| Issue |

A&A

Volume 691, November 2024

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A240 | |

| Number of page(s) | 14 | |

| Section | Catalogs and data | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202451409 | |

| Published online | 15 November 2024 | |

ASTRODEEP-JWST: NIRCam-HST multi-band photometry and redshifts for half a million sources in six extragalactic deep fields

1

INAF – Osservatorio Astronomico di Roma,

Via Frascati 33,

00078

Monteporzio Catone,

Rome,

Italy

2

Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of California, Los Angeles,

430 Portola Plaza,

Los Angeles,

CA

90095,

USA

3

Department of Astronomy, The University of Texas at Austin,

Austin,

TX,

USA

4

SUPA (Scottish Universities Physics Alliance), Institute for Astronomy, University of Edinburgh, Royal Observatory,

Edinburgh

EH9 3HJ,

UK

5

NSF’s National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory,

950 N. Cherry Ave.,

Tucson,

AZ

85719,

USA

6

School of Physics, University of Melbourne,

Parkville 3010, VIC,

Australia

7

ARC Centre of Excellence for All Sky Astrophysics in 3 Dimensions (ASTRO 3D),

Australia

8

Space Science Data Center, Italian Space Agency,

via del Politecnico,

00133

Roma,

Italy

9

Department of Physics,

196A Auditorium Road, Unit 3046, University of Connecticut,

Storrs,

CT

06269,

USA

10

Space Telescope Science Institute,

Baltimore,

MD,

USA

11

University of Massachusetts,

710 N. Pleasant St, LGRB-520,

Amherst,

MA

01003,

USA

12

Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing, Swinburne University of Technology,

PO Box 218,

Hawthorn,

VIC

3122,

Australia

13

INAF – Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova,

Vicolo Osservatorio 5,

35122

Padova,

Italy

14

Institute of Physics, Lab for Galaxy Evolution, EPFL, Observatoire de Sauverny,

Chemin Pegasi 51,

1290

Versoix,

Switzerland

15

Laboratory for Multiwavelength Astrophysics, School of Physics and Astronomy, Rochester Institute of Technology,

84 Lomb Memorial Drive,

Rochester,

NY

14623,

USA

16

Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian,

60 Garden Street,

Cambridge,

MA

02138,

USA

17

Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Kansas,

Lawrence,

KS

66045,

USA

18

Department of Physics and Astronomy, Colby College,

Waterville,

ME

04901,

USA

19

Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, UCO/Lick Observatory, University of California,

Santa Cruz,

CA

95064,

USA

20

Department of Physics & Astronomy, Tufts University,

MA

02155,

USA

21

Dipartimento di Fisica, Università di Roma Sapienza, Città Universitaria di Roma – Sapienza,

Piazzale Aldo Moro, 2,

00185

Roma,

Italy

22

INAF – Osservatorio Astronomico di Trieste,

Via Tiepolo 11,

34131

Trieste,

Italy

23

Department of Physics and Astronomy, Texas A&M University,

College Station,

TX

77843-4242

USA

24

George P. and Cynthia Woods Mitchell Institute for Fundamental Physics and Astronomy, Texas A&M University,

College Station,

TX

77843-4242,

USA

25

Centro de Astrobiología (CAB), CSIC-INTA,

Ctra. de Ajalvir km 4, Torrejón de Ardoz,

28850

Madrid,

Spain

26

ESA/AURA Space Telescope Science Institute,

USA

27

Astrophysics Science Division, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center,

8800 Greenbelt Road,

Greenbelt,

MD

20771,

USA

28

Center for Research and Exploration in Space Science and Technology II, Department of Physics, Catholic University of America,

620 Michigan Ave N.E.,

Washington,

DC

20064,

USA

29

Department of Astronomy, University of Geneva,

Chemin Pegasi 51,

1290

Versoix,

Switzerland

30

Center for Computational Astrophysics, Flatiron Institute,

162 5th Avenue,

New York,

NY

10010,

USA

31

School of Astronomy and Space Science, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences (UCAS),

Beijing

100049,

China

32

National Astronomical Observatories, Chinese Academy of Sciences,

Beijing

100101,

China

33

Institute for Frontiers in Astronomy and Astrophysics, Beijing Normal University,

Beijing

102206,

China

34

Astronomy Centre, University of Sussex,

Falmer,

Brighton

BN1 9QH,

UK

35

Institute of Space Sciences and Astronomy, University of Malta,

Msida

MSD

2080,

Malta

36

Kapteyn Astronomical Institute, University of Groningen,

PO Box 800,

9700 AV

Groningen,

The Netherlands

37

SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research,

Postbus 800,

9700 AV

Groningen,

The Netherlands

★ Corresponding author; emiliano.merlin@inaf.it

Received:

7

July

2024

Accepted:

30

September

2024

Aims. We present a set of photometric catalogues primarily aimed at providing the community with a comprehensive database for the study of galaxy populations in the high-redshift Universe. The set gathers data from eight JWST NIRCam observational programs, targeting the Abell 2744 (GLASS-JWST, UNCOVER, DDT2756, and GO3990), EGS (CEERS), COSMOS and UDS (PRIMER), and the GOODS North and South (JADES and NGDEEP) deep fields. This dataset covers a total area of ≃0.2 sq. degrees.

Methods. We obtained photometric estimates by means of well-established techniques, including tailored improvements designed to enhance the performance on the specific dataset. We also included new measurements from HST archival data, spanning 16 bands from 0.44 to 4.44 µm.

Results. A grand total of ~530 thousand sources were detected on stacks of NIRCam 3.56 and 4.44 µm mosaics. We assessed the photometric accuracy by comparing fluxes and colours against archival catalogues. We also provide photometric redshift estimates, statistically validated against a large set of robust spectroscopic data.

Conclusions. The catalogues are publicly available on the ASTRODEEP website.

Key words: methods: data analysis / catalogs / galaxies: high-redshift / galaxies: photometry

© The Authors 2024

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. Subscribe to A&A to support open access publication.

1 Introduction

Two years since its first light, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST; Gardner et al. 2006, 2023) has provided a vast store of cutting-edge, quality data to many fields of astrophysical research. In particular, the study of the high-redshift Universe has benefitted from the joint effort of researchers designing tailored observational programmes and exploiting their outcomes, with an outburst of activity within the very first weeks after the arrival of the first data (see e.g. Adamo et al. 2024, for a review).

The unmatched depth and resolution of JWST infrared imaging and spectroscopy has enabled a wealth of analysis at intermediate and high redshifts that were beyond the reach of previous instruments. Examples include the measurement of optical rest-frame morphologies (e.g. Ferreira et al. 2022, 2023; Jacobs et al. 2023; Treu et al. 2023; Kartaltepe et al. 2023), stellar masses (e.g. Santini et al. 2023; Weibel et al. 2024; Wang et al. 2024a), and star-formation histories (e.g. Dressler et al. 2023; Looser et al. 2023; Ciesla et al. 2024; Conselice et al. 2024) of galaxies up to z ≃ 10, to the abundance and properties of red and optically dark sources (e.g. Glazebrook et al. 2023; Kirkpatrick et al. 2023; Pérez-González et al. 2023a; Rodighiero et al. 2024) as well as quiescent galaxies (e.g. Carnall et al. 2023; Nanayakkara et al. 2024; Wright et al. 2024; Ward et al. 2024) up to z ~ 6, the properties of compact red sources (Pérez-González et al. 2024; Williams et al. 2024; Kokorev et al. 2024), and the identification of extreme emission line galaxies in the epoch of reionization (e.g. Davis et al. 2023). In particular, JWST has challenged our view of the early epochs of the cosmos. A number of exciting discoveries on the first phases of galaxy formation and evolution have resulted in more questions than answers, as we have yet to frame and understand our observations within a fully consistent theoretical framework. The most consolidated result so far is the evidence of a striking overabundance of bright galaxies at z ≳ 9– 10 compared to most predictions (e.g. Castellano et al. 2022, 2023; Naidu et al. 2022; Finkelstein et al. 2023, 2024; McLeod et al. 2024; Pérez-González et al. 2023b; Carniani et al. 2024). These distant sources have been mostly identified by means of colour selections or spectral energy distribution (SED) fitting, and the result is still a matter of debate, with numerous possible explanations proposed (e.g. Ferrara et al. 2023; Dekel et al. 2023; Mason et al. 2023; Trinca et al. 2024; Padmanabhan & Loeb 2023; Yung et al. 2024; Harvey et al. 2024). While spectroscopic follow-up is crucial to understand the physical processes at play – and, indeed, they currently seem to confirm the early results (e.g. Arrabal Haro et al. 2023a; Harikane et al. 2024; Castellano et al. 2024), photometric data still constitute the primary way to collect statistically significant samples, beyond providing targets for spectroscopy.

In this paper, we present our analysis of eight deep-sky NIR-Cam observational programmes: CEERS, DDT2756, GLASS-JWST, GO3990, JADES, NGDEEP, PRIMER, and UNCOVER. We used these data to create a new set of photometric catalogues, mainly finalised to provide a consistent database for the study of the early phases of galaxy evolution in the high-redshift Universe (z ≥ 3). The programmes target six of the most well-known and studied areas of the sky, which have already been observed with HST and ground-based facilities (in particular, the CANDELS and Frontier Fields campaigns; see Grogin et al. 2011; Koekemoer et al. 2011; Lotz et al. 2017), and have been subject of many ground-breaking studies in the past decades: (i) the GLASS-JWST, UNCOVER, DDT2756 and GO3990 programmes cover the Abell 2744 cluster of galaxies, also known as Pandora’s cluster, and its surrounding area. For simplicity, we will refer to this extended region as ABELL2744; (ii) the CEERS survey overlaps with the Extended Groth Strip (EGS) field (Davis et al. 2007); (iii-iv) the PRIMER programme covers two areas, one overlapping with the UKIDSS Ultra-deep Survey field (UDS, Lawrence et al. 2007) and the other with the COSMOS field (Nayyeri et al. 2017); (vi) JADES and NGDEEP overlap with the GOODS-North and ECDFS/GOODS-South regions (Giacconi et al. 2002; Giavalisco et al. 2004). The total area observed by these programmes is ≃0.2 sq. degrees. While some catalogues for these observations are already available (e.g. Paris et al. 2023; Rieke et al. 2023; Weaver et al. 2024), the aim of this new dataset is to provide a large, self-consistent database mainly aimed at the study of the high-redshift Universe. Therefore, we mostly focused our attention on the detection of faint sources when choosing detection parameters. Unsurprisingly, this choice can lead to some degree of tension when comparing our results to other catalogues (see Sect. 4).

The new catalogues are obtained with well-tested algorithms and techniques, largely building upon previous releases of our group (Merlin et al. 2022; Paris et al. 2023, respectively M22 and P23 hereafter), but with substantial improvements, which we describe in Sect. 3. Up-to-date data and calibration files have been used whenever available (detailed information is provided). We also estimated photometric redshifts, which we obtained using the SED-fitting software packages ZPHOT, first described in Fontana et al. (2000), and EAZY (Brammer et al. 2008), for which we used three different sets of templates. Predictably, comparing the results from these four runs we find that they typically are in good agreement for high signal-to-noise (S/N) sources, while faint objects are less well constrained, often resulting in divergent fits. Finally, we validated our results comparing them to the literature. We find substantial agreement with other photometric catalogues and good statistics when checking the photo-z results against the spectroscopic data.

The paper is organised as follows. In Sect. 2, we describe the dataset. In Sect. 3 we summarise the adopted techniques, referencing previous publications when useful and highlighting the differences with previous works. In Sect. 4, we discuss the validation of our new catalogues against published data, considering direct comparisons of colours. In Sect. 5, we discuss the photometric redshifts. In Sect. 6, we make some final remarks and conclusions. The catalogue format is described in Appendix A (available on Zenodo; see Data availability). We use AB magnitudes (Oke & Gunn 1983) and we assume an ACDM cosmology (H0 = 70 km/s/Mpc, Ωm = 0.27, and ΩΛ = 0.73).

Details of the pipeline versions and calibration files used for each dataset.

2 Dataset

In this section. we summarise the properties of the composite dataset we used to obtain the photometric catalogues presented in this work. For all the fields but ABELL2744, we collected the NIRCam 30mas mosaics created by the teams of each programme. In most cases, ancillary HST images were also made available; when needed, we re-projected them on the same grid of the NIRCam mosaics, and checked for astrometric consistency (see Sect. 3.1). All of the images were also scaled to µJy units, so that AB magnitudes can be obtained from the flux measurements applying a constant zero-point (ZP) of 23.9. In the following, we detail the process case by case; because of the composite nature of the dataset, which comprises images reduced by different teams at different times, the specific parameters of the reduction processes were unavoidably non-uniform. The different calibration files and pipeline versions used in this study are summarised in Table 11.

In order to create a formally homogeneous set of catalogues, we selected a fixed set of pass-band filters, thereby also facilitating the photo-z estimates for which tailored libraries of models are required. The chosen bands are: HST ACS F435W, F606W, F775W and F814W; HST WFC3 F105W, F125W, F140W and F160W; and NIRCam F090W, F115W, F150W, F200W, F277W, F356W, F410M, and F444W. The main features of these pass-bands are summarised in Table 2. We point out that not all of the bands are available in all fields; we provide the relevant details in the following subsections. The areas given for each field are indicative, as many pass-bands have different sky coverage; the values refer to the F444W band area.

2.1 ABELL2744

Imaging data from four programmes were combined in a single set of mosaics: GLASS-JWST (ERS 1324, P.I. Treu; no F410M, Treu et al. 2022), UNCOVER (GO 2561, P.I. Labbé; no F090W, Bezanson et al. 2022), DDT 2756 (P.I. Chen; no F090W and F410M), and GO 3990 (P.I. Morishita; no F410M). The resulting combined field of view (FoV) is centred on the galaxy cluster, and covers an area of ≃45.7 sq. arcmin. With respect to P23, new data have been received and added: the GO 3990 images in the UNCOVER region and a new set of observations of the GLASS-JWST region acquired in July 2023 to correct the original 2022 images that were affected by a wing-tilt event in the short-wavelength bands (SW hereafter, i.e. F090W, F115W, F150W, and F200W; the redder bands are denoted long-wavelength, LW hereafter). The reduction has been re-done from scratch with new calibration files, following the procedure described in P23. The raw uncal images have been retrieved from the MAST archive2, and combined to cal images by applying the first two stages of the official JWST calibration pipeline (calwebb_detector1 and calwebb_image2) with the latest calibration and reference files available to date (see Table 1). We then applied our modified version of the official pipeline using a number of custom procedures developed by our team to correct for defects: ‘snowballs’, non-linear pixels, 1/f-noise, ‘wisps’ and ‘claws’. We aligned the calibrated images to Gaia-DR3 astrom-etry, and finally we combined them into mosaics and ancillary weight and error (root mean square, RMS) maps, (see P23 Sect. 2.2.1 for details). We then complemented the NIRCam dataset with archival HST mosaics, reduced, and publicly released by G. Brammer3. A global background subtraction on all the mosaics was performed with SEXTRACTOR (Bertin & Arnouts 1996).

We point out that this field is different from all the others because it is centred on a galaxy cluster. Working on this same region for the Frontier Fields campaign, Merlin et al. (2016b) developed a sophisticated technique to accurately subtract bright foreground galaxies and intra-cluster light from all the analysed bands. However, such a technique is complex and time-consuming, so we postpone its application to future work. As mentioned in P23, the global background and 1/f-noise subtraction techniques effectively remove most of the intra-cluster light from the images. Furthermore, we provide photometric estimates including local background subtraction (see Sect. 3.4), which effectively removes residual intra-cluster light while also mitigating spurious effects created by the global processing. Nevertheless, we warn users that the sources close to the centre of the cluster should be treated with caution, since their photometry might be affected by the residual light of the cluster members or by artefacts caused by the global background subtraction (see also Sect. 3.4.2). Also, potential very-high-redshift objects magnified by (but close to) the cluster centre are currently impossible to detect.

Main features of the pass-band filters included in the catalogues.

2.2 CEERS

Data from the CEERS programme (ERS 1345, P.I. Finkelstein; no F090W, Finkelstein et al. 2022) cover an area of ≃94.6 sq. arcmin. Images have been reduced by M. Bagley combining two epochs of observations (see Bagley et al. 2023). The individual pointings are available from CEERS public releases 0.5 and 0.64 and at MAST as High Level Science Products via DOI 10.17909/z7p0-8481. We have drizzled all ten individual pointings from these two releases into single mosaics for this paper. For HST we used the EGS dataset from CANDELS (Stefanon et al. 2017, no F435W and F775W data), with the addition of the F105W band from the CEERS HDR1 reduction5. A new catalogue based on a more recent, improved reduction of the NIRCam data, and obtained applying slightly different techniques, is going to be published soon by the CEERS team (Cox et al., in preparation).

2.3 JADES and NGDEEP

Mosaics from the JADES programme (GTO 1180, P.I. Eisen-stein, and GTO 1210, P.I. Luetzgendorf, Eisenstein et al. 2023), including additional data from the FRESCO programme (PID 1895, P.I. Oesch), cover an area of ≃83.0 sq. arcmin in the GOODS-North region (JADES-GN hereafter), and of ≃84.5 sq. arcmin in the GOODS-South region (JADES-GS hereafter). The images are available to the public. We used the v2.0 version for JADES-GS and the v1.0 version for JADES-GN. We complemented the NIRCam data using the Hubble Legacy Fields images (Illingworth et al. 2016).

The NGDEEP programme (P.I. Finkelstein; no F090W and F410M, Bagley et al. 2024) adds an area of ≃9.5 sq. arcmin from the outer ECDFS area, with a marginal overlap with the GOODS-South field. Since the observed FoV does not overlap with JADES-GS, we kept the two fields separated, creating two catalogues and analysing them individually. We used the same imaging data of Leung et al. (2023), which only includes the first epoch of observation. This first epoch suffered from a lack of depth due to the DEEP8 readout pattern with a small number of groups. An updated catalogue based on both significant improvements to the first epoch and including the second epoch will be published in the near future (Leung et al., in preparation).

2.4 PRIMER-COSMOS and PRIMER-UDS

Data is from the PRIMER programme (GO 1837, P.I. Dun-lop; no F775W for PRIMER-COSMOS and no F775W and F105W for PRIMER-UDS). The COSMOS FoV has an area of ≃141.8 sq. arcmin, and the UDS FoV has an area of ≃251.2 sq. arcmin. The images have been reduced by D. Magee, with ancillary HST data re-reduced from the CANDELS imaging, UVCANDELS (Wang et al. 2024b), and supplemental programme 16872 (P.I. Grogin).

|

Fig. 1 Example of the validation tests made to fix the astrometric registration of the HST bands. Shown is the displacement ∆RA and ∆DEC between the sources detected in the CEERS F125W image and those detected in the CANDELS EGS F160W image, re-aligned to the reference frame of the CEERS F150W image, before (left panel) and after (right panel) applying the correction described in Sect. 3.1. |

3 Methods

In this section, we summarise the techniques and algorithms we used to prepare the images and to extract photometric information.

3.1 Alignment and astrometry

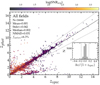

We assessed the quality of the astrometric registration by cross-matching the source coordinates ALPHAWIN_J2000 and DELTAWIN_J2000 obtained by running SEXTRACTOR on all the bands in each field before re-projecting the images to the same common grid. In most cases we found small ∆RA and ∆DEC offsets (of the order of a few mas) between the native astrometry of the JWST mosaics (which are aligned to Gaia) and the HST bands. However, since in some cases the offsets were larger and not negligible, we applied a custom algorithm to correct all of them. First, we computed the offset between the HST WFC3 F160W band and the JWST NIRCam F150W band, and re-aligned the F160W image (we applied a rigid shift to the whole image). Then we corrected the offsets of the other HST bands by cross-matching the coordinates of the sources with those extracted from the re-aligned F160W band (see Fig. 1 and Table B.1). Finally, we re-projected all the images on the same NIRCam pixel grid.

3.2 RMS scaling

Because the photometric errors were computed by means of the RMS maps (see Sect. 3.4), we checked that the latter were indeed representative of the true uncertainties of the measurement, using an improved version of the technique described in M22. In short, the RMS image of each band was subdivided into two to four complementary sub-regions of comparable exposure time, by means of an automatic algorithm applied to the weight maps. Then, in each of these sub-region, 300 artificial point sources (WebbPSF6 simulated point spread functions) were injected at random positions, excluding areas assigned to real sources by means of SEXTRACTOR segmentation maps. The dispersion of their fluxes (measured within an aperture of 0.1″ using the software A-PHOT, Merlin et al. 2019) was compared to their nominal errors to obtain a re-scaling factor for that region of the RMS map. Finally, the original map (which includes Poissonian photon noise) was then re-scaled by the median value of such factors. The typical values for SW bands are below ~1.5, while they can get as high as ~2.0 for some LW bands and fields.

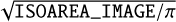

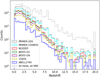

The histograms in Fig. 2 show the distribution of the limiting magnitudes (total at 5σ in apertures of 0.2″) for all the NIRCam bands, as obtained from the re-scaled RMS map pixel values by means of the formula:

(1)

(1)

where i is a pixel index, ZP is the zero-point of the image (23.9 in our case), A = π(0.5 × 0.2/ps)2 is the area of the circular aperture of 0.2″ diameter (ps is the pixel scale), and fr0.2 is the fraction of the flux of a point source enclosed in the aperture (see Table 2).

3.3 Detection

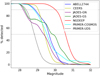

Because the catalogues have mainly been designed for the study of the high-redshift Universe, major effort was put into optimising the measurements of faint extended objects, rather than those of bright local galaxies or stars. The strategy is similar to that adopted in M22 and P23: we chose to carry out our detection in the infrared, smoothing the scientific image with a Gaussian convolution filter with full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 0.14” (close to the F356W and F444W FWHMs; see below), and applying a detection threshold corresponding to S/N~2, to pick up as many faint high-redshift sources as possible. However, there is a substantial difference with respect to previous work: rather than just using F444W as the detection band, we created a weighted stack of F356W and F444W, allowing us to single out sources that peak at 3.5 to 4 µm, and exploiting the F356W mosaics, which are often as deep as (or deeper than) the F444W ones (see Fig. 2). The resulting depths of the detection stacks are shown in Fig. 3.

We then ran SEXTRACTOR v2.8.6, in the customised version used for the CANDELS campaign. Most of the parameters were left at the default values, with the exception of those given in Table 3. We tried to use the same values for all fields, but we found that DETECT_THRESH and ANALYSIS_THRESH needed adjustment in some cases, to ensure optimal results. In particular, we set them to 0.85 for PRIMER-COSMOS, and to 0.55 for ABELL2744; these values yielded the best trade-off between purity and completeness, allowing for the detection of faint sources, while avoiding too many spurious objects from being included on the list.

The final detection catalogues contain a grand total of 531 173 sources, as reported in Table 4. In the catalogues we include a unique object identifier number, the equatorial position (right ascension and declination, in degrees), and basic morphological information. The latter includes the area of the segmented cluster of pixels and the half light radius from SEXTRACTOR, while the semi-major axis, ellipticity, and position angle of the elliptical isophote were obtained by means of A-PHOT (see Appendix A for more details).

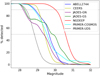

Figure 4 shows the point-source detection completeness for the six fields, determined by injecting fake PSF-shaped objects in empty regions of the F356W+F444W stack (using the detection segmentation map as a mask), running SEXTRACTOR with the same parameters used in the actual detection process, and checking the fraction of them being actually detected. The different depths of the detection images is evident, with NGDEEP being the deepest with 90% at AB≃30 and 50% at AB≃30.5 and PRIMER-UDS the shallowest, with 90% at AB≃28.5 and 50% at AB≃29. We note the complicated pattern of the JADES-GS field, which comprises deep and shallow regions (90% completeness at AB≃28.5, but 50% at AB≃30).

|

Fig. 2 Histograms of the pixel distributions of limiting magnitudes (total at 5σ in 0.2″ diameter apertures), computed as described in Sect. 3.2, for all bands and fields. |

SEXTRACTOR parameters used for the detection.

Number of detections in the six fields.

3.4 Photometry

As in our previous efforts, in our public catalogues we provide total fluxes. The main methods used for this work are the same ones adopted in M22 and P23. In short, we compute colours in fixed circular apertures on PSF-matched images; as in P23, we smoothed all bands to the F444W resolution, except for the HST WFC3 bands which, having a broader FWHM, were smoothed to the F160W resolution. Assuming no colour gradients outside the apertures, we then scale to total fluxes, multiplying the colour term by the flux within Kron (1980) elliptical apertures in the F356W+F444W stack as measured by the software A-PHOT (Merlin et al. 2019). So, the total flux in each band is given by the formula ftot,band = cap,det × fap,band, where cap,det = ftot,det / fap,det. As pointed out in M22, our A-PHOT Kron-like aperture on average tends to gather more light than the standard SEXTRACTOR MAG_AUTO (see Fig. 4 in M22), so we did not apply any further aperture correction to the total fluxes. Errors are estimated by summing in quadrature the relevant pixels from the RMS maps and applying the same formula, etot,band = Cap,det × eap,band; this choice is motivated by the fact that most scientific applications (e.g. SED-fitting or colour-selections) are essentially based on colours, so the propagation of the total flux error would overestimate the relevant uncertainty. We computed the fluxes within nine apertures (with diameters 0.2″, 0.28″, 0.33″, 0.50″, 0.66″, 0.70″, 1.32″, 2.65″, and 5.30″), and built just as many catalogues of total fluxes. The values of the apertures correspond to integer multiples of the F444W FWHM 0.165″, except for the two smallest ones (a fixed 0.1″ radius aperture and the value corresponding to the WebbPSF F444W FWHM, 0.14″) and the sixth one (corresponding to the larger aperture in the UNCOVER catalogue by Weaver et al. 2024). We point out that we did not correct the fluxes for the cluster magnification effect in the ABELL2744 field.

For each field, we provide an ‘optimal’ catalogue, in which the total flux of each source is obtained from the colours computed in a preferred aperture chosen on the basis of the object segmentation area. We used SEXTRACTOR ISOAREA_IMAGE as a proxy for it, and selected as the preferred aperture the one immediately larger than the value  (this implies that the diameter of the optimal aperture is close to the radius of the circularized detected area). The value of this preferred aperture is also reported in the catalogue.

(this implies that the diameter of the optimal aperture is close to the radius of the circularized detected area). The value of this preferred aperture is also reported in the catalogue.

|

Fig. 3 Limiting magnitudes (total at 5( in 0.2” diameter apertures) of the detection F356W+F444W stack mosaics. |

|

Fig. 4 Detection completeness: fraction of fake point sources of a given magnitude injected in the detection F356W+F444W stacks and detected with SEXTRACTOR runs performed with the parameters used in real runs. |

|

Fig. 5 PSF “über”-models for all the bands in the catalogues. See text for details. |

3.4.1 PSF models

A major difference with respect to our previous efforts is the usage of empirical PSFs, rather than models simulated using the WebbPSF application. For each band, we created empirical models stacking isolated, high-S/N stars, singled out visually after an automatic pre-selection performed using catalogues created with ad-hoc SEXTACTOR runs on each band. After trying various options, including using stars from each field to create the PSFs for that field only, we found that the best results in terms of growth curves and photometric versus spectroscopic redshifts comparison (see Sect. 5) was to create an ‘über’ model for each band, stacking all the available good stars from all fields after rotating each one by the average position angle (PA) of the observation and, finally, rotating back the obtained model to the PA of the considered field (we used the Python module numpy.rotate for this task). In cases where the mosaics are made up of stacks of images from different epochs, we created models using the stars with the most common orientation in our selection (also considering those consisting of two superposed PSFs with different orientations). These models typically sample the largest area in the field. Figure 5 shows the final PSF ‘über’ models before the final rotations for their usage in the different fields.

3.4.2 Background subtraction

A-PHOT can perform ‘on-the-fly’ local background subtraction, while measuring the fluxes. Including this feature is not necessarily the best choice in all cases, as it may yield sub-optimal estimates close to bright sources or in densely populated regions; however, it is typically reasonable to apply it. Therefore, we released both sets of catalogues with the local background subtraction option switched on and off, but we suggest using the background-subtracted catalogues as the optimal choice. We checked that the difference is not dramatic for the vast majority of the sources, but it does have an impact in some cases. Figure 6 shows the difference in measured fluxes in six bands with and without A-PHOT background subtraction, in all fields. Major differences can be seen around the bright galaxies in the ABELL2744 cluster; we note how the A-PHOT background subtraction makes the objects closest to the cluster members fainter, but those slightly farther away brighter, compensating for over-subtraction in the image processing phase. Such differences are also seen in an extended area of the PRIMER-UDS field.

3.4.3 Galactic extinction

Finally, we corrected all the total fluxes for the effects of galactic extinction, taking advantage of the calculator provided by the NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database (NED)7, which gives the average dimming in a number of bands, at any given equatorial coordinates (we provide those corresponding to the centre of the FoVs of the fields). NIRCam filters are not included in the list, so for them, we interpolated between the available bands at the closest wavelengths. We used such values to compute the extinction-corrected fluxes and included the latter for the final catalogues.

3.4.4 Number counts

Figure 7 shows the number counts of all fields in four bands using the magnitudes obtained using the total fluxes in the ‘optimal’ catalogue and after the correction for galactic extinction. Comparing it with Fig. 4, it can be seen that the counts in the F444W and F356 bands typically peak close to the 50% completeness detection magnitude, which is consistent with previous studies (see e.g. Guo et al. 2013, their Fig. 4).

|

Fig. 6 Relative difference of measured fluxes in F444W with the A-PHOT background subtraction switched on and off. |

|

Fig. 7 Number counts in four NIRCam bands (total magnitudes from the optimal catalogues, normalised to field area). The thick black line is the total of all fields. |

3.5 Point-like sources, spurious detections, and flagging

To identify and flag point-like sources and potentially spurious detections (PLS and PSD, respectively) we adopted a principal component analysis (PCA) technique, described in detail in Appendix C. In short, taking advantage of the quantities MU_MAX, MAG_AUTO, MAGERR_AUTO and FLUX_RADIUS estimated with SEXTRACTOR on the F356W+F444W detection stack, we obtained a two-dimensional projection space in which PLSs occupy an extremely well-defined and tight locus and PSDs gather in a relatively confined region. The first column of Fig. C.1 shows the resulting diagram for all the fields, with the inner subplot magnifying the region where spurious and regular sources overlap; an example for one field (PRIMER-UDS) is given in Fig. 8. The exact formulae used to isolate PLS and PSD in the diagram are given in Appendix C and Table C.1. The second and third columns of Fig. C.1 show the position of the sources in two complementary diagnostic planes, namely: the MU_MAX - MAG_AUTO plane and the FLUX_RADIUS versus S/N plane, where PLS and PSD also occupy well-defined regions. The application of the PCA approach allows for a more general identification, combining the two in a fluid way.

We then assigned a further flag to each source, based on the detection and photometric measurements. Table 5 describes the used values, the final flag being the sum of all the individual addenda. Power-of-two values multiplied by 100 were assigned on the basis of the detection measurements, as an output by the A-PHOT code, the maximum total value being 1500. Addenda below 100 indicate the number of HST and/or JWST bands missing because of the different observational coverage of the areas. We also included a special flag for the sources with all HST measurement having negative values (a few sources in a limited region of the ABELL2744 field, because of problematic background subtraction in the cluster core area). To give an example, a source flagged with the value 11016 identifies a point-like object, which is blended and saturated in the detection band, and has one JWST and six HST bands missing. Thus, a flag lower than 199 typically indicates a ‘regular’ galaxy-like source which might have missing bands and/or be contaminated in its detection total flux, but it is not blended in detection, not saturated, not close to the borders of the image, nor identified as a star or a spurious detection. Clearly, these flags are a useful diagnostic tool, but we suggest using them with caution, as they are the result of many automatic processes that cannot achieve full accuracy. A certain number of spurious detections is unavoidably destined to remain in the catalogues. To further improve the purity, we visually checked all sources with photometric red-shifts estimate above 10 (see Sect. 5) to exclude at least the most obvious errors in this important sub-space of the catalogues. In doing so, we found that most remaining cases were defects in the detection stack, either caused by missing coverage in the F356W or F444W images and/or by obvious reduction errors or noise features that had not been singled out in the diagnostic planes. The most affected fields were ABELL2744, CEERS, and PRIMER-UDS.

It is reasonable to assume that similar spurious detections could exist at photo-z< 10, although making detections in the reddest bands favours high photometric redshift estimates for these kinds of fake sources. However, since it would be impossible to go through all of the catalogues to find them, we invite users to carefully inspect any objects selected for scientific purposes.

|

Fig. 8 Example of the PCA diagram used for the identification of point-like (red points) and spurious (black points) sources. |

Flags assigned in the catalogues.

4 Photometry validation

To validate the accuracy of our catalogues, we compared our ‘optimal’ catalogues (see Sect. 3.4) to other available ones, either published or obtained via private communication with the proprietary teams. We considered both archival catalogues based on HST observations (CANDELS and ASTRODEEP releases), and recent JWST catalogues from various research groups: P23 and Weaver et al. (2024) for ABELL2744, Finkelstein et al. (2023) for CEERS, S. Finkelstein’s priv. comm. catalogue for NGDEEP, and the JADES public catalogues for the two JADES fields, v2.0 for GOODS-South and v1.0 for GOODS-North (see Rieke et al. 2023)8, which also include photometry from the JEMS programme (Williams et al. 2023).

We cross-matched the catalogues using the equatorial coordinates of the detected sources with a searching radius of 0.35″. For the comparison, we only considered sources that have S/N >5 in both catalogues and flagged <200 in this work (i.e. well-behaved galaxies, non-blended in the detection stack; see Sect. 3.5).

Since many details about the detection procedure vary significantly because of the different techniques adopted in the various works, we chose to focus on colours rather than on total fluxes, as they convey a more robust diagnostic on the accuracy of the estimated SED of the galaxies. The results are shown in Figs. D.1 to D.6. The last panel for each field shows the relative difference in the total flux in F444W for JWST catalogues and in F160W for HST catalogues, for the sake of completeness. An example for one field (ABELL2744) is given in Fig. 9.

The agreement is generally good, in particular with JWST catalogues and especially in the NIRCam bands. The larger differences are found with respect to the P23 catalogue for ABEL2744 in the HST bluer bands, most likely because of the different PSF models and the local background subtraction introduced in this work. We also noticed a systematic trend with respect to the JADES catalogues in the HST bands, with our colours typically becoming redder towards the faint end of the distribution; given the good agreement of the F444W flux band estimates, this must be due to our fluxes being fainter in the HST bands. Concerning the comparisons with the archival HST catalogues, we notice an evident declining trend at the faint end of most plots, which must be due to the deeper sensitivity of the JWST data. Faint objects are now measured with more accuracy, whereas in the old catalogue, they often happened to have spurious positive fluxes (higher than their nominal errors, thus they were not classified as upper limits) as a result of local noise fluctuations; especially in the less resolved redder bands (K s and IRAC), resulting in larger colours with respect to those measured in the high quality NIRCam images. In the cases of ABELL2744 versus the ASTRODEEP catalogue by Merlin et al. (2016a) and NGDEEP versus the CANDELS by Guo et al. (2013), there are very few matched sources, so the comparison is less significant.

We feel confident that most of the discrepancies can be explained considering the differences in the adopted processing techniques, particularly concerning the apertures used to measure the fluxes, the PSF models, the background subtraction algorithms, and the correction for galactic extinction. Similar discrepancies have been found among multi-wavelength catalogues in past efforts (see e.g. Stefanon et al. 2017). A more detailed analysis is beyond the scope of the present work.

|

Fig. 9 Example of a photometry validation plot, comparing the catalogues for the ABELL2744 field from this work and from Weaver et al. (2024). Relative errors, Δc, are given, namely, the colours measured in this work minus those in the reference catalogues), versus the second band magnitude in this work catalogue (e.g. F444W for the F356-F444W colour). The number of cross-matched sources after excluding those with S/N <5 in any of the two catalogues or flag ≥200 in this work is also given; the blue line is the median of the distribution. Similar plots for all fields are available in the appendix. |

5 Photometric redshifts

We estimated photometric redshifts on our ‘optimal’ catalogues using the software packages ZPHOT (Fontana et al. 2000) and EAzY (Brammer et al. 2008). For ZPHOT, we adopted templates from Bruzual & Charlot (2003) and we assumed exponentially declining star formation histories (SFHs), with timescales, τ, ranging from 0.1 to 15 Gyr. We included nebular emission lines according to Castellano et al. (2014) and Schaerer & de Barros (2009). We considered metallicity values of 0.02, 0.2, 1, and 2.5 times Solar and the age was allowed to vary from 10 Myr to the age of the Universe at a given redshift. Finally, we adopted a Calzetti et al. (2000) extinction law with E(B-V) in the range of 0–1.1.

For EAzY, we carried out three runs: one with the predefined set of templates eazy_v1.3 and the other two with the two sets from the ones presented by Larson et al. (2023b). We used the FSPS + Set 1 + Set 3 or ‘LyaReduced’ and FSPS Set 1 + Set 4 or ‘Lya’ combinations, as suggested by the authors9). So we end up with four redshift estimates, which we list in our final catalogues.

As a final test of our photometry, we checked the accuracy of the photometric redshift estimates by considering the sub-sample of sources having spectroscopic information from the literature. We matched these spectroscopic targets with our catalogues adopting a conservative searching radius of 0.3″. We considered the following spectroscopic samples: (i) NIRSpec: for ABELL2744, data from the programmes GLASS-JWST-ERS-1324 (Treu et al. 2022), UNCOVER-GO-2561 (Bezanson et al. 2022) and GO-3073 (Castellano et al. 2024), using the Mascia et al. (2024) and Price et al. (2024, UNCOVER DR4) data releases, plus additional ones from our own on-going data analysis (Napolitano et al. 2024); for CEERS, data from the programme CEERS-ERS-1345 (Finkelstein et al. 2023), retrieving them from the public DAWN JWST Archive10 (see details in Heintz et al. 2024); for the JADES fields, data from the programme JADES-GTO-1180 (Eisenstein et al. 2023), using the DR3 spectroscopic catalogues (D’Eugenio et al. 2024) released by the team11, and FRESCO-GO-1895 (Oesch et al. 2023; Meyer et al. 2024). Additionally, we also included the collection of spectra from various programmes analysed and listed in Roberts-Borsani et al. (2024), and more data from the DAWN JWST Archive as available at the moment of writing this paper (July 2024); (ii) CANDELSz7 (Pentericci et al. 2018b) data, for JADES-GS, NGDEEP, and PRIMER; (iii) VANDELS DR4 (Pentericci et al. 2018a; McLure et al. 2018; Garilli et al. 2021) data, for PRIMER-UDS, JADES-GS and NGDEEP; (iv) the collection of ground based spectroscopy obtained with different instruments by different projects (VIMOS, Braglia et al. 2009, and MUSE, Mahler et al. 2018; Richard et al. 2021; Bergamini et al. 2023a,b) at the VLT, AAOmega on the Anglo-Australian Telescope, Owers et al. 2011, and of the HST WFC3/IR grism through the HST GO programme GLASS (Treu et al. 2015; Schmidt et al. 2014) for the ABELL27444 field; (v) the collection compiled by the CANDELS collaboration and described in Kodra et al. (2023) for CEERS, JADES-GN PRIMER-UDS, PRIMER-COSMOS; (vi) the updated compilation of Merlin et al. (2021) for JADES-GS and NGDEEP; (vii) additional red-shifts from Cowie et al. (2004); Reddy et al. (2006); Trump et al. (2009); van der Wel et al. (2016); Inami et al. (2017); Damjanov et al. (2018); Straatman et al. (2018); Scodeggio et al. (2018); Masters et al. (2019); Wisnioski et al. (2019); Urrutia et al. (2019); Ning et al. (2020); Jones et al. (2021); Pharo et al. (2022); Bacon et al. (2023) and the redshifts collected by Grazian et al. (2006); Wuyts et al. (2008); Xue et al. (2011); (viii) the MUSE (Schmidt et al. 2021; Rosani et al. 2020), zCOSMOS (Lilly et al. 2007), DEIMOS (Hasinger et al. 2018), and VUDS (Tasca et al. 2017) catalogues for PRIMER-COSMOS. For our final comparisons, we only included robust redshift estimates on the basis of the various quality flags provided by the authors and took care to avoid repetitions. Whenever a spectroscopic target was listed in more than one survey and the inferred redshift estimates (flagged as robust) differed by more than 0.05 × (1 + zavg), where zavg is the average spectroscopic redshift, we removed the target from the sample; if the difference was lower than this value but larger than 0.1, we considered the redshift; however, we conservatively removed it from the statistics adopted to evaluate the accuracy of our photometric redshifts (see details below).

Since the templates do not include an AGN component, to correctly evaluate the accuracy of the inferred photometric red-shifts, we removed known AGN from the catalogues, regardless of their nuclear contribution to the galaxy SED. To this aim, we took advantage of the lists based on JWST data presented by Harikane et al. (2023), Goulding et al. (2023), Maiolino et al. (2024), Kocevski et al. (2023), Larson et al. (2023a), Roberts-Borsani et al. (2024), Greene et al. (2024), Barro et al. (2024), and of X-ray catalogues (Nandra et al. 2015; Xue et al. 2016; Luo et al. 2017; Kocevski et al. 2018), by flagging as AGN all sources with 2–10 keV luminosity larger than 1042 erg/s or identified as AGN by the authors, and we removed spectroscopic targets flagged as AGN from the VANDELS, zCOSMOS, DEIMOS, VUDS, and COSMOS2020 (Weaver et al. 2022) datasets.

Finally, we removed from the lists problematic sources using the flags described in Sect. 3.5. In particular, we excluded PLS and PSS, and sources that are saturated or at the boundary of the images; namely, we only kept sources with flags of <400. In addition, we removed sources lacking JWST photometry in more than three bands (i.e. having the second-to-last figure in the flag value larger than 3). Using these criteria, we were left with a total sample of 16 666 spectra.

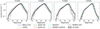

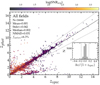

Figure 10 shows the global comparison between the spectroscopic redshifts and the median values of the photo-z estimates.

The latter were computed excluding the EAzY 'LyA' run, to avoid over-weighting the results from the runs using the templates by Larson, which are very similar in the two cases. Similar plots for each field individually are shown in Appendix E; Table E.1 reports the full statistics for the four runs made with ZPHOT and EAzY. We define dz = |zphot − zspec|/(1 + zspec), and foutliers as the percentage of objects with dz < 0.15. We then compute mean, median, standard deviation, and NMAD (defined as 1.48×median(|dz|)) of non-outliers. The four runs yield comparable statistics. The overall accuracy of the median estimates is good (NMAD 0.031, standard deviation 0.041 considering all fields together) and better than that from any individual ZPHOT or EAzY run. There is a non-negligible fraction of outliers (6.3%) comparable to (albeit larger than) the one reached in recent efforts on multi-wavelength catalogues with a larger number of bands (and more sohisticated approaches; see e.g. Merlin et al. 2021). Looking at Fig. E.1, we also note that the accuracy varies from field to field, with ABELL2744 and NGDEEP having the largest outlier fractions. This is most likely because of the effect of the cluster on photometric measurements for the former and of the low number of available spectroscopic redshifts for the latter.

We report that we also tested delayed exponentially declining SFHs with the ZPHOT code. We verified that our choice of standard exponentially declining models performs better in terms of agreement with spectroscopic redshifts.

We point out that the photometric redshift estimates are prone to substantial uncertainties for the sources at low S/N. Figure 11 exemplifies this by showing the S/N as a function of the band wavelength for a random sub-sample of 20000 sources in the PRIMER-COSMOS catalogue, colour-coding the points by the value of the standard deviation of the three photo-z estimates used to compute the median value. Clearly, the discrepancy between the estimates grows with decreasing S/N. Since we detected in the reddest bands, sources close to the detection limit in the F356W+F444W stack typically become even fainter in bluer images, thus making their characterisation very hard. This is mainly because different codes and/or templates prefer different solutions for poorly constrained photometry.

Then, as discussed in Sect. 3.5, taking the ZPHOT runs as reference (given its overall slightly better performance), we also visually inspected all of the sources with estimated redshift above 10 (which were initially 7123). By doing so, not only did we exclude a further population of spurious detections, but we identified some systematic cases where the redshift estimate was wrong due to unfortunate lack of relevant data. For example, in PRIMER-UDS some sources have been observed only with the LW NIRCam filters; thus, the missing information at wavelengths blue-ward of F277W caused an erroneous identification of the Lyman break and therefore of the redshift. We marked these and similar cases with a negative sign before the flag value in the photometric redshift catalogues. After these checks, excluding sources flagged as spurious we were left with 3068 objects with photo-z > 10. This number is certainly an over-estimation. Indeed, only 798 have a standard deviation of the estimates of the three codes lower than 0.5; again highlighting the challenging task of robustly constraining the photometric redshift for such faint, distant sources. Furthermore, some red low redshift interlopers must be present (see Arrabal Haro et al. 2023b; Harikane et al. 2024) and we deliberately only removed clearly spurious detections, not the uncertain or suspect ones. Thus, there are certainly still a number of fake sources polluting the sample. Comparing, for instance, with the estimated surface density of high-z objects by Finkelstein et al. (2024, as seen in their Fig. 8), we would expect ~20 galaxies at z > 10 with F277W<28.5 in CEERS; we found 59 in the ZPHOT sample (a value close to the expected number after correcting for completeness), but just 9 considering a restricted sample of sources having a standard deviation of the estimates from the three codes that is lower than 0.5.

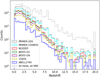

Having clarified this issue, we show in Fig. 12 the final distributions of the estimated redshifts (median estimate). The coloured stacked histograms refer to the individual fields and show the distribution of sources with detection S/N>10 and not flagged as point-like, spurious, or with a bad redshift estimate because of lacking bands, as previously explained. The dotted thin black line shows the total distribution including all S/N. The issues discussed here lead to some evidently artificial features in the global photo-z distribution, which largely disappear when considering only high S/N (e.g. S/NF444W > 10) sources. A thorough comparative analysis of the probability distribution functions from the four runs would be needed to disentangle the degeneracy for the faint objects, but this goes beyond the scope of this work. Therefore, we have restricted our study to the release of the output of the runs. For similar reasons, we also postpone the release of the physical properties for the galaxies (see e.g. Markov et al. 2023).

|

Fig. 10 Global accuracy of photometric redshifts with respect to spectroscopic samples (all fields together). zphot values are the median of the three runs described in Sect. 5; N is the number of sources; foutliers is the percentage of sources with |zphot − zspec|/(1 + zspec) > 0.15. The other statistics are computed on non-outliers, with NMAD=1.48 × median[|zphot − zspec|/(1 + zspec)]. Colour-coding is < S/N >= (S/NF444W + S/NF356W + S/NF277W + S/NF200W)|4. |

|

Fig. 11 Comparative accuracy of photometric redshift estimates as a function of the S/N of the sources. The plot shows, for a random sample of 20 000 sources from the PRIMER-COSMOS field, the S/N at the wavelengths corresponding to the photometric bands included in the catalogue, colour-coding each point with the standard deviation of the three photo-z estimates used to compute the median photo-z (see text for details). Objects with S/N <10 in the red bands (and/or S/N <1 in the blue bands) tend to have discordant photo-z estimates. See text for more details. |

|

Fig. 12 Distribution of the median photometric redshifts obtained with the runs described in Sect. 5 (raw counts per redshift bin, Δz=0.4). Stacked coloured histograms refer to individual fields, showing only sources with S/NF356W+F444W > 10 and flag <400. The dotted black line shows the cumulative distribution for all fields, including all S/N. |

6 Summary and conclusions

We present and discuss a major release of photometric catalogues, collecting data from eight JWST observational programmes on six deep extra-galactic fields. We created a new reduction of the Abell 2744 composite mosaics, gathering the GLASS-JWST, UNCOVER, DDT2756, and GO3990 programmes. For the other fields, we used the reductions provided by the teams of the other programmes. The NIRCam data are complemented with archival HST images, which we used to obtain new measurements.

The catalogues, mainly conceived for high-redshift science, include a grand-total of 531 173 objects, of which 18 563 are tagged as spurious and 2217 more have bad photometric measurements (flag≥400; see Sect. 3.5). Sources were detected with SEXTRACTOR on stacks of the F356W and F444W mosaics of each field. For all the detections, we provide positions in equatorial and pixel coordinates, basic morphological parameters, total fluxes, and corresponding uncertainties in 16 photometric bands computed by means of the software A-PHOT, a diagnostic flag, and four photometric redshift estimates obtained with ZPHOT and EAZY.

We performed validation tests on the astrometry, the photometry and the photo-z accuracy, comparing our catalogues against other releases and finding a general good agreement. We encourage the community to exploit these catalogues for any suitable scientific purpose.

Data availability

The catalogues are available for download from the ASTRODEEP website12. Updates and/or additional releases will be documented on the website. It is also possible to visualize and explore the catalogues on the Cosmological Surveys Rainbow Database13 (Pérez-González et al. 2005, 2008; Barro et al. 2019).

The appendix sections of this paper are available on Zenodo14.

The ‘optimal’ photometric catalogues (see Sect. 3.4) and the photo-z catalogues for all fields are available at the CDS via anonymous ftp to cdsarc.cds.unistra.fr (130.79.128.5) or via https://cdsarc.cds.unistra.fr/viz-bin/cat/J/A+A/691/A240.

Acknowledgements

This work is based in part on observations made with the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope. The data were obtained from the Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes at the Space Telescope Science Institute, which is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc., under NASA contract NAS 5-03127 for JWST. These observations are associated with program JWST-ERS-1342. This research is also based in part on observations made with the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope obtained from the Space Telescope Science Institute, which is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc., under NASA contract NAS 5-26555. These observations are associated with program HST-GO-17321. This research is also supported in part by the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for All Sky Astrophysics in 3 Dimensions (ASTRO 3D), through project number CE170100013. We also acknowledge support from the INAF Theory Grant 2022 “Forward modeling of theoretical models for upcoming surveys” (PI Merlin), Large Grant 2022 “Extragalactic Surveys with JWST” (PI Pentericci), Mini Grant 2022 “The evolution of passive galaxies through cosmic time” (PI Santini) and Mini Grant 2022 “Reionization and Fundamental Cosmology with High-Redshift Galaxies” (PI Castellano). B.V. is supported by the European Union - NextGenerationEU RFF M4C2 1.1 PRIN 2022 project 2022ZSL4BL INSIGHT. P.G.P.-G. acknowledges support from grant PID2022-139567NB-I00 funded by Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia, Inno-vación y Universidades MCIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033, and the European Union through FEDER Una manera de hacer Europa.

References

- Adamo, A., Atek, H., Bagley, M. B., et al. 2024, arXiv e-prints [arXiv:2405.21054] [Google Scholar]

- Arrabal Haro, P., Dickinson, M., Finkelstein, S. L., et al. 2023a, ApJ, 951, L22 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Arrabal Haro, P., Dickinson, M., Finkelstein, S. L., et al. 2023b, Nature, 622, 707 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bacon, R., Brinchmann, J., Conseil, S., et al. 2023, A&A, 670, A4 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bagley, M. B., Finkelstein, S. L., Koekemoer, A. M., et al. 2023, ApJ, 946, L12 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bagley, M. B., Pirzkal, N., Finkelstein, S. L., et al. 2024, ApJ, 965, L6 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Barro, G., Pérez-González, P. G., Cava, A., et al. 2019, ApJS, 243, 22 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Barro, G., Pérez-González, P. G., Kocevski, D. D., et al. 2024, ApJ, 963, 128 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bergamini, P., Acebron, A., Grillo, C., et al. 2023a, A&A, 670, A60 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bergamini, P., Acebron, A., Grillo, C., et al. 2023b, ApJ, 952, 84 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bertin, E., & Arnouts, S. 1996, A&AS, 117, 393 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bezanson, R., Labbe, I., Whitaker, K. E., et al. 2022, ApJ, submitted, [arXiv:2212.04026] [Google Scholar]

- Braglia, F. G., Pierini, D., Biviano, A., & Böhringer, H. 2009, A&A, 500, 947 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Brammer, G. B., van Dokkum, P. G., & Coppi, P. 2008, ApJ, 686, 1503 [Google Scholar]

- Bruzual, G., & Charlot, S. 2003, MNRAS, 344, 1000 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Calzetti, D., Armus, L., Bohlin, R. C., et al. 2000, ApJ, 533, 682 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Carnall, A. C., McLeod, D. J., McLure, R. J., et al. 2023, MNRAS, 520, 3974 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Carniani, S., Hainline, K., D’Eugenio, F., et al. 2024, Nature, 633, 318 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano, M., Sommariva, V., Fontana, A., et al. 2014, A&A, 566, A19 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano, M., Fontana, A., Treu, T., et al. 2022, ApJ, 938, L15 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano, M., Fontana, A., Treu, T., et al. 2023, ApJ, 948, L14 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Castellano, M., Napolitano, L., Fontana, A., et al. 2024, ApJ, 972, 143 [Google Scholar]

- Ciesla, L., Elbaz, D., Ilbert, O., et al. 2024, A&A, 686, A128 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Conselice, C. J., Adams, N., Harvey, T., et al. 2024, arXiv e-prints [arXiv:2407.14973] [Google Scholar]

- Cowie, L. L., Barger, A. J., Hu, E. M., Capak, P., & Songaila, A. 2004, AJ, 127, 3137 [Google Scholar]

- Damjanov, I., Zahid, H. J., Geller, M. J., Fabricant, D. G., & Hwang, H. S. 2018, ApJS, 234, 21 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, M., Guhathakurta, P., Konidaris, N. P., et al. 2007, ApJ, 660, L1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, K., Trump, J. R., Simons, R. C., et al. 2023, ApJ, Submitted, [arXiv:2312.07799] [Google Scholar]

- Dekel, A., Sarkar, K. C., Birnboim, Y., Mandelker, N., &Li, Z. 2023, MNRAS, 523, 3201 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- D’Eugenio, F., Cameron, A. J., Scholtz, J., et al. 2024, ApJS, submitted, [arXiv:2404.06531] [Google Scholar]

- Dressler, A., Vulcani, B., Treu, T., et al. 2023, ApJ, 947, L27 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstein, D. J., Willott, C., Alberts, S., et al. 2023, ApJS, submitted, [arXiv:2306.02465] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara, A., Pallottini, A., & Dayal, P. 2023, MNRAS, 522, 3986 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, L., Adams, N., Conselice, C. J., et al. 2022, ApJ, 938, L2 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, L., Conselice, C. J., Sazonova, E., et al. 2023, ApJ, 955, 94 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, S. L., Bagley, M. B., Arrabal Haro, P., et al. 2022, ApJ, 940, L55 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, S. L., Bagley, M. B., Ferguson, H. C., et al. 2023, ApJ, 946, L13 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelstein, S. L., Leung, G. C. K., Bagley, M. B., et al. 2024, ApJ, 969, L2 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana, A., D’Odorico, S., Poli, F., et al. 2000, AJ, 120, 2206 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, J. P., Mather, J. C., Clampin, M., et al. 2006, Space Sci. Rev., 123, 485 [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, J. P., Mather, J. C., Abbott, R., et al. 2023, PASP, 135, 068001 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Garilli, B., McLure, R., Pentericci, L., et al. 2021, A&A, 647, A150 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Giacconi, R., Zirm, A., Wang, J., et al. 2002, ApJS, 139, 369 [Google Scholar]

- Giavalisco, M., Ferguson, H. C., Koekemoer, A. M., et al. 2004, ApJ, 600, L93 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Glazebrook, K., Nanayakkara, T., Jacobs, C., et al. 2023, ApJ, 947, L25 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Goulding, A. D., Greene, J. E., Setton, D. J., et al. 2023, ApJ, 955, L24 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Grazian, A., Fontana, A., de Santis, C., et al. 2006, A&A, 449, 951 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Greene, J. E., Labbe, I., Goulding, A. D., et al. 2024, ApJ, 964, 39 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Grogin, N. A., Kocevski, D. D., Faber, S. M., et al. 2011, ApJS, 197, 35 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y., Ferguson, H. C., Giavalisco, M., et al. 2013, ApJS, 207, 24 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Harikane, Y., Zhang, Y., Nakajima, K., et al. 2023, ApJ, 959, 39 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Harikane, Y., Nakajima, K., Ouchi, M., et al. 2024, ApJ, 960, 56 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, T., Conselice, C., Adams, N. J., et al. 2024, ApJ, submitted [arXiv:2403.03908] [Google Scholar]

- Hasinger, G., Capak, P., Salvato, M., et al. 2018, ApJ, 858, 77 [Google Scholar]

- Heintz, K. E., Brammer, G. B., Watson, D., et al. 2024, A&A, in press, https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202450243 [Google Scholar]

- Illingworth, G., Magee, D., Bouwens, R., et al. 2016, arXiv e-prints [arXiv:1606.00841] [Google Scholar]

- Inami, H., Bacon, R., Brinchmann, J., et al. 2017, A&A, 608, A2 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, C., Glazebrook, K., Calabrò, A., et al. 2023, ApJ, 948, L13 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, L. H., Rosenthal, M. J., Barger, A. J., & Cowie, L. L. 2021, ApJ, 916, 46 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kartaltepe, J. S., Rose, C., Vanderhoof, B. N., et al. 2023, ApJ, 946, L15 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, A., Yang, G., Le Bail, A., et al. 2023, ApJ, 959, L7 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kocevski, D. D., Hasinger, G., Brightman, M., et al. 2018, ApJS, 236, 48 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kocevski, D. D., Onoue, M., Inayoshi, K., et al. 2023, ApJ, 954, L4 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kodra, D., Andrews, B. H., Newman, J. A., et al. 2023, ApJ, 942, 36 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Koekemoer, A. M., Faber, S. M., Ferguson, H. C., et al. 2011, ApJS, 197, 36 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kokorev, V., Caputi, K. I., Greene, J. E., et al. 2024, ApJ, 968, 38 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kron, R. G. 1980, ApJS, 43, 305 [Google Scholar]

- Larson, R. L., Finkelstein, S. L., Kocevski, D. D., et al. 2023a, ApJ, 953, L29 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Larson, R. L., Hutchison, T. A., Bagley, M., et al. 2023b, ApJ, 958, 141 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, A., Warren, S. J., Almaini, O., et al. 2007, MNRAS, 379, 1599 [Google Scholar]

- Leung, G. C. K., Bagley, M. B., Finkelstein, S. L., et al. 2023, ApJ, 954, L46 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lilly, S. J., Le Fèvre, O., Renzini, A., et al. 2007, ApJS, 172, 70 [Google Scholar]

- Looser, T. J., D’Eugenio, F., Maiolino, R., et al. 2023, A&A, submitted [arXiv:2306.02470] [Google Scholar]

- Lotz, J. M., Koekemoer, A., Coe, D., et al. 2017, ApJ, 837, 97 [Google Scholar]

- Luo, B., Brandt, W. N., Xue, Y. Q., et al. 2017, ApJS, 228, 2 [Google Scholar]

- Mahler, G., Richard, J., Clément, B., et al. 2018, MNRAS, 473, 663 [Google Scholar]

- Maiolino, R., Scholtz, J., Curtis-Lake, E., et al. 2024, A&A, 691, A145 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Markov, V., Gallerani, S., Pallottini, A., et al. 2023, A&A, 679, A12 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Mascia, S., Pentericci, L., Calabrò, A., et al. 2024, A&A, 685, A3 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Mason, C. A., Trenti, M., & Treu, T. 2023, MNRAS, 521, 497 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Masters, D. C., Stern, D. K., Cohen, J. G., et al. 2019, ApJ, 877, 81 [Google Scholar]

- McLeod, D. J., Donnan, C. T., McLure, R. J., et al. 2024, MNRAS, 527, 5004 [Google Scholar]

- McLure, R. J., Pentericci, L., Cimatti, A., et al. 2018, MNRAS, 479, 25 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Merlin, E., Amorín, R., Castellano, M., et al. 2016a, A&A, 590, A30 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Merlin, E., Bourne, N., Castellano, M., et al. 2016b, A&A, 595, A97 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Merlin, E., Fortuni, F., Torelli, M., et al. 2019, MNRAS, 490, 3309 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Merlin, E., Castellano, M., Santini, P., et al. 2021, A&A, 649, A22 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Merlin, E., Bonchi, A., Paris, D., et al. 2022, ApJ, 938, L14 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, R. A., Oesch, P. A., Giovinazzo, E., et al. 2024, MNRAS, submmited, [arXiv:2405.05111] [Google Scholar]

- Naidu, R. P., Oesch, P. A., van Dokkum, P., et al. 2022, ApJ, 940, L14 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nanayakkara, T., Glazebrook, K., Jacobs, C., et al. 2024, Sci. Rep., 14, 3724 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nandra, K., Laird, E. S., Aird, J. A., et al. 2015, ApJS, 220, 10 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Napolitano, L., Castellano, M., Pentericci, L., et al. 2024, A&A, submmited [arXiv:2410.10967] [Google Scholar]

- Nayyeri, H., Hemmati, S., Mobasher, B., et al. 2017, ApJS, 228, 7 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ning, Y., Jiang, L., Zheng, Z.-Y., et al. 2020, ApJ, 903, 4 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Oesch, P. A., Brammer, G., Naidu, R. P., et al. 2023, MNRAS, 525, 2864 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Oke, J. B., & Gunn, J. E. 1983, ApJ, 266, 713 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Owers, M. S., Randall, S. W., Nulsen, P. E. J., et al. 2011, ApJ, 728, 27 [Google Scholar]

- Padmanabhan, H., & Loeb, A. 2023, ApJ, 953, L4 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Paris, D., Merlin, E., Fontana, A., et al. 2023, ApJ, 952, 20 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pentericci, L., McLure, R. J., Garilli, B., et al. 2018a, A&A, 616, A174 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Pentericci, L., Vanzella, E., Castellano, M., et al. 2018b, A&A, 619, A147 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-González, P. G., Rieke, G. H., Egami, E., et al. 2005, ApJ, 630, 82 [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-González, P. G., Rieke, G. H., Villar, V., et al. 2008, ApJ, 675, 234 [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-González, P. G., Barro, G., Annunziatella, M., et al. 2023a, ApJ, 946, L16 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-González, P. G., Costantin, L., Langeroodi, D., et al. 2023b, ApJ, 951, L1 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-González, P. G., Barro, G., Rieke, G. H., et al. 2024, ApJ, 968, 4 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pharo, J., Guo, Y., Calvo, G. B., et al. 2022, ApJS, 261, 12 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Price, S. H., Bezanson, R., Labbe, I., et al. 2024, ApJ, Submitted, [arXiv:2408.03920] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, N. A., Steidel, C. C., Erb, D. K., Shapley, A. E., & Pettini, M. 2006, ApJ, 653, 1004 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Richard, J., Claeyssens, A., Lagattuta, D., et al. 2021, A&A, 646, A83 [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Rieke, M. J., Robertson, B., Tacchella, S., et al. 2023, ApJS, 269, 16 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts-Borsani, G., Treu, T., Shapley, A., et al. 2024, ApJ, submitted, [arXiv:2403.07103] [Google Scholar]

- Rodighiero, G., Enia, A., Bisigello, L., et al. 2024, A&A, 691, A69 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Rosani, G., Caminha, G. B., Caputi, K. I., & Deshmukh, S. 2020, A&A, 633, A159 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Santini, P., Fontana, A., Castellano, M., et al. 2023, ApJ, 942, L27 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schaerer, D., & de Barros, S. 2009, A&A, 502, 423 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, K. B., Treu, T., Brammer, G. B., et al. 2014, ApJ, 782, L36 [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, K. B., Kerutt, J., Wisotzki, L., et al. 2021, A&A, 654, A80 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Scodeggio, M., Guzzo, L., Garilli, B., et al. 2018, A&A, 609, A84 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanon, M., Yan, H., Mobasher, B., et al. 2017, ApJS, 229, 32 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Straatman, C. M. S., van der Wel, A., Bezanson, R., et al. 2018, ApJS, 239, 27 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tasca, L. A. M., Le Fèvre, O., Ribeiro, B., et al. 2017, A&A, 600, A110 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Treu, T., Schmidt, K. B., Brammer, G. B., et al. 2015, ApJ, 812, 114 [Google Scholar]

- Treu, T., Roberts-Borsani, G., Bradac, M., et al. 2022, ApJ, 935, 110 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Treu, T., Calabrò, A., Castellano, M., et al. 2023, ApJ, 942, L28 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Trinca, A., Schneider, R., Valiante, R., et al. 2024, MNRAS, 529, 3563 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Trump, J. R., Impey, C. D., Elvis, M., et al. 2009, ApJ, 696, 1195 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Urrutia, T., Wisotzki, L., Kerutt, J., et al. 2019, A&A, 624, A141 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- van der Wel, A., Noeske, K., Bezanson, R., et al. 2016, ApJS, 223, 29 [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B., Leja, J., de Graaff, A., et al. 2024a, ApJ, 969, L13 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X., Teplitz, H. I., Sun, L., et al. 2024b, RNAAS, 8, 26 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Ward, E., de la Vega, A., Mobasher, B., et al. 2024, ApJ, 962, 176 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, J. R., Kauffmann, O. B., Ilbert, O., et al. 2022, ApJS, 258, 11 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver, J. R., Cutler, S. E., Pan, R., et al. 2024, ApJS, 270, 7 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Weibel, A., Oesch, P. A., Barrufet, L., et al. 2024, MNRAS, 533, 1808 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C. C., Tacchella, S., Maseda, M. V., et al. 2023, ApJS, 268, 64 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, C. C., Alberts, S., Ji, Z., et al. 2024, ApJ, 968, 34 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wisnioski, E., Förster Schreiber, N. M., Fossati, M., et al. 2019, ApJ, 886, 124 [Google Scholar]

- Wright, L., Whitaker, K. E., Weaver, J. R., et al. 2024, ApJ, 964, L10 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wuyts, S., Labbé, I., Förster Schreiber, N. M., et al. 2008, ApJ, 682, 985 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Y. Q., Luo, B., Brandt, W. N., et al. 2011, ApJS, 195, 10 [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Y. Q., Luo, B., Brandt, W. N., et al. 2016, ApJS, 224, 15 [Google Scholar]

- Yung, L. Y. A., Somerville, R. S., Finkelstein, S. L., Wilkins, S. M., & Gardner, J. P. 2024, MNRAS, 527, 5929 [Google Scholar]

See the official JWST pipeline web-page for detailed information on the keywords, https://jwst-pipeline.readthedocs.io/en/latest/

All Tables

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Example of the validation tests made to fix the astrometric registration of the HST bands. Shown is the displacement ∆RA and ∆DEC between the sources detected in the CEERS F125W image and those detected in the CANDELS EGS F160W image, re-aligned to the reference frame of the CEERS F150W image, before (left panel) and after (right panel) applying the correction described in Sect. 3.1. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Histograms of the pixel distributions of limiting magnitudes (total at 5σ in 0.2″ diameter apertures), computed as described in Sect. 3.2, for all bands and fields. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 Limiting magnitudes (total at 5( in 0.2” diameter apertures) of the detection F356W+F444W stack mosaics. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4 Detection completeness: fraction of fake point sources of a given magnitude injected in the detection F356W+F444W stacks and detected with SEXTRACTOR runs performed with the parameters used in real runs. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5 PSF “über”-models for all the bands in the catalogues. See text for details. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 6 Relative difference of measured fluxes in F444W with the A-PHOT background subtraction switched on and off. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 7 Number counts in four NIRCam bands (total magnitudes from the optimal catalogues, normalised to field area). The thick black line is the total of all fields. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 8 Example of the PCA diagram used for the identification of point-like (red points) and spurious (black points) sources. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 9 Example of a photometry validation plot, comparing the catalogues for the ABELL2744 field from this work and from Weaver et al. (2024). Relative errors, Δc, are given, namely, the colours measured in this work minus those in the reference catalogues), versus the second band magnitude in this work catalogue (e.g. F444W for the F356-F444W colour). The number of cross-matched sources after excluding those with S/N <5 in any of the two catalogues or flag ≥200 in this work is also given; the blue line is the median of the distribution. Similar plots for all fields are available in the appendix. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 10 Global accuracy of photometric redshifts with respect to spectroscopic samples (all fields together). zphot values are the median of the three runs described in Sect. 5; N is the number of sources; foutliers is the percentage of sources with |zphot − zspec|/(1 + zspec) > 0.15. The other statistics are computed on non-outliers, with NMAD=1.48 × median[|zphot − zspec|/(1 + zspec)]. Colour-coding is < S/N >= (S/NF444W + S/NF356W + S/NF277W + S/NF200W)|4. |

| In the text | |

|