| Issue |

A&A

Volume 634, February 2020

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A12 | |

| Number of page(s) | 11 | |

| Section | Planets and planetary systems | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201937248 | |

| Published online | 28 January 2020 | |

Tidal evolution of circumbinary systems with arbitrary eccentricities: applications for Kepler systems

1

Observatorio Astronómico de Córdoba, Universidad Nacional de Córdoba,

Laprida 854,

Córdoba

X5000GBR,

Argentina

e-mail: fzoppetti@oac.unc.edu.ar

2

Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET),

Buenos Aires,

Argentina

3

CONICET, Instituto de Astronomía Teórica y Experimental,

Laprida 854,

Córdoba

X5000GBR,

Argentina

Received:

3

December

2019

Accepted:

15

December

2019

We present an extended version of the Constant Time Lag analytical approach for the tidal evolution of circumbinary planets introduced in our previous work. The model is self-consistent, in the sense that all tidal interactions between pairs are computed, regardless of their size. We derive analytical expressions for the variational equations governing the spin and orbital evolution, which are expressed as high-order elliptical expansions in the semimajor axis ratio but retain closed form in terms of the binary and planetary eccentricities. These are found to reproduce the results of the numerical simulations with arbitrary eccentricities very well, as well as reducing to our previous results in the low-eccentric case. Our model is then applied to the well-characterised Kepler circumbinary systems by analysing the tidal timescales and unveiling the tidal flow around each different system. In all cases we find that the spins reach stationary values much faster than the characteristic timescale of the orbital evolution, indicating that all Kepler circumbinary planets are expected to be in a sub-synchronous state. On the other hand, all systems are located in a tidal flow leading to outward migration; thus the proximity of the planets to the orbital instability limit may have been even greater in the past. Additionally, Kepler systems may have suffered a significant tidally induced eccentricity damping, which may be related to their proximity to the capture eccentricity. To help understand the predictions of our model, we also offer a simple geometrical interpretation of our results.

Key words: methods: analytical / planets and satellites: dynamical evolution and stability / planet–star interactions

© ESO 2020

1 Introduction

Among the main characteristics of the nine well-characterised circumbinary (CB) systems discovered so far by the Kepler mission, probably the most remarkable one is the proximity of the planets to the binaries. This feature implies that most of the circumbinary planets (CBPs) are located very close to the stability limit (Holman & Wiegert 1999) where, in addition, the in situ formation is very unlikely due to perturbations of the binary (Lines et al. 2014).

While it is widely accepted that migration by interaction with a protoplanetary disc took place in these systems (Dunhill & Alexander 2013), it is not yet clear what role tidal forces played in the subsequent dynamical evolution, which have the peculiarity of being exerted by two central objects of comparable masses and may have had an important effect in such compact systems.

In Zoppetti et al. (2019a) we presented a self-consistent weak friction model for tides on a CBP. We used Kepler-38 system as a testing case and found several interesting features: for example the planet synchronised its spin in a sub-synchronous equilibrium state and, on longer timescales, it migrated outward from the binary. We also derived analytical expressions for the variational equations of the orbital and spin evolution based on low-order elliptical expansions in semimajor axis ratio and eccentricities. This analytical approach was reduced to the two-body case when one of the central masses was taken equal to zero and it reproduced the results of our low-eccentric numerical simulations very well. However, the low-order expansion in eccentricities of our analytical model did not allow its direct application to the eccentric Kepler systems such as Kepler-34 (Welsh et al. 2012) and Kepler-413 (Kostov et al. 2014).

In this work, we present and discuss an extended version of our self-consistent weak friction (Constant Time Lag; CTL) tidal model which is valid for any binary and planetary eccentricity. We apply the results to the well-characterised nine Kepler systems in an attempt to reproduce their past tidal evolution, as well as unveiling the role played by tidal forces in determining their current orbital parameters.

This paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we review the construction of the variational equations for the spin and orbital evolution in a self-consistent manner. In Sect. 3, we present the analytical expressions of the variational equations in closed form for the eccentricities and compare their predictions with results obtained from numerical simulations, as well as with our original low-order expanded model. In Sect. 4, we apply our model to the Kepler CB planets by computing the characteristic timescales for their evolution and by reproducing the tidal flow around each system. A simple geometrical interpretation of the main results of our model is offered in Sect. 4.2 to better understand these dynamical characteristics. Finally, Sect. 5 summarises and discusses our main results.

2 Review of the model

We return to the problem of a binary system with stellar masses m0 and m1, and a CBP with mass m2. The binary and the planet share the same orbital plane and their spins are perpendicular to it. We further assume that each body is an extended mass with physical radius  and deformable due to the tidal effects of its companions.

and deformable due to the tidal effects of its companions.

We again assume that the internal dissipation due to tides in each of the three bodies is governed by the CTL and is, therefore, subject to the description suffested by Mignard (1979). In our previous work (Zoppetti et al. 2019a) we demonstrated that, in absence of any mean-motion commensurability between m1 and m2, the cross tides can be neglected and the only tidal forces that need to be taken into account on each body mi are those caused by the deformation that the mass mi itself induces on its companions. For this reason, in a multi-body tidal model like the one we are studying, the tides on each body can be simply computed by summing the forces and torques between deforming-deformed pairs as given in Eqs. (5) and (6) of Mignard (1979).

In an inertial frame with arbitrary origin, where the position of each body mi is denoted as Ri, the orbital evolution equations may be expressed as the sum of the point-mass and tidal interactions, which is

(1)

(1)

where  is the gravitational constant and Δij ≡Ri −Rj. We denoted by Fij the tidal force acting on mi due to the deformation that it induces on mj and, following Ferraz-Mello et al. (2008), we also took into account the reacting forces when computing the tides on each mass mi. According to Mignard (1979), these can be expressed by

is the gravitational constant and Δij ≡Ri −Rj. We denoted by Fij the tidal force acting on mi due to the deformation that it induces on mj and, following Ferraz-Mello et al. (2008), we also took into account the reacting forces when computing the tides on each mass mi. According to Mignard (1979), these can be expressed by

![\begin{eqnarray*} {{\bm{F}}_{{ij}}} = -\frac{\mathcal{K}_{ij}} {{|{{\bm{\Delta}}_{{ij}}}|}^{10}} \left[ 2({\bm{\Delta}}_{{{ij}}} \cdot {{\dot{\bm{\Delta}}}_{{ij}}}) {{\bm \Delta}_{ij}} + {{{\bm \Delta}}^2_{{ij}}} ( {{\bm{\Delta}}_{{ij}}} \times {{\bm{\Omega}}_{{j}}} + {{\dot{\bm{\Delta}}}_{{ij}}}) \right]\end{eqnarray*}](/articles/aa/full_html/2020/02/aa37248-19/aa37248-19-eq4.png) (2)

(2)

where Ωj is the spin vector of mj (assumed parallel to the orbital angular momenta) and the magnitude factor of the tidal force  is given by

is given by

(3)

(3)

where k2j and Δtj are the second degree Love number and the time-lag of the body mj. Note that we have neglected the contribution of the static tides since, in the absence of any mean-motion resonance, it does not introduce any angular momentum exchange and therefore yields no secular change in the spins nor in the orbital evolution.

While Eq. (1) governs the orbit, the rotational dynamics can be deduced from the conservation of the total angular momentum. Assuming that the variation in the spin angular momenta of the body mi is only due to the contributions associated to its own deformation, we can uncouple the spin evolution equations of each body to obtain

![\begin{equation*} \frac{{\textrm{d}{\bm{\Omega}_{\bf{i}}}}}{\textrm{d}t} = \frac{1}{{\mathcal{C}}_i} \sum_{j \ne i} \frac{{\cal K}_{ji}}{{|{{\bm{\Delta}}_{{ji}}}|^6}} \bigg[ \frac{{{\bm{\Delta}}_{{ji}}} \times {{{\dot{\bm{\Delta}}}}_{{ji}}}}{{|{\bm{\Delta}_{{ji}}}|^2}} - {{{\bm{\Omega}}_i}} \bigg], \ \ \ \ \ \ \ i= 0,1,2\end{equation*}](/articles/aa/full_html/2020/02/aa37248-19/aa37248-19-eq7.png) (4)

(4)

where  is the principal moment of inertia of mi.

is the principal moment of inertia of mi.

3 Analytical secular model for arbitrary eccentricities

To construct the analytical model of the orbital evolution Eq. (1) and the rotational evolution Eq. (4), we first adopt a Jacobi reference frame for the position and velocities of the bodies. In this system, the Jacobi position vectors of the masses ρi can be expressed in terms of their inertialcounterparts Ri as

(5)

(5)

where  . The transformation equations for the velocities are analogous.

. The transformation equations for the velocities are analogous.

To construct an analytical secular model valid for any binary and planetary eccentricity, we note that both Eqs. (1) and (2) depend on powers of the inverse of the relative distances, i.e.  , with n a positive integer. Assuming momentarily that t = Ri∕Rj < 1, we can write

, with n a positive integer. Assuming momentarily that t = Ri∕Rj < 1, we can write

(6)

(6)

where x is the cosine of the angle between both position vectors. The expansion of g(1) (t, x) in power series of t is well known

(7)

(7)

with Pk(x) the k-degree Legendre polynomial. In a similar manner, for n > 1 we can introduce “generalized” polinomials  such that

such that

(8)

(8)

such that  and

and  for all values of k ≥ 0. These new polynomials can be obtained for the original Legendre functions through recurrence relations. Writing g(n) (t, x) = g(n−1)(t, x) ⋅ g(1)(t, x), replacing each function by its series expansion and equating equal powers of t, we find

for all values of k ≥ 0. These new polynomials can be obtained for the original Legendre functions through recurrence relations. Writing g(n) (t, x) = g(n−1)(t, x) ⋅ g(1)(t, x), replacing each function by its series expansion and equating equal powers of t, we find

(9)

(9)

Introducing these expressions into the equations of motion, transforming the position and velocity vectors to Jacobi variables, and averaging over the mean longitudes λ1 and λ2, we find closed analytical expressions in terms of the eccentricities e1 and e2. The procedure is analogous to that followed by Mignard (1980) in the two-body case, with two important exceptions. First, we consider expansions in α = a1∕a2 up to fourth order (i.e. k = 4); second, we do not average over ϖ1 and ϖ2. While this would greatly simplify the resulting equations, in Zoppetti et al. (2019a) we observed that in some simulations, typically associated to low planetary eccentricity, the planet and the secondary star entered in the aligned secular mode Δϖ = ϖ2 − ϖ1 ~ 0. Thus, the perturbation terms dependent on Δϖ may have a net contribution in the long-term dynamics, at least for some initial conditions.

The complete procedure was carried out with the aid of an algebraic manipulator. Some intermediate expressions had to be expanded up to fifth order in t = Ri∕Rj to avoid loss of precision in the final results. The process was complex, especially for k > 2 where we found little benefit explicitly working with the  functions. However, we keep their definition and recurrence relations since they could be useful for quadrupole-level theories.

functions. However, we keep their definition and recurrence relations since they could be useful for quadrupole-level theories.

|

Fig. 1 Time derivative of the planetary spin rate Ω2 in our generic binary system as a function of α = a1∕a2. Each panelassumes different eccentricities for both orbits. Broad gray curves show results from semi-analytical calculationsand predictions from analytical models are depicted in thin lines. Values obtained with our original (Zoppetti et al. 2019a) are presented in blue, while the colors correspond to our current model with different orders in α. See inlaid box in left-hand plot for details. |

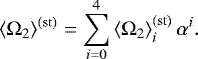

3.1 Planetary spin evolution

The process discussed previously was applied to both the orbital and spin variational equations. In the latter case, up to fourth order in semimajor axes ratio, we obtain

(10)

(10)

where n1 is the mean motion of the binary, n2 that of the planet, and

(11)

(11)

The coefficients  ,

,  and

and  , functions of the eccentricities and difference of longitudes of pericenter, are listed in Appendix A.

, functions of the eccentricities and difference of longitudes of pericenter, are listed in Appendix A.

To test the accuracy of our analytical model, we consider a generic circumbinary system with primary mass m0 = 1 M⊙ and physical radius  , plus a secondary star with mass m1 = m0∕3 and a physical radius

, plus a secondary star with mass m1 = m0∕3 and a physical radius  (Demircan & Kahraman 1991). The mass parameter of the binary is thus

(Demircan & Kahraman 1991). The mass parameter of the binary is thus  and the semimajor axis was set to a1 = 0.15 AU. For the planet, we chose m2 = 10 M⊕ and

and the semimajor axis was set to a1 = 0.15 AU. For the planet, we chose m2 = 10 M⊕ and  . We assumed a planetary principal moment of inertia equal to

. We assumed a planetary principal moment of inertia equal to  and a modified tidal dissipation factor of

and a modified tidal dissipation factor of  .

.

Figure 1 shows the time derivative of Ω2 as a function of α = a1∕a2 for three different sets of eccentricities. Different curves are used to show results using different models. Values obtained by numerically averaging Eq. (A.1) are depicted in broad grey curves, the analytical model from Zoppetti et al. (2019a) is shown in blue curves, and different variations of our current model are presented in other colors. We observe that our new α4 model fits the numerical values very well up to α ~ 0.35. The accuracy of our closed-form expressions in the eccentricities is evident when we analyse cases in which at least one of the orbits is moderately or highly eccentric. These situations were beyond the scope of our previous model. The low-eccentricity regime is well reproduced in all models, although again we obtain more precision with the closed fourth-order approach.

Curiously, due to the complexity of the power series, results obtained with α3 are not always better than those obtained with a quadrupole approximation. Moreover, in some cases (e.g. the central panel) both of these models yield predictions which are less accurate compared to those obtained from Zoppetti et al. (2019a). These results show the importance of using a high order expansion in semimajor axis ratio, even for systems that are not particularly compact.

The value of the stationary spin rate  predicted by our model can be calculated equating Eq. (A.1) to zero, which yields:

predicted by our model can be calculated equating Eq. (A.1) to zero, which yields:

(12)

(12)

where we have denoted  . Expanding this expression in power series of α up to fourth order gives

. Expanding this expression in power series of α up to fourth order gives

(13)

(13)

where the coefficients  are again listed in Appendix A.

are again listed in Appendix A.

Figure 2 shows the stationary spins (divided by n2), as function of α, calculated with the same analytical models considered in Fig. 1. To avoid too much clutter, we did not plot results corresponding to the α3 model. We also considered two different values of the binary mass parameter: results for  are shown in the left panels while those obtained for

are shown in the left panels while those obtained for  are graphed in the right panels.

are graphed in the right panels.

Comparisons with numerical estimations (broad gray curves) show that our current α4 model predict reliable stationary solution for any binary and planetary eccentricity up to α ~0.35. Larger mass ratios appear to require less sophisticated dynamical models, while at least a α4 model is necessary for low-mass secondary components. We also note that the mass of the secondary star (represented by  ) competes against the planetary eccentricity in establishing the stationarity solution: higher secondary masses tend to sub-synchronous solutions while, as in the two-body case, high planetary eccentricity leads to super-synchronous solutions. This fact was previously observed in Zoppetti et al. (2019a) for low-eccentric systems.

) competes against the planetary eccentricity in establishing the stationarity solution: higher secondary masses tend to sub-synchronous solutions while, as in the two-body case, high planetary eccentricity leads to super-synchronous solutions. This fact was previously observed in Zoppetti et al. (2019a) for low-eccentric systems.

|

Fig. 2 Stationary spin of a CB planet as a function of α. Different rows consider different eccentricity of the orbits (assumed equals). Different columns represent different reduced mass: |

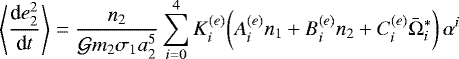

3.2 Secular evolution for the planetary semimajor axis and eccentricity

The variational equation for the planetary semimajor axis in the Jacobi frame is given by (Beutler 2005)

(14)

(14)

where δf2 is the total tidal force (per unit mass) affecting the two-body motion of the planet around the barycenter of the binary system. It is explicitly given by

![\begin{equation*} \delta {\bm f}_2 = \frac{1}{\beta_2}\bigg[ ({\bm F}_{2,0}-{\bm F}_{0,2})+({\bm F}_{2,1}-{\bm F}_{1,2}) \bigg], \end{equation*}](/articles/aa/full_html/2020/02/aa37248-19/aa37248-19-eq40.png) (15)

(15)

where β2 = m2σ1∕σ2 is the Jacobian reduced mass of the planet. We then repeat the procedure employed in Sect. 3.1, now in order to obtain averaged expressions for the orbital evolution which are in closed form with respect to the eccentricities. Up the fourth order in α and averaging over the mean longitudes, we obtain

(16)

(16)

and the coefficients  ,

,  , and

, and  , are listed in Appendix B. The variational equation for the semimajor axis depends on the spins through a new complex parameter given by

, are listed in Appendix B. The variational equation for the semimajor axis depends on the spins through a new complex parameter given by

(18)

(18)

Finally, the time evolution of the planetary eccentricity may be found from the orbital angular momentum

(19)

(19)

Differentiating over time and extracting the eccentricity term, we may write

![\begin{equation*} \frac{\textrm{d}}{\textrm{d}t} (e^2_2) = \frac{1}{a_2} \bigg[(1-e^2_2)\frac{\textrm{d}a_2}{\textrm{d}t} - \frac{2 L_2}{\mathcal{G}\sigma_2\beta_2} \bigg( ({\bm{\rho}}_2 \times \delta{\textbf{f}}_2) \cdot \hat{\textbf{z}}_2\bigg) \bigg],\end{equation*}](/articles/aa/full_html/2020/02/aa37248-19/aa37248-19-eq48.png) (20)

(20)

where  is the unit vector of the orbital angular momentum. Proceeding in the same manner that for Eq. (B.1), the rate of change of the planetary eccentricity can be approximated as:

is the unit vector of the orbital angular momentum. Proceeding in the same manner that for Eq. (B.1), the rate of change of the planetary eccentricity can be approximated as:

(21)

(21)

We note that both the tidal magnitude coefficient  and the spin functions

and the spin functions  are the same as deduced for the semimajor axis. The coefficients

are the same as deduced for the semimajor axis. The coefficients  ,

,  , and

, and  , are listed in Appendix B.

, are listed in Appendix B.

Figure 3 shows the derivative of the semimajor axis (left panels) and eccentricity (right panels), as a function of α, of a CBP orbiting our generic binary system. The spin rates of the stars and the planet were set in their stationary values:  (Hut 1980) and

(Hut 1980) and  (Eq. (13)). We observe that our closed fourth-order model is a very precise approximation of the numerical values up to α ~ 0.35. The need of an analytical model closed in eccentricities is again particularly evident in the high-eccentricity regime (bottom plots), where our previous model fails not only to estimate the magnitude but may also predict erroneous signs for the time derivative.

(Eq. (13)). We observe that our closed fourth-order model is a very precise approximation of the numerical values up to α ~ 0.35. The need of an analytical model closed in eccentricities is again particularly evident in the high-eccentricity regime (bottom plots), where our previous model fails not only to estimate the magnitude but may also predict erroneous signs for the time derivative.

Regarding the dynamical implications, we observe that tides always seem to decrease the planetary eccentricity, with magnitude proportionalto e2 and also to the proximity to the binary. The effect of tides on the planetary semimajor axis is more diverse: for low-to-moderate planetary eccentricities, the tidal forces leads to an outward migration, while inward migration is expected for the high-eccentricity case. These results confirm our previous findings (Zoppetti et al. 2019a) and a simple geometrical explanation is offered in Sect. 4.2.

|

Fig. 3 Time derivative of the planetary semimajor axis (left panels) and eccentricity (right panels), as a function of α, for a synchronised CB planet around our generic binary system. As before, results obtained with different models are shown in different colored curves: numerical in broad grey, Zoppetti et al. (2019a) in thin blue, and predictions from our current α4 model in black. |

4 Application to Kepler systems

Having developed a model valid for arbitrary binary and planetary eccentricities, we can analyse the tidal evolution of Kepler CB systems.

Table 1 lists the physical parameters (mass and radius) of the binaries and the planets discovered by the Kepler mission, as well as the semimajor axes and eccentricities of the binaries (sub-index 1) and the planets (sub-index 2). The last column specifies the reference works from which the previous values were taken. In several cases, the difficulties in determining the planetary mass has only allowed to establish an upper limit as defined by gravitational perturbation thresholds.

From Table 1, we can infer that most of the Kepler CBPs are in the Neptune to Jupiter range, with expected tidal values  (Ferraz-Mello 2013; Lainey 2016). For such planets, a CTL-model as the one adopted here should be a good approximation. On the other hand, there are some planets such as Kepler-47b and Kepler-47c that are probably closer to the super-earth range. In such systems, the direct application of our model may not be adequate (Efroimsky 2012, 2015).

(Ferraz-Mello 2013; Lainey 2016). For such planets, a CTL-model as the one adopted here should be a good approximation. On the other hand, there are some planets such as Kepler-47b and Kepler-47c that are probably closer to the super-earth range. In such systems, the direct application of our model may not be adequate (Efroimsky 2012, 2015).

Although we are considering stars with very different masses and different possible internal structure, in the following sections we will assume the same value of the tidal parameters:  .

.

4.1 Tidal timescales

In order to evaluate the importance of tidal evolution in these systems, we define characteristic timescales for the planetary spin evolution (τs), the semimajor axis evolution (τa) and eccentricity evolution (τe) according to:

(22)

(22)

In the case of the planetary spin, the simple form of Eq. (A.1) allow us to accurately estimate the characteristic timescales of a CBP due to tidal effects as

(23)

(23)

Results are presented in Table 2, were the first numerical value is the current semimajor axis ratio α of the CBP. The two following columns give the characteristic timescale necessary for the planet to reach a stationary spin (i.e. τs) and the corresponding equilibrium value  , expressed in units of its orbital frequency n2. The planetary moment of inertia was taken equal to

, expressed in units of its orbital frequency n2. The planetary moment of inertia was taken equal to  .

.

The values of τs were calculated adopting  so they should be scaled appropriately for other planetary tidal parameters. According to Eq. (23),

so they should be scaled appropriately for other planetary tidal parameters. According to Eq. (23),  , making it straightforward to relate both quantities. In agreement with the numerical experiments done for Kepler-38 by Zoppetti et al. (2019a), pseudo-synchronisation appears to be attained rapidly in most Kepler systems even for large value for

, making it straightforward to relate both quantities. In agreement with the numerical experiments done for Kepler-38 by Zoppetti et al. (2019a), pseudo-synchronisation appears to be attained rapidly in most Kepler systems even for large value for  . With the possible exception of Kepler-1647, we expect all Kepler CBP to currently lie in stationary spin-orbit configurations. As can be seen in the following column, all the stationary spins are expected to be sub-synchronous, some of them for a large amount (such as Kepler-35) and others almost in perfect synchronisation with its own mean motion (like Kepler-34).

. With the possible exception of Kepler-1647, we expect all Kepler CBP to currently lie in stationary spin-orbit configurations. As can be seen in the following column, all the stationary spins are expected to be sub-synchronous, some of them for a large amount (such as Kepler-35) and others almost in perfect synchronisation with its own mean motion (like Kepler-34).

The four last columns of Table 2 give the average time derivatives and characteristic timescales of the planetary semimajor axis and eccentricity. We assumed stationary values for Ω2 and current values for a2 and e2. Due to the complex functional dependence of the derivative with the initial conditions, the numerical values shown in the table should be considered local and not necessarily indicative of their primordial magnitudes. Even so, they give a qualitative idea of the strength of the tidal effects and, particularly, the sign of the present-day orbital variation.

For the observed orbital and physical parameters, our model predicts that all Kepler circumbinary planets should be migrating outwards as a consequence of their tidal interactions with the binary. However, the timescale necessary for a significantorbital migration is much larger than the age of the host star, even adopting very small values of  . Conversely, tidal evolution always seems to damp the planetary eccentricity, and the circularization process appears to occur in a slightly smaller timescale than the semimajor axis.

. Conversely, tidal evolution always seems to damp the planetary eccentricity, and the circularization process appears to occur in a slightly smaller timescale than the semimajor axis.

A final word on the case of Kepler-1647. Due to its large distance from the binary, as expressed by its small value of α, the characteristic timescales for tidal evolution are typically three orders of magnitude larger than in any other system. Even so however, it is still possible for the planet to be close to a spin-orbit stationary solution even for moderate-to-large values of  .

.

4.2 A geometrical interpretation for outward migration

The prediction that all Kepler CBPs should be experiencing outward migration from the tidal effect raises the question as to why this happens. Although a full explanation is beyond the scope of this paper, we can present a simple geometrical interpretation that may give some insight.

We consider the case in which the binary and the planetary orbit are circular, e1 = e2 = 0. In addition, weassume that the planet is sufficiently far from the binary to neglect all terms in Eq. (16) explicitly dependent on α. In this approximation, the stationary spins are trivial and equal to the mean motion:  and

and  . From expression in Appendix B, we find that the time derivative of the planetary semimajor axis acquires the simple form:

. From expression in Appendix B, we find that the time derivative of the planetary semimajor axis acquires the simple form:

![\begin{equation*} \frac{1}{a_2} \left<\frac{\textrm{d}a_2}{\textrm{d}t}\right> = \frac{6 n_2 \, m_2}{m_0+m_1} \bigg[ k_{2,0}\Delta t_0 \bigg(\frac{\mathcal{R}_0}{a_2}\bigg)^5 + k_{2,1}\Delta t_1 \bigg(\frac{\mathcal{R}_1}{a_2}\bigg)^5 \bigg] (n_1-n_2).\end{equation*}](/articles/aa/full_html/2020/02/aa37248-19/aa37248-19-eq71.png) (24)

(24)

We can compare this expression with that obtained in the two-body problem for a point-mass planets of mass m2 in a circular orbit around a star m0 rotating with arbitrary spin Ω0. In such a case, the semimajor axis of the planet evolves according to

![\begin{equation*} \frac{1}{a_2}\frac{\textrm{d}a_2}{\textrm{d}t} = \frac{6 n_2 m_2}{m_0} \bigg[ k_{2,0}\Delta t_0 \bigg( \frac{\mathcal{R}_0}{a_2}\bigg)^5 \bigg] \, (\Omega_0-n_2),\end{equation*}](/articles/aa/full_html/2020/02/aa37248-19/aa37248-19-eq72.png) (25)

(25)

as can be seen, for example, in Hut (1980). The similarity between these two equations helps explain why CBPs with low-to-moderate eccentricities migrate outwards. In the circumbinary geometry, the tidal effect of the binary star system may be substituted by a single body with a rotational frequency equal to the binary mean motion n1. Since this quantity is always greater than the mean motion of the planet n2, the semimajor axis of the planet increases. This situation is analogous to the two-body problem in which the central star m0 rotates faster than orbital motion of the planet.

Physical and orbital parameters of Kepler circumbinary systems.

Tidal stationary spin rates and characteristic timescales (assuming  ) for Kepler circumbinary systems.

) for Kepler circumbinary systems.

4.3 Past tidal evolution

Our next step is to attempt to reconstruct the past tidal evolution of the Kepler CB systems, as well as estimate their future trends. We assume that all bodies (stars and planet) are in stationary spin-orbit configurations and analyse only the changes in semimajor axis and eccentricity. Since the mass or radius of some of the planets are not well constrained,we completed the necessary physical parameters with the empirical mass-radius relation defined by Mills & Mazeh (2017).

Figure 4 shows, for each Kepler CBP, the tidal evolution velocity field around the current location of the planet in the (α, e2) plane. The velocity field was computed assuming stationary spins for all intervening bodies and disregardingthe tidal evolution of the binary stars. The arrows represent the direction of orbital evolution in α and e2, and its size was kept constant.

The green curves show initial conditions with  . All points on the plane above display inward migration (da2∕dt < 0) while those below the curve lead to outward tidal migration. Kepler-34 shows a second green curve for large values of α that is also observed for some of the other systems for even higher values of α (which lie outside of the range adopted in the panels of Fig. 4). However, above such a curve, our model predicts an increase in the eccentricity of the synchronised CBP. We suspect that this may be a spurious effect consequence of the truncation to fourth-order in the semimajor axis ratio when estimating the stationary CBP spin Eq. (13).

. All points on the plane above display inward migration (da2∕dt < 0) while those below the curve lead to outward tidal migration. Kepler-34 shows a second green curve for large values of α that is also observed for some of the other systems for even higher values of α (which lie outside of the range adopted in the panels of Fig. 4). However, above such a curve, our model predicts an increase in the eccentricity of the synchronised CBP. We suspect that this may be a spurious effect consequence of the truncation to fourth-order in the semimajor axis ratio when estimating the stationary CBP spin Eq. (13).

The magenta curves show the capture eccentricity e2,cap as function of α for each system. Its value is given by the mean-square average between the forced eccentricity (Moriwaki & Nakagawa 2004) and the mean eccentricity calculated for zero-amplitude secular variations (Paardekooper et al. 2012). Explicitly,

(26)

(26)

where the classical forced eccentricity is given by

(27)

(27)

while the mean eccentricity takes the form

(28)

(28)

More details of the calculations leading to these values may be found in Zoppetti et al. (2019b). This so-called capture eccentricity defines the average value expected as the result of non-conservative exterior forces acting on the system.

Finally, initial conditions inside the pink region are dynamically unstable according to the empirical criterion of Holman & Wiegert (1999). Note however, that this criterion is only valid for small-mass planets and circular orbits, so their extent should be considered more qualitative than accurate.

Analysing the velocity vector fields, we first note that the eccentricity usually appears more affected than the semimajor axis, except for quasi-circular orbits where the opposite occurs. When the gravitational perturbations are includedin the model, it is possible to observe that the orbital evolution of the system follows the locus of e2,cap as function of α, as observed in Zoppetti et al. (2018) for Kepler-38.

In some systems we also observe that the domain associated to outward migration can reach high eccentricities (e.g. Kepler-35, Kepler-413, and Kepler-1647) while in others it is restricted to more circular trajectories (e.g. Kepler-16, Kepler-38, and Kepler-64). An explanation for such dichotomy may be found in Zoppetti et al. (2019a), where we found that in the low-eccentric systems, the size of the outward migrating-CB-region is directly proportional to the reduced mass  and inversely proportional to e2. It is straightforward to check from Table 1 that Kepler-35, Kepler-413 and Kepler-1647 satisfy quite these conditions while, for example, in the rest of the systems the value of

and inversely proportional to e2. It is straightforward to check from Table 1 that Kepler-35, Kepler-413 and Kepler-1647 satisfy quite these conditions while, for example, in the rest of the systems the value of  is significantly lower.

is significantly lower.

The proximity of the observed Kepler circumbinary planets to the stability limit with the binary has been the subject of several recent studies (e.g. Quarles et al. 2018). While it has been proposed that this pile-up is unlikely to be affected by observational bias (Li et al. 2016), the recent discovery of a third and outer planet in Kepler-47 (Orosz et al. 2019) may indicate that we are only detecting the tail of the distribution. Nevertheless, we still need to address the current population and its past orbital evolution.

A key aspect of this question is the tidal evolution of the binary system and, particularly, what were the primordial orbital separation and eccentricity of the binary at the time of the planet’s formation and migration. In Zoppetti et al. (2018) we showed that even for moderate values of the stellar tidal parameters the original binary eccentricity could have ben much larger, thereby pushing the instability barrier closer to the planet. Similar results were also found for Kepler-34. An outward tidal migration of the planet itself would have worked in the same direction leading to a potentially more unstable primordial configuration.

These results could be interpreted as evidence that the orginal location of the CBPs was closely tied to the instability barried, perhaps in the form of sub-dense inner gaps in the protoplanetary disks. If so, then planetary traps such as those proposed by Kley & Haghighipour (2014) and Thun & Kley (2018) would be a more probable stalling mechanism for planetary migration than resonance capture.

Additionally, it is interesting to note that most of the CBPs located tightly packed to the binaries have eccentricities also very close to the capture eccentricity e2,cap, with the exceptions of Kepler-34 and Kepler-413. Recently, Thun & Kley (2018) suggested that low-mass CBPs are strongly influenced by the protoplanetary disc and their eccentricities may have been very excited during the migration process. If this hypothesis is confirmed, then another non-conservative effect must be invoked to explain their current state. Tidal interactions appears as a possibility, even if they would need to be extremely accentuated. Curiously, Kepler-35 and Kepler-38, two systems with e2 ~ e2,cap belong to very old systems with estimated ages of the order of ~10 Gyrs (Welsh et al. 2012; Orosz et al. 2012a). Perhaps accumulated tidal effects over such a long time could be at least partially responsible, and could help in constraining the magnitudes of tidal parameters for both stars and planets.

|

Fig. 4 Velocity vector fields in the (α, e2) plane depicting the routes of tidal evolution in the vicinity of each Kepler CBP. The arrows show the direction of orbital evolution throughout the plane, although its size was kept constant and is thus not representative of the magnitude of the derivatives. The green curves corresponds to

|

5 Summary and discussion

We presented an extended version of the analytical tidal model for CB systems introduced in Zoppetti et al. (2019a). Once again, we assumed that all the bodies are extended and viscous in such a way that all interactions between pairs are considered but under the weak-friction regime, in which the tidal forces can be approximated by the classical expressions of Mignard (1979).

Startingfrom the variational equations of the spin and orbital evolution of the planet, we constructed an analytical approach by averaging over the mean longitudes. In all the cases, we expanded up to fourth-order in the semimajor axes ratio α but obtained closed expressions in the binary and planetary eccentricities. The resulting analytical model was compared with the results of numerical simulations and a very good agreement was found for all eccentricities and semimajor axes ratios up to α ~0.35.

Having expressions closed in eccentricities allowed us to apply the model to all well known Kepler CBPs. We investigated their past tidal evolution in two steps. First, we calculated the characteristic tidal timescales and found that the typical time required for a CBP to acquire its stationary spin is typically much lower than the expected age of the host star, even for moderate-to-large values of Q′. Consequently, most of the observed system should lie in spin-orbital stationary solutions with a sub-synchronous rotational frequency. Regarding the orbital evolution we found that the typical tidal timescales in the Kepler systems are much longer than the rotational timescales, and little tidal induced orbital migration is expected to have occurred. The eccentricity damping timescales, however, are one or two orders of magnitude lower than τa and tidal interactions could have caused some decrease in the eccentricities during the systems’ age.

In a second part of the work, we obtained some insight on the past tidal histories studying the tidal velocity fields around each planet. We found that all bodies are located in a tidal stream associated to an outward migration, pushing the planet away from the binary. Furthermore, with the exception of Kepler-34, all other systems are located distant from the curve separating inward and outward migrations. This seems to indicate that most or all of the systems lifetime was spent inside the region of outward migration. Consequently, their primordial separation from the binary should have been smaller.

Thun & Kley (2018) recently suggested that low-mass CBPs may have suffered strong excitation from the protoplanetary disk, leading to a highly eccentric final orbit. This contrasts with the current values which, in most cases, are found very close to the capture eccentricity. Perhaps tidal evolution played some role in damping the primordial value, which would help define some constraints on the numerical values of the tidal parameters of the system.

We mention, finally, that most of the CBPs discovered so far by the Kepler mission are in the range of Neptune to Jupiter masses, where CTL-models for tides should be valid. However, we note that not much is known about the internal structure of this bodies and therefore a precise estimation of the  -values becomes a difficult task.

-values becomes a difficult task.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to M. Efroimsky for the helpful comments and suggestions. This research was funded by CONICET, SECYT/UNC, and FONCYT.

Appendix A Coefficients for the spin equations

The variational equation for the planetary spin, up to fourth order in α, was given in Eq. (10), which is repeated here for convenience:

The  coefficients, multiplying the mean motion n1 of the binary, acquire the form

coefficients, multiplying the mean motion n1 of the binary, acquire the form

(A.1)

(A.1)

in terms of eccentricity functions Yi(e1) and Xi(e2) which are explicitly given in Appendix C. The coefficients that multiply the mean motion of the planet are found to be

(A.2)

(A.2)

Finally, the coefficients accompanying the planetary spin rate are

(A.3)

(A.3)

We note that all coefficients are function of the eccentricities, while some are also dependent on the difference in the longitudes of pericenter.

Recalling Eq. (13), the stationary spin rate predicted by our model may be written as

The different order terms  are given by

are given by

(A.4)

(A.4)

where, for the sake of simplicity, we have defined new auxiliary functions

![\[ D_i^{(s)} = A_i^{(s)} n_1 + B_i^{(s)} n_2. \]](/articles/aa/full_html/2020/02/aa37248-19/aa37248-19-eq88.png)

Appendix B Coefficients for the tidal evolution of the semimajor axis and eccentricity

As seen in Eq. (16), the time derivative of the planetary semimajor axis may be writen as

where the definitions of  and

and  were explicitly given in Eqs. (17) and (18). The coefficients are:

were explicitly given in Eqs. (17) and (18). The coefficients are:

![\begin{eqnarray*} A^{(a)}_0 &=& 0, \nonumber \\ A^{(a)}_1 &=& 0, \nonumber \\ A^{(a)}_2 &=& \frac{10 \sqrt{1-e_1^2}}{{(1-e_2^2)}^{8}} X_5, \nonumber \\ A^{(a)}_3 &=& \frac{400 \sqrt{1-e_1^2}}{{(1-e_2^2)}^{9}} X_{8} e_1 e_2 \cos(\Delta \varpi), \\[1pt] A^{(a)}_4 &=& \frac{25 \sqrt{1-e_1^2}}{8 {(1-e_2^2)}^{10}} \left( 32 Y_1 X_{11} + 9 \left( 120 X_{12} -184 e_1^2 X_{21} + 127 e_1^4 X_{22} \right)\right.\nonumber\\[1pt] &&\left.\cdot\, \frac{e_1^2 e_2^2 \cos(2 \Delta \varpi)}{{(1-e_1^2)}^{2}}\right). \nonumber \end{eqnarray*}](/articles/aa/full_html/2020/02/aa37248-19/aa37248-19-eq92.png) (B.1)

(B.1)

(B.2)

(B.2)

(B.3)

(B.3)

In the same manner, the planetary eccentricity evolution up to fourth order in α is given by

where  and the coefficients are listed below:

and the coefficients are listed below:

(B.4)

(B.4)

(B.5)

(B.5)

(B.6)

(B.6)

Appendix C Eccentricity functions

The eccentricity functions Yi(e1) and Xi(e2) to which we refer in the previous equations are found to be combinations of the Hansen coefficients. Explictly, the first are found to be:

(C.1)

(C.1)

while the functions of the planetary eccentricity are given in Table C.1:

Planetary eccentricity functions.

References

- Beutler, G. 2005, Methods of Celestial Mechanics (Berlin: Springer), I [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Demircan, O., & Kahraman, G. 1991, Ap&SS, 181, 313 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, L. R., Carter, J. A., Fabrycky, D. C., et al. 2011, Science, 333, 1602 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [MathSciNet] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunhill, A. C., & Alexander, R. D. 2013, MNRAS, 435, 2328 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Efroimsky, M. 2012, ApJ, 746, 150 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Efroimsky, M. 2015, AJ, 150, 98 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraz-Mello, S. 2013, Celest. Mech. Dyn. Astron., 116, 109 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraz-Mello, S., Rodríguez, A., & Hussmann, H. 2008, Celest. Mech. Dyn. Astron., 101, 171 [Google Scholar]

- Holman, M. J., & Wiegert, P. A. 1999, AJ, 117, 621 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hut, P. 1980, A&A, 92, 167 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Kley, W., & Haghighipour, N. 2014, A&A, 564, A72 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Kostov, V. B., McCullough, P. R., Carter, J. A., et al. 2014, ApJ, 784, 14 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kostov, V. B., Orosz, J. A., Welsh, W. F., et al. 2016, ApJ, 827, 86 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lainey, V. 2016, Celest. Mech. Dyn. Astron., 126, 145 [Google Scholar]

- Li, G., Holman, M. J., & Tao, M. 2016, ApJ, 831, 96 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lines, S., Leinhardt, Z. M., Paardekooper, S., Baruteau, C., & Thebault, P. 2014, ApJ, 782, L11 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mignard, F. 1979, Moon Planets, 20, 301 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mignard, F. 1980, Moon Planets, 23, 185 [Google Scholar]

- Mills, S. M., & Mazeh, T. 2017, ApJ, 839, L8 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Moriwaki, K., & Nakagawa, Y. 2004, ApJ, 609, 1065 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Orosz, J. A., Welsh, W. F., Carter, J. A., et al. 2012a, ApJ, 758, 87 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Orosz, J. A., Welsh, W. F., Carter, J. A., et al. 2012b, Science, 337, 1511 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orosz, J. A., Welsh, W. F., Haghighipour, N., et al. 2019, AJ, 157, 174 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Paardekooper, S.-J., Leinhardt, Z. M., Thébault, P., & Baruteau, C. 2012, ApJ, 754, L16 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Quarles, B., Satyal, S., Kostov, V., et al. 2018, ApJ, 856, 150 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schwamb, M. E., Orosz, J. A., Carter, J. A., et al. 2013, ApJ, 768, 127 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Thun, D., & Kley, W. 2018, A&A, 616, A47 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh, W. F., Orosz, J. A., Carter, J. A., et al. 2012, Nature, 481, 475 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh, W. F., Orosz, J. A., Short, D. R., et al. 2015, ApJ, 809, 26 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zoppetti, F. A., Beaugé, C., & Leiva, A. M. 2018, MNRAS, 477, 5301 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zoppetti, F. A., Beaugé, C., Leiva, A. M., et al. 2019a, A&A, 627, A109 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Zoppetti, F. A., Beaugé, C., & Leiva, A. M. 2019b, J. Phys. Conf. Ser., 1365, 012029 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

All Tables

Tidal stationary spin rates and characteristic timescales (assuming  ) for Kepler circumbinary systems.

) for Kepler circumbinary systems.

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Time derivative of the planetary spin rate Ω2 in our generic binary system as a function of α = a1∕a2. Each panelassumes different eccentricities for both orbits. Broad gray curves show results from semi-analytical calculationsand predictions from analytical models are depicted in thin lines. Values obtained with our original (Zoppetti et al. 2019a) are presented in blue, while the colors correspond to our current model with different orders in α. See inlaid box in left-hand plot for details. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Stationary spin of a CB planet as a function of α. Different rows consider different eccentricity of the orbits (assumed equals). Different columns represent different reduced mass: |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 Time derivative of the planetary semimajor axis (left panels) and eccentricity (right panels), as a function of α, for a synchronised CB planet around our generic binary system. As before, results obtained with different models are shown in different colored curves: numerical in broad grey, Zoppetti et al. (2019a) in thin blue, and predictions from our current α4 model in black. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4 Velocity vector fields in the (α, e2) plane depicting the routes of tidal evolution in the vicinity of each Kepler CBP. The arrows show the direction of orbital evolution throughout the plane, although its size was kept constant and is thus not representative of the magnitude of the derivatives. The green curves corresponds to

|

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.