| Issue |

A&A

Volume 555, July 2013

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A14 | |

| Number of page(s) | 18 | |

| Section | Interstellar and circumstellar matter | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201220625 | |

| Published online | 19 June 2013 | |

Photodissociation of interstellar N2⋆

1

Leiden Observatory, Leiden University,

PO Box 9513,

2300 RA

Leiden,

The Netherlands

e-mail:

li@strw.leidenuniv.nl

2

Department of Physics, Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA

02181,

USA

3

Department of Physics and Astronomy, LaserLaB, VU

University, de Boelelaan

1081, 1081 HV

Amsterdam, The

Netherlands

4

Department of Astronomy, University of Michigan,

500 Church Street, Ann Arbor, MI

48109-1042,

USA

5

Research School of Physics and Engineering, The Australian

National University, Canberra, ACT

0200,

Australia

6

Max-Planck Institut für Extraterrestrische Physik (MPE),

Giessenbachstr. 1,

85748

Garching,

Germany

Received:

24

October

2012

Accepted:

15

April

2013

Context. Molecular nitrogen is one of the key species in the chemistry of interstellar clouds and protoplanetary disks, but its photodissociation under interstellar conditions has never been properly studied. The partitioning of nitrogen between N and N2 controls the formation of more complex prebiotic nitrogen-containing species.

Aims. The aim of this work is to gain a better understanding of the interstellar N2 photodissociation processes based on recent detailed theoretical and experimental work and to provide accurate rates for use in chemical models.

Methods. We used an approach similar to that adopted for CO in which we simulated the full high-resolution line-by-line absorption + dissociation spectrum of N2 over the relevant 912–1000 Å wavelength range, by using a quantum-mechanical model which solves the coupled-channels Schrödinger equation. The simulated N2 spectra were compared with the absorption spectra of H2, H, CO, and dust to compute photodissociation rates in various radiation fields and shielding functions. The effects of the new rates in interstellar cloud models were illustrated for diffuse and translucent clouds, a dense photon dominated region and a protoplanetary disk.

Results. The unattenuated photodissociation rate in the Draine (1978, ApJS, 36, 595) radiation field assuming an N2 excitation temperature of 50 K is 1.65 × 10-10 s-1, with an uncertainty of only 10%. Most of the photodissociation occurs through bands in the 957–980 Å range. The N2 rate depends slightly on the temperature through the variation of predissociation probabilities with rotational quantum number for some bands. Shielding functions are provided for a range of H2 and H column densities, with H2 being much more effective than H in reducing the N2 rate inside a cloud. Shielding by CO is not effective. The new rates are 28% lower than the previously recommended values. Nevertheless, diffuse cloud models still fail to reproduce the possible detection of interstellar N2 except for unusually high densities and/or low incident UV radiation fields. The transition of N → N2 occurs at nearly the same depth into a cloud as that of C+ → C → CO. The orders-of-magnitude lower N2 photodissociation rates in clouds exposed to black-body radiation fields of only 4000 K can qualitatively explain the lack of active nitrogen chemistry observed in the inner disks around cool stars.

Conclusions. Accurate photodissociation rates for N2 as a function of depth into a cloud are now available that can be applied to a wide variety of astrophysical environments.

Key words: astrochemistry / stars: formation / molecular processes / interplanetary medium / photon-dominated region (PDR) / ultraviolet: planetary systems

Appendices are available in electronic form at http://www.aanda.org

© ESO, 2013

1. Introduction

Nitrogen is one of the most abundant elements in the universe and an essential ingredient for building prebiotic organic molecules. In interstellar clouds, its main gas-phase reservoirs are N and N2, with the balance between these species determined by the balance of the chemical reactions that form and destroy N2. If nitrogen is primarily in atomic form, a rich nitrogen chemistry can occur leading to ammonia, nitriles and other nitrogen compounds. On the other hand, little such chemistry ensues if nitrogen is locked up in the very stable N2 molecule. The latter situation is similar to that of carbon with few carbon-chain molecules being produced when most of the volatile carbon is locked up in CO (Langer & Graedel 1989; Bettens et al. 1995).

Direct observation of extrasolar N2 is difficult because, unlike CO, it lacks strong pure rotational or vibrational lines. N2 is well studied at various locations within our solar system through its electronic transitions at ultraviolet wavelengths (e.g., Strobel 1982; Meier et al. 1991; Wayne 2000; Liang et al. 2007) and a detection in interstellar space has been claimed through UV absorption lines in a diffuse cloud toward the bright background star HD 124314 (Knauth et al. 2004). In dense clouds well shielded from UV radiation, most nitrogen is expected to exist as N2 (e.g., Herbst & Klemperer 1973; Woodall et al. 2007) but can only be detected indirectly through the protonated ion N2H+ (Turner 1974; Herbst et al. 1977) or its deuterated form N2D+. N2H+ emission is indeed widely observed in dense cores (e.g., Bergin et al. 2002; Crapsi et al. 2005), star-forming regions (Fontani et al. 2011; Tobin et al. 2012), protoplanetary disks (Dutrey et al. 2007; Öberg et al. 2010) and external galaxies (Mauersberger & Henkel 1991; Meier & Turner 2005; Muller et al. 2011).

Photodissociation is the primary destruction route of N2 in any region where UV photons are present. Current models of diffuse and translucent interstellar clouds are unable to reproduce the possible detection of N2 for one such cloud (Knauth et al. 2004). One possible explanation is that the adopted N2 photodissociation rate is incorrect. Even in dense cores, not all nitrogen appears to have been transformed to molecular form (Maret et al. 2006; Daranlot et al. 2012). Observations of HCN in the surface layers of protoplanetary disks suggest that the nitrogen chemistry is strongly affected by whether or not a star has sufficiently hard UV radiation to photodissociate N2 (Pascucci et al. 2009). Thus, not only the absolute photodissociation rate but also its wavelength dependence is relevant. All of these astronomical puzzles make a thorough study of the interstellar N2 photodissociation very timely.

In contrast with many other simple diatomic molecules, the photodissociation of interstellar N2 has never been properly studied (van Dishoeck 1988; van Dishoeck et al. 2006). The reason for this is that the photodissociation of N2, similarly to CO, is initiated by line absorptions at wavelengths below 1000 Å (1100 Å for CO), where high-resolution laboratory spectroscopy has been difficult. To compute the absolute rate and to treat the depth dependence of the photodissociation correctly, the full high-resolution spectrum of the dissociating transitions needs to be known. Because the absorbing lines become optically thick for modest N2 column densities, the molecule can shield itself against the dissociating radiation deeper into the cloud. Moreover, these lines can be shielded by lines of more abundant species such as H, H2 and CO. Until recently, accurate N2 molecular data to simulate these processes were not available. Thanks to a concerted laboratory (e.g., Ajello et al. 1989; Helm et al. 1993; Sprengers et al. 2003, 2004, 2005; Stark et al. 2008; Lewis et al. 2008b; Heays et al. 2009, 2011) and theoretical (e.g., Spelsberg & Meyer 2001; Lewis et al. 2005a,b, 2008c,a; Haverd et al. 2005; Ndome et al. 2008) effort over the past two decades, this information is now available.

In this paper, we use a high resolution model spectrum of the absorption and dissociation of N2 together with simulated spectra of H, H2 and CO to determine the interstellar N2 photodissociation rate and its variation with depth into a cloud. The effect of the new rates on interstellar N2 abundances is illustrated through a few representative cloud models. In particular, the N2 abundance in diffuse and translucent clouds is revisited to investigate whether the new rates alleviate the discrepancy between models and the possible detection of N2 in one cloud (Knauth et al. 2004). The data presented here can be applied to a wide range of astrochemical models, including interstellar clouds in the local and high redshift universe, protoplanetary disks and exo-planetary atmospheres. The 14N15N photodissociation rate and isotope selective interstellar processes will be discussed in an upcoming paper (Heays et al. in prep.) and have been discussed in the context of the chemistry of Titan by Liang et al. (2007).

2. Photodissociation processes of N2

2.1. Photoabsorption and photodissociation spectrum

The closed-shell diatomic molecule N2 has a dissociation energy of 78 715

cm-1 (9.76 eV, 1270 Å) (Huber &

Herzberg 1979), making it one of the most stable molecules in nature.

Electric-dipole-allowed photoabsorption and predissociation in N2 starts only

in the extreme ultraviolet spectral region, at wavelengths shorter than 1000 Å. The

molecular-orbital (MO) configuration of the  ground state of N2 is

ground state of N2 is  (1)Electric-dipole-allowed

transitions from the ground state access only states of

(1)Electric-dipole-allowed

transitions from the ground state access only states of

and

and

symmetry. In the region below the cutoff energy of the interstellar radiation field of

110 000 cm-1 (13.6 eV, 912 Å), five such states are accessible: the

c′ and

symmetry. In the region below the cutoff energy of the interstellar radiation field of

110 000 cm-1 (13.6 eV, 912 Å), five such states are accessible: the

c′ and  states, and the c, o, and b 1Πu

states. The c′, c, and o

states (sometimes labeled

states, and the c, o, and b 1Πu

states. The c′, c, and o

states (sometimes labeled  ,

c3, and o3; respectively) have

Rydberg character, the relevant transitions corresponding to single-electron excitations

from the 3σg or

1πu orbitals into a Rydberg orbital. On the

other hand, the b′ and b states are valence

states of mixed MO configurations accessed by transitions in which one or two electrons

are excited into antibonding orbitals. The relevant potential-energy curves (PECs) for

these

,

c3, and o3; respectively) have

Rydberg character, the relevant transitions corresponding to single-electron excitations

from the 3σg or

1πu orbitals into a Rydberg orbital. On the

other hand, the b′ and b states are valence

states of mixed MO configurations accessed by transitions in which one or two electrons

are excited into antibonding orbitals. The relevant potential-energy curves (PECs) for

these  and

and

states

are shown in Fig. 1, in blue and black, respectively.

The c′ and c states, whose PECs have the

smallest equilibrium internuclear distance in Fig. 1,

are the first members of Rydberg series converging on the ground state of the

N

states

are shown in Fig. 1, in blue and black, respectively.

The c′ and c states, whose PECs have the

smallest equilibrium internuclear distance in Fig. 1,

are the first members of Rydberg series converging on the ground state of the

N ion, X

ion, X , while

the o state is the first member of the series converging on the first

ionic excited state, A

, while

the o state is the first member of the series converging on the first

ionic excited state, A . In the case

of the b′ and b valence states, the extended

widths of the corresponding PECs in Fig. 1 are due to

the aforementioned configurational mixing. In addition, there are significant

electrostatic interactions within the manifolds of a given symmetry, Rydberg-valence for

. In the case

of the b′ and b valence states, the extended

widths of the corresponding PECs in Fig. 1 are due to

the aforementioned configurational mixing. In addition, there are significant

electrostatic interactions within the manifolds of a given symmetry, Rydberg-valence for

, and

Rydberg-valence and Rydberg-Rydberg for

, and

Rydberg-valence and Rydberg-Rydberg for  ,

since the MO configurations of all of the isosymmetric states differ in exactly two of the

occupied electron orbitals (Lefebvre-Brion & Field

2004). The PECs in Fig. 1 are shown in the diabatic (crossing) representation.

,

since the MO configurations of all of the isosymmetric states differ in exactly two of the

occupied electron orbitals (Lefebvre-Brion & Field

2004). The PECs in Fig. 1 are shown in the diabatic (crossing) representation.

|

Fig. 1 Diabatic-basis potential-energy curves for electronic states of N2

relevant to interstellar photodissociation. Blue curves:

|

Most of the rovibrational levels of the singlet excited states are predissociated, i.e.,

the molecule is initially bound following photoabsorption, but then dissociates on

timescales of a nanosecond or less due to direct or indirect coupling to a dissociative

continuum. For the  states

considered here, spin-orbit coupling to the strongly-coupled and -predissociated

states

considered here, spin-orbit coupling to the strongly-coupled and -predissociated

manifold (red

PECs in Fig. 1), with ultimate dissociation via the

C′ state, provides the predissociation mechanism (Lewis et al. 2005a, 2008c), with a minor contribution

from a crossing by the

manifold (red

PECs in Fig. 1), with ultimate dissociation via the

C′ state, provides the predissociation mechanism (Lewis et al. 2005a, 2008c), with a minor contribution

from a crossing by the  state (green PEC in Fig. 1) at higher energies. For

the

state (green PEC in Fig. 1) at higher energies. For

the  states,

two mechanisms are important (Heays 2011): first, a

similar spin-orbit coupling to the

states,

two mechanisms are important (Heays 2011): first, a

similar spin-orbit coupling to the  manifold,

solely responsible for predissociation in the absence of rotation, and second, rotational

coupling between the

manifold,

solely responsible for predissociation in the absence of rotation, and second, rotational

coupling between the  and

and

manifolds,

followed by the

manifolds,

followed by the  predissociation described above. For the wavelengths considered here, as implied by Fig.

1, these mechanisms result in primarily

N(4S) +N(2D) dissociation

products, i.e., one of the nitrogen atoms is formed in an excited electronic state which

decays on a timescale of 17 h into the ground state N(4S).

This is consistent with the observations of Walter et al.

(1993) who failed to detect direct

N(4S) +N(4S) dissociation

products.

predissociation described above. For the wavelengths considered here, as implied by Fig.

1, these mechanisms result in primarily

N(4S) +N(2D) dissociation

products, i.e., one of the nitrogen atoms is formed in an excited electronic state which

decays on a timescale of 17 h into the ground state N(4S).

This is consistent with the observations of Walter et al.

(1993) who failed to detect direct

N(4S) +N(4S) dissociation

products.

The line-by-line models previously used to compute the N2 photodissociation rate require knowledge of the wavelengths, oscillator strengths, lifetimes, and predissociation probabilities of (transitions to) all rovibrational levels associated with the coupled excited singlet states. For the case of the isoelectronic molecule CO, molecular models have been built previously by specifying the term values, rotational and vibrational constants, oscillator strengths, Einstein A coefficients, and predissociation probabilities for each excited electronic state (e.g., van Dishoeck & Black 1988; Viala et al. 1988; Lee et al. 1996; Visser et al. 2009). These have allowed the rotationally-resolved absorption spectra of CO and its isotopologues to be constructed using simple scaling relations. Such models must be validated by a large quantity of laboratory data and have been shown to be incorrect when strong interactions occur between electronic states and their differing energetics. For the case of N2, it is known that there are many wide-scale perturbations, together with rapid dependences of oscillator strengths and predissociation linewidths on rotational quantum number J, and strong, irregular isotopic effects. It is impossible to fully reproduce these effects using only a few spectroscopic constants.

The best way to simulate the N2 spectrum, and the method employed here, is, at

each energy, to solve the full radial diabatic coupled-channel Schrödinger equation (CSE)

for the coupled electronic states described above, including all electrostatic,

spin-orbit, and rotational couplings, using the quantum-mechanical methods of van Dishoeck et al. (1984). This is a

physically-based technique, with great predictive powers which enables

confidence in the computed spectrum in regions lacking experimental confirmation, even

where perturbations are present. Furthermore, computations of isotopic spectra require

only the change of a single parameter, i.e., the reduced molecular mass, in the molecular

model: the results can be guaranteed since the underlying physics is the same for all

isotopologues. The same cannot be said for the line-by-line models such as those employed

for CO, which would also benefit from a CSE approach. The detailed CSE model for

N2 employed here has been described in Heays

(2011)1 incorporates earlier models of the

(Lewis et al. 2005a; Haverd et al. 2005) and

(Lewis et al. 2005a; Haverd et al. 2005) and  states (Lewis et al. 2008c) and has been tested extensively

against laboratory data, including high-resolution spectra obtained at the SOLEIL

synchrotron facility (Heays 2011; Heays et al. 2011). A complete discussion of the CSE

model and a full listing of computed spectroscopic data is deferred to Heays et al. (in

prep.).

states (Lewis et al. 2008c) and has been tested extensively

against laboratory data, including high-resolution spectra obtained at the SOLEIL

synchrotron facility (Heays 2011; Heays et al. 2011). A complete discussion of the CSE

model and a full listing of computed spectroscopic data is deferred to Heays et al. (in

prep.).

For a given rotational-branch transition, combining the excited-state coupled-channel wavefuction with the X-state radial wavefunction and appropriate diabatic allowed transition-moment components yields the corresponding (continuous with wavelength) photoabsorption cross section, with the computed linewidths providing the required predissociation lifetime information. Total cross sections for a given temperature, assuming local thermodynamic equilibrium, are formed by summing the individual branch cross sections, weighted by appropriate Boltzmann and Hönl-London factors, and including rotational levels with J as high as 50.

CSE photoabsorption cross sections, σabs, are computed here over the wavelength range 912–1000 Å with a step size of 0.0001 Å, and for temperatures of 10, 50, 100, 500, and 1000 K. The Doppler broadening of the spectral lines is taken into account by convolution with a Gaussian profile having a thermal line width.

A 10% uncertainty is estimated for the total magnitude of the photoabsorption cross section and principally arises from the absolute uncertainty of the calibrating laboratory spectra (Haverd et al. 2005; Heays 2011). The laboratory measurements in question were recorded at 300 K or below, so the uncertainty may be somewhat larger for calculations employing an extrapolation to 1000 K. Additionally, 3% of the 1000 K ground state population will be in the first vibrational level, leading to a slight redistribution of the absorption cross section into hot bands. This is considered in the model calculations.

|

Fig. 2 Top: branching to various decay channels of the c′(v′ = 0) excited-state of N2 as a function of total rotational quantum number, J. The figure includes spontaneous emission to several non-dissociative ground state vibrational levels (v′′ = 0,1 and 2) and decay due to predissociation (dis.). Bottom: fractional population of the N2 ground state in its lowest vibrational level as a function of J and for several excitation temperatures. The 2:1 ratio of populations for even:odd J levels arises from the combined rotational and nuclear spin statistics. |

Photodissociation cross sections, σpd = η × σabs, are obtained from the photoabsorption cross sections by comparing the predissociation and radiative lifetimes for each rovibrational level. The predissociation efficiency η is then given by η = 1 − τtot/τrad, where τtot is the inverse of the sum of the radiative and predissociation rates. For almost all transitions, η ≃ 1: significant corrections for partial dissociation are needed only for the b − X(1,0) and c′ − X(0,0) bands near 986 and 959 Å, respectively (Lewis et al. 2005b; Liu et al. 2008; Sprengers et al. 2004; Wu et al. 2012). For example, the top panel of Fig. 2 illustrates the CSE-computed branching ratio between spontaneous emission back to the ground state and dissociation as a function of rotational level for c′ − X(0,0). Such calculations were performed for all bands appearing between 955 and 991 Å. The difference between calculated absorption and dissociation cross sections for the very-strongly absorbing c′ − X(0,0) band is demonstrated in Fig. 3, revealing a significant alteration of the band profile once the dissociation efficiency is considered.

|

Fig. 3 CSE-calculated absorption cross section (blue) of the c′(v′ = 0) level of N2 assuming an excitation temperature of 300 K. Also shown is a dissociation cross section (red) which has been corrected for the non-unity dissociation efficiency, ηJ, of this band (see Fig. 2). |

The bottom panel of Fig. 2 shows the thermal population for various J levels of the ground vibrational state, assuming several temperatures. By comparing this with the top panel of Fig. 2 it can be seen that the dissociation fraction for this band will depend significantly on the temperature.

2.2. Photodissociation rates

The photodissociation rate, kpd, of N2 exposed to

UV radiation can be calculated according to  (2)where the

photodissociation cross section, σpd, is in units of

cm2 and I is the mean intensity of the radiation in photons

cm-2 s-1 Å-1 as a function of wavelength,

λ, in units of Å. The unattenuated interstellar radiation field

according to Draine (1978) is used in most of the

following calculations and is given by

(2)where the

photodissociation cross section, σpd, is in units of

cm2 and I is the mean intensity of the radiation in photons

cm-2 s-1 Å-1 as a function of wavelength,

λ, in units of Å. The unattenuated interstellar radiation field

according to Draine (1978) is used in most of the

following calculations and is given by  (3)Inside a cloud,

self-shielding, shielding by H, H2, CO and other molecules, and continuum

shielding by dust all reduce the photodissociation rate below its unattenuated value

k0. The shielding function is defined to be

(3)Inside a cloud,

self-shielding, shielding by H, H2, CO and other molecules, and continuum

shielding by dust all reduce the photodissociation rate below its unattenuated value

k0. The shielding function is defined to be  (4)and

can be split into a self-shielding,

(4)and

can be split into a self-shielding, ![\begin{equation} \Theta_{\rm SS} = \frac{\int I(\lambda) \exp\left[-N({\rm N}_2) \sigma_{\rm abs}(\lambda)\right]\sigma_{\rm pd}(\lambda)\,{\rm d}\lambda}{\int I(\lambda)\,\sigma_{\rm pd}(\lambda)\,{\rm d}\lambda}, \label{eq:self shielding function} \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/07/aa20625-12/aa20625-12-eq61.png) (5)and a

mutual-shielding part,

(5)and a

mutual-shielding part, ![\begin{equation} \Theta_{\rm MS} = \frac{\int I(\lambda)\exp\left[-N(X) \sigma_{\rm X}(\lambda)\right]\sigma_{\rm pd}(\lambda)\,{\rm d}\lambda}{\int I(\lambda)\,\sigma_{\rm pd}(\lambda)\,{\rm d}\lambda}\cdot \label{eq:mutual shielding function} \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/07/aa20625-12/aa20625-12-eq62.png) (6)Here,

X = H, H2 or CO and N is the column density

of the various species. A dust extinction term,

exp(−γAV), can be written in place of the

exponential term in Eq. (6) where AV is the optical depth in

magnitudes and γ depends on the assumed properties of the dust. This is

further discussed in Sect. 3.3. In all cases, the

integrals above are computed between 912 and 1000 Å.

(6)Here,

X = H, H2 or CO and N is the column density

of the various species. A dust extinction term,

exp(−γAV), can be written in place of the

exponential term in Eq. (6) where AV is the optical depth in

magnitudes and γ depends on the assumed properties of the dust. This is

further discussed in Sect. 3.3. In all cases, the

integrals above are computed between 912 and 1000 Å.

3. Results

3.1. Unattenuated interstellar rate

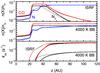

Figure 4 shows model spectra of N2 and H2 + H absorption for excitation temperatures of 50 and 1000 K. At 50 K the N2 spectrum is made up of prominent well-separated bands. These represent excitation to a range of vibrational levels attributable to the five accessible electronic states. In contrast, the spectrum simulating a temperature of 1000 K includes the excitation of many more rotational levels and has few sizable windows between bands.

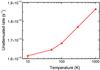

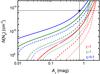

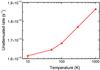

Unshielded photodissociation rates of N2 immersed in a Draine (1978) field were calculated from the model photodissociation cross section using Eqs. (2) and (3), and assuming a range of excitation temperatures. These are plotted in Fig. 5 and listed in Table 1. The rate at 50 K is 1.65 × 10-10 s-1, where the uncertainty of 10% only reflects the uncertainty in the cross sections, not the radiation field (see below). This new value is 28% lower than the value of 2.30 × 10-10 s-1 recommended by van Dishoeck (1988). The latter estimate was based on the best available N2 spectroscopy at the time, and has an order-of-magnitude uncertainty. For comparison, the unshielded photodissociation rate of N2 at low T is around 35% smaller than that of CO computed by Visser et al. (2009).

|

Fig. 4 Simulated absorption spectra for N2 (black) and H2 + H (red) in the wavelength range 912–1000 Å assuming thermal excitation temperatures of 50 (top) and 1000 K (bottom). The column density of N2 is 1015 cm-2 and values for H2 and H are taken to be half of the observed column densities in the well-studied diffuse cloud toward ζ Oph, as is appropriate for the center of the cloud: N(H2) = 2.1 × 1020 and N(H) = 2.6 × 1020 cm-2. The model H2 Doppler width is 3 km s-1. Also shown is the H2 + H absorption spectrum (blue) toward ζ Oph using the observed column densities for individual J levels, showing enhanced non-thermal excitation of H2 in the higher J levels. The asterisks indicate the c′(0) (Band 20) and c(0) (Band 21) bands, respectively, detected in absorption toward HD 124314. |

Table 2 summarizes the contributions of individual bands to the total unattenuated dissociation rate. It is seen that the main contributions arise from bands 12, 21, 22, 23 and 24. Hence, the key wavelength ranges responsible for the photodissociation of N2 are around 940 Å and between 957–980 Å.

The calculated unattenuated rate of N2 increases with increasing temperature so that the value at 1000 K, 1.86 × 10-10 s-1, is 15% higher than for 10 K. This is largely due to a variable but overall increase with rotational quantum number J of the photodissociation branching ratios of the c′(v = 0) and b(v = 1) states. This can be seen in Fig. 2 for the c′(v′ = 0) state, where at 10 K all of the excited population is in levels with J = 0−3. These levels have a low predissociation probability and hardly contribute to the photodissociation rate. At higher temperatures, the excited population shifts to higher J, and at 1000 K the distribution maximum occurs around J = 15−20 for which the branching ratio to dissociation is much higher.

The rate obviously depends on the choice of radiation field. For the alternative formulations of Habing (1968), Gondhalekar et al. (1980) and Mathis et al. (1983), the unattenuated rates are 1.45, 1.34 and 1.51 × 10-10 s-1 at 50 K, respectively. Additionally, Table 1 considers the unattenuated rates of N2 assuming different blackbody radiation fields. In these calculations, the intensities have been normalized such that the integrated values from 912–2050 Å are the same as those of the Draine (1978) field. The adopted dilution factors are 1.9 × 10-9, 3.4 × 10-12, 1.2 × 10-13, 1.6 × 10-14, and 1.6 × 10-16 for blackbody temperatures of 4000, 6000, 8000, 10 000 and 20 000 K, respectively. The value of the unattenuated rate of N2 at 4000 K (cool star) is 6 orders of magnitude smaller than that at 20 000 K (hot star), and increases steeply with stellar effective temperature. The photodissociation rate of N2 at 20 000 K is comparable to that in the Draine interstellar field, 1.65 × 10-10 s-1. The calculated photodissociation rates for temperatures of 4000 and 10 000 K are close to those recommended by van Dishoeck et al. (2006).

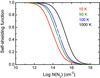

3.2. Self-shielding

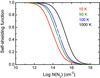

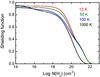

Although self-shielding is generally less important than mutual shielding for the case of N2 (see Sect. 3.3), it is potentially important in protoplanetary disks and has been proposed to be responsible for the enrichment of 15N in bulk chondrites and terrestrial planets (Lyons 2009, 2010). In this work, we compute the self-shielding functions of N2 at excitation temperatures of 10, 100 and 1000 K using the model absorption spectrum. Since this spectrum is constructed using thermal line widths and no turbulent broadening, it provides the maximum amount of shielding. For reference, the thermal widths of N2 at 10, 100 and 1000 K correspond to full widths at half maximum of 0.1, 0.3 and 1.0 km s-1.

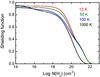

As can be seen in Fig. 6, the photodissociation of N2 is free of self-shielding up to a column density of around 1012 cm-2, but is fully shielded by 1018 cm-2. For intermediate N2 column densities the self-shielding function increases with increasing excitation temperature. There are two reasons for this (Visser et al. 2009). First, the optical depth of each line increases linearly with the thermal population of its corresponding lower-state rotational level, but the self-shielding increases nonlinearly according to Eq. (5). Then, because the ground state population at higher temperatures is distributed over more levels (see Fig. 2) there is an overall decrease in the effectiveness of self-shielding. The second effect arises from the individual line profiles, which are constructed to have thermal broadening. Those lines appearing in the 1000 K spectrum are then 10 times broader than those at 10 K, leading to decreased peak optical depth at the line center and less effective self-shielding over the whole line profile.

3.3. Shielding by H2, H and CO

The wavelength range over which N2 can be photodissociated is exactly the same range over which H2, H and CO absorb strongly. The amount by which N2 is shielded depends on the column densities of each of these species and is characterized by the shielding function of Eq. (6).

|

Fig. 5 Unattenuated photodissociation rates of N2 immersed in a Draine (1978) field at various excitation temperatures. |

Figure 4 overlays absorption spectra for N2 and H+H2 combined. Two forms of the latter are included: a representative example spectrum deduced from observations of H2(J) and H column densities of the well-studied and commonly-referenced diffuse cloud toward ζ Oph; and a simulated spectrum using column densities of 2.1 × 1020 and 2.6 × 1020 cm-2 for H2 and H, respectively, and assuming purely thermal excitation of H2. The H2 molecular data adopted for the synthetic spectra are those of Abgrall et al. (1993a,b) and were obtained from the Meudon PDR code website (Le Petit et al. 2006). The assumed column densities were taken to be half those of the observed ζ Oph cloud, as is appropriate for radiation penetrating to its center, and an excitation temperature of 50 K was used for the H2+H and N2 thermal models. The principal difference between observed and thermal H2+H spectra is the appearance of additional lines in the observed spectrum from non-thermally populated higher-J levels. Thermal excitation H2 spectra are used throughout the following mutual-shielding calculations, and do not include extrathermal excitations such as UV pumping. This negligence leads to a slight (approximately 3%) underestimate of shielding for the case of the ζ Oph cloud. A magnified version of the spectra in Fig. 4 is included in the appendix, and it is apparent that the ranges containing significant N2 absorption and minimal shielding by H and H2 are 919.8–920.2, 921.2–921.6, 922.6–923.1, 925.8–926.1, 935.1–935.4, 939.9–940.3, 942.3–942.8, 958.1–958.9, 959.0–959.1, 960.1–960.8 and 978.8–979.5 Å.

Unattenuated photodissociation rates of N2 (excitation temperature 50 K) in a blackbody radiation field at various temperatures, TBB.

Contributions of different bands to N2 photodissociation at 50 K at the edge (unattenuated photodissociation) and in the center of the ζ Oph diffuse cloud.

The calculated N2 photodissociation rate at the center of the ζ Oph cloud is 6.96 × 10-11 s-1, corresponding to 58% shielding by H2+H. Table 2 summarizes the contributions to the photodissociation rate of individual bands at the edge of the cloud (unshielded) and at its center. The pattern of increasing and decreasing significance of individual N2 bands under the influence of shielding is easily matched to the occurrence of overlapping features in Fig. 4a. The heavy shielding of bands 22 and 23 has a particularly large effect on the total photodissociation rate, the relative importance of the lightly shielded band 14 increases significantly in the center, and the 957–980 Å wavelength range remains particularly important for photodissociation throughout the cloud.

A similar investigation was performed considering the shielding of N2 by CO. Simulated absorption spectra for both molecules are shown in Fig. 7, where the CO spectrum was generated by the photoabsorption model of Visser et al. (2009) assuming a column density of 1015 cm-2, close to half of the observed ζ Oph value. Both spectra exhibit a complex pattern of bands so that overlaps are infrequent and do not occur at all in the most important photodissociation range, 957–980 Å. In this range CO hardly affects N2 and, in general, shielding by H2 and H is sufficiently dominant that the additional influence of CO can be neglected.

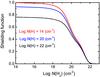

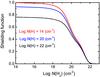

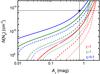

Two-dimensional shielding functions for a range of H2 and H column densities have been calculated. These are tabulated in Table 3 and shown graphically in Fig. 8. For these calculations an excitation temperature of 50 K was assumed for both N2 and H2, and b(H2) (the nonthermal broadening) was set to 3 km s-1. Obviously, the shielding function decreases with increasing N(H2) and N(H), but H2 plays the more important role (as is the case for the shielding of CO; Visser et al. 2009). Specifically, N2 is close to fully shielded (Θ < 2%) when N(H2) = 1022 cm-2, and totally shielded by 1023 cm-2. Electronic tables of the calculated shielding functions can be obtained from http://www.strw.leidenuniv.nl/~ewine/photo.

|

Fig. 6 N2 self-shielding as a function of column density, N(N2), for excitation temperatures of 10, 50, 100 and 1000 K. |

|

Fig. 7 Top: comparison of N2 (black) and CO (blue) model absorption spectra between 912 and 1000 Å assuming an excitation temperature of 50 K for both molecules. The N2 and CO column densities are both 1015 cm-2. Bottom: blow-up of the above spectra for the wavelength region 956–980 Å. |

Since N2 does not possess a permanent dipole moment, radiative decay from excited rotational levels of its electronic-vibrational ground state is slow. Then, the excitation temperature of N2 is likely to be higher than that of CO and other molecules, and closer to the kinetic temperature. The effect of temperature on shielding by H2 + H was investigated and is illustrated in Fig. 9. The same excitation temperatures are adopted for H2 and N2 because both are zero-dipole-moment molecules. The calculated shielding functions are somewhat erratic, and even show a peculiar non-monotonic temperature dependence at low H2 column density. This arises from the small degree of overlap occurring between atomic H lines and N2 bands. The distribution of N2 lines over additional rotational transitions at higher temperatures leads to the variability of Fig. 9 and illustrates the need for high-resolution reference spectra in these kinds of applications. For significant H2 column densities, and in contrast with N2 self-shielding, the amount of shielding increases with increasing temperature. This results from a H2 population that is spread over more rotational levels at higher temperatures, leading to an absorption spectrum featuring more lines available to shield N2. This is clearly evident when comparing the various curves in Fig. 4.

Table 4 compares the H+H2 shielding of N2 with the CO shielding calculations of Visser et al. (2009). The two molecules follow a similar pattern, within 50%, up to N(H2) = 1022 cm-2. This difference becomes more significant when N(H2) = 1023 cm-2, but photodissociation has long ceased to be important as an N2 destruction mechanism by then.

3.4. Shielding by dust

Dust grains compete with molecules in the cloud by also absorbing UV photons. For the 912–1000 Å wavelength range, the attenuation by dust is largely independent of wavelength and can be taken into account by an additional shielding term exp(−γAV) (van Dishoeck et al. 2006). For the wavelength range appropriate for N2, a value of γ = 3.53 is found, using the method of Roberge et al. (1981) and standard diffuse-cloud grain properties of Roberge et al. (1991). For larger dust grains of a few μm in size, such as is appropriate for protoplanetary disks, γ ≈ 0.6 (van Dishoeck et al. 2006). The visual extinction AV is computed from the total hydrogen column NH = N(H) + 2N(H2) through the relation AV = NH/1.6 × 1021, based on Savage et al. (1977).

For diffuse clouds with total visual extinctions around 1 mag, radiation from the other

side of the cloud may result in a shallower depth dependence than given by the above

single exponential form. In such cases, a bi-exponential form

may be more appropriate (van Dishoeck & Dalgarno

1984; van Dishoeck 1988). For

may be more appropriate (van Dishoeck & Dalgarno

1984; van Dishoeck 1988). For

mag,

α = 7.25 and β = 6.92 are found.

mag,

α = 7.25 and β = 6.92 are found.

The shielding of N2 by dust under various conditions is listed in Table 4. This shows that shielding by normal interstellar dust is larger than that by H2 and H for any AV and implies that the “smoke screen” by dust also plays a significant role in diffuse and translucent clouds and photon-dominated regions. However, in protoplanetary disks where the larger dust particles absorb and scatter less efficiently, the effects of H2 and H shielding become comparable, or even dominant, at large AV.

4. Chemical models

As an example of how to apply the new photodissociation rates, we ran chemical models for a set of diffuse and translucent clouds, a photon-dominated region (PDR), and a vertical cut through a circumstellar disk. The models use the UMIST06 chemical network (Woodall et al. 2007), stripped down to species containing only H, He, C, N and O. Species containing more than two C, N or O atoms are also removed since they are not relevant for our purposes. Freeze-out and thermal evaporation are added for all neutral species, but no grain-surface reactions are included other than H2 formation according to Black & van Dishoeck (1987). Self-shielding of CO is computed using the shielding functions of Visser et al. (2009); for N2, we use the self-shielding functions calculated here at 50 K. The elemental abundances relative to H are 0.0975 for He, 7.86 × 10-5 for C, 2.47 × 10-5 for N and 1.80 × 10-4 for O (Aikawa et al. 2008). Enhanced formation of CH+ (and thus also CO) at low AV is included following Visser et al. (2009) by supra-thermal chemistry, boosting the rate of ion-neutral reactions by setting the Alfvén speed to 3.3 km s-1 for column densities less than 4 × 1020 cm-2. Unless stated otherwise, the model of impinging UV flux is the Draine field of Eq. (3) modified by a scaling factor, χ. In all cases, the abundances of N, N2 and CO reach steady state after ~1 Myr, regardless of whether the gas starts in atomic or molecular form.

4.1. Diffuse and translucent clouds

A set of diffuse and translucent cloud models was run for central densities

nH = n(H) + 2n(H2) = 100,300

and 103 cm-3, at a temperature of 30 K, and assuming scaling factors

of the UV flux of χ = 0.5,1 and 5. Figure 10 shows the abundances of N, N2 and CO and

the photodissociation rates of N2 and CO as functions of depth into the cloud

(measured in AV) for the

nH = 103 and χ = 1 model. Both

CO and N2 are rapidly photodissociated in the limit of low extinction and

carbon and nitrogen are primarily in atomic form. Some CO is formed in a series of

(supra-thermal) ion-molecule reactions starting with C+ at the edge (Visser et al. 2009). Since the ionization potential of

atomic N lies just above that of H, preventing the formation of N+,

N2 can only form through slower neutral-neutral reactions. As a result, the

abundance of N2 is three orders of magnitude lower than that of CO at the edge

of the cloud. The conversion from N to N2 occurs at an

AV of 1.5 mag, at which point CO has become the main form of

carbon. The bottom panel of Fig. 10 illustrates that

self-shielding and mutual shielding by H and H2 significantly reduce the

photodissociation rate relative to dust alone. The column densities of N2 and

CO at AV = 1.5 mag are 1.5 × 1015 and

1.3 × 1016 cm-2. At high AV,

atomic N is maintained at an abundance of 3 × 10-6 by the dissociative

recombination of N2H+, which in turn is formed from the reaction

between N2 and cosmic-ray-produced H .

.

Two-dimensional shielding functions Θ[N(H), N(H2)] assuming an excitation temperature of 50 K.

To investigate the role of turbulence or non-thermal motions on the results, a model has been run in which the Doppler width of the N2 lines in the self-shielding calculation was increased to 3 km s-1 rather than the thermal width at low temperatures. The resulting N2 abundance as a function of depth is nearly identical to that presented in Fig. 10.

Absorption bands of N2 have possibly been detected in observations of the diffuse cloud toward HD 124314 (Knauth et al. 2004). The two relevant bands, indicated in Fig. 4, are particularly strongly absorbing, and are relatively unshielded by hydrogen. The depth of the observed absorption indicates a total N2 column density of (4.6 ± 0.8) × 1013 cm-2 and the stellar reddening of HD 124314 provides an estimate of the cloud’s extinction, AV = 1.5 mag. Figure 11 shows the cumulative N2 column density calculated for a range of radiation field intensities and nH densities as a function of AV. For comparison with the model, which considers only half of the cloud from edge to center and is irradiated from one side only, the observed AV and N2 column density must be halved. These models use the single exponential dust continuum shielding function; if the bi-exponential formulation were used, the model N2 column densities would be even lower for small AV. The maximum calculated column density occurs where the radiation field is weakest (χ = 0.5) and for the highest density (nH = 103 cm-3). These are extreme physical conditions for a cloud like HD 124314 and inconsistent with its relatively high H/H2 column density ratio (André et al. 2003) and low CO column density (Sheffer et al. 2008). An independent conformation of the N2 detection is warranted. Observed upper limits toward other diffuse clouds with lower AV are a few × 1012 cm-2 (Lutz et al. 1979), which are consistent with the current models for typical densities of a few hundred cm-3 and χ ≥1.

4.2. Photon-dominated region

The PDR model is run assuming an nH density of 105 cm-3, a temperature of 100 K, and a UV flux of χ = 103. Figure 12 shows the resulting abundances of N, N2, C, C+ and CO and the relevant photodissociation rates as functions of AV.

The calculated abundances of both N2 and CO at low AV are lower in the PDR model compared with the diffuse and translucent clouds, because of the stronger UV field. For all models, the abundance of N2 is several orders of magnitude lower than that of CO. Also, because of the increased radiation, the transition from N to N2 occurs deeper into the PDR: at an AV of about 3 mag. The column densities of N2 and CO at this point are 6 × 1015 and 3 × 1016 cm-2. The minor wiggle in the atomic N abundance profiles at AV = 2−3 mag is due to the abundance patterns of CH and OH. CH is the main destroyer of N at AV = 2 mag but its abundance drops going into the cloud because its main precursor, C+, disappears. The simultaneously increasing extinction allows for an increase in the OH abundance, so that this becomes the main destroyer of N for AV > 3 mag. Interestingly, the transition from N→N2 occurs at nearly the same depth into the cloud than that of C+ →C → CO.

Comparison of the shielding of 14N2 and 12CO by H2 + H and dust for a range of extinction, AV, at 10 K and taking N(H) = 5 × 1020 cm-2.

|

Fig. 8 Shielding of N2 by H2 + H as a function of H2 column density, N(H2), for three different values of N(H). An excitation temperature of 50 K is adopted for both N2 and H2. |

|

Fig. 9 Shielding of N2 by H2 + H as a function of H2 column density N(H2), for N2 and H2 excitation temperatures of 10, 50, 100 and 1000 K. The column-density of H is set to 1020 cm-2 in all cases. |

|

Fig. 10 Top: relative abundances of N, N2 and CO as a function of depth into a translucent cloud with χ = 1, T = 30 K and nH = 103 cm-3. Bottom: photodissociation rates of N2 (black) and CO (red) as functions of depth. Alternative photodissociation rate curves (, green) consider shielding by dust alone (dashed), dust + self-shielding (dotted), and dust + H + H2 (solid). The conversion from N to N2 occurs at AV ≃ 1.5 mag, as shown by the vertical dashed line. |

|

Fig. 11 Cumulative column density of N2 as a function of extinction, AV, at an excitation temperature of 30 K. Curves are shown for several different models: dotted, dashed, and solid lines indicate nH = 100, 300 and 1000 cm-3, respectively; blue, green and red lines scale the radiation field by χ = 0.5, 1 and 5, respectively. The asterisk indicates half the N2 column density and half the extinction observed by Knauth et al. (2004) in the diffuse cloud toward HD 124314. |

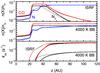

4.3. Circumstellar disk

The fourth model simulates a vertical slice through a circumstellar disk and its setup is identical to that of Visser et al. (2009). The slice is located at a radius of 105 AU in the standard model of D’Alessio et al. (1999), which supposes a disk of 0.07 M⊙ and 400 AU radius surrounding a T Tauri star of 0.5 M⊙ and 2 R⊙ radius. The surface of the slice, at a height of 120 AU, is illuminated by the Draine (1978) field with χ = 516. We ran the model assuming dust grain sizes of 0.1 and 1 μm. The results are plotted in Fig. 13.

Starting from the disk surface (high z) and moving inwards, the abundance profiles of N, N2 and CO show the same qualitative trends as they do for the translucent cloud and PDR models. The main difference arises from freeze-out of N2 and CO for z below 25 AU, at which point the dust temperature drops below ~20 K. The depletion of N2 also drives down the abundance of N2H+ which, in turn, restricts the abundance of atomic N. In the models presented here, nitrogen is fully converted into N2 at heights where no freeze-out occurs.

Increasing the grain size from 0.1 to 1 μm allows the UV field to penetrate to heights of about 35 instead of 45 AU. The abundances of N2 and CO are then a factor of 10–100 lower in the intervening zone, while that of atomic N is a factor of a few higher. Since atomic N is a prerequisite for an active nitrogen chemistry leading to species like HCN, this result illustrates that larger column densities of nitrogen-containing molecules can be expected in disks with grain growth.

The column densities integrated from surface to midplane are 2 × 1017 cm-2 for N2 and 1.2 × 1018 cm-2 for CO, regardless of the grain size, since the bulk of the N2 and CO are at high densities where UV photodissociation is negligible. The total column of N is 5 × 1016 cm-2 for 0.1 μm grains and 8 × 1016 cm-2 for 1 μm grains.

The models discussed above use a scaled Draine (1978) radiation field. A much cooler radiation field was also considered by assuming a 4000 K blackbody source scaled to the same flux between 912 and 2050 Å. Then, both carbon and nitrogen are fully molecular at the disk surface since photodissociation of both CO and N2 is negligible. A smaller amount of atomic N is maintained by chemical reactions for active nitrogen chemistry. This result is qualitatively consistent with the observation of Pascucci et al. (2009) that the color of the radiation field affects the nitrogen chemistry, although that study applied to the inner rather than the outer disk.

5. Conclusions

In this work, we compute accurate N2 photodissociation rates in the interstellar medium for the first time by employing new molecular data on its electronic transitions. The calculated N2 photodissociation rate in an unattenuated interstellar radiation field is 1.65 × 10-10 s-1 (50 K), ~28% lower than the previously recommended value. This rate increases somewhat with temperature due to J-dependent predissociation rates.

|

Fig. 12 Top: relative abundances of N (blue), N2 (black), C

(magenta), C+ (green) and CO (red) as functions of depth into a dense PDR.

Bottom: photodissociation rates of N2 and CO as

functions of depth into a dense PDR. The vertical dashed line indicates where

He+ and H |

|

Fig. 13 Top and middle: relative abundances of N (blue), N2 (black) and CO (red) as a function of height in a slice through a circumstellar disk exposed to the interstellar radiation field (ISRF) scaled by a factor χ = 516 and a 4000 K black body field. Bottom: the relevant photodissociation rates of CO and N2. Solid lines are for a grain size of 0.1 μm, dotted lines for 1 μm. |

The simulated spectra reveal that the most important range for photodissociation is 957–980 Å, where H2 and H absorption significantly overlap with N2 absorption. In contrast, CO only weakly shields N2. Self-shielding and mutual shielding functions have been computed for a range of N2, H2 and H column densities. For interstellar grains, shielding by dust is also effective. In protoplanetary disks, where dust particles have grown to μm size, the dust shielding becomes less than that of H2.

The new rates have been incorporated into models of diffuse and translucent clouds, of a dense PDR, and a protoplanetary disk. The translucent cloud models show that the observed column of interstellar N2 in a translucent cloud with AV = 1.5 mag can only be reproduced if the density nH is higher than 1000 cm-3 and the radiation field has an intensity of less than half of the Draine (1978) field. For dense PDRs, the N2 abundance only becomes significant at extinctions of more than 3 mag into the cloud but the transition of N → N2 occurs at nearly the same depth as that of C+ → C → CO. Disk models show that nitrogen is fully converted into N2 at heights before freeze-out occurs, irrespective of grain size. However, an active nitrogen chemistry can take place in the upper layers of a disk where not all nitrogen is locked up in N2, except for very cool radiation fields. Altogether, data are now available to accurately model N2 photodissociation in a wide variety of interstellar and circumstellar media.

Online material

Appendix A: self-shielding functions

In this section, we provide a table containing the self-shielding functions of N2 at 10, 100 and 1000 K (data for Fig. 6).

N2 self-shielding as a function of column density, N(N2), for excitation temperatures of 10, 100 and 1000 K.

Appendix B: High resolution spectra

In this section, we provide the high resolution spectra of N2 at 50 K (zoom in for Fig. 4). The H2 and H column densities are the same as those used in Fig. 4.

|

Fig. B.1 Zoom-in of the high-resolution spectra of N2 (black line) and H plus H2 (red line) in the wavelength range of 911.75–930 Å for a thermal excitation temperature of 50 K. The column density of N2 is 1015 cm-2 and values for H2 and H are taken to be half of the observed column densities in the well-studied diffuse cloud toward ζ Oph, as is appropriate for the center of the cloud: N(H2) = 2.1 × 1020 and N(H) = 2.6 × 1020 cm-2. The model H2 Doppler width is 3 km s-1. Also shown is the H2 + H absorption spectrum (blue) toward ζ Oph using the observed column densities for individual J levels, showing non-thermal excitation of H2. |

Available on-line at http://hdl.handle.net/1885/7360

Acknowledgments

Astrochemistry in Leiden is supported by the Netherlands Research School for Astronomy (NOVA), by a Spinoza grant and grant 648.000.002 from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), and by the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme FP7/2007-2013 under grant agreements 291141 (CHEMPLAN) and 238258 (LASSIE). Calculations of the N2 photodissociation cross sections were supported by the Australian Research Council Discovery Program, through Grant Nos. DP0558962 and DP0773050.

References

- Abgrall, H., Roueff, E., Launay, F., Roncin, J. Y., & Subtil, J. L. 1993a, A&AS, 101, 273 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Abgrall, H., Roueff, E., Launay, F., Roncin, J. Y., & Subtil, J. L. 1993b, A&AS, 101, 323 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Aikawa, Y., Wakelam, V., Garrod, R. T., & Herbst, E. 2008, ApJ, 674, 984 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ajello, J. M., James, G. K., Franklin, B. O., & Shemansky, D. E. 1989, Phys. Rev. A, 40, 3524 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- André, M. K., Oliveira, C. M., Howk, J. C., et al. 2003, ApJ, 591, 1000 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bergin, E. A., Alves, J., Huard, T., & Lada, C. J. 2002, ApJ, 570, L101 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bettens, R. P. A., Lee, H.-H., & Herbst, E. 1995, ApJ, 443, 664 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Black, J. H., & van Dishoeck, E. F. 1987, ApJ, 322, 412 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Crapsi, A., Caselli, P., Walmsley, C. M., et al. 2005, ApJ, 619, 379 [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessio, P., Calvet, N., Hartmann, L., Lizano, S., & Cantó, J. 1999, ApJ, 527, 893 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Daranlot, J., Hincelin, U., Bergeat, A., et al. 2012, Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci., 109, 10233 [Google Scholar]

- Draine, B. T. 1978, ApJS, 36, 595 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dutrey, A., Henning, T., Guilloteau, S., et al. 2007, A&A, 464, 615 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Fontani, F., Palau, A., Caselli, P., et al. 2011, A&A, 529, L7 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Gondhalekar, P. M., Phillips, A. P., & Wilson, R. 1980, A&A, 85, 272 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Habing, H. J. 1968, Bull. Astron. Inst. Netherlands, 19, 421 [Google Scholar]

- Haverd, V. E., Lewis, B. R., Gibson, S. T., & Stark, G. 2005, J. Chem. Phys., 123, 4304 [Google Scholar]

- Heays, A. N. 2011, Ph.D. Thesis, The Australian National University [Google Scholar]

- Heays, A. N., Lewis, B. R., Stark, G., et al. 2009, J. Chem. Phys., 131, 194308 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heays, A. N., Dickenson, G. D., Salumbides, E. J., et al. 2011, J. Chem. Phys., 135, 244301 [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helm, H., Hazell, I., & Bjerre, N. 1993, Phys. Rev. A, 48, 2762 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst, E., & Klemperer, W. 1973, ApJ, 185, 505 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Herbst, E., Green, S., Thaddeus, P., & Klemperer, W. 1977, ApJ, 215, 503 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Huber, K. P., & Herzberg, G. 1979, Molecular spectra and molecular structure IV: Constants of diatomic molecules (New York: Van Nostrand) [Google Scholar]

- Knauth, D. C., Andersson, B.-G., McCandliss, S. R., & Warren Moos, H. 2004, Nature, 429, 636 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Langer, W. D., & Graedel, T. E. 1989, ApJS, 69, 241 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Le Petit, F., Nehmé, C., Le Bourlot, J., & Roueff, E. 2006, ApJS, 164, 506 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.-H., Herbst, E., Pineau des Forets, G., Roueff, E., & Le Bourlot, J. 1996, A&A, 311, 690 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre-Brion, H., & Field, R. W. 2004, The spectra and dynamics of diatomic molecules (Elsevier) [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, B. R., Gibson, S. T., Sprengers, J. P., et al. 2005a, J. Chem. Phys., 123, 236101 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, B. R., Gibson, S. T., Zhang, W., Lefebvre-Brion, H., & Robbe, J.-M. 2005b, J. Chem. Phys., 122, 144302 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, B. R., Baldwin, K. G. H., Heays, A. N., et al. 2008a, J. Chem. Phys., 129, 204303 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, B. R., Baldwin, K. G. H., Sprengers, J. P., et al. 2008b, J. Chem. Phys., 129, 164305 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, B. R., Heays, A. N., Gibson, S. T., Lefebvre-Brion, H., & Lefebvre, R. 2008c, J. Chem. Phys., 129, 164306 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang, M.-C., Heays, A. N., Lewis, B. R., Gibson, S. T., & Yung, Y. L. 2007, ApJ, 664, L115 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X., Shemansky, D. E., Malone, C. P., et al. 2008, J. Geophys. Res., 113, A02304 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lutz, B. L., Snow, Jr., T. P., & Owen, T. 1979, ApJ, 227, 159 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, J. R. 2009, Meteor. Planet. Sci. Suppl., 72, 5437 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, J. R. 2010, Meteor. Planet. Sci. Suppl., 73, 5424 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Maret, S., Bergin, E. A., & Lada, C. J. 2006, Nature, 442, 425 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathis, J. S., Mezger, P. G., & Panagia, N. 1983, A&A, 128, 212 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Mauersberger, R., & Henkel, C. 1991, A&A, 245, 457 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Meier, D. S., & Turner, J. L. 2005, ApJ, 618, 259 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Meier, R. R., Samson, J. A. R., Chung, Y., Lee, E.-M., & He, Z.-X. 1991, Planet. Space Sci., 39, 1197 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Muller, S., Beelen, A., Guélin, M., et al. 2011, A&A, 535, A103 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Ndome, H., Hochlaf, M., Lewis, B. R., et al. 2008, J. Chem. Phys., 129, 164307 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Öberg, K. I., Qi, C., Fogel, J. K. J., et al. 2010, ApJ, 720, 480 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pascucci, I., Apai, D., Luhman, K., et al. 2009, ApJ, 696, 143 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Roberge, W. G., Dalgarno, A., & Flannery, B. P. 1981, ApJ, 243, 817 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Roberge, W. G., Jones, D., Lepp, S., & Dalgarno, A. 1991, ApJS, 77, 287 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Savage, B. D., Bohlin, R. C., Drake, J. F., & Budich, W. 1977, ApJ, 216, 291 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sheffer, Y., Rogers, M., Federman, S. R., et al. 2008, ApJ, 687, 1075 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Spelsberg, D., & Meyer, W. 2001, J. Chem. Phys., 115, 6438 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sprengers, J. P., Ubachs, W., Baldwin, K. G. H., Lewis, B. R., & Tchang-Brillet, W.-Ü. L. 2003, J. Chem. Phys., 119, 3160 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sprengers, J. P., Ubachs, W., Johansson, A., et al. 2004, J. Chem. Phys., 120, 8973 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprengers, J. P., Reinhold, E., Ubachs, W., Baldwin, K. G. H., & Lewis, B. R. 2005, J. Chem. Phys., 123, 144315 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stark, G., Lewis, B. R., Heays, A. N., et al. 2008, J. Chem. Phys., 128, 114302 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobel, D. F. 1982, Origins of Life, 12, 244 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin, J. J., Hartmann, L., Bergin, E., et al. 2012, ApJ, 748, 16 [Google Scholar]

- Turner, B. E. 1974, Ap&SS, 29, 247 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- van Dishoeck, E. F. 1988, in Rate Coefficients in Astrochemistry, eds. T. J. Millar, & D. A. Williams (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers), 49 [Google Scholar]

- van Dishoeck, E. F., & Black, J. H. 1988, ApJ, 334, 771 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- van Dishoeck, E. F., & Dalgarno, A. 1984, ApJ, 277, 576 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- van Dishoeck, E. F., van Hemert, M. C., Allison, A. C., & Dalgarno, A. 1984, ApJ, 81, 5709 [Google Scholar]

- van Dishoeck, E. F., Jonkheid, B., & van Hemert, M. C. 2006, Faraday Discussions, 303, 231 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viala, Y. P., Letzelter, C., Eidelsberg, M., & Rostas, F. 1988, A&A, 193, 265 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Visser, R., van Dishoeck, E. F., & Black, J. H. 2009, A&A, 503, 323 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Walter, C. W., Cosby, P., & Helm, H. 1993, J. Chem. Phys., 99, 3553 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wayne, R. P. 2000, Chemistry of Atmospheres (Oxford University Press) [Google Scholar]

- Woodall, J., Agúndez, M., Markwick-Kemper, A. J., & Millar, T. J. 2007, A&A, 466, 1197 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C. Y. R., Judge, D. L., Tsai, M.-H., et al. 2012, J. Chem. Phys., 136, 044301 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

All Tables

Unattenuated photodissociation rates of N2 (excitation temperature 50 K) in a blackbody radiation field at various temperatures, TBB.

Contributions of different bands to N2 photodissociation at 50 K at the edge (unattenuated photodissociation) and in the center of the ζ Oph diffuse cloud.

Two-dimensional shielding functions Θ[N(H), N(H2)] assuming an excitation temperature of 50 K.

Comparison of the shielding of 14N2 and 12CO by H2 + H and dust for a range of extinction, AV, at 10 K and taking N(H) = 5 × 1020 cm-2.

N2 self-shielding as a function of column density, N(N2), for excitation temperatures of 10, 100 and 1000 K.

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Diabatic-basis potential-energy curves for electronic states of N2

relevant to interstellar photodissociation. Blue curves:

|

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Top: branching to various decay channels of the c′(v′ = 0) excited-state of N2 as a function of total rotational quantum number, J. The figure includes spontaneous emission to several non-dissociative ground state vibrational levels (v′′ = 0,1 and 2) and decay due to predissociation (dis.). Bottom: fractional population of the N2 ground state in its lowest vibrational level as a function of J and for several excitation temperatures. The 2:1 ratio of populations for even:odd J levels arises from the combined rotational and nuclear spin statistics. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 CSE-calculated absorption cross section (blue) of the c′(v′ = 0) level of N2 assuming an excitation temperature of 300 K. Also shown is a dissociation cross section (red) which has been corrected for the non-unity dissociation efficiency, ηJ, of this band (see Fig. 2). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4 Simulated absorption spectra for N2 (black) and H2 + H (red) in the wavelength range 912–1000 Å assuming thermal excitation temperatures of 50 (top) and 1000 K (bottom). The column density of N2 is 1015 cm-2 and values for H2 and H are taken to be half of the observed column densities in the well-studied diffuse cloud toward ζ Oph, as is appropriate for the center of the cloud: N(H2) = 2.1 × 1020 and N(H) = 2.6 × 1020 cm-2. The model H2 Doppler width is 3 km s-1. Also shown is the H2 + H absorption spectrum (blue) toward ζ Oph using the observed column densities for individual J levels, showing enhanced non-thermal excitation of H2 in the higher J levels. The asterisks indicate the c′(0) (Band 20) and c(0) (Band 21) bands, respectively, detected in absorption toward HD 124314. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5 Unattenuated photodissociation rates of N2 immersed in a Draine (1978) field at various excitation temperatures. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 6 N2 self-shielding as a function of column density, N(N2), for excitation temperatures of 10, 50, 100 and 1000 K. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 7 Top: comparison of N2 (black) and CO (blue) model absorption spectra between 912 and 1000 Å assuming an excitation temperature of 50 K for both molecules. The N2 and CO column densities are both 1015 cm-2. Bottom: blow-up of the above spectra for the wavelength region 956–980 Å. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 8 Shielding of N2 by H2 + H as a function of H2 column density, N(H2), for three different values of N(H). An excitation temperature of 50 K is adopted for both N2 and H2. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 9 Shielding of N2 by H2 + H as a function of H2 column density N(H2), for N2 and H2 excitation temperatures of 10, 50, 100 and 1000 K. The column-density of H is set to 1020 cm-2 in all cases. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 10 Top: relative abundances of N, N2 and CO as a function of depth into a translucent cloud with χ = 1, T = 30 K and nH = 103 cm-3. Bottom: photodissociation rates of N2 (black) and CO (red) as functions of depth. Alternative photodissociation rate curves (, green) consider shielding by dust alone (dashed), dust + self-shielding (dotted), and dust + H + H2 (solid). The conversion from N to N2 occurs at AV ≃ 1.5 mag, as shown by the vertical dashed line. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 11 Cumulative column density of N2 as a function of extinction, AV, at an excitation temperature of 30 K. Curves are shown for several different models: dotted, dashed, and solid lines indicate nH = 100, 300 and 1000 cm-3, respectively; blue, green and red lines scale the radiation field by χ = 0.5, 1 and 5, respectively. The asterisk indicates half the N2 column density and half the extinction observed by Knauth et al. (2004) in the diffuse cloud toward HD 124314. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 12 Top: relative abundances of N (blue), N2 (black), C

(magenta), C+ (green) and CO (red) as functions of depth into a dense PDR.

Bottom: photodissociation rates of N2 and CO as

functions of depth into a dense PDR. The vertical dashed line indicates where

He+ and H |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 13 Top and middle: relative abundances of N (blue), N2 (black) and CO (red) as a function of height in a slice through a circumstellar disk exposed to the interstellar radiation field (ISRF) scaled by a factor χ = 516 and a 4000 K black body field. Bottom: the relevant photodissociation rates of CO and N2. Solid lines are for a grain size of 0.1 μm, dotted lines for 1 μm. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. B.1 Zoom-in of the high-resolution spectra of N2 (black line) and H plus H2 (red line) in the wavelength range of 911.75–930 Å for a thermal excitation temperature of 50 K. The column density of N2 is 1015 cm-2 and values for H2 and H are taken to be half of the observed column densities in the well-studied diffuse cloud toward ζ Oph, as is appropriate for the center of the cloud: N(H2) = 2.1 × 1020 and N(H) = 2.6 × 1020 cm-2. The model H2 Doppler width is 3 km s-1. Also shown is the H2 + H absorption spectrum (blue) toward ζ Oph using the observed column densities for individual J levels, showing non-thermal excitation of H2. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. B.2 As Fig. B.1, but for 930–950 Å. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. B.3 As Fig. B.1, but for 950–970 Å. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. B.4 As Fig. B.1, but for 970–990 Å. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. B.5 As Fig. B.1, but for 990–1000 Å. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.