| Issue |

A&A

Volume 550, February 2013

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A53 | |

| Number of page(s) | 16 | |

| Section | Planets and planetary systems | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201220146 | |

| Published online | 24 January 2013 | |

New analytical expressions of the Rossiter-McLaughlin effect adapted to different observation techniques ⋆

1

Centro de Astrofísica, Universidade do Porto

Rua das Estrelas

4150-762

Porto

Portugal

2

Astronomie et Systèmes Dynamiques, IMCCE-CNRS UMR 8028,

Observatoire de Paris, UPMC, 77 Av.

Denfert-Rochereau, 75014

Paris,

France

3

Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, University of

Chicago, 5640 South Ellis

Avenue, Chicago,

IL

60637,

USA

e-mail: boue@oddjob.uchicago.edu

4

Departamento de Física e Astronomia, Faculdade de Ciências,

Universidade do Porto, Rua do Campo

Alegre, 4169-007

Porto,

Portugal

Received:

31

July

2012

Accepted:

31

October

2012

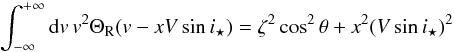

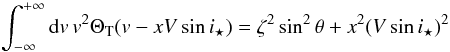

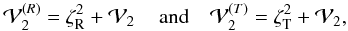

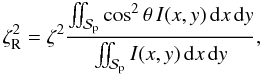

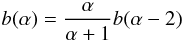

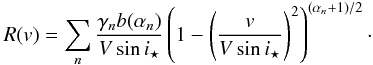

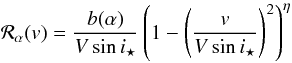

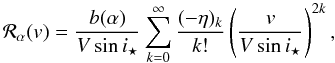

The Rossiter-McLaughlin (hereafter RM) effect is a key tool for measuring the projected spin-orbit angle between stellar spin axes and orbits of transiting planets. However, the measured radial velocity (RV) anomalies produced by this effect are not intrinsic and depend on both instrumental resolution and data reduction routines. Using inappropriate formulas to model the RM effect introduces biases, at least in the projected velocity Vsini⋆ compared to the spectroscopic value. Currently, only the iodine cell technique has been modeled, which corresponds to observations done by, e.g., the HIRES spectrograph of the Keck telescope. In this paper, we provide a simple expression of the RM effect specially designed to model observations done by the Gaussian fit of a cross-correlation function (CCF) as in the routines performed by the HARPS team. We derived a new analytical formulation of the RV anomaly associated to the iodine cell technique. For both formulas, we modeled the subplanet mean velocity vp and dispersion βp accurately taking the rotational broadening on the subplanet profile into account. We compare our formulas adapted to the CCF technique with simulated data generated with the numerical software SOAP-T and find good agreement up to Vsini⋆ ≲ 20 km s-1. In contrast, the analytical models simulating the two different observation techniques can disagree by about 10σ in Vsini⋆ for large spin-orbit misalignments. It is thus important to apply the adapted model when fitting data.

Key words: techniques: spectroscopic / instrumentation: spectrographs / planetary systems / methods: analytical / methods: data analysis

A public code implementing the expressions derived in this paper is available at http://www.astro.up.pt/resources/arome. A copy of the code is also available at the CDS via anonymous ftp to cdsarc.u-strasbg.fr (130.79.128.5) or via http://cdsarc.u-strasbg.fr/viz-bin/qcat?J/A+A/550/A53

© ESO, 2013

1. Introduction

Transiting planets produce radial velocity (RV) anomalies when crossing the disk of their star. This mechanism, known as the Rossiter-McLaughlin effect (hereafter RM effect), is due to the stellar proper rotation and the fact that during a transit, a planet successively covers different portions of the stellar disk with different average velocities along the line of sight (Holt 1893; Rossiter 1924; McLaughlin 1924). The RM effect has gained importance in the exoplanet community since it allows the measurement of the projected angle between the stellar spin-axis and the orbit of the planet.

|

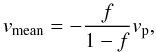

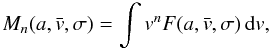

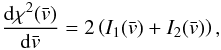

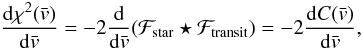

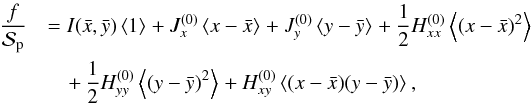

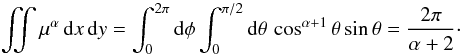

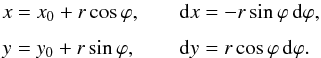

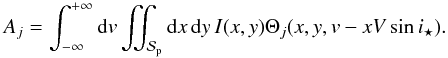

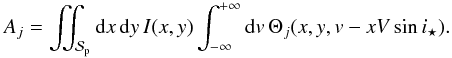

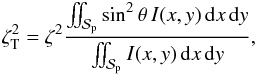

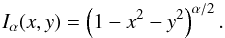

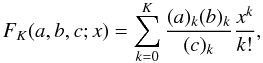

Fig. 1 Simplified illustration of different methods to compute the Rossiter-McLaughlin effect. vH10, viodine, and vCCF represent the result of the hypothesis made in Hirano et al. (2010), the result of the data reduction done with the iodine cell technique, and the result of the data reduction done with the CCF technique, respectively. |

The first measurements of the RM effect induced by a transiting planet were performed almost simultaneously with two different instruments on the same bright star HD 209458. Queloz et al. (2000) observed the signal with the ELODIE spectrograph on the 193 cm telescope of the Observatoire de Haute Provence, while Bundy & Marcy (2000) used the HIRES spectrograph on the Keck telescope. As explained later on, the choice of the instrument and, more particularly, the subsequent reduction analysis, have a non negligible impact on the resulting shape of signal. It is thus interesting to see that the two kinds of instrument, coupled with their own data treatment, which are still employed today, have been used in parallel since the beginning.

The first planet-host stars studied with this technique were all compatible with low obliquity. It was along the lines of the model of planet migration in a protoplanetary disk. But then, several misaligned systems have been detected, starting with XO-3 with an angle initially announced at 70° ± 15° (Hébrard et al. 2008) and then refined to 37.3° ± 3° (Winn et al. 2009), yet still significantly misaligned. With the growth of the sample, a first correlation appeared showing that the hottest stars tend to be more misaligned (Winn et al. 2010). Additionally, a first statistical comparison between observations and theoretical predictions have been performed (Triaud et al. 2010), suggesting that some of the hot Jupiters might be the result of the interaction with a stellar companion, leading to a Lidov-Kozai mechanism, characterized by phases of large eccentricity and inclination and followed by a circularization by tides raised on the planet as it approaches the star (Wu & Murray 2003; Fabrycky & Tremaine 2007). Other scenarios have then been developed to explain the formation of hot Jupiters, such as planet-planet scattering (Rasio & Ford 1996; Beaugé & Nesvorný 2012), the crossing of secular resonances (Wu & Lithwick 2011), or the Lidov-Kozai mechanism produced by a planetary companion (Naoz et al. 2011; Nagasawa & Ida 2011). A new trend between age and obliquity has also been found (Triaud 2011) suggesting that tidal dissipation may play an important role in the evolution of those systems, as confirmed by Albrecht et al. (2012).

Accurate modelings of the RM effect are thus needed to get reliable information on the current obliquity of stars and to test theoretical predictions. In the literature, one can find several analytical expressions to model this effect (Kopal 1942; Ohta et al. 2005; Giménez 2006; Hirano et al. 2010, 2011). They are not all identical because they model different techniques of radial velocity measurements.

This raises an issue that should be considered with caution. RVs measured by different techniques or even by different instruments using the same algorithm can differ by more than a constant offset. To illustrate this point, we consider a random variable with a given probability distribution function (PDF), and ask what its average value is. The term average is vague and can mean different quantities: mean, median, mode, etc. Nevertheless, if the PDF is symmetrical, any of these quantities lead to the same result, eventually with different robustnesses with respect to noise. But if the PDF is not symmetrical, each estimator of the average value provides different results that cannot be compared directly. The situation is similar in RV observations, as noticed by Hirano et al. (2010). There are at least two different ways to measure RVs. One relies on the iodine cell technique which consists in fitting an observed spectrum with a modeled one that is Doppler-shifted (Butler et al. 1996). The other is based on a Gaussian fit to a cross-correlation function (CCF) (Baranne et al. 1996; Pepe et al. 2002). The former technique is applied to observations made with HIRES on the Keck telescope or with HDS at the Subaru telescope, while the latter is the routine of, e.g., SOPHIE at the Observatoire de Haute Provence or HARPS at La Silla Observatory. If stars are affected by neither spots nor transiting planets, their spectral lines have constant shapes, and thus the RVs derived by any instruments may only differ by a constant offset. In contrast, spectral lines are deformed during transits, and these deformations vary with time. As a consequence, each analysis routine is expected to lead to a different signal. In turn, it is important to have an analytical model adapted to each analysis routine in order to interpret RM data. Moreover, it also means that one should not combine RM measurements from different instruments.

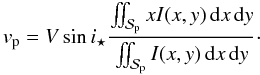

The first analytical expressions of the RM effect were derived by Kopal (1942), Ohta et al. (2005),

and Giménez (2006). They all computed the weighted

mean velocity, hereafter called vmean, along the line of sight

of the stellar surface uncovered by the planet. This mean velocity, weighted by the surface

intensity, leads to an exact expression of the form  (1)where

f is the fraction of the flux blocked by the planet disk

and vp is the average velocity of the surface of the star

covered by the planet. This expression is simple and exact. There is no assumption behind

it. But, it does not correspond to the quantity that is actually measured in the

observations by either the iodine cell technique, or by the Gaussian fit of the CCF. Thus,

the analytical prediction vmean is systematically biased when

compared directly with observations. The difference increases for high stellar rotational

velocities.

(1)where

f is the fraction of the flux blocked by the planet disk

and vp is the average velocity of the surface of the star

covered by the planet. This expression is simple and exact. There is no assumption behind

it. But, it does not correspond to the quantity that is actually measured in the

observations by either the iodine cell technique, or by the Gaussian fit of the CCF. Thus,

the analytical prediction vmean is systematically biased when

compared directly with observations. The difference increases for high stellar rotational

velocities.

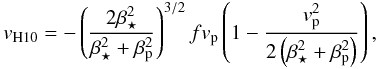

To solve this problem, Hirano et al. (2010) propose

a new analytical expression closely related to the reduction algorithm of the iodine cell

technique (see Fig. 1). This method consists in fitting

a shifted spectrum outside of transits, which is modeled, here, by a single averaged

spectral line and noted1 ,

with the line profile detected during a transit ℱtransit(v), via

the Doppler shift

,

with the line profile detected during a transit ℱtransit(v), via

the Doppler shift  .

The quantity provided by the formulas of Hirano et al.

(2010) is the value, hereafter denoted vH10, of the

velocity

.

The quantity provided by the formulas of Hirano et al.

(2010) is the value, hereafter denoted vH10, of the

velocity  that maximizes the cross-correlation between the two line profiles

that maximizes the cross-correlation between the two line profiles

. We show

in Sect. 3.1 that if ℱstar is an even

function, the maximization of the cross-correlation

. We show

in Sect. 3.1 that if ℱstar is an even

function, the maximization of the cross-correlation  is indeed identical to the minimization of the chi-square associated to the fit of

ℱtransit(v) by

is indeed identical to the minimization of the chi-square associated to the fit of

ℱtransit(v) by  .

In that case, the result depends on the actual shape of the line profiles, as observed in

practice. In the simplest case where the line profiles of both the nonrotating and the

rotating star are Gaussian, this method leads to (Hirano

et al. 2010)

.

In that case, the result depends on the actual shape of the line profiles, as observed in

practice. In the simplest case where the line profiles of both the nonrotating and the

rotating star are Gaussian, this method leads to (Hirano

et al. 2010)  (2)where

β⋆ and βp are

the dispersion of the Gaussian profiles ℱstar(v) and

ℱpla(v − vp) respectively2.

ℱpla(v − vp) is the line profile

of the light blocked by the planet centered on vp. Although this

expression is the result of an expansion in both f and

vp, it gives a better representation of the measured radial

velocity. Hirano et al. (2010) also provide more

complex expressions in the case of Voigt profiles, and in Hirano et al. (2011), additional effects are taken into account such as

macro-turbulence. But the result is not expressed as a simple analytical formula and it

requires several numerical integrations.

(2)where

β⋆ and βp are

the dispersion of the Gaussian profiles ℱstar(v) and

ℱpla(v − vp) respectively2.

ℱpla(v − vp) is the line profile

of the light blocked by the planet centered on vp. Although this

expression is the result of an expansion in both f and

vp, it gives a better representation of the measured radial

velocity. Hirano et al. (2010) also provide more

complex expressions in the case of Voigt profiles, and in Hirano et al. (2011), additional effects are taken into account such as

macro-turbulence. But the result is not expressed as a simple analytical formula and it

requires several numerical integrations.

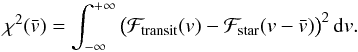

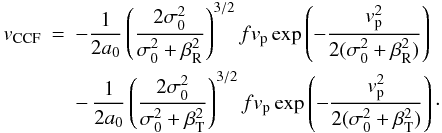

The model of Hirano et al. (2010, 2011) is well adapted to the iodine cell technique, but it still does not correspond to the analysis routines used on stabilized spectrographs, e.g., SOPHIE and HARPS (Baranne et al. 1996; Pepe et al. 2002). In these routines, the observed spectrum is first cross-correlated with a template spectrum. This gives the so-called cross-correlation function (CCF) which can be seen as a weighted average of all the spectral lines convolved with a rectangular function. Finally, the CCF is fitted by a Gaussian whose mean represents the observed radial velocity vCCF (see Fig. 1). Currently, there is no analytical expression of this quantity in the literature. The goal of this paper is to provide such an expression. As we will see, even in the general case where the spectral line profile ℱstar is not Gaussian, the resulting formula is as simple as Eq. (2) derived by Hirano et al. (2010) and exact in vp.

This paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we analytically derive an unbiased expression vCCF modeling the RM effect as measured by, e.g., SOPHIE and HARPS. This formula is specially designed to simulate the radial velocity measurements obtained by fitting a Gaussian to a CCF. We first provide very generic expressions that relies only on the symmetry of the spectroscopic lines, and then, we give a much simpler formula corresponding to Gaussian subplanet line profiles. In Sect. 3, we propose a new expression viodine of the RM signal derived by the iodine technique. In comparison to the previous ones, it is analytical and valid for any spectroscopic Vsini⋆. Then, in Sect. 4, we detail the calculation of the parameters entering into our formulas vCCF and viodine, which are the flux fraction f occulted by the planet, the subplanet velocity vp, and the dispersion βp. In Sect. 5, we compare our analytical results with simulated data generated with SOAP-T, a modified version of the numerical code SOAP (Boisse et al. 2012), able to reproduce RM signals (Oshagh et al. 2013). We also analyze biases introduced by the application of a wrong model in the fit of RM signals. Finally, we conclude in Sect. 6.

2. Modeling of the RM effect measured by the CCF technique

2.1. General derivation

We derive a very general expression of the RM effect obtained using a Gaussian fit to the

CCF. As in Hirano et al. (2010), we only consider

the linear effect with respect to the flux ratio f. But the method can

easily be generalized to higher orders. We define ℱstar(v),

ℱpla(v − vp), and

ℱtransit(v) the line profile of the CCF produced by the

integrated stellar surface, by the part of the stellar surface covered by the planet, and

by the uncovered stellar surface, respectively. At this stage, the line profiles

ℱstar, ℱpla, and ℱtransit are not necessarily Gaussian.

The dependency of ℱpla is on

(v − vp) because this line is centered on

vp. By convention, ℱstar(v) and

ℱpla(v − vp) are normalized to

one. With this convention, even absorption spectral lines are positive.

We have

ℱtransit(v) = ℱstar(v) − fℱpla(v − vp).

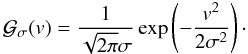

Moreover, we denote  as the unit Gaussian profile with dispersion σ and centered on the origin

as the unit Gaussian profile with dispersion σ and centered on the origin

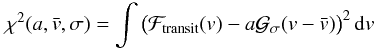

(3)The fit of the CCF

measured during transit, ℱtransit(v), by a Gaussian

corresponds to the maximization of the likelihood

(3)The fit of the CCF

measured during transit, ℱtransit(v), by a Gaussian

corresponds to the maximization of the likelihood

(4)with respect to the

normalization factor a, the mean velocity

(4)with respect to the

normalization factor a, the mean velocity

,

and the dispersion σ. The partial derivatives read as

,

and the dispersion σ. The partial derivatives read as  (5)We

now set all the derivatives to zero, express ℱtransit(v) as a

function of ℱstar(v) and ℱpla(v),

and reorder the terms. The system of Eqs. (5) is equivalent to

(5)We

now set all the derivatives to zero, express ℱtransit(v) as a

function of ℱstar(v) and ℱpla(v),

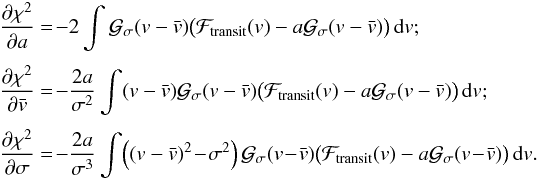

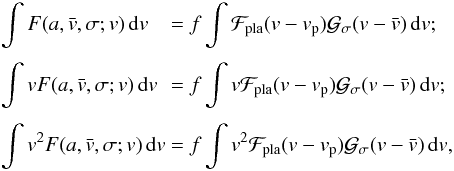

and reorder the terms. The system of Eqs. (5) is equivalent to  (6)with

(6)with

(7)To solve this system, we

apply the usual perturbation method. We develop the parameters in series of the flux ratio

f, i.e.,

a = a0 + fa1 + f2a2 + ...,

and idem for

(7)To solve this system, we

apply the usual perturbation method. We develop the parameters in series of the flux ratio

f, i.e.,

a = a0 + fa1 + f2a2 + ...,

and idem for  and σ. At the zeroth order in f, the system (6) corresponds to the fit of

ℱstar(v) by a Gaussian. The effect of the planet is absent

from the fit, thus

and σ. At the zeroth order in f, the system (6) corresponds to the fit of

ℱstar(v) by a Gaussian. The effect of the planet is absent

from the fit, thus  .

The other parameters a0 and σ0 are

those of the best Gaussian fit outside of transits.

.

The other parameters a0 and σ0 are

those of the best Gaussian fit outside of transits.

In a second step, we linearize the system (6) in the vicinity of the zeroth order solution. We thus compute the partial

derivatives of  (8)appearing in the

left-hand side of (6), at

a = a0,

(8)appearing in the

left-hand side of (6), at

a = a0,

,

and σ = σ0. To avoid fastidious calculation,

we make the simple hypothesis that ℱstar(v) is symmetrical, or

more precisely, an even function of the velocity v. In practice, due to

the convective blue shift (CB), spectral lines are not perfectly symmetric. The net effect

of CB is a small deformation in RM signals with amplitude of order 1 m s-1

(Albrecht et al. 2012) that we neglect. Then,

,

and σ = σ0. To avoid fastidious calculation,

we make the simple hypothesis that ℱstar(v) is symmetrical, or

more precisely, an even function of the velocity v. In practice, due to

the convective blue shift (CB), spectral lines are not perfectly symmetric. The net effect

of CB is a small deformation in RM signals with amplitude of order 1 m s-1

(Albrecht et al. 2012) that we neglect. Then,

and

and  are even functions of

are even functions of  ,

while

,

while  is odd. As a result, the derivatives

is odd. As a result, the derivatives  ,

,

,

∂M1/∂a,

and

∂M1/∂σ

taken at

,

∂M1/∂a,

and

∂M1/∂σ

taken at  vanish. Moreover, if the subplanet line profile is also an even function then the

integrals of the righthand side of the system (6) become simple convolutions at

vanish. Moreover, if the subplanet line profile is also an even function then the

integrals of the righthand side of the system (6) become simple convolutions at  .

Then there is only

.

Then there is only  ,\notag \\ \left(\Dron{M_1}{\vx}\right) \vx_1& &= \left[(v\,\Gfitb)*\Fpla\right](v_{\rm p}) ,\notag \\ \left(\Dron{M_2}{a}\right) a_1& +\left(\Dron{M_2}{\sigma}\right) \sigma_1 &= \left[(v^2\Gfitb)*\Fpla\right](v_{\rm p}) , \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/02/aa20146-12/aa20146-12-eq57.png) (9)where

∗ denotes the convolution product. The first and the third lines are independent of the

mean velocity

(9)where

∗ denotes the convolution product. The first and the third lines are independent of the

mean velocity  .

Their resolution provides a correction to the amplitude and the width of the best Gaussian

fit during a transit. The second equation is the most interesting, since it contains the

quantity

.

Their resolution provides a correction to the amplitude and the width of the best Gaussian

fit during a transit. The second equation is the most interesting, since it contains the

quantity  we are looking for. By chance, this is also the simplest. The velocity anomaly obtained by

the Gaussian fit

we are looking for. By chance, this is also the simplest. The velocity anomaly obtained by

the Gaussian fit  is then

is then  \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/02/aa20146-12/aa20146-12-eq61.png) (10)where

(10)where

should be computed at

(a0,0,σ0),

i.e.,

should be computed at

(a0,0,σ0),

i.e.,  . \label{eq.dM1dv} \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/02/aa20146-12/aa20146-12-eq64.png) (11)The

convolution product taken at 0 on the righthand side of (11) is nothing else but M2, which cancels

by the definitions of a0 and σ0.

Thus the RM effect now reads as

(11)The

convolution product taken at 0 on the righthand side of (11) is nothing else but M2, which cancels

by the definitions of a0 and σ0.

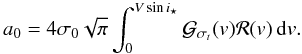

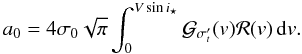

Thus the RM effect now reads as ![\begin{equation} \vc = -\frac{4\sigma_0\sqrt{\pi}}{a_0} f \left[\left(v\,\Gfitb\right)*\Fpla)\right]\left(v_{\rm p}\right). \label{eq.solgen} \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/02/aa20146-12/aa20146-12-eq66.png) (12)This expression does

not depend directly on the stellar line profile ℱstar. The dependence only

occurs through the best Gaussian fit (a0 and

σ0), which is performed to derive the radial velocity. The

formula (12) is thus very powerful, since

it does not require any knowledge on ℱstar. Unfortunately, the

amplitude a0 of the best Gaussian fit in (12) is associated to a normalized line

profile ℱstar while, in practice, the area of a CCF is difficult to measure,

and ℱstar is never normalized. We thus provide the expression of

a0 as a function of ℱstar and the best Gaussian

fit

(12)This expression does

not depend directly on the stellar line profile ℱstar. The dependence only

occurs through the best Gaussian fit (a0 and

σ0), which is performed to derive the radial velocity. The

formula (12) is thus very powerful, since

it does not require any knowledge on ℱstar. Unfortunately, the

amplitude a0 of the best Gaussian fit in (12) is associated to a normalized line

profile ℱstar while, in practice, the area of a CCF is difficult to measure,

and ℱstar is never normalized. We thus provide the expression of

a0 as a function of ℱstar and the best Gaussian

fit  ,

,

. \label{eq.a0} \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/02/aa20146-12/aa20146-12-eq68.png) (13)We emphasize that

a0 is independent of vp. As a

consequence, it does not affect the shape of the RM effect, but only slightly the

amplitude (a0 remains close to one). The computation of

a0 is detailed in Appendix B.

(13)We emphasize that

a0 is independent of vp. As a

consequence, it does not affect the shape of the RM effect, but only slightly the

amplitude (a0 remains close to one). The computation of

a0 is detailed in Appendix B.

2.2. Gaussian subplanet line profile

At this stage, the expression (12) is very general, and holds as long as the line profiles ℱstar(v) and ℱpla(v) are symmetric.

We now make the hypothesis that the subplanet line profile

ℱpla(v) is Gaussian. It should be stressed that, as long as

the planet radius is small compared to that of the star, the subplanet line profile is

only weakly affected by the stellar rotation (see Sect. 4) and thus, it is well approximated by that of the nonrotating star, which we

assume to be Gaussian. Then, the subplanet profile can be considered Gaussian, or equal to

the sum of two Gaussians if macro-turbulence is taken into account (see Appendix A). We denote βp as the

width of the subplanet line profile, i.e.,  .

In that case, the expression of the RM effect (12) becomes

.

In that case, the expression of the RM effect (12) becomes  (14)This is the main equation

of this paper. It represents a good compromise between simplicity and accuracy for the

modeling of RM signals measured by a Gaussian fit of the CCF.

(14)This is the main equation

of this paper. It represents a good compromise between simplicity and accuracy for the

modeling of RM signals measured by a Gaussian fit of the CCF.

2.3. Gaussian stellar line profile

For completeness, we give the expression in the case where the stellar line profile is a

normalized Gaussian with dispersion β⋆. The

best fit should give a0 = 1 and

σ0 = β⋆.

Then, we get  (15)This formula is

equivalent to vH10 (2) given by Hirano et al. (2010). More

precisely, Eq. (2) is the beginning of the

expansion of vCCF. Indeed, if the stellar line profile is

Gaussian, the two approaches are identical.

(15)This formula is

equivalent to vH10 (2) given by Hirano et al. (2010). More

precisely, Eq. (2) is the beginning of the

expansion of vCCF. Indeed, if the stellar line profile is

Gaussian, the two approaches are identical.

3. Modeling of the RM effect measured by the iodine cell technique

In this section, we first explain the equivalence between the iodine cell technique and the

maximization of the cross-correlation  (Hirano et al. 2010, 2011). The aim is to emphasize the hypotheses behind this equivalence

and, thus, to show its limitations. In a second step, we provide a general expression that

models the iodine cell technique. It should be stressed that the function

(Hirano et al. 2010, 2011). The aim is to emphasize the hypotheses behind this equivalence

and, thus, to show its limitations. In a second step, we provide a general expression that

models the iodine cell technique. It should be stressed that the function

is different from the CCF of the previous section and is not used in the same way. It

involves the spectrum during transit and a modeled one without transit deformations. This

function

is different from the CCF of the previous section and is not used in the same way. It

involves the spectrum during transit and a modeled one without transit deformations. This

function  is computed to provide the RV at its maximum. On the other hand, the CCF is the

cross-correlation between the spectrum and a mask. The goal is to provide a single averaged

line that is then fitted by a Gaussian curve.

is computed to provide the RV at its maximum. On the other hand, the CCF is the

cross-correlation between the spectrum and a mask. The goal is to provide a single averaged

line that is then fitted by a Gaussian curve.

3.1. Link between the iodine cell technique and the maximization of

C( )

)

The analysis routine based on the iodine cell technique involves a fit with 13 parameters

of the observed spectrum by a modeled one that is Doppler-shifted (Butler et al. 1996). We assume that this can be approximated by the fit

of a single parameter ( )

representing the Doppler shift between a modeled line profile

ℱstar(v) and the observed one (here during a transit)

ℱtransit(v). The chi-square of this fit reads

)

representing the Doppler shift between a modeled line profile

ℱstar(v) and the observed one (here during a transit)

ℱtransit(v). The chi-square of this fit reads

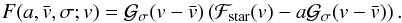

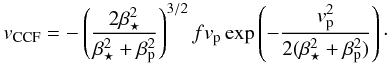

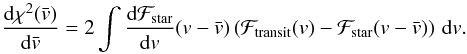

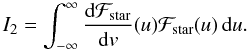

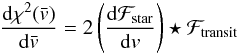

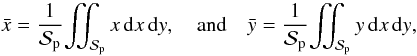

(16)The minimization of this

chi-square corresponds to

(16)The minimization of this

chi-square corresponds to  with

with  (17)The integral on the

righthand side can be split into the sum of two integrals

(17)The integral on the

righthand side can be split into the sum of two integrals

(18)where the first one,

(18)where the first one,

,

is the cross-correlation of dℱstar/dv by

ℱtransit taken at

,

is the cross-correlation of dℱstar/dv by

ℱtransit taken at  ,

while the other is, after the change of variable

,

while the other is, after the change of variable  ,

,

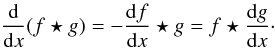

(19)If ℱstar

is even, its derivative is odd, and thus the integral I2

over R vanishes. In that case, only

(19)If ℱstar

is even, its derivative is odd, and thus the integral I2

over R vanishes. In that case, only

(20)remains,

where ⋆ denotes the cross-correlation product defined by

(20)remains,

where ⋆ denotes the cross-correlation product defined by

= \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} f(y-x)g(y)\,{\rm d}y . \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/02/aa20146-12/aa20146-12-eq87.png) (21)We then use the property

of the derivative of the cross-correlation of two functions

(21)We then use the property

of the derivative of the cross-correlation of two functions

(22)By

identification, we obtain

(22)By

identification, we obtain  (23)where

(23)where

is defined as in Hirano et al. (2010). Thus, the

minimization of the chi-square involved in the iodine cell technique is indeed equivalent

to the maximization of the cross-correlation

is defined as in Hirano et al. (2010). Thus, the

minimization of the chi-square involved in the iodine cell technique is indeed equivalent

to the maximization of the cross-correlation  as computed in Hirano et al. (2010). This result

holds as long as the complicated fit with 13 parameters can be modeled by the fit of the

single parameter

as computed in Hirano et al. (2010). This result

holds as long as the complicated fit with 13 parameters can be modeled by the fit of the

single parameter  ,

and if the modeled line profile is symmetrical. The second condition may not be true in

general. If the asymmetry is not too strong, the integral I2

would be a small perturbation, and the result obtained by the maximization of the

cross-correlation

,

and if the modeled line profile is symmetrical. The second condition may not be true in

general. If the asymmetry is not too strong, the integral I2

would be a small perturbation, and the result obtained by the maximization of the

cross-correlation  should differ from the minimization of the chi-square by only a small constant.

should differ from the minimization of the chi-square by only a small constant.

3.2. General expression of the RM effect

To derive a general expression of the RV signal measured by the iodine technique, we use

the same model as Hirano et al. (2010), which

consists in maximizing  where

where ![\begin{equation} C(\vx) = \int \Fstar(v-\vx) \big[\Fstar(v)-f\Fpla(v-v_{\rm p})\big]\,{\rm d}v . \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/02/aa20146-12/aa20146-12-eq90.png) (24)Then, the condition

(24)Then, the condition

leads to

leads to  = f \int \frac{{\rm d}\Fstar}{{\rm d}v}(v-\vx) \Fpla(v-v_{\rm p})\,{\rm d}v . \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/02/aa20146-12/aa20146-12-eq92.png) (25)As in the previous

section, we expand

(25)As in the previous

section, we expand  in series of f:

in series of f:  At the zeroth order, we get

At the zeroth order, we get  = 0. \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/02/aa20146-12/aa20146-12-eq94.png) (26)If

ℱstar(v) is an even function, this equality gives

(26)If

ℱstar(v) is an even function, this equality gives

.

Otherwise,

.

Otherwise,  would be a small constant, depending only on the shape of the spectral lines, but not on

vp. Here, we assume that

would be a small constant, depending only on the shape of the spectral lines, but not on

vp. Here, we assume that

.

At the first order in the flux ratio f, assuming that ℱpla is

even, we obtain, with

.

At the first order in the flux ratio f, assuming that ℱpla is

even, we obtain, with  ,

,

, \label{eq.vdconv} \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/02/aa20146-12/aa20146-12-eq97.png) (27)where

(27)where

![\begin{equation} A_0 = \frac{{\rm d}}{{\rm d}\vx}\left[\frac{{\rm d}\Fstar}{{\rm d}v}\star\Fstar\right]_{\vx=0} = \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} \left(\frac{{\rm d}\Fstar}{{\rm d}v}\right)^2\,{\rm d}v . \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/02/aa20146-12/aa20146-12-eq98.png) (28)This result is more

complex than (12) because it involves the

derivatives of the stellar line profile ℱstar instead of the derivatives of a

best Gaussian fit

(28)This result is more

complex than (12) because it involves the

derivatives of the stellar line profile ℱstar instead of the derivatives of a

best Gaussian fit  which are analytical. Of course, if ℱstar is Gaussian, we retrieve the result

of the previous section (see Sect. 2.3).

which are analytical. Of course, if ℱstar is Gaussian, we retrieve the result

of the previous section (see Sect. 2.3).

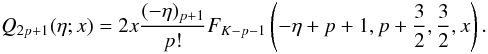

In Appendix C, we provide an analytical expression of the numerator of viodine (27) in the case where the subplanet line profile is Gaussian and for a general limb-darkening law.

4. Parameters of the subplanet line profile

The expressions of the RM effect (14) and

(27) depend on the fraction

f of the flux covered by the planet, the subplanet velocity

vp, and the dispersion βp. There

are two approaches to evaluate them. On the one hand, both the flux fraction

f and the mean velocity vp can be computed

exactly as a series of Jacobi polynomials (Giménez

2006). This is useful in the case of binary transits where the occulting object is

big. On the other hand, only the flux fraction f is derived exactly using

analytical algorithms such as the one given by (Mandel

& Agol 2002), while vp

and βp are estimated assuming uniform intensity below the

planet (Hirano et al. 2010, 2011). Then, if  are the averaged coordinates over the surface of the star covered by the planet, and

normalized to the radius of the star,

are the averaged coordinates over the surface of the star covered by the planet, and

normalized to the radius of the star,  ,

while βp is constant and represents the width

β0 of the nonrotating star line profile.

,

while βp is constant and represents the width

β0 of the nonrotating star line profile.

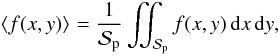

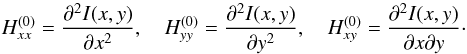

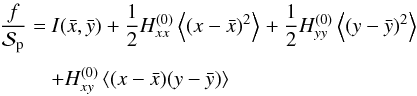

Here, we choose a compromise between the two approaches and take the slope and the curvature of the intensity below the planet into account. This gives a better estimate of vp and βp in comparison to the uniform subplanet intensity hypothesis. But also it turns out that the method provides a simple and accurate expression for the flux fraction f. Another advantage of this method is that it can be easily applied to more complex problems where the gravity-darkening or the tidal deformations of both the planet and the star are taken into account.

4.1. Method

To describe the method, we take the example of the computation of the flux fraction

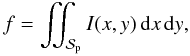

f. The expression of f reads as

(29)where

(29)where

is the surface of the stellar disk covered by the planet normalized by the square of the

radius of the star. I(x,y) is the normalized

limb-darkening of the star expressed as a function of the normalized coordinates

(x,y). For the moment, we do not need to give its expression.

is the surface of the stellar disk covered by the planet normalized by the square of the

radius of the star. I(x,y) is the normalized

limb-darkening of the star expressed as a function of the normalized coordinates

(x,y). For the moment, we do not need to give its expression.

A very rough approximation of f is obtained assuming uniform intensity

below the planet. In that case, we obtain  (30)where

(30)where

(31)are the coordinates of

the barycenter of the portion of the stellar disk covered by the planet. The formula

(30) works well for very small planets

but only during full transits (e.g. Mandel & Agol

2002). Close to the limb, the intensity I(x,y)

varies strongly with position and this approximation is not valid anymore. To overcome

this issue, we propose to make an expansion of the limb-darkening profile

I(x,y) in the vicinity of

(31)are the coordinates of

the barycenter of the portion of the stellar disk covered by the planet. The formula

(30) works well for very small planets

but only during full transits (e.g. Mandel & Agol

2002). Close to the limb, the intensity I(x,y)

varies strongly with position and this approximation is not valid anymore. To overcome

this issue, we propose to make an expansion of the limb-darkening profile

I(x,y) in the vicinity of

.

We get

.

We get  (32)where

for any function f(x,y),

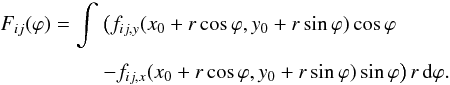

(32)where

for any function f(x,y),  (33)where

(33)where

and

and

are the components of the

Jacobian of the surface intensity I(x,y) computed at

are the components of the

Jacobian of the surface intensity I(x,y) computed at

.

Similarly, the components of the Hessian are

.

Similarly, the components of the Hessian are

(34)By construction,

(34)By construction,

and

and  are defined by

are defined by  ,

and

,

and  .

Thus, the linear terms in factor of the Jacobian

.

Thus, the linear terms in factor of the Jacobian  cancel in (32). At that point, only

cancel in (32). At that point, only  (35)remains.

The first term in (35) corresponds to the

rough approximation derived in Eq. (30).

The other terms provide a correction proportional to the square of the normalized planet

radius

(r = Rp/R⋆)

and are expected to be small.

(35)remains.

The first term in (35) corresponds to the

rough approximation derived in Eq. (30).

The other terms provide a correction proportional to the square of the normalized planet

radius

(r = Rp/R⋆)

and are expected to be small.

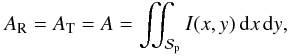

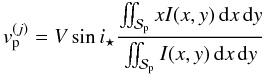

4.2. Subplanet velocity

The above method applied to I(x,y) to get the flux

fraction f can be adapted to any other function. For example, the

subplanet velocity is defined by  (36)We denote

(36)We denote

,

,

,

and

,

and  as the components of the Hessian of xI(x,y) at the

averaged position

as the components of the Hessian of xI(x,y) at the

averaged position  (31). Using the expression of

f (35), at first order

in r2, we get

(31). Using the expression of

f (35), at first order

in r2, we get  (37)The

denominator

(37)The

denominator  in (37), as well as the terms in

in (37), as well as the terms in

,

,

,

and

,

and  ,

come from the expansion of the denominator of (36).

,

come from the expansion of the denominator of (36).

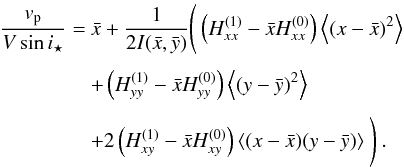

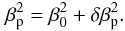

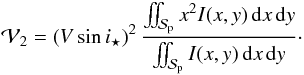

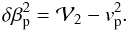

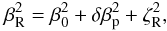

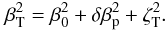

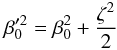

4.3. Width of the subplanet line profile

The width of the subplanet line profile βp is a combination

of the width of the nonrotating line profile β0 and a

correction δβp due to the rotational

broadening  (38)We define

(38)We define

as the average of the square of the subplanet velocity

as the average of the square of the subplanet velocity  (39)With this

notation, we have

(39)With this

notation, we have  (40)Noting

(40)Noting

,

,

,

and

,

and  ,

the components of the Hessian of

x2I(x,y) at the averaged

coordinates

,

the components of the Hessian of

x2I(x,y) at the averaged

coordinates  ,

the expression of

,

the expression of  reads as

reads as  (41)At

first order, the

(41)At

first order, the  in

in  (39) cancels with the square of

(39) cancels with the square of

in the expression of vp (37). Thus, at first order,

δβp vanishes and the width of the subplanet

profile is equal to the width of the nonrotating star β0.

However, the quadratic terms do not cancel, and this provides an estimation of the

contribution of the rotational broadening to the actual width of the subplanet profile.

in the expression of vp (37). Thus, at first order,

δβp vanishes and the width of the subplanet

profile is equal to the width of the nonrotating star β0.

However, the quadratic terms do not cancel, and this provides an estimation of the

contribution of the rotational broadening to the actual width of the subplanet profile.

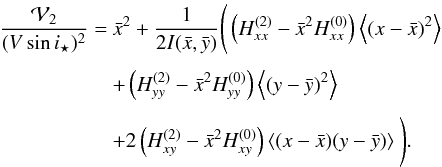

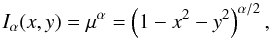

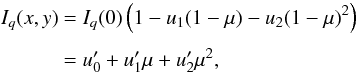

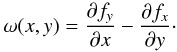

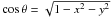

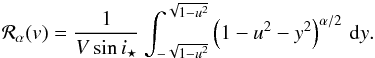

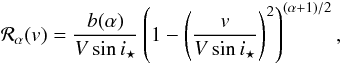

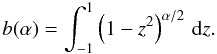

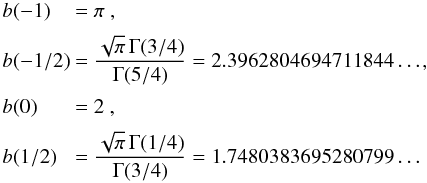

4.4. Limb-darkening and its derivatives

As we saw above, the determination of the subplanet profile depends on the limb-darkening

law and its second derivatives. In this section, we provide generic formulas assuming that

the limb-darkening law is a linear combination of functions

Iα(x,y) defined by

(42)where

(42)where

is the cosine of the angle between the normal of the stellar surface at

(x,y) and the observer.

is the cosine of the angle between the normal of the stellar surface at

(x,y) and the observer.

The second derivatives  ,

,

,

and

,

and  of

xnIα(x,y)

are given Table 1. These are the ones that are

needed to compute the flux fraction f, the subplanet velocity

vp and the dispersion βp. In

practice, only the cases n = 0,1,2 are

used.

of

xnIα(x,y)

are given Table 1. These are the ones that are

needed to compute the flux fraction f, the subplanet velocity

vp and the dispersion βp. In

practice, only the cases n = 0,1,2 are

used.

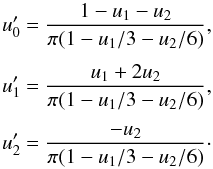

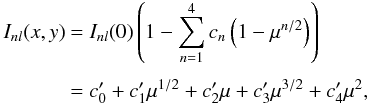

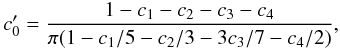

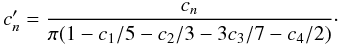

From these general formulas, one can derive the expressions for the quadratic

limb-darkening which reads as  (43)with

Iq(0) the central intensity such that

Iq(x,y) is normalized to

one. By identification, we get

(43)with

Iq(0) the central intensity such that

Iq(x,y) is normalized to

one. By identification, we get  (44)Equivalently,

the so-called nonlinear limb-darkening is usually expressed as

(44)Equivalently,

the so-called nonlinear limb-darkening is usually expressed as

(45)with

(45)with

(46)and for

1 ≤ n ≤ 4,

(46)and for

1 ≤ n ≤ 4,  (47)The

normalizations in (44), (46), and (47) have been deduced from the integral of each

Iα(x,y) over the entire

disk of the star

(47)The

normalizations in (44), (46), and (47) have been deduced from the integral of each

Iα(x,y) over the entire

disk of the star  (48)

(48)

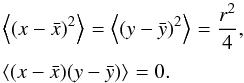

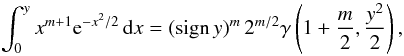

4.5. Averaged coordinates and covariances

The last quantities that need to be computed in order to get the subplanet line profiles

are the averaged coordinates  ,

,

, the

variances

, the

variances  ,

,

,

and the covariance

,

and the covariance  .

For that, we distinguish two cases.

.

For that, we distinguish two cases.

4.5.1. During a full transit

In the case of a full transit, i.e., when the disk of the planet is fully inside the

disk of the star, the problem gets simpler since the integrals (33) have to be computed over a uniform disk

of area  and centered on the coordinates

(x0,y0) of

the planet. We get

and centered on the coordinates

(x0,y0) of

the planet. We get  ,

and

,

and  (49)

(49)

4.5.2. During ingress or egress

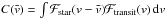

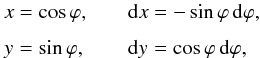

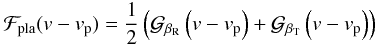

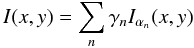

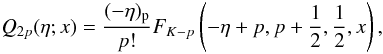

If the disk of the planet is crossing the limb of the star, the area where the integrals of the form (33) are computed is not circular (see the shaded area in Fig. 2). In that case, we use the very powerful method of Pál (2012), which gives expressions that also work also for mutual transits.

|

Fig. 2 Definition of the angles |

We recall briefly the method that relies on Green’s theorem converting an integral over

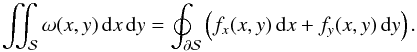

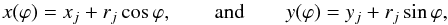

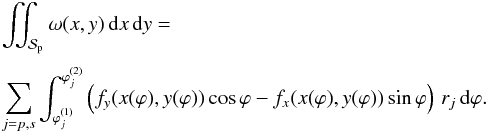

a surface into an integral over the contour of that surface:  (50)In this equation,

(50)In this equation,

is the boundary of

is the boundary of  ,

and ω(x,y) the exterior derivative of

f(x,y) = (fx,fy)

defined by

,

and ω(x,y) the exterior derivative of

f(x,y) = (fx,fy)

defined by  (51)When the planet is

crossing the limb of the star, the boundary is the union of two circular arcs. One of

them follows the edge of the planet centered on

(x0,y0) with

radius r. The coordinates of any points of this arc and the tangent

vectors are of the form

(51)When the planet is

crossing the limb of the star, the boundary is the union of two circular arcs. One of

them follows the edge of the planet centered on

(x0,y0) with

radius r. The coordinates of any points of this arc and the tangent

vectors are of the form  (52)The

angle ϕ varies between two limits

(52)The

angle ϕ varies between two limits

and

and

,

corresponding to the intersections A and B between the

circumferences of the planet and of the star, respectively (see Fig. 2). The second arc fellows the edge of the star and is

parameterized by the coordinates

,

corresponding to the intersections A and B between the

circumferences of the planet and of the star, respectively (see Fig. 2). The second arc fellows the edge of the star and is

parameterized by the coordinates

(53)with

ϕ going from

(53)with

ϕ going from  to

to

associated to the intersections B and A, respectively.

associated to the intersections B and A, respectively.

More generally, if we denote

(xj,yj)j = p,s

as the centers of the arcs, and

(rj)j = p,s

as their radii such that  (54)we obtain (Pál 2012)

(54)we obtain (Pál 2012)

(55)Here,

we are interesting in the cases where ω(x,y) stands

for 1, x, y, x2,

y2, or xy. The field vectors

f(x,y) associated to those

ω(x,y) are not uniquely determined. We choose

(55)Here,

we are interesting in the cases where ω(x,y) stands

for 1, x, y, x2,

y2, or xy. The field vectors

f(x,y) associated to those

ω(x,y) are not uniquely determined. We choose

, (− xy,0),

(0,xy), (− x2y,0),

(0,xy2), and

, (− xy,0),

(0,xy), (− x2y,0),

(0,xy2), and

,

respectively. We denote

ωij = xiyj

and fij(x,y)

as the functions whose exterior derivative is

ωij. The integral of

fij along a circular arc

reads as

,

respectively. We denote

ωij = xiyj

and fij(x,y)

as the functions whose exterior derivative is

ωij. The integral of

fij along a circular arc

reads as  (56)Since

the fij are polynomials in

x and y, the

Fij can be computed using the

recurrence relations provided by Pál (2012). The

results are displayed in Table 2 for

i = 0,1,2, and

j = 0,1,2. From them, one can

derive the quantities present in the expressions of the flux fraction

f, the subplanet velocity vp and the width

βp:

(56)Since

the fij are polynomials in

x and y, the

Fij can be computed using the

recurrence relations provided by Pál (2012). The

results are displayed in Table 2 for

i = 0,1,2, and

j = 0,1,2. From them, one can

derive the quantities present in the expressions of the flux fraction

f, the subplanet velocity vp and the width

βp:

(57)

(57)

5. Comparison with simulations

5.1. Transit light curve

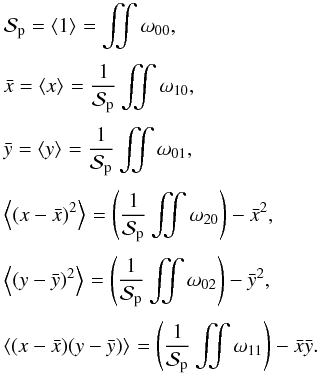

Although it was not the main goal of this present work, in the derivation of a precise modeling of the RM effect, we obtained a new expression of the flux fraction f occulted by a planet during a transit (see Eq. (35)). In comparison to existing formulas that are exact (e.g. Mandel & Agol 2002; Pál 2012), the one of this paper relies on an expansion of the intensity in the vicinity of the averaged position of the planet. We thus expect our formulation to be less precise.

|

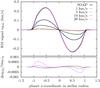

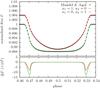

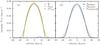

Fig. 3 Transit light curves for r = 0.1 and quadratic limb-darkening with two sets of coefficients u1, u2. The solid curves in red and in green are obtained from the approximation (35), while the black open circles are computed using the routine of Mandel & Agol (2002). |

Figure 3 shows the comparison between the approximation (35) and the exact formula derived by Mandel & Agol (2002). By eye, it is not possible to distinguish between the two approaches. In the residuals, however, we can see that the maximum of deviation occurs close to the limb, more exactly, when the edge of the planet is tangent to that of the star. Indeed, at the border of the star, the limb-darkening becomes steeper and steeper, and the derivatives ∂xIα(x,y) and ∂yIα(x,y) even go to infinity for α < 2. Nevertheless, this singularity is smoothed out by the decrease in the overlapping area between the planet and the star disks during ingress and egress.

One advantage of the present formula is that it can be easily generalized to more complex problems, as in the cases of a distorted planet, distorted star, important gravity limb-darkening, and so on. For our purpose, it provides an accurate enough estimation of the flux that can be used to derive the RM effect.

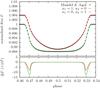

5.2. Subplanet profile

We checked the accuracy of our new formulas of the subplanet velocity

vp (37) and

the width  with

δβp given by (40). For that, we used the software called SOAP, for Spot Oscillation

And Planet (Boisse et al. 2012), to produce

artificial data as close as possible to real observations. This code is a numerical tool

that models radial velocity and photometry observations of stars with spots. It has been

updated recently to also model the effect of a planet transiting a spotted star, and was

renamed SOAP-T (Oshagh et al. 2013). Briefly, the

code divides the disk of the star into a grid. To each cell of that grid, a Gaussian

profile with a width β0 and amplitude

I(x,y) (in our notation) is assigned. This represents

the intrinsic line profile of the nonrotating star as detected by the instrument. These

lines are then shifted in velocity according to their position with respect to the

spin-axis and the Vsini⋆

of the star. All the lines of the cells uncovered by any spots or planets are added

together to produce an artificial CCF that is then fitted by a Gaussian to derive a radial

velocity.

with

δβp given by (40). For that, we used the software called SOAP, for Spot Oscillation

And Planet (Boisse et al. 2012), to produce

artificial data as close as possible to real observations. This code is a numerical tool

that models radial velocity and photometry observations of stars with spots. It has been

updated recently to also model the effect of a planet transiting a spotted star, and was

renamed SOAP-T (Oshagh et al. 2013). Briefly, the

code divides the disk of the star into a grid. To each cell of that grid, a Gaussian

profile with a width β0 and amplitude

I(x,y) (in our notation) is assigned. This represents

the intrinsic line profile of the nonrotating star as detected by the instrument. These

lines are then shifted in velocity according to their position with respect to the

spin-axis and the Vsini⋆

of the star. All the lines of the cells uncovered by any spots or planets are added

together to produce an artificial CCF that is then fitted by a Gaussian to derive a radial

velocity.

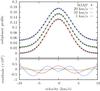

With SOAP-T, we produced the CCF of a star with a transiting planet at different positions of the planet on the disk. We also generated the CCF of the same star while the planet is not transiting, and by taking the difference, we got the subplanet profile. Such profiles are displayed in Fig. 4 for different values of Vsini⋆. Unless specified explicitly, here, and in all the following simulations, the star is a solar-type star with a quadratic limb-darkening law whose coefficients are u1 = 0.38, u2 = 0.3, and an intrinsic line width without rotation of β0 = 3 km s-1. The planet is a Jupiter evolving in the equatorial plane of its star, its radius is r = Rp/Rstar = 0.1099. In Fig. 4, the subplanet line profiles of low rotating stars are Gaussian. This results from the hypothesis of SOAP-T, which assumes Gaussian intrinsic line profiles. But we observe that the Gaussian shape holds even for Vsini⋆ = 20 km s-1, which validates our assumption leading to Eq. (14).

|

Fig. 4 Example of subplanet line profiles obtained with SOAP-T (circles), compared with Gaussian profiles (curves) for different stellar Vsini⋆. |

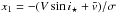

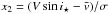

To each of the artificial subplanet profiles generated with SOAP-T, we also computed the mean velocity vp and the dispersion βp, to be compared with our formulas (37) and (40). Figure 5 shows the results for vp after normalization to remove the effect of the Vsini⋆ of the star. We checked that the figure is indeed unchanged up to Vsini⋆ = 20 km s-1. The numerical outputs obtained with SOAP-T are plotted against two different analytical approximations denoted S0 and S2. In S0, the surface brightness of the star is taken uniform below the disk of the planet, while in S2, the second derivatives are taken into account as in (37). We observe that where the error is maximal, close to the limb, S2 improves the determination of vp by about a factor 3 with respect to S0. In the case r = 0.1 and Vsini⋆ = 10 km s-1, the maximal error provided by S2 is about 20 m/s which represents a relative difference of 0.2%.

|

Fig. 5 Subplanet velocity vp produced with SOAP-T (blue points), approximation S0 assuming uniform intensity below the disk of the planet (red curve), and approximation S2 taking the second derivatives of the stellar surface brightness into account, Eq. (37) (green curve). |

In the case of the dispersion βp, the difference between the

estimation derived assuming uniform (S0) and nonuniform

(S2) brightness below the planet disk is more evident (see

Fig. 6). Indeed, in the former case,

βp remains constant and equal to the width

β0 of the nonrotating star line profile, while we observe

that for the simulated and the modeled line profiles, the shape of

βp as a function of the orbital phase looks like a trapezoid

with the large base at β0 and the maximum at approximately

.

.

|

Fig. 6 Subplanet dispersion βp produced with SOAP-T (blue points), approximation S0 (red curve), and approximation S2, Eq. (40), (green curve). |

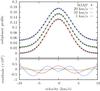

5.3. Rossiter-McLaughlin effect

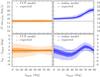

We now compare our analytical expression of the Rossiter-McLaughlin effect vCCF (14) with signals generated with SOAP-T, which simulates the reduction analysis of the CCF technique numerically.

|

Fig. 7 RM signals produced with SOAP-T (solid black curves) for different Vsini⋆, and results of vCCF (14) (different dashed curves). |

Figure 7 displays the results for different Vsini⋆. As long as Vsini⋆ is below or equal to 10 km s-1, the error induced by the analytical formula remains lower than ~1 m/s, which is close to the magnitude of the precision of RV measurements. In that case, the analytical approximations are almost indistinguishable from the numerical simulations. However, for larger Vsini⋆, the agreement between numerical signals and analytical ones is weaker. For example, when Vsini⋆ = 20 km s-1, the analytical approximation leads to a maximal error of 10 m/s, which is 5% of the amplitude of the signal. Nevertheless, it should also be noted that for fast-rotating stars the spreading of the spectral lines over the detectors decreases the precision of the measurements. In any case, the analytical expression vCCF brings a definite improvement over other formulas, which have not been designed to simulate the CCF technique as we see in the following section.

|

Fig. 8 Simple models of line profiles. a) Rotation kernel ℛ(v) with Vsini⋆ = 15 km s-1 in solid red, stellar line profile assuming β0 = 2.6 km s-1 in dashed green, subplanet line profile ℱpla(v) with βp = 2.71 km s-1 in dash-dotted blue. b) ℱtransit = ℱstar − fℱpla modeling an average line profile observed with HIRES in solid black, and a CCF observed with HARPS in dotted cyan. The same with β0 = 4.5 km s-1 and βp = 4.56 km s-1 represents a CCF observed by CORALIE, in dashed violet. |

|

Fig. 9 Comparison of a simulated RM signal observed by different techniques and/or

instruments. We used the line profiles of Fig. 8b. The open diamonds, circles and squares represent the RM signal

obtained numerically with the iodine cell technique on the HIRES line profile, and

with the Gaussian fit to the HARPS, or CORALIE, CCFs, respectively. In a)

the gray curve corresponds to the numerical maximization of the

cross-correlation |

5.4. Comparison between different techniques

To highlight the effect of the instrument and of the data reduction analysis, we generated different models of line profile and compared the RM signals computed numerically with the results of the analytical formulas vCCF (14) and viodine (27). In our examples, the line profiles are of three types: ℱHIRES(v), ℱHARPS(v), and ℱCORALIE(v). They are associated to three RM signals: vHIRES, vHARPS, and vCORALIE, respectively. It should be stressed that the goal is not to reproduce the lines observed by those instruments exactly, but to capture their main characteristics. On the one hand, HIRES and HARPS are two spectrographs with high resolutions that we assume to be identical with a width β0 = 2.6 km s-1 for nonrotating solar-type stars. On the other hand, the resolution of CORALIE is about twice lower, and the intrinsic width of the same stars is about β0 = 4.5 km s-1 (Santos et al. 2002). We consider a star with Vsini⋆ = 15 km s-1, which is adapted to our illustration. Finally, the transiting planet is a Jupiter-like planet with a radius Rp = 0.1Rstar.

Figure 8 shows the simulated line profiles. The

panel 8a displays the rotation kernel

ℛ(v), a stellar profile ℱstar(v) with

β0 = 2.6 km s-1, and a subplanet profile

ℱpla(v − vp) multiplied by the

flux fraction f, and computed with

.

Figure 8b depicts the resulting line profiles

during transit ℱHIRES(v),

ℱHARPS(v), and ℱCORALIE(v).

Following our hypothesis, ℱHIRES(v) is identical to

ℱHARPS(v).

.

Figure 8b depicts the resulting line profiles

during transit ℱHIRES(v),

ℱHARPS(v), and ℱCORALIE(v).

Following our hypothesis, ℱHIRES(v) is identical to

ℱHARPS(v).

From the simulated line profiles, we derived RM signals numerically. The signal

vHIRES was obtained from ℱHIRES using the iodine

cell technique, i.e., by fitting the best Doppler shift between a line without transit

deformation, and the line profiles computed during transit. Both

vHARPS, and vCORALIE are the

results of applying the CCF technique, i.e., a numerical fit between a shifted Gaussian

and ℱHARPS and ℱCORALIE, respectively. We also generated

by maximizing the cross-correlation

by maximizing the cross-correlation  between the line profiles ℱHIRES at and out of transit. These four RM signals

are represented in Fig. 9a. It is notable that the

RM effects associated to the three instruments are all different. The variation between

vHARPS and vCORALIE is only due

to the change in resolution. However, in the case of vHIRES

and vHARPS, the simulated lines are exactly identical. The

observed difference in the RM signal is the result of the chosen data reduction technique.

Figure 9a also confirms that the maximum of the

cross-correlation

between the line profiles ℱHIRES at and out of transit. These four RM signals

are represented in Fig. 9a. It is notable that the

RM effects associated to the three instruments are all different. The variation between

vHARPS and vCORALIE is only due

to the change in resolution. However, in the case of vHIRES

and vHARPS, the simulated lines are exactly identical. The

observed difference in the RM signal is the result of the chosen data reduction technique.

Figure 9a also confirms that the maximum of the

cross-correlation  gives the same result as the iodine cell technique (when the stellar lines are

symmetrical) since

gives the same result as the iodine cell technique (when the stellar lines are

symmetrical) since  .

.

The last three panels of Fig. 9 represent the comparison between the simulated RM signals and the analytical formulas vCCF (14), and viodine (27) associated to the CCF and the iodine cell technique, respectively. We observe that the formulas adapted to the analysis routines are in good agreement with the respective simulations. We also notice that for CORALIE, whose resolution is lower, the two analytical formulas give roughly the same result. This is because the stellar line is less affected by the rotational kernel and is more Gaussian. We show that, in that case, the two methods should indeed provide the same result (see Sect. 2.3).

From this study, we conclude that a given star observed by two different techniques should present two distinct RM signals. To date, this notable result has not been seen since the instruments with the highest signal-to-noise, HIRES and HARPS, are located in two different hemispheres. This makes it difficult to observe the same stars. For those observed with other instruments, the expected gaps are diluted by the measurement uncertainties. Nevertheless, with the advent of HARPS-North, we may observe such discrepancies in the future.

5.5. Biases on fitted parameters

As a final test, we simulated artificial data from either the CCF or the iodine cell model, and we fit each of these data with the two models separately. The goal is not to perform an exhaustive study of the biases introduced by the application of a wrong model in the process of fitting data, but to give an example with some typical parameters.

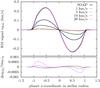

For this illustration, we considered only one set of parameters. As in the previous section, the star has Vsini⋆ = 15 km s-1 with intrinsic line width β0 = 2.6 km s-1. We chose a quadratic limb-darkening characterized by u1 = 0.69 and u2 = 0.0. The planet’s radius is taken equal to Rp = 0.1Rstar. The impact parameter of the orbit is assumed to be 0.3Rstar. For information, this value is that of a planet with a semi-major axis a = 4 Rstar and an inclination i = 85.7 deg. All these parameters were fixed throughout all the simulations. Only the projected spin-orbit angle λinput was varied from 0 to 90 degrees by steps of ten degrees. For each value of λinput, and each model, 1000 datasets were generated with a Gaussian noise of 10 m/s. Each simulation contains 50 points, among which 32 are inside the transit and 18 outside. In each case, we fit both the Vsini⋆ and the projected spin-orbit angle.

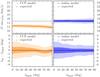

Figure 10 shows the results of this analysis in the

case where the data are generated with the CCF model vCCF

(Eq. (14)). As expected, the parameters

recovered with the appropriate model are accurate, while those deduced from the iodine

cell technique formulas are biased. The bias on

Vsini⋆ is

systematically positive and also the most important, especially at large projected

spin-orbit angle (λinput ≈ 90 deg) where we get

(Vsini⋆)fit = 20.7 ± 0.5 km s-1

instead of 15 km s-1. One can notice that this agrees with the results of,

e.g., Simpson et al. (2010) who applied the model

of Hirano et al. on WASP-3 observed with SOPHIE.

They fit a  km s-1

while the spectroscopic value is only 13.4 ± 1.5 km s-1. On the other hand, the

bias on the fitted projected spin-orbit angle λfit remains

within 2-σ. This parameter is thus less affected by the model.

km s-1

while the spectroscopic value is only 13.4 ± 1.5 km s-1. On the other hand, the

bias on the fitted projected spin-orbit angle λfit remains

within 2-σ. This parameter is thus less affected by the model.

The difference in behavior between (Vsini⋆)fit and λfit is more evident in Fig. 11. In that case, the data were simulated with the formulas associated to the iodine cell technique: viodine (Eq. (27)). As in the previous test, using the same model for both the generation of the data and the fit, leads to very accurate estimations of the parameters, while the application of the wrong model introduces biases. The (Vsini⋆)fit is systematically negative as we could expect since the situation is the opposite of the one in the previous paragraph. Nevertheless, the error is smaller. In the worst case, we get (Vsini⋆)fit = 11.9 ± 0.3 km s-1, which represents on error of the order of 3 km s-1, while it was almost 6 km s-1 in the previous example. The situation is similar for λfit. We observe small biases anticorrelated with those of the previous test, but now, the inaccuracy remains within 1-σ.

We stress that we only fit two parameters in this study, while the others are fixed to their exact values. We already observe that the best fits tend to compensate for inaccurate models by introducing biases. With more free parameters, there are more possibilities to balance the model, and it is thus difficult to predict the behavior of the fit. Since the models are not linear, we should expect the presence of several local minima. Eventually, in some of them, the projected spin-orbit angle might be more biased than in our tests. This should be analyzed on individual case bases, which is not the goal of this paper.

|

Fig. 10 Results of the fits with two different models of mock data generated by the CCF technique formulas. In each panel, the area with the lightest color represents the two-sigma limit, the darkest color is the one-sigma threshold, and the curve is the best value. |

6. Conclusion

One of the main objectives of this paper has been to highlight that there is no unique way of measuring RM effects and that different techniques provide different values of RV anomalies. RM signals should thus be analyzed using the appropriate model to avoid any biases, at least in Vsini⋆. This is particularly important in the case of low-impact parameters (planet passing close to the center of its star) since then, the projected spin-orbit angle only depends on the amplitude of the RM signal.

We provided a new analytical formula specially designed to model RV anomalies obtained by fitting a Gaussian function to the CCF, as in the analysis routines of HARPS and SOPHIE. We also revisited the modeling of the iodine cell technique, as used with HDS and HIRES, for which we derived an analytical expression adapted to non-Gaussian stellar line profiles. An effort was made to model the effect of the rotation of the star on the width of the subplanet line profile. Since our formulas do not rely on any expansion in powers of the subplanet velocity vp, our results remain stable even for fast-rotating stars.

The advantage of having a purely analytical expression to model the RM effect is the rapidity of computation. It can thus be used to analyze a large sample of RM signals uniformly. As a complement to this paper, we make our code accessible to the community as a free open source software package. This is a library called ARoME, an acronym for Analytical Rossiter-McLaughlin Effect, designed to generate analytical RM signals based on the formulas of the paper. It also includes the effect of macro-turbulence as described in the Appendix A. The library provides a C interface and, optionally, a Fortran 77 or 2003 interface to be called by an application. The fully documented package can be downloaded from the webpage http://www.astro.up.pt/resources/arome.

Besides the modeling of the RM effect, we also analytically derived a new expression for transit light curves (35). Although this expression is the result of a Taylor expansion of the intensity and is only adapted to small planets, it gives good approximations. Moreover, the expression is general enough to be easily extended to more complex problems.

In this paper, unit Gaussians are defined by  , while in (Hirano et al. 2010), they are defined by

, while in (Hirano et al. 2010), they are defined by

. There is thus a

difference of a factor 2 in the parenthesis of Eq. (2) with respect to (Hirano et al.

2010, Eq. (36)).

. There is thus a

difference of a factor 2 in the parenthesis of Eq. (2) with respect to (Hirano et al.

2010, Eq. (36)).

Acknowledgments

We thank Amaury Triaud for helpful discussions and feedback on this project. We also acknowledge the support by the European Research Council/European Community under the FP7 through Starting Grant agreement number 239953, as well as from Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) in the form of grant reference PTDC/CTE-AST/098528/2008. NCS also acknowledges the support from FCT through program Ciência 2007 funded by FCT/MCTES (Portugal) and POPH/FSE (EC). MM and IB would furthermore like to thank the FCT for fellowships SFRH/BPD/71230/2010 and SFRH/BPD/81084/2011, respectively.

References

- Albrecht, S., Winn, J. N., Johnson, J. A., et al. 2012, ApJ, 757, 18 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Baranne, A., Queloz, D., Mayor, M., et al. 1996, A&AS, 119, 373 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Beaugé, C., & Nesvorný, D. 2012, ApJ, 751, 119 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Boisse, I., Bonfils, X., & Santos, N. C. 2012, A&A, 545, A109 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bundy, K. A., & Marcy, G. W. 2000, PASP, 112, 1421 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R. P., Marcy, G. W., Williams, E., et al. 1996, PASP, 108, 500 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrycky, D., & Tremaine, S. 2007, ApJ, 669, 1298 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Giménez, A. 2006, ApJ, 650, 408 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gray, D. F. 2005, The Observation and Analysis of Stellar Photospheres (New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press) [Google Scholar]

- Hébrard, G., Bouchy, F., Pont, F., et al. 2008, A&A, 488, 763 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano, T., Suto, Y., Taruya, A., et al. 2010, ApJ, 709, 458 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano, T., Suto, Y., Winn, J. N., et al. 2011, ApJ, 742, 69 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Holt, J. 1893, Astronomy and Astro-Physics, XII, 646 [Google Scholar]

- Kopal, Z. 1942, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci., 28, 133 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [MathSciNet] [Google Scholar]

- Mandel, K., & Agol, E. 2002, ApJ, 580, L171 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, D. B. 1924, ApJ, 60, 22 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasawa, M., & Ida, S. 2011, ApJ, 742, 72 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Naoz, S., Farr, W. M., Lithwick, Y., Rasio, F. A., & Teyssandier, J. 2011, Nature, 473, 187 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta, Y., Taruya, A., & Suto, Y. 2005, ApJ, 622, 1118 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Oshagh, M., Boisse, I., Boué, G., et al. 2013, A&A, 549, A35 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Pál, A. 2012, MNRAS, 420, 1630 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe, F., Mayor, M., Galland, F., et al. 2002, A&A, 388, 632 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Press, W. H., Teukolsky, S. A., Vetterling, W. T., & Flannery, B. P. 1992, Numerical recipes in C (2nd ed.): the art of scientific computing (New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press) [Google Scholar]

- Queloz, D., Eggenberger, A., Mayor, M., et al. 2000, A&A, 359, L13 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Rasio, F. A., & Ford, E. B. 1996, Science, 274, 954 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossiter, R. A. 1924, ApJ, 60, 15 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Santos, N. C., Mayor, M., Naef, D., et al. 2002, A&A, 392, 215 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, E. K., Pollacco, D., Hébrard, G., et al. 2010, MNRAS, 405, 1867 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Triaud, A. H. M. J. 2011, A&A, 534, L6 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Triaud, A. H. M. J., Collier Cameron, A., Queloz, D., et al. 2010, A&A, 524, A25 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Winn, J. N., Johnson, J. A., Fabrycky, D., et al. 2009, ApJ, 700, 302 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Winn, J. N., Fabrycky, D., Albrecht, S., & Johnson, J. A. 2010, ApJ, 718, L145 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y., & Lithwick, Y. 2011, ApJ, 735, 109 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y., & Murray, N. 2003, ApJ, 589, 605 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

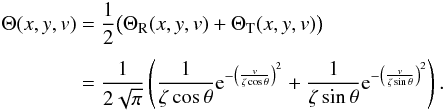

Appendix A: Macro-turbulence

Here, we study the effect of macro-turbulence on the Rossiter-McLaughlin signal. We

consider only the “radial-tangential” model as in (Hirano

et al. 2011). In that case, if we denote ℱ0(v) as the

line profile of the nonrotating star without macro-turbulence, the subplanet line profile

reads as , \label{eq.FplaM} \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/02/aa20146-12/aa20146-12-eq275.png) (A.1)where

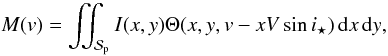

M(v) is the rotation-turbulence kernel given by (Gray 2005),

(A.1)where

M(v) is the rotation-turbulence kernel given by (Gray 2005),

(A.2)and

(A.2)and  (A.3)We

highlight the different dependencies on (x,y), on the one hand, through

(A.3)We

highlight the different dependencies on (x,y), on the one hand, through

and

and  ,

and on the velocity v, on the other. The coordinates

(x,y) are normalized by the radius of the star. Since Θ is the sum of

two Gaussians ΘR and ΘT associated to the radial and the tangential

broadenings, respectively, we also split M(v) into two

parts

,

and on the velocity v, on the other. The coordinates

(x,y) are normalized by the radius of the star. Since Θ is the sum of

two Gaussians ΘR and ΘT associated to the radial and the tangential

broadenings, respectively, we also split M(v) into two

parts  (A.4)such that

MR(v) is associated to ΘR, and

MT(v) is associated to ΘT.

(A.4)such that

MR(v) is associated to ΘR, and

MT(v) is associated to ΘT.

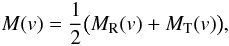

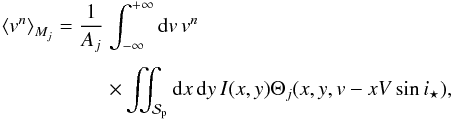

Now, we compute the moments of

(Mj(v))j = R,T

as in Sect. 4 to evaluate the effect of the

rotation-turbulence kernel on the subplanet profile. We have  (A.5)where

Aj is a normalization constant whose

expression is

(A.5)where

Aj is a normalization constant whose

expression is  (A.6)Inverting the

integrals, we get, for the normalization,

(A.6)Inverting the

integrals, we get, for the normalization,

(A.7)Since

Θj(x,y,v) (A.3) is normalized, the inner integral on the velocity is one. It thus

remains only

(A.7)Since

Θj(x,y,v) (A.3) is normalized, the inner integral on the velocity is one. It thus

remains only  (A.8)as in Sect. 4. We now focus on the numerator of (A.5). By construction,

(A.8)as in Sect. 4. We now focus on the numerator of (A.5). By construction,

. Then,

using the inversion of integrals, we get

. Then,

using the inversion of integrals, we get

![\appendix \setcounter{section}{1} \begin{eqnarray} v_{\rm p}^{(j)} := \moy{M_j}{v} &=& \frac{1}{A} \iint_{\Spla} {\rm d}x\,{\rm d}y\,\bigg[I(x,y) \notag\\ && \times\, \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} {\rm d}v\,v\, \Theta_j(x,y,v-xV\sin i_\star) \bigg] . \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/02/aa20146-12/aa20146-12-eq295.png) (A.9)The

inner integral over the velocity v gives

xVsini⋆, we have thus

(A.9)The

inner integral over the velocity v gives

xVsini⋆, we have thus

(A.10)for

each broadening: radial (j = R) and tangential

(j = T). This is identical to (36). Finally, the second moment reads as

(A.10)for

each broadening: radial (j = R) and tangential

(j = T). This is identical to (36). Finally, the second moment reads as

![\appendix \setcounter{section}{1} \begin{equation} \EQM{ {\cal V}_2^{(j)} := \moy{M_j}{v^2} = \frac{1}{A} &\iint_{\Spla} {\rm d}x\,{\rm d}y\, \bigg[ I(x,y) \crm & \times \int_{-\infty}^{+\infty} {\rm d}v\,v^2\Theta_j(x,y,v-xV\sin i_\star)\bigg] . } \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/02/aa20146-12/aa20146-12-eq300.png) (A.11)The

inner integral gives

(A.11)The

inner integral gives  (A.12)for the

radial broadening, and

(A.12)for the

radial broadening, and  (A.13)for the