ghosts can significantly contaminate the cores of the CaII H&K lines in the extreme blue, at 3834 and 3969 Å, which are used to derive the calcium activity S-index, the main stellar activity indicator for G-K dwarfs (Wilson & Vainu Bappu 1957; Oranje 1983; Baliunas et al. 1988). This is the case in the HARPS-N solar observation, where a ghost correction technique was performed to derive a calcium activity index free of contamination (see Dumusque et al. 2021).

To be able to derive a calcium activity index free of systematics, but also to obtain meaningful LBL RV information in the extreme blue, we decided to correct for ghost contamination at the flux level with YARARA. The first step consists in modelling the ghosts on the raw frames (middle panel) in order to determine their intersection with the science orders (right panel). The modelling of ghosts is detailed in Appendix B. To obtain the wavelengths of a spectrum that are contaminated by ghosts, we took advantage of the HARPS instrumental stability, which allows us to use a static wavelength solution to map contamination from pixels to wavelengths. As the contamination is additive, we looked for the contamination in spectrum difference time series, obtained by subtracting to each spectrum a master built as the median of all spectra. The river diagram map of spectrum differences shifted in the BERV rest frame is displayed in the top panel of Fig. 6. Around 3819 and 3849 Å, we see ghost contamination from the science fibre (fibre A), and around 3822 and 3851 Å, ghost contamination from the reference fibre (fibre B). We then selected, at the location of ghost crossings, all the wavelength that where showing a relative flux variation more important that 1% and trained a weighted PCA (Bailey 2012) to model the ghost contamination. Finally, we fitted for all the wavelengths columns located in a ghost crossing region, the first three PCA components for ghosts of fibre A and the first two for ghosts of fibre B (see Eq. (1)).

|

Fig. 6. Ghost, thorium-argon, and continuum corrections performed by YARARA on HD 10700. The river diagram is produced in the BERV rest frame. Top: spectral time series before YARARA corrections. Spectra suffer from thorium-argon contamination (bright vertical lines, for example close to 3840 Å) and Fabry-Pérot contamination by a ghost of the simultaneous calibration fibre (vertical bright comb around 3822 and 3851 Å). The strong contamination around 3819 and 3849 Å is due to two ghosts of the science fibre. Middle: model of the contamination fitted by YARARA. Bottom: residual river diagram after YARARA correction. |

We note that around 3819 and 3849 Å, the ghost contamination of fibre A presents an emission/absorption pattern, which is unexpected. Naively, we would only expect an emission, such as for thorium-argon contamination, but on a much larger region (see the top panel of Fig. 6 and Sect. 2.8). As this is not the case, one explanation is that the master spectrum subtracted is not free of ghosts. Indeed, since ghosts cross the orders with a small penetration angle (∼5°), their contamination is present over about one hundred pixels. In consequence, even if the star studied present large BERV values (at maximum ∼60 km s−1, thus 73 HARPS pixels, as a pixel is ∼820 m s−1), significant wavelength ranges are always contaminated by ghosts. An option would be to optimise the way the reference master is built; however, such a solution will not work for stars with a small span in BERV. It is important to note that this issue will provide an inaccurate correction though one that is still very precise, which is the important factor when deriving RVs. The same problem does not occur for ghost contamination of fibre B since this fibre is illuminated by either a thorium-argon lamp or a Fabry-Pérot etalon, both of which present distinct emission peaks and not a continuous emission, unlike the ghosts of fibre A, which are reflections of a stellar spectrum. This explains why we fitted the first three PCA components for fibre A, and only the first two for fibre B.

The principal component model of ghost contamination from fibre B clearly captures the Fabry-Pérot structure as visible by the emission comb around 3822 and 3851 Å in the middle panel of Fig. 6. This structure is only visible once the Fabry-Pérot has been routinely used on HARPS, which happened in 2012. We can see a few remaining residuals in the lower panel of the same figure inside the ghost A regions, which appear as dark lines perfectly phase-folded at one sidereal year. Those lines are the stellar lines of the ghosts contaminating the science fibre. Since both the ghost stellar lines and the science stellar lines are shifted with the BERV, those lines are not fixed in the BERV rest frame and determining their rest frame is out of the scope of the present paper.

Although ghost contamination is strongly mitigated after YARARA correction, the structured residuals could still impact the RV of spectral lines appearing in the contaminated regions. We will see that those residuals impact the derived RV of spectral line in a characteristic way different from a Doppler shift, and we correct for those at a later stage (see Sect. 2.11).

2.7. Stitching correction

Stitching are detector systematics induced when manufacturing a CCD. The HARPS 4096 × 4096 CCD is a mosaic composed of eight blocks of 512 × 1024 pixels, which are not perfectly aligned together. The pixels located at the stitching of the different blocks have a different size than the pixels within blocks, due to manufacturing limitation. If not properly accounted for when extracting spectra and measuring a wavelength solution, this difference in size will induce an RV variation at a period of one year, as first shown by Dumusque et al. (2015). In this paper, the authors strongly mitigate the induced one-year signal by simply rejecting from the RV computation the part of the spectrum affected by the stitching effect. However, this rejects a significant amount of RV information, and a better way to handle this problem is to measure the size of the pixels at the different stitching location and include it in the wavelength solution derivation (Coffinet et al. 2019). We will see below that stitching effect can also be efficiently corrected for at the flux level.

In Fig. 7, we display the same stitching-crossing stellar line at 6200 Å for HD 128621 as reported in Dumusque et al. (2015). The left panel show the flux anomaly created by the wrong wavelength solution at the stitching position before and after YARARA correction. We note that the time dimension in those river diagram maps is phase-folded at one year. The right panel of the same figure show the LBL RV of the 6200 Å spectral line, phase-folded at 1 year, before and after YARARA correction. It is clear that before correction the RV of the line shows a sigmoid-like shape variation, with a jump of 40 m s−1 between phases where the stitching is on both sides of the spectral line. From the left panel of Fig. 7, we can see that for each wavelength columns, the effect in flux is a step function, where the position of the step correspond to the stitching location. Instead of fitting for a step function that could be biased by outliers, we computed the median below and above the stitching boundary for each wavelength column crossing a stitching and subtracted this model. We clearly see that the stitching flux anomaly is strongly mitigated in the river diagram map residuals. When deriving the LBL RV of the 6200 Å spectral line using the spectra corrected from YARARA, the original 19.4 m s−1 RV rms of the line is strongly reduced down to 6.6 m s−1. As in the case of ghost contamination, the remaining small residuals can be corrected further when studying the LBL RVs as the induced effect will be different from a Doppler shift. Performing LBL morphological corrections (see Sect. 2.11) manages to correct the systematic down to an rms of 5.6 m s−1.

|

Fig. 7. Stitching correction performed by YARARA on the five years of HD 128621 data for the 6200 Å stellar line described in Dumusque et al. (2015). The time dimension is phase-folded at 1 year. Top left: spectral time series before YARARA corrections. The position of the stitching is indicated by the black curve and is used to mark the delimitation of the step function used for correction (see text). Bottom left: same as top left but after YARARA processing. Top right: LBL RV of the line crossing the stitching. Colour encodes the unfolded time. Bottom right: same as top right but after YARARA processing. The RV rms has been reduced from 19.4 m s−1 down to 6.6 m s−1. The LBL morphological correction (see Sect. 2.11) mitigates the rms even further, down to 5.6 m s−1. |

2.8. Thorium-argon correction

A thorium-argon lamp was used on HARPS (before the use of the Fabry-Pérot etalon Wildi et al. 2011) as a reference calibrator to measure the drift of the instrument throughout the night. To do so, the light from the thorium-argon lamp was injected in the reference fibre (fibre B) of the spectrograph, to simultaneously measure the instrumental drift along with stellar observations. During a stellar observation, the reference thorium-argon spectrum on fibre B presents, however, a significant number of saturated lines that ‘bleed’ on the detector and contaminate the nearby science fibre. Lowering the flux of the lamp to avoid saturation is not an option, unfortunately, as otherwise the S/N of the Thorium spectrum would not be sufficient to reach the precision required to measure the tiny drifts of the spectrograph overnight.

The HARPS DRS corrects for this effect by using thorium-argon contamination calibrations. Those calibrations have only fibre B illuminated by the thorium-argon lamp. The contamination of the lamp at the position of the science fibre is extracted and then fitted for in stellar observations. Unfortunately, these calibration frames were only rarely produced on HARPS, which implies an imperfect correction as line intensities change with time due to the ageing of the lamp or due to a change of lamp, which happened a couple of times throughout HARPS’s lifetime5. We can clearly see at wavelengths 3837 Å and 3841 Å in Fig. 5 that the use of static contamination products do not provide an excellent correction.

To perform a better correction, we first used the available thorium-argon contamination calibrations to select the spectral regions contaminated by saturated lines. We used a 1.5 interquartile (IQ) sigma-clipping to detect anomalous flux intensities compared to the noise level. The IQ being more robust statistically to detect outliers (Upton & Cook 1996). We then trained a weighted PCA on the selected wavelength columns in the BERV rest frame, and corrected for the contamination by fitting the first two PCA components on all the wavelength columns. We decided to fit the model on the full wavelength domain instead of on flagged regions, like for ghosts, since detecting the contamination in the calibrations frames is difficult. To prevent the first two PCA components and to fit for any type of systematics, we performed the correction only if the Pearson coefficient with one of either PCA vector was higher than 0.4.

2.9. Continuum improvement and iterative processing

So far, a recipe has always built its own master spectrum to be as free as possible from the contamination it was correcting for. Since spectra at the end of the pipeline are cleared at best of all the observed systematics, the final master spectrum is necessarily better that the one available at the beginning of the pipeline. For that reason, a second iteration trough the different recipes by using always the master spectrum obtained at the end of the first iteration is performed. As an example, the first correction that benefits from the new master spectrum is the Savitchy-Golay continuum fit performed in RASSINE. Indeed, since telluric lines are initially not corrected for, they induce a poor continuum normalisation around telluric bands.

After the second iteration, no significant flux variation is remaining in the river diagram maps, except small residuals at ghost crossing and a few outliers. To get rid of these remaining systematics, we finally perform a 2-sigma clipping on each wavelength columns and replace outliers by the median value of the corresponding wavelength column, as done for cosmic correction (see Sect. 2.2), with the exception that no condition on the flux level is imposed.

2.10. Stellar mask optimisation and LBL RVs

YARARA was developed to locally extract the RV information in a stellar spectrum, as done in Dumusque (2018). One of the final purposes of the pipeline is to produce better LBL RVs since spectra are precisely normalised thanks to RASSINE and spectra are cleared out of their main contaminations. A great advantage after YARARA post-processing is that the available master spectrum is expected to be almost completely free of all known contaminations. Such a master can thus be used to perform cross-correlation and derive an RV value per spectrum (Anglada-Escudé & Butler 2012; Gao et al. 2016; Zechmeister et al. 2020), or derive LBL RVs.

LBL RV extraction by first order flux linearisation (Bouchy et al. 2001) only requires three quantities: (1) a master template used to measure the flux variation δf between a spectrum and the master, (2) the line profile gradient ∂f/∂λ to account properly for the weighting of the RV information and (3) the window centred on a spectral line to extract its RV signals. A few surprising results can be found if a generic mask is used instead of a tailored line selection in LBL RV analysis. Indeed, due to blended lines that are in some way unique for each star depending on the stellar temperature, metallicity, vsin(i) or instrumental resolution, a generic mask will in some case produce spurious RV signals, which was demonstrated in Cretignier et al. (2020a). We note that similarly to Dumusque (2018) and Cretignier et al. (2020a), Lafarga et al. (2020) showed that tailored lines selections, produced by their public code RACCOON, can be useful to boost the S/N and decrease the photon noise, which produces in general better RV precision.

We implemented in YARARA a similar line window selection as described in Cretignier et al. (2020a). This consists simply in selecting for each line, the wavelength range between the two local maxima surrounding the local minimum formed by the line core defined as the local minimum. Doing so, blended lines will sometimes be grouped together but this is not an issue as soon as signals specific to each line profile do not try to be interpreted Cretignier et al. (2020a). We note that the obtained selection of lines does not exclude spectral regions strongly contaminated by telluric lines, as commonly performed by generic line masks, and therefore the line selection of YARARA can be used to extract RV information with the highest S/N.

If we want to use the obtained line selection as a mask for performing cross-correlation, we need to obtain the proper depth of the line relative to the continuum as this is used as weight when deriving the CCF (Pepe et al. 2002b). In addition, if we want to derive LBL RVs using this line selection, we also need to estimate at best the continuum and depth of the spectral lines as the LBL technique uses the line profile gradient ∂f/∂λ as weight. In regions where a continuum exists, the normalisation by RASSINE allows the proper estimate for the continuum and line depth to be derived. However, this is no longer the case in the blue part of solar-like spectra or in the spectra of M-dwarfs as no continuum exists due to the strong absorption. This problem is solved by measuring the deviation of the estimated RASSINE continuum with respect to a stellar template close to the effective temperature of the star, and correcting for it, as shown in (Cretignier et al. 2020b). As an example, we shown in Appendix C and Fig. C.1, the YARARA correction for continuum opacity in the stellar spectrum of an M1.5 dwarf.

2.11. LBL morphological corrections

All the previous corrections managed at some level to remove efficiently the different observed contaminations. In some cases, however, we noticed that some residual signals were still present. Those are due to (1) degeneracies between the recipes, which typically occurs when several contaminations are located at the same wavelength position, (2) more complex patterns, such as the ones created when ghosts contaminate stellar line (see Sect. 2.6), and (3) regions not flagged by our static products. Unlike a Doppler shift, those residuals will change the shape of spectral lines with time, which can be tracked and corrected for using a few metrics that describe line morphology.

We extracted three morphological parameters to measure a change in the line profile not related to a Doppler shift. We first separate the left and right wing of a spectral line with respect to its core defined as the local minimum of the line, and then measure the total flux on the left (L) and right (R) wings. We then build the L+R and L−R metrics to account for asymmetric variations. Our third parameter is the depth of the stellar line, fitted by a parabola on the line core with a window of ±2 kms.

Although a Doppler shift does not affect the line depth, it does affect L and R, and thus our metrics L+R and L−R. To correct for Doppler shift variation, we built a calibration curve for each stellar line in our line selection. To do so, we shifted all the spectral line with values ranging from −100 to 100 m s−1 by step of 0.5 m s−1 and measured for each of them how L−R and L+R behaved. We then linearly interpolated each relation on a finest grid of 1 cm s−1. Once we have those calibration curves, the L+R and L−R metrics for a given spectral line can be obtained by (1) deriving its LBL RV, (2) read on its calibration curve the L−R and L+R values for this RV and (3) measuring the difference between the measured and theoretical values. By doing this calibration and correction, we ensure that our morphological proxies L+R and L−R are planetary-free. We demonstrated in Sect. 3 that neither known planets, nor injected ones, disappeared at the end of our pipeline, which is a first validation of the method.

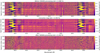

Those morphological parameters, phase-folded with a period of 1-year, are represented in Fig. 8 for the stellar line at 3849 Å in HD 10700 HARPS observations. This line was clearly showing residuals after ghost correction in Fig. 5. By observing the LBL RV, after flux correction (bottom centre panel), several ‘mountain peaks’ are clear visible, a signature coherent with several flux anomalies crossing the stellar line. Because this variation is not equivalent to a pure Doppler shift, the same pattern can be observed in the L−R proxy (top centre panel). By linearly decorrelating the LBL with the three morphological proxies, the RV contamination still remaining after YARARA flux correction is highly reduced. We note that for this line, the RV rms is mitigated from 22.1 to 17.3 m s−1 after YARARA flux correction, and down to 8.1 m s−1 after LBL morphological correction.

|

Fig. 8. Morphological corrections performed by YARARA on HARPS observations of HD 10700 for the 3849 Å line contaminated by a ghost of the science fibre. The time dimension was phase-folded at one sidereal year. Top left: L+R area deviation with respect to the Doppler shift calibration curve (see main text for the precise definition), which is therefore similar to its EW. Top middle: L−R area deviation with respect to the Doppler shift calibration curve. Top right: line depth of the line computed by a parabola fitting on the line core. Bottom left: LBL RV of the line before any correction. Bottom middle: LBL RV after YARARA flux corrections. The stellar lines present in the ghost are still visible. Bottom right: LBL RV after multi-linear de-correlation with the three morphological proxies. The 8.1 m s−1 rms of the RV residuals is compatible with the median of the RV uncertainties. |

The same morphological correction was systematically applied for all of the 3770 stellar lines in our line selection for HD 10700. We displayed in Fig. 9 how such a correction is helpful to correct for 1-year period contaminations. We fitted a 1-year sinusoid on each LBL RV and studied the correlation between the time series and the best-fitted model. In the different panels of this figure we show, for each line, the weighted Pearson correlation coefficient between the LBL RVs and the fitted sinusoid as a radial coordinate as well as the phase of the fitted sinusoid as a polar coordinate. The colour represents the semi-amplitude of the fitted sinusoid. We defined a line as significantly affected if its power exceeds a false alarm probability (FAP) level of 1% at 365.25 days. We see in Fig. 9 that before any correction is applied (top left panel), 1071 stellar lines exhibit a significant 1-year power, some of them with semi-amplitudes larger than 10 m s−1. The third quartile (Q3) of the amplitude distribution is 9.1 m s−1. Despite the large number of lines contaminated, it is important to highlight that since the phases between all the signals are not coherent, the final amplitude of the contamination is roughly of 1 m s−1. Those lines can be contaminated by any effect fixed in the BERV rest frame, in our case tellurics, stitchings, ghosts or thorium-argon contaminations. Those contaminations should be significantly mitigated after YARARA flux correction (top right panel), which is indeed the case as only 428 stellar lines still present a significant 1-year signal after flux correction, and Q3 is reduced down to 5.36 m s−1. After morphological LBL correction, the number of significantly affected lines drops to 227 and Q3 to 3.2 m s−1. Figure 9 therefore highlights that YARARA, through flux and line morphology corrections, is able to strongly mitigate instrumental systematics with a one-year period.

|

Fig. 9. Polar periodogram representation of LBL RV time series for HD 10700. The polar periodogram is focused at 1 year and represents the Pearson coefficient with a 1-year sinusoid as radial coordinates (see the main text) and the phase of the signal as the polar angle. Among the 3770 stellar lines, the numbers of lines presenting a Pearson coefficient higher than 0.4 are, respectively from top left to bottom right: 339, 59, 15 and 0. Top left: input dataset without any YARARA correction. Top right: dataset after YARARA flux correction. Bottom left: dataset after the LBL morphological corrections. Bottom right: dataset after lines with a significant 1-year power are rejected. Most of the 1-year-affected lines have been cleaned out. |

The 227 spectral lines that are still affected are so far not understood. After investigations, no particular instrumental systematics are expected on the detector at their positions. Also, since their contamination is not corrected for by our morphological correction, it indicates that the flux contamination is too low to be detected by our morphological proxies. It is further confirmed by the observation that such remaining 1-year lines are not found after flux corrections for HD 215152 for which the median S/N of the spectral time series (S/N ∼ 120) is ten times lower than for HD 10700 (S/N ∼ 1000). We note that when fitting for ghosts localisation on the high S/N master FLAT, some barely visible ghosts were excluded as considered as negligible (see Appendix B). Those could therefore be responsible for the remaining affected spectral lines.

To remove from our final selection part of those 227 contaminated lines, we proceed as followed. All the lines presenting a power at 1-year higher than a FAP level of 1% are first removed and the average RV signal RVm of the complementary lines’ selection is computed. This RVm signal was then subtracted in each individual LBL RVs, in order to remove any real planetary signal if any, before redetermining the power at 1-year for each individual line. The motivation behind subtracting RVm is to prevent absorbing any real planetary signal appearing at a period of 1-year or corresponding harmonics (see the planetary injection simulation performed in Sect. 3.1). Lines with a 1-year power higher than 1% FAP level are removed such that only 103 lines still present significant 1-year power for HD 10700 and Q3 is decreased down to 2.5 m s−1 (bottom right panel). This line rejection step is performed by the pipeline for all the stars, but only stars with exquisite S/N, such as HD 10700, will have some lines rejected, generally fewer than a hundred lines.

An explanation for that remaining 1-year signal is the inaccurate wavelength solution due to the sparse location of thorium-argon lines and their uncertainties on their absolute wavelength values. In Coffinet et al. (2019), the authors showed that echelle-order wavelength solution by polynomial fit were inaccurate by dozens m s−1 compared to the wavelength solution obtained with a laser frequency comb. The inaccurate wavelength solution will at term introduce systematics at 1-year of small amplitudes on LBL RVs since the BERV will move the stellar lines on this inaccurate wavelength solution. Opposite to ghosts, all the lines will be in phase with the BERV. This seems to be observed on the bottom right panel of Fig. 9 by an elongation of the cloud along the 45° direction, which is almost consistent with the BERV phase of 30° that we can obtain by doing a similar analysis not shown here. Due to the small amplitudes of the signals expected (< 5 m s−1 from the LBL RVs), it is rather hard to confirm this hypothesis.

More sophisticated LBL RV corrections could be developed from this point, but those will be described in a forthcoming paper dedicated to stellar activity correction. For now, this stage is representing the ending point of our pipeline. Its application to several HARPS targets is presented in the next section.

3. Results

In this section, we analysed the data of three stars intensively observed with HARPS, to test the performances of YARARA. We first looked at the data of HD 10700 in Sect. 3.1 as it appears to be the quietest star in the entire HARPS sample, with an RV rms close to 1 m s−1 over more than a decade. We compared the RVs obtained after YARARA processing, with the ones from the classical HARPS DRS and the SERVAL post-processing pipeline (Zechmeister et al. 2020; Trifonov et al. 2020). As this star does not show any significant planetary signal, we also injected a fake planetary signal to demonstrate that YARARA processing was not altering planetary signals. We then analysed HD 215152 in Sect. 3.2, to demonstrate that YARARA strongly mitigate the impact of yearly signals induced in this dataset mainly by detector stitchings. Finally, we studied HD 10180 in Sect. 3.3 that is known to harbour six planets. We show that all the planets are recovered with high confidence after YARARA processing, and the obtain orbital parameters are similar with the published values, however, with some interesting differences.

3.1. HD 10700

We used HD 10700 as a star of reference to perform pipeline performance comparison and a planetary injection test. This star is known to be a particular inactive star maybe in a state similar to the Maunder minimum for the Sun (Lovis et al. 2011a). On 13 years of HARPS observations, the RV rms is observed to be 1.27 m s−1, which is an impressive proof of stellar and instrumental stability. Moreover, this system has been intensively followed by HARPS and contains no confirmed planet but only possible candidates with RV amplitudes lower than 1 m s−1, even if no agreement was found between different analyses (Pepe et al. 2011; Tuomi et al. 2013; Feng et al. 2017).

We first compared the publicly available RVs obtained with the SERVAL post-processing pipeline (Trifonov et al. 2020; Zechmeister et al. 2020) with the ones obtained by the HARPS DRS in Fig. 10. We note that in the publicly available SERVAL RVs, two different products are available. RVs computed using a stellar template matching technique, and the same RVs but corrected for night-to-night calibration offsets (e.g., Dumusque 2018) measured on the time series of several quiet stars. To have a fair comparison with the DRS RVs, we considered the SERVAL RVs without night-to-night offset correction. We see that for HD 10700, SERVAL does not performs as well as the DRS, with an RV rms over the entire time series of 1.36 compared to 1.27 m s−1, and the RV rms for each season being higher than for the DRS for the data before the change of the HARPS fibres in 2015 (Lo Curto et al. 2015). SERVAL is performing best after the fibre upgrade of the instrument. In addition, while SERVAL seems to slightly remove some signals with periods longer than a hundred days, it seems that more signals are present between 40 and 100 days, which is worrisome. It is clear from the Trifonov et al. (2020) paper that SERVAL performs better than the DRS for M-dwarfs since the stellar template-matching approach used by SERVAL is known to work better for these stars (Anglada-Escudé & Butler 2012). However, the Trifonov et al. (2020) paper does not asses the performance of the code with respect to spectral type, and this example shows that for G dwarfs, SERVAL does not necessarily outperform the DRS.

|

Fig. 10. Comparison between different reduction pipelines for 13 years of HD 10700 HARPS observations. First row: comparison between the SERVAL post-processing pipeline (without night-to-night offset correction; Trifonov et al. 2020; Zechmeister et al. 2020) time series (blue dots) and HARPS DRS (green dots). The weighted rms are indicated for each observational season as well as for the full time series in the title. The HARPS DRS time series present a significantly lower rms in each season before the fibre upgrade (vertical dotted line), whereas the opposite conclusion holds for SERVAL after the upgrade. Second row: GLS periodogram of the SERVAL time series. The 1% FAP level is indicated by the dotted-dashed line. Third row: same as the middle row but for HARPS DRS extracted time series. |

We then compared the SERVAL RVs with the ones obtained by YARARA. As YARARA works with nightly binned spectra, and thus RVs, we nightly binned the SERVAL data to perform the comparison. Two nights were clearly outliers in SERVAL reprocessed data, so we removed them in both datasets. In this case, to perform a fair comparison, we took the SERVAL RVs with the night-to-night offset correction applied. As seen in Fig. 11, correcting for the night-to-night offset significantly improves the SERVAL RVs in term of rms (1.13 m s−1); however, the forest of peaks between 40 and 100 days is still present. In comparison, the global RV rms is reduced down to 1.02 m s−1 after YARARA processing, which is equivalent to a quadratic difference improvement of 0.77 m s−1 compared to the HARPS DRS. We highlight in Fig. 12 for HD 10700, the different contaminations corrected by YARARA to show the relative strength of each component relative to the others. We can see that most of the contaminations are peak-to-peak larger than 10 cm s−1. The dominant systematics is produced by the stitching (Dumusque et al. 2015) with 1 m s−1 peak-to-peak variation.

|

Fig. 11. Same comparison as Fig. 10, except that the comparison is now between YARARA time series (green dots) and the SERVAL post-processing pipeline (with night-to-night offset correction, blue dots) presented in Trifonov et al. (2020). The rms is lower with YARARA for all the observational seasons before the fibre upgrade. The periodogram also presents a cleaner aspect. |

|

Fig. 12. Decomposition of the individuals components corrected in YARARA for HD 10700 on HARPS. Each RV component was obtained, as in Fig. 4, by computing the RVs before and after the flux corrections of a dedicated YARARA recipe. The RVs are obtained from the tailored line selection. Systematics known to be related to 1-year systematics are time-folded. We note that systematics can be folded at one sidereal year but are not described by sinusoid, explaining why their power can leak afterwards onto others frequencies in the periodogram. Despite the moderate rms of some components, the peak-to-peak of most of them is above 10 cm s−1. |

By comparing Figs. 10 and 11, we can see that YARARA provides better individual season RV rms compared to the DRS for only half of the observational seasons, which highlights the difficulty to significantly improve the RV below 1 m s−1 on HARPS. Despite those differences, by looking at the global RV rms and the periodograms of the different time series, YARARA seems to clearly outperform SERVAL and the DRS.

YARARA seems to perform better in correcting for the different instrumental systematics, and thus give RVs with a smaller rms and that present a cleaner periodogram. However, this would be useless if YARARA processing absorbs planetary signals. To check that this was not the case, we injected into the spectra, before YARARA processing, the signature of two planets in circular orbits. A first one close the second harmonics of 1-year at 122.42 days and with an RV semi-amplitude of K = 3 m s−1, and a second one at 37.87 days with K = 2 m s−1. The first planet is equivalent to planet f in HD 10180, and since our analysis of HD 10180 (see Sect. 3.3) shows that the semi-amplitude of planet f change significantly after YARARA processing, we wanted to be sure that the recipes dealing with yearly instrumental effects were not perturbing the amplitude of planetary signals at the harmonics of a year.

To inject the planetary signals in the HD 10700 spectra, we proceeded as follows. First, we ran the HD 10700 data through YARARA, as described in Sect. 2, and we kept at each stage the contamination map. Secondly, merged 1D corrected spectra are shifted according to the planetary signals, before reintroducing the extracted contaminations. It would be wrong to simply shift the spectra still contaminated by systematics since the planetary signals would affect the instrument systematics. For example, telluric lines would not be fixed anymore in the BERV rest frame. Once the planets are properly injected in the original spectra, we ran again YARARA to check that the planetary signals are not absorbed.

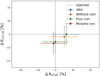

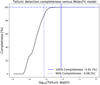

Both injected planets were found to produce the highest peak in the generalised Lomb-Scargle (GLS) periodogram as expected from the high amplitudes of the planetary signals injected. However, to validate the efficiency of YARARA in recovering planetary signal while mitigating other systematics, we needed to measure at which precision the injected planetary signals were recovered. In Fig. 13, we compare the semi-amplitude K for the best-fitted Keplerian model for the two injected planets in the following RV time series: (1) DRS (blue marker) (2) before YARARA correction (yellow marker) (3) after YARARA flux correction (green marker) and (4) after YARARA morphological corrections and lines rejection (red marker). There are few differences between the RVs of the DRS and YARARA before correction, justifying their different treatment. YARARA is working with 1D-merged spectra while the DRS starts from 1D-echelle-order spectra. In addition, the colour correction is performed differently, the lines selected for the CCF mask are different, and the cross-correlation algorithm is different.

|

Fig. 13. Planetary injection recovery in the HD 10700 dataset; comparison between the injected K semi-amplitudes (black dotted line) and the recovered ones obtained after fitting a two-sinusoid model for the planets at 37.87 (K = 2 m s−1) and 122.42 days (K = 3 m s−1). No significant absorption of the planetary signals is observed after YARARA processing, neither by flux correction (green markers) nor by morphological correction (red markers), since values similar to those without correction (orange markers) or DRS (blue markers) are found. All the recovered amplitudes are compatible with the injected values considering the uncertainty due to pre-existing signals. |

To determine an uncertainty on the semi-amplitude that could be due to pre-existing power in the time series, we fitted the same model on the DRS time series without the planet injected and reported the amplitudes of the signals as error bars. The relative uncertainties compared to the injected amplitudes is 7%.

All the planetary semi-amplitudes recovered using the different datasets are compatible with the injected values. This is expected as the corrections performed by YARARA reduce the rms by 0.29 m s−1, whereas the amplitude of the injected signals are an order of magnitude larger, 2 and 3 m s−1. We notice that after YARARA correction, we are able to recover the exact amplitude of the injected 37.87-day signal. It is not the case for the 122.42 injected planet for which a value ∼6% smaller is found. This smaller value, still compatible with the injected signal at one sigma, could be explained by the fact that the signal is at a harmonic of a year, and many different corrections in YARARA are mitigating systematics at a year. Thus, there could be small cross-talks between YARARA corrections and planetary signals close to a year or a harmonic of it. However, this test on HD 10700 shows that at most 10% in the semi-amplitude signals at one year or a harmonic of it could be absorbed by YARARA, which is in any case better than leaving perturbing yearly signals in the datasets. From this simulation of planet recovery, it seems that YARARA does not absorb significantly planetary signals in the final RV time series. Further tests on other stellar systems, presented in the next two subsections, will confirm this conclusion.

3.2. HD 215152

HD 215152 is a compact system of four planets in close-in orbits (< 30 days) and close to a resonant configuration (Delisle et al. 2018). In that paper, the authors already reported a 1-year signal present in the RV data that was interpreted as mostly induced by the stitching of the HARPS detector. In order to remove this signal, the authors removed stellar lines crossing each stitching from the CCF mask. Therefore, their strategy consisted in masking instead of correcting for the signal. In this section, we demonstrate that by applying YARARA, the perturbing one-year signal is completely mitigated without masking any spectral region, which has the advantage of improving the RV precision of the final dataset.

An interesting feature of YARARA resides in the fact that since the pipeline is applied sequentially, it is possible to quantify the RV perturbation of each contamination. To do so, the difference of the RV time series before and after the flux correction of each recipe is computed, directly providing the RV counterpart of the contamination. This method was used in Sect. 2.5 to highlight the instrument ageing on HD 10700. With YARARA, we confirm that stitchings are the main source of the one-year signal in the RV time series of HD 215152, with a peak-to-peak amplitude of 1 m s−1 as for HD 10700 (see Fig. 12).

In Fig. 14, we displayed the RV time series before and after YARARA corrections. The RV rms is decreased from 2.14 down to 1.57 m s−1 (equivalent to 1.45 m s−1 in quadratic difference). The GLS periodogram of each time-serie is showing that the 1-year signal and its first harmonic are considerably reduced whereas the power at planetary periods (5.7, 7.3 and 10.5 days) are boosted. By looking at the RV difference, a clear linear trend, induced by the stitching effect (Dumusque et al. 2015), can be observed for each season. The jitter on smaller timescales is produced by the tellurics.

|

Fig. 14. Application of the YARARA post-processing on the HD 215152 HARPS dataset. First row: comparison of the RV time series extracted with the HARPS DRS (black dots) and after YARARA processing (red dots). Second row: GLS periodogram of the previous time series. The 1% FAP level is indicated as a dotted-dashed line. Exoplanets reported in Delisle(2018) are indicated by black arrows. After YARARA processing, the power at the planetary periods (5.8, 7.3, 10.9 days) are boosted. Third row: RV difference between input and output data. fourth row: GLS periodogram of the RV difference. The removed contaminations were clearly producing most of the signals at one year and its first harmonic. |

3.3. HD 10180

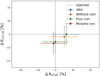

HD 10180 is a system composed of at least 6 exoplanets (Lovis et al. 2011b), with RV amplitudes larger than 1 m s−1. One of them, HD 10180 f, has a period of 122.7 days, thus very close from a harmonic of a year. We could therefore think that the 3 m s−1 amplitude of this planet is affected by the yearly HARPS detector stitching as this perturbing effect was only detected a few years later (Dumusque et al. 2015). Indeed, due to a complex interplay between real signals and data sampling, a yearly signal, such as the one induced by detector stitching, can present more power at a harmonic of a year. We therefore applied YARARA on HD 10180 HARPS observations to test if contaminating signals with one-year period can affect recovered planetary signals.

We note that a planetary candidate, HD 10180 b, was also announced in Lovis et al. (2011b), but the induced signal with a period of 1.17 days and semi-amplitude of 80 cm s−1 is not visible in our analysis, probably due to night-binning. Since the same night-binning was performed for all the datasets that we compare in this section, the existence or not of this ultra-short-period planet is not relevant here.