| Issue |

A&A

Volume 654, October 2021

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A10 | |

| Number of page(s) | 16 | |

| Section | Stellar structure and evolution | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202140781 | |

| Published online | 01 October 2021 | |

Discovery of a recurrent spectral evolutionary cycle in the ultra-luminous X-ray sources Holmberg II X–1 and NGC 5204 X–1

1

IRAP, Université de Toulouse, CNRS, CNES, 9 Avenue du Colonel Roche, 31028 Toulouse, France

e-mail: agurpidelash@irap.omp.eu

2

Department of Astronomy, Yale University, PO Box 208101, New Haven, CT 06520-8101, USA

3

Université de Strasbourg, CNRS, Observatoire Astronomique de Strasbourg, UMR 7550, 67000 Strasbourg, France

Received:

10

March

2021

Accepted:

4

June

2021

Context. Most ultra-luminous X-ray sources (ULXs) are now thought to be powered by stellar-mass compact objects accreting at super-Eddington rates. While the discovery of evolutionary cycles have marked a breakthrough in our understanding of the accretion flow changes in the sub-Eddington regime in Galactic black hole binaries, their evidence in the super-Eddington regime has so far remained elusive. However, recent circumstantial evidence hinted at the presence of a recurrent evolutionary cycle in two archetypal ULXs: Holmberg II X–1 and NGC 5204 X–1.

Aims. We aim to build on our previous work and exploit the long-term high-cadence monitoring of Swift-XRT in order to provide robust evidence of the evolutionary cycle in these two sources and investigate the main physical parameters inducing their spectral transitions.

Methods. We studied the long-term evolution of both sources using hardness-intensity diagrams (HID) and by means of Lomb–Scargle periodograms and Gaussian process modelling to look for periodic variability. We also applied a physically motivated model to the combined Chandra, XMM-Newton, NuSTAR, and Swift-XRT data of each of the source spectral states.

Results. We robustly show that both sources follow a clear and recurrent evolutionary pattern in the HID that can be characterised by the hard ultra-luminous (HUL) and soft ultra-luminous (SUL) spectral regimes, and a third state with characteristics similar to the super-soft ultra-luminous (SSUL) state. The transitions between the soft states seem consistent with aperiodic variability, as revealed by a timing analysis of the light curve of Holmberg II X–1; albeit, further investigation is warranted. The light curve of NGC 5204 X–1 shows a stable periodicity on a longer baseline of ∼200 days, possibly associated with the duration of the evolutionary cycle.

Conclusions. The similarities between both sources provide strong evidence of both systems hosting the same type of accretor and/or accretion flow geometry. We support a scenario in which the spectral changes from HUL to SUL are due to a periodic increase of the mass-transfer rate and subsequent narrowing of the opening angle of the super-critical funnel. The narrower funnel, combined with stochastic variability imprinted by the wind, might explain the rapid and aperiodic variability responsible for the SUL–SSUL spectral changes. The nature of the longer periodicity of NGC 5204 X–1 remains unclear, and robust determination of the orbital period of these sources could shed light on the nature of the periodic modulation found. Based on the similarities between the two sources, a long periodicity should be detectable in Holmberg II X–1 with future monitoring.

Key words: accretion, accretion disks / X-rays: binaries / stars: black holes / stars: neutron

© A. Gúrpide et al. 2021

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

1. Introduction

Extensive monitoring of black hole (BH) and neutron star (NS) X-ray binaries has marked a breakthrough in our understanding of the accretion flow changes driving the flux variability in the sub-Eddington regime (e.g. Done & Gierliński 2003; Remillard & McClintock 2006; Gladstone et al. 2007) thanks to the discovery of the hysteresis cycles. For instance, the discovery of the hysteresis cycle or ‘q-shape’ diagram found in BH X-ray Binaries (BHXBs; e.g. Fender et al. 2004; Belloni 2010) has allowed us to build a coherent picture of the physical changes in the accretion flow responsible for the multi-wavelength observational properties of each spectral state (associated with the presence or absence of radio jet emission, for instance). The importance of such evolutionary tracks is such that it is still used as a tool to identify accreting stellar-mass BHs today (e.g. Zhang et al. 2020). For the same reason, the spectral changes observed in HLX-1 (Farrell et al. 2009; Godet et al. 2009; Servillat et al. 2011), reminiscent of those observed in BHXBs but at three orders of magnitude higher in luminosity, remain one of the most compelling arguments in favour of the system harbouring an accreting intermediate-mass BH (IMBH: ∼100−105 M⊙; see Mezcua 2017, for a review).

At the same time, it was the atypical spectral states of ultra-luminous X-ray sources (ULXs), most of them being extragalactic, off-nuclear, point-like X-ray sources with an X-ray luminosity in excess of ∼1039 erg s−1 (see Kaaret et al. 2017, for a review), which suggested that the majority of these objects with LX < 1041 erg s−1 could be powered by super-Eddington accretion onto stellar-mass compact objects (e.g. Stobbart et al. 2006; Gladstone et al. 2009; Sutton et al. 2013). In this still poorly understood extreme regime, the intense radiation pressure caused by the high-mass transfer rate is expected to drive powerful and conical outflows (Shakura & Sunyaev 1973; Poutanen et al. 2007; Ohsuga & Mineshige 2007; Narayan et al. 2017). The atypical ULX spectral states were thus empirically classified as hard or soft ultra-luminous (HUL and SUL regimes), which were argued to depend on whether the observer had a clean view of the inner regions of the accretion flow or instead the source was viewed through the wind (Sutton et al. 2013). The wind cone is expected to narrow with the accretion rate (King 2009; Kawashima et al. 2012) and may explain the spectral transitions frequently observed in ULXs (Sutton et al. 2013; Middleton et al. 2015a; Gúrpide et al. 2021). It has been argued that at higher inclinations or mass-accretion rates a ULX may appear as an ultra-luminous super-soft source (ULSs; e.g. Urquhart & Soria 2016). This scenario is supported by the transitions from the SUL to the super-soft ultra-luminous (SSUL) regime observed in a handful of sources such as NGC 247 ULX-1 (e.g. Feng et al. 2016; Pinto et al. 2021) and NGC 55 ULX (Pinto et al. 2017).

Multi-wavelength observations provide indirect evidence of such outflows or winds, in the form of inflated bubbles of ionised gas around a handful of ULXs (e.g. Pakull & Mirioni 2002; Abolmasov et al. 2007) or optical (Fabrika et al. 2015) and X-ray spectral lines (e.g. Pinto et al. 2020). The detection of X-ray pulsations in the light curve of six ULXs (Bachetti et al. 2013; Fürst et al. 2016; Israel et al. 2017; Carpano et al. 2018; Sathyaprakash et al. 2019; Rodríguez-Castillo et al. 2020) and possibly in another one (Quintin et al. 2021) identified the accretor as an NS and provided direct evidence of super-Eddington accretion for at least a fraction of the objects. The existing evidence, together with the sustained luminosities above 1039 erg s−1 over timescales of years (e.g. Kaaret & Feng 2009; Grisé et al. 2013) and their relative proximity, make ULXs excellent laboratories for studying super-Eddington accretion.

However, as opposed to Galactic X-ray binaries, the irregular monitoring of ULXs has precluded the study of any such evolutionary tracks, which are so important for our understanding of the accretion flow properties in the super-Eddington regime. For this reason, previous studies focussed mainly on discussing the different spectral states observed in ULXs (Sutton et al. 2013; Middleton et al. 2015a). Therefore, these studies lacked information about the timescales and duration of each spectral state, that still hampers a full understanding of the nature of these transitions.

For this reason, long-term monitoring programmes have proven particularly useful in our understanding of the mechanisms responsible for the variability in ULXs. These have revealed the presence of super-orbital periods on timescales of months (see e.g. Vasilopoulos et al. 2019; Townsend & Charles 2020 and references within), which are often variable (Kong et al. 2016; An et al. 2016; Vasilopoulos et al. 2020). The nature of these super-orbital periods remains unclear, but it has recently been proposed that a Lense-Thirring precession of a super-critical disc and outflows (Middleton et al. 2018, 2019) could explain the modulation seen in the light curves of PULXs (Dauser et al. 2017). This model has been proposed to explain the extreme flux modulation of factor > 50 due to obscuration seen in the case of NGC 300 ULX1, where a stable spin-up rate has been maintained during epochs of variable flux (Vasilopoulos et al. 2019). In addition, NGC 300 ULX1 is perhaps the only ULX system where an orbital period has been proposed to be longer than one year based on both X-ray (Vasilopoulos et al. 2018; Ray et al. 2019) and infrared properties (Heida et al. 2019; Lau et al. 2019).

In Gúrpide et al. (2021), we studied the long-term variability of a sample of 17 ULXs in order to understand the accretion flow geometry that could be responsible for the spectral variability observed in each source. In particular, we showed that certain ULXs followed an interesting evolutionary track in the hardness-luminosity diagram (HLD). Of particular interest were two archetypal ULXs, NGC 5204 X–1 and Holmberg II X–1, whose evolution could be clearly summarised in three states: ‘hard-intermediate’, ‘soft-bright’ and ‘soft-dim’ (see Fig. 6 from Gúrpide et al. 2021).

However, the limited cadence offered by XMM-Newton and Chandra precluded us from constraining the exact temporal evolution of the sources and therefore the nature of these transitions. In this work, we build on that of our previous paper by exploiting the high-cadence monitoring offered by Swift-XRT (Burrows et al. 2005) in order to constrain the temporal timescale of the transitions. We will show that these two sources describe a very similar and well-defined recurrent evolutionary cycle. Moreover, we show that the whole cycle is likely periodic, providing a clear connection between long-term periodicities and spectral changes in these ULXs.

Section 2 outlines the data reduction process. Section 3 presents the data analysis and results. In Sect. 4, we discuss our findings. Finally, in Sect. 5 we summarise our conclusions.

2. Data reduction

For this work, we used the dataset analysed in Gúrpide et al. (2021) to which we added long-term monitoring provided by archival Swift-XRT data. The details of our data reduction for XMM-Newton (Jansen et al. 2001), NuSTAR (Harrison et al. 2013), and Chandra (Weisskopf et al. 2000) can be found in Gúrpide et al. (2021). Here, we briefly summarise the main steps followed. The data used in this work is summarised in Table 1.

Observation log used for each state.

2.1. XMM-Newton

For the EPIC-pn (Strüder et al. 2001) and MOS (Turner et al. 2001) cameras we selected events with the standard filters, removing pixels flagged as bad and those close to a CCD gap. We filtered periods of high background flaring by removing times where the count rate was above a chosen threshold by visually inspecting the background high-energy light curves. Source products were extracted from a circular region with a radius of 40″ and 30″ for pn and MOS, respectively. The background region was selected from a larger, circular, source-free region on the same chip as the source (when possible). We generated response files using the tasks rmfgen (version 2.8.1) and arfgen (version 1.98.3). Finally, we regrouped our spectra to have a minimum of 20 counts per bin to allow the use of χ2 statistics and also avoid oversampling the instrumental resolution by setting a minimum channel width of 1/3 of the FWHM energy resolution.

2.2. Chandra

All Chandra data were reduced using the CIAO software version 4.11 with calibration files from CALDB 4.8.2. We used extraction regions given by the tool wavdetect to extract source events. Background regions were selected from circular nearby source-free regions that were roughly three times larger. For this work, we included four Chandra observations of NGC 5204 X–1, that were not considered by Gúrpide et al. (2021) due to their limited number of counts (< 700). These are presented in Table 2. All data were re-binned to a minimum of 20 counts per bin so as to use χ2 statistics, except for these low count observations that are re-binned to two counts per bin and analysed using the pseudo C-statistic (Cash 1979), W-stat in XSPEC1, which is suitable for the analysis of low count spectra when the background is not being modelled. The choice of two counts per bin was made in order to reduce the biases associated with the W-stat2. We note that W-stat is the default statistic used when the C-stat option is selected and a background file is read in.

Chandra observations of NGC 5204 X–1 considered in this work that were not included in Gúrpide et al. (2021).

2.3. NuSTAR

The NuSTAR data were extracted with the NuSTAR Data Analysis Software version 1.8.0 with CALDB version 1.0.2. Source and background spectra were extracted using the task nuproducts with the standard filters. Source events were selected from a circular of ∼60″ centred on the source. Background regions were selected from larger, circular, source-free regions and on the same chip as the source but as far away as possible to avoid contamination from the source itself. We re-bin NuSTAR data to 40 counts per bin, owing to the lower energy resolution compared to the EPIC cameras.

2.4. Swift

We retrieved all publicly available snapshots from the UK Swift-XRT data centre3 as of 1 August 2020. Each Swift observation is split into several snapshots, each of which we considered separately in our periodicity analysis (Sect. 3.2). In order to build products (i.e. light curves and/or spectra), we used the standard tools outlined in Evans et al. (2007, 2009), considering all detections above the 95% confidence level. We further discarded two snapshots that had a signal-to-noise below 2 from the dataset of NGC 5204 X–1 for our periodicity analysis (Sect. 3.2). We also extracted the count rate in two energy bands, a soft band (0.3−1.5 keV range) and a hard band (1.5−10 keV range), to build a hardness–intensity diagram (HID) (Sect. 3.1). We were left with 152 snapshots with a mean cadence between observations of 4.7 days for NGC 5204 X–1 and 303 snapshots with a mean cadence between observations of 1.6 days for Holmberg II X–1.

3. Data analysis and results

3.1. Long-term variability

In order to investigate the long-term variability of both sources, we inspected the Swift-XRT light curves and built HIDs for both sources (Fig. 1). Here, we considered the data binned by observations to ensure that the source was well detected in each of the energy bands.

|

Fig. 1. Left: Swift-XRT light curve in the 0.3−10 keV band for Holmberg II X–1 (top) and NGC 5204 X–1 (bottom) with its associated HID (right). Continuous monitoring intervals with data gaps of less than 12 weeks have been coloured accordingly and the legend indicates the duration in days, the number of observations, and starting date of each continuous period. Arrows in the HID indicate chronological order and errors are given every eight datapoints for clarity. Big coloured markers correspond to the Swift-XRT 0.3−10 keV count-rate estimates of the XMM-Newton and Chandra observations based on best-fit models from Gúrpide et al. (2021) (see text for details). Errors are at 1σ confidence level. We note that the x-axis has been split on the left panels. |

The Swift-XRT data for Holmberg II X–1 reveal two distinct trends, one from the 2009−2010 data in which the source switched quickly and repeatedly, within a few days (see also Grisé et al. 2010), between a bright and soft state (soft-bright state: HR ∼ 0.5, count rate in the 0.3−10 keV band ∼0.28 cts s−1) and a dim and softer state (soft-dim state: HR ∼ 0.25, count rate of ∼0.05 cts s−1). This variability is also observed intra-observation in the long (30 ks good exposure; Gúrpide et al. 2021) obs id 0561580401 (this observation is indicated as a pink triangle pointing downwards in Fig. 1).

The second trend is well sampled in the 2019 monitoring and shows that the source remained stable with HR ∼ 0.75 and a 0.3−10 keV count rate of ∼0.15−0.2 cts s−1 (hard-intermediate state). The source has been repeatedly observed in this state on several occasions prior to 2019, in 2006, 2014, and 2017. From the 2009−2010 monitoring, the duration of whole soft state transitions seems to last at least 131 days, whereas the 2019 monitoring indicates that the duration of the hard state seems to be of at least 240 days.

The identification of any pattern in the Swift-XRT data is not straightforward in the case of NGC 5204 X–1 because Swift caught the source mostly in the hard-intermediate state, albeit Gúrpide et al. (2021) showed that Holmberg II X–1 and NGC 5204 X–1 evolved in a similar manner from the analysis of archival XMM-Newton and Chandra data. To illustrate this, we adapted Fig. 6 from Gúrpide et al. (2021) in our Fig. 3 by considering the full Chandra monitoring of NGC 5204 X–1 presented by Roberts et al. (2006) (see Table 2) to highlight the short-term variability the source underwent in 2003. We fitted these new Chandra observations using the same model as in Gúrpide et al. (2021), an absorbed dual-thermal component in XSPEC (Arnaud 1996) version 12.10.1f. We fixed the galactic nH and the local nH to the same values found in Gúrpide et al. (2021). The best-fit parameters are summarised in Table 3. For our aim, we retrieved unabsorbed fluxes using cflux in the 0.3−1.5 keV and the 1.5−10 keV bands, and we show them together with the previous observations from Gúrpide et al. (2021) in Fig. 3.

Results of the fit of the Chandra observations considered in this work that were not included in Gúrpide et al. (2021).

To put the XMM-Newton and Chandra observations from Gúrpide et al. (2021) in perspective with respect to the Swift-XRT data, we estimated the count rates in the 0.3−1.5 keV, 1.5−10 keV and 0.3−10 keV bands from the best-fit model parameters from Gúrpide et al. (2021) by convolving each model with the latest redistribution matrix (swxpc0to12s6_20130101v014.rmf) and ancillary file (swxs6_20010101v001.arf) available as of 1 August 2020. In order to derive the uncertainties, we linearly interpolated the 1σ uncertainties from the observed fluxes to convert them to equivalent Swift-XRT count rates. This is represented in Fig. 1 using the same colour code as in Gúrpide et al. (2021) in the case of Holmberg II X–1 and that of Fig. 3 in the case of NGC 5204 X–1.

The pattern revealed by the Chandra monitoring is reminiscent of the transitions observed in the 2009−2010 Swift-XRT data of Holmberg II X–1 (Figs. 1 and 3). Once again, the source transits from soft-bright (HR ∼ 0.8, unabsorbed LX ∼ 9 × 1039 erg s−1) to soft-dim (HR ∼ 0.2, unabsorbed LX ∼ 2 × 1039 erg s−1) on several occasions over ∼3 months. The tightest constraints on the duration of these transitions come from the 2003-08-09/19 observations, which show that the source went back and forth from the soft-dim state to the soft-bright state in ten days. The XMM-Newton observations from Fig. 3 (coloured markers) show how the source went from the hard-intermediate state (epoch 2003-01-06) to the soft-bright state and started transiting from soft-bright to soft-dim from epoch 2003-05-01 onwards. Another transition from bright/soft to hard-intermediate was also observed by XMM-Newton in 2006. Given that the source was found in the soft-dim state in 2001 and back in that state in 2003-08-06 (Fig. 3), the full cycle seems to have a duration of less than 2 years. It is also observed that NGC 5204 X–1 was not detected in the soft-dim state by Swift-XRT.

Overall, the multi-instrument data presented reveal that the evolution of both NGC 5204 X–1 and Holmberg II X–1 are akin and can be characterised in three states: soft-bright, soft-dim, and hard-intermediate. The 2006 transitions of NGC 5204 X–1 were also discussed by Sutton et al. (2013), and thus it is easy to see that the soft-bright state corresponds to the soft ultra-luminous (SUL) regime defined by these authors, whereas the hard-intermediate states correspond to the hard ultra-luminous (HUL) regime. The soft-dim state instead shows several characteristics similar to the SSUL regime (Feng et al. 2016; Urquhart & Soria 2016; Pinto et al. 2017), namely a luminosity around 1039 erg s−1 (Fig. 3) and little emission above 2 keV (see Fig. 6 in Gúrpide et al. 2021). To illustrate this further, we measured net count rates in the same three energy bands as Urquhart & Soria (2016): 0.3−1.1 keV (S), 1.1−2.5 keV (M), and 0.3−7.0 keV (T). We computed (M − S)/T for each of the XMM-Newton and Chandra observation available for each state (Table 1). We see that the values for the soft-dim state of NGC 5204 X–1 reach (M − S)/T ≈ −0.8, the approximate threshold the authors used to classify ULX sources as super-soft. The lowest value of Holmberg II X–1 registered by XMM-Newton is −0.5, which overlaps with some super-soft sources, depending on the model considered (see their Fig. 1). We also note that Swift observed Holmberg II X–1 at even lower fluxes than those observed by XMM-Newton (Fig. 1) and that Holmberg II X–1 is generally softer than NGC 5204 X–1 (Gúrpide et al. 2021), suggesting that these differences in (M − S)/T might be mostly instrumental and that the properties of the SSUL state are broader than based on hardness alone. We discuss in Sect. 4 why Holmberg II X–1 and NGC 5204 X–1 appear slightly harder in the SSUL state than canonical ULS sources.

Additional evidence for the similarity between these states and the ULS regime comes from the rapid < 2-day variability observed in the soft-bright to soft-dim transitions in the Swift-XRT light curve of Holmberg II X–1 (see also Grisé et al. 2010). This is reminiscent of the transitions observed in the ULS in M81 (Liu 2008), which shows sudden flux drops and rises on timescales of ∼1 ks, similarly to those seen in Holmberg II X–1 (Fig. 2). The ULX-ULS transitions seen in NGC 247 ULX-1 and NGC 55 ULX are also associated with the brightest states (Feng et al. 2016; Pinto et al. 2017, 2021), which is exactly what is observed in Holmberg II X–1 and NGC 5204 X–1. Thus, Holmberg II X–1 and NGC 5204 X–1 may be the first ULXs observed to switch through all these three canonical ULX spectral states. Hereafter, we use the terms SUL, HUL, and SSUL to refer to the spectral states seen in Holmberg II X–1 and NGC 5204 X–1 for consistency with previous works.

|

Fig. 2. 0.3−10 keV background-subtracted EPIC-pn light curve of Holmberg II X–1 (obs id 0561580401) binned to 500 s and corrected using the task epiclccorr. |

|

Fig. 3. Temporal tracks on the HLD adapted from Gúrpide et al. (2021) for NGC 5204 X–1. New Chandra observations have been included to illustrate the short-term variability in 2003 (see Tables 2 and 3). Black and coloured markers indicate Chandra and XMM-Newton observations, respectively. Arrows indicate the chronological order and are only plotted for observations closer in time than four months. |

3.2. Periodicity analysis

3.2.1. Lomb–Scargle periodograms

To investigate the presence of any periodicity in the long-term evolution of NGC 5204 X–1 and Holmberg II X–1, we performed Lomb–Scargle periodograms4 (Lomb 1976; Scargle 1982), which is suitable to look for stable sinusoidal periodicities. In this implementation of the Lomb–Scargle periodogram, the uncertainties in the measurements are used to weight the differences between the sinusoidal model and the data, as with a classical least-squares estimation. We also adopted the floating-mean periodogram, in which the mean count rate is fitted in the model instead of being subtracted as for the classical periodogram, which has been shown to give higher accuracy, especially when the data does not have full phase coverage (VanderPlas 2018). For this analysis, we used the data from the Swift-XRT as it has the highest cadence and longest monitoring.

In the case of unevenly sampled data, there is no well-defined Nyquist frequency and thus the maximum frequency explored in the periodogram has to be set according to some physical and/or observing constraints. In this case, we restricted the maximum frequency explored to 5 −1days, which is slightly above the typical cadence at which Swift visited each source. The minimum frequency explored is set to 1/Tsegment where Tsegment is the duration of the continuous light-curve segment considered in each case. We oversampled the periodogram by a factor of five (i.e. Δf = 1/nTsegment where n = 5).

3.2.2. False-alarm probability: Bootstrap method

A common challenge in the Lomb–Scargle periodogram is to estimate the significance of a peak in the power spectrum. In the presence of white noise, Scargle (1982) showed that the false-alarm probability of a single peak with power P is F(P) = 1 − e−P. However, because we are essentially trying to detect a peak over a certain frequency range, one should account for the fact that several frequencies are being explored. This is challenging because the frequencies in the Lomb–Scargle periodogram are not independent, and thus one cannot compute the false-alarm probability simply by assuming that several independent frequencies (i.e. trials) have been looked for. Some empirical estimates of the number of independent frequencies exist (e.g. Horne & Baliunas 1986), but the most robust method is to rely on Monte Carlo simulations to calibrate the reference distribution as it makes few assumptions on the number of independent frequencies and considers the observing cadence of the real data, so the effects of the observing window are taken into account.

We thus estimated 2σ and 3σ false alarm probabilities in the absence of a signal by using the bootstrap method outlined in VanderPlas (2018). This method generates N light curves by drawing random samples from the original measurements to generate light curves with the same time coordinates as for the original data. For each randomised light curve, the same Lomb–Scargle periodogram is performed as for the real data. From the maxima of these fake periodograms, the reference distribution is built. Another advantage of this method is that the null-hypothesis model is not based on pure white noise, since the reference distribution is built on randomised data, although there are other limitations to consider (which we discuss in Sect. 3.2.3). We performed 3500 simulations to ensure that at least ten peaks are found above the 3σ level and thus that the reference distribution was well sampled (VanderPlas 2018).

For Holmberg II X–1, in order to avoid aliasing effects caused by the large data gaps, we analysed the data separately in two segments of continuous monitoring. The first segment included the data from 2009 to 2010 and the second one comprised the 2019 data. The resulting periodograms are shown in Figs. 4 and 5. In the inset of the figures we also show the structure of the observing window, which is computed by performing the Lomb–Scargle periodogram on a light curve of constant flux and the same time coordinates as for the real data.

|

Fig. 4. Top left: Lomb–Scargle periodogram for the entire 2009−2010 Swift-XRT dataset of Holmberg II X–1 (black solid line). The 2σ and 3σ levels (dashed and dotted lines, respectively) mark the false alarm probability computed from bootstrapped samples (see text for details). The inset shows the structure of the observing window. Top right: Swift-XRT light curve corresponding to the 2009−2010 segment. The solid purple line indicates the best-fit period from the periodogram of the whole light-curve segment. The solid light blue line indicates the best-fit period from the periodogram considering only the light curve segment to the left of the blue dashed line, while the yellow solid line indicates the best-fit period from the light-curve segment to the right of the blue dashed line. Bottom: Lomb–Scargle periodograms of two sub-segments of the 2009−2010 data separated by the blue dashed line in the top right panel (left and right panels correspond to the data prior to and after ∼day 1480). |

The periodogram of the 2009−2010 segment reveals two strong peaks at around 21 and 28 days both with a significance above the 3σ level. However, the observing window has a strong power at ∼25 days (Fig. 4), which may be introducing some aliasing. We also note that Grisé et al. (2010) analysed the same dataset and found no evidence of any periodicity. However, the discrepancy between these results might be simply due to the differences in the periodogram implementation used by the authors (the prescription by Horne & Baliunas 1986), the sampling grid, the way the false alarm probabilities were computed, and the fact that their implementation did not take into account the uncertainties in the measurements.

The best solution given by the 28-day peak is shown in Fig. 4 (see the light purple solid line in the top right panel). The variability is clearly more complex than described by the simple sinusoidal profile. It is also observed that the source variability changed after 2 February 2010 (see the blue dashed vertical line in the top right panel of Fig. 4). Since there is now compelling evidence of variable periodicities in ULXs (Kong et al. 2016; An et al. 2016; Brightman et al. 2019; Vasilopoulos et al. 2020) with an as yet unclear origin, we repeated our analysis by considering the data before and after 2 February 2010 separately. The results are presented in the top right and bottom panels of Fig. 4. The peak from the first segment is consistent with the one at 28 days previously found, albeit now is found slightly below the 3σ level. For the second segment after the blue dashed line, we found no evidence of any periodicity above the 2σ level. We still show the best solution from the highest peak found in the periodogram (yellow solid line in the top right panel of Fig. 4) to illustrate that if the oscillation is still present, its amplitude must have significantly decreased. Finally, the 2019 data showed no evidence of any periodicity, which may indicate that the oscillation has decreased significantly or disappeared entirely (see Fig. 5).

For NGC 5204 X–1, we analysed only the continuous and densely sampled part of the light curve from ∼day 300 until ∼day 900 after the start of the monitoring (green and purple segments in Fig. 1). The Lomb–Scargle periodogram reveals a strong peak at around 221 days (Fig. 6), which is not coincident with any structure from the observing window. The peaks at 444 days and 103 days above the 3σ are almost exactly or very close to 2 × 221 days and 221/2 days, respectively, suggesting that they could be harmonics of the period at 221 days. The peak at 444 days is also highly uncertain as it is only supported by 1.5 cycles, and stronger noise is expected towards longer periodicities given the sparsity of our data and the structure of the observing window. We also observe some variability on top of the sinusoidal variation at around 700−800 days after the beginning of the monitoring.

|

Fig. 6. Left: Lomb–Scargle periodogram of the 2014−2015 Swift-XRT light curve of NGC 5204 X–1 in solid black. The 2σ and 3σ mark the false alarm probability levels computed from bootstrapped samples (see text for details). The inset plot shows the structure of the observing window. Right: Swift-XRT light curve with the best-fit period from the periodogram (orange solid line). |

3.2.3. False-alarm probability: REDFIT

We note, however, that in the presence of aperiodic variability, the measurements could have some degree of correlation (i.e. in the presence of a flare) and by design, any correlation will be lost in the bootstrapped samples. In fact, red-noise, commonly observed in accreting sources, can often appear periodic (e.g. Scargle 1981; Vaughan et al. 2016), and tests against the null-hypothesis of white noise often underestimate the false-alarm probability of the peaks in the periodogram (e.g. Liu 2008).

We therefore performed a second test to derive the significance of the peaks in the periodogram under the null-hypothesis of red noise. To do so, we based ourselves on the publicly available R code REDFIT developed by Schulz & Mudelsee (2002)5, in which red noise is modelled as a first-order autoregressive process (termed AR(1) for short), a model commonly used in astrophysics to model stochastic time series (see e.g. Scargle 1981 and also An et al. 2016 for a similar approach). In AR(1) processes, the time series (xi) at a given time (ti) depend on the previous sample as xi = ρixi − 1 + ϵi, where ρ is the autocorrelation coefficient and ϵ is the random component with zero mean and a given variance σ2. The case in which ρ = 1 simply describes a random walk. For unevenly sampled data, the AR(1) can be modelled with a variable autocorrelation coefficient that depends on the sampling time difference ρ = e−(ti − ti − 1)/τ (Robinson 1977), where τ is the characteristic time of the AR(1) process, a measure of its memory and σ2 is set equal to 1 − e−2(ti − ti − 1)/τ to ensure that the AR(1) process has a variance equal to unity and is stationary. τ can be calculated directly from the time series using the least-squares algorithm of Mudelsee (2002). From the AR(1) model, an ensemble of Monte Carlo simulations of time series with the same sampling as for the original light curve can be created to test whether the presence of a peak in the periodogram is consistent with an AR(1) process. However, the Lomb–Scargle implementation proposed by Schulz & Stattegger (1997) does not take into account the uncertainties in the data, and the mean of the measurements is not fitted as for the floating-mean periodogram. Additionally, REDFIT might underestimate the significance of the peaks in the periodogram as it computes the false alarm probabilities based on the entire distribution of the simulated periodograms rather than on the largest peak in each synthetic periodogram.

Because of the caveats outlined above, we replicated the same approach but instead simulated the ensemble of AR(1)-generated light curves by setting the variance of the noise  , where σd is the variance of the data, so that the simulated data has a variance equal to that of the real measurements. We then added an offset to the simulated data equal to the mean of the real measurements, so the simulated data also has approximately the same mean. We then computed uncertainties on xi assuming Poissonian statistics. In cases where xi happens to be negative, we simply set the uncertainty equal to that of the observed data at i. We note that there is no issue in introducing negative rates in the Lomb–Scargle calculation, although the simulations should ideally be flux limited to match the real measurements more closely.

, where σd is the variance of the data, so that the simulated data has a variance equal to that of the real measurements. We then added an offset to the simulated data equal to the mean of the real measurements, so the simulated data also has approximately the same mean. We then computed uncertainties on xi assuming Poissonian statistics. In cases where xi happens to be negative, we simply set the uncertainty equal to that of the observed data at i. We note that there is no issue in introducing negative rates in the Lomb–Scargle calculation, although the simulations should ideally be flux limited to match the real measurements more closely.

We then conducted the same Lomb–Scargle periodograms on these light curves as for the real data, taking into account the uncertainties. Following Schulz & Mudelsee (2002), we scaled the synthetic periodograms to match the area under the power spectrum of the real data and computed a bias-corrected version of the periodograms. We finally derived the false-alarm probability levels from each of the largest peaks in the synthetic periodograms. Results are shown in Fig. 7 for 10 000 Monte Carlo simulations.

|

Fig. 7. False-alarm probabilities for the Lomb–Scargle periodogram based on an adaptation of the REFIT code (see text for details) for NGC 5204 X–1 (left) for the 2014−2015 monitoring and for Holmberg II X–1 (right) for the 2009−2010 monitoring under the null-hypothesis of red noise. The coloured 95.5% and 99.7% mark the distribution of the 10 000 synthetic periodograms, whereas the black dashed line marks 2σ and 3σ false-alarm probabilities, which have been determined from the maximum of the peaks of the synthetic periodograms. |

As expected, the false alarm probabilities under the null-hypothesis of red noise are more stringent than those from the bootstrap method. For Holmberg II X–1, the peak is well below the 3σ false-alarm probability. If we consider the less stringent false-alarm probability computed from the entire distribution of simulations (green line), the peak is only slightly below this limit. It is possible that the variability exhibited by the source (Fig. 4, right panel) is complicating the detection of the quasi-periodicity if the latter is not strictly coherent. Thus, more monitoring might be needed to clarify whether the variability is indeed quasi-periodic. Instead, for NGC 5204 X–1 the red-noise AR(1) process cannot account for the variability observed, suggesting that the periodicity in the periodogram might be real.

3.2.4. Uncertainties on the period

In order to derive meaningful uncertainties on the periodicity of NGC 5204 X–1, we followed Brightman et al. (2019) and used a fitting procedure based on Gaussian process modelling proposed by Foreman-Mackey et al. (2017). Gaussian processes offer several advantages over the classical Lomb–Scargle periodogram, namely the possibility to test more refined models than the implicitly assumed stable sinusoid in the Lomb–Scargle periodogram, and the possibility to retrieve meaningful errors on the best period estimate, which are not well defined in the case of the periodogram VanderPlas (2018). We used the python implementation celerite proposed by Foreman-Mackey et al. (2017) and considered three different models consisting of one or two components for our data.

The first model (model a) has a single term to capture the oscillatory behaviour by means of a damped simple harmonic oscillator (SHO), whose power spectral density is given by

where S0 is the amplitude of the oscillation, ω0 is the frequency of the undamped oscillator, and Q is the quality factor, which indicates how peaked the periodicity is in the PSD and gives a measure of the stability of the periodicity. For the second and third models, we added a noise component on top of the SHO to consider the variations not captured by the Lomb–Scargle solution (see e.g. Fig. 6 around 700−800 days after the beginning of the monitoring). In one of the models, this noise was modelled with a white noise or jitter term (model b) with amplitude σ. For the other model (model c), we considered a red-noise component that can be modelled in celerite with the same kernel as for the damped harmonic oscillator, but fixing QN = 1/ (Foreman-Mackey et al. 2017), and leaving the other parameters of the oscillator (SN, ωN) free to vary during fit. To summarise, we thus tested three different models: (a) a single SHO term, (b) the same SHO term but with a white noise term, and, finally, (c) the SHO term with the red-noise component.

(Foreman-Mackey et al. 2017), and leaving the other parameters of the oscillator (SN, ωN) free to vary during fit. To summarise, we thus tested three different models: (a) a single SHO term, (b) the same SHO term but with a white noise term, and, finally, (c) the SHO term with the red-noise component.

In order to select the most suitable model for our datasets, we fitted each of the three models to the light curve using the L-BFGS-B minimisation method from scipy and retrieved the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) (Schwarz 1978) as given in Eq. (54) of Foreman-Mackey et al. (2017), meaning lower BIC values indicating preferred models. We set the following uniform priors on the parameters: 10 < P < 700 days, 0.1 < S0 < 10 000, and 20 < Q < 2000. That is, all parameters are essentially unconstrained except for the lower bound of Q, which we limited, as low values of Q lose the oscillatory behaviour that we want to describe (Foreman-Mackey et al. 2017). For the red-noise component, SN and ωN are arbitrarily started at log ωN = −0.1 and log SN = −5 with the following uniform priors (again essentially unconstrained): −10 < log ωN < 15 and −10 < log S0 < 15. The amplitude of the white noise term σ is set initially to the mean value of the count-rate errors and is allowed to vary between −10 < log σ < 15. We performed several runs varying the initial parameters to ensure that the minimisation routine finds the global minimum for each model. The best-fit parameters and the BIC calculations are presented in Table 4.

Best-fit parameters from the minimisation routine for the three different models tested and the corresponding Bayesian information criterion (BIC) for each of them to model the 2014−2015 light curve of NGC 5204 X–1.

Based on the BIC values, the model with the addition of white noise (model b) seems to be the preferred model. The addition of a more complex red-noise component (model c) seems not to be justified by the quality of data since a similar solution is found to that of model b (Table 4), with the addition of an extra parameter. Therefore, the simpler white noise component seems to be the preferred model, and we thus considered only this model for the subsequent analysis. The best-fit model is shown in Fig. 8.

|

Fig. 8. Left: best-fit solution of the celerite modelling (orange solid line) with the 1σ shaded contours for the light curve of NGC 5204 X–1. The model shows the SHO with additional white noise (model b), for which we only show the oscillatory component. Right: posterior probability distributions of the parameters of the celerite model. The histograms along the diagonal show the marginalised posterior distribution for each parameter with dashed lines indicating the median and the 1σ errors. The two-dimensional histograms show the marginalised regions for each pair of parameters with the contours showing the 1 and 2σ confidence intervals. |

In order to estimate errors on the best fit parameters of the model with the added white noise, we initialised 32 walkers (or chains) to sample the posterior probability distribution by drawing 20 000 MCMC samples using the emcee library in python. Each walker is initialised by randomly drawing a sample from the uniform priors defined above to ensure that parameter space is adequately sampled by the chains. In order to estimate an adequate burn-in period, we visually inspected the convergence of the chains and discarded the first 10 000 samples of each of them. From the remaining samples, we selected one every 20 samples to derive the posterior probability density that is shown in Fig. 8. The periodicity found above in the light curve of NGC 5204 X–1 is of 197 days (1σ error), which is consistent with the 221-day peak found in the Lomb–Scargle periodogram (Sect. 3.2.3) at the 1σ level.

days (1σ error), which is consistent with the 221-day peak found in the Lomb–Scargle periodogram (Sect. 3.2.3) at the 1σ level.

3.3. Spectral analysis

Here, we attempt to spectrally characterise each of the states found in Sect. 3.1 (HUL, SUL, and SSUL regimes) with a physically motivated model. To do so, we made use of the XMM-Newton, Chandra, and NuSTAR data used in Gúrpide et al. (2021), and the additional Chandra and Swift-XRT data of this work. We considered all the available datasets for each state, regardless of their date, and fitted them assuming the same model. This selection is driven by the results from Sect. 3.1 and the analysis presented in Gúrpide et al. (2021). We also extracted Swift-XRT spectra for each source state by stacking individual observations using the online tools (Evans et al. 2009). The count rates and hardness used to classify the observations can be found in Table 5. For NGC 5204 X–1, we found the data quality of Swift-XRT spectra to be too low for a meaningful analysis. For Holmberg II X–1, we only found good agreement between the Swift-XRT data and the other mission datasets for the SUL regime, and thus this was the only Swift-XRT spectrum that we finally used. In the other cases, we found the Swift-XRT data to be significantly dimmer below 1 keV compared to the other datasets (residuals of ≳3σ) and the floating cross-calibration constant is above 10% with respect to the XMM-Newton data, even when taking into uncertainties. This disagreement is consistent with the scatter seen in the Swift-XRT observations with respect to the XMM-Newton observations of the SSUL and HUL regimes (Fig. 1).

Swift-XRT count rates and hardness ratios used to extract stacked spectra.

We also inspected the XMM-Newton optical monitor and the Swift-UVOT images looking for observations that could help to constrain the broadband emission. However, given the limited spatial resolution of the instruments (PSF ∼ 1 arcsec), both ULXs are completely blended with nearby sources in the field of view preventing a clean determination of the direct contribution from the ULX. We therefore searched for Hubble Space Telescope optical/UV data using the MAST portal6 and selected observations when the source state was known. We restricted the search to the wide or medium filters as we were interested in the continuum emission. Unfortunately, we only found quasi-simultaneous HST data for the hard-intermediate state of Holmberg II X–1 in the F275W, F336W, F438W, and F550M filters. We used a 0.255″ radius circular aperture for the source and an annulus of 0.37″ and 0.58″ inner and outer radius for the background, to consider some of the nebular emission in the background subtraction. We applied the appropriate aperture correction for each filter7 and converted the telescope counts to fluxes using the calibration PHOTFLAM keywords found in the file headers8. We obtained background-corrected fluxes in units of erg cm2 s−1 Å−1 of (6 ± 2) × 10−17, (3.6 ± 0.8) × 10−17, (1.6 ± 0.4) × 10−17, and (7 ± 2) × 10−18 for the F275W, F336W, F438W, and F550M filters, respectively. The different datasets considered together to characterise each state can be found in Table 1.

Previous broadband spectral analysis by Tao et al. (2012) of Holmberg II X-1 indicated that the emission could be consistent with an irradiated standard accretion disc and that a stellar origin was unlikely. Here, we chose to model our data with the physically motivated model sirf (Abolmasov et al. 2009, available in XSPEC), which provides a self-consistent analytical solution to the super-critical funnel geometry based on the theoretical works of Shakura & Sunyaev (1973) and Poutanen et al. (2007) to see if the broadband emission could instead be explained as arising from a self-irradiated super-critical disc.

This model considers black-body emission from the outer wind photosphere, the walls of the super-critical funnel, and the photosphere at the bottom of the funnel, taking into account self-irradiation effects. The model has nine variable parameters: namely, the temperature and the distance from the source of the funnel bottom photosphere (Tin and Rin), the outer wind photospheric radius (Rout), the half-opening angle of the funnel (θf), the velocity-law exponent for the wind (α) that is, vwind ∝ rα, the adiabatic index (γ), the mass-ejection rate (ṁejec), and the normalisation of the model. As a caveat, we note that the model does not take into account Comptonisation, which is likely to be an important source of opacity in the super-Eddington regime (e.g. Kawashima et al. 2012).

We modelled interstellar X-ray absorption with two tbabs components, one frozen at the Galactic value along the line of sight (2.72 × 1020 cm−2 and 5.7 × 1020 cm−2 for NGC 5204 X–1 and Holmberg II X–1, respectively; HI4PI Collaboration 2016) and another one free to vary. For the dataset containing HST data, we considered interstellar extinction by adding the redden model in XSPEC with E(V − B) fixed to 0.074, based on the measured Hα/Hβ ratio from the nebular emission of Vinokurov et al. (2013) and using the extinction curve from Cardelli et al. (1989) of RV = 3.1.

The nine parameters of the sirf model could not all be constrained if left free to vary, even for the hard-intermediate state of Holmberg II X–1, where we had the best data quality. Therefore, following Abolmasov et al. (2009), in all fits we fixed the velocity law exponent of the wind (α) to −0.5, the adiabatic index (γ) to 4/3, and Rout to 100 Rsph, as the latter parameter is insensitive to the spectra unless its value is below 1, according to the authors. However, we found that for the soft and super-soft states, due to the lack of optical coverage and the poor data quality, we could not discriminate between different solutions, with the fit often being insensitive to several parameters and resulting in large parameter uncertainties. Another complication arose due to the fact that the model favours solutions in which i ∼ θf when θf was not well constrained. This occurs due to the fact that a sharp transition is created in the χ2 space when the model changes from a solution where our line of sight is within the wind cone to a solution with the wind cone out of the line of sight, creating an artificial minimum in the χ2 space at i ∼ θf. We therefore decided to restrict the spectral analysis to the hard-intermediate states, which are the only states for which we have good quality broadband data. Obtaining HST observations of both ULX in the different spectral states should help to allow us to constrain the broadband emission.

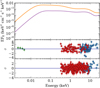

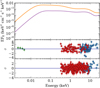

The sirf model offered a good fit ( = 1.00 for 960 degrees of freedom) to the broadband emission (see Fig. 9 and Table 6) of Holmberg II X–1 in the HUL state. Thus, while emission from the donor star or an irradiated disc could be consistent with the UV/optical emission (e.g. Tao et al. 2012), self-irradiation by a super-critical disc seems another plausible scenario based on the broadband emission. We found an upper limit on i of 9.1°. This is slightly below the lower limit of 10° suggested by Cseh et al. (2014), assuming that the radio jet detection is not strongly Doppler boosted, although we note that if the source precesses, the viewing angle could be variable. Therefore, a viewing angle looking down the funnel (θf ∼40°) seems to be supported. For NGC 5204 X–1, we similarly obtained an upper limit on i of ∼12°. Interestingly, the set of parameters obtained are very similar to those obtained for Holmberg II X–1, except for a factor of ∼7 lower ṁejec and a factor of ∼5 higher Rin (see Table 6). Therefore, the spectral differences between NGC 5204 X–1 and Holmberg II X–1 could be accounted for by a lower ṁejec and a thicker bottom of the funnel in the case of NGC 5204 X–1 with an unobscured view of the bottom of the funnel in both cases.

= 1.00 for 960 degrees of freedom) to the broadband emission (see Fig. 9 and Table 6) of Holmberg II X–1 in the HUL state. Thus, while emission from the donor star or an irradiated disc could be consistent with the UV/optical emission (e.g. Tao et al. 2012), self-irradiation by a super-critical disc seems another plausible scenario based on the broadband emission. We found an upper limit on i of 9.1°. This is slightly below the lower limit of 10° suggested by Cseh et al. (2014), assuming that the radio jet detection is not strongly Doppler boosted, although we note that if the source precesses, the viewing angle could be variable. Therefore, a viewing angle looking down the funnel (θf ∼40°) seems to be supported. For NGC 5204 X–1, we similarly obtained an upper limit on i of ∼12°. Interestingly, the set of parameters obtained are very similar to those obtained for Holmberg II X–1, except for a factor of ∼7 lower ṁejec and a factor of ∼5 higher Rin (see Table 6). Therefore, the spectral differences between NGC 5204 X–1 and Holmberg II X–1 could be accounted for by a lower ṁejec and a thicker bottom of the funnel in the case of NGC 5204 X–1 with an unobscured view of the bottom of the funnel in both cases.

|

Fig. 9. Top: broadband best-fit (solid lines) to the HUL states of Holmberg II X–1 (orange) and NGC 5204 X–1 (purple line) with the self-irradiated super-critical funnel model (sirf in XSPEC) for i ∼ 10° (see Table 6). The models in the upper panel have been corrected for X-ray and optical absorption. Lower panels: best-fit residuals for Holmberg II X–1 (middle panel) and NGC 5204 X–1 (bottom panel) without any correction for X-ray absorption. Green, red, and blue circles show the HST, XMM-Newton EPIC-pn, and FPMA NuSTAR data, respectively (see Table 6). |

Best-fit results for the HUL states seen in NGC 5204 X–1 and Holmberg II X–1 using the sirf model.

4. Discussion

The multi-instrument data analysed in this work has allowed us to firmly establish, for the first time, the presence of a recurrent evolutionary cycle in ULXs. The similarities that exist in the temporal (Figs. 1 and 3) and spectral (Fig. 9 and Table 6; see also Fig. 6 in Gúrpide et al. 2021) properties of Holmberg II X–1 and NGC 5204 X–1 allow us to describe the evolution of the cycle as follows: starting from the HUL state, the sources transit to the SUL state (Fig. 3). There, the sources will transit back and forth from the SUL regime to the SSUL regime (Figs. 1 and 3), and finally the sources will return to the HUL state from the SUL state (Fig. 3). These findings offer a unique opportunity to constrain the timescale and nature of the transitions frequently observed in these sources (e.g. Roberts et al. 2006; Grisé et al. 2010) and could potentially be extended to similar transitions seen in other ULXs as well (e.g. Middleton et al. 2015b; Gúrpide et al. 2021; Mondal et al. 2021).

Spectral transitions in ULXs have been frequently discussed invoking geometrical effects induced by the wind/funnel structure (e.g. Sutton et al. 2013; Middleton et al. 2015a; Pinto et al. 2021) expected to form as the mass-transfer rate approaches the Eddington limit and radiation pressure starts to drive a conical outflow (Shakura & Sunyaev 1973; Poutanen et al. 2007). Building a coherent picture of the long-term spectral evolution of these two ULXs was attempted in Gúrpide et al. (2021), where it was suggested that the transition from the hard to the soft ULX regime was due to an increase of the mass-transfer rate and corresponding decrease of the opening angle of the funnel, based on the HUL-SUL softening from a rather sparse monitoring provided by XMM-Newton and Chandra. The authors also suggested that a line of sight grazing the wind walls in the SUL state could explain the rapid transitions observed to the SSUL state as we switch between peering down the optically thin funnel and observing the wind photosphere as the source precessed (e.g. Abolmasov et al. 2009). We note that a viewing angle grazing the wind walls is also supported by the lack of short-term variability in the SUL state of Holmberg II X–1 and NGC 5204 X–1 (e.g. Heil et al. 2009; Sutton et al. 2013), which is at odds with the high short-term variability seen in softer of the soft ULXs (e.g. Middleton et al. 2011) argued to be viewed through the wind. However, the lack of periodic variability (Fig. 7) in the SUL–SSUL transitions found here suggests that precession of the accretion flow might not be responsible for the spectral changes. Instead, a scenario in which the short-term variability may be ascribed to the presence of wind clumps crossing our line of sight (Takeuchi et al. 2013; Middleton et al. 2015a) as a result of the narrower funnel is supported by the aperiodic transitions.

Similar transitions from SUL to SSUL are seen in the ULS NGC 247 ULX-1 (Urquhart & Soria 2016; Feng et al. 2016) and NGC 55 ULX (Pinto et al. 2017), which are also observed during the bright states (Pinto et al. 2021), suggesting a tight link between standard ULXs and ULSs. However, as opposed to NGC 247 ULX-1, Holmberg II X–1 and NGC 5204 X–1 are the first sources observed to switch through all these three canonical ULX states, possibly due to the lower viewing angle compared to ULSs. Moreover, dips frequently seen in ULSs (e.g. Stobbart et al. 2006; Urquhart & Soria 2016; Alston et al. 2021) are not observed in the light curves of Holmberg II X–1 and NGC 5204 X–1, supporting this interpretation. It is thus likely that the dipping activity in ULSs is associated with direct obscuration of the inflated accretion disc as a result of the increased mass-accretion rate (Guo et al. 2019). Hence, the increase in mass-accretion rate confers Holmberg II X–1 and NGC 5204 X–1 with a somewhat harder ULS aspect, because the SSUL aspect of these standard ULXs is not due to a high inclination angle, but rather due to the extreme narrowing of the funnel. This might imply that ULSs are characterised by both a high inclination angle and a high mass-accretion rate.

The amplitude of the jittering decays towards the end of the 2009−2010 monitoring of Holmberg II X–1 (Fig. 4). This might imply that the mass-transfer rate has increased and narrowed the funnel further; so, towards the end of the 2009−2010 monitoring our line of sight no longer sees the inner regions of the accretion flow and instead mostly sees the wind photosphere, reducing the observed variability. Such dimming and reduced variability caused by an increase of the mass-accretion rate is in good agreement with the predictions made by Middleton et al. (2015a) for sources at moderate inclinations. This is illustrated in Fig. 10, panels b and c.

|

Fig. 10. Cartoon illustrating the different spectral states observed in Holmberg II X–1 and NGC 5204 X–1 as a function of the mass-transfer rate and wind clumps crossing the line of sight. The compact object (NS or a BH) is represented by a white sphere. From top to bottom, the mass transfer increases as indicated by the black arrow on the right. In panel a, the funnel is wide open due to the low accretion rate, and the observer sees the inner regions of the accretion flow and little variability is observed (HUL regime; 2019 Swift monitoring of Holmberg II X–1), because the wind is unlikely to enter the line of sight. The left graph shows the corresponding spectral state (adapted from Gúrpide et al. 2021). In panel b, the mass-transfer rate increases and narrows the opening angle of the funnel (SUL regime; SSUL regime), so wind clumps might now start to enter the line of sight and produce the spectral changes from soft to the SSUL regime observed (right and left panels and as seen in the 2009 Swift monitoring of Holmberg II X–1). Finally, in panel c, the mass-transfer rate increases further and the wind cone is now in the line of sight. The observer mostly sees the wind and the colder outer parts of the inflated disc, so the effect of absorption by wind clumps is dampened (end of the 2009−2010 Swift monitoring of Holmberg II X–1). |

The spectral analysis might support a low viewing angle for Holmberg II X–1 and NGC 5204 X–1, at least for the HUL state (Sect. 3.3), and a moderate opening angle of the funnel (θf ∼ 40°). The lack of clear jittering behaviour in the 2019 data (see Fig. 1) may be explained by the larger opening angle of the funnel as a result of the lower mass-transfer rate, implying that the wind is unlikely to enter the line of sight. This is consistent with the reduced short-term variability seen in hard ULXs (e.g. Middleton et al. 2015a; Sutton et al. 2013), frequently argued to be viewed face-on, and is consistent with the suggestion that the increase of mass-transfer rate and narrowing of the opening angle of the funnel causes the HUL–SUL spectral change (Fig. 3). This interpretation naturally accounts for the lack of direct transitions from the SSUL regime to the HUL regime (Figs. 1 and 3). A cartoon illustrating the source variability and its relation to the different spectral states is depicted in Fig. 10.

The ∼200-day periodicity found in the light curve of NGC 5204 X–1 is possibly associated with the timescale of the whole cycle (Fig. 8); albeit, further investigation is needed. While the nature of this periodicity remains unclear, should our interpretation of the evolutionary cycle be correct, we would expect some mechanism of periodic mass-transfer increase to be responsible for it and cause the source to switch from the HUL regime to the SUL state. This could be the case in an eccentric orbit in which the mass-transfer rate is expected to be maximal as the companion passes through the periapsis. This scenario would likely require a super-giant star, as for large eccentricities e > 0.5 we find that the star would need to have a radius in excess of ∼200 R⊙ to fill its Roche-Lobe overflow for compact objects of masses as low as 1.4 M⊙. This large radius is at odds with the suggested radius of 30 R⊙ for the companion based on the UV spectrum of the counterpart (Liu et al. 2004). Additionally, orbital solutions in ULXs (only available thanks to a timing solution in ULXs showing pulsations) require modest eccentric orbits (e ≲ 0.1 Bachetti et al. 2014; Fürst et al. 2018; Rodríguez-Castillo et al. 2020) and generally shorter orbital periods (P ≲ 60 days) are found, although the orbital period of NGC 300 ULX1 is expected to be of ∼1 year based on the red super-giant companion (Heida et al. 2019).

Another mechanism that could induce periodic increases in the mass-transfer rate is the Kozai mechanism (Kozai 1962), in which the presence of a third body causes modulation of the eccentricity of the inner binary. The changes in eccentricity will affect the distance between the inner L1 Lagrangian point and the centre of mass of the companion, therefore modulating the mass-transfer rate. This mechanism has been proposed to explain the super-orbital X-ray modulation of ∼176 days associated with mass-transfer rate variations in the triple system 4U1820−303 (see Zdziarski et al. 2007 and references therein). It has also been suggested that this mechanism could explain the ∼ 60-day quasi-periodicity responsible for the strong bi-modal flux modulation of the PULX M82 X–2 (Brightman et al. 2019; Bachetti et al. 2020), which has been argued to be due to the NS switching back and forth from the accretor phase to the propeller regime (Tsygankov et al. 2016).

It is also worth noting that a linear relationship has been found between super-orbital and orbital periods in Be/X-ray binaries, SGXBs, and ULXs (see Corbet & Krimm 2013; Townsend & Charles 2020, and references therein). Assuming the 200-day periodicity is super-orbital in nature, we would expect an orbital period in NGC 5204 X–1 of the order of ∼10 days. This is in agreement with the estimate made by Liu et al. (2004), based on the UV spectrum of the counterpart and on the assumption that the companion fills its Roche Lobe. Indeed, the relationship between the orbital and super-orbital periods would imply that NGC 5204 X–1 is a system with a super-giant filling its Roche Lobe (Townsend & Charles 2020). We note that the linear relationship between the period and super-orbital period in super-giant Roche-Lobe filling systems is yet unclear, although the presence of a third body could account for the super-orbital periodicity (Corbet & Krimm 2013), as stated also above.

Finally, we note that further monitoring of the soft spectral transitions would be of interest to robustly determine whether the spectral changes are associated with a quasi-periodicity. It has recently been proposed that a possible mechanism to account for the observed superorbital periods in ULXs could be the Lense-Thirring effect (Middleton et al. 2018). If so, precession of the accretion flow induced by the Lense-Thirring effect may explain the spectral changes from SUL to SSUL as the wind cone comes into and out of the line of sight throughout the precession cycle, strongly modulating the flux (Abolmasov et al. 2009; Dauser et al. 2017). The decay of the amplitude of the putative modulation towards the end of 2009–2010 could be similarly accounted for by an increase in the mass-accretion rate associated with a reduction of the opening angle of the funnel, meaning that throughout the whole cycle we only see the wind. Conversely, the lack of modulation during the HUL state of 2019 (Fig. 5) could be due to the opposite effect, that is, a larger opening angle of the funnel resulting from a decrease of the mass-transfer rate. In this case, our line of sight observes the optically thin funnel (e.g. Narayan et al. 2017) throughout the whole precessing cycle, again effectively diminishing the amplitude of the oscillation (Abolmasov et al. 2009).

5. Conclusions

We show the striking similarities of Holmberg II X–1 and NGC 5204 X–1 in their long-term evolution as they transit through the canonical hard, soft, and super-soft ULX spectral regimes. This is the first time that such recurrent evolutionary cycle is observed in ULXs and that all three states are observed in a single ULX, strengthening the hypothesis that ULSs are standard ULXs viewed at high inclinations. We argue that the sources transit from hard to soft ULX as the mass-transfer rate increases and the funnel closes. There, the source will exhibit jittering, as wind clumps start to cross the line of sight due to the now narrower funnel, explaining the spectral transitions from soft to super-soft ULX. As the mass-accretion rate increases further and the funnel closes, our line of sight mostly sees the wind photosphere, with the subsequent reduction of short-term variability. The absence of SSUL–HUL state transitions are naturally explained by this scenario.

This interpretation is supported by the Swift-XRT light curve of Holmberg II X–1, which shows a lack of strong variability in the hard ULX state and a strong rapid variability responsible for the spectral changes between soft and super-soft states. The light curve of NGC 5204 X–1 shows instead a periodicity on a long timescale of ∼200 days, which is likely associated with the duration of the full hard–soft–super-soft cycle; albeit, further monitoring is needed to robustly confirm this association. We argue that the transitions from hard to soft ULX are likely associated with some periodic increase of the mass-transfer rate, yet the nature of this modulation remains unclear. Similar periodicity may be present in the long-term evolution of Holmberg II X–1 based on its similarities with NGC 5204 X–1. We therefore encourage Swift-XRT monitoring of Holmberg II X–1 over longer timescales to detect it.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewer for comments and suggestions that improved this manuscript. The authors are grateful to H. Carfantan for his help with the timing analysis. GV acknowledges support by NASA Grant numbers 80NSSC20K1107, 80NSSC20K0803 and 80NSSC21K0213. NAW acknowledges support by the CNES. Software used: HEASoft v6.26.1, Python v3.8, Veusz 3.3.1 (J. Sanders).

References

- Abolmasov, P. K., Swartz, D. A., Fabrika, S., et al. 2007, ApJ, 668, 124 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Abolmasov, P., Karpov, S., & Kotani, T. 2009, PASJ, 61, 213 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Alston, W. N., Pinto, C., Barret, D., et al. 2021, MNRAS, 505, 3722 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- An, T., Lu, X.-L., & Wang, J.-Y. 2016, A&A, 585, A89 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Arnaud, K. A. 1996, ASP Conf. Ser., 101, 17 [Google Scholar]

- Bachetti, M., Rana, V., Walton, D. J., et al. 2013, ApJ, 778, 163 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bachetti, M., Harrison, F. A., Walton, D. J., et al. 2014, Nature, 514, 202 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bachetti, M., Maccarone, T. J., Brightman, M., et al. 2020, ApJ, 891, 44 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Belloni, T. M. 2010, Lect. Notes Phys., 794, 53 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Brightman, M., Harrison, F. A., Bachetti, M., et al. 2019, ApJ, 873, 115 [Google Scholar]

- Burrows, D. N., Hill, J. E., Nousek, J. A., et al. 2005, Space Sci. Rev., 120, 165 [Google Scholar]

- Cardelli, J. A., Clayton, G. C., & Mathis, J. S. 1989, ApJ, 345, 245 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Carpano, S., Haberl, F., Maitra, C., & Vasilopoulos, G. 2018, MNRAS, 476, L45 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cash, W. 1979, ApJ, 228, 939 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Corbet, R. H. D., & Krimm, H. A. 2013, ApJ, 778, 45 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cseh, D., Kaaret, P., Corbel, S., et al. 2014, MNRAS, 439, L1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dauser, T., Middleton, M., & Wilms, J. 2017, MNRAS, 466, 2236 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Done, C., & Gierliński, M. 2003, MNRAS, 342, 1041 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, P. A., Beardmore, A. P., Page, K. L., et al. 2007, A&A, 469, 379 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, P. A., Beardmore, A. P., Page, K. L., et al. 2009, MNRAS, 397, 1177 [Google Scholar]

- Fabrika, S., Ueda, Y., Vinokurov, A., Sholukhova, O., & Shidatsu, M. 2015, Nat. Phys., 11, 551 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, S. A., Webb, N. A., Barret, D., Godet, O., & Rodrigues, J. M. 2009, Nature, 460, 73 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fender, R. P., Belloni, T. M., & Gallo, E. 2004, MNRAS, 355, 1105 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Feng, H., Tao, L., Kaaret, P., & Grisé, F. 2016, ApJ, 831, 117 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Foreman-Mackey, D., Agol, E., Ambikasaran, S., & Angus, R. 2017, AJ, 154, 220 [Google Scholar]

- Fürst, F., Walton, D., Harrison, F., et al. 2016, ApJ, 831, L14 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fürst, F., Walton, D. J., Heida, M., et al. 2018, A&A, 616, A186 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Gladstone, J., Done, C., & Gierlinski, M. 2007, MNRAS, 378, 13 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gladstone, J. C., Roberts, T. P., & Done, C. 2009, MNRAS, 397, 1836 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Godet, O., Barret, D., Webb, N. A., Farrell, S. A., & Gehrels, N. 2009, ApJ, 705, L109 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Grisé, F., Kaaret, P., Feng, H., Kajava, J. J. E., & Farrell, S. A. 2010, ApJ, 724, L148 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Grisé, F., Kaaret, P., Corbel, S., Cseh, D., & Feng, H. 2013, MNRAS, 433, 1023 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gúrpide, A., Godet, O., Koliopanos, F., Webb, N., & Olive, J.-F. 2021, A&A, 649, A104 [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J., Sun, M., Gu, W.-M., & Yi, T. 2019, MNRAS, 485, 2558 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, F. A., Craig, W. W., Christensen, F. E., et al. 2013, ApJ, 770, 103 [Google Scholar]

- Heida, M., Lau, R. M., Davies, B., et al. 2019, ApJ, 883, L34 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Heil, L. M., Vaughan, S., & Roberts, T. P. 2009, MNRAS, 397, 1061 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- HI4PI Collaboration (Bekhti, N. B., et al.) 2016, A&A, 594, A116 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Horne, J. H., & Baliunas, S. L. 1986, ApJ, 302, 757 [Google Scholar]

- Israel, G. L., Belfiore, A., Stella, L., et al. 2017, Science, 355, 817 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, F., Lumb, D., Altieri, B., et al. 2001, A&A, 365, L1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Kaaret, P., & Feng, H. 2009, ApJ, 702, 1679 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kaaret, P., Feng, H., & Roberts, T. P. 2017, ARA&A, 55, 303 [Google Scholar]

- Kalberla, P. M. W., Burton, W. B., Hartmann, D., et al. 2005, A&A, 440, 775 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima, T., Ohsuga, K., Mineshige, S., et al. 2012, ApJ, 752, 18 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- King, A. R. 2009, MNRAS, 393, L41 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Kong, A. K. H., Hu, C.-P., Lin, L. C.-C., et al. 2016, MNRAS, 461, 4395 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kozai, Y. 1962, AJ, 67, 591 [Google Scholar]

- Lau, R. M., Heida, M., Walton, D. J., et al. 2019, ApJ, 878, 71 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.-F. 2008, ApJS, 177, 181 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.-F., Bregman, J. N., & Seitzer, P. 2004, ApJ, 602, 249 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lomb, N. R. 1976, Astrophys. Space Sci., 39, 447 [Google Scholar]

- Mezcua, M. 2017, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D, 26, 1730021 [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, M. J., Roberts, T. P., Done, C., & Jackson, F. E. 2011, MNRAS, 411, 644 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, M. J., Heil, L., Pintore, F., Walton, D. J., & Roberts, T. P. 2015a, MNRAS, 447, 3243 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, M. J., Walton, D. J., Fabian, A., et al. 2015b, MNRAS, 454, 3134 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, M. J., Fragile, P. C., Bachetti, M., et al. 2018, MNRAS, 475, 154 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, M. J., Fragile, P. C., Ingram, A., & Roberts, T. P. 2019, MNRAS, 489, 282 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mondal, S., Rozanska, A., Baginska, P., Markowitz, A., & De Marco, B. 2021, A&A, 651, A54 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Mudelsee, M. 2002, Comput. Geosci., 28, 69 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan, R., Sadowski, A., & Soria, R. 2017, MNRAS, 469, 2997 [Google Scholar]

- Ohsuga, K., & Mineshige, S. 2007, ApJ, 670, 1283 [Google Scholar]

- Pakull, M. W., & Mirioni, L. 2002, ArXiv e-prints [arXiv:astro-ph/0202488] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, C., Alston, W., Soria, R., et al. 2017, MNRAS, 468, 2865 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, C., Mehdipour, M., Walton, D. J., et al. 2020, MNRAS, 491, 5702 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, C., Soria, R., Walton, D., et al. 2021, MNRAS, 505, 5058 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Poutanen, J., Lipunova, G., Fabrika, S., Butkevich, A. G., & Abolmasov, P. 2007, MNRAS, 377, 1187 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Quintin, E., Webb, N., Gúrpide, A., Bachetti, M., & Fürst, F. 2021, MNRAS, 503, 5485 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ray, P. S., Guillot, S., Ho, W. C. G., et al. 2019, ApJ, 879, 130 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Remillard, R. A., & McClintock, J. E. 2006, ARA&A, 44, 49 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, T. P., Kilgard, R. E., Warwick, R. S., Goad, M. R., & Ward, M. J. 2006, MNRAS, 371, 1877 [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, P. M. 1977, Stoch. Process. Appl., 6, 9 [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Castillo, G. A., Israel, G. L., Belfiore, A., et al. 2020, ApJ, 895, 60 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sathyaprakash, R., Roberts, T. P., Walton, D. J., et al. 2019, MNRAS, 488, L35 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Scargle, J. D. 1981, ApJS, 45, 1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Scargle, J. D. 1982, ApJ, 263, 835 [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, M., & Mudelsee, M. 2002, Comput. Geosci., 28, 421 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, M., & Stattegger, K. 1997, Comput. Geosci., 23, 929 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, G. 1978, Ann. Stat., 6, 461 [Google Scholar]

- Servillat, M., Farrell, S. A., Lin, D., et al. 2011, ApJ, 743, 6 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Shakura, N. I., & Sunyaev, R. A. 1973, A&A, 24, 337 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Stobbart, A.-M., Roberts, T. P., & Wilms, J. 2006, MNRAS, 368, 397 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Strüder, L., Briel, U., Dennerl, K., et al. 2001, A&A, 365, L18 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton, A. D., Roberts, T. P., & Middleton, M. J. 2013, MNRAS, 435, 1758 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi, S., Ohsuga, K., & Mineshige, S. 2013, PASJ, 65, 88 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tao, L., Kaaret, P., Feng, H., & Grisé, F. 2012, ApJ, 750, 110 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, L. J., & Charles, P. A. 2020, MNRAS, 495, L139 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tsygankov, S. S., Mushtukov, A. A., Suleimanov, V. F., & Poutanen, J. 2016, MNRAS, 457, 1101 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Turner, M. J. L., Abbey, A., Arnaud, M., et al. 2001, A&A, 365, L27 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart, R., & Soria, R. 2016, MNRAS, 456, 1859 [Google Scholar]

- VanderPlas, J. T. 2018, ApJS, 236, 16 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilopoulos, G., Haberl, F., Carpano, S., & Maitra, C. 2018, A&A, 620, L12 [NASA ADS] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilopoulos, G., Petropoulou, M., Koliopanos, F., et al. 2019, MNRAS, 488, 5225 [Google Scholar]

- Vasilopoulos, G., Lander, S. K., Koliopanos, F., & Bailyn, C. D. 2020, MNRAS, 491, 4949 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan, S., Uttley, P., Markowitz, A. G., et al. 2016, MNRAS, 461, 3145 [Google Scholar]

- Vinokurov, A., Fabrika, S., & Atapin, K. 2013, Astrophys. Bull., 68, 139 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Weisskopf, M. C., Tananbaum, H. D., Van Speybroeck, L. P., & O’Dell, S. L. 2000, Proc. SPIE, 4012, 2 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zdziarski, A. A., Wen, L., & Gierliński, M. 2007, MNRAS, 377, 1006 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L., Altamirano, D., Cúneo, V. A., et al. 2020, MNRAS, 499, 851 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

All Tables