| Issue |

A&A

Volume 624, April 2019

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A128 | |

| Number of page(s) | 13 | |

| Section | Stellar structure and evolution | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201834564 | |

| Published online | 25 April 2019 | |

The VLT-FLAMES Tarantula Survey

XXX. Red stragglers in the clusters Hodge 301 and SL 639⋆

1

Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, 38205 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain

e-mail: britavskiy@iac.es

2

Dpto. Astrofísica, Universidad de La Laguna, 38206 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain

3

ESA, European Space Astronomy Centre, Apdo. de Correos 78, 28691 Villanueva de la Cañda, Madrid, Spain

4

UK Astronomy Technology Centre, Royal Observatory, Blackford Hill, Edinburgh EH9 3HJ, UK

5

Argelander-Institut fü Astronomie der Universität Bonn, Auf dem Hügel 71, 53121 Bonn, Germany

6

Lennard-Jones Laboratories, Keele University, Staffordshire ST5 5BG, UK

7

School of Physical Sciences, The Open University, Walton Hall, Milton Keynes MK7 6AA, UK

8

Department of Physics, University of Oxford, Denys Wilkinson Building, Keble Road, Oxford OX1 3RH, UK

9

Zentrum für Astronomie der Universität Heidelberg, Astronomisches Rechen-Institut, Mönchhofstr. 12-14, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany

10

Heidelberger Institut für Theoretische Studien, Schloss-Wolfsbrunnenweg 35, 69118 Heidelberg, Germany

11

Departamento de Física Teórica e Experimental, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, CP 1641, Natal, RN 59072-970, Brazil

12

Institute of astrophysics, KU Leuven, Celestijnlaan 200D, 3001 Leuven, Belgium

13

Anton Pannenkoek Institute for Astronomy, University of Amsterdam, 1090 GE Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Received:

2

November

2018

Accepted:

26

February

2019

Aims. We estimate physical parameters for the late-type massive stars observed as part of the VLT-FLAMES Tarantula Survey (VFTS) in the 30 Doradus region of the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC).

Methods. The observational sample comprises 20 candidate red supergiants (RSGs) which are the reddest ((B − V) > 1 mag) and brightest (V < 16 mag) objects in the VFTS. We use optical and near-infrared (near-IR) photometry to estimate their temperatures and luminosities, and introduce the luminosity–age diagram to estimate their ages.

Results. We derive physical parameters for our targets, including temperatures from a new calibration of (J − Ks)0 colour for luminous cool stars in the LMC, luminosities from their J-band magnitudes (thence radii), and ages from comparisons with current evolutionary models. We show that interstellar extinction is a significant factor for our targets, highlighting the need to take it into account in the analysis of the physical parameters of RSGs. We find that some of the candidate RSGs could be massive AGB stars. The apparent ages of the RSGs in the Hodge 301 and SL 639 clusters show a significant spread (12–24 Myr). We also apply our approach to the RSG population of the relatively nearby NGC 2100 cluster, finding a similarly large spread.

Conclusions. We argue that the effects of mass transfer in binaries may lead to more massive and luminous RSGs (which we call “red stragglers”) than expected from single-star evolution, and that the true cluster ages correspond to the upper limit of the estimated RSG ages. In this way, the RSGs can serve as a new and potentially reliable age tracer in young star clusters. The corresponding analysis yields ages of 24−3+5 Myr for Hodge 301, 22−5+6 Myr for SL 639, and 23−2+4 Myr for NGC 2100.

Key words: stars: late-type / stars: fundamental parameters / supergiants / open clusters and associations: individual: NGC 2100 / open clusters and associations: individual: Hodge 301 / open clusters and associations: individual: SL 639

© ESO 2019

1. Introduction

Multi-epoch spectroscopy of an unprecedented sample of hot, massive stars in the 30 Doradus region of the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) was obtained by the VLT-FLAMES Tarantula Survey (VFTS; Evans et al. 2011; hereafter Paper I). To try to obtain an unbiased view of the massive star population of 30 Dor, no restrictions on colour were employed in the VFTS target list. This allowed for the potential inclusion of heavily reddened O-type stars that were expected to be present in the region. The resulting observed sample therefore included spectra of 91 later type stars in the region (with spectral types ranging from early A to M, see Table 3 of Paper I), plus spectra for an additional 102 stars thought to be mostly cool foreground stars. Among these two sets of cool stars are ∼20 stars that are known red supergiants (RSGs) or new candidate RSGs. In this work we investigate their stellar parameters and evolutionary status and discuss their ages in the context of the age of the 30 Dor region and its component stellar groups.

Red supergiants represent the final evolutionary stage of most massive stars before core collapse. These sources also represent the physically largest evolutionary phase possible for single stars, making RSGs critical for understanding the total fractions, mass ranges, and evolutionary states of interacting massive binaries (Levesque 2017). Indeed, the high incidence of interacting massive binaries (Sana et al. 2012) is expected to lead to about half of the type II supernova population resulting from post-interaction or merged stars (Podsiadlowski et al. 1992; Zapartas et al., in prep.) and to delayed supernovae relative to single star evolution (e.g. Zapartas et al. 2017). However, our understanding of these stars is hindered as correct determination of their physical parameters is still challenging as a consequence of the many uncertainties associated with modelling their complex atmospheres and winds (e.g. Massey et al. 2005; Levesque 2010; Davies et al. 2013). The evolutionary history of RSGs also depends on metallicity, initial mass, and probably binarity. The RSGs found in two clusters in the 30 Doradus region, Hodge 301 (Hodge 1988), and SL 639 (Shapley & Lindsay 1963), are particularly interesting because they enable study of two samples of RSGs that are each presumably coeval, as discussed later.

The wavelength coverage of the VFTS spectra was tailored to the analysis of OB-type stars (see Paper I). While useful to classify late-type stars, the coverage is not sufficient to estimate effective temperatures for RSGs, so we resorted to photometric methods to investigate the physical properties of our sample. Because there are a number of different approaches discussed in the literature, we briefly review these to assess potential advantages or drawbacks. A radial-velocity (RV) analysis of the VFTS spectroscopy of the sample is presented in a companion paper (Patrick et al. 2019).

This paper is organised as follows: Sect. 2 introduces our observational sample and Sect. 3 uses three photometric techniques to estimate the physical parameters of each star. We discuss our results in Sect. 4, and brief conclusions are presented in Sect. 5.

2. Observational sample

The VFTS included observations of 91 targets with spectral types ranging from A through to M (see Table 3 in Paper I). To select candidate RSGs for this study (and that of Patrick et al.) we used photometric criteria of (B − V) > 1 mag and V < 16 mag, as shown in the colour–magnitude diagram in Fig. 1 1.

|

Fig. 1. Colour–magnitude diagram for the VFTS targets highlighting the candidate RSGs studied and their membership of (or association with) the Hodge 301 and SL 639 clusters. The photometric criteria (V < 16 mag, (B − V) > 1 mag) are indicated by the dashed lines. |

Apparently foreground stars with RV < 100 km s−1 were excluded from the VFTS sample by inspection of the spectra at the outset of the project (see Sect. 2.2.2. of Paper I). At that stage, we also omitted a small number of cool stars that appeared to have RVs consistent with membership of the LMC but with very low signal-to-noise (S/N) spectra. In the context of this study and the RV analysis by Patrick et al. (2019), these low S/N spectra can still provide new insights. As a result we supplemented the primary VFTS targets with three stars that were omitted from Paper I but that appear to be members of the LMC. For future reference the full listing of the 102 previously discarded targets is given in Table A.1, where they are given identifications of the form 2xxx to distinguish them from the primary VFTS catalogue.

Given our focus on Hodge 301 and SL 639 we also included photometry of RSG WB97#5 (Walborn & Blades 1997; Grebel & Chu 2000) in Hodge 301, which was not observed in the VFTS because of crowding in the core of this cluster. For completeness, we also considered the brightest RSG in the region, Mk 9 (Melnick 1985); by chance this was not included in the VFTS sample owing to the high density of targets in and around R136, which limited the fibre allocations.

The observational parameters of the resulting 20 candidate RSGs are summarised in Table 1. They can loosely be characterised as belonging to one of three groups: associated with the older clusters Hodge 301 and SL 639, (loosely) associated with the young star-forming region NGC 2060, and those in the field with no clear association. The locations of our sample in the 30 Dor region are shown in Fig. 2; the spatial extents of the four clusters as defined by Evans et al. (2015) are also shown.

Observational properties of the late-type sample from the VFTS.

|

Fig. 2. Spatial distribution of the late-type stars in 30 Doradus and extents of the NGC 2070, NGC 2060, Hodge 301, and SL 639 clusters (as adopted by Evans et al. 2015). The larger clusters have indicative diameters of ∼70 pc and the smaller, older clusters have diameters of ∼9.5 pc. The image is from a V-band mosaic taken with the ESO Wide Field Imager on the 2.2 m telescope at La Silla (under programme 076.C-0888). |

Table 1 includes the mean RVs for each target from cross-correlation of the LR02 spectra (3960–4564 Å) with a synthetic spectrum from a MARCS model atmosphere (see Patrick et al. 2019). All but one have RVs consistent with the systemic line-of-sight velocity of the 30 Dor region. The exception is VFTS 793, which has a significantly lower velocity of RV = 187 ± 1 km s−1. The parallax (p) for VFTS 793 from the Gaia Data Release 2 (DR2) catalogue (Gaia Collaboration, Lindegren et al. 2018) is p = 0.1874 ± 0.016 mas, giving a distance modulus of 13.63 mag (≈5.3 kpc). As such, we consider this object as a foreground giant and exclude it from our subsequent analysis.

The RV estimates for the members of each cluster are in good agreement, and help to reveal three further stars which are potentially associated with the clusters. VFTS 236 is at a projected distance of only 14 pc from Hodge 301, and its RV estimate is nearly identical to those for VFTS 281 and 289. Similarly, the estimates for VFTS 852 and 2090 (at projected distances of ∼36 pc) are in good agreement with those for the two members of SL 639; see Patrick et al. (2019) for statistical arguments regarding membership of the respective clusters. For comparison, the mean RV for the remaining ten stars in Table 1 (excl. VFTS 793) is 271 ± 15 km s−1, i.e. the three spatially outlying stars from the clusters appear kinematically associated with them; cf. the general velocity dispersion of the cool stars across the region. The radius adopted for these two clusters by Evans et al. (2015) was a (knowingly conservative) ad hoc assumption of 20″ to delineate the sample to investigate the cluster ages. It is not unexpected that we find potentially associated stars at larger radii, and this finding is analogous to the RSG population in the nearby NGC 2100 cluster, which extends out to radii of nearly 30 pc with a similarly small velocity dispersion (Patrick et al. 2016). Thus, we consider these three stars (VFTS 236, 852, 2090) as candidate members of their respective clusters.

Our analysis used magnitudes from the following sources: V band from Paper I, I band from DENIS (Cioni et al. 2000), and JHKs bands from 2MASS (Skrutskie et al. 2006). Significant spectral variability is thought to occur in only a relatively small fraction of RSGs in the LMC (see discussion by Bonanos et al. 2009). However, semi-regular photometric variability is seen in many RSGs and to account for the fact that we are using heterogeneous catalogues we adopted systematic photometric uncertainties of 0.2 mag in the V band and 0.1 mag in the near-infrared (near-IR) bands (based on the average variability of well-studied RSGs, e.g. Josselin et al. 2000; Kiss et al. 2006; Yang & Jiang 2011, 2012). We caution that a small fraction of RSGs can undergo long-term variations of a magnitude or more in the visible, which may influence some of our results based on V-band magnitudes (cf. the near-IR), but our near-IR analysis should be robust to such effects.

3. Determination of physical parameters

3.1. Effective temperatures and luminosities of red supergiants

The effective temperatures of RSGs have been subject to a number of substantial studies in recent years. Levesque et al. (2005) used optical spectrophotometry and revised MARCS models to arrive at an effective temperature scale that was approximately 10% warmer than previously published values. They used this result to produce a “V − K” calibration of the effective temperature scale of RSGs and applied this to stars in the Magellanic Clouds (Levesque et al. 2006, 2007). However, Davies et al. (2013) argued that such optical analyses are strongly influenced by the strong TiO bands in RSG spectra, which are thought to be formed further out in the atmosphere, yielding lower temperatures than spectral fits to the optical and near-IR continuum. The V − K method shows good agreement with theory in the derived temperatures for bright field RSGs in the Magellanic Clouds (Levesque et al. 2006, 2007). However, in the case of the 30 Dor sample that have substantially higher extinctions (cf. Table 1) the application of this method requires a precise extinction determination for each target. Clearly, the V − K calibration is more sensitive to uncertainties in the V-band extinction, than to uncertainties in the Ks band.

Near-IR photometry can be useful to identify RSGs for spectroscopic follow-up (e.g. Patrick et al. 2015), for example, via their J − K colours (Nikolaev & Weinberg 2000). However, this photometry has not generally been used on its own to estimate physical parameters. Motivated by the above complications in using V − K, we investigated the use of near-IR photometry to estimate temperatures for our sample. These two approaches are now discussed below, as well as the use of single-band photometry to estimate stellar luminosities independently of Teff, as advocated by Davies et al. (2013).

3.1.1. V – K method

We initially estimated stellar parameters using the V − K method from Levesque et al. (2005). Aside from issues arising from using the TiO bands, we were interested to investigate this approach for comparison with other methods. As discussed, many of our sources have high extinction, so the most critical aspect with this method is to obtain reliable estimates for the optical extinction (AV) of each target. For this purpose we used the mean reddening of (morphologically normal) O-type stars from Walborn et al. (2014) within a search radius of  of each candidate RSG (typically yielding 3–5 O-type stars per target). Given estimates of E(B − V) for each target and adopting a ratio of total-to-selective extinction of RV = 4.48 ± 0.24 (De Marchi et al. 2016), we estimated the line-of-sight extinction from AV = E(B − V) × RV. The resulting extinction estimates and their uncertainties are listed in Table 1, where the values for most of the stars in Hodge 301 and SL 639 are identical simply because they are located so close to each other. Our estimated reddening towards Hodge 301 is in good agreement with the mean value of E(B − V) = 0.28 ± 0.05 from Grebel & Chu (2000).

of each candidate RSG (typically yielding 3–5 O-type stars per target). Given estimates of E(B − V) for each target and adopting a ratio of total-to-selective extinction of RV = 4.48 ± 0.24 (De Marchi et al. 2016), we estimated the line-of-sight extinction from AV = E(B − V) × RV. The resulting extinction estimates and their uncertainties are listed in Table 1, where the values for most of the stars in Hodge 301 and SL 639 are identical simply because they are located so close to each other. Our estimated reddening towards Hodge 301 is in good agreement with the mean value of E(B − V) = 0.28 ± 0.05 from Grebel & Chu (2000).

We then used the calibrations of Teff and bolometric corrections (BCK) as a function of V − K colour from Levesque et al. (2006, 2007). Their technique was based on fits to spectrophotometric observations of 36 RSGs in the LMC with synthetic spectra calculated from MARCS atmosphere models (Gustafsson et al. 2003, 2008). The general precision of the method, i.e. the standard deviation of temperature differences between the MARCS model fitting of the TiO region and the V − K calibration is ∼100 K (see Levesque 2017).

To apply this technique to our sample we dereddened our sources using (V − Ks)0 = (V − Ks) − 0.87 AV, based on AK = 0.13 AV (from the RV dependent extinction law of O’Donnell 1994, adopting RV = 4.48). We then calculated bolometric magnitudes from MBol = K − 0.13 AV − DM + BCK, in which we adopt a distance modulus to the LMC of 18.5 mag. Estimates of  and L(V − K) using their calibration are given in Table 2.

and L(V − K) using their calibration are given in Table 2.

Estimated fundamental physical parameters for candidate RSGs in 30 Dor.

3.1.2. J – K method

Bessell & Wood (1984) presented bolometric corrections for late-type stars in the Magellenic Clouds based on the (J − Ks) colours for 90 stars. Dorda et al. (2016) employed this relation for RSG stars, which entailed transforming the photometric system2 and then dereddening the colours for each target. The latter authors then used the results from Bessell & Wood (1984) to estimate BCK, hence luminosity (L(J − K)), analagous to the method in Sect. 3.1.1. We also investigated this approach for our sample.

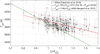

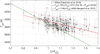

The (J − Ks) colours also appear to be useful to estimate effective temperatures of RSGs. Tabernero et al. (2018) presented temperatures for 217 RSGs in the LMC from fits to spectra of the 8400–8800 Å region using synthetic spectra calculated from 1D local thermodynamic equilibrium (LTE) KURUCZ models (Mészáros et al. 2012). This region is relatively free of telluric and molecular bands, and includes several Fe I lines and the strong calcium triplet lines in RSGs; e.g. Fig. 2 from Tabernero et al. 2018 (see also Britavskiy et al. 2014). As shown in Fig. 3, with the benefit of the large sample of results from Tabernero et al. (2018), a good correlation between Teff and (J − Ks) is revealed, with a linear fit (valid for 0.8 mag < (J − Ks) < 1.4 mag) described by

with a standard deviation of σ(Teff) = 140 K. To use this relation it is necessary to deredden the colour, i.e. (J − Ks)0 = (J − Ks) − E(J − K). From Schlegel et al. (1998) the near-IR reddening can be derived as E(J − K) = 0.535E(B − V), assuming RV = 3.1, with the reddening value of E(B − V) specific to each target. A calibration of Teff vs. (J − Ks)0 from Neugent et al. (2012) is also shown in Fig. 3, which was derived using a sample of yellow SGs ((J − Ks) < 0.9 mag) and candidate RSGs in the LMC. Their hotter sample and their fits with varying log g values (cf. the constant value of zero adopted by Tabernero et al. 2018) both contribute to the difference in slopes.

Our estimates of temperature ( , from Eq. (1)) and luminosity (L(J − K)) from this method are given in Table 2, in which the uncertainties on the former are the dispersion of 140 K in the calibration combined with the uncertainty in Teff arising from the uncertainty on the extinction. For consistency, the latter includes use of the same E(J − K) relation as for the Tabernero et al. (2018) sample, although using RV = 4.48 would lead to only a small change in colour and would have minimal impact on Teff (cf. the spread in Fig. 3).

, from Eq. (1)) and luminosity (L(J − K)) from this method are given in Table 2, in which the uncertainties on the former are the dispersion of 140 K in the calibration combined with the uncertainty in Teff arising from the uncertainty on the extinction. For consistency, the latter includes use of the same E(J − K) relation as for the Tabernero et al. (2018) sample, although using RV = 4.48 would lead to only a small change in colour and would have minimal impact on Teff (cf. the spread in Fig. 3).

|

Fig. 3. Effective temperature (Teff) vs. (J − Ks)0 colour for the 217 RSGs in the LMC from Tabernero et al. (2018). The red line indicates our linear fit to their data and the green line shows a previous calibration from a sample of yellow SGs and RSGs by Neugent et al. (2012). |

3.1.3. Single-band photometry

Empirical luminosity calibrations for single-band photometry of RSGs in the LMC and SMC were given by Davies et al. (2013, their Table 4). These calibrations assumed that the bolometric correction for the RSGs is constant for each given photometric band, a consequence of the near-uniform temperatures (to ±100 K) of the stars analysed by Davies et al. (2013). To investigate this method for our sample we used the available I-, J-, and Ks-band magnitudes, allowing us to test for the effects of extinction and to understand which band gives the most robust results. For each band (x), we calculated the absolute magnitude for each target as Mx = mx − Ax − DM, with estimates of extinction of AI = 0.54 AV, AJ = 0.32 AV, AK = 0.13 AV, based on the adopted value of RV = 4.48 by applying the extinction law of O’Donnell (1994). While the extinction coefficient for each band depends on spectral type (van Loon et al. 2003), taking into account that all our targets have K or early-M spectral types, the resulting difference in extinction is very small and we did not take it into account.

The resulting luminosity estimates (L(I), L(J), and L(K)) are listed in Table 2. The internal dispersion of the three bands for our stars was σ(log(L/L⊙)) = 0.05, although we note the calibration itself was limited to a sample of 19 RSGs in the Magellenic Clouds (Davies et al. 2013). As pointed out by Davies et al. (2013) a major advantage of this approach is that the resulting stellar luminosities are relatively insensitive to errors in the effective temperature since we are near the flux maximum of the spectral energy distribution. The resulting uncertainties in the luminosities for each method listed in Table 2 consist of the internal dispersion of the methods together with the individual uncertainties on the AV and RV values.

3.1.4. Comparison of the three methods

Estimates of temperature and luminosity for four of our targets are available from Tabernero et al. (2018). Our results from the three methods outlined above are compared with the findings from the latter work in the Hertzsprung–Russell (H–R) diagram in Fig. 4. Tabernero et al. (2018) calculated luminosities using the same J − K method as in our work, but without correcting for extinction, hence our estimates are all larger than theirs. We note that the three methods explored in this work give similar luminosity estimates once extinction is taken into account. Indeed, for our heavily reddened sample, it is critical to correctly account for interstellar extinction to obtain reliable estimates of their luminosities.

|

Fig. 4. Hertzsprung–Russell diagram showing results for four stars from the photometric methods discussed in Sect. 3 compared with published results from Tabernero et al. (2018, linked by the dashed lines to our results). |

The star with a large difference in Teff (cf. Tabernero et al. (2018)) is VFTS 2028 ( = 3914 ± 143 K in this work, cf. the published value of 4572 ± 75 K). From inspection of Fig. 3 we note that the published value is a substantial outlier; cf. the overall population of RSGs. The reason for such an outlier is that the Teff vs. (J − Ks)0 calibration shows the average trend, without taking into account information on the luminosity class and spectral type of RSGs. As shown by Tabernero et al. (2018), at a given bolometric luminosity the temperatures of RSGs can vary with different spectral types and luminosity classes (Ia–Ib), such that the temperature difference may be partly explained by their assumption of log g = 0. Published estimates of Teff and L are also available for VFTS 275 from Levesque et al. (2007, their LMC170452). This object has some photometric and spectral type variability (as reported by Levesque et al. 2007), but our estimates are in reasonable agreement.

= 3914 ± 143 K in this work, cf. the published value of 4572 ± 75 K). From inspection of Fig. 3 we note that the published value is a substantial outlier; cf. the overall population of RSGs. The reason for such an outlier is that the Teff vs. (J − Ks)0 calibration shows the average trend, without taking into account information on the luminosity class and spectral type of RSGs. As shown by Tabernero et al. (2018), at a given bolometric luminosity the temperatures of RSGs can vary with different spectral types and luminosity classes (Ia–Ib), such that the temperature difference may be partly explained by their assumption of log g = 0. Published estimates of Teff and L are also available for VFTS 275 from Levesque et al. (2007, their LMC170452). This object has some photometric and spectral type variability (as reported by Levesque et al. 2007), but our estimates are in reasonable agreement.

Based on the above discussion we therefore adopt L(J) and  in our subsequent analysis. The locations of our RSGs in the H–R diagram are shown in Fig. 6 together with appropriate evolutionary tracks from Brott et al. (2011) and Bressan et al. (2012, PARSEC models). The selection of L(J) is to mitigate against IR excesses arising from strong mass loss, which start to be significant in the H or K bands. Moreover, the peak of the spectral energy distribution for RSGs occurs in the I and J bands, and the effects of extinction in the J band are relatively low compared to the optical. Indeed, luminosities estimated from integration of the spectral energy distributions for RSGs in dwarf irregular galaxies in the Local Group, using either the I or J band, are found to be in good agreement (Britavskiy et al. 2019).

in our subsequent analysis. The locations of our RSGs in the H–R diagram are shown in Fig. 6 together with appropriate evolutionary tracks from Brott et al. (2011) and Bressan et al. (2012, PARSEC models). The selection of L(J) is to mitigate against IR excesses arising from strong mass loss, which start to be significant in the H or K bands. Moreover, the peak of the spectral energy distribution for RSGs occurs in the I and J bands, and the effects of extinction in the J band are relatively low compared to the optical. Indeed, luminosities estimated from integration of the spectral energy distributions for RSGs in dwarf irregular galaxies in the Local Group, using either the I or J band, are found to be in good agreement (Britavskiy et al. 2019).

We note that RSGs may experience strong mass loss that would lead to significant circumstellar extinction, as seen in some of the most luminous RSGs (e.g. Massey et al. 2005; Davies et al. 2008; Beasor & Davies 2018). Figure 5 shows the (J − Ks) vs. (Ks − [8.0]) colour–colour diagram for our sample, together with the distribution of L(J) vs. (Ks − [8.0]), where the 8.0 μm magnitudes ([8.0]) are from the Spitzer Space Telescope Legacy Survey (SAGE; Meixner et al. 2006). Three of our targets are not included in Fig. 5 as there were no [8.0] magnitudes available. A significant mid-IR excess (Ks − [8.0] > 0.5 mag; van Loon et al. 2003) is present in some of the more luminous RSGs (lower panel of Fig. 5). This indicates the presence of a dusty circumstellar envelope around these RSGs, and consequently, our luminosity estimates for these RSGs may be slightly underestimated. However, for the less luminous stars, we do not see similar evidence for circumstellar dust emission.

|

Fig. 5. Upper panel: (J − Ks) vs. (Ks − [8.0]) diagram for our sample. Lower panel: luminosity vs. (Ks − [8.0]) for the same stars. |

|

Fig. 6. Hertzsprung–Russell diagram for our targets, in which temperatures were estimated using the J − K approach and luminosities estimated from J-band magnitudes. The classifications of the targets based on our analysis are highlighted by the comments and filled region. Blue loops in the PARSEC evolutionary models from Bressan et al. (2012) are indicated by dashed lines (see text for details). |

3.2. Determination of masses, radii, and ages

Stellar radii for our sample were derived from the Stefan–Boltzmann relation, i.e. R/R⊙ = (L(J)/L⊙)0.5( /5770)−2. The uncertainties on the radii were calculated with the help of Monte Carlo simulations using the standard deviations in the Teff and L estimates. To estimate the initial masses of each target we interpolated their position in the H–R diagram, compared with the evolutionary tracks for an initial rotation rate of 150 km s−1 from Brott et al. (2011, which gives a detailed discussion of the treatment of rotation). The interpolation was based on the tracks for 7, 9, 12, 15, 20, 25 M⊙, to which we fit the position of RSGs based on their Teff and log(L/L⊙). The uncertainties of the derived masses were based on uncertainties of effective temperature and luminosity for each RSG. Obviously, the uncertainties in the luminosities of the targets play a major role in the total error budget of their mass. We then estimated logarithmic gravities from log g = log(M/M⊙) − 2log(R/R⊙) + 4.438. The resulting values of radius, mass, and gravity for each target are listed in Table 2.

/5770)−2. The uncertainties on the radii were calculated with the help of Monte Carlo simulations using the standard deviations in the Teff and L estimates. To estimate the initial masses of each target we interpolated their position in the H–R diagram, compared with the evolutionary tracks for an initial rotation rate of 150 km s−1 from Brott et al. (2011, which gives a detailed discussion of the treatment of rotation). The interpolation was based on the tracks for 7, 9, 12, 15, 20, 25 M⊙, to which we fit the position of RSGs based on their Teff and log(L/L⊙). The uncertainties of the derived masses were based on uncertainties of effective temperature and luminosity for each RSG. Obviously, the uncertainties in the luminosities of the targets play a major role in the total error budget of their mass. We then estimated logarithmic gravities from log g = log(M/M⊙) − 2log(R/R⊙) + 4.438. The resulting values of radius, mass, and gravity for each target are listed in Table 2.

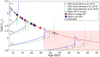

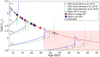

To investigate the ages of our targets we used a luminosity–age (L–Age) diagram, as shown in Fig. 7. This includes evolutionary tracks of single stars for the LMC with an initial rotational velocity of 150 km s−1 from Brott et al. (2011). The advantage of this approach is that it is not dependent on the estimated temperatures and the expected region for RSGs (highlighted by the dashed red lines) arises from steep increases in luminosity, from the start of the He-burning phase to the Hayashi limit at the end. From the tracks in Fig. 7 it is clear that the He-burning phase begins earlier than the highlighted range, when the luminosity begins to significantly rise. However, to observe such stars during this short initial rise (≈60 000 years) is very unlikely compared to the total duration of the He-burning phase (∼1.9 Myr). Therefore we do not consider this early stage further.

|

Fig. 7. Luminosity–age diagram for our sample of RSGs compared with evolutionary tracks for LMC metallicity from Brott et al. (2011), Georgy et al. (2013), and Bressan et al. (2012). The luminosities that RSGs are expected to occupy during the He-burning phase from the Brott et al. (2011) models are shown by red dashed lines. The red solid line corresponds to a fourth-degree polynomial interpolation of the RSG region: Age = −0.413L4 − 3.868L3 + 128.081L2 − 796.823L + 1534.899 (Myr), where L is in units of log(L/L⊙). This interpolation can be used for ages of 8–55 Myr. The filled red area highlights ages that would be excluded by a luminosity threshold of log(L/L⊙) = 4.3 dex being adopted as a lowest RSG luminosity limit according to Fig. 6. Using our derived stellar luminosities we can place each star in the RSG region to read off an evolutionary age, or age range, as shown. The cluster candidates are denoted by grey circles. |

To place our targets in Fig. 7 we matched the observational luminosities L(J) to the expected region for RSGs, yielding age estimates. The uncertainties in luminosity were then used to quantify the uncertainties on the age determination, simply by fitting the min/max L(J) within the RSG region in the figure. Estimated ages for each target are presented in Table 2.

To assess the impact of using different evolutionary models in the L–Age diagram, Fig. 7 also includes the “Geneva” tracks from Georgy et al. (2013) and the PARSEC models of Bressan et al. (2012). As in the models from Brott et al. (2011), the early onset of He-burning in the PARSEC models leads to a rapid increase in luminosity, meaning that the majority of the RSG lifetime spans a similarly small luminosity range for given initial mass.

For low-mass RSGs (M < 15 M⊙) blue loops appear in the Geneva tracks, and at lower masses (M < 12 M⊙) such blue loops also appear in the PARSEC models. This is due to the different treatment of mass loss and overshooting of the convective core in the models (Castro et al. 2014). Brott et al. (2011) calibrated the overshooting parameter using ≈15 M⊙ stars, while the PARSEC models were calibrated using stars more massive than 14 M⊙. In contrast, the Geneva models tuned this parameter for stars with M < 8 M⊙. We therefore chose the Brott et al. (2011) and Bressan et al. (2012) tracks as more applicable to our RSG sample (see Table 2); the differences between the age estimates using these two sets of tracks are small (within 1 Myr). This demonstrates that the uncertainties in the RSG luminosities play a more significant role in estimating their ages than employing different evolutionary tracks.

From the L–Age diagram we can see that the generally adopted minimum initial mass for RSGs of 8 M⊙ is equal to 35 Myr. However, taking into account the luminosity range of the He-burning phase, the age limit should be extended down to ∼26 Myr. The targets below this mass limit are generally considered as intermediate-mass stars, including massive AGB stars. There is no strong morphological separation using only luminosity as a parameter to distinguish RSGs from AGB stars. However, we consider the four targets from our sample with 4.0 < log(L/L⊙) < 4.3 as massive AGB stars or low-mass RSG candidates (see Figs. 6 and 7). Based on the L–Age diagram, we consider targets as bonafide RSGs if they have log(L/L⊙) > 4.3.

With spectroscopy at R ≲ 20 000 there is currently no reliable observational method to distinguish RSGs from massive AGBs (e.g. van Loon et al. 2005; Doherty et al. 2017; García-Hernández 2017). Atomic lines, for example, lithium and/or rubidium can potentially be used to distinguish these types of stars spectroscopically. The lithium and rubidium elements are produced in massive (M > 4 M⊙) O-rich AGB stars during the short, so-called hot bottom-burning phase, and by s-process via the 22Ne neutron source respectively. Thus, an overabundance of these elements can be observed during some AGB phases (García-Hernández et al. 2006, 2007). For definitive line identifications to investigate this further we require higher resolution spectroscopy over a wider wavelength range than the VFTS data.

Our analysis relies on the evolutionary models of Brott et al. (2011), in which uncertain physics, in particular rotational mixing and convective core overshooting, have been carefully calibrated to spectroscopic observations of massive stars in the LMC obtained within the VLT-FLAMES Survey of Massive Stars (Evans et al. 2005). Nevertheless, there are appreciable remaining uncertainties in models of massive-star evolution (Langer 2012) which lead to systematic differences in corresponding evolutionary tracks (e.g.Georgy et al. 2013; Choi et al. 2016; Limongi & Chieffi 2018). An assessment of these systematic differences, which are not reflected in our derived error bars, is beyond our ability to assess at this time. That is, even though they reflect our best estimate, the absolute values of the derived ages and masses may still be subject to changes. However, the age and mass differences will be affected much less, such that our hypothesis of an age spread partly arising from red stragglers should still hold.

4. Discussion

Assuming our objects have evolved as single stars, we can see from Fig. 7 that our sample of bona fide RSGs have an age range between approximately 9 Myr–24 Myr. This is not surprising since, despite the young ages of NGC 2060 and NGC 2070 (e.g. Ramírez-Agudelo et al. 2017; Schneider et al. 2018) there is also a significant population of massive stars with similar ages throughout the 30 Dor region (e.g. Sabbi et al. 2016; Schneider et al. 2018). Indeed, seven of our RSG sample are associated with either Hodge 301 or SL 639. Evans et al. (2015) derived ages of 10–15 Myr for both clusters from examination of the properties of the massive stars near their main sequence turn-offs. This “young” age for Hodge 301 contrasts strongly with the estimate of 26.5–31.5 Myr from Cignoni et al. (2016) from analysis of pre-main sequence turn-on stars in the observed colour–magnitude diagram. Cignoni et al. (2016) discussed potential reasons for this difference, noting that the ages implied by the blue and RSGs in this cluster also differ from their turn-on age, being intermediate to their turn-off and turn-on ages. In the present work we find that the RSGs associated with Hodge 301 have ages with a significant age spread of 14–24 Myr and, similarly, the RSGs in SL 639 have an age range between 12 Myr–22 Myr.

Binary evolution might help us understand the large dispersion in the derived cluster ages. Similar to the ubiquitous blue straggler phenomenon, i.e. main sequence stars found above the main sequence turn-off (Schneider et al. 2016), binary evolution can also produce RSGs above the red giant branch of the single stars in a star cluster, i.e. red stragglers. To illustrate this, we consider our results for Hodge 301, where the lowest luminosity RSG (VFTS 0289) has an estimated age of 24 Myr, corresponding to the lifetime of a single star of 10 M⊙. The merger of two initially 7 M⊙ stars at an age of 24 Myr would produce a 14 M⊙ star, which would soon thereafter evolve into a RSG. Its luminosity, if interpreted with only single stars in mind, would lead to an age of the cluster comparable to the lifetime of a 14 M⊙ star, i.e. only about 15 Myr. Therefore, the derived cluster age would be ∼60% too small.

The example of two merging 7 M⊙ stars, although not unrealistic, was chosen to demonstrate the possibility of producing red stragglers, and to show the order of magnitude of the effect on the derived cluster age. Of course, binaries with any initial mass ratio may produce mergers (see Fig. 12 of Wellstein et al. 2001). Binary population synthesis calculations are required to derive more accurate predictions of the red straggler distribution in star clusters (unfortunately unavailable in the recent work by Dorn-Wallenstein & Levesque 2018). However, as red stragglers are merely evolved blue stragglers, their fraction among the RSGs in a well-populated cluster can be expected to be significant, given that the blue straggler fraction near the main sequence turn-off is found to be up to 30% in young open clusters (Schneider et al. 2015).

We note that the latter effect, of blue stragglers, was not taken into account in the age determination of the turn-off stars in these clusters by Evans et al. (2015). Indeed in a recent study of an analagous Galactic cluster, NGC 3293, Proffitt et al. (2016) suggested that its brightest and apparently youngest blue supergiants might indeed be blue stragglers that are the result of binary evolution. The apparent age spread of the turn-off stars in Hodge 301 and SL 639 is further complicated as known Be stars are included in the H–R diagram presented by Evans et al. (2015). As well as being intrinsically variable, their stellar parameters are highly uncertain because of the impact of the circumstellar disc on extinction, apparent magnitude, and veiling of their absorption lines by the disc continuum emission (Lennon et al. 2005; Dunstall et al. 2011). Both clusters have significant numbers of Be stars: four of the 15 blue stars in Hodge 301, listed by Evans et al. (2015), are Be stars, and they also account for seven of the 13 blue stars in SL 639. If we exclude these Be stars from consideration we find that, of the remainder, ages have been published for three blue supergiants (BSGs) in each cluster (McEvoy et al. 2015), while ages for some of the non-BSG turn-off stars have been published by Schneider et al. (2018): four stars in Hodge 301 and two stars in SL 639. The mean ages of these stellar groups and their age ranges are listed in Table 3.

Comparison of the mean ages and age spread of identified red RSGs, BSGs, and non-Be, turn-off (TOF) stars in Hodge 301 and SL 639.

If the apparent age spreads of RSGs in a given star cluster are caused by this red straggler effect, the true cluster age would correspond simply to the age of the least luminous RSG as derived from single-star models. As shown in Fig. 6, the masses derived for our RSGs vary by less than a factor of two, and the red straggler interpretation may thus apply. In this context, the estimated age of Hodge 301 is 24 Myr (see Table 2), with an uncertainty according to the luminosity error of its least luminous RSG from Fig. 7. Similarly, we estimated an age of 22

Myr (see Table 2), with an uncertainty according to the luminosity error of its least luminous RSG from Fig. 7. Similarly, we estimated an age of 22 Myr for SL 639, although we note that this is defined by VFTS 852 and 2090, which are at larger radii from the cluster centre (see discussion in Sect. 1). Referring to Table 3, we see that the oldest stars in the RSG and TOF groups are similar, while the BSG stars are systematically younger than these limits. This picture is consistent with the oldest TOF and RSG stars more correctly reflecting the ages of these clusters, of 20–25 Myr, while the younger stars are red and blue stragglers as argued above.

Myr for SL 639, although we note that this is defined by VFTS 852 and 2090, which are at larger radii from the cluster centre (see discussion in Sect. 1). Referring to Table 3, we see that the oldest stars in the RSG and TOF groups are similar, while the BSG stars are systematically younger than these limits. This picture is consistent with the oldest TOF and RSG stars more correctly reflecting the ages of these clusters, of 20–25 Myr, while the younger stars are red and blue stragglers as argued above.

The general conclusion is that each evolutionary model would predict a small luminosity range of RSGs during He-burning phase. In this way, the red stragglers as binary products are required for the explanation of the luminosity spread of RSGs in a coeval cluster.

Davies et al. (2008) used the Geneva models to analyse 15 RSGs in the Galactic cluster RSGC1. These authors found that a single 12 Myr age isochrone described the complete population of RSGs, and attributed the spread in their luminosities to strong mass loss and uncertainties in the estimated cluster distance. The least luminous RSG in RSGC1 has log(L/L⊙) = 4.87 . Using our technique this corresponds to an age of 13

. Using our technique this corresponds to an age of 13 Myr, in good agreement with the estimate from Davies et al. (2008)

Myr, in good agreement with the estimate from Davies et al. (2008)

At this point, an important question arises: How should we interpret the spread of RSG luminosities in a coeval cluster? Is it due to single-star evolution (as discussed by Davies et al. 2008) or binary evolution (as suggested in the previous section)? As shown in Fig. 7, a single evolutionary track can indeed show a significant luminosity range during the He-burning phase, but as noted in the previous section, the early part of this range is very rapid and observing a RSG during the early onset of the He-burning phase is small. Thus, a given sample of coeval RSGs would be expected to occupy a narrow range of luminosity (∼0.2 dex in log(L/L⊙)). Although single-star evolution might account for some of the spread, we argue that the binary channel discussed above is also a potentially significant factor.

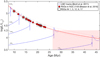

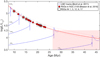

Prompted by these results and the low velocity dispersion reported by Patrick et al. (2016), we turned to the RSG population of the NGC 2100 cluster in the LMC. We used results from Beasor & Davies (2016) for 18 RSGs in NGC 2100 to construct the L–Age diagram shown in Fig. 8, giving an estimated age of  Myr for the least luminous RSG. In the figure we highlight the five stars that are most distant from the visual cluster centre (#1, 3, 6, 12, and 17 from Beasor & Davies 2016). We find an estimated age of 21.5 ± 3 Myr for the least luminous star in this subsample and provide support that they are coeval with the main body of the cluster. These estimates are in good agreement with the value of 20.6 ± 1.6 Myr derived from analysis of the star formation history of the cluster by Niederhofer et al. (2015). The reference measurements were based on all stellar populations in NGC 2100, including the main sequence stars and evolved red stars. Thus, the agreement in the age estimates is reasonable.

Myr for the least luminous RSG. In the figure we highlight the five stars that are most distant from the visual cluster centre (#1, 3, 6, 12, and 17 from Beasor & Davies 2016). We find an estimated age of 21.5 ± 3 Myr for the least luminous star in this subsample and provide support that they are coeval with the main body of the cluster. These estimates are in good agreement with the value of 20.6 ± 1.6 Myr derived from analysis of the star formation history of the cluster by Niederhofer et al. (2015). The reference measurements were based on all stellar populations in NGC 2100, including the main sequence stars and evolved red stars. Thus, the agreement in the age estimates is reasonable.

|

Fig. 8. Luminosity–age diagram as in Fig. 7 but using results from Beasor & Davies (2016) for RSGs in the relatively nearby NGC 2100 cluster. The five most distant RSGs from the visual cluster centre are highlighted to investigate potential spatial effects (see text for discussion). |

The large number of RSGs in NGC 2100 enables us to (very) roughly estimate the red straggler fraction in an example coeval cluster. By assuming the stellar lifetime scales as t ∼ M−2.5, the relative mass range scales as dM/M ∼ 0.4 dt/t. If we assume that the RSG phase is only 10% of the total lifetime, the relative mass range of single RSGs in a coeval cluster should be of order 5%. From the comparison in Fig. 8 the least luminous RSG in NGC 2100 has a mass of ≈10 M⊙. If we then consider that all RSGs with masses up to 10.5 M⊙ are effectively single, then eight stars in Fig. 8, (with L/L⊙ = 4.43–4.56 dex), could be single stars. The remaining ten stars are potentially red stragglers, giving a fraction of red stragglers in this coeval cluster of ∼55%.

There are large uncertainties on this fraction, but we conclude that this channel is potentially a significant factor in the observed populations of young, massive clusters. If the most luminous RSGs in a cluster are also those with the largest mass-loss rates (e.g. Beasor & Davies 2016), the latter might also help reveal potential red stragglers.

5. Conclusions

We have undertaken a photometric study of the RSG population of the 30 Doradus region in the LMC, which comprises 20 candidate RSGs. With the benefit of detailed analysis of the early-type stars from the VFTS, we used O-type stars around our cool-star sample to define the line-of-sight extinction towards each target. We estimated physical parameters for the sample, adopting the single-band technique to estimate luminosities as the most reliable approach, and we employed J-band photometry to mitigate the impact of extinction (at shorter wavelengths) and possible excesses from mass loss (at longer wavelengths). We showed that accurate correction of interstellar reddening is crucial and cannot be neglected in determination of the physical parameters of RSGs in young stellar clusters. It is possible that we underestimated the luminosities of the most luminous RSGs because of circumstellar dust – while this will affect the inferred age spread of a given population of RSGs, it will not influence the age estimated from the least luminous RSGs.

From analysis of the results for RSGs in the LMC from Tabernero et al. (2018) we present a new empirical calibration of Teff vs. (J − Ks)0 (Eq. (1)) to estimate temperatures of our sample. This relation should also serve as a useful tool in future extragalactic work where we often only have photometric information on populations of RSGs (Patrick & Britavskiy, in prep.). From our analysis we conclude that the sample contains 15 RSGs, four AGB (or low-luminosity RSG) stars, and one foreground object.

We introduced the luminosity–age diagram based on evolutionary tracks for the LMC to estimate ages of our RSGs, finding ranges between 14 Myr–24 Myr and 12 Myr–22 Myr, for Hodge 301 and SL 639, respectively. Assuming that binary mass transfer and mergers can produce more massive and luminous RSGs than expected from single-star evolution at a given age, analogous to the blue straggler phenomenon at the main sequence turn-off, we argue that the most luminous RSGs in these two star clusters are red stragglers. In this scenario, the least luminous RSGs in the clusters would effectively be the products of single-star evolution, and thus their ages derived from comparisons with single-star tracks are expected to represent the cluster ages. Based on these arguments, we estimate ages of 24 Myr for Hodge 301, and 22

Myr for Hodge 301, and 22 Myr for SL 639. We also applied our methods to the RSG population of NGC 2100, finding a similarly large apparent spread in the L–Age diagram and an estimated age of

Myr for SL 639. We also applied our methods to the RSG population of NGC 2100, finding a similarly large apparent spread in the L–Age diagram and an estimated age of  Myr.

Myr.

The two bluest targets that satisfy these criteria were not considered further as they were classified by Hénault-Brunet et al. (2012) as heavily reddened O-type stars.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous referee for helpful comments that have improved the manuscript. NB, AH, and LRP acknowledge support from grant AYA2015- 68012-C2- 1-P from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (MINECO) and also acknowledge support from the grant of Gobierno de Canarias (ProID2017010115). CJE is grateful to Rob Ivison for his sparkling motivation throughout this project. This publication makes use of data products from the Two Micron All Sky Survey, which is a joint project of the University of Massachusetts and the Infrared Processing and Analysis Center/California Institute of Technology, funded by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration and the National Science Foundation.

References

- Beasor, E. R., & Davies, B. 2016, MNRAS, 463, 1269 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Beasor, E. R., & Davies, B. 2018, MNRAS, 475, 55 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bessell, M. S., & Wood, P. R. 1984, PASP, 96, 247 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanos, A. Z., Massa, D. L., Sewilo, M., et al. 2009, AJ, 138, 1003 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bressan, A., Marigo, P., Girardi, L., et al. 2012, MNRAS, 427, 127 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Britavskiy, N. E., Bonanos, A. Z., Mehner, A., et al. 2014, A&A, 562, A75 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Britavskiy, N. E., Bonanos, A. Z., Herrero, A., et al. 2019, A&A, submitted [Google Scholar]

- Brott, I., de Mink, S. E., Cantiello, M., et al. 2011, A&A, 530, A115 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Castro, N., Fossati, L., Langer, N., et al. 2014, A&A, 570, L13 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J., Dotter, A., Conroy, C., et al. 2016, ApJ, 823, 102 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cignoni, M., Sabbi, E., van der Marel, R. P., et al. 2016, ApJ, 833, 154 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cioni, M.-R., Loup, C., Habing, H. J., et al. 2000, A&AS, 144, 235 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, B., Figer, D. F., Law, C. J., et al. 2008, ApJ, 676, 1016 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, B., Kudritzki, R.-P., Plez, B., et al. 2013, ApJ, 767, 3 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- De Marchi, G., Panagia, N., Sabbi, E., et al. 2016, MNRAS, 455, 4373 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, C. L., Gil-Pons, P., Siess, L., & Lattanzio, J. C. 2017, PASA, 34, e056 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dorda, R., Negueruela, I., González-Fernández, C., & Tabernero, H. M. 2016, A&A, 592, A16 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Dorn-Wallenstein, T. Z., & Levesque, E. M. 2018, ApJ, 867, 125 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dunstall, P. R., Brott, I., Dufton, P. L., et al. 2011, A&A, 536, A65 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, C. J., Smartt, S. J., Lee, J.-K., et al. 2005, A&A, 437, 467 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, C. J., Taylor, W. D., Hénault-Brunet, V., et al. 2011, A&A, 530, A108 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, C. J., Kennedy, M. B., Dufton, P. L., et al. 2015, A&A, 574, A13 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- García-Hernández, D. A. 2017, Mem. Soc. Astron. It., 88, 336 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- García-Hernández, D. A., García-Lario, P., Plez, B., et al. 2006, Science, 314, 1751 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- García-Hernández, D. A., García-Lario, P., Plez, B., et al. 2007, A&A, 462, 711 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Georgy, C., Ekström, S., Eggenberger, P., et al. 2013, A&A, 558, A103 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- González-Fernández, C., Dorda, R., Negueruela, I., & Marco, A. 2015, A&A, 578, A3 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Grebel, E. K., & Chu, Y.-H. 2000, AJ, 119, 787 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, B., Edvardsson, B., Eriksson, K., et al. 2003, in Stellar Atmosphere Modeling, eds. I. Hubeny, D. Mihalas, & K. Werner, ASP Conf. Ser., 288, 331 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, B., Edvardsson, B., Eriksson, K., et al. 2008, A&A, 486, 951 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Hénault-Brunet, V., Evans, C. J., Sana, H., et al. 2012, A&A, 546, A73 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge, P. 1988, PASP, 100, 1051 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Josselin, E., Blommaert, J. A. D. L., Groenewegen, M. A. T., Omont, A., & Li, F. L. 2000, A&A, 357, 225 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss, L. L., Szabó, G. M., & Bedding, T. R. 2006, MNRAS, 372, 1721 [Google Scholar]

- Langer, N. 2012, ARA&A, 50, 107 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lennon, D. J., Lee, J.-K., Dufton, P. L., & Ryans, R. S. I. 2005, A&A, 438, 265 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque, E. M. 2010, New Astron., 54, 1 [Google Scholar]

- Levesque, E. M. 2017, Astrophysics of Red Supergiants, 2514–3433 (IOP Publishing) [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque, E. M., Massey, P., Olsen, K. A. G., et al. 2005, ApJ, 628, 973 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque, E. M., Massey, P., Olsen, K. A. G., et al. 2006, ApJ, 645, 1102 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque, E. M., Massey, P., Olsen, K. A. G., & Plez, B. 2007, ApJ, 667, 202 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Limongi, M., & Chieffi, A. 2018, ApJS, 237, 13 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lindegren, L., Hernández, J., Bombrun, A., et al. 2018, A&A, 616, A2 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Massey, P., Plez, B., Levesque, E. M., et al. 2005, ApJ, 634, 1286 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- McEvoy, C. M., Dufton, P. L., Evans, C. J., et al. 2015, A&A, 575, A70 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Meixner, M., Gordon, K. D., Indebetouw, R., et al. 2006, AJ, 132, 2268 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Melnick, J. 1985, A&A, 153, 235 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Mészáros, S., Allende Prieto, C., Edvardsson, B., et al. 2012, AJ, 144, 120 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Neugent, K. F., Massey, P., Skiff, B., & Meynet, G. 2012, ApJ, 749, 177 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Niederhofer, F., Hilker, M., Bastian, N., & Silva-Villa, E. 2015, A&A, 575, A62 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaev, S., & Weinberg, M. D. 2000, ApJ, 542, 804 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell, J. E. 1994, ApJ, 422, 158 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Parker, J. W. 1993, AJ, 106, 560 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick, L. R., Evans, C. J., Davies, B., et al. 2015, ApJ, 803, 14 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick, L. R., Evans, C. J., Davies, B., et al. 2016, MNRAS, 458, 3968 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick, L. R., Lennon, D. J., Britavskiy, N., et al. 2019, A&A, 624, A129 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Podsiadlowski, P., Joss, P. C., & Hsu, J. J. L. 1992, ApJ, 391, 246 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Proffitt, C. R., Lennon, D. J., Langer, N., & Brott, I. 2016, ApJ, 824, 3 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Agudelo, O. H., Sana, H., de Koter, A., et al. 2017, A&A, 600, A81 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbi, E., Lennon, D. J., Anderson, J., et al. 2016, ApJS, 222, 11 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sana, H., de Mink, S. E., de Koter, A., et al. 2012, Science, 337, 444 [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel, D. J., Finkbeiner, D. P., & Davis, M. 1998, ApJ, 500, 525 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, F. R. N., Izzard, R. G., Langer, N., & de Mink, S. E. 2015, ApJ, 805, 20 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, F. R. N., Podsiadlowski, P., Langer, N., Castro, N., & Fossati, L. 2016, MNRAS, 457, 2355 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, F. R. N., Ramírez-Agudelo, O. H., Tramper, F., et al. 2018, A&A, 618, A73 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Selman, F., Melnick, J., Bosch, G., & Terlevich, R. 1999, A&A, 341, 98 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Shapley, H., & Lindsay, E. M. 1963, Ir. Astron. J., 6, 74 [Google Scholar]

- Skrutskie, M. F., Cutri, R. M., Stiening, R., et al. 2006, AJ, 131, 1163 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tabernero, H. M., Dorda, R., Negueruela, I., & González-Fernández, C. 2018, MNRAS, 476, 3106 [Google Scholar]

- van Loon, J. T., Gilmore, G. F., Omont, A., et al. 2003, MNRAS, 338, 857 [Google Scholar]

- van Loon, J. T., Cioni, M. R. L., Zijlstra, A. A., & Loup, C. 2005, A&A, 438, 273 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Walborn, N. R., & Blades, J. C. 1997, ApJS, 112, 457 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Walborn, N. R., Sana, H., Simón-Díaz, S., et al. 2014, A&A, 564, A40 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Wellstein, S., Langer, N., & Braun, H. 2001, A&A, 369, 939 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M., & Jiang, B. W. 2011, ApJ, 727, 53 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M., & Jiang, B. W. 2012, ApJ, 754, 35 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zapartas, E., de Mink, S. E., Izzard, R. G., et al. 2017, A&A, 601, A29 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Zaritsky, D., Harris, J., Thompson, I. B., & Grebel, E. K. 2004, AJ, 128, 1606 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Appendix A: Additional cool stars

Observational parameters of stars with FLAMES spectroscopy but previously omitted from the VFTS catalogue.

All Tables

Comparison of the mean ages and age spread of identified red RSGs, BSGs, and non-Be, turn-off (TOF) stars in Hodge 301 and SL 639.

Observational parameters of stars with FLAMES spectroscopy but previously omitted from the VFTS catalogue.

All Figures

|

Fig. 1. Colour–magnitude diagram for the VFTS targets highlighting the candidate RSGs studied and their membership of (or association with) the Hodge 301 and SL 639 clusters. The photometric criteria (V < 16 mag, (B − V) > 1 mag) are indicated by the dashed lines. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2. Spatial distribution of the late-type stars in 30 Doradus and extents of the NGC 2070, NGC 2060, Hodge 301, and SL 639 clusters (as adopted by Evans et al. 2015). The larger clusters have indicative diameters of ∼70 pc and the smaller, older clusters have diameters of ∼9.5 pc. The image is from a V-band mosaic taken with the ESO Wide Field Imager on the 2.2 m telescope at La Silla (under programme 076.C-0888). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3. Effective temperature (Teff) vs. (J − Ks)0 colour for the 217 RSGs in the LMC from Tabernero et al. (2018). The red line indicates our linear fit to their data and the green line shows a previous calibration from a sample of yellow SGs and RSGs by Neugent et al. (2012). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4. Hertzsprung–Russell diagram showing results for four stars from the photometric methods discussed in Sect. 3 compared with published results from Tabernero et al. (2018, linked by the dashed lines to our results). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5. Upper panel: (J − Ks) vs. (Ks − [8.0]) diagram for our sample. Lower panel: luminosity vs. (Ks − [8.0]) for the same stars. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 6. Hertzsprung–Russell diagram for our targets, in which temperatures were estimated using the J − K approach and luminosities estimated from J-band magnitudes. The classifications of the targets based on our analysis are highlighted by the comments and filled region. Blue loops in the PARSEC evolutionary models from Bressan et al. (2012) are indicated by dashed lines (see text for details). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 7. Luminosity–age diagram for our sample of RSGs compared with evolutionary tracks for LMC metallicity from Brott et al. (2011), Georgy et al. (2013), and Bressan et al. (2012). The luminosities that RSGs are expected to occupy during the He-burning phase from the Brott et al. (2011) models are shown by red dashed lines. The red solid line corresponds to a fourth-degree polynomial interpolation of the RSG region: Age = −0.413L4 − 3.868L3 + 128.081L2 − 796.823L + 1534.899 (Myr), where L is in units of log(L/L⊙). This interpolation can be used for ages of 8–55 Myr. The filled red area highlights ages that would be excluded by a luminosity threshold of log(L/L⊙) = 4.3 dex being adopted as a lowest RSG luminosity limit according to Fig. 6. Using our derived stellar luminosities we can place each star in the RSG region to read off an evolutionary age, or age range, as shown. The cluster candidates are denoted by grey circles. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 8. Luminosity–age diagram as in Fig. 7 but using results from Beasor & Davies (2016) for RSGs in the relatively nearby NGC 2100 cluster. The five most distant RSGs from the visual cluster centre are highlighted to investigate potential spatial effects (see text for discussion). |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.