| Issue |

A&A

Volume 554, June 2013

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A97 | |

| Number of page(s) | 15 | |

| Section | Cosmology (including clusters of galaxies) | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201321561 | |

| Published online | 11 June 2013 | |

Tully-Fisher analysis of the multiple cluster system Abell 901/902⋆

1 Institute for Astro- and Particle Physics, University of Innsbruck, Technikerstr. 25/8, 6020 Innsbruck, Austria

e-mail: benjamin.boesch@uibk.ac.at

2 Department of Physics, Denys Wilkinson Building, University of Oxford, Keble Road, Oxford OX1 3RH, UK

3 Research School of Astronomy and Astrophysics, Australian National University, Cotter Road, Weston Creek, ACT 2611, Australia

4 School of Physics and Astronomy, The University of Nottingham, University Park, Nottingham NG7 2RD, UK

5 Department of Astronomy, University of Vienna, Türkenschanzstr. 17, 1180 Wien, Austria

6 Department of Physics, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON N2L 3G1, Canada

7 Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, Königstuhl 17, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany

Received: 22 March 2013

Accepted: 19 April 2013

Context.

Aims. We derive rotation curves from optical emission lines of 182 disc galaxies (96 in the cluster and 86 in the field) in the region of Abell 901/902 located at z ~ 0.165. We continue the kinematic analysis presented in a previous paper. Here, we focus on the analysis of B-band and stellar-mass Tully-Fisher relations. We examine possible environmental dependencies and differences between normal spirals and dusty red galaxies, i.e. disc galaxies that have red colours because of relatively low star formation rates.

Methods. Assuming a tilted ring model we simulate the spectroscopy of a given galaxy and reconstruct the maximum rotation velocity from the best-fitting simulated rotation curve. We fit regression lines adopting a maximum-likelihood method based on Bayes’ theorem to build B-band and stellar-mass Tully-Fisher relations.

Results. We find no significant differences between the best-fit Tully-Fisher slope of cluster and field galaxies. At fixed slope, the field population with high-quality rotation curves (57 objects) is brighter by ΔMB = −0.m42 ± 0.m15 than the cluster population (55 objects). We show that this slight difference is at least in part an environmental effect. The scatter of the cluster Tully-Fisher relation increases for galaxies closer to the core region, also indicating an environmental effect. Interestingly, dusty red galaxies become fainter towards the core at a given rotation velocity (i.e. total mass). This indicates that the star formation in these galaxies is in the process of being quenched. The luminosities of normal spiral galaxies are slightly higher at fixed rotation velocity for smaller cluster-centric radii. These galaxies are probably gas-rich (compared to the dusty red population) and the onset of ram-pressure stripping increases their star-formation rates. Galaxies with smooth morphology show higher root mean square values in the fitting of their rotation curves. This is particularly the case for dusty red galaxies. A cluster-specific interaction process like ram-pressure stripping is the best explanation, since it only affects the gaseous disc but not the stellar morphology.

Conclusions. The results from the Tully-Fisher analysis are consistent with and complement our previous findings. Dusty red galaxies might be an intermediate stage in the transformation of infalling field spiral galaxies into cluster lenticulars (also known as S0s), and this might explain the well-known increase of the S0 fraction in galaxy clusters with cosmic time.

Key words: galaxies: kinematics and dynamics / galaxies: evolution / galaxies: spiral / galaxies: clusters: individual: Abell 901 / galaxies: clusters: general / galaxies: clusters: individual: Abell 902

© ESO, 2013

1. Introduction

The empirically found, tight correlation between the rotation velocity Vrot of disc galaxies and their luminosity L ( ) was originally introduced by Tully & Fisher (1977) as a new method of determining distances to galaxies. Since the maximum rotation velocity is proportional to the total mass of a galaxy and the luminosity correlates with stellar mass, the Tully-Fisher relation (TFR) provides a link between the dark and visible matter components of a galaxy. This link is assumed to be a consequence of the formation scenario of disc galaxies within the framework of a cold dark matter universe (Blumenthal et al. 1986). Initially in equilibrium with the dark matter halo, rotating discs form from collapsing gas clouds. Angular momentum is conserved in the process. In contrast to dissipationless dark matter, baryonic particles can lose part of their energy via radiation and hence are able to form more compact structures (e.g. Dutton et al. 2007).

) was originally introduced by Tully & Fisher (1977) as a new method of determining distances to galaxies. Since the maximum rotation velocity is proportional to the total mass of a galaxy and the luminosity correlates with stellar mass, the Tully-Fisher relation (TFR) provides a link between the dark and visible matter components of a galaxy. This link is assumed to be a consequence of the formation scenario of disc galaxies within the framework of a cold dark matter universe (Blumenthal et al. 1986). Initially in equilibrium with the dark matter halo, rotating discs form from collapsing gas clouds. Angular momentum is conserved in the process. In contrast to dissipationless dark matter, baryonic particles can lose part of their energy via radiation and hence are able to form more compact structures (e.g. Dutton et al. 2007).

Analysing the TFR in different luminosity bands (e.g. Kannappan et al. 2002; Pizagno et al. 2007; Verheijen 2001) or plotting the rotation velocity directly against the stellar mass (smTFR; e.g. Kassin et al. 2007; Miller et al. 2011; Pizagno et al. 2005) or baryonic mass (bTFR; e.g. McGaugh et al. 2000; Puech et al. 2010; Verheijen 2001) can give valuable insight into the formation history of spiral galaxies. Comparing the best-fit parameters of the TFR (slope, intercept, and scatter) at different redshifts to predictions of numerical simulations helps to constrain the physical processes important for the evolution of spiral galaxies (e.g. Bamford et al. 2005, 2006; Böhm & Ziegler 2007; Böhm et al. 2004; Kassin et al. 2007; Miller et al. 2011, 2012; Puech et al. 2008; Vogt et al. 1996).

The well-known morphology-density relation (Dressler 1980) has been confirmed in many subsequent studies highlighting a picture of high-density environments altering the properties of galaxies. Besides a prevalence of more early-type morphology, galaxies residing in clusters have on average redder colours (e.g. Blanton et al. 2005), lower star-formation rates (e.g. Lewis et al. 2002; Verdugo et al. 2008), and a reduced gas content (e.g. Giovanelli & Haynes 1985; Solanes et al. 2001) compared to field galaxies. Consequently, the TF parameters might vary between different environments and hence are the topic of several studies (e.g. Bamford et al. 2005; Jäger et al. 2004; Kutdemir et al. 2008, 2010; Milvang-Jensen et al. 2003; Moran et al. 2007; Nakamura et al. 2006; Ziegler et al. 2003).

Some of them show conflicting results and conclusions. The main reason for this are differences in the data analysis including the observation of the target galaxies, the derivation of luminosities and rotation velocities, or the methods used to fit the TFR. Several definitions of rotation velocities exist and many groups use slightly different methods to account for observational effects and to infer the intrinsic rotation curve (RC) of a galaxy. Different sample sizes, selection criteria, and galaxy populations make a comparison of results even more complicated.

Several general trends could be established, though. The slope of the TFR increases towards redder photometric passbands (e.g. Kannappan et al. 2002; Pizagno et al. 2007; Verheijen 2001). Redder bands are less sensitive to recent star-formation events and dust extinction and better trace the underlying old stellar population, which dominates the stellar mass. On the one hand, the B-band TFR shows a brightening of the intercept up to ΔMB ~ 1 mag out to a redshift of z ~ 1 (e.g. Böhm et al. 2004; Fernández Lorenzo et al. 2010; Miller et al. 2011; Vogt et al. 1996; Weiner et al. 2006; Ziegler et al. 2002). This is most likely due to an enhancement of the star-formation rate and a younger stellar population (Hopkins 2004). On the other hand, there is little or no evolution in the stellar-mass or baryonic TFR (e.g. Flores et al. 2006; Miller et al. 2011; Puech et al. 2008). In agreement with simulations (e.g. Steinmetz & Navarro 1999), most studies measure a larger scatter for TFRs at higher redshifts (e.g. Bamford et al. 2006; Böhm & Ziegler 2007; Kassin et al. 2007).

Comparisons between the TFRs of cluster and field galaxies show no clear results. While Jaffé et al. (2011), Nakamura et al. (2006), and Ziegler et al. (2003) find no significant differences between these two environments, Bamford et al. (2005) and Milvang-Jensen et al. (2003) deduce higher B-band luminosities in clusters compared to the field. Moran et al. (2007) find a larger scatter for cluster galaxies. Again, sample selection and analysis techniques might influence the results, but the choice of a particular cluster and its ICM properties and dynamical state might also play a role.

Using spatially resolved spectra obtained with the VIsible MultiObject Spectrograph (VIMOS) on the Very Large Telescope (VLT) in combination with already existing data from the Space Telescope A901/902 Galaxy Evolution Survey (STAGES) project (Gray et al. 2009a), we continue the kinematic analysis of Bösch et al. (2013, hereafter Paper I). We exploit RCs of disc galaxies in and around the multiple cluster system Abell 901/902 with a focus on the analysis of the TFR. The paper is organised as follows. Section 2 gives a short introduction into the STAGES project, outlines the sample selection and observations, and reviews the results of Paper I. Section 3 describes the derivation of the parameters needed for the TF analysis and presents adopted methods to build the TFR. Section 4 contains the TF analysis, which provides the basis for the residual analysis of Sect. 5. Finally, Sect. 6 summarises the main points.

Throughout this paper, we assume a cosmology with Ωm = 0.3, ΩΛ = 0.7, and H0 = 70 km s-1 Mpc-1. Magnitudes quoted in this paper are in the AB system.

2. Data

2.1. The STAGES data set

STAGES is a multi-wavelength survey centred on the area around the multiple cluster system Abell 901/902. It comprises four subclusters: A901a (at redshift 0.164), A901b (z = 0.163), A902 (z = 0.167), and the SW group (z = 0.169). They are in a non-virialised state (Bösch et al. 2013) and will most likely coalesce to one big system in the future. The (~5 × 5 Mpc2) region of Abell 901/902 has been the subject of Hubble Space Telescope/Advanced Camera for Surveys (HST/ACS) observations producing an 80-tile mosaic of V-band (F606W) images. We have available 17-band COMBO-17 (Classifying Objects by Medium-Band Observations) ground-based imaging (Wolf et al. 2003), Spitzer 24 μm, and XMM-Newton X-ray data (Gilmour et al. 2007). Gravitational lensing maps (Heymans et al. 2008), spectral energy distributions (SEDs; Wolf et al. 2003), stellar masses (Borch et al. 2006), star-formation rates (Bell et al. 2007), mean stellar ages and morphological classifications provide an excellent starting point for further analysis. Gray et al. (2009a) give an overview of the STAGES project and present the publicly available master catalogue (Gray et al. 2009b).

2.2. Observation, sample selection, and data reduction

Information on the spectroscopic observations of A901/902 with VLT/VIMOS and details on the data reduction process are presented in Paper I, so we will only give a short review of the most important steps here.

Multi-object spectroscopy (MOS) with VIMOS was carried out between February 8 and March 10, 2010 (ESO-ID 384.A-0813, P.I. A. Böhm). Four VIMOS pointings (~1′ overlap) sample the whole A901/902 field (two exposures of 1800 s each). We opted for the high-resolution grism HR-blue with a slit width of  , which covered a ~2050 Å spectral range in the wavelength interval [3700 Å,6740 Å]. This configuration yielded a spectral resolution of R ~ 2000 and an average dispersion of 0.51 Å /pixel at an image scale of

, which covered a ~2050 Å spectral range in the wavelength interval [3700 Å,6740 Å]. This configuration yielded a spectral resolution of R ~ 2000 and an average dispersion of 0.51 Å /pixel at an image scale of  pixel. The robustness of our analysis against varying seeing conditions during spectroscopy is discussed in Sect. 3.3.

pixel. The robustness of our analysis against varying seeing conditions during spectroscopy is discussed in Sect. 3.3.

Our primary targets for spectroscopy are disc galaxies showing emission lines. Hence, we selected galaxies with stellar masses M∗ > 109 M⊙, absolute magnitudes MB < − 18, a star-forming SED (selection criterion in the public catalogue Gray et al. 2009b: sed_type ≥ 2), and a visually confirmed disc component on the ACS images with an inclination angle i > 30°. We require photometric redshifts in the interval 0.1 < zphot < 0.26 resulting in a matched cluster and field sample. This selection resulted in ~320 cluster and ~160 field candidates. Using the ESO VIMOS mask preparation software (VMMPS), we manually placed MOS slits along the apparent major axis of the galaxies (allowing slit tilt angles up to ± 45°). In the end, we obtained spectra of 215 different galaxies.

One aim of our project is to investigate the population of dusty red galaxies (Wolf et al. 2005). In total, 44 of the 215 spectra belong to galaxies with this SED type (selection criterion in the public catalogue Gray et al. 2009b: sed_type = 2). Dusty red galaxies are spread across the red sequence in the U − V colour−magnitude diagram, but unlike early-type red galaxies, part of their colour is due to intrinsic dust extinction (E(B − V) ≥ 0.1). Hence, they could be interpreted as the low specific-star-formation rate tail of the blue cloud (Wolf et al. 2005).

We performed the spectroscopic data reduction mainly using the ESO-VIMOS pipeline (version 2.2.3). The main reduction steps were bias subtraction, correction of distortions resulting from the focal reducer using flat field exposures (a potential normalisation was skipped because of reflections present in the flat-field images) and wavelength calibration. Additionally, we performed bad pixel and cosmic ray cleaning. Wavelength calibration for spectra with slits in the upper third of the CCD or with large tilt angles was improved by adding Argon lines to the catalogue of arc lamp lines. For more details see Paper I.

2.3. Results from Paper I

In this section we will review results from Bösch et al. (2013), which will be important for the current analysis and will help to interpret our data.

We were able to measure spectroscopic redshifts for 200 different galaxies, either from emission lines (188) or from strong absorption lines (12). Using galaxies observed more than once and following a prescription outlined in Milvang-Jensen et al. (2008), we estimated the typical redshift error to be δz/(1 + z) ~ 0.00016 or 47 km s-1 in rest-frame.

|

Fig. 1 Redshift histogram of the 200 galaxies of our sample. The cluster sample (106 objects; blue backslash hatching) peaks at the cluster redshift z ~ 0.165. The field sample (94 objects; green slash hatching) shows a bump at z ~ 0.26, which might be a volume effect. |

We used the biweight estimator of scale and location (Beers et al. 1990) to estimate the velocity dispersion and mean redshift of each of the four subclusters individually. On the basis of these properties, we determined cluster membership using a 3σ-clipping. We identified 106 cluster members. Figure 1 shows the redshift histogram of the whole sample, separated into cluster and field galaxies.

We found that the fraction of cluster galaxies with distorted RCs is 75% higher than for field galaxies. Most of these differences can be attributed to morphologically undistorted galaxies with a relatively smooth stellar disc. Dusty red galaxies account for a large part of this population. This suggests a cluster-specific mechanism, which mainly affects the gas disc of the cluster spirals, with ram-pressure stripping as the best candidate. Investigations of the gas concentration implied that most spiral galaxies traverse the cluster for the first time. Especially for dusty red galaxies, ram-pressure could be a dominant mechanism in A901/902, even in the cluster outskirts.

3. Methods

Most galaxy properties such as stellar masses, apparent magnitudes, and inclination angles are already provided by the STAGES project (Gray et al. 2009b). Assuming a Kroupa et al. (1993) stellar initial mass function, Borch et al. (2006) derived stellar masses from an SED-fitting of templates from PEGASE (Fioc & Rocca-Volmerange 1997) population synthesis models to the COMBO-17 fluxes. They noted that alternatively using Kroupa (2001) or Chabrier (2003) initial mass functions would result in the same stellar masses to within ~10%.

We only need to determine rest-frame absolute magnitudes and maximum rotation velocities for each object, and then derive the TFRs for several samples. We adopted V2.2, the velocity at 2.2 disc scalelengths rd, as our kinematic measure, because it produces the tightest TFRs and is more robust against observational errors than other velocity definitions (Courteau 1997). In contrast, the asymptotic velocity Vmax, for example, is easily overestimated in galaxies with insufficiently extended RCs. We note that the chosen point at 2.2rd is the radius where the rotation velocity of an idealised self-gravitating disc is expected to peak (Freeman 1970).

3.1. Rest-frame magnitudes

Apparent V-band magnitudes Mag_best from the HST/ACS (F606W) images were measured using SExtractor (Bertin & Arnouts 1996). To compute absolute magnitudes in the B-band, we apply a k-correction kB(V,T,z), the distance modulus D(z,H0,Ωm,ΩΛ), and a correction for Galactic absorption  and intrinsic extinction

and intrinsic extinction  .

.

The k-correction is needed to transform the apparent magnitude in an observed band to a rest-frame band for a given galaxy. This correction depends on the SED type T and the redshift z. In our case it is sufficient to use the transformation V → B, since at the redshifts of our sample the V-band matches the rest-frame B-band. We determine the correct SED T-type individually by comparing our galaxy spectra to the templates in the Kennicutt catalogue (Kennicutt 1992a,b). Besides the stellar continuum shape of the spectra, we use equivalent widths, the relative strength of emission lines, and the prominence of absorption lines for classification. The SED type T ranges from 1 (for a typical spectrum of an Sa galaxy) to 10 (for type Im). For more details see Böhm et al. (2004).

We adopt the correction factors for Galactic extinction in the direction of A901/902 (α = 9 h 56 min 17 s, δ = − 10°01′11′′, J2000) of the observed V-band from the NASA extragalactic database following Schlafly & Finkbeiner (2011). This yields the following value for the whole sample:  .

.

A critical step is the correction for intrinsic absorption  due to dust extinction. The intrinsic absorption depends on the inclination angle i or, equivalently, the axis ratio a/b of a galaxy and is maximum for an edge-on and minimum for a face-on configuration. We follow the prescription of Tully et al. (1998) and apply a correction, which is also correlated with the maximum rotation velocity Vmax of a galaxy, since extinction is stronger in more massive galaxies (Giovanelli et al. 1995). This correction is relative to a face-on orientation and does not account for a potential residual absorption in a face-on system. All in all, we apply the intrinsic absorption correction

due to dust extinction. The intrinsic absorption depends on the inclination angle i or, equivalently, the axis ratio a/b of a galaxy and is maximum for an edge-on and minimum for a face-on configuration. We follow the prescription of Tully et al. (1998) and apply a correction, which is also correlated with the maximum rotation velocity Vmax of a galaxy, since extinction is stronger in more massive galaxies (Giovanelli et al. 1995). This correction is relative to a face-on orientation and does not account for a potential residual absorption in a face-on system. All in all, we apply the intrinsic absorption correction ![\begin{equation} \begin{aligned} A^{i}_{B}(a/b,V_{\mathrm{max}})&= \log(a/b)\left[-4.48+2.75\log(V_{\mathrm{max}})\right].\\ \end{aligned} \label{eq:ia} \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/06/aa21561-13/aa21561-13-eq62.png) (1)To summarise, the absolute magnitude in a galaxy’s rest-frame B-band is calculated using the equation

(1)To summarise, the absolute magnitude in a galaxy’s rest-frame B-band is calculated using the equation  (2)We compute the corresponding errors of the absolute magnitudes via error propagation. We assume an uncertainty of 10% for the axis ratio and an SED classification error of δT = 2. The latter transforms into an average uncertainty in the k-correction of

(2)We compute the corresponding errors of the absolute magnitudes via error propagation. We assume an uncertainty of 10% for the axis ratio and an SED classification error of δT = 2. The latter transforms into an average uncertainty in the k-correction of  .

.

3.2. Rotation-curve extraction

We address the extraction of the RCs from the emission lines of a spectrum only very briefly here, since this process is already described in detail in Paper I. Depending on a galaxy’s redshift and position on the CCD, up to four emission lines are visible in the VIMOS spectra: [OIII] λ5007 Å, [OIII] λ4959 Å, Hβ λ4861 Å, and [OII] λ3726/3729. Prior to the emission line fitting we add up three (or five, in cases with a very low signal-to-noise ratio S/N) neighbouring rows for each spatial position of the spectrum to enhance the S/N. We then transform red- and blueshifts of the emission lines into an observed RC. The kinematic centre of a galaxy by definition has no Doppler shift. Its exact position significantly influences the shape of the RC and must therefore be derived with care. Primarily, we determine the kinematic centre of a galaxy to within  by fitting a Gaussian to its (spatial) luminosity profile at the spectral position of the emission line, i.e. the luminous centre is assumed to be also the kinematic centre. In a second step, we slightly shift the centre by up to ± 1.5 pixels, minimising the RC asymmetry adopting an asymmetry measure defined in Dale et al. (2001). We extracted RCs from at least one emission line of 182 different galaxies (86 in the field and 96 in the cluster).

by fitting a Gaussian to its (spatial) luminosity profile at the spectral position of the emission line, i.e. the luminous centre is assumed to be also the kinematic centre. In a second step, we slightly shift the centre by up to ± 1.5 pixels, minimising the RC asymmetry adopting an asymmetry measure defined in Dale et al. (2001). We extracted RCs from at least one emission line of 182 different galaxies (86 in the field and 96 in the cluster).

3.3. Rotation-curve modelling

At face value, an extracted RC only traces the line-of-site rotation velocity of a galaxy. This observed position-velocity information does not represent the intrinsic rotation of a disc galaxy. Several geometric and observational effects have to be taken into account. The inclination of the disc with respect to the line-of-sight, the position angle of the galaxy’s apparent major axis with respect to the direction of dispersion, beam-smearing due to the integration along the slit width, and seeing effects may disguise the intrinsic shape of the RC. For a detailed discussion see Böhm et al. (2004).

Modelling the galaxy as an infinitely thin rotating disc (tilted ring model) with an exponential intensity profile and simulating the spectroscopic observation process produces a synthetic RC. Matching the synthetic RC thus obtained with the actual observed RC allows the true intrinsic RC parameters to be inferred from the best-fitting simulated RC.

As input parameters for the whole simulation process, we use the redshift of the galaxy, the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the seeing disc, the photometric scale length rd, the inclination angle i, and the position angle θ of the galaxy. We obtain the photometric scale length rd by fitting a two-component model with GALFIT (Peng et al. 2002) to the corresponding HST/ACS V-band images. We assume a de Vaucouleurs profile for the bulge and an exponential profile for the disc. We stress that the RC modelling explained below is robust against the assumed morphology, and changes in the morphological decomposition (like a free-n Sérsic bulge, for example) do not affect our results. Values of the axis ratio a/b (a and b are the apparent semi-major and semi-minor axes, respectively) and the position angle were previously determined using the SExtractor package (Bertin & Arnouts 1996) on the HST/ACS V-band images and are adopted from the STAGES master catalogue (Gray et al. 2009b). Assuming an intrinsic disc thickness of q = 0.2, we computed the inclination from the axis ratio (e.g. Tully et al. 1998).

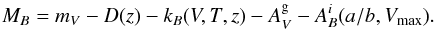

A robust value for the FWHM of the seeing disc is an important ingredient in correctly simulating the observation process. The presence of three reference star spectra in each quadrant of a pointing allows us to determine the seeing conditions during spectroscopy. This is clearly superior to estimates inferred from the Differential Image Motion Monitor (DIMM). We determine the FWHM of the stellar spectra along the spectral axis for each MOS image. We adopt the median of the three reference stars as our input parameter for the simulation. Seeing values increase towards shorter wavelengths and a standard equation to describe this variation is given by Sarazin (2003) (3)where we use λc = 5100 Å as the central wavelength of the HR-blue grism. We obtain seeing values between

(3)where we use λc = 5100 Å as the central wavelength of the HR-blue grism. We obtain seeing values between  and

and  with an average of

with an average of  .

.

In the following, we describe the simulation process in more detail. We assume an intrinsic rotation function of the form (Courteau 1997)  (4)At the turn-over radius rt the linear rise for small radii (rigid-body region) turns over into a flat region with asymptotic velocity Vmax, where the dark matter halo dominates the mass distribution. The factor α determines the sharpness of the turnover and is set to α = 5 (Böhm et al. 2004). Hence, Vmax and rt are the two remaining free parameters in the fitting process.

(4)At the turn-over radius rt the linear rise for small radii (rigid-body region) turns over into a flat region with asymptotic velocity Vmax, where the dark matter halo dominates the mass distribution. The factor α determines the sharpness of the turnover and is set to α = 5 (Böhm et al. 2004). Hence, Vmax and rt are the two remaining free parameters in the fitting process.

As a starting point for the simulation process, we generate a two-dimensional (2D) exponential intensity profile on a pixel grid  (5)where

(5)where  and I0 is the intensity at the galactic centre at the pixel position (x,y) = (0,0). Then we superimpose (on this intensity profile) a 2D velocity field using the above rotational law (Eq. (4)). This results in a rotating disc seen face-on. In the next step, we obtain the correct geometric projection. To this end, we rotate our galaxy, i.e. the 2D intensity and velocity field, according to the inclination angle i (rotation around the y-axis) and the position angle θ (rotation around the line-of-sight or z-axis). For the velocity field we calculate the line-of-sight component only, since this is the component that is responsible for the Doppler shift and so measured in a spectrum. We show an example of a projected 2D intensity and velocity field in Fig. 2 (left panel).

and I0 is the intensity at the galactic centre at the pixel position (x,y) = (0,0). Then we superimpose (on this intensity profile) a 2D velocity field using the above rotational law (Eq. (4)). This results in a rotating disc seen face-on. In the next step, we obtain the correct geometric projection. To this end, we rotate our galaxy, i.e. the 2D intensity and velocity field, according to the inclination angle i (rotation around the y-axis) and the position angle θ (rotation around the line-of-sight or z-axis). For the velocity field we calculate the line-of-sight component only, since this is the component that is responsible for the Doppler shift and so measured in a spectrum. We show an example of a projected 2D intensity and velocity field in Fig. 2 (left panel).

|

Fig. 2 Simulated 2D intensity and velocity field of a galaxy. The fields are projected according to the inclination and position angle (here i = 40° and θ = 30°). The direction of dispersion is along the y-axis. The exponential intensity profile is depicted in blue colour scale (here the scale length is rd = 5.3 pix). Isophotes corresponding to 50%, 30%, and 15% of the central intensity are superimposed (black dotted ellipses). The coloured curves (spider-diagram) indicate iso-velocity lines ranging from − 60%Vmax(red) to 60%Vmax(blue) in steps of 10%. Right panel: the intensity and velocity field is additionally convolved with a Gaussian point spread function ( |

Besides geometric projection effects, we also have to consider the blurring effect due to seeing. We take this into account by convolving the intensity and velocity field with a Gaussian point spread function (PSF; the FWHM is obtained from the seeing value during spectroscopy). Then, as in the observations, we place a slit along the apparent major axis of the galaxy. For the following slit integration the velocity field is weighted by the normalised intensity profile, since velocities stemming from brighter regions contribute more to the signal in a spectrum. Prior to this intensity weighting of the velocity field, we shift the intensity profile according to the mismatch between the kinematic and luminous centre, which we determined in the course of RC extraction (see Sect. 3.2). Then, for each pixel position along the spatial axis (x-axis) the velocity values within the slit borders are integrated along the direction of dispersion (y-direction). Note that the integration is in general not perpendicular to the slit direction since most MOS slits are tilted. Effectively, we calculate an intensity-weighted average of the velocity values inside the slit at each spatial position. For the integration area at each spatial position we account for the size of the boxcar filter (3 or 5 pixels) that was used for the extraction of the RC. Thus, we obtain a simulated value for the rotation velocity at the position of each pixel along the spatial axis. This position-velocity information is the end product of our simulation and defines a synthetic RC. The right panel of Fig. 2 shows a scheme of the integration process of the PSF-convolved and intensity-weighted velocity field. Unlike the situation shown in the figure, we oversample the pixel grid by a typical factor of five to improve the precision of the computation.

3.4. Rotation-curve fitting

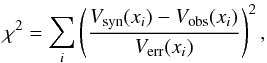

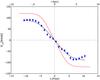

For each galaxy we vary the free parameters (Vmax, rt) of the synthetic RC so that it best fits the observed RC. We do this by minimizing the error-weighted χ2 (6)where the xi are the spatial positions of the observed RC and the simulated RC with velocities Vobs(xi) and uncertainties Verr(xi). As do Pizagno et al. (2007), we add 5 km s-1 in quadrature to all velocity uncertainties to avoid the fit being dominated by high S/N data points. This is motivated by non-circular motions of the same magnitude, present in all disc galaxies. We use the photometric scale length rd and a typical value of 100 km s-1 as initial guesses for the free parameters rt and Vmax. Figure 3 gives an example of a best-fitting synthetic RC and the inferred intrinsic rotation velocities. Note that while the observed data points and the best-fitting RC are plotted against the pixel position along the spatial axis (i.e. perpendicular to the direction of dispersion), the intrinsic RC shows the intrinsic rotational velocities (see Eq. (4)) as a function of galacto-centric radius.

(6)where the xi are the spatial positions of the observed RC and the simulated RC with velocities Vobs(xi) and uncertainties Verr(xi). As do Pizagno et al. (2007), we add 5 km s-1 in quadrature to all velocity uncertainties to avoid the fit being dominated by high S/N data points. This is motivated by non-circular motions of the same magnitude, present in all disc galaxies. We use the photometric scale length rd and a typical value of 100 km s-1 as initial guesses for the free parameters rt and Vmax. Figure 3 gives an example of a best-fitting synthetic RC and the inferred intrinsic rotation velocities. Note that while the observed data points and the best-fitting RC are plotted against the pixel position along the spatial axis (i.e. perpendicular to the direction of dispersion), the intrinsic RC shows the intrinsic rotational velocities (see Eq. (4)) as a function of galacto-centric radius.

|

Fig. 3 Example of RC fitting. The blue squares indicate the observed rotation velocities as a function of the position along the spatial axis of the spectrum (in pix). The black line depicts the best-fit synthetic RC to these data points. From the best-fit parameters (here Vmax = 118 km s-1, rt = 4.1 pix) we can infer the intrinsic shape of the RC (in red). Here the x-axis is the galactocentric radius (in kpc) (here , , z = 0.17, |

RCs that lack data points in the flat region tend to result in overestimated turnover radii and Vmax-values. To tackle this issue we constrain rt in the minimisation process (a python implementation of a Sequential Least SQuares Programming (SLSQP) optimisation, originally by Kraft 1988). We allow the best-fit rt-values to vary only within a σt-interval around the initial value rd. We determine the scatter σt solely using RCs that result in best-fit Vmax-values changing by less than 5% when fitted with or without rt as a free parameter; σt is then set to be the standard deviation of the relative differences between rd (i.e. rt held fixed) and rt (i.e. rt free parameter), multiplied by rd. We obtain a value of σt = 0.176 ∗ rd.

We estimate the errors of the best-fit parameters Vmax and rt by generating bootstrap samples of a given observed RC and calculating the standard deviation for the distribution of the best-fit parameters obtained from each iteration. To this end, for each data point (at a certain position xi) the velocity value Vobs(xi) is drawn from a Gaussian distribution with mean value Vobs(xi) and dispersion Verr(xi). Additionally, in each bootstrap iteration two data points are randomly excluded from the fitting process to account for a possible strong influence of single values on the best-fit parameters. Furthermore, the inclination and position angle are allowed to vary for each bootstrap iteration according to a normal distribution around the preset value (with a scatter σ = 2°). This accounts for the uncertainty in the derivation of the inclination angle and a possible slight misalignment between slit direction and apparent major axis.

3.5. Rotation-curve quality assessment

Prior to any RC fitting, we inspect each RC visually and classify it according to the following scheme: non-rotating, low-quality TF object, high-quality TF object. The non-rotating class holds galaxies for which a clear distinction between an approaching and receding side is not feasible. Only five galaxies fall into this class (all of them cluster members). We exclude these objects from further analysis. TF objects (176 in total) show reasonable disc rotation. We assign galaxies to the low-quality class when they have a high degree of distortion, an RC with small extent or rigid-body rotation.

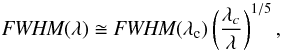

A more quantitative measure for the suitability of a galaxy as a TF object is provided by the (error-weighted) root mean square (rms) of the RC fit, i.e. the normalised sum of the squared differences between the data points and the best-fit curve. RCs deviating from a Courteau model (see Eq. (4)) will inevitably produce higher rms values than undistorted ones. Since absolute rms values by construction are higher for fast rotators, a normalised rmsn = rms/Vmax is a more reliable measure. Of course, symmetric RCs that do not sufficiently trace the flat region or are identified as rigid body rotators, might also result in low rms values, despite being classified as low-quality objects. Hence, the correlation between the visual classification and the rmsn measure is not expected to be one-to-one. Figure 4 plots the fraction of high-quality objects as a function of the rmsn values. Both measures are well correlated and result in a highly significant (p < 0.01%) Spearman rank-correlation of ρ = − 0.52.

Table 1 gives an overview of the mean rmsn values for various subsamples and confirms that high-quality objects have lower rmsn values than low-quality objects. This indicates that the latter on average have more distorted kinematics, i.e. their deviation from an ideal Courteau model is stronger. This higher degree of kinematic distortion is also reflected in the mean values of the asymmetry measures defined in Paper I. There, we introduced an asymmetry index A following Dale et al. (2001), which compares corresponding rotation velocities between the approaching and receding side of a RC, and a visual asymmetry parameter Avisual2, which distinguishes between three classes: undistorted (0), slightly distorted (1) and heavily distorted (2). High-quality objects (A = 14 ± 1%, Avisual2 = 0.51 ± 0.06) have significantly lower values than low-quality objects (A = 49 ± 6%, Avisual2 = 1.10 ± 0.10) in both classification schemes.

|

Fig. 4 rmsn distribution for the low-quality (thick line) and high-quality (thin hatched line) TF objects of our whole sample. For each histogram bin, the relative fraction of high-quality objects is depicted (black squares). It is well correlated with the rmsn value of the RC fit. |

Mean rmsn values from RC fitting for our sample, as well as for certain subsets.

3.6. Linear regression

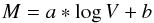

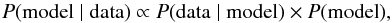

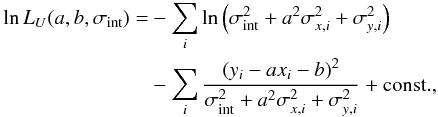

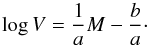

Various methods are used in the literature for fitting a regression line to data points. We obtained a TFR of the form  (7)by following Pizagno et al. (2007) and adopting a maximum-likelihood (ML) method to determine the slope a and intercept b (see also Bamford et al. 2006; Weiner et al. 2006). Applying Bayes’ theorem allows us to calculate the probability of a model given the observed data

(7)by following Pizagno et al. (2007) and adopting a maximum-likelihood (ML) method to determine the slope a and intercept b (see also Bamford et al. 2006; Weiner et al. 2006). Applying Bayes’ theorem allows us to calculate the probability of a model given the observed data  (8)where P(model) is the prior. Flat priors are sufficient in most cases (D’Agostini 2005), hence they drop out of the equation. In contrast to ordinary least square (OLS) methods this Bayesian approach allows us to include observational errors on both axes as well as an intrinsic scatter σint. Even if measurement errors were negligible, a relationship between two physical variables would have some scatter. This intrinsic scatter reflects variations in physical parameters that are not explained by the scatter of the observables alone (Kelly 2007). We assume Gaussian distributions for the (uncorrelated) observational errors as well as for the intrinsic scatter. We also assume a uniform intrinsic distribution of the independent variable xi, so that the log-likelihood to maximise reads (e.g. Pizagno et al. 2007)

(8)where P(model) is the prior. Flat priors are sufficient in most cases (D’Agostini 2005), hence they drop out of the equation. In contrast to ordinary least square (OLS) methods this Bayesian approach allows us to include observational errors on both axes as well as an intrinsic scatter σint. Even if measurement errors were negligible, a relationship between two physical variables would have some scatter. This intrinsic scatter reflects variations in physical parameters that are not explained by the scatter of the observables alone (Kelly 2007). We assume Gaussian distributions for the (uncorrelated) observational errors as well as for the intrinsic scatter. We also assume a uniform intrinsic distribution of the independent variable xi, so that the log-likelihood to maximise reads (e.g. Pizagno et al. 2007)  (9)where σy,i and σx,i are the measurement errors of the dependent variable yi and independent variable xi, respectively. Compared to traditional least-squares methods, this fitting approach has the advantage that data points with large errors in either of the variables will have less influence on the final result. Moreover, the inclusion of the intrinsic scatter prevents data points with very small observational errors from dominating the fit.

(9)where σy,i and σx,i are the measurement errors of the dependent variable yi and independent variable xi, respectively. Compared to traditional least-squares methods, this fitting approach has the advantage that data points with large errors in either of the variables will have less influence on the final result. Moreover, the inclusion of the intrinsic scatter prevents data points with very small observational errors from dominating the fit.

|

Fig. 5 B-band luminosity histogram of our spectroscopic sample. The red solid line depicts a Hanning-smoothed fit to this histogram. The blue dashed line indicates a Schechter fit to the bright end ( |

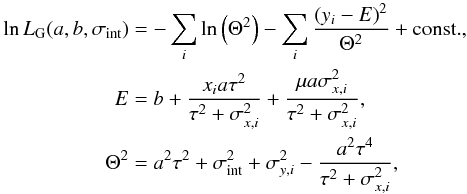

However, Kelly (2007) emphasised that adopting a uniform distribution for the independent variable can produce a bias in the ML estimate and is not appropriate for most situations (as is the case for the distribution of the absolute B-band magnitudes of our sample, see Fig. 5). Instead, they proposed approximating the intrinsic distribution of the independent variable using a mixture of Gaussian functions. For simplicity, we adopt a single Gaussian with mean μ and variance τ2 determined from a fit to the histogram of the independent variable of our whole sample. Then, the log-likelihood of Eq. (9) becomes  (10)where E and Θ2 are the expectation value and variance of yi at xi, drawn from a Gaussian distribution with mean μ and variance τ2. The covariance between the observational errors σy,i and σx,i was set to zero. For τ2 → ∞, i.e. an infinitely broad Gaussian, LG of Eq. (10) converges to LU of Eq. (9).

(10)where E and Θ2 are the expectation value and variance of yi at xi, drawn from a Gaussian distribution with mean μ and variance τ2. The covariance between the observational errors σy,i and σx,i was set to zero. For τ2 → ∞, i.e. an infinitely broad Gaussian, LG of Eq. (10) converges to LU of Eq. (9).

We are aware that the intrinsic distribution of luminosities is most likely a Schechter-like function. However, a Gaussian is a good approximation to the observed luminosity function of spiral galaxies only (Binggeli et al. 1988). Furthermore, it is in any case more realistic than a flat distribution. We performed the minimisation of the (negative) log-likelihood using a downhill simplex algorithm. We estimated the errors of the best-fit parameters a, b, and σint utilising bootstrap simulations (n = 1000).

Instead of fitting the forward TFR of Eq. (7), i.e. y = M and x = log V, many studies use the inverse relation  (11)The inverse fit, i.e. the velocity treated as the dependent variable, is less prone to incompleteness biases that arise from the magnitude limit of a sample (Tully & Courtois 2012; Willick 1994). Kelly (2007) demonstrated that if the sample selection is based on the independent variable of the fit (the luminosity in our case), then the best-fit parameters are not influenced by selection effects. However, treating either the luminosity (forward fit) or the velocity (inverse fit) as the dependent variable does not reflect the situation properly, since by construction in each case the scatter in the dependent variable is minimised. To study the underlying relationship between two observables a method treating them symmetrically could be more appropriate. Such methods utilise both the forward and the inverse best-fit parameters to calculate a best-fit slope that lies between the two extremes. Isobe et al. (1990) describe for instance bisector regression, orthogonal regression, or reduced major-axis regression. Tully & Courtois (2012) simulated the selection bias for different fitting methods and recommend the inverse relation when using the TFR as a means of distance measurement. On the other hand, to study the physical impacts on the TFR a bivariate fit would be a good compromise.

(11)The inverse fit, i.e. the velocity treated as the dependent variable, is less prone to incompleteness biases that arise from the magnitude limit of a sample (Tully & Courtois 2012; Willick 1994). Kelly (2007) demonstrated that if the sample selection is based on the independent variable of the fit (the luminosity in our case), then the best-fit parameters are not influenced by selection effects. However, treating either the luminosity (forward fit) or the velocity (inverse fit) as the dependent variable does not reflect the situation properly, since by construction in each case the scatter in the dependent variable is minimised. To study the underlying relationship between two observables a method treating them symmetrically could be more appropriate. Such methods utilise both the forward and the inverse best-fit parameters to calculate a best-fit slope that lies between the two extremes. Isobe et al. (1990) describe for instance bisector regression, orthogonal regression, or reduced major-axis regression. Tully & Courtois (2012) simulated the selection bias for different fitting methods and recommend the inverse relation when using the TFR as a means of distance measurement. On the other hand, to study the physical impacts on the TFR a bivariate fit would be a good compromise.

We chose to use the inverse fit when comparing different populations or distant to local studies. However, for the investigation of TF residuals (luminosity offsets) we used the bisector parameters calculated from the forward and inverse fits as in Isobe et al. (1990). Whatever the type of fit, we always report the resulting parameters in terms of a forward relation.

|

Fig. 6 Simulated incompleteness bias obtained from Monte-Carlo simulations. The data points depict the average TF residual for the given velocity. The blue solid line indicates a linear fit to these data points. |

3.7. Incompleteness bias correction

By construction, magnitude-limited samples result in an incomplete coverage of the faint end of the luminosity function. In a TF sample with magnitude limit, faint slow rotators are under-represented. In the end, this leads to an underestimation of the TFR slope accompanied by an overestimation of the intercept. Giovanelli et al. (1997) developed a method to account for this bias. First of all, we have to assume an intrinsic luminosity distribution according to a Schechter luminosity function. Figure 5 shows a histogram of the B-band luminosities and a Hanning-smoothed fit to this histogram. This fit is then compared to a fit of a Schechter luminosity function to the bright end of the data ( ). For these luminosities, the sample is assumed to be complete. The ratio between the two lines (maximum set to 1) provides us with a measure c(MB) for the completeness of the sample.

). For these luminosities, the sample is assumed to be complete. The ratio between the two lines (maximum set to 1) provides us with a measure c(MB) for the completeness of the sample.

To simulate the incompleteness bias we generated Monte-Carlo simulations with 104 iterations. For a given rotation velocity a luminosity was calculated according to an intrinsic TFR. The TFR scatter was simulated by randomly drawing from a normal distribution with a dispersion equal to the scatter in our data. The luminosity value MB thus obtained now has the probability c(MB) to enter the sample. Of course, fainter galaxies have a lower chance of being considered. The average residual from the TFR gives an estimate of the magnitude bias for a given rotational velocity (see Fig. 6). The magnitude bias ΔMB = f(V2.2) is then approximated by a linear fit. To account for the slightly different luminosity and redshift distributions of the field and cluster sample, the magnitude bias was computed for the two populations separately.

4. Tully-Fisher relations

Quantitative comparisons between different TF studies are very difficult. First of all, there can be differences in the observational approach. The rotation of a galaxy may be traced by radio data of the H i disc, for example, or by optical emission lines stemming from H ii regions. Radio observations have the advantage of tracing the rotation of a galaxy to large radii where the dark matter halo dominates the mass density (e.g. Verheijen 2001). Pizagno et al. (2007) pointed out that obtaining velocity-widths from H i RCs results in rotation velocities systematically higher for fainter galaxies compared to optical observations. This leads to a shallower TFR. Furthermore, some studies use integrated line-width while others exploit spatially resolved RCs or even velocity fields. Compared to the traditional long-slit spectroscopy, IFU (integral field unit) velocity fields might be superior in identifying galaxies with distorted and peculiar kinematics. Besides this, differences in sample selection (magnitude limit, morphological type, constraints on kinematic distortion), different fitting methods, and considerations of observational effects are the most common sources of discrepancies. To avoid a possible bias, we focus on the comparison of subsamples in our analysis, e.g. between field and cluster galaxies or the blue cloud and dusty red population.

Studies designed to use the TFR as a distance indicator (usually with the goal of constraining the Hubble constant H0), need a pruned sample containing only model galaxies such as undistorted late-type spirals. This guarantees a tight TFR with a small scatter. However, we also intend to investigate galaxies that deviate from this ideal, which might reveal information on interaction mechanisms in the cluster environment.

4.1. Basic fits

Table 2 gives an overview of the parameter estimates using the maximum-likelihood method with a Gaussian intrinsic distribution of the independent variable (Eq. (10)). Note that using a uniform intrinsic distribution instead (Eq. (9), not shown in the table) yields consistent values within the 1σ errors.

Parameter estimates using the maximum-likelihood method with a Gaussian intrinsic distribution of the independent variable.

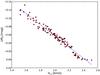

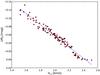

First, we concentrate on the B-band TFR using only RCs of our high-quality class. Inverse fits to the sample of field galaxies (57 objects, a = −7.51 ± 0.81) and cluster galaxies (55 objects, a = −6.58 ± 0.61) yield consistent slopes within the 1σ-errors. Hence, in the following sections we mainly use a fixed slope, determined from an inverse fit to the combined sample of cluster and field galaxies. This is a common approach to reduce the number of free parameters and is justified because most other TF studies also do not find significant differences in the slope between cluster and field galaxies (Bamford et al. 2006; Moran et al. 2007; Nakamura et al. 2006; Ziegler et al. 2003). Figure 7 shows an inverse fit to the high-quality objects of our whole sample. As a comparison we also depict the (shallower) slopes of the bisector and forward fit as well as the position of the low-quality galaxies.

Note that an inverse fit minimises the scatter with respect to the rotation velocity and not to the luminosity. Hence, an intrinsic scatter obtained from an inverse fit and transformed into a value with respect to the luminosity is always larger than if directly obtained using a forward fit. This needs to be considered when comparing results to studies that adopt a forward fit. Furthermore, reducing the number of free parameters (e.g. holding the slope fixed) can also slightly change the best-fit intrinsic scatter.

|

Fig. 7 B-band TFR for the combined sample of cluster (55) and field (57) galaxies. Only high-quality objects are considered. The blue solid line indicates the best-fit inverse regression line. The blue dotted lines depict the corresponding 1σ and 3σ intervals, respectively. The green and red lines are the best-fit forward and bisector fits, respectively. Black open circles indicate the positions of the low-quality objects. |

For the stellar-mass TFR the parameters of field and cluster galaxies also agree within the error bars. Including the low-quality objects in the fit (176 objects in total) increases the intrinsic scatter significantly (see Table 2). Interestingly, the best-fit (inverse) values for slope and intercept barely change. This is mainly due to the weighting capability of our linear regression method. The adopted bootstrapping method for RC fitting (see end of Sect. 3.4) assigns larger errors to low-quality objects (δV = 19 ± 3 km s-1) compared to high-quality objects (δV = 10 ± 1 km s-1).

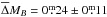

For fixed slopes (a = − 7.04 and a = 3.04 for the B-band and stellar-mass TFR) we find a difference of  and ΔM∗ = 0.46 ± 0.16 when comparing the TF intercept between low- and high-quality objects individually, i.e. distorted objects are preferentially located above the TFR of high-quality objects. This means they are, on average, too luminous/stellar-massive for a given velocity or have a velocity that is too low for a given luminosity/stellar mass. The comparable shifts (ΔV2.2 ~ 0.12 ± 0.5, when transformed into a velocity shift) for the stellar-mass and the B-band TFR, as well as a similar increase in the intrinsic scatter (σint ~ 0.18 ± 0.3 in velocity), indicate that an underestimated rotation velocity is the main cause of this shift for low-quality objects.

and ΔM∗ = 0.46 ± 0.16 when comparing the TF intercept between low- and high-quality objects individually, i.e. distorted objects are preferentially located above the TFR of high-quality objects. This means they are, on average, too luminous/stellar-massive for a given velocity or have a velocity that is too low for a given luminosity/stellar mass. The comparable shifts (ΔV2.2 ~ 0.12 ± 0.5, when transformed into a velocity shift) for the stellar-mass and the B-band TFR, as well as a similar increase in the intrinsic scatter (σint ~ 0.18 ± 0.3 in velocity), indicate that an underestimated rotation velocity is the main cause of this shift for low-quality objects.

4.2. Cluster vs. field relation

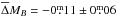

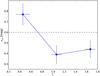

Holding the TFR slope fixed at a = −7.04, we now compare the B-band TFR of high-quality cluster and field galaxies. We find an offset between the two populations (Fig. 8, left panel) with field galaxies being slightly brighter than their cluster counterparts ( ).

).

Furthermore, we find a slight difference between the mean SED types. Field galaxies have, on average, a bluer SED than cluster galaxies (⟨ Ttype ⟩ = 5.8 vs. 5.2 ± 0.2), which could explain part of the offset in the TFR. T-types of 5 and 6 correspond to typical spectra of Sc and Scd spirals, respectively. A linear fit to the relation of the B-band residuals as a function of the SED-type yields a brightening of  for an SED-type change of ΔTtype = 1.

for an SED-type change of ΔTtype = 1.

Another aspect might be the deviating redshift distribution of both samples. According to a trend seen in previous TF-evolution studies (e.g. Bamford et al. 2006; Böhm et al. 2004; Fernández Lorenzo et al. 2010; Miller et al. 2011; Weiner et al. 2006; Ziegler et al. 2002), the slightly higher redshift of our field galaxies (⟨ z ⟩ = 0.245 vs. 0.165) coincides with higher star-formation rates (e.g. Hopkins 2004) and consequently higher B-band luminosities. Most studies measure a brightening in the B-band consistent with  from z = 0 to z ~ 1. Galaxy formation models based on ΛCDM cosmology (Dutton et al. 2011) produced similar values (

from z = 0 to z ~ 1. Galaxy formation models based on ΛCDM cosmology (Dutton et al. 2011) produced similar values ( ). Hence, we would expect an offset of

). Hence, we would expect an offset of  stemming from the redshift difference between our cluster and field samples.

stemming from the redshift difference between our cluster and field samples.

Altogether, systematic differences in the composition of the cluster and field samples may account for half of the observed offset in the B-band intercept. The cluster environment associated with a quenching of star-formation could be responsible for the remaining difference ( ), but this difference is barely significant. Furthermore, if the assumption of a fixed slope between cluster and field galaxies is not fulfilled, i.e. cluster galaxies have an intrinsically shallower slope, then an underestimation of the TF intercept is expected when fixing the slope. On the other hand, under the assumption of such a luminosity-redshift correlation, the broader redshift distribution of the field sample (σz = 0.048 vs. 0.005 for the cluster, which is a factor of ~10) should result in a slightly larger TF scatter. The intrinsic scatter amounts to σint = 0.68 ± 0.06 for the cluster and σint = 0.79 ± 0.08 for the field population, which is in agreement within the errors. Given the redshift distribution of our field sample and assuming an evolution of

), but this difference is barely significant. Furthermore, if the assumption of a fixed slope between cluster and field galaxies is not fulfilled, i.e. cluster galaxies have an intrinsically shallower slope, then an underestimation of the TF intercept is expected when fixing the slope. On the other hand, under the assumption of such a luminosity-redshift correlation, the broader redshift distribution of the field sample (σz = 0.048 vs. 0.005 for the cluster, which is a factor of ~10) should result in a slightly larger TF scatter. The intrinsic scatter amounts to σint = 0.68 ± 0.06 for the cluster and σint = 0.79 ± 0.08 for the field population, which is in agreement within the errors. Given the redshift distribution of our field sample and assuming an evolution of  (e.g. Bamford et al. 2006), simulations yield an estimate of Δσ = 0.05 ± 0.02 for the increase of the scatter because of the broader redshift distribution.

(e.g. Bamford et al. 2006), simulations yield an estimate of Δσ = 0.05 ± 0.02 for the increase of the scatter because of the broader redshift distribution.

|

Fig. 8 TFR for the sample of high-quality cluster galaxies (55 objects; blue squares) and field galaxies (57 objects; green triangles). Open symbols indicate the corresponding low-quality objects. The blue dashed and green dot-dashed lines indicate the best-fit inverse regression lines of cluster and field galaxies, respectively. B-band TFR (left panel): field galaxies are brighter by |

However, the situation changes when only low-quality TF objects are considered. While the difference in the intercept is similar ( ), the intrinsic scatter for the cluster sample (35 objects; σint = 2.20 ± 0.32) is significantly higher than for the corresponding field subsample (29 objects; σint = 1.42 ± 0.25). Whereas cluster galaxies with more regular kinematics show no enhanced scatter, cluster-specific interaction processes seem to induce a larger TF scatter in galaxies with distorted kinematics.

), the intrinsic scatter for the cluster sample (35 objects; σint = 2.20 ± 0.32) is significantly higher than for the corresponding field subsample (29 objects; σint = 1.42 ± 0.25). Whereas cluster galaxies with more regular kinematics show no enhanced scatter, cluster-specific interaction processes seem to induce a larger TF scatter in galaxies with distorted kinematics.

However, when we examine the high-quality stellar-mass TFR, the differences between cluster and field galaxies disappear. Again, we fix the slope to the (inverse) value of the combined sample (a = 3.04). Then, the intercept (ΔM∗ = 0.00 ± 0.07) and intrinsic scatter (Δσint = 0.01 ± 0.04) for both populations are in total agreement. Figure 8 (right panel) illustrates the coinciding sample of cluster and field galaxies for the stellar-mass TFR.

This finding suggests that any measured differences between the TFR of cluster and field galaxies stem from different mass-to-light ratios (M/L) and hence star-formation rates affecting the B-band luminosity. It confirms that differences in luminosity and not in velocity induce the offset of the B-band TFR between cluster and field galaxies.

4.3. Local comparison samples

In the following we want to compare our sample to local TF studies. We select the B-band data of Tully & Pierce (2000, Sample T hereafter) and Verheijen (2001, Sample V hereafter) as well as the stellar-mass data of Pizagno et al. (2005, Sample P hereafter) as comparison samples. Both B-band studies exploited H i linewidth measurements W20 (at 20% of the peak flux) to derive rotation velocities, and applied the same intrinsic mass-dependent absorption correction as we do. The Tully & Pierce (2000) sample comprises 115 spirals (Sa-Sd) in various environments and was mainly designed to calibrate the TFR for subsequent H0 determination. We also use the total sample of 45 galaxies from Verheijen (2001) as a less pruned comparison sample, including objects with potentially distorted kinematics. Pizagno et al. (2005) selected 81 disc-dominated galaxies from the SDSS and derived the rotation velocity at a radius of 2.2 disc scale lengths, V2.2, from H α RCs.

Parameter estimates of local comparison samples using the maximum-likelihood method with a Gaussian intrinsic distribution of the independent variable.

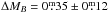

By applying the same fitting procedure to our sample and the local samples, we rule out a potential source of discrepancies. Table 3 lists the TF parameters we obtain when performing a free inverse fit and when fixing the slope to a = − 7.04 (B-band TFR) or a = 3.04 (smTFR); Fig. 9 shows an overview of the data. Both local B-band samples (left panel) have a fainter intercept than our sample. Fixing the slope yields differences in the intercept of  (Sample T) and

(Sample T) and  (Sample V), respectively. This, as well as the smaller scatter, can be most likely attributed to the higher redshift of our sample. Compared to Tully & Pierce (2000) the less strict selection constraints might also contribute to the larger scatter in our data. The best-fit slopes agree well with our values, although the relation of Sample T is slightly steeper. A lack of faint fast-rotating galaxies in our sample, especially in the cluster population, seems to be responsible for this difference. As already mentioned, this could be due in part to the derivation of rotational velocities from optical emission lines (Pizagno et al. 2007), in contrast to velocity widths computed from H i data.

(Sample V), respectively. This, as well as the smaller scatter, can be most likely attributed to the higher redshift of our sample. Compared to Tully & Pierce (2000) the less strict selection constraints might also contribute to the larger scatter in our data. The best-fit slopes agree well with our values, although the relation of Sample T is slightly steeper. A lack of faint fast-rotating galaxies in our sample, especially in the cluster population, seems to be responsible for this difference. As already mentioned, this could be due in part to the derivation of rotational velocities from optical emission lines (Pizagno et al. 2007), in contrast to velocity widths computed from H i data.

The right panel of Fig. 9 shows the stellar-mass TFR in comparison to the local data of Pizagno et al. (2005). When fixing the slope, the difference in the intercept between the local P sample and our sample is negligible (ΔM∗ = 0.01 ± 0.04). This is in agreement with previous studies that find no significant evolution of the stellar-mass TFR with redshift up to z ≲ 2 (e.g. Miller et al. 2011, 2012).

|

Fig. 9 TF data for our total sample (blue points, solid line) and the local comparison samples. The depicted regression lines are for the fixed slope of our sample. B-band (left panel): the intercept differences are |

4.4. Blue cloud vs. dusty red galaxies

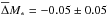

In the U − V colour−magnitude diagram, dusty red galaxies overlap with the red sequence of ellipticals and lenticulars without star formation. This is due to significant dust extinction, similar to blue cloud galaxies, along with a low level of star formation (Wolf et al. 2005). They are mainly early-type spirals and their star-formation is about four times lower than in blue cloud spirals of similar mass (Wolf et al. 2009). Hence, we expect that dusty red galaxies are located below the TFR of blue cloud galaxies. Figure 10 (left panel) confirms this expectation. The dusty red galaxies preferentially populate the region below the (bisector) regression line of the whole high-quality cluster sample (blue clouds and dusty reds). The mean (error-weighted) residual amounts to  compared to

compared to  for blue cloud galaxies, i.e. dusty red galaxies are on average

for blue cloud galaxies, i.e. dusty red galaxies are on average  fainter for a given velocity than blue cloud galaxies. The trend that the cluster slope is slightly shallower might stem from the high fraction of dusty red galaxies in our sample. They populate the intermediate-to-high mass regime of our sample and lie on average below the TFR (see Fig. 10, left panel), thus reducing the slope. Excluding the dusty red galaxies (12) from the fit yields a slope closer to the field value (43 objects, e.g. for the inverse fit a = − 7.07 ± 0.74).

fainter for a given velocity than blue cloud galaxies. The trend that the cluster slope is slightly shallower might stem from the high fraction of dusty red galaxies in our sample. They populate the intermediate-to-high mass regime of our sample and lie on average below the TFR (see Fig. 10, left panel), thus reducing the slope. Excluding the dusty red galaxies (12) from the fit yields a slope closer to the field value (43 objects, e.g. for the inverse fit a = − 7.07 ± 0.74).

|

Fig. 10 TFR for the sample of high-quality cluster galaxies, separated into dusty red galaxies (red stars) and blue cloud galaxies (blue squares). The black line indicates the best-fit bisector regression line for the whole cluster sample. Fixing the slope to this value, the red dash-dotted and blue dashed lines depict the corresponding best-fit lines for dusty reds and blue clouds, respectively. B-band (left panel): for a given velocity, dusty red galaxies are on average |

The right panel of Fig. 10 shows the same comparison between dusty red and blue cloud galaxies, but this time for the stellar-mass TFR. Here, the mean (error-weighted) residuals from the bisector regression line are  for dusty red and

for dusty red and  for blue cloud galaxies, respectively. In contrast to the B-band residuals, this is an insignificant difference (ΔM∗ = 0.06 ± 0.05). This suggests that at a given rotational velocity, dusty red galaxies have similar stellar masses to blue cloud galaxies. A difference only appears in the B-band TFR as a result of different M/L values.

for blue cloud galaxies, respectively. In contrast to the B-band residuals, this is an insignificant difference (ΔM∗ = 0.06 ± 0.05). This suggests that at a given rotational velocity, dusty red galaxies have similar stellar masses to blue cloud galaxies. A difference only appears in the B-band TFR as a result of different M/L values.

The offset in the average B-band residuals fits into the scenario that dusty red galaxies might be the progenitors of S0 galaxies which are found to lie below the TFR of spiral galaxies (Aragón-Salamanca 2008). Cortesi et al. (2013) investigated the kinematics of six S0 galaxies exploiting spectra of planetary nebulae. Besides a position of the disc components below the TFR of local spirals, they also found that the bulge components populate the region above the Faber-Jackson relation of elliptical galaxies. In other words, bulges are too bright but the discs are too faint for a given velocity measure. Furthermore, the discs exhibit an increased fraction of random motion compared to spiral galaxies. Cortesi et al. (2013) pointed out that neither a quiescent scenario like disc-fading nor a violent interaction like merging are likely explanations of the observations. A milder process like ram-pressure would, however, be well in compliance with what we find.

Our sample of 182 disc galaxies contains 14 objects (11 in the cluster; 3 in the field) with an S0 morphology; 22% of the cluster galaxies with spiral morphology are dusty red galaxies, and 9 of 11 lenticulars (82%) have a dusty red SED-type. Only four cluster S0 galaxies show high-quality RCs. Their mean (error-weighted) residual is  which is even fainter than the average dusty-red population. The small number statistics do not allow us to draw conclusions here, but the numbers fit into the transformation scenario.

which is even fainter than the average dusty-red population. The small number statistics do not allow us to draw conclusions here, but the numbers fit into the transformation scenario.

5. Tully-Fisher residuals

Several effects might influence the position of a galaxy in the TF plane. On the one hand, enhanced star-formation or higher dust-extinction rates can shift a galaxy along the luminosity axis, but do not affect stellar mass (changes in M/L and L cancel out). On the other hand, a high fraction of non-circular motion, possibly caused by kinematic distortions, can change the radial velocity profile and the measured rotational velocity. Variations in the stellar mass-to-light ratio or stellar-to-total mass ratio induce shifts in the TF plane (Kannappan et al. 2002).

|

Fig. 11 rmsn from RC fitting as a function of morphological asymmetry Amorph for blue cloud (43), dusty red (12), and field galaxies (57). Only high-quality objects are considered. |

In this section we mainly focus on the analysis of the B-band ΔMB and stellar-mass residuals ΔM∗. We examine their correlation with other parameters as well as a possible dependence on environment. We focus on the population of dusty red galaxies and investigate whether differences to blue cloud galaxies exist. As a proxy for environment we adopt the scaled cluster-centric radius rs = r/r200 from Paper I. For a given subcluster, r is the projected cluster-centric distance and r200 is the radius where the mean interior density is 200 times the critical density.

|

Fig. 12 Mean residuals of the B-band TFR for the sample of high-quality cluster galaxies, separated into dusty red (red stars) and blue cloud galaxies (blue squares) as well as for the field sample (green triangles). Left panel: the correlation with morphological asymmetry is highly significant for blue cloud and field galaxies. Middle panel: galaxies with high specific star-formation rates tend to lie above the TFR. Right panel: dusty red (ρ = − 0.50, p = 4.0%) and blue cloud (ρ = 0.39, p = 0.5%) galaxies show opposite correlations as a function of cluster-centric distance. |

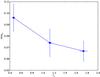

Furthermore, we also wish to have a measure for the asymmetry of the stellar disc at hand and we adopt the index Amorph, which is computed by comparing an image to itself rotated by 180° (Conselice et al. 2000). The index Amorph quantifies the degree of morphological distortions (see also Paper I). Figure 11 shows the normalised rms as a function of the morphological asymmetry Amorph. This plot resembles a plot from Paper I (Figs. 13 and 17), but this time the rotational asymmetry is parametrised by rmsn, i.e. the deviation of an observed RC from its best-fit Courteau model. Field galaxies that are more kinematically distorted exhibit higher morphological asymmetry. A Spearman rank-order correlation test yields a significant (p = 2.7%) correlation of ρ = 0.31. On the other hand, dusty red galaxies (ρ = − 0.58, p = 4.4%) have higher rmsn for a low Amorph. Although blue cloud galaxies show no significant correlation, they have − compared to field galaxies − also increased rmsn values for smooth stellar discs. Following our argument in Paper I, interaction processes that affect the morphology (galaxy-galaxy interactions, harassment) most likely also distort the gaseous disc of a galaxy and thus perturb its RC. Depending on the ICM density and the relative velocities, ram-pressure (∝ , Gunn & Gott 1972) is able to significantly influence the gas content of a galaxy and strip part of its material, while not affecting its stellar disc (Chung et al. 2008; Kenney et al. 2004; Kronberger et al. 2008b; Quilis et al. 2000). In the field, the rmsn of the RC-fitting positively correlates with morphological disturbances. There, low relative velocities of galaxies favour tidal interactions. For morphologically undistorted cluster galaxies and especially dusty red galaxies, a cluster-specific mechanism that effectively distorts the RC but leaves the stellar disc unaffected is required. Ram-pressure stripping is the best candidate process.

, Gunn & Gott 1972) is able to significantly influence the gas content of a galaxy and strip part of its material, while not affecting its stellar disc (Chung et al. 2008; Kenney et al. 2004; Kronberger et al. 2008b; Quilis et al. 2000). In the field, the rmsn of the RC-fitting positively correlates with morphological disturbances. There, low relative velocities of galaxies favour tidal interactions. For morphologically undistorted cluster galaxies and especially dusty red galaxies, a cluster-specific mechanism that effectively distorts the RC but leaves the stellar disc unaffected is required. Ram-pressure stripping is the best candidate process.

Interestingly, low-quality and high-quality objects have the same mean morphological asymmetry (Amorph,lq = 0.20 ± 0.01; Amorph,hq = 0.22 ± 0.02). This is in agreement with Jaffé et al. (2011), who also do not find a direct link between the morphological asymmetries in the stellar disc and the fraction of good RC fits. This raises the question of whether the stellar asymmetry of a galaxy influences its offset from the best-fit TFR at all. Figure 12 (left panel) shows that for the class of high-quality objects a higher morphological asymmetry induces a brighter B-band residual. The correlations are highly significant (p < 0.1%) for the field population (ρ = − 0.47) and the cluster blue cloud population (ρ = − 0.45). Dusty red galaxies, on the other hand, produce no significant correlation (ρ = 0.20, p = 27.9%). The same behaviour is seen for low-quality objects (not shown in the figure).

Galaxies with a higher morphological asymmetry index tend to have a later SED type and higher star-formation rates, which, in turn, leads to brighter residuals. Giovanelli et al. (e.g. 1997) also found slightly fainter TF offsets for more early-type galaxies. This could explain part of these correlations. On the other hand, galaxy-galaxy interactions, accompanied by morphological distortions, can induce a star-formation enhancement and consequently result in larger TF offsets (e.g. Alonso et al. 2004; Lambas et al. 2003).

|

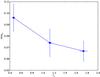

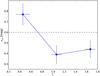

Fig. 13 Intrinsic B-band scatter σint for three rs-bins for the sample of high-quality cluster galaxies. The horizontal black dashed line depicts the intrinsic scatter of the total cluster sample. |

|

Fig. 14 rmsn from RC fitting as a function of cluster-centric radius rs for the sample of high-quality cluster galaxies. The correlation is significant (ρ = − 0.30, p = 4.3%). |

Figure 12 (mid panel) confirms that galaxies with higher specific star-formation rates preferentially populate the region above the B-band TFR. Dusty red galaxies have reduced specific star formation rates. We note that we only have robust star-formation rates (determined from UV and infra-red data) of 30/55 high-quality cluster (22/43 blue clouds; 8/12 dusty reds) and 22/57 high-quality field galaxies. Our finding is in agreement with Kannappan et al. (2002) who also detect a correlation between H α equivalent widths (a proxy for specific star formation) and TF residuals.

We discuss possible environmental effects on the B-band TF residuals in Fig. 12 (right panel). The mean B-band residuals of dusty red (ρ = − 0.50, p = 4.0%) and blue cloud (ρ = 0.39, p = 0.5%) galaxies show a different behaviour as a function of cluster-centric radius. While dusty red galaxies become fainter towards the cluster centre, blue cloud galaxies tend to be more luminous at small rs. An enhanced ICM density and ram pressure may trigger star formation in the gas-rich blue cloud population (Kronberger et al. 2008a; Steinhauser et al. 2012), while the gas-poor dusty red galaxies might already be depleted of most of their gas as a result of ram-pressure stripping.