| Issue |

A&A

Volume 584, December 2015

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A90 | |

| Number of page(s) | 19 | |

| Section | Extragalactic astronomy | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201526677 | |

| Published online | 26 November 2015 | |

MUSE tells the story of NGC 4371: The dawning of secular evolution

1 European Southern Observatory, Casilla 19001, Santiago 19, Chile

e-mail: dgadotti@eso.org

2 Instituto de Astrofísica de Canárias, 38200 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain

3 Departamento de Astrofísica, Universidad de La Laguna (ULL), 38206 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain

4 Departamento de Física Teórica, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, 28049 Cantoblanco, Spain

5 European Southern Observatory, Karl-Schwarzschild-Str. 2, 85748 Garching b. Muenchen, Germany

6 Instituto Astronômico e Geofísico, Universidade de São Paulo, Rua do Matão, 1226, 05508-090 São Paulo, SP, Brazil

7 Departamento de Física Teórica y del Cosmos, Universidad de Granada, Facultad de Ciencias (Edificio Mecenas), 18071 Granada, Spain

8 Instituto Universitario Carlos I de Física Teórica y Computacional, Universidad de Granada, 18071 Granada, Spain

Received: 4 June 2015

Accepted: 24 August 2015

We use data from the Multi-Unit Spectroscopic Explorer (MUSE), recently commissioned at the Very Large Telescope (VLT), to study the kinematics and stellar population content of NGC 4371, an early-type massive barred galaxy in the core of the Virgo cluster. We integrate this study with a detailed structural analysis using imaging data from the Hubble and Spitzer Space Telescopes, which allows us to perform a thorough investigation of the physical properties of the galaxy. We show that the rotationally supported inner components in NGC 4371, i.e. an inner disc and a nuclear ring – which, according to the predominant scenario, are built with stars formed from gas brought to the inner region by the bar – are vastly dominated by stars older than 10 Gyr. Our results thus indicate that the formation of the bar occurred at a redshift of about  (error bars are derived from 100 Monte Carlo realisations). NGC 4371 thus testifies to the robustness of bars. In addition, the mean stellar age of the portion of the major disc of the galaxy that is covered by our MUSE data is above 7 Gyr with a small contribution from younger stars. This suggests that the quenching of star formation in NGC 4371, which is very likely an environmental effect, was already occurring at a redshift of about

(error bars are derived from 100 Monte Carlo realisations). NGC 4371 thus testifies to the robustness of bars. In addition, the mean stellar age of the portion of the major disc of the galaxy that is covered by our MUSE data is above 7 Gyr with a small contribution from younger stars. This suggests that the quenching of star formation in NGC 4371, which is very likely an environmental effect, was already occurring at a redshift of about  . Our results suggest that bar-driven secular evolution processes may have an extended impact on the evolution of galaxies, and thus on the properties of galaxies as observed today, and not necessarily be restricted to more recent cosmic epochs.

. Our results suggest that bar-driven secular evolution processes may have an extended impact on the evolution of galaxies, and thus on the properties of galaxies as observed today, and not necessarily be restricted to more recent cosmic epochs.

Key words: galaxies: bulges / galaxies: evolution / galaxies: formation / galaxies: kinematics and dynamics / galaxies: structure / galaxies: stellar content

© ESO, 2015

1. Introduction

Evolved disc galaxies are characterised by an extended outer disc, dynamically supported by the rotation of its stars around the galaxy centre. These discs often present non-axisymmetric structures such as spiral arms or bars. The inner region of disc galaxies can contain a number of other components, e.g. a dynamically hotter spheroid, or disc-like structures, such as inner discs and nuclear rings1. Current scenarios attribute external and violent formation processes to the former, e.g. mergers, whereas inner disc-like structures are believed to have formed by internal and less disturbing processes. These processes are due to the impact of the non-axisymmetric components, particularly bars, on the otherwise axisymmetric potential of the disc. Those merger-built spheroids are sometimes named classical bulges, while the internal processes driven by non-axisymmetric components are sometimes labelled as part of secular evolution (see e.g. Binney & Merrifield 1998; Elmegreen 1998; Athanassoula 2013; Kormendy 2013; Sellwood 2014). Secular evolution is expected to be the dominant set of processes in galaxy evolution after the peak of star formation activity that occurs between redshifts 1 and 2 or between about 8 and 10 Gyr ago. Before and during this intense period in cosmic history, interactions between galaxies are believed to have been the dominant process through which galaxies evolved. After this, in broad terms, a less agitated period began for galaxies outside dense environments, such as clusters or groups, when internal secular evolution processes became important, particularly those driven by bars formed in galaxy discs.

One of the most important consequences of secular evolution is the inflow of gas through the bar to the central regions of galaxies, which results in the building of inner stellar components, a process seen in both theoretical and observational work (see e.g. Combes & Gerin 1985; Athanassoula 1992b, 2005; Sellwood & Wilkinson 1993; Piner et al. 1995; Sakamoto et al. 1999; Rautiainen & Salo 2000; Regan & Teuben 2003, 2004; Sheth et al. 2005; Wozniak 2007; Knapen 2007; Gadotti 2009; Kim et al. 2012; Cole et al. 2014; Emsellem et al. 2015; Sormani et al. 2015, and references therein). The inflow of gas may trigger inner discs and/or nuclear rings comprised of recently formed stars, at or near the inner Lindblad resonance (ILR) associated with the bar or rather at the region dominated by the bar × 2 orbits. A number of studies have found nuclear rings associated with bars (from the pioneering works of Sérsic & Pastoriza 1965, 1967 to e.g. van den Bosch & Emsellem 1998; Falcón-Barroso et al. 2006; Sarzi et al. 2006; Kuntschner et al. 2010; Peletier et al. 2012; see also Buta & Combes 1996 and Maoz et al. 2001), and many of those rings show intense star formation activity when cold gas is available. Other rings just evolve passively if most of the funnelled gas has been transformed into stars and there is no additional fuel for more star formation. Recent studies show that both the current and past star formation activity at the centres of barred galaxies are enhanced when compared to unbarred galaxies (see e.g. Ellison et al. 2011; Coelho & Gadotti 2011), although not all barred galaxies conform to this picture2.

Because these inner components are built from material brought from the disc (which is already dynamically and structurally mature enough to develop a bar), as such they are expected to show exponential, or nearly exponential, light profiles. To differentiate these inner structures from the classical concept of bulges residing in the centres of disc galaxies, a new nomenclature has been developed, leading to terms such as pseudobulges, disc-like bulges, or discy pseudobulges (Kormendy & Kennicutt 2004; Athanassoula 2005; Drory & Fisher 2007; Fisher & Drory 2010; Gadotti 2012; Cheung et al. 2013; see also Kormendy & Barentine 2010; Méndez-Abreu et al. 2014 and Erwin et al. 2015, for studies of the coexistence of different inner structures in a single galaxy). Much work on these inner, secularly-built components and their relation to classical, merger-built bulges is still going on, and in particular on their place in a hierarchical galaxy-formation scenario (see Kormendy 2015; Sanchez-Blazquez 2015; Bournaud 2015; Falcón-Barroso 2015, and references therein).

Placing secular evolution in the hierarchical paradigm of galaxy formation is thus an important topic of research in extragalactic astrophysics today. Since bars are the major drivers of internal secular evolution (and are common in the local universe, see e.g. Eskridge et al. 2000; Menéndez-Delmestre et al. 2007; Masters et al. 2011), a major step forward would be to set the epoch in the evolution of the universe in which bars first ignited secular evolution processes. Ideally, we would like to be able to state for how long the bar in a given barred galaxy influences its host’s evolution. The age of the stellar population in a bar is not necessarily a measure of the age of the bar. A young bar, i.e. one that has been recently formed, could very well be composed of old stars. Because of this, different approaches have to be developed to address this problem. Given these difficulties, progress has been slow from an observational viewpoint (see e.g. Gadotti & de Souza 2005, 2006; Pérez et al. 2007, 2009; Sánchez-Blázquez et al. 2011; Seidel et al. 2015). However, modern simulations at least indicate that bars, once formed, are difficult to dissolve (in the absence of major mergers), unless the disc is extremely gas-rich (Athanassoula et al. 2005; Bournaud et al. 2005; Berentzen et al. 2007; Kraljic et al. 2012).

From a statistical viewpoint, a powerful way to investigate the onset of bar-driven secular evolution is to study how the fraction of barred galaxies evolves with redshift. After the pioneering work by Abraham et al. (1999), most of the latest studies have used images from the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS), onboard the Hubble Space Telescope (HST). These were taken with filters such as the F814W and F850LP, which correspond to I and z, respectively, meaning that they are as red as possible but are still within the optical spectrum (see Jogee et al. 2004; Sheth et al. 2008; Cameron et al. 2010; Melvin et al. 2014). While the results are not entirely compatible between the different studies, there seems to be a consensus of opinion that the fraction of disc galaxies with bars declines rapidly and monotonically from the local universe to z ~ 0.8. Sheth et al. (2012) suggest that this is due to an evolution in the dynamical state of discs. With time, discs grow massive enough and kinematically cold enough to develop bars. As alerted by Sheth et al. (2008), one major difficulty in studying the fraction of barred galaxies at z ≳ 0.8 with the red ACS filters is that they correspond to rest-frame wavelengths in the ultraviolet part of the spectrum, where bars become exceedingly difficult to detect (see Gil de Paz et al. 2007). To avoid this problem, Simmons et al. (2014) used images taken with the infrared channel of the HST WFC3 (Wide Field Camera 3) with filters such as the F160W, allowing them to investigate the fraction of barred galaxies at z > 1. Consistent with previous results, they have found that the fraction of barred galaxies drops to z ~ 1, but then stays approximately constant at about ten per cent up to z ~ 2. The images used by Simmons et al. are from the Cosmic Assembly Near-Infrared Deep Extragalactic Legacy Survey (CANDELS; Grogin et al. 2011; Koekemoer et al. 2011). These works indicate that, statistically, bar-driven secular evolution became important at z < 1. But the work of Simmons et al. also suggests that for a number of galaxies, these processes started earlier.

To understand the formation and evolution of galaxies, it is also necessary to understand when galaxies form stars and when galaxies cease star-formation activities. While there are difficulties in understanding how galaxies in the field stop forming stars (see e.g. Martig et al. 2009), in dense galaxy environments, such as galaxy clusters, the removal of cold gas from galaxies and their surroundings is expected to be efficient in quenching star formation (see Balogh et al. 2004). The formation of galaxy clusters is a long process that has initial phases at redshifts higher than about 3, and although massive clusters have been observed at redshifts about unity or more (Brodwin et al. 2010, 2013; Propris et al. 2015; Ma et al. 2015), it is expected that cluster formation is a process that goes on well below z ≈ 1 (Kravtsov & Borgani 2012; Planelles et al. 2014). In fact, the nearby Virgo cluster is known for not yet being dynamically fully relaxed (Binggeli 1999). We thus expect the effects of the cluster environment on the evolution of its constituent galaxies to evolve with time.

In this paper, we explore the capabilities of the recently commissioned MUSE (the Multi-Unit Spectroscopic Explorer, Bacon et al. 2010) integral field spectrograph, installed on the ESO Very Large Telescope (VLT), atop Cerro Paranal, Chile. MUSE is unique in its combination of field size, sensitivity, spatial resolution, wavelength range, and spectral resolution. We use MUSE to study the inner 1′ squared of the nearby galaxy NGC 4371. We use imaging data from the Spitzer and Hubble space telescopes and, with MUSE, we are able to study in fine detail the inner components of the galaxy and put constraints to their formation histories.

In the next section, we briefly describe the MUSE observations and the corresponding data reduction. In Sect. 3, we provide a general description of NGC 4371 and its environment. In Sect. 4 we perform a detailed study of its structural properties, using images at 3.6 μm from the Spitzer Survey of Stellar Structures in Galaxies (S4G, Sheth et al. 2010) and HST images with their exquisite image quality. This structural analysis will prove fundamental in our understanding of the information extracted using MUSE. The extraction and analysis of kinematical information from the MUSE data cube is described in Sect. 5, while in Sect. 6 we describe our study on the ages and metallicities of stars in the MUSE field. In Sect. 7 we discuss our results in the context of bar-driven secular evolution and environmental effects in galaxy clusters. Finally, Sect. 8 summarises our main conclusions. Throughout this study we use a Hubble constant of H0 = 67.8 km s-1 kpc-1 and Ωm = 0.308 in a universe with flat topology (Planck Collaboration XIII 2015).

2. Observations and data reduction

|

Fig. 1 Top: reduced S4G mosaic of NGC 4371 displayed using histogram equalisation in order to highlight faint features. The inner red box represents the MUSE field of our exposures, with 1′ on a side. This image suggests the presence of a very faint polar ring that could have originated in an encounter with a satellite galaxy, but the evidence for it is weak at best. No sign of a violent recent interaction is seen. Middle: SDSS colour composite of NGC 4371, 6.6′ on its longer side. Bottom left: central region of the S4G image with isophotal contours overlaid in red and a diagram overlaid in black representing our MUSE exposures. The MUSE field is the inner trapezoid; the outer polygon area is used to acquire point sources for the slow guiding system. The bar is clearly seen. Bottom right: image obtained via unsharp masking of the S4G image, showing clearly the ring near the centre of NGC 4371. This ring has a semi-major axis of ≈10.4′′ and a semi-minor axis of ≈4.3′′. It has a width of about 2′′ and is delineated by the black ellipse. North is up, east is to the left in all panels. |

NGC 4371 was observed as a science verification (SV) programme (60.A-9313(A), PI: D. A. Gadotti) for MUSE during the nights of 25 and 29 June 2014. MUSE covers an almost square 1′ × 1′ field of view with a contiguous sampling of 0.2′′ × 0.2′′, which corresponds to a massive dataset of about 90 000 spectra per pointing. A spectral coverage from 4750 Å to 9300 Å is achieved in the normal instrument setup at a spectral resolution of ~2.5 Å. The observations were performed under a seeing with full width at half maximum (FWHM) varying from 0.8′′ to 0.9′′. The sky was affected by thin cirrus the first night and was of photometric quality during the second night. Since we do not aim at using information sensitive to the flux calibration of the data, any uncertainty resulting from the thin cirrus on the first night is irrelevant here. Nevertheless, the presence of thin cirrus may limit the accuracy of the background subtraction.

We targetted the central ~1′ × 1′ region of NGC 4371 with MUSE (see Fig. 1). The observations were distributed in two 1 h observing blocks with a total integration time of 1 h on source. Because the galaxy fills the MUSE field, we split the exposures per observing block into three exposures of 600 s and monitored the sky background by observing a blank sky field for 180 s following a SKY-OBJ-SKY-OBJ-OBJ-SKY pattern. To be able to reduce the effects of bad pixels and flat-fielding uncertainties, we applied a small dither (<1′′) of the field centre and rotated the entire MUSE field by 90 between each object observation. Frames were taken to correct the exposures for bias and dark current, to flat-field the exposures, and to perform illumination correction. Wavelength calibration is achieved through a set of different arc lamp frames, and the exposures were flux-calibrated through the observation of a spectrophotometric standard star. Finally, the exposures were also finely registered astrometrically. All these frames were observed as part of the MUSE standard calibration plan, and we applied the calibration frames taken closest in time to the execution of our observing blocks.

between each object observation. Frames were taken to correct the exposures for bias and dark current, to flat-field the exposures, and to perform illumination correction. Wavelength calibration is achieved through a set of different arc lamp frames, and the exposures were flux-calibrated through the observation of a spectrophotometric standard star. Finally, the exposures were also finely registered astrometrically. All these frames were observed as part of the MUSE standard calibration plan, and we applied the calibration frames taken closest in time to the execution of our observing blocks.

The MUSE pipeline (version 0.18.2) was used to reduce the dataset. A detailed description of the pipeline will be presented in Weilbacher et al. (in prep.), but we briefly outline the reduction process here. The process is split up into two steps. In the first one, each science frame is calibrated separately to take out instrumental effects. This consists of subtracting the bias and dark-current levels, flat-fielding the images (including illumination correction), extracting the spectra from all slices, and performing the wavelength calibration. The calibrated science frames are combined into the final data cube in the second step. This includes the process of flux calibration, sky subtraction adopting a model sky spectrum computed from the sky field, astrometric registration, correction for differential atmospheric refraction, and resampling of the data cube based on the drizzle algorithm (see Weilbacher et al. 2012).

3. Introducing NGC 4371: general properties and environment

|

Fig. 2 Top: sky map covering the Virgo cluster. The positions of NGC 4371 and M 87 are highlighted, as well as an area of 16 sq. deg around the centre of the cluster. Bottom: expanded view of the 16 sq. deg box highlighted in the top panel. At the distance of the cluster, NGC 4371 is about 0.4 Mpc away from M 87, which sits near the bottom of the cluster’s potential well. (Adapted with permission from the Deep Sky Hunter Star Atlas; see http://www.deepskywatch.com/ – courtesy of Michael Vlasov.) |

NGC 4371 is an early-type galaxy that is in the core of the Virgo cluster. It is thus nearby (d ≈ 16.9 Mpc, Blakeslee et al. 2009), bright (MB ≈ −19.2, see HyperLeda3; MAB,F850LP ≈ −21.2, Ferrarese et al. 2006), massive (M⋆ ≈ 1010.8M⊙, Gallo et al. 2010), and classified as a barred S0 (lenticular) galaxy (Buta et al. 2015). Buta et al. also mention that NGC 4371 has a nuclear ring, a barlens, an inner ring (i.e. with a radius close to the bar’s semi-major axis), as well as ansae at the bar ends and an outer lens (see Fig. 1). Ansae are stellar density enhancements often found in barred galaxies that look like bar handles (see Martinez-Valpuesta et al. 2007, for a recent study on ansae).

Barlenses have only recently been identified as an independent morphological feature. They are believed to be the face-on projection of box/peanuts (Laurikainen et al. 2014; Athanassoula et al. 2014; Athanassoula 2015; see also Fig. 8 in Gonzalez & Gadotti 2015). In this case then, barlenses are just the inner parts of bars that are more extended than the outer parts in the vertical direction, as well as along the bar minor axis in the disc plane. As we see below, our spectroscopic analyses do not reach far enough from the galaxy centre to include the outer lens, the ansae, and the inner ring mentioned by Buta et al. (2015). Therefore, these components are not addressed here. Our MUSE field covers, however, part of the main disc, the bar, the nuclear ring, and other inner components discussed in detail below, which hold important clues as to the formation and evolution history of the galaxy.

The top panel of Fig. 1 shows the S4G mosaic at an image stretch that highlights the faintest components of the galaxy. The sensitivity of this image is approximately (1σ) 27 AB mag arcsec-2, or about 1 M⊙ pc-2 and yet there is no evidence of any recent violent interaction. On the other hand, it may suggest the presence of a very faint polar ring that could have originated from the encounter with a satellite galaxy. It therefore seems reasonable to assume that no dramatic merger has occurred recently in the galaxy. The SDSS colour composite in the middle panel clearly shows how uniform the optical colour distribution is across the galaxy, with no signs of recent star formation. The bottom left-hand panel in Fig. 1 shows that our MUSE exposure covers almost the whole extent of the bar and a sizeable part of the major disc. The bottom right-hand panel highlights a ring with a semi-major axis of ~10.4′′, semi-minor axis of ~4.3′′, and position angle similar to that of the major disc (see also Figs. 3 and 4). This is the nuclear ring mentioned earlier with a width of about 2′′, and it is hereafter referred to as the 10′′ ring.

In Fig. 2 we show the location of NGC 4371 in the Virgo cluster, as projected on the plane of the sky. NGC 4371 is a member of sub-cluster A (Gavazzi et al. 1999). It is near the bottom of the cluster’s potential well and near one of its brightest galaxies, M 87, and its extended X-ray halo of hot gas. The distance to NGC 4371, measured from surface brightness fluctuations, is 16.9 ± 0.6 Mpc (Blakeslee et al. 2009), while the distance to M 87 is 16.4 ± 0.5 Mpc (see Bird et al. 2010, who reach this value by averaging different direct measurements). Projected on the plane of the sky, the distance between the two galaxies is about 1.5 deg, corresponding to about 0.4 Mpc. The virial radius of the cluster is approximately 1.8 Mpc (Hoffman et al. 1980), while the heliocentric radial velocity of NGC 4371, 933 km s-1 (Cappellari et al. 2011), is close to the mean Virgo velocity of 1035 km s-1 (Mould et al. 2000). Together, these figures indicate that it is very probable that NGC 4371 undergoes significant interaction with the cluster environment. The results from, for example, Petitpas & Wilson (2004) and Brown et al. (2011) indicate that the galaxy contains very little atomic and molecular gas. This could be the result of processes induced by the dense environment where the galaxy is located. We come back to this point in Sect. 7.

4. Structural analysis

To achieve as thorough an understanding as possible of the spatial variations in spectral properties in galaxies, such as kinematic measurements, stellar ages, and metallicities, we need to study their structural properties. A very effective way of investigating the formation histories of galaxies is to combine spectral information, such as kinematics, with photometric and/or morphological information, such as the structural properties of different stellar components in a galaxy. As an example, we could use photometric information to understand where the bulge dominates in a given galaxy and in this way isolate – using only spectra from that region – the bulge mean stellar metallicity or age from the corresponding parameters of the disc or the galaxy as a whole (see e.g. Coelho & Gadotti 2011). This section is thus mainly focused on investigating the structural properties of NGC 4371 in detail before we dive into the spectral properties derived from our MUSE SV data.

We take advantage of the fact that NGC 4371 has already been observed with powerful imagers, such as those onboard the Spitzer Space Telescope and the HST. We use the former to derive structural properties of the major disc and bar of the galaxy. We use a 3.6 μm image (from the Infrared Array Camera (IRAC) Channel 1) obtained as part of the S4G. The pixel size of the S4G image is 0.75′′ and the point spread function (PSF) FWHM is ~1.8′′ (Kim et al. 2014). At these wavelengths, dust extinction and emission have little effect on our measures so they provide a very accurate representation of the bulk of the stellar population in the galaxy. Meidt et al. (2012) find that the contribution from polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and hot dust is between about five and ten per cent of the integrated light at 3.6 μm. The HST image (downloaded from the Hubble Legacy Archive) is used to study the inner structural components, where the pixel size and spatial resolution of the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS) provide a particularly sharp view. The pixel size is 0.05′′, and the PSF FWHM is ~0.09′′. Although in this case we had to use an optical passband, we used an image taken with the F850LP filter, which has the peak of transmission at about 850 nm, to minimise dust effects. This HST image was taken as part of the ACS Virgo Cluster Survey (Côté et al. 2004).

4.1. Major structures

|

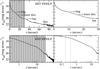

Fig. 3 Surface brightness radial profile of NGC 4371. The top panels show only the profile derived from ellipse fits to the S4G image. The bottom panels also show the profiles of the different model components obtained with BUDDA: bulge in red, disc in blue, bar in green, and central point source in violet. The profile corresponding to the total BUDDA model is in magenta. The horizontal dotted line shows the surface brightness level below which background noise becomes important. The panels on the right focus on the inner 90′′ (shaded area on the left panels). The outer exponential disc, as well as the bump caused by the bar, are clearly seen. We also point out the bump at a radius of 10′′, produced by the ring shown in Fig. 1, and a clearly exponential region that dominates the profile between the ring and the bar-dominated region, which appears to be an inner disc, given its exponential profile. |

The top panels of Fig. 3 show the radial surface brightness profile derived from the S4G image with ellipse fits to the isophotes, using the ellipse task in IRAF. The bottom panels show the result of an image decomposition with BUDDA (de Souza et al. 2004; Gadotti 2008). The fit includes models for a photometric bulge, a bar and a type II disc (see e.g. Erwin et al. 2008, and references therein, for the different types of disc profiles4), and it also takes the presence of a bright central point source into account. The bulge and the bar are fitted using Sérsic functions, whereas the disc is fitted with a double exponential. A signature of the ring shown in Fig. 1 can be seen in the surface brightness profile, i.e. the characteristic bump at a galactocentric radius of about 10′′. We also see a clearly exponential section in the surface brightness profile between the ring and the bar, which dominates to about 20′′, so appears to be an inner disc. For now, we leave out a discussion of whether the structure we refer to as an inner disc is a barlens, but we note that barlenses also usually show exponential profiles. We return to this question in Sect. 5, where the analysis of the kinematical properties of NGC 4371 sheds light on it. Essentially, the model for the photometric bulge accounts for all light above the inward extrapolation of the disc exponential profile, except the bar.

The profiles shown in Fig. 4 are also derived from ellipse fits. They show the features in the isophotes’ geometric properties that correspond to the major disc, the bar, and the 10′′ ring. Since the ring has a width of only ≈2′′, the plateau in ellipticity seen between ≈11′′ to ≈17′′ does seem to be associated with the inner disc. Assuming that the major disc is infinitely thin and taking the global maximum in the ellipticity profile into account – which happens to be at the region where the disc dominates – we can derive the galaxy inclination with respect to the plane of the sky to be ≈60°. The main structural parameters obtained from the fit to the S4G image can be found in Table 1.

|

Fig. 4 Radial profiles of position angle, ellipticity, and the b4 Fourier coefficient of the ellipses fitted to the isophotes of NGC 4371 in the S4G image, as indicated. The right panels focus on the inner 60′′ (shaded area on the left panels). In the ellipticity profile we indicate features produced by the 10′′ ring, inner disc, bar, and major disc. |

Structural properties of the stellar components in NGC 4371, as derived from the S4G image BUDDA fit.

4.2. Inner structures at high resolution

The fit to the HST image was done with GALFIT (Peng et al. 2002, 2010). This is because GALFIT easily allows an arbitrary number of components to be included in the model, and this proved to be necessary when we studied the HST image, to account for the different structural components in the galaxy central region. It also allows for a very careful modelling of the PSF, by using a PSF image derived directly from the ACS image, i.e. without the need to assume that the PSF follows any particular function. This is important, as below we look at structural components at the very centre of NGC 4371. The structural parameters found for the major disc and the bar in the fit of the S4G image were kept fixed in the fit of the HST image, where we focus on the central components.

|

Fig. 5 Surface brightness radial profiles of NGC 4371, derived from ellipse fits to the HST image. The right panels focus on the inner 30′′ (shaded area on the left panels). Bottom panels have the radial axis displayed on a log scale. The vertical dashed lines indicate the positions of the nuclear features seen in the position angle and ellipticity radial profiles derived from the HST image (see Fig. 6). |

|

Fig. 6 Radial profiles of position angle, ellipticity, and the b4 Fourier coefficient of the ellipses fitted to the isophotes of NGC 4371 in the HST image, as indicated. The right panels focus on the inner 5′′ (shaded area on the left panels). The positions of nuclear features seen in the position angle and ellipticity profiles are indicated by vertical dashed lines. |

Figures 5 and 6 show results from ellipse fits to the HST image. Given the improved spatial resolution with respect to the S4G image, we can now focus on the galaxy central region. Features in the ellipticity and position angle radial profiles can be seen at 0.18′′ and 0.4′′ from the centre, in the right-hand panels of Fig. 6. This figure also shows a peak in the ellipticity profile at about 3′′.

|

Fig. 7 Colour composites produced from HST images (F850LP and F475W) at the Hubble Legacy Archive website. Top: a clear view of the 10′′ ring. Bottom: the very inner region of NGC 4371. The blue point source in the north is ≈4′′ from the centre. The bottom panel clearly shows distinct features in the very centre, all elongated, with major axes positioned along the east-west direction. From inside out, a bright yellow-reddish, slightly less elongated structure with a semi-major axis of ≈0.15′′. Further out, a dusty ring with semi-major axis of ≈0.6′′, and just at the outer rim of it, at ≈0.8′′, a bluish ring. These dusty disc-like structures were also noted by Ferrarese et al. (2006; see also Comerón et al. 2010). North is up, east is to the left. |

In Fig. 7 we take a close look at the stunning features shown with HST imaging near the centre of the galaxy. This figure shows a colour composite using F850LP and F475W HST images. The bottom panel zooms in on the upper panel, focusing on the central features. The 10′′ ring is again clearly seen in the upper panel. We can also see a few other features in the bottom panel. From inside out, starting from the very centre, we see a bright yellow-reddish, slightly less elongated structure with a semi-major axis of ≈0.15′′. Further out, we find a dusty ring with semi-major axis of ≈0.6′′. Both of these features are at positions roughly coincident with the features seen in the position angle and ellipticity profiles (at 0.18′′ and 0.4′′, respectively, see Fig. 6). Just at the outer rim of the dusty ring, at ≈0.8′′, there is a bluish ring. These dusty disc-like structures were also noted by Ferrarese et al. (2006) and Comerón et al. (2010). Collectively, we call these structures the nucleus (except for the less elongated, central component within a radius of ~0.15′′), and they are included as a single component in the HST image fit with GALFIT.

|

Fig. 8 Central region of the F850LP HST image after unsharp masking. The 10′′ ring is clearly visible, as well as another elongated, disc-like structure with semi-major axis of ≈3.2′′ and semi-minor axis of ≈1.4′′, as delineated by the red ellipse. It has a width of about 2′′. The structures seen at the very centre of the galaxy in the bottom panel of Fig. 7 (within ≈0.8′′) are within the elongated dark blob at the centre of this figure. |

Surrounding all these components there is a fainter elongated structure, which can also be seen in the unsharp mask shown in Fig. 8. The structure has a semi-major axis of ~3.2′′, a semi-minor axis of ~1.4′′, and a width of about 2′′. The elongated dark blob, seen at the centre in Fig. 8, corresponds to the structures seen in Fig. 7 within ~0.8′′.

Structural properties of the inner stellar components in NGC 4371 as derived from the HST image GALFIT fit.

The fit to the HST image thus includes models for the major disc, the bar, the inner disc, and the nucleus, and again accounts for a central point source, i.e. the less elongated, central component within a radius of 0.15′′. No extra component is necessary to account for the presence of a bulge. Also, the 10′′ ring and the 3′′ disc-like structure at the centre are not included in the fit. The discs are fitted with single exponential functions, whereas the bar is fitted with a Ferrer function and the nucleus with a Sérsic function. The fit extends to 118′′, i.e. before the disc break seen with the S4G image, and thus a double exponential function for the major disc is not necessary. Results from this fit can be found in Table 2.

In the top right-hand panel of Fig. 5, we can see that the inner ~4′′ can be described as a pair of different exponentials. The outer one starts at about 1′′ and extends to about 4′′ and thus seems to be associated with the 3′′ disc-like component. Within 1′′ there is another exponential section, which is therefore associated with the nucleus component. This is consistent with the Sérsic index found for the nucleus, i.e. nn = 1.1 (see Table 2), or, essentially, an exponential function. The central point source also makes its mark in the bottom right-hand panel of Fig. 5. The curvature of the surface brightness radial profile changes precisely at the position of the inner vertical dashed line, which indicates the nuclear feature seen in the position angle and ellipticity profiles (Fig. 6).

We now have a good understanding of the stellar components hosted by NGC 4371 in the context of their structural properties, such as geometrical properties. Of interest is the lack of any signature of a massive component that could be a classical, merger-built bulge. The components fitted by the photometric bulge model in the decomposition of the S4G image are now understood to be the inner disc, the 10′′ ring, the 3′′ disc-like structure, and the nucleus. All these components appear to be disc-related and are not the outcome of a catastrophic event. That is not to say that they were not formed from accretion of external material, but a simpler explanation for their existence does not involve major mergers. A more likely explanation is internal processes, such as evolution driven by disc instabilities such as the bar.

Erwin et al. (2015) argue that NGC 4371 hosts a small classical, merger-built bulge. This claim is partly based on the evidence that the mean ellipticity in the inner 5′′ is less than for the 10′′ ring and major disc, indicating a rounder component. Consistent with this picture, Erwin et al. also use SINFONI data to show that there is a significant increase in the strength of random stellar motion in this region. On the other hand, Figs. 5, 7, and 8 show that the 3′′ component is rather disc-like, as are the components making up what we call the galaxy nucleus, such as the dusty and the bluish ring-like structures clearly seen at the bottom panel of Fig. 7. In addition, our HST image fit yields a Sérsic index of 1.1 for the nucleus component, indicating a disc-like structure (see Table 2 5), built from the major disc, since minor mergers are known to result in Sérsic indices significantly larger than 1 (see Aguerri et al. 2001; but see also Querejeta et al. 2015 and Christensen et al. 2014). We cannot say much about the point source component within a radius of about 0.15′′, however. Physically, this corresponds to about 12 pc, which means it could be a nuclear stellar cluster (see Böker et al. 2004). We return to discussing whether NGC 4371 hosts a small classical bulge in Sect. 5 below, using our kinematical measurements.

Furthermore, taking results of our fits with BUDDA and GALFIT, we also created structural maps. These are simply masks, one for each component fitted, as well as for the 3′′ disc-like component and the 10′′ ring, which indicate in the MUSE field where each component dominates the emission of light from the galaxy, as seen with the S4G and HST images. Thus, each spatial element is assigned to a single structural component, namely the one that dominates the light at that spatial element, above the other components that might contribute to the light in that spatial element. We therefore constructed structural maps for the central point source, the nucleus, the 3′′ disc-like component, the 10′′ ring, the inner disc, the bar, and the major disc. These maps are used below to enhance our understanding and interpretation of the results from the MUSE data cube regarding kinematics and stellar content.

5. Stellar kinematics

In this section, we first explain the steps taken to extract the kinematics information on NGC 4371 from the MUSE data cube, and then we show the results thus obtained. We also connect these results with those from the previous section.

5.1. Extraction of the kinematic maps

|

Fig. 9 Sample of spectra extracted from our MUSE data cube. Left panels show the region around the Mgb feature, while right panels show the region around the CaII triplet. Top panels show the spectrum extracted from a region in the northern part of the bar, 25′′ from the centre, with an aperture of 1.2′′ or 6 spaxels in diameter. Middle panels show the spectrum obtained from the eastern side of the 10′′ ring with an aperture of 0.8′′. Finally, bottom panels show the spectrum from the central spaxel. |

|

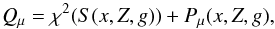

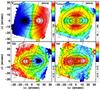

Fig. 10 Radial velocity, velocity dispersion, and h3 and h4 maps for the stellar component in NGC 4371, as indicated. The colour bars on the side of each panel indicate the plotted range of the parameter measured. For radial velocity and velocity dispersion these are given in km s-1. The isophotes shown are derived from the MUSE cube reconstructed intensities and are equally spaced in steps of about 0.5 mag. North is up, east to the left. The nearly vertical dashed line indicates the position of the bar major axis. The horizontal elongated markings indicate the outer boundary of the region dominated by the inner disc, at ~20′′, as derived through the ellipse fits, and the position of the 10′′ ring. |

A high quality analysis of the stellar kinematics requires a minimum signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) in the spectra. To derive the radial velocity and the velocity dispersion that best represent the line of sight velocity distribution (LOSVD) at a given position in the galaxy, the corresponding minimum S/N is not a limiting condition. However, the derivation of the higher order Gauss-Hermite moments h3 and h4 of the LOSVD requires high S/N (see van der Marel & Franx 1993; Gadotti & de Souza 2005). Using a Voronoi binning scheme (Cappellari & Copin 2003), we binned our data spatially to achieve a minimum S/N of ≈100 at each spatial element. Central pixels surpass this limit by a long way and therefore remain unbinned. To avoid contamination at each spatial element by spaxels with a very weak signal, we also implemented a minimum S/N threshold of ≈3 for a spaxel to be considered. Therefore, the edges of the maps shown below from our MUSE data cube are not straight lines, since pixels at these edges do not reach the minimum threshold in S/N.

To illustrate the quality of the spectra used here, in Fig. 9 we show a sample of spectra extracted from our MUSE data cube, corresponding to different parts of the galaxy. As mentioned previously, our spectra cover the range from 4750 Å to 9300 Å, but for clarity we only show two spectral regions here: one around the Mg b feature and the other around the CaII triplet. While the central spectrum was extracted from a single spaxel, the spectrum from the eastern side of the 10′′ ring is a median combination of spectra within a 0.8′′ aperture, i.e. four spaxels in diameter. Likewise, the spectrum from the northern part of the bar, at 25′′ from the centre, corresponds to an aperture of 1.2′′. These apertures correspond to the typical Voronoi spatial bins we used at these regions. This spatial binning appears to be efficient in keeping the S/N at a suitable level throughout the field.

We used the penalised pixel fitting (pPXF) code developed by Cappellari & Emsellem (2004) to extract the stellar kinematics, including higher order moments. The result is an LOSVD described by a Gauss-Hermite parametrisation (Gerhard 1993; van der Marel & Franx 1993), with a measure of the radial velocity (v), velocity dispersion (σ), and higher order Gauss-Hermite moments (h3 and h4). The h3 and h4 moments indicate, respectively, asymmetric and symmetric deviations from an LOSVD that is a pure Gaussian. In other words, h3 is basically a measure of the skewness of the LOSVD, whereas h4 is essentially a parameter that quantifies the kurtosis of the LOSVD. They can be used to examine the orbital structure of the stellar system in question. For instance, circular motion results in h3 values that are anti-correlated with v. And high values of h4 suggest the superposition of structures with different LOSVDs (see e.g. Bender et al. 1994, and references therein). These values are determined through a fitting process where the routine combines a number of template spectra from a previously defined stellar spectra library to fit the galaxy spectrum of each element. Here we used a subset of the MILES single stellar population (SSP) model spectra (Vazdekis et al. 2010) with a mean resolution with FWHM of ≈2.5 Å (Falcón-Barroso et al. 2011) to match the spectral resolution in MUSE. The resolution of the model spectra is adjusted to the spectral resolution of the data before the fitting process. We cover the following range of ages and metallicities with the SSP template spectra: 0.1 Gyr to 17.8 Gyr, and −0.40< [Z/H] <+ 0.22, respectively. Throughout this work we assume a Kroupa initial mass function (IMF, Kroupa 2001). A wide wavelength range was employed in the fits, namely from 4750 Å to 8800 Å, which improves the S/N, compared to narrow wavelength ranges.

|

Fig. 11 Map of λR for NGC 4371. The isophotes shown are derived from the MUSE cube reconstructed intensities and are equally spaced in steps of about 0.5 mag. The right panel focusses on the inner 10′′. North is up, east is to the left. The nearly vertical dashed line indicates the position of the bar major axis. The horizontal elongated markings indicate the outer boundary of the region dominated by the inner disc, at ~20′′, as derived through the ellipse fits, and the position of the 10′′ ring. |

Our MUSE spectra virtually reveal no emission lines, except for a weak [NII] emission at 6583 Å in the inner 1′′, where the nucleus and the central point source dominate. The [NII] equivalent width in the integrated spectrum obtained by combing all spectra within 1′′ is ≈0.5 Å, but Hα is seen only in absorption. We come back to this point in Sect. 7, but we point out here that the lack of emission lines means that the results from our pPXF fits are not complicated in this respect.

5.2. The kinematics of the different structural components in NGC 4371

5.2.1. Kinematic maps

Figure 10 shows stellar kinematics maps of radial velocity v, velocity dispersion σ, and Gauss-Hermite moments h3 and h4. Intensity contours equally spaced in steps of about 0.5 magnitudes are indicated. NGC 4371 was also observed with SAURON (see Bacon et al. 2001; de Zeeuw et al. 2002), as part of the ATLAS3D survey (Cappellari et al. 2011), covering the inner 30 × 40 arcsec. Our MUSE data reveal a multitude of details not visible in the previous data set. It is easy to contemplate the major improvement brought about with MUSE by the same PI and the MUSE consortium a decade later (Bacon et al. 2010).

The stellar velocity field exhibits an overall regular rotation pattern, with enhanced central regions hinting at distinct kinematic components in those regions. This is confirmed in the other maps. The line of nodes is almost aligned perpendicular to the bar major axis and only shows a very slight twist in the region covered by the MUSE field, namely around 5′′ off the centre and in the bottom part of the field. The overall velocity seems to increase towards the edges of the field, suggesting that we do not reach the peak in the rotation curve.

The stellar velocity dispersion is generally elevated within an almost circular region of radius of about 20′′, with several well-defined regions presenting varied patterns in terms of velocity dispersion. There are two large regions of higher velocity dispersion above and below the centre along the bar major axis, and two other large regions of lower velocity dispersion along the east-west direction. The very centre does not exhibit the highest velocity dispersion, but there seem to be four concentrated regions around the centre (and about a few arcseconds from it) with higher velocity dispersion; two of these regions are aligned with the east-west direction, the other two with the north-south direction.

The h3 parameter strongly anti-correlates with the radial velocity, in particular in the regions of high absolute radial velocity and low velocity dispersion, both in the inner regions, as well as at the edges of the field. The two regions showing the highest absolute values of h3 at about 10′′ from the centre, both to the east and west, also show the highest h4 values. There are also two well-defined, concentrated regions showing high absolute values of h3 at a radius of about 1−3 arcsec, again both at east and west. These regions show counterparts with high radial velocities in the radial velocity map. The h4 map also shows a region of high values that can be described as an elongated ring with semi-major axis reaching out to about 20′′ along the east-west direction. A similar elongated region around the centre, extending to ~5′′, also shows high h4 values. Two of the four circumnuclear regions with high velocity dispersion show a hint of relatively low h4 values. These are the ones along the east-west direction. A similar relative drop in h4 for the other two regions along the north-south direction is not so discernible. The large-scale structure in the h4 map also displays asymmetric features at its edges.

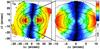

Another important kinematical parameter to be considered here is λR. This parameter was introduced by Emsellem et al. (2007) as a proxy to quantify the observed projected stellar angular momentum per unit mass. It is defined as  (1)where R is the galactocentric radius. Figure 11 shows the corresponding map, which more clearly shows the features now that produce the pinching along the east-west direction in the inner 2−3 arcsec. These features already appear in the above maps of radial velocity and h3, and they correspond to relatively high angular momentum. The map also shows the high angular momentum component at 10−20 arcsec from the centre along the east-west direction.

(1)where R is the galactocentric radius. Figure 11 shows the corresponding map, which more clearly shows the features now that produce the pinching along the east-west direction in the inner 2−3 arcsec. These features already appear in the above maps of radial velocity and h3, and they correspond to relatively high angular momentum. The map also shows the high angular momentum component at 10−20 arcsec from the centre along the east-west direction.

5.2.2. The bar, box/peanut, and barlens

How do all the features seen in these maps relate to the structural components discussed in Sect. 4? The high rotational support in the region dominated by the major disc is no surprise. The bar shows a remarkable region with high velocity dispersion. Because the galaxy is quite inclined (i ≈ 60°), these measures of σ have components of velocity dispersion both on the plane of the disc and in the direction perpendicular to it. Could these enhancements in σ be caused by a box/peanut? To try answering this question we compared our maps with those recently published by Iannuzzi & Athanassoula (2015). They produced maps similar to ours from simulations of barred galaxies at different evolutionary stages, before and after the formation of the box/peanut in the bar. Their figures 29 and 31 show their simulation GTR101 at a very similar projection to how we see NGC 4371. Their velocity dispersion maps show enhancements along the bar major axis that very much resemble our results for NGC 4371, particularly after the formation of the box/peanut. Another signature of box/peanuts pointed out by Debattista et al. (2005) and corroborated by Iannuzzi & Athanassoula (2015; see also Méndez-Abreu et al. 2008) are minima in h4 seen along the bar major axis at each side of the centre. Our h4 measures along the bar major axis suggest the presence of such minima, particularly at the bottom of the field. Nevertheless, we admit that this evidence is only indicative. Erwin & Debattista (2013) do not find evidence of a box/peanut in NGC 4371 but they cannot rule out its existence. Overall, it seems plausible that NGC 4371 does have a box/peanut. Such structures are known to reduce the strength of bars in inducing secular evolution processes and might significantly influence the evolutionary processes in a galaxy, such as gas flows (see Fragkoudi et al. 2015).

As mentioned above, recent studies have put forward arguments to suggest that box/peanuts have a counterpart in the plane of the disc, and these are barlenses (Laurikainen et al. 2014; Athanassoula et al. 2014; Athanassoula 2015; Laurikainen & Salo 2015). We do not find evidence for a barlens in NGC 4371 in the kinematic maps. In the structural analysis carried out in Sect. 4, the only structural component found that could be a barlens is what we call the inner disc, which dominates the emission of light from the galaxy from a radius of about 10′′ to about 20′′. Figures 10 and 11 clearly show that this component is strongly supported rotationally. It is not yet clear whether this would be consistent with a barlens, but it is certainly consistent with an inner disc. Therefore, if NGC 4371 does have a box/peanut, it may not be strong enough to produce an evident signature of its disc plane counterpart, the barlens, in our data. In addition, projection effects and/or the presence of the other conspicuous inner components in the same region, such as the inner disc in fact, could be masking out signatures of the barlens.

5.2.3. The inner disc, 10′′ ring and inner structures

The 10′′ ring is right at the inner edge of the inner disc and cannot be distinguished from it in Figs. 10 and 11, except perhaps in the h4 map. The fact that this separation is not straightforward hints at a connected formation history. At a radius of about 10′′ we see a peak in h4, higher than the values seen between about 10′′ and 20′′, i.e. through the full extent of the inner disc. The peak in h4 can be explained if the inner disc and the 10′′ ring have somewhat different LOSVDs.

The 3′′ disc-like component can also be seen in the kinematic maps. This is a fast rotating central component, seen near the centre, as the two concentrated peaks of absolute radial velocity and h3, and λR. The major disc, the inner disc, the 10′′ ring, and the 3′′ disc-like structure all show a strong anti-correlation between radial velocity and h3, consistent with circular motion. Therefore, all such structural components, found through the image decompositions, have their existence corroborated and better understood through the kinematic maps. The central point source and the components that we have collectively called the galaxy nucleus dominate the central 1′′.

We can now return to the question of whether NGC 4371 hosts a small classical bulge, within 5′′ from the centre, as suggested by Erwin et al. (2015). Our maps show clearly that the 3′′ disc-like component is strongly supported by rotation and circular motion, which again argues against the presence of a classical bulge that extends to a few arcseconds. (Unless, somehow, a component with relatively high angular momentum results from the bulge formation processes, despite their violent nature. Another possibility is that the small classical bulge did not originally have significant angular momentum, but that it was spun-up by the bar; see Saha et al. 2012.) Furthermore, to the spatial resolution limit that we can achieve with these observations (i.e. ≲1′′), the central values of velocity dispersion are below those along the inner part of the bar major axis, i.e. there is no discernible kinematically hotter component in our central kinematic bins. A caveat here, however: if the light from the central bins is biased towards a relatively younger population that is kinematically colder – even though, as we will see shortly, the stellar population content in the centre is predominantly very old – this could mask an older, kinematically hotter component. The measurements presented in Fig. 6 of Erwin et al. (2015) were made in the near-infrared and with adaptive optics, using SINFONI at the VLT, and therefore reach a spatial resolution that is much higher than our own measurements (i.e. ≈0.1′′). From a kinematical perspective, we cannot rule out that the nucleus was built through mergers, but our fits to the HST image of NGC 4371 result in a nucleus with an exponential, disc-like light profile. In addition, there is a peak in ellipticity at a radius of ≈0.4′′, where the nucleus dominates. We can say very little about the central point source here.

6. Stellar population content

As in the previous section, here we focus first on the methodology employed to study the properties of the different stellar populations in NGC 4371, and then show the results thus obtained. We connect these results with the results from our structural and kinematical analyses above and, in particular, make use of the structural maps described in the last paragraph of Sect. 4.

6.1. Extraction of the stellar age and stellar metallicity maps

In this paper, we have chosen to perform a full spectral fitting using the code STECKMAP (STellar Content and Kinematics via Maximum A Posteriori likelihood, see Ocvirk et al. 2006a,b). The reconstruction of the stellar age distribution and the age-metallicity relation is non-parametric, i.e. no specific shape for the star formation history is assumed. The problem of obtaining this physical information from the observations is an ill-conditioned problem (Ocvirk et al. 2006a), where small fluctuations in the data can result in large variations in the solution. To deal with this problem, STECKMAP makes a statistical regularisation with the prior in such a way that solutions that change smoothly are more likely to result. This is the only a priori condition. The smoothness parameter can be set by generalised cross-validation of the possible solutions, accounting for the level of noise in the data, to avoid over-interpretation of the results (see Ocvirk et al. 2006a, for details).

The function to minimise is defined as  (2)which is a penalised χ2, where S represents the synthetic spectrum, x the flux distribution, Z the metallicity distribution, and g the broadening function. The penalisation Pμ can be written as Pμ(x,Z,g) = μxP(x) + μZP(Z) + μvP(g), where the function P gives high values for solutions with strong oscillations (flux or metallicity changing rapidly with time) and low values for smoothly varying solutions. Adding the penalization P to the objective function is exactly the same as injecting an a priori probability density distribution to the solution, as fprior(x) = exp(−μxP(x)), where P is a quadratic function of the unknown.

(2)which is a penalised χ2, where S represents the synthetic spectrum, x the flux distribution, Z the metallicity distribution, and g the broadening function. The penalisation Pμ can be written as Pμ(x,Z,g) = μxP(x) + μZP(Z) + μvP(g), where the function P gives high values for solutions with strong oscillations (flux or metallicity changing rapidly with time) and low values for smoothly varying solutions. Adding the penalization P to the objective function is exactly the same as injecting an a priori probability density distribution to the solution, as fprior(x) = exp(−μxP(x)), where P is a quadratic function of the unknown.

We use again the MILES SSP spectral models (Vazdekis et al. 2010), spanning an age range of between 6.3 × 107 to 1.7 × 1010 yr, divided in 30 logarithmic age bins. The metallicity ranges from [ Z/H ] = −1.3 to [ Z/H ] = + 0.2.

Although STECKMAP can be used to obtain the broadening of the lines, here we use the values obtained in the previous section, calculated with pPXF, and thus fix the broadening function during the fit. The reason for this choice comes from the existing degeneracy between metallicity and σ (Koleva et al. 2008; Sánchez-Blázquez et al. 2011), which biases the mean-weighted metallicity if both parameters are fitted at the same time. We also do not fit the continuum to avoid dealing with possible flux calibration errors or dust extinction. Instead, we multiply the model by a smooth non-parametric transmission curve. This curve is obtained by interpolating a spline function between 30 nodes, spread uniformly along the wavelength range. The choice of fitting or not the continuum may have a strong influence on the derived parameters when the S/N of the spectrum is not very high. For spectra with S/N> 30 per Å the results obtained are independent of rectifying or not the continuum (Sánchez-Blázquez et al. 2011).

|

Fig. 12 Mass (top panel) and flux (middle panel) fractions as a function of age, and the age-metallicity relation (bottom panel), obtained for the central spectrum of NGC 4371. Metallicities are plotted only for flux fractions larger than 5%. |

We ran STECKMAP on each of the binned spectra and obtained star formation histories and age-metallicity relations for all of them. Figure 12 shows an example of a typical STECKMAP output, showing the flux, mass, and metallicity distributions as a function of age.

We can obtain mean values of age and metallicity per spectrum weighting with either the flux or the mass. Flux-weighted values are biased towards younger populations, since young stars are brighter in the considered wavelength range. Mass-weighted values may, on the other hand, be much more uncertain, especially when a large number of old, low-luminosity stars are present. To better understand how uncertain our mean stellar age estimates are at each spatial resolution element – which will be discussed at length below – we performed 100 Monte Carlo realisations using all binned spectra. We find that the error in luminosity-weighted age is anti-correlated with the mean age on a logarithmic scale. Considering luminosity-weighted estimates, the median of the error distribution is 0.035 dex for a mean stellar age of 10 Gyr, while the median error is 0.05 dex for a mean stellar age of 7 Gyr. Therefore, for these mean ages, the uncertainty in the mean stellar age is ~0.8 Gyr. This anti-correlation is not present, however, when we consider mass-weighted estimates, which have a median error of 0.014 dex. One should note that the Monte Carlo realisations only address uncertainties of a Poissonian nature. Uncertainties arising from the spectral models we employed are not included. In addition, our age measures may also have systematic effects leading to higher values, because we have measured ages reaching slightly older than the currently accepted age of the universe, in particular when we consider mass-weighted estimates. In an attempt to neutralise this effect, our main conclusions below are based on the luminosity-weighted estimates, which are systematically lower than the mass-weighted estimates. In addition, we consider the lowest age values whenever there is a wide enough distribution of mean stellar ages.

6.2. Spatial distribution of the different stellar populations

|

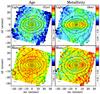

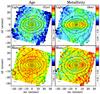

Fig. 13 Maps for NGC 4371 of mean stellar age (left panels) and stellar metallicity (right panels) weighted by both luminosity (top panels) and mass (bottom panels). The age maps have units of giga-years, and metallicities are given in the spectroscopic notation (logarithmic scale normalised to the solar value). |

Figure 13 shows the luminosity- and mass-weighted maps of age and metallicity for NGC 4371, derived using the method described above. The mass-weighted mean stellar age map shows that the vast majority of stars in the galaxy are old with ages above 10 Gyr. The major disc shows stars that are, on average, somewhat younger than the rest of the galaxy, but still old. Similarly less old stars, on average, appear also just inside of the west side of the 10′′ ring. Bins containing the oldest stars are seen preferentially in parts of the bar and the inner disc. The luminosity-weighted map shows more structure. Again, it shows fewer old stars in the disc and in parts just inwards of the 10′′ ring (i.e. in the inner part of the inner disc), especially its western side. The bar shows a population of a somewhat intermediate-age, with mean ages of between those of the major disc and the remaining central components. Still, even in the luminosity-weighted map, almost all bins inwards of the region dominated by the major disc show mean stellar ages above 10 Gyr.

From the luminosity-weighted metallicity map, we see that the disc shows a very homogeneous distribution of metallicity. In addition, the outer parts of the bar show a slightly elevated metallicity, while the central regions show a remarkable peak in metallicity. Finally, the 10′′ ring shows a significantly elevated metallicity, in comparison to the outer components. The mass-weighted map shows fewer features, but does indicate a very strong peak in the central metallicity and the elevated metallicity of the 10′′ ring.

|

Fig. 14 Top panels: luminosity-weighted maps of stellar populations separated by mean stellar age, as indicated (young; intermediate; old). The colour-coded scale, indicated by the colour bar on the right side of each panel, corresponds to the fraction of the stellar population (young, intermediate, or old) at each spatial element. Bottom panels: corresponding mass-weighted maps. The scale changes for each panel to show the corresponding relevant features. The indicated limits of the colour bars, however, show that most of the mass and light are in (or come from) stars older than 8 Gyr. |

In Fig. 14, we show luminosity-weighted and mass-weighted maps that represent the location of three different stellar populations in NGC 4371, according to their ages: young (age <1 Gyr), intermediate (1 < age < 7 Gyr) and old (age >8 Gyr). These roughly correspond to a formation redshift of around z ≲ 0.08, 0.08 ≲ z ≲ 0.8, and z ≳ 1, respectively, (although we stress again here that the correspondence between mean stellar age and formation redshift is not trivial, given the uncertainties in the age estimates). The colour-coded scale corresponds to the fraction of the corresponding stellar population (young, intermediate age, or old) at each spatial element. The scale changes for each panel, to show the corresponding relevant features. The scale ranges are indicated below the colour bars on the right-hand side of each panel. Most stars in the central arcminute squared of NGC 4371 are older than 8 Gyr. Figure 14 shows that, basically, stars formed at redshifts z ≲ 0.08 are found on the outskirts of the field (i.e. in the major disc) and to a much lesser extent in the bar. Stars formed between about 1 and 7 Gyr ago are found preferentially in the major disc and in the portion of the inner disc inside of the 10′′ ring. To a lesser extent, similar stars can be found in the bar. These younger stars, however, represent an insignificant fraction of the stellar content in this region of the galaxy probed by our MUSE observations. An important point to make here is that the mean stellar age in all these bins in which stars younger than 7 Gyr are found is actually above 8 Gyr, as demonstrated in Fig. 13. This is further illustrated below. The outer part of the inner disc and the inner 5′′ show the highest densities of stars formed more than 8 Gyr ago.

|

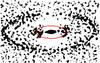

Fig. 15 Normalised distributions of the mean stellar age and metallicity per spatial bin, separated by structural components, as indicated. The mass-weighted distributions are plotted in red, and luminosity-weighted distributions in blue. |

There are other powerful ways of visualising the information content in such maps that may disclose important clues in a more straightforward way. One such way is presented in Fig. 15, which shows the normalised distributions of the mean stellar age and metallicity of the spatial bins in each structural component. These were derived by using the structural maps produced in Sect. 4 and combining them with the age and metallicity maps produced in this section (Fig. 13). These distributions corroborate our previous assessments and also reveal further aspects of the stellar content in NGC 4371. The luminosity-weighted metallicity distributions appear to be bimodal for the major disc and bar components. Their mass-weighted metallicity distributions show a peak that roughly coincides with the high metallicity peak of their luminosity-weighted distributions, but they also show a tail towards lower metallicities. Another interesting feature, that is clearly seen in the luminosity-weighted age distributions is that all components closer to the centre than the 10′′ ring have, on average, an older population of stars than the remainder of the galaxy, particularly the 3′′ disc-like component. The mass-weighted distributions, however, reveal much more subtle differences, showing that the whole stellar content of the galaxy is almost entirely very old.

|

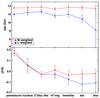

Fig. 16 Mass-weighted and luminosity-weighted mean values of stellar age and metallicity for all structural components in NGC 4371. The structural components are arranged along the x-axis such that this axis can be thought of as the galactocentric distance, i.e. the point source component is at the centre of the galaxy, and to the right side of it we arranged the other components that dominate the emission from the galaxy at successively larger distances. The error bars are an outlier-resistant measure of the dispersion about the mean, analogous to the standard deviation. |

Finally, in Fig. 16 we present plots of the mass-weighted and luminosity-weighted mean values of stellar age and metallicity for all structural components in NGC 4371. Since the components are arranged along the x-axis in a way that, from left to right, each component successively dominates at larger galactocentric distances, these plots can be thought of as stellar age and metallicity radial profiles. Again, this figure repeats some of the information already discussed above, but this visualisation format allows a more direct comparison of the mean values of each component. In addition, it shows, in a straightforward fashion, how these values vary from the centre to the outskirts of the MUSE field.

The mean stellar age profiles show how homogeneously old the stellar population is in the inner arcminute of NGC 4371 (particularly so in the mass-weighted results), with the indication that younger stars are found in the outer part of the field – in the major disc. (Similar results are found by Seidel et al. 2015 for NGC 5701, another early-type barred galaxy.) A mild drop in the mean stellar age is also seen at the 10′′ ring. The mean stellar metallicity profiles clearly show the pronounced peak in metallicity in the central components. Again, the 10′′ ring produces a bump in the curves, this time indicating a higher metal content than is expected from the global trends of the profiles, i.e. in comparison to a metal content that grows smoothly towards the centre. These profiles essentially show that, beyond the inner few central arcseconds, the mean metallicity does not vary much, whereas it starts increasing in the central arcsecond until it reaches a maximum at the very centre. The luminosity-weighted profiles in Fig. 16 show a somewhat different behaviour when compared to the mass-weighted profiles, possibly indicating different properties between a more luminous and relatively younger stellar population and the old bulk of the stellar content. These differences, along with all the results presented in this section and in Sects. 4 and 5, are interpreted and discussed in the next section.

7. Discussion

7.1. NGC 4371: a fossil record of the oldest bars

As a disc galaxy and one that hosts a large-scale bar, we expect internal secular evolution processes to have played an important role in the evolution of NGC 4371. The BUDDA fit (see Table 1) indicates that the bar-to-total luminosity ratio in the galaxy (Bar/T = 0.077) is typical of the values found for other massive galaxies. Gadotti (2011) finds that the typical Bar/T is about 0.1 in a sample of nearly 300 massive barred galaxies at z ≈ 0.05 (see also Weinzirl et al. 2009). Interestingly, the luminosity profile of the bar in NGC 4371 is very flat. This is indicated by its low Sérsic index, namely nbar = 0.2. Kim et al. (2015) have conjectured that recently formed bars have exponential luminosity profiles, i.e. with a Sérsic index ~1, but, as bars evolve, their luminosity profiles become flatter, which translates to lower values of nbar. The flattest bars in the work of Kim et al. (2015), with 144 nearby barred galaxies from the S4G, have a Sérsic index similar to that of the bar in NGC 4371. This therefore suggests that the bar in NGC 4371 formed during the epoch when the first long-standing bars were being formed. Being an evolved bar, it makes it more likely that a box/peanut has formed, because such structures are seen in simulations to form ~1–2 Gyr after the formation of the bar (see e.g. Martinez-Valpuesta et al. 2006).

As discussed in the Introduction, one of the main processes induced by large-scale stellar bars in disc galaxies is the inflow of gas towards the central regions. This inflow of gas is halted near the bar ILR and creates nuclear rings and inner discs (also known as disc-like bulges) with recently formed stars. We suggest above that, because the inner disc and the 10′′ ring in NGC 4371 are hardly distinguishable in some of the kinematic maps, they could have a connected formation history. Therefore, bar-driven gas inflows are the most natural explanation for their origin. Figure 15 shows that there is no spatial bin in the inner disc or the 10′′ ring with a mean stellar age below 10 Gyr. Thus, the last significant gas inflow induced by the bar must have happened 10 Gyr ago. In this case, not only is the bar in NGC 4371 populated by old stars, but the bar itself, as a structure, is old. In fact, the mean stellar ages of the inner disc and 10′′ ring imply that the bar was already in place at least 10 Gyr ago, i.e. at a redshift of about 1.8. Considering the results from the analysis of the uncertainties in our stellar age estimates, as described at the end of Sect. 6.1, the formation redshift of the bar is most likely between z = 1.4 and z = 2.3.

In the Introduction, we mentioned the study by Simmons et al. (2014) of the fraction of barred galaxies at high redshifts. In that work, the highest redshift galaxy found hosting a bar is at z = 1.97, similar to the formation redshift we derive for NGC 4371. The latter is then a fossil record of those bars, such as the ones found by Simmons et al., that formed in early cosmic epochs. Interestingly, the bar in NGC 4371 therefore testifies to the robustness of bars.

Alternatively, the inner disc and the 10′′ ring could have formed via a still unfamiliar mechanism (see discussion in Comerón et al. 2014; and also Eliche-Moral et al. 2011), which could mean that one cannot constrain the formation redshift of the bar using their mean stellar ages. One possibility is that they were formed by a bar that dissolved before the formation of the current one. Kraljic et al. (2012) show simulations in which bars that form at redshifts higher than 1 dissolve, while a long-standing bar forms afterwards. However, it is still unclear whether such primordial bars would be able to form long-standing inner discs and nuclear rings. It is thus unclear if the 10′′ ring would survive the dissolution of the primordial bar and the formation and evolution of the bar currently observed. On the other hand, Comerón et al. (2010) report that 19 ± 4 per cent of nuclear rings are found in unbarred galaxies. Nevertheless, the 10′′ ring in NGC 4371 is similar to the other 78 nuclear rings in the barred galaxies studied by Comerón et al. (2010), in that the ratio between the ring radius and the bar length in NGC 4371 is very typical and consistent with a picture in which the nuclear ring is formed by the bar. Overall, it is thus likely that the inner disc and 10′′ ring in NGC 4371 were formed by the bar.

7.2. The onset of bar-driven secular evolution in cosmic history

That NGC 4371 is a massive galaxy with an old bar is consistent with the results from Sheth et al. (2008, 2012) that indicate that the more massive disc galaxies form their bars first. For M⋆ ≥ 1011M⊙, Sheth et al. (2008) find that about half of the disc galaxies are already barred at z ~ 0.8. One interesting outcome of the present study is that we can provide an estimate of the formation redshift for the bar in NGC 4371, and since we know the galaxy stellar mass, we can go a step further and use this information as a benchmark to set how the bar formation epoch evolves as a function of galaxy stellar mass. Therefore, with a bar formation redshift of z ≈ 1.8 and a stellar mass M⋆ = 1010.8M⊙, NGC 4371 sets this benchmark and establishes that more massive galaxies have formed their bars at even higher redshifts.

It is interesting that the disc in NGC 4371 already had – at these relatively high redshifts – the structural and dynamical conditions favourable for the development of a long-standing bar. The internal bar-mode disc instability can happen spontaneously to any disc galaxy under the right conditions, which are, nevertheless, complex and challenging to spot (see e.g. discussion in Athanassoula 2008; Sánchez-Janssen & Gadotti 2013) but might also be catalysed by the perturbation of a companion galaxy. A number of studies have been dedicated to understanding the effects of the environment on bar formation (e.g. Aguerri et al. 2009; Li et al. 2009; Barazza et al. 2009; Méndez-Abreu et al. 2010, 2012; Skibba et al. 2012; Lin et al. 2014). While it is reasonable to consider the possibility that the bar in NGC 4371 is the result of an interaction, since the galaxy is in a dense environment, this is a difficult claim to defend. In any case, there is no observational evidence, to date, that bars that have been catalysed by encounters are in any way different from bars formed spontaneously.

7.3. Environmental effects: the lack of gas and recent star formation

The vast majority of stars in the central region of NGC 4371 have ages above ~8 Gyr (see Fig. 13), and were thus formed at redshifts higher than ~1. In addition, there are no signs of a significant recent interaction throughout the galaxy. The galaxy thus appears to have gone through no significant accretion of cold gas to its central region for the past 8 Gyr.

As mentioned above, the only emission line we find in the spectra is a weak [NII] line confined within the central 1′′ and with equivalent width of ~0.5 Å. The [NII] flux could originate from stellar photoionisation powered by young high-mass OB stars, or from other physical processes, such as shock heating or photoionisation with a power-law spectrum (see e.g. discussion in James et al. 2005). The central supermassive black hole in NGC 4371 – with a mass determined via dynamical modelling (P. Erwin et al., in prep.) – is currently not accreting (Simões Lopes et al. 2007), so we assume that all [NII] emission comes from recent star formation activity. Even so, the measured equivalent width indicates very low star-formation activity currently at the centre of NGC 4371 (see Fig. 3 in Kennicutt 1998). Nagar et al. (2005) and Capetti et al. (2009) at best also find very small radio emission from the nucleus of NGC 4371, which is consistent with low star formation or AGN activity and a low amount of cold gas. As mentioned at the end of Sect. 3, other studies have found very little atomic and molecular gas content throughout the galaxy.