| Issue |

A&A

Volume 555, July 2013

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A53 | |

| Number of page(s) | 18 | |

| Section | Cosmology (including clusters of galaxies) | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201321256 | |

| Published online | 01 July 2013 | |

Experimental constraints on the uncoupled Galileon model from SNLS3 data and other cosmological probes

1

CEA,Centre de Saclay, Irfu/SPP,

91191

Gif-sur-Yvette,

France

e-mail:

jeremy.neveu@cea.fr

2

Center for Astrophysics and Space Astronomy, University of

Colorado, Boulder,

CO

80309-0389,

USA

3

LPNHE, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Université Paris Diderot,

CNRS-IN2P3, 4 place

Jussieu, 75252

Paris Cedex 05,

France

4

Laboratoire de Physique Théorique d’Orsay, Bâtiment 210,

Université Paris-Sud 11, 91405

Orsay Cedex,

France

5

𝒢ℝεℂ𝒪, Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris, UMR 7095-CNRS, Université Pierre et Marie

Curie-Paris 6, 98bis boulevard

Arago, 75014

Paris,

France

Received:

7

February

2013

Accepted:

25

April

2013

Aims. The Galileon model is a modified gravity theory that may provide an explanation for the accelerated expansion of the Universe. This model does not suffer from instabilities or ghost problems (normally associated with higher-order derivative theories), restores local General Relativity – thanks to the Vainshtein screening effect – and predicts late-time acceleration of the expansion.

Methods. We derive a new definition of the Galileon parameters that allows us to avoid having to choose initial conditions for the Galileon field. We tested this model against precise measurements of the cosmological distances and the rate of growth of cosmic structures.

Results. We observe a weak tension between the constraints set by growth data and those from distances. However, we find that the Galileon model remains consistent with current observations and is still competitive with the ΛCDM model, contrary to what was concluded in recent publications.

Key words: supernovae: general / cosmology: observations / dark energy

© ESO, 2013

1. Introduction

The discovery of the accelerated expansion of the Universe (Riess et al. 1998; Perlmutter et al. 1999) led cosmologists to introduce dark energy to explain our Universe. Adding a cosmological constant (Λ) to Einstein’s General Relativity is the simplest way to interpret observational data. However, even if adding a new fundamental constant is satisfactory, the value of Λ obtained from numerous measurements results in significant fine-tuning and coincidence problems. Thus, there is theoretical motivation to find alternative explanations, such as modified gravity models.

The Galileon model is just such a formulation. It was first proposed by Nicolis et al. (2009) as a general theory involving a scalar field, hereafter called π, and a second-order equation of motion invariant under a Galilean shift symmetry (∂μπ → ∂μπ + bμ, where bμ is a constant vector). This symmetry was first noticed in braneworld theories such as the DGP model of Dvali et al. (2000). The DGP model has the advantage of providing a self-accelerating solution to explain the expansion of the Universe, but it is plagued by ghost and instability problems. Galileon theories are a generalization of the DGP model that avoid these problems. The Galileon model was derived in a covariant formalism by Deffayet et al. (2009). It was also shown that this model forms a subclass of the general tensor-scalar theories involving only up to second-order derivatives originally found by Horndeski (1974).

In a four-dimension spacetime, only five Lagrangian terms are possible when forming an equation of motion for π invariant under the Galilean symmetry. Therefore, the Galileon Lagrangian has only five parameters. In the Galileon theory, as in the DGP theory, a screening mechanism called the Vainshtein effect (Vainshtein 1972) arises near massive objects due to non-linear derivative self-couplings of the π field. These ensure that the Galileon fifth force is screened near massive objects, and preserves General Relativity on local scales where it has been experimentally tested to high precision. However, this screening is only effective below a certain distance from massive objects (the Vainshtein radius) that depends on the mass of the object and on the values of the Galileon parameters (Burrage & Seery 2010). Experimental constraints on the Galileon parameters based on local tests of gravity have been proposed by Brax et al. (2011) and Babichev et al. (2011).

Recently, the Galileon model has been tested against observational cosmological data by Appleby & Linder (2012b), Okada et al. (2013), and Nesseris et al. (2010). These authors tend to reject the Galileon model because of tensions between growth-of-structure constraints and the other cosmological probes. The evolution of the Universe in the Galileon theory is based on differential equations involving the π field, which requires one to set initial conditions, and the above studies resorted to different methods for setting these initial conditions. In this work, we avoid this problem by introducing a new parametrization of the Galileon model that renders it independent of initial conditions. Combined with theoretical constraints derived in Appleby & Linder (2012a) and De Felice & Tsujikawa (2011), we compare our model with cosmological observables, and find that the Galileon model is not significantly disfavored by current observations.

We used the most recent measurements of Type Ia supernovae (SN Ia) luminosity distances, the cosmic microwave background (CMB), and baryon acoustic oscillations (BAO). The highest-quality SN Ia sample currently available is the SNLS3 sample described in Guy et al. (2010), Conley et al. (2011), and Sullivan et al. (2011). For the CMB, we used the observables from WMAP7 (Komatsu et al. 2011) and the set of BAO distances of the BOSS analysis (Sánchez et al. 2012). The growth of structures is an important probe for distinguishing modified gravity models from standard cosmological models such as ΛCDM, so it has to be used carefully. In this work, we used fσ8(z) measurements from several surveys, corrected for the Alcock-Paczynski effect.

Section 2 provides the Galileon equations used to compute the evolution of the Universe and the theoretical constraints imposed on the Galileon field. Section 3 describes the likelihood analysis, data samples, and the computing of cosmological observables. Section 4 gives the constraints on the Galileon model derived from data, and Sect. 5 discusses these results and their implications. We conclude in Sect. 6.

2. Cosmology with Galileons

2.1. Lagrangians

The Galileon model is based on the assumption that the scalar field equation of motion is

invariant under Galilean symmetries:

∂μπ → ∂μπ + bμ,

where bμ is a constant four vector. By

imposing this symmetry, Nicolis et al. (2009)

showed that there are only five possible Lagrangian terms Li

for the Galileon model action. The covariant formulation of the Galileon Lagrangian was

derived in Deffayet et al. (2009). In this paper we

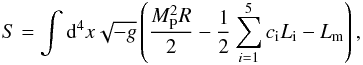

start with this covariant action with the parametrization of Appleby & Linder (2012a):  (1)with

Lm the standard-matter Lagrangian,

MP the Planck mass, R the Ricci scalar, and

g the determinant of the metric. The cis

are the arbitrary dimensionless parameters of the Galileon model that weight the different

terms. The Galileon Lagrangians have a covariant formulation derived in Deffayet et al. (2009):

(1)with

Lm the standard-matter Lagrangian,

MP the Planck mass, R the Ricci scalar, and

g the determinant of the metric. The cis

are the arbitrary dimensionless parameters of the Galileon model that weight the different

terms. The Galileon Lagrangians have a covariant formulation derived in Deffayet et al. (2009):

![\begin{eqnarray} L_1&=&M^3\pi,\quad L_2=(\nabla_\mu \pi)(\nabla^\mu \pi),\quad L_3=(\square \pi)(\nabla_\mu \pi)(\nabla^\mu \pi)/M^3 \notag \\ L_4&=&(\nabla_\mu \pi)(\nabla^\mu \pi)\left[ 2(\square \pi)^2 - 2 \pi_{;\mu\nu}\pi^{;\mu\nu} - R(\nabla_\mu \pi)(\nabla^\mu \pi)/2 \right]/M^6 \notag \\ L_5&=&(\nabla_\mu \pi)(\nabla^\mu \pi) \left[ (\square \pi)^3 - 3(\square \pi) \pi_{;\mu\nu}\pi^{;\mu\nu} +2\pi_{;\mu}\ ^{;\nu}\pi_{;\nu}\ ^{;\rho}\pi_{;\rho}\ ^{;\mu} \right.\notag \\ &&\left.-\,6 \pi_{;\mu}\pi^{;\mu\nu}\pi^{;\rho}G_{\nu\rho}\right]/M^9, \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/07/aa21256-13/aa21256-13-eq15.png) (2)where

M is a mass parameter defined as

(2)where

M is a mass parameter defined as

, where

H0 is the current value of the Hubble parameter. With this

definition the cis are dimensionless.

, where

H0 is the current value of the Hubble parameter. With this

definition the cis are dimensionless.

L2 is the usual kinetic term for a scalar field, while L3 to L5 are non-linear couplings of the Galileon field to itself, to the Ricci scalar R, and to the Einstein tensor Gμν, providing the necessary features for modifying gravity and mimicking dark energy. L1 is a tadpole term that acts as the usual cosmological constant, and may furthermore lead to vacuum instability because it is an unbounded potential term. Therefore, in the following we set c1 = 0.

Appleby & Linder (2012a) proposed

additional direct linear couplings to matter to add to the action: a linear coupling to

matter  and a derivative

coupling to matter

LG = cG∂μπ∂νπTμν/(MPM3),

which arises in some brane-world theories (see e.g. Trodden & Hinterbichler 2011), where

Tμν is the matter energy-momentum tensor.

These couplings may modify the physical origin of the accelerated expansion of the

Universe. Without coupling, the Universe is accelerated only because of the back-reaction

of the metric to the energy-momentum tensor of the scalar field, and the Galileon acts as

a dark energy component. If the Galileon is coupled directly to matter, instead, it can

give rise to accelerated expansion in the Jordan frame, while the Einstein-frame expansion

rate is not accelerating. In that case, the cosmic acceleration stems entirely from a

genuine modified gravity effect. In this work, we do not consider these optional

extensions to the theory, so the Einstein frame and Jordan frame coincide. For more

information about the Einstein and Jordan frames, see e.g. Faraoni et al. (1999).

and a derivative

coupling to matter

LG = cG∂μπ∂νπTμν/(MPM3),

which arises in some brane-world theories (see e.g. Trodden & Hinterbichler 2011), where

Tμν is the matter energy-momentum tensor.

These couplings may modify the physical origin of the accelerated expansion of the

Universe. Without coupling, the Universe is accelerated only because of the back-reaction

of the metric to the energy-momentum tensor of the scalar field, and the Galileon acts as

a dark energy component. If the Galileon is coupled directly to matter, instead, it can

give rise to accelerated expansion in the Jordan frame, while the Einstein-frame expansion

rate is not accelerating. In that case, the cosmic acceleration stems entirely from a

genuine modified gravity effect. In this work, we do not consider these optional

extensions to the theory, so the Einstein frame and Jordan frame coincide. For more

information about the Einstein and Jordan frames, see e.g. Faraoni et al. (1999).

Action 1 leads to three differential equations: two Einstein equations ((00) temporal component and (ij) spatial component) coming from the variation of the action with respect to the metric gμν, and the scalar field equation of motion from the variation of the action with respect to the π field. The equations are given explicitly in Appendix B of Appleby & Linder (2012a). With these three differential equations the evolution of the Universe and the dynamics of the field can be computed.

To solve the cosmological equations, we chose the Friedmann-Lemaître-Robertson-Walker (FLRW) metric. With no direct couplings, the functions to compute are the Hubble parameter H = ȧ/a (with a the cosmic scale factor), and x = π′/MP, with a prime denoting d/dlna (see Appleby & Linder 2012a and Sect. 2.3).

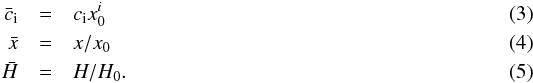

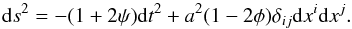

2.2. Initial conditions

To compute the solutions of the above equations, we need to set one initial condition for

x. We arbitrarily chose to define this initial condition at

z = 0, which we denote

x0 = x(z = 0).

Unfortunately, we have no prior information about the value of the Galileon field or its

derivative at any epoch. Fortunately, x0 can be absorbed by

redefining the cis as follows:

This

redefinition allows us to avoid treating x0 as an extra free

parameter of the model1. Doing so, the

This

redefinition allows us to avoid treating x0 as an extra free

parameter of the model1. Doing so, the

s

remain dimensionless, and the initial conditions are simple:

s

remain dimensionless, and the initial conditions are simple:

(6)Note that the (00)

Einstein equation could also be used as a constraint equation to fix

x0 (see Appendix A) given a set of cosmological parameters

cis,

(6)Note that the (00)

Einstein equation could also be used as a constraint equation to fix

x0 (see Appendix A) given a set of cosmological parameters

cis,  and

and

. If we were

to adapt this, we would observe a degeneracy between the parameters: the same cosmological

evolution can be obtained with small cis and a high

x0, or with high cis and a small

x0. In other words, different sets of parameters

{ci,x0} produce

the same cosmology, i.e., the same

ρπ(z), which is

undesirable. Our parametrization avoids this problem by absorbing the degeneracy between

the cis and x0 into our

. If we were

to adapt this, we would observe a degeneracy between the parameters: the same cosmological

evolution can be obtained with small cis and a high

x0, or with high cis and a small

x0. In other words, different sets of parameters

{ci,x0} produce

the same cosmology, i.e., the same

ρπ(z), which is

undesirable. Our parametrization avoids this problem by absorbing the degeneracy between

the cis and x0 into our

s.

s.

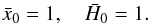

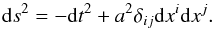

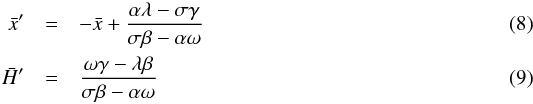

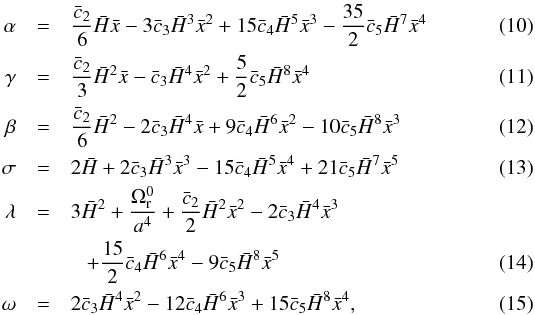

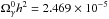

2.3. Cosmological equations

To compute cosmological evolution in the Galileon model, we assume for simplicity that

the Universe is spatially flat, in agreement with current observations. We used the

Friedmann-Lemaître-Robertson-Walker (FLRW) metric in a flat space:

(7)When writing the

cosmological equations, we can mix the (ij) Einstein equation and the π

equation of motion to obtain the following system of differential equations for

(7)When writing the

cosmological equations, we can mix the (ij) Einstein equation and the π

equation of motion to obtain the following system of differential equations for

and

and  :

:

with

with

as

derived in the formalism of Appleby & Linder

(2012a), but using our normalization for the cis. We

obtain the same equations except that the cis are changed into

as

derived in the formalism of Appleby & Linder

(2012a), but using our normalization for the cis. We

obtain the same equations except that the cis are changed into

s,

and that we have a different treatment for the initial conditions. Equations (8) and (9) depend only on the

s,

and that we have a different treatment for the initial conditions. Equations (8) and (9) depend only on the  s

and

s

and  . The

radiation energy density in Eq. (14) is

computed from the usual formula

. The

radiation energy density in Eq. (14) is

computed from the usual formula  with

Neff = 3.04 the standard effective number of neutrino

species (Mangano et al. 2002). The photon energy

density at the current epoch is given by

with

Neff = 3.04 the standard effective number of neutrino

species (Mangano et al. 2002). The photon energy

density at the current epoch is given by  (where, as usual,

h = H0/(100

km s Mpc-1) for TCMB = 2.725 K.

(where, as usual,

h = H0/(100

km s Mpc-1) for TCMB = 2.725 K.

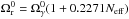

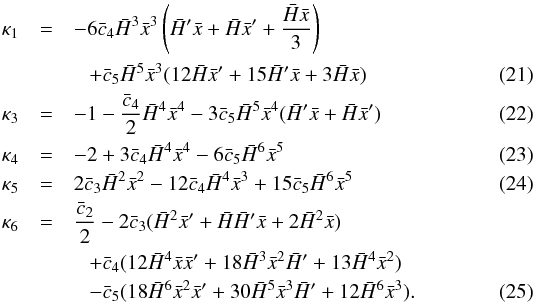

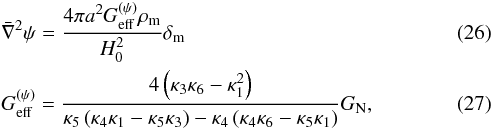

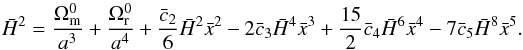

2.4. Perturbation equations

To test the Galileon model predictions for the growth of structures, we also need the

equations describing density perturbations. We followed the approach of Appleby & Linder (2012a) for the scalar

perturbation. Appleby & Linder (2012a)

performed their computation in the frame of the Newtonian gauge, for scalar modes in the

subhorizon limit, with the following perturbed metric:

(16)In this context, the

perturbed equations of the (00) Einstein equation, the (ij) Einstein equation, the

π equation of motion, and the equation of state of matter are in the

quasi-static approximation

(16)In this context, the

perturbed equations of the (00) Einstein equation, the (ij) Einstein equation, the

π equation of motion, and the equation of state of matter are in the

quasi-static approximation  where

δy = δπ/MP

is the perturbed Galileon,

where

δy = δπ/MP

is the perturbed Galileon,  ,

ρm is the matter density, and

δm = δρm/ρm

is the contrast matter density. κis are the same as in Appleby & Linder (2012a), but rewritten

following our parametrization:

,

ρm is the matter density, and

δm = δρm/ρm

is the contrast matter density. κis are the same as in Appleby & Linder (2012a), but rewritten

following our parametrization:  With

Eqs. (17) to (20), we can obtain a Poisson equation for ψ, with an

effective gravitational coupling

With

Eqs. (17) to (20), we can obtain a Poisson equation for ψ, with an

effective gravitational coupling  that

varies with time and depends on the Galileon model parameters

that

varies with time and depends on the Galileon model parameters

s:

s:

with

GN Newton’s gravitational constant. These equations can be

used to compute the growth of matter perturbations in the frame of the Galileon model (see

Sect. 3.2.4). Tensorial perturbations modes also

exist, and are studied in Sect. 2.5.4.

with

GN Newton’s gravitational constant. These equations can be

used to compute the growth of matter perturbations in the frame of the Galileon model (see

Sect. 3.2.4). Tensorial perturbations modes also

exist, and are studied in Sect. 2.5.4.

2.5. Theoretical constraints

With so many parameters, it is necessary to restrict the parameter space theoretically before comparing the model to data. The theoretical constraints arise from multiple considerations: the (00) Einstein equation, requiring positive energy densities, and avoiding instabilities in scalar and tensorial perturbations.

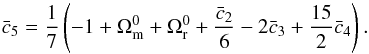

2.5.1. The (00) Einstein equation and

Because we used only the (ij) Einstein equation and the π equation of

motion to compute the dynamics of the Universe (Eqs. (8) and (9)), we are

able to use the (00) Einstein equation as a constraint on the model parameters:

(28)

More precisely, we used

this constraint both at z = 0 to fix one of our parameters and, at

other redshifts, to check the reliability of our numerical computations (see Sect. 3.1). The parameter we chose to fix at

z = 0 is

(28)

More precisely, we used

this constraint both at z = 0 to fix one of our parameters and, at

other redshifts, to check the reliability of our numerical computations (see Sect. 3.1). The parameter we chose to fix at

z = 0 is  (29)We chose to fix

(29)We chose to fix

based on the other parameters because allowing it to float introduces significant

numerical difficulties when solving Eqs. (8) and (9), since it represents

the weight of the most non-linear term in these equations. As

based on the other parameters because allowing it to float introduces significant

numerical difficulties when solving Eqs. (8) and (9), since it represents

the weight of the most non-linear term in these equations. As

is fixed

given h, our parameter space has been reduced to

is fixed

given h, our parameter space has been reduced to

and

and

.

.

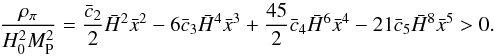

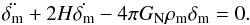

2.5.2. Positive energy density

We require that the energy density of the Galileon field be positive from

z = 0 to z = 107 (see Sect. 3.2.2 and Appendix B). At every redshift in this

range, this constraint amounts to  (30)This constraint

is not really necessary for generic scalar field models. But as we will see in the

following, it has no impact on our analysis because the other theoretical conditions

described below are stronger.

(30)This constraint

is not really necessary for generic scalar field models. But as we will see in the

following, it has no impact on our analysis because the other theoretical conditions

described below are stronger.

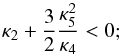

2.5.3. Scalar perturbations

As suggested by Appleby & Linder (2012a), outside the quasi-static approximation the propagation equation for δy leads to two conditions, which we again checked from z = 0 to z = 107 to ensure the viability of the linearly perturbed model:

-

1.

a no-ghost condition, which requires a positive energy for theperturbation

(31)

(31) -

2.

a Laplace stability condition for the propagation speed of the perturbed field

(32)

(32)

(33)

(33)

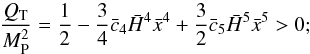

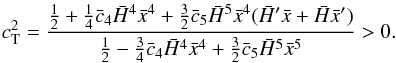

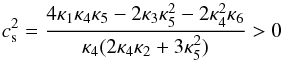

2.5.4. Tensorial perturbations

We also addrd two conditions derived by De Felice

& Tsujikawa (2011) for the propagation of tensor perturbations.

Considering a traceless and divergence-free perturbation

δgij = a2hij,

these authors obtained identical perturbed actions at second order for each of the two

polarisation modes h⊕ and h⊗.

For

h⊕![\begin{equation} \delta S_{\rm T}^{(2)}=\frac{1}{2}\int {\rm d}td^3xa^3Q_{\rm T}\left[\dot h^2_\oplus - \frac{c_{\rm T}^2}{a^2}(\nabla h_\oplus)^2 \right] \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/07/aa21256-13/aa21256-13-eq83.png) (34)with

QT and cT as defined below.

From that equation, we extracted two conditions in our parametrization that have to be

satisfied (again from z = 0 to

z = 107):

(34)with

QT and cT as defined below.

From that equation, we extracted two conditions in our parametrization that have to be

satisfied (again from z = 0 to

z = 107):

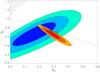

These conditions allowed us to reduce our parameter space significantly. The Galileon model contains degeneracies between the

s,

as pointed out in e.g. Barreia et al. (2012). The

above theoretical constraints and our new parametrization allowed us to break

degeneracies between the

s,

as pointed out in e.g. Barreia et al. (2012). The

above theoretical constraints and our new parametrization allowed us to break

degeneracies between the  parameters that would make it difficult to converge to a unique best-fit with current

cosmological observations. As an example, the tensorial theoretical conditions lead to a

significant reduction of the parameter space (see dark dotted regions in Fig. 2), so that closed probability contours are obtained.

parameters that would make it difficult to converge to a unique best-fit with current

cosmological observations. As an example, the tensorial theoretical conditions lead to a

significant reduction of the parameter space (see dark dotted regions in Fig. 2), so that closed probability contours are obtained.

3. Likelihood analysis method and observables

In the following, we define a scenario to be a specific realisation of the cosmological

equations for a given set of parameters  .

.

To perform the likelihood analysis, the method used in Conley et al. (2011) for the analysis of SNLS data2 was adapted to the Galileon model. For each cosmological probe, a likelihood

surface ℒ was derived by computing the χ2 for each visited

scenario:  . The way

h is treated is described in Sect. 3.2.2. Then we report the mean value of the marginalized parameters as the fit

values of

. The way

h is treated is described in Sect. 3.2.2. Then we report the mean value of the marginalized parameters as the fit

values of  and the

and the

s.

s.

3.1. Numerical computation method

To compute numerical solutions to Eqs. (8)

and (9), we used a fourth-order Runge-Kutta

method to compute  and

and  iteratively starting from the current epoch, where the initial conditions for

iteratively starting from the current epoch, where the initial conditions for

and

and  are specified (see 2.2), and propagating backwards in

time to higher z. We used a sufficiently small step size in

z to avoid numerical divergences. This is challenging because of the

significant non-linearities in our equations. To determine the step size, we therefore

required that Eq. (28), normalized by

are specified (see 2.2), and propagating backwards in

time to higher z. We used a sufficiently small step size in

z to avoid numerical divergences. This is challenging because of the

significant non-linearities in our equations. To determine the step size, we therefore

required that Eq. (28), normalized by

,

be satisfied at better than 10-5 for each step.

,

be satisfied at better than 10-5 for each step.

At each step of the computation, we also checked that all previously discussed theoretical conditions were satisfied (Eqs. (30)–(32), (35), and (36)). Cosmological scenarios that fail any of these conditions were rejected and their likelihood set to zero. The result of these requirements is shown e.g. in Fig. 2 as dark dotted regions. Equation (30) concerns a negligible number of Galileon scenarios, but the four other constraints lead to a significant reduction of the parameter space.

3.2. Data

Here we describe the cosmological observations we used in our analysis. Special care was taken to choose data that do not depend on additional cosmological assumptions.

3.2.1. Type Ia supernovae

The SN Ia data sample used in this work is the SNLS3 sample described in Conley et al. (2011). It consists of 472 well-measured supernovae from the SNLS, SDSS, HST, and a variety of low-z surveys.

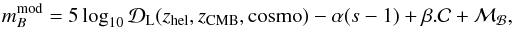

A Type Ia supernova with intrinsic stretch s and color

has a rest-frame B-band apparent magnitude

mB that can be modeled as follows:

has a rest-frame B-band apparent magnitude

mB that can be modeled as follows:

(37)where

(37)where

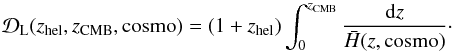

is the Hubble-constant free luminosity distance, which in a flat Universe is given by

is the Hubble-constant free luminosity distance, which in a flat Universe is given by

(38)zhel

and zCMB are the SN Ia redshift in the heliocentric and CMB

rest frames, respectively, “cosmo” represents the cosmological parameters of the model.

α and β are parameters describing the light-curve

width-luminosity and color-luminosity relationships for SNe Ia. ℳℬ is defined

as

ℳℬ = MB + 5log 10c/H0 + 25,

where MB is the rest-frame absolute

magnitude of a fiducial (

(38)zhel

and zCMB are the SN Ia redshift in the heliocentric and CMB

rest frames, respectively, “cosmo” represents the cosmological parameters of the model.

α and β are parameters describing the light-curve

width-luminosity and color-luminosity relationships for SNe Ia. ℳℬ is defined

as

ℳℬ = MB + 5log 10c/H0 + 25,

where MB is the rest-frame absolute

magnitude of a fiducial ( )

SN Ia in the B-band, and

c/H0 is expressed in

Mpc. α,β and ℳℬ are nuisance parameters that are fit

simultaneously with the cosmological parameters. As in Conley et al. (2011) and Sullivan et al.

(2011), we allowed for different ℳℬ in galaxies with the host galaxy

stellar mass below and above 1010 M⊙ to account

for relations between SN Ia brightness and host properties that are not corrected for

via the standard s and

)

SN Ia in the B-band, and

c/H0 is expressed in

Mpc. α,β and ℳℬ are nuisance parameters that are fit

simultaneously with the cosmological parameters. As in Conley et al. (2011) and Sullivan et al.

(2011), we allowed for different ℳℬ in galaxies with the host galaxy

stellar mass below and above 1010 M⊙ to account

for relations between SN Ia brightness and host properties that are not corrected for

via the standard s and  relations. When computing Type Ia supernova distance luminosities in Sect. 4, we neglect the radiation component in

relations. When computing Type Ia supernova distance luminosities in Sect. 4, we neglect the radiation component in

,

since all measurements are restricted to redshifts below 1.4 where the effects of

radiation density are negligible.

,

since all measurements are restricted to redshifts below 1.4 where the effects of

radiation density are negligible.

Systematic uncertainties must be treated carefully when using SN Ia data, because they depend on α and β and due to covariances between different supernovae. We followed the treatment of Conley et al. (2011) and Sullivan et al. (2011).

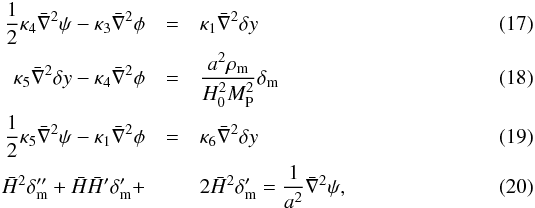

3.2.2. Cosmological microwave background

The CMB is a powerful probe to constrain the expansion history of the Universe because it gives high-redshift cosmological observables. The power spectrum provides much information on the content of the Universe and the relations between the different fluids, as long as we are able to model the thermodynamics of these fluids before recombination. The Galileon model does not modify the standard baryon-photon flux physics as long as the Galileon field does not couple directly to matter, as is assumed in this work. Thus, the usual formulae and predictions used in the standard analysis of the CMB power spectrum remain valid.

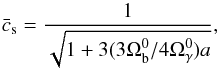

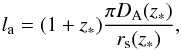

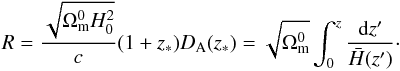

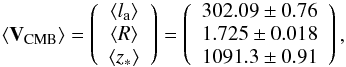

The positions of the acoustic peaks can be quantified by three observables:

{la,R,z∗}

(see e.g. Komatsu et al. 2011 and Komatsu et al. 2009), where

la is the acoustic scale related to the comoving sound

speed horizon, R is the shift parameter related to the distance between

us and the last scattering surface, and z∗ is the redshift

of the last scattering surface. These quantities are derived from the angular diameter

distance, which in a flat space is given by

(39)and from the

comoving sound speed horizon:

(39)and from the

comoving sound speed horizon:  (40)

(40) is the usual normalized sound speed in the baryon-photon fluid before recombination:

is the usual normalized sound speed in the baryon-photon fluid before recombination:

(41)where

(41)where

is the

baryon energy density parameter today.

is the

baryon energy density parameter today.

With the above definitions, the acoustic scale la is given

by  (42)and the shift parameter

R by

(42)and the shift parameter

R by  (43)z∗

is given by the fitting formula of Hu & Sugiyama

(1996):

(43)z∗

is given by the fitting formula of Hu & Sugiyama

(1996): ![\begin{eqnarray} \label{eq:zstar} &&z_*=1048\left[1+0.00124(\Omega_{\rm b}^0h^2)^{-0.738}\right] \left[1+g_1(\Omega_{\rm m}^0h^2)^{g_2}\right] \\ &&g_1=\frac{0.0783(\Omega_{\rm b}^0h^2)^{-0.238}}{1+39.5(\Omega_{\rm b}^0h^2)^{0.763}}\\ &&g_2=\frac{0.560}{1+21.1(\Omega_{\rm b}^0h^2)^{1.81}}\cdot \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/07/aa21256-13/aa21256-13-eq126.png) According

to Hu & Sugiyama (1996), formula (44) is valid for a wide range of

According

to Hu & Sugiyama (1996), formula (44) is valid for a wide range of

and

and

.

.

BAO measurements.

To compare these observables with the seven-year WMAP data (WMAP7), we followed the

numerical recipe given in Komatsu et al. (2009).

The key point of this recipe is that for each cosmological scenario,

must be minimized

over h and

must be minimized

over h and  , which appear in

Eq. (44) and in the computation of

, which appear in

Eq. (44) and in the computation of

through

through  (see Eq.

(14)).

(see Eq.

(14)).

An important feature to note is that we have to solve Eqs. (8) and (9) from a = 1 to a = 0 to compute the CMB observables. Numerically, however, we cannot reach a = 0 (z = ∞) because of numerical divergences. To avoid them, we carried out these computations up to a = 10-7 and then linearly extrapolated the value of the integral to a = 0 (for more details on the reliability of this approximation see Appendix B). Thus, the theoretical constraints of 2.5 were checked from a = 1 to a = 10-7.

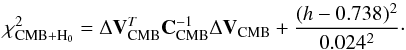

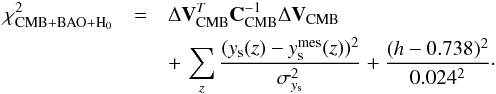

Finally, because CMB observables depend explicitly on H0, we imposed a Gaussian prior on its value, h = 0.737 ± 0.024 as measured by Riess et al. (2011) from low-redshift SNe Ia and Cepheid variables.

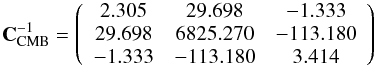

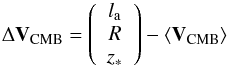

The WMAP7 recommended best-fit values of the CMB observables are

(47)with the corresponding

inverse covariance matrix:

(47)with the corresponding

inverse covariance matrix:  (48)from

Komatsu et al. (2011). As pointed out by Nesseris et al. (2010), the uncoupled Galileon model

fulfils the assumptions required in Komatsu et al.

(2009) to use these distance priors, namely a FLRW Universe with the standard

number of neutrinos and a dark energy background with negligible interactions with the

primordial Universe. Once the observables

{la,R,z∗}

were computed in a cosmological scenario, we built the difference vector:

(48)from

Komatsu et al. (2011). As pointed out by Nesseris et al. (2010), the uncoupled Galileon model

fulfils the assumptions required in Komatsu et al.

(2009) to use these distance priors, namely a FLRW Universe with the standard

number of neutrinos and a dark energy background with negligible interactions with the

primordial Universe. Once the observables

{la,R,z∗}

were computed in a cosmological scenario, we built the difference vector:

(49)and computed

the CMB contribution to the total χ2 :

(49)and computed

the CMB contribution to the total χ2 :

(50)

(50)

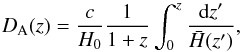

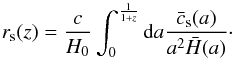

3.2.3. Baryonic acoustic oscillations

BAO distances provide information on the imprint of the comoving sound horizon after

recombination on the distribution of galaxies. The BAO observable is defined as

ys(z) = rs(zd)/DV(z),

where rs is the comoving sound horizon at the baryon drag

epoch redshift zd, and

DV(z) is the effective

distance (Eisenstein et al. 2005) given by

![\begin{equation} D_V(z)=\left[(1+z)^2D_{\rm A}^2(z)\frac{cz}{H(z)}\right]^{1/3}\cdot \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/07/aa21256-13/aa21256-13-eq148.png) (51)zd

is computed using the Eisenstein & Hu

(1998) fitting formula:

(51)zd

is computed using the Eisenstein & Hu

(1998) fitting formula: ![\begin{eqnarray} z_{\rm d}&=&\frac{1291(\Omega_{\rm m}^0h^2)^{0.251}}{1+0.659(\Omega_{\rm m}^0h^2)^{0.828}} \left[1+b_1(\Omega_{\rm b}^0h^2)^{b_2}\right] \\ b_1 &=& 0.313(\Omega_{\rm m}^0h^2)^{-0.419} \left[1+0.607(\Omega_{\rm m}^0h^2)^{0.674}\right] \\ b_2 &=& 0.238(\Omega_{\rm m}^0h^2)^{0.223} . \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/07/aa21256-13/aa21256-13-eq149.png) This

formula remains valid for a Galileon field not coupled to matter.

This

formula remains valid for a Galileon field not coupled to matter.

Therefore BAO distances depend on h and

as the

CMB observables so we followed the same recipe as previously mentioned to compute them,

including the H0 prior from Riess et al. (2011). We also made the same approximation as for the CMB to

compute rs. The minimization over h and

as the

CMB observables so we followed the same recipe as previously mentioned to compute them,

including the H0 prior from Riess et al. (2011). We also made the same approximation as for the CMB to

compute rs. The minimization over h and

was performed

independently for CMB and BAO when their individual constraints are derived and

simultaneously when combined constraints were computed.

was performed

independently for CMB and BAO when their individual constraints are derived and

simultaneously when combined constraints were computed.

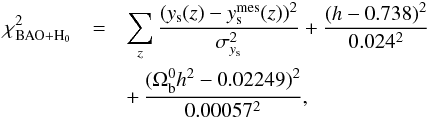

We used the dataset of distances derived from galaxy surveys as published in the SDSS-III BOSS cosmological analysis (Anderson et al. 2012 and Sánchez et al. 2012) to avoid redshift overlaps in the measurements (see Table 1).

For a cosmological constraint derived from BAO distances alone, the BAO contribution to

the total χ2 is given by  (55)where

we added a Gaussian prior on

(55)where

we added a Gaussian prior on  when dealing with

this probe alone.

when dealing with

this probe alone.

When BAO and CMB probes were combined, we computed their contributions to the

χ2 simultaneously to avoid over-counting the Hubble

constant prior. Therefore, the combined contribution is

(56)

(56)

Growth data.

Cosmological constraints on the Galileon model from the SNLS3 sample.

3.2.4. Growth rate of structures

The cosmological growth of structures is a critical test of the Galileon model, as noted by many authors (see Linder 2005 for example). It is a very discriminant constraint for distinguishing dark energy and modified gravity models. Many models can mimic ΛCDM behavior for the expansion history of the Universe, but all modify gravity and structure formation in a different manner.

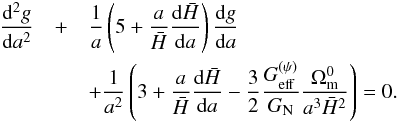

In linear perturbation theory, the growth of a matter perturbation

δm = δρm/ρm

is governed by the equation  (57)But as argued in

Linder (2005) and as used in Komatsu et al. (2009), it is better to study the

growth evolution with the function

g(a) ≡ D(a)/a ≡ δm(a)/(aδm(1)).

In the Galileon case, the Newton constant is replaced by

(57)But as argued in

Linder (2005) and as used in Komatsu et al. (2009), it is better to study the

growth evolution with the function

g(a) ≡ D(a)/a ≡ δm(a)/(aδm(1)).

In the Galileon case, the Newton constant is replaced by

as given in Eq. (27). The

g(a) is obtained by solving the following

second-order differential equation

as given in Eq. (27). The

g(a) is obtained by solving the following

second-order differential equation  (58)A

natural choice for the initial conditions is

g(ainitial) = 1 and

dg/da|ainitial = 0

(Komatsu et al. 2009), where

ainitial is

0.001 ≈ 1/(1 + z∗). We checked that our

results do not depend on this choice as long as ainitial is

taken between 10-2 and 10-5.

(58)A

natural choice for the initial conditions is

g(ainitial) = 1 and

dg/da|ainitial = 0

(Komatsu et al. 2009), where

ainitial is

0.001 ≈ 1/(1 + z∗). We checked that our

results do not depend on this choice as long as ainitial is

taken between 10-2 and 10-5.

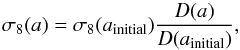

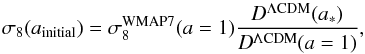

Measurements of the rate of growth of cosmic structures from redshift space distortions

can be expressed in terms of

f(a) = dlnD(a)/dlna

or fσ8(a), where

σ8 is the normalization of the matter power spectrum.

fσ8(a) is known to be

less sensitive to the overall normalization of the power spectrum model used to derive

the measurements (Song & Percival 2009).

Accordingly this is the observable we chose in this work. To predict

fσ8(a) in our analysis,

we solved Eq. (58) to obtain

g(a), from which we deduced

f(a) and D(a), and

we computed σ8(a) in the following way

(Samushia et al. 2012a):  (59)where

(59)where

(60)and

(60)and

is the present value of the CMB power spectrum normalization published by Komatsu et al. (2011) in the framework of the ΛCDM

model. Equation (60) states that the

normalization of the CMB power spectrum at decoupling is the same in the ΛCDM and

Galileon models, which is consistent with our assumption that the CMB physics is not

modified by the Galileon presence. This equation holds if

D(a) has no scale dependence, which is the case in

both models in the linear regime. Equation (59) takes into account the different growth histories since recombination in

the two models.

is the present value of the CMB power spectrum normalization published by Komatsu et al. (2011) in the framework of the ΛCDM

model. Equation (60) states that the

normalization of the CMB power spectrum at decoupling is the same in the ΛCDM and

Galileon models, which is consistent with our assumption that the CMB physics is not

modified by the Galileon presence. This equation holds if

D(a) has no scale dependence, which is the case in

both models in the linear regime. Equation (59) takes into account the different growth histories since recombination in

the two models.

However, stand-alone fσ8(a) measurements extracted from observed matter power spectra usually use a fiducial cosmology, which assumes General Relativity. This hypothesis is no longer necessary when taking into account the Alcock-Paczynski effect (Alcock & Paczynski 1979) in the power spectrum analysis. This results in joint measurements of fσ8(a) and the Alcock-Paczynski parameter F(a) ≡ c-1DA(a)H(a)/a, which are to be preferred when constraining modified gravity models (see e.g. Beutler et al. 2012 and Samushia et al. 2012b). Note that Eqs. (8) and (9) are all we need to predict F(a) in the Galileon model.

The measurements of

fσ8(z) and

F(z) used in this work are summarized in Table 2. To compare these with our model, we first solved

Eqs. (8) and (9) from a = 1 to

ainitial to obtain values of

,

F(a) and

,

F(a) and  , and then

solved Eq. (58) from

ainitial to a = 1, which provides us with

fσ8(z) predictions.

, and then

solved Eq. (58) from

ainitial to a = 1, which provides us with

fσ8(z) predictions.

Galileon model best-fit values from different data samples.

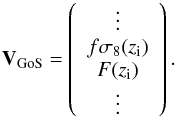

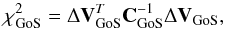

Because F(z) and

fσ8(z) measurements are

correlated, a covariance matrix CGoS was built using data

presented in Table 2. Moreover, our

fσ8 prediction relies on the WMAP7

measurement of σ8(a = 1) (Eq. (60)), so the WMAP7 experimental uncertainty

is also propagated to the diagonal and off-diagonal terms of

CGoS. Then a vector VGoS containing

all predictions at each zi was built

(61)The contribution of the

growth rate of structures to the total χ2 is then

(61)The contribution of the

growth rate of structures to the total χ2 is then

(62)with

ΔVGoS = VGoS − ⟨ VGoS ⟩,

where ⟨ VGoS ⟩ contains the measurements of Table 2.

(62)with

ΔVGoS = VGoS − ⟨ VGoS ⟩,

where ⟨ VGoS ⟩ contains the measurements of Table 2.

Note that Eq. (14) requires a value for

, and

hence in principle this equation should be simultaneously solved with the BAO and CMB

constraints using the same prior on H0. However, we found

that this has essentially no effect on our χ2. Therefore, we

set here h to the value derived from the H0

measurements of Riess et al. (2011) to accelerate

the computation.

, and

hence in principle this equation should be simultaneously solved with the BAO and CMB

constraints using the same prior on H0. However, we found

that this has essentially no effect on our χ2. Therefore, we

set here h to the value derived from the H0

measurements of Riess et al. (2011) to accelerate

the computation.

4. Results

In the following we present the results of the experimental constraints on the Galileon model derived from the cosmological probes.

4.1. SN constraints

Results from SN Ia data are presented in Fig. 2 and Table 3.

4.1.1. SN results

Despite the large number of free parameters in the model, we obtained closed

probability contours in any two-dimensional projection of the parameter space. We

observed strong correlations between the  s,

especially between

s,

especially between  and

and  .

.

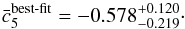

We note that the best-fit value for  is

compatible with the current constraints obtained in the ΛCDM or FWCDM models. The

is

compatible with the current constraints obtained in the ΛCDM or FWCDM models. The

s

are found to be globally of the order of ≈− 1. From the best-fit values of the

parameters, we derived the value of

s

are found to be globally of the order of ≈− 1. From the best-fit values of the

parameters, we derived the value of  using Eq. (29) and find

using Eq. (29) and find

,

including systematic uncertainties.

,

including systematic uncertainties.

In the following we discuss the impact of fixing the nuisance parameters α and β and the effect of systematics on the best-fit values.

|

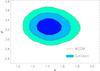

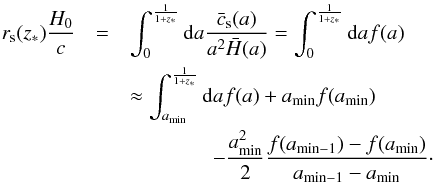

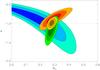

Fig. 1 Confidence contours for the SN nuisance parameters α and β when marginalizing over all other parameters of the model. Dashed red contours represent 68.3%, 95.4%, and 99.7% probability contours for the ΛCDM model. Filled blue contours are for the Galileon model. Note that they are nearly identical, the Galileon one is just 2.8% wider, which is likely due to larger steps in α and β. See Table 3 for numerical values. |

|

Fig. 2 Experimental constraints on the Galileon model from SNLS3 data alone. To

represent the four-dimensional likelihood |

|

Fig. 3 Experimental constraints on the Galileon model from WMAP7+BAO+H0 data. To

represent the four-dimensional likelihood |

4.1.2. Impact of nuisance parameters

When marginalizing over the cosmological parameters, the best-fit values of the SN

nuisance parameters α, β,

, and

, and

in the

Galileon context are identical to those published for the ΛCDM model, as shown in Fig.

1 and Table 3. This is a truly important point to note. It means that the modeling of the

SN Ia physics contained in these nuisance parameters is adequate for these two

cosmological models despite their differences.

in the

Galileon context are identical to those published for the ΛCDM model, as shown in Fig.

1 and Table 3. This is a truly important point to note. It means that the modeling of the

SN Ia physics contained in these nuisance parameters is adequate for these two

cosmological models despite their differences.

In principle, the correct method to use when analyzing SN Ia data is to scan and marginalize over the nuisance parameters. However, once the best-fit values of α and β are known, keeping them fixed to their best-fit values in any study using the same SN sample has a negligible impact on our results (see Table 3). In the Galileon case, the contour areas decrease by only 0.7% and have the same shape as in Fig. 2. For future studies with the SNLS3 sample in the ΛCDM or Galileon models, our analysis therefore demonstrates that it is reasonable to keep the nuisance parameters fixed to the values published the SNLS papers.

4.1.3. Impact of systematic uncertainties

From the results in Table 3, we note that the identified systematic uncertainties shift the best-fit values of the Galileon parameters by less than their statistical uncertainties. With systematics included, the area of the inner contours increases by about 53%. This is less than what is observed in fits to the ΛCDM or FWCDM models (103% and 80% respectively, see Conley et al. 2011).

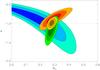

4.2. Combined CMB, BAO, and H0 constraints

The results using CMB, BAO, and H0 data are presented in Fig. 3 and Table 4.

The combined WMAP7+BAO+H0 data provide a very powerful constraint on

, but no

tighter constraints on the

, but no

tighter constraints on the  than SNe Ia alone.

than SNe Ia alone.  is, as for the SNLS3 sample, close to the current best estimates for this parameter in the

standard cosmologies, but this time with very sharp error bars competitive with the most

recent studies on other cosmological models. However, the

is, as for the SNLS3 sample, close to the current best estimates for this parameter in the

standard cosmologies, but this time with very sharp error bars competitive with the most

recent studies on other cosmological models. However, the

best-fit values are similar to those predicted with the SNLS3 sample.

best-fit values are similar to those predicted with the SNLS3 sample.

To use the WMAP7+BAO+H0 data, h and

have to be minimized

for each explored Galileon scenario. Minimized values of these parameters are collected in

the histograms of Fig. 4 for the subset of the

scenarios that fulfilled the theoretical constraints. Values for the best-fit scenarios

are reported in Table 4. For the Galileon model,

the h distribution has a mean of 0.65 with a dispersion of 0.06,

compatible with the H0 prior. The constraint on

h is slightly lower than the Riess et

al. (2011) value, but the same behavior is obtained for the ΛCDM model using the

same program and data. The central value for the

have to be minimized

for each explored Galileon scenario. Minimized values of these parameters are collected in

the histograms of Fig. 4 for the subset of the

scenarios that fulfilled the theoretical constraints. Values for the best-fit scenarios

are reported in Table 4. For the Galileon model,

the h distribution has a mean of 0.65 with a dispersion of 0.06,

compatible with the H0 prior. The constraint on

h is slightly lower than the Riess et

al. (2011) value, but the same behavior is obtained for the ΛCDM model using the

same program and data. The central value for the  distribution is

fully compatible with the WMAP7 value, for the Galileon and the ΛCDM model. However, in

the Galileon model, values below 0.22 are much more disfavored.

distribution is

fully compatible with the WMAP7 value, for the Galileon and the ΛCDM model. However, in

the Galileon model, values below 0.22 are much more disfavored.

For completeness, we present in Fig. 5 examples of

results obtained from the WMAP7+H0 and BAO+H0 probes separately. Both plots were obtained

with a minimization on h and  , but a Gaussian

prior on

, but a Gaussian

prior on  was added for the

BAO (see Eq. (55)). We used the WMAP7

constraint for that prior because Fig. 4 shows that

the Galileon model is consistent with it.

was added for the

BAO (see Eq. (55)). We used the WMAP7

constraint for that prior because Fig. 4 shows that

the Galileon model is consistent with it.

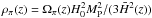

4.3. Growth-of-structure constraints

Results using growth data are presented in Fig. 6 and Table 4, and are commented on in detail in Sect. 5.

Growth data and cosmological distances provide consistent values for the

s.

The

s.

The  best-fit

value from growth data,

best-fit

value from growth data,  , is

below that from the other probes, but is still compatible at the 1.5σ

level. This is the main difference between the two types of probes.

, is

below that from the other probes, but is still compatible at the 1.5σ

level. This is the main difference between the two types of probes.

However, the use of growth data in cosmology deserves some comments. In our work, as in many others, different assumptions about the importance of non-linearities in structure formation are made in the theoretical predictions and in the experimental extraction of growth data from the measured matter power spectrum.

As noted in Sect. 2.4, our theoretical predictions

are derived in the linear regime and using a quasi-static approximation. While Barreia et al. (2012) confirmed that the latter is valid

in the Galileon model, using only the linear regime is restrictive. As an example, this

may be the origin of the divergences in  that appear in some

Galileon scenarios, as noted by Appleby & Linder

(2012b). Going beyond the linear perturbation theory may change our predictions

and thus could modify the result of our analysis.

that appear in some

Galileon scenarios, as noted by Appleby & Linder

(2012b). Going beyond the linear perturbation theory may change our predictions

and thus could modify the result of our analysis.

|

Fig. 4 Minimized values of h and |

|

Fig. 5 Experimental constraints on the Galileon parameters

|

To estimate this effect, we tried to identify at which scale non-linearities start to

matter and checked whether this value is outside the range of scales taken into account in

the growth-of-structure measurements. As an example, WiggleZ measurements of

fσ8 are derived using a non-linear

growth-of-structure model (Jennings et al. 2011)

and encompass all scales k < 0.3

h Mpc-1. In this model, the frontier between the linear and

the non-linear regimes is k ≈ 0.03 h Mpc-1.

Other measurements in Table 2 include scales up to

k ≈ 0.2−0.4 h Mpc-1 as well. On the other

hand, there is no prediction in the Galileon model that goes beyond the linear regime.

However, estimates of the scale at which non-linear effects appear exist in similar

modified gravity models. Numerical simulations of the Chameleon screening effect for

theories show that non-linearity effects can be significant at scales

k ≈ 0.05 h Mpc-1 (see Brax et al. 2012; Jennings et al. 2012 and Li et al. 2013).

Other simulations of the Vainshtein effect in the DGP model show that significant

differences between the linear and non-linear regimes appear for scales

k > 0.2 h Mpc-1

(Schmidt 2009). Unlike the DGP model, the

Galileon model we considered does not contain a direct scalar-matter coupling

~

theories show that non-linearity effects can be significant at scales

k ≈ 0.05 h Mpc-1 (see Brax et al. 2012; Jennings et al. 2012 and Li et al. 2013).

Other simulations of the Vainshtein effect in the DGP model show that significant

differences between the linear and non-linear regimes appear for scales

k > 0.2 h Mpc-1

(Schmidt 2009). Unlike the DGP model, the

Galileon model we considered does not contain a direct scalar-matter coupling

~ that is usually

considered as an essential ingredient of the Vainshtein effect. However, Babichev & Esposito-Farese (2013) showed that

even if the Galileon field is not directly coupled to matter, the cosmological evolution

of the Galileon field gives rise to an induced coupling of about 1, because of the

Galileon-metric mixing. Therefore, the Vainshtein effect is expected to operate

approximately at the same scales as in the DGP model in the model we considered.

that is usually

considered as an essential ingredient of the Vainshtein effect. However, Babichev & Esposito-Farese (2013) showed that

even if the Galileon field is not directly coupled to matter, the cosmological evolution

of the Galileon field gives rise to an induced coupling of about 1, because of the

Galileon-metric mixing. Therefore, the Vainshtein effect is expected to operate

approximately at the same scales as in the DGP model in the model we considered.

This means the lack of non-linear effects in our perturbation equations, and hence in our predictions for fσ8 in the Galileon model, is likely to have a significant impact on the constraints we derived from growth measurements, since the latter accounted partially for non-linear effects.

4.4. Full combined constraints

Results from all data are presented in Fig. 7. Table

4 presents the best-fit values for the Galileon

model parameters. The derived  value is

value is  (63)Note that negative

values are preferred for the

(63)Note that negative

values are preferred for the  s

at the 1σ level. Moreover, the Galileon h best-fit

values are compatible with the Riess et al. (2011)

measurement.

s

at the 1σ level. Moreover, the Galileon h best-fit

values are compatible with the Riess et al. (2011)

measurement.

We carried out an a posteriori check to identify which scenarios present a significant

amount of early dark energy. At decoupling,

Ωπ(z∗) > 10%Ωr(z∗)

only for viable scenarios with  and

and

.

This check can be made after comparing theory with data because only data can provide

values for h and

.

This check can be made after comparing theory with data because only data can provide

values for h and  . For Galileon

scenarios with

. For Galileon

scenarios with  ,

which is the region favoured by data, we found no significant early dark energy.

,

which is the region favoured by data, we found no significant early dark energy.

4.5. Analysis of the best-fit scenario

What does the best-fit scenario (derived from all data; the last line of Table 4) look like? Because

ρπ can be defined from the (00) Einstein

equation, a Galileon pressure Pπ can be

defined from the (ij) Einstein equation: ![\begin{eqnarray} \label{eq:ppi} \frac{P_{\pi}}{H_0^2 M_{\rm P}^2}&=& \frac{\bar c_2}{2}\h^2\x^2 + 2\bar c_3\h^3\x^2(\h \x)' - \bar c_4\left[ \frac{9}{2}\h^6\x^4 + 12 \h^6\x^3\x' \right.\nonumber \\ &&\left.\phantom{\frac{9}{2}}+ 15 \h^5\x^4\h' \right] + 3\bar c_5\h^7\x^4\left( 5\h \x' + 7\h' \x + 2\h \x \right) . \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/07/aa21256-13/aa21256-13-eq265.png) (64)Combining

ρπ and

Pπ, an equation of state parameter

wπ(z) = Pπ(z)/ρπ(z)

can be built for the Galileon “fluid”. We can also construct an equation for

Ωπ(z) using

(64)Combining

ρπ and

Pπ, an equation of state parameter

wπ(z) = Pπ(z)/ρπ(z)

can be built for the Galileon “fluid”. We can also construct an equation for

Ωπ(z) using

. The

evolution of wπ(z),

Ωπ(z) and

. The

evolution of wπ(z),

Ωπ(z) and

for the Galileon

best-fit scenario is shown in Figs. 8 and 9.

for the Galileon

best-fit scenario is shown in Figs. 8 and 9.

|

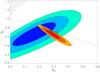

Fig. 6 Experimental constraints on the Galileon model from growth data (red) and from SNLS3+WMAP7+BAO+H0 combined constraints (dashed). The filled dark, medium, and light-colored contours enclose 68.3, 95.4, and 99.7% of the probability, respectively. Dark dotted regions correspond to scenarios rejected by theoretical constraints. |

|

Fig. 7 Combined constraints on the Galileon model from SNLS3, WMAP7+BAO+H0, and growth data. The filled dark, medium, and light-yellow contours enclose 68.3, 95.4, and 99.7% of the probability, respectively. Dark dotted regions correspond to scenarios rejected by theoretical constraints. |

ΛCDM best-fit values from different data samples.

|

Fig. 8 Evolution of the Ωi(z) (left) and of w(z) (right, solid curve) for the best-fit Galileon model from all data (last row of Table 4). As a comparison, the dashed orange line gives w(z) for the best-fit scenario from SN data alone. |

4.5.1. Cosmic evolution

The left panel of Fig. 8 shows that for the best-fit scenario, radiation, matter, and dark energy (here the Galileon) dominate alternatively during the history of the Universe, as in any standard cosmological model. These three epochs are also visible in the evolution of w(z). Moreover, the best-fit scenario evolves in the future toward the de Sitter solution w = −1, which is an attractor of the Galileon model (De Felice & Tsujikawa 2010). In the region 0 < z < 1, where SNe tightly constrain dark energy, w(z) deviates significantly from − 1, its ΛCDM value. Note that in the fit with SNe alone, the deviation is less pronounced, with an average value of − 1.09 in 0 < z < 1, which is compatible with the fitted value of w in constant w dark energy models, as published in Conley et al. (2011).

During matter domination, dark energy contributes about 0.4% to the mass-energy budget

at z = 10. For comparison, in a standard ΛCDM model dark energy

contributes only 0.2% at this redshift (assuming a flat ΛCDM model with

).

In the same way, dark energy contributes 0.04% at z∗ in the

Galileon best-fit scenario, whereas for ΛCDM ΩΛ = 10-9 at

z∗. In our best-fit Galileon scenario, dark energy is more

present throughout the history of the Universe than in the ΛCDM model, but is still

negligible during the matter and radiation eras.

).

In the same way, dark energy contributes 0.04% at z∗ in the

Galileon best-fit scenario, whereas for ΛCDM ΩΛ = 10-9 at

z∗. In our best-fit Galileon scenario, dark energy is more

present throughout the history of the Universe than in the ΛCDM model, but is still

negligible during the matter and radiation eras.

Figure 9 shows the evolution of

for the

best-fit scenario and for the growth-data best-fit scenario. Both curves show deviations

from 1 at redshifts around 0. Particularly, the divergence near the current epoch

suggests that we should push the Galileon predictions for

fσ8 beyond the linear regime, as already

advocated in Sect. 4.3.

for the

best-fit scenario and for the growth-data best-fit scenario. Both curves show deviations

from 1 at redshifts around 0. Particularly, the divergence near the current epoch

suggests that we should push the Galileon predictions for

fσ8 beyond the linear regime, as already

advocated in Sect. 4.3.

4.5.2. Comparison with ΛCDM

In Fig. 10 and Table 5, best-fit values for the ΛCDM parameters are presented using the

same analysis tools and observables. Interestingly, even in the ΛCDM model there is

tension between growth data and other probes. The

best-fit

value is similar in both models, but the h value departs more from the

H0Riess et al.

(2011) measurement. As far as the χ2s are

concerned, SNe Ia provide a good agreement with both models. CMB+BAO+H0 data are more

compatible with the Galileon model, reflecting the better agreement on the

h minimized value. Yet growth-of-structure data agree better with the

ΛCDM model. Finally, due to the poorer fit to growth data in the Galileon model, the

difference in χ2 is Δχ2 = 10.2.

This indicates that the Galileon model is slightly disfavored with respect to the ΛCDM

model, despite having two extra free parameters.

best-fit

value is similar in both models, but the h value departs more from the

H0Riess et al.

(2011) measurement. As far as the χ2s are

concerned, SNe Ia provide a good agreement with both models. CMB+BAO+H0 data are more

compatible with the Galileon model, reflecting the better agreement on the

h minimized value. Yet growth-of-structure data agree better with the

ΛCDM model. Finally, due to the poorer fit to growth data in the Galileon model, the

difference in χ2 is Δχ2 = 10.2.

This indicates that the Galileon model is slightly disfavored with respect to the ΛCDM

model, despite having two extra free parameters.

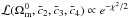

Because we are comparing two models with a different number of parameters and complexity, other criteria than comparing χ2s can be helpful. A review of the selection model criterion is provided in Liddle (2007). Because our study leads to the full computation of the likelihood functions, we can use precise criteria such as the Bayes factor (see Beringer et al. 2012; John & Narlikar 2002; Kass & Raftery 1995 and Liddle 2009) or the deviance information criterion (DIC, see Spiegelhalter et al. 2002 and Kunz et al. 2006). The Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC) criteria used in Nesseris et al. (2010) are approximations of the first two using only the maximum likelihood and not the whole function. Hereafter we restrict the discussion to the DIC criterion.

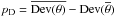

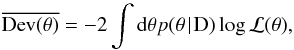

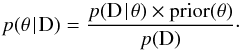

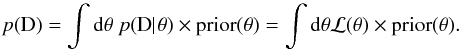

The DIC criterion is based on the computation of the deviance likelihoods

Dev(θ) = −2log p(D|θ) + C (with

C a constant not important for DIC evaluation).

p(D|θ) is the computed likelihood function

ℒ(θ) of the model. An effective number of parameters

is derived with

is derived with

the expectation

values for θ and

the expectation

values for θ and  the

mean deviance likelihood value:

the

mean deviance likelihood value:  (65)where

p(θ|D) is the posterior probability density

function for a vector θ of parameters of the tested model, knowing the

data D:

(65)where

p(θ|D) is the posterior probability density

function for a vector θ of parameters of the tested model, knowing the

data D:  (66)p(D),

the probability to obtain the data D, is also called the marginal likelihood because it

can be computed using the summation over all θs:

(66)p(D),

the probability to obtain the data D, is also called the marginal likelihood because it

can be computed using the summation over all θs:

(67)Note that if the priors

are flat, p(θ|D) is just the likelihood function

ℒ(θ) normalized to 1. In our case, prior(θ) is a

flat prior reflecting the theoretically allowed volume in the scanned parameter space.

We checked that the DIC criterion is not sensitive to the exact definition of the prior,

which makes it a robust tool.

(67)Note that if the priors

are flat, p(θ|D) is just the likelihood function

ℒ(θ) normalized to 1. In our case, prior(θ) is a

flat prior reflecting the theoretically allowed volume in the scanned parameter space.

We checked that the DIC criterion is not sensitive to the exact definition of the prior,

which makes it a robust tool.

Then  . The model with the

smallest DIC is favored by the data. In our study, we obtained

DICGalileon − DICΛCDM = 12.25 > 0.

Again, the Galileon model is slightly disfavored by data against the ΛCDM model. The DIC

criterion just reflects the Δχ2 and does not penalize the

Galileon model so much because of its higher number of free parameters.

. The model with the

smallest DIC is favored by the data. In our study, we obtained

DICGalileon − DICΛCDM = 12.25 > 0.

Again, the Galileon model is slightly disfavored by data against the ΛCDM model. The DIC

criterion just reflects the Δχ2 and does not penalize the

Galileon model so much because of its higher number of free parameters.

In the future, provided the tension between growth-of-structure data and distances does not increase after more precise measurements of the observables used in this paper are included, new observables will be necessary to distinguish between the two models. A promising way would be to exploit, e.g., the ISW effect as discussed in Kobayashi et al. (2010).

|

Fig. 9 Evolution of |

|

Fig. 10 Experimental constraints on the ΛCDM model from SNLS3 data (blue), growth data (red), BAO+WMAP7+H0 data (green), and all data combined (yellow). The black dashed line indicates the flatness condition Ωm + ΩΛ = 1. |

|

Fig. 11 Experimental constraints on the FWCDM model from SNLS3 data (blue), growth data (red), BAO+WMAP7+H0 data (green), and all data combined (yellow). |

FWCDM best-fit values from different data samples.

4.5.3. Comparison with FWCDM

For consistency with our assumption about flatness, we also present a comparison with the effective FWCDM model, a model with a constant dark energy equation of state parameter w in a flat Universe (see Table 6 and Fig. 11). The data set points toward a value of w below − 1, which is consistent with the Galileon best-fit scenario (see Fig. 8).

However, the difference in χ2 is the same as for the ΛCDM model, Δχ2 = 10.2, and the DIC criterion gives DICGalileon − DICFWCDM = 12.16 > 0. Here again, the Galileon model is not significantly disfavored.

5. Discussion

In this section we compare our results with other recent publications on the same subject.

Appleby & Linder (2012b) concluded that the uncoupled Galileon model is ruled out by current data since their best-fit yielded Δχ2 = 31 compared with the best-fit ΛCDM model. In addition, they obtained a long narrow region of degenerate scenarios with nearly the same likelihood. In our case, the best-fit has Δχ2 = 10.2, we obtained enclosed contours in all projections and a clear minimum.

Although we used the same expansion and perturbation equations as Appleby & Linder (2012b), there are differences between the two

works. We used a parametrization of the model, which makes our study independent of initial

conditions for x, while they set

xi = x(zi = 106)

by imposing a

ρπ(zi) which varied

in their parameter scan. This requires one to solve a fifth-order polynomial equation in

xi – and hence one is forced to choose one of the five

solutions – or to assume one of the four terms  is dominant in the (00) Einstein equation. In any case, this leads to a parameter space that

is different than the one we explored. Another difference arises from the theoretical

constraints that are used to restrict the parameter space to viable scenarios only. Our set

of theoretical constraints is larger because we also used tensorial constraints, which

proved to be very powerful. This also leads to a different explored parameter space.

is dominant in the (00) Einstein equation. In any case, this leads to a parameter space that

is different than the one we explored. Another difference arises from the theoretical

constraints that are used to restrict the parameter space to viable scenarios only. Our set

of theoretical constraints is larger because we also used tensorial constraints, which

proved to be very powerful. This also leads to a different explored parameter space.

In De Felice & Tsujikawa (2010), the

rescaling of the Galileon parameters was performed with a de Sitter solution instead of

using x0, as in this paper. This led to relations fixing their

“ ”

and “

”

and “ ”

coefficients as a function of their “

”

coefficients as a function of their “ ”

and “

”

and “ ”

coefficients (denoted α and β in their study), but

required two initial conditions to compute the cosmological evolution. Those were also

fitted using experimental data. With this parametrization and without growth constraints,

Nesseris et al. (2010) found best-fit values for

their “

”

coefficients (denoted α and β in their study), but

required two initial conditions to compute the cosmological evolution. Those were also

fitted using experimental data. With this parametrization and without growth constraints,

Nesseris et al. (2010) found best-fit values for

their “ ”

and “

”

and “ ”

of the same sign and same order of magnitude as in our work, despite our different

parametrizations. A second paper by Okada et al.

(2013) included redshift space distortion measurements and ruled out the Galileon

model at the 10σ level.

”

of the same sign and same order of magnitude as in our work, despite our different

parametrizations. A second paper by Okada et al.

(2013) included redshift space distortion measurements and ruled out the Galileon

model at the 10σ level.

The first difference with respect to our work is the treatment of the initial conditions

and the use of an extra theoretical constraint to avoid numerical instabilities during the

transition from the matter era to the de Sitter epoch. This reduces the parameter space with

respect to that explored in our work. As stated above, a better modeling of

including non-linear effects should be conducted instead of discarding scenarios with such

instabilities.

including non-linear effects should be conducted instead of discarding scenarios with such

instabilities.

Second, Okada et al. (2013) used

fσ8 measurements not corrected for the

Alcock-Paczynski effect. Moreover, to make their

fσ8 predictions in the Galileon model, Okada et al. (2013) set the normalization of

σ8 today to the WMAP7

σ8(z = 0) measurement, which was obtained in

a cosmological fit to the ΛCDM model. This normalization led to the following

σ8(z) evolution:  (68)This assumes that

the Galileon theory predicts a matter power spectrum similar to that of ΛCDM at

z = 0, which is not guaranteed (Barreia et

al. 2012). In contrast, we used the WMAP7 σ8

measurement to set the normalization at decoupling

z ≈ z∗ (see Eq. (59)). Thus we took into account the different

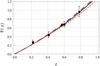

growth histories between the ΛCDM and the Galileon models (Eq. (60), which is different from Eq. (68)). We can compare our best-fit scenarios for

these two models with the fσ8 and

F measurements. Figures 12 and

13 show the result of this comparison. The agreement

with the data is good in both models. In particular, the Galileon model does not exhibit a

discrepancy as strong as was found in Fig. 3 of Okada et al.

(2013).

(68)This assumes that

the Galileon theory predicts a matter power spectrum similar to that of ΛCDM at

z = 0, which is not guaranteed (Barreia et

al. 2012). In contrast, we used the WMAP7 σ8

measurement to set the normalization at decoupling

z ≈ z∗ (see Eq. (59)). Thus we took into account the different

growth histories between the ΛCDM and the Galileon models (Eq. (60), which is different from Eq. (68)). We can compare our best-fit scenarios for

these two models with the fσ8 and

F measurements. Figures 12 and

13 show the result of this comparison. The agreement

with the data is good in both models. In particular, the Galileon model does not exhibit a

discrepancy as strong as was found in Fig. 3 of Okada et al.

(2013).

|

Fig. 12 fσ8(z) measurements from different surveys (6dFGRS, 2fFGRS, SDSS LRG, BOSS, and WiggleZ) compared with predictions for the ΛCDM model (with parameters of Table 5 – dashed purple line) Galileon scenarios. The solid blue line stands for the best-fit Galileon scenario using all data, whereas the orange dashed line stands for the best-fit Galileon scenario using growth data only. |

|

Fig. 13 F(z) measurements from different surveys (BOSS and WiggleZ) compared with the prediction for the ΛCDM model (with parameters of Table 5 – dashed purple line) and for Galileon scenarios. The solid blue line stands for the best-fit Galileon scenario using all data, whereas the orange dashed line stands for the best-fit Galileon scenario using growth data only. |

6. Conclusion

We have confronted the uncoupled Galileon model with the most recent cosmological data. We introduced a renormalization of the Galileon parameters by the derivative of the Galileon field normalized to the Planck mass to break some degeneracies inherent to the model. Theoretical conditions were added to restrict the analysis to viable scenarios only. This allowed us to break the parameter degeneracies that otherwise would have prevented us from obtaining enclosed probability contours. In particular, the conditions on the tensorial propagation mode of the perturbed metric proved to be very helpful.

We used a grid search technique to explore the Galileon parameter space. Our data set

encompassed the SNLS3 SN Ia sample, WMAP7

{la,R,z∗}

constraints, BAO measurements, and growth data with the Alcock-Paczynski effect taken into

account. We found  . The

final χ2 is slightly above that of the ΛCDM model due to a

poorer fit to the growth data.

. The

final χ2 is slightly above that of the ΛCDM model due to a

poorer fit to the growth data.

The best-fit Galileon scenario mimics a ΛCDM model with the three periods of radiation,

matter, and dark energy domination, with an evolving dark energy equation of state parameter

w(z), and an effective gravitational coupling

.

Predictions for the latter are possible only in the linear regime, which may have an impact

on our results derived from growth data because the latter were computed using a non-linear

theory. A more precise theoretical and phenomenological study should be conducted to fairly

compare the Galileon model with these data.

.

Predictions for the latter are possible only in the linear regime, which may have an impact

on our results derived from growth data because the latter were computed using a non-linear

theory. A more precise theoretical and phenomenological study should be conducted to fairly

compare the Galileon model with these data.