| Issue |

A&A

Volume 680, December 2023

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A16 | |

| Number of page(s) | 24 | |

| Section | Planets and planetary systems | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202347578 | |

| Published online | 05 December 2023 | |

Exploring the brown dwarf desert with precision radial velocities and Gaia DR3 astrometric orbits★

1

Département d’Astronomie, Université de Genève,

Chemin Pegasi 51,

1290

Versoix, Switzerland

e-mail: nicolas.unger@unige.ch

2

National Center of Competence in Research, PlanetS,

Gesellschaftsstrasse 6,

3012

Bern, Switzerland

3

RHEA Group for the European Space Agency (ESA), European Space Astronomy Centre (ESAC),

Camino Bajo del Castillo s/n,

28692

Villanueva de la Cañada, Madrid, Spain

Received:

27

July

2023

Accepted:

24

September

2023

Context. The observed scarcity of brown dwarfs in close orbits (within 10 au) around solar-type stars has posed significant questions about the origins of these substellar companions. These questions not only pertain to brown dwarfs but also impact our broader understanding of planetary formation processes. However, to resolve these formation mechanisms, accurate observational constraints are essential. Notably, most of the brown dwarfs have been discovered by radial velocity surveys, but this method introduces uncertainties due to its inability to determine the orbital inclination, leaving the true mass – and thus their true nature – unresolved. This highlights the crucial role of astrometric data, helping us distinguish between genuine brown dwarfs and stars.

Aims. This study aims to refine the mass estimates of massive companions to solar-type stars, mostly discovered through radial velocity measurements and subsequently validated using Gαìα DR3 astrometry, to gain a clearer understanding of their true mass and occurrence rates.

Methods. We selected a sample of 31 sources with substellar companion candidates validated by Gaia Data Release (DR3) and with available radial velocities. Using the Gaia DR3 solutions as prior information, we performed an MCMC fit with the available radial velocity measurements to integrate these two sources of data and thus obtain an estimate of their true mass.

Results. Combining radial velocity measurements with Gaia DR3 data led to more precise mass estimations, leading us to reclassify several systems initially labeled as brown dwarfs as low-mass stars. Out of the 32 analyzed companions, 13 have been determined to be stars, 17 are substellar, and two have inconclusive results with the current data. Importantly, using these updated masses, we reevaluated the occurrence rate of brown dwarf companions (13–80 MJup) on close orbits (<10 au) in the CORALIE sample, determining a tentative occurrence rate of 0.8−0.2+0.3%.

Key words: methods: data analysis / techniques: radial velocities / astrometry / planets and satellites: general

The CORALIE data are available at the CDS via anonymous ftp to cdsarc.cds.unistra.fr (130.79.128.5) or via https://cdsarc.cds.unistra.fr/viz-bin/cat/J/A+A/680/A16

© The Authors 2023

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. Subscribe to A&A to support open access publication.

1 Introduction

Determining the true masses of planetary and brown dwarf (BD) companions is crucial, as it contributes to the development of accurate formation and evolution models. This is specially true for companions in and around the BD desert, which refers to the observed scarcity of BD companions in close orbits around solar-type stars. The occurrence rate for these substellar companions, with masses ranging from 13 to 80 MJup, is estimated to be a mere 0.6% (Halbwachs et al. 2000; Grether & Lineweaver 2006; Sahlmann et al. 2011; Grieves et al. 2017; Kiefer et al. 2019; Barbato et al. 2023).

The occurrence rate of BDs follows a power law on both sides of the scarcity region (Grether & Lineweaver 2006). Notably, the scarcity is most prominent within the 30–55 MJup range (Ma & Ge 2014; Holl et al. 2022), with approximately half of the BD population on each side. The two populations of BDs barely overlap, suggesting that they originate from different formation mechanisms (Chabrier et al. 2014; Ma & Ge 2014; Whitworth 2018). Therefore, gaining insight into the companion population at the boundaries of the BD mass limits plays a crucial role in understanding their formation origins.

The scarcity of BD companions on short orbits around solar-like stars can be attributed to several hypotheses. One proposes that the orbital migration of BDs within evolving protoplanetary disks results in their merger with the host star (Armitage & Bonnell 2002). Another suggests ejections resulting from dynamical interactions between different companions (Whitworth 2018). Additionally, there is the hypothesis that BDs predominantly form at much larger separations, on the scale of hundreds or thousands of au (Jumper & Fisher 2013).

For gas giants, there are two main formation scenarios, core accretion (Safronov 1972; Pollack et al. 1996; Mordasini et al. 2012) and gravitational instability (Cameron 1978; Boss 1997; Kratter & Lodato 2016). Core accretion is believed to be the most prominent, but gravitational instability is still the leading formation mechanism for some gas giants (Marois et al. 2010; Teague et al. 2018). How frequently gravitational instability happens is still an active area of research (Schib et al. 2023), so better observational constraints of giant planets is of high value to better refine these formation mechanisms.

Astrometry will be of great value in obtaining better observational constraints on giant planets and BDs, as it can provide a direct measurement of the orbital inclination, which in combination with the radial velocities (RVs) gives us the true mass of a companion. The Gaia space mission (Gaia Collaboration 2016) is the instrument with the best precision in absolute astrometry to date, it is particularly sensitive to detect orbital periods in the range of 0.3 ≲ P ≲ 6 yr in the nominal 5.5-yr mission (Casertano et al. 2008), and it is expected to discover tens of thousands of giant planets and BDs (Perryman et al. 2014; Holl et al. 2022).

Prior to the full release of Gaia Data Release 3 (DR3), the astrometric solution for 1.46 billion stars had already been made public with the Early Data Release 3 (EDR3; Gaia Collaboration 2021). Using a technique called proper motion anomalies (PMa), one can compare the proper motion measurements from the HIPPARCOS mission (Perryman et al. 1997; van Leeuwen 2007) with those from Gaia EDR3 to identify differences that could indicate the presence of possible companions (Brandt 2021; Brandt et al. 2021; Kervella et al. 2022). This method has been effective in determining masses of long-period giant planets, BDs, and binary systems discovered using RVs (e.g., Kiefer et al. 2021; Venner et al. 2021; Li et al. 2021; Barbato et al. 2023).

With Gaia DR3 (Gaia Collaboration 2023a), we have access to the first astrometric orbital solutions of substellar companions (Gaia Collaboration 2023b; Holl et al. 2023). This has led to some studies that have refined the orbital parameters of giant planets using the orbital solutions from Gaia DR3 and RV data (Winn 2022; Marcussen & Albrecht 2023), which we continue and extend to BDs with the present study.

The release of Gaia Data Release 4 (DR4), which is not anticipated before the end of 2025, is expected to bring a significant advancement to the field. DR4 will be based on twice the observation time span, feature 30% more precise parallaxes compared to Gaia DR3, and enhance the precision of proper motions by a factor of 2.6 (Brown 2021). This is expected to result in the discovery of tens of thousands of giant planet and BD companions. Since the full astrometric epoch data will be released, DR4 will make it possible to combine individual astrometric and RV measurements (Delisle & Ségransan 2022). This will be analogous to the combination of HIPPARCOS intermediate astrometric data and RVs (Halbwachs et al. 2000; Zucker & Mazeh 2001; Sahlmann et al. 2011; Reffert & Quirrenbach 2011).

In Sect. 2, we provide an overview of the selected sample of stars analyzed in this study, including their stellar parameters and the RV data employed. Moving on to Sect. 3, we introduce the methodology employed to integrate the orbital solution from Gaia DR3 with the available RV data, enabling a joint fit. Subsequently, in Sect. 4, we delve into individual stars, presenting their companions and the outcomes derived from our combined fit. Finally, we examine the results in Sect. 5 and conclude the study in Sect. 6.

2 Sample selection and RV data

2.1 Sample selection

We are interested in targets with companion candidates that have a minimum mass in the substellar mass regime (<80MJup) in the RV solution, and that have a validated orbital solution in Gaia DR3. These validated solutions can be found in the gaiadr3.nss_two_body_orbit table, with the “OrbitalTar-getedSearchValidated” tag in the nss_solution_type column.

The “OrbitalTargetedSearch[Validated]” tag means that these are stars come from a targeted list of sources that contained known hosts to exoplanets, nearby bright stars, and some cooler and fainter stars (Holl et al. 2023). The “Validated” tag at the end means that the Gaia team was able to validate the orbits via external or internal means. For the planets and BDs, these validations came from RV measurements by ground based high resolution spectrographs. For the binaries, they were validated either also by ground based spectrographs or by Gaia itself with its onboard RV spectrograph (Gaia Collaboration 2023b).

We started the selection by taking stars with the Orbital-Targeted Search Validated solution type, for which the minimum mass of the companion was on the substellar mass regime (<80 MJup). The minimum mass was taken from published orbits and from our own RV fits for the few cases where no publication was available (HIP 66074, HD 40503, and HD 68638). We also removed double lined spectroscopic binaries (SB2) with the help of the Gaia DR3 solution type (HD 47391, GJ4331) or by identifying multiple peaks in the cross-correlation function (CCF) of the HARPS spectra (GJ812A). This sample is further reduced by removing sources that were not adequate for a combined analysis of RV and astrometry. The exoplanet pipeline in Gaia was only run for models with one Keplerian; this means that the solution provided by Gaia will be incomplete for sources where there are more than one confirmed companion or one companion and a long term drift that affects the model. This is the case for GJ876 (Marcy et al. 2001), HD 111232 (Mayor et al. 2004; Feng et al. 2022), HD 142 (Wittenmyer et al. 2012; Raimbault et al., in review), and HD 164604 (Arriagada et al. 2010). In Unger et al. (in prep.) we present the full RV analysis of HD 111232, as we have obtained new RV measurements that provide further insight into this planetary system.

Holl et al. (2023) mention that the initial validation did not go without pitfalls and that six known exoplanet hosts were missed from the Validated tag (see Sect. 6.3.2 of Holl et al. 2023). Four of these sources (from the “OrbitalTargetedSearch” solution type) were thus added to our sample: HR 810, HD 5433, HD 91669, and BD-004475. The remaining two sources were ignored, specifically HD 142, previously mentioned for having multiple companions, and KIC 7917485 (Murphy et al. 2016) because this companion was found through phase modulation of the stellar pulsations, and there are no RVs available. This results in a sample of 32 sources with single-companion solutions that are suitable for a combined fit of RV and the Gaia DR3 orbital solution.

2.2 Stellar parameters

The physical properties of the stars in the sample were characterized by fitting the spectral energy distribution (SED) of each star using the IDL suite EXOFASTv2 (Eastman et al. 2019) and MESA Isochrones and Stellar Tracks (MIST) method (Dotter 2016; Choi et al. 2016). This method simultaneously constrains the stellar parameters, such as effective temperature, radius, and metallicity, by incorporating information from various available archival magnitudes and evolutionary tracks. Gaussian priors were imposed on effective temperature, metallicity and parallax based on values in the Anders et al. (2019) catalog and from Gaia DR3 (Gaia Collaboration 2023a). A more detailed explanation of the full method used is described in Sect. 2 of Barbato et al. (2023). Table A.1 presents the stellar parameters for all the stars included in our study’s sample.

2.3 RV data

We used RV data from several instruments including CORAVEL (Baranne et al. 1979; Halbwachs et al. 2018), ELODIE (Baranne et al. 1996), CES (Kürster et al. 2000), CORALIE (Udry et al. 2000), HARPS (Mayor et al. 2003; Trifonov et al. 2020), HIRES (Butler et al. 2017), MIKE (Bernstein et al. 2003), TULL (Wittenmyer et al. 2009), COUDE (Cochran & Hatzes 1993), SOPHIE (Perruchot et al. 2008), HAMILTON (Vogt 1987; Fischer et al. 2014), and UCLES (Diego et al. 1990; Tinney et al. 2001). Considering that each additional instrument adds two parameters to the model (an offset and the jitter term), if there were fewer than three RV measurements available for a particular instrument, we ignored that instrument as it would not further constrain the model. Table A.2 provides comprehensive details of the RV data utilized in this study.

We also present new RV measurements from the CORALIE spectrograph for 12 stars of this work’s sample. For some of them, this represents more than ten years of additional measurements from the ones originally published at the time of discovery of their companions1.

3 Method

Our final objective is to perform a combined fit that integrates the Gaia astrometry data with the available RV measurements. However, the epoch astrometry has not been released yet, we only have the orbital solutions presently at our disposal. As such, the term “combined fit” in this context denotes the process of fitting the RVs by utilizing the Gaia DR3 solutions as prior information.

3.1 Astrometric model

The orbital parameters of an astrometric orbit are the seven elements that define the orbit’s size, shape, and orientation. They are the period (P), time of periapsis (Tp), eccentricity (e), semi-major axis of the photocenter (a0), inclination (i), longitude of the ascending node (Ω), and argument of periapsis (ω).

The Gaia mission identifies the apparent center of light (photocenter) from star systems. When a star has a stellar companion, then the photocenter is shifted and may not align with the actual center of the primary star. Notably, this deviation becomes significant for systems with a mass ratio M2/M1 > 0.6. For such systems, the barycentric semi-major axis can be underestimated by 5–9% at most (Barbato et al. 2023). In our sample, all systems exhibit a mass ratio below 0.6, and therefore we do not take this effect into account in our analysis. There are two cases (HD 3277 and HD 17289) where the RVs and astrometry are affected by the companion, and the implications are discussed in Sect. 4.2.

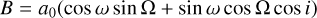

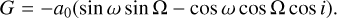

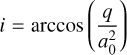

The parameters a0, i, Ω, and ω are the geometrical elements (also called the Campbell elements), which can be replaced by the Thiele Innes elements, defined by the following relations:

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

(3)

(3)

(4)

(4)

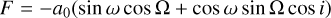

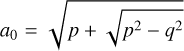

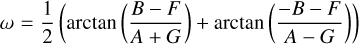

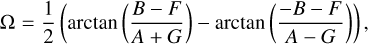

This is the basis used by Gaia to fit astrometric orbits. From the Thiele Innes elements, we can derive the Campbell elements with the following relations (Hilditch 2001):

(5)

(5)

(6)

(6)

(7)

(7)

(8)

(8)

The position angle of the line that links the actual orbital plane and the tangential plane of projection is known as Ω, or the node. In particular, the ascending node is the node at which the orbital motion is directed away from the Sun. This means that Ω can only be determined by combining RVs and positional measurements, since the two ellipses that are mirror images of one another with regard to the projection plane produce identical projections. As a result, there exists an inherent degeneracy of Ω ± π in astrometric solutions, which in turn also means that the same degeneracy exists in ω as this angle is measured from the ascending node. This degeneracy is resolved by comparing the ω values from both the RV and Gaia solutions. A more detailed explanation is given in Sect. 3.3.1.

3.2 RV model

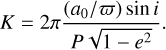

To fit these parameters to the RV measurements, we have to convert them to the standard RV parameters which are the semiamplitude K, the argument of periapsis ω, the period P, the periastron epoch Tp, and the eccentricity e.

From the Gaia solution, we already have the values for P, Tp, and e. Then, we convert the Thiele Innes elements to the Campbell elements using Eqs. (5) to (8), which gives us ω, a0 and i. Lastly, using a0, ϖ, i, P and e, we can calculate K as

(11)

(11)

We then build the model with the standard RV equation:

![$\upsilon \left( t \right) = {\gamma _j} + K\left[ {\cos \left( {v\left( t \right) + \omega } \right) + e\cos \left( \omega \right)} \right],$](/articles/aa/full_html/2023/12/aa47578-23/aa47578-23-eq13.png) (12)

(12)

where v is the true anomaly for which its calculation requires the orbital period P, the time of periastron Tp, and the eccentricity e. To do this calculation, one has to solve the Kepler equation, which is a transcendental equation.

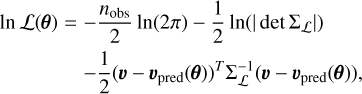

The final log likelihood we used is described as follows:

(13)

(13)

where θ is the vector of parameters, nobs is the total number of observations, Σ is the covariance matrix of the data, υ is the vector of measurements and υpred is the predicted model.

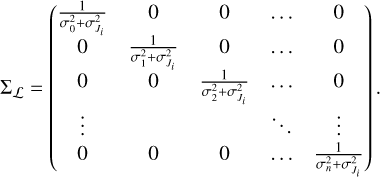

For the covariance matrix, we assumed independent normally distributed uncertainties with an additional jitter term  , one for each instrument i, to account for the remaining systematic errors that are not taken into account in the reported uncertainties σk:

, one for each instrument i, to account for the remaining systematic errors that are not taken into account in the reported uncertainties σk:

(14)

(14)

3.3 Data analysis

3.3.1 RV only

We start by performing a maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) of the RV model only with the RV data. We use the MLE of the parameters as the starting point to run a Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm to explore the posterior. We use the code samsam (Delisle 2022) which stands for Scaled Adaptive Metropolis SAMpler. We run the MCMC for at least 500 000 iterations after the burn-in, ensuring that the number of iterations is at least 50 times the autocorrelation time and that the chains reached a stationary state. We use the posterior distributions to estimate the minimum mass of the companion.

Before continuing to the joint analysis, we compare the values in common between the RV and the Gaia solution, which are, P, Tp, e, and ω to check their agreement and if the ω ± π correction to the Gaia solution has to be applied. As previously mentioned, this degeneracy is inherent in astrometry but is resolved through the inclusion of RVs. Hence, if the eccentricities between the RV and Gaia solutions exhibit a rough match, we proceed to verify if ω aligns as well. If not, it is likely offset by π. In such cases, we adjust ω and Ω from Gaia by π to account for this discrepancy. However, if the difference is less than π/2, we refrain from modifying the values of ω and Ω.

3.3.2 Joint RV and astrometric fit

As we do not have access yet to the astrometric time series from Gaia to actually fit both datasets together, we use the Gaia DR3 orbital solution as a prior on the joint model, but only using RV data.

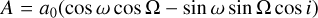

In the gaiadr3.nss_two_body_orbit table, we have access to the astrometric orbital solution and the covariance matrix of the fitted parameters. The “Orbital” type solutions have 12 free parameters that are fitted, these are: the position in right ascension and declination, the parallax (ϖ), the proper motions in right ascension and declination, the Thiele Innes elements (A, B, F, G), the period (P), the eccentricity (e) and the time of periapsis (Tp) relative to the Gaia epoch for DR3 (2016.0, Julian Date = 2457389.0).

We used all parameters except the positions and proper motions, as these are not relevant to the orbit itself. We kept the seven astrometric orbit parameters plus the parallax, which we need to transform the angular measurement of the semi-major axis in mas to au by dividing a0 by the parallax (Eq. (5)).

We extracted the relevant elements from the provided covariance matrix, which we use as a multivariate normal prior to these parameters. For ease of computation, we added the corresponding normal priors for the RV offsets of each instrument available to the diagonal of this matrix. We used a standard deviation of 20 m s−1, centered on the RV offset derived from the RV only fit.

This value is wide enough to accommodate for all targets, which allows for a standardized analysis.

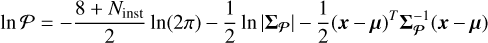

The mean µ and the covariance matrix Σ𝒫 of the Gaia prior are then described by:

![${\bf{\mu }} = \left[ {\varpi ,A,B,F,G,P,e,{T_p},{\gamma _i}} \right],$](/articles/aa/full_html/2023/12/aa47578-23/aa47578-23-eq17.png) (15)

(15)

Then the natural log of the prior 𝒫 is:

(17)

(17)

where Ninst is the number of RV instruments used, and x is a proposed solution to the fitted parameters µ.

In the combined analysis, the free parameters to be fitted include ϖ, A, B, F, G, P, e, Tp, γi,  . For the RV offsets (γi) and jitter terms (

. For the RV offsets (γi) and jitter terms ( ), there is one of each for each instrument available.

), there is one of each for each instrument available.

For the likelihood function we first convert from the Thiele-Innes elements to the Campbell elements (Eqs. (5)–(8)) taking into account the possible π flip of Ω and ω. We then calculate the RV model (Eq. (12)) and the likelihood (Eq. (13)).

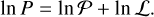

The final log probability of the full model is then calculated by summing Eqs. (13) and (17):

(18)

(18)

We use the results obtained from the RV-only MCMC as the starting point for the joint RV-Gaia MCMC. In the postprocessing, we sample points of the primary mass directly from a Gaussian distribution, with the mean and standard deviation from the values we got from the SED fit.

4 Results

In this section, we present the outcomes of the combined RV and astrometric fit for the previously described sample. Although a highly similar analysis was conducted by Winn (2022) for the planetary companions, we aim to replicate their study on these systems to validate their findings, ensure completeness, and provide new RV measurements for some of the stars. Moreover, our analysis extends to BDs and, as we subsequently demonstrate, certain binary systems as well.

Table A.3 contains the results from the RV-only MCMC fits, whereas the results of the MCMC analysis for the joint fits of all stars are presented in Table A.4. In Fig. B.1 plots for all analyzed targets are shown with the raw RVs, the final joint solution shown on top, the residuals from this model, the phase folded RVs, and a Z-score statistic showing the deviations for the orbital parameters between the joint solution and the Gaia DR3 solution. For the Z-score the corrected ω and Ω values are used.

We present two sections of results: one showcasing solutions we deem to be robust, and another addressing challenging cases with less reliable outcomes. The targets are listed in ascending order of the final true mass of the companion. We limit the extent of this results section by not providing individual descriptions for all targets. However, we do present descriptions for all planetary companions, targets that have new data, and cases in which the companion undergoes a noteworthy classification change.

A thorough examination of the joint RV-Gaia solution for HD 132406, HD 81040, HD 175167, and HD 114762 has already been conducted by Winn (2022), and our analysis yields similar results. For a detailed analysis, we refer the reader to their study. The only notable dissimilarity lies in the estimation of companion masses, as we employed our own estimation of primary masses. Table A.4 still presents our MCMC solutions for these targets.

4.1 Robust solutions

4.1.1 BD-170063

BD-170063 is a K4 star at a distance of 34.5 pc with a Gaia magnitude of G = 9.2 and a mass of 0.778 ± 0.037 M⊙. A giant planet at a period of 655.6 ± 0.6 days and a minimum mass of 5.1 ± 0.12 MJup was discovered by Moutou et al. (2009) using the HARPS spectrograph and since the publication, an additional five RVs were taken with HARPS. Additionally, there are also 12 RVs taken with the HIRES instrument, and here we present 14 RV measurements taken with the CORALIE spectrograph. All these additional measurements have never been used to reanalyze this system, which brings the total to 55 measurements on an observation baseline of 19 yr.

Winn (2022) already performed a combined Gaia and RV fit, but only used the original HARPS data released in 2009. We repeat the analysis here for completeness and include the 10 additional years of data available to improve the precision of the orbital parameters.

The joint fit converged well; however, there are strong correlations between all the Thiele Innes coefficients. Specifically, there are positive correlations between AF and BG, and negative correlations between the rest of the combinations. This results in a negative correlation between the mean anomaly and the longitude of the ascending node, and between the inclination and the semi major axis. The orbit is close to edge on at  deg, which results in a true mass of the companion of 5.325 ± 0.036 MJup, which locks its status as a giant planet.

deg, which results in a true mass of the companion of 5.325 ± 0.036 MJup, which locks its status as a giant planet.

All orbital parameters from the combined fit MCMC can be found in Table A.4. Indeed, with the additional RV data, we obtained a two to four-fold improvement in the precision of the orbital parameters compared to those obtained by Winn (2022).

4.1.2 HD 68638

HD 68638 is a late G type star at a distance of 32.5 pc and a mass of 1.00 ± 0.12M⊙. A companion to HD 68638 was announced in Holl et al. (2023) based on the availability of RVs from the ELODIE spectrograph and their agreement with the Gaia astrometric solution for this system.

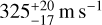

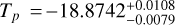

From the RV-only fit we obtain a good fit with an orbital period of 240.7 ± 0.4 days, an RV semi-amplitude of  , an eccentricity of 0.56 ± 0.04, and a minimum mass of 8.25 ± 0.07 MJup. The period, time of periastron and ω are all within 2-σ of the Gaia only solution, however there is disagreement in the eccentricity. Gaia reports an eccentricity of 0.31 ± 0.06, which is more than 4-σ away from the RV-only fit. Still, the system looks good for a combined Gaia-RV fit.

, an eccentricity of 0.56 ± 0.04, and a minimum mass of 8.25 ± 0.07 MJup. The period, time of periastron and ω are all within 2-σ of the Gaia only solution, however there is disagreement in the eccentricity. Gaia reports an eccentricity of 0.31 ± 0.06, which is more than 4-σ away from the RV-only fit. Still, the system looks good for a combined Gaia-RV fit.

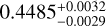

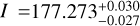

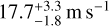

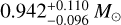

A joint Gaia-RV fit was performed with good convergence on all parameters. The eccentricity tension is settled at  , which meets in the middle, but stays closer to the eccentricity obtained in the RV-only fit. The semi-amplitude got reduced by 25 m s−1 to 300 ± 15 and the inclination converged to 166.51 ± 0.63 deg, resulting in a true mass of the companion of 35.1 ± 1.4. Removing the planetary status it had from the minimum mass and moving it inside the 30–55 MJup mass range.

, which meets in the middle, but stays closer to the eccentricity obtained in the RV-only fit. The semi-amplitude got reduced by 25 m s−1 to 300 ± 15 and the inclination converged to 166.51 ± 0.63 deg, resulting in a true mass of the companion of 35.1 ± 1.4. Removing the planetary status it had from the minimum mass and moving it inside the 30–55 MJup mass range.

4.1.3 HD 91669

HD 91669 is an early K type star at 71.8 pc. A BD candidate was discovered by Wittenmyer et al. (2009) using data from the Tull Spectrograph installed at the 2.7 m Harlan J. Smith Telescope at the McDonald Observatory. This BD candidate has a minimum mass of 30.6 ± 2.1 MJup, and sits on an eccentric orbit (e = 0.448 ± 0.002) with a period of 497.5 ± 0.6 days. Later, Sahlmann et al. (2011) tried to constrain this system using HIPPARCOS astrometry, but without success.

In the RV-only fit, we obtain the same results as reported in Wittenmyer et al. (2009). There is good agreement with the Gaia solution in the period, time of periastron, and ω, however, there is a slight disagreement in the eccentricity. The RV-only fit gives an eccentricity of 0.449 ± 0.003, while Gaia reports a value of 0.317 ± 0.062, a difference of just over 2-σ.

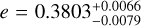

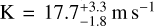

We performed the joint Gaia-RV fit and obtained good convergence on all parameters. The eccentricity did not budge from the RV-only result, staying at  . An inclination of

. An inclination of  deg cemented HD 91669b’s position in the BD regime with a true mass of 38.09 ± 0.64 MJup.

deg cemented HD 91669b’s position in the BD regime with a true mass of 38.09 ± 0.64 MJup.

4.1.4 HD 30246

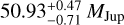

HD 30246 (HIP 22203) is a G1 star located at 51 pc from the Sun with our SED fit resulting in a mass of 0.956 ± 0.081 M⊙. A BD candidate was found orbiting HD 30346 by Díaz et al. (2012) using data from the SOPHIE spectrograph with a minimum mass  on a 990.7 ± 5.6 day orbit and an eccentricity of e = 0.838 ± 0.081. Since no constraints were found from the HIPPARCOS astrometric data at the time, a true mass estimation was not possible.

on a 990.7 ± 5.6 day orbit and an eccentricity of e = 0.838 ± 0.081. Since no constraints were found from the HIPPARCOS astrometric data at the time, a true mass estimation was not possible.

Since the publication of Díaz et al. (2012), 30 new RV measurements are available for HD 30246 in the SOPHIE archive, spanning from August 2011 to November 2016. We performed an RV-only fit including this new data to derive updated orbital parameters for HD 30246b. The posterior estimates for the orbital parameters from this RV-only fit can be found in Table A.3. We obtain a period of 989.53 ± 0.55 days, an RV semi-amplitude of 1145.2 ± 4.6 m s−1, a lower eccentricity of 0.6588 ± 0.0029, and a lower minimum mass of 41.0 ± 2.3 MJup, which is partly because our measurement for the primary mass is lower than the one reported by Díaz et al. (2012).

The Gaia solution agrees well with the RV solution we obtained, all parameters being within Thus, a combined Gaia-RV fit was performed successfully, giving good constrains on the orbital inclination of the orbiting body. We recover a 990.08 ± 0.58-day orbit, with a semi-amplitude K = 1143.8 ± 4.9 m s−1, an eccentricity of e = 0.6605 ± 0.0030, and an orbital inclination of 85.0 ± 1.2 deg, close to edge-on, which leaves the mass of the BD similar to its minimum mass at 42.18 ± 0.23 MJup. This means that this companion retains its status as a BD and within the 30–55 MJup mass range.

4.1.5 BD-004475

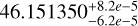

BD-004475 (HIP 114458, Gaia DR3 2651390587219807744) is a G type star located at 42 pc from the Sun. From our SED fits, we estimate its mass at 1.07 ± 0.11 M⊙. A BD candidate companion to this star was announced in Dalal et al. (2021) on a 723.2 ± 0.74 days orbit, an eccentricity of e = 0.39 ± 0.01, and a minimum mass of 25.05 ± 2.23 MJup. Using the astrometric excess noise from Gaia DR1, they found a mass upper limit for BD-004475b of 125 MJup.

The joint solution converges to an orbit with a period of 723.71 ± 0.83 days, an eccentricity of  , and an inclination of

, and an inclination of  deg which results in a true mass for BD-004475b of

deg which results in a true mass for BD-004475b of  . This is the last BD companion of this sample to fall inside the 30–55 MJup mass range.

. This is the last BD companion of this sample to fall inside the 30–55 MJup mass range.

4.1.6 HD 77065

HD 77065 is a G type star located at a distance of 33 pc and a mass of 0.791 ± 0.042 M⊙. A BD companion candidate was first found by Latham et al. (2002) using data from the SOPHIE spec-trograph. Later, Wilson et al. (2016) present additional data and improved precision to the orbital elements, obtaining an orbit with a period of 119 days, an eccentricity of e = 0.69, and a minimum mass of 41 ± 2 MJup. Gaia finds this same companion, and a joint Gaia-RV fit provides the same basic orbital parameters with an inclination of 41.52 ± 0.55 deg, which results in a true mass of  . This new mass estimate removes the BD from the 30-55 MJup mass range, but still clearly in the BD domain.

. This new mass estimate removes the BD from the 30-55 MJup mass range, but still clearly in the BD domain.

4.1.7 CD-4610046

CD-4610046 is a G star at a distance of 103 pc from the Sun and a mass of 0.860 ± 0.049 M⊙. A BD candidate companion to this star was announced in Holl et al. (2023) with Gaia and the support of 17 RV measurements of the CORALIE spectrograph that have been taken between 2017 and 2018, which we present in this work.

We performed an RV only fit to obtain a robust orbital solution. We ran the MCMC with one keplerian in the model and obtained an orbit with a 242.48 ± 0.31 day period, an RV semi-amplitude of 1978 ± 13 m s−1, an eccentricity of  , and a minimum mass of 49.6 ± 1.9MJup. This would put this companion right at the upper edge of the 30–55 MJup mass range. We have the Gaia astrometric solution available for this system, and a joint Gaia-RV fit is possible.

, and a minimum mass of 49.6 ± 1.9MJup. This would put this companion right at the upper edge of the 30–55 MJup mass range. We have the Gaia astrometric solution available for this system, and a joint Gaia-RV fit is possible.

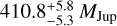

In the joint Gaia-RV fit we obtain good results for the complete orbit of CD-4610046b, with a period of 242.32 ± 0.28 days, an eccentricity close to the RV result of  and an inclination of 128.9 ± 1.1 deg, which results in a true mass of the companion of

and an inclination of 128.9 ± 1.1 deg, which results in a true mass of the companion of  . This removes the companion from the BD driest mass region and is now a high mass BD.

. This removes the companion from the BD driest mass region and is now a high mass BD.

4.1.8 HD 52756

HD 52756 is an early K type star at a distance of 32 pc. A 59.3 ± 2.0 MJup BD candidate companion was first discovered by Sahlmann et al. (2011) on a 52.8 day orbit.

In this study, we introduce a new RV measurement acquired using the CORALIE spectrograph. We performed both RV-only and combined Gaia-RV fits with this additional data point. However, our analysis indicates that the results are almost identical to the ones presented in the previous study by Sahlmann et al. (2011) except for an updated true mass estimate of  .

.

4.1.9 HD 140913

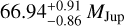

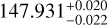

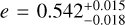

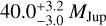

HD 140913 is G type star at 49 pc, with an estimated mass of 0.987 ± 0.087 M⊙. A BD candidate companion was first Article number, page 6 of 24 published by Stefanik et al. (1994) with data from the CORAVEL spectrograph, and later analyzed by Mazeh et al. (1998) and Halbwachs et al. (2000). This companion orbits at a period of  days, with an eccentricity of

days, with an eccentricity of  and with a minimum mass of

and with a minimum mass of  . A combined Gaia-RV fit gives an orbital inclination of 30.3 ± 1.3 deg, which results in a true mass of

. A combined Gaia-RV fit gives an orbital inclination of 30.3 ± 1.3 deg, which results in a true mass of  . This is the first companion in this sample that turns out to be a very low mass star.

. This is the first companion in this sample that turns out to be a very low mass star.

4.1.10 HD 148284

HD148284 is a G type star at a distance of 122 pc from the Sun and an estimated mass of 1.39 ± 0.2 M⊙. Ment et al. (2018) reported the existence of a BD candidate companion using data from the HIRES spectrograph. The companion was reported to have an orbital period of 339 days, an eccentricity of e = 0.39, and a minimum mass of 33.7 ± 5.5 MJup. Our combined Gaia-RV fit converged well to similar orbital parameters, and an orbital inclination of  deg which results in a true mass of the companion of

deg which results in a true mass of the companion of  , well within the stellar domain.

, well within the stellar domain.

4.1.11 HD 48679

HD 48679 is a G0 type star at a distance of 67 pc from the Sun and has an estimated mass of 1.034 ± 0.097 M⊙. Kiefer et al. (2019) announced the presence of a 36.01.3 MJup BD candidate companion discovered with RV measurements from the SOPHIE spectrograph. This companion orbits at a period of 1111.61 ± 0.30 days and a semi-major axis of 2.145 ± 0.037 au. Using the astrometric excess noise from Gaia DR2, they predicted the inclination to be between 41 and 65 deg. However, our combined Gaia-RV fit results in an inclination of 20.87 ± 0.18 deg, which puts this companion in the very low mass star regime at  .

.

4.1.12 HD 112758

HD 112758 is an early K type star at a distance of 20 pc from the sun and has an estimated mass of 0.815 ± 0.071 M⊙. A 33 MJup BD candidate companion was first discovered by Mayor et al. (1997) using data from the CORAVEL spectrograph. It was later found to be a binary using astrometric data from HIPPARCOS (Halbwachs et al. 2000; Zucker & Mazeh 2001).

We present 9 new RV measurements taken with the CORALIE spectrograph taken in 2018. The results of the RV only analysis can be found in Table A.3, where we find a 5-fold improvement in the precision of the orbital parameters because of the much higher instrumental precision of CORALIE compared to CORAVEL. The combined Gaia-RV fit converged well without any significant tension in its results. We obtain an orbital inclination of 8.716 ± 0.029 deg, which puts the true mass of the companion at 257.28 ± 0.93 MJup.

4.1.13 HD 164427

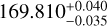

HD 164427 is an early G type star at a distance of 38 pc from the Sun. A BD candidate companion was first announced by Tinney et al. (2001) using data from the UCLES spectrograph installed at the Anglo Australian Telescope. They found a 46.4 ± 3.4 MJup companion with an orbital period of 108.55 ± 0.04 days. Later, using HIPPARCOS data, Zucker & Mazeh (2001) found its companion to be stellar with an estimated orbital inclination of 8.5 deg, reporting a true mass estimate of 367 ± 84 MJup. Lastly, Sahlmann et al. (2011) analyzed the system again with HIPPARCOS data, but this time adding new data from the CORALIE spectrograph, and they found a slightly less inclined orbit with an inclination of 11.8 deg and thus a lower mass of 272 MJup.

In this work, we present an additional 9 RV measurements taken with the CORALIE spectrograph from 2011 until 2017. In our analysis, we combine the Doppler data from all available instruments (CORAVEL, UCLES, and CORALIE). The results from the RV-only fit can be found in Table A.3. Merging the supplementary data with all other datasets led to a significant improvement in the precision of orbital parameters, with an increase of nearly an order of magnitude compared to Sahlmann et al. (2011).

We performed the combined Gaia-RV fit with success and find an orbital period of 108.53855 ± 3.3e - 4 days, an eccentricity of e = 0.54944 ± 7.3e + 4, and an inclination of  deg, which results in a true mass of the companion of 354.6 ± 2.1 MJup.

deg, which results in a true mass of the companion of 354.6 ± 2.1 MJup.

4.1.14 HD 162020

HD 162020 is an early K-type star at a distance of 31 pc from the Sun and has an estimated mass of 0.797 ± 0.042 M⊙. A companion to this star was first discovered by Udry et al. (2002), using RV data from the CORALIE spectrograph. They reported the existence of a hot BD orbiting with an orbital period of 8.4 days, an eccentricity of e = 0.277, and a minimum mass of 14.4MJup. From calculations of the measured projected rotational velocity and circularization time, they estimated that the companion is probably a low mass BD. However, they could not exclude the possibility of it being a low mass star. Later, Sahlmann et al. (2011) reanalyzed HD 162020 using HIPPARCOS astrometry, but the sensitivity of HIPPARCOS was not high enough to pick up its companion.

Here, we present two decades of updated CORALIE data, encompassing 55 additional RV measurements. By conducting an RV-only analysis, we achieved notable enhancements in the accuracy of the orbital parameters. This includes a substantial 20-fold increase in the precision of the orbital period.

We proceeded with the combined Gaia-RV fit and obtained results that agree well with the independent RV analysis. We obtain an orbital period of  days, an eccentricity of e = 0.28126 ± 5.7e − 4, a time of periastron of

days, an eccentricity of e = 0.28126 ± 5.7e − 4, a time of periastron of  days, and a near face on inclination of

days, and a near face on inclination of  deg. This results in a true mass of the companion of

deg. This results in a true mass of the companion of  , which puts it firmly in the stellar regime.

, which puts it firmly in the stellar regime.

4.2 Challenging cases

In this subsection, we explore challenging cases encountered during our joint Gaia-RV fit. Discrepancies between the Gaia and RV solutions primarily contribute to the lack of a robust and reliable combined fit. We observe that these inconsistencies are mainly attributed to the unreliability of the Gaia data for these targets, while RV-only solutions remain mostly robust with the available Doppler data.

4.2.1 HIP66074

HIP66074 is a late K dwarf according to an effective temperature estimation of  K, from the teff_gspspec column in the gaiadr3.astrophysical_parameters table from Gaia DR3. From the SED fits, we obtained a primary mass of 0.73 ± 0.03 M⊙.

K, from the teff_gspspec column in the gaiadr3.astrophysical_parameters table from Gaia DR3. From the SED fits, we obtained a primary mass of 0.73 ± 0.03 M⊙.

HIP 66074b is one of only two astrometric planet discoveries by Gaia, presented by Holl et al. (2023) and Gaia Collaboration (2023b). The cited works report the existence of a planetary companion at a period of 297.6 days.

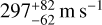

Using the available HIRES RV data, the RV-only fit converges well to a period of  days,

days,  , eccentricity of 0.38 ± 0.11, and a minimum mass of 0.44 ± 0.05 MJup. However, because there are only 10 RV measurements available, the False Alarm Probability of this signal is at 33%, much higher than the usual 1% or 0.1% used in RV surveys to confirm the presence of a companion.

, eccentricity of 0.38 ± 0.11, and a minimum mass of 0.44 ± 0.05 MJup. However, because there are only 10 RV measurements available, the False Alarm Probability of this signal is at 33%, much higher than the usual 1% or 0.1% used in RV surveys to confirm the presence of a companion.

The joint fit MCMC had a lot of struggle to converge, needing 600 000 iterations to reach convergence, as a result of a discrepancy between the Gaia solution and the RV only solution. There is a big discrepancy between the estimated RV semiamplitude from the Gaia solution ( ) and the actual RV semi amplitude that was measured with the HIRES spectrograph (

) and the actual RV semi amplitude that was measured with the HIRES spectrograph ( ). Additionally, the Gaia solution reports an inclination that is edge-on, but this is incompatible with the fact that the minimum mass of the RV solution is only 0.44 MJup, when the Gaia only solution would put the mass of the companion at 9 MJup.

). Additionally, the Gaia solution reports an inclination that is edge-on, but this is incompatible with the fact that the minimum mass of the RV solution is only 0.44 MJup, when the Gaia only solution would put the mass of the companion at 9 MJup.

In the joint solution, the inclination goes all the way down to  deg to reconcile the difference in semi amplitudes. This puts the estimation of the inclination in the joint solution more than 17 σ away from the Gaia solution. This shows that the tension in the model was much greater than the prior constraint to keep the inclination close to 90°.

deg to reconcile the difference in semi amplitudes. This puts the estimation of the inclination in the joint solution more than 17 σ away from the Gaia solution. This shows that the tension in the model was much greater than the prior constraint to keep the inclination close to 90°.

Winn (2022) shows that a nonzero flux ratio can partially explain this problem, however, they also show that the fitted flux ratio they obtain is incompatible with the expected planetary mass of the companion. As they already hypothesized, this big difference between the Gaia and the RV solution could be due to an unknown companion in the system. However, it is also possible that the astrometry of HIP 66074 suffers from instrument systematics. More RV measurements would be needed to confirm this signal at 300 days, and the release of Gaia DR4 will allow for a thorough joint analysis between the RVs and astrometry. Until then, the planetary nature of HIP 66074b cannot be confirmed and remains a candidate.

4.2.2 HD 40503

HD 40503 is an early K dwarf located at a distance of 39 pc. Based on our spectral energy distribution (SED) fit, we estimate the primary mass to be 0.797 ± 0.044 M⊙. This discovery represents the second independent candidate exoplanet detection from Gaia DR3 astrometry (Holl et al. 2023; Gaia Collaboration 2023b). As previously noted by Holl et al. (2023), Winn (2022), and Marcussen & Albrecht (2023), although Gaia’s determined orbital period aligns with the best-fit Keplerians obtained from RV measurements, the available RV data remains insufficient to confidently constrain this system due to the presence of stellar activity or contamination. Therefore, it is currently unfeasible to perform a joint fit until additional RV data and/or the complete astrometry become available.

4.2.3 HR810

HR810 (Iota Horologium, HD 17051) is an F8 star at a distance of 17 pc. A giant planet was discovered around HR810 by Kürster et al. (2000). A good review about this systems’ solution was already shown by Winn (2022). They report that the analysis of HR 810 using RV-only and Gaia data reveals significant discrepancies and uncertainties in orbital parameters, notably affected by systematic errors and a known issue with Gaia’s two-body fitting code for low eccentricity orbits. Due to these inconsistencies, the joint analysis of both datasets is inconclusive, necessitating caution in its interpretation. Our joint fit analysis resulted in the same conclusion, which is why we restrain from showing the joint fit solution.

4.2.4 HD 5433

HD 5433 is a G-type star at a distance of 64 pc from the Sun and with a mass of 0.984 ± 0.096 M⊙. A highly eccentric BD candidate companion was found by Dalal et al. (2021) with data from the SOPHIE spectrograph. They announced an orbital period of 576.6 ± 1.59 days, an eccentricity of e = 0.81 ± 0.02 and a minimum mass of 49.11 ± 3.4MJup. A joint Gaia-RV fit was performed with success, resulting in an orbital inclination of 41.34 ± 0.77 deg, which gives a true mass of  retaining its position as a BD, but moving away from the desert.

retaining its position as a BD, but moving away from the desert.

There exists a significant disparity between the semi-major axis estimates obtained from Gaia and the joint fit. This discrepancy is further evident when comparing the expected RV semi-amplitudes. Gaia predicts a value of 295 m s−1, which is six times smaller than the estimate derived from the RVs, measuring 1790 m s−1. One possible explanation for this discrepancy is an inaccurate inclination estimation by Gaia, which reports an inclination of I = 12 ± 39 deg. In contrast, our joint fit yielded an inclination four times higher at I = 41.34 ± 0.77 deg in order to reconcile the astrometry with the RVs, but still compatible within 1σ.

Even though the exact cause of the semi-major axis discrepancy remains uncertain, and thus the provided solution should be taken with care, we anticipate gaining greater clarity upon the release of Gaia DR4.

4.2.5 HD 82460

HD 82460, is a G type star at a distance of 50 pc from the Sun. This star was observed with the SOPHIE spectrograph and Kiefer et al. (2019) announced a 73.2 ± 3.0 MJup BD candidate companion at a 590.90 ± 0.24 day orbit.

The results of the combined fit of the data from SOPHIE and Gaia exhibit suboptimal performance, as evidenced by a jitter of approximately 80 m/s. Additionally, the orbital parameters obtained from the combined fit are all approximately 1.5 standard deviations higher than the solutions from Gaia. However, the convergence of the combined fit is impressive, as it converges rapidly and the sampling is effective.

Our analysis suggests that the difference in the results may be attributed to the eccentricity estimation of Gaia, which obtains e = 0.73 ± 0.03, in contrast to the eccentricity from the RV data, which is e = 0.95 ± 0.02. This is a tension of more than 7 σ. In the joint fit, it seems that the likelihood is minimized by converging to the lower Gaia eccentricity and consequently increasing the RV jitter, even though this is likely the wrong solution.

Additionally, the lower eccentricity also results in a lower RV semi-amplitude. According to the Gaia solution, the estimated RV semi-amplitude (Eq. (11)) is K = 2046 m s−1, which is less than half the semi-amplitude obtained from the RV-only analysis. The lower K value from the combined fit leads to a contradictory smaller true mass than the minimum mass obtained from the RV data alone.

These discrepancies suggest potential issues with the Gaia solution, given our confidence in the RV solution. Further analysis of HD 82460 is required when the full astrometric time series becomes available in Gaia DR4 in order to identify an explanation for this tension between the two solutions. We present the complete results of the combined fit in Table A.4, but they should be interpreted with caution, as they may not be reliable.

4.2.6 HD 89707

HD 89707 is a G2 type star at a distance of 35 pc from the Sun with an estimated mass of 0.99 ± 0.13 M⊙. It was first started to be observed in 1982 with the CORAVEL spectrograph and was first identified as a spectroscopic binary by Duquennoy & Mayor (1991). Later it was analyzed by Halbwachs et al. (2000) and Sahlmann et al. (2011), where they flag it as 53.6 ± 7.4 MJup BD candidate with an orbital period of 298 days and an eccentricity of e = 0.9.

We present 13 new RV measurements taken with the CORALIE spectrograph between 2010 and 2021, taken after Sahlmann et al. (2011) did their analysis. Additionally, at the time of their publication, the 64 RV measurements from the CORAVEL spectrograph taken between 1982 and 1999 were not used in their analysis. In this work, we are presenting an updated analysis of this system, now with the complete dataset of both instruments. This represents 77 additional RV measurements for a total of 108, which means four times the observation baseline (close to 40 yr) and triple the amount of RV measurements.

We did an RV-only analysis, and we found a period of  days, a higher eccentricity of

days, a higher eccentricity of  , an RV semi-amplitude of 5070 ± 180 m s−1, and a minimum mass of 53.7 ± 4.5 MJup. Throughout all orbital parameters, we obtain almost an order of magnitude better precision to the ones reported by Sahlmann et al. (2011). The full orbital parameters from the RV fit can be seen in Table A.3.

, an RV semi-amplitude of 5070 ± 180 m s−1, and a minimum mass of 53.7 ± 4.5 MJup. Throughout all orbital parameters, we obtain almost an order of magnitude better precision to the ones reported by Sahlmann et al. (2011). The full orbital parameters from the RV fit can be seen in Table A.3.

After comparing the Gaia orbital solution to the RV solution, we find that the period and time of periastron match very well at less than 1σ. However, Gaia finds a lower eccentricity of 0.67 ± 0.20, but still less than 2σ away from the RV eccentricity. Still, the agreement is good enough and we continued with the combined Gaia-RV fit.

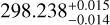

The result of the combined fit gives an even higher eccentricity compared to the RV fit. The posterior distribution shows to be concentrated at e = 1 with a downward tail. This behavior is unexpected as the eccentricity is well constrained by the RV data at e = 0.9464 ± 0.0041 and the prior information from Gaia should push it to an even lower value. A comparison of the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) between a model with an eccentricity of 0.94 and another with 0.98 resulted in a difference of –4, in favor of the former. This difference, however, is not deemed statistically significant. In really high eccentricities it is difficult to explore the peaks of RV and thus higher eccentricities are always possible, however, this does not explain why the eccentricity posterior looks the way it does.

In the combined Gaia-RV fit we obtain an orbital inclination of 43.8 ± 1.1, which results in a true mass of  , but due to the discrepancies in the estimation of the eccentricity the solution should be taken with caution.

, but due to the discrepancies in the estimation of the eccentricity the solution should be taken with caution.

4.2.7 HD3277

HD 3277 is a late G type star at a distance of 29 pc from the Sun with an estimated mass of  . A potential BD candidate was found by Sahlmann et al. (2011) on a 46-day period orbit using RV data from the CORALIE spectrograph. In that same work, they conducted a comparative study with HIPPARCOS astrometry and determined that the companion to HD3277 was in fact a star with an estimated true mass of 344 ± 76 MJup.

. A potential BD candidate was found by Sahlmann et al. (2011) on a 46-day period orbit using RV data from the CORALIE spectrograph. In that same work, they conducted a comparative study with HIPPARCOS astrometry and determined that the companion to HD3277 was in fact a star with an estimated true mass of 344 ± 76 MJup.

Since Sahlmann et al. (2011) we have collected 10 additional RV measurements with the CORALIE spectrograph over a time span of 12 yr, which already provides us with an improved precision in the orbital parameters from the RV only fit by close to an order of magnitude (see Table A.3).

We performed the combined Gaia-RV fit with success, obtaining a period of  days, an inclination of

days, an inclination of  deg which results in a true mass of

deg which results in a true mass of  , considerably higher than the one reported by Sahlmann et al. (2011).

, considerably higher than the one reported by Sahlmann et al. (2011).

However, as reported in Sahlmann et al. (2011), the presence of a ~ 500 MJup companion results in its light contaminating the fiber and subsequently altering the cross-correlation function (CCF) and hence the RVs. This can be seen by the large scatter in the Full Width Half Maximum of the CCF, indicating the blended SB2 nature of this target. A similar phenomenon occurs in astrometry, as the binary nature of the system results in the photocenter being influenced by the companion and shifted away from the primary, thus affecting the orbital solution. If these effects are not accounted for, they introduce biases into the orbital solutions derived with both the RVs and Gaia astrometry. Specifically, the RV semi-amplitude and the astrometric amplitude are underestimated, which leads to an underestimation of the mass of the stellar companion. Fully separating each star’s contributions to the CCF requires an in-depth analysis, which is beyond the scope of this paper.

For this reason, the results for HD 3277 from both the RV only (Table A.3) and the joint MCMC fit (Table A.4) should be taken with caution, as a more thorough analysis is needed to take into account the shift of the photocenter in Gaia and the affected RVs.

4.2.8 HD 17289

HD 17289 is a G type star at a distance of 50 pc and has an estimated mass of 1.11 ± 0.17 M⊙. A companion to HD 17289 on a 536-day orbit was first discovered by Goldin & Makarov (2007) using only HIPPARCOS data. Then, Sahlmann et al. (2011) reanalyzed the system using both HIPPARCOS and RV data from the CORALIE spectrograph. They find better constrained orbital parameters and discover the companion to be a star with a mass of 547 ± 47 MJup, even though it would be a BD candidate from the RVs alone. More recently, Delisle & Ségransan (2022) analyzed this system again using a fully joint astrometric and RV model, obtaining similar results.

We present 6 new RV measurements taken with the CORALIE spectrograph from 2011 until December 2016. We perform an RV-only fit and obtain a 2 to 7-fold improvement in precision of the orbital parameters thanks to the new Doppler data (see Table A.3).

There is good agreement for the period, and time of periastron between the Gaia and RV solutions. However, the eccentricities look close at 0.528 ± 0.002 and 0.492 ± 0.005 for the RV and Gaia solutions, respectively, but the small uncertainty on the Gaia estimate puts them at a distance of 7σ. Same for the ω, the RV and Gaia estimates are 8σ apart. We decided to go forward with the combined Gaia-RV fit with these discrepancies in mind.

From the combined Gaia-RV fit, we obtain an orbital period of  days, an eccentricity of e = 0.5152 ± 0.0037, and an inclination of I = 172.917 ± 0.044. This puts the true mass of the companion at

days, an eccentricity of e = 0.5152 ± 0.0037, and an inclination of I = 172.917 ± 0.044. This puts the true mass of the companion at  . There is still a strong tension (at >4σ) in the precise estimate of the eccentricity, ω and Ω. The origin of this tension is likely due to the impact of the companion on the RVs.

. There is still a strong tension (at >4σ) in the precise estimate of the eccentricity, ω and Ω. The origin of this tension is likely due to the impact of the companion on the RVs.

Similarly to HD 3277, the large mass of the stellar companion affects both the RVs and the astrometry. The derived orbital solution will be biased if the non-negligible flux ratio is not properly accounted for, and thus the mass of the companion will be underestimated. Such an analysis is beyond the scope of this paper, and therefore, we warn the readers to exercise caution with the orbital solution of HD 17289 provided in both Tables A.3 and A.4.

5 Discussion

5.1 General discussion

The sample presented in this study is limited in its representativeness, as it consists only of the giant planets and BD candidates that were verified and validated by Gaia. Hence, the general population-level insights that can be drawn from these results are of modest significance. Nonetheless, we can still present some general conclusions.

In Table A.4, the results for the combined Gaia-RV fit are shown for all targets. We split up the table in two, for the robust solutions and for the systems where the solution might be unreliable because of discrepancies between the Gaia solution and the RV solution. For this discussion, we only consider the systems where a reliable combined solution was found.

The use of Gaia astrometry in recent years has significantly enhanced the ability to accurately determine the true masses of giant planets and BDs. Using the PMa technique, Barbato et al. (2023) showed that 11 BD candidate companions from the CORALIE sample turn out to be stars. In this study, we add another eight to that list, as HD 17155 was already found to be a binary by Barbato et al. (2023). For HD 3277, HD 89707, HD 151528, and HD 164427A, Barbato et al. (2023) did not manage to get additional constraints as the semi-major axis of their orbits are less than 1 au which prevents a reliable analysis using PMa. In another case, Venner et al. (2021) show that the low mass BD companion candidate to HD 92987 (Rickman et al. 2019) is actually an M dwarf.

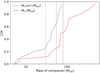

This highlights the prominence of the scarcity of BDs and that the occurrence rate of BDs in the 30–55 MJup mass range might be lower than we thought. Identifying these false BD candidates is crucial if we really want to have robust observational constraints for planet formation theories. In Figs. 1–3 we show the change in the distribution of masses from the RV only to the combined Gaia-RV mass, which all show a clear general increase in the masses of the companion. The median mass increase factor is of 1.88, which is higher than the expected factor of 1.15 assuming a median inclination of I = 60° from randomly oriented orbits. This is a consequence of Gaia being more likely to detect face-on orbits due to the properties of its scanning law (Gaia Collaboration 2023b).

In Fig. 4, we show the distribution of true masses and orbital periods. There is a clear downward trend in the masses for longer orbital periods. This can be easily associated with the detection capabilities of Gaia, where longer orbits produce larger astrometric signatures and thus smaller masses are detectable. For short orbits, the mass of the companion has to be larger for the astrometric signature to be of similar magnitude. The smallest orbit found in this sample is that of HD 162020B, whose period is only 8.4 days. However, its detection by Gaia was possible solely due to its stellar nature.

When comparing the results obtained from Gaia only to the results obtained from RV only, it is apparent that Gaia still struggles to accurately determine the eccentricity of the orbits, typically reporting lower values than the ones we obtain from the RV analysis. This is possibly due to the limited time span and sampling of Gaia observations for DR3 and a still not-perfect outlier rejection scheme in the Gaia time series analysis. This issue was previously acknowledged by (Holl et al. 2023, Fig. 3), who noted that Gaia tends to fit lower eccentricities than the reference values from RV surveys. Additionally, some of the large Z-scores seen in Fig. B.1 could be due to underestimated uncertainties in the Gaia solution. Holl et al. (2023) described that the covariance matrix of the parameters was estimated locally around the best fit solution (from the partial derivatives of the model) which could lead to underestimation.

In contrast, the period is typically recovered with high accuracy by Gaia and in agreement with the period derived from RV only. The high accuracy of the period measurements obtained by Gaia highlights the potential of this data source to contribute to our understanding of companion populations, despite its current limitations in determining the eccentricity of the orbits.

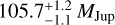

|

Fig. 1 [Minimum/True] mass of the companion and the semi-major axis for the RV-only solutions (blue) and the joint Gaia-RV solution (red). The horizontal solid lines show the 30, 55, and 80 MJup mass limits, respectively. A kernel density estimate (KDE) plot is shown on top for each set of solutions. Only companions with robust solutions are shown, i.e., targets from the first section of Table A.4. |

|

Fig. 2 Histogram of companion masses for minimum and true masses. The horizontal solid lines show the 30, 55, and 80 MJup mass limits, respectively. |

|

Fig. 3 Cumulative distribution function for the masses of the companions in minimum (blue) and true (red) masses. The horizontal solid lines show the 30, 55, and 80 MJup mass limits, respectively. |

|

Fig. 4 True mass of the companions versus the orbital period. The horizontal solid lines show the 30, 55, and 80 MJup mass limits, respectively. The dashed lines show the expected detection mass limits for companions around solar like stars (1M⊙) at a distance of 35pc considering astrometric signatures of α = 200 µas (approximate current capacity) and a = 75 µas (approximate astrometric signature expected to be detectable in Gaia DR4 considering a base uncertainty of 25µas and a signal-to-noise ratio, S/N, of 3). |

5.2 BD companions in the CORALIE survey

These updated masses of BD companions allows us to revisit their occurrence rate in the CORALIE survey. The CORALIE survey focuses on a volume-limited sample consisting of 1647 solar-type stars (FGK) located up to a distance of 50 pc (Pepe et al. 2002; Udry et al. 2002). Within this sample, Sahlmann et al. (2011) identified 11 BD candidates with masses ranging from 13 to 80 MJup that were found in close orbits up to 10 au. However, it should be noted that the completeness of the survey up to 10 au was not guaranteed at that time. The CORALIE survey had been running for 12 yr, providing complete orbit data only for companions up to a ~ 5 au. Some companions with larger separations could be inferred from incomplete orbit data, but the detection completeness up to 10 au was not ensured. Now, with the CORALIE survey having run for 25 yr, we can confidently assert the detection of companions with complete orbits at a separation of 10 au.

Among the 11 BDs initially considered by Sahlmann et al. (2011; HD4747, HD 52756, HD 74014, HD 89707, HD 154697, HD 162020, HD 167665, HD 168443, HD 189310, HD 202206, HD 211847), subsequent studies have revealed that five of them are actually of stellar nature. These stars are HD89707 and HD 162020 (this work), HD 154697 (Barbato et al. 2023), HD211847 (Moutou et al. 2017), and HD202206 (Benedict & Harrison 2017). On the other hand, for the remaining six stars, some of their companions have been confirmed as BDs: HD74014, HD167665, HD4747 (Barbato et al. 2023), and HD 52756 (this work).

Since the publication of Sahlmann et al. (2011), additional close-in BDs have been discovered in the CORALIE sample. These include HD 28454, HD 30774, HD 112863, HD 153284, HD 184860A, HD 206505, and HD 219709 (Barbato et al. 2023). Among these, the companions of HD 112863 and HD 206505 were confirmed as BDs through an analysis of proper motion anomalies, while for the others either the period of the companion is too short or it is not available in the HIPPARCOS catalog which prevents this type of analysis.

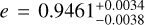

The revised count of BDs with masses ranging from 13 to 80 MJup and orbits below 10 au in the CORALIE survey now stands at 13, namely HD 28454, HD 30774, HD 4747, HD 52756, HD 74014, HD 112863, HD 153284, HD 167665, HD 168443, HD 184860A, HD 189310, HD 206505, and HD 219709. Among these companions, six (HD 28454, HD 30774, HD 153284, HD184860A, HD189310, and HD219709) still require determination of their true masses. For three of them (HD 28454, HD153284, and HD219709), their minimum mass is above 70 MJup, thus it is likely that some of these companions are actually stars. Taking into account this updated list, we can estimate a tentative occurrence rate of close-in (<10 AU) BD companions around Sun-like stars within 50 pc. Using binomial statistics, the rate is  which is slightly higher than the estimate in Sahlmann et al. (2011) but compatible. The increase is explained by the longer time range of the observations, covering better out to 10 AU. It is important to highlight that there remains a possibility that some candidates from the CORALIE sample initially identified as planetary companions may turn out to be BDs, or for some of these BDs to be stars.

which is slightly higher than the estimate in Sahlmann et al. (2011) but compatible. The increase is explained by the longer time range of the observations, covering better out to 10 AU. It is important to highlight that there remains a possibility that some candidates from the CORALIE sample initially identified as planetary companions may turn out to be BDs, or for some of these BDs to be stars.

Of these 13 BD companions, only 1 has a mass in the 30–55 Mjup range, namely HD 30774 with m sin(I) = 41MJup (Barbato et al. 2023). However, its true mass is still to be determined.

6 Summary and conclusions

We revisited stars known to have substellar companion candidates that were initially detected through RVs and later validated using astrometry data from Gaia. By using the orbital solution provided by Gaia DR3, we incorporated it as a prior in the analysis of the available RV data. This joint Gaia-RV analysis allowed us to derive a comprehensive 3D representation of the companion’s orbit, enabling us to determine their true mass and unveil their actual nature.

Our analysis focused on 32 targets deemed suitable for this investigation, specifically those with substellar companion candidates and no additional companions that would hinder a comparison with the Gaia orbital solution. Among these, two companions were deemed unsuitable for a joint analysis because of large inconsistencies between the RVs and the Gaia solutions, as well as unreliable RVs. An additional six companions yielded joint solutions that exhibited some discrepancies between the RVs and Gaia; these solutions should be approached with caution. Thus, 24 companions were found to have robust joint Gaia-RV solutions.

We examined the companions previously classified as planets based on their RV analysis, which had already been reevaluated by Winn (2022) using a similar approach. Our results largely aligned with theirs, but thanks to the inclusion of new RV data, we obtained improved orbital constraints for BD-170063. We also determined that the companion HD 68638A is a BD, and once again confirmed the stellar nature of HD 114762B.

Among the BD candidates, ten previously considered to have minimum masses falling between the 30–55 MJup mass range were found to be either high-mass BDs (HD 77065 and CD-4610046) or low-mass stars (HD 140913, HD 148284, HD 89707, HD 48679, HD 112758, and HD 164427). This significant reduction in BD candidates within the desert region suggests an even lower occurrence rate of these companions. The improved constraints and identification of the true nature of many of these companions will greatly enhance the refinement and reliability of high-mass planet and BD populations. This in turn will lead to tighter constraints on future planet formation theories.

The main changes in companion masses can be summarized by categorizing them into the three ranges based on their minimum masses:

[<30 MJup]: seven companions in the sample, with two being within 30–55 MJup and two being stars (>80MJup);

[30–55 MJup]: nine companions in the sample, with two remaining in this range, two being high-mass BD (55– 80 MJup), and five being stars (>80 MJup);

[55–80 MJup]: eight companions in the sample, with four being stars (>80 MJup).

We updated the analysis of close-in BD companions (13– 80 MJup) within 10 au of solar-type stars in the volume-limited CORALIE sample. Sahlmann et al. (2011) reported eleven BDs, but later studies showed that five of them were actually stars. Barbato et al. (2023) added seven new BDs to the sample. Out of 1647 stars in the CORALIE sample, we found 13 BD candidates, giving an upper limit for their occurrence rate of  .

.

There are still areas in need of improvement, as some joint solutions do not align with the RV-only solutions. We anticipate that Gaia DR4 will address most of these issues by providing not only a doubled observation baseline but also complete epoch astrometry, facilitating comprehensive combined analyses of RV and astrometry datasets (Delisle & Ségransan 2022). This upcoming release will significantly enhance our ability to detect objects with lower masses than is currently possible and provide a clearer understanding of the populations existing at the transitional boundary between planets and low-mass BDs within 5 au. Gaia DR4 will also prove invaluable in studying active and young stars, where the presence of planets poses challenges to RV measurements. These advancements will enable us to study BD populations and their orbital architectures as a function of the host stellar parameters with an unprecedented level of detail.

As mentioned previously, we had to exclude multi-planet systems from the analysis because Gaia DR3’s search was focused on a single companion, rendering a reliable joint analysis for multi-planet systems unfeasible. However, with the forthcoming Gaia DR4, we are confident that the study of multi-planet systems will become possible, enabling the detection of multi-giant systems.

Acknowledgements

This work has been carried out within the framework of the National Center of Competence in Research PlanetS supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation under grants 51NF40_182901 and 51NF40_205606. The authors acknowledge the financial support of the SNSF. This publication makes use of The Data & Analysis Center for Exoplanets (DACE), which is a facility based at the University of Geneva (CH) dedicated to extrasolar planets data visualisation, exchange and analysis. DACE is a platform of the Swiss National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) PlanetS, federating the Swiss expertise in Exoplanet research. The DACE platform is available at https://dace.unige.ch. This work has made use of data from the European Space Agency (ESA) mission Gaia (https://www.cosmos.esa.int/gaia), processed by the Gaia Data Processing and Analysis Consortium (DPAC, https://www.cosmos.esa.int/web/gaia/dpac/consortium). Funding for the DPAC has been provided by national institutions, in particular the institutions participating in the Gaia Multilateral Agreement. This work made use of Astropy (http://www.astropy.org): a community-developed core Python package and an ecosystem of tools and resources for astronomy (Astropy Collaboration 2013, 2018, 2022).

Appendix A Tables

Stellar parameters.

RV data used for our analysis for each target and their sources.

MCMC results from the RV-only fit.

MCMC results from the combined Gaia & RV fit.

Appendix B RV orbital solutions phase-folded plots

|

Fig. B.1 RV curves of the joint solution, residuals, and phase pholds for the companions detected around each star. Additionally, at the bottom we show the Z-score (the difference in standard deviations) between the Gaia only orbital solution and the combined Gaia-RV orbital solution. |

References

- Anders, F., Khalatyan, A., Chiappini, C., et al. 2019, A & A, 628, A94 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Armitage, P. J., & Bonnell, I. A. 2002, MNRAS, 330, L11 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Arriagada, P., Butler, R. P., Minniti, D., et al. 2010, ApJ, 711, 1229 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Astropy Collaboration (Robitaille, T. P., et al.) 2013, A & A, 558, A33 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Astropy Collaboration (Price-Whelan, A. M., et al.) 2018, AJ, 156, 123 [Google Scholar]

- Astropy Collaboration (Price-Whelan, A. M., et al.) 2022, ApJ, 935, 167 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Baranne, A., Mayor, M., & Poncet, J. L. 1979, Vistas Astron., 23, 279 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Baranne, A., Queloz, D., Mayor, M., et al. 1996, A & As, 119, 373 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Barbato, D., Ségransan, D., Udry, S., et al. 2023, A & A, 674, A114 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict, G. F., & Harrison, T. E. 2017, AJ, 153, 258 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, R., Shectman, S. A., Gunnels, S. M., Mochnacki, S., & Athey, A. E. 2003, SPIE Conf. Ser., 4841, 1694 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Boss, A. P. 1997, Science, 276, 1836 [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, T. D. 2021, ApJS, 254, 42 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, T. D., Dupuy, T. J., Li, Y., et al. 2021, AJ, 162, 186 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A. G. A. 2021, ARA & A, 59, 59 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R. P., Wright, J. T., Marcy, G. W., et al. 2006, ApJ, 646, 505 [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R. P., Vogt, S. S., Laughlin, G., et al. 2017, AJ, 153, 208 [Google Scholar]

- Cameron, A. G. W. 1978, Moon Planets, 18, 5 [Google Scholar]

- Casertano, S., Lattanzi, M. G., Sozzetti, A., et al. 2008, A & A, 482, 699 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Chabrier, G., Johansen, A., Janson, M., & Rafikov, R. 2014, in Protostars and Planets VI, eds. H. Beuther, R. S. Klessen, C. P. Dullemond, & T. Henning (Tucson: University of Arizona Press), 619 [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J., Dotter, A., Conroy, C., et al. 2016, ApJ, 823, 102 [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, W. D., & Hatzes, A. P. 1993, ASP Conf. Ser., 36, 267 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, W. D., Hatzes, A. P., & Hancock, T. J. 1991, ApJ, 380, L35 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dalal, S., Kiefer, F., Hébrard, G., et al. 2021, A & A, 651, A11 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Delisle, J.-B. 2022, Astrophysics Source Code Library [record ascl:2207.011] [Google Scholar]

- Delisle, J. B., & Ségransan, D. 2022, A & A, 667, A172 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, R. F., Santerne, A., Sahlmann, J., et al. 2012, A & A, 538, A113 [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Diego, F., Charalambous, A., Fish, A. C., & Walker, D. D. 1990, SPIE Conf. Ser., 1235, 562 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Dotter, A. 2016, ApJS, 222, 8 [Google Scholar]

- Duquennoy, A., & Mayor, M. 1991, A & A, 248, 485 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Eastman, J. D., Rodriguez, J. E., Agol, E., et al. 2019, arXiv e-prints [arXiv: 1907.09480] [Google Scholar]

- Feng, F., Butler, R. P., Vogt, S. S., et al. 2022, ApJS, 262, 21 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, D. A., Marcy, G. W., & Spronck, J. F. P. 2014, ApJS, 210, 5 [Google Scholar]