| Issue |

A&A

Volume 691, November 2024

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A62 | |

| Number of page(s) | 20 | |

| Section | Cosmology (including clusters of galaxies) | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202451230 | |

| Published online | 30 October 2024 | |

Euclid preparation

L. Calibration of the halo linear bias in Λ(v)CDM cosmologies

1

INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Trieste,

Via G. B. Tiepolo 11,

34143

Trieste,

Italy

2

INFN, Sezione di Trieste,

Via Valerio 2,

34127

Trieste TS,

Italy

3

IFPU, Institute for Fundamental Physics of the Universe,

via Beirut 2,

34151

Trieste,

Italy

4

ICSC – Centro Nazionale di Ricerca in High Performance Computing, Big Data e Quantum Computing,

Via Magnanelli 2,

Bologna,

Italy

5

Ludwig-Maximilians-University,

Schellingstrasse 4,

80799

Munich,

Germany

6

Donostia International Physics Center (DIPC),

Paseo Manuel de Lardizabal, 4,

20018

Donostia-San Sebastián, Guipuzkoa,

Spain

7

IKERBASQUE, Basque Foundation for Science,

48013

Bilbao,

Spain

8

Universitäts-Sternwarte München, Fakultät für Physik, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München,

Scheinerstrasse 1,

81679

München,

Germany

9

Dipartimento di Fisica – Sezione di Astronomia, Università di Trieste,

Via Tiepolo 11,

34131

Trieste,

Italy

10

Department of Astrophysics, University of Zurich,

Winterthurerstrasse 190,

8057

Zurich,

Switzerland

11

Université Paris-Saclay, CNRS, Institut d’astrophysique spatiale,

91405

Orsay,

France

12

Institut für Theoretische Physik, University of Heidelberg,

Philosophenweg 16,

69120

Heidelberg,

Germany

13

INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Brera,

Via Brera 28,

20122

Milano,

Italy

14

SISSA, International School for Advanced Studies,

Via Bonomea 265,

34136

Trieste TS,

Italy

15

Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia, Università di Bologna,

Via Gobetti 93/2,

40129

Bologna,

Italy

16

INAF-Osservatorio di Astrofisica e Scienza dello Spazio di Bologna,

Via Piero Gobetti 93/3,

40129

Bologna,

Italy

17

INFN-Sezione di Bologna,

Viale Berti Pichat 6/2,

40127

Bologna,

Italy

18

Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics,

Giessenbachstr. 1,

85748

Garching,

Germany

19

INAF-Osservatorio Astrofisico di Torino,

Via Osservatorio 20,

10025

Pino Torinese (TO),

Italy

20

Dipartimento di Fisica, Università di Genova,

Via Dodecaneso 33,

16146,

Genova,

Italy

21

INFN-Sezione di Genova,

Via Dodecaneso 33,

16146

Genova,

Italy

22

Department of Physics “E. Pancini”, University Federico II,

Via Cinthia 6,

80126,

Napoli,

Italy

23

INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Capodimonte,

Via Moiariello 16,

80131

Napoli,

Italy

24

INFN section of Naples,

Via Cinthia 6,

80126

Napoli,

Italy

25

Aix-Marseille Université, CNRS, CNES, LAM,

Marseille,

France

26

Dipartimento di Fisica, Università degli Studi di Torino,

Via P. Giuria 1,

10125

Torino,

Italy

27

INFN-Sezione di Torino,

Via P. Giuria 1,

10125

Torino,

Italy

28

INAF – IASF Milano,

Via Alfonso Corti 12,

20133

Milano,

Italy

29

Centro de Investigaciones Energéticas, Medioambientales y Tecnológicas (CIEMAT),

Avenida Complutense 40,

28040

Madrid,

Spain

30

Port d’Informació Científica,

Campus UAB, C. Albareda s/n,

08193

Bellaterra (Barcelona),

Spain

31

Institute for Theoretical Particle Physics and Cosmology (TTK), RWTH Aachen University,

52056

Aachen,

Germany

32

INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Roma,

Via Frascati 33,

00078

Monteporzio Catone,

Italy

33

Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia “Augusto Righi” – Alma Mater Studiorum Università di Bologna,

Viale Berti Pichat 6/2,

40127

Bologna,

Italy

34

Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias,

Calle Vía Láctea s/n,

38204

San Cristóbal de La Laguna,

Tenerife,

Spain

35

Institute for Astronomy, University of Edinburgh,

Royal Observatory, Blackford Hill,

Edinburgh

EH9 3HJ,

UK

36

Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics, Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Manchester,

Oxford Road,

Manchester

M13 9PL,

UK

37

European Space Agency/ESRIN,

Largo Galileo Galilei 1,

00044

Frascati,

Roma,

Italy

38

ESAC/ESA, Camino Bajo del Castillo,

s/n., Urb. Villafranca del Castillo,

28692

Villanueva de la Cañada, Madrid,

Spain

39

Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1,

CNRS/IN2P3, IP2I Lyon, UMR 5822,

Villeurbanne

69100,

France

40

Institute of Physics, Laboratory of Astrophysics, Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL),

Observatoire de Sauverny,

1290

Versoix,

Switzerland

41

UCB Lyon 1, CNRS/IN2P3, IUF, IP2I Lyon,

4 rue Enrico Fermi,

69622

Villeurbanne,

France

42

Departamento de Física, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa,

Edifício C8, Campo Grande,

1749-016

Lisboa,

Portugal

43

Instituto de Astrofísica e Ciências do Espaço, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa,

Campo Grande,

1749-016

Lisboa,

Portugal

44

Department of Astronomy, University of Geneva,

ch. d’Ecogia 16,

1290

Versoix,

Switzerland

45

INAF-Istituto di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali,

via del Fosso del Cavaliere, 100,

00100

Roma,

Italy

46

INFN-Padova,

Via Marzolo 8,

35131

Padova,

Italy

47

Université Paris-Saclay, Université Paris Cité, CEA, CNRS, AIM,

91191

Gif-sur-Yvette,

France

48

Institut d’Estudis Espacials de Catalunya (IEEC),

Edifici RDIT, Campus UPC,

08860

Castelldefels, Barcelona,

Spain

49

Institute of Space Sciences (ICE, CSIC),

Campus UAB, Carrer de Can Magrans, s/n,

08193

Barcelona,

Spain

50

Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare,

Sezione di Bologna, Via Irnerio 46,

40126

Bologna,

Italy

51

FRACTAL S.L.N.E.,

calle Tulipán 2, Portal 13 1A,

28231

Las Rozas de Madrid,

Spain

52

INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova,

Via dell’Osservatorio 5,

35122

Padova,

Italy

53

Dipartimento di Fisica “Aldo Pontremoli”, Università degli Studi di Milano,

Via Celoria 16,

20133

Milano,

Italy

54

Institute of Theoretical Astrophysics, University of Oslo,

PO Box 1029

Blindern,

0315

Oslo,

Norway

55

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology,

4800 Oak Grove Drive,

Pasadena,

CA

91109,

USA

56

Felix Hormuth Engineering,

Goethestr. 17,

69181

Leimen,

Germany

57

Technical University of Denmark,

Elektrovej 327,

2800

Kgs. Lyngby,

Denmark

58

Cosmic Dawn Center (DAWN),

Denmark

59

Université Paris-Saclay, CNRS/IN2P3, IJCLab,

91405

Orsay,

France

60

Institut de Recherche en Astrophysique et Planétologie (IRAP), Université de Toulouse, CNRS, UPS, CNES,

14 Av. Edouard Belin,

31400

Toulouse,

France

61

Max-Planck-Institut für Astronomie,

Königstuhl 17,

69117

Heidelberg,

Germany

62

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center,

Greenbelt,

MD

20771,

USA

63

Department of Physics and Astronomy, University College London,

Gower Street,

London

WC1E 6BT,

UK

64

Department of Physics and Helsinki Institute of Physics,

Gustaf Hällströmin katu 2,

00014

University of Helsinki,

Finland

65

Aix-Marseille Université, CNRS/IN2P3, CPPM,

Marseille,

France

66

Université de Genève, Département de Physique Théorique and Centre for Astroparticle Physics,

24 quai Ernest-Ansermet,

1211

Genève 4,

Switzerland

67

Department of Physics,

PO Box 64,

00014

University of Helsinki,

Finland

68

Helsinki Institute of Physics,

Gustaf Hällströmin katu 2, University of Helsinki,

Helsinki,

Finland

69

NOVA optical infrared instrumentation group at ASTRON,

Oude Hoogeveensedijk 4,

7991PD,

Dwingeloo,

The Netherlands

70

Universität Bonn, Argelander-Institut für Astronomie,

Auf dem Hügel 71,

53121

Bonn,

Germany

71

INFN-Sezione di Roma,

Piazzale Aldo Moro 2, c/o Dipartimento di Fisica, Edificio G. Marconi,

00185

Roma,

Italy

72

Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia “Augusto Righi” – Alma Mater Studiorum Università di Bologna,

via Piero Gobetti 93/2,

40129

Bologna,

Italy

73

Department of Physics, Institute for Computational Cosmology, Durham University,

South Road

DH1 3LE,

UK

74

Université Côte d’Azur, Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur, CNRS, Laboratoire Lagrange,

Bd de l’Observatoire, CS 34229,

06304

Nice cedex 4,

France

75

University of Applied Sciences and Arts of Northwestern Switzerland, School of Engineering,

5210

Windisch,

Switzerland

76

Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris,

98bis Boulevard Arago,

75014

Paris,

France

77

Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris, UMR 7095, CNRS, and Sorbonne Université,

98 bis boulevard Arago,

75014

Paris,

France

78

European Space Agency/ESTEC,

Keplerlaan 1,

2201 AZ

Noordwijk,

The Netherlands

79

Institut de Física d’Altes Energies (IFAE), The Barcelona Institute of Science and Technology,

Campus UAB,

08193

Bellaterra (Barcelona),

Spain

80

DARK, Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen,

Jagtvej 155,

2200

Copenhagen,

Denmark

81

Waterloo Centre for Astrophysics, University of Waterloo,

Waterloo,

Ontario

N2L 3G1,

Canada

82

Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Waterloo,

Waterloo,

Ontario

N2L 3G1,

Canada

83

Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics,

Waterloo,

Ontario

N2L 2Y5,

Canada

84

Space Science Data Center, Italian Space Agency,

via del Politecnico snc,

00133

Roma,

Italy

85

Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales – Centre spatial de Toulouse,

18 avenue Edouard Belin,

31401

Toulouse Cedex 9,

France

86

Institute of Space Science,

Str. Atomistilor, nr. 409 Măgurele,

Ilfov

077125,

Romania

87

Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia “G. Galilei”, Università di Padova,

Via Marzolo 8,

35131

Padova,

Italy

88

Université St Joseph; Faculty of Sciences,

Beirut,

Lebanon

89

Departamento de Física, FCFM, Universidad de Chile,

Blanco Encalada 2008,

Santiago,

Chile

90

Satlantis, University Science Park,

Sede Bld 48940,

Leioa-Bilbao,

Spain

91

Instituto de Astrofísica e Ciências do Espaço, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa,

Tapada da Ajuda,

1349-018

Lisboa,

Portugal

92

Universidad Politécnica de Cartagena, Departamento de Electrónica y Tecnología de Computadoras,

Plaza del Hospital 1,

30202

Cartagena,

Spain

93

INFN-Bologna,

Via Irnerio 46,

40126

Bologna,

Italy

94

Kapteyn Astronomical Institute, University of Groningen,

PO Box 800,

9700 AV

Groningen,

The Netherlands

95

Infrared Processing and Analysis Center, California Institute of Technology,

Pasadena,

CA

91125,

USA

96

INAF, Istituto di Radioastronomia,

Via Piero Gobetti 101,

40129

Bologna,

Italy

97

Astronomical Observatory of the Autonomous Region of the Aosta Valley (OAVdA),

Loc. Lignan 39,

11020 Nus

(Aosta Valley),

Italy

98

Junia, EPA department,

41 Bd Vauban,

59800

Lille,

France

99

Instituto de Física Teórica UAM-CSIC,

Campus de Cantoblanco,

28049

Madrid,

Spain

100

CERCA/ISO, Department of Physics, Case Western Reserve University,

10900 Euclid Avenue,

Cleveland,

OH

44106,

USA

101

Laboratoire Univers et Théorie, Observatoire de Paris, Université PSL, Université Paris Cité, CNRS,

92190

Meudon,

France

102

INFN – Sezione di Milano,

Via Celoria 16,

20133

Milano,

Italy

103

Departamento de Física Fundamental. Universidad de Salamanca.

Plaza de la Merced s/n.,

37008

Salamanca,

Spain

104

Departamento de Astrofísica, Universidad de La Laguna,

38206,

La Laguna,

Tenerife,

Spain

105

Dipartimento di Fisica e Scienze della Terra, Università degli Studi di Ferrara,

Via Giuseppe Saragat 1,

44122

Ferrara,

Italy

106

Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare, Sezione di Ferrara,

Via Giuseppe Saragat 1,

44122

Ferrara,

Italy

107

Université de Strasbourg, CNRS, Observatoire astronomique de Strasbourg, UMR 7550,

67000

Strasbourg,

France

108

Center for Data-Driven Discovery, Kavli IPMU (WPI), UTIAS, The University of Tokyo,

Kashiwa, Chiba

277-8583,

Japan

109

Max-Planck-Institut für Physik,

Boltzmannstr. 8,

85748

Garching,

Germany

110

Minnesota Institute for Astrophysics, University of Minnesota,

116 Church St SE,

Minneapolis,

MN

55455,

USA

111

Institute Lorentz, Leiden University,

Niels Bohrweg 2,

2333 CA

Leiden,

The Netherlands

112

Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii,

2680 Woodlawn Drive,

Honolulu,

HI

96822,

USA

113

Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of California Irvine,

Irvine,

CA

92697,

USA

114

Department of Astronomy & Physics and Institute for Computational Astrophysics, Saint Mary’s University,

923 Robie Street, Halifax,

Nova Scotia

B3H 3C3,

Canada

115

Departamento Física Aplicada, Universidad Politécnica de Cartagena,

Campus Muralla del Mar,

30202

Cartagena, Murcia,

Spain

116

Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias (IAC); Departamento de Astrofísica, Universidad de La Laguna (ULL),

38200

La Laguna, Tenerife,

Spain

117

Department of Physics, Oxford University,

Keble Road,

Oxford

OX1 3RH,

UK

118

Université Paris Cité, CNRS,

Astroparticule et Cosmologie,

75013

Paris,

France

119

CEA Saclay, DFR/IRFU,

Service d’Astrophysique, Bat. 709,

91191

Gif-sur-Yvette,

France

120

Institute of Cosmology and Gravitation, University of Portsmouth,

Portsmouth

PO1 3FX,

UK

121

Department of Computer Science, Aalto University,

PO Box 15400,

Espoo

00 076,

Finland

122

Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias,

c/ Via Lactea s/n,

La Laguna

38200,

Spain.

Departamento de Astrofísica de la Universidad de La Laguna, Avda. Francisco Sanchez,

La Laguna,

38200,

Spain

123

Ruhr University Bochum, Faculty of Physics and Astronomy, Astronomical Institute (AIRUB), German Centre for Cosmological Lensing (GCCL),

44780

Bochum,

Germany

124

Univ. Grenoble Alpes, CNRS, Grenoble INP, LPSC-IN2P3,

53, Avenue des Martyrs,

38000

Grenoble,

France

125

Department of Physics and Astronomy,

Vesilinnantie 5,

20014

University of Turku,

Finland

126

Serco for European Space Agency (ESA),

Camino bajo del Castillo, s/n, Urbanizacion Villafranca del Castillo, Villanueva de la Cañada,

28692

Madrid,

Spain

127

ARC Centre of Excellence for Dark Matter Particle Physics,

Melbourne,

Australia

128

Centre for Astrophysics & Supercomputing, Swinburne University of Technology,

Hawthorn, Victoria

3122,

Australia

129

School of Physics and Astronomy, Queen Mary University of London,

Mile End Road,

London

E1 4NS,

UK

130

Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of the Western Cape,

Bellville,

Cape Town

7535,

South Africa

131

ICTP South American Institute for Fundamental Research, Instituto de Física Teórica, Universidade Estadual Paulista,

São Paulo,

Brazil

132

IRFU, CEA, Université Paris-Saclay

91191

Gif-sur-Yvette Cedex,

France

133

Oskar Klein Centre for Cosmoparticle Physics, Department of Physics, Stockholm University,

Stockholm

106 91,

Sweden

134

Astrophysics Group, Blackett Laboratory, Imperial College London,

London

SW7 2AZ,

UK

135

INAF-Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri,

Largo E. Fermi 5,

50125

Firenze,

Italy

136

Dipartimento di Fisica, Sapienza Università di Roma,

Piazzale Aldo Moro 2,

00185

Roma,

Italy

137

Centro de Astrofísica da Universidade do Porto,

Rua das Estrelas,

4150-762

Porto,

Portugal

138

Instituto de Astrofísica e Ciências do Espaço, Universidade do Porto, CAUP,

Rua das Estrelas,

4150-762

Porto,

Portugal

139

HE Space for European Space Agency (ESA),

Camino bajo del Castillo, s/n, Urbanizacion Villafranca del Castillo, Villanueva de la Cañada,

28692

Madrid,

Spain

140

Aurora Technology for European Space Agency (ESA),

Camino bajo del Castillo, s/n, Urbanizacion Villafranca del Castillo, Villanueva de la Cañada,

28692

Madrid,

Spain

141

Institute of Astronomy, University of Cambridge,

Madingley Road,

Cambridge

CB3 0HA,

UK

142

Dipartimento di Fisica, Università degli studi di Genova, and INFN-Sezione di Genova,

via Dodecaneso 33,

16146

Genova,

Italy

143

Theoretical astrophysics, Department of Physics and Astronomy, Uppsala University,

Box 515,

751 20

Uppsala,

Sweden

144

Department of Physics, Royal Holloway, University of London,

TW20 0EX,

UK

145

Mullard Space Science Laboratory, University College London,

Holmbury St Mary, Dorking,

Surrey

RH5 6NT,

UK

146

Department of Astrophysical Sciences, Peyton Hall, Princeton University,

Princeton,

NJ

08544,

USA

147

Niels Bohr Institute, University of Copenhagen,

Jagtvej 128,

2200

Copenhagen,

Denmark

148

Center for Cosmology and Particle Physics, Department of Physics, New York University,

New York,

NY

10003,

USA

149

Center for Computational Astrophysics, Flatiron Institute,

162 5th Avenue,

New York,

NY

10010,

USA

★ Corresponding author; tiago.batalha@inaf.it

Received:

24

June

2024

Accepted:

2

September

2024

The Euclid mission, designed to map the geometry of the dark Universe, presents an unprecedented opportunity for advancing our understanding of the cosmos through its photometric galaxy cluster survey. Central to this endeavor is the accurate calibration of the mass- and redshift-dependent halo bias (HB), which is the focus of this paper. Our aim is to enhance the precision of HB predictions, which is crucial for deriving cosmological constraints from the clustering of galaxy clusters. Our study is based on the peak-background split (PBS) model linked to the halo mass function (HMF), and it extends it with a parametric correction to precisely align with results from an extended set of N-body simulations carried out with the OpenGADGET3 code. Employing simulations with fixed and paired initial conditions, we meticulously analyzed the matter-halo cross-spectrum and modeled its covariance using a large number of mock catalogs generated with Lagrangian perturbation theory simulations with the PINOCCHIO code. This ensures a comprehensive understanding of the uncertainties in our HB calibration. Our findings indicate that the calibrated HB model is remarkably resilient against changes in cosmological parameters, including those involving massive neutrinos. The robustness and adaptability of our calibrated HB model provide an important contribution to the cosmological exploitation of the cluster surveys to be provided by the Euclid mission. This study highlights the necessity of continuously refining the calibration of cosmological tools such as the HB to match the advancing quality of observational data. As we project the impact of our calibrated model on cosmological constraints, we find that given the sensitivity of the Euclid survey, a miscalibration of the HB could introduce biases in cluster cosmology analysis. Our work fills this critical gap, ensuring the HB calibration matches the expected precision of the Euclid survey.

Key words: cosmological parameters / cosmology: theory / large-scale structure of Universe

© The Authors 2024

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. Subscribe to A&A to support open access publication.

1 Introduction

The structure-formation process in the Universe is hierarchical, with smaller structures collapsing and merging to form larger ones. Galaxy clusters, the most massive virialized objects in the Universe, lie at the apex of this hierarchy. They serve as valuable cosmological probes, offering insights into the growth of density perturbations and the geometry of the Universe (see, for instance, Allen et al. 2011; Kravtsov & Borgani 2012, for reviews).

The cosmological exploitation of cluster surveys is primarily based on number count analysis. This method involves comparing the observed number of clusters in a survey, as a function of redshift and of a given observable quantity, to the theoretical prediction of the halo mass function (HMF) within a cosmological model, thus enabling the derivation of constraints on cosmological parameters. Numerous studies have been conducted in this area (e.g., Borgani et al. 2001; Holder et al. 2001; Rozo et al. 2010; Hasselfield et al. 2013; Planck Collaboration XX 2014; Bocquet et al. 2015; Mantz et al. 2015; Planck Collaboration XXIV 2016; Bocquet et al. 2019; Abbott et al. 2020; Costanzi et al. 2021; Lesci et al. 2022a).

Complementing cluster count analysis is cluster clustering statistics, which examines the spatial distribution of clusters in the Universe (Mana et al. 2013; Castro et al. 2016; Baxter et al. 2016; To et al. 2021; Lesci et al. 2022b; Sunayama et al. 2023; Romanello et al. 2024; Fumagalli et al. 2024). The halo bias (HB) is a fundamental concept in this analysis since it reflects the ratio between the number overdensity of the cluster and of the matter distribution. This relationship is expected to bring cosmological information through the mass- and redshift-dependence of the HB and to be linear on large scales (i.e., ≳ 100 Mpc) to guarantee the scale-independence of the HB.

The Euclid mission (Laureijs et al. 2011; Euclid Collaboration 2022, 2024c) is projected to provide significant advancements to cluster cosmology. Sartoris et al. (2016) have forecasted that the combined cluster count and clustering analysis by the Euclid mission will provide constraints on the amplitude of the matter power spectrum and the mass density parameters independent and competitive with other cosmological probes, underlining the potential of galaxy clusters as cosmological probes for ongoing and future missions.

At the heart of cluster cosmology are the theoretical models for the HMF and HB. Simplified models based on linear perturbation theory and spherical collapse have provided invaluable insights into the potential of cluster counts and clustering as cosmological probes (see, e.g., Press & Schechter 1974; Bond et al. 1991). However, given the complexity and strongly non-linear nature of cluster formation dynamics, a refinement of these models to the precision level required by available and forthcoming surveys has to rely on cosmological simulations as the primary method to capture such complexity. Several studies have been dedicated to calibrating semi-analytical models for the HMF and HB, aiming to align these models’ predictions with the results from extensive sets of simulations (see, for instance, Sheth & Tormen 1999; Sheth et al. 2001; Jenkins et al. 2001; Warren et al. 2006; Tinker et al. 2008, 2010; Bhattacharya et al. 2011; Watson et al. 2013; Despali et al. 2016; Comparat et al. 2017; Euclid Collaboration 2023). These simulations not only accurately describe the gravitational interactions that predominantly drive structure formation, they but also attempt to account for the effects of baryonic matter.

The influence of baryons, albeit a minor component in the Universe’s overall composition, plays a significant role in the formation of structures, particularly in the context of these simulations (Cui et al. 2014; Velliscig et al. 2014; Bocquet et al. 2016; Castro et al. 2020). Given the sensitivity of baryon evolution to the inclusion and modeling of astrophysical processes occurring at scales much smaller than those resolved in simulations, the modeling of baryonic feedback in hydrodynamical simulations remains a subject of active debate. At the scale of galaxy clusters, for instance, baryonic feedback is known to reorganize the mass density profile of halos without disrupting the structures, thereby altering the mass enclosed within a given radius compared to predictions from collisionless N-body simulations. Owing to the substantially greater computational demands of hydrodynamical simulations, it has become standard practice to derive the HMF from gravitational N -body simulations, with subsequent post-processing to account for baryonic effects (see, e.g. Schneider & Teyssier 2015; Aricò et al. 2021). In this paper, we concentrate on the initial step of calibrating the HB using collisionless simulations. This approach is intended to be a foundational phase, with the baryonic effects being integrated later, and we employed a methodology akin to that used for the HMF (see, Castro et al. 2020; Euclid Collaboration 2024a). This strategy underscores our commitment to systematically exploring the cosmological parameter space, acknowledging the importance of baryonic effects while methodically building toward their inclusion in our analysis.

Systematic errors in the calibration of the HMF and HB can significantly impact the final cosmological constraints. Studies such as those by Salvati et al. (2020), Artis et al. (2021), and Euclid Collaboration (2023) have highlighted how inaccuracies in theoretical models can propagate biases into cosmological parameter inferences. In response to these challenges, Euclid Collaboration (2023) presented a new, rigorously studied calibration of the HMF based on a suitably designed set of N -body simulations, offering the required accuracy to analyze Euclid cluster count data.

Semi-analytical modeling typically starts with a simplified physical model, such as the peak-background split (PBS; Mo & White 1996), which is then extended and refined by adding more degrees of freedom. These additional degrees of freedom are subsequently fitted to simulations. Conceptually, PBS links the HB to the HMF by decomposing the density field into high- and low-frequency modes. The high-frequency modes that cross the collapsing barrier describe the collapse of structures. In contrast, the low-frequency modes modulate the density field fluctuations, thereby enhancing the number of peaks that cross the collapse threshold, therefore linking the clustering of collapsed objects with the local density field. Despite its qualitative consistency with simulations, the quantitative precision of PBS must be enhanced, especially in the context of the Euclid mission’s requirements.

In this paper, we address the challenge of enhancing the accuracy of HB predictions to the level required to fully exploit the cosmological potential of the two-point clustering statistics from the Euclid photometric cluster survey. Our approach involves calibrating a semi-analytical model to quantify the discrepancies between PBS predictions and simulation results. This calibration aims to refine HB predictions, improving the reliability of cosmological parameter estimation derived from cluster counts and clustering.

This paper is organized as follows. We revisit the theoretical aspects used in this paper in Sect. 2. In Sect. 3, we describe the methodology used in our analysis. We present the HB model and its calibration in Sect. 4 along with an assessment of our model’s impact in a forecast Euclid cluster cosmology analysis. Final remarks are made in Sect. 5. The implementation of our model is publicly available at https://github.com/TiagoBsCastro/CCToolkit and presented in Sect. 5.

2 Theory

2.1 The halo mass function

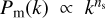

The differential HMF is given by

(1)

(1)

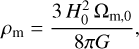

where n is the comoving number density of halos with mass in the range [M, M + dM], v is the peak height, and the function vf (v) is known as the multiplicity function. The term pm is the comoving cosmic mean matter density,

(2)

(2)

where H0 and Ωm,0 are the current value of the Hubble parameter and the matter density parameter, and G is the gravitational constant. The peak height is defined as v = δc/σ(M, z), where δc is the critical density for spherical collapse (Peebles 2020) and σ2(M, z) is the filtered mass variance at redshift z so that it measures how rare a halo is. The mass variance is expressed in terms of the linear matter power spectrum Pm(k, z) as

(3)

(3)

where R(M) = [3 M / (4 πρm)1/3 is the Lagrangian radius of a sphere containing the mass M, and W(kR) is the Fourier transform of a top-hat filter of radius R.

The multiplicity function is considered universal if its cosmological dependence is solely through the peak height. However, numerous studies based on N-body simulations have challenged this assumption. These analyses reveal that, while the initial approximation of HMF universality is generally valid, systematic deviations from this universality become evident at late times in the universe’s evolution. This deviation has been demonstrated in various independent investigations, each indicating a nuanced understanding of the HMF’s behavior (e.g., Crocce et al. 2010; Courtin et al. 2011; Watson et al. 2013; Diemer 2020; Ondaro-Mallea et al. 2021; Euclid Collaboration 2023).

The non-universality of the HMF is affected by both the halo definition and the residual dependence of Ac on cosmology. Various studies have shown this dependence, including Watson et al. (2013), Despali et al. (2016), Diemer (2020), and Ondaro- Mallea et al. (2021) for the dependence on the halo definition, and Courtin et al. (2011) for the cosmology dependence of δc. In our study, we define halos as spherical overdensities (SO) with an average enclosed mean density equal to Δvir(z) times the background density, where Δvir(z) is the non-linear density contrast of virialized structures as predicted by spherical collapse (Eke et al. 1996; Bryan & Norman 1998). The multiplicity function for halo masses computed at the virial radius has been shown to preserve universality better than other commonly assumed definition of halo radii (Despali et al. 2016; Diemer 2020; Ondaro-Mallea et al. 2021). As for δc, we use the fitting formula introduced by Kitayama & Suto (1996) that ignores the effect of massive neutrinos; however, for the adopted values for total neutrino masses in this work, the fitting formula is still percent level accurate (LoVerde 2014).

In this paper, we use the HMF presented in Euclid Collaboration (2023):

(4)

(4)

where the parameters {a, p, q} depend on background evolution and power spectrum shape as

(5)

(5)

(6)

(6)

(7)

(7)

and where Ωm is the fractional density of matter in the Universe as a function of redshift, encompassing both baryonic and dark matter contributions

(8)

(8)

(9)

(9)

Lastly, the normalization parameter A is not a free parameter but a function of the other parameters:

![$A(p,q) = {\left\{ {{{{2^{ - 1/2 - p + q/2}}} \over {\sqrt \pi }}\left[ {{2^p}\Gamma \left( {{q \over 2}} \right) + \Gamma \left( { - p + {q \over 2}} \right)} \right]} \right\}^{ - 1}},$](/articles/aa/full_html/2024/11/aa51230-24/aa51230-24-eq10.png) (10)

(10)

where Γ denotes the Gamma function. The adopted values for the HMF parameters are presented in Table 4 of Euclid Collaboration (2023) and depend on the halo-finder used. In this work, we mostly use the ROCKSTAR calibration. The SUBFIND calibration is also used in Sect. 4.1.2 to assess the impact of the halo-finder in our model.

2.2 The linear halo bias

The overdensity of halos of mass M at the position r at redshift z,

(11)

(11)

is expressed in terms of the corresponding local number halo number density, n(r, M, z), and of the cosmic mean number density of such halos,  . In linear theory, it is related to the matter density contrast δm(r, z) as

. In linear theory, it is related to the matter density contrast δm(r, z) as

(12)

(12)

where b(M, z) is the linear halo bias and ϵ is a stochastic term that in the following we assume to be associated with shot-noise.

It follows from Eq. (12) that the halo-halo, Ph , and halomatter power spectrum, Phm , are written as a function of the linear matter power spectrum, Pm , for sufficiently large scales as

(13)

(13)

(14)

(14)

where PSN represents the shot-noise component. Under the assumption that halos offer a discrete Poisson sample of the underlying continuous matter density field, PSN denotes a shotnoise component commonly assumed to be equivalent to the Poisson term, PSN = 1/N, where N is the mean number density of tracers. On the other hand, halos are known to correspond with high-density peaks of the underlying matter distribution. Therefore, they are expected not to provide a purely Poissonian sampling of this continuous density field. In fact, Casas-Miranda et al. (2002) and Hamaus et al. (2010) showed that positive and negative corrections to Poisson shot-noise are expected for low- and high-mass halos. In this paper, we parameterize PSN as

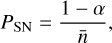

(15)

(15)

where α, a fitting parameter that we calibrate through simulations, controls the deviation from the assumption of Poisson noise.

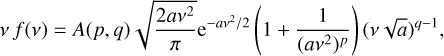

Assuming the universality of the HMF, Mo & White (1996) derived the HB b(M, z) directly from the HMF by following the PBS framework. The PBS prediction for the HB as a function of the peak height ν reads

(16)

(16)

Although the PBS provides an estimate of the bias that presents the correct qualitative behavior, Tinker et al. (2010) claims a relatively poor performance of the PBS in reproducing results from N -body simulations, with an accuracy of about 10–20%.

Given the correct qualitative behavior of the PBS prescription, in this paper, we aim to improve the prediction of the bias by calibrating a model for the bias as a function of bPBS – that is, we assume Eq. (16) to be valid, with the HMF (4) – and model its difference with respect to the simulations.

Cosmological parameters of the PICCOLO set of simulations.

3 Methodology

3.1 Simulations

3.1.1 N-body simulations

Table 1 presents the adopted values for the matter density parameter and baryonic density parameter at redshift 0 (Ωm,0 and Ωb,0), the dimensionless Hubble parameter h, the spectral index of the primordial power spectrum ns, and the amplitude of matter density fluctuations on scales of 8h–1 Mpc σ8 for the N-body simulations used in this work. We extended the set of PICCOLO simulations introduced and used by Euclid Collaboration (2023) to calibrate the HMF model. We maintain the same technical configurations as the original PICCOLO simulations and refer to the above-mentioned HMF paper for further details while summarizing the main aspects. The set comprises 69 cosmological boxes, each with a comoving size of 2000 h–1 Mpc, and 4 × 12803 dark matter particles. The simulations were conducted using OpenGADGET3, with initial conditions generated by monofonIC(Michaux et al. 2021), based on third-order Lagrangian Perturbation Theory (3LPT) at a redshift of z = 24. The adopted gravitational softening is equivalent to one-fortieth of the mean inter-particle distance.

The original PICCOLO set of simulations included nine different choices for cosmological parameters, which were randomly chosen from the 95% confidence level hyper-volume of the joint SPT and DES cluster abundance constraints (Costanzi et al. 2021). Those represent the cosmologies C0 to C8 in Table 1. To further stress our modeling and guarantee its robustness, we also add the cosmologies C9 and C10, which sample the (Ωm,0, σ8) plane in the direction orthogonal to the degeneracy direction of the constraints from Costanzi et al. (2021), and in significant tension with such constraints. For each cosmology, two white-noise realizations were created to generate initial conditions. For each noise realization, a pair was generated by fixing the amplitudes of the Fourier modes of the density fluctuation field and pairing the phases (Angulo & Pontzen 2016), except for the reference C0 model, which had 20 realizations.

We further added three simulations with Einstein–de Sitter cosmology (EdS; i.e., Ωm = 1 and ΩΛ = 0) with powerlaw initial matter power spectrum  with ns ∈ {–1.5, –2.0, –2.5}. Those simulations, which have the same box size and the same number of particles as the PICCOLO set, are only instrumental for the modeling and are not used for the calibration, as they are far from the regime used to calibrate the model of Euclid Collaboration (2023).

with ns ∈ {–1.5, –2.0, –2.5}. Those simulations, which have the same box size and the same number of particles as the PICCOLO set, are only instrumental for the modeling and are not used for the calibration, as they are far from the regime used to calibrate the model of Euclid Collaboration (2023).

Lastly, we carried out three pairs of simulations with massive neutrinos, again using the same box size as the PICCOLO set. Each pair has a total neutrino mass Σmν ∈ {0.15, 0.30, 0.60} eV. The simulation set-up for the neutrino simulations is the same used for the OpenGADGET3 simulations extensively validated in Adamek et al. (2023). The baseline cosmological parameters is the C0 set, with Ων,0 subtracted from Ωm,0. The simulations have the same primordial amplitude As, resulting in a lower σ8 for increasing neutrino mass (see Table 1).

The initial conditions (ICs) for the neutrino simulations were generated using the FastDF (Elbers 2022) implementation to monofonIC (Michaux et al. 2021)1. The forked repository with the FastDF integration can be found here2. We employed the same number of neutrino particles as the number of grid resolution elements used for the cold dark matter particles. The total neutrino mass specified is attributed to a single massive neutrino species.

3.1.2 Approximate methods: PINOCCHIO

In this paper, we also analyzed 200 (100 pairs with each pair having fixed amplitudes and paired phases) halo catalogs simulated with the approximate LPT-based method implemented in the PINOCCHIO code (Monaco et al. 2002, 2013; Munari et al. 2017). All these simulations have been carried out under the assumption of the C0 cosmological parameters. The rationale for this extra set of simulated catalogs is to model the impact of fixing and pairing the Fourier mode amplitudes in the ICs on the cluster clustering.

3.2 Halo finders

Euclid Collaboration (2023) showed that the halo-finder adopted for the analysis of the N -body simulations can significantly alter the HMF. To understand if the halo-finder also impacts the HB, we selected two algorithms to extract halo catalogs: ROCKSTAR (Behroozi et al. 2013a)3 and SUBFIND (Springel et al. 2001; Dolag et al. 2009; Springel et al. 2021). Although all these algorithms rely on the SO method to define halo boundaries, they differ in the method used to identify the center from which the spheres are grown and the criteria to classify between structures and sub-structures.

ROCKSTAR divides the simulation volume into 3D friend-of- friends (FOF; see, for instance, Davis et al. 1985) groups and runs a recursive 6D FOF algorithm on each group to create a hierarchy of FOF subgroups. Halo centers are determined by averaging the positions of particles in the innermost subgroup. To improve consistency, we apply the CONSISTENT algorithm, which dynamically tracks halo progenitors, to the extracted ROCKSTAR catalogs as demonstrated in Behroozi et al. (2013b). SUBFIND also determines halo centers using a parallel implementation of the 3D FOF algorithm but directly assigns it to the particle with the lowest gravitational potential.

Among the halo-finders studied by Euclid Collaboration (2023), ROCKSTAR and SUBFIND are good representatives of the heterogeneity of possible results as they are close to the extremes, with SUBFIND suppressing the abundance of objects more massive than 1013 M⊙ h–1 by roughly 10%. See Knebe et al. (2011) for a more detailed comparison between the halo-finding algorithms.

3.3 Measuring the halo bias

To measure the HB, we bin the halo distribution in log10(Mvir/M⊙ h–1) with equispaced width intervals of 0.1 dex at each redshift. If the number of halos inside a bin was less than 10 000, we merged it with its neighbor to avoid having bins where the power-spectrum measurements were primarily dominated by shot noise. We measured the cross-spectrum Phm between the halos in each mass bin and the matter distribution traced by particles. The bias is then obtained as the ratio between this cross-spectrum and the matter power spectrum Pm(k). The matter density field was computed at the initial conditions and rescaled according to the linear growth factor for the simulations without massive neutrinos. For the simulations with massive neutrinos, the matter density field was built from the particle data from the same snapshot from which the halo catalog was extracted to consider the scale-dependent growth factor. We used the PYLIANS4 Python libraries to construct the density field and compute power spectra on a 10243 piecewise cubic spline mesh grid. PYLIANS averages the power spectra in k-space shells with the width given by the fundamental mode of the box, kf ≡ 2π/L. Following Castro et al. (2020), we only considered modes with k values smaller than 0.05 h Mpc–1 to measure the HB, to ensure the validity of the linear approximation. The maximum k used for the measurements corresponds to the 16th harmonic of the box and is much smaller than the Nyquist frequency of the grid used to compute the power spectrum.

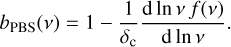

To calculate the bias for each mass bin, we used the ratio of the halo-matter cross-spectrum and the matter power spectrum

(17)

(17)

where i and j are the mass bin and the k-shell indexes, respectively.

3.4 Halo bias calibration

We used a Bayesian approach with uninformative uniform priors on all parameters to fit our model for the linear HB parameters to simulation results. The best fits were obtained using the Dual Annealing method to find the posterior maximum as implemented by Virtanen et al. (2020), and covariance between parameters was estimated using PyMC (Salvatier et al. 2016)5. The No-U-Turn sampler (NUTS) (Hoffman et al. 2014) was automatically assigned internally by PyMC to sample the likelihood.

We assumed a Gaussian likelihood for the bias, since the power spectrum estimation for a Gaussian field realization follows a χ2-distribution when averaged over a shell. Since the number of modes Nk inside the shell increases rapidly with k, this distribution approaches a Gaussian distribution by the central limit theorem. However, the number of modes is small for the first bins, and deviation from the Gaussian approximation is evident. To avoid this issue, we re-binned the measurement of the first 3 k-bins by merging them, ensuring that the bin with the fewest modes still contains 117 modes to recover the Gaussian approximation’s validity.

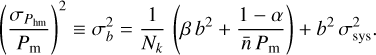

We note that differently than Castro et al. (2020), we used ICs with fixed amplitudes. Therefore, the distribution of the simulated bias is not approximately a ratio of two Gaussian distributions but approximately Gaussian itself since the denominator of Eq. (17) is not a random variable. The variance of the shell-average halo-matter cross-spectrum on simulations with random Gaussian initial conditions is given by

(18)

(18)

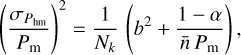

where we assumed that the shot-noise contribution to the halo power spectrum follows Eq. (15) and a linear HB b. However, Zhang et al. (2022) showed that the predictions for random Gaussian initial conditions overestimate the variance observed for biased tracers on simulations with fixed amplitudes. Therefore, we modified Eq. (18) as follows:

(19)

(19)

Here, β and σsys are parameters we marginalize over, which control the variance suppression and the relative error due to the limited accuracy of the HMF used as the backbone for the PBS prescription. We note that, based on the halo model (see, for instance Cooray & Sheth 2002), one should expect a value for β close to zero as in the limit where all halos are considered, the shot-noise term on the right-hand side of Eq. (19) tends to zero so that one should recover the matter power spectrum that by construction has zero variance. Furthermore, the HMF presented in Euclid Collaboration (2023) was shown to have percent-level accuracy; thus, σsys is expected to assume similar values during the calibration, presuming the PBS framework is valid. However, it is crucial to note that should σsys significantly deviate from zero, such an occurrence could indicate a potential violation or limitation within the PBS framework, underscoring the necessity for careful interpretation of these parameters.

We obtained the total log-likelihood by summing up all mass bins, modes, redshifts, and simulations. Following Euclid Collaboration (2023), we use the redshifts z ∊{2.00, 1.25, 0.90, 0.52, 0.29, 0.14, 0.0}, translating to a timespacing of about 1.7 Gyr. This spacing is larger than the characteristic dynamical time of galaxy clusters and effectively suppresses the correlation between the results of different snapshots.

Similarly, we assume that the correlations between different mass bins and modes are negligible. This assumption is justified by linear theory, which posits that different modes evolve independently in the linear regime, thus minimizing their mutual influence. In our analysis, we have three fitting parameters: α, β, and σsys , in addition to the parameters of the bias model that are subject to calibration (to be discussed in Sect. 4.1.3). This approach allows for a comprehensive calibration of the bias model, taking into account the shot-noise correction α, the suppression of variance β, and the systematic uncertainties σsys inherent to our method.

3.5 Forecasting Euclid’s cluster counts and cluster clustering observations

To understand the impact of the HB calibration on cosmological constraints, it is important to realistically forecast the cosmological information to be extracted from the Euclid photometric cluster survey. For this purpose, we first quantify the impact of the HB on cluster counts and cluster clustering analyses. More precisely, the HB enters the modeling of the cluster counts covariance, which we compute analytically following the model of Hu & Kravtsov (2003), as validated in Fumagalli et al. (2021). Regarding the cluster clustering, the HB enters both in the computation of the mean value (power spectrum or two-point correlation function), and in the associated covariance matrix; in this work, we test the effect on the real-space two-point correlation function and its covariance, following the model presented and validated in Euclid Collaboration (2024b).

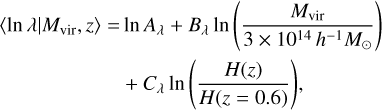

After assessing the impact on the two statistics, we forecast how the accuracy of the HB calibration propagates on the cosmological constraints obtained by cluster counts and cluster clustering experiments. We generate synthetic cluster abundance data as described in Section 2.5 of Euclid Collaboration (2023), assuming the HMF calibrated and the HB of this work as benchmarks. Through a likelihood analysis, we constrain the cosmological parameters Ωm,0 and σ8, and the mass-observable relation (MOR) parameters Aλ, Bλ, Cλ, Dλ (see Section 2.5 of Euclid Collaboration 2024a), assuming flat priors for all the parameters. The MOR parameters describe the optical richness λ distribution as a function of the halo mass according to

(20)

(20)

where H(z) denotes the Hubble parameter at redshift z. The range for richness λ is considered to be between 20 and 2000, with the variation in logarithmic richness for a given virial mass and redshift expressed as a log-normal scatter:

(21)

(21)

The reference values for the parameters are Aλ = 37.8, Bλ = 1.16, Cλ = 0.91, and Dλ = 0.15. These values have been obtained refitting the parameters presented in Saro et al. (2015) to the virial mass definition, with the assumption that halo profiles follow an NFW profile with a mass-concentration relationship as outlined in Diemer & Joyce (2019). The parameter values adopted in this work are consistent with the model presented by Castignani & Benoist (2016) to assign cluster membership probabilities to galaxies from photometric surveys.

We perform the analysis on the synthetic catalogs, comparing them with the predictions made by using our bias and the one of Tinker et al. (2010), and compare the resulting posteriors with two estimators: we quantify the broadening/tightening of the posterior’s amplitude by computing the difference of the figure of merit (∆FOM; see Huterer & Turner 2001; Albrecht et al. 2006) in the Ωm,0 − σ8 plane, and the shift of the posterior’s position by computing the posterior agreement (Bocquet et al. 2019), which determines whether the difference between two posterior distributions is consistent with zero.

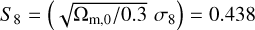

|

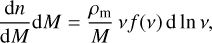

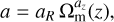

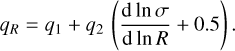

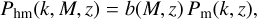

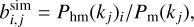

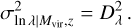

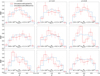

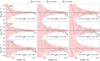

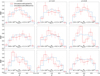

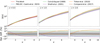

Fig. 1 Constraints on the parameters in Eq. (19) fitted to the unbiased standard deviation of the 200 PINOCCHIO mocks with C0 cosmology. We fitted α and β considering k ≤ 0.05 h Mpc−1, assuming a Gaussian likelihood with error bar estimated from the measurements for 0.05 ≤ k/h Mpc−1 ≤ 0.2 and assuming it to be constant in k and equivalent to the unbiased standard deviation. |

4 Results

4.1 Calibration of the halo bias

4.1.1 Biased tracers statistics on fixed and paired simulations

Before modeling and calibrating the HB to the simulations, we investigate the impact of the variance suppression technique on the halo matter cross-spectrum.

In Fig.1, we present the constraints on the parameters in Eq. (19) fitted to the unbiased standard deviation of the 200 PINOCCHIO mocks with C0 cosmology. We fixed σsys to zero, as this exercise does not involve modeling errors on the bias. The parameters α and β were fitted using only modes with k ≤ 0.05 h Mpc−1, under the assumption of a Gaussian likelihood. We estimated the error bars from the measurements within the range 0.05 ≤ k/h Mpc−1 ≤ 0.2, treating it as constant and equivalent to the unbiased standard deviation. This approach prevents the estimation of the expectation of the mean and the error from using the same data. Figure 1 reveals a positive correlation between the parameters, with both assuming positive values. As expected, the posterior for the β parameter peaks close to zero, validating the effectiveness of the fixed amplitudes technique in reducing the variance of biased tracer statistics. Notably, the small value of α found in our analysis suggests that the shot noise is well modeled as Poissonian to within 1–3%.

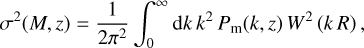

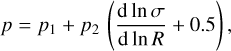

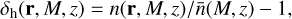

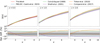

In Fig. 2, we present the relative difference between Eq. (19) computed with the best-fit values of α and β, and the unbiased standard deviation of the measurements, for different mass bins and redshift values. We present the results for three values z ∊ 0.0, 1.0, 2.0 spanning the redshift range of interest, while for the masses, we present the first, the intermediate, and the last occupied bin for each redshift. We observe that the residuals of the fit always oscillate around zero, with no statistically significant mass, redshift, or k dependence.

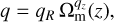

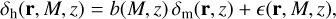

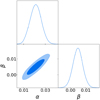

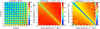

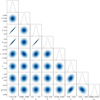

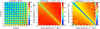

In Fig. 3, we present the Pearson correlation coefficient ρ between the measurements of the halo-matter cross-power spectrum on a given simulation and its paired realization. The correlation coefficient between two random variables X and Y is defined as

(22)

(22)

where σX and σY are the standard deviation of the random variables X and Y. The cross-power spectrum was measured for k ≤ 0.05 h Mpc−1, for different ranges of halo masses (as reported in each panel) and redshift values (different columns). We also present the correlation coefficient between simulations that assumes uncorrelated white-noise realizations for comparison. We note that paired simulations do not show a statistically significant difference in their correlation with respect to simulations that assume uncorrelated noise realizations. The same conclusion is obtained by running a p-value test on all mass and redshift bins. This result justifies the assumption that different simulations are, in fact, independent, even if they have the same amplitudes and paired phases. This conclusion aligns with the claims of Villaescusa-Navarro et al. (2018) that variance suppression techniques are unlikely to affect the halo abundance distribution. As the shot-noise term in Eq. (19) dominates over the other terms for our sample selection, one could anticipate the independence of the bias results from fixed and paired simulations due to the independence of abundance fluctuations and modes paring.

Lastly, we use the PINOCCHIO catalogs to assess the impact of neglecting the correlation between different mass bins and Fourier modes on the calibration likelihood presented in Sect. 3.4. We measured the bias on the PINOCCHIO catalogs by applying the same mass and modes binning we used in our calibration and measured the correlation matrix between different simulations. In line with the results presented in Euclid Collaboration (2024b) for the two-point correlation function, we explicitly verified in our analysis that the off-diagonal terms are sub-dominant and of the order of 10%, validating our calibration likelihood.

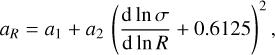

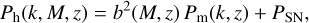

4.1.2 Impact of the halo finder on the peak-background split performance

In Fig. 4, the impact of the halo finder on the PBS is examined through the bias ratio measured in halo catalogs generated from the same simulation using either ROCKSTAR or SUBFIND, alongside the corresponding PBS prescription. For the ROCKSTAR catalogs, the standard error of the mean is further illustrated using an additional 19 realizations, with the assumed cosmology being C0. The analysis spans different redshifts within the z ∊ [0, 2] range. It is observed that the PBS tends to underestimate the simulation-derived bias by approximately 10% at higher redshifts, though it shows improved accuracy at z = 0. Given the minimal impact of the choice of halo finder on PBS’s overall accuracy, subsequent results focus exclusively on the ROCKSTAR halo catalogs. Despite PBS’s tendency to underpredict the HB compared to simulations, it is noteworthy that the deviation remains consistently within 5–15% across all explored values of v and redshifts. Our future efforts will aim to refine the PBS model by addressing these discrepancies, with the objective of achieving a simulation-calibrated HB model that is precise to within a few percent.

|

Fig. 2 Relative difference between Eq. (19) best fit and the unbiased standard deviation of the PINOCCHIO measurements. Different columns are for different redshifts, and the corresponding mass bins are shown in each panel. The vertical dotted line demarcates two distinct sets of measurements: Those to the left of the line were utilized as data points in the parameter fitting process, while the scatter of the points to the right was analyzed to estimate the variance. The gray regions highlight areas within a 5% deviation from the expected values. |

4.1.3 Modeling the halo bias

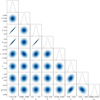

In Fig. 5, we present the mean of the ratio of the measured bias with respect to the PBS prescription for different simulations. In the left panel, we use all the CO runs and show the ratio of the bias as a function of v/(1 + z) for redshifts 0, 0.29, and 1.25. The factor (1 + z) is only used to scale the results from different red-shifts of the C0 model to the same range. In the middle panel, we show the mean ratio as a function of v for the three EdS cosmologies. Lastly, in the right panel, we present the mean ratio as a function of the background evolution Ωm(z) for the C0, C9, and C10 cosmologies.

The left panel of Fig. 5 illustrates that the performance of PBS is influenced by the cosmological background evolution, encapsulated by Ωm(z), yet appears unaffected by variations in v. This contrasts with the observations in the central panel, where PBS performance varies with both v and changes in the power spectrum’s shape. This sensitivity to v is attributed to the limitations of the HMF calibration by Euclid Collaboration (2023) when applied to an EdS cosmology that is far from its calibration regime, introducing artificial dependency.

However, it is important to note that, although these extrapolations to EdS scenarios are beyond the initial calibration range of the HMF model, the model’s accuracy is not disproportionately affected across different values of ns. Indeed, in Euclid Collaboration (2023), it has been demonstrated that the HMF model retains a consistent level of precision across various EdS cosmologies characterized by scale-free linear power spectra. Therefore, the dependence on the shape of the power spectrum is more likely related to the varying degree of accuracy of the PBS bias model as the shape of the power spectrum changes.

We interpret the dependence of the PBS performance as a function of the shape of the power spectrum as follows. The extrapolation of the results on the central panel of Fig. 5 indicates that the PBS performance on EdS cosmologies with a steeper power spectrum (ns < −2.5) degrades with decreasing ns. Within the PBS framework, the mass variance σ(RL) smoothed on the scale of the Lagrangian patch RL is assumed to be dominated by the contribution of scales RLSS ≫ RL For a power-law power spectrum, it is

(23)

(23)

Therefore, the ratio σ (RL) / σ(RLSS) tends to unity as ns tends to −3. On the one hand, this explains why ns = −2.5 presents better performance than the other cases as one of the PBS assumptions is better suited. On the other hand, for ns ≡ −3, perturbations on all scales reach the collapse at the same time, and it is no longer possible to distinguish between peaks and a large-scale modulation of a background perturbation, thus breaking PBS’s fundamental assumption.

The right panel of Fig. 5 shows that the residuals with respect to the PBS prediction increase linearly with the value of the density parameter Ωm(z). While the slope of this linear dependence is similar for the three cosmologies, the normalization is a decreasing function of the clustering amplitude S8. In fact, C9 is the simulation with the lowest  while C10 has the highest clustering amplitude S8 = 1.07. The C1 to C8 simulations are not shown in this panel for better readability, but they cluster around C0 as they have similar S8 values.

while C10 has the highest clustering amplitude S8 = 1.07. The C1 to C8 simulations are not shown in this panel for better readability, but they cluster around C0 as they have similar S8 values.

The better performance of the PBS in cosmologies with more clustering suggests that the difference between this model and the simulation results is related to the connection between Lagrangian patches in the initial density field and the collapsed structures identified by the halo-finder. Collapsed structures stand out more clearly from the non-linear density field in more evolved and clustered cosmologies. For less clustered models, large halos are still forming and overlapping due to ongoing mergers. This makes it more challenging to identify and link them to their corresponding Lagrangian patches clearly. Not surprisingly, in the EdS cosmologies, the PBS best performance is for ns = −2.5, where the evolution of the power spectrum is the steepest.

The above line of reasoning suggests then that an SO algorithm could not be accurate in providing a one-to-one mapping between Lagrangian patches, destined to form virialized halos according to spherical collapse, and for which the PBS method predicts the bias, and halos identified in the non-linearly evolved density field. In this vein, since both ROCKSTAR and SUBFIND are based on an SO algorithm, it is not surprising that they predict similar deviations from PBS (see Fig. 4).

On the other hand, we expect that collapsed structures have had more time to relax in cosmological models characterized by a higher value of S8. As a consequence, they are more likely to be spherical. Again, this is in line with the better performance of the PBS on evolved cosmologies, as shown in the right panel of Fig. 5. Although suggestive, this interpretation of the deviations of PBS predictions would require a dedicated analysis to track their origin in detail, which goes beyond the scope of the analysis presented here.

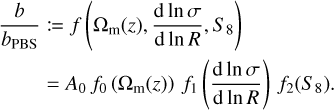

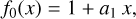

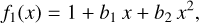

From the results shown in Fig. 5, it emerges that deviations from the PBS should depend on cosmic evolution, parameterized by Ωm(z), on the slope of the linear power spectrum, and on the clustering amplitude S86. To capture such dependencies, we adopted the following description of the correction to the PBS prediction for the linear HB:

(24)

(24)

In the above expression, we assumed the following functional forms for the three above dependencies:

(25)

(25)

(26)

(26)

(27)

(27)

The parameters A0, a1, b1, b2, and c1 are calibrated in the next section through a detailed comparison with simulations. A balance between simplicity and empirical accuracy drives the parameterization chosen for these contributions. Specifically, we opted for a linear relationship for Ωm(z) and S8 while modeling the shape of the power spectrum using a quadratic function. In order to assess the potential parameter redundancy in using an extra parameter for the shape of the power spectrum, we performed Watanabe-Akaike Information Criterion (WAIC) (Watanabe 2010) and Pareto Smoothed Importance Sampling Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (PSIS-LOO) (Vehtari et al. 2017) analyses comparing the model with b2 free to vary with respect to b2 fixed to 0. Both analyses confirmed that the fewer degrees of freedom adopted by the surrogate model do not compensate for the decrease in the model’s predictability.

Lastly, we report that we do not observe any significant correlation between the model prediction residual and other cosmological parameters assumed in the simulations. Thus, we conclude that the three fi components in Eq. (24) used in our analysis are sufficient to achieve our goal.

|

Fig. 3 Correlation coefficient ρ between the measurements of the halo-matter power spectrum, Phm(k), in different simulations for k ≤ 0.05 h Mpc−1 as a function of halo mass bin and redshift. The red histograms show the distribution of the correlation coefficient between a simulation and its paired realization, while blue histograms are for the correlation coefficient between simulations with uncorrelated white-noise realizations. |

|

Fig. 4 Relative difference between the bias measured in halo catalogs and the bias predicted by the PBS model of Eq. (16) at different red-shifts in the range z ∊ [0, 2], Results refer to simulations carried out for the C0 cosmology. In each panel, blue and red lines refer to the results obtained for the halo catalogs based on the application of ROCKSTAR and SUBFIND, respectively. For the ROCKSTAR catalogs, we also show the standard error of the mean using other 19 realizations of the same cosmology. |

4.2 Calibration of the halo bias correction

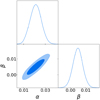

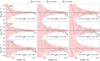

In Fig. 6, we present the marginalized two-dimensional and unidimensional constraints on the model parameters presented in Eqs. (24) to (27). The best-fit and 95% limits are reported in Table 2. We calibrate our model using the subset of 60 PICCOLO simulations covering the cosmological parameters from C0 to C10.

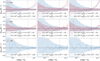

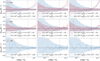

In Fig. 7, we present the ratio between the mean of the observations on the 20 C0 simulations with respect to our model predictions. Different rows correspond to different redshifts, while each panel corresponds to a different mass bin. The presented mass bins were selected as before to span from the least massive to the most massive occupied bin in that redshift. The shaded region in red corresponds to the error on the mean, assuming that each measurement follows Eq. (19). The shaded regions in gray correspond to 2% and 4% regions. As can be seen, our model’s prediction presents a performance below 2% for different masses and redshift regimes when not primarily dominated by the sample variance, as it happens, for instance, for k ≲ 10−2 h Mpc−1. This accuracy holds over the k range up to which the onset of non-linearity occurs and the approximation of scale-independent bias breaks down, that is, k ≳ 0.05 h Mpc−1 (marked by a vertical line).

We note that at large k values, non-linearity effects cause the bias measured from the simulations to take a scale dependence in exceeding the model prediction. As expected, this effect is smaller at higher redshift, consistent with the effect of non-linearity shifting to larger k values.

Similarly to Fig. 7, in Fig. 8, we present the ratio between the mean of the observations on the C9 and C10 simulations with respect to our model predictions. C9 and C10 are the simulations with lowest and highest S8, respectively. Even for such extreme scenarios, our model performs well, thus confirming that our linear bias model, with the previously described calibration, can reproduce results from simulations with an accuracy of a few percent for ΛCDM cosmologies.

|

Fig. 5 Mean of the ratio of the bias measured in simulations with respect to the PBS prescription. Left: ratio of the bias as a function of v/(1 + z) for different z, labeled by Ωm(z), for all the CO runs. Center, mean ratio as a function of v for the three EdS cosmologies of pure power-law shapes of the linear power spectrum at z = 0. We report the value of the three spectral indexes in the inset. Right: mean ratio as a function of the background evolution Ωm(z) for the C0, C9, and C10 cosmologies with varying S8. |

|

Fig. 6 Marginalized 68% and 95% confidence level contours on the model parameters presented in Eqs. (24) to (27). We calibrated our model using the subset of PICCOLO simulations C0–C10. (See Table 2 for the best fit and confidence levels.) |

|

Fig. 7 Ratio between the mean of the observations on the 20 C0 simulations with respect to our model predictions. Different rows correspond to different redshifts, while each panel corresponds to a different mass bin. The shaded region in red corresponds to the error on the mean, assuming that each measurement follows Eq. (19). The shaded regions in gray correspond to 2% and 4% regions. |

4.3 Cosmologies with massive neutrinos

We present our model’s performance when considering simulations with massive neutrinos in Fig. 9. This allowed us to assess the performance of our HB calibration for this minimal extension of ΛCDM. In this case, the simulation’s bias has been computed by comparing it to the linear power spectrum of the corresponding cosmological model, which includes only the contributions from cold dark matter and baryons. For consistency, the same choice of considering only CDM and baryon contribution is also made for the computation of the HMF entering in our model for the HB (see, for instance, Castorina et al. 2014; Costanzi et al. 2013). From Fig. 9, it is evident that our model also precisely describes the bias in Λ(v)CDM models, despite the fact that such models were not used during the HB calibration.

We note that, unlike for the pure ACDM models, in this case, the measured bias underpredicts the model bias at large k. We also note that the dependence of this effect on redshift, if any, goes in the direction of being larger at higher z. Also, there is some hint for it to be slightly smaller for smaller values of mv and therefore of Ωv. These effects align with the expectation that such deviations are not dominated by non-linear evolution but rather by the effect of neutrino-free streaming (Castorina et al. 2014).

|

Fig. 8 Similar to Fig. 7 but for the C9 and C10 cosmological parameters. Among the PICCOLO set, C9 and C10 correspond to the cosmologies with the lowest and the highest S8, respectively. |

|

Fig. 9 Similar to Fig. 7 but for simulations with massive neutrinos. For better plot readability, we only show the uncertainties (red shaded regions) for the simulation with total neutrino masses equal to 0.15 eV. |

|

Fig. 10 Comparison between the HB predicted by our model with predictions from other models presented in the literature: Cole & Kaiser (1989). Sheth et al. (2001), Tinker et al. (2010), and Comparat et al. (2017). We present both our benchmark model as well as the PBS predictions based on the HMF model of Euclid Collaboration (2023) used as a baseline of our model. Different columns correspond to different redshifts. The relative difference with respect to our benchmark model is presented in the panels in the second row. We adopted a composite scale for the residual plot to show the dynamic range of differences between the models: The scale is linear for values between [−10, 10] % and symmetric log outside. For reference, we show the zero line in black. The predictions of the models from the literature have been computed using the COLOSSUS toolkit (Diemer 2018). |

4.4 Comparison with previous models

In Fig. 10, we compare our model prediction with other models in the literature: Cole & Kaiser (1989), Sheth et al. (2001), Tinker et al. (2010), and Comparat et al. (2017). We present both our benchmark model as well as the PBS predictions based on the HMF model of Euclid Collaboration (2023), which we use as a baseline of our model. Different columns correspond to different redshifts. The relative difference to our benchmark model is presented in the panels in the second row. The predictions of the external models have been computed using the COLOSSUS toolkit (Diemer 2018)7.

To ensure a fair comparison, we adopted the Planck-like CO cosmology, where the compared models have their peak performance among the PICCOLO cosmologies. All compared models have degraded performance as we move from this benchmark cosmology while we have shown the robustness of our model in Figs. 7, 8, and 9. That is due to the models assuming either the universality of the bias relation or a redshift-only dependence, while our method explicitly models the cosmology dependence of this relation. As such, comparisons between these models should be interpreted cautiously, as the underlying cosmology influences the exact figures.

As for the comparison with the PBS prediction based on the HMF calibration by Euclid Collaboration (2023), the results shown here confirm those shown in Fig. 5: the PBS-based predictions underestimate our simulations-based calibration by about 5–10%, almost independently of v. The models of Cole & Kaiser (1989) and Sheth et al. (2001) over- and under-estimate the bias by ~10%, respectively. Their relatively poor performance is not surprising. The prediction by Cole & Kaiser (1989) corresponds to the PBS prediction when using the HMF from Press & Schechter (1974). As the Press & Schechter (1974) HMF only qualitatively explains the abundance of halos, it is expected that the bias from the PBS will not perform much better. On the other hand, the Sheth et al. (2001) model was calibrated on simulations. However, such simulations had a resolution that allowed those authors to cover a dynamic range significantly narrower than that accessible to our simulations. The prediction by Cole & Kaiser (1989) differs from ours by an amount almost independent of y and redshift. On the other hand, the HB by Sheth et al. (2001) differs from ours in a v- and z-dependent way.

Notably, the model of Tinker et al. (2010) is only superior to the abovementioned models for low peak-height. The differences with respect to our model grow with redshift and peak-height. This could be due to the heterogeneity of the simulations used to calibrate the model of Tinker et al. (2010) and the possible limitation of the model itself to capture the cosmological dependence of the HB. In this paper, we calibrate to a set of simulations that have been run with the same code and setup. On the other hand, Tinker et al. (2010) based their analysis on a collection of simulations carried out with different codes and configurations in terms of resolution and box sizes. Also, their model assumes a redshift dependency for the evolution, while from Fig. 6 we note that a parametrization of this evolution through Ωm(z) is more universal.

Lastly, the model by Comparat et al. (2017) shows a good agreement with our model. The most significant differences are at low-redshift where the model of Comparat et al. (2017) predicts a bias that is smaller than ours by about 5%. This difference reduces to a sub-percent at high redshift. The agreement is unsurprising as the model of Comparat et al. (2017) was also calibrated on ROCKSTAR catalogs.

|

Fig. 11 Percentage residuals of cluster counts (left panel) and cluster clustering covariance matrices (central and right panels), computed with the bias from Tinker et al. (2010) in comparison to the one calculated using the bias calibrated in this study (Eq. (24)). We show the full covariance matrix for number counts in mass and redshift bins. For the two-point correlation function of galaxy clusters, we show two blocks of the full covariance (low and high redshift bins) as a function of the radial separation. |

4.5 Impact on cluster cosmology analysis

In this section, we forecast the impact of the HB calibration on cosmological analysis of cluster counts and cluster clustering from Euclid. We present the results for the bias model of Tinker et al. (2010) and the model calibrated in this study. The rationale for assuming Tinker et al. (2010) is to use a widely used model in cluster cosmology representative of the difference in the bias models presented in Fig. 10. Nonetheless, we do not expect the results to change significantly if we assumed the model of Comparat et al. (2017) that presents a better concordance with our model at high redshift but worse at low redshift. Therefore, the overall impact on cosmological constraints will compensate partially as the clustering cosmological signal for Euclid peaks at lower redshifts.

As described in Sect. 3.5, we assess the effect of the HB calibration in a more realistic scenario, performing a likelihood analysis of both the individual analysis of number counts and cluster clustering statistics and the combination of these probes. In all scenarios, the observable-mass relation (Eq. (20)) is calibrated by combining the probes with weak lensing (WL) mass estimates, assuming a constant error of 1%. The mass calibration is the primary source of systematic uncertainty in cluster cosmology studies, and a 1% calibration represents the goal for stage IV surveys. Therefore, the chosen setting offers a forecast of the utmost cosmological bias resulting from inaccurate modeling of the HB. Lastly, we assume three independent Gaussian likelihoods (Fumagalli et al. 2024) for number counts, clustering, and WL masses.