| Issue |

A&A

Volume 564, April 2014

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A129 | |

| Number of page(s) | 15 | |

| Section | Cosmology (including clusters of galaxies) | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201322870 | |

| Published online | 17 April 2014 | |

The 400d Galaxy Cluster Survey weak lensing programme

III. Evidence for consistent WL and X-ray masses at z ≈ 0.5⋆

1

Department of PhysicsDurham University,

South Road,

Durham

DH1 3LE,

UK

e-mail:

holger.israel@durham.ac.uk

2

Argelander-Institut für Astronomie, Auf dem Hügel 71, 53121

Bonn,

Germany

3

Department of Astronomy, University of Virginia,

530 McCormick Road,

Charlottesville

VA

22904,

USA

4

Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics,

60 Gard0en Street, Cambridge

MA

02138,

USA

Received:

17

October

2013

Accepted:

11

February

2014

Context. Scaling properties of galaxy cluster observables with cluster mass provide central insights into the processes shaping clusters. Calibrating proxies for cluster mass that are relatively cheap to observe will moreover be crucial to harvest the cosmological information available from the number and growth of clusters with upcoming surveys like eROSITA and Euclid. The recent Planck results led to suggestions that X-ray masses might be biased low by ~40%, more than previously considered.

Aims. We aim to extend knowledge of the weak lensing – X-ray mass scaling towards lower masses (as low as 1 × 1014M⊙) in a sample representative of the z ~ 0.4–0.5 population. Thus, we extend the direct calibration of cluster mass estimates to higher redshifts.

Methods. We investigate the scaling behaviour of MMT/Megacam weak lensing (WL) masses for 8 clusters at 0.39 ≤ z ≤ 0.80 as part of the 400d WL programme with hydrostatic Chandra X-ray masses as well as those based on the proxies, e.g. YX = TXMgas.

Results. Overall, we find good agreement between WL and X-ray masses, with different mass bias estimators all consistent with zero. When subdividing the sample into a low-mass and a high-mass subsample, we find the high-mass subsample to show no significant mass bias while for the low-mass subsample, there is a bias towards overestimated X-ray masses at the ~2σ level for some mass proxies. The overall scatter in the mass-mass scaling relations is surprisingly low. Investigating possible causes, we find that neither the greater range in WL than in X-ray masses nor the small scatter can be traced back to the parameter settings in the WL analysis.

Conclusions. We do not find evidence for a strong (~40%) underestimate in the X-ray masses, as suggested to reconcile recent Planck cluster counts and cosmological constraints. For high-mass clusters, our measurements are consistent with other studies in the literature. The mass dependent bias, significant at ~2σ, may hint at a physically different cluster population (less relaxed clusters with more substructure and mergers); or it may be due to small number statistics. Further studies of low-mass high-z lensing clusters will elucidate their mass scaling behaviour.

Key words: galaxies: clusters: general / cosmology: observations / gravitational lensing: weak / X-rays: galaxies: clusters

Appendix A is available in electronic form at http://www.aanda.org

© ESO, 2014

1. Introduction

Galaxy cluster masses hold a crucial role in cosmology. In the paradigm of hierarchical structure formation from tiny fluctuations in the highly homogeneous early cosmos after inflation, clusters emerge via the continuous matter accretion onto local minima of the gravitational potential. Depending sensitively on cosmological parameters, the cluster mass function, i.e. their abundance as function of mass and redshift z, provides observational constraints to cosmology (e.g., Vikhlinin et al. 2009b; Allen et al. 2011; Planck Collaboration XX 2014).

Observers use several avenues to determine cluster masses: properties of the X-ray-emitting intracluster medium (ICM), its imprint on the cosmic microwave background via the Sunyaev-Zel’dovich (SZ) effect in the sub-mm regime, galaxy richness estimates and dynamical masses via optical imaging and spectroscopy, and gravitational lensing. Across all wavelengths, cluster cosmology surveys are under preparation, aiming at a complete cluster census out to ever higher redshifts, e.g. eROSITA (Predehl et al. 2010; Merloni et al. 2012; Pillepich et al. 2012) and Athena (Nandra et al. 2013; Pointecouteau et al. 2013) in X-rays, Euclid (Laureijs et al. 2011; Amendola et al. 2013), DES and LSST in the optical/near-infrared, CCAT (Woody et al. 2012) and SKA at sub-mm and radio frequencies.

Careful X-ray studies of clusters at low and intermediate redshifts yield highly precise cluster masses, but assume hydrostatic equilibrium, and in most cases spherical symmetry (e.g. Croston et al. 2008; Ettori et al. 2013). Observational evidence and numerical modelling challenge these assumptions for all but the most relaxed systems (e.g. Mahdavi et al. 2008; Rasia et al. 2012; Limousin et al. 2013; Newman et al. 2013). While simulations find X-ray masses to only slightly underestimate the true mass of clusters that exhibit no indications of recent mergers and can be considered virialised, non-thermal pressure support can lead to a >20% bias in unrelaxed clusters (Laganá et al. 2010; Rasia et al. 2012). Shi & Komatsu (2014) modelled the pressure due to ICM turbulence analytically and found a ~10% underestimate of cluster masses compared to the hydrostatic case.

Weak lensing (WL), in contrast, is subject to larger stochastic uncertainties, but can in principle yield unbiased masses, as no equilibrium assumptions are required. Details of the mass modelling however can introduce biases, in particular concerning projection effects, the source redshift distribution and the departures from an axisymmetric mass profile (Corless & King 2009; Becker & Kravtsov 2011; Bahé et al. 2012; Hoekstra et al. 2013). For individual clusters, stochastic uncertainties dominate the budget; however, larger cluster samples benefit from improved corrections for lensing systematics, driven by cosmic shear projects (e.g. Massey et al. 2013).

Most of the leverage on cosmology and structure formation from future cluster surveys will be due to clusters at higher z than have been previously investigated. Hence, the average cluster masses and signal/noise ratios for all observables are going to be smaller. Even and especially for the deepest surveys, most objects will lie close to the detection limit. Thus the scaling of inexpensive proxies (e.g. X-ray luminosity LX) with total mass needs to be calibrated against representative cluster samples at low and high z. Weak lensing and SZ mass estimates are both good candidates as they exhibit independent systematics from X-rays and a weaker z-dependence in their signal/noise ratios.

Theoretically, cluster scaling relations arise from their description as self-similar objects forming through gravitational collapse (Kaiser 1986), and deviations from simple scaling laws provide crucial insights into cluster physics. For the current state of scaling relation science, we point to the recent review by Giodini et al. (2013). As we are interested in the cluster population to be seen by upcoming surveys, we focus here on results obtained at high redshifts.

Self-similar modelling includes evolution of the scaling relation normalisations with the Hubble expansion, which is routinely measured (e.g. Reichert et al. 2011; Ettori 2013). Evolution effects beyond self-similarity, e.g. due to declining AGN feedback at low z, have been claimed and discussed (e.g. Pacaud et al. 2007; Short et al. 2010; Stanek et al. 2010; Maughan et al. 2012), but current observations are insufficient to constrain possible evolution in slopes (Giodini et al. 2013). Evidence for different scaling behaviour in groups and low-mass clusters was found by, e.g., Eckmiller et al. (2011), Stott et al. (2012), Bharadwaj et al. (2014).

Reichert et al. (2011) and Maughan et al. (2012) investigated X-ray scaling relationships including clusters at z> 1, and both stressed the increasing influence of selection effects at higher z. Larger weak lensing samples of distant clusters are just in the process of being compiled (Jee et al. 2011; Foëx et al. 2012; Hoekstra et al. 2011a, 2012; Israel et al. 2012; von der Linden et al. 2014a; Postman et al. 2012). Thus most WL scaling studies are currently limited to z ≲ 0.6, and also include nearby clusters (e.g. Hoekstra et al. 2012; Mahdavi et al. 2013, M13). The latter authors find projected WL masses follow the expected correlation with the SZ signal YSZ, corroborating similar results for more local clusters by Marrone et al. (2009, 2012). Miyatake et al. (2013) performed a detailed WL analysis of a z = 0.81 cluster discovered in the SZ using the Atacama Cosmology Telescope, and compared the resulting lensing mass against the Reese et al. (2012)YSZ–M scaling relation, in what they describe as a first step towards a high-z SZ-WL scaling study.

By compiling Hubble Space Telescope data for 27 massive clusters at 0.83 <z< 1.46, Jee et al. (2011) not only derive the relation between WL masses Mwl and ICM temperature TX, but also notice a good correspondence between WL and hydrostatic X-ray masses Mhyd. As they focus on directly testing cosmology with the most massive clusters, these authors however stop short of deriving the WL-X-ray scaling. Also using HST observations, Hoekstra et al. (2011a) investigated the WL mass scaling of the optical cluster richness (i.e. galaxy counts) and LX of 25 moderate-LX clusters at 0.3 <z< 0.6, thus initiating the study of WL scaling relations off the top of the mass function.

Comparisons between weak lensing and X-ray masses for larger cluster samples were pioneered by Mahdavi et al. (2008) and Zhang et al. (2008), collecting evidence for the ratio of weak lensing to X-ray masses Mwl/Mhyd> 1, indicating non-thermal pressure. Zhang et al. (2010), analysing 12 clusters from the Local Cluster Substructure Survey (LoCuSS), find this ratio to depend on the radius. Likewise, a difference between relaxed and unrelaxed clusters is found (Zhang et al. 2010; Mahdavi et al. 2013). Rasia et al. (2012) show that the gap between X-ray and lensing masses is more pronounced in simulations than in observations, pointing to either an underestimate of the true mass also by WL masses (cf. Bahé et al. 2012) or to simulations overestimating the X-ray mass bias.

The current disagreement between the cosmological constraints derived from Planck primary cosmic microwave background (CMB) data with Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe data, supernova data, and cluster data (Planck Collaboration XX 2014) may well be alleviated by, e.g. sliding up a bit along the Planck degeneracy curve between the Hubble factor H0 and the matter density parameter Ωm. Nevertheless, as stronger cluster mass biases than currently favoured (~40%) have also been invoked as a possible explanation, it is very important to test the cluster mass calibration with independent methods out to high z, as we do in this work.

This article aims to test the agreement of the weak lensing and X-ray masses measured by

Israel et al. (2012) for 8 relatively low-mass clusters at

z ≳ 0.4 with

scaling relations from the recent literature. The 400d X-ray sample from which our clusters

are drawn has been constructed to contain typical objects at intermediate redshifts, similar

in mass and redshift to upcoming surveys. Hence, it does not include extremely massive

low-z

clusters. We describe the observations and WL and X-ray mass measurements for the

8 clusters in Sect. 2, before presenting the central scaling relations in Sect.

3. Possible explanations for the steep slopes our

scaling relations exhibit are discussed in Sect. 4,

and we compare to literature results in Sect. 5,

leading to the conclusions in Sect. 6. Throughout this

article,  denotes the self-similar evolution factor (Hubble factor H(z)

normalised to its present-day value of H0 = 72 km s-1

Mpc-1), computed for a flat universe with matter and dark energy

densities of Ωm = 0.3

and ΩΛ = 0.7 in units

of the critical density.

denotes the self-similar evolution factor (Hubble factor H(z)

normalised to its present-day value of H0 = 72 km s-1

Mpc-1), computed for a flat universe with matter and dark energy

densities of Ωm = 0.3

and ΩΛ = 0.7 in units

of the critical density.

2. Observations and data analysis

2.1. The 400d weak lensing survey

This article builds on the weak lensing analysis for 8 clusters of galaxies (Israel et al. 2010, 2012, Paper I and Paper II hereafter) selected from the 400d X-ray selected sample of clusters (Burenin et al. 2007; Vikhlinin et al. 2009a, V09a). From the ~400 deg2 of all suitable ROSAT PSPC observations, Burenin et al. (2007) compiled a catalogue of serendipitously detected clusters, i.e. discarding the intentional targets of the ROSAT pointings. For a uniquely complete subsample of 36 X-ray luminous (LX ≳ 1044 erg / s) high-redshift (0.35 ≤ z ≤ 0.89) sources, V09a obtained deep Chandra data, weighing the clusters using three different mass proxies (Sect. 3.2). Starting from the cluster mass function computed by V09a, Vikhlinin et al. (2009b) went on to constrain cosmological parameters. For brevity, we will refer to the V09a high-z sample as the 400d sample. The 400d weak lensing survey follows up these clusters in weak lensing, determining independent WL masses with the ultimate goals of deriving the lensing-based mass function for the complete sample and to perform detailed consistency checks. Currently, we have determined WL masses for 8 clusters observed in four dedicated MMT/Megacam runs (see Papers I and II). Thus, our scaling relation studies are largely limited to this subset of clusters, covering the sky between αJ2000 = 13h30m–24h with δJ2000> 10° and αJ2000 = 0h–08h30m with δJ2000> 0°.

2.2. Weak lensing analysis

Measured properties of the 400d MMT cluster sample.

We present only a brief description of the WL analysis in this paper; for more details see Paper II. Basic data reduction is performed using the THELI pipeline for multi-chip cameras (Erben et al. 2005; Schirmer 2013), adapted to MMT/Megacam. We employ the photometric calibration by Hildebrandt et al. (2006). Following Dietrich et al. (2007), regions of the THELI coadded images not suitable for WL shear measurements are masked. Shear is measured using an implementation of the “KSB+” algorithm (Kaiser et al. 1995; Erben et al. 2001), the “TS” pipeline (Heymans et al. 2006; Schrabback et al. 2007; Hartlap et al. 2009). Catalogues of lensed background galaxies are selected based on the available colour information. For clusters covered in three filters, we include galaxies based on their position in colour–colour–magnitude space (Paper II; see Klein et al., in prep., for a generalisation). For clusters covered only in one passband, we apply a magnitude cut. Where available, colour information also enables us to quantify and correct for the dilution by residual cluster members (Hoekstra 2007) in the shear catalogues. The mass normalisation of the WL signal is set by the mean lensing depth ⟨ β ⟩, defined as β = Dds/Ds, the ratio of angular diameter distances between the deflector and the source, and between the observer and the source. The Ilbert et al. (2006) CFHTLS Deep fields photometric redshift catalogue serves as a proxy for estimating ⟨ β ⟩ and for calibrating the background selection.

The tangential ellipticity profiles given the ROSAT cluster centres are modelled by fitting the reduced shear profile (Bartelmann 1996; Wright & Brainerd 2000) corresponding to the Navarro et al. (1996, 1997, NFW) density profile between 0.2 Mpc and 5.0 Mpc projected radius. Input ellipticities are scaled according to the Hartlap et al. (2009) calibration factor and, where applicable, with the correction for dilution by cluster members. We consider the intrinsic source ellipticity measured from the data, accounting for its dependence on the shear (Schneider et al. 2000).

Lensing masses are inferred by evaluating a χ2 merit function on a grid in radius r200 and concentration c200. The latter is poorly constrained in the direct fit, so we marginalise over it assuming an empirical mass-concentration relation. In addition to the direct fit approach, in Israel et al. (2012), we report masses using two different mass-concentration relations: Bullock et al. (2001, B01), and Bhattacharya et al. (2013, B13)1. Finding the masses using B01 or B13 makes them less susceptible to variations in the model in Paper II, we explore their effect further in Sect. 4.1.

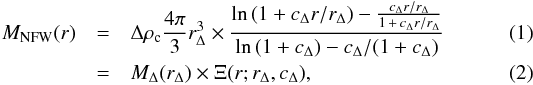

2.3. Choice of the overdensity contrast

Cluster scaling relations are usually given for the mass contained within a radius

r500, corresponding to an overdensity

Δ = 500 compared to the

critical density ρc of the Universe at the cluster

redshift. This Δ is chosen

because the best-constrained X-ray masses are found close to r500, determined

by the particle backgrounds of Chandra and XMM-Newton

(cf. Okabe et al. 2010a). Currently, only

Suzaku allows direct constraints upon X-ray masses at r200 (see Reiprich et al. 2013, and references therein). In order

to compare to the results from the Vikhlinin et al.

(2009a)Chandra analysis, we compute our Δ = 500 WL masses from our Δ = 200 masses, assuming the fitted NFW

profiles given by (r200,c200)

to be correct. Independent of Δ

> 1, the cumulative mass of a NFW halo,

described by rΔ and cΔ, out to a

test radius r

is given by:  separating

into the mass MΔ and a function we call Ξ(r;rΔ,cΔ).

Equating Eq. (1) with r =

r500 for Δ = 200 and Δ′ = 500, we arrive at this

implicit equation for r500, which we solve numerically:

separating

into the mass MΔ and a function we call Ξ(r;rΔ,cΔ).

Equating Eq. (1) with r =

r500 for Δ = 200 and Δ′ = 500, we arrive at this

implicit equation for r500, which we solve numerically:

(3)

(3)

2.4. X-ray analysis

Under the strong assumptions that the ICM is in hydrostatic equilibrium and follows a

spherically symmetric mass distribution, the cluster mass within a radius r can be calculated as (see

e.g. Sarazin 1988):  (4)from

the ICM density and temperature profiles ρg(r) and

TX(r), where

G is the

gravitational constant, mp is the proton mass, and

μ = 0.5954

the mean molecular mass of the ICM. The ICM density is modelled by fitting the observed

Chandra surface brightness profile, assuming a primordial He abundance

and an ICM metallicity of 0.2

Z⊙, such that ρg(r) = 1.274

mpn(r).

We use a Vikhlinin et al. (2006) particle density

profile with

(4)from

the ICM density and temperature profiles ρg(r) and

TX(r), where

G is the

gravitational constant, mp is the proton mass, and

μ = 0.5954

the mean molecular mass of the ICM. The ICM density is modelled by fitting the observed

Chandra surface brightness profile, assuming a primordial He abundance

and an ICM metallicity of 0.2

Z⊙, such that ρg(r) = 1.274

mpn(r).

We use a Vikhlinin et al. (2006) particle density

profile with  .

Extending the widely-used β-profile (Cavaliere

& Fusco-Femiano 1978), it allows for prominent cluster cores as well as

steeper surface brightness profiles in the cluster outskirts to be modelled by additional

terms. Regarding the systematic differences Rozo et al. (2014b) find between X-ray mass

algorithms, we point out that we employ the V09a profiles directly rather than re-deriving

them from their parameters.

.

Extending the widely-used β-profile (Cavaliere

& Fusco-Femiano 1978), it allows for prominent cluster cores as well as

steeper surface brightness profiles in the cluster outskirts to be modelled by additional

terms. Regarding the systematic differences Rozo et al. (2014b) find between X-ray mass

algorithms, we point out that we employ the V09a profiles directly rather than re-deriving

them from their parameters.

The relatively low signal/noise in the Chandra data renders the determination of individual temperature profiles difficult. Rather, we fit a global TX (Table 1; V09a) and assume the empirical average temperature profile TX(r) = TX(1.19 − 0.84r/r200)Reiprich et al. (2013) derive from compiling all available Suzaku temperature profiles (barring only the two most exceptional clusters). For r200, we use the WL results from Paper II2.

Equation (4) provides us with a cumulative mass profile. We evaluate this profile at some rtest, e.g. from WL, and propagate the uncertainty in rtest, together with the uncertainty in TX.

Hydrostatic equilibrium and sphericity are known to be problematic assumptions for many clusters. Nonetheless, hydrostatic masses are commonly used in the literature in comparisons to WL masses. Our goal is to study if and how biases due to deviations from the above-mentioned assumptions show up.

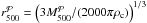

2.5. Mass estimates

Table 1 comprises the key results on radii

r500 and the corresponding mass estimates.

By  ,

we denote a mass measured from data on proxy

,

we denote a mass measured from data on proxy  within a radius defined by proxy

within a radius defined by proxy  .

We use five mass estimates:

.

We use five mass estimates:  . The first two are the weak lensing

(wl) and hydrostatic X-ray masses (hyd), as introduced in Sects. 2.2 and 2.4. Having analysed deep

Chandra observations they acquired, Vikhlinin et al. (2009a) present three further mass estimates for all

36 clusters in the complete

sample. Based on the proxies TX, the ICM mass Mgas, and

YX =

TXMgas, mass

estimates MT, MG, and

MY are quoted in Table 2 of V09a. We point

out that V09a obtain these estimates by calibrating the mass scaling relations for

respective proxy on local clusters (see their Table 3). V09a further provide a detailed

account of the relevant systematic sources of uncertainty.

. The first two are the weak lensing

(wl) and hydrostatic X-ray masses (hyd), as introduced in Sects. 2.2 and 2.4. Having analysed deep

Chandra observations they acquired, Vikhlinin et al. (2009a) present three further mass estimates for all

36 clusters in the complete

sample. Based on the proxies TX, the ICM mass Mgas, and

YX =

TXMgas, mass

estimates MT, MG, and

MY are quoted in Table 2 of V09a. We point

out that V09a obtain these estimates by calibrating the mass scaling relations for

respective proxy on local clusters (see their Table 3). V09a further provide a detailed

account of the relevant systematic sources of uncertainty.

The radii  listed in

Table 1 are obtained from

listed in

Table 1 are obtained from

. Using Eqs. (1) and (4), we then derive the WL and hydrostatic masses, respectively, within these

radii. We emphasise that all WL mass uncertainties quoted in Table 1 are purely statistical and do not include any of the systematics

discussed in Paper II.

. Using Eqs. (1) and (4), we then derive the WL and hydrostatic masses, respectively, within these

radii. We emphasise that all WL mass uncertainties quoted in Table 1 are purely statistical and do not include any of the systematics

discussed in Paper II.

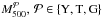

2.6. Fitting algorithm for scaling relations

The problem of selecting the best linear representation y = A +

Bx for a sample of (astronomical) observations of two

quantities {

xi } and

{

yi } can be surprisingly

complex. A plethora of algorithms and literature cope with the different assumptions about

measurement uncertainties one can or has to make (e.g. Press et al. 1992; Akritas & Bershady

1996; Tremaine et al. 2002; Kelly 2007; Hogg et al.

2010; Williams et al. 2010; Andreon & Hurn 2012; Feigelson & Babu 2012). The challenges observational

astronomers have to tackle when trying to reconcile the prerequisites of statistical

estimators with the realities of astrophysical data are manifold, including

heteroscedastic uncertainties (i.e. depending non-trivially on the data themselves),

intrinsic scatter, poor knowledge of systematics, poor sample statistics, “outlier”

points, and non-Gaussian probability distributions. Tailored to the problem of galaxy

cluster scaling relations, Maughan (2014) proposed

a “self-consistent” modelling approach based on the fundamental observables. A full

account of these different effects exceeds the scope of this article. We choose the

relatively simple fitexy algorithm (Press et al. 1992), minimising the estimator  (5)which

allows the uncertainties σx,i and

σy,i to vary for

different data points xi and

yi, but assumes them to

be drawn from a Gaussian distribution. To accommodate intrinsic scatter,

(5)which

allows the uncertainties σx,i and

σy,i to vary for

different data points xi and

yi, but assumes them to

be drawn from a Gaussian distribution. To accommodate intrinsic scatter,

in Eq. (5) can be replaced by

in Eq. (5) can be replaced by

(e.g. Weiner et al. 2006; Andreon & Hurn 2012). We test for intrinsic scatter using

mpfitexy (Markwardt 2009;

Williams et al. 2010), but in most cases, due to

the small χ2 values, find the respective parameter

not invoked. Thus we decide against this additional complexity. A strength of Eq. (5) is its invariance under changing

x and

y (e.g.

Tremaine et al. 2002); i.e., we do not assume

either to be “the independent variable”.

(e.g. Weiner et al. 2006; Andreon & Hurn 2012). We test for intrinsic scatter using

mpfitexy (Markwardt 2009;

Williams et al. 2010), but in most cases, due to

the small χ2 values, find the respective parameter

not invoked. Thus we decide against this additional complexity. A strength of Eq. (5) is its invariance under changing

x and

y (e.g.

Tremaine et al. 2002); i.e., we do not assume

either to be “the independent variable”.

|

Fig. 1 Scaling of weak lensing masses |

Rather than propagating the (unknown) distribution functions in the mass

uncertainties3, we approximate 1σ Gaussian uncertainties

in decadic log-space, applying the symmetrisation:  (6)where

(6)where

and

and

are the upper

and lower limits of the 1σ interval (in linear space) for the datum

ξi, given the

uncertainties

are the upper

and lower limits of the 1σ interval (in linear space) for the datum

ξi, given the

uncertainties  . All our

calculations and plots use {

xi } : = {

log ξi } and

{

σx,i } : = {

σ(log ξi)

}, with log ≡

log 10.

. All our

calculations and plots use {

xi } : = {

log ξi } and

{

σx,i } : = {

σ(log ξi)

}, with log ≡

log 10.

3. Results

3.1. Weak lensing and hydrostatic masses

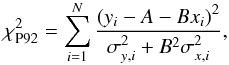

Measurements of the X-ray – WL mass bias.

|

Fig. 2 Ratios between X-ray and WL masses as a function of WL mass. Panel A)

shows log (Mhyd/Mwl)

within |

The first and single most important observation is that hydrostatic masses

, i.e. evaluated at

r500 as found from weak lensing, and weak

lensing masses

, i.e. evaluated at

r500 as found from weak lensing, and weak

lensing masses  roughly agree with each other

(Table 1). Our second key observation is the very

tight scaling behaviour between

roughly agree with each other

(Table 1). Our second key observation is the very

tight scaling behaviour between  and

and

, as Fig.

1 shows. In all cases presented in Fig. 1, and most of the ones we tested, all data points are

consistent with the best-fit relation. Consequently, the fits return small values of

, as Fig.

1 shows. In all cases presented in Fig. 1, and most of the ones we tested, all data points are

consistent with the best-fit relation. Consequently, the fits return small values of

(see

Table 2). Bearing in mind that we only use

stochastic uncertainties, this points to some intrinsic correlation of the WL and

hydrostatic masses. We will discuss this point in Sect. 4.2.

(see

Table 2). Bearing in mind that we only use

stochastic uncertainties, this points to some intrinsic correlation of the WL and

hydrostatic masses. We will discuss this point in Sect. 4.2.

Finally, we find the slope of the  –

– relation (dashed lines in Fig.

1) to be steeper than unity (dotted line): using

the “default model”, i.e. the analysis described in Sect. 2, a fitexy fit yields 1.71 ± 0.64 for the “cfit” case

(concentration parameters from the shear profile fits, cf. Paper II; upper panel of Fig.

1), and 1.46 ± 0.57, if the B13 mass-concentration relation is applied

(“cB13”; lower panel). The different slopes

in the cfit and cB13 cases are

mainly due to the two clusters, CL 1641+4001 and CL 1701+6414, in which the weak lensing

analysis revealed shallow tangential shear profiles due to extended surface mass plateaus

(cf. Figs. 3 and 5 of Paper II). This will be the starting point for further analysis and

interpretation in Sect. 4.1.

relation (dashed lines in Fig.

1) to be steeper than unity (dotted line): using

the “default model”, i.e. the analysis described in Sect. 2, a fitexy fit yields 1.71 ± 0.64 for the “cfit” case

(concentration parameters from the shear profile fits, cf. Paper II; upper panel of Fig.

1), and 1.46 ± 0.57, if the B13 mass-concentration relation is applied

(“cB13”; lower panel). The different slopes

in the cfit and cB13 cases are

mainly due to the two clusters, CL 1641+4001 and CL 1701+6414, in which the weak lensing

analysis revealed shallow tangential shear profiles due to extended surface mass plateaus

(cf. Figs. 3 and 5 of Paper II). This will be the starting point for further analysis and

interpretation in Sect. 4.1.

Although the cB13 slope is consistent with the expected

1:1 relation, such a  –

– relation

would translate to extreme biases between X-ray and WL masses if extrapolated to higher

and lower masses. Especially for masses of a few 1015M⊙, ample observations

disagree with the extrapolated Mwl>

2Mhyd. We do not claim our data to have

such predicting power outside its mass range. Rather, we focus on what can be learnt about

the X-ray/WL mass bias in our 0.4 ~

z ~ 0.5 mass range, which we, for the first time,

study in the mass range down to ~1 ×

1014M⊙.

relation

would translate to extreme biases between X-ray and WL masses if extrapolated to higher

and lower masses. Especially for masses of a few 1015M⊙, ample observations

disagree with the extrapolated Mwl>

2Mhyd. We do not claim our data to have

such predicting power outside its mass range. Rather, we focus on what can be learnt about

the X-ray/WL mass bias in our 0.4 ~

z ~ 0.5 mass range, which we, for the first time,

study in the mass range down to ~1 ×

1014M⊙.

We are using three methods to test for the biases between X-ray and WL masses. First, we compute the logarithmic bias b = ⟨ log ξ − log η ⟩, which we define as the average logarithmic difference between two general quantities ξ and η. Its interpretation is that 10bη is the average value corresponding to ξ. The uncertainty in b is given by the standard error of (log ξ − log η). Hence, our measurement of b = − 0.02 ± 0.04 for cB13 corresponds to a vanishing fractional bias of ⟨ Mhyd ⟩ ≈ (0.97 ± 0.09) ⟨ Mwl ⟩.

Given the small sample size, large uncertainties, and the tight scaling relations in Fig.

1 pointing to some correlation between the WL and

X-ray masses, we base our further tests on a Monte Carlo (MC) analysis including the

jackknife test. For 105 realisations, we chose

with random δξi,k

drawn from zero-mean distributions assembled from two Gaussian halves with variances

with random δξi,k

drawn from zero-mean distributions assembled from two Gaussian halves with variances

for the

negative and

for the

negative and  for the

positive half4. This provides a simple way of

accommodating asymmetric uncertainties (cf. Paper II and Table 1). Then we take the logarithm and again symmetrise the errors. We

repeat for

for the

positive half4. This provides a simple way of

accommodating asymmetric uncertainties (cf. Paper II and Table 1). Then we take the logarithm and again symmetrise the errors. We

repeat for  .

On top, for each realisation

.

On top, for each realisation  , we discard one cluster after

another, yielding a total of 8 ×

105 samples.

, we discard one cluster after

another, yielding a total of 8 ×

105 samples.

Based on those MC/jackknife realisations, we compute our second bias estimator

. In order to achieve

the best possible robustness against large uncertainties and small cluster numbers, we

quote the ensemble median and dispersion. We find

. In order to achieve

the best possible robustness against large uncertainties and small cluster numbers, we

quote the ensemble median and dispersion. We find  for cB13, in good agreement with

b = − 0.02 ±

0.04, i.e. a median WL/X-ray mass ratio of 1.

for cB13, in good agreement with

b = − 0.02 ±

0.04, i.e. a median WL/X-ray mass ratio of 1.

Fitting log (MX/Mwl)

as a function of Mwl and averaging over the MC/jackknife

samples, we obtain our third bias estimator, an intercept A at the pivot mass of

. We

find

. We

find  for cB13, again consistent with vanishing

bias.

for cB13, again consistent with vanishing

bias.

3.2. Lensing masses and X-ray masses from proxies

Figures 2 and A.2, as well as Table 2 present the three

different X-ray/WL mass bias estimates for four X-ray mass observables:

using

cB13 from Sect. 3.1 in Panel A of Fig. 2,

using

cB13 from Sect. 3.1 in Panel A of Fig. 2,

in Panel B

of Fig. 2,

in Panel B

of Fig. 2,  in Panel A

of Fig. A.2,

in Panel A

of Fig. A.2,  in Panel B

of Fig. A.2. The last three are the proxy-based Vikhlinin et al. (2009a) X-ray mass estimators defined

in Sect. 2.5. While Panel A uses

in Panel B

of Fig. A.2. The last three are the proxy-based Vikhlinin et al. (2009a) X-ray mass estimators defined

in Sect. 2.5. While Panel A uses

, the other

three panel use the respective

, the other

three panel use the respective  .

.

Long-dashed lines and dark-grey boxes in Fig. 2 display b and its error. Short-dashed lines and light-grey boxes denote bMC. The intercept A is located at the intersection of the dot-dashed fit and dotted zero lines. We also show bMC for the low-mass and high-mass clusters separately, splitting at MwlE(z) = Mpiv; the respective 1σ ranges are shown as outline boxes.

We observe remarkable agreement between the X-ray/WL mass ratios and bias fits from all four X-ray observables (which are not fully independent). For each of them, all three bias estimates agree with each other, and all are consistent with no X-ray/WL mass bias. We find no evidence for X-ray masses being biased low by ~40% in our cluster sample, as it has been suggested to explain the Planck CMB – SZ cluster counts discrepancy. While bMC ≥ 0.2 (≳35% mass bias) lies within the possible range of the high-Mwl bin, in particular using the gas mass MG, the overall cluster sample does not support this hypothesis. We point out that bMC was designed to be both robust against possible effects of large uncertainties and the small number of clusters in this first batch of 400d WL clusters. The larger uncertainties in bMC compared to b are directly caused by the jackknife test and the account for possible fit instability in the MC method.

The slopes B quantifying the Mwl dependence of the X-ray/WL mass ratio are significantly negative in all of our measurements. This directly corresponds to the steep slope in the mass-mass scaling (Fig. 1). Predicting cluster masses for very massive clusters (or low-mass groups) from B = − 0.75 for MY would yield MX = Mwl/ 2 at 1015 M⊙/E(z) (and MX = 2.8 Mwl at 1014M⊙/E(z)). Such ratios are at odds with existing measurements. Therefore, we refrain from extrapolating cluster masses, but interpret the slopes B as indicative of a possibly mass-dependent X-ray/WL mass ratio. This evidence is more prudently presented as the ~2σ discrepancy between the low-Mwl and high-Mwl mass bins for all three V09a X-ray observables.

4. A mass-dependent bias?

In this section, we analyse two unexpected outcomes of our study in greater detail: the clear correlation between the MX/Mwl measurement of the individual clusters and their lensing masses, and the unusually small scatter in our scaling relations. Results for ancillary scaling relations that we present in Appendix A underpin the findings of Fig. 1 and Table 2. To begin with, we emphasise that the mass-dependent bias is not caused by the conflation of a large z range; all but one of our clusters inhabit the range 0.39 ≤ z ≤ 0.53 across which E(z) varies by <10%, and we accounted for this variation. As Fig. A.2 shows, this also leaves us with little constraining power with regard to a z-dependent bias, at least until the 400d WL survey becomes more complete.

4.1. Role of c200 and departures from NFW profile

Figure 1 shows that the Mwl–MX scaling relation sensitively depends on the choice for the cluster concentration parameter c200. This translates into more positive bias estimates for cfit as compared to cB13 (Table 2). The difference is caused by the two flat-profile clusters for which NFW fits yield low masses but do not capture all the large-scale mass distribution, in particular if c200 is determined directly from the data, rather than assuming a mass-concentration relation (cf. the discussion of the concentration parameter in Paper II and Foëx et al. 2012). This induces a bias towards low masses in the r200 → r500 conversion. If these two “irregular” clusters (dotted ring symbols in Fig. 1) are excluded, the “regular clusters only” Mwl–MX scaling relations (dash-dotted lines) differ for the cfit, but not for the cB13 case. Moreover, their mass ratios are consistent with the other high-Mwl clusters for cB13. We thus confirm that assuming a mass-concentration relation and marginalising over c200 is advantageous for scaling relations. We note that Comerford et al. (2010) observed a correlation between the scatters in the mass-concentration and mass-temperature relations and advocated the inclusion of unrelaxed clusters in scaling relation studies.

Because NFW profile fits do not capture the complete projected mass morphologies of

irregular clusters, the assumption of that profile for

(Eq. 3), and

(Eq. 3), and  , etc. (Sect. 3.2) could introduce a further bias. Aperture-based

lensing masses, e.g. the ζc statistics (Clowe et al. 1998) employed by Hoekstra

et al. (2012) provide an alternative. However, Okabe et al. (2013) demonstrated by the stacking of 50 clusters from the Local Cluster

Substructure Survey (0.15

<z<

0.3), that the average weak lensing profile does follow NFW to a high

degree, at least at low redshift. Furthermore, the Planck

Collaboration (2013) finds a trend of Mwl/Mhyd

with the ratio of concentration parameters measured from weak lensing and X-rays.

, etc. (Sect. 3.2) could introduce a further bias. Aperture-based

lensing masses, e.g. the ζc statistics (Clowe et al. 1998) employed by Hoekstra

et al. (2012) provide an alternative. However, Okabe et al. (2013) demonstrated by the stacking of 50 clusters from the Local Cluster

Substructure Survey (0.15

<z<

0.3), that the average weak lensing profile does follow NFW to a high

degree, at least at low redshift. Furthermore, the Planck

Collaboration (2013) finds a trend of Mwl/Mhyd

with the ratio of concentration parameters measured from weak lensing and X-rays.

4.2. Correlation between mass estimates

In Table 2, we quote

for the

Mwl–MX scaling

relations, using the same MC/jackknife samples as for the bias tests. For the ones

involving hydrostatic masses, we measure

for the

Mwl–MX scaling

relations, using the same MC/jackknife samples as for the bias tests. For the ones

involving hydrostatic masses, we measure  . We

evaluated

. We

evaluated  at

at

in order

to measure both estimates within the same physical radius, in an “apples with apples”

comparison. But using the lensing-derived radius also introduces an unknown amount of

correlation, a possible (partial) cause of the measured low

in order

to measure both estimates within the same physical radius, in an “apples with apples”

comparison. But using the lensing-derived radius also introduces an unknown amount of

correlation, a possible (partial) cause of the measured low

values.

values.

We test for the impact of the correlation by measuring both Mwl and

Mhyd within a fixed physical radius

for all clusters, and choose rfix = 800 kpc as a rough sample average

of r500. Surprisingly, we find an only

slightly higher  , still

<1

(see Table 2). As before, the bias estimators are

consistent with zero. Fixed radii of 600

kpc and 1000

kpc give similar results (Table 2 and Fig. A.2). with a tentative trend of

increasing

, still

<1

(see Table 2). As before, the bias estimators are

consistent with zero. Fixed radii of 600

kpc and 1000

kpc give similar results (Table 2 and Fig. A.2). with a tentative trend of

increasing  with

smaller radii. Interestingly, a low

with

smaller radii. Interestingly, a low  is also

found for the Mwl–MT and

MT–Mhyd relations

(Table A.2). The latter is expected, because

Mhyd are derived from the same

TX and depend sensitively on them. This

all suggests that the small scatter is not driven by using

is also

found for the Mwl–MT and

MT–Mhyd relations

(Table A.2). The latter is expected, because

Mhyd are derived from the same

TX and depend sensitively on them. This

all suggests that the small scatter is not driven by using

, but by

some other intrinsic factor.

, but by

some other intrinsic factor.

If the uncertainties in Mwl were overestimated significantly,

this would obviously explain the low  . However,

we do not even include systematic effects here. Moreover, the quoted Mwl

uncertainties directly come from the NFW modelling of Paper II and reflect the

Δχ2 from their Eq. (3), given the shear

catalogue. The errors are dominated by the intrinsic source ellipticity σε, for which we, after

shear calibration, find values of ~0.3, consistent with other ground-based WL experiments. Therefore,

despite the allure of our WL errors being overestimated, we do not find evidence for this

hypothesis in our shear catalogues. Furthermore, the quoted Mwl

uncertainties are consistent with the aperture mass detection significances we reported in

Paper II.

. However,

we do not even include systematic effects here. Moreover, the quoted Mwl

uncertainties directly come from the NFW modelling of Paper II and reflect the

Δχ2 from their Eq. (3), given the shear

catalogue. The errors are dominated by the intrinsic source ellipticity σε, for which we, after

shear calibration, find values of ~0.3, consistent with other ground-based WL experiments. Therefore,

despite the allure of our WL errors being overestimated, we do not find evidence for this

hypothesis in our shear catalogues. Furthermore, the quoted Mwl

uncertainties are consistent with the aperture mass detection significances we reported in

Paper II.

4.3. Dilution by cluster members and foregrounds

Comparing the complete set of mass-mass scaling relations our data offer (Table A.2), we trace the mass-dependence of the bias seen in

Fig. 2 back to the different ranges spanned by the

estimates for r500. While the ratio of minimum to

maximum is ≈0.75 for

,

,

, and

, and

, the same

ratio is 0.57 for

, the same

ratio is 0.57 for  , using the

B13 M–c relation. In the following, we discuss the

potential influence of several sources of uncertainty in the WL masses, showing that the

dispersion between lowest and highest

, using the

B13 M–c relation. In the following, we discuss the

potential influence of several sources of uncertainty in the WL masses, showing that the

dispersion between lowest and highest  is likely

an inherent feature rather than a modelling artefact.

is likely

an inherent feature rather than a modelling artefact.

In Paper II, we discussed the great effort we took in constructing the best-possible homogeneous analysis from the quite heterogeneous MMT imaging data. Unfortunately, we happen to find higher Mwl for all clusters with imaging in three bands than for the clusters with imaging in one band. We emphasise there are no trends with limiting magnitude, seeing, or density nKSB of galaxies with measurable shape (cf. Tables 1 and 2 in Paper II).

In the cases where three-band imaging is available, our WL model includes a correction

for the diluting effect residual cluster member galaxies impose on the shear catalogue.

For the other clusters, no such dilution correction could be applied. A rough estimate of

the fraction of unlensed galaxies remaining after background selection suggests that the

contamination in single-band catalogues is ~30–50% higher than with the more sophisticated galaxy-colour based

method. Therefore, we re-calculate the scaling relations, switching off the dilution

correction (long dashed line and thin ring symbols in Fig. 1). This lowers the r500 values by ~6% and the masses by 10–15%. For both the

–

– and

and

–

– relations,

we only observe a slightly smaller difference between bMC for the

high- and low-Mwl bins (Tables 2 and A.2), not significant given

the uncertainty margins.

relations,

we only observe a slightly smaller difference between bMC for the

high- and low-Mwl bins (Tables 2 and A.2), not significant given

the uncertainty margins.

|

Fig. 3 Comparisons with literature data. Left panel: black symbols show

z> 0.35 clusters from

Mahdavi et al. (2013), whose best-fit using

Eq. (5) is shown by the dot-dashed

line. The cluster CL 1524+0957 is indicated by a diamond symbol. Coloured symbols

and the dashed line show the “default” |

The dilution of the shear signal by an increased number of galaxies not bearing a shear signal can also be expressed as a overestimation of the mean lensing depth ⟨ β ⟩. We model a possible lensing depth bias by simultaneously adding the uncertainty σ( ⟨ β ⟩) for the three-band clusters and subtracting it for the single-band ones, maximising the leveraging effect on the masses. Similar to the previous experiment5 we still observe a mass-dependent bias, with little change to the default model.

We further tested alternative choices of cluster centre and fitting range, but do not

observe significant changes to the mass dependent-bias or to

(see

Appendix A.3). Although ⟨ β ⟩ is calculated for all

clusters from the same catalogues, related systematics would affect the mass

normalisation, but not the relative stochastic uncertainties, which determine

(see

Appendix A.3). Although ⟨ β ⟩ is calculated for all

clusters from the same catalogues, related systematics would affect the mass

normalisation, but not the relative stochastic uncertainties, which determine

. As we

consider a drastic overestimation of the purely statistic uncertainties in the WL

modelling being unlikely (Sect. 4.2), the cause of

the low

. As we

consider a drastic overestimation of the purely statistic uncertainties in the WL

modelling being unlikely (Sect. 4.2), the cause of

the low  values

remains elusive. If a WL analysis effect is responsible for one or both anomalies, it has

to be of a more subtle nature than the choices investigated here.

values

remains elusive. If a WL analysis effect is responsible for one or both anomalies, it has

to be of a more subtle nature than the choices investigated here.

4.4. A statistical fluke?

We summarise that the  –

– scaling

relations we observe show an unusual lack of scatter and that we find a ~2σ difference between the X-ray/WL mass ratios of

our high- and low-Mwl clusters. The latter effect can be

traced back to the considerable span in cluster lensing signal, which is only partly due

to different background selection procedures and the dilution correction that was only

applied for clusters imaged in three bands.

scaling

relations we observe show an unusual lack of scatter and that we find a ~2σ difference between the X-ray/WL mass ratios of

our high- and low-Mwl clusters. The latter effect can be

traced back to the considerable span in cluster lensing signal, which is only partly due

to different background selection procedures and the dilution correction that was only

applied for clusters imaged in three bands.

The question then arises if the mass-dependent bias is caused by an unlucky selection of

the 8 MMT clusters from V09’s wider sample of 36. The 8 clusters were chosen to be

observed first merely because of convenient telescope scheduling, and appear typical of

the larger sample in terms of redshift and X-ray observables. The MMT clusters trace well

the mass range and dispersion spanned by all 36 clusters in their  –

– relation.

We observe the expected vanishing slopes for log (MT/MY)

as a function of MY, both for the 8 MMT clusters and for

the complete sample of 36 (Table A.2).

relation.

We observe the expected vanishing slopes for log (MT/MY)

as a function of MY, both for the 8 MMT clusters and for

the complete sample of 36 (Table A.2).

In Table 2, we observe significant scatter

( ) in

the

) in

the  –

– relation,

while Okabe et al. (2010b) and M 13 reported

particularly low scatter in MG, comparing to WL masses. This large

intrinsic scatter seems to be a feature of the overall 400d sample: plotting

MG versus the two other V09 X-ray masses

of all 36 clusters, we also

find

relation,

while Okabe et al. (2010b) and M 13 reported

particularly low scatter in MG, comparing to WL masses. This large

intrinsic scatter seems to be a feature of the overall 400d sample: plotting

MG versus the two other V09 X-ray masses

of all 36 clusters, we also

find  (Table

A.2), as well as significant non-zero logarithmic

biases. While tracing the cause of this observation is beyond the scope of this article,

it deserves further study. Because two of the clusters with highest

(Table

A.2), as well as significant non-zero logarithmic

biases. While tracing the cause of this observation is beyond the scope of this article,

it deserves further study. Because two of the clusters with highest

are covered by our MMT subsample, we observe a more mass-dependent MG/MY,T

ratio than for all 36. Overall, however, the MMT subsample is not a very biased selection.

are covered by our MMT subsample, we observe a more mass-dependent MG/MY,T

ratio than for all 36. Overall, however, the MMT subsample is not a very biased selection.

4.5. Physical causes

An alternative and likely explanation for the mass-dependent bias we observe could be a high rate of unrelaxed clusters, especially for our least massive objects. If the departure from hydrostatic equilibrium were stronger among the low-mass clusters than for the massive ones, this would manifest in mass ratios similar to our results. Simulations show the offset from hydrostatic equilibrium to be mass-dependent (Rasia et al. 2012), despite currently being focused on the high-mass regime. Variability in the non-thermal pressure support with mass (Laganá et al. 2013) may be exacerbated by small number statistics. At high z, the expected fraction of merging clusters, especially of major mergers, increases. Unrelaxed cluster states are known to affect X-ray observables and, via the NFW fitting, also lensing mass estimates. Indeed, the two most deviant systems in Fig. 2 are CL 1416+4446 and the flat-profile “shear plateau” cluster CL 1641+4001. Although the first shows an inconspicuous shear profile, we suspect it to be part of a possibly interacting supercluster, based on the presence of two nearby structures at the same redshift, detected in X-ray as well as in our lensing maps (Paper II). Both these clusters are classified as non-mergers in the recent Nurgaliev et al. (2013) study, introducing a new substructure estimator based on X-ray morphology. However, WL and X-ray methods are sensitive to substructure on different radial and mass scales, such that this explanation cannot be ruled out. We summarise that the greater dynamical range in WL than in X-ray masses might be linked to different sensitivities of the respective methods to substructure and mergers in the low-mass, high-z cluster population we are probing, but which is currently still underexplored.

5. Comparison with previous works

5.1. The M –M

–M relation

relation

Comparison with Mahdavi et al. (2013) results:

recently, M13 published scaling relations observed between the weak lensing and X-ray masses for a sample of 50 massive clusters, partly based on the brightest clusters from the Einstein Observatory Extended Medium Sensitivity Survey (Gioia et al. 1990). Weak lensing masses for the M13 sample have been obtained from CFHT/Megacam imaging (Hoekstra et al. 2012), while the X-ray analysis combines XMM-Newton and Chandra data. While the median redshift is z = 0.23, the distribution extends to z = 0.55, including 12 clusters at z> 0.35. Owing to their selection, these 12 clusters lie above the 400d flux and luminosity cuts, making them directly comparable to our sample.

The left panel in Fig. 3 superimposes the

and

and

of the M13

high-z

clusters on our results. The two samples overlap at the massive (≳5 ×

1014M⊙) end, but the 400d

objects probe down to 1 ×

1014M⊙ for the first time at

this z and

for these scaling relations. The slopes of the scaling relations are consistent: using

Eq. (5), we measure BM − M = 1.13 ±

0.20 for the 12 M13 objects. A joint fit with the 400d clusters (BM − M = 1.46 ±

0.57) yields BM − M = 1.15 ± 0.14 and a low

of the M13

high-z

clusters on our results. The two samples overlap at the massive (≳5 ×

1014M⊙) end, but the 400d

objects probe down to 1 ×

1014M⊙ for the first time at

this z and

for these scaling relations. The slopes of the scaling relations are consistent: using

Eq. (5), we measure BM − M = 1.13 ±

0.20 for the 12 M13 objects. A joint fit with the 400d clusters (BM − M = 1.46 ±

0.57) yields BM − M = 1.15 ± 0.14 and a low

, driven by our data. We note

that the logarithmic bias of b = 0.10 ± 0.05 for the M13 high-z clusters corresponds to

a (20 ± 10) % mass bias,

consistent with both the upper range of the 400d results and expectation from the

literature (e.g. Laganá et al. 2010; Rasia et al. 2012).

, driven by our data. We note

that the logarithmic bias of b = 0.10 ± 0.05 for the M13 high-z clusters corresponds to

a (20 ± 10) % mass bias,

consistent with both the upper range of the 400d results and expectation from the

literature (e.g. Laganá et al. 2010; Rasia et al. 2012).

Calculating the Hogg et al. (2010, H10)

likelihood which Mahdavi et al. (2013) use, we

find  and intrinsic scatter σint consistent with zero, confirming

our above results. If we, however, repeating our fits from Fig. 1 with the H10 likelihood, we obtain discrepant results which

highlight the differences between the various regression algorithms (see Sect. 2.6)6.

and intrinsic scatter σint consistent with zero, confirming

our above results. If we, however, repeating our fits from Fig. 1 with the H10 likelihood, we obtain discrepant results which

highlight the differences between the various regression algorithms (see Sect. 2.6)6.

CL 1524+0957 at z =

0.52 is the only cluster the 400d and M13 samples share. Denoted by a

black diamond in Fig. 3, its masses from the M13

lensing and hydrostatic analyses blend in with the MMT 400d clusters. If it were

included in the  –

– relation, it

would not significantly alter the best fit, but we caution that different analysis

methods have been employed, e.g. M13 reporting aperture lensing masses based on the

ζc statistics.

relation, it

would not significantly alter the best fit, but we caution that different analysis

methods have been employed, e.g. M13 reporting aperture lensing masses based on the

ζc statistics.

Comparison with Jee et al. (2011) results:

Jee et al. (2011, J11) studied 14 very massive and distant clusters

(0.83

<z<

1.46) and found their WL and hydrostatic masses

and

and

to agree well,

similar to our results. However, they caution that their

to agree well,

similar to our results. However, they caution that their

were obtained

by extrapolating a singular isothermal sphere profile. Because we doubt that the

Chandra-based Vikhlinin et al.

(2006) model reliably describes the ICM out to such large radii, we refrain

from deriving

were obtained

by extrapolating a singular isothermal sphere profile. Because we doubt that the

Chandra-based Vikhlinin et al.

(2006) model reliably describes the ICM out to such large radii, we refrain

from deriving  . Nevertheless,

we notice that our the J11 samples not only shows similar

. Nevertheless,

we notice that our the J11 samples not only shows similar

than our most

massive clusters, but also contains the only two 400d clusters exceeding the redshift of

CL 0230+1836, CL 0152−1357

at z = 0.83

and CL 1226+3332 at z =

0.89. Their planned re-analysis will improve the leverage of our

samples at the high-z end.

than our most

massive clusters, but also contains the only two 400d clusters exceeding the redshift of

CL 0230+1836, CL 0152−1357

at z = 0.83

and CL 1226+3332 at z =

0.89. Their planned re-analysis will improve the leverage of our

samples at the high-z end.

Comparison with Foëx et al. (2012) results:

in the middle panel of Fig. 3, we compare our

results to 11 clusters from

the EXCPRES XMM-Newton sample, analysed by Foëx et al. (2012, F12) and located at a similar redshift range

(0.41 ≤ z ≤

0.61) as the bulk of our sample. Selected to be representative of the

cluster population at z ≈

0.5, these objects have been studied with XMM-Newton

in X-rays and CFHT/Megacam in the optical. Foëx

et al. (2012) explicitly quote hydrostatic and lensing masses within their

respective radii; thus we also show the  –

– . Again, the more massive of

our clusters resemble the F12 sources, with the 400d MMT sample extending towards lower

masses. Indeed, F12 study two clusters which are part of our sample: these, CL 1002+3253

at z = 0.42

and CL 1120+4318 at z =

0.60 mark their lowest lensing mass objects. At similar

. Again, the more massive of

our clusters resemble the F12 sources, with the 400d MMT sample extending towards lower

masses. Indeed, F12 study two clusters which are part of our sample: these, CL 1002+3253

at z = 0.42

and CL 1120+4318 at z =

0.60 mark their lowest lensing mass objects. At similar

on either sides

of the best-fit 400d scaling relation, their inclusion with the quoted masses would have

no immediate effect on its slope, but slightly increase its scatter.

on either sides

of the best-fit 400d scaling relation, their inclusion with the quoted masses would have

no immediate effect on its slope, but slightly increase its scatter.

Bearing in mind that Fig. 3 (middle panel) compares quantities measured at different radii, we notice that the significantly flat best fit regression line to the F12 cluster masses, showing a larger dispersion in hydrostatic than in WL masses, as opposed to the 400d MMT clusters. The comparisons in Fig. 3 underscore that while being broadly compatible with each other, different studies are shaped by the fine details of their sample selection and analysis methods. We will conduct a more detailed comparison between our results and the ones of Foëx et al. (2012) and Mahdavi et al. (2013) once we re-analysed the CFHT/Megacam of the three overlapping clusters, having already shown the MMT and CFHT Megacams to produce consistent lensing catalogues (Paper II).

5.2. The  –

– relation

relation

The right panel of Fig. 3 investigates the scaling

behaviour of  with

YX by comparing the 400d MMT clusters to

the z>

0.35 clusters from M137. The

difference between the two samples is more pronounced than in the left panel, with only

the low-mass end of the M13 sample, including CL 1524+0957, overlapping with our clusters.

None of the 400d MMT clusters deviates significantly from the M500–YX relation

applied by V09a in the derivation of the

with

YX by comparing the 400d MMT clusters to

the z>

0.35 clusters from M137. The

difference between the two samples is more pronounced than in the left panel, with only

the low-mass end of the M13 sample, including CL 1524+0957, overlapping with our clusters.

None of the 400d MMT clusters deviates significantly from the M500–YX relation

applied by V09a in the derivation of the  masses we

used. The V09a M500–YX relation

based on Chandra data for low-z clusters (Vikhlinin et al. 2006) is in close agreement to the M13 result for their

complete sample, as well as the widely used Arnaud et al.

(2010)M500–YX relation. For

the latter as well as V09a we show the version with a slope fixed to the self-similar

expectation of B = 3

/ 5. The best fit to the M13 z>

0.35 essentially yields the same slope as the complete sample

(B = 0.55 ±

0.09 compared to BH10 = 0.56 ± 0.07, calculated with the

H10 method). The higher normalisation for the high-z subsample can be likely

explained as Malmquist bias due to the effective higher mass limit in the M13 sample

selection. The incompatibility of the least massive MMT clusters with this fit highlights

that we sample lower mass clusters, which, at the same redshift, are likely to have

different physical properties.

masses we

used. The V09a M500–YX relation

based on Chandra data for low-z clusters (Vikhlinin et al. 2006) is in close agreement to the M13 result for their

complete sample, as well as the widely used Arnaud et al.

(2010)M500–YX relation. For

the latter as well as V09a we show the version with a slope fixed to the self-similar

expectation of B = 3

/ 5. The best fit to the M13 z>

0.35 essentially yields the same slope as the complete sample

(B = 0.55 ±

0.09 compared to BH10 = 0.56 ± 0.07, calculated with the

H10 method). The higher normalisation for the high-z subsample can be likely

explained as Malmquist bias due to the effective higher mass limit in the M13 sample

selection. The incompatibility of the least massive MMT clusters with this fit highlights

that we sample lower mass clusters, which, at the same redshift, are likely to have

different physical properties.

The YX proxy is the X-ray equivalent to the integrated pressure signal YSZ seen by SZ observatories. Observations confirm a close YX–YSZ correlation, with measured departures from the 1:1 slope considered inconclusive (Andersson et al. 2011; Rozo et al. 2012). Performing a cursory comparison with SZ observations, we included in Fig. 2A data for three z> 0.35 clusters from High et al. (2012) (dashed uncertainty bars), taken from their Fig. 6. The abscissa values for the High et al. (2012) clusters (SPT-CL J2022−6323, SPT-CL J2030−5638, and SPT-CL J2135−5726) show masses based on YSZ, derived from South Pole Telescope SZ observations (Reichardt et al. 2013). The Mwl are derived from observations with the same Megacam instrument we used for the 400d clusters, but after its transfer to the Magellan Clay telescope at Las Campanas Observatory, Chile. In good agreement with zero bias, the High et al. (2012) clusters are consistent with some of the lower mass 400d clusters. This result suggests that the YX–YSZ equivalence might hold once larger samples at high z and low masses will become available.

6. Summary and conclusions

In this article, we analysed the scaling relation between WL and X-ray masses for 8 galaxy clusters drawn from the 400d sample of X-ray-luminous 0.35 ≤ z ≤ 0.89 clusters. WL masses were measured from the Israel et al. (2012) MMT/Megacam data, and X-ray masses were based on the V09a Chandra analysis. We summarise our main results as follows:

-

1.

We probe the WL–X-ray mass scaling relation,in an unexplored region of the parameter spacefor the first time: the z ~ 0.4–0.5 redshift range, down to1 × 1014M⊙.

-

2.

Using several X-ray mass estimates, we find the WL and X-ray masses to be consistent with each other. Most of our clusters are compatible with the MX = Mwl line.

-

3.

Assuming the Mwl not to be significantly biased, we do not find evidence for a systematic underestimation of the X-ray masses by ~40%, as suggested as a possible solution to the discrepancy between the Planck CMB constraints on Ωm and σ8 (the normalisation of the matter power spectrum) and the Planck SZ cluster counts (Planck Collaboration XX 2014). While our results favour a small WL-X-ray mass bias, they are consistent with both vanishing bias and the ~20% favoured by studies of non-thermal pressure support.

-

4.

For the mass-mass scaling relations involving Mwl, we observe a surprisingly low scatter

, although we use only

stochastic uncertainties and allow for correlated errors via a Monte Carlo method.

Because the errors in Mwl are largely determined by the

intrinsic WL shape noise σε, we however

deem a drastic overestimation unlikely (Sect. 4.2). For the scaling relations involving MG,

however, we observe a large scatter, contrary to Okabe et al. (2010b) and M13.

, although we use only

stochastic uncertainties and allow for correlated errors via a Monte Carlo method.

Because the errors in Mwl are largely determined by the

intrinsic WL shape noise σε, we however

deem a drastic overestimation unlikely (Sect. 4.2). For the scaling relations involving MG,

however, we observe a large scatter, contrary to Okabe et al. (2010b) and M13. -

5.

Looking in detail, there are intriguing indications for a mass-dependence of the WL-X-ray mass ratios of our relatively low-mass z ~ 0.4–0.5 clusters. We observe a mass bias in the low–Mwl mass bin at the ~2σ level when splitting the sample at log (Mpiv/M⊙) = 14.5 This holds for the masses V09a report based on the YX, TX, and MG proxies.

The discrepant temperatures Chandra and XMM-Newton measure in clusters (Nevalainen et al. 2010; Schellenberger et al. 2012) could provide a possible avenue to reconcile Planck cluster properties with the Planck cosmology.

We thoroughly investigate possible causes for the mass-dependent bias and tight scaling

relations. First (Sect. 4.1), we confirm that by using

a mass-concentration relation instead of directly fitting c200 from WL, we

already significantly reduced the bias due to conversion from r200 to

r500. We emphasise that, on average, the NFW

shear profile represents a suitable fit for the cluster population (cf. Okabe et al. 2013). Measuring Mhyd within

induces

correlation between the data points in Fig. 1. Removing

this correlation by plotting both masses within a fixed physical radius, we still find small

scatter (Sect. 4.2).

induces

correlation between the data points in Fig. 1. Removing

this correlation by plotting both masses within a fixed physical radius, we still find small

scatter (Sect. 4.2).

We notice that the mass range occupied by the Mwl exceeds the X-ray mass ranges.

Partially, this higher WL mass range can be explained by the correction for dilution by

member galaxies, which could be applied only where colour information was available (Paper

II). Coincidentally, this is the case for the more massive half of the MMT sample in terms

of Mwl, thus boosting the range of measured WL

masses (Sect. 4.3). This result underscores the

importance of correcting for the unavoidable inhomogeneities in WL data due to the demanding

nature of WL observations (cf. Applegate et al. 2014).

We find no further indications for biases via the WL analysis. Furthermore the tight scaling

precludes strong redshift effects, and we find that our small MMT subsample is largely

representative of the complete sample of 36 clusters, judging from the MY–MT relation (Sect.

4.4). For the MY–MG and

MT–MG relations,

significant scatter ( ) is

present in the larger sample. The former relation also shows indications for a significant

bias of MY ≈

1.15MG.

) is

present in the larger sample. The former relation also shows indications for a significant

bias of MY ≈

1.15MG.

Weak lensing and hydrostatic masses for the 400d MMT clusters are in good agreement with

the z>

0.35 part of the Mahdavi et al.

(2013) sample and the  –

– relation

derived from it (Sect. 5.1). The M13 and Foëx et al. (2012) samples include three 400d clusters

with CFHT WL masses. These clusters neither point to significantly higher scatter nor to a

less mass-dependent bias (Fig. 3). We are planning a

re-analysis of the CFHT data, having demonstrated in Paper II that lensing catalogues from

MMT and CFHT are nicely compatible. Such reanalysis is going to be helpful to identify more

subtle WL analysis effects potentially responsible for the steep slopes and tight

correlation of WL and X-ray masses.

relation

derived from it (Sect. 5.1). The M13 and Foëx et al. (2012) samples include three 400d clusters

with CFHT WL masses. These clusters neither point to significantly higher scatter nor to a

less mass-dependent bias (Fig. 3). We are planning a

re-analysis of the CFHT data, having demonstrated in Paper II that lensing catalogues from

MMT and CFHT are nicely compatible. Such reanalysis is going to be helpful to identify more

subtle WL analysis effects potentially responsible for the steep slopes and tight

correlation of WL and X-ray masses.

An alternative explanation are intrinsic differences in the low-mass cluster population. That the 400d MMT sample probes to slightly lower masses (1 × 1014M⊙) than M13 or F12 becomes especially obvious from the Mwl–YX relation (Fig. 3, Sect. 5.2). Because the 400d sample is more representative of the z ~ 0.4–0.5 cluster population, it is likely to contain more significant mergers relative to the cluster mass, skewing mass estimates (Sect. 4.5). Hence, the 400d survey might be the first to see the onset of a mass regime in which cluster physics and substructure lead the WL-X-ray scaling to deviate from what is known at higher masses. Remarkably, Giles et al. (2014) are finding a different steep slopes in their low-mass WL-X-ray scaling analysis. Detailed investigations of how their environment shapes clusters like CL 1416+4446 might be necessary to improve our understanding of the cluster population to be seen by future cosmology surveys. Analysis systematics might also behave differently at lower masses. A turn for WL cluster science towards lower mass objects, e.g. through the completion of the 400d WL sample, will help addressing the question of evolution in lensing mass scaling relations.

Note added in proof. After this paper was accepted, another paper (von der Linden et al. 2014b) appeared as submitted, pointing at the combined effects of hydrostatic mass bias and calibration systematics. The cross calibration effect on cosmological parameter constraints is currently being tested directly by Schellenberger et al. (in prep.). Rozo et al. (2014a,b) review and cross-calibrate the various scaling relations involved. Alternatively, Burenin (2013) suggested additional massive neutrino species.

Online material

Appendix A: Further scaling relations and tests

|

Fig. A.1 Lensing mass – X-ray luminosity relation. The M–LX

relation is shown, for both |

Appendix A.1: The LX–M relation

To better assess the consistency of our weak lensing masses with the Vikhlinin et al. (2009a) results, we compare them

to the LX–MY-relation

derived by V09a using the  masses

of their low-z cluster sample. Figure A.1 inverts this relation by showing the

masses

of their low-z cluster sample. Figure A.1 inverts this relation by showing the

masses as a function of the

0.5–2.0 keVChandra

luminosities measured by V09a. Statistical uncertainties in the

Chandra fluxes and, hence, luminosities are negligible for our

purposes. We calculate the expected 68 % confidence ranges in mass for a given luminosity by inverting

the scatter in LX at a fixed MY as given

in Eq. (22) of V09a. For two fiducial redshifts, z = 0.40 and

z =

0.80, spanning the unevenly populated redshift range of the eight

clusters, the M–LX relations and their expected

scatter are shown in Fig. A.1. Small filled

triangles in Fig. A.1 show the

masses as a function of the

0.5–2.0 keVChandra

luminosities measured by V09a. Statistical uncertainties in the

Chandra fluxes and, hence, luminosities are negligible for our

purposes. We calculate the expected 68 % confidence ranges in mass for a given luminosity by inverting

the scatter in LX at a fixed MY as given

in Eq. (22) of V09a. For two fiducial redshifts, z = 0.40 and

z =

0.80, spanning the unevenly populated redshift range of the eight

clusters, the M–LX relations and their expected

scatter are shown in Fig. A.1. Small filled

triangles in Fig. A.1 show the

masses from

which V09a derived the LX–M relation. Our 8 MMT

clusters are nicely tracing the distribution of the overall sample of 36 clusters

(open triangles).

masses from

which V09a derived the LX–M relation. Our 8 MMT

clusters are nicely tracing the distribution of the overall sample of 36 clusters

(open triangles).

As an important step in the calculation of the mass function, these authors show that their procedure is able to correct for the Malmquist bias even in the presence of evolution in the LX–M

relation, which they include in the model. We emphasise that the Malmquist bias correction – which is not included here – applied by V09a moves the clusters upwards in Fig. A.1, such that the sample agrees with the best-fit from the low-z sample, as Fig. 12 in V09a demonstrates.

As already seen in Fig. 2, the Mwl (large symbols in Fig. A.1) and MY agree well. Thus we can conclude that the WL masses are consistent with the expectations from their LX. Finally, we remark that the higher X-ray luminosities for the some of the same clusters reported by Maughan et al. (2012) in their study of the LX–TX relation are not in disagreement with V09a, as Maughan et al. (2012) used bolometric luminosities.

Appendix A.2: Redshift scaling and cross-scaling of X-ray masses

Here we show further results mentioned in the main body of the article. Figure A.2 shows two examples of the X-ray/WL mass ratio as a function of redshift. Owing to the inhomegenous redshift coverage of our clusters, we cannot constrain a redshift evolution. All of our bias estimates are consistent with zero bias.

Table A.2 shows the fit results and bias estimates for various tests we performed modifying our default model, as well as for ancillary scaling relations. In particular, we probe the scaling behaviour of hydrostatic masses against the V09a estimates, for which we find a MY/Mhyd tentatively biased high by ~15%, while MT and MG do not show similar biases.

Appendix A.3: Choice of centre and fitting range