| Issue |

A&A

Volume 569, September 2014

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A100 | |

| Number of page(s) | 20 | |

| Section | Astrophysical processes | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201322101 | |

| Published online | 30 September 2014 | |

Surface chemistry in the interstellar medium

II. H2 formation on dust with random temperature fluctuations

1

LERMA, Observatoire de Paris & CNRS, 5 place Jules Janssen, 92190

Meudon, France

2

Université Paris Diderot ; 5 rue Thomas Mann, 75205

Paris,

France

e-mail: jacques.lebourlot@obspm.fr

Received:

18

June

2013

Accepted:

3

June

2014

Context. The H2 formation on grains is known to be sensitive to dust temperature, which is also known to fluctuate for small grain sizes due to photon absorption.

Aims. We aim at exploring the consequences of simultaneous fluctuations of the dust temperature and the adsorbed H-atom population on the H2 formation rate under the full range of astrophysically relevant UV intensities and gas conditions.

Methods. The master equation approach is generalized to coupled fluctuations in both the grain’s temperature and its surface population and solved numerically. The resolution can be simplified in the case of the Eley-Rideal mechanism, allowing a fast computation. For the Langmuir-Hinshelwood mechanism, it remains computationally expensive, and accurate approximations are constructed.

Results. We find the Langmuir-Hinshelwood mechanism to become an efficient formation mechanism in unshielded photon dominated region edge conditions when taking those fluctuations into account, despite hot average dust temperatures. It reaches an importance comparable to the Eley-Rideal mechanism. However, we show that a simpler rate equation treatment gives qualitatively correct observable results in full cloud simulations under the most astrophysically relevant conditions. Typical differences are a factor of 2−3 on the intensities of the H2v = 0 lines. We also find that rare fluctuations in cloud cores are sufficient to significantly reduce the formation efficiency.

Conclusions. Our detailed analysis confirms that the usual approximations used in numerical models are adequate when interpreting observations, but a more sophisticated statistical analysis is required if one is interested in the details of surface processes.

Key words: astrochemistry / molecular processes / ISM: molecules / dust, extinction

© ESO, 2014

1. Introduction

H2 is the most abundant molecule in the interstellar medium. It is found in a wide variety of astrophysical environments in which it often plays a leading role in the physics and evolution of objects (see the book by Combes & Pineau des Forets 2001, for a review). As an efficient coolant of hot gas, it controls for instance through thermal balance the collapse of interstellar clouds leading ultimately to star formation. Furthermore, its formation is the first step of a long sequence of reactions leading to the great chemical complexity found in dense clouds. In addition to its physical importance, H2 is also of great observational usefulness as a diagnostic probe for many different processes in various environments.

The detailed mechanism of its formation is thus a key part of the understanding and modeling of the interstellar medium. Direct gas phase formation is very inefficient and cannot explain the observed abundances. The ion-neutral reaction H + H− is more efficient, but the low H− abundance does not allow sufficient H2 formation this way. The H2 molecule is thus thought to form mainly on the surface of dust grains (Gould & Salpeter 1963; Hollenbach & Salpeter 1971). Grains act as catalysts. They provide a surface on which adsorbed H atoms can meet and react, and they absorb that excess energy released by the formation that prevented the gas phase formation of a stable molecule.

This process is usually modeled using the Langmuir-Hinshelwood (LH) mechanism in which weakly bound adsorbed atoms migrate randomly on the surface, and one H2 molecule is formed each time two atoms meet. This mechanism has been studied in detail using the master equation approach (Biham & Lipshtat 2002), the moment equation approach (Lipshtat & Biham 2003; Le Petit et al. 2009) and Monte Carlo simulations (Chang et al. 2005; Cuppen & Herbst 2005; Chang et al. 2006). Laboratory experiments have also been conduced and their results modeled (Pirronello et al. 1997a,b, 1999; Katz et al. 1999). It is found to be efficient over a limited range of grain temperatures of about 5−15 K for flat surfaces. However, observations of dense photon dominated regions (PDRs) found efficient formation despite higher grain temperatures (Habart et al. 2004, 2011). Various modifications of the mechanism have been proposed to extend the range of efficient formation. Some authors introduced sites of higher binding energies due to surface irregularities (Chang et al. 2005; Cuppen & Herbst 2005). Some introduced a reaction between chemisorbed atoms and atoms migrating from a physisorption site (Cazaux & Tielens 2004; Iqbal et al. 2012). Others proposed that the Eley-Rideal (ER) mechanism for chemisorbed atoms is a relevant formation process at the edge of PDRs (Duley 1996; Habart et al. 2004; Bachellerie et al. 2009; Le Bourlot et al. 2012). In this mechanism, chemisorbed H atoms, which are attached to the surface by a chemical bond, stay fixed on the surface until another atom of the gas falls into the same site, forming a H2 molecule.

The grain temperatures in illuminated environments are not only higher but also strongly fluctuating. Small grains have small heat capacities, and each UV-photon absorption makes their temperature fluctuate widely. This effect has received much attention because some components of dust emission are produced during these transient temperature spikes (Desert et al. 1986; Draine & Li 2001; Li & Draine 2001; Compiègne et al. 2011). Those fluctuations are stronger in strong radiation field environments like PDRs. Moreover, usual dust size distributions favor small grains so that they contribute the most to the total dust surface, making the small grains dominant for surface reactions. Those fluctuations can thus have an important effect on H2 formation, especially in strongly illuminated environments, as temperature spikes are likely to cause massive desorption. This effect has so far only been studied by Cuppen et al. (2006) using Monte Carlo simulations for the LH mechanism, computing the H2 formation rate in one single specific diffuse cloud condition under a standard interstellar radiation field. The dependance on the astrophysical parameters was not investigated. Very recently, similar models using the same Monte Carlo method were presented in Iqbal et al. (2014) for silicate surfaces. Those models also included the ER mechanism. The authors remain limited by the prohibitive computation time (several weeks) required by the kinetic Monte Carlo method when including temperature fluctuations. We study here this problem for both ER and LH in a wider range of environments, including PDRs and their high radiation fields, and study the effect induced on cloud structure and observable line intensities by introducing the computation of the fluctuation effect into full cloud simulations.

We propose an analytical approach of the joint fluctuations problem (temperature and surface coverage) based on the master equation, which takes the form of an integral equation. Its numerical resolution incurs a high computational cost, which grows with grain size. In the case of the ER mechanism, the absence of non-linear term in the chemistry allows a decomposition of the two-dimensional full master equation into two one-dimensional equations : a marginal master equation for the temperature fluctuations and an equation on the conditional average population (conditional on T). This makes the numerical computation much more tractable. In the case of the LH mechanism, such simplification is not possible. The computationally heavy full resolution is used to build and verify a fast and accurate approximation of the solution. The final method proposed here allows computation of the total formation rate with a computation time of the order of one minute.

In Sect. 2, we introduce the simple physical model that we use and the exact resolution method. In Sect. 3, approximations of the solution are constructed for both mechanisms. Section 4 presents the results of the numerical computation of the H2 formation rate using the full method for ER and the approximation for LH. Section 5 then shows how this computed effect affects the structure of the cloud in PDR simulations. Section 6 is our conclusion.

2. The model

2.1. Physical description

We use a simple physical model of H2 formation on grains to be able to solve the problem of the coupled fluctuations and to obtain an estimate of the importance of dust temperature fluctuations for H2 formation.

Our system is a spherical grain of radius a, density ρgr, mass

, and heat capacity C(T). Its

thermal state can be equivalently described by its temperature T or by its thermal energy

, and heat capacity C(T). Its

thermal state can be equivalently described by its temperature T or by its thermal energy

1.

For polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), we define the size a as the equivalent size of

a sphere of the same mass (see Compiègne et al.

2011).

1.

For polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), we define the size a as the equivalent size of

a sphere of the same mass (see Compiègne et al.

2011).

We consider two groups of phenomena:

-

Interaction with the radiation field through photon absorption and emission, which are both described as discrete events.

-

Adsorption of H atoms of the gas onto the surface of the grain and H2 formation on the surface (physisorption and chemisorption are considered separately, as are the two corresponding H2 formation mechanisms).

2.1.1. Photon absorption and emission

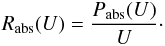

Under an ambient isotropic radiation field of specific intensity IU(U)

in W m-2 J-1

sr-1 (in this article, U always denotes a photon

energy), the power received by the grain at a certain photon energy U is Pabs(U) =

4π2a2Qabs(U)

IU(U),

where Qabs(U) is the

absorption efficiency coefficient of the grain at energy U. In later parts of the

paper, we are interested in transition rates between states of the grain. The rate of

photon absorptions at this energy U is simply  We postulate that the grain emits according

to a modified black body law with a specific intensity Qabs(U)

BU(U,T),

where BU(U,T)

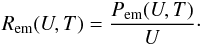

is the usual black body specific intensity. The power emitted at energy U is Pem(U,T) =

4π2a2Qabs(U)

BU(U,T)

and the photon emission rate is

We postulate that the grain emits according

to a modified black body law with a specific intensity Qabs(U)

BU(U,T),

where BU(U,T)

is the usual black body specific intensity. The power emitted at energy U is Pem(U,T) =

4π2a2Qabs(U)

BU(U,T)

and the photon emission rate is  These events, which are supposed to occur

as Poisson processes, cause fluctuations of the temperature. We treat these fluctuations

exactly in Sect. 2.2.

These events, which are supposed to occur

as Poisson processes, cause fluctuations of the temperature. We treat these fluctuations

exactly in Sect. 2.2.

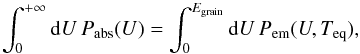

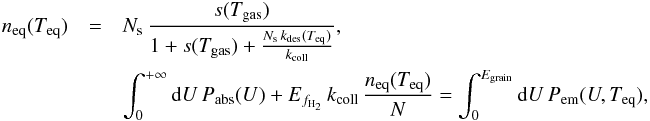

When neglecting these fluctuations, the equilibrium temperature Teq of the

grain is defined as balancing the instantaneous emitted and absorbed powers

(1)where the upper bound on the right hand

side accounts for the finite total energy of a grain. This upper cutoff of emission

frequencies can become very important for small cold grains, effectively stopping their

cooling.

(1)where the upper bound on the right hand

side accounts for the finite total energy of a grain. This upper cutoff of emission

frequencies can become very important for small cold grains, effectively stopping their

cooling.

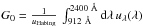

In the following, we use a standard interstellar radiation field (Mathis et al. 1983) and apply a scaling factor χ to the UV component of

the field. We measure the UV intensity of those fields using the usual

, where uHabing = 5.3 ×

10-15 J m-3.

, where uHabing = 5.3 ×

10-15 J m-3.

The dust properties (C(T), Qabs(U) and ρ) are taken from Compiègne et al. (2011). We consider PAHs, amorphous carbon grains, and silicates dust populations and use the properties used in this reference (see references therein, in their Appendix A) for each of those populations.

2.1.2. Surface chemistry via Langmuir-Hinshelwood mechanism

We first consider the physisorption-based LH mechanism. In this mechanism, atoms bind to the grain surface due to Van der Waals interactions, leading to the so-called physisorption. These weakly bound atoms are able to migrate from site to site. Formation can then occur when two such migrating atoms meet.

Real grain surfaces are irregular, and binding properties vary from site to site due to

surface defects. To keep the model simple enough to allow a detailed modeling of

temperature fluctuations, we assume identical binding sites uniformly distributed on the

grain surface. The number of sites is  , where ds is the

typical distance between sites. We take ds = 0.26 nm as in Le Bourlot et al. (2012). We assume the physisorption

sites to be simple potential wells of depth Ephys without barrier.

, where ds is the

typical distance between sites. We take ds = 0.26 nm as in Le Bourlot et al. (2012). We assume the physisorption

sites to be simple potential wells of depth Ephys without barrier.

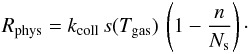

Atoms from a gas at temperature Tgas collide with the grain at a rate

kcoll =

πa2n(H)

vth, where

is the thermal velocity. We call

s(Tgas) the sticking

probability and discuss later our choice for this function. The probability to land on

an empty site is

is the thermal velocity. We call

s(Tgas) the sticking

probability and discuss later our choice for this function. The probability to land on

an empty site is  and the physisorption rate is thus

and the physisorption rate is thus

We assume that gas atoms falling on an

occupied site are never rejected and react with the adsorbed atom to form a

H2 molecule,

which is immediately desorbed by the formation energy. This assumption of

Eley-Rideal-like reaction for physisorbed atoms is similarly made in the model of Cuppen et al. (2006) with the difference that they do

not consider desorption at the formation of the new molecule. This direct Eley-Rideal

process is expected to have a large cross section at temperatures relevant to the

interstellar medium (Martinazzo & Tantardini

2006), and it is thus a reasonable assumption to assume that it dominates over

rejection. To estimate the influence of this assumption on our results, we computed the

contribution of this direct ER-like reaction process to the total mean formation rate

through physisorption and found it to be a negligible fraction (always less than 1% of

the total average formation rate). Despite the very small contribution of this

Eley-Rideal-like process to the physisorption-based formation rate in our model, we keep

calling the physisorption-based mechanism LH mechanism to distinguish it from the

chemisorption-based ER mechanism.

We assume that gas atoms falling on an

occupied site are never rejected and react with the adsorbed atom to form a

H2 molecule,

which is immediately desorbed by the formation energy. This assumption of

Eley-Rideal-like reaction for physisorbed atoms is similarly made in the model of Cuppen et al. (2006) with the difference that they do

not consider desorption at the formation of the new molecule. This direct Eley-Rideal

process is expected to have a large cross section at temperatures relevant to the

interstellar medium (Martinazzo & Tantardini

2006), and it is thus a reasonable assumption to assume that it dominates over

rejection. To estimate the influence of this assumption on our results, we computed the

contribution of this direct ER-like reaction process to the total mean formation rate

through physisorption and found it to be a negligible fraction (always less than 1% of

the total average formation rate). Despite the very small contribution of this

Eley-Rideal-like process to the physisorption-based formation rate in our model, we keep

calling the physisorption-based mechanism LH mechanism to distinguish it from the

chemisorption-based ER mechanism.

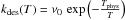

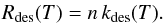

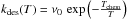

Surface atoms can then evaporate. The adsorbed atoms are assumed to be thermalized at

the grain temperature and must overcome the well energy Ephys. We take

this desorption rate for one atom to be of the form

, where T is the grain

temperature, Tphys =

Ephys/k, and

ν0 is a typical vibration frequency

taken as

, where T is the grain

temperature, Tphys =

Ephys/k, and

ν0 is a typical vibration frequency

taken as  with a typical size d0 = 0.1 nm

(Hasegawa et al. 1992). The total desorption

rate on the grain is then

with a typical size d0 = 0.1 nm

(Hasegawa et al. 1992). The total desorption

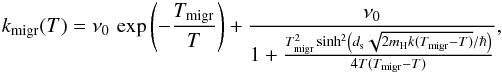

rate on the grain is then  To migrate from site to site, an atom must

cross a barrier of height Emigr. It can do so by thermal hopping

or by tunneling for which we use the formula from Le

Bourlot et al. (2012). The migration rate for one physisorbed atom is thus

To migrate from site to site, an atom must

cross a barrier of height Emigr. It can do so by thermal hopping

or by tunneling for which we use the formula from Le

Bourlot et al. (2012). The migration rate for one physisorbed atom is thus

where Tmigr =

Emigr/k.

where Tmigr =

Emigr/k.

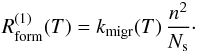

The main formation process is the meeting of two physisorbed atoms during a migration

event. In a simple approximation (see Lohmar & Krug

2006; Lohmar et al. 2009, for a more

detailed treatment of the sweeping rate), we take this formation rate to be

We also take direct reaction of a

physisorbed atom with a gas atom in an ER-like mechanism into account, with a rate

We also take direct reaction of a

physisorbed atom with a gas atom in an ER-like mechanism into account, with a rate

This term is only significant for very low

dust temperatures (a few K,

depending on the collision rate with gas atoms).

This term is only significant for very low

dust temperatures (a few K,

depending on the collision rate with gas atoms).

We assume immediate desorption of the newly formed molecule because of the high formation energy compared to the binding energy, thus making a similar assumption to recent models (Iqbal et al. 2012; Le Bourlot et al. 2012). Experimental results indicate that a small fraction of the formed molecules may stay on the surface at formation (Katz et al. 1999; Perets et al. 2007). Theoretical studies (Morisset et al. 2004a, 2005) suggest that even when the formed molecule does not desorb immediately at formation, it desorbs after a few picoseconds by interacting with the surface due to its high internal energy. It is thus equivalent to immediate desorption compared to the timescales of the other events.

Model parameters for physisorption.

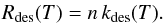

If the temperature fluctuations are neglected, an equilibrium surface population can be

computed using the equilibrium rate equation  (the factor of 2 comes from the fact

that one formation through migration event reduces the population by two). We find

(the factor of 2 comes from the fact

that one formation through migration event reduces the population by two). We find

![\begin{eqnarray} n_{\rm eq}(T)&=&\frac{\left(1+s(T_{\mathrm{gas}})\right)k_{\mathrm{coll}}}{4\, k_{\mathrm{mig}}(T)}\left(1+\frac{N_{\mathrm{s}}\, k_{\mathrm{des}}(T)}{k_{\mathrm{coll}}(1+s(T_{\mathrm{gas}}))}\right) \notag\\&&\quad\times \left[\sqrt{1+\frac{8N_{\mathrm{s}}\, k_{\mathrm{mig}}(T)\, s(T_{\mathrm{gas}})}{k_{\mathrm{coll}}(1+s(T_{\mathrm{gas}}))^{2}}\frac{1}{\left(1+\frac{N_{\mathrm{s}}\, k_{\mathrm{des}}(T)}{k_{\mathrm{coll}}(1+s(T_{\mathrm{gas}}))}\right)^{2}}}-1\right],\label{eq:n_eq_LH} \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2014/09/aa22101-13/aa22101-13-eq64.png) (2)and the corresponding equilibrium formation

rate on one grain at temperature T is

(2)and the corresponding equilibrium formation

rate on one grain at temperature T is ![\begin{equation} r_{\mathrm{H}_{2}}^{\mathrm{eq}}(T)=k_{\mathrm{migr}}(T)\frac{[n_{\mathrm{eq}}(T)]^{2}}{N_{\mathrm{s}}}+k_{\mathrm{coll}}\frac{n_{\mathrm{eq}}(T)}{N_{\mathrm{s}}}\cdot\label{eq:rH2_eq_LH} \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2014/09/aa22101-13/aa22101-13-eq65.png) (3)Once again this expression is not valid for

a fluctuating temperature and the full calculation is described in the next Sect. 2.2.

(3)Once again this expression is not valid for

a fluctuating temperature and the full calculation is described in the next Sect. 2.2.

For the binding and migration energies, we use the values given in Table 1 associated to different substrates.

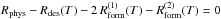

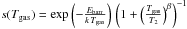

Many different expressions of the sticking coefficient have been given in the

literature. For simplicity, we use the same sticking probability for the

physisorption-based LH mechanism and the chemisorption-based ER mechanism, except for

the additional presence of a barrier in the ER case. We use the expression from Le Bourlot et al. (2012):

using T2 = 464 K and

β = 1.5,

which gives results close to the expression of Sternberg

& Dalgarno (1995).

using T2 = 464 K and

β = 1.5,

which gives results close to the expression of Sternberg

& Dalgarno (1995).

We also simply assume an equipartition of the formation energy among the kinetic energy of the newly formed molecule, its excitation energy, and the heating of the grain.

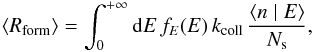

The total volumic H2 formation rate is often parametrized as

RH2

=

RfnHn(H)

to factor out the dependency to the atomic H abundance n(H) and to the dust abundance, which is

proportional to the total proton density nH, coming from the collision rate

between gas H atoms and dust

grains. The standard value of Rf is 3 × 10-17cm3

s-1. We also use the formation efficiency defined for one

grain as  , which represents the fraction of the

H atoms colliding with the

grain that are turned into H2.

, which represents the fraction of the

H atoms colliding with the

grain that are turned into H2.

2.1.3. Surface chemistry via Eley-Rideal mechanism

We also consider the chemisorption-based ER mechanism. The H atoms of the gas phase that hit the grain can bind to the surface by a covalent bond after overcoming a repulsive barrier. This process is called chemisorption (see for instance Jeloaica & Sidis 1999). Once chemisorbed, the atoms either evaporate and return to the gas phase, or react if another gas H atom lands on the same adsorption site.

We assume the chemisorption sites to be similarly distributed with the same inter-site distance ds = 0.26 nm. Each site is a potential well of depth Echem and is separated from the free state by a potential barrier of height Ebarr.

The collision rate kcoll is the same as in the LH case.

However, we have to take the presence of the chemisorption barrier into acount in the

sticking coefficient. Following Le Bourlot et al.

(2012), we use a sticking probability  , where the second term accounts for

rebound of high energy atoms without sticking with Tbarr =

Ebarr/k = 300 K,

T2 =

464 K, and β = 1.5. The energy barrier for chemisorption on

perfect graphitic surfaces has been found to be of the order of 0.15−0.2 eV (but adsorption in para-dimer

configuration has a much lower barrier of 0.04 eV) (Sha

& Jackson 2002; Kerwin & Jackson

2008). As discussed in Le Bourlot et al.

(2012), the choice made here of a lower barrier for chemisorption is based on

the idea that real grain surfaces are not perfect flat surfaces like graphite, but

present a large number of defects. Surface defects are expected to induce a strongly

reduced barrier for chemisorption (Ivanovskaya et al.

2010; Casolo et al. 2013). Edge sites on

PAHs behave in a similar way (Bonfanti et al.

2011). Moreover, Mennella (2008) found

that chemisorption in aliphatic CH2,3 groups could also lead to efficient Eley-Rideal

formation with a very low chemisorption barrier.

, where the second term accounts for

rebound of high energy atoms without sticking with Tbarr =

Ebarr/k = 300 K,

T2 =

464 K, and β = 1.5. The energy barrier for chemisorption on

perfect graphitic surfaces has been found to be of the order of 0.15−0.2 eV (but adsorption in para-dimer

configuration has a much lower barrier of 0.04 eV) (Sha

& Jackson 2002; Kerwin & Jackson

2008). As discussed in Le Bourlot et al.

(2012), the choice made here of a lower barrier for chemisorption is based on

the idea that real grain surfaces are not perfect flat surfaces like graphite, but

present a large number of defects. Surface defects are expected to induce a strongly

reduced barrier for chemisorption (Ivanovskaya et al.

2010; Casolo et al. 2013). Edge sites on

PAHs behave in a similar way (Bonfanti et al.

2011). Moreover, Mennella (2008) found

that chemisorption in aliphatic CH2,3 groups could also lead to efficient Eley-Rideal

formation with a very low chemisorption barrier.

Finally, only atoms arriving on an empty adsorption site stick, corresponding to a

probability  , where n is the number of

chemisorbed atoms.

, where n is the number of

chemisorbed atoms.

Model parameters for chemisorption.

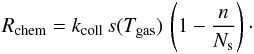

The chemisorption rate is thus  Atoms hitting an occupied site react with

the adsorbed atom to form a H2 molecule. Some theoretical studies show a very small

activation barrier of 9.2

meV (Morisset et al. 2004b)

for this reaction, but the existence of this barrier is under debate (Rougeau et al. 2011). To stay consistent with the

model of Le Bourlot et al. (2012) to which we

compare our results in Sect. 5, we neglect this

barrier compared to the stronger adsorption barrier. We found that including it in the

model reduces the formation efficiency by less than 10% in the range of gas temperatures where

the ER mechanism is important compared to the physisorption-based LH mechanism.

Atoms hitting an occupied site react with

the adsorbed atom to form a H2 molecule. Some theoretical studies show a very small

activation barrier of 9.2

meV (Morisset et al. 2004b)

for this reaction, but the existence of this barrier is under debate (Rougeau et al. 2011). To stay consistent with the

model of Le Bourlot et al. (2012) to which we

compare our results in Sect. 5, we neglect this

barrier compared to the stronger adsorption barrier. We found that including it in the

model reduces the formation efficiency by less than 10% in the range of gas temperatures where

the ER mechanism is important compared to the physisorption-based LH mechanism.

As the formation reaction releases 4.5

eV, which is much more than the binding energy, we assume that the

new molecule is immediately released in the gas. The formation rate is then

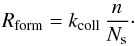

Last, chemisorbed atoms can evaporate. This

effect is usually negligible at typical grain temperatures, but the fluctuating

temperatures of small grains can easily make excursions into the domain where

evaporation is significant. The adsorbed atoms are supposed to be thermalized at the

grain temperature, and must overcome the well energy Echem. The

desorption process is similar to the LH case, and we take again

Last, chemisorbed atoms can evaporate. This

effect is usually negligible at typical grain temperatures, but the fluctuating

temperatures of small grains can easily make excursions into the domain where

evaporation is significant. The adsorbed atoms are supposed to be thermalized at the

grain temperature, and must overcome the well energy Echem. The

desorption process is similar to the LH case, and we take again

, where Tchem =

Echem/k, and

, where Tchem =

Echem/k, and

(with d0 = 0.1 nm).

The total desorption rate on the grain is then

(with d0 = 0.1 nm).

The total desorption rate on the grain is then  Theoretical studies find the chemisorption

energy on graphene to be in the range 0.67−0.9 eV (Sha & Jackson

2002; Lehtinen et al. 2004; Casolo et al. 2009). On small PAHs, Bonfanti et al. (2011) find binding energies in the

range 1−3 eV for edge sites

and in the range 0.5−1 eV

for non edge sites. In this overall range 5800 −35 000 K, we choose a low value of 7000 K

to estimate the maximum effect of temperature fluctuations on the ER mechanism.

Theoretical studies find the chemisorption

energy on graphene to be in the range 0.67−0.9 eV (Sha & Jackson

2002; Lehtinen et al. 2004; Casolo et al. 2009). On small PAHs, Bonfanti et al. (2011) find binding energies in the

range 1−3 eV for edge sites

and in the range 0.5−1 eV

for non edge sites. In this overall range 5800 −35 000 K, we choose a low value of 7000 K

to estimate the maximum effect of temperature fluctuations on the ER mechanism.

We sum up the model parameters in Table 2.

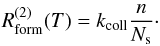

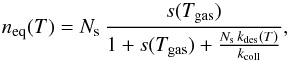

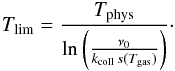

When neglecting the fluctuations of the grain temperature, we can calculate the

equilibrium surface population neq using the equilibrium rate

equation Rchem −

Rform −

Rdes(T) = 0, which

gives  (4)and the corresponding equilibrium formation

rate on one grain at temperature T is

(4)and the corresponding equilibrium formation

rate on one grain at temperature T is  (5)However, when temperature fluctuations are

taken into account, this equilibrium situation is not valid. The method we use to

calculate this effect is described in Sect. 2.2.

(5)However, when temperature fluctuations are

taken into account, this equilibrium situation is not valid. The method we use to

calculate this effect is described in Sect. 2.2.

The energy liberated from the formation reaction is split between the excitation and kinetic energy of the molecule and the heating of the grain. As in Le Bourlot et al. (2012), we take the results of Sizun et al. (2010) for the ER mechanism : 2.7 eV goes into the excitation energy of the molecule, 0.6 eV into its kinetic energy, and 1 eV is given to the grain.

We must note that the part of the formation energy given to the grain creates another coupling between surface population and grain temperature. This fraction of the formation energy (1 eV) is not completely negligible compared to photon energies. This additional retro-coupling between surface chemistry and temperature is ignored in the statistical calculation presented in this article. However, its effect on the equilibrium situation when neglecting fluctuations is evaluated in Appendix A. It is found to be negligible as the power given to the grain is usually much smaller that the radiative power it receives.

We can again define the formation parameter Rf as RH2 =

RfnHn(H)

and the formation efficiency for one grain as  .

.

2.2. Method

To take into account temperature fluctuations, we adopt a statistical point of view, and we describe the statistical properties of the fluctuating variables.

The necessary statistical information on our system is contained in the probability density function (PDF) f(X), giving the probability to find the system in the state X that is defined by the two variables E, the thermal energy of the grain (equivalent to its temperature T), and n, the number of adsorbed H atoms on its surface. The function f is thus the joint PDF in the two variables. As we treat our two formation mechanisms independently, n counts chemisorbed or physisorbed atoms depending on which mechanism we are discussing.

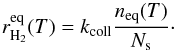

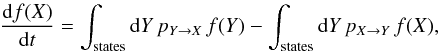

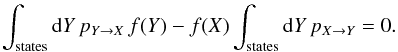

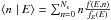

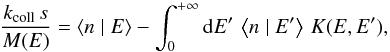

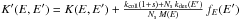

The time evolution of this PDF is governed by the master equation:

where pX →

Y is the transition rate from state

X to

Y. This

equation expresses that the probability of being in a given state varies in time due to

the imbalance between the rate of arrivals and the rate of departures. In a stationary

situation, the two rates, which we call as the gain and loss rates respectively, must

compensate each other.

where pX →

Y is the transition rate from state

X to

Y. This

equation expresses that the probability of being in a given state varies in time due to

the imbalance between the rate of arrivals and the rate of departures. In a stationary

situation, the two rates, which we call as the gain and loss rates respectively, must

compensate each other.

We are thus looking for a solution to the equation  Two different kinds of transitions occur: the

emission or absorption of a photon, which changes only the thermal energy E of the grain, and the

adsorption, desorption, or reaction of hydrogen atoms, which changes only the surface

population n.

The two variables are only coupled by the transition rates for the chemical events, which

depend on the grain temperature. The population fluctuations are thus entirely driven by

the temperature fluctuations with no retroactions (as mentioned before we neglect grain

heating by the formation process).

Two different kinds of transitions occur: the

emission or absorption of a photon, which changes only the thermal energy E of the grain, and the

adsorption, desorption, or reaction of hydrogen atoms, which changes only the surface

population n.

The two variables are only coupled by the transition rates for the chemical events, which

depend on the grain temperature. The population fluctuations are thus entirely driven by

the temperature fluctuations with no retroactions (as mentioned before we neglect grain

heating by the formation process).

As the transition mechanisms modify only one variable at a time, we split each of the

gain and loss terms into two parts, respectively for photon processes (affecting only

E) and for

surface chemical processes (affecting only n),  (6)with

(6)with  where we have simplified the notations for

the transition rates as transitions only affect one variable at a time and the transitions

affecting E

(photon absorptions or emissions) have rates that are independent of n.

where we have simplified the notations for

the transition rates as transitions only affect one variable at a time and the transitions

affecting E

(photon absorptions or emissions) have rates that are independent of n.

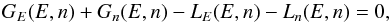

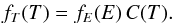

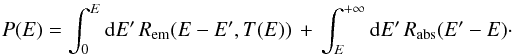

We now first show how the thermal energy marginal PDF fE(E) (or the equivalent temperature PDF fT(T)) can be derived from our formalism, which reduces to equations similar to previous works (Desert et al. 1986; Draine & Li 2001). We then show how the formation rates in the LH case and in the ER case can be derived.

2.2.1. Thermal energy PDF

Summing Eq. (6) over all

n values,

we obtain  (7)where fE(E) = ∑

nf(E,n)

is the marginal PDF for the single variable E. The marginal PDF fE can easily be

converted into a grain temperature PDF fT through the

relationship

(7)where fE(E) = ∑

nf(E,n)

is the marginal PDF for the single variable E. The marginal PDF fE can easily be

converted into a grain temperature PDF fT through the

relationship  We thus obtain an independent master

equation for the temperature fluctuations.

We thus obtain an independent master

equation for the temperature fluctuations.

Detailing the transition rates in Eq. (7), we can rewrite it as  (8)This equation is an eigenvector equation

for the linear integral operator defined by the right-hand side: fE(E) = ℒ [

fE ]

(E). A stationary PDF for the grain thermal energy

is a positive and normalized eigenvector of this operator for the eigenvalue

1. The existence and

unicity of this eigenvector is proven in Appendix B. Moreover, the other eigenvalues all have real parts that are lower than

1 (see Appendix B). We can thus converge toward the solution by

building a sequence ℒn [ fE

] (the exponent refers to operator composition) from an initial

guess. We solve this equation numerically by choosing an energy grid {Ei} and solving for

piecewise linear functions on this grid.

(8)This equation is an eigenvector equation

for the linear integral operator defined by the right-hand side: fE(E) = ℒ [

fE ]

(E). A stationary PDF for the grain thermal energy

is a positive and normalized eigenvector of this operator for the eigenvalue

1. The existence and

unicity of this eigenvector is proven in Appendix B. Moreover, the other eigenvalues all have real parts that are lower than

1 (see Appendix B). We can thus converge toward the solution by

building a sequence ℒn [ fE

] (the exponent refers to operator composition) from an initial

guess. We solve this equation numerically by choosing an energy grid {Ei} and solving for

piecewise linear functions on this grid.

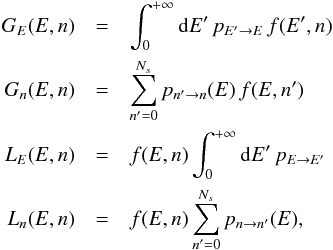

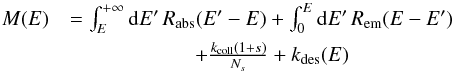

2.2.2. Eley-Rideal mechanism

We first present the method for the ER mechanism as the linearity of the chemical rates in n simplifies the problem significantly. We can avoid directly solving the full master equation for the joint PDF in two variables (Eq. (6)).

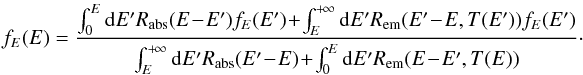

We are interested in the average ER formation rate

Knowing fE(E),

we can rewrite it as:

Knowing fE(E),

we can rewrite it as:  where

where

is the conditional expectation of the

surface population at thermal energy E. It is by definition the expected value (or

ensemble average) of the surface population of a grain, knowing that

this grain has thermal energy E. Multiplying Eq. (6) by n and summing over all n values gives the

equation governing this quantity ⟨n | E⟩,

is the conditional expectation of the

surface population at thermal energy E. It is by definition the expected value (or

ensemble average) of the surface population of a grain, knowing that

this grain has thermal energy E. Multiplying Eq. (6) by n and summing over all n values gives the

equation governing this quantity ⟨n | E⟩,  (9)where

(9)where  and

and ![\begin{eqnarray*} K(E,E')=\begin{cases} {\displaystyle \frac{f_{E}(E')\, R_{\mathrm{abs}}(E-E')}{f_{E}(E)\, M(E)}} & \mathrm{if}\qquad E'\in[0,E]\\ \\ {\displaystyle \frac{f_{E}(E')\, R_{\mathrm{em}}(E'-E,T(E'))}{f_{E}(E)\, M(E)}} & \mathrm{if}\qquad E'>E. \end{cases} \end{eqnarray*}](/articles/aa/full_html/2014/09/aa22101-13/aa22101-13-eq128.png) After a similar discretization, this is a

linear system of equations. However, while being nonsingular, it converges exponentially

fast toward a singular system as the grain size a grows, making standard

numerical procedures unusable.

After a similar discretization, this is a

linear system of equations. However, while being nonsingular, it converges exponentially

fast toward a singular system as the grain size a grows, making standard

numerical procedures unusable.

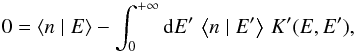

To avoid this problem, we rewrite this equation. Multiplying by M(E)fE(E)

and integrating it over E yields ![\begin{equation} k_{\mathrm{coll}}\, s=\int_{0}^{+\infty}{\rm{d}}E'\left[\frac{k_{\mathrm{coll}}(1+s)}{N_{s}}+k_{\mathrm{des}}(E')\right]f_{E}(E')\,\left\langle n\mid E'\right\rangle .\label{eq:norm_ER} \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2014/09/aa22101-13/aa22101-13-eq130.png) (10)Dividing again by M(E) and

subtracting it from the initial equation gives

(10)Dividing again by M(E) and

subtracting it from the initial equation gives  (11)where

(11)where

. This is again an eigenvector equation

for the eigenvalue 1 of a

linear integral operator. After discretization, we numerically compute this eigenvector

and use Eq. (10) as a normalization

condition. This procedure proved to work on the entire range of relevant grain sizes.

. This is again an eigenvector equation

for the eigenvalue 1 of a

linear integral operator. After discretization, we numerically compute this eigenvector

and use Eq. (10) as a normalization

condition. This procedure proved to work on the entire range of relevant grain sizes.

2.2.3. Langmuir-Hinshelwood mechanism

For the LH mechanism, the formation rate contains a quadratic term. When trying to

apply a similar method to the LH mechanism, the equivalent of Eq. (11) is then an infinite system of equations

on the conditional moments of the population ⟨n | E⟩,

,

,  We thus directly solve the main master

equation (Eq. (6)), despite the

computational burden.

We thus directly solve the main master

equation (Eq. (6)), despite the

computational burden.

Writing explicitly the transition rates in Eq. (6), we get ![\begin{eqnarray} \label{eq:LH-master-raw} 0&=&\int_{0}^{E}{\rm{d}}E'\, R_{\rm abs}(E-E')\, f(E',n) \notag\\ &&\quad +\int_{E}^{+\infty}{\rm{d}}E'\, R_{\rm em}(E'-E,T(E'))\, f(E',n) \notag\\ &&\quad +f(E,n-1)k_{\rm coll}s(T_{\rm gas})\left(1-\frac{n-1}{N_{\rm s}}\right) \notag\\ &&\quad +f(E,n+1)\left[(n+1)\, k_{\rm des}(T)+k_{\rm coll}\frac{n+1}{N_{\rm s}}\right]\notag\\ &&\quad +f(E,n+2)k_{\rm mig}(T)\frac{(n+2)(n+1)}{N_{\rm s}} \notag\\ &&\quad -\left[\int_{E}^{+\infty}{\rm{d}}E'\, R_{\mathrm{\rm abs}}(E'-E)+\int_{0}^{E}{\rm{d}}E'\, R_{\mathrm{\rm em}}(E-E')\right]\, f(E,n) \notag\\ &&\quad -f(E,n)\left[k_{\rm coll}s(T_{\rm gas})\left(1-\frac{n}{N_{\rm s}}\right)+n\, k_{\rm des}(T)+k_{\rm coll}\frac{n}{N_{\rm s}}\right. \notag\\ &&\quad \left.+k_{\rm mig}(T)\frac{n(n-1)}{N_{\rm s}}\right], \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2014/09/aa22101-13/aa22101-13-eq137.png) (12)where, as boundary conditions, all

expressions n −

1, n +

1 and n +

2 are implicitly taken to be 0 if they become negative or greater

than Ns.

(12)where, as boundary conditions, all

expressions n −

1, n +

1 and n +

2 are implicitly taken to be 0 if they become negative or greater

than Ns.

We define the total loss rate as  the integral operator (for photon induced

transitions) as

the integral operator (for photon induced

transitions) as &=&\int_{0}^{E}{\rm{d}}E'\, R_{\rm abs}(E-E')\, f(E',n)\\ &&\quad +\int_{E}^{+\infty}{\rm{d}}E'\, R_{\rm em}(E'-E,T(E'))\, f(E',n), \end{eqnarray*}](/articles/aa/full_html/2014/09/aa22101-13/aa22101-13-eq143.png) and the discrete jump operator (for

chemical transitions) as

and the discrete jump operator (for

chemical transitions) as &=& f(E,n-1)k_{\rm coll}s(T_{\rm gas})\left(1-\frac{n-1}{N_{\rm s}}\right)\\ &&\quad +f(E,n+1)\left[(n+1)\, k_{\rm des}(T)+k_{\rm coll}\frac{n+1}{N_{\rm s}}\right]\\ &&\quad +f(E,n+2)k_{\rm mig}(T)\frac{(n+2)(n+1)}{N_{\rm s}}\cdot \end{eqnarray*}](/articles/aa/full_html/2014/09/aa22101-13/aa22101-13-eq144.png) We can then rewrite Eq. (12)in a simplified form as

We can then rewrite Eq. (12)in a simplified form as +\mathcal{J}[f](E,n)\right].\label{eq:LH-master-simple} \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2014/09/aa22101-13/aa22101-13-eq145.png) (13)This is an eigenvector equation for the

eigenvalue 1, which is

formally similar to Eq. (8). For the

same reasons as previously, we expect the operator defined by the right hand side to

have all its eigenvalues with real parts that are strictly lower than 1, except the

eigenvalue 1, which is simple. We can thus find the solution by iterating the

application of the operator from an initial guess.

(13)This is an eigenvector equation for the

eigenvalue 1, which is

formally similar to Eq. (8). For the

same reasons as previously, we expect the operator defined by the right hand side to

have all its eigenvalues with real parts that are strictly lower than 1, except the

eigenvalue 1, which is simple. We can thus find the solution by iterating the

application of the operator from an initial guess.

The equation is solved numerically using this iterative procedure. The computation time is found to explode when increasing the grain size a. In addition to the number of possible values of n increasing as a2, the number of iterations necessary to converge toward the stationary solution is also found to quickly increase with a. Grouping the values of n in bins to reduce the matrix size does not solve the problem, as the reduction of the computation time due to the smaller matrices is found to be balanced by a roughly equivalent increase in the number of iterations necessary to converge to a given stationarity threshold.

We can thus only use this method up to moderate grain sizes (~20 nm with 2 days of computation). In later sections, we see, however, that this is sufficient to observe the range of sizes for which the temperature fluctuations significantly impact the chemistry. In addition, a much quicker yet sufficiently accurate approximation is presented in Sect. 3.

3. Approximations

In this section, we construct fast approximations of the formation rate based on simple physical arguments and compare their results with those of the exact method presented in Sect. 2.2. An approximation is especially necessary for the LH mechanism to avoid the prohibitive computational cost of the exact method. A similar approximation is given for completeness for the ER mechanism. Those methods assume the temperature PDF fT(T) to be known. It can be computed, for instance, by the method described in Sect. 2.2.1.

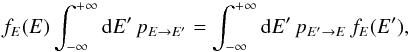

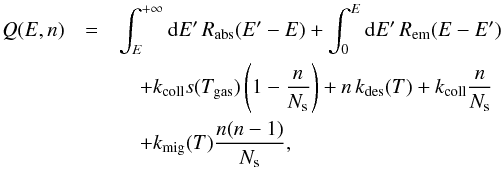

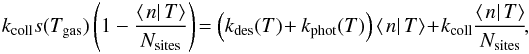

3.1. Approximation of the Langmuir-Hinshelwood formation rate

We build our method around an approximation of ⟨n|T⟩, the average population on the grains that are at a given temperature T. We first write a balance equation for this average population, taking into account both chemical processes (changing only the grain’s population), and grains leaving or reaching this temperature T.

We first consider the chemical processes. Those are described in Sect. 2.1.2:

-

The grain can gain atoms through adsorption (average rate

).

). -

The grain can lose atoms through desorption (rate ⟨n|T⟩kdes(T)).

-

The grain can lose atoms through LH reaction, a term we express later. For now, let us write it as

. We discuss this term in depth

below.

. We discuss this term in depth

below. -

The grain can lose atoms through direct ER reaction (rate

).

).

On the other hand, the grain can also leave the temperature T. At equilibrium, the rate at which grains leave the state T is exactly balanced by the rate of arrivals from other states. The net effect on the conditional average ⟨n|T⟩ can be a loss or a gain depending on whether the average population of the grains arriving from other states is higher or lower than ⟨n|T⟩. In general, noting kleave(T), the rate at which grains leave the state T, and ⟨narrivals|T⟩, the average population on grains arriving in state T, the net gain rate is kleave(T)(⟨narrivals|T⟩ − ⟨n|T⟩).

Up to now, no approximation has been made.

As we expected high temperatures states, where desorption dominates all other processes, to have negligible formation and extremely low average population, we focus our approximation on a low temperature regime.

We want to estimate what fraction of the grains leaving state T will come back bare (or

with a negligible population compared to ⟨n|T⟩). We make the following

approximation: grains leaving T to reach the regime where desorption dominates,

come back with no population. Fluctuations that do not reach the desorption regime leave

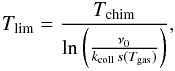

the surface population unchanged. We define the temperature Tlim that

delimits these regimes as the temperature at which the desorption rate for one atom

becomes equal to the adsorption rate for the grain (we call Elim the

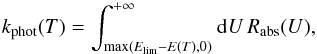

corresponding thermal energy):  We thus define

We thus define  (14)the rate at which grains leave state

T to reach

a temperature above the limit. The net loss rate due to fluctuations is then

kphot(T)⟨n|T⟩.

(14)the rate at which grains leave state

T to reach

a temperature above the limit. The net loss rate due to fluctuations is then

kphot(T)⟨n|T⟩.

We have thus obtained a rate equation for the conditional average population at

temperature T:  (15)This equation is in closed form if we can

express

(15)This equation is in closed form if we can

express  as a function of ⟨n|T⟩

only. We distinguish the two regimes ⟨n|T⟩ > 1 and ⟨n|T⟩ <

1. From now on, we simplify the notations by noting s =

s(Tgas).

as a function of ⟨n|T⟩

only. We distinguish the two regimes ⟨n|T⟩ > 1 and ⟨n|T⟩ <

1. From now on, we simplify the notations by noting s =

s(Tgas).

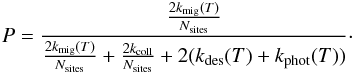

3.1.1. Regime with ⟨n|T⟩ > 1

In this regime, we assume that the discrete nature of the number of surface atoms is

negligible and treat this variable as continuous. We then have

. We also know that when ⟨n|T⟩ ≫

1, direct ER reaction is likely to dominate so that a precise

determination of the LH reaction rate is not necessary. We thus make the simple

approximation ⟨n2|T⟩ =

⟨n|T⟩2. Using this

approximation in Eq. (15), we then get

. We also know that when ⟨n|T⟩ ≫

1, direct ER reaction is likely to dominate so that a precise

determination of the LH reaction rate is not necessary. We thus make the simple

approximation ⟨n2|T⟩ =

⟨n|T⟩2. Using this

approximation in Eq. (15), we then get

![\begin{eqnarray} \left\langle \left.n\right|T\right\rangle &=&\frac{1+s}{4}\frac{k_{\rm coll}}{k_{\rm mig}(T)}\left(1+\frac{N_{\rm sites}(k_{\rm des}(T)+k_{\rm phot}(T))}{k_{\rm coll}(1+s)}\right)\notag\\ &&\quad \times\left[\sqrt{1 \! + \! \frac{8s}{(1+s)^{2}}\frac{k_{\rm mig}(T)}{k_{\rm coll}}\frac{N_{\rm sites}}{\left(1+\frac{N_{\rm sites}(k_{\rm des}(T)+k_{\rm phot}(T))}{k_{\rm coll}(1+s)}\right)^{2}}}-1\right]\cdot \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2014/09/aa22101-13/aa22101-13-eq169.png) (16)If this results becomes smaller than

1, we switch to the other

regime.

(16)If this results becomes smaller than

1, we switch to the other

regime.

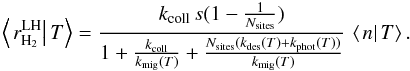

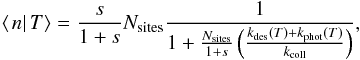

3.1.2. Regime with ⟨n|T⟩ < 1

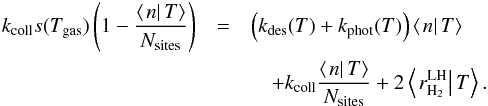

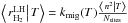

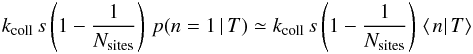

In this regime, discretisation effects are very important. Formation is dominated by LH reaction, which can only happen if two atoms are present on the grain at the same time. We use reasoning that is similar to the modified rate equation approach developed by Garrod (2008).

As the average population is low, we can make the approximation ⟨n|T⟩ ≃

p(n = 1 | T),

where the right hand side is the conditional probability of having one surface atom

knowing that the temperature is T. The LH formation rate can then be computed the

following way. The formation rate is the rate at which gas atoms fall on a grain that

already had one adsorbed atom AND reaction occurs before any other process removes one

of the atoms. The first part of the sentence gives a rate

using the previous approximation. Once we

have two atoms on the grain, the probability that they react before anything else

removes one atom is

using the previous approximation. Once we

have two atoms on the grain, the probability that they react before anything else

removes one atom is  This gives

This gives

We inject this expression in Eq. (15)and finally find the solution for this

regime:

We inject this expression in Eq. (15)and finally find the solution for this

regime:  (17)

(17)

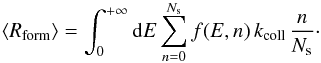

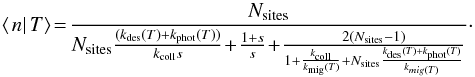

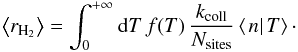

3.1.3. Total formation rate

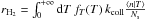

The total formation rate is then computed by integrating over the temperature PDF

f(T) and distinguishing the two

regimes:  (18)where Tswitch is the

temperature at which ⟨n|T⟩ becomes <1 (⟨n|T⟩ >

1 for T<Tswitch, and

⟨n|T⟩

< 1 for T>Tswitch).

(18)where Tswitch is the

temperature at which ⟨n|T⟩ becomes <1 (⟨n|T⟩ >

1 for T<Tswitch, and

⟨n|T⟩

< 1 for T>Tswitch).

This approximation is compared to the exact method of Sect. 2.2.3 in Appendix C. It is found to give a very accurate estimate of the total average formation rate (within at most 6%). This approximation is used in all results shown in the following sections as the exact method is not practically usable.

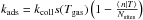

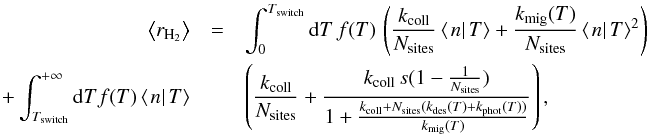

3.2. Approximation of the Eley-Rideal formation rate

A similar approximation can be constructed in the case of the ER mechanism. We again

write a rate equation for the conditional average ⟨n|T⟩,

including a fluctuation loss term. We use the same approximation for this loss term with

the limiting temperature being  and the loss rate being kphot(T)⟨n|T⟩

with kphot(T) as defined as

previously by Eq. (14). The resulting rate

equation is then directly obtained in closed form:

and the loss rate being kphot(T)⟨n|T⟩

with kphot(T) as defined as

previously by Eq. (14). The resulting rate

equation is then directly obtained in closed form:  and no further approximation is needed. The

solution is

and no further approximation is needed. The

solution is  and the average H2 formation rate can then be

computed as

and the average H2 formation rate can then be

computed as  A comparison of this method with the exact

result is also performed in Appendix C. However, as

the exact method is easily tractable, the approximation is not used in the results

presented in the rest of this article.

A comparison of this method with the exact

result is also performed in Appendix C. However, as

the exact method is easily tractable, the approximation is not used in the results

presented in the rest of this article.

4. Results

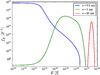

The method described in the previous two sections was implemented as a stand alone code called Fredholm. The temperature PDF is computed using the exact method of Sect. 2.2.1 and the ER formation rate using the exact method of Sect. 2.2.2, while we use the approximation presented in Sect. 3 for the LH formation rate. This code is now used to study the effect of the temperature fluctuations on the formation rate and the influence of the external conditions (gas conditions and radiation field). We first present a few results on the temperature PDFs before presenting the results on H2 formation by the ER and LH mechanisms.

|

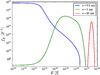

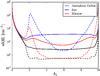

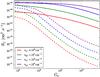

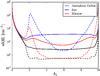

Fig. 1 Dust thermal energy PDFs for three grain sizes (amorphous carbon grains under a radiation field with G0 = 120). |

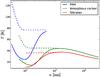

|

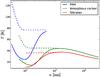

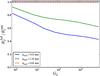

Fig. 2 Equilibrium temperature (dashed line) and actual average temperature (solid line), as a function of the grain size for the three types of grains (radiation field G0 = 120). |

4.1. Dust temperature probability density functions and grain emission

The thermal energy PDFs that we compute are shown in Fig. 1, which highlights the change of shape as we go from small grains to bigger grains. For small sizes, most of the grains are in the lowest energy states (the non-zero limit at zero energy can be easily derived from the master equation), while the high energy tail extends very far (the abrupt cut around 2 × 10-18 J is due to the Lyman cutoff present in the radiation field). As we go to bigger grains, the fraction of grains in the low energy plateau decreases, and the PDF takes a more peaked form but keeps a clear asymmetry. For the bigger sizes, the PDF becomes very sharp around its maximum and its relative width decreases towards zero, but the shape remains asymmetrical and could be asymptotically log-normal.

As expected, the average temperature converges toward the usual equilibrium temperature at large grain sizes but is significantly lower at small sizes, as shown in Fig. 2. High temperature grains have a much higher contribution to the average energy balance through their high emissivity. Thus, a very low fraction of high temperature grains is sufficient to lower the average temperature of the PDF compared to the equilibrium temperature. The temperature increase at very low grain sizes, which we can see on both the equilibrium and average temperatures, is due to the property that the smallest sizes have decreased cooling efficiency (as they cannot emit photons with higher energies than their own internal energy, their emission spectrum is reduced).

This part of the computation has been done before (Desert et al. 1986; Draine & Li 2001) and especially in the DustEM code (see Compiègne et al. 2011) to compute the infrared emission of dust. We checked the results of our code, which is named Fredholm, by comparing both the temperature PDFs, and the derived grain emissivity to the public DustEM code. We found a good agreement between the results, and despite small differences in the temperature PDFs (due mainly to the continuous cooling approximation in DustEM), the final emissivities are extremely close. Figure 3 shows the final comparison on a dust population corresponding to Compiègne et al. (2011) with PAHs, small carbonaceous grains, large carbonaceous grains, and large silicate grains.

|

Fig. 3 Local dust emissivity (emitted power per unit of volume) as a function of wavelength for a dust population corresponding to Compiègne et al. (2011) under a radiation field with G0 = 100. We compare our code, Fredholm, with DustEM. |

|

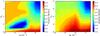

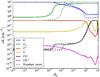

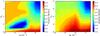

Fig. 4 Formation efficiency (LH mechanism) on one grain (carbonaceous) as a function of size for different radiation field intensities (in a gas at nH = 104 cm-3, T = 100 K). Solid lines: full computation. Dashed line: equilibrium rate equation results. The binding and barrier energies correspond to ices. |

4.2. H2 formation rate: LH mechanism

We apply the approximation method described in Sect. 3 to compute the H2 formation rate on physisorption sites. The results presented here concern unshielded gas in which the equilibrium rate equation method gives very inefficient LH formation rate due to high dust temperatures (i.e., PDR edges). For results in a more shielded gas, see Sect. 5 describing the coupling with full cloud simulations.

The results shown in this section use binding and barrier energies corresponding to either ices or amorphous carbon surfaces (see Table 1) as specified for each figure. Silicates have intermediate values and are thus not shown here. On the other hand, the optical and thermal properties of the grains are those of amorphous carbon grains.

We first show results for ice surfaces. Figure 4 shows the formation efficiency on one carbonaceous grain as a function of the grain size under various radiation field intensities and compares the equilibrium rate equation method with our estimation of the fluctuation effects. The results for small grains are different by several orders of magnitude; the method presented here giving a much more efficient formation. For large grains, the two methods converge as expected.

To understand those differences, we show how the temperature of a 3 nm dust grain is distributed compared to

the formation efficiency domain in Fig. 5. We show

both the efficiency curve that would be obtained from an equilibrium computation without

fluctuations (dashed line) and the true conditional mean efficiency

(solid line), for fluctuating grains when

they are at the given temperature T. We see two different effects caused by the

fluctuations. First, the efficiency domain is reduced in both range and maximum value.

This occurs because grains do not stay in the low temperature regime but undergo frequent

fluctuations going to the high temperature domain where their surface population

evaporates quickly before cooling down. Their average coverage when they are at low

temperatures is thus decreased. The amplitude of this effect depends on the competition

between the fluctuation timescale and the adsorption timescale.

(solid line), for fluctuating grains when

they are at the given temperature T. We see two different effects caused by the

fluctuations. First, the efficiency domain is reduced in both range and maximum value.

This occurs because grains do not stay in the low temperature regime but undergo frequent

fluctuations going to the high temperature domain where their surface population

evaporates quickly before cooling down. Their average coverage when they are at low

temperatures is thus decreased. The amplitude of this effect depends on the competition

between the fluctuation timescale and the adsorption timescale.

|

Fig. 5 Temperature PDF (blue line, left axis) for a 3 nm carbonaceous dust grain, as compared to the formation efficiency (LH mechanism) as a function of temperature (green lines, right axis). The red vertical line marks the mean temperature of the blue PDF. The grain receives a G0 = 20 radiation field and is surrounded by a 100 K gas with nH = 104 cm-3. The energy values correspond to ices. |

The other effect comes from the spread of the temperature PDF. While the average temperature of the PDF falls in the low efficiency domain (and the equilibrium temperature, being higher, is even worse), a significant part of the temperature PDF actually falls in the high efficiency domain, resulting in a quite efficient formation as seen in Fig. 4. The grain spends most of its time in the cold states and makes quick excursions into the high temperatures that shift the average toward high temperatures. The resulting formation rate is thus determined by the fraction of the time spent in the high efficiency domain and not by the equilibrium or average temperature of the grain. As described in Sect. 4.1, the smaller the grain, the more asymmetric the temperature PDF with most of the PDF below its average and a long high temperature tail. The smallest grains are thus the most affected, and we see (Fig. 4) that formation on the very small grains is significantly improved even for the highest radiation field intensities. As the radiation field intensity is decreased, larger grains are affected and become efficient. Grains up to 20 nm are affected. We note here that Cuppen et al. (2006) do not consider grains smaller than 5 nm and thus do not include part of the affected range; they, however, find a similar effect from 5 nm to ~10 nm on their flat surface model.

Parameters of the dust population.

|

Fig. 6 Integrated formation rate parameter Rf (LH mechanism) for a carbonaceous dust population (see Table 3) as a function of the radiation field intensity G0 for different gas densities (the gas temperature is fixed at 100 K). Solid lines: full computation. Dashed lines: equilibrium rate equation results. Binding and barrier energies corresponding to ices. |

To evaluate the importance of this effect on the global formation rate, we integrate our formation rate on a MRN-like power law distribution (Mathis et al. 1977) of carbonaceous grains with an extended size range that goes from 1 nm to 0.3 μm (see Table 3) and obtain a volumic formation rate RH2.

As this distribution strongly favors small grains in term of surface, this integrated rate is strongly affected by the effect on small grains. Figure 6 shows this total formation rate as a function of the radiation field intensity for various gas densities (still using ice energy values). We obtain very efficient formation from the LH mechanism in unshielded PDR edge conditions for high gas densities. In all cases, the formation rate is increased by several orders of magnitude compared to the equilibrium computation. As the smallest grains remain efficient even for strong radiation fields, the total formation rate decreases more slowly when increasing the radiation field.

|

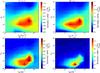

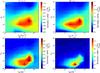

Fig. 8 Conditional mean of the surface coverage (chemisorption only) as a function of grain temperature for three sizes of amorphous carbon grains (solid lines) and equilibrium coverage (dashed line). The grain is surrounded by gas at density nH = 104 cm-3 and temperature T = 350 K under a radiation field with G0 = 120. |

Moreover, we note a difference in the dependency to the gas density. The gas density dependency that comes from the collision rate is already factored out in the definition of the Rf parameter shown on this graph. The equilibrium rate equation result is in the low efficiency regime, where the efficiency is determined by the competition between the adsorption rate (proportional to nH) and the desorption rate, and is thus proportional to the gas density. The result from the method presented here is mainly determined by the fraction of the time spend in the high efficiency regime. This fraction is fully determined by the photon absorption and emission processes and is independent of the gas density. The final result for high gas densities (nH> 103 cm-3) is thus largely independent of the gas density. For low densities, the reduction of the conditional average efficiency curve (noted in Fig. 5) becomes dominant. As this effect results from the competition between the fluctuation rate (due to photons) and the adsorption rate (proportional to nH), the resulting formation parameter Rf becomes proportional again to the gas density for low densities (nH< 103 cm-3). This change of behavior corresponds to the point where the fluctuation timescale becomes significantly smaller than the adsorption timescale.

Figure 7 shows the same result when using binding and barrier energies corresponding to amorphous carbon surfaces. As a consequence of the higher binding energy for amorphous carbon surface, the equilibrium result yields higher formation rates. The increase caused by the fluctuations is thus less dramatic but remains very large for strong radiation fields.

We can already note here that the formation rates obtained in those unshielded PDR edge conditions are comparable to the typical value of 3 × 10-17 cm3 s-1. The LH and the ER mechanisms thus become of comparable importance in PDR edges for high densities, as seen in the results of full cloud simulations shown in Sect. 5.

4.3. H2 formation rate: ER mechanism

The first step in our computation of the formation rate is the conditional mean of the surface population knowing the grain temperature. We show this quantity (as a fraction of the total number of sites) in Fig. 8, as compared to the coverage fraction for a grain at equilibrium at constant temperature (this equilibrium coverage fraction is independent of the grain size). As expected, the equilibrium coverage shows a plateau as long as the desorption rate is negligible compared to the adsorption rate. This plateau is lower than unity as the sticking is less than unity. Then the equilibrium coverage decreases as desorption becomes dominant. The dynamical effect of the temperature fluctuations has a consequence that the actual average populations are not at equilibrium. The grains undergoing a fluctuation to high temperature arrive in their new state with their previous population and then go through a transient desorption phase, which lasts a certain time, thus increasing the average population at the high temperatures compared to the equilibrium. When cooling down back to the low temperature states, re-accretion of their population takes some time, and this effect lowers the average population at low temperatures. Because this lowering effect is important, as seen in Fig. 8, it means that the characteristic time between two temperature spikes is sufficiently short compared to the adsorption timescale. The mechanism at play is thus that grains that go to high temperatures lose their population but then cool down faster than they re-adsorb their surface population and do not spend enough time in the low temperature state before the next fluctuation to have regained their equilibrium population. Of course, as the fluctuations are less dramatic for bigger grains (as a given photon energy makes a smaller temperature change: a Lyman photon at 912 Å brings a 1 nm grain to ~500 K but a 2 nm grain to only ~200 K), the effect disappears for larger grains, as seen in Fig. 8.

The formation rate on one grain is then simply  . The resulting formation efficiency on one

grain is shown in Fig. 9 as a function of grain size.

. The resulting formation efficiency on one

grain is shown in Fig. 9 as a function of grain size.

|

Fig. 9 H2 formation efficiency (ER mechanism) as a function of grain size for various radiation fields (carbonaceous grains in a gas at nH = 104 cm-3 and T = 350 K). |

As explained above, the smaller grains have a lower coverage than equilibrium due to temperature fluctuations and, thus, a decreased formation rate. Only grains below 2 nm are affected, as the same photon absorption causes a smaller temperature fluctuation for bigger grains. For stronger radiation fields, fluctuations occur with a shorter timescale, leaving less time for the surface population to reach equilibrium. The effect is then stronger and extends to higher sizes.

The affected range seems very small, but we have to remember that usual dust size distributions are such that the small grains represent most of the surface (e.g., the MRN distribution). Thus, the contribution from the smallest grain sizes dominates the global formation rate. By integrating over the dust size distribution (same as in Sect. 4.2), we obtain the volumic formation rate in the gas, which we can express as RH2 = Rfn(H) nH defining Rf. In the following, we compare the integrated formation rate that we obtain to the one obtained with the rate equation at constant temperature as used in Le Bourlot et al. (2012) and plot our results as a fraction of this reference formation rate.

The two main parameters are the radiation field intensity and the H atom collision rate (and the sticking coefficient, which modifies the effective collision rate). We use standard interstellar radiation fields with a scaling factor as explained in Sect. 2.1.1.

|

Fig. 10 Integrated formation rate Rf (ER mechanism) over a full dust size distribution (see Table 3) as a fraction of the equilibrium rate equation result. The result is shown for three different gas densities (thus changing the collision rate) as a function of the radiation field intensity. |

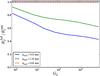

Figure 10 shows the effect of these two parameters. We show the formation rate as a function of the radiation field intensity for different gas densities to probe the effect of the collision rate. Note that the reference rate equation result at constant temperature does not depend on either of these parameters: the density dependency (from the collision rate) is eliminated in the definition of Rf, and the radiation field has no effect when the fluctuations are neglected (the equilibrium temperature is too low to trigger desorption). The effect we show is thus fully the effect of grain temperature fluctuations. As expected, the formation rate decreases when either the radiation intensity is increased or the collision rate is decreased, as the effect results from a competition between the fluctuation rate and the collision rate. The observed reduction remains limited and reaches a ~40% reduction or lower in the range of parameters that we explore. The result that an effect affecting only a tiny fraction of the range of grain sizes can have a significant effect on the integrated formation rate illustrates how the smallest sizes dominate the chemistry in the usual MRN size distribution.

The choice of the lower limit of this size distribution is thus of crucial importance. The lower this minimal size, the larger the usual equilibrium rate equation formation rate will be, as the total dust surface is increased for a constant total dust mass. However, as we lower this limit, we extend the range affected by the fluctuations, and thus obtain a stronger decrease compared to the rate equation result, as shown in Fig. 11. We observe no effect if the size distribution starts above the affected size (e.g., for amin = 3 nm), while a lower limit causes a stronger effect (up to ~60% with amin = 0.5 nm).

|

Fig. 11 Integrated formation rate ratio (ER mechanism) over a full dust size distribution, as a function of the radiation field intensity when changing the inferior limit of the grain size distribution (nH = 104 cm-3). |

Last, as noted in Sect. 2.1.3, the microphysical parameters of the adsorption process are not well known. The adsorption barrier affects the sticking and changes the effective collision rate (see Fig. 10 for the effect of the collision rate). The vibration frequency ν0 has a negligible effect in the range of reasonable values. The most important microphysical parameter is the chemisorption energy Tchem. Figure 12 shows the strong influence of this parameter on the result. A lower chemisorption energy allows for smaller fluctuations to trigger desorption. Bigger grains are thus affected, resulting in a much lower formation rate (e.g., a reduction of more than 90% for Tchem = 3500 K).

|

Fig. 12 Integrated formation rate ratio (ER mechanism) over a full dust size distribution, as a function of the radiation field intensity for different chemisorption binding energies (nH = 104 cm-3). |

5. Integration into the Meudon PDR code

We now investigate the effects of the changes in the formation rate found in the previous section on the overall structure and chemistry of an interstellar cloud with special attention to the observable line intensities.

Our code Fredholm, which computes the H2 formation rate from the LH and ER mechanisms as described in Sects. 2 and 3, has been coupled to the Meudon PDR code described in Le Petit et al. (2006).

The Meudon PDR code models stationary interstellar clouds in a 1D geometry with a full treatment of the radiative transfer (including absorption and emission by both gas and dust), thermal balance, and chemical equilibrium done in a self-consistent way. In its standard settings, the formation of H2 on dust grains is treated using rate equations and including both the LH and ER mechanism, as described in Le Bourlot et al. (2012). We have now enabled the possibility to compute the H2 formation rate using our code Fredholm from the gas conditions and the radiation field sent by the PDR code at each position in the cloud, thus taking temperature fluctuations into account. We compare the results of those coupled runs with the simpler rate equation treatment. The dust population in the PDR models presented here is a single component following a MRN-like power-law distribution from 1 nm to 0.3 μm with an exponent of −3.5, using properties corresponding to a 70−30% mix of graphites and silicates above 3 nm and a progressive transition to PAH properties from 3 nm to 1 nm.

A direct comparison between the rate equation approximation and a full account of stochastic effects is thus possible. In addition to the radiation field illuminating the front side of the cloud, whose strength is indicated for each model, the back side of the cloud is always illuminated by a standard interstellar radiation field (G0 = 1) in the following models.

5.1. Detailed analysis

5.1.1. Effects on PDR edges

We focus first on the effects on PDR edges, as the main effects of a change in formation rate come from the shift of the H / H2 transition that is induced. We have seen in Sect. 4 that the full treatment of fluctuations reduces the efficiency of the ER mechanism while strongly increasing the efficiency of the LH mechanism (compared to a rate equation treatment). The resulting effect in full cloud models depends on the relative importance of the two mechanisms.

|

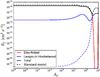

Fig. 13 H2 formation parameter Rf (full treatment: solid lines, standard treatment: dashed lines) for the two processes in a cloud with nH = 103 cm-3 and G0 = 10. |

For low radiation field models, the full treatment increases the LH mechanism at the edge to a level comparable or even higher than the ER mechanism, as shown in Fig. 13. The LH formation rate is increased by more than one order of magnitude and becomes higher than the ER rate, while it was one order of magnitude below in the standard rate equation model. The net result is an increase of the total formation rate by a factor of 4. While we were expecting the ER mechanism to be slightly decreased by the full treatment, we can note that it is slightly increased here. This is due to the gas temperature sensitivity of the ER mechanism. In this low radiation field model, the heating of the gas due to H2 formation is not negligible compared to the usually dominant photoelectric effect. A higher total H2 formation rate increases the heating of the gas resulting in a higher temperature at the edge (see Fig. 14). The ER mechanism is thus made slightly more efficient.

The main effect is a shift of the H / H2 transition from AV = 4 × 10-2 to AV = 8 × 10-3, as shown of Fig. 15. As a result, the column density of excited H2 is increased, as shown in Table 4. As we are in low excitation conditions, the effect is mainly visible on the levels v = 0,J = 2 and v = 0,J = 3.

|

Fig. 17 Atomic H abundance in a cloud with nH = 104 cm-3 and G0 = 102. Comparison of rate equations results (dashed lines) with our full treatment (solid lines). |