| Issue |

A&A

Volume 538, February 2012

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A66 | |

| Number of page(s) | 14 | |

| Section | Cosmology (including clusters of galaxies) | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201117312 | |

| Published online | 03 February 2012 | |

Evolution of the observed Lyα luminosity function from z = 6.5 to z = 7.7: evidence for the epoch of reionization?⋆

1

Laboratoire d’Astrophysique de Marseille, CNRS UMR 7326, Université

d’Aix-Marseille, 38 rue Frédéric

Joliot-Curie, 13388

Marseille Cedex 13,

France

2

Steward Observatory, University of Arizona,

933 N. Cherry Ave, Tucson, AZ

85721,

USA

3

Laboratoire d’astrophysique, École Polytechnique Fédérale de

Lausanne (EPFL), Observatoire de Sauverny, 1290

Versoix,

Switzerland

4

INAF Osservatorio Astronomico di Roma,

via Frascati 33, 00040

Monteporzio ( RM), Italy

5

European Southern Observatory, Karl-Schwarzschild Strasse, 85748

Garching bei München,

Germany

6

Dark Cosmology Centre, Niels Bohr Institute, Copenhagen

University, Juliane Maries Vej

30, 2100

Copenhagen Ø,

Denmark

7

Departamento de Astrofísica, Facultad de CC, Físicas, Universidad

Complutense de Madrid, 28040

Madrid,

Spain

8

School of Earth and Space Exploration, Arizona State University,

Tempe, AZ

85287,

USA

9

Australian Astronomical Observatory, Epping, NSW

1710,

Australia

10

Institute of Astronomy, Madingley Road, Cambridge

CB3 0HA,

UK

11

Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of

Victoria, Elliot Building, 3800

Finnerty Road, Victoria, BC,

V8P 1A1,

Canada

Received:

21

May

2011

Accepted:

19

September

2011

Aims. Lyα emitters (LAEs) can be detected out to very high redshifts during the epoch of reionization. The evolution of the LAE luminosity function with redshift is a direct probe of the Lyα transmission of the intergalactic medium (IGM), and therefore of the IGM neutral-hydrogen fraction. Measuring the Lyα luminosity function (LF) of Lyα emitters at redshift z = 7.7 therefore allows us to constrain the ionizing state of the Universe at this redshift.

Methods. We observed three 7'.5 × 7'.5 fields with the HAWK-I instrument at the VLT with a narrow band filter centred at 1.06 μm and targeting Lyα emitters at redshift z ~ 7.7. The fields were chosen for the availability of multiwavelength data. One field is a galaxy cluster, the Bullet Cluster, which allowed us to use gravitational amplification to probe luminosities that are fainter than in the field. The two other fields are subareas of the GOODS Chandra Deep Field South and CFHTLS-D4 deep field. We selected z = 7.7 LAE candidates from a variety of colour criteria, in particular from the absence of detection in the optical bands.

Results. We do not find any LAE candidates at z = 7.7 in ~2.4 × 104 Mpc3 down to a narrow band AB magnitude of ~26, which allows us to infer robust constraints on the Lyα LAE luminosity function at this redshift.

Conclusions. The predicted mean number of objects at z = 6.5, derived from somewhat different luminosity functions of Hu et al. (2010, ApJ, 725, 394), Ouchi et al. (2010, ApJ, 723, 869), and Kashikawa et al. (2011, ApJ, 734, 119) are 2.5, 13.7, and 11.6, respectively. Depending on which of these luminosity functions we refer to, we exclude a scenario with no evolution from z = 6.5 to z = 7.7 at 85% confidence without requiring a strong change in the IGM Lyα transmission, or at 99% confidence with a significant quenching of the IGM Lyα transmission, possibly from a strong increase in the high neutral-hydrogen fraction between these two redshifts.

Key words: methods: observational / early Universe / galaxies: high-redshift / techniques: image processing / galaxies: luminosity function, mass function / dark ages, reionization, first stars

Based on observations collected at the European Organisation for Astronomical Research in the Southern Hemisphere (ESO), Chile, Prog-Id 181.A-0485, 181.A-0717, 60.A-9284, 084.A-0749. Based on observations obtained at the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope (CFHT) which is operated by the National Research Council (NRC) of Canada, the Institut National des Sciences de l’Univers of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique of France (CNRS), and the University of Hawaii. This work is based in part on observations obtained with MegaPrime/MegaCam, a joint project of CFHT and CEA/DAPNIA and in part on data products produced at TERAPIX and the Canadian Astronomy Data Centre as part of the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope Legacy Survey, a collaborative project of NRC and CNRS. This paper includes data gathered with the 6.5 m Magellan Telescopes located at Las Campanas Observatory, Chile.

© ESO, 2012

1. Introduction

Observing high-z galaxies within the first billion years of the Universe is one of the main frontiers in extragalactic astronomy. Since the discovery, less than a decade ago, of the first astrophysical object at a redshift above 6, a Lyα emitter at redshift 6.56 (Hu et al. 2002), spectacular progress has been made in assembling large samples of high-redshift objects. The two main techniques for finding high-redshift galaxies is to look either for strong absorption breaks in the Lyα forest in broad band photometry (Lyman break galaxies – LBGs) or for a photometric excess in narrow band (NB) filters due to the Lyα line (Lyα emitters – LAEs). In the latter case, the NB filters are usually selected to coincide with regions of low OH emission of the night sky, leading to discrete redshift values. SuprimeCam on the Subaru Telescope has revolutionized the field by enabling large samples of LAEs to be furnished at z = 5.7 and z = 6.5 (Ouchi et al. 2010; Hu et al. 2010, and references therein). The largest samples of LBGs have been recently assembled (Bouwens et al. 2011) from HST observations after the successful installation of the Wide Field Camera3 (WFC3) in May 2009, but LBGs can also be found from the ground with 8–10 m telescopes equipped with efficient near infrared (NIR) cameras (Castellano et al. 2010). Quasars at high-redshift are also found using the Lyman break technique in multi-colour datasets over very wide fields. Most of the quasars at z > 6 have been discovered in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (Fan et al. 2006) and from a targeted programme at CFHT (Willott et al. 2010). Finally, a few gamma ray bursts (GRBs) have been discovered at very high redshift (see e.g. Tanvir et al. 2009, for an example of a GRB at redshift 8.2), nicely complementing the other methods by probing the faint end of the luminosity function.

Combined with observations of the cosmic microwave background (CMB), the recent discovery of large samples of objects at high redshift allows astronomers to build a comprehensive picture of the Universe during the reionization epoch when it was 500 Myr to 1 Gyr old. Polarization measurements of the CMB from WMAP (Larson et al. 2011) show a large optical depth due to Thompson scattering of electrons in the early Universe, suggesting that the reionization started at z ~ 10.5 ± 1.2. Conversely, the strong increase of the optical depth in the Lyα forest of high-redshift quasars (Becker et al. 2001; Fan et al. 2006) above ~8500 Å is a likely indicator that reionization was mostly complete at a redshift of about 6. How and at what pace the reionization process has taken place in the [6–10] redshift range is more difficult to establish from observations, and is still a matter of debate. A compilation of the most recent results and constraints on the neutral-hydrogen fraction of the Universe between redshifts 5 and 11 from various probes is shown in Fig. 23 of Ouchi et al. (2010).

It has been proposed for a long time to use the Lyα transmission by the intergalactic medium (IGM) as a probe of its ionization state during the reionization epoch (see e.g. Santos 2004), hence the strong emphasis recently put on Lyα emission of LBGs and LAEs as more and more of these objects become available. Follow-up observations of high-z LBGs at z > 6 is now underway to detect the Lyα line in emission in spectroscopy. Stark et al. (2011) measure an increasing fraction of LBGs with strong Lyα emission from z ~ 3 to z ~ 6, and conjecture that Lyα emission should remain strong at higher redshifts unless the neutral-hydrogen fraction of the IGM suddently increases. Conversely, Fontana et al. (2010) report a low fraction of Lyα emitters in a sample of z > 6.5 LBGs. These are preliminary results based on still modest spectroscopic samples, and it is expected that ongoing and new observations will clarify the situation in a near future.

Another observational method of probing the Lyα IGM transmission is to study the evolution of the LAE luminosity function (LF) with redshift. Ouchi et al. (2010) and Kashikawa et al. (2006, 2011) infer from their observations that the evolution of the Lyα LAE LF between z = 5.7 and z = 6.5 can be attributed to a reduction of the IGM Lyα transmission of the order of 20%, which can in turn be attributed to a neutral-hydrogen fraction xHI of the order of 20% at z = 6.5 (see e.g. Ouchi et al. 2010). Various models are elaborated to reproduce this claim, which has generated considerable interest (see e.g. Kobayashi et al. 2010; Dayal et al. 2011; Laursen et al. 2011; Dijkstra & Wyithe 2010). However, the universality of the z = 6.5 LF from Kashikawa et al. (2006) and Ouchi et al. (2010) has recently been questioned. Hu et al. (2010) report significantly different LF parameters from the observations and analysis of a spectroscopically confirmed sample of NB selected LAEs. Similarly, Nakamura et al. (2011) report significantly lower number counts that they tentatively attribute to cosmic variance. Differences in the selection criteria and in extrapolations of the spectroscopic samples to photometric samples might partly explain the discrepancies between the various Lyα LAE LFs available in the literature: Kashikawa et al. (2011) have carried out extended spectroscopic confirmation of their earlier photometric sample, resulting in luminosity functions closer to the ones of Hu et al. (2010). Cassata et al. (2011) report the results from a pure spectroscopic sample of (mostly) serendipitous Lyα emitters found in deep spectroscopic samples with VIMOS at the VLT ; this sample is consistent with a constant LAE luminosity function from z ~ 2 to z ~ 6.6 as reported in the literature before the recent results from Hu et al. (2010).

|

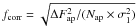

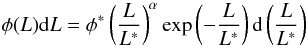

Fig. 1 Images of the CFHTLS-D4 (left), GOODS-South (centre), and Bullet Cluster (right) fields as in the final NB1060 image stacks. The inner and outer black contours on the Bullet Cluster image represent the regions where the gravitational amplification is respectively ≥ 2.5 (Δm ≤ −1) and ≥ 1.2 (Δm ≤ −0.2) for a source at redshift z = 7.7. |

The current situation at z ≳ 6 is therefore unclear, with somewhat contradictory observational results. This hampers the validation of the reionization models and of our understanding of this key epoch of the Universe. The discrepancy limits how well we can understand reionisation during this key epoch of the Universe. New data at z ~ 6 will help in resolving the current contention between observational results, while data at higher redshifts can bring new constraints at still poorly explored redshifts. In view of the strong interest in studying Lyα emission at high redshifts, searching LAEs at z > 7 is underway from various groups (Hibon et al. 2010; Tilvi et al. 2010; Nilsson et al. 2007). Finding z ~ 7 objects is not only interesting for probing the reionization epoch, but also for assessing the physical properties of these objects, which in turn allow constraining how and when they formed. Due to the extreme faintness of these very high-redshift objects, deriving their properties can only be done statistically over large samples (Bouwens et al. 2011) or on individual objects that are gravitationally amplified. For instance, Richard et al. (2011) infer a redshift of formation of 18 ± 4 for a gravitationally amplified object at z = 6.027.

This paper presents new results on the Lyα LAE LF at z = 7.7, from observations carried out at the VLT with the HAWK-I instrument. This paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2 we describe the observations and the data reduction in Sect. 3. In Sect. 4 we describe our selection procedure of the z = 7.7 LAE candidates. In Sect. 5 we present the constraints that we infer from our results on the z = 7.7 Lyα LAE LF, before discussing our results in Sect. 6.

We use AB magnitudes throughout this paper. We assume a flat ΛCDM model with ΩM = 0.30 and H0 = 70 km s-1 Mpc-1.

2. Observations

This work is primarily based on extremely deep NIR imaging data obtained with HAWK-I at the

VLT, using an NB filter at 1.06 μm (hereafter referred to as

NB1060). Thanks to its wide field of view

(7 5 ×

7

5 ×

7 5), excellent

throughput and image quality, HAWK-I is ideally suited to searching for faint NIR objects

such as very high-redshift galaxies. The main data set was obtained through a dedicated ESO

large programme between September 2008 and April 2010. In addition, we include in our

analysis HAWK-I science verification NB data taken in 2007. We also make use of various

optical and NIR broad band data, publicly available and/or from our own large programme.

5), excellent

throughput and image quality, HAWK-I is ideally suited to searching for faint NIR objects

such as very high-redshift galaxies. The main data set was obtained through a dedicated ESO

large programme between September 2008 and April 2010. In addition, we include in our

analysis HAWK-I science verification NB data taken in 2007. We also make use of various

optical and NIR broad band data, publicly available and/or from our own large programme.

2.1. Fields

In preparing the proposal, we carefully balanced the relative merits of blank fields and cluster fields. While gravitational amplification of background sources by foreground massive galaxy clusters allows us to probe luminosities that are intrinsically fainter than in the field, this is at the expense of areal coverage due to space distortion. The relative merits of blank and cluster fields depend on the shape of the luminosity function (LF) of the objects that are being searched, and on the properties of the observations such as field of view, integation time and overheads (Maizy et al. 2010; Richard et al. 2008). From the Lyα LAE LF at z = 6.5 that was available at the time of proposal preparation, we computed that either type of fields should yield approximately the same number of targets, while probing different (unlensed) luminosity ranges. We also analysed the balance between wide-shallow and narrow-deep survey strategies. For a total time of about 100 h (in the NB filter only), it was deemed that observing four fields in total would be optimal in terms of high-z LAE yield, while mitigating the effects of cosmic variance. Operational constraints, such as the distribution of the fields in right ascension, were additionally taken into account when selecting the fields. Our selected fields were Abell 1689 (13h11m30s, –01°20′35′′, J2000) and 1E0657-56 (Bullet Cluster) (06h58m29s, –55°57′16′′, J2000) for the cluster fields, the northern half of the GOODS-S field (03h32m29s, –27°44′42′′, J2000) and a subarea of the one square degree CFHTLS-D4 field (22h16m38s, –17°35′41′′, J2000) for the two blank fields.

For Abell 1689, although an extensively studied field, it proved hard to assemble a

consistent multiwavelength dataset covering the full

7 5 ×

7

5 ×

7 5 HAWK-I field

of view. This field is therefore not included in the present analysis and it will be

analysed separetely. The Bullet Cluster is a massive merging cluster that allowed the

first direct empirical proof of the existence of dark matter by the combination of strong

and weak-lensing analyses (Clowe et al. 2006; Bradač et al. 2006). Both clusters have well-constrained

mass models and provide a lens magnification of at least a factor of 1.2 over 50% of the

HAWK-I field of view (see Fig. 1). The GOODS-S and

CFHTLS-D4 field were chosen for the wealth of multiwavelength data, in particular deep

optical data, publicly available. For the CFHTLS-D4 field, we chose the location of the

HAWK-I observations where NIR data were available1

(Bielby et al., in prep.), and paying attention to avoiding the brightest stars present in

this field. Figure 1 shows the finding charts

corresponding to our observations inside the CFHTLS-D4, GOODS-S and Bullet Cluster fields.

5 HAWK-I field

of view. This field is therefore not included in the present analysis and it will be

analysed separetely. The Bullet Cluster is a massive merging cluster that allowed the

first direct empirical proof of the existence of dark matter by the combination of strong

and weak-lensing analyses (Clowe et al. 2006; Bradač et al. 2006). Both clusters have well-constrained

mass models and provide a lens magnification of at least a factor of 1.2 over 50% of the

HAWK-I field of view (see Fig. 1). The GOODS-S and

CFHTLS-D4 field were chosen for the wealth of multiwavelength data, in particular deep

optical data, publicly available. For the CFHTLS-D4 field, we chose the location of the

HAWK-I observations where NIR data were available1

(Bielby et al., in prep.), and paying attention to avoiding the brightest stars present in

this field. Figure 1 shows the finding charts

corresponding to our observations inside the CFHTLS-D4, GOODS-S and Bullet Cluster fields.

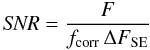

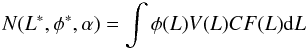

Table 1 summarizes the various observations made as part of our large programme on each of the three fields considered in the present analysis. Figure 2 shows the overall transmission curves of the HAWK-I broad band and NB filters corresponding to these observations. Table 2 summarizes the main ancillary broad band data used in this work. Our large programme data consists of more than 110 h of on-sky integration time, of which ~80 h are NB1060 data.

HAWK-I narrow band and broad band observations from our large programme

Ancillary public and private data used in this paper.

2.2. The HAWK-I NB1060 data

HAWK-I is a 7 5 ×

7

5 ×

7 5 NIR (0.97–2.31

μm) imager installed on the ESO VLT UT4. It is equipped with four 2048

× 2048 pixels Hawaii-2RG detectors, separated by 15′′ wide gaps. The pixel

scale is 0

5 NIR (0.97–2.31

μm) imager installed on the ESO VLT UT4. It is equipped with four 2048

× 2048 pixels Hawaii-2RG detectors, separated by 15′′ wide gaps. The pixel

scale is 0 1065. The

NB1060 filter has a central wavelength of 1062 nm, a full width at half

maximum (FWHM) of Δλ ~ 100 Å, and is designed to match a

region of low OH emission from the night sky. The filter width samples

Lyα emission in the redshift range z = [7.70–7.78]. A

detector integration time of 300 s is used for all the NB1060 images,

ensuring background limited performance. Random telescope offsets within a box of

20′′ for the blank fields and 25′′ for the cluster fields is used

for dithering. For each field, the NB1060 data are acquired over two

epochs separated by one year, allowing us to discard transient objects that could be

detected in a one-epoch stack, and not in the other.

1065. The

NB1060 filter has a central wavelength of 1062 nm, a full width at half

maximum (FWHM) of Δλ ~ 100 Å, and is designed to match a

region of low OH emission from the night sky. The filter width samples

Lyα emission in the redshift range z = [7.70–7.78]. A

detector integration time of 300 s is used for all the NB1060 images,

ensuring background limited performance. Random telescope offsets within a box of

20′′ for the blank fields and 25′′ for the cluster fields is used

for dithering. For each field, the NB1060 data are acquired over two

epochs separated by one year, allowing us to discard transient objects that could be

detected in a one-epoch stack, and not in the other.

The instrument had a thermal leak at the beginning of the first semester, which approximately doubled the total background in the NB1060 filter. After a technical intervention on the instrument after a few months of operations, the background returned to its nominal value, and only the observations of the CFHTLS-D4 field were affected. We were granted compensatory time that allowed us to recover the expected limiting magnitude but at the expense of unbalanced limiting magnitudes (by ~0.5 mag) for the first and second epoch observations. For the two other fields the limiting magnitudes between the two epoch observations are within ~0.15 mag.

In total, after image selection discarding images with poor image quality or too high background, the final stacks used in this analysis total integration times in the NB1060 filter of 26.7 h for the CFHTLS-D4 field, 31.9 h for GOODS-S (including science verification data) and 24.8 h for the Bullet Cluster (see Table 1).

|

Fig. 2 Transmission curves of the HAWK-I broad band and narrow band filters corresponding to the observations made as part of our large programme. The inset shows the profile of the NB1060 filter. |

2.3. Other imaging data

In addition to the NB1060 data, we performed dedicated broad band HAWK-I observations within our large programme to complement, on a case-by-case basis, the broad band data that were available elsewhere (see Table 1).

For the CFHTLS-D4 field, we had access to the very deep CFHTLS optical data and to the moderately deep NIR WIRDS data, but not as deep as our NB1060 data. We therefore took additional J and Ks data to improve the detection limit in these bands. For the Bullet Cluster, in the absence of well-established datasets in the optical and NIR bands, particularly over the full HAWK-I field of view, we devoted a significant fraction of the time on this field to get additional data in the Y, J, and Ks bands. We note that the HAWK-I Y filter bandpass includes, at its very red edge, the NB1060 filter bandpass. For this field we therefore secured a coherent and self-consistent dataset. We also used IMACS BVR images of the field obtained at the Magellan telescope (Clowe et al. 2006). For the GOODS-S field, we devoted a few hours of observations in the J band filter to reach a limiting magnitude fainter than that achieved with the public ISAAC images. We also used a very deep Y-band image of this field from a separate HAWK-I large programme (181.A-0717) led by one of us.

3. Data reduction

All reduced image stacks and ancillary data products (e.g. weight maps, etc.) from our large programme are currently available upon request and will be made public through the ESO archive, as part of the Phase 3 process2. We detail in this section the data reduction procedures that have been used to generate these high-level data products.

3.1. Overview

We use a mix of IRAF3 and AstrOmatic4 routines for the data reduction, allowing us to control the reduction process step by step. All single quadrant frames from the HAWK-I mosaic array are reduced similarly and independently until the very final steps. After a first pass at the sky subtraction, all images are characterized in terms of PSF and photometric quality, allowing us to identify and remove low-quality images that would degrade the final products. Depending on the field, between 3% and 13% of the NB1060 images are discarded, mostly when the image quality is worse than 1′′. This is the case for a fair fraction of the GOODS-S science verification images, for some of our large programme images that have been executed but not validated by the service observers, and, more rarely, for some fully validated images. A multi-pass sky subtraction is then performed, improving the quality of the masking of the objects at each pass. Images are then scaled to account for photometric variations and registered to a common reference frame. The final stacks are produced by averaging all images with a rejection algorithm using kappa-sigma clipping. The NB1060 photometric calibration is performed on unsaturated bright stars by interpolating their optical and 2MASS photometric data, following the approach described in Hibon et al. (2010). Finally, the final four stacks for each quadrant are aligned onto a common astrometric reference.

3.2. Data processing

-

1.

Pre-processing. Dark frames and twilight sky flats arecombined into master calibration frames on a nightly basis. Thereare typically eight dark frames and about 30 twilight sky flatfieldframes per night. No attempt is made to correct for the detector’snon-linearity, which, according to the HAWK-I users manual, isbelow the 1% level at 75% of the detector saturation level. Thiscould affect the accuracy of the photometric calibrationperformed on bright stars, and this is accounted for in thefollowing.

-

2.

Background subtraction. The most delicate step in the reduction of NIR data is the sky subtraction. With dithered images, the classical way of estimating the sky at any particular pixel is by building a running sky frame for each science frame. This running sky frame is usually computed as the median of Nsky frames around the central science frame to which it is subtracted. Some care is required, however, for this step to be optimally performed. First, the sky background varies, even in the NB1060 filter where the sky consists of a mixture of faint OH lines, sky continuum, and possibly faint thermal background leaking through the wings of the filter at wavelengths close to the detector cutoff. In addition, the background patterns have structures at low spatial frequencies that are changing with time, with the strongest changes occurring when the telescope crosses meridian. This is attributed to the rotation of the telescope pupil with time, with maximum velocity when passing the meridian. Therefore, the images used to generate a sky frame are carefully selected so as to have similar sky background patterns and to be close in time (within fewer than 15 days). The images thus selected are further zeroed to their median levels and normalized to their pixel to pixel standard deviation (with rejection of outliers). For each pixel, the median of its values in each running list of Nsky frames is computed, with kappa-sigma clipping for rejecting outliers. In this step, objects are masked (meaning that the values of the pixels where objects are detected are not included in the median determination) to avoid biasing the estimation of the sky toward high values. The masking process is initiated on individual sky-subtracted frames (where only the brightest objects are detected) and then repeated several times on combined stacks as described in step # 4.

-

3.

Bad pixels removal. Once the initial sky subtraction is performed on each science frame, bad pixel maps are generated on a nightly basis. Here again, we use the fact that with dithered data an object moves across the detector while bad pixels do not. Individual pixel values exceeding ±4σ of the local standard deviation over more than 70% of the frames in a given night are flagged as bad pixels and replaced by a linear interpolation of the surrounding pixel values along image lines.

-

4.

Object masking for sky subtraction. After the initial sky subtraction step and bad-pixel removal, the images are registered using a first-order astrometric solution and median-stacked with rejection of outliers. A mask is then generated from all objects detected in this image, together with detector regions of poor cosmetics. This mask is then used to reprocess the sky frames as described in step #2, after which a new image stack is produced. Steps #2 to #4 are typically repeated three to five times until the background around the objects in the final stack is flat. This iterative procedure improves the quality of the sky subtraction, which otherwise results in overestimated sky levels noticeable as dark regions around the bright objects and in larger photometric errors. As in step #2, the final sky frames are subtracted to the central science frames after zeroing to their median values and scaling to their standard deviations. Faint low-frequency sky subtraction residuals may still remain at this stage, which are removed with a bi-cubic-spline interpolation of a meshed background frame generated by SExtractor4 (Bertin & Arnouts 1996).

-

5.

Correction of photometric variations. Frame-to-frame scaling factors are derived from the number counts measured on bright and unsaturated stars detected in each individual sky-subtracted frame. These scaling factors account for variations of the atmosphere transparency and/or of the airmass. Between two to ten stars per quadrant frame are typically used and the fluxes derived from the SExtractor MAG_AUTO measurements. For all three fields, the variations of these frame-to-frame scaling factors are below 10% peak-to-peak, with a star-to-star variation within each frame of about 1.5%.

-

6.

Image registration. A relative astrometric solution is computed for each sky-subtracted frame using Scamp4 and a fourth-order polynomial fit of bright star positions across the detector plane. All the resulting images are then resampled to a common reference frame with Swarp (Bertin et al. 2002) using a LANCZOS4 interpolation kernel and a pixel scale of 0

1065.

The interpolation introduces correlated noise between pixels, and this is accounted

for when computing the signal-to-noise ratio of the object as discussed in

Sect. 3.3.2. The accuracy of the image

registration is well within one pixel for the whole data set.

1065.

The interpolation introduces correlated noise between pixels, and this is accounted

for when computing the signal-to-noise ratio of the object as discussed in

Sect. 3.3.2. The accuracy of the image

registration is well within one pixel for the whole data set. -

7.

Final stacks and weight maps. The final stacks for each quadrant are finally produced by averaging with 4σ rejection the individual science frames processed as described. In this process, a map identifying the rejected pixels and a sigma map are produced. In the latter, sigma (σ) is the standard deviation of the N input pixel values, excluding the rejected ones, entering into the stacks. The weight maps are then derived by computing N/σ2.

-

8.

Absolute photometric calibration. The broad band J and Ks data taken as part of our main programme are photometrically matched to existing photometric catalogues and images of the fields in these filters. We carefully select stars in our HAWK-I images for the photometric match. For the CFHTLS-D4 field, the stellar samples consist of 67 and 58 stars in the J and Ks bands. The zeropoints of the HAWK-I images are adjusted to match the photometry of these samples to the photometry of the same stars in the WIRDS data (see Sect. 2.1). This process leaves residuals between 0.03 and 0.05 magnitude rms in the J and Ks bands, respectively. The corresponding magnitudes are found to be in very good agreement with the photometry of the 19 2MASS stars present in the field, which is no surprise considering that the WIRDS data were calibrated against 2MASS. We check that there are no systematic offsets in the colours of our stellar samples compared to the colours determined from the stellar library of Pickles (1998) and from a variety of stellar spectra models at various temperatures and metallicites (Marigo et al. 2008, and http://stev.oapd.inaf.it/cgi-bin/cmd). For the GOODS-S field, we use the publicly available ISAAC J/H/Ks catalogue (Retzlaff et al. 2010) to compute the zeropoint of our HAWK-I J-band image. For the Bullet Cluster field, the J-band and Ks-band images are calibrated from the 2MASS catalogue, leaving residual errors of 0.05 mag rms in both bands. For the calibration of the NB1060 data, because photometric standards in narrow band filters do not exist, we perform the calibration directly on the image stacks, following the approach detailed in Hibon et al. (2010). It consists in interpolating the NB1060 stellar photometry from the optical and NIR broad band data. This is justified by the large number of photometric datapoints available in at least two of our fields and by the absence of features at 1.06 μm in the infrared spectra of stars of spectral types earlier than M5 – the coldest stars in our samples as determined by fitting their spectral energy distribution with the stellar models mentioned above. In practice the procedure consists in performing an ad hoc cubic spline fitting, for each star, of their magnitudes in all available bands. The magnitudes in the NB1060 band are derived from this fit. The procedure is adjusted according to the broad band data available in each field. We use exactly the same approach for calibrating the Y image in the case of the Bullet Cluster. For the CFHTLS-D4 field we use the u∗, g′, r′, i′, z′ optical data from the T0006 CFHTLS release and the NIR J, H, and Ks WIRDS data mentioned above. The selection of stars that are neither too bright nor too faint in any of the available images leaves a sample of 23 objects. The residual error on the determination of the zeropoint from this sample is 0.05 mag rms after rejection of outliers. For the GOODS-S field, the optical F435W, F606W, F775W, and F850LP magnitudes are taken from the merged HST/ACS catalogue (version r2.0z) available on the GOODS website. In this field, there are 44 suitable stars, and the process leaves a residual error of 0.06 mag rms in determining the NB1060 zeropoint. For the Bullet Cluster we use a slightly modified procedure to calibrate the Y and NB1060 images. This is because of the lack of optical data for the entire field of view covered by HAWK-I, preventing us from performing a robust interpolation based on a large number of stars between the two wavelength ranges. Instead, we empirically determine the NB1060 zeropoints by matching the J vs. J − NB1060 (resp. Ks vs. NB1060 − Ks) colour-magnitude diagrams of the stars present in this field to the same diagrams produced on the GOODS-S and CFHTLS-D4 fields after calibration. The same procedure is used to calibrate the Y-band image by comparing it to the colours of the stars in the GOODS-S field for which Y band data are available. All the procedures described above are conducted quadrant by quadrant, with a further iteration on the full four quadrant images. In total, considering the consistency between the many checks that are performed, and despite the various methods used, we estimate that the final accuracy of the photometric calibration is of the order of 0.1 magnitude rms.

-

9.

Absolute astrometric registration and final image stitching. The last step in our reduction process consists in stitching and registering the four detector images to the reference images of each field. The final astrometric solution is computed by Scamp4 with a fourth-order polynomial fit of the star positions. The CFHTLS-D4 stacks are aligned to the archival CFHTLS images. The GOODS-S stacks are aligned to the optical HST/ACS images, and the Bullet Cluster stacks are aligned to the 2MASS catalogue in the absence of astrometrically calibrated data across the entire area. The final astrometric residuals are below the 0

05 rms

level across the entire field of view for all images. Finally, the resampling and

final image stitching are performed using Swarp (Bertin et al. 2002). In addition, Swarp propagates the astrometric

solution to the weight maps and uses a weighted mean to compute pixel values in the

small overlap between quadrants due to the dithering pattern.

05 rms

level across the entire field of view for all images. Finally, the resampling and

final image stitching are performed using Swarp (Bertin et al. 2002). In addition, Swarp propagates the astrometric

solution to the weight maps and uses a weighted mean to compute pixel values in the

small overlap between quadrants due to the dithering pattern.

3.3. Final image properties

We now discuss the global properties of the final images: image quality (FWHM), noise, and detection limits. For consistency, the same procedure is applied to all the images used in this work, including archival data. The FWHM and the detection limits are listed in Table 1.

3.3.1. Image quality

The image quality is determined from a high signal-to-noise ratio point spread function

(PSF) generated by stacking unsaturated and isolated stellar images (range of 20–30) in

each field. After normalization, the stellar images are centred and median-stacked with

a 4σ outlier rejection. The rejection reduces the contribution from

faint neighbouring objects in the wings of the PSF but does not affect its profile. The

resulting NB1060 images are slightly elongated, for reasons that are

unknown to us, with a measured ellipticity from about 0.05 to 0.1 along a direction

≤10° away from the N-S axis. The FWHM values are derived

from a 2D-Gaussian fit to the median profile. The three NB1060 final

images have exquisite image qualities ranging from

0 53 to

0

53 to

0 58 (see

Table 1).

58 (see

Table 1).

3.3.2. Photometric errors and correlated noise

Image resampling introduced by the distortion correction, shifting, stitching, and

registration processes introduces correlation in the noise of the images. This leads in

turn to underestimating the photometric errors when considering the pixel-to-pixel noise

properties, see e.g. Grazian et al. (2006),

Appendix A, or Casertano et al. (2000). To measure

and account for this well known effect, we carefully analyse the noise properties of the

images over apertures of varying sizes and derive correction factors that we can then

apply to the photometric data measured by SExtractor. Indeed, SExtractor derives the

photometric error for each object it finds by computing the local pixel-to-pixel noise

fluctuation in the vicinity of the object (in the faint-object, background-limited

regime). The SExtractor photometric errors are therefore affected by the correlation of

the noise. For each image, we select a thousand positions corresponding to source-free

background regions determined from the final SExtractor segmentation (object mask)

image. For each position, we measure the integrated flux in circular apertures of

diameters ranging from Nap = 1 to 25 pixels

(0 1065 to

2

1065 to

2 663). For a

given aperture size, the variance of these fluxes,

663). For a

given aperture size, the variance of these fluxes,

, differs, because

of the correlated noise, from the variance

, differs, because

of the correlated noise, from the variance  of the

errors computed from the pixel-to-pixel variance

of the

errors computed from the pixel-to-pixel variance  and the

number of pixels Nap in the aperture. The square root of the

ratio of these two quantities

and the

number of pixels Nap in the aperture. The square root of the

ratio of these two quantities  gives the noise-correction factor that can be used to correct the photometric errors

measured by SExtractor. The ratio fcorr clearly depends on

the aperture size: for apertures smaller than the correlation length of the noise, which

is related to the size of the resampling interpolation kernels,

fcorr ~ 1, whereas for large apertures

gives the noise-correction factor that can be used to correct the photometric errors

measured by SExtractor. The ratio fcorr clearly depends on

the aperture size: for apertures smaller than the correlation length of the noise, which

is related to the size of the resampling interpolation kernels,

fcorr ~ 1, whereas for large apertures

, ranging

from 1.11 for a three-pixel diameter aperture to 1.67 for a 25 pixel diameter aperture.

The procedure is repeated ten times for each field, and all three fields give similar

and consistent measurements.

, ranging

from 1.11 for a three-pixel diameter aperture to 1.67 for a 25 pixel diameter aperture.

The procedure is repeated ten times for each field, and all three fields give similar

and consistent measurements.

This analysis finally allows us to assign signal-to-noise ratios (SNR)

to the objects detected by SExtractor, in the sky background limited regime, using

(1)where

ΔFSE is the photometric error measured by SExtractor. The

relation between SNR and the magnitude error Δm is

finally given by

(1)where

ΔFSE is the photometric error measured by SExtractor. The

relation between SNR and the magnitude error Δm is

finally given by  (2)

(2)

3.3.3. Aperture corrections and optimal apertures

We measured curves of growth on unsaturated stars for all image stacks used in this

work, using apertures between 1 and 150 pixels (0 1065 to

16′′) in diameter. Less than 1% of the flux resides in the wings of the PSF

beyond radii of 7′′, and we therefore safely use the 16′′aperture

correction to estimate the total flux of unresolved or moderately resolved objects. From

the curves of growth of both flux and noise, we derived the optimal diameter that

maximizes the signal-to-noise ratio for point-like objects. In practice, for all of our

NB1060 image stacks, a diameter of

1065 to

16′′) in diameter. Less than 1% of the flux resides in the wings of the PSF

beyond radii of 7′′, and we therefore safely use the 16′′aperture

correction to estimate the total flux of unresolved or moderately resolved objects. From

the curves of growth of both flux and noise, we derived the optimal diameter that

maximizes the signal-to-noise ratio for point-like objects. In practice, for all of our

NB1060 image stacks, a diameter of

(6 pixels) is used. The

corresponding aperture corrections δmap for

the three NB1060 final images are

δmap = 0.90 ± 0.04 mag,

δmap = 0.82 ± 0.03 mag,

δmap = 0.85 ± 0.04 mag for the GOODS-S,

CFHTLS-D4, and Bullet Cluster fields, respectively. The corresponding noise correcting

factors are fcorr = 1.22, 1.14, and 1.14 for the GOODS-S,

CFHTLS-D4, and Bullet Cluster fields, respectively.

(6 pixels) is used. The

corresponding aperture corrections δmap for

the three NB1060 final images are

δmap = 0.90 ± 0.04 mag,

δmap = 0.82 ± 0.03 mag,

δmap = 0.85 ± 0.04 mag for the GOODS-S,

CFHTLS-D4, and Bullet Cluster fields, respectively. The corresponding noise correcting

factors are fcorr = 1.22, 1.14, and 1.14 for the GOODS-S,

CFHTLS-D4, and Bullet Cluster fields, respectively.

3.3.4. Detection limits

Finally, from the two parameters defined above, fcorr and

δmap, one can define the

1σ limiting magnitude

m1σ for point-like objects:

(3)where

fcorr, ΔFSE and

δmap correspond to apertures of

0

(3)where

fcorr, ΔFSE and

δmap correspond to apertures of

0 64 in

diameter. This leads to a 3σNB1060 point source

detection limit of m3σ = 26.65, 26.65, and

26.50 for the GOODS-S, CFHTLS-D4, and Bullet Cluster, respectively, as reported in

Table 1.

64 in

diameter. This leads to a 3σNB1060 point source

detection limit of m3σ = 26.65, 26.65, and

26.50 for the GOODS-S, CFHTLS-D4, and Bullet Cluster, respectively, as reported in

Table 1.

4. Candidate selection

4.1. Detection completeness

|

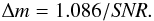

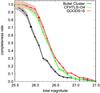

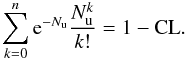

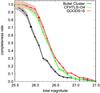

Fig. 3 Completeness levels of the NB1060 images for the three observed fields. The coloured areas correspond to the Poissonian errors on the number counts in the corresponding magnitude bin. The triangles indicate the 5σ magnitude limits. |

We use SExtractor (Bertin & Arnouts 1996)

version 2.8.6 for source detection and photometric measurements. We fit the PSF median

profile discussed in Sect. 3.3.1 with a sum of three

2-dimensional Gaussians from which we derive the filter (9 × 9 pixels or

) used by SExtractor for

spatial filtering during the detection process. We then use this point-source model to

generate mock sources injected into the image to estimate the image detection

completeness. We inject 500 mock sources per Δm = 0.1 mag bins in regions

of the images randomly distributed and free of objects. We perform a number of tests to

determine the optimum SExtractor detection parameters that maximize the number of detected

objects while minimizing the number of false alarms. Considering the absence of candidate

LAEs in our images, we choose to push to the faintest possible limits. False alarms are

investigated by running SExtractor on the negative images and are discussed in Sect. 4.3. We determine that an adequate set of SExtractor

parameters, for the purpose of our analysis, is to trigger a detection on one pixel

(DETECT_MINAREA) after spatial filtering at 0.7σ above the local

background (DETECT_THRESH). With these detection parameters, the average signal-to-noise

ratio of sources in the 50% completeness magnitude bin is of about 4, and a SNR

of 5 corresponds to a completeness rate of 70 to 80%. Figure 3 shows the completeness rates achieved in the three NB1060

images.

) used by SExtractor for

spatial filtering during the detection process. We then use this point-source model to

generate mock sources injected into the image to estimate the image detection

completeness. We inject 500 mock sources per Δm = 0.1 mag bins in regions

of the images randomly distributed and free of objects. We perform a number of tests to

determine the optimum SExtractor detection parameters that maximize the number of detected

objects while minimizing the number of false alarms. Considering the absence of candidate

LAEs in our images, we choose to push to the faintest possible limits. False alarms are

investigated by running SExtractor on the negative images and are discussed in Sect. 4.3. We determine that an adequate set of SExtractor

parameters, for the purpose of our analysis, is to trigger a detection on one pixel

(DETECT_MINAREA) after spatial filtering at 0.7σ above the local

background (DETECT_THRESH). With these detection parameters, the average signal-to-noise

ratio of sources in the 50% completeness magnitude bin is of about 4, and a SNR

of 5 corresponds to a completeness rate of 70 to 80%. Figure 3 shows the completeness rates achieved in the three NB1060

images.

4.2. Selection criteria

We do not expect z ~ 7.7 LAEs to be detected in any of the filters blueward of the Lyα line redshifted to 1.06 μm. First, negligible amounts of radiation are expected to escape the galaxy and to be transmitted by the IGM below the Lyman limit, which is redshifted to ~790 nm. In addition, all the radiation between the Lyα and Lyγ lines at z = 7.7 is entirely redshifted beyond the Gunn-Peterson trough at ~850 nm observed in the spectra of high-redshift quasars (Fan et al. 2006). Only in the blue part – the most depressed part – of the Lyα forest, just above the Lyman limit, can we therefore expect some flux from a z ~ 7.7 LAE to arrive on Earth, in the wavelength range [790–850] nm approximately. In practice, considering the limiting magnitudes of our optical and NB1060 images, an absorption of 2 mag or so will result in no detections in any of the optical bands.

For the purpose of the analysis described in this paper, we built a master catalogue of

all the NB1060 detected objects, measuring their magnitudes in each of

the optical and NIR broad band images by running SExtractor in double image mode. To do

so, we resample all images to the HAWK-I pixel scale

of 0 1065. We then

search objects in this master catalogue that are not detected in the optical images at an

initial SNR ≤ 3 level, reduced to SNR ≤ 2 after visual

inspection. In the case of the CFHTLS-D4 field, we request in addition that these objects

not be detected at a 2σ significance level in a

χ2 image of the field obtained by combining the

g′, r′, and

i′ images. In the case of the GOODS-S field, we use a

similar non-detection limit on a bviz

χ2 image obtained by combining the four broad band

HST/ACS images. Because the NB1060 bandpass is located within the

bandpass of the Y filter (at its red edge), the Lyα line

may be detected in the Y filter. To estimate the

Y − NB1060 colour as a function of redshift, we

generate simple synthetic models of LAE spectra, consisting of a narrow

Lyα line and a UV-continuum of energy distribution

fλ ∝ λβ.

We allow the UV slope β to vary from −3 to 0, and we set the flux

density below the Lyα line to zero. For objects with redshifts in the

interval [7.70−7.78] corresponding to the NB1060 filter, we find that

the Y − NB1060 colour is ~ 2.35 ± 0.35, with the

lowest values corresponding to situations where the Lyα line is

redshifted near the edges of the NB1060 filter transmission curve, and

therefore strongly attenuated. This corresponds to the case of high-redshift LBGs detected

through their continuum in the NB1060 filter. As we see in the next

section, the Y images (when available) are not deep enough, relative to

the NB1060 images, to measure such a colour on the faintest objects, but

they do allow us, conversely, to discard blue and moderately bright objects that pass the

other colour selection criteria. To secure the presence of an emission line in the

NB1060 filter, we further require a 1σ NB excess over

the flux measured in the J-band. From Eq. (6) in Hibon et al. (2010), NB1060 − J

≤ 0 corresponds to equivalent widths EWobs ≥ 50 Å or

EWrest ≥ 5.7 Å, assuming a flat continuum spectrum

(fν = const.). We note

that the NB1060 filter is placed approximately at the centre of the

bandpass covering the Y and J filters, allowing us to

further constrain the presence of an LAE from its colour between the NB1060

and Y+J bandpasses; however, in the absence of candidates from

the criteria used so far (see next section), this did not prove necessary to add to our

selection criteria. Finally, we restrict the analysis to sources having

SNR ≥ 5 in the NB1060 final images and

SNR ≥ 2 in partial or intermediate image stacks corresponding to

different observing epochs. In summary, our detection criteria are

1065. We then

search objects in this master catalogue that are not detected in the optical images at an

initial SNR ≤ 3 level, reduced to SNR ≤ 2 after visual

inspection. In the case of the CFHTLS-D4 field, we request in addition that these objects

not be detected at a 2σ significance level in a

χ2 image of the field obtained by combining the

g′, r′, and

i′ images. In the case of the GOODS-S field, we use a

similar non-detection limit on a bviz

χ2 image obtained by combining the four broad band

HST/ACS images. Because the NB1060 bandpass is located within the

bandpass of the Y filter (at its red edge), the Lyα line

may be detected in the Y filter. To estimate the

Y − NB1060 colour as a function of redshift, we

generate simple synthetic models of LAE spectra, consisting of a narrow

Lyα line and a UV-continuum of energy distribution

fλ ∝ λβ.

We allow the UV slope β to vary from −3 to 0, and we set the flux

density below the Lyα line to zero. For objects with redshifts in the

interval [7.70−7.78] corresponding to the NB1060 filter, we find that

the Y − NB1060 colour is ~ 2.35 ± 0.35, with the

lowest values corresponding to situations where the Lyα line is

redshifted near the edges of the NB1060 filter transmission curve, and

therefore strongly attenuated. This corresponds to the case of high-redshift LBGs detected

through their continuum in the NB1060 filter. As we see in the next

section, the Y images (when available) are not deep enough, relative to

the NB1060 images, to measure such a colour on the faintest objects, but

they do allow us, conversely, to discard blue and moderately bright objects that pass the

other colour selection criteria. To secure the presence of an emission line in the

NB1060 filter, we further require a 1σ NB excess over

the flux measured in the J-band. From Eq. (6) in Hibon et al. (2010), NB1060 − J

≤ 0 corresponds to equivalent widths EWobs ≥ 50 Å or

EWrest ≥ 5.7 Å, assuming a flat continuum spectrum

(fν = const.). We note

that the NB1060 filter is placed approximately at the centre of the

bandpass covering the Y and J filters, allowing us to

further constrain the presence of an LAE from its colour between the NB1060

and Y+J bandpasses; however, in the absence of candidates from

the criteria used so far (see next section), this did not prove necessary to add to our

selection criteria. Finally, we restrict the analysis to sources having

SNR ≥ 5 in the NB1060 final images and

SNR ≥ 2 in partial or intermediate image stacks corresponding to

different observing epochs. In summary, our detection criteria are

-

1.

NB1060 ≥ 5σ ∧ NB1060epoch1 ≥ 2σ ∧ NB1060epoch2 ≥ 2σ;

-

2.

no detection above the 2σ level in any of the visible broad band filters;

-

3.

2 ≤ Y − NB1060 ≤ 2.7 (when Y band data are available);

-

4.

NB1060 − J ≤ 0 with 1σ significance.

We finally note that astrophysical sources such as transients, extremely red objects (EROS), high-EW low-z line emitters or T-dwarfs can potentially satisfy the optical non-detection criteria defined here. Relatively deep NIR Y and/or J and/or Ks band data are therefore required for consolidating the selection (e.g. criteria #3 and #4) and reducing contamination from astrophysical sources. The J and Ks band data in particular are useful to identify T-dwarfs and EROs, even if the latter are often detected in deep optical images. In the absence of LAE candidate in our data, we are clearly not affected by contamination, thanks to the coherent datasets that we use. We refer the interested reader to Sect. 3.3 of Hibon et al. (2010) for a somewhat more detailed analysis of contamination effects in a similar z = 7.7 LAE search, in particular by Hα, [OIII], and [OII] line emitters.

4.3. Selection field by field

The 5σ detection limit in the NB1060 filter corresponds to magnitudes m5σ = 25.9 to m5σ = 26.1 depending on field (see Table 1), and to a completeness level of 70 to 80% (see Fig. 3). The corresponding colour criteria used for the selection of candidates differ among the three fields depending on the depth of the optical images available in each of them.

CFHTLS-D4. The selection criterion #2 in the previous section

corresponds to the following colour criteria:

![\begin{equation} \begin{array}{lcl} \textit{u*}_{2\sigma}-\textit{NB1060} & \ge & 1.7,\\[1mm] \textit{g\arcmin}_{2\sigma}-\textit{NB1060} & \ge & 2.5,\\[1mm] \textit{r\arcmin}_{2\sigma}-\textit{NB1060} & \ge & 2.3,\\[1mm] \textit{i\arcmin}_{2\sigma}-\textit{NB1060} & \ge & 1.8,\\[1mm] \textit{z\arcmin}_{2\sigma}-\textit{NB1060} & \ge & 0.9.\\ \end{array} \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2012/02/aa17312-11/aa17312-11-eq118.png) (4)There

are ~6500 NB1060 objects detected in this field. The application of

criteria #1 and #2 of Sect. 4.2 yields 20 objects.

Ten are visually identified as instrumental artefacts caused by electronic crosstalk (see

Sect. 4.4). Seven of the remaining objects are

detected and relatively bright in the J band and therefore rejected after

application of criterion #4. We note in passing that the brightest of these objects has

NB1060 = 24.15, J = 23.85 and

J − H2σ ≤ −0.85 and is

very likely a T-dwarf.

(4)There

are ~6500 NB1060 objects detected in this field. The application of

criteria #1 and #2 of Sect. 4.2 yields 20 objects.

Ten are visually identified as instrumental artefacts caused by electronic crosstalk (see

Sect. 4.4). Seven of the remaining objects are

detected and relatively bright in the J band and therefore rejected after

application of criterion #4. We note in passing that the brightest of these objects has

NB1060 = 24.15, J = 23.85 and

J − H2σ ≤ −0.85 and is

very likely a T-dwarf.

Amongst the three remaining objects, one is located near the edges of the image and appears sharper than the PSF. One is located in the wings (4′′) of a bright extended galaxy, therefore of suspicious photometry and therefore unusable. Finally, the last one appears to be a variable, extended object, with ≥ 1 magnitude difference between the first- and second-epoch observations. All three objects are therefore discarded.

To allow for possibly slightly extended LAE candidates and for consistency checks, we

carry out a second selection using larger apertures

( ), and applying the

appropriate aperture correction. Criteria #1 and #2 yielded 14 detections, out of which

nine are in common with the previous sample of 20 objects. Amongst the remaining five new

detections, one is an obvious artefact near a bright star, two are detected in the

J-band and are rejected due to the low significance of their NB excess.

The two last ones are low significance detections in the NB1060 image

(SNR ≤ 5.5) and both show extended and dubious morphologies.

), and applying the

appropriate aperture correction. Criteria #1 and #2 yielded 14 detections, out of which

nine are in common with the previous sample of 20 objects. Amongst the remaining five new

detections, one is an obvious artefact near a bright star, two are detected in the

J-band and are rejected due to the low significance of their NB excess.

The two last ones are low significance detections in the NB1060 image

(SNR ≤ 5.5) and both show extended and dubious morphologies.

Checking the robustness of the rejections further, we investigate the false alarms on the

negative image using the two aperture diameters mentioned above. After removing the

well-determined crosstalk features, which have a negative component, we are left with

eight objects using the  aperture and 2 using the

aperture and 2 using the

aperture, all of them at

the limit of our signal-to-noise ratio selection. These genuine noise artefacts have very

similar morphologies to those of the positive detections that were rejected on the science

image: either very sharp or extended and irregular with bright non-contiguous pixels. This

legitimizes our somewhat ad hoc, but pragmatic earlier selection based on the morphology

of the faintest positive candidates, and we therefore conclude that there are no

z = 7.7 LAE candidate in the CFHTLS-D4 field.

aperture, all of them at

the limit of our signal-to-noise ratio selection. These genuine noise artefacts have very

similar morphologies to those of the positive detections that were rejected on the science

image: either very sharp or extended and irregular with bright non-contiguous pixels. This

legitimizes our somewhat ad hoc, but pragmatic earlier selection based on the morphology

of the faintest positive candidates, and we therefore conclude that there are no

z = 7.7 LAE candidate in the CFHTLS-D4 field.

GOODS-S. Here the selection criterion #2 corresponds to the following

colour criteria: ![\begin{equation} \begin{array}{lcl} \textit{F435W}_{2\sigma}-\textit{NB1060} & \ge & 2.3,\\[1mm] \textit{F606W}_{2\sigma}-\textit{NB1060} & \ge & 2.5,\\[1mm] \textit{F775W}_{2\sigma}-\textit{NB1060} & \ge & 1.9,\\[1mm] \textit{F850LP}_{2\sigma}-\textit{NB1060} & \ge & 1.6.\\ \end{array} \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2012/02/aa17312-11/aa17312-11-eq125.png) (5)There

are ~5100 NB1060 detected objects. The application of criteria #1 and

#2 yields 16 objects, of which 12 are visually identified as instrumental artefacts caused

by electronic crosstalk. Amongst the four remaining objects, one is due to a mismatch on a

blended object, and two are marginally detected objects at the edges of the image. The

last object is detected in the Y-band but does not satisfy criterion #3

above; interestingly, it is identified with reference G2_1408 as a z ~ 7

object in Castellano et al. (2010, and references

therein). This object has been followed up in spectroscopy (Fontana et al. 2010), yielding a tentative detection of the

Lyα line at a redshift z = 6.97. This object therefore

appears to be an LBG, caught by its strong UV continuum emission detected in the

NB1060 filter.

(5)There

are ~5100 NB1060 detected objects. The application of criteria #1 and

#2 yields 16 objects, of which 12 are visually identified as instrumental artefacts caused

by electronic crosstalk. Amongst the four remaining objects, one is due to a mismatch on a

blended object, and two are marginally detected objects at the edges of the image. The

last object is detected in the Y-band but does not satisfy criterion #3

above; interestingly, it is identified with reference G2_1408 as a z ~ 7

object in Castellano et al. (2010, and references

therein). This object has been followed up in spectroscopy (Fontana et al. 2010), yielding a tentative detection of the

Lyα line at a redshift z = 6.97. This object therefore

appears to be an LBG, caught by its strong UV continuum emission detected in the

NB1060 filter.

Similar to what was done on the CFHTLS-D4 field, we then performed a second selection

using  apertures. This yields two

new detections (beyond the obvious electronic artefacts): one is detected in the

Y-band and does not pass criterion #3, and is also marginally

noticeable in the optical bands. The other one has a dubious morphology and is close to a

bright object, and is therefore rejected. Finally, we carried out the false alarm analysis

on the negative image, and we detect a handful of events with dubious morphologies,

leading to the same conclusions as for the CFHTLS-D4 field.

apertures. This yields two

new detections (beyond the obvious electronic artefacts): one is detected in the

Y-band and does not pass criterion #3, and is also marginally

noticeable in the optical bands. The other one has a dubious morphology and is close to a

bright object, and is therefore rejected. Finally, we carried out the false alarm analysis

on the negative image, and we detect a handful of events with dubious morphologies,

leading to the same conclusions as for the CFHTLS-D4 field.

Bullet Cluster. The dataset for the Bullet Cluster field is somewhat different than for the other fields. As explained in Sect. 2.3, we accomodated a consistent set of HAWK-I data in the Y, NB1060, J and Ks bands within our large programme. In addition, we used HST/ACS images of the inner part of the field, as well as moderately deep IMACS images from the Magellan telescope (Clowe et al. 2006). There are ~7000 NB1060 objects satisfying criterion #1, the vast majority of which are detected in the Y filter and do not satisfy criterion #3. Only 127 objects are not detected in the Y image at 3σ, but because Y3σ − NB10605σ = 0.4, it is impossible to conclude whether they satisfy criterion #3 or not. After visual inspection and rejection of electronical ghosts and obvious artefacts, all but one object show a clear counterpart in either one of the HST/ACS images or in the IMACS images. This object shows no NB excess (NB1060 − J = 0.55 ± 0.25), and together with a marginal detection in the Y-band (SNR ~ 2.4, Y = 26.40 ± 0.45) and a non-detection in Ks (Ks ≤ 25.3, 3σ upper limit), we conjecture that this object is probably a T-dwarf. Finally, a selection based on larger apertures as for the two other fields yields no new candidates. We therefore conclude, again, that there are no z = 7.7 LAE candidates in the Bullet Cluster field.

4.4. Instrumental artefacts

Instrumental artefacts are a potentially important source of contamination. As explained in Sect. 4.3, candidates are found that are rejected as instrumental artefacts. We describe here some of the instrumental artefact sources that are observed in the HAWK-I data.

-

1.

Electronic crosstalk. The HAWK-I data suffer from inter-channel crosstalk from the readout electronics. This results indonut-shaped artefacts at regularly spaced intervals along de-tector lines where bright stars are present. These artefacts werelargely attenuated after a technical intervention in the instrumentthat took place in May 2009. The crosstalk pattern follows thedithering pattern and is therefore present on the final stackedimages. The crosstalk artefacts are easy to recognize from theirshapes and fixed distances from bright stars along detector rows.Because they do not have counterparts in optical images, theseartefacts are selected as candidates in our analysis, but are easilydealt with a posteriori. No attempt was made to remove theseartefacts during data processing.

-

2.

Optical ghosts. Reflections inside the instrument generate typical out-of-focus and decentred pupil images around bright stars. The surface brightness of these haloes was measured to be 10-4 of the peak intensity in the PSF profiles. Only focussed optical ghosts can be mistaken as candidates, and no such artefacts are observed on the HAWK-I images.

-

3.

Persistence. Persistence from previously observed bright stars is at a fixed detector position. The persistence features therefore do not follow the dithering pattern and are rejected when combining the images with sigma clipping in the final stacks. Considering the large number of frames used in the stacks (more than 200 frames), persistence effects are unlikely to leave residuals that can be mistaken as candidates.

-

4.

Radioactive events. One of the HAWK-I arrays (chip #2, Id: ESO-Hawaii2RG-chip78) suffers from a strong radioactive event rate, coming from the detector substrate (Finger et al. 2008). These radioactive events generate showers of variable intensity (typically thousands of electrons) and extent (typically a few tens of pixels on a side). Some events can be as bright as a few hundred thousand electrons and extend up to 400 pixels in one direction. Because of the long detector integration times (DIT) used for the NB1060 images (300 s), there are a few tens of such events in a single frame. This results in poor background subtraction and moderately high-frequency residuals (a few tens of pixels) in individual sky-subtracted frames. Although the global noise properties are not significantly different in this quadrant than in the others, the overall cosmetics are somewhat poorer. As a consequence, most of the low signal-to-noise ratio detections and with dubious morphologies reported in Sect. 4.3 appear to be in this quadrant and are therefore rejected as artefacts after visual inspection.

-

5.

Noise. As explained earlier, we chose a low detection threshold in order to push to the faintest detection limits, triggering a handful of low signal-to-noise ratio false alarms, particularly on the highly radioactive quadrant. We settle on a detection threshold that allows us to handle these false alarms.

5. Constraints on the z = 7.7 Lyα luminosity function

5.1. Comoving volume

The effective field of view in the transverse dimension of the NB1060 stacks is computed as a function of the detection limit for each field from the background noise maps generated by SExtractor, and accounting for the correlation of the noise as described in Sect. 3.3.2. The sensitivity is reduced at the edges of each quadrant image thanks to the dithering process and in regions close to bright objects. All objects are masked, reducing the total effective area by ~10% for the blank fields, and ~25% for the Bullet Cluster due to the large number of bright galaxy cluster members. For this field, we further use a map of the gravitational amplification and space distortion from a detailed model of the cluster (Richard et al., in prep.) to compute the effective, unlensed, comoving area corresponding to the image (see Willis et al. 2008, for a similar example). In the direction of the line of sight, we use the filter transmission curve to determine the effective width. We then approximate the NB1060 filter with a rectangular filter of width equal to this effective width. The effects of the filter transmission curve on LAE detection and comoving volumes are detailed in e.g. Willis & Courbin (2005) and Hu et al. (2010). Considering our null results, these effects will not affect our conclusions. We also assume that the filter transmission curve does not vary significantly over the instrument’s field of view, an assumption motivated by the relative uniformity of the sky background over the instrument’s field of view. We finally assume that the observed Lyα emission lines are significantly narrower than the filter width, as is the case for high-z LAEs, and we therefore ignore the effect of the line width on the line flux measured through the NB1060 filter. The effective width of the NB1060 (Δλeff ~ 100 Å) defines the [7.70−7.78] redshift interval probed by our observations.

Converting magnitudes to line luminosities requires assumptions on the equivalent width (EW) of the Lyα line. Distributions of observed Lyα lines in high-z LAEs vary from a few tens of Angstroms to lower limits of a few hundred Angstroms (see e.g. Taniguchi et al. 2005; Ouchi et al. 2010). The Taniguchi et al. (2005) distribution of Lyα line EWs is consistent with a conversion factor of 70%, as used in Hibon et al. (2010), when assuming that the EW lower limits are the real values. Conversely, Kobayashi et al. (2010) predict a distribution of Lyα EWs clearly peaked toward high values, hence favouring conversion factors closer to 100%. In the following, we therefore use these two values (70% and 100%) when converting NB1060 magnitudes to line luminosities.

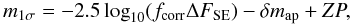

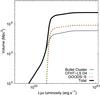

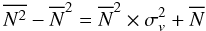

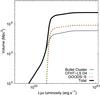

In total, the comoving volume sampled by our images is 5.9 × 103 Mpc3 for the Bullet Cluster and 9 × 103 Mpc3 for each of the two blank fields, corresponding to a grand total of ~2.4 × 104 Mpc3 for the three fields. The volume-luminosity relation is shown in Fig. 4, and the effect of the gravitational amplification for the Bullet Cluster is clearly visible, where the gravitational amplification enables probing fainter luminosities, however over increasingly smaller volumes.

|

Fig. 4 The comoving volume V(L) sampled by the NB1060 images as a function of Lyα luminosity. The two dashed curves correspond to the two blank fields (green – CFHTLS-D4; red – GOODS-S). The thin black curve corresponds to the Bullet Cluster. The thick black curve is the total comoving volume corresponding to the three fields. The Lyα luminosity corresponds to a 5σNB1060 limiting magnitude, assuming a 70% average conversion factor between the Lyα luminosities and NB1060 magnitudes (see text). |

5.2. Cosmic variance and Poisson noise

We do not detect any LAE candidates down to a NB1060 5σ

limiting magnitude of ~25.9 to ~26.1. To constrain the luminosity function of

z = 7.7 Lyα emitters and compare our results with

others, we make use of the Schechter formalism (Schechter

1976):  (6)where

L∗ is the characteristic luminosity defining the LF high

luminosity cutoff, φ∗ a volume density normalization factor,

and α the faint-end slope characterizing how steeply the LF increases at

low luminosities. Limited samples and large errors lead to degneracy between these three

LF parameters. Pending more observational data and more accurate determinations of the

high-z LAE LF parameters, most of the authors in the literature have

settled on a canonical faint end slope value of α = −1.5. Our

observations probe luminosities similar, or slightly fainter, than those observed by other

groups; therefore, we can compare our results to others, and to this aim we similarly

adopt, unless stated otherwise, a faint end slope of α = −1.5.

(6)where

L∗ is the characteristic luminosity defining the LF high

luminosity cutoff, φ∗ a volume density normalization factor,

and α the faint-end slope characterizing how steeply the LF increases at

low luminosities. Limited samples and large errors lead to degneracy between these three

LF parameters. Pending more observational data and more accurate determinations of the

high-z LAE LF parameters, most of the authors in the literature have

settled on a canonical faint end slope value of α = −1.5. Our

observations probe luminosities similar, or slightly fainter, than those observed by other

groups; therefore, we can compare our results to others, and to this aim we similarly

adopt, unless stated otherwise, a faint end slope of α = −1.5.

Denoting V(L) the comoving volume probed by our

observations as a function of the luminosity L, as described in

Sect. 5.1 and shown in Fig. 4, the total number of objects

N(L∗,φ∗,α)

is given by  (7)where

CF(L) is the completeness function (see Sect. 4.1). The conversion of the completeness function as a

function of magnitude as shown in Fig. 3 to

CF(L) takes into account the conversion factor of 70%

and 100% mentioned above, and in the case of the Bullet Cluster further takes the

amplification map of the cluster into account.

(7)where

CF(L) is the completeness function (see Sect. 4.1). The conversion of the completeness function as a

function of magnitude as shown in Fig. 3 to

CF(L) takes into account the conversion factor of 70%

and 100% mentioned above, and in the case of the Bullet Cluster further takes the

amplification map of the cluster into account.

From a Poisson distribution, one can easily compute single-sided confidence levels (CL)

for the upper limits of the expected number of events Nu that

correspond to a measured number of events n, as (Gehrels 1986):  (8)In our situation

of zero detection (n = 0), the 84.13, 97.72, 99.87, and 99.99

percentiles5 confidence levels correspond to upper

limits of the mean number of events Nu of 1.84, 3.78, 6.61,

and 10.36, respectively. The situation Nu ≤ 1 corresponds to a

63% confidence level. Therefore, with zero detection and assuming pure Poisson statistics,

one can exclude, at a given confidence level CL, the luminosity function parameters that

would yield an expected number of objects Nu with our survey

parameters.

(8)In our situation

of zero detection (n = 0), the 84.13, 97.72, 99.87, and 99.99

percentiles5 confidence levels correspond to upper

limits of the mean number of events Nu of 1.84, 3.78, 6.61,

and 10.36, respectively. The situation Nu ≤ 1 corresponds to a

63% confidence level. Therefore, with zero detection and assuming pure Poisson statistics,

one can exclude, at a given confidence level CL, the luminosity function parameters that

would yield an expected number of objects Nu with our survey

parameters.

However, considering the somewhat limited area covered by our observations, we need to consider the effects of cosmic variance in our statistical analysis. Somerville et al. (2004) are among the first authors to derive quantitative estimates of the effects of cosmic variance from cold dark matter (CDM) models and observations of the two-point correlation functions of galaxy populations in the GOODS survey data. Trenti & Stiavelli (2008) expand on this work and propose a cosmic variance model, based on N-body simulations and halo occupation distribution models, and applied to a variety of high-z galaxy populations. We use below the on-line version of this model to estimate the effects of cosmic variance on our observations.

Various prescriptions have been proposed for the distribution function of galaxy number counts affected by cosmic variance, see Yang & Saslaw (2011) for a recent discussion and analysis of the galaxy counts-in-cells distribution functions in the SDSS data. Although not physically motivated, the negative binomial distribution (NBD) fits the SDSS data well at both low and high number counts and provides a convenient description for the distribution function of galaxies with positive number counts and overdispersion relative to a Poisson distribution. To prevent technical problems with the use of normal or lognormal distributions (e.g. truncation to positive numbers), we chose to adopt the NBD as an ad hoc representation of the probability density function of low galaxy number counts. The NBD can be conveniently expressed as a Poisson random variable whose mean population parameter is itself random and distributed as a Gamma distribution of variance equal to the relative cosmic variance.

By definition of the cosmic variance, the variance

of the number of

galaxies of mean number

of the number of

galaxies of mean number  is in excess

of the Poisson variance

is in excess

of the Poisson variance  and is given

by

and is given

by  (9)where

(9)where

is the

relative cosmic variance. With the NBD prescription, one can derive the confidence level

CL corresponding to no detections in our observations, for a known

is the

relative cosmic variance. With the NBD prescription, one can derive the confidence level

CL corresponding to no detections in our observations, for a known