| Issue |

A&A

Volume 516, June-July 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A63 | |

| Number of page(s) | 26 | |

| Section | Cosmology (including clusters of galaxies) | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200913577 | |

| Published online | 29 June 2010 | |

Evidence of the accelerated expansion of the Universe from weak lensing tomography with COSMOS![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

T. Schrabback1,2 - J. Hartlap2 - B. Joachimi2 - M. Kilbinger3,4 - P. Simon5 - K. Benabed3 - M. Bradac6,7 - T. Eifler2,8 - T. Erben2 - C. D. Fassnacht6 - F. William High9 - S. Hilbert10,2 - H. Hildebrandt1 - H. Hoekstra1 - K. Kuijken1 - P. J. Marshall7,11 - Y. Mellier3 - E. Morganson11 - P. Schneider2 - E. Semboloni2,1 - L. Van Waerbeke12 - M. Velander1

1 - Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, Niels Bohrweg 2, 2333 CA Leiden, The Netherlands

2 -

Argelander-Institut für Astronomie, Universität Bonn,

Auf dem Hügel 71, 53121 Bonn, Germany

3 -

Institut d'Astrophysique de Paris, CNRS UMR 7095 & UPMC, 98bis boulevard Arago, 75014 Paris, France

4 -

Shanghai Key Lab for Astrophysics, Shanghai Normal University, Shanghai 200234, PR China

5 -

The Scottish Universities Physics Alliance

(SUPA), Institute for Astronomy, School of Physics,

University of Edinburgh, Royal Observatory, Blackford Hill, Edinburgh EH9 3HJ, UK

6 -

Physics Dept., University of California, Davis, 1

Shields Ave., Davis, CA 95616, USA

7 -

Physics department, University of California, Santa Barbara,

CA 93601, USA

8 -

Center for Cosmology and AstroParticle Physics, The Ohio State University,

Columbus, OH 43210, USA

9 -

Department of Physics, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA

10 -

Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics, Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 1, 85741 Garching, Germany

11 -

KIPAC, PO Box 20450, MS29, Stanford, CA 94309, USA

12 - University of British Columbia, Department of Physics and

Astronomy, 6224 Agricultural Road, Vancouver, B.C. V6T 1Z1, Canada

Received 31 October 2009 / Accepted 8 March 2010

Abstract

We present a comprehensive analysis of weak gravitational lensing by large-scale structure in the

Hubble Space Telescope Cosmic Evolution Survey (COSMOS), in which

we combine

space-based galaxy shape measurements

with ground-based photometric redshifts to study the redshift dependence of

the lensing signal

and constrain cosmological

parameters.

After applying our weak lensing-optimized data reduction, principal-component interpolation for the spatially, and

temporally varying ACS point-spread function, and improved modelling of charge-transfer inefficiency,

we measured a lensing signal that is consistent with pure gravitational modes and no significant shape systematics.

We carefully estimated

the statistical uncertainty

from simulated COSMOS-like fields

obtained from ray-tracing through the Millennium Simulation,

including the full non-Gaussian sampling variance.

We tested our lensing pipeline on simulated space-based data,

recalibrated non-linear power spectrum corrections using the ray-tracing analysis,

employed photometric redshift information to reduce potential contamination by

intrinsic galaxy alignments, and marginalized over systematic uncertainties.

We find that the weak lensing signal scales with redshift as expected

from general relativity for a concordance

![]() CDM cosmology,

including the full cross-correlations between different redshift bins.

Assuming a flat

CDM cosmology,

including the full cross-correlations between different redshift bins.

Assuming a flat ![]() CDM cosmology, we measure

CDM cosmology, we measure

![]() from lensing,

in perfect agreement with WMAP-5, yielding joint constraints

from lensing,

in perfect agreement with WMAP-5, yielding joint constraints

![]() ,

,

![]() (all 68.3% conf.).

Dropping the assumption of flatness

and using priors from the HST Key Project and Big-Bang nucleosynthesis only,

we find a negative deceleration parameter q0 at

94.3%

confidence from the

tomographic lensing analysis, providing independent evidence of the accelerated expansion of the Universe.

For a flat wCDM cosmology

and prior

(all 68.3% conf.).

Dropping the assumption of flatness

and using priors from the HST Key Project and Big-Bang nucleosynthesis only,

we find a negative deceleration parameter q0 at

94.3%

confidence from the

tomographic lensing analysis, providing independent evidence of the accelerated expansion of the Universe.

For a flat wCDM cosmology

and prior

![]() ,

we obtain

w<-0.41 (90% conf.).

Our dark energy constraints are still relatively weak solely due to the limited area of COSMOS.

However, they provide an important demonstration of the usefulness of tomographic weak

lensing measurements from space.

,

we obtain

w<-0.41 (90% conf.).

Our dark energy constraints are still relatively weak solely due to the limited area of COSMOS.

However, they provide an important demonstration of the usefulness of tomographic weak

lensing measurements from space.

Key words: cosmological parameters - dark matter - large-scale structure of Universe - gravitational lensing: weak

1 Introduction

During the past decade

strong evidence of an accelerated expansion of the Universe has been

found with

several independent cosmological probes

including type Ia supernovae (Kowalski et al. 2008; Hicken et al. 2009; Perlmutter et al. 1999; Riess et al. 1998,2007), cosmic microwave background (Spergel et al. 2003; de Bernardis et al. 2000; Komatsu et al. 2009), galaxy clusters (Mantz et al. 2009; Vikhlinin et al. 2009; Mantz et al. 2008; Allen et al. 2008),

baryon acoustic oscillations (Percival et al. 2009,2007; Eisenstein et al. 2005), integrated Sachs-Wolfe

effect (Granett et al. 2008; Giannantonio et al. 2008; Ho et al. 2008),

and strong gravitational lensing (Suyu et al. 2010).

Within the standard cosmological framework, this can be described with the ubiquitous presence of a

new constituent named dark energy, which counteracts the attractive force of gravity on the largest scales and contributes ![]() 70%

to the total energy budget today.

There have been various attempts to explain dark energy, ranging from

Einstein's cosmological constant, via a dynamic fluid named

quintessence, to a possible breakdown of general relativity (e.g. Albrecht et al. 2009; Huterer & Linder 2007),

all of which lead to profound implications for fundamental physics.

In order to make substantial progress and to be able to distinguish between the different scenarios,

several large dedicated surveys are currently being designed.

70%

to the total energy budget today.

There have been various attempts to explain dark energy, ranging from

Einstein's cosmological constant, via a dynamic fluid named

quintessence, to a possible breakdown of general relativity (e.g. Albrecht et al. 2009; Huterer & Linder 2007),

all of which lead to profound implications for fundamental physics.

In order to make substantial progress and to be able to distinguish between the different scenarios,

several large dedicated surveys are currently being designed.

One technique with particularly high promise for constraining dark energy (Albrecht et al. 2009,2006; Peacock et al. 2006) is weak gravitational lensing, which utilizes the subtle image distortions imposed onto the observed shapes of distant galaxies, while their light bundles pass through the gravitational potential of foreground structures (e.g. Bartelmann & Schneider 2001). The strength of the lensing effect depends on the total foreground mass distribution, independent of the relative contributions of luminous and dark matter. It therefore provides a unique tool to study the statistical properties of large-scale structure directly (for reviews see Hoekstra & Jain 2008; Schneider 2006; Munshi et al. 2008).

Since its first detections by Bacon et al. (2000), Kaiser et al. (2000), Van Waerbeke et al. (2000) and Wittman et al. (2000), substantial progress has been made with the measurement of this cosmological weak lensing effect, which is also called cosmic shear. Larger surveys have significantly reduced statistical uncertainties (e.g. Van Waerbeke et al. 2005; Jarvis et al. 2003; Massey et al. 2005; Hetterscheidt et al. 2007; Semboloni et al. 2006; Hoekstra et al. 2002; Fu et al. 2008; Hoekstra et al. 2006; Brown et al. 2003), while tests on simulated data have led to better understanding of PSF systematics (Massey et al. 2007a; Bridle et al. 2010; Heymans et al. 2006a, and references therein). Finally, because it is a geometric effect, gravitational lensing depends on the source redshift distribution, where most earlier measurements have had to rely on external redshift calibrations from the small Hubble Deep Fields. Here, the impact of sampling variance was demonstrated by Benjamin et al. (2007), who recalibrated earlier measurements using photometric redshifts from the much larger CFHTLS-Deep, significantly improving derived cosmological constraints.

Dark energy affects the distance-redshift relation and suppresses the time-dependent growth of structures. Because it is sensitive to both effects, weak lensing is a powerful probe of dark energy properties, also providing important tests for theories of modified gravity (e.g. Benabed & Bernardeau 2001; Schimd et al. 2007; Jain & Zhang 2008; Doré et al. 2007; Schmidt 2008; Benabed & van Waerbeke 2004). Yet, in order to significantly constrain these redshift-dependent effects, the shear signal must be measured as a function of source redshift, an analysis often called weak lensing tomography or 3D weak lensing (e.g. Jain & Taylor 2003; Hu & Jain 2004; Simon et al. 2004; Hu 2002; Takada & Jain 2004; Huterer 2002; Hu 1999; Heavens 2003; Bernstein & Jain 2004; Heavens et al. 2006; Taylor et al. 2007). Redshift information is additionally required to eliminate potential contamination of the lensing signal from intrinsic galaxy alignments (e.g. King & Schneider 2002; Heymans et al. 2006b; Joachimi & Schneider 2008; Hirata & Seljak 2004). In general, weak lensing studies have to rely on photometric redshifts (e.g. Hildebrandt et al. 2008; Ilbert et al. 2006; Benitez 2000), given that most of the studied galaxies are too faint for spectroscopic measurements.

So far, tomographic cosmological weak lensing techniques

have been

applied to

real data by Bacon et al. (2005), Semboloni et al. (2006), Kitching et al. (2007) and Massey et al. (2007c).

Dark energy constraints from previous

weak lensing surveys

were

limited by the lack of the required

individual photometric redshifts (Kilbinger et al. 2009a; Jarvis et al. 2006; Hoekstra et al. 2006; Semboloni et al. 2006)

or small survey area (Kitching et al. 2007).

The currently best data set for 3D weak lensing is given by the COSMOS

Survey (Scoville et al. 2007a), which is

the largest continuous area ever imaged with the Hubble Space Telescope (HST), comprising 1.64 deg2

of deep imaging with the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS).

Compared to ground-based measurements, the HST point-spread function

(PSF) yields substantially increased number densities of sufficiently

resolved galaxies and better control of systematics due to smaller PSF

corrections.

Although HST has been used for earlier cosmological weak lensing

analyses (e.g. Schrabback et al. 2007; Refregier et al. 2002; Rhodes et al. 2004; Miralles et al. 2005; Heymans et al. 2005),

these studies lack the area and deep photometric redshifts

that are available for COSMOS (Ilbert et al. 2009).

This combination of superb space-based imaging and ground-based

photometric redshifts makes COSMOS the perfect test case for 3D weak

lensing studies.

Massey et al. (2007c) conducted an earlier 3D weak lensing analysis of COSMOS, in

which they

correlated the shear signal between three redshift bins and constrained the matter density

![]() and power spectrum normalization

and power spectrum normalization ![]() .

In this paper we present a new analysis of the data, with several

differences compared to the earlier study: we employ a new,

exposure-based model for the spatially and temporally varying ACS PSF,

which

has been derived from dense stellar fields using a principal component

analysis (PCA). Our new parametric correction for the impact of charge

transfer inefficiency (CTI) on stellar images eliminates earlier PSF

modelling uncertainties caused by confusion of CTI- and PSF-induced

stellar ellipticity. Using the latest photometric redshift catalogue

of the field (Ilbert et al. 2009),

we split our galaxy sample into five individual redshift bins and

also estimate the redshift distribution for very faint galaxies

forming a sixth bin without individual photometric redshifts,

doubling the number of galaxies used in our cosmological analysis. We

study the redshift scaling of the shear signal between these six bins

in

detail, employ an accurate covariance matrix obtained from ray-tracing

through the Millennium Simulation, which we also use to recalibrate

non-linear power spectrum corrections, and marginalize over parameter

uncertainties.

In addition to

.

In this paper we present a new analysis of the data, with several

differences compared to the earlier study: we employ a new,

exposure-based model for the spatially and temporally varying ACS PSF,

which

has been derived from dense stellar fields using a principal component

analysis (PCA). Our new parametric correction for the impact of charge

transfer inefficiency (CTI) on stellar images eliminates earlier PSF

modelling uncertainties caused by confusion of CTI- and PSF-induced

stellar ellipticity. Using the latest photometric redshift catalogue

of the field (Ilbert et al. 2009),

we split our galaxy sample into five individual redshift bins and

also estimate the redshift distribution for very faint galaxies

forming a sixth bin without individual photometric redshifts,

doubling the number of galaxies used in our cosmological analysis. We

study the redshift scaling of the shear signal between these six bins

in

detail, employ an accurate covariance matrix obtained from ray-tracing

through the Millennium Simulation, which we also use to recalibrate

non-linear power spectrum corrections, and marginalize over parameter

uncertainties.

In addition to

![]() and

and ![]() ,

we also constrain the

dark energy equation of state parameter w for a flat wCDM cosmology, and

the vacuum energy density

,

we also constrain the

dark energy equation of state parameter w for a flat wCDM cosmology, and

the vacuum energy density

![]() for a general (non-flat)

for a general (non-flat)

![]() CDM cosmology, yielding constraints for the deceleration parameter q0.

CDM cosmology, yielding constraints for the deceleration parameter q0.

This paper is organized as follows. We summarize the most important information on the data and photometric redshift catalogue in Sect. 2, while further details on the ACS data reduction are given in Appendix A. Section 3 summarizes the weak lensing measurements including our new correction schemes for PSF and CTI, for which we provide details in Appendix B. We conduct various tests for shear-related systematics in Sect. 4. We then present the weak lensing tomography analysis in Sect. 5, and cosmological parameter estimation in Sect. 6. We discuss our findings and conclude in Sect. 7.

Throughout this paper all magnitudes are given in the AB system, where i814 denotes the SExtractor (Bertin & Arnouts 1996)

![]() magnitude measured from the ACS data (Sect. 2.1), while i+ is the MAG_AUTO

magnitude determined by Ilbert et al. (2009) from the Subaru data (Sect. 2.2.1).

In several tests we employ a reference WMAP-5-like (Dunkley et al. 2009) flat

magnitude measured from the ACS data (Sect. 2.1), while i+ is the MAG_AUTO

magnitude determined by Ilbert et al. (2009) from the Subaru data (Sect. 2.2.1).

In several tests we employ a reference WMAP-5-like (Dunkley et al. 2009) flat ![]() CDM cosmology characterized by

CDM cosmology characterized by

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

h=0.72,

,

h=0.72,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

where we use the transfer function by Eisenstein & Hu (1998) and non-linear power spectrum corrections according to Smith et al. (2003).

,

where we use the transfer function by Eisenstein & Hu (1998) and non-linear power spectrum corrections according to Smith et al. (2003).

2 Data

2.1 HST/ACS data

The COSMOS Survey (Scoville et al. 2007a) is the largest contiguous field observed with the Hubble Space Telescope, spanning

a total area of ![]()

![]() (1.64

(1.64

![]() ).

It comprises 579 ACS

tiles, each observed in F814W for 2028 s using four dithered

exposures.

The survey is centred at

).

It comprises 579 ACS

tiles, each observed in F814W for 2028 s using four dithered

exposures.

The survey is centred at

![]() ,

,

![]() (J2000.0), and data were taken between

October 2003 and November 2005.

(J2000.0), and data were taken between

October 2003 and November 2005.

We

have

reduced the ACS/WFC data starting from the flat-fielded

images.

We

apply updated bad pixel masks,

subtract the sky background,

and compute optimal weights as detailed in

Appendix A.

For the image registration, distortion correction, cosmic ray rejection, and stacking we use

MultiDrizzle![]() (Koekemoer et al. 2002),

applying the latest time-dependent distortion solution from Anderson (2007).

We iteratively align exposures within each tile by cross-correlating the

positions of compact sources and applying

residual shifts and rotations.

(Koekemoer et al. 2002),

applying the latest time-dependent distortion solution from Anderson (2007).

We iteratively align exposures within each tile by cross-correlating the

positions of compact sources and applying

residual shifts and rotations.

In tests with dense stellar fields we found that the default cosmic ray rejection parameters of MultiDrizzle can lead to false flagging of central stellar pixels as cosmic rays, especially if telescope breathing introduces significant PSF variations (see Sect. 3) between combined exposures. Thus, stars will be partially rejected in exposures with deviating PSF properties. On the contrary, galaxies will not be flagged due to their shallower light profiles, leading to different effective stacked PSFs for stars and galaxies. To avoid any influence on the lensing analysis, we create separate stacks for the shape measurement of galaxies and stars, where we use close to default cosmic ray rejection parameters for the former (driz_cr_snr=``4.0 3.0'', driz_cr_scale=``1.2 0.7'', see Koekemoer et al. 2002,2007), but less aggressive masking for the latter (driz_cr_snr=``5.0 3.0'', driz_cr_scale=``3.0 0.7''). As a result, the false masking of stars is substantially reduced. On the downside some actual cosmic rays lead to imperfectly corrected artifacts in the ``stellar'' stacks. This is not problematic given the very low fraction of affected stars, for which the artifacts only introduce additional noise in the shape measurement.

For the final image stacking we employ the LANCZOS3

interpolation kernel and a pixel scale of 0

![]() 05, which minimizes

noise correlations and aliasing without unnecessarily broadening the

PSF (for a detailed comparison to other kernels see Jee et al. 2007).

Based on our

input noise models (see Appendix A)

we

compute a correctly scaled rms image for the stack.

We match the stacked image WCS to the ground-based catalogue by Ilbert et al. (2009).

05, which minimizes

noise correlations and aliasing without unnecessarily broadening the

PSF (for a detailed comparison to other kernels see Jee et al. 2007).

Based on our

input noise models (see Appendix A)

we

compute a correctly scaled rms image for the stack.

We match the stacked image WCS to the ground-based catalogue by Ilbert et al. (2009).

We employ our rms noise model for object detection with SExtractor (Bertin & Arnouts 1996), where we require

a minimum of 8 adjacent pixels being at least ![]() above the background, employ deblending parameters

above the background, employ deblending parameters

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and measure

,

and measure

![]() magnitudes

i814, which we correct for a mean galactic extinction offset of 0.035 (Schlegel et al. 1998).

Objects near the field boundaries or containing noisy pixels, for which fewer than two good input exposures contribute,

are automatically excluded. We also create magnitude-scaled polygonal masks for saturated stars and their diffraction spikes.

Furthermore, we reject scattered light and large, potentially incorrectly deblended galaxies by running SExtractor with a low

magnitudes

i814, which we correct for a mean galactic extinction offset of 0.035 (Schlegel et al. 1998).

Objects near the field boundaries or containing noisy pixels, for which fewer than two good input exposures contribute,

are automatically excluded. We also create magnitude-scaled polygonal masks for saturated stars and their diffraction spikes.

Furthermore, we reject scattered light and large, potentially incorrectly deblended galaxies by running SExtractor with a low ![]() detection threshold for 3960 adjacent pixels,

where we further expand each object mask

by six pixels.

The combined masks for the stacks were visually inspected and adapted if necessary.

detection threshold for 3960 adjacent pixels,

where we further expand each object mask

by six pixels.

The combined masks for the stacks were visually inspected and adapted if necessary.

Our fully filtered mosaic shear catalogue contains a total of

446 934 galaxies with

i814<26.7, corresponding to 76 galaxies

![]() ,

where we exclude double detections

in overlapping tiles and reject the fainter component in the case of close galaxy pairs with separations

,

where we exclude double detections

in overlapping tiles and reject the fainter component in the case of close galaxy pairs with separations

![]() .

For details on the weak lensing galaxy selection criteria see Appendix B.6.

.

For details on the weak lensing galaxy selection criteria see Appendix B.6.

In addition to the stacked images, our fully time-dependent PSF analysis (see

Sect. 3, Appendix B.5)

makes use of individual exposures, for which we use the cosmic ray-cleansed

COR images before resampling,

provided by MultiDrizzle during the run with less aggressive cosmic ray masking.

These

are only used for the analysis

of

high signal-to-noise stars, which can be identified automatically in the half-light radius versus signal-to-noise space![]() .

Here we employ simplified field masks

only excluding the outer regions of a tile with poor cosmic ray masking.

.

Here we employ simplified field masks

only excluding the outer regions of a tile with poor cosmic ray masking.

2.2 Photometric redshifts

2.2.1 Individual photometric redshifts for i+ < 25 galaxies

We use

the public COSMOS-30 photometric redshift catalogue from Ilbert et al. (2009),

which covers the full ACS mosaic and is magnitude limited to i+<25 (Subaru

SExtractor MAG_AUTO

magnitude).

It is based on the 30 band photometric catalogue, which includes

imaging in 20 optical bands, as well as near-infrared and deep IRAC data (Capak et al. 2009, in preparation).

Ilbert et al. (2009) computed photometric redshifts using the Le Phare code

(S. Arnouts & O. Ilbert; also Ilbert et al. 2006),

reaching an excellent

accuracy of

![]() for i+ < 24

and z < 1.25. The near-infrared (NIR) and infrared coverage extends the capability for reliable photo-z estimation to higher redshifts, where the Balmer break moves out of the optical bands. Extended to

for i+ < 24

and z < 1.25. The near-infrared (NIR) and infrared coverage extends the capability for reliable photo-z estimation to higher redshifts, where the Balmer break moves out of the optical bands. Extended to ![]() ,

Ilbert et al. (2009)

find an accuracy of

,

Ilbert et al. (2009)

find an accuracy of

![]() at

at

![]() .

The comparison to spectroscopic redshifts from the zCOSMOS-deep sample (Lilly et al. 2007) with

.

The comparison to spectroscopic redshifts from the zCOSMOS-deep sample (Lilly et al. 2007) with

![]() indicates a 20% catastrophic outlier rate (defined as

indicates a 20% catastrophic outlier rate (defined as

![]() )

for galaxies at

)

for galaxies at

![]() .

In particular, for 7% of the high-redshift (

.

In particular, for 7% of the high-redshift (

![]() )

galaxies a low-redshift photo-z (

)

galaxies a low-redshift photo-z (

![]() )

was assigned.

This degeneracy is expected for faint (

)

was assigned.

This degeneracy is expected for faint (![]() )

high-redshift galaxies,

for which the Balmer break cannot be identified

if they are undetected in the NIR data

(limiting depth

)

high-redshift galaxies,

for which the Balmer break cannot be identified

if they are undetected in the NIR data

(limiting depth

![]() ,

,

![]() at

at ![]() ).

Due to the employed magnitude prior the contamination is expected to be

mostly uni-directional from high to low redshifts.

).

Due to the employed magnitude prior the contamination is expected to be

mostly uni-directional from high to low redshifts.

We tested this by comparing the COSMOS-30 catalogue

to photometric redshifts estimated by Hildebrandt et al. (2009) in the overlapping CFHTLS-D2 field using only optical u*griz bands and the BPZ photometric redshift code (Benitez 2000). Here we indeed find that 56%

of

the matched i+<25 galaxies with COSMOS-30 photo-zs in the range

![]() are identified at

are identified at

![]() in the D2 catalogue, if only a weak cut to reject

galaxies with double-peaked D2 photo-z PDFs (

in the D2 catalogue, if only a weak cut to reject

galaxies with double-peaked D2 photo-z PDFs (

![]() )

is applied

)

is applied![]() .

.

If not accounted for, such a contamination of a low-photo-z

sample with high-redshift galaxies would be particularly severe for

weak lensing tomography, given the strong dependence of the lensing

signal on redshift.

In Sect. 5 we will therefore split galaxies with assigned

![]() into sub-samples with expected low (i+<24) and high (i+>24) contamination,

where we only include the former in the cosmological analysis.

Matching our shear catalogue to the fully masked COSMOS-30 photo-z catalogue

yields a total of 194 976 unique matches.

into sub-samples with expected low (i+<24) and high (i+>24) contamination,

where we only include the former in the cosmological analysis.

Matching our shear catalogue to the fully masked COSMOS-30 photo-z catalogue

yields a total of 194 976 unique matches.

2.2.2 Estimating the redshift distribution for i+>25 galaxies

In order to include galaxies

without individual photo-zs in our analysis, we need to estimate their redshift distribution.

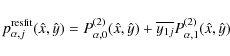

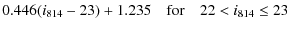

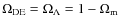

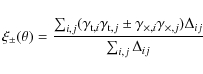

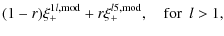

Figure 1 shows the mean photometric COSMOS-30 redshift for galaxies in our shear catalogue

as a function of i814.

In the whole magnitude range

23<i814<25

the data are very well described by the relation

For comparison we also plot points from the Hubble Deep Field-North (HDF-N, Fernández-Soto et al. 1999) and Hubble Ultra Deep Field (HUDF, Coe et al. 2006)

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13577f1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/08/aa13577-09/Timg86.png)

|

Figure 1:

Relation between the mean photometric redshift and i814

magnitude for COSMOS, HUDF, and HDF-N, where the error-bars indicate

the error of the mean assuming Gaussian scatter and neglecting sampling

variance.

The best fit (1) to the COSMOS data from

i814<25 is

shown as the bold line, whereas the thin lines indicate the

conservative |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Due to the non-linear dependence of the shear signal on redshift it is not only necessary to estimate the correct mean redshift

of the galaxies, but also their actual redshift distribution.

In weak lensing studies the redshift distribution is often parametrized as

![]() (e.g. Brainerd et al. 1996), which Schrabback et al. (2007) extended by fitting

(e.g. Brainerd et al. 1996), which Schrabback et al. (2007) extended by fitting

![]() in combination with a linear dependence of the median redshift on magnitude, leading to a magnitude-dependent z0.

Yet, it was noted that this fit was not fully capable to reproduce the

shape of the redshift distribution of the fitted galaxies. Given the

higher accuracy needed for the analysis of the larger COSMOS Survey we

use a modified parametrization

in combination with a linear dependence of the median redshift on magnitude, leading to a magnitude-dependent z0.

Yet, it was noted that this fit was not fully capable to reproduce the

shape of the redshift distribution of the fitted galaxies. Given the

higher accuracy needed for the analysis of the larger COSMOS Survey we

use a modified parametrization

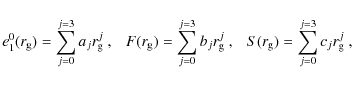

where z0=z0(i814), and

| z0 | = |

|

(3) |

| z0 | = | ![$\displaystyle \sum_{j=0}^{j=7} a_j [(i_{814}-23)/4]^j \quad \quad~ {\rm for}\quad 23<i_{814}<27$](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/08/aa13577-09/img93.png)

|

(4) |

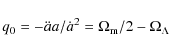

with (a0,...,a7) = (1.237, 1.691, -12.167, 43.591, -76.076, 72.567, -35.959, 7.289). The total redshift distribution of the survey is then simply given by the mean distribution

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.8cm,clip]{13577f2.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/08/aa13577-09/Timg95.png)

|

Figure 2: Redshift histogram for galaxies in our shear catalogue with COSMOS-30 photo-zs (dotted), split into four magnitude bins. The solid curves show the fit according to (1) and (2), which is capable to describe both the peak and high redshift tail. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

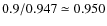

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=6.5cm,clip]{13577f3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/08/aa13577-09/Timg97.png)

|

Figure 3: Combined redshift histogram for the HDF-N and HUDF photo-zs, split into two magnitude bins. The solid curves show the prediction according to (1), (2) and the galaxy magnitude distribution. The good agreement for 25<i814<27 galaxies confirms the applicability of the model in this magnitude regime. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Our fitting scheme assumes that the COSMOS-30 photo-zs provide unbiased

estimates for the true galaxy redshifts. However, in

Sect. 2.2 we suspected that

![]() galaxies with assigned

z< 0.6

might contain a

significant contamination with high-redshift galaxies.

To assess the impact of this uncertainty, we derive the fits for (1) and (2)

using only galaxies with

23<i+ < 24, reducing the estimated mean redshift of

shear galaxies without COSMOS-30 photo-z by

galaxies with assigned

z< 0.6

might contain a

significant contamination with high-redshift galaxies.

To assess the impact of this uncertainty, we derive the fits for (1) and (2)

using only galaxies with

23<i+ < 24, reducing the estimated mean redshift of

shear galaxies without COSMOS-30 photo-z by ![]() .

As an alternative test, we assume that 20% of the

z< 0.6

galaxies with

24<i+ < 25 are truly at z=2, increasing the

estimated mean redshift by

.

As an alternative test, we assume that 20% of the

z< 0.6

galaxies with

24<i+ < 25 are truly at z=2, increasing the

estimated mean redshift by ![]() .

Compared to the fit uncertainty in (1)

(

.

Compared to the fit uncertainty in (1)

(![]()

![]() )

this constitutes the main source of error for our redshift

extrapolation.

In the cosmological parameter estimation (Sect. 6), we constrain this uncertainty and marginalize over it using a nuisance parameter,

which rescales the redshift distribution

within a conservatively chosen

)

this constitutes the main source of error for our redshift

extrapolation.

In the cosmological parameter estimation (Sect. 6), we constrain this uncertainty and marginalize over it using a nuisance parameter,

which rescales the redshift distribution

within a conservatively chosen ![]()

![]() interval.

Note that the

interval.

Note that the ![]() difference between the measured and

predicted mean redshift of the combined HDF-N and HUDF data in

Fig. 3 actually suggests a smaller uncertainty.

difference between the measured and

predicted mean redshift of the combined HDF-N and HUDF data in

Fig. 3 actually suggests a smaller uncertainty.

3 Weak lensing shape measurements

To measure an accurate lensing signal, we have to carefully correct for instrumental signatures. Even with the high-resolution space-based data at hand, we have to accurately account for both PSF blurring and ellipticity, which introduce spurious shape distortions. To do so, one requires both a good model for the PSF, and a method which accurately employs it to measure unbiased estimates for the (reduced) gravitational shear g from noisy galaxy images.

For the latter,

we use the KSB+

formalism (Luppino & Kaiser 1997; Kaiser et al. 1995; Hoekstra et al. 1998), see Erben et al. (2001), Schrabback et al. (2007) and Appendix B.1 for details on our implementation.

As found with simulations of ground-based weak lensing data, KSB+

can significantly

underestimate gravitational shear

(Massey et al. 2007a; Erben et al. 2001; Bacon et al. 2001; Heymans et al. 2006a), where

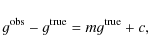

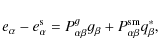

the calibration bias m and possible PSF anisotropy residuals c, defined via

depend on the details of the implementation. Massey et al. (2007a, STEP2) detected a shear measurement degradation for faint objects for our pipeline, which is not surprising given the fact that the KSB+ formalism does not account for noise. While Schrabback et al. (2007) simply corrected for the resulting mean calibration bias, the 3D weak lensing analysis performed here requires unbiased shape measurements not only on average, but also as function of redshift, and hence galaxy magnitude and size (see e.g. Kitching et al. 2008; Semboloni et al. 2009; Kitching et al. 2009). We therefore empirically account for this degradation with a power-law fit to the signal-to-noise dependence of the calibration bias

where S/N is computed with the galaxy size-dependent KSB weight function (Erben et al. 2001), and corrected for noise correlations as done in Hartlap et al. (2009). As S/N relates to the significance of the galaxy shape measurement, it provides a more direct correction for noise-related bias than fits as a function of magnitude or size. We have determined this correction using the STEP2 simulations of ground-based weak lensing data (Massey et al. 2007a). In order to test if it performs reliably for the ACS data, we have analysed a set of simulated ACS-like data (see Appendix B.2). In summary, we find that the remaining calibration bias is

Weak lensing analyses usually create PSF models from the observed images of

stars, which have to be interpolated for the position of each galaxy.

Typically, a high galactic latitude ACS field

contains only ![]() 10-20 stars with sufficient S/N,

which are too few for the spatial polynomial interpolation commonly

used in ground-based weak lensing studies.

In addition, a stable PSF model cannot be used,

given that substantial temporal PSF variations have been detected,

mostly caused by

focus changes resulting from orbital temperature variations (telescope

breathing), mid-term seasonal effects, and long-term shrinkage of the

optical telescope

assembly (OTA) (e.g. Anderson & King 2006; Schrabback et al. 2007; Rhodes et al. 2007; Lallo et al. 2006; Krist 2003).

To circumvent this problem, we have implemented a PSF correction scheme based on principal component analysis (PCA), as

first suggested by Jarvis & Jain (2004).

We have analysed 700 i814

exposures of dense stellar fields, interpolated the PSF variation in

each exposure with polynomials, and performed a PCA analysis of the

polynomial coefficient variation.

We find that

10-20 stars with sufficient S/N,

which are too few for the spatial polynomial interpolation commonly

used in ground-based weak lensing studies.

In addition, a stable PSF model cannot be used,

given that substantial temporal PSF variations have been detected,

mostly caused by

focus changes resulting from orbital temperature variations (telescope

breathing), mid-term seasonal effects, and long-term shrinkage of the

optical telescope

assembly (OTA) (e.g. Anderson & King 2006; Schrabback et al. 2007; Rhodes et al. 2007; Lallo et al. 2006; Krist 2003).

To circumvent this problem, we have implemented a PSF correction scheme based on principal component analysis (PCA), as

first suggested by Jarvis & Jain (2004).

We have analysed 700 i814

exposures of dense stellar fields, interpolated the PSF variation in

each exposure with polynomials, and performed a PCA analysis of the

polynomial coefficient variation.

We find that ![]()

![]() of the total PSF ellipticity variation in random pointings can be described with a single

parameter related to the change in telescope focus, confirming earlier results (e.g. Rhodes et al. 2007).

However, we find that additional variations

are still significant. In particular, we detect a dependence

on the relative angle

between the pointing and the orbital telescope movement

of the total PSF ellipticity variation in random pointings can be described with a single

parameter related to the change in telescope focus, confirming earlier results (e.g. Rhodes et al. 2007).

However, we find that additional variations

are still significant. In particular, we detect a dependence

on the relative angle

between the pointing and the orbital telescope movement![]() ,

suggesting that heating in the sunlight does not only change the

telescope focus, but also creates slight additional aberrations

dependent on the relative sun angle. These deviations may be coherent

between COSMOS tiles observed under similar orbital conditions.

To account for this effect, we split the COSMOS data into 24 epochs of

observations taken closely in time,

and determine a low-order, focus-dependent residual model from all

stars within one epoch.

We provide further details on our PSF correction scheme in

Appendix B.5.

,

suggesting that heating in the sunlight does not only change the

telescope focus, but also creates slight additional aberrations

dependent on the relative sun angle. These deviations may be coherent

between COSMOS tiles observed under similar orbital conditions.

To account for this effect, we split the COSMOS data into 24 epochs of

observations taken closely in time,

and determine a low-order, focus-dependent residual model from all

stars within one epoch.

We provide further details on our PSF correction scheme in

Appendix B.5.

As an additional observational challenge, the COSMOS data suffer from defects in the ACS CCDs, which are caused by the continuous cosmic ray bombardment in space. These defects act as charge traps reducing the charge-transfer-efficiency (CTE), an effect referred to as charge-transfer-inefficiency (CTI). When the image of an object is transferred across such a defect during parallel read-out, a fraction of its charge is trapped and statistically released, effectively creating charge-trails following objects in the read-out y-direction (e.g. Massey et al. 2010; Chiaberge et al. 2009; Rhodes et al. 2007). For weak lensing measurements the dominant effect of CTI is the introduction of a spurious ellipticity component in the read-out direction. In contrast to PSF effects, CTI affects objects non-linearly due to the limited depth of charge traps. Thus, the two effects must be corrected separately. As done by Rhodes et al. (2007), we employ an empirical correction for galaxy shapes, but also take the dependence on sky background into account. Making use of the CTI flux-dependence, we additionally determine and apply a parametric CTI model for stars, which is important as PSF and CTI-induced ellipticity get mixed otherwise. We present details on our CTI correction schemes for stars in Appendix B.4 and for galaxies in Appendix B.6. Note that Massey et al. (2010) recently presented a method to correct for CTI directly on the image level. We find that the methods employed here are sufficient for our science analysis, as also confirmed by the tests presented in Sect. 4. However, for weak lensing data with much stronger CTE degradation, such as ACS data taken after Servicing Mission 4, their pixel-based correction should be superior.

4 2D shear-shear correlations and tests for systematics

To measure the cosmological signal and conduct tests for systematics we compute the second-order shear-shear correlations

from galaxy pairs separated by

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=5.5cm]{13577f4a.eps}\hspace*{4mm}

\in...

...4b.eps}\hspace*{4mm}

\includegraphics[width=5.5cm]{13577f4c.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/08/aa13577-09/Timg120.png)

|

Figure 4:

Decomposition of the shear field into E- and B-modes using the shear correlation function

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

As an important consistency check in weak gravitational lensing, the

signal can be decomposed into a curl-free component (E-mode) and a curl

component (B-mode).

Given that lensing creates only E-modes, the detection of a significant

B-mode indicates the presence of uncorrected residual systematics in

the data.

Crittenden et al. (2002) show that ![]() can be decomposed into E- and B-modes as

can be decomposed into E- and B-modes as

with

We plot this decomposition for our COSMOS catalogue in the left panel of Fig. 4. Given that the integration in (9) extends to infinity, we employ

An

E/B-mode decomposition,

for which the correlation between different scales is weaker,

is provided by the dispersion of the aperture mass (Schneider 1996)

with

The cleanest E/B-mode decomposition is given by the

ring statistics (Eifler et al. 2010; Schneider & Kilbinger 2007; see also Fu & Kilbinger 2010), which can be computed from the correlation function using a finite interval with non-zero lower integration limit

with functions

The non-detection of significant B-modes in our shear catalogue is an important confirmation for our correction schemes for instrumental effects and suggests that the measured signal is truly of cosmological origin.

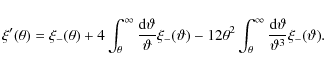

As a final test for shear-related systematics we compute the correlation between corrected galaxy shear estimates ![]() and uncorrected stellar ellipticities e*

and uncorrected stellar ellipticities e*

which we normalize using the stellar auto-correlation as suggested by Bacon et al. (2003). As detailed in Appendix B.6, we employ a somewhat ad hoc residual correction for a very weak remaining instrumental signal. We find that

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{13577f5.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/08/aa13577-09/Timg142.png)

|

Figure 5: Cross-correlation between galaxy shear estimates and uncorrected stellar ellipticities as defined in (12). The signal is consistent with zero if the residual ellipticity correction discussed in Appendix B.6 is applied (circles). Even without this correction (triangles) it is at a level negligible compared to the expected cosmological signal (dotted curves), except for the largest scales, where the error-budget is anyway dominated by sampling variance. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

5 Weak lensing tomography

In this section we present our analysis of the redshift dependence of

the lensing signal

in COSMOS. We start with the

definition

of redshift bins in Sect. 5.1, summarize the

theoretical framework in Sect. 5.2, describe

our angular binning and treatment of intrinsic galaxy alignments in

Sect. 5.3, elaborate on the covariance estimation in Sect. 5.4, present

the measured redshift scaling in Sect. 5.5, and discuss indications for a contamination of faint

![]() galaxies with high redshift galaxies in Sect. 5.6.

galaxies with high redshift galaxies in Sect. 5.6.

5.1 Redshift binning

We split the galaxies with individual COSMOS-30 photo-zs into

five

redshift bins, as summarized in Table 1 and illustrated in Fig. 6.

We chose the intermediate limits

z=(0.6,1.0,1.3)

such that

the Balmer/4000 Å break is

approximately located at the centre of one of the broadband r+i+z+filters.

This minimizes the impact of possible artifical clustering in photo-z space

and hence scatter between redshift bins

for

galaxies too faint to be detected in the Subaru medium bands.

Given our chosen limits,

most catastrophic redshift

errors are faint bin 5 galaxies identified as bin 1 (Sect. 2.2.1).

Thus, we do not include

z<0.6

galaxies with i+>24 in our

analysis due to their potential contamination with high redshift

galaxies, but study their lensing signal separately in Sect. 5.6.

We use all galaxies without individual photo-z estimates with

22<i814<26.7![]() as a broad bin 6, for which we

estimated the redshift distribution in Sect. 2.2.2.

as a broad bin 6, for which we

estimated the redshift distribution in Sect. 2.2.2.

Table 1: Definition of redshift bins, number of contributing galaxies, and mean redshifts.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{13577f6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/08/aa13577-09/Timg147.png)

|

Figure 6:

Redshift distributions for our tomography analysis.

The solid-line histogram shows the individual COSMOS-30 redshifts used for bins 1 to 5, while

the difference between the dashed and solid histograms indicates the 24<i+<25 galaxies with

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

5.2 Theoretical description

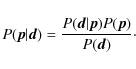

Extending the formalism from Sect. 4, we

split the galaxy sample into redshift bins and cross-correlate shear estimates between

bins k and l

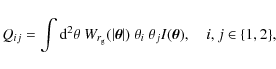

where the summation extends over all galaxies i in bin k, and all galaxies j in bin l. These are estimates for the shear cross-correlation functions

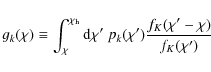

where

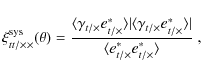

with the Hubble parameter H0, matter density

are weighted according to the redshift distributions pk of the two considered redshift bins (see e.g. Bartelmann & Schneider 2001; Simon et al. 2004; Kaiser 1992).

5.3 Angular binning and treatment of intrinsic galaxy alignments

Our six redshift bins define a total of 21 combinations of redshift bin

pairs (including auto-correlations).

For each redshift bin

pair (k,l), we compute the shear cross-correlations

![]() and

and

![]() in six logarithmic angular bins

between 0

in six logarithmic angular bins

between 0

![]() 2 and

2 and ![]() .

We include all of these angular and redshift bin combinations in the analysis of the weak

lensing redshift scaling presented in this section, to keep it as general as possible.

Yet, for the cosmological parameter estimation in

Sect. 6, we

carefully select the included bins

to minimize potential bias by intrinsic galaxy alignments and uncertainties

in theoretical model predictions.

.

We include all of these angular and redshift bin combinations in the analysis of the weak

lensing redshift scaling presented in this section, to keep it as general as possible.

Yet, for the cosmological parameter estimation in

Sect. 6, we

carefully select the included bins

to minimize potential bias by intrinsic galaxy alignments and uncertainties

in theoretical model predictions.

In order to minimize potential contamination by intrinsic alignments of physically associated galaxies, we exclude the auto-correlations of the relatively narrow redshift bins 1 to 5. These contain the highest fraction of galaxy pairs at similar redshift, and hence carry the strongest potential contamination.

An additional contamination may originate from

alignments between intrinsic galaxy shapes and their surrounding density field causing the gravitational shear (e.g. Hirata et al. 2007; Hirata & Seljak 2004).

A complete removal of this effect requires more advanced analysis schemes (e.g. Joachimi & Schneider 2008),

which we postpone to a future study.

Yet, following the suggestion by Mandelbaum et al. (2006), we exclude luminous red

galaxies (LRGs) in the computation of the shear-shear correlations used for the

parameter estimation.

This reduces potential contamination, given that LRGs were found to carry the strongest alignment signal

(Hirata et al. 2007; Mandelbaum et al. 2006,2009).

We select these galaxies from the Ilbert et al. (2009)

photo-z catalogue with cuts in the photometric type

![]() (``ellipticals'')

and absolute magnitude

(``ellipticals'')

and absolute magnitude

![]() ,

excluding a total of

5751 galaxies

,

excluding a total of

5751 galaxies![]() .

We accordingly adapt the redshift distribution for the parameter estimation.

.

We accordingly adapt the redshift distribution for the parameter estimation.

In the cosmological parameter estimation,

we additionally exclude the smallest angular

bin (

![]() ), for which

the theoretical model predictions have the largest uncertainty due to

required non-linear corrections

(Sect. 6.2) and the influence of

baryons (e.g. Rudd et al. 2008).

), for which

the theoretical model predictions have the largest uncertainty due to

required non-linear corrections

(Sect. 6.2) and the influence of

baryons (e.g. Rudd et al. 2008).

While we do not exclude LRGs and the smallest angular bin for the redshift scaling analysis presented in the current section, we have verified that their exclusion leads to only very small changes, which are well within the statistical errors and do not affect our conclusions.

5.4 Covariance estimation

In order to interpret our measurement and constrain cosmological parameters, we need to reliably estimate the data covariance matrix and its inverse. Massey et al. (2007c) estimate a covariance for their analysis from the variation between the four COSMOS quadrants. This approach yields too few independent realizations and may substantially underestimate the true errors (Hartlap et al. 2007). We also do not employ a covariance for Gaussian statistics (e.g. Joachimi et al. 2008) due to the neglected influence of non-Gaussian sampling variance. This is particularly important for the small-scale signal probed with COSMOS (Semboloni et al. 2007; Kilbinger & Schneider 2005). Instead, we estimate the covariance matrix from 288 realizations of COSMOS-like fields obtained from ray-tracing through the Millennium Simulation (Springel et al. 2005), which combines a large simulated volume yielding many quasi-independent lines-of-sight with a relatively high spatial and mass resolution. The latter is needed to fully utilize the small-scale signal measureable in a deep space-based survey.

The details of the ray-tracing analysis are given in Hilbert et al. (2009).

In brief, we use tilted lines-of-sight through the simulation to avoid

repetition of structures along the backwards lightcone, providing us

with 32quasi-independent

![]() fields, which we further subdivide into nine COSMOS-like subfields, yielding a total of 288 realizations.

We randomly populate the fields with galaxies,

employing the same galaxy number density, field masks, shape noise,

and redshift distribution as in the COSMOS data.

We incorporate photometric redshift errors for bins 1 to 5 by randomly

misplacing galaxy redshifts assuming a (symmetric) Gaussian scatter according to the

fields, which we further subdivide into nine COSMOS-like subfields, yielding a total of 288 realizations.

We randomly populate the fields with galaxies,

employing the same galaxy number density, field masks, shape noise,

and redshift distribution as in the COSMOS data.

We incorporate photometric redshift errors for bins 1 to 5 by randomly

misplacing galaxy redshifts assuming a (symmetric) Gaussian scatter according to the ![]() errors in the photo-z

catalogue.

In contrast, the redshift calibration uncertainty for bin 6 is not

a stochastic but a systematic error, which we account for in the

cosmological model fitting in Sect. 6.

errors in the photo-z

catalogue.

In contrast, the redshift calibration uncertainty for bin 6 is not

a stochastic but a systematic error, which we account for in the

cosmological model fitting in Sect. 6.

The value of

![]() used for the Millennium Simulation is slightly high compared

to current estimates.

This will lead to an overestimation of

the errors, hence our analysis can be considered slightly conservative.

We have to neglect the cosmology dependence of the covariance

(Eifler et al. 2009) in the parameter estimation, given that

we have currently only one simulation with high resolution and large volume at hand.

used for the Millennium Simulation is slightly high compared

to current estimates.

This will lead to an overestimation of

the errors, hence our analysis can be considered slightly conservative.

We have to neglect the cosmology dependence of the covariance

(Eifler et al. 2009) in the parameter estimation, given that

we have currently only one simulation with high resolution and large volume at hand.

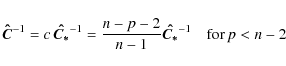

We need to invert the covariance matrix for the cosmological parameter estimation

in Sect. 6.

While the covariance estimate

![]() from the ray-tracing realizations is unbiased, a bias is introduced by correlated noise in the matrix inversion.

To obtain an unbiased estimate for the inverse covariance

from the ray-tracing realizations is unbiased, a bias is introduced by correlated noise in the matrix inversion.

To obtain an unbiased estimate for the inverse covariance

![]() ,

we apply the correction

,

we apply the correction

discussed in Hartlap et al. (2007), where n=288 is the number of independent realizations and p is the dimension of the data vector. As discussed in Sect. 5.3, we exclude the smallest angular bin and auto-correlations of redshift bins 1 to 5, yielding p=160 and a moderate correction factor

In order to limit the required correction for the covariance inversion, we do not include more angular bins in our analysis. We have therefore optimized the bin limits using Gaussian covariances (Joachimi et al. 2008) and a Fisher-matrix analysis aiming at maximal sensitivity to cosmological parameters.

5.5 Redshift scaling of shear-shear cross-correlations

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13577f7.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/08/aa13577-09/Timg174.png)

|

Figure 7:

Shear-shear cross-correlations

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

We plot the shear-shear cross-correlations

![]() between all redshift bins and the broad

bin 6 in Fig. 7.

These cross-correlations carry the lowest

shot noise and

shape noise due to the large number of galaxies in bin 6.

The good agreement between the data and

between all redshift bins and the broad

bin 6 in Fig. 7.

These cross-correlations carry the lowest

shot noise and

shape noise due to the large number of galaxies in bin 6.

The good agreement between the data and ![]() CDM model already indicates

that the weak lensing signal roughly scales with redshift as expected.

The errors correspond to the square root of the diagonal elements of the full ray-tracing

covariance.

Points are correlated not only within a redshift

bin pair, but also between different redshift combinations, as their lensing signal is partially

caused by the same foreground structures. In addition, galaxies in bin 6 contribute to different cross-correlations.

Note that our relatively broad angular bins lead to a significant variation of the theoretical models within a bin.

When computing an average model prediction for a bin, we therefore weight according to the

CDM model already indicates

that the weak lensing signal roughly scales with redshift as expected.

The errors correspond to the square root of the diagonal elements of the full ray-tracing

covariance.

Points are correlated not only within a redshift

bin pair, but also between different redshift combinations, as their lensing signal is partially

caused by the same foreground structures. In addition, galaxies in bin 6 contribute to different cross-correlations.

Note that our relatively broad angular bins lead to a significant variation of the theoretical models within a bin.

When computing an average model prediction for a bin, we therefore weight according to the ![]() -dependent number of galaxy pairs within this bin.

Likewise, we plot points at their effective

-dependent number of galaxy pairs within this bin.

Likewise, we plot points at their effective ![]() ,

which has been weighted accordingly.

,

which has been weighted accordingly.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13577f8a.ps}\hspace*{4mm}

\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13577f8b.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/08/aa13577-09/Timg175.png)

|

Figure 8:

Shear-shear redshift scaling for |

| Open with DEXTER | |

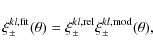

Instead of plotting 21 separation-dependent, noisy cross-correlations,

we condense the information into a single plot showing the redshift dependence of the signal.

Here we assume that the predictions for our reference cosmology describe the relative angular dependence of

the signal sufficiently well,

and fit the data points as

where

5.6 Contamination of the excluded faint z < 0.6 sample with high-z galaxies

As discussed in Sect. 2.2, we expect a significant

fraction of faint

![]() galaxies with assigned

photometric redshift

galaxies with assigned

photometric redshift

![]() to be truly located at high redshifts

to be truly located at high redshifts

![]() .

To test this hypothesis, we plot the collapsed

shear cross-correlations

for different samples of galaxies with assigned

.

To test this hypothesis, we plot the collapsed

shear cross-correlations

for different samples of galaxies with assigned

![]() in Fig. 9.

For the i+< 24 galaxies used in the cosmological analysis the

signal is well consistent with expectations, suggesting negligible

contamination. For a 24<i+<25 sample with single-peaked photo-z

probability distribution

a mild increase is detected.

This is still consistent with

expectations, suggesting at most low contamination.

We also study a sample of galaxies each of which has a

significant secondary peak in their photometric redshift probability

distribution at

in Fig. 9.

For the i+< 24 galaxies used in the cosmological analysis the

signal is well consistent with expectations, suggesting negligible

contamination. For a 24<i+<25 sample with single-peaked photo-z

probability distribution

a mild increase is detected.

This is still consistent with

expectations, suggesting at most low contamination.

We also study a sample of galaxies each of which has a

significant secondary peak in their photometric redshift probability

distribution at

![]() ,

amounting to 36% of all 24<i+<25 galaxies with

,

amounting to 36% of all 24<i+<25 galaxies with

![]() .

This sample shows a strong boost in the lensing signal,

suggesting strong contamination with high-redshift galaxies.

.

This sample shows a strong boost in the lensing signal,

suggesting strong contamination with high-redshift galaxies.

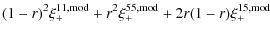

We can obtain a rough estimate for this contamination if we assume that the

shear signal does actually scale as in our reference ![]() CDM cosmology.

For simplicity we assume that the cross-contamination can be described as a

uni-directional scatter from bin 5 to bin 1, and that the true redshifts of

the misplaced galaxies follow the distribution within bin 5.

The expected contaminated signal is then given as a linear superposition of

the cross-correlation predictions with bin 1 and bin 5 respectively, according

to the relative number of contributing galaxy pairs

CDM cosmology.

For simplicity we assume that the cross-contamination can be described as a

uni-directional scatter from bin 5 to bin 1, and that the true redshifts of

the misplaced galaxies follow the distribution within bin 5.

The expected contaminated signal is then given as a linear superposition of

the cross-correlation predictions with bin 1 and bin 5 respectively, according

to the relative number of contributing galaxy pairs

where r is the contamination fraction, i.e. the fraction of the bin 1 galaxies with 24<i+<25 and a significant secondary peak in their photo-z PDF, which should have been placed into bin 5. We fit the measured shear-shear cross-correlations

Our analysis provides an interesting confirmation for the photometric redshift analysis by Ilbert et al. (2009), which apparently succeeds in identifying sub-samples of (mostly) uncontaminated and potentially contaminated galaxies quite efficiently.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13577f9.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/08/aa13577-09/Timg188.png)

|

Figure 9:

Shear-shear redshift scaling for

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

6 Constraints on cosmological parameters

6.1 Parameter estimation and considered cosmological models

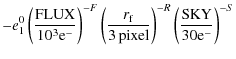

The statistical analysis of the shear tomography correlation

functions, assembled as data vector ![]() ,

is

based on a standard Bayesian approach

(e.g. MacKay 2003). Therein, prior knowledge of model

parameters

,

is

based on a standard Bayesian approach

(e.g. MacKay 2003). Therein, prior knowledge of model

parameters ![]() is combined with the information on those

parameters inferred from the new observation and expressed as

posterior probability distribution function (PDF) of

is combined with the information on those

parameters inferred from the new observation and expressed as

posterior probability distribution function (PDF) of ![]() :

:

|

(20) |

Here,

![\begin{displaymath}\ln

P(\vec{d}\vert\vec{p})=-\frac{1}{2}\left[\vec{d}-\vec{m}(...

...ec{C}^{-1}\left[\vec{d}-\vec{m}(\vec{p})\right]+ {\rm const} ,

\end{displaymath}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/08/aa13577-09/img195.png)

|

(21) |

where

In our analysis we consider different cosmological models,

which are characterized by the parameters

![]() ,

with the

dark energy density

,

with the

dark energy density

![]() ,

matter

density

,

matter

density

![]() ,

power spectrum normalization

,

power spectrum normalization ![]() ,

Hubble parameter h, and (constant) dark energy equation of state parameter w. Here, fz denotes a nuisance parameter

encapsulating the uncertainty in the redshift calibration for bin 6 as

,

Hubble parameter h, and (constant) dark energy equation of state parameter w. Here, fz denotes a nuisance parameter

encapsulating the uncertainty in the redshift calibration for bin 6 as

![]() ,

which was discussed in Sect. 2.2.2.

We consider

,

which was discussed in Sect. 2.2.2.

We consider

- a flat

CDM cosmology with fixed w=-1,

CDM cosmology with fixed w=-1,

![$\Omega_{\rm m}\in[0,1]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/08/aa13577-09/img200.png) ,

and

,

and

,

,

- a general (non-flat)

CDM cosmology with fixed w=-1 and

CDM cosmology with fixed w=-1 and

![$\Omega_{\rm DE}=\Omega_\Lambda\in[0,2]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/08/aa13577-09/img202.png) ,

,

![$\Omega_{\rm m}\in[0,1.6]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/08/aa13577-09/img203.png) ,

and

,

and

- a flat

CDM cosmology with

CDM cosmology with

![$w\in [-2,0]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/08/aa13577-09/img27.png) ,

,

![$\Omega_{\rm m}\in[0,1]$](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/08/aa13577-09/img200.png) ,

and

,

and

.

.

In our default analysis scheme we also apply a

Gaussian prior

for

![]() ,

and

assume a fixed baryon density

,

and

assume a fixed baryon density

![]() and spectral

index

and spectral

index

![]() as consistent with Dunkley et al. (2009), where the

small

uncertainties on

as consistent with Dunkley et al. (2009), where the

small

uncertainties on

![]() and

and ![]() are negligible for our analysis.

Note that

we relax these priors for parts of the analysis in

Sects. 6.3.2 and 6.4.

are negligible for our analysis.

Note that

we relax these priors for parts of the analysis in

Sects. 6.3.2 and 6.4.

The practical challenge of the parameter estimation is to evaluate the posterior within a reasonable time, as the computation of one model vector for shear tomography correlations is time-intensive. For an efficient sampling of the parameter space, we employ the Population Monte Carlo (PMC) method as described in Wraith et al. (2009). This algorithm is an adaptive importance-sampling technique (Cappé et al. 2008): instead of creating a sample under the posterior as done in traditional Monte-Carlo Markov chain (MCMC) techniques (e.g. Christensen et al. 2001), points are sampled from a simple distribution, the so-called proposal, in our case a mixture of eight Gaussians. Each point is then weighted by the ratio of the proposal to the posterior at that point. In a number of iterative steps, the proposal function is adapted to give better and better approximations to the posterior. We run the PMC algorithm for up to eight iterations, using 5000 sample points in each iteration. To reduce the Monte-Carlo variance, we use larger samples with 10 000 to 20 000 points for the final iteration. These are used to create density histograms, mean parameter values, and confidence regions. Depending on the experiment, the effective sample size of the final importance sample was between 7500 and 17 700. We also cross-checked parts of the analysis with an independently developed code which is based on the traditional but less efficient MCMC approach, finding fully consistent results.

6.2 Non-linear power spectrum corrections

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{13577f10.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/08/aa13577-09/Timg213.png)

|

Figure 10:

Comparison of the fit formulae for the non-linear growth of structure in wCDM cosmologies. Shown is the three-dimensional matter power spectrum, normalized by the corresponding |

| Open with DEXTER | |

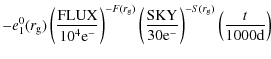

To calculate model

predictions for the correlation functions according to (14),

(15), and (16), we need to

evaluate the involved distance ratios and compute the non-linear power spectrum

![]() .

Given a set of parameter values, the computation of the distances and the linearly extrapolated power spectrum

is straightforward.

We employ the transfer function by Eisenstein & Hu (1998) for the latter, taking baryon damping but no oscillations into account (``shape fit'').

.

Given a set of parameter values, the computation of the distances and the linearly extrapolated power spectrum

is straightforward.

We employ the transfer function by Eisenstein & Hu (1998) for the latter, taking baryon damping but no oscillations into account (``shape fit'').

For ![]() CDM models we estimate the full

non-linear power spectrum according to Smith et al. (2003).

McDonald et al. (2006) also provide non-linear power spectrum corrections for

CDM models we estimate the full

non-linear power spectrum according to Smith et al. (2003).

McDonald et al. (2006) also provide non-linear power spectrum corrections for ![]() ,

but these were

tested for a narrow range in

,

but these were

tested for a narrow range in

![]() only.

We want to keep our analysis as general as possible, not having to assume such a strong prior on

only.

We want to keep our analysis as general as possible, not having to assume such a strong prior on ![]() .

Following the icosmo code

(Refregier et al. 2008)

we instead

interpolate the non-linear corrections from Smith et al. (2003) between the cases

of a

.

Following the icosmo code

(Refregier et al. 2008)

we instead

interpolate the non-linear corrections from Smith et al. (2003) between the cases

of a ![]() CDM cosmology (w=-1) and an OCDM cosmology,

acting as a dark energy with w=-1/3.

This is achieved by replacing the parameter

CDM cosmology (w=-1) and an OCDM cosmology,

acting as a dark energy with w=-1/3.

This is achieved by replacing the parameter

![]() in the halo model fitting function (Smith et al. 2003).

This parameter is used to interpolate between spatially flat models with

dark energy (f=1) and an open Universe without dark energy (f=0).

We substitute f by a new parameter

in the halo model fitting function (Smith et al. 2003).

This parameter is used to interpolate between spatially flat models with

dark energy (f=1) and an open Universe without dark energy (f=0).

We substitute f by a new parameter

![]() .

Thus, we obtain f'=1 for

.

Thus, we obtain f'=1 for ![]() CDM and f'=0 for wCDM with w=-1/3, mimicking an OCDM cosmology for which the original parameter f vanished as well.

CDM and f'=0 for wCDM with w=-1/3, mimicking an OCDM cosmology for which the original parameter f vanished as well.

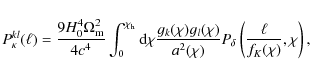

To test this simplistic approximation, we compare the computed

corrections for

w=(-0.5,-1.5) to the fitting formulae from

McDonald et al. (2006) in

Fig. 10.

Note that we use our fiducial cosmological parameters to obtain these curves, except for

![]() ,

to match

,

to match

![]() from McDonald et al. (2006).

For most of the scales probed by our measurement the two descriptions agree

reasonably well. The modification of the halo fit follows the fits to the

simulations more accurately on large scales and at higher redshift, while it

does not reproduce the tendency of the fits by McDonald et al. (2006) to drop off for

large wave vectors. The precision of the modification outlined above is

sufficient for our aim to provide a proof of concept for weak lensing dark

energy measurements. However, future measurements with larger data sets will

require accurate fitting formulae for general w cosmologies.

from McDonald et al. (2006).

For most of the scales probed by our measurement the two descriptions agree

reasonably well. The modification of the halo fit follows the fits to the

simulations more accurately on large scales and at higher redshift, while it

does not reproduce the tendency of the fits by McDonald et al. (2006) to drop off for

large wave vectors. The precision of the modification outlined above is

sufficient for our aim to provide a proof of concept for weak lensing dark

energy measurements. However, future measurements with larger data sets will

require accurate fitting formulae for general w cosmologies.

Table 2:

Constraints on

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and w from the COSMOS data for different

cosmological models and analysis schemes.

,

and w from the COSMOS data for different

cosmological models and analysis schemes.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.4cm,clip]{13577f11.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/08/aa13577-09/Timg234.png)

|

Figure 11:

Comparison of our constraints on

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

6.3 Cosmological constraints from COSMOS

6.3.1 Flat  CDM cosmology

CDM cosmology

We plot our constraints on

![]() and

and ![]() for a flat

for a flat

![]() CDM cosmology and our default 3D lensing analysis scheme in Fig. 11 (solid contours),

showing the typical ``banana-shaped'' degeneracy, from which we

compute

CDM cosmology and our default 3D lensing analysis scheme in Fig. 11 (solid contours),

showing the typical ``banana-shaped'' degeneracy, from which we

compute![]()

Here we marginalize over the uncertainties in h and the parameter fz encapsulating the uncertainty in the redshift calibration for bin 6, where we find that fz is nearly uncorrelated with

For comparison we also conduct a classic 2D lensing analysis (dashed contours in Fig. 11),

where we use only the total redshift distribution and do not split galaxies into redshift bins.

We find that the 2D and 3D analyses yield consistent results with substantially overlapping ![]() regions, as expected.

Yet, the constraints from the 2D analysis shift towards lower

regions, as expected.

Yet, the constraints from the 2D analysis shift towards lower

![]() .

The difference

is not surprising given

that the strongest contribution to the lensing signal in COSMOS comes from massive structures near

.

The difference

is not surprising given

that the strongest contribution to the lensing signal in COSMOS comes from massive structures near ![]() (Scoville et al. 2007b; Massey et al. 2007b),

boosting the signal for high redshift sources, but leading to a lower

signal for galaxies at low and intermediate redshifts (see right panel

of Fig. 8).

The 3D lensing analysis can properly combine these measurements, also accounting

for the stronger impact of sampling variance at low redshifts.

In contrast, the 2D lensing analysis leads to a rather low (but still

consistent) estimate for

(Scoville et al. 2007b; Massey et al. 2007b),

boosting the signal for high redshift sources, but leading to a lower

signal for galaxies at low and intermediate redshifts (see right panel

of Fig. 8).

The 3D lensing analysis can properly combine these measurements, also accounting

for the stronger impact of sampling variance at low redshifts.

In contrast, the 2D lensing analysis leads to a rather low (but still

consistent) estimate for ![]() ,

due to the large number of low and

intermediate redshift galaxies with low shear signal.

,

due to the large number of low and

intermediate redshift galaxies with low shear signal.

![\begin{figure}

\includegraphics[width=5.9cm]{13577f12a.eps}\hspace*{4mm}

\incl...

...b.eps}\hspace*{4mm}

\includegraphics[width=5.9cm]{13577f12c.eps}