| Issue |

A&A

Volume 558, October 2013

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A144 | |

| Number of page(s) | 9 | |

| Section | Extragalactic astronomy | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201322203 | |

| Published online | 23 October 2013 | |

Causal connection in parsec-scale relativistic jets: results from the MOJAVE VLBI survey

1

Max-Planck-Institut für Radioastronomie,

Auf dem Hügel 69,

53121

Bonn,

Germany

e-mail:

clausenbrown@mpifr.de

2

Crimean Astrophysical Observatory, 98409

Nauchny, Crimea,

Ukraine

3

Pulkovo Astronomical Observatory, Pulkovskoe Chaussee 65/1, 196140

St. Petersburg,

Russia

4

Astro Space Center of Lebedev Physical Institute,

Profsoyuznaya

84/32, 117997

Moscow,

Russia

Received:

3

July

2013

Accepted:

8

September

2013

We report that active galactic nucleus (AGN) jets are causally connected on parsec scales, based on 15 GHz Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA) data from a sample of 133 AGN jets. This result is achieved through a new method for measuring the product of the jet Lorentz factor and the intrinsic opening angle Γθj from measured apparent opening angles in flux density limited samples of AGN jets. The Γθj parameter is important for jet physics because it is related to the jet-frame sidewise expansion speed and causal connection between the jet edges and its symmetry axis. Most importantly, the standard model of jet production requires that the jet be causally connected with its symmetry axis, implying that Γθj ≲ 1. When we apply our method to the MOJAVE flux density limited sample of radio loud objects, we find Γθj ≈ 0.2, implying that AGN jets are causally connected. We also find evidence that AGN jets viewed very close to the line of sight effectively have smaller intrinsic opening angles compared with jets viewed more off-axis, which is consistent with Doppler beaming and a fast inner spine/slow outer sheath velocity field. Notably, gamma-ray burst (GRB) jets have a typical Γθj that is two orders of magnitude higher, suggesting that different physical mechanisms are at work in GRB jets compared to AGN jets. A useful application of our result is that a jet’s beaming parameters can be derived. Assuming Γθj is approximately constant in the AGN jet population, an individual jet’s Doppler factor and Lorentz factor (and therefore also its viewing angle) can be determined using two observable quantities: apparent jet opening angle and the apparent speed of jet components.

Key words: galaxies: active / quasars: general / galaxies: jets / BL Lacertae objects: general / gamma-ray burst: general

© ESO, 2013

1. Introduction

A wide variety of processes in relativistic outflows are sensitive to causal connection, or the ability of a disturbance at the edge of an axisymmetric flow to communicate with the symmetry axis1. In the standard magnetic model of relativistic jet production (Beskin 2010), the global jet structure determines the nature of bulk acceleration, implying that the jet must be causally connected for such acceleration to take place (e.g., Tchekhovskoy et al. 2009; Komissarov et al. 2009). Causal connection is determined by the half opening angle of an axisymmetric flow, θj, and the flow Lorentz factor, Γ, through their product Γθj, where Γθj ≲ 1 implies that the jet is causally connected. Other important aspects of relativistic jet physics that depend on Γθj include jet stability (Narayan et al. 2009), magnetic reconnection (Giannios 2013), recollimation shock energy dissipation (Nalewajko & Sikora 2009), and recollimation shock structure (Kohler et al. 2012).

Relativistic outflows have a wide range of values of Γθj. On the one hand, pulsar wind nebulae contain uncollimated (equitorial) outflows that are inferred to reach very high bulk Lorentz factors of Γ ~ 106 prior to the termination shock (Kennel & Coroniti 1984), implying that these outflows have values of Γθj ~ 106 and are not causally connected. On the other hand, narrow relativistic outflows (i.e., jets) associated with X-ray binaries (XRBs), gamma-ray bursts (GRBs), and active galactic nucleus (AGN) typically have much lower values of Γθj; GRB light curve analyses lead to typical inferred values of Γθj of 10−30 (Panaitescu & Kumar 2002), while the narrowness and moderate apparent speeds in XRB jets support the assumption that Γθj ≲ 1 (e.g., Miller-Jones et al. 2006). Thus, while the central engines of the abovementioned objects are similar in that they involve compact magnetized spinning objects, their different values of Γθj suggest that different physical processes are at work.

There have been two past measurements of the characteristic value of Γθj for AGN jets. Using 7 mm Very Long Baseline Array (VLBA) data from 15 different AGN jets, Jorstad et al. (2005) measured Γθj by assuming that the observed pattern speed of moving jet components corresponds to the jet bulk flow speed, and that the component variability times are equal to the jet frame light crossing times of the resolved components. From these assumptions they determined the component’s Lorentz factor and jet half-opening angle, and found an anti-correlation between the derived values of θj and Γ, with Γθj = 0.17. With a larger sample of 56 AGN jets from 15 GHz VLBA data, Pushkarev et al. (2009) performed the same analysis, except they used jet parameters from Hovatta et al. (2009), who derived these values from variability time, maximum flux density of flares, and equipartition derived brightness temperature arguments. The Pushkarev et al. (2009) analysis found a similar anti-correlation with Γθj = 0.13.

Motivated by the above theoretical concerns, we construct a very different method of inferring Γθj by using apparent opening angles obtained from a flux density limited sample of AGN jets. We construct a theoretical probability density function for apparent opening angles in a flux density limited sample, which we derive in Sect. 2, and which has Γθj as a free parameter to be fixed by finding the best fit to an empirical distribution of apparent opening angles. Our data consist of the stacked images from 135 AGN jets that make up the MOJAVE-I sample, a 15 GHz flux density limited survey conducted by the VLBA of radio sources in the northern sky with flux densities above 1.5 Jy, and above 2 Jy for sources with − 20 < dec < 0 (Lister et al. 2009a). The stacked images and opening angles are also discussed and analyzed in Pushkarev et al. (2012). After analyzing the data in Sect. 3, we discuss in Sect. 4 the physical significance of the parameter Γθj for AGN in the context of jet instabilities, GRB jet acceleration vs. AGN jet acceleration, and jet parameter estimation. We conclude in Sect. 5.

2. Statistical model of θapp

Here we model a given jet’s value of θapp as a random variable that is drawn from the probability density function (PDF) P(θapp). That is, P(θapp)dθapp represents the probability that a given jet in a flux density limited sample will have an observed apparent half opening angle between θapp and θapp + dθapp. First, however, we motivate our model by estimating Γθj for blazars, and discuss the effect that velocity shear may have on jet appearance.

Blazars are oriented such that the angle between the jet symmetry axis and the line sight,

θob, is x/Γ, where

x ≈ 0.5 on average in flux density limited samples (Vermeulen & Cohen 1994) such as MOJAVE. This value for

x implies an upper limit on Γθj of

This

is based on the simple argument that most MOJAVE jets are not observed “down the pipe”,

(= θob < θj),

since a down-the-pipe AGN jet would not display jet-like morphology. In fact, most MOJAVE

sources do display a jet-like morphology, which implies that typically

θob > θj

(Clausen-Brown et al. 2011), and therefore that

0.5/Γ > θj

according to the typical value of θob for flux density limited

samples. Also, an estimate of Γθj can be made,

This

is based on the simple argument that most MOJAVE jets are not observed “down the pipe”,

(= θob < θj),

since a down-the-pipe AGN jet would not display jet-like morphology. In fact, most MOJAVE

sources do display a jet-like morphology, which implies that typically

θob > θj

(Clausen-Brown et al. 2011), and therefore that

0.5/Γ > θj

according to the typical value of θob for flux density limited

samples. Also, an estimate of Γθj can be made,  (1)where

⟨ θapp ⟩ ≈ 0.2 rad is the average apparent opening angle in

the MOJAVE-I sample that we use in this work. From geometrical considerations, as long as

all the relevant angles are small,

θj = θobθapp,

thus if ⟨ θapp ⟩ is used for θapp

and 0.5/Γ for θob, then we obtain Eq. (1). An interesting feature of the above estimate

is that it does not significantly depend on the actual value of Γ, which is useful since

jets possess a wide range of Γ values (Lister et al.

2009b). In Sect. 2.1 we will make a more

rigorous analysis of the likely value of Γθj for blazars in

which we will also find that this estimate is mostly independent of blazar values of Γ.

(1)where

⟨ θapp ⟩ ≈ 0.2 rad is the average apparent opening angle in

the MOJAVE-I sample that we use in this work. From geometrical considerations, as long as

all the relevant angles are small,

θj = θobθapp,

thus if ⟨ θapp ⟩ is used for θapp

and 0.5/Γ for θob, then we obtain Eq. (1). An interesting feature of the above estimate

is that it does not significantly depend on the actual value of Γ, which is useful since

jets possess a wide range of Γ values (Lister et al.

2009b). In Sect. 2.1 we will make a more

rigorous analysis of the likely value of Γθj for blazars in

which we will also find that this estimate is mostly independent of blazar values of Γ.

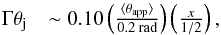

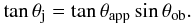

A possibility we explore below is that there is a viewing angle effect related to Doppler beaming and velocity shear that affects the appearance of blazars. Velocity shear is included in a variety of AGN jet models, including parsec-scale models (Swain & Bridle 1998; Attridge et al. 1999; Tavecchio & Ghisellini 2008; Perucho et al. 2012), kiloparsec-scale models (e.g. Owen et al. 1989; Swain & Bridle 1998; Perlman et al. 1999; Laing & Bridle 2004), and more general jet models (Aloy et al. 2000; Chiaberge et al. 2000; McKinney 2006). We assume velocity shear affects very long baseline interferometry (VLBI) measurements of a jet’s apparent opening angle θapp. While all jets may have the same value of Γθj, for jets viewed with very small viewing angles the emission might originate from a fast (beamed) narrow spine that is a fraction of the true jet opening angle θj, while for jets with larger viewing angles the emission from a slow outer sheath with half-opening angle θj may be more detectable. This effect is described in Sect. 2.2.

2.1. Derivation of P(θapp)

To test the viability of the simplest case scenario, we assume that

Γθj is constant for all relativistic jets, and that these

jets are conical and non-accelerating. In general, however, jets are not conical and the

jet flow is either accelerating or decelerating, although in some jet models

Γθj nevertheless remains constant (e.g., Zakamska et al. 2008). Individual observed jet

component acceleration is consistent with only very small changes in Lorentz factor,

(Homan et al. 2009), although an individual jet

does posses a range of component speeds (Lister et al.

2009b, 2013). Thus, our assumption of

conical non-accelerating jets clearly introduces uncertainty to our model.

(Homan et al. 2009), although an individual jet

does posses a range of component speeds (Lister et al.

2009b, 2013). Thus, our assumption of

conical non-accelerating jets clearly introduces uncertainty to our model.

As we show below, Γθj is a free parameter of

P(θapp), and thus will be determined in the

fit to the empirical distribution of θapp. To derive

P(θapp), we first derive the PDF for

viewing angles, P(θob). If the sample of AGN

jets is unbiased with respect to orientation,

P(θob) = sinθob.

However, because it is flux density limited, it will take the form

This

additional factor takes into account that more sources are directed at the observer in a

flux density limited sample because Doppler beamed jets are detectable at greater

distances than unbeamed ones. Cohen (1989) and Vermeulen & Cohen (1994) computed this term and

found that it depends on the bulk Lorentz factor distribution in a flux density limited

sample, the integral source count index, and the beaming index of the jet. The beaming

index is defined from the relation

F = δnF′,

where n is the beaming index, δ is the Doppler factor,

F is the observed flux density density, and

F′ is the intrinsic flux density. The observed integral

source count index is defined in the expression

N(>F) ∝ F− q,

representing the number of sources N observed with a flux density above

F, which is a power law in F with source count index

q. Including the Doppler bias factor in the viewing angle PDF gives

This

additional factor takes into account that more sources are directed at the observer in a

flux density limited sample because Doppler beamed jets are detectable at greater

distances than unbeamed ones. Cohen (1989) and Vermeulen & Cohen (1994) computed this term and

found that it depends on the bulk Lorentz factor distribution in a flux density limited

sample, the integral source count index, and the beaming index of the jet. The beaming

index is defined from the relation

F = δnF′,

where n is the beaming index, δ is the Doppler factor,

F is the observed flux density density, and

F′ is the intrinsic flux density. The observed integral

source count index is defined in the expression

N(>F) ∝ F− q,

representing the number of sources N observed with a flux density above

F, which is a power law in F with source count index

q. Including the Doppler bias factor in the viewing angle PDF gives

(2)where

a = nq − 1, P(Γ) is the PDF for jet

bulk Lorentz factor, and A is the normalization constant. An important

assumption made in calculating the Doppler bias term is that the log-log slope of

N(>F′) vs.

F′ and

N(>F) vs. F

are the same, which Vermeulen & Cohen

(1994) justify based on previous studies of AGN jet luminosity functions (Urry & Shafer 1984; Urry & Padovani 1991). The MOJAVE selection criteria were

designed so that source inclusion in the sample is based on beamed emission only (Lister & Homan 2005). These MOJAVE sources are

typically dominated by core flux density, which usually has a flat spectrum (Kovalev et al. 2005; Pushkarev & Kovalev 2012). Thus, the beaming index n is

most likely ~2 for steady jets (Lind & Blandford

1985), while the integral source count index is approximately 1.5, indicating

that the fiducial value for the a-parameter should be approximately

(Vermeulen & Cohen 1994)

(2)where

a = nq − 1, P(Γ) is the PDF for jet

bulk Lorentz factor, and A is the normalization constant. An important

assumption made in calculating the Doppler bias term is that the log-log slope of

N(>F′) vs.

F′ and

N(>F) vs. F

are the same, which Vermeulen & Cohen

(1994) justify based on previous studies of AGN jet luminosity functions (Urry & Shafer 1984; Urry & Padovani 1991). The MOJAVE selection criteria were

designed so that source inclusion in the sample is based on beamed emission only (Lister & Homan 2005). These MOJAVE sources are

typically dominated by core flux density, which usually has a flat spectrum (Kovalev et al. 2005; Pushkarev & Kovalev 2012). Thus, the beaming index n is

most likely ~2 for steady jets (Lind & Blandford

1985), while the integral source count index is approximately 1.5, indicating

that the fiducial value for the a-parameter should be approximately

(Vermeulen & Cohen 1994)

We

note that if the MOJAVE sources were typically dominated by optically thin flux density,

which typically has a spectral index of α ~ 0.7

(Fν ∝ ν− α),

then a ≈ 3.

We

note that if the MOJAVE sources were typically dominated by optically thin flux density,

which typically has a spectral index of α ~ 0.7

(Fν ∝ ν− α),

then a ≈ 3.

The opening angle distribution may now be derived from

P(θob,Γ) by a change of

variables from θob to θapp and

marginalizing over Γ,  (3)where

θob and

∂θob/∂θapp

are functions of θapp and Γ, and can be determined by assuming

a particular jet geometry that we take to be conical here. These relationships are often

derived by treating conical jets as triangles projected onto the plane of the sky,

implying that

tanθapp = Rj/ℓ′ = Rj/(ℓsinθob),

where θob is the jet viewing angle,

Rj is the jet radius, ℓ

is the jet length, and ℓ′ is the jet length projected onto the

sky. If we assume

θj ≈ Rj/ℓ,

then

(3)where

θob and

∂θob/∂θapp

are functions of θapp and Γ, and can be determined by assuming

a particular jet geometry that we take to be conical here. These relationships are often

derived by treating conical jets as triangles projected onto the plane of the sky,

implying that

tanθapp = Rj/ℓ′ = Rj/(ℓsinθob),

where θob is the jet viewing angle,

Rj is the jet radius, ℓ

is the jet length, and ℓ′ is the jet length projected onto the

sky. If we assume

θj ≈ Rj/ℓ,

then  (4)For

cases where both θapp and θj are

≪1, this reduces to a commonly used relation for jets,

θj = θappsinθob

(Jorstad et al. 2005; Pushkarev et al. 2009). Equation (4) also implies a maximum apparent half-opening angle of

π/2. We assume that jets viewed down-the-pipe where

θob < θj

are rare, since such jets would have

θapp > π/2.

This dearth of down-the-pipe jets, sometimes used to justify the cylindrical approximation

in jet models (Clausen-Brown et al. 2011), also

indicates that typically Γθj < 1. If

the typical viewing angle of a jet is

θob = 0.5/Γ (Vermeulen & Cohen 1994), and most MOJAVE jets exhibit a

jet-like morphology (i.e.,

θapp < π/2)

such that

θob > θj,

then Γθj < 0.5. Here, because many

jets have large apparent opening angles, but are often viewed with small observing angles

and small intrinsic opening angles, we most often use the approximation that

(4)For

cases where both θapp and θj are

≪1, this reduces to a commonly used relation for jets,

θj = θappsinθob

(Jorstad et al. 2005; Pushkarev et al. 2009). Equation (4) also implies a maximum apparent half-opening angle of

π/2. We assume that jets viewed down-the-pipe where

θob < θj

are rare, since such jets would have

θapp > π/2.

This dearth of down-the-pipe jets, sometimes used to justify the cylindrical approximation

in jet models (Clausen-Brown et al. 2011), also

indicates that typically Γθj < 1. If

the typical viewing angle of a jet is

θob = 0.5/Γ (Vermeulen & Cohen 1994), and most MOJAVE jets exhibit a

jet-like morphology (i.e.,

θapp < π/2)

such that

θob > θj,

then Γθj < 0.5. Here, because many

jets have large apparent opening angles, but are often viewed with small observing angles

and small intrinsic opening angles, we most often use the approximation that  (5)This

approximation is mostly appropriate for the blazar dominated MOJAVE sample; below in

Sect. 2.2 we show that this approximation is useful

for categorizing jets by their apparent opening angles.

(5)This

approximation is mostly appropriate for the blazar dominated MOJAVE sample; below in

Sect. 2.2 we show that this approximation is useful

for categorizing jets by their apparent opening angles.

An apparent weakness in our model is that P(Γ) is not well constrained.

This is not the case, however, since P(θapp)

is insensitive to P(Γ), which we demonstrate here. In a flux density

limited VLBI sample, jets with small viewing angles will dominate, so we assume

sinθob ≈ θob, and approximate

(2) as  (6)For

simplicity, we now evaluate Eq. (3) in

light of the geometry implied by Eq. (5),

and obtain

(6)For

simplicity, we now evaluate Eq. (3) in

light of the geometry implied by Eq. (5),

and obtain ![\begin{eqnarray} P(\tapp)&=A\left(1+\frac{\rho^2}{\tan^2{\tapp}}\right)^{-a-1}\frac{\cos{\tapp}}{\sin^3{\tapp}} \notag\\ &\quad \times\left[2^{a\,+\,1}\rho^2\int{\Gamma^{2a}P(\Gamma){\rm d}\Gamma}\right] \notag\\ &= A'\left(1+\frac{\rho^2}{\tan^2{\tapp}}\right)^{-a-1}\frac{\cos{\tapp}}{\sin^3{\tapp}}, \label{approx2} \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/10/aa22203-13/aa22203-13-eq83.png) (7)where

ρ = Γθj, and we have absorbed the term in

brackets into the new normalization, A′. Thus, it is apparent

from Eq. (7) that

P(θapp) does not depend significantly on

the form of P(Γ). Equation (7) is an accurate approximation of

P(θapp) as long as ρ ≪ 1,

which is a valid assumption as shown by our best value of ρ ≈ 0.2

discussed below.

(7)where

ρ = Γθj, and we have absorbed the term in

brackets into the new normalization, A′. Thus, it is apparent

from Eq. (7) that

P(θapp) does not depend significantly on

the form of P(Γ). Equation (7) is an accurate approximation of

P(θapp) as long as ρ ≪ 1,

which is a valid assumption as shown by our best value of ρ ≈ 0.2

discussed below.

2.2. Velocity shear and Doppler beaming

As suggested by the very approximate estimate made above in which radio galaxies appear to have larger θj than blazars, velocity shear and Doppler beaming may affect the distribution of θapp. Unfortunately, modeling the effect of velocity of shear on jet appearance is sensitive to a variety of unknown details regarding the jet structure such as how the density of non-thermal electrons scales with jet radius and the particular functional form of the velocity shear. Thus, in an effort to capture only the most basic effect velocity shear has on jet appearance, we develop a minimalist model.

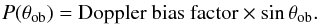

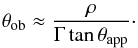

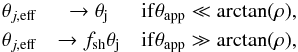

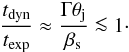

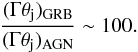

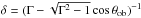

We assume the velocity field of a jet consists of an ultra-relativistic inner spine and a surrounding shear layer that is mildly relativistic (see Fig. 2). The relativistic spine, which dominates the core emission, is what primarily determines whether a jet is included in a flux density limited sample like the blazar dominated MOJAVE sample. We note, however, that this assumption may sometimes be violated since a few MOJAVE sources such as M87 may have significant sheath emission (e.g., Kovalev et al. 2007). The optically thin jet downstream from the core is where apparent opening angles are measured, and where the degree to which the shear layer is observable is important. For jets aligned close to the line of sight, the jets will be more dominated by the fast spine where Γ ≫ 1 and the slower outer layers will remain unobserved, while more misaligned the jets will have a slower outer sheath of Γshear≲ few that is more likely visible. See Fig. 1 for an illustration of this effect.

Now, jets can be divided into two categories based on whether a jet’s viewing angle

θob is less than or greater than 1/Γ,

where Γ is the value of the Lorentz factor in the fast inner spine. This categorization

can be mapped onto θapp by using Eq. (5), resulting in

(8)This

categorization is useful since the critical angle 1/Γ defines when

beaming is important. When

θob > 1/Γ, then

Earth is outside of the inner jet’s beaming cone, thus the jet’s slower outer layers are

more likely to be visible, since the fast inner spine’s beaming is less dominant. The

hypothesis that highly beamed jets

(θob < 1/Γ) and

not highly beamed jets

(θob > 1/Γ) can

be separated by their observed θapp has some observational

support, which we discuss in Sect. 4.3.

(8)This

categorization is useful since the critical angle 1/Γ defines when

beaming is important. When

θob > 1/Γ, then

Earth is outside of the inner jet’s beaming cone, thus the jet’s slower outer layers are

more likely to be visible, since the fast inner spine’s beaming is less dominant. The

hypothesis that highly beamed jets

(θob < 1/Γ) and

not highly beamed jets

(θob > 1/Γ) can

be separated by their observed θapp has some observational

support, which we discuss in Sect. 4.3.

|

Fig. 1 Meridional slice of a jet illustrating two cases: (i) jets aligned close to the line of sight where emission is dominated by the fast inner spine; and (ii) more misaligned jets where the emission from outer slower layers contributes as well. |

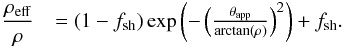

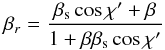

The simplest way to model the effect that velocity shear and beaming have on jet

appearence is to postulate that jets that have

θob < 1/Γ have an

effective jet opening angle

θj,eff = ρeff/Γ,

where θj,eff is some fraction of the true jet

opening angle such that

θj,eff = fshθj,

or equivalenty,

ρeff = fshρ.

Thus,  where

fsh is a free parameter. We note that the inner spine

Doppler factor of a jet with

θapp ~ θj (i.e., a radio galaxy)

is δ ~ 1/Γ, a jet with

θapp = ρ has δ ~ Γ, and a

jet with θapp ~ 1 has δ ~ 2Γ. In other words,

the most drastic change in δ occurs in a narrow range of

θapp, for

0 < θapp < ρ,

while δ only changes by a factor of 2 in the large range

ρ < θapp ≲ 1. To

illustrate this point, we plot the Doppler factor as a function of

θapp in Fig. 2. Thus,

the effect of velocity shear on jet appearance should be strongest for

θapp = 0 to ρ. To reproduce this behavior,

we choose the following arbitrary function,

where

fsh is a free parameter. We note that the inner spine

Doppler factor of a jet with

θapp ~ θj (i.e., a radio galaxy)

is δ ~ 1/Γ, a jet with

θapp = ρ has δ ~ Γ, and a

jet with θapp ~ 1 has δ ~ 2Γ. In other words,

the most drastic change in δ occurs in a narrow range of

θapp, for

0 < θapp < ρ,

while δ only changes by a factor of 2 in the large range

ρ < θapp ≲ 1. To

illustrate this point, we plot the Doppler factor as a function of

θapp in Fig. 2. Thus,

the effect of velocity shear on jet appearance should be strongest for

θapp = 0 to ρ. To reproduce this behavior,

we choose the following arbitrary function,  (9)We

plot this function in Fig. 2. This equation can

easily be inserted into our theoretical PDF described in Eq. (3), which can then be evaluated numerically,

where ρ and fsh are free parameters to be

found in the fit. If this model is correct, then the best fit value of

fsh should be less than unity. In the case of no shear, then

fsh = 1 and

ρeff = ρ.

(9)We

plot this function in Fig. 2. This equation can

easily be inserted into our theoretical PDF described in Eq. (3), which can then be evaluated numerically,

where ρ and fsh are free parameters to be

found in the fit. If this model is correct, then the best fit value of

fsh should be less than unity. In the case of no shear, then

fsh = 1 and

ρeff = ρ.

|

Fig. 2 Doppler factor and ρeff as a function of a jet’s apparent half-opening angle θapp. The semi-logarithmic Doppler factor plot in the upper panel is for a jet with Γ = 10 and ρ = 0.21, and uses Eq. (4) to convert θapp to θob. The lower panel plot shows ρeff as a function of θapp from Eq. (9) using ρ = 0.21 and fsh = 0.33, the best fit values found in Sect. 3.2. |

3. Data analysis and results

3.1. Apparent opening angles

The apparent opening angles used here are derived from stacked images of 133 sources from

the MOJAVE-I catalogue of 135 sources2. For two

sources opening angles could not be derived. To produce a stacked image of a given source,

all single-epoch maps were aligned by their VLBI core components, and then averaged

together. The resulting opening angle data originates from the analysis in Pushkarev et al. (2012), who derived

θapp by taking the median value of

(10)where

“d is the full width half maximum (FWHM) of the Gaussian transverse

profile, r is the distance to the core along the jet axis,

bφ is the beam size along the position

angle φ of the jet-cut, and the quantity

(10)where

“d is the full width half maximum (FWHM) of the Gaussian transverse

profile, r is the distance to the core along the jet axis,

bφ is the beam size along the position

angle φ of the jet-cut, and the quantity

is the deconvolved FWHM transverse size of the jet” (for more details, see Pushkarev et al. 2012). Note that in this work we use

half opening angles, while Pushkarev et al. (2012)

used full opening angles, which merely differ by a factor of 2.

is the deconvolved FWHM transverse size of the jet” (for more details, see Pushkarev et al. 2012). Note that in this work we use

half opening angles, while Pushkarev et al. (2012)

used full opening angles, which merely differ by a factor of 2.

3.2. Best fits and goodness of fit

We now compare the opening angle data to Eq. (3), where P(Γ) ∝ Γ-1.5 with Γmin = 2 and Γmax = 50. We note, however, that Eq. (3) is insensitive to the form of P(Γ) as we demonstrated in Eq. (7).

We find the best fits using maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) by minimizing the

negative log-likelihood function  (11)where

our data set is

X = (θapp,1,...,θapp,N),

P(Xi,m)

represents P(θapp) evaluated at

θapp = Xi, and

m is a vector representing the free parameters of the distribution

P(θapp). As discussed below, we fit our

data set of N = 133 for six different cases in which the distribution’s

free parameters ranges from three,

m = (ρ,fsh,a),

to only one, m = ρ. When fsh

is not a free parameter it is fixed at 1, and when a is not free it is

fixed at either 2 or 3, as specified below. In all of these cases, we obtain the best fit

parameters

(11)where

our data set is

X = (θapp,1,...,θapp,N),

P(Xi,m)

represents P(θapp) evaluated at

θapp = Xi, and

m is a vector representing the free parameters of the distribution

P(θapp). As discussed below, we fit our

data set of N = 133 for six different cases in which the distribution’s

free parameters ranges from three,

m = (ρ,fsh,a),

to only one, m = ρ. When fsh

is not a free parameter it is fixed at 1, and when a is not free it is

fixed at either 2 or 3, as specified below. In all of these cases, we obtain the best fit

parameters  by numerically minimizing h (Eq. (11)).

by numerically minimizing h (Eq. (11)).

To correctly model the fitting error and assess the goodness of fit, we used the

Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) statistic LN in

conjunction with the nonparametric bootstrap as described in Feigelson & Babu (2012). Recall that the KS statistic gives a

measure of the distance between the data and the model by finding the maximum distance

between the empirical cumulative distribution function

FN(θapp) and

theoretical cumulative distribution function  ,

i.e.,

,

i.e.,  (12)Here,

for each bootstrap realization, we generate the simulated data X∗

via sampling with replacement, find the best fit parameters

(12)Here,

for each bootstrap realization, we generate the simulated data X∗

via sampling with replacement, find the best fit parameters

for the simulated data X∗ using the MLE procedure described above,

and then calculate the KS statistic

for the simulated data X∗ using the MLE procedure described above,

and then calculate the KS statistic  from

X∗ and

from

X∗ and  by using Eq. (12) with an additional bias

correction factor taken into account (see Eq. (3.48) of Feigelson & Babu 2012).

by using Eq. (12) with an additional bias

correction factor taken into account (see Eq. (3.48) of Feigelson & Babu 2012).

After iterating the bootstrap B = 2000 times, we obtain confidence

intervals around  by analyzing the distribution of simulated best-fit parameters

by analyzing the distribution of simulated best-fit parameters

and directly compute the 68% and 95% confidence intervals and error contours. The

resulting distribution of the statistic

and directly compute the 68% and 95% confidence intervals and error contours. The

resulting distribution of the statistic  can be used

for model selection by finding the probability p that a value of

LN or greater is observed, assuming that

X is drawn from

can be used

for model selection by finding the probability p that a value of

LN or greater is observed, assuming that

X is drawn from  .

This is done by defining k as the number of

.

This is done by defining k as the number of

values that

fulfill the criterion

values that

fulfill the criterion  , and then

computing the p-value as

p = k/B. Thus, for

a significance level of α = 0.05, models with p-values

of 0.05 and above are favored by the data (i.e. they cannot be rejected). As discussed

below, we consider six different cases, thus we perform different bootstrap simulations

for each case.

, and then

computing the p-value as

p = k/B. Thus, for

a significance level of α = 0.05, models with p-values

of 0.05 and above are favored by the data (i.e. they cannot be rejected). As discussed

below, we consider six different cases, thus we perform different bootstrap simulations

for each case.

We now apply the above analysis to the data for two different types of models:

No shear model: three cases are considered for our model with no shear, i.e., fsh = 1, depending how the parameter a is treated: (i) a is set to 2; (ii) a = 3; and (iii) a is a free parameter found in the best fit. As it turns out, in case (iii) the best-fit value of a, 6.3, is much higher than the expected fiducial value of 2, and the distribution of best-fit values of a in bootstrap simulations routinely ranges much higher (several tens). In addition, the best values of ρ in the bootstrap simulations is tightly correlated with a, and also ranges widely, suggesting that a and ρ are highly degenerate.

Velocity shear model: here we perform the same analysis and consider the same three cases as above, but with fsh as a free parameter. Thus, ρ and fsh are free parameters and we consider three different cases regarding a: (i) a = 2; (ii) a = 3; and (iii) a as a free parameter to be found in the best fit.

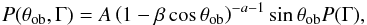

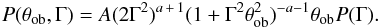

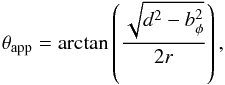

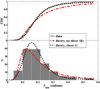

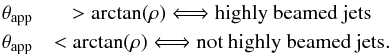

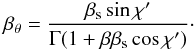

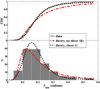

Table 1 gives a summary of our best-fit results, and

Fig. 3 shows a comparison between the data and two

different best-fit models, each with the same number of free parameters (two). The models

that include relativistic velocity shear are clearly favored by the data, as they all have

p-values above 0.05. When shear is included and all the parameters are

varied (the shear (iii) model), the best fit produces a reasonable value of

(and ρ = 0.21 ± 0.03 and

fsh = 0.33 ± 0.1), which is close to the expected value

of a = 2 from Doppler beaming models and integral source counts of

radio-selected AGN. Encouragingly, the best-fit values for all of the models is

ρ = 0.1−0.2, which is consistent with the values of 0.17 and 0.13

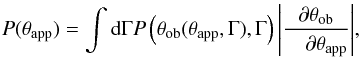

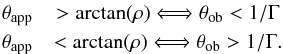

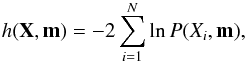

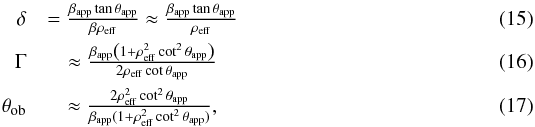

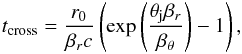

reported in Jorstad et al. (2005) and Pushkarev et al. (2009), respectively. Figure 4 shows the two dimensional error contours for the

shear (iii) model. Since our shear models produce better fits with high

p-values and a reasonable value of a, we conclude that

it is likely that relativistic shear and Doppler beaming play a role in jet appearance. As

our final result for a measurement of Γθj, we report

0.21 ± 0.03 from the shear (iii) model. However, for a more direct comparison between our

value of ρ and that of other researchers, we calculate the expected value

of ρeff(θapp)

(and ρ = 0.21 ± 0.03 and

fsh = 0.33 ± 0.1), which is close to the expected value

of a = 2 from Doppler beaming models and integral source counts of

radio-selected AGN. Encouragingly, the best-fit values for all of the models is

ρ = 0.1−0.2, which is consistent with the values of 0.17 and 0.13

reported in Jorstad et al. (2005) and Pushkarev et al. (2009), respectively. Figure 4 shows the two dimensional error contours for the

shear (iii) model. Since our shear models produce better fits with high

p-values and a reasonable value of a, we conclude that

it is likely that relativistic shear and Doppler beaming play a role in jet appearance. As

our final result for a measurement of Γθj, we report

0.21 ± 0.03 from the shear (iii) model. However, for a more direct comparison between our

value of ρ and that of other researchers, we calculate the expected value

of ρeff(θapp)  (13)where

the parameters of P(θapp) are those for the

shear (iii) model listed in Table 1, and the confidence

interval comes from the bootstrap simulations used to derive the confidence intervals for

the shear (iii) model. Indeed, this value of

⟨ ρeff ⟩ ≈ 0.13 ± 0.02 is consistent with both Pushkarev et al. (2009) and Jorstad et al. (2005).

(13)where

the parameters of P(θapp) are those for the

shear (iii) model listed in Table 1, and the confidence

interval comes from the bootstrap simulations used to derive the confidence intervals for

the shear (iii) model. Indeed, this value of

⟨ ρeff ⟩ ≈ 0.13 ± 0.02 is consistent with both Pushkarev et al. (2009) and Jorstad et al. (2005).

|

Fig. 3 Example best fits for two cases are shown in the form of cumulative distribution functions (CDF, upper panel) and probability density functions (PDF, lower panel). The two cases shown, “no shear (iii)” (dash-dotted line) and “shear (i)” (dotted line), both have the same number of free parameters (two), but the shear (i) model clearly fits the data better. The data is represented as a solid line (upper panel) or histogram (lower panel). |

|

Fig. 4 68% and 95% confidence contours from Monte Carlo error analysis for the best-fit parameters ρ, a, and fsh, from the case of shear (iii). The central star shows the MLE of the parameters. We emphasize the a vs. ρ plot since there is a fiducial value for a (=2, vertical dotted line), and ρ has constraints set on it by Jorstad et al. (2005) and Pushkarev et al. (2009). |

Parameter values (both best fit and assigned) for six different cases along with 68% confidence intervals where relevant.

A more rigorous comparison between our best-fit value for ρ and those of other researchers requires a proper error analysis for all of the different measured/inferred values for ρ, both in this paper and in other works. However, in the case of Jorstad et al. (2005) and Pushkarev et al. (2009), the error in their estimated values for θj and Γ for each jet is unknown, as these estimates rely upon highly uncertain model assumptions regarding, for example, equipartition brightness temperature arguments and the equation of component variability with light-crossing times. In addition to this error, it is also possible that AGN jets possess a range of values of ρ, as opposed to our assumption that all jets have the same ρ. These same issues apply to our simple model. More specifically, our confidence limits (see Fig. 4) are probably underestimated since there is considerable uncertainty in our model of velocity shear, our assumption of jet conical geometry, and our assumption that all MOJAVE jets posses the same value of ρ.

4. Discussion

4.1. Relativistic jet physics and Γθj

A variety of physical processes in jets are sensitive to Γθj.

Causal connection implies that θjℳ ≤ 1, where

ℳ = βΓ/(Γsβs)

is the relativistic Mach number, which is the ratio of the jet proper speed to proper

signal speed. (In the Appendix we explain the relationship between

θjℳ, Γθj, and causality). For

jets with a dynamically important magnetic field, the signal speed is the fast

magnetosonic speed, while for jets with no significant magnetic field the signal speed is

the sound speed, which is  for a relativistically hot jet. The fast magnetosonic proper speed is

Γmsβms = σ1/2,

where σ is the magnetization parameter, which is the ratio of Poynting

flux to kinetic flux (Kennel & Coroniti

1984). Beyond the acceleration zone the jet is likely to be in equipartition such

that σ is of the order of unity (e.g., Komissarov et al. 2007). Thus, fiducial jet signal speeds imply that the causal

connection condition for jets is

for a relativistically hot jet. The fast magnetosonic proper speed is

Γmsβms = σ1/2,

where σ is the magnetization parameter, which is the ratio of Poynting

flux to kinetic flux (Kennel & Coroniti

1984). Beyond the acceleration zone the jet is likely to be in equipartition such

that σ is of the order of unity (e.g., Komissarov et al. 2007). Thus, fiducial jet signal speeds imply that the causal

connection condition for jets is  indicating

that AGN jets with the value we have determined here,

Γθj ~ 0.2, are probably causally connected. This verifies the

standard picture of jet production (see Sect. 4.2

and Komissarov et al. 2009), and also implies that

AGN jets are susceptible to various instabilities and reconnection, and are also sensitive

to conditions at the boundary between the jet and the interstellar medium.

indicating

that AGN jets with the value we have determined here,

Γθj ~ 0.2, are probably causally connected. This verifies the

standard picture of jet production (see Sect. 4.2

and Komissarov et al. 2009), and also implies that

AGN jets are susceptible to various instabilities and reconnection, and are also sensitive

to conditions at the boundary between the jet and the interstellar medium.

The particular value of Γθj is also important for instability

development (Narayan et al. 2009), because it gives

a measure of the extent to which jet sidewise expansion inhibits instability growth. Most

global instabilities grow on some comoving signal crossing timescale,

tdyn = Γθjz/(βsc),

where βs is the signal speed and z is the jet

height above the launching region. For Kelvin-Helmholtz instabilities

βs is the sound speed (Perucho et al. 2004; Hardee et al. 2005),

while for current driven kink instabilities βs is the Alfvén

speed (Giannios & Spruit 2006). This

so-called dynamical timescale for the growth of instabilities must be compared to the jet

expansion time

texp = z/(βc),

where if

texp > tdyn

then jet expansion will quench instability growth (Begelman

1998; Giannios & Spruit 2006;

Moll et al. 2008; Spruit 2010). This criterion for instability growth then becomes

(14)Since

Γθj ~ 0.2, then AGN jet instabilities can grow despite jet

expansion, unless βs ≲ 0.2, which would be below the

relativistic adiabatic sound speed of ~0.6.

(14)Since

Γθj ~ 0.2, then AGN jet instabilities can grow despite jet

expansion, unless βs ≲ 0.2, which would be below the

relativistic adiabatic sound speed of ~0.6.

4.2. Jet acceleration for GRBs vs. AGNs

Long duration GRBs have typical values of Γθj of the order of

10−30 (Panaitescu & Kumar 2002), which is

two orders of magnitude higher than the value we find for AGN jets:

Thus,

it is possible that different physics are at work in GRB jets. Tchekhovskoy et al. (2010) found that a jet acceleration mechanism

(first discovered by Aloy & Rezzolla 2006

and Mizuno et al. 2008) can operate in GRBs in

which a brief period of bulk acceleration occurs upon jet break out into the circumstellar

medium and allows the jet to take on values of Γθj ≫ 1. Komissarov et al. (2010) call this process

rarefaction acceleration, and contrast it to the standard jet

acceleration model of collimation acceleration described in Li et al. (1992) and many other works. Collimation

acceleration entails jet acceleration over an extended distance along the jet (Vlahakis & Konigl 2004) and implies that

Γθj ≤ 1 (Komissarov et al.

2009; Tchekhovskoy et al. 2009). In

contrast, rarefaction acceleration occurs in GRBs because they are initially confined by

the shocked boundary layer in the star until the jet breaks out into the circumstellar

medium, becomes unconfined, and launches a rarefaction wave toward the center of the jet.

If the jet is still magnetically dominated at that point, then this process further

accelerates the jet, and can produce Γθj ≫ 1. Thus, the

dichotomy between GRB jets and AGN jets is nicely explained by the different physical

processes at work in GRB jets (rarefaction acceleration due to jet break out) and AGN jets

(collimation acceleration). Furthermore, as Komissarov et

al. (2010) explain, rarefaction acceleration increases the

Γθj parameter primarily by increasing Γ alone (The increase

in θj is less than 1/Γ). Thus, to the

degree that the typical AGN jet value of Γθj is equal to the

pre-breakout GRB jet value of Γθj, one can infer that

(Γθj)GRB is so much larger than

(Γθj)AGN because of the increase of the GRB jet’s

Γ during the rarefaction acceleration process. Interestingly, this suggests that GRBs have

Γ ≳ 100, which is consistent with the lower limit obtained by requiring that GRB prompt

emission regions be optically thin to gamma-rays with respect to photon-photon pair

production (e.g., Piran 2004).

Thus,

it is possible that different physics are at work in GRB jets. Tchekhovskoy et al. (2010) found that a jet acceleration mechanism

(first discovered by Aloy & Rezzolla 2006

and Mizuno et al. 2008) can operate in GRBs in

which a brief period of bulk acceleration occurs upon jet break out into the circumstellar

medium and allows the jet to take on values of Γθj ≫ 1. Komissarov et al. (2010) call this process

rarefaction acceleration, and contrast it to the standard jet

acceleration model of collimation acceleration described in Li et al. (1992) and many other works. Collimation

acceleration entails jet acceleration over an extended distance along the jet (Vlahakis & Konigl 2004) and implies that

Γθj ≤ 1 (Komissarov et al.

2009; Tchekhovskoy et al. 2009). In

contrast, rarefaction acceleration occurs in GRBs because they are initially confined by

the shocked boundary layer in the star until the jet breaks out into the circumstellar

medium, becomes unconfined, and launches a rarefaction wave toward the center of the jet.

If the jet is still magnetically dominated at that point, then this process further

accelerates the jet, and can produce Γθj ≫ 1. Thus, the

dichotomy between GRB jets and AGN jets is nicely explained by the different physical

processes at work in GRB jets (rarefaction acceleration due to jet break out) and AGN jets

(collimation acceleration). Furthermore, as Komissarov et

al. (2010) explain, rarefaction acceleration increases the

Γθj parameter primarily by increasing Γ alone (The increase

in θj is less than 1/Γ). Thus, to the

degree that the typical AGN jet value of Γθj is equal to the

pre-breakout GRB jet value of Γθj, one can infer that

(Γθj)GRB is so much larger than

(Γθj)AGN because of the increase of the GRB jet’s

Γ during the rarefaction acceleration process. Interestingly, this suggests that GRBs have

Γ ≳ 100, which is consistent with the lower limit obtained by requiring that GRB prompt

emission regions be optically thin to gamma-rays with respect to photon-photon pair

production (e.g., Piran 2004).

4.3. Doppler beaming and θapp

If Γθj is approximately constant in the AGN jet population,

then θapp is an important observable quantity related to

Doppler beaming for two reasons. First, it can serve as a dividing line between highly

beamed (θob < 1/Γ)

jets and not highly beamed jets

(θob > 1/Γ), a

property we exploit in our model of velocity shear in Sect. 2.2. This division conveniently maps onto θapp as

follows:  This

implies that jets with

θapp ~ Γθj ~ 0.2 are observed at

the critical angle, thus maximizing the apparent speed of their superluminal components.

This division provides a concise way of explaining the Pushkarev et al. (2009) argument that large-opening angle jets are more highly

Doppler beamed: large opening angle jets with θapp ≳ 0.2 are

all observed within the critical angle and therefore more highly beamed than smaller

θapp jets. Pushkarev et al.

(2009) also find that AGN jets with larger θapp have

a higher Fermi-LAT detection rate, and all jets with

θapp > 0.35 are detected by

Fermi-LAT, implying that Fermi-LAT detected jets tend

to have higher Doppler factors. Notably, this finding is also supported by Kovalev et al. (2009), Savolainen et al. (2010), and Lister et al.

(2009c), who found evidence that radio jets of Fermi-detected AGN are more likely

to have high Doppler factors than are non Fermi-LAT detected sources.

This

implies that jets with

θapp ~ Γθj ~ 0.2 are observed at

the critical angle, thus maximizing the apparent speed of their superluminal components.

This division provides a concise way of explaining the Pushkarev et al. (2009) argument that large-opening angle jets are more highly

Doppler beamed: large opening angle jets with θapp ≳ 0.2 are

all observed within the critical angle and therefore more highly beamed than smaller

θapp jets. Pushkarev et al.

(2009) also find that AGN jets with larger θapp have

a higher Fermi-LAT detection rate, and all jets with

θapp > 0.35 are detected by

Fermi-LAT, implying that Fermi-LAT detected jets tend

to have higher Doppler factors. Notably, this finding is also supported by Kovalev et al. (2009), Savolainen et al. (2010), and Lister et al.

(2009c), who found evidence that radio jets of Fermi-detected AGN are more likely

to have high Doppler factors than are non Fermi-LAT detected sources.

Second, by measuring both a jet’s θapp and its typical

apparent speed

βapp = βsinθob(1 − βcosθob)-1,

we can derive that jet’s Doppler factor, Lorentz factor, and therefore also the viewing

angle,  where

where

is the Doppler factor and β is the jet velocity in units of the speed of

light. Except for Eq. (15), which shows

both the exact and approximate form of δ, the above equations are

approximations that assume Γ ≫ 1 and θob ≪ 1.

is the Doppler factor and β is the jet velocity in units of the speed of

light. Except for Eq. (15), which shows

both the exact and approximate form of δ, the above equations are

approximations that assume Γ ≫ 1 and θob ≪ 1.

Thus, Eqs. ((15)–(17)) demonstrate that, if the spread of ρ (=Γθj) is small enough in the jet population, the measurable quantities βapp and θapp can be useful for calculating intrinsic jet quantities such as the intrinsic brightness temperature and Lorentz factor of jet components. In a future work we intend to explore this new method of deriving a jet’s beaming parameters.

5. Conclusion

We have derived a statistical model of relativistic jet apparent opening angles and fit it to the observed distribution of jet apparent opening angles in the MOJAVE sample. The product of Lorentz factor and intrinsic jet opening angle Γθj is a free parameter in our model and was determined by the best fit to be Γθj ≈ 0.2. We summarize our conclusions as follows.

-

1.

Γθj ~ 0.2 implies that jets are causally connected (see the Appendix), which is predicted by magnetic jet production models. Causal connection also implies that AGN jets are subject to Kelvin-Helmholtz and current-driven (kink) modes, unless the relevant signal speed is ≲Γθjc ~ 0.2c.

-

2.

The value of Γθj for GRB jets is 100 times larger than Γθj for AGN jets. This difference is neatly explained by an acceleration process probably unique to GRBs, wherein a rarefaction wave is launched into the jet after the jet breaks out of its stellar envelope and into the lower pressure circumstellar medium. This is consistent with the high Lorentz factors inferred for GRB jets of Γ ≳ 100.

-

3.

In order to adequately fit the θapp data, we included the effects of relativistic velocity shear and Doppler beaming. Velocity shear affects jets by making blazars appear narrower as their ultra-relativistic inner spine is all that is visible, while jets viewed outside the critical angle 1/Γ appear to have larger jet opening angles. Distinguishing jets based on their critical angle conveniently creates a division between highly beamed jets and not so highly beamed jets that corresponds to whether an individual jet’s apparent opening angles is θapp ≲ Γθj (not highly beamed) or θapp ≳ Γθj (highly beamed).

-

4.

Assuming Γθj is mostly constant across the AGN jet population, then a jet’s Doppler factor, Lorentz factor, and viewing angle can be calculated if the observable values of apparent jet opening angle θapp and the apparent speed of the jet components βapp are known. This is shown in Eqs. ((15)–(17)).

Acknowledgments

ECB thanks M. Böck, M. Zamaninasab, M. Lister, M. Lyutikov, and D. Giannios for valuable discussions. A.B.P. was supported by the “Non-stationary processes in the Universe” Program of the Presidium of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Y.Y.K. was supported by the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (project 12-02-33101), the Dynasty Foundation, and the Research Program OFN-17 of the Division of Physics, Russian Academy of Sciences. This research has made use of data from the MOJAVE database that is maintained by the MOJAVE team (Lister et al. 2009a).

References

- Aloy, M. A., & Rezzolla, L. 2006, ApJ, 640, L115 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Aloy, M. A., Gómez, J. L., Ibáñez, J. M., et al. 2000, ApJ, 528, L85 [Google Scholar]

- Attridge, J. M., Roberts, D. H., & Wardle, J. F. C. 1999, ApJ, 518, L87 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Begelman, M. C. 1998, ApJ, 493, 291 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Beskin, V. S. 2010, Phys. Uspekhi, 53, 1197 [Google Scholar]

- Chiaberge, M., Celotti, A., Capetti, A., & Ghisellini, G. 2000, A&A, 358, 104 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Clausen-Brown, E., Lyutikov, M., & Kharb, P. 2011, MNRAS, 415, 2081 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, M. H. 1989, in BL Lac Objects, eds. L. Maraschi, T. Maccacaro, & M.-H. Ulrich (Berlin: Springer), 13 [Google Scholar]

- Feigelson, E. D., & Babu, G. J. 2012, Modern Statistical Methods for Astronomy (Cambridge University Press) [Google Scholar]

- Giannios, D. 2013, MNRAS, 431, 355 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Giannios, D., & Spruit, H. C. 2006, A&A, 898, 887 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Hardee, P. E., Walker, R. C., & Gómez, J. L. 2005, ApJ, 620, 646 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Homan, D. C., Kadler, M., Kellermann, K. I., et al. 2009, ApJ, 706, 1253 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hovatta, T., Valtaoja, E., Tornikoski, M., & Lähteenmäki, A. 2009, A&A, 537, 527 [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Jorstad, S. G., Marscher, A. P., Lister, M. L., et al. 2005, AJ, 130, 1418 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kennel, C. F., & Coroniti, F. V. 1984, ApJ, 283, 694 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita, S., Sendouda, Y., & Takahashi, K. 2004, Phys. Rev. D, 70, 123006 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler, S., Begelman, M. C., & Beckwith, K. 2012, MNRAS, 422, 2282 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Komissarov, S. S., Barkov, M. V., Vlahakis, N., & Königl, A. 2007, MNRAS, 380, 51 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Komissarov, S. S., Vlahakis, N., Königl, A., & Barkov, M. V. 2009, MNRAS, 394, 1182 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Komissarov, S. S., Vlahakis, N., & Königl, A. 2010, MNRAS, 407, 17 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Konigl, A. 1980, Phys. Fluids, 23, 1083 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalev, Y. Y., Kellermann, K. I., Lister, M. L., et al. 2005, AJ, 130, 2473 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalev, Y. Y., Lister, M. L., Homan, D. C., & Kellermann, K. I. 2007, ApJ, 668, L27 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalev, Y. Y., Aller, H. D., Aller, M. F., et al. 2009, ApJ, 696, L17 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Laing, R. A., & Bridle, A. H. 2004, MNRAS, 348, 1459 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z., Chiueh, T., & Begelman, M. C. 1992, ApJ, 394, 459 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lind, K., & Blandford, R. 1985, ApJ, 295, 358 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lister, M. L., & Homan, D. C. 2005, AJ, 130, 1389 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lister, M. L., Aller, H. D., Aller, M. F., et al. 2009a, AJ, 137, 3718 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lister, M. L., Cohen, M. H., Homan, D. C., et al. 2009b, AJ, 138, 1874 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lister, M. L., Homan, D. C., Kadler, M., et al. 2009c, ApJ, 696, L22 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lister, M. L., Aller, M. F., Aller, H. D., et al. 2013, AJ, 146, 120 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lyutikov, M., Pariev, V. I., & Blandford, R. D. 2003, ApJ, 597, 998 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- McKinney, J. C. 2006, MNRAS, 368, 1561 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Jones, J. C. A., Fender, R. P., & Nakar, E. 2006, MNRAS, 367, 1432 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno, Y., Hardee, P., Hartmann, D. H., et al. 2008, ApJ, 672, 72 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Moll, R., Spruit, H. C., & Obergaulinger, M. 2008, A&A, 630, 621 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Nakar, E., Piran, T., & Waxman, E. 2003, JCAP, 10 [Google Scholar]

- Nalewajko, K., & Sikora, M. 2009, MNRAS, 392, 1205 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan, R., Li, J., & Tchekhovskoy, A. 2009, ApJ, 697, 1681 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Owen, F. N., Hardee, P. E., & Cornwell, T. J. 1989, ApJ, 340, 698 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Panaitescu, A., & Kumar, P. 2002, ApJ, 571, 779 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Perlman, E. S., Biretta, J. A., Zhou, F., et al. 1999, ApJ, 117, 2185 [Google Scholar]

- Perucho, M., Hanasz, M., Martí, J. M., & Sol, H. 2004, A&A, 427, 415 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Perucho, M., Kovalev, Y. Y., Lobanov, A. P., et al. 2012, ApJ, 749, 55 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Piran, T. 2004, Rev. Mod. Phys., 76, 1143 [Google Scholar]

- Pushkarev, A. B., & Kovalev, Y. Y. 2012, A&A, 544, A34 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Pushkarev, A. B., Kovalev, Y. Y., Lister, M. L., & Savolainen, T. 2009, A&A, 507, L33 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Pushkarev, A. B., Lister, M. L., Kovalev, Y. Y., & Savolainen, T. 2012, Proceedings of Fermi & Jansky – Our Evolving Understanding of AGN – eConf C1111101 [arXiv:1205.0659] [Google Scholar]

- Savolainen, T., Homan, D. C., Hovatta, T., et al. 2010, A&A, 512, A24 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Spruit, H. C. 2010, Theory of Magnetically Powered Jets, Lect. Notes Phys., 794, 233 [Google Scholar]

- Swain, M. R., & Bridle, A. H. 1998, ApJ, 507, L29 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tavecchio, F., & Ghisellini, G. 2008, MNRAS, 385, L98 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tchekhovskoy, A., McKinney, J. C., & Narayan, R. 2009, ApJ, 699, 1789 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tchekhovskoy, A., Narayan, R., & McKinney, J. C. 2010, New Astron., 15, 749 [Google Scholar]

- Urry, C. M., & Padovani, P. 1991, ApJ, 371, 60 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Urry, C. M., & Shafer, R. A. 1984, ApJ, 280, 569 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen, R. C., & Cohen, M. H. 1994, ApJ, 430, 467 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Vlahakis, N., & Konigl, A. 2004, ApJ, 605, 656 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zakamska, N. L., Begelman, M. C., & Blandford, R. D. 2008, ApJ, 679, 990 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Appendix A: Causal connection and Γθj

Here we discuss two different criteria for defining whether or a not a jet is causally connected for the simplistic case of a jet with radial velocity streamlines of constant speed. For jets with velocity shear, as we posit in this work, causal connection is more complicated than we have presented below, although we expect the following discussion to be approximately correct. First, the relativistic Mach number ℳ = βΓ/(βsΓs) (Konigl 1980) is sometimes used to define causal connection for supersonic jets by requiring θjℳ < 1, or Γθj < Γsβs/β (e.g., Komissarov et al. 2009). Second, causally connected jets are sometimes defined as those for which Γθj < 1 (e.g., Zakamska et al. 2008). We note that for relativistic jets with β ≈ 1 and an ultra-relativistic equation of state where the proper sound speed is Γsβs = 2− 1/2 ≈ 0.71, both of these causality criteria resemble one another: Γθj < 0.71 for the relativistic Mach number approach, and Γθj < 1 for the other. However, for magnetically dominated plasmas, the fast magnetosonic speed can approach the speed of light, thus no upper bound can be placed on Γsβs and these two criteria for causal connection give contradictory answers. Thus, a jet can have any value of Γθj and still in principle be causally connected, provided it is magnetically dominated enough. In particular, for jets with magnetization σ (Kennel & Coroniti 1984), the proper Alfvén speed is ΓAβA = σ1/2, thus the Mach number condition for the jet to be causally connected is Γθj < σ1/2 (e.g., Komissarov et al. 2009). Jets can then be causally connected even though Γθj ≫ 1, as long as σ is large enough (high σ implies the jet is Poynting flux dominated). Below, we discuss why these two criteria are different and conclude that the relativistic Mach angle analysis is usually the more appropriate criterion, even though it is only approximate.

θjℳ < 1 criterion: This criterion is only relevant for highly supersonic or supermagnetosonic jets, since for subsonic or transonic jets there is no limit on wave propagation.

The relativistic Mach number can be derived by assuming a flow with parallel velocity streamlines and by analyzing the observer frame angle a sound wave can make with respect to the flow direction, tanχ = β⊥/β∥. The relativistic Mach angle is then found by maximizing χ by varying χ′, the rest frame angle between the flow direction and the sound wave direction. This procedure gives cosχ′ = −βs/β and a maximum angle of sinχmax = 1/ℳ (Konigl 1980). Thus, χmax represents the largest observer frame angle a sound wave can make with respect to a supersonic flow. For this reason, jets where θj > χmax are assumed to be out of causal contact with themselves. However, this Mach angle analysis assumes a flow of parallel velocity streamlines, something that is not the case for conical jets.

For conical jets, jet sidewise expansion lengthens the signal crossing time compared to a

flow with parallel streamlines (e.g., a cylindrical jet). Causal connection can be

analyzed by making a simple estimate of a conical jet’s signal crossing time, assuming the

signal propagates at a speed βs in the local fluid rest frame

and makes an angle χ′ between the jet comoving frame signal

wave propagation direction and the local fluid streamline. We also assume that the jet

flow is radial with a half-opening angle of θj and a constant

Lorentz factor of Γ. In the observer frame the wave has a speed parallel to the local

streamline of  (A.1)and

a perpendicular speed of

(A.1)and

a perpendicular speed of  (A.2)For

simplicity we assume the emitted wave trajectory is such that

χ′ is constant. If the radial coordinate (centered on the

jet’s central engine) of the wave is r, then

dr = βrcdt.

In a time dt, the wave propagates in the polar direction an arc length of

ds = βθcdt.

In terms of polar angle, then, the signal propagation can be written as

dθ = βθcdt/r,

which, combined with the

dr = βrcdt,

can be solved for the time it takes for a signal to propagate through a polar angle

θj,

(A.2)For

simplicity we assume the emitted wave trajectory is such that

χ′ is constant. If the radial coordinate (centered on the

jet’s central engine) of the wave is r, then

dr = βrcdt.

In a time dt, the wave propagates in the polar direction an arc length of

ds = βθcdt.

In terms of polar angle, then, the signal propagation can be written as

dθ = βθcdt/r,

which, combined with the

dr = βrcdt,

can be solved for the time it takes for a signal to propagate through a polar angle

θj,  (A.3)where

r0 is the radial location of the initial wave emission. We

note that a different form of Eq. (A.3)

was derived in Kinoshita et al. (2004) and a

similar result was also found in Nakar et al.

(2003). If in the observer frame a sound wave has a trajectory such that

χ = 1/ℳ (i.e.,

χ′ = −βs/β),

then

βr/βθ ≈ ℳ

and βr ≈ β, yielding the

differential equation

dθ = (ℳr)-1dr. This

differential equation has the solution for polar angle through which the signal propagates

of

θ(r) = ℳ-1ln(r/r0)

with the associated signal crossing time of

(A.3)where

r0 is the radial location of the initial wave emission. We

note that a different form of Eq. (A.3)

was derived in Kinoshita et al. (2004) and a

similar result was also found in Nakar et al.

(2003). If in the observer frame a sound wave has a trajectory such that

χ = 1/ℳ (i.e.,

χ′ = −βs/β),

then

βr/βθ ≈ ℳ

and βr ≈ β, yielding the

differential equation

dθ = (ℳr)-1dr. This

differential equation has the solution for polar angle through which the signal propagates

of

θ(r) = ℳ-1ln(r/r0)

with the associated signal crossing time of  (A.4)assuming

ℳ ≫ 1. Equation (A.4) implies that jets

for which θjℳ ≫ 1 have

tcross ≈ (r0/c)exp(θjℳ),

effectively making such jets fall out of causal contact in the sense that the dynamic time

is longer than the jet expansion time

r0/c by a factor

exp(θjℳ).

(A.4)assuming

ℳ ≫ 1. Equation (A.4) implies that jets

for which θjℳ ≫ 1 have

tcross ≈ (r0/c)exp(θjℳ),

effectively making such jets fall out of causal contact in the sense that the dynamic time

is longer than the jet expansion time

r0/c by a factor

exp(θjℳ).

Accelerating conical jets are different in that they can have a causal horizon that

depends on the details of jet acceleration (Kinoshita et

al. 2004). An accelerating supersonic jet will have an increasing proper speed

and a decreasing (or constant) proper signal speed, which we parameterize as

ℳ = ℳ0(r/r0)b.

For a signal emitted at r0 that propagates at the Mach angle

relative to the local fluid streamline, then

dθ = (ℳr)-1dr has the

asymptotic solution  (A.5)That

is, disturbances located at radius r0 will propagate through a

polar angle θ∞ as r → ∞. Thus, in this

circumstance, the causal connection criterion becomes

θjℳ(r) < b-1.

(A.5)That

is, disturbances located at radius r0 will propagate through a

polar angle θ∞ as r → ∞. Thus, in this

circumstance, the causal connection criterion becomes

θjℳ(r) < b-1.

Γθj < 1 criterion: We

assume an initially cylindrical jet with speed β ≈ 1 and associated

Lorentz factor Γ ≫ 1, and let the radius of the cylindrical flow suddenly begin to expand

in the flow rest frame with velocity  perpendicular

to the symmetry axis. Transforming back into the observer frame then gives

perpendicular

to the symmetry axis. Transforming back into the observer frame then gives

, the

small angle the velocity stream lines make with the jet axis is now

, the

small angle the velocity stream lines make with the jet axis is now

(A.6)The

requirement that the jet cross section expands at less than the speed of light

(A.6)The

requirement that the jet cross section expands at less than the speed of light

implies

that (Zakamska et al. 2008)

implies

that (Zakamska et al. 2008)

(A.7)Thus,

requiring that Γθj < 1 is an important

constraint for jet flows that are initially close to cylindrical, and for some reason

undergo expansion. We note, however, that this constraint is not important for flows that

are initially not collimated, such as the highly relativistic equatorial outflows from

pulsars that power pulsar wind nebulae (Kennel &

Coroniti 1984).

(A.7)Thus,

requiring that Γθj < 1 is an important

constraint for jet flows that are initially close to cylindrical, and for some reason

undergo expansion. We note, however, that this constraint is not important for flows that

are initially not collimated, such as the highly relativistic equatorial outflows from

pulsars that power pulsar wind nebulae (Kennel &

Coroniti 1984).

Alternatively, Γθj can be an important quantity if the sound

wave emission direction in the local rest frame is defined as perpendicular to the local

flow direction, i.e.,

χ′ = π/2, as could be

the case if the wave is restricted to a thin spherical shell (which may be relevant for

GRBs, Lyutikov et al. 2003; Kinoshita et al. 2004), so that

βθ = βs/Γ

and βr = β. In this case,

the sound crossing time from Eq. (A.3)

becomes  (A.8)For

jets with β ≈ 1, βs ≈ 1, and

Γθj ≫ 1, then

tcross ≈ (r0/c)exp(Γθj),

showing that in this case Γθj plays the same role that

θjℳ does in the general case for determining an effective

causal condition.

(A.8)For

jets with β ≈ 1, βs ≈ 1, and

Γθj ≫ 1, then

tcross ≈ (r0/c)exp(Γθj),

showing that in this case Γθj plays the same role that

θjℳ does in the general case for determining an effective

causal condition.

All Tables

Parameter values (both best fit and assigned) for six different cases along with 68% confidence intervals where relevant.

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Meridional slice of a jet illustrating two cases: (i) jets aligned close to the line of sight where emission is dominated by the fast inner spine; and (ii) more misaligned jets where the emission from outer slower layers contributes as well. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Doppler factor and ρeff as a function of a jet’s apparent half-opening angle θapp. The semi-logarithmic Doppler factor plot in the upper panel is for a jet with Γ = 10 and ρ = 0.21, and uses Eq. (4) to convert θapp to θob. The lower panel plot shows ρeff as a function of θapp from Eq. (9) using ρ = 0.21 and fsh = 0.33, the best fit values found in Sect. 3.2. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 Example best fits for two cases are shown in the form of cumulative distribution functions (CDF, upper panel) and probability density functions (PDF, lower panel). The two cases shown, “no shear (iii)” (dash-dotted line) and “shear (i)” (dotted line), both have the same number of free parameters (two), but the shear (i) model clearly fits the data better. The data is represented as a solid line (upper panel) or histogram (lower panel). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4 68% and 95% confidence contours from Monte Carlo error analysis for the best-fit parameters ρ, a, and fsh, from the case of shear (iii). The central star shows the MLE of the parameters. We emphasize the a vs. ρ plot since there is a fiducial value for a (=2, vertical dotted line), and ρ has constraints set on it by Jorstad et al. (2005) and Pushkarev et al. (2009). |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.