| Issue |

A&A

Volume 560, December 2013

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A87 | |

| Number of page(s) | 13 | |

| Section | Astrophysical processes | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201322185 | |

| Published online | 11 December 2013 | |

Magnetic field amplification in young galaxies

1

Universität Heidelberg, Zentrum für Astronomie, Institut für Theoretische

Astrophysik, Albert-Ueberle-Strasse

2, 69120

Heidelberg,

Germany

e-mail: Schober@stud.uni-heidelberg.de

2

Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Institut für

Astrophysik, Friedrich-Hund-Platz

1, 37077

Göttingen,

Germany

Received:

1

July

2013

Accepted:

7

November

2013

The Universe at present is highly magnetized, with fields of a few 10-5 G and coherence lengths greater than 10 kpc in typical galaxies like the Milky Way. We propose that the magnetic field was already amplified to these values during the formation and the early evolution of galaxies. Turbulence in young galaxies is driven by accretion, as well as by supernova (SN) explosions of the first generation of stars. The small-scale dynamo can convert the turbulent kinetic energy into magnetic energy and amplify very weak primordial seed fields on short timescales. Amplification takes place in two phases: in the kinematic phase the magnetic field grows exponentially, with the largest growth rate on the smallest nonresistive scale. In the following nonlinear phase the magnetic energy is shifted toward larger scales until the dynamo saturates on the turbulent forcing scale. To describe the amplification of the magnetic field quantitatively, we modeled the microphysics in the interstellar medium (ISM) of young galaxies and determined the growth rate of the small-scale dynamo. We estimated the resulting saturation field strengths and dynamo timescales for two turbulent forcing mechanisms: accretion-driven turbulence and SN-driven turbulence. We compare them to the field strength that is reached when only stellar magnetic fields are distributed by SN explosions. We find that the small-scale dynamo is much more efficient in magnetizing the ISM of young galaxies. In the case of accretion-driven turbulence, a magnetic field strength on the order of 10-6 G is reached after a time of 24−270 Myr, while in SN-driven turbulence the dynamo saturates at field strengths of typically 10-5 G after only 4−15 Myr. This is considerably shorter than the Hubble time. Our work can help for understanding why present-day galaxies are highly magnetized.

Key words: ISM: magnetic fields / galaxies: high-redshift / galaxies: magnetic fields / dynamo / magnetic fields / turbulence

© ESO, 2013

1. Introduction

The present-day Universe is filled with magnetic fields. Observations show that galaxies (Beck et al. 1999; Beck 2011) and stars (Donati & Landstreet 2009; Reiners 2012) are strongly magnetized, and there are also hints of weak magnetic fields in the intergalactic medium (Kim et al. 1989; Kronberg 1994; Neronov et al. 2013). The origin of these strong fields remains an unsolved problem in astrophysics.

Local spiral galaxies typically have turbulent field components of (2−3) × 10-5 G within the arms and bars, while a field of (5−10) × 10-5 G is observed in the central starburst regions. Moreover, these fields appear to be coherent on scales larger than 10 kpc, which is the same order of magnitude as the size of the galaxy. The magnetic energy in the galactic interstellar medium (ISM) is thus approximately in equipartition with the thermal energy and the energy in cosmic rays. The field in the interarm region is usually ordered and has a strength on the order of (1−1.5) × 10-5 G (Beck 2011). Also dwarf irregular galaxies have magnetic fields: however, they appear not to be ordered on large scales and have a lower strength of ≤4 × 10-6 G (Chyży et al. 2011).

New observations indicate that even highly redshifted galaxies have magnetic field strengths comparable to present-day galaxies (Bernet et al. 2008). For instance, the rotation measure, a quantity that depends on the magnetic field along the line of sight, is constant up to redshifts of roughly 5 (Hammond et al. 2012). An important tool is, moreover, the far-infrared radio correlation, which can be interpreted as a relation between the star formation rate and the synchrotron radiation of cosmic ray electrons in magnetic fields (Sargent et al. 2010; Bourne et al. 2011) and appears to be valid until z ≈ 2 (Murphy 2009). We note, however, that one expects a breakdown at higher redshift as a result of inverse Compton scattering with cosmic microwave background photons (Schleicher & Beck 2013). Observations of the intergalactic medium provide further information on primordial seed fields. Detailed analysis of the CMB temperature bispectrum using data from the Planck satellite gives an upper limit of the magnetic field strength of a few nG on the Mpc scale (Shiraishi et al. 2012). The increasing evidence of magnetic fields in highly redshifted galaxies and the intergalactic medium indicates an early generation of the magnetic fields.

Theoretically, the first seed fields might have already been generated in the very early

Universe during inflation, leading to a field strength of

B0 ≈ 10-34–10-10 G on a scale of 1 Mpc

(Turner & Widrow 1988). Another generation

mechanism are first-order phase transitions. Sigl et al.

(1997) predict a field strength of

B0 ≈ 10-29 G from the electroweak phase transition

and B0 ≈ 10-20 G from the QCD phase transition on a

scale of 10 Mpc. The correlation length of the primordial magnetic seed fields has been

shown to crucially depend on the initial properties of the field, e.g., on the amount of

magnetic helicity (Banerjee & Jedamzik 2004). We

can determine the typical strength of a statistical seed field by writing the magnetic

energy as  . Magnetic fields can be also generated as a

result of the Biermann term in the generalized Ohm’s law, which takes the different behavior

of the electron and ion fluid into account (Biermann

1950; Kulsrud & Zweibel 2008). A typical

field strength resulting from this so-called “Biermann battery” is 10-19 G

(Xu et al. 2008 ). Recently, Schlickeiser (2012) has shown that a turbulent magnetic field can be

generated in plasma fluctuations within an unmagnetized nonrelativistic medium. From this

effect we would expect typical seed fields of a few 10-10 G within the first

galaxies. Although this exceeds the resulting field strengths of other generation mechanisms

it still cannot explain the typical values in local galaxies. Thus, amplification processes

need to take place.

. Magnetic fields can be also generated as a

result of the Biermann term in the generalized Ohm’s law, which takes the different behavior

of the electron and ion fluid into account (Biermann

1950; Kulsrud & Zweibel 2008). A typical

field strength resulting from this so-called “Biermann battery” is 10-19 G

(Xu et al. 2008 ). Recently, Schlickeiser (2012) has shown that a turbulent magnetic field can be

generated in plasma fluctuations within an unmagnetized nonrelativistic medium. From this

effect we would expect typical seed fields of a few 10-10 G within the first

galaxies. Although this exceeds the resulting field strengths of other generation mechanisms

it still cannot explain the typical values in local galaxies. Thus, amplification processes

need to take place.

A very efficient mechanism to amplify weak seed fields is the small-scale or turbulent

dynamo, which converts kinetic energy from turbulence into magnetic energy by randomly

stretching and twisting the field lines. The magnetic energy grows exponentially in the

kinematic phase, while the growth rate is largest on the resistive scale (Kazantsev 1968; Subramanian 1997; Brandenburg & Subramanian

2005). There are two dimensionless parameters, which control the efficiency of this

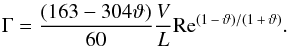

process (Schober et al. 2012b; Bovino et al. 2013): the hydrodynamic Reynolds number  (1)where V is the turbulent

velocity on the outer scale of the inertial range L and ν

is the viscosity, and the magnetic Reynolds number

(1)where V is the turbulent

velocity on the outer scale of the inertial range L and ν

is the viscosity, and the magnetic Reynolds number  (2)with η being the magnetic

resistivity. The ratio of the Reynolds numbers defines the magnetic Prandtl number

(2)with η being the magnetic

resistivity. The ratio of the Reynolds numbers defines the magnetic Prandtl number

(3)Furthermore, the dynamo growth rate depends on

the type of the turbulence ranging from incompressible Kolmogorov turbulence (Kolmogorov 1941) to highly compressible Burgers

turbulence (Burgers 1948). Eventually the magnetic

field is strong enough for back reactions to occur on the gas and the nonlinear growth sets

in (Schekochihin et al. 2002). In this phase the

magnetic energy is transported toward larger scales. Now the evolution no longer depends on

the Reynolds and Prandtl numbers, but still on the type of turbulence (Schleicher et al. 2013). The nonlinear phase comes to an end, when the

magnetic field reaches saturation on the turbulent forcing scale L.

(3)Furthermore, the dynamo growth rate depends on

the type of the turbulence ranging from incompressible Kolmogorov turbulence (Kolmogorov 1941) to highly compressible Burgers

turbulence (Burgers 1948). Eventually the magnetic

field is strong enough for back reactions to occur on the gas and the nonlinear growth sets

in (Schekochihin et al. 2002). In this phase the

magnetic energy is transported toward larger scales. Now the evolution no longer depends on

the Reynolds and Prandtl numbers, but still on the type of turbulence (Schleicher et al. 2013). The nonlinear phase comes to an end, when the

magnetic field reaches saturation on the turbulent forcing scale L.

Turbulence is driven efficiently for the first time in the history of the Universe when dark matter halos become massive enough that gas begins to cool efficiently and flows into the potential wells of dark matter halos. This leads to the formation of the first generation of stars and the subsequent build-up of galaxies. The first stars form at redhifts between 20 and 15 within primordial minihalos, which have typical masses of more than 105 solar masses (M⊙) (see e.g., Abel et al. 2002; Bromm & Larson 2004; Clark et al. 2011). In recent publications it was shown, numerically as well as semi-analytically, that during the formation of the first stars, dynamically important magnetic fields can be generated by the small-scale dynamo on short timescales (Sur et al. 2012; Turk et al. 2012; Schober et al. 2012a). According to the theory of hierarchical structure formation the first galaxies, also called protogalaxies, form at redshifts smaller than about 10 in massive dark matter halos with more than 107 M⊙ (Greif et al. 2008; Bromm et al. 2009). In young galaxies accretion as well as the penetration of supernovae (SN) shocks through the gas generate turbulence, which initiates small-scale dynamo action (Beck et al. 2012; Latif et al. 2013).

In this paper, we follow the evolution of the magnetic field in an initially weakly magnetized young galaxy. Because the true dynamical nature of the first galaxies is not well known, we adopt two simplified complementary models: a spherical galaxy as well as a disk-like system, both with constant density and temperature. We model microphysical processes, such as the diffusion of the kinematic and magnetic energy, in order to find the magnetohydrodynamical (MHD) quantities, which determine the growth rate of the small-scale dynamo. Turbulence can be generated by accretion flows into the center of the halo, for which we estimate the typical Reynolds numbers. Then we follow the evolution of the magnetic field strength in the kinematic and the nonlinear phase, until saturation on the driving scale of the turbulence is reached. Stellar feedback, in particular SN explosions, also influences the evolution of the magnetic field. On the one hand supernovae distribute stellar magnetic fields in the ISM (Rees 1987), on the other hand they drive turbulence, which again leads to dynamo action (Balsara et al. 2004). We compare the resulting magnetic field strengths from both mechanisms with the field strength gained by an accretion-driven small-scale dynamo.

The outline of the paper is as follows: in Sect. 2 we describe our model. We determine the values of viscosity and magnetic diffusivity in the ISM and estimate the evolution of SN explosions. Driving mechanisms of turbulence are discussed in general. In the last part of this section we summarize the main points of a mathematical description of magnetic field amplification by the small-scale dynamo. The kinematic phase described by the so-called Kazantsev theory and a model for the nonlinear growth phase are introduced. In Sect. 3 we present our results for the evolution of the magnetic field in the different types of models. First we discuss the generation of turbulence by accretion and the resulting efficiencies of the dynamo, i.e. the saturation magnetic field strength and the time until saturation occurs. Second, we analyze the effect of stellar feedback. We compare the efficiency of distributing stellar magnetic fields by SN with the one of the SN-driven turbulent dynamo. We draw our conclusions in Sect. 4.

2. Modeling physical processes in a protogalaxy

2.1. General aspects

The nature of young galaxies is still an active topic of research (see Bromm & Yoshida 2011, for a review). For our order of magnitude estimate of the magnetic field evolution we use a very simplified model, with the choice of parameters being motivated from numerical simulations (Greif et al. 2008; Bromm et al. 2009; Latif et al. 2013). We are interested in massive protogalactic objects at redshifts of roughly 10.

In our model we assume a mean particle density of

(4)and a temperature of

(4)and a temperature of

(5)The density as well as the temperature are,

as first approximation, constant throughout the whole galaxy. For simplicity we take a gas

into account that only consists of hydrogen, which is at the given values of

n and T mostly ionized.

(5)The density as well as the temperature are,

as first approximation, constant throughout the whole galaxy. For simplicity we take a gas

into account that only consists of hydrogen, which is at the given values of

n and T mostly ionized.

The mean shape of the primordial galaxies differs most probably from the one of present-day galaxies. Due to a significant amount of angular momentum the protogalaxies may form in a spherical way and develop a more disk-like structure at later stages. To account for the unknown typical shape, we model two extreme cases, a spherical and a disk-like galaxy, which have the same gas mass.

Spherical galaxy. In the case of a spherical protogalaxy we assume the radius to be

(6)As within this radius the density as well as

the temperature are constant we find a total mass of the baryonic gas of

(6)As within this radius the density as well as

the temperature are constant we find a total mass of the baryonic gas of

(7)

(7)

Disk-like galaxy. As our second fiducial model we use a galaxy with disk scale height of

ten percent of the radius, i.e.  (8)With the condition that the gas mass of the

disk needs to be the same as in the spherical case, the disk radius is

(8)With the condition that the gas mass of the

disk needs to be the same as in the spherical case, the disk radius is  (9)

(9)

2.2. Microphysics in the ISM

As the temperature in the primordial ISM is very high, we can assume the gas to be (at

least partially) ionized. We thus need to deal with the full plasma equations, i.e. the

continuity, the momentum and the energy equations for both the ions and the electrons.

Closures of these equations were found by Braginskii

(1965), who used the Chapman-Enskog scheme (Chapman et al. 1953). The closure is based on the assumption that the

macroscopic scale of the plasma is large compared to the mean-free path  (10)or compared to the gyro-radii of the

electrons and the ions

(10)or compared to the gyro-radii of the

electrons and the ions  (11)Here

rc = e2/(kT) is

the distance of closest particle approach with e being the elementary

charge and k the Boltzmann constant. The mass of the species is labeled

ms, where the s stands for electrons (e) or protons (p), and

c is the speed of light. Further, we use here the thermal velocity

(2kT/ms)1/2 and assume that the

temperatures of the ions and electrons are equal

(Te = Tp ≡ T).

In principle, the components of a plasma can have unequal temperatures as during plasma

heating the different fluids are heated differently. However, after a certain time

teq, an equilibrium will be reached. The electron-proton

equilibrium time can be computed by (Spitzer 1956)

(11)Here

rc = e2/(kT) is

the distance of closest particle approach with e being the elementary

charge and k the Boltzmann constant. The mass of the species is labeled

ms, where the s stands for electrons (e) or protons (p), and

c is the speed of light. Further, we use here the thermal velocity

(2kT/ms)1/2 and assume that the

temperatures of the ions and electrons are equal

(Te = Tp ≡ T).

In principle, the components of a plasma can have unequal temperatures as during plasma

heating the different fluids are heated differently. However, after a certain time

teq, an equilibrium will be reached. The electron-proton

equilibrium time can be computed by (Spitzer 1956)

(12)where Zs is the

charge of species s, Ts,0 its initial temperature and the

Coulomb logarithm is defined by

(12)where Zs is the

charge of species s, Ts,0 its initial temperature and the

Coulomb logarithm is defined by  (13)If we assume Te,0

and Tp,0 to be extremely different, e.g.,

Te,0 = 103 Tp,0, the

typical teq for our model is on the order of 440 yr. It will

be shown later that this is way below the typical dynamo timescales, which can be up to

many Myr. Thus, the electron and the proton temperature can be assumed to be equal in our

calculation.

(13)If we assume Te,0

and Tp,0 to be extremely different, e.g.,

Te,0 = 103 Tp,0, the

typical teq for our model is on the order of 440 yr. It will

be shown later that this is way below the typical dynamo timescales, which can be up to

many Myr. Thus, the electron and the proton temperature can be assumed to be equal in our

calculation.

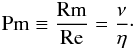

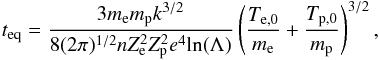

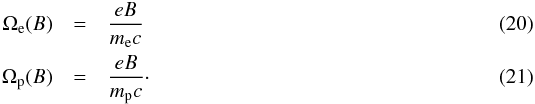

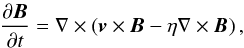

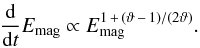

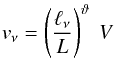

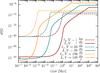

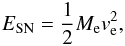

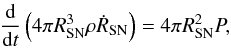

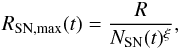

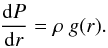

A comparison of the length scales (10) and (11) in our model can be found in Fig. 1. When the gyro-radius becomes smaller than the mean-free path, the magnetic field dominates the dynamics of the plasma, i.e. it becomes “magnetized”. In our model the electron fluid becomes magnetized at a magnetic field strength of roughly 10-12 G, the ion fluid at 10-10 G.

|

Fig. 1 Gyro-radii of electrons and ions ρe and ρp as a function of magnetic field strength compared to the typical macroscopic scale L ≈ 103 pc and the mean-free path ℓmfp. Within our fiducial case for the density and the temperature the electron fluid becomes magnetized at a magnetic field strength of roughly 10-12 G, the ion fluid at 10-10 G. |

2.2.1. Viscosity

In the transition from an unmagnetized to a magnetized state, the plasma becomes anisotropic, i.e. certain physical quantities then depend on their relative orientation to the magnetic field direction.

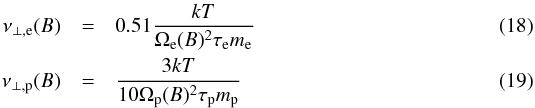

In the unmagnetized case the kinematic viscosities for electrons and ions obtained from

the Chapman-Enskog closure scheme are (Braginskii

1965) ![\begin{eqnarray} \label{nu_parallel_e} \nu_{\parallel,\mathrm{e}} & = & 0.73 \frac{\tau_\mathrm{e} k T}{m_\mathrm{e}} = 1.4\times10^{14}~\mathrm{cm}^2\,\mathrm{s}^{-1} \\[2mm] \label{nu_parallel_p} \nu_{\parallel,\mathrm{p}} & = & 0.96 \frac{\tau_\mathrm{p} k T}{m_\mathrm{p}} = 8.7\times10^{15}~\mathrm{cm}^2\,\mathrm{s}^{-1} \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/12/aa22185-13/aa22185-13-eq60.png) with the collision times for electrons and

ions

with the collision times for electrons and

ions ![\begin{eqnarray} \tau_{\mathrm{e}} & = & \frac{6 \sqrt{2} \sqrt{m_\mathrm{e}} (k T)^{3/2}}{16 \pi^{1/2} \mathrm{ln}(\Lambda) e^4 n}\\[2mm] \tau_{\mathrm{p}} & = & \frac{12 \sqrt{m_\mathrm{p}} (k T)^{3/2}}{16 \pi^{1/2} \mathrm{ln}(\Lambda) e^4 n}\cdot \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/12/aa22185-13/aa22185-13-eq61.png) In the presence of a strong magnetic field

the viscosity becomes anisotropic and one has to distinguish between the viscosity along

(parallel to) and the one perpendicular to the magnetic field lines. While the parallel

viscosity stays the same as in the unmagnetized case (e.g., Eqs. (14) and (15)), the viscosity perpendicular to the field is given by (Simon 1955)

In the presence of a strong magnetic field

the viscosity becomes anisotropic and one has to distinguish between the viscosity along

(parallel to) and the one perpendicular to the magnetic field lines. While the parallel

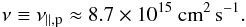

viscosity stays the same as in the unmagnetized case (e.g., Eqs. (14) and (15)), the viscosity perpendicular to the field is given by (Simon 1955)  with the gyro-frequencies

with the gyro-frequencies

Diffusion perpendicular to the magnetic

field lines is also known as “Bohm diffusion”.

Diffusion perpendicular to the magnetic

field lines is also known as “Bohm diffusion”.

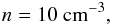

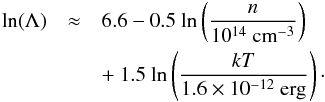

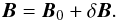

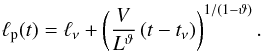

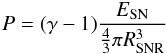

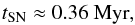

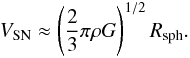

The different viscosities as a function of density are shown in Fig. 2. Note that the perpendicular viscosity only becomes

valid when the plasma is magnetized, i.e. when the gyro-radius becomes smaller than the

mean-free path. According to Fig. 1 this is the

case above a magnetic field strength of 10-11 G for the electrons and

10-9 G for the ions. Thus, the most important part of the viscosity is the

parallel one and we will ignore the perpendicular part, which decreases proportional the

1/B2, from now on. Furthermore, the viscosity of the ions

exceeds the electron viscosity by roughly two orders of magnitude. This is caused by the

fact that the ions carry the largest part of the momentum. In total, the parallel

viscosity of the ions is the crucial quantity and we will refer from now on to

(22)

(22)

|

Fig. 2 Kinematic viscosity parallel (ν∥) and perpendicular to the magnetic field lines (ν⊥) as a function of magnetic field strength B. We show the results for the electron as well as for the ion fluid. The range between 10-11 G and 10-7 G is not shown, as here the transition from the unmagnetized to a magnetized plasma takes place. |

2.2.2. Magnetic diffusivity

For the parallel conductivity the closure scheme yields (Spitzer 1956)

(23)and for the conductivity perpendicular to

the magnetic field

(23)and for the conductivity perpendicular to

the magnetic field  (24)The conductivity perpendicular to the

magnetic field lines is, contrary to the case of viscosity, no function of the magnetic

field strength. The difference between the parallel and the perpendicular component of

the conductivity is just approximately a factor of two. Usually,

σ∥ is used to determine the magnetic diffusivity

η of a plasma. We thus find

(24)The conductivity perpendicular to the

magnetic field lines is, contrary to the case of viscosity, no function of the magnetic

field strength. The difference between the parallel and the perpendicular component of

the conductivity is just approximately a factor of two. Usually,

σ∥ is used to determine the magnetic diffusivity

η of a plasma. We thus find  (25)which is also known as “Spitzer

resistivity”.

(25)which is also known as “Spitzer

resistivity”.

2.2.3. Magnetic Prandtl number

With these values of viscosity and resistivity the magnetic Prandtl number (see Eq.

(3)) is

(26)

(26)

2.3. Turbulence

2.3.1. Generation of turbulent motions by accretion

Structure formation is always associated with accretion. In order to build up the first stars and galaxies, gas flows into the potential wells of dark matter halos, where it gets compressed and cools. The potential energy released during that process in parts gets converted into turbulent kinetic energy (Klessen & Hennebelle 2010). Simulations by Greif et al. (2008) of atomic cooling halos show that two types of accretion occur: in the so-called “hot accretion” mode gas is accreted directly from the intergalactic medium, while in the “cold accretion” mode gas is cooled down and flows into the central regions of the halo at high velocities (Dekel et al. 2009; Nelson et al. 2013).

2.3.2. Generation of turbulent motions by supernova explosions

Once stars have formed, their feedback strongly influences the ISM in galaxies in terms of ionizing radiation and at later stages by SN explosions, which are especially important for the generation of turbulence.

In order to calculate the corresponding energy input, we need to estimate the rate of

SN explosions. The star formation rate (SFR) is proportional to the mass density

ρ = nm over the free-fall time

tff = (3π/(32Gρ))1/2

(Mac Low & Klessen 2004; McKee & Ostriker 2007):  (27)From the star formation rate we can

estimate the supernova rate (SNR). For this we divide the star formation rate by the

typical mass of a star that results in a SN (10 M⊙). As not

all the gas goes into stars and not all the stars are massive enough to end in a SN we

introduce an efficiency factor α:

(27)From the star formation rate we can

estimate the supernova rate (SNR). For this we divide the star formation rate by the

typical mass of a star that results in a SN (10 M⊙). As not

all the gas goes into stars and not all the stars are massive enough to end in a SN we

introduce an efficiency factor α:  (28)The number of supernovae within the whole

galaxy with a volume Vgal and a time interval

t is then given by

(28)The number of supernovae within the whole

galaxy with a volume Vgal and a time interval

t is then given by

(29)where we assume that SNR stays constant

over time. In general the SN rate is expected to change with time, however, modeling

this time dependency goes beyond the scope of this work.

(29)where we assume that SNR stays constant

over time. In general the SN rate is expected to change with time, however, modeling

this time dependency goes beyond the scope of this work.

2.4. Turbulent magnetic field amplification

2.4.1. Kinematic small-scale dynamo

The induction equation,  (30)describes the time evolution of a magnetic

field B, where v is the

velocity and η the magnetic diffusivity (25). An arbitrary magnetic field can, in general, be separated into

a mean component B0 and a fluctuating component

δB with

(30)describes the time evolution of a magnetic

field B, where v is the

velocity and η the magnetic diffusivity (25). An arbitrary magnetic field can, in general, be separated into

a mean component B0 and a fluctuating component

δB with  (31)Substituting (31) into the induction equation leads to two equations: an equation

for the large-scale field evolution and the Kazantsev equation (Kazantsev 1968; Brandenburg &

Subramanian 2005), which describes the small-scale evolution of the field.

(31)Substituting (31) into the induction equation leads to two equations: an equation

for the large-scale field evolution and the Kazantsev equation (Kazantsev 1968; Brandenburg &

Subramanian 2005), which describes the small-scale evolution of the field.

The derivation of the Kazantsev equation is based on the assumption that the

fluctuations of the magnetic field as well as the fluctuations of the velocity field are

homogeneous and isotropic even if the mean fields are not isotropic. Furthermore, the

fluctuations are assumed to be Gaussian with a zero mean and the velocity fluctuations

are thought to be δ-correlated in time. For simplicity, any helicity of

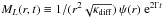

the magnetic field is neglected. With these assumptions the Kazantsev equation is (Kazantsev 1968)  (32)The eigenfunctions of this equation are

related to the longitudinal correlation function of the magnetic fluctuations

ML(r,t) by

(32)The eigenfunctions of this equation are

related to the longitudinal correlation function of the magnetic fluctuations

ML(r,t) by

. We call Γ the growth rate of the

small-scale magnetic field. The function κdiff is the

magnetic diffusion coefficient, which contains besides the magnetic diffusivity

η also a scale-dependent turbulent diffusivity. U is

called the “potential” of the Kazantsev equation. Both κdiff

and U only depend on the correlation function of the turbulent velocity

field and the magnetic diffusivity (Subramanian

1997; Schober et al. 2012b).

. We call Γ the growth rate of the

small-scale magnetic field. The function κdiff is the

magnetic diffusion coefficient, which contains besides the magnetic diffusivity

η also a scale-dependent turbulent diffusivity. U is

called the “potential” of the Kazantsev equation. Both κdiff

and U only depend on the correlation function of the turbulent velocity

field and the magnetic diffusivity (Subramanian

1997; Schober et al. 2012b).

The correlation function of the turbulent velocity field in turn depends on the

different types of turbulence, which can be distinguished by the slope of the velocity

spectrum ϑ in the inertial range, where

(33)Here δv is the velocity of

the fluctuations on the scale ℓ. The range of ϑ goes

from incompressible Kolmogorov turbulence with ϑ = 1/3 (Kolmogorov 1941) to highly compressible Burgers

turbulence with ϑ = 1/2 (Burgers

1948). The gas motions during structure formation have high Mach numbers and

thus the gas gets strongly compressed within shocks. Observations within present-day

molecular clouds by Larson (1981) show that the

slope of the turbulence spectrum is ϑ ≈ 0.38 and thus deviates from

Kolmogorov turbulence. However, other studies (Solomon

et al. 1987; Ossenkopf & Mac Low

2002; Heyer & Brunt 2004) find a

slope of roughly 0.5, whereas Roman-Duval et al.

(2011) show that the variance of ϑ is very large. For our

fiducial model we choose a value of ϑ = 0.4, which lies in between the

extremes.

(33)Here δv is the velocity of

the fluctuations on the scale ℓ. The range of ϑ goes

from incompressible Kolmogorov turbulence with ϑ = 1/3 (Kolmogorov 1941) to highly compressible Burgers

turbulence with ϑ = 1/2 (Burgers

1948). The gas motions during structure formation have high Mach numbers and

thus the gas gets strongly compressed within shocks. Observations within present-day

molecular clouds by Larson (1981) show that the

slope of the turbulence spectrum is ϑ ≈ 0.38 and thus deviates from

Kolmogorov turbulence. However, other studies (Solomon

et al. 1987; Ossenkopf & Mac Low

2002; Heyer & Brunt 2004) find a

slope of roughly 0.5, whereas Roman-Duval et al.

(2011) show that the variance of ϑ is very large. For our

fiducial model we choose a value of ϑ = 0.4, which lies in between the

extremes.

With a model for the turbulent correlation function, the Kazantsev Eq. (32) can be solved with the WKB-approximation

for very large and low Pm. This method is named after Wentzel, Kramers and Brillouin and

is used to find approximative solutions for Schrödinger-type differential equations. In

our model we are in the limit of the very high Pm, where Schober et al. (2012b) find the growth rate  (34)Here V is the typical

velocity on the largest scale of the turbulent eddies of size L. By

solving the Kazantsev Eq. (32)

numerically, Bovino et al. (2013) have recently

confirmed that Eq. (34) describes the

growth rate of the dynamo in the limit large Pm. For our fiducial model with

ϑ = 0.4 the growth rate thus scales with Re0.43.

(34)Here V is the typical

velocity on the largest scale of the turbulent eddies of size L. By

solving the Kazantsev Eq. (32)

numerically, Bovino et al. (2013) have recently

confirmed that Eq. (34) describes the

growth rate of the dynamo in the limit large Pm. For our fiducial model with

ϑ = 0.4 the growth rate thus scales with Re0.43.

2.4.2. Nonlinear small-scale dynamo

As soon as the magnetic energy is comparable to the kinetic energy of the turbulence on

the viscous scale the exponential growth comes to an end. We label this point in time

tν. The dynamo is then saturated on the

viscous scale and the nonlinear growth begins. In this phase the magnetic energy

Emag on the scale of fastest amplification

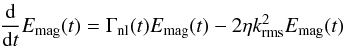

ℓa evolves as (Schekochihin et al. 2002)  (35)with the nonlinear growth rate

(35)with the nonlinear growth rate

(36)and

(36)and

(37)Schleicher

et al. (2013) find that further evaluation of Eq. (35) yields

(37)Schleicher

et al. (2013) find that further evaluation of Eq. (35) yields

(38)Thus, in the case of Kolmogorov turbulence

with ϑ = 1/3 the magnetic energy grows linear in time, while it grows

quadratically in case of Burgers turbulence with ϑ = 1/2. In our

fiducial model, where we assume ϑ = 0.4, we find

Emag ∝ t4/3 on

ℓa.

(38)Thus, in the case of Kolmogorov turbulence

with ϑ = 1/3 the magnetic energy grows linear in time, while it grows

quadratically in case of Burgers turbulence with ϑ = 1/2. In our

fiducial model, where we assume ϑ = 0.4, we find

Emag ∝ t4/3 on

ℓa.

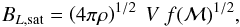

In the nonlinear phase the dynamo process shifts the magnetic energy to larger scales

with the peak scale evolving as  (39)From the peak scale to larger scales we

assume the spectrum to drop off with the Kazantsev slope. By this we can determine the

magnetic field on the forcing scale L at each point in time as

(39)From the peak scale to larger scales we

assume the spectrum to drop off with the Kazantsev slope. By this we can determine the

magnetic field on the forcing scale L at each point in time as

(40)The nonlinear growth phase comes to an end,

when saturation on the turbulent forcing scale is achieved. Now the spectrum of the

magnetic energy density scales as the one of the kinetic energy density.

(40)The nonlinear growth phase comes to an end,

when saturation on the turbulent forcing scale is achieved. Now the spectrum of the

magnetic energy density scales as the one of the kinetic energy density.

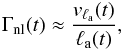

2.4.3. Saturation magnetic field strength from dynamo amplification

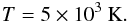

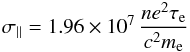

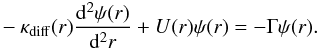

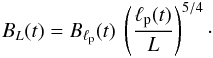

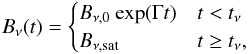

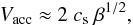

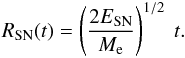

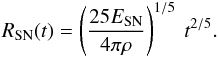

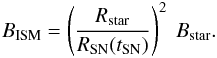

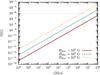

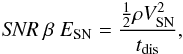

A turbulent dynamo can amplify magnetic fields at most to equipartition with the turbulent kinetic energy. However, high-resolution simulations by Federrath et al. (2011a) show that only a certain fraction f of the turbulent kinetic energy can be transformed into magnetic energy. This fraction depends on the type of forcing as well as on the Mach number ℳ. We show f(ℳ) for solenoidal and compressive forcing of turbulence in Fig. 3. Note, that the efficiency of the small-scale dynamo in case of compressive forcing peaks at a Mach number of 1, i.e. at the transition from the subsonic to the supersonic regime. At this point shocks appear, which generate solenoidal motions that are more efficient for dynamo amplification. At larger Mach numbers the efficiency decreases again and appears to become constant.

According to Federrath et al. (2010) solenoidal forcing leads to a slope of the turbulence spectrum of 0.43, while compressive forcing results in ϑ ≈ 0.47. For our fiducial model we choose the saturation efficiency of solenoidal driven turbulence, as we assume a spectrum with ϑ = 0.4.

The resulting saturation magnetic field strength on the forcing scale is

(41)where V is again the

velocity at the forcing scale. If we scale down the turbulent velocity to the viscous

scale by

(41)where V is again the

velocity at the forcing scale. If we scale down the turbulent velocity to the viscous

scale by  (42)the saturation magnetic field strength on

the viscous scale is

(42)the saturation magnetic field strength on

the viscous scale is  (43)

(43)

|

Fig. 3 Ratio of magnetic over turbulent kinetic energy at saturation f(ℳ) as a function of the Mach number ℳ. We present fits for solenoidal (solid line) and compressive forcing (dashed line) of the turbulence from the driven MHD simulations by Federrath et al. (2011a). |

2.4.4. Evolution of a magnetic field amplified by the small-scale dynamo

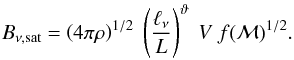

Summarizing the results of this section gives for the magnetic field evolution on the

viscous scale  (44)i.e. it grows exponentially with the rate

(34) until saturation on the viscous

scale is reached at the time tν.

(44)i.e. it grows exponentially with the rate

(34) until saturation on the viscous

scale is reached at the time tν.

The field on the turbulent forcing scale evolves as  (45)Until the time

tν the field grows exponentially in the

kinematic phase. For

t ≥ tν the dynamo is in

the nonlinear phase, in which the peak of the magnetic spectrum, which is given by Eq.

(39), is shifted toward larger scales.

The dynamo is saturated on all scales of the turbulent inertial range including the

driving scale for times

t ≥ tL.

(45)Until the time

tν the field grows exponentially in the

kinematic phase. For

t ≥ tν the dynamo is in

the nonlinear phase, in which the peak of the magnetic spectrum, which is given by Eq.

(39), is shifted toward larger scales.

The dynamo is saturated on all scales of the turbulent inertial range including the

driving scale for times

t ≥ tL.

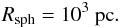

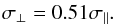

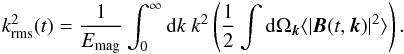

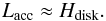

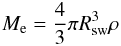

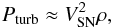

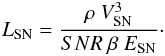

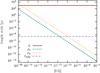

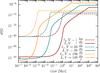

The dynamo amplification of a weak magnetic seed field of 10-20 G is shown in Fig. 4. We choose here a forcing scale of 103 pc, which is the radius of the spherical halo considered here, and three different turbulent velocities: 1 km s-1, 10 km s-1 and 100 km s-1. The microphysical quantities are taken from the calculations in the previous sections. In the figure the dashed lines represent the magnetic field strength on the viscous scale, the solid lines the one on the forcing scale.

|

Fig. 4 Evolution of the magnetic field amplified by the small-scale dynamo. The dashed lines show the evolution on the viscous scale ℓν, the solid lines the one on the forcing scale of the turbulence L. We use in this plot L = 103 pc. The different colors indicate different turbulent velocities: the red lines have velocities of 1 km s-1, the green lines 10 km s-1 and the orange lines 100 km s-1. The microphysical quantities are determined in Sect. 2.2. The viscosity is ν = 8.7 × 1015 cm2 s-1, the magnetic resistivity η = 37.8 cm2 s-1, the density is n = 10 cm-3 and the mean particle mass is m = 1.6 × 10-24 g. The initial magnetic field strength on the viscous scale in this plot is B0 = 10-20 G and the slope of the turbulence spectrum ϑ is 0.4. |

Characteristic quantities of the small-scale dynamo for accretion-driven turbulence (left hand side) and for SN-driven turbulence (right hand side).

3. Magnetic field evolution in a protogalaxy

3.1. Magnetic fields from an accretion-driven small-scale dynamo

3.1.1. Forcing turbulence by accretion

Accretion in a spherical galaxy. During the formation of the primordial halo turbulence

is generated by accretion (Birnboim & Dekel

2003; Semelin & Combes 2005; Wise et al. 2008; Vogelsberger et al. 2013). Simulations show that accretion flows have high

Mach numbers with respect to the cold gas even in the central regions of the halo (Greif et al. 2008). The characteristic forcing scale

in case of a spherical halo is the radius, where the accretion flow comes to a halt:

(46)Latif et

al. (2013) show in their simulation of a nearly isothermal protogalaxy that the

Mach number in such environment is roughly 2. Thus, the typical turbulent velocities

from accretion are on the order of

(46)Latif et

al. (2013) show in their simulation of a nearly isothermal protogalaxy that the

Mach number in such environment is roughly 2. Thus, the typical turbulent velocities

from accretion are on the order of  (47)where

cs = (γkT/m)1/2

is the sound speed and we use an adiabatic index γ of 5/3. Further, we

assume here that only a certain fraction β of the kinetic energy of the

accretion flows goes into turbulence, with β typically depending on the

density contrast between the accretion flows and the halo (Klessen & Hennebelle 2010). Simulations (Latif et al. 2013) indicate that about five percent of the kinetic

energy are in turbulent motions, i.e. β ≈ 0.05.

(47)where

cs = (γkT/m)1/2

is the sound speed and we use an adiabatic index γ of 5/3. Further, we

assume here that only a certain fraction β of the kinetic energy of the

accretion flows goes into turbulence, with β typically depending on the

density contrast between the accretion flows and the halo (Klessen & Hennebelle 2010). Simulations (Latif et al. 2013) indicate that about five percent of the kinetic

energy are in turbulent motions, i.e. β ≈ 0.05.

The resulting turbulent length scales, velocities and Reynolds numbers for a spherical galaxy are given in Table 1.

Accretion in a disk-like galaxy. In the case of a disk-like galaxy we adopt the typical

forcing scale of the turbulence by accretion flows to be the scale height

(48)We further estimate the typical velocity

for accretion flows to be on the order of the Kepler velocity in a disk

(48)We further estimate the typical velocity

for accretion flows to be on the order of the Kepler velocity in a disk  (49)If a percentage β of the

kinetic energy goes into turbulence, the resulting turbulent velocity is given by

(49)If a percentage β of the

kinetic energy goes into turbulence, the resulting turbulent velocity is given by

(50)Typical values of the length scale, the

velocity scales and the Reynolds numbers with a value of β = 0.05 are

summarized in Table 1.

(50)Typical values of the length scale, the

velocity scales and the Reynolds numbers with a value of β = 0.05 are

summarized in Table 1.

3.1.2. Accretion-driven small-scale dynamo

|

Fig. 5 Dependency of the accretion-driven small-scale dynamo mechanism on the percentage of kinetic energy that goes into turbulence β. The upper panel shows the different length scales, the middle panel the time until saturation, i.e. tν and tL, and the lower panel the saturation magnetic field strength Bsat. We plot all quantities on the viscous scale ℓν and on the turbulent forcing scale L as indicated in the figure. The solid blue lines show the results for a spherical galaxy, the dashed red lines the ones for a disk. |

Based on the discussion of the strength of magnetic seed fields in the introduction, we

assume the initial magnetic field strength on the viscous scale to be

(51)This is a rather conservative estimate.

(51)This is a rather conservative estimate.

The small-scale dynamo amplifies this seed field as soon as sufficient turbulence has

evolved. The typical growth rates in the kinematic phase are summarized in Table 1. We find 150 Myr-1 for the case of a

spherical galaxy and 1400 Myr-1 for a disk. A fraction of the magnetic energy

can be dissipated again by Ohmic diffusion. The dissipation rate on the viscous scale

ℓν is given by

(52)In our model

ΓOhm,ν is on the order of

10-12−10-10 Myr-1 and thus can be neglected compared

the growth rate of the magnetic field.

(52)In our model

ΓOhm,ν is on the order of

10-12−10-10 Myr-1 and thus can be neglected compared

the growth rate of the magnetic field.

With these relatively large growth rates, the small-scale dynamo amplification works on very short timescales. We find that in a spherical galaxy a magnetic field of 1.6 × 10-6 G and be reached on a scale of 103 pc after 270 Myr. In a disk the saturation field strength is larger by a factor of more than 2. However, the field is only on a scale of 240 pc, but it is saturated after already 24 Myr.

The efficiency of the small-scale dynamo, i.e. the saturation magnetic field strength (Bsat,ν or Bsat,L) that can be achieved and the time on which saturation occurs (tν or tL), depends strongly on the amount of turbulent kinetic energy, controlled by the parameter β (see Eqs. (47) and (50)). In our fiducial model we use β = 0.05, however, this is a rough assumption. We test how the dynamo efficiency changes when varying β in Fig. 5.

In the upper panel of Fig. 5 we show the

dependency of the viscous scale ℓν and the

forcing scale L on β. Of course L is

not effected by β, while

ℓν, which is a function of the Reynolds

number and thus of the turbulent velocity, decreases with increasing β.

The time until saturation of the dynamo, which is shown in the middle panel of Fig.

5, also decreases with increasing

β. This is a natural consequence of the larger amount of turbulent

kinetic energy. In the same way the plot in the lower panel can be understood: the more

turbulent energy, i.e. the higher β, the higher is the saturation field

strength. The magnetic field strength on the forcing scale

Bsat,L increases as

(53)

(53)

3.2. Magnetic fields from stellar feedback

3.2.1. Distributing stellar magnetic fields by supernovae

A natural source for magnetic fields in the ISM of galaxies are stellar magnetic fields that get distributed over large volumes by SN explosions. Schober et al. (2012a) have shown that the small-scale dynamo can produce strong magnetic fields during primordial star formation. Hints to dynamical important magnetic fields during the formation of the first stars also come from high-resolution numerical simulations (Federrath et al. 2011b; Turk et al. 2012; Sur et al. 2012) and further semi-analytical calculations (Schleicher et al. 2010). Thus, we expect the first and second generations of stars to be magnetized.

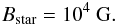

Properties of supernova candidates. We assume that a typical star that ends in a

supernova has a mass of  (54)and a radius of

(54)and a radius of

(55)with the solar mass

M⊙ = 2 × 1033 g and radius

R⊙ = 7 × 1010 cm.

(55)with the solar mass

M⊙ = 2 × 1033 g and radius

R⊙ = 7 × 1010 cm.

It is very difficult to estimate the magnetic energy in a typical population III star,

as there is not much theoretical work on that topic so far. In principle, one could

assume that a certain percentage of the total energy of the SN energy is within the

magnetic field. If the magnetic energy  equals e.g., 0.001

ESN, the stellar magnetic field would have a very high

value of Bstar = 8 × 106 G.

equals e.g., 0.001

ESN, the stellar magnetic field would have a very high

value of Bstar = 8 × 106 G.

Here, however, we use as a crude estimate for the magnetic field of population III

stars based on observations of present-day massive stars. In most high-mass stars no

magnetic fields are detected, there are few percent of stars with an enhanced magnetic

field (see Donati & Landstreet 2009). These

so-called “peculiar A or B” stars have a typical dipole field strength of

(56)We take this value as an upper limit of

magnetic fields in primordial stars, but also test lower stellar field strengths in the

following.

(56)We take this value as an upper limit of

magnetic fields in primordial stars, but also test lower stellar field strengths in the

following.

|

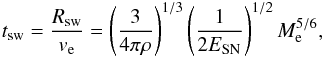

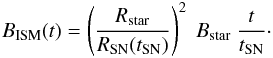

Fig. 6 The red line shows the radius of a SN shock RSN(t) as a function of time. Up to roughly 100 yr the SN shock expands freely, then the Sedov-Taylor expansion sets in. The available maximum radius for SNe RSN,max(t) as a function of time is shown for the case of a spherical halo by the blue line. This radius decreases in time, as the number of SN in the protogalactic core increases. The first SN shocks collide after a time of approximately 0.36 Myr. |

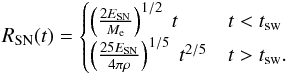

Evolution of a supernova remnant. Stars with masses above 8

M⊙ are expected to explode as a core-collapse supernova,

introducing additional turbulent energy into the ISM (Choudhuri 1998; Padmanabhan 2001).

Initially the shock front of a SN expands freely, i.e. the pressure of the surrounding

ISM is negligible. The shock velocity ve can then be

determined by  (57)where ESN is

the energy of a SN (neglecting the energy loss by neutrinos) and

Me the ejected mass. The shock radius

RSN as a function of time t is thus

(57)where ESN is

the energy of a SN (neglecting the energy loss by neutrinos) and

Me the ejected mass. The shock radius

RSN as a function of time t is thus

(58)The free expansion phase ends, when the

accumulated mass of the ISM in front of the shock is of order of

Me. This happens at the so-called sweep-up radius

Rsw defined by

(58)The free expansion phase ends, when the

accumulated mass of the ISM in front of the shock is of order of

Me. This happens at the so-called sweep-up radius

Rsw defined by

(59)with ρ being the mean

density of the ISM. The shock front reaches Rsw at a time

(59)with ρ being the mean

density of the ISM. The shock front reaches Rsw at a time

(60)which is in our model on the order of 100

yr. For t > tsw the expansion of the

supernova remnant is driven adiabatically by thermal pressure, which is known as the

Sedov-Taylor phase (Sedov 1946, 1959; Taylor

1950). We can estimate the radius of the shock in this case with

(60)which is in our model on the order of 100

yr. For t > tsw the expansion of the

supernova remnant is driven adiabatically by thermal pressure, which is known as the

Sedov-Taylor phase (Sedov 1946, 1959; Taylor

1950). We can estimate the radius of the shock in this case with  (61)where the

(61)where the

indicates a time derivative and the

pressure P is given by

indicates a time derivative and the

pressure P is given by

(62)with γ = 5/3 for adiabatic

expansion. We can solve Eq. (61) with a

simple power-law ansatz and find

(62)with γ = 5/3 for adiabatic

expansion. We can solve Eq. (61) with a

simple power-law ansatz and find

(63)Thus, the evolution of the SN remnant can

be described by (Choudhuri 1998)

(63)Thus, the evolution of the SN remnant can

be described by (Choudhuri 1998)  (64)We assume now that the energy released in a

SN explosion is ESN = 1051 erg and that about 10

percent of the mass of the progenitor star is ejected, i.e.

Me ≈ 0.1 Mstar. In our model

the SN remnants evolve as described in Eq. (64) and shown in Fig. 6 until they

collide. At later stages of shock evolution other energy loss mechanisms become

dominant. The electrons lose their energy by ionization, bremsstrahlung, synchrotron

emission and inverse Compton scattering. The latter is the most important energy loss

channel at high redshifts as here the density of the CMB photons is considerably larger

(Schleicher & Beck 2013).

(64)We assume now that the energy released in a

SN explosion is ESN = 1051 erg and that about 10

percent of the mass of the progenitor star is ejected, i.e.

Me ≈ 0.1 Mstar. In our model

the SN remnants evolve as described in Eq. (64) and shown in Fig. 6 until they

collide. At later stages of shock evolution other energy loss mechanisms become

dominant. The electrons lose their energy by ionization, bremsstrahlung, synchrotron

emission and inverse Compton scattering. The latter is the most important energy loss

channel at high redshifts as here the density of the CMB photons is considerably larger

(Schleicher & Beck 2013).

If the SNe are distributed homogeneously in the protogalaxy, each SN shell has a mean

maximum radius at the first collision of  (65)where the radius of the galaxy

R is given in Eqs. (6)

and (9) and the exponent

ξ depends on the geometry of the galaxy. In case of a spherical halo

ξ = 1/3, in case of a thin disk ξ = 1/2. The maximum

expansion radius of the SN shock is shown in Fig. 6

for the spherical case.

(65)where the radius of the galaxy

R is given in Eqs. (6)

and (9) and the exponent

ξ depends on the geometry of the galaxy. In case of a spherical halo

ξ = 1/3, in case of a thin disk ξ = 1/2. The maximum

expansion radius of the SN shock is shown in Fig. 6

for the spherical case.

By comparing (64) to (65) we find the typical time scale for SN

collisions tSN. At that point the SN bubbles fill

approximately the whole galaxy. In the spherical case we find

(66)which we take as the typical timescale for

SN collisions. Further, we use

RSN(tSN) as the typical length

scale of SN shocks.

(66)which we take as the typical timescale for

SN collisions. Further, we use

RSN(tSN) as the typical length

scale of SN shocks.

Magnetic field evolution. If now all the stellar magnetic energy is distributed into

the volume available by the SN explosion and no significant magnetic energy is left in

the stellar remnant, the resulting magnetic field strength in the ISM after the first SN

generation is  (67)Here, we assumed a spherical shape of the

galaxy and flux freezing. All the following stars will produce roughly the same amount

of magnetic energy, that is then distributed in the ISM by SN. Thus, the time evolution

of the stellar magnetic fields in galaxies can be approximated by

(67)Here, we assumed a spherical shape of the

galaxy and flux freezing. All the following stars will produce roughly the same amount

of magnetic energy, that is then distributed in the ISM by SN. Thus, the time evolution

of the stellar magnetic fields in galaxies can be approximated by

(68)The values of

RSN(tSN) and

tSN depend obviously on the SN rate, which is determined

by the parameter α as defined in (28). We obtain for the spherical case:

(68)The values of

RSN(tSN) and

tSN depend obviously on the SN rate, which is determined

by the parameter α as defined in (28). We obtain for the spherical case:

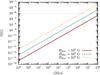

leading to a dependency of the magnetic field distributed by SN on the efficiency of

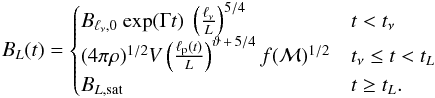

the SN rate of  (71)In Fig. 7 we show the evolution of the distributed magnetic fields for different mean

magnetic fields of the stars (104 to 102 G) and for our fiducial

case of α ≈ 0.01. Note that the case of 104 G is an upper

limit of magnetic fields in massive stars. We assume the magnetic fields of the first

stars to be considerably lower.

(71)In Fig. 7 we show the evolution of the distributed magnetic fields for different mean

magnetic fields of the stars (104 to 102 G) and for our fiducial

case of α ≈ 0.01. Note that the case of 104 G is an upper

limit of magnetic fields in massive stars. We assume the magnetic fields of the first

stars to be considerably lower.

The distribution of stellar magnetic fields by SNe explosions thus does not seem to be

important compared to the dynamo amplification in the ISM. However, after a sufficient

time the SN could contribute to the magnetic energy in the ISM. If the equipartition

field strength is roughly 10-6 G, the time after which SN distribution

becomes important is  (72)For our fiducial model we find that this

time is about 2.2 × 106 Myr in case of typical stellar field strengths of

104 G. Observations of present-day massive stars indicate that only a few

percent have these high field strengths. We thus also consider the more likely case of

lower mean stellar fields. For a mean strength of 103 G we find that a

micro-Gauss ISM field is only reached after 2.2 × 107 Myr and for a mean

strength of 102 G after 2.2 × 108 Myr. Thus, the typical

timescales of distribution of stellar magnetic fields by supernovae exceed the age of

the Universe by many orders of magnitude and this process cannot be an important

contribution for the fields in the ISM, unless the first stars were much stronger

magnetized than the present-day stars.

(72)For our fiducial model we find that this

time is about 2.2 × 106 Myr in case of typical stellar field strengths of

104 G. Observations of present-day massive stars indicate that only a few

percent have these high field strengths. We thus also consider the more likely case of

lower mean stellar fields. For a mean strength of 103 G we find that a

micro-Gauss ISM field is only reached after 2.2 × 107 Myr and for a mean

strength of 102 G after 2.2 × 108 Myr. Thus, the typical

timescales of distribution of stellar magnetic fields by supernovae exceed the age of

the Universe by many orders of magnitude and this process cannot be an important

contribution for the fields in the ISM, unless the first stars were much stronger

magnetized than the present-day stars.

In the case of a flat disk-shaped galaxy, where we assume the parameter ξ in Eq. (65) to be 1/2, the distribution of stellar magnetic fields proceeds marginally faster. Here the typical time until a field strength of 10-6 G in the ISM is reached is roughly a factor of 10 more quickly.

In reality the evolution of magnetic fields in SN shock fronts is of course more complicated. In addition to simple flux freezing further amplification processes can take place. Miranda et al. (1998) argue that in a multiple explosion scenario of structure formation (Ostriker & Cowie 1981; Miranda & Opher 1997) magnetic seed fields on the order of 10-10 G can be produced on galactic scales. In their model a Biermann battery is operating in the shock of SN explosions of the first stars as here unparallel gradients of temperature and density can be established. Recently, Beck et al. (2013) have also analyzed the magnetic field evolution in protogalaxies based on SN explosions with the cosmological N-body code GADGET. They find that a combination of SNe and subsequent magnetic field amplification leads to magnetic field strengths of a few μG, which is comparable to our results, and that the strength of seed field is coupled to the star formation process.

|

Fig. 7 Evolution of the magnetic field, when the only source of magnetic energy in the ISM are stellar magnetic fields distributed by SN explosions. The curves show the results for a spherical halo in our fiducial model with a SN efficiency of α = 0.01. We show three different mean stellar field strengths: 104 G (yellow dotted line), 103 G (green dashed line) and 102 G (solid red line). With the thin gray line we further indicate the typical saturation strength of a magnetic field generated by a small-scale dynamo. |

3.2.2. Dynamo amplification driven by SN turbulence

SN-driven dynamo in a spherical galaxy.

In Sect. 2.3 we discussed the generation of SN turbulence based on numerical simulations. Now we estimate the typical forcing scale LSN and the fluctuation velocity on that scale VSN in order to determine the Reynolds number (1) and the resulting growth rate of the kinematic small-scale dynamo (34). For that we assume that the turbulence driving in the galaxy is in equilibrium.

Then the turbulent pressure, which is roughly  (73)balances the hydrostatic pressure

P determined by

(73)balances the hydrostatic pressure

P determined by  (74)The gravitational acceleration in the

spherical case is roughly

(74)The gravitational acceleration in the

spherical case is roughly  . Solving Eq. (74) and setting it equal to Eq. (73) yields the turbulent velocity

VSN. We find in the spherical case:

. Solving Eq. (74) and setting it equal to Eq. (73) yields the turbulent velocity

VSN. We find in the spherical case:

(75)The forcing length scale can be estimated

by comparing the energy input rate with the dissipation rate:

(75)The forcing length scale can be estimated

by comparing the energy input rate with the dissipation rate:

(76)where the dissipation timescale is

(76)where the dissipation timescale is

(77)and SNR is the supernova

rate (28). Thus, we find the typical

forcing scale of SN-driven turbulence

(77)and SNR is the supernova

rate (28). Thus, we find the typical

forcing scale of SN-driven turbulence  (78)As in the case of the accretion-driven

small-scale dynamo we start with an initial magnetic field strength on the viscous scale

of

(78)As in the case of the accretion-driven

small-scale dynamo we start with an initial magnetic field strength on the viscous scale

of  (79)The turbulence driven by SN shocks makes

dynamo action possible, which leads to rapid amplification of the seed field according

to Eqs. (44) and (45). For the case of a spherical galaxy we

find that the growth rate in the kinematic amplification phase is

7.1 × 103 Myr-1. After a time of 15 Myr the saturation field

strength of 2.1 × 10-5 G is reached on the forcing scale. The characteristic

quantities of our fiducial models for the SN-driven dynamo are summarized in the right

part of Table 1.

(79)The turbulence driven by SN shocks makes

dynamo action possible, which leads to rapid amplification of the seed field according

to Eqs. (44) and (45). For the case of a spherical galaxy we

find that the growth rate in the kinematic amplification phase is

7.1 × 103 Myr-1. After a time of 15 Myr the saturation field

strength of 2.1 × 10-5 G is reached on the forcing scale. The characteristic

quantities of our fiducial models for the SN-driven dynamo are summarized in the right

part of Table 1.

|

Fig. 8 Dependency of the SN-driven small-scale dynamo mechanism on the percentage of kinetic energy that goes into turbulence β and the SN efficiency α. The upper panel shows the different length scales, the middle panel the time until saturation, i.e. tν and tL, and the lower panel the saturation magnetic field strength Bsat. We plot all quantities on the viscous scale ℓν and on the turbulent forcing scale L as indicated in the figure. The dashed-dotted blue line represents the case of a spherical galaxy with α = 0.001, the solid blue line the fiducial case of α = 0.01 and the dotted blue line the case of α = 0.1. The dashed red line shows the results for a disk-like galaxy. There are only 6 lines in the lower plot instead of 8. This results from the fact, that in the spherical case the saturation field strength on the forcing scale does not depend on α nor on β, in contrast to L and tL (see Eqs. (80) to (84)). |

As in case of accretion turbulence, the efficiency of the small-scale dynamo is sensible to the amount of kinetic energy that goes into turbulence β. Moreover, when modeling the scale of turbulence forcing we add another uncertainty namely the supernova rate, which includes the efficiency parameter α (see Eq. (28)). In our fiducial model we choose α = 0.01, but there could easily be a variation of a factor 10. The dependency of the quantities most important for the dynamo amplification on α and β in case of a spherical halo is the following:

We show the dependency of the length scales, the time until saturation and the saturation magnetic field strength on β and for different values of α in Fig. 8.

SN-driven dynamo in a disk-like galaxy. We perform the same analysis for the disk case.

Here the gravitational acceleration becomes independent of the radius for a thin disk,

i.e. Hdisk ≪ r. In that approximation we

find

g(r) ≈ 2πρGHdisk,

which leads to a turbulent velocity of

(85)The forcing scale can be determined by Eq.

(78). In case of a disk-shaped galaxy

we find that the typical forcing scale

LSN

(85)The forcing scale can be determined by Eq.

(78). In case of a disk-shaped galaxy

we find that the typical forcing scale

LSN (86)We find that the kinematic growth rate in

our fiducial model is 1.9 × 104 Myr-1. The time until saturation

on the forcing scale is then only 3.8 Myr and the saturation field strength is

2.7 × 10-5 G.

(86)We find that the kinematic growth rate in

our fiducial model is 1.9 × 104 Myr-1. The time until saturation

on the forcing scale is then only 3.8 Myr and the saturation field strength is

2.7 × 10-5 G.

In case of a disk-shaped galaxy all the quantities (79) to (84) are independent of α and β. For comparison with the spherical galaxy we show them, however, also in Fig. 8.

4. Conclusions

In this paper we model the evolution of the (turbulent) magnetic field in a young galaxy. We find that weak magnetic seed fields get amplified very efficiently by the small-scale dynamo (see Table 1), which is driven by turbulence from accretion and from supernova (SN) explosions. Dynamo theory predicts that the magnetic field is amplified in two phases: in the kinematic phase the field grows exponentially until the dynamo is saturated on the viscous scale. Then the nonlinear phase begins, where the magnetic energy is shifted toward larger scales until saturation on the turbulent forcing scale occurs.

For our fiducial models of a young galaxy we use a fixed particle density of 10 cm-3 and a temperature of 5 × 103 K. We concentrate on two different geometries: a spherical and a disk-shaped galaxy (see Sect. 2.1). We determine the viscosity of the plasma, which becomes anisotropic when the plasma becomes magnetized, and the magnetic diffusivity. Turbulence is generated by accretion flows onto the galactic core and also by SN shocks. By estimating typical driving scales and velocities we can determine the hydrodynamic and the magnetic Reynolds number. The magnetic field evolution depends strongly on the type of turbulence, which we assume to be a mixture of solenoidal and compressive modes.

For our fiducial model we find that the dynamo saturates on the largest scale in accretion-driven turbulence after a time of roughly 270 Myr in case of a spherical galaxy and after 24 Myr in case of a disk. Turbulence generated by SN shocks can amplify the magnetic field on shorter timescales, with saturation reached after 15 Myr in a spherical galaxy and 3.8 Myr in a disk. The dynamo timescale is thus comparable to the free-fall time tff = (3π/(32Gρ))1/2 ≈ 16 Myr. The age of the Universe at the onset of galaxy formation, i.e. at a redshift of 10, is roughly 470 Myr, which is larger than the dynamo timescales by factor of 2 to 120 for our four fiducial models. In the models with the longest amplification times our assumption of constant accretion and supernova rates may thus not be very precise. Nevertheless, these models provide an order of magnitude estimate of the resulting magnetic strength. In case of a disk-like galaxy we can compare the dynamo timescales further to the typical time of one rotation, which turns out to be 340 Myr when using the Kepler velocity (49). Thus, we can expect that the small-scale dynamo is saturated within less then one orbital time, the turbulent magnetic field gets ordered and an α−Ω dynamo, i.e. a galactic large-scale dynamo, sets in. The role of rotation has been analyzed for example by Kotarba et al. (2009) and Kotarba et al. (2011) in numerical simulations and is extremely important for understanding the present-day large-scale structure of galactic magnetic fields.

The magnetic field strengths predicted by our fiducial models are very high with values between 1.6 × 10-6 G and 4.3 × 10-6 G in the accretion-driven case and between 2.1 × 10-5 G and 2.7 × 10-5 G in the SN-driven case for a spherical galaxy and a disk, respectively. These field strengths are comparable with the ones observed in the local Universe, where the typical turbulent field component in present-day disk galaxies is (2−3) × 10-5 G in spiral arms and bars and up to (5−10) × 10-5 G in the central starburst regions (Beck 2011). New radio observations also detect magnetic fields in dwarf galaxies. Their field strengths, which seem to be correlated with the star formation rate, are typically a factor of three lower compared to the one in spiral galaxies (Chyży et al. 2011).

Our calculations suggest that the turbulent magnetic field of a galaxy was very high already at high redshifts. An observational confirmation of this result is very complicated. A hint toward an early generation of the turbulent magnetic field in galaxies comes from Hammond et al. (2012). They analyze the rotation measure of a huge catalog of extragalactic radio sources as a function of redshift and find that it is constant up to redshifts of 5.3, which is the maximum redshift in their dataset. A very powerful tool provides, moreover, the far-infrared – radio correlation, which relates the star formation rate to the synchrotron loss of cosmic ray electrons. It is observed to be constant up to redshifts of roughly 2 (Sargent et al. 2010; Bourne et al. 2011), but is expected to break down at a higher redshift, which depends on the star formation rate and the evolution of typical ISM densities (Schleicher & Beck 2013). With new instruments like SKA and LOFAR our knowledge about the evolution of the cosmic magnetic fields will increase.

Besides our fiducial models we analyze the effect of changing the amount of kinetic energy that goes into turbulence and find that the dynamo is more efficient with increasing turbulent energy, which is intuitively clear. Furthermore we determine the small-scale dynamo evolution for a varying supernova rate (SNR), which is important for estimating the driving scale of SN turbulence in the case of a spherical core. As expected the time until saturation increases with increasing SNR. However, the typical largest scale of the magnetic field decreases with the supernova rate.

We further estimate the effect of magnetic field enrichment in galaxies by distributing stellar fields by SN explosions. As an estimate of the magnetic energy in the first stars is very hard, we determine the expected magnetic field evolution in the ISM for three different cases. An upper limit of magnetic field strengths of the primordial stars is 104 G, which is a value observed in a the few percent of present-day massive stars that are magnetized. Distributing these mean stellar fields by SNe in the ISM, we find that a ISM field strength of 10-6 G is reached after 106 Myr, which is already longer than the Hubble time. Thus, the dynamo increases the magnetic field strength much faster.

With our model we have shown that the small-scale dynamo can amplify weak magnetic seed fields in the ISM of early galaxies on relatively short time scales compared to other evolutionary timescales. This leads to the build-up of strong magnetic fields already at very early phases of (proto)galactic evolution. Theoretical models of galaxy evolution describe a collapse of a spherical object to a disk. Comparison of the gravitational energy, 3/5GM2R-3 ≈ 1055 erg, with the magnetic energy at dynamo saturation, B2/(8π) ≈ 1053 erg, shows that the field is not strong enough to prevent to collapse. Still the magnetic field produced by the small-scale dynamo has potentially strong impact on ISM dynamics and subsequent star formation.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous referee for useful comments on our manuscript. We acknowledge funding through the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) in the Schwerpunktprogramm SPP 1573 “Physics of the Interstellar Medium” under grant KL 1358/14-1 and SCHL 1964/1-1. Moreover, we thank for financial support by the Baden-Württemberg-Stiftung via contract research (grant P-LS-SPII/18) in their program “Internationale Spitzenforschung II” as well as the DFG via the SFB 881 “The Milky Way System” in the sub-projects B1 and B2. J.S. acknowledges the support by IMPRS HD. D.R.G.S. thanks for funding via the SFB 963/1 (project A12) on “Astrophysical flow instabilities and turbulence”.

References

- Abel, T., Bryan, G. L., & Norman, M. L. 2002, Science, 295, 93 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balsara, D. S., Kim, J., Mac Low, M.-M., & Mathews, G. J. 2004, ApJ, 617, 339 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, R., & Jedamzik, K. 2004, Phys. Rev. D, 70, 123003 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A. M., Lesch, H., Dolag, K., et al. 2012, MNRAS, 422, 2152 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Beck, A. M., Dolag, K., Lesch, H., & Kronberg, P. P. 2013, MNRAS, 435, 3575 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Beck, R. 2011, Space Sci. Rev., 135 [Google Scholar]

- Beck, R., Ehle, M., Shoutenkov, V., Shukurov, A., & Sokoloff, D. 1999, Nature, 397, 324 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bernet, M. L., Miniati, F., Lilly, S. J., Kronberg, P. P., & Dessauges-Zavadsky, M. 2008, Nature, 454, 302 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biermann, L. 1950, Zeitschrift Naturforschung Teil A, 5, 65 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Birnboim, Y., & Dekel, A. 2003, MNRAS, 345, 349 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne, N., Dunne, L., Ivison, R. J., et al. 2011, MNRAS, 410, 1155 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bovino, S., Schleicher, D. R. G., & Schober, J. 2013, New J. Phys., 15, 013055 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Braginskii, S. I. 1965, Rev. Plasma Phys., 1, 205 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Brandenburg, A., & Subramanian, K. 2005, Phys. Rep., 417, 1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bromm, V., & Larson, R. B. 2004, ARA&A, 42, 79 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bromm, V., & Yoshida, N. 2011, ARA&A, 49, 373 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bromm, V., Yoshida, N., Hernquist, L., & McKee, C. F. 2009, Nature, 459, 49 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgers, J. 1948, Adv. Appl. Mech., 1, 171 [CrossRef] [MathSciNet] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, S., Cowling, T., & Társulat, M. T. 1953, The Mathematical Theory of Non-uniform Gases: An Account of the Kinetic Theory of Viscosity, Thermal Conduction and Diffusion in Gases. Prepared in Co-operation with D. Burnet (University Press) [Google Scholar]

- Choudhuri, A. R. 1998, The Physics of Fluids and Plasmas: An Introduction for Astrophysicists (Cambrigde University Press) [Google Scholar]

- Chyży, K. T., Weżgowiec, M., Beck, R., & Bomans, D. J. 2011, A&A, 529, A94 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, P. C., Glover, S. C. O., Smith, R. J., et al. 2011, Science, 331, 1040 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekel, A., Birnboim, Y., Engel, G., et al. 2009, Nature, 457, 451 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donati, J.-F., & Landstreet, J. D. 2009, ARA&A, 47, 333 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [MathSciNet] [Google Scholar]

- Federrath, C., Roman-Duval, J., Klessen, R. S., Schmidt, W., & Mac Low, M.-M. 2010, A&A, 512, A81 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Federrath, C., Chabrier, G., Schober, J., et al. 2011a, Phys. Rev. Lett., 107, 114504 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Federrath, C., Sur, S., Schleicher, D. R. G., Banerjee, R., & Klessen, R. S. 2011b, ApJ, 731, 62 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Greif, T. H., Johnson, J. L., Klessen, R. S., & Bromm, V. 2008, MNRAS, 387, 1021 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, A. M., Robishaw, T., & Gaensler, B. M. 2012 [arXiv:1209.1438] [Google Scholar]

- Heyer, M. H., & Brunt, C. M. 2004, ApJ, 615, 45 [Google Scholar]

- Kazantsev, A. P. 1968, Sov. J. Exp. Theor. Phys., 26, 1031 [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.-T., Kronberg, P. P., Giovannini, G., & Venturi, T. 1989, Nature, 341, 720 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Klessen, R. S., & Hennebelle, P. 2010, A&A, 520, A17 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Kolmogorov, A. 1941, Akademiia Nauk SSSR Doklady, 30, 301 [Google Scholar]

- Kotarba, H., Lesch, H., Dolag, K., et al. 2009, MNRAS, 397, 733 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kotarba, H., Lesch, H., Dolag, K., et al. 2011, MNRAS, 415, 3189 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kronberg, P. P. 1994, Rep. Prog. Phys., 57, 325 [Google Scholar]

- Kulsrud, R. M. & Zweibel, E. G. 2008, Rep. Prog. Phys., 71, 046901 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Larson, R. B. 1981, MNRAS, 194, 809 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Latif, M. A., Schleicher, D. R. G., Schmidt, W., & Niemeyer, J. 2013, MNRAS, 432, 668 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mac Low, M.-M., & Klessen, R. S. 2004, Rev. Mod. Phys., 76, 125 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- McKee, C. F., & Ostriker, E. C. 2007, ARA&A, 45, 565 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, O. D., & Opher, R. 1997, ApJ, 482, 573 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, O. D., Opher, M., & Opher, R. 1998, MNRAS, 301, 547 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, E. J. 2009, ApJ, 706, 482 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]