| Issue |

A&A

Volume 575, March 2015

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A45 | |

| Number of page(s) | 18 | |

| Section | Extragalactic astronomy | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201423972 | |

| Published online | 19 February 2015 | |

The radio relic in Abell 2256: overall spectrum and implications for electron acceleration⋆

1

Argelander Institut für Astronomie, Universität Bonn,

Auf dem Hügel 71, 53121

Bonn, Germany

e-mail: trasatti@astro.uni-bonn.de

2

SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research,

Sorbonnelaan 2, 3584 CA

Utrecht, The

Netherlands

3

Hamburger Sternwarte, Universität Hamburg,

Gojenbergsweg 112, 21029

Hamburg,

Germany

4

Dipartimento di Astronomia, Università di Bologna,

via Ranzani 1, 40127

Bologna,

Italy

5

INAF – Istituto di Radioastronomia, via Gobetti 101, 40129

Bologna,

Italy

6

Naval Research Laboratory, 4555 Overlook Ave, SW, DC

20375

Washington,

USA

Received: 10 April 2014

Accepted: 1 November 2014

Context. Radio relics are extended synchrotron sources thought to be produced by shocks in the outskirts of merging galaxy clusters. The cluster Abell 2256 hosts one of the most intriguing examples in this class of sources. It has been found that this radio relic has a rather flat integrated spectrum at low frequencies that would imply an injection spectral index for the electrons that is inconsistent with the flattest allowed by the test particle diffusive shock acceleration (DSA).

Aims. We aim at testing the origins of the radio relic in Abell 2256.

Methods. We performed new high-frequency observations at 2273, 2640, and 4850 MHz. Combining these new observations with images available in the literature, we constrain the radio-integrated spectrum of the radio relic in Abell 2256 over the widest sampled frequency range collected so far for this class of objects (63−10 450 MHz). Moreover, we used X-ray observations of the cluster to check the temperature structure in the regions around the radio relic.

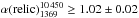

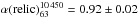

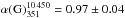

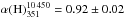

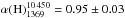

Results. We find that the relic keeps an unusually flat behavior up to high frequencies. Although the relic integrated spectrum between 63 and 10 450 MHz is not inconsistent with a single power law with α6310 450 = 0.92 ± 0.02, we find hints of a steepening at frequencies >1400 MHz. The two frequency ranges 63−1369 MHz and 1369−10 450 MHz are, indeed, best represented by two different power laws, with α631369 = 0.85 ± 0.01 and α136910 450 = 1.00 ± 0.02. This broken power law would require special conditions to be explained in terms of test-particle DSA, e.g., non-stationarity of the spectrum, which would make the relic in A2256 a rather young system, and/or non-stationarity of the shock. On the other hand, the single power law would make of this relic the one with the flattest integrated spectrum known so far, even flatter than what is allowed in the test-particle approach to DSA. We find a rather low temperature ratio of T2/T1 ~ 1.7 across the G region of the radio relic and no temperature jump across the H region. However, in both regions projection effects might have affected the measurements, thereby reducing the contrast.

Key words: galaxies: clusters: general / galaxies: clusters: individual: Abell 2256 / acceleration of particles

Appendix A is available in electronic form at http://www.aanda.org

© ESO, 2015

1. Introduction

A fraction of galaxy clusters exhibit diffuse Mpc-scale synchrotron emission (referred to as radio halos and radio relics) not related to any particular cluster galaxy (for reviews see Feretti et al. 2012; Brüggen et al. 2012). This emission manifests itself by the presence of relativistic electrons (~GeV) and weak magnetic fields (~μG) in the intracluster medium (ICM), together with the hot thermal plasma emitting X-rays. Radio halos permeate the central Mpc3 of galaxy clusters and the radio emission usually follows the roundish X-ray emission from the thermal gas. Radio relics are more irregularly shaped and are located at the clusters periphery. They are usually further subdivided into three classes: radio gischt, radio phoenices, and AGN relics (see Kempner et al. 2004), depending on their characteristics and proposed origin (as described below). The combination of the Mpc size of such sources and the relatively short radiative lifetime of the emitting electrons implies the need for some form of in situ production or (re-)acceleration of the electrons in all these sources, even though the underlying physical mechanisms are thought to be different for the different classes of sources. Moreover, these diffuse radio emitting regions are mostly found in unrelaxed clusters, suggesting that cluster mergers play a key role in producing them.

Radio gischt are large, extended arc-like sources, believed to be synchrotron emission from electrons accelerated or re-accelerated in merger or accretion shocks through diffusive shock acceleration (DSA, Fermi-I process; see Ensslin et al. 1998; Kang & Ryu 2011). A textbook example of such giant radio relic has been observed in the galaxy cluster CIZA J2242.8+5301 (van Weeren et al. 2010; Stroe et al. 2013). Radio phoenices are believed to be the result of the re-energization via adiabatic compression, triggered by shocks, of fossil plasma from switched-off AGN radio galaxies (Enßlin & Gopal-Krishna 2001; Enßlin & Brüggen 2002). The relativistic plasma of AGN origin had the time to age and without the re-energization would not longer be visible at the currently observable radio frequencies. An example of a radio phoenix has been found in the galaxy cluster A2443 (Cohen & Clarke 2011). AGN relics are indeed such fossil radio galaxies where the AGN switched off more recently and no re-energization occurred. The plasma is still emitting at observable radio frequencies, and it simply evolves passively until it becomes invisible in the radio window (Komissarov & Gubanov 1994).

Models and diagnostics

The proposed formation mechanisms differ in the predictions of the morphological and

spectral characteristics of the different classes of relics. DSA of both thermal and

pre-accelerated electrons, should produce larger and more peripheral structures, with strong

polarization, and pure power-law integrated synchrotron spectra (Brüggen et al. 2012). Fermi processes naturally predict an injection

power-law energy distribution for the accelerated electron population of the form1f(E) ∝ E−

δinj. From synchrotron theory, the

emission produced by this population of electrons is also described by a power law2,  (1)Emitting particles are naturally subject to

energy losses. These losses are governed by many physical factors such as the properties of

the magnetic field (see Kardashev 1962; Jaffe & Perola 1973; Komissarov & Gubanov 1994, for a description of the different models of

electron aging). The absence of any constant injection of new electrons would lead to a

cutoff in the high-energy region of the integrated spectrum, moving toward lower frequencies

in the course of time. The presence of constant injection of particles with the same energy

spectrum, on the other hand, would eventually mask the cutoff, leading instead to a break

with a change of 0.5 in the spectral index of the integrated emission (continuous injection

model, Kardashev 1962):

(1)Emitting particles are naturally subject to

energy losses. These losses are governed by many physical factors such as the properties of

the magnetic field (see Kardashev 1962; Jaffe & Perola 1973; Komissarov & Gubanov 1994, for a description of the different models of

electron aging). The absence of any constant injection of new electrons would lead to a

cutoff in the high-energy region of the integrated spectrum, moving toward lower frequencies

in the course of time. The presence of constant injection of particles with the same energy

spectrum, on the other hand, would eventually mask the cutoff, leading instead to a break

with a change of 0.5 in the spectral index of the integrated emission (continuous injection

model, Kardashev 1962):  (2)This condition translates, in case of DSA, in

the assumption that the properties of the shock remain unchanged (stationarity for the

shock). If the shock has been present in the ICM for a time exceeding the electron cooling

time, a single power law with spectral index αobs is expected for the integrated radio

spectrum (stationarity for the spectrum). The observed spectral indices reported in Table 4

of Feretti et al. (2012) for straight integrated

spectra range from 1.1 to 1.6. A gradient is expected in the spectral-index distribution

across the source, with the flattest values marking the position of the shock front where

the particle get accelerated, and the steepening showing the radiative losses as the

electrons are advected away from the shock. Such a gradient is clearly observed in the radio

relic in CIZA J2242.8+5301 (van Weeren et al. 2010;

Stroe et al. 2013).

(2)This condition translates, in case of DSA, in

the assumption that the properties of the shock remain unchanged (stationarity for the

shock). If the shock has been present in the ICM for a time exceeding the electron cooling

time, a single power law with spectral index αobs is expected for the integrated radio

spectrum (stationarity for the spectrum). The observed spectral indices reported in Table 4

of Feretti et al. (2012) for straight integrated

spectra range from 1.1 to 1.6. A gradient is expected in the spectral-index distribution

across the source, with the flattest values marking the position of the shock front where

the particle get accelerated, and the steepening showing the radiative losses as the

electrons are advected away from the shock. Such a gradient is clearly observed in the radio

relic in CIZA J2242.8+5301 (van Weeren et al. 2010;

Stroe et al. 2013).

In case of revival via adiabatic compression of old radio plasma left behind by radio galaxies and pushed towards the cluster outskirts by buoyancy, we expect instead more filamentary and smaller radio structures (< 50 kpc), again strongly polarized, but with steeper and curved integrated spectra due to the already aged population of electrons that are re-accelerated. In fact the adiabatic compression would just shift the already aged spectrum at high energies upward, without modifying the spectral slope. Even steeper spectra are expected in case of AGN relics. The average spectral indices reported in Table 4 of Feretti et al. (2012) for integrated spectra with measured steepening, range from 1.7 to 2.9.

With these ingredients, detailed studies of the integrated spectrum and of the spectral-index distribution across the sources, allow us to test the current models and study the shock properties in case of DSA. This is accomplished by observations made over a broad range of frequencies. However, an accurate measurement of the integrated spectra of radio relics is a difficult task. These sources usually contain a number of discrete sources, whose flux density needs to be carefully subtracted from the total diffuse emission. This requires high-resolution imaging at many frequencies using radio interferometers. However, increasing the observing frequencies, interferometers encounter the technical problem of the missing short spacings that makes them “blind” to very extended structures. On the other hand, single dishes are optimal to catch all the emission from a field but they lack angular resolution. Indeed, integrated spectra over a wide range of frequencies are available in the literature only for few of these objects (see Feretti et al. 2012).

An independent measure of the properties of shocks is provided by deep X-ray observations.

Through the measurements of temperature and/or pressure jumps at the location of the shock,

properties such as the shock Mach number M and the shock compression ratio C can be inferred (see review

by Brüggen et al. 2012). In the test particles

approximation3 of DSA, if the particle diffusion is

specified, the shock Mach number is the primary parameter that determines the efficiency of

the acceleration mechanism and the energy distribution of the particles at injection (Kang & Ryu 2010). In this case, a simple direct

relation between the shock Mach number M and the injection index δinj of the energy

electrons distribution exists:  (3)However, radio relics are usually observed in

the outskirts of clusters where the very low density of electrons (ne< 10-4

cm-3) make the detection of shocks in the X-ray very

challenging (Akamatsu & Kawahara 2013). Indeed, a

few clear X-ray shock detections are known in the literature (see review by Brüggen et al. 2012). In conclusion, multifrequency radio

measurements, combined with deep X-ray observations, allow a search for and a proper study

of these shocks to test the shock-origin model for relics.

(3)However, radio relics are usually observed in

the outskirts of clusters where the very low density of electrons (ne< 10-4

cm-3) make the detection of shocks in the X-ray very

challenging (Akamatsu & Kawahara 2013). Indeed, a

few clear X-ray shock detections are known in the literature (see review by Brüggen et al. 2012). In conclusion, multifrequency radio

measurements, combined with deep X-ray observations, allow a search for and a proper study

of these shocks to test the shock-origin model for relics.

The case of Abell 2256

One of the most intriguing clusters hosting both a radio relic and a radio halo is the

galaxy cluster A 2256 (z =

0.058). The radio relic emission in this cluster differs in many aspects

from the textbook examples of radio gischt in merging clusters, e.g., in CIZA J2242.8+5301

(van Weeren et al. 2010) and in A3376 (Bagchi et al. 2006). The A 2256 relic emission is, indeed,

dominated by a complex filamentary structure as confirmed by new wide-band VLA observations

published during the reviewing process of the present paper (Owen et al. 2014). It is moreover characterized by an unusually large aspect

ratio, being nearly as wide as it is long, and by an unusual proximity to the cluster center

respect to the majority of giant relics known in the literature. It also shows all typical

signatures of a merging cluster system although its dynamical state is not yet completely

understood. This cluster has been the first observed with LOFAR at very low frequencies

(20−63 MHz) by van Weeren et al. (2012). They collected data up to 1400

MHz and found a radio-integrated spectrum for the relic that can be described by a power law

with an unusual flat spectral index  . The occurrence of similar flat spectral

indeces have been reported by Kale & Dwarakanath

(2010) in the frequency range 150−1369 MHz. Assuming stationary conditions in the test-particle case of

DSA, this would require an injection spectral index which is not consistent with the

flattest possible injection spectral index from DSA. Indeed, a direct consequence of the

test-particle approach to DSA is that in the limit of strong shocks (M ≫ 1) the particle index

δinj approaches an asymptotic value of 2.

This means that particle energy distribution produced by test-particle DSA cannot be flatter

than 2 (it must be δinj ≳ 2). As a consequence the

synchrotron spectra at injection cannot be flatter than 0.5 (αinj ≳ 0.5). So,

we should not observe relics with spectra αobs ≲ 1. The flat spectrum could be

reconciled with shock acceleration if the shock has been produced very recently

(~ 0.1 Gyr ago) and

stationarity has not been reached yet. In this case a steepening of the integrated spectrum

is expected at frequencies

. The occurrence of similar flat spectral

indeces have been reported by Kale & Dwarakanath

(2010) in the frequency range 150−1369 MHz. Assuming stationary conditions in the test-particle case of

DSA, this would require an injection spectral index which is not consistent with the

flattest possible injection spectral index from DSA. Indeed, a direct consequence of the

test-particle approach to DSA is that in the limit of strong shocks (M ≫ 1) the particle index

δinj approaches an asymptotic value of 2.

This means that particle energy distribution produced by test-particle DSA cannot be flatter

than 2 (it must be δinj ≳ 2). As a consequence the

synchrotron spectra at injection cannot be flatter than 0.5 (αinj ≳ 0.5). So,

we should not observe relics with spectra αobs ≲ 1. The flat spectrum could be

reconciled with shock acceleration if the shock has been produced very recently

(~ 0.1 Gyr ago) and

stationarity has not been reached yet. In this case a steepening of the integrated spectrum

is expected at frequencies  2000

MHz.

2000

MHz.

In this paper we present new high-frequency radio observations (Sect. 2) of A 2256 at 2273, 2640 and 4850 MHz MHz performed both with an interferometer (the Westerbork Synthesis Radio Telescope, WSRT) and a single dish (the Effelsberg 100 m Telescope), complemented by X-ray observations (Sect. 3) performed with the Suzaku and XMM-Newton satellites. In Sect. 4 we present a new determination of the relic radio spectrum over the widest sampled frequency range collected so far for this kind of object (63 MHz−10 450 MHz)4. In Sect. 5 we show the ICM temperature in regions across the radio relic emission. In Sect. 6 we consider the effect of the thermal Sunyaev-Zeldovich (SZ) decrement on our flux density measurements at high frequencies. Discussion and conclusions are presented in Sects. 7 and 8.

We adopted the cosmological parameters H0 = 71 km s-1 Mpc-1, ΩΛ = 0.73 and Ωm = 0.27 (Bennett et al. 2003), which provide a linear scale of 1.13 kpc arcsec-1 at the redshift of A 2256.

2. Radio observations and data reduction

A 2256 was observed with the WSRT at 2273 MHz and with the Effelsberg 100 m Telescope at 2604 and 4850 MHz.

In this section we present the observations and the main steps of the calibration and image-making process. All the observations include full polarization information. In this paper we focus on the total intensity properties of the cluster. We postpone a detailed local analysis based on polarization properties and spectral index maps to a forthcoming paper (Trasatti et al., in prep.).

2.1. WSRT observations

For this project we choose for the WSRT the maxi-short configuration which has optimized imaging performance for very extended sources. The receiver covers the frequency range from 2193 MHz to 2353 MHz with eight contiguous intermediate frequencies (IFs) of 20 MHz width each; the resulting central frequency is 2273 MHz and the total bandwidth is 160 MHz. We are potentially sensitive to emissions on scale up to ~13′ with a full resolution of ~9′′.

The main limiting factor of the field of view is the effect of the primary beam attenuation. For the WSRT this can be described by the function cos6(c·ν·r) where r is the distance from the pointing center in degrees, ν is the observing frequency in GHz and the constant c = 68 is, to first order, wavelength independent at GHz frequencies (declining to c = 66 at 325 MHz and c = 63 at 4995 MHz). The resulting field of view at 2273 MHz is 0.37°. In order to image a field big enough to recover the extended emission in A 2256, the observations were carried out in the mosaic mode. Three different pointing centers were chosen (details in Table 1). In order to have a good uv coverage for each pointing, the observations were performed switching the telescope from one pointing to another every five minutes, having four hours of observations for each pointing for a total of twelve hours for the entire cluster. The observations were carried out on the 25th January 2003. The excellent phase stability of the system allow us to observe primary calibrators only at the beginning and the end of an observation to calibrate WSRT data. 3C 286 and 3C 48 were observed for this purpose.

WSRT observational parameters.

Effelsberg observational parameters.

Flagging, calibration, imaging and self-calibration were performed with the AIPS (Astronomical Image Processing System) package, with standard procedures following the guideline provided on the ASTRON web-page5. All the antennas were successful, with some occasional RFI, flagged out in the early stages of data calibration. 3C 286 was used as the main flux density calibrator using the Baars et al. (1977) scale (task SETJY in AIPS), which provides flux densities ranging from 11.74 Jy in the first IF to 11.39 Jy in the eighth IF. The three pointings were imaged and self-calibrated separately. For each pointing we performed three phase-only cycles of self-calibration, followed by a final amplitude and phase self-calibration cycle. The diffuse emission flux was included in the model for the self-calibration. A multiresolution clean was performed within the IMAGR task in AIPS to better reconstruct the complex diffuse emission present in the cluster in the final images of the pointings. Images of the Stokes parameter I, U and Q were obtained for each pointing and were then combined together (separately for I, U and Q) and corrected for the primary beam attenuation with the FLATN task in AIPS providing a central region with a uniform σ noise distribution of ~0.027 mJy/beam. The primary beam correction determines an increase of the noise in the outer regions.

2.2. EFFELSBERG observations

Part of the observations were performed with the Effelsberg 100 m Telescope. We used the 11 cm (=2640 MHz) and 6 cm (=4850 MHz) receivers. Single-dish observations do not suffer from the zero-spacing problem, and can trace large scale features, although with modest resolution.

The data reduction of Effelsberg data was performed with the NOD2 software package, following the standard procedures provided on the MPIfR web-page6. The raw images of both A 2256 and the calibrators were partly processed using dedicated pipelines available for each receiver. The default strategy to calibrate Effelsberg data is to observe primary calibrators during the session and then use automatic 2D Gauss fit pipelines to calculate the factor to scale the final image converting it from mapunit/beam to Jy/beam (task RESCALE in AIPS).

2.2.1. Observations at 2640 MHz

The Effelsberg 11 cm receiver is a single-horn system equipped with a polarimeter with

eight small-band frequency channels, each 10 MHz wide, covering the frequency range

2600−2680 MHz, plus one

broad-band channel, 80 MHz wide, over the same frequency range. The resulting central

frequency is 2640 MHz and the total bandwidth is 80 MHz. The resolution of the

observation is 4 .

.

To map the A 2256 field we used the mapping mode, which consist in rastering the field of interest by moving the telescope, e.g., along longitude (l), back and forth, each subscan shifted in latitude (b) with respect to the other. At centimeter wavelengths atmospheric effects (e.g., passing clouds) introduce additional emission/absorption while scanning, leaving a stripy pattern along the scanning direction (the so-called scanning effects). Rastering the same field along two perpendicular directions (both along longitude and latitude) helps in efficiently suppressing these patterns, leading to a sensitive image of the region (Emerson & Graeve 1988). This technique, called basket-weaving technique, helps also in setting the zero-base level. The details of the observations are summarized in Table 2. For each coverage of the field, the receiver provides four images (R, L, U, Q) for each of the nine channels. As circular polarization is generally very weak, the images in R and L are very similar and can be averaged in the later steps of data reduction providing the total intensity image.

We performed a total of 14 coverages in the longitude direction and 15 coverages in the latitude direction; due to RFI (Radio Frequency Interference) and pointing problems we had to discard a small portion of the data. The time required to complete one coverage is ~17 min in both direction, so we have a total observing time on source of 8.2 h. The observations were carried out in the night between the 15th and 16 August 2012. 3C 286 and 3C 48 were used as absolute flux density calibrators using the Baars et al. (1977) scale that provide flux densities at 2640 MHz of 10.65 Jy and 9.38 Jy respectively for the two calibrators.

2.2.2. Observations at 4850 MHz

The Effelsberg 6 cm receiver is a double-horn system, with the two feeds fixed in the

secondary focus with a separation of 6 cm, each with one broad-band (500 MHz) frequency

channel in the range 4600−5100 MHz. The resulting central frequency is 4850 MHz and the total

bandwidth is 500 MHz. The resolution of the observation is

2 .

.

Multihorn systems use a different technique to overcome the scanning effect problem. The scanning is done in an azimuth-elevation coordinate system, and must be done only in azimuth direction so that all horns will cover the same sky area subsequently. At any instant each feed receives the emission from a different part of the sky but they are affected by the same atmospheric effects, which then cancel out taking the difference signal between the two feeds (Emerson et al. 1979). Similarly to the 11 cm receiver, data in (R, L, U, Q) are provided for each of the two horn.

We performed a total of 25 coverages of the A 2256 field, 15 during the night between the 22nd and the 23rd of June and 10 on the 26th of June 2011. Due to RFI problems only 22 coverages could be used.

For the calibration we observed 3C 286 and NGC 7027 during the session. The flux densities used for the two calibrators are 7.44 Jy (from Baars et al. 1977) and 5.48 Jy (from Peng et al. 2000) respectively.

3. X-ray observations and data reduction

In this section we present the X-ray observations of A 2256 performed with Suzaku and XMM-Newton and the main steps of data reduction.

Suzaku observed the radio relic region in A 2256 (OBSID: 801061010, Tamura et al. 2011) with an exposure time of 95.2 ks. The satellite X-ray Imaging Spectrometer (XIS: Koyama et al. 2007) has a very low detector background, which allows us to investigate weak X-ray emission targets such as cluster outskirts (see Reiprich et al. 2013, for a review). The XIS was operated in the normal clocking, 3 × 3 and 5 × 5 mode. To increase the signal-to-noise ratio we filtered the dataset using a geomagnetic cosmic-ray cut-off rigidity (COR) >8 GV. The filtered exposure time is 89.2 ks. The data were processed using standard Suzaku pipelines (see Akamatsu et al. 2012, for more details).

We complemented Suzaku observations with XMM-Newton observations retrieved from the archive (OBSID: 0141380101 and OBSID:0141380201) and reprocessed with SAS v11.0.1. The data were heavly affected by soft proton flares. The data were cleaned for periods of high background due to soft proton flares with a two stage filtering process (see Lovisari et al. 2009, 2011, for more details on the cleaning process). In this screening process bad pixels have been excluded and only event patterns 0−12 for the MOS detectors and 0 for the pn detector were considered. The filtered exposure time is ~19 ks for MOS1, ~20 ks for MOS2 and ~9 ks for pn.

For both satellites the background emission can be described as the sum of a particle background component and a sky background component. The former is produced by the interaction of high-energy particles with the detectors. The latter can be subdivided into at least two thermal components, one unabsorbed due to the Local Hot Bubble (LHB: kT ~ 0.08 keV) and one absorbed due to the Milky Way Halo (MWH: kT ~ 0.3 keV), and a power-law component due to the Cosmic X-ray Background (CXB: Γ = 1.41).

The particle background has been modeled and subtracted from the data of both satellites before the spectral fits presented in Sect. 5.1. For the Suzaku observations its contribution has been estimated from the Night-Earth database with the xisnxbgen FTOOLS (Tawa et al. 2008). For XMM-Newton the particle component spectra have been extracted from the filter wheel closed (FWC) observations and renormalized by using the out-of-field-of-view events. These spectra were supplied as background spectra to the XSPEC fitting routine.

Unlike the particle background, the sky background was not subtracted from the data but its different components were modeled together with the ICM emission during the spectral fitting. To fix the model parameters for the different components in Suzaku observations, we used spectra extracted from a 1 degree offset observation performed with the satellite (PI: Kawaharada, OBSID: 807025010). For XMM-Newton data, we followed the method presented in Snowden et al. (2008) in which the different components are estimated using a spectrum extracted from ROSAT data in an annulus beyond the virial radius of the cluster. The offset spectra were fitted with a sky background model considering the LHB, MWH and CXB components. In the fitting, we fixed the temperature of the LHB component to 0.08 keV. Abundance (Anders & Grevesse 1989) and redshift of LHB and MWH were fixed to 1 and 0, respectively. The temperature of the MWH determined in the fit is 0.21 ± 0.03 keV. We also checked for the possibility of an additional “hot foreground” component with kT ~ 0.6−0.8 keV (Simionescu et al. 2010) adding another thermal component to the background model described above. However, the intensity of this additional component resulted not significant in the offset field and was not included in the background modeling.

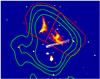

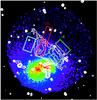

|

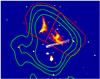

Fig. 1 WSRT 2273 MHz total intensity radio image. Contours are drawn at [1, 2, 4, 8]

× 3σ, with 3σ = 8 ×

10-5 Jy/beam and the color scale starts at the same

level. The beam size is |

4. Radio analysis and results

4.1. Radio images

4.1.1. WSRT image

In Fig. 1 we present the 2273 MHz total intensity

WSRT image of the central region of A 2256. The image has been produced with natural

weighting of the visibilities in the range [umin − umax ] = [ 260−21

035 λ]. The shortest spatial frequency sampled

umin determines the largest spatial

scale recovered by this observations  . The image has been corrected for the

primary beam attenuation that determines an increase of the noise in the edge of the

image. The high resolution (

. The image has been corrected for the

primary beam attenuation that determines an increase of the noise in the edge of the

image. The high resolution ( ) allowed us to analyze the

substructures of the diffuse relic emission in detail. The map shows several of the

well-known radio features present in the cluster (notation from Bridle et al. 1979; Rottgering et al.

1994): the radio relic emission (sources G and H), the head-tail sources A, B,

C and I, the complex source F (here resolved in the three components F1, F2 and F3), as

well as many other discrete sources, some of which labeled in this paper as I2, I3, K2,

G2, J2. The radio halo emission present in the center of the cluster around source D

(Clarke & Ensslin 2006) is completely

filtered out due to a combination of effects: its low surface brightness at this

frequency, combined with the lack of sampled short spacings in the WSRT observations,

that determines the loss of the very extended weak emission.

) allowed us to analyze the

substructures of the diffuse relic emission in detail. The map shows several of the

well-known radio features present in the cluster (notation from Bridle et al. 1979; Rottgering et al.

1994): the radio relic emission (sources G and H), the head-tail sources A, B,

C and I, the complex source F (here resolved in the three components F1, F2 and F3), as

well as many other discrete sources, some of which labeled in this paper as I2, I3, K2,

G2, J2. The radio halo emission present in the center of the cluster around source D

(Clarke & Ensslin 2006) is completely

filtered out due to a combination of effects: its low surface brightness at this

frequency, combined with the lack of sampled short spacings in the WSRT observations,

that determines the loss of the very extended weak emission.

The relic emission exhibits two regions of enhanced surface brightness: a well-defined

arc-like region (G region) in the northern part, and a less defined region (H region) in

the western part (see Fig. 1). The two regions are

connected by a bridge of lower brightness emission. At full resolution the entire relic

emission covers an area of about  . The size reported by Clarke & Ensslin (2006) at 1.4 GHz and at a

resolution of 52′′ × 45′′ is

. The size reported by Clarke & Ensslin (2006) at 1.4 GHz and at a

resolution of 52′′ × 45′′ is

. Convolving our WSRT image to the same

resolution we obtain a similar angular size (not shown). Nevertheless, as we might be

anyway missing some of the flux on the most extended scales, we do not use this image

for the computation of the relic integrated spectrum.

. Convolving our WSRT image to the same

resolution we obtain a similar angular size (not shown). Nevertheless, as we might be

anyway missing some of the flux on the most extended scales, we do not use this image

for the computation of the relic integrated spectrum.

4.1.2. EFFELSBERG images

In Fig. 2 we show the 2640 MHz (left panel) and 4850 MHz (right panel) Effelsberg images of A 2256. In both images, the diffuse emission from the relic is mixed up with the emission from the more compact sources present in the field due to the low resolution of the observations. In the 2640 MHz image the relic emission is blended with the emission from the A+B+C complex and from source F. At 4850 MHz it is easier to separate the relic emission from the emission of the A+B complex, but still part of the tail of source C is inevitably superimposed on the western part of the relic. Moreover, Brentjens (2008) derived a spectrum α = 1.5 ± 0.2 for the radio halo between 351 and 1369 MHz. If there is no steepening in the spectrum of the halo, we expect a flux density of ~37 mJy at 2640 MHz and a flux density of ~15 mJy at 4850 MHz. Since a single dish is sensitive to all the emission in the field, its emission is smoothed with the other sources in our Effelsberg images if the halo spectrum keeps straight at these frequencies. Constraining the halo spectrum at high frequencies would require a dedicated careful analysis that is beyond the aims of this paper.

4.2. Spectral analysis

For the spectral analysis of the radio relic in A 2256 we combined our high-frequency observations with images obtained at other frequencies provided by the authors: the 351 MHz WSRT image (Brentjens 2008), the 1369 MHz VLA C and D configuration images7 (Clarke & Ensslin 2006) and the Effelsberg 10 450 MHz image (Thierbach 2000). We moreover got information on the flux densities in the LOFAR image at 63 MHz published by van Weeren et al. (2012) by the author. All the different images were calibrated according to the flux scale of Baars et al. (1977) or to its extension to lower frequencies (below 408 MHz; Perley & Taylor 1999)8. In this way we were able to cover the widest range of frequencies (63 MHz−10.45 GHz) used so far for the determination of the spectrum of a radio relic.

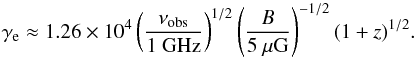

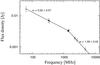

|

Fig. 2 Effelsberg total intensity radio images. Left panel: Effelsberg

2640 MHz total intensity radio image in color scale and black contours drawn at [–1,

1, 2, 4, 8, 16] ×

3σ,

with 3σ = 4 ×

10-3 Jy/beam. The beam size is

|

We estimated the uncertainties σS on the flux density

measurements S with the following formula

(4)where

(4)where

-

is the error due to the image noise,

with σ

being the image noise level (quoted in the image’s captions) and Nbeam the

number of beams covered by the source;

is the error due to the image noise,

with σ

being the image noise level (quoted in the image’s captions) and Nbeam the

number of beams covered by the source; -

σcal = Ecal × S is the error due to calibration uncertainties, determined in turn by two factors: the accuracy of the absolute flux density scale adopted (ϵscale) and the uncertainties related to the application of such scale to our data (the calibration method, ϵcal); being these two factors uncorrelated we used

.

.

The spectral data provided by Baars et al. (1977) for the flux density calibrators have an absolute uncertainty of 5%. For the calibration of the Effelsberg images we performed four coverages of 3C 286 and three coverages of 3C 48 at 2640 MHz and four coverages of 3C 286 and three coverages of NGC 7027 at 4850 MHz. A Gaussian fit of the image of a calibrator provides its flux density in map unit. A comparison of this value with the known calibrator flux density allows us to calculate the factor to translate map unit in physical unit. The slightly different factors deriving from the different coverages of the calibrators were finally averaged, separately at the two frequencies. The standard deviation of these values (at the two frequencies) was used as the term ϵcal. For the WSRT data we used, instead, the dispersion of antenna gains. This translates into ϵcal values of 1.6% for the Effelsberg 11 cm data, of 1.2% for the Effelsberg 6 cm data and of 2% for the WSRT 13 cm data. Combining this with the uncertainties on the Baars et al. (1977) scale, we end up with Ecal(11 cm) = 5.3%, Ecal(6 cm) = 5.2% and Ecal(13 cm) = 5.4%. For the other images from the literature we assumed a similar value Ecal = 6%. It should be noted that the self-calibration process might affect the measured flux densities on interferometric images. The uncertainties are therefore possibly larger than estimated here.

Where not otherwise specified, we estimated the uncertainties σf on the quantities

f

calculated from measured quantities (e.g., spectral indices and extrapolated flux

densities of discrete sources) applying the standard error propagation formula. The

spectra of the total cluster, relic+sources, relic, G and H regions presented in the next

sections have been determined calculating the flux densities at different frequencies on

images convolved to the same lowest resolution available

( ) and using the same regions for the

integration. The errors associated to the spectral indices are the errors from the fits of

the data taking into account the uncertainties in the flux density measurements.

) and using the same regions for the

integration. The errors associated to the spectral indices are the errors from the fits of

the data taking into account the uncertainties in the flux density measurements.

All the spectra, including those of the discrete sources embedded in the relic emission, are plotted over the same fixed x-axis range (frequency range 40−14 000 MHz) for easy comparison.

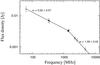

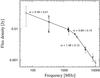

4.2.1. Total cluster emission

We first considered the integrated radio flux density of the entire cluster (halo, relic and discrete sources combined) measuring the flux density in the circular region centered at J2000 position α = 17 03 45δ = + 78 43 00 with 10′ radius, as described by Brentjens (2008). The cluster radius was determined by Brentjens (2008) as the one at which the derivative of the integrated flux within the circle respect to the radius of the circle settles to a constant value. The measured flux densities at 351, 1369 (D configuration), 2640, 4850 and 10 450 MHz are summarized in Table 4. The total cluster radio emission between 351 and 10 450 MHz can be modeled by a single power law with spectral index α = 1.01 ± 0.02 (Fig. 10a).

Brentjens (2008) modeled the cluster flux density as the sum of two spectral components, one due to the halo and the other due to the relic and discrete sources combined. He showed that the second term becomes dominant at frequencies above 100 MHz. Being the radio relic the dominant contributor to the flux density at high frequency, its spectrum at the same frequencies cannot be flatter than the total cluster emission spectrum. This shows qualitatively that at high frequencies the relic spectrum does not keep the 0.85 slope observed at low frequency by van Weeren et al. (2012). In Sect. 4.2.3 we will quantify this steepening.

Properties of the radio sources embedded in the radio relic emission.

4.2.2. Discrete sources

|

Fig. 3 Regions used for the spectra computation. The red region marks the region considered for the relic spectrum computation. The total region is further subdivided into regions G and H. In color scale the WSRT high-resolution image with the green contours from the 2640 MHz Effelsberg image overplotted. The white region mark the C source. |

|

Fig. 4 Integrated radio spectrum of source C. Filled circles are measured flux densities while open circles are extrapolated flux densities. The black solid line is the spectrum of the entire source; the red dashed line is the source’s head spectrum; the blue dotted-dashed line is the spectrum of the tail. See text for more details. |

|

Fig. 5 Integrated radio spectrum of source K. Filled circles are measured flux densities while open circles are extrapolated flux densities. |

|

Fig. 6 Integrated radio spectrum of source J. Filled circles are measured flux densities while open circles are extrapolated flux densities. |

|

Fig. 7 Integrated radio spectrum of source I. Filled circles are measured flux densities while open circles are extrapolated flux densities. |

|

Fig. 8 Integrated radio spectrum of source I2. Filled circles are measured flux densities while open circles are extrapolated flux densities. |

|

Fig. 9 Integrated radio spectra of the different components in the relic region shown in

Fig. 3. In black we show the flux densities

and spectra of the emission from the entire region (relic+sources). The dashed

( |

Figure 3 shows the area selected for measuring the radio relic flux densities. From the high-resolution image it is possible to see which are the discrete sources included in such area: the tail of source C Ctail, K, J, I, G2, K2, J2, I2 and I3. To estimate the flux density from the discrete sources that needs to be subtracted from the total emission, we produced two images at 1369 MHz (VLA C configuration) and 2273 MHz (WSRT) using the same uv-range (262−15 460 λ), pixel-size and restoring beam and we calculated the spectral index of the discrete sources embedded in the relic emission between these two frequencies. Moreover we measured the flux density at 10 450 MHz for the different components of source C and for the sources J and I2. Where available, we combined our data with data collected from the literature and we modeled the integrated spectra of the discrete sources over the frequency range 63−10 450 MHz. All the measured and extrapolated flux densities, as well as the spectral indices of the source C components with references are listed in Table 3. Details on the flux densities derivation are given in Appendix A. The spectra of the sources C, K, J, I and I2, for which more than two flux density measurements were available, are plotted individually in figures from 4 to 8 and all together in red in Fig. 9. For the sources K2, J2, I3 and G2 only our flux density measurements at 1369 and 2273 MHz were available and we simply assumed straight spectra. This assumption may lead to a slight over estimate of the flux densities at both low and high frequencies (as for standard radio source synchrotron spectra we expect a flattening at low frequencies and a steepening at high frequencies). On the other hand, they are weak sources and their flux densities are not crucial for the relic spectrum determination. Their spectra are plotted in blue in Fig. 9. This figure shows the spectra of the discrete sources included in the region selected, compared to the total flux density in the region (relic+sources). The main flux density contribution among the discrete sources in the relic area come from the tail of source C, especially at lower frequencies. The source appears noticeably narrow and long at high resolution, ~410″ in total in our 2273 MHz image (see Fig. 3). The published flux densities in the literature refer to the source as a whole. We modeled the source distinguishing between the head (long 76″) and the tail as we are interested only on the contribution from the latter. In Fig. 4 the spectrum over the range 63−10 450 MHz is plotted for the entire source, the head, and the tail. As common among head-tail sources, the head is flatter than the tail and the spectrum steepens at high frequency for both components. At lower frequencies, the tail contains almost all the emission of the sources. At high frequencies the electrons in the tail are older while the head is more clearly visible.

Sources J and I2 have an inverted-spectrum. Their spectra (plotted in Figs. 6 and 8) have a convex shape at GHz frequencies, typical of inverted-spectrum sources, and are likely young radio objects.

4.2.3. Radio relic spectrum

To avoid that resolution effects at different frequencies may alter the determination

of the relic integrated spectrum, we convolved all the images used for the flux

densities computation to the same resolution of  . At such low resolution, it is not

easy to identify the region where to measure the relic flux density. We adopted the

following strategy: we first computed the relic flux density from the 4850 MHz image at

full resolution, where it is easier to separate the relic emission from the complex A+B

emission. We then choose the relic region in the 4850 MHz image convolved to the

resolution of

. At such low resolution, it is not

easy to identify the region where to measure the relic flux density. We adopted the

following strategy: we first computed the relic flux density from the 4850 MHz image at

full resolution, where it is easier to separate the relic emission from the complex A+B

emission. We then choose the relic region in the 4850 MHz image convolved to the

resolution of  , matching the flux density measured

at full resolution at the same frequency. The selected area is shown in Fig. 3. The region is further divided into two regions of

enhanced radio brightness (regions G and H) discussed in the next section. As discussed

in the previous section, this region include the radio relic and sources

Ctail, K, J, I,

G2, K2, J2, I2 and I3.

, matching the flux density measured

at full resolution at the same frequency. The selected area is shown in Fig. 3. The region is further divided into two regions of

enhanced radio brightness (regions G and H) discussed in the next section. As discussed

in the previous section, this region include the radio relic and sources

Ctail, K, J, I,

G2, K2, J2, I2 and I3.

Total cluster flux densities.

We first considered the total emission from the region. Although the flux density

measurements of the relic+sources in the range 63−10 450 MHz can be fitted with a single

power law with  (Fig. 9), hints of a steepening at frequencies >1400 MHz are present. A separate

fit of the spectra between 63 and 1369 MHz and between 1369 and 10 450 MHz shows indeed

that these two frequency ranges are best represented by two different power laws, with

(Fig. 9), hints of a steepening at frequencies >1400 MHz are present. A separate

fit of the spectra between 63 and 1369 MHz and between 1369 and 10 450 MHz shows indeed

that these two frequency ranges are best represented by two different power laws, with

and

and

(Fig. 9). All the fits are plotted over the entire range 63−10 450 MHz to highlight differences.

Since the relic is the major contributor in the region both at low and high frequency,

this suggests that a steepening might be present in its spectrum as well. Moreover the

relic spectrum between 63 and 1369 MHz must be

(Fig. 9). All the fits are plotted over the entire range 63−10 450 MHz to highlight differences.

Since the relic is the major contributor in the region both at low and high frequency,

this suggests that a steepening might be present in its spectrum as well. Moreover the

relic spectrum between 63 and 1369 MHz must be  as it cannot be steeper than the

relic+sources spectrum. Similarly it must be

as it cannot be steeper than the

relic+sources spectrum. Similarly it must be  as it cannot be flatter than the

relic+sources spectrum. Indeed, after discrete sources subtraction we find that,

although the relic spectrum between 63 and 10 450 MHz is not inconsistent with a single

power law with

as it cannot be flatter than the

relic+sources spectrum. Indeed, after discrete sources subtraction we find that,

although the relic spectrum between 63 and 10 450 MHz is not inconsistent with a single

power law with  , it is best represented by two different

power laws, with

, it is best represented by two different

power laws, with  and

and

(Fig. 10b). This is supported by a lower

values of the reduced χ2 in the case of the double power law

(

(Fig. 10b). This is supported by a lower

values of the reduced χ2 in the case of the double power law

( ) respect to the single power law

(

) respect to the single power law

( ). The measured relic flux densities

(before and after discrete sources subtraction) are summarized in Table 5. The flux densities measured at 63 MHz, 351 MHz and

1369 MHz are in agreement within the error bars with the already published flux

densities at the same frequencies. The low-frequency spectral index is in agreement with

what was found by van Weeren et al. (2012).

). The measured relic flux densities

(before and after discrete sources subtraction) are summarized in Table 5. The flux densities measured at 63 MHz, 351 MHz and

1369 MHz are in agreement within the error bars with the already published flux

densities at the same frequencies. The low-frequency spectral index is in agreement with

what was found by van Weeren et al. (2012).

Clarke & Ensslin (2006) report a relic mean spectral index between 1369 MHz and 1703 MHz of 1.2. However, this value has a big uncertainty (not quoted by author) since it is derived as the mean value from the spectral index image between two very close frequencies. We cannot therefore exclude it is in agreement with our value. Moreover, the very recent JVLA observations by Owen et al. (2014) reports for the relic an overall intensity weighted spectral index in the L-band of ~0.94, in agreement with our finding.

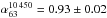

4.2.4. Regions G and H

Our high-resolution image shows that the relic can be divided into two separate parts:

regions G and H in Fig. 3. The cases of double

relics in the same cluster are getting more and more common since the first discovery of

two almost symmetric relics located on opposite sides in A3667. Since then, several

other double relics systems have been found (see Feretti et al. 2012). We have

investigated the possibility that the two different parts have different properties

fitting the spectra in the frequency range 351−10 450 MHz, separately. After discrete sources subtraction, the

flux densities of region G can be fitted with a single power law with a spectral index

of  (Fig. 10c). For homogeneity with the

radio relic analysis, we performed a separate fit of the spectra between 351 and 1369

MHz and between 1369 and 10 450 MHz. We find

(Fig. 10c). For homogeneity with the

radio relic analysis, we performed a separate fit of the spectra between 351 and 1369

MHz and between 1369 and 10 450 MHz. We find  and

and

(Fig. 10c).

(Fig. 10c).

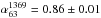

For the H region the flux densities can be modeled with a single power law with

spectral index  or with a double law with the same slope

as the G region at low frequency

or with a double law with the same slope

as the G region at low frequency  and a bit flatter spectra respect the G

region at high frequency

and a bit flatter spectra respect the G

region at high frequency  (Fig. 10d).

(Fig. 10d).

The measured flux densities before and after discrete sources subtraction are listed in Tables 6 and 7, while the spectra are plotted in Figs. 10c and 10d.

|

Fig. 10 Integrated radio spectra. The red dashed and blue dot-dashed lines are a double power-law fit to the data while the solid black line is the single power-law fit. In panel b) the green crosses are the upper limits to the radio relic flux taking into account the SZ effect. See text for more details. |

Radio relic flux densities.

Region G flux densities.

Region H flux densities.

Observed synchrotron spectral indices of the different components.

5. X-ray analysis and results

5.1. ICM temperature

In the course of a merger, a significant portion of the energy involved is dissipated by

shocks and turbulence leading eventually to the heating of the ICM gas. As mentioned in

the Introduction, in the test particle regime of DSA theory the shock structure is

determined by the canonical shock jump conditions (Rankine-Hugoniot). Applying these

conditions, assuming the ratio of specific heats as 5/3, the expected ratio between the

postshock and preshock temperatures, respectively T2 and

T1, is related to the shock Mach number

through the following relation:  (5)We extracted the ICM temperature in different

regions across the radio relic corresponding to the rectangular areas shown in Fig. 11. The observed spectra were assumed to consist of thin

thermal plasma emission from the ICM, plus the total background contamination described in

Sect. 3. The emission from the ICM was modeled with

an additional absorbed thermal component in the total model (ICM+background). For the

Suzaku analysis, to generate the auxiliary response files (ARF), we

used an image constructed using a β-model (β = 0.816, rc =

5.64′ from Markevitch & Vikhlinin

1997) as input for the xissimarfgen. For XMM-Newton data,

we fitted the spectra in the 0.5−8 keV energy range, excluding the 1.4−1.6 keV band due to the strong

contamination from the Al line in all three detectors. Because of the low number of counts

in the XMM-Newton spectra of region r1, r2 and r3, we kept the

metallicity values in the fit frozen to the value obtained with the Suzaku

analysis, which are better constrained9.

Temperatures and normalizations of the thermal components were allowed to vary in the fit.

(5)We extracted the ICM temperature in different

regions across the radio relic corresponding to the rectangular areas shown in Fig. 11. The observed spectra were assumed to consist of thin

thermal plasma emission from the ICM, plus the total background contamination described in

Sect. 3. The emission from the ICM was modeled with

an additional absorbed thermal component in the total model (ICM+background). For the

Suzaku analysis, to generate the auxiliary response files (ARF), we

used an image constructed using a β-model (β = 0.816, rc =

5.64′ from Markevitch & Vikhlinin

1997) as input for the xissimarfgen. For XMM-Newton data,

we fitted the spectra in the 0.5−8 keV energy range, excluding the 1.4−1.6 keV band due to the strong

contamination from the Al line in all three detectors. Because of the low number of counts

in the XMM-Newton spectra of region r1, r2 and r3, we kept the

metallicity values in the fit frozen to the value obtained with the Suzaku

analysis, which are better constrained9.

Temperatures and normalizations of the thermal components were allowed to vary in the fit.

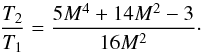

We observe a temperature drop across the G region of the radio relic, with the

temperature jumping from 8.45 keV in the region r2 (on the relic) to

4.95

keV in the region r2 (on the relic) to

4.95 keV in the region r3 (outside the outer

edge of the relic). XMM-Newton measurements in the same regions provide

consistent temperatures although with bigger errors. This is in agreement with Sun et al. (2002) that found a hot region

(~9 KeV) in positional

coincidence with the G lobe of the radio relic. Radio relics are usually associated to

outgoing merger shocks that travels from the core of a merging event outwardly towards the

periphery of the clusters. If we apply such scenario to A 2256, connecting the radio relic

emission to a shock front propagating outwardly in the north-western direction across the

G region of the radio relic, we can consider r2 as the post-shock region and r3 as the

preshock region. In this case we have a temperature ratio T2/T1

= 1.7. It is important to notice that this estimate is impacted by the

angle of the shock front to the line of sight. If the shock is not in the plane of the

sky, as it is likely the case for A 2256, projected mixing of shocked hot gas with cool

gas will reduce the apparent temperature of the shocked gas and increase the apparent

temperature of the cool gas, basically dropping the temperature ratio.

keV in the region r3 (outside the outer

edge of the relic). XMM-Newton measurements in the same regions provide

consistent temperatures although with bigger errors. This is in agreement with Sun et al. (2002) that found a hot region

(~9 KeV) in positional

coincidence with the G lobe of the radio relic. Radio relics are usually associated to

outgoing merger shocks that travels from the core of a merging event outwardly towards the

periphery of the clusters. If we apply such scenario to A 2256, connecting the radio relic

emission to a shock front propagating outwardly in the north-western direction across the

G region of the radio relic, we can consider r2 as the post-shock region and r3 as the

preshock region. In this case we have a temperature ratio T2/T1

= 1.7. It is important to notice that this estimate is impacted by the

angle of the shock front to the line of sight. If the shock is not in the plane of the

sky, as it is likely the case for A 2256, projected mixing of shocked hot gas with cool

gas will reduce the apparent temperature of the shocked gas and increase the apparent

temperature of the cool gas, basically dropping the temperature ratio.

Regions r5 and r4, respectively on the H region of the relic and outside the outer edge,

show almost equal temperatures  and

and

in the XMM-Newton images,

although with big uncertainties. Unfortunately, region r4 is out of Suzaku

field-of-view and cannot be checked. This is anyway in agreement with previous

studies conducted by Sun et al. (2002) and Bourdin & Mazzotta (2008) that showed that this

region is cold due to the presence of a cool subcluster at an early stage merging with the

main cluster, approaching from somewhere west. Projection effects, affecting in particular

region r5, can thus be responsible for the non detection of a temperature jump across the

H region of the relic.

in the XMM-Newton images,

although with big uncertainties. Unfortunately, region r4 is out of Suzaku

field-of-view and cannot be checked. This is anyway in agreement with previous

studies conducted by Sun et al. (2002) and Bourdin & Mazzotta (2008) that showed that this

region is cold due to the presence of a cool subcluster at an early stage merging with the

main cluster, approaching from somewhere west. Projection effects, affecting in particular

region r5, can thus be responsible for the non detection of a temperature jump across the

H region of the relic.

The measured temperatures in the different regions are summarized in Table 9 for both Suzaku and XMM-Newton data.

|

Fig. 11 Regions used for the ICM temperature extraction. Colors show the XMM-Newton X-ray image, while the contours show the radio emission at a lower resolution respect to Fig. 1. |

CM temperatures kT(keV).

6. Is the Sunyaev-Zeldovich effect important?

The thermal Sunyaev-Zeldovich (SZ) effect (Sunyaev & Zeldovich 1970) consists in the inverse Compton scattering to higher energies of the photons of the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) that interact with the hot electrons in the ICM of galaxy clusters. The effect depends on the pressure produced by the plasma along the line of sight and is parametrized through the Comptonisation parameter y (see Carlstrom et al. 2002, for a review). The SZ effect produces a modification of the CMB blackbody spectrum, creating a negative flux bowl on the scale of the cluster, at GHz frequencies. This might lead to two sources of errors in our flux densities measurements at high frequencies. The first derives from a wrong setting of the zero-level in the single dish images. The zero-level in single dish observations is usually set assuming the absence of sources at the map edges, setting the intensity level to zero there, and interpolating linearly between the two opposite edges of the map. If the SZ decrement is important in the regions where zero flux was assumed (determining a negative flux in those areas), this results in a wrong setting of the zero-level of the entire map. This lead to a lower estimation of the flux densities integrated over any region in the map. In addition to this, there is the SZ decrement specific to the area used to compute the relic flux densities.

We used the integrated Comptonisation parameter YSZ as measured by Planck (Planck Collaboration XI 2011) and the universal pressure profile shape as derived by Arnaud et al. (2010), to derive the predicted pressure and Comptonisation parameter profiles for A 2256 (see Planck Collaboration Int. IV 2013). We used the derived y parameter radial profile to estimate the importance of the SZ decrement in different regions at the edges of the original Effelsberg 10 450 MHz image, to check the zero-level setting. Integrating on areas free of sources at the map edges with angular diameter of 4′, we find values of −0.1/−0.3 mJy for the CMB flux decrement. We conclude that the effect of the SZ decrement on the zero-level setting of the 10 450 MHz image is negligible. As the SZ effect increase increasing the frequency, we conclude that it does not affect the zero-level setting of the 2640 and 4850 MHz Effelsberg images.

Estimating the second effect is more complicated, especially if we believe that the relic in A 2256 is powered by a shock. In case of a shock, in fact, a sharp increase of the pressure at the shock front is expected, causing a local increase of the SZ decrement. An exact estimate of the amount of the effect requires a detailed knowledge of the shock geometry and orientation and of the pressure changes across the relic width. We estimate here an upper limit for the SZ effect on our high-frequencies flux estimates. The radio relic fluxes have been calculated in an approximatively rectangular area of ~18′ × 9′, whose major axis is located at a projected distance of ~7.2′ (~500 kpc) from the cluster X-ray main peak. If we assume that we observe the shock in the plane of the sky, we can consider a physical distance of the relic from the cluster center of ~500 kpc. This is a lower limit to the real distance relic-cluster center and maximize the SZ effect, that is higher in the denser central regions. We can derive a qualitative estimation of the possible shock pressure jump from the observed ICM temperature ratio across the relic. Inverting Eq. (5) we obtain a Mach number ~1.7. As discussed, this number can have been reduced by projection effects. We assume for the calculations a Mach number M = 2. Applying the Rankine-Hugoniot jump conditions, the ratio between the postshock P2 and preshock P1 pressures, given the Mach number M, is P2/P1 ~ 4. We estimated the SZ flux decrement in the area used for the radio relic flux measurements using Eq. (3) from Carlstrom et al. (2002) and assuming a value yPOST = 4yPRE (where yPRE was extracted from the y-profile at a corresponding distance of 7.2′) constant over all the area. This assumptions bring to an over estimation of the SZ effect because the real width of the relic is expected to be much lower than the projected one, and the increased pressure is expected to decrease again moving away from the shock front in the downstream region. With these assumptions, we obtain SZ flux decrements of ~–20 mJy, ~–4.3 mJy, ~–0.3 mJy respectively at 10 450 MHz, 4850 MHz and 2640 MHz. We stress that this numbers are upper limits for the SZ decrement. Assuming, for example, the physical distance of ~700 Kpc from the cluster center deduced by Ensslin et al. (1998) based on polarization properties, the effect at 10 450 MHz reduces to ~–11 mJy.

We plotted in Fig. 10b (green crosses) the upper limits of the relic flux at 4850 and 10 450 MHz, derived adding the upper limit SZ flux decrements (in absolute value) to the measured fluxes. The effect on the integrated radio spectrum is to make it even flatter.

7. Discussion

Independent of the acceleration mechanism, we can infer the range of energies (in terms of

the Lorentz factor γe) of the emitting electrons in the relic

region from the integrated spectrum via (Kang et al.

2012):  (6)The relic in A 2256 has been observed from very

low frequencies (~20 MHz

with LOFAR, van Weeren et al. 2012, flux densities

not published) up to very high frequencies (~10 GHz with Effelsberg). This implies, via Eq. (6), that the emitting electrons have energies

between, at least, γe,min ~ 2 × 103−4 ×

103 and γe,max ~ 4 × 104−9 ×

104. For both γe,min and γe,max, the two

values refer to assumed magnetic fields B = 5−1 μG, respectively. The energy

losses of low-energy electrons can be dominated by Coulomb interactions with the plasma,

causing a low-frequency flattening of the integrated spectrum, in the case that the density

in the relic region is rather high and the strength of the magnetic field is low (Sarazin 1999). The double power law found for the relic

in A2256 can be looked at as due to a low-frequency flattening other than a high-frequency

steepening. However, assuming an electron density of 10-3 cm-3 as estimated by Markevitch & Vikhlinin (1997) at the relic position

in A2256, and a typical value of 1 μG for the magnetic field, we calculated (from Eqs.

(7) and (9) in Sarazin 1999) that Coulomb losses do

not dominate over synchrotron losses even for the lowest energy electrons in our range

(γ ~

103). The radiative lifetime for the less energetic electrons

is trad(γe,min) ~

0.32−0.43 Gyr (for B = 5−1 μG respectively) and

trad(γe,max) ~

0.016−0.019 Gyr for the more energetic ones. Probably, whatever it is the

acceleration mechanism, it is still at work since the particles emitting at 10 GHz lose

rapidly their energy and the relic would become invisible at this frequency without a

constant supply of new particles, soon after the end of the acceleration. It is then

reasonable to consider, in case of DSA, a continuous injection model with radiative losses

dominated by IC and synchrotron emission to discuss the integrated spectrum of the radio

relic in A2256, as it is common in the literature.

(6)The relic in A 2256 has been observed from very

low frequencies (~20 MHz

with LOFAR, van Weeren et al. 2012, flux densities

not published) up to very high frequencies (~10 GHz with Effelsberg). This implies, via Eq. (6), that the emitting electrons have energies

between, at least, γe,min ~ 2 × 103−4 ×

103 and γe,max ~ 4 × 104−9 ×

104. For both γe,min and γe,max, the two

values refer to assumed magnetic fields B = 5−1 μG, respectively. The energy

losses of low-energy electrons can be dominated by Coulomb interactions with the plasma,

causing a low-frequency flattening of the integrated spectrum, in the case that the density

in the relic region is rather high and the strength of the magnetic field is low (Sarazin 1999). The double power law found for the relic

in A2256 can be looked at as due to a low-frequency flattening other than a high-frequency

steepening. However, assuming an electron density of 10-3 cm-3 as estimated by Markevitch & Vikhlinin (1997) at the relic position

in A2256, and a typical value of 1 μG for the magnetic field, we calculated (from Eqs.

(7) and (9) in Sarazin 1999) that Coulomb losses do

not dominate over synchrotron losses even for the lowest energy electrons in our range

(γ ~

103). The radiative lifetime for the less energetic electrons

is trad(γe,min) ~

0.32−0.43 Gyr (for B = 5−1 μG respectively) and

trad(γe,max) ~

0.016−0.019 Gyr for the more energetic ones. Probably, whatever it is the

acceleration mechanism, it is still at work since the particles emitting at 10 GHz lose

rapidly their energy and the relic would become invisible at this frequency without a

constant supply of new particles, soon after the end of the acceleration. It is then

reasonable to consider, in case of DSA, a continuous injection model with radiative losses

dominated by IC and synchrotron emission to discuss the integrated spectrum of the radio

relic in A2256, as it is common in the literature.

We have formulated five different possible scenarios to explain the properties of the relic, and we will discuss here the pros and cons for each of them.

7.1. Non-stationary DSA

Together, the regions G and H of the relic in A 2256 reach a length of ~1 Mpc. To date the most plausible scenario to explain such giant radio relics invoke diffusive shock acceleration (DSA) during cluster mergers. In this scenario, electrons are accelerated to an injection power-law spectrum at the shock location, and lose energy due to synchrotron and IC processes advecting downstream, causing a local steepening of the spectrum, the entity of which changes with the distance to the shock front. The continuous injection model is used to describe the situation in which these different regions are not spatially resolved and their contribution is mixed up. Assuming that the shock is continuously accelerating particles following the same power law for a time exceeding the electrons cooling time, we expect a volume-integrated spectrum that is a single straight power law with spectral index αobs = αinj + 0.5 (stationarity for the spectrum). As shown in Sect. 4.2.3, the relic in A 2256 shows, instead, a peculiar broken power law. At low frequencies (between 63 and 1369 MHz), we confirm the spectral index α ~ 0.85 previously found by van Weeren et al. (2012). This spectrum is too flat to be considered the stationary spectrum as it would imply an injection spectral index ~ 0.35, flatter than the flattest allowed by test-particle DSA theory (see Introduction). One solution is that, at low frequencies, we observe the injection synchrotron spectrum since a stationary spectrum is only attained if the time for energy losses is shorter than the age of the shock at all energies. Kang (2011) shows that the downstream integrated electron spectrum at a quasi-parallel shock is a broken power law which steepens from E− δinj to E− (δinj + 1) above E>Ebr(t), with an exponential cutoff at energies higher than Eeq. Eeq is the maximum electron energy injected, reached when the equilibrium between energy gains and losses is achieved and reflects the strength of the shock. Ebr describes more properly the electron aging and can be used to estimate the shock age. As a consequence the volume-integrated synchrotron spectrum has a spectral break and an high-frequency cut-off described by:

![$$ S(\nu) \propto \begin{cases} \nu ^{- \alpha_{\rm inj}} & \text{at } \nu <\nu_{\rm br} (t) \\[2mm] \nu ^{- (\alpha_{\rm inj}+0.5)} & \text{at } \nu_{\rm br} (t) <\nu <\nu_{\rm eq}\\[2mm] \exp(-\nu/\nu_{\rm eq}) & \text{at } \nu > \nu_{\rm eq}. \end{cases} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2015/03/aa23972-14/aa23972-14-eq175.png) If we assume that the shock started to

accelerate particles recently, we would be able to catch the break frequency and the

transition from αinj to αobs still in

the observable frequency range (non-stationarity for the spectrum), as it happens for

young radio galaxies (e.g., Murgia et al. 1999).

Assuming a νbr

~ 1.4 GHz (in correspondence of which we observe the moderate

steepening) would imply a relic age of trad(γe,1.4 GHz) ~

0.04−0.05 Gyr. An injection spectral index ~0.85 would be also in agreement with

what reported by Clarke et al. (2011). They observe

a spectral index of 0.85 at the outer edge of the relic, steepening moving across the

source towards the inner edge. This is in agreement with a scenario where the relic is

produced by a shock that is moving outwardly and is now located at the outer edge of the

relic where it is accelerating particle according to an injection spectrum with

αinj =

0.85. However, Owen et al.

(2014) recently found that the simple gradient from north to south in spectral

index does not dominate the relic structure when observed in more detail. Moreover, the

spectral index of the integrated synchrotron emission above the break frequency should be

in this case αobs

~ 1.35, while we observe a flatter spectrum with slope

~1. However, the

spectral curvature of the continuous injection model is gradual and might occur over a

broader range of frequencies than sampled here. This would place the break frequencies at

frequencies even higher than 1.4 GHz, further reducing the radiative lifetime of the

relic. This would make the radio relic in A2256 a very young radio relic.

If we assume that the shock started to

accelerate particles recently, we would be able to catch the break frequency and the

transition from αinj to αobs still in

the observable frequency range (non-stationarity for the spectrum), as it happens for

young radio galaxies (e.g., Murgia et al. 1999).

Assuming a νbr

~ 1.4 GHz (in correspondence of which we observe the moderate

steepening) would imply a relic age of trad(γe,1.4 GHz) ~

0.04−0.05 Gyr. An injection spectral index ~0.85 would be also in agreement with

what reported by Clarke et al. (2011). They observe

a spectral index of 0.85 at the outer edge of the relic, steepening moving across the

source towards the inner edge. This is in agreement with a scenario where the relic is

produced by a shock that is moving outwardly and is now located at the outer edge of the

relic where it is accelerating particle according to an injection spectrum with

αinj =

0.85. However, Owen et al.

(2014) recently found that the simple gradient from north to south in spectral

index does not dominate the relic structure when observed in more detail. Moreover, the

spectral index of the integrated synchrotron emission above the break frequency should be

in this case αobs

~ 1.35, while we observe a flatter spectrum with slope

~1. However, the

spectral curvature of the continuous injection model is gradual and might occur over a

broader range of frequencies than sampled here. This would place the break frequencies at

frequencies even higher than 1.4 GHz, further reducing the radiative lifetime of the

relic. This would make the radio relic in A2256 a very young radio relic.

One disadvantage of integrated spectra is that the spectra of different source components are mixed up. The radiative ages derived from these spectra do not necessarily represent the source ages, but rather the radiative ages of the dominant source components. For radio galaxies, for example, only when the lobes (which have accumulated the electrons produced over the source lifetime) dominate the source spectrum, the radiative age derived from the νbr is likely representative of the age of the entire source. If, instead, the spectrum is dominated by the jets or hot spots, the radiative age likely represents the permanence time of the electrons in that component and is expected to be -perhaps much- less than the source age (Murgia et al. 1999). Something similar might hold for the radio relic in A2256 if its synchrotron emission is dominated by the shock region. This might happen because the magnetic field is expected to be stronger at the shock location due to shock compression (Lucek & Bell 2000). The continuous injection model assumes, instead, a constant magnetic field over all the source, and might not be optimal to describe the integrated spectra of radio relics. In general, if the latter are dominated by the emission from the regions closer to the shock front, they are biased to flatter values. As a consequence, the shock Mach numbers derived from radio observable through Eqs. (1)−(3) are biased to higher values. This would also account for the discrepancies between the values of the Mach number derived from radio observations vs values derived from X-ray observations claimed in some case (e.g., in the cluster ZwCl 2341.1+0000, Ogrean et al. 2014).