| Issue |

A&A

Volume 533, September 2011

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A26 | |

| Number of page(s) | 17 | |

| Section | Astronomical instrumentation | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201117337 | |

| Published online | 22 August 2011 | |

Circular polarization measurement in millimeter-wavelength spectral-line VLBI observations

1

Department of Astronomy and Institute for Advanced Computing Applications

and Technologies, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign,

1002 W. Green Street,

Urbana,

IL,

61801

USA

e-mail: akemball@illinois.edu

2 Department of Physics and Electronics, Rhodes University, PO

Box 94, Grahamstown, 6140, South Africa

Received:

24

May

2011

Accepted:

23

June

2011

This paper considers the problem of accurate measurement of circular polarization in imaging spectral-line VLBI observations in the λ = 7 mm and λ = 3 mm wavelength bands. This capability is especially valuable for the full observational study of compact, polarized SiO maser components in the near-circumstellar environment of late-type, evolved stars. Circular VLBI polarimetry provides important constraints on SiO maser astrophysics, including the theory of polarized maser emission transport, and on the strength and distribution of the stellar magnetic field and its dynamical role in this critical circumstellar region. We perform an analysis here of the data model containing the instrumental factors that limit the accuracy of circular polarization measurements in such observations, and present a corresponding data reduction algorithm for their correction. The algorithm is an enhancement of existing spectral line VLBI polarimetry methods using autocorrelation data for calibration, but with innovations in bandpass determination, autocorrelation polarization self-calibration, and general optimizations for the case of low SNR, as applicable at these wavelengths. We present an example data reduction at λ = 7 mm and derive an estimate of the predicted accuracy of the method of mc ≤ 0.5% or better at λ = 7 mm and mc ≤ 0.5−1% or better at λ = 3 mm. Both the strengths and weaknesses of the proposed algorithm are discussed, along with suggestions for future work.

Key words: masers / techniques: interferometric / techniques: polarimetric / stars: AGB and post-AGB

© ESO, 2011

1. Introduction

SiO maser emission acts as an important tracer of the astrophysical conditions in the near-circumstellar environments of late-type, evolved stars (Habing 1996). The maser emission is detected in vibrationally-excited, rotational molecular transitions of SiO, denoted ν = ν′, J = J′ − (J′ − 1), which have rest frequencies of order ν0 ~ 43J′ GHz. Commonly, the brightest and most frequently observed lines are the ν = 1, J = 1−0 and ν = 1, J = 2−1 transitions near 43 GHz and 86 GHz respectively.

In single-dish observations, the SiO maser emission from late-type, evolved stars shows an

appreciable degree of linear polarization: ml ~ 15−30%, or

greater (Troland et al. 1979), but a significantly

lower degree of circular polarization, with typical median values

mc ~ several percent (Barvainis et al. 1987). In a single-dish survey of SiO linear polarization

variability in evolved stars, Glenn et al. (2003)

report a mean sample linear polarization  with a dispersion of 7%. A larger single-dish survey of late-type, evolved stars in full

polarization by Herpin et al. (2006) was able to

classify mean polarization by stellar type or variability class. They report

with a dispersion of 7%. A larger single-dish survey of late-type, evolved stars in full

polarization by Herpin et al. (2006) was able to

classify mean polarization by stellar type or variability class. They report

and

and  for Mira variables,

for Mira variables,  and

and  for semi-regular variables, and

for semi-regular variables, and  and

and  for supergiant stars. Overall, the measured single-dish values are consistent with

theoretical expectations, given the non-paramagnetic nature of the SiO molecule and the

associated general theory of the propagation of polarized maser emission in the limit of

small Zeeman splitting (Goldreich et al. 1973).

for supergiant stars. Overall, the measured single-dish values are consistent with

theoretical expectations, given the non-paramagnetic nature of the SiO molecule and the

associated general theory of the propagation of polarized maser emission in the limit of

small Zeeman splitting (Goldreich et al. 1973).

Radio-interferometric observations of SiO maser emission toward late-type, evolved stars can measure the radiation properties of the SiO maser emission at high angular resolution in the full set of Stokes parameters {I,Q,U,V}. For Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI), this angular resolution is at the sub-milliarcsecond (mas) level, and is sufficient to resolve individual SiO maser components. However, the low level of mean circular SiO maser polarization, and the intrinsic millimeter observing wavelengths required for these transitions, pose challenges in Stokes V instrumental calibration of VLBI observations of SiO masers. Measurements of SiO maser circular polarization at mas angular resolution are important however, both to constrain theoretical models describing the propagation of polarized maser emission, and for the subsequent application of these theories to infer the magnitude and orientation of the underlying magnetic fields from measurements of component-level SiO maser polarization properties. Recently, for example, periodic changes in single-dish fractional circular polarization have been detected toward two SiO stars (Wiesemeyer et al. 2009), with a proposed explanation that these changes are tracing precessing planetary magnetospheres in the circumstellar environment (Wiesemeyer 2009).

In this paper we consider the instrumental factors that constrain measurements of SiO circular polarization using VLBI arrays, evaluate the degree to which these effects can be calibrated and corrected, and provide an assessment of the net accuracy of SiO circular polarization observations at 43 GHz and 86 GHz.

The development and first application of VLBI polarimetry was reported by Cotton et al. (1984) and Wardle et al. (1986). It has since grown to become a mature technique, of broad applicability; see Cawthorne et al. (1993) and Pollack et al. (2003) for example. For the frequency bands considered in the current paper, the first continuum polarization VLBI were reported at 43 GHz by Kemball et al. (1996), and at 86 GHz by Attridge (2001).

These prior works were concerned with linear polarimetry of continuum extra-galactic radio

sources. Homan & Wardle (1999) developed a

method to allow circular VLBI polarimetry of continuum sources however, by assuming a source

ensemble has  ;

this technique has been demonstrated successfully at wavelengths longer than

λ ≥ 1 cm (Homan et al. 2009), and

is discussed in further detail below. The first spectral-line polarimetry in full

Stokes {I,Q,U,V} at 43 GHz – of the

ν = 1,J = 1−0 SiO maser emission toward the Mira

variable, TX Cam – was reported by Kemball & Diamond

(1997), based on technical development described earlier by Kemball et al. (1995). Critical circular spectral-line VLBI polarimetry

of water masers in the adjacent 22 GHz band was succesfully performed by Vlemmings et al. (2002) following this same method.

;

this technique has been demonstrated successfully at wavelengths longer than

λ ≥ 1 cm (Homan et al. 2009), and

is discussed in further detail below. The first spectral-line polarimetry in full

Stokes {I,Q,U,V} at 43 GHz – of the

ν = 1,J = 1−0 SiO maser emission toward the Mira

variable, TX Cam – was reported by Kemball & Diamond

(1997), based on technical development described earlier by Kemball et al. (1995). Critical circular spectral-line VLBI polarimetry

of water masers in the adjacent 22 GHz band was succesfully performed by Vlemmings et al. (2002) following this same method.

The current paper examines the sources of instrumental and propagation errors in VLBI circular polarimetry in the λ = 7 mm and λ = 3 mm bands in more detail, and develops and tests refinements to existing calibration methods to improve the accuracy to which Stokes V and mc can be measured in such observations. We show that it is possible to refine existing calibration methods based on autocorrelation data that avoid the need for amplitude self-calibration. We demonstrate these refinements on an observed dataset, and show that an error in mc of ≤ 0.5% or better is possible in practice at λ = 7 mm and mc ≤ 0.5−1% or better at λ = 3 mm.

The paper is structured as follows: Sect. 2 describes the instrumental and propagation data model, and Sect. 3 discusses the associated data reduction methods. The analysis of a test dataset is described in Sect. 4. General discussion and conclusions are presented in Sects. 5 and 6 respectively.

2. Theory

This section describes the data model, containing propagation and instrumental effects relevant to precise amplitude calibration of millimeter-wavelength spectral-line VLBI observations.

Given the focus of the paper described in the Introduction, this discussion is confined primarily to the case of the VLBA1 operating at observing frequencies of 43 GHz (λ = 7 mm) and 86 GHz (λ = 3 mm). However, these techniques are broadly applicable to spectral-line VLBI observations at millimeter wavelengths in general. Implicit to this discussion are the instrumental parameters applicable to the VLBA; these are summarized in Table 1, individually referenced as indicated from Romney (2010) or Napier (1995). For each of the two observing bands considered here, the table contains columns summarizing the receiver band frequency limits, adopted center frequency, typical zenith system equivalent flux density (SEFD), primary beam angular full-width half-maximum θb, typical root-mean-square (rms) pointing error σp, beam squint separation △ s, and the typical baseband bandwidth assigned to an individual maser transition at these observing frequencies. The beam squint results from the offset Cassegrain optics adopted in the VLBA antenna design (Napier 1995). We note also that each of these VLBA bands is dual polarization, with nominal orthogonal RCP and LCP polarization receptors.

VLBA system parameters at millimeter wavelengths.

2.1. Data model

The data model includes all propagation and instrumental calibration effects in the signal path from the frame of the astronomical source to the correlator output. Kemball et al. (1995) present a signal-path analysis of this type for spectral line polarization VLBI in general. We extend this formalism here to include a more detailed assessment of the problem of amplitude calibration for millimeter observing wavelengths in the case of low, but non-zero, Stokes V. For brevity, we use the same notation as the original paper by Kemball et al. (1995) wherever possible, and enumerate only the data model differences here. These are presented in the same approximate sequential order in which they appear in the signal path.

Kemball et al. (1995) presented a reduction heuristic for spectral line polarization VLBI observations for the case where no prior assumption can be made concerning the magnitude of Stokes V. In contrast for example, in continuum VLBI polarimetry of compact, extra-galactic sources, the approximation Stokes V ~ 0 can be applied during data reduction to a relatively high degree of accuracy. The approach described by Kemball et al. (1995) defines a data model and develops a full calibration solution in amplitude, phase, group delay, and fringe rate for a reference receptor polarization p ∈ {R,L} using standard single-polarization VLBI techniques; and then defines a method to tie that solution to the calibration solution for the orthogonal receptor polarization q by solving for and applying differential polarization offsets in amplitude, phase, and group delay. We retain that methodology here, but focus specifically on total and differential polarization amplitude calibration, and its role in precise Stokes V measurement at millimeter wavelengths. This discussion includes a deeper examination of the data model for autocorrelation data specifically, given their relevance to amplitude calibration for spectral line VLBI observations as approached here.

2.2. General

We carry over several general assumptions made in Kemball et al. (1995) to the current analysis. Given the small angular size of astrophysical maser regions observed with VLBI and the millimeter observing wavelengths considered here, the interferometric image formation problem is in the narrow-field regime. No correction is required for the non-coplanar baselines effect in image formation, and all image-plane calibration effects can be treated as visibility-plane calibration effects. All calibration terms are factorized accordingly as antenna-based. We adopt a dual-circular orthogonal polarization basis ((p,q) ∈ {R,L}), in keeping with our instrumental focus on the VLBA.

2.3. Atmosphere

Ionospheric Faraday rotation (IFR) produces a differential polarization phase offset

,

where ν is the observing frequency. Using a maximum daytime IFR estimated

in Thompson et al. (2001) from Evans & Hagfors (1968) to be 15 rotations at

ν = 100 MHz for a line-of-sight at a zenith angle

z = 60°, we predict approximate IFR values of

γR−L ~ 0.03° and

γR−L ~ 0.007° at 43 GHz

and 86 GHz respectively, consistent with intuitive expectations. This effect can therefore

be ignored in the current analysis:

γR−L ≪ 1°.

,

where ν is the observing frequency. Using a maximum daytime IFR estimated

in Thompson et al. (2001) from Evans & Hagfors (1968) to be 15 rotations at

ν = 100 MHz for a line-of-sight at a zenith angle

z = 60°, we predict approximate IFR values of

γR−L ~ 0.03° and

γR−L ~ 0.007° at 43 GHz

and 86 GHz respectively, consistent with intuitive expectations. This effect can therefore

be ignored in the current analysis:

γR−L ≪ 1°.

The troposphere is non-dispersive and produces no differential polarization calibration offsets in any of the calibration quantities. However, the time-variable water vapor and dry atmosphere constituents are major contributors to absorption in the millimeter-wavelength bands considered here. We regard the atmosphere as isothermal, with temperature Tatm. For an atmospheric line of sight of optical depth τ, the noise power contribution from the isothermal atmosphere is (1 − e−τ) Tatm.

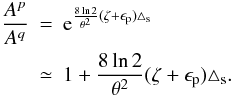

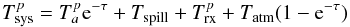

2.4. Image-plane effects

As noted above, the narrow-field constraint applicable in this case (and in most standard VLBI observations) allows relevant image-plane effects to be factorized as antenna-based corrections in the visibility plane. This does not detract from the origin of these effects in the image plane however. For the observing wavelengths and specific instrumental emphasis considered here, the most important image-plane effects originate from antenna pointing errors. These pointing errors change the region of the antenna primary beam located toward the angular direction of the correlated field center. This causes variation in the calibration terms that vary with angular separation from the optical center of the antenna primary beam, such as the amplitude and polarization response.

The nominal pointing performance and beam squint of the VLBA antennas at these observing

wavelengths are summarized in Table 1. In the

presence of pointing errors, the VLBA primary beam squint (△ s ~ 5% of

θ) introduces a differential polarization amplitude error. This problem

can be analyzed in one dimension without loss of generality. We model the one-dimensional

normalized primary beam power pattern at each antenna along angular axis

ζ as a Gaussian function of width θ, beam squint

△ s, and pointing error ϵp, for nominal

orthogonal receptor polarizations (p,q) ∈ {R,L} as:

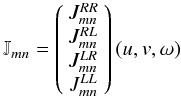

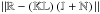

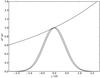

The

differential polarization amplitude error in this model takes the form:

The

differential polarization amplitude error in this model takes the form:  (3)The

R/L amplitude ratio at the nominal

pointing position ζ = 0 is plotted as a function of pointing error

ϵp in Fig. 1, for beam

squint

(3)The

R/L amplitude ratio at the nominal

pointing position ζ = 0 is plotted as a function of pointing error

ϵp in Fig. 1, for beam

squint  , as

applicable to the VLBA.

, as

applicable to the VLBA.

|

Fig. 1 Plot of normalized primary beam patterns in 1-d cross-section for receptor

polarizations {R,L} with a beam squint equal to 5% of the

full-width at half-maximum θb; the

x-ordinate for the beam pattern plot is in units of

θb. The ratio of the two beam

patterns is also plotted in the upper part of the diagram as a function of pointing

error ϵp, with x-ordinate

|

This effect is clearly significant for the representative pointing rms values enumerated in Table 1 for the VLBA operating at these observing wavelengths. We discuss calibration methods for this effect in the second half of this paper.

The net instrumental polarization response at each antenna in each nominal circular receptor polarization (p,q) ∈ {R,L} can be parametrized in terms of the net receptor ellipticity and orientation or equivalently as a complex D-term representing the net leakage of unwanted signal from the orthogonal nominal polarization (Conway & Kronberg 1969). The net instrumental polarization response contains contributions from the antenna optics design, feed illumination function, polarizer performance, and to a lesser extent, other electronic components in the downstream signal path that have a differential polarization response. The net instrumental polarization is an image-plane (direction-dependent) effect but, in the current narrow-field scientific application, we again factorize it as an antenna-based visibility plane correction factor, in common with the other image-plane calibration effects considered in this section. Pointing errors introduce time-variability in the net instrumental polarization response, expressed as an antenna-based visibility plane correction, by sampling different regions of the primary beam polarization pattern, a contributor to the net D-term. The associated dependence on frequency is neglected here due to the small fractional bandwidth.

2.5. Total power

Total power relationships for single-dish telescopes are discussed by Kutner & Ulich (1981), Downes (1989), and Wilson et al.

(2009). Adapting this references, we represent the total system temperature at an

individual antenna in nominal receptor polarization p in the form:

where

where

is the amplitude loss for an

angular pointing error ϵp, the term

is the amplitude loss for an

angular pointing error ϵp, the term

is the source

Rayleigh-Jeans brightness temperature (radiation temperature) in receptor polarization

p, ηl includes antenna scattering and

antenna resistive (ohmic) losses,

τ = τ(z) is the optical depth along

the line of sight at zenith angle z through the atmosphere,

Tspill is the mean ground spill-over temperature,

is the source

Rayleigh-Jeans brightness temperature (radiation temperature) in receptor polarization

p, ηl includes antenna scattering and

antenna resistive (ohmic) losses,

τ = τ(z) is the optical depth along

the line of sight at zenith angle z through the atmosphere,

Tspill is the mean ground spill-over temperature,

is the net

receiver temperature in receptor polarization p, and

Tatm is the mean temperature of the isothermal atmosphere

along the line of sight.

is the net

receiver temperature in receptor polarization p, and

Tatm is the mean temperature of the isothermal atmosphere

along the line of sight.

2.6. Autocorrelation and cross-power spectra

Autocorrelation and cross-power spectra are formed by interferometric correlation of all

polarization pairs for the voltages recorded in each nominal receptor polarization at each

antenna in the array. We assume idealized analog correlation here for clarity but without

loss of generality – the effects of quantization, sampling, and other digital signal

processing effects are considered in subsequent sections. Following the notation of Kemball et al. (1995), we denote the normalized

autocorrelation and cross-power spectra as

and

and

respectively

for antenna indices (m,n) and nominal receptor polarizations

(p,q). The spectra are normalized by the geometric mean of the total

power in the signal received at each antenna (m,n) forming part of the

correlation pair.

respectively

for antenna indices (m,n) and nominal receptor polarizations

(p,q). The spectra are normalized by the geometric mean of the total

power in the signal received at each antenna (m,n) forming part of the

correlation pair.

In this section we express the data model for

and

and

in the more

modern measurement equation (ME) matrix formalism introduced by Hamaker et al. (1996) and Sault et al.

(1996).

in the more

modern measurement equation (ME) matrix formalism introduced by Hamaker et al. (1996) and Sault et al.

(1996).

2.6.1. Autocorrelation data model

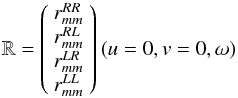

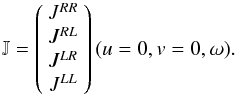

We denote the normalized analog autocorrelation spectrum as a 4-vector

; this is

real-valued for polarization p = q and complex for

p ≠ q.

; this is

real-valued for polarization p = q and complex for

p ≠ q.

(6)where

(u,v) are visibility-plane coordinates and ω denotes

angular frequency. We denote the true source correlation spectrum as J. In the

autocorrelation case, this is the (antenna-independent) source total-power spectrum,

(6)where

(u,v) are visibility-plane coordinates and ω denotes

angular frequency. We denote the true source correlation spectrum as J. In the

autocorrelation case, this is the (antenna-independent) source total-power spectrum,

(7)We denote a

total-power noise term contribution

(7)We denote a

total-power noise term contribution  ,

where

,

where  . Following Kemball et al. (1995), we use

. Following Kemball et al. (1995), we use

to denote

the point-source sensitivity (in Jy/K) of antenna m in receptor

polarization p. The total system temperature at antenna

m in polarization p is denoted as

to denote

the point-source sensitivity (in Jy/K) of antenna m in receptor

polarization p. The total system temperature at antenna

m in polarization p is denoted as

and

follows Eq. (5).

and

follows Eq. (5).

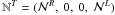

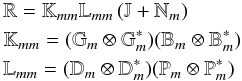

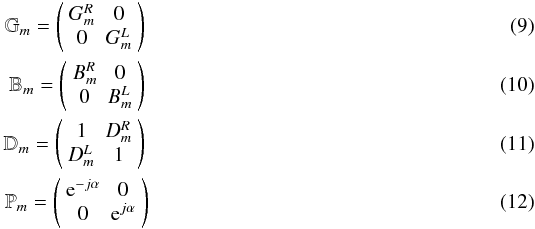

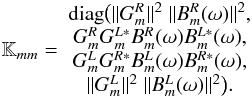

The autocorrelation data model can then be represented in matrix form as,  (8)where

⊗ denotes an outer matrix product, and

Gm,Bm,Dm

and Pm are 2 × 2 Jones matrices denoting gain normalization,

complex bandpass response, instrumental polarization, and parallactic angle feed

rotation respectively. This follows the measurement equation formalism of Hamaker et al. (1996) but includes a self-noise term,

as required in the autocorrelation data model considered here. In this

circularly-polarized basis, the Jones matrices take the form,

(8)where

⊗ denotes an outer matrix product, and

Gm,Bm,Dm

and Pm are 2 × 2 Jones matrices denoting gain normalization,

complex bandpass response, instrumental polarization, and parallactic angle feed

rotation respectively. This follows the measurement equation formalism of Hamaker et al. (1996) but includes a self-noise term,

as required in the autocorrelation data model considered here. In this

circularly-polarized basis, the Jones matrices take the form,  Kmm

is a therefore a diagonal 4 × 4 matrix containing the gain normalization

Kmm

is a therefore a diagonal 4 × 4 matrix containing the gain normalization

and complex

bandpass response terms

and complex

bandpass response terms  ,

,  (13)The

net instrumental polarization response Lmm including D-terms

and parallactic angle rotation is the 4 × 4 matrix,

(13)The

net instrumental polarization response Lmm including D-terms

and parallactic angle rotation is the 4 × 4 matrix,  (14)

(14)

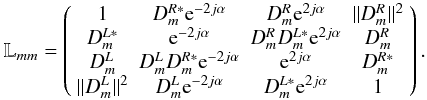

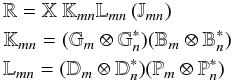

2.6.2. Cross-correlation data model

The cross-correlation data model does not include a self-noise term; in this case

Eq. (8) takes the form,  (15)where

X is a diagonal 4 × 4 matrix term for cross-correlation coherence losses; this term does

not apply to autocorrelation data. X does not contribute to differential polarization

amplitude offsets, and forms part of the calibration of the absolute flux density scale.

(15)where

X is a diagonal 4 × 4 matrix term for cross-correlation coherence losses; this term does

not apply to autocorrelation data. X does not contribute to differential polarization

amplitude offsets, and forms part of the calibration of the absolute flux density scale.

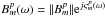

Here, Jmn is the true source visibility cross-power

spectrum,  (16)as a function of

(u,v)-spacing and frequency ω.

(16)as a function of

(u,v)-spacing and frequency ω.

2.7. Sampling and quantization

The voltages in each nominal receptor polarization are digitally sampled and quantized by

the data acquisition sub-systems at each antenna. Digital realizations

of the

total-power and cross-power spectra are obtained by subsequent cross-correlation. We

denote the relationship between the measured spectra

of the

total-power and cross-power spectra are obtained by subsequent cross-correlation. We

denote the relationship between the measured spectra

and their

true analog counterparts

and their

true analog counterparts  used in

earlier sections as a general transformation function

fd:

used in

earlier sections as a general transformation function

fd:  The

form of this relationship depends on quantization level, sampler voltage threshold

stability and accuracy, and correlator architecture, and is reviewed by Thompson et al. (2001) and references therein. This

transformation function does not always take closed analytic form.

The

form of this relationship depends on quantization level, sampler voltage threshold

stability and accuracy, and correlator architecture, and is reviewed by Thompson et al. (2001) and references therein. This

transformation function does not always take closed analytic form.

The specific case of sampling and quantization effects for the VLBA correlator is considered by Kogan (1998). This correlator has an FX architecture, originally hardware-based but more recently upgraded to a VLBA-DiFX software implementation (Deller et al. 2007). Both one- and two-bit sampling are supported. An offset in sampler threshold voltage can produce an associated amplitude error in the output VLBA correlator spectra (Kogan 1998), particularly for two-bit sampling. If the mapping of individual sampler modules to sets of baseband converters mirrors receptor polarization baseband assignment – as occurs naturally for several common baseband converter configurations – these amplitude offsets will translate to differential polarization amplitude errors. The correction of quantization and sampler threshold errors is discussed in further detail in the following section.

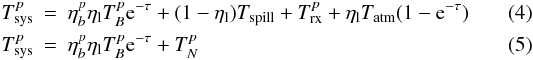

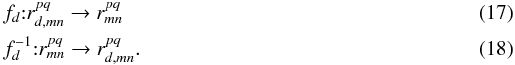

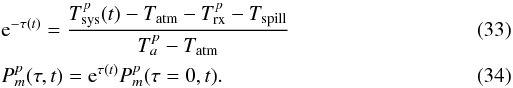

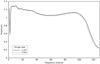

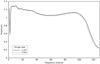

3. Data reduction methods

In this section we assess the data reduction methods used to measure and correct the instrumental and propagation terms in the data model enumerated in Sect. 2. Consistent with earlier practice, we describe here only differences with the data reduction methodology presented by Kemball et al. (1995) and use identical notation wherever possible. This section follows the proposed data reduction sequence, which is shown in flowchart form in Fig. 2.

We have implemented these algorithms within a development framework that brings together several large community codes used for radio-astronomical imaging (Kemball et al. 2008). For consistency with earlier algorithmic work in Kemball et al. (1995) we have primarily used an adapted implementation of the Astronomical Image Processing System2 within this software framework for the current work. Our intention is to make these revisions publicly available in the future.

|

Fig. 2 Flowchart depicting the overall data reduction sequence described in Sect. 3. |

3.1. Sampling and quantization

In this section, we review the correction of digital sampling and quantization effects in VLBI circular polarimetry at millimeter wavelengths. We do not find it necessary to revise existing algorithmic practice, as described in the analysis below.

The total-power and cross-power spectra  from the

VLBA FX correlator are first corrected for quantization effects and then scaled in

amplitude by polarization-independent factors known a-priori for the array (the latter

known historically as b-factors). The quantization correction element of the

transformation function fd defined in

Sect. 2.7 above is defined as a relation for each quantization mode (one- or two-bit,

ηQ = 11 or

ηQ = 22 respectively) between a measured

correlation ρm and the true underlying

correlation ρ, both defined in the conjugate Fourier delay lag domain. In

lag space, the correlation is of order

from the

VLBA FX correlator are first corrected for quantization effects and then scaled in

amplitude by polarization-independent factors known a-priori for the array (the latter

known historically as b-factors). The quantization correction element of the

transformation function fd defined in

Sect. 2.7 above is defined as a relation for each quantization mode (one- or two-bit,

ηQ = 11 or

ηQ = 22 respectively) between a measured

correlation ρm and the true underlying

correlation ρ, both defined in the conjugate Fourier delay lag domain. In

lag space, the correlation is of order  for cross-power spectra; for the VLBA system temperatures listed in Table 1 and for typical SiO maser spectral flux densities,

lag-domain correlation values are small

|ρm| ≲ 0.1. In this case, the relation

between ρm and ρ is in the

highly linear regime (Kogan 1998) and the

quantization correction can be applied as a direct linear scaling of cross-power spectral

values

for cross-power spectra; for the VLBA system temperatures listed in Table 1 and for typical SiO maser spectral flux densities,

lag-domain correlation values are small

|ρm| ≲ 0.1. In this case, the relation

between ρm and ρ is in the

highly linear regime (Kogan 1998) and the

quantization correction can be applied as a direct linear scaling of cross-power spectral

values  with numerical

coefficient αQ (Kogan 1993a). As this takes the form of a linear,

polarization-independent correction, it cannot produce an artificial instrumental

signature mimicking Stokes V. Cross-polarized autocorrelation spectra

with numerical

coefficient αQ (Kogan 1993a). As this takes the form of a linear,

polarization-independent correction, it cannot produce an artificial instrumental

signature mimicking Stokes V. Cross-polarized autocorrelation spectra

have

lag domain correlation values of order

have

lag domain correlation values of order  ,

as indicated by the first-order form of Eq. (8), and similarly fall in the low-correlation regime. Accordingly they have the

same quantization scaling correction as cross-power spectra.

,

as indicated by the first-order form of Eq. (8), and similarly fall in the low-correlation regime. Accordingly they have the

same quantization scaling correction as cross-power spectra.

Parallel-hand autocorrelation spectra  have lag-domain correlation

values of unity at zero delay, and require Fourier transformation to and from the lag

domain to allow application of the full non-linear correction between

ρm and ρ (Kogan 1993a). As a result, this does not reduce to a

linear scaling relationship for the total-power spectra

have lag-domain correlation

values of unity at zero delay, and require Fourier transformation to and from the lag

domain to allow application of the full non-linear correction between

ρm and ρ (Kogan 1993a). As a result, this does not reduce to a

linear scaling relationship for the total-power spectra

in the

frequency domain. Two effects limit the accuracy of the inverse transform to the lag

domain. The VLBA FX correlator records only positive spectral channels (Kogan 1993a), omitting the opposite sideband which

contains digitization noise (Thompson et al. 2001).

In addition, an FX correlator requires equal-length zero padding to reconstruct the

associated correlation function over the full range of sampled delay lags (Granlund 1986; Thompson

et al. 2001).

in the

frequency domain. Two effects limit the accuracy of the inverse transform to the lag

domain. The VLBA FX correlator records only positive spectral channels (Kogan 1993a), omitting the opposite sideband which

contains digitization noise (Thompson et al. 2001).

In addition, an FX correlator requires equal-length zero padding to reconstruct the

associated correlation function over the full range of sampled delay lags (Granlund 1986; Thompson

et al. 2001).

Sampler threshold voltages define transition points between discrete quantization states. The non-linear mapping between ρm and ρ depends functionally on the value of the sampler threshold voltages relative to their optimal values (Kogan 1995). For two-bit sampling in the low-correlation limit, the relative error in FX spectral output depends linearly on the deviation in threshold voltage level. In one-bit sampling, the relative error in spectral output depends only in second order on the error in the threshold clipping voltage (Kogan 1995). In both VLBA quantization modes, the correction in output spectral amplitude can be derived from the measured mean deviation of the total-power spectra from the unit mean power level predicted for an ideal digitizer, independent of spectral shape (Kogan 1995), and we adopt that approach here.

The autocorrelation data are used in integrated template-fitting as part of calibration, as described in further detail below.

3.2. Bandpass calibration

Following Kemball et al. (1995), and the Jones

matrix formalism in Eq. (10) in the current

work, we denote the cross-power complex bandpass response as

; this is expanded as

; this is expanded as

.

The autocorrelation bandpass amplitude response, denoted

.

The autocorrelation bandpass amplitude response, denoted

, differs from the cross-power

bandpass amplitude response

, differs from the cross-power

bandpass amplitude response  however, due to an unavoidable

level of irreducible aliasing in the net system bandpass response. As the continuum

calibrators have flat spectra across the baseband bandwidth they are used to solve for

however, due to an unavoidable

level of irreducible aliasing in the net system bandpass response. As the continuum

calibrators have flat spectra across the baseband bandwidth they are used to solve for

and

and

using cross- and total-power

continuum calibrator data respectively.

using cross- and total-power

continuum calibrator data respectively.

3.2.1. Bandpass frequency frame

The VLBA correlator produces output cross- and total-power spectra in a geocentric

J2000.0 coordinate reference frame. In contrast, the bandpass response function

is defined in the data

acquisition coordinate reference frame at each antenna, which is an apparent topocentric

frame. These two frequency frames are offset by the time-variable natural geometric

fringe rate at antenna m, denoted

△ ωm(t). The angular

frequency of channel number l in the recorded cross- and total-power

visibility spectra (which are in a geocentric frame) is denoted as

ωl. The autocorrelation bandpass amplitude response

is defined in the data

acquisition coordinate reference frame at each antenna, which is an apparent topocentric

frame. These two frequency frames are offset by the time-variable natural geometric

fringe rate at antenna m, denoted

△ ωm(t). The angular

frequency of channel number l in the recorded cross- and total-power

visibility spectra (which are in a geocentric frame) is denoted as

ωl. The autocorrelation bandpass amplitude response

at

antenna m in receptor polarization

p ∈ {R,L} can be solved for by minimizing:

at

antenna m in receptor polarization

p ∈ {R,L} can be solved for by minimizing:

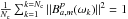

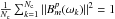

![\begin{eqnarray} \label{bp-ac}\left[\chi^{pp}_m\right]^2 & = &\sum_{k=1}^{N_t}\sum_{l=1}^{N_{\rm c}}\left[\|B_{a,m}^p(\omega_{\rm l}-\triangle \omega_m(t_k))\|^2 - \tilde{V}_{mm}^{pp}\right]^2 \\ \tilde{V}_{mm}^{pp} & = & \|V_{mm}^{pp}(\omega_{\rm l},t_k)\|/\overline{\|V_{mm}^{pp}(\omega_{\rm l},t_k)\|} \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2011/09/aa17337-11/aa17337-11-eq129.png) where

where

is the (real-valued)

continuum calibrator total-power spectrum in parallel-hand polarization correlation

pp at antenna m over a pre-average integration

interval centered at time tk, the number of

frequency channels is Nc, and the number of integration

intervals is Nt. The pre-average interval

is fixed and short relative to

is the (real-valued)

continuum calibrator total-power spectrum in parallel-hand polarization correlation

pp at antenna m over a pre-average integration

interval centered at time tk, the number of

frequency channels is Nc, and the number of integration

intervals is Nt. The pre-average interval

is fixed and short relative to  .

Pre-averaging improves the statistical robustness of the bandpass response solver, as

this is a least-squares minimization problem. The autoscaling of each total-power

spectrum by the instantaneous mean spectral amplitude,

.

Pre-averaging improves the statistical robustness of the bandpass response solver, as

this is a least-squares minimization problem. The autoscaling of each total-power

spectrum by the instantaneous mean spectral amplitude,

,

ensures that the spectra do not need to be calibrated in amplitude before solving for

,

ensures that the spectra do not need to be calibrated in amplitude before solving for

. The resulting solution for

. The resulting solution for

is normalized to unit mean

power

is normalized to unit mean

power  .

.

Bandpass calibration forms part of visibility amplitude calibration and accurate

estimation of Stokes V requires a correspondingly accurate solution for

. For example, a spurious

bandpass amplitude spike, even if in an off-source spectral region, will bias the mean

amplitude normalization of the bandpass over the region of source emission.

. For example, a spurious

bandpass amplitude spike, even if in an off-source spectral region, will bias the mean

amplitude normalization of the bandpass over the region of source emission.

The measured visibility spectra and the unknown bandpass response are not in a common

frequency frame; the channel shift corresponding to

△ ωm is a non-negligible effect at the

wavelengths of λ = 3 mm and λ = 7 mm considered in

this paper. If  is parametrized discretely

as a set of unknown values at each frequency channel (in a stationary topocentric frame)

then this can be estimated by direct integration of the total-power, parallel-hand

spectra if they are first shifted to the stationary reference frame by using a discrete

Fourier transform pair including a channel shift. Alternatively, the unshifted

visibility spectra can be fit directly if

is parametrized discretely

as a set of unknown values at each frequency channel (in a stationary topocentric frame)

then this can be estimated by direct integration of the total-power, parallel-hand

spectra if they are first shifted to the stationary reference frame by using a discrete

Fourier transform pair including a channel shift. Alternatively, the unshifted

visibility spectra can be fit directly if  is parametrized as a

polynomial series expansion over frequency; this parametrization allows continuous

variation of △ ωm(t) in

the formulation of the chi-square minimization problem. This method was developed by

Kemball & Diamond (1997), using a

Chebyshev polynomial expansion for the bandpass response. The polynomial bandpass method

avoids digital signal processing artifacts associated with the Fourier transform shift.

In addition, as the polynomial expansion order can be significantly lower than the

number of frequency channels Nc, this approach reduces the

number of free parameters over the discrete parametrization case, thus improving the

signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of the bandpass solution. For these reasons (amongst others

discussed below), we adopt the bandpass polynomial solution method. In a Chebyshev

expansion, the autocorrelation bandpass response takes the form:

is parametrized as a

polynomial series expansion over frequency; this parametrization allows continuous

variation of △ ωm(t) in

the formulation of the chi-square minimization problem. This method was developed by

Kemball & Diamond (1997), using a

Chebyshev polynomial expansion for the bandpass response. The polynomial bandpass method

avoids digital signal processing artifacts associated with the Fourier transform shift.

In addition, as the polynomial expansion order can be significantly lower than the

number of frequency channels Nc, this approach reduces the

number of free parameters over the discrete parametrization case, thus improving the

signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of the bandpass solution. For these reasons (amongst others

discussed below), we adopt the bandpass polynomial solution method. In a Chebyshev

expansion, the autocorrelation bandpass response takes the form:

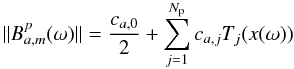

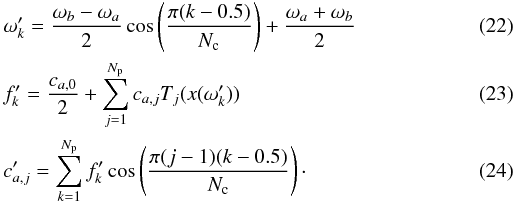

(21)where

Tj(x) is the Chebyshev

polynomial of degree j (Press et al.

2007), ca,j are real coefficients

in the series expansion for the autocorrelation bandpass amplitude, and the transformed

coordinate is

x(ω) = (2ω − ωa − ωb)/(ωb − ωa).

The topocentric channel range for the bandpass solution covered by the measured

visibility spectra is

[ωa = 1 − max(△ ωm), ωb = Nc − min(△ ωm)] .

In the current work, we found it important to fit over the full topocentric range

[ωa,ωb]

as opposed to only [1,Nc] as used in

past practice, so that there is the greatest possible chi-square constraint on the

bandpass solution at the edge of the frequency channel range. The derived solution

coefficients ca,j resulting from the

chi-square minimization over

[ωa,ωb]

are then transformed to

(21)where

Tj(x) is the Chebyshev

polynomial of degree j (Press et al.

2007), ca,j are real coefficients

in the series expansion for the autocorrelation bandpass amplitude, and the transformed

coordinate is

x(ω) = (2ω − ωa − ωb)/(ωb − ωa).

The topocentric channel range for the bandpass solution covered by the measured

visibility spectra is

[ωa = 1 − max(△ ωm), ωb = Nc − min(△ ωm)] .

In the current work, we found it important to fit over the full topocentric range

[ωa,ωb]

as opposed to only [1,Nc] as used in

past practice, so that there is the greatest possible chi-square constraint on the

bandpass solution at the edge of the frequency channel range. The derived solution

coefficients ca,j resulting from the

chi-square minimization over

[ωa,ωb]

are then transformed to  over

[1,Nc] as (Press et al. 2007),

over

[1,Nc] as (Press et al. 2007),  During

this coefficient transformation, if

ωb < Nc

or ωa > 1 then the

outer

During

this coefficient transformation, if

ωb < Nc

or ωa > 1 then the

outer  are

extrapolated horizontally to cover the complete range

[1,Nc] .

are

extrapolated horizontally to cover the complete range

[1,Nc] .

We note that Eq. (19) is formulated for the case of a time-invariant bandpass at each antenna. This is an appropriate instrumental assumption given the expected stability of the net VLBA frequency response, and improves the signal-to-noise ratio of the resulting bandpass solution. In addition a single bandpass solution provides greater control over the calibration of overall differential polarization R/L amplitude and phase offsets.

In the most direct formulation, the cross-power bandpass response

can be solved for from the

parallel-hand continuum calibrator cross-power spectra

can be solved for from the

parallel-hand continuum calibrator cross-power spectra

by an

analogous formulation of Eq. (19),

by an

analogous formulation of Eq. (19),

![\begin{eqnarray} \left[\chi^{pp}\right]^2 & = & \sum_{m,n>m}^{N_a}\sum_{k=1}^{N_t}\sum_{l=1}^{N_{\rm c}}\left\| B_{m}^p(\omega_{lm})B_{n}^{p*}(\omega_{ln}) -{\tilde{V}^{pp}_{mn}}\right\|^2 \label{bp-xc}\\ \tilde{V}^{pp}_{mn}&=& V_{mn}^{pp}(\omega_{\rm l},t_k)\ /\ {\overline{V_{mn}^{pp}(\omega_{\rm l},t_k)}}\nonumber\\ \omega_{lm} & = & \omega_{\rm l}-\triangle \omega_m(t_k) \nonumber \\ \omega_{ln} & = & \omega_{\rm l}-\triangle \omega_n(t_k) \nonumber \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2011/09/aa17337-11/aa17337-11-eq155.png) (25)where

(25)where

is the complex normalization factor to auto-scale the cross-power spectrum in

integration tk over frequency to unit mean

amplitude and zero mean phase. The auto-scaling applied during the chi-square

minimization removes the requirement for amplitude calibration of

is the complex normalization factor to auto-scale the cross-power spectrum in

integration tk over frequency to unit mean

amplitude and zero mean phase. The auto-scaling applied during the chi-square

minimization removes the requirement for amplitude calibration of

, as in the case for the

autocorrelation bandpass

, as in the case for the

autocorrelation bandpass  , but for the cross-power

bandpass solution, the visibility data need to be calibrated in the phase domain for

residual group delay, fringe-rate, phase, and differential polarization phase offset, as

described by Kemball et al. (1995). The resulting

solutions for

, but for the cross-power

bandpass solution, the visibility data need to be calibrated in the phase domain for

residual group delay, fringe-rate, phase, and differential polarization phase offset, as

described by Kemball et al. (1995). The resulting

solutions for  are normalized over

frequency to unit mean power

are normalized over

frequency to unit mean power  and zero mean phase. The

polynomial bandpass method is further favored in the cross-power case as there is no

unique shift defined for

Vmn(tk)

if instead of a polynomial bandpass expansion, the visibility data are shifted using a

Fourier transform.

and zero mean phase. The

polynomial bandpass method is further favored in the cross-power case as there is no

unique shift defined for

Vmn(tk)

if instead of a polynomial bandpass expansion, the visibility data are shifted using a

Fourier transform.

3.2.2. Bandpass aliasing correction

The solutions obtained for the cross-power bandpass response

from the direct formulation

in Eq. (25) are not optimal however for

precise amplitude calibration at the millimeter wavelengths (λ = 3 mm

and λ = 7 mm) considered here. At these wavelengths, the amplitude of

the continuum calibrator cross-power spectra on the longer baselines invariably have

insufficient SNR to allow estimation of

from the direct formulation

in Eq. (25) are not optimal however for

precise amplitude calibration at the millimeter wavelengths (λ = 3 mm

and λ = 7 mm) considered here. At these wavelengths, the amplitude of

the continuum calibrator cross-power spectra on the longer baselines invariably have

insufficient SNR to allow estimation of  with low mean-square error

(MSE) at the outlying antennas. The autocorrelation spectra have significantly higher

SNR however, and offer a preferred path for the solution of the cross-power bandpass

amplitude response

with low mean-square error

(MSE) at the outlying antennas. The autocorrelation spectra have significantly higher

SNR however, and offer a preferred path for the solution of the cross-power bandpass

amplitude response  if corrected for aliasing, as

found necessary in the current work. We adopt an aliasing model:

if corrected for aliasing, as

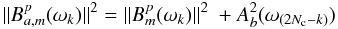

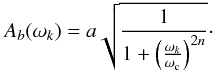

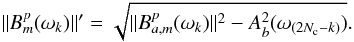

found necessary in the current work. We adopt an aliasing model:  (26)where

Ab(ω) is a model for the

cross-power bandpass amplitude response at and above the upper end of the band (in a

frequency range

ωk0 > βωc,

where ωc is the bandpass cutoff frequency and

β lies in the approximate range

β ~ {0.7−0.9}). This function can be extrapolated and folded to

approximate the aliased autocorrelation response. We find a 12-node Butterworth function

(Bianchi & Sorrentino 2007) to give a

satisfactory empirical fit to the upper-bandpass region

ωk0 > βωc,

with little sensitivity to the value of β adopted to define the channel

range of the fit:

(26)where

Ab(ω) is a model for the

cross-power bandpass amplitude response at and above the upper end of the band (in a

frequency range

ωk0 > βωc,

where ωc is the bandpass cutoff frequency and

β lies in the approximate range

β ~ {0.7−0.9}). This function can be extrapolated and folded to

approximate the aliased autocorrelation response. We find a 12-node Butterworth function

(Bianchi & Sorrentino 2007) to give a

satisfactory empirical fit to the upper-bandpass region

ωk0 > βωc,

with little sensitivity to the value of β adopted to define the channel

range of the fit:  (27)The fit minimizes:

(27)The fit minimizes:

![\begin{eqnarray} [\chi^{pp}]^2&=&\sum_{k=k0}^{N_{\rm c}}\left[\|B_m^p(\omega_k)\|^2-\left(A_m^p(\omega_k)\right)^2\right]^2\nonumber\\ &&+ \sum_{k=k0}^{N_{\rm c}-1}[\|B_{a,m}^p(\omega_k)\|^2-\|B_m^p(\omega_k)\|^2\nonumber\\ &&\mbox{}- \left(A_m^p(\omega_{(2N_{\rm c}-k)})\right)^2]^2 \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2011/09/aa17337-11/aa17337-11-eq167.png) (28)where

the number of nodes is fixed at n = 12, and factor a

and the cutoff frequency ωc are the only fitted parameters.

The direct cross-power solutions for

(28)where

the number of nodes is fixed at n = 12, and factor a

and the cutoff frequency ωc are the only fitted parameters.

The direct cross-power solutions for  obtained from Eq. (25) do however have sufficient SNR to allow

a solution for Ab(ω) in

Butterworth form (27). The solution for

Ab(ω) allows the

high-SNR autocorrelation bandpass amplitude solutions

obtained from Eq. (25) do however have sufficient SNR to allow

a solution for Ab(ω) in

Butterworth form (27). The solution for

Ab(ω) allows the

high-SNR autocorrelation bandpass amplitude solutions

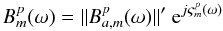

to be then transformed to

cross-power form:

to be then transformed to

cross-power form:  (29)In this hybrid

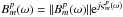

approach, the phase

(29)In this hybrid

approach, the phase  of the cross-power bandpass

response is solved for by minimizing the phase-only analog of Eq. (25):

of the cross-power bandpass

response is solved for by minimizing the phase-only analog of Eq. (25): ![\begin{eqnarray} \left[\chi^{pp}\right]^2 &=&\sum_{m,n>m}^{N_a}\sum_{k=1}^{N_t}\sum_{l=1}^{N_{\rm c}}\big[ \varsigma_{m}^p(\omega_{\rm l}-\triangle \omega_m(t_k))\nonumber\\ && \mbox{} - \varsigma_n^p(\omega_{\rm l}-\triangle \omega_n(t_k))-\arg(\tilde{V}_{mn}^{pp}(\omega_{\rm l},t_k))\big]^2 \label{bp-xcp} \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2011/09/aa17337-11/aa17337-11-eq172.png) (30)where

(30)where

are the pre-averaged

continuum calibrator cross-power visibility spectra, normalized to unit mean amplitude

and zero mean phase, and calibrated in delay, fringe-rate, and phase as described above.

In practice, the peak-to-peak residual phase error over frequency for the net VLBA

baseband response after correction for phase and group delay is typically of order 5

degrees, and we fit

are the pre-averaged

continuum calibrator cross-power visibility spectra, normalized to unit mean amplitude

and zero mean phase, and calibrated in delay, fringe-rate, and phase as described above.

In practice, the peak-to-peak residual phase error over frequency for the net VLBA

baseband response after correction for phase and group delay is typically of order 5

degrees, and we fit  at each antenna in each

receptor polarization with a low-order polynomial in order to maximize SNR. The complex

cross-power bandpass response

at each antenna in each

receptor polarization with a low-order polynomial in order to maximize SNR. The complex

cross-power bandpass response  is therefore represented by

a separate Chebyshev polynomial in each of amplitude and phase, with a lower-order

polynomial in phase compared to that in amplitude. The final cross-power bandpass

solution is therefore constructed as,

is therefore represented by

a separate Chebyshev polynomial in each of amplitude and phase, with a lower-order

polynomial in phase compared to that in amplitude. The final cross-power bandpass

solution is therefore constructed as,

(31)applying

the unit-mean power and zero-mean phase normalization to the bandpass solutions as

described above.

(31)applying

the unit-mean power and zero-mean phase normalization to the bandpass solutions as

described above.

3.2.3. Reference antenna differential polarization bandpass phase response

We note that the solution for  is derived by solving a

self-calibration problem that is linear in baseline-based phase, and so is known only

relative to the phase at receptor polarization p for an adopted

reference antenna (subscript zero), i.e. the determined bandpass phase solution takes

the form

is derived by solving a

self-calibration problem that is linear in baseline-based phase, and so is known only

relative to the phase at receptor polarization p for an adopted

reference antenna (subscript zero), i.e. the determined bandpass phase solution takes

the form  , as opposed to

, as opposed to

, the argument of

, the argument of

in the Jones matrix of Eq. (10). A full

solution, allowing correction of cross-polarized visibility spectra therefore requires

an independent estimate of the differential polarization bandpass phase response at the

reference antenna

in the Jones matrix of Eq. (10). A full

solution, allowing correction of cross-polarized visibility spectra therefore requires

an independent estimate of the differential polarization bandpass phase response at the

reference antenna  . This

is directly analogous to the correction of parallel-hand phase solutions for

differential polarization phase and delay offsets at the reference antenna, as described

by Kemball et al. (1995). The correction for

. This

is directly analogous to the correction of parallel-hand phase solutions for

differential polarization phase and delay offsets at the reference antenna, as described

by Kemball et al. (1995). The correction for

has

not traditionally been applied to bandpass corrections in spectral-line VLBI but is

relevant to the autocorrelation polarimetry described in subsequent sections of this

paper, so was implemented in the current work. Without this correction, for example,

there would be no bandpass phase correction applied to the cross-polarized

autocorrelation spectra at the reference antenna.

has

not traditionally been applied to bandpass corrections in spectral-line VLBI but is

relevant to the autocorrelation polarimetry described in subsequent sections of this

paper, so was implemented in the current work. Without this correction, for example,

there would be no bandpass phase correction applied to the cross-polarized

autocorrelation spectra at the reference antenna.

3.2.4. Bandpass correction

The basic algebra for applying the autocorrelation bandpass response

and

and

to correct the visibility

data is described by Kemball et al. (1995) and

Diamond (1989). These references describe a

traditional

to correct the visibility

data is described by Kemball et al. (1995) and

Diamond (1989). These references describe a

traditional  heuristic for autocorrelation bandpass correction, to minimize the residual total-power

offset. However, the complete autocorrelation data model used here (Eq. (8)) does not include this term – nor is it

necessary – so we do not subtract 1 when correcting the autocorrelation bandpass

response in the current work. Additionally, during bandpass application, the fringe-rate

shift is applied when computing the polynomial expansion of

heuristic for autocorrelation bandpass correction, to minimize the residual total-power

offset. However, the complete autocorrelation data model used here (Eq. (8)) does not include this term – nor is it

necessary – so we do not subtract 1 when correcting the autocorrelation bandpass

response in the current work. Additionally, during bandpass application, the fringe-rate

shift is applied when computing the polynomial expansion of

or

or

.

.

3.3. Amplitude calibration

Amplitude calibration of the correlation spectra  in units of spectral flux

density

in units of spectral flux

density  (Jy) requires independent

measurement of the total system temperature

(Jy) requires independent

measurement of the total system temperature  (K) and

point-source sensitivity

(K) and

point-source sensitivity  (Jy

K-1) both at each antenna m and in each receptor

polarization p throughout the course of the observation. We denote the

system equivalent flux density (SEFD) as

(Jy

K-1) both at each antenna m and in each receptor

polarization p throughout the course of the observation. We denote the

system equivalent flux density (SEFD) as  (Jy). In

the formalism used in this paper (see Eq. (13) and following),

(Jy). In

the formalism used in this paper (see Eq. (13) and following),  .

The

.

The  are

time-variable due to changes in both atmospheric attenuation and antenna gravitational

deformation, both as a function of time and antenna pointing position in local horizon

coordinates.

are

time-variable due to changes in both atmospheric attenuation and antenna gravitational

deformation, both as a function of time and antenna pointing position in local horizon

coordinates.

Sections 3.3.1 and 3.3.2 contain a review and analysis of current practice in VLBI continuum and spectral-line amplitude calibration, with a specific focus on circular polarimetry at millimeter wavelengths. We describe the innovations in amplitude calibration introduced in the current work in Sect. 3.3.3.

3.3.1. Continuum amplitude calibration

The VLBA records integrated system temperatures every two minutes at each antenna in

each receptor polarization p ∈ {R,L} obtained

using an underlying switched noise calibration system (Thompson 1995). The VLBA project also publishes opacity-corrected gain curves

for each antenna, which provide  as a

polynomial function of zenith angle z; these curves are obtained from

analyses of regular single-dish service observations, separately scheduled (Walker 1999).

as a

polynomial function of zenith angle z; these curves are obtained from

analyses of regular single-dish service observations, separately scheduled (Walker 1999).

In standard a priori amplitude calibration of VLBI continuum observations, the

are computed as

are computed as

from the measured system temperature values and published antenna point-source

sensitivity curves. At the observing wavelengths λ = 7 mm and

λ = 3 mm considered in this paper the opacity-corrected

from the measured system temperature values and published antenna point-source

sensitivity curves. At the observing wavelengths λ = 7 mm and

λ = 3 mm considered in this paper the opacity-corrected

provided by the VLBA require correction for atmospheric attenuation

e−τ (Walker

1999; and see Eq. (5)). As

described by Leppänen (1993), these corrections

can be obtained by fitting the measured system temperatures over the course of the

observations as a function of zenith angle z against a simplified form

of Eq. (5):

provided by the VLBA require correction for atmospheric attenuation

e−τ (Walker

1999; and see Eq. (5)). As

described by Leppänen (1993), these corrections

can be obtained by fitting the measured system temperatures over the course of the

observations as a function of zenith angle z against a simplified form

of Eq. (5):

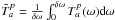

(32)where

(32)where

is the

antenna temperature contribution from the source. The number of free parameters can be

controlled by adopting a plane-parallel atmosphere, with

τ = τ0secz for zenith

opacity τ0, extrapolating Tatm

from ground-level metrology, and adopting an empirical model for the spill-over noise

contribution for VLBA antennas (Leppänen 1993).

In this case, only receiver temperature Trx and zenith

opacity τ0 remain as free parameters, and once solved for

using chi-square minimization, allow opacity correction in the form:

is the

antenna temperature contribution from the source. The number of free parameters can be

controlled by adopting a plane-parallel atmosphere, with

τ = τ0secz for zenith

opacity τ0, extrapolating Tatm

from ground-level metrology, and adopting an empirical model for the spill-over noise

contribution for VLBA antennas (Leppänen 1993).

In this case, only receiver temperature Trx and zenith

opacity τ0 remain as free parameters, and once solved for

using chi-square minimization, allow opacity correction in the form:

The

a priori amplitude calibration methods outlined above are limited in their intrinsic

accuracy by several sources of error. These include systematic errors in the measured or

adopted power level of the noise calibration sources, intrinsic statistical error in the

sampled switched Tsys measurements, and the stability over

time of hardware elements affecting amplitude calibration, including receiver gain and

the stability of the noise calibration sources. In addition, the opacity solution is

limited by the assumption of a stable, plane-parallel atmosphere; this does not hold at

low elevations or if local weather conditions vary significantly over the course of the

observations (i.e.

τ0 = τ0(t)).

Other sources of systematic error include the assumption of an isothermal

Tatm extrapolated from the measured ground air

temperature, and the relatively coarse empirical model adopted for antenna spill-over

noise contributions.

The

a priori amplitude calibration methods outlined above are limited in their intrinsic

accuracy by several sources of error. These include systematic errors in the measured or

adopted power level of the noise calibration sources, intrinsic statistical error in the

sampled switched Tsys measurements, and the stability over

time of hardware elements affecting amplitude calibration, including receiver gain and

the stability of the noise calibration sources. In addition, the opacity solution is

limited by the assumption of a stable, plane-parallel atmosphere; this does not hold at

low elevations or if local weather conditions vary significantly over the course of the

observations (i.e.

τ0 = τ0(t)).

Other sources of systematic error include the assumption of an isothermal

Tatm extrapolated from the measured ground air

temperature, and the relatively coarse empirical model adopted for antenna spill-over

noise contributions.

We estimate the overall accuracy of a priori VLBA calibration to be ~10% at λ = 7 mm and ~15% at λ = 3 mm, excluding low-elevation data.

A priori amplitude calibration, with or without opacity correction, can be refined using amplitude self-calibration. Historically, two assumptions are often made when performing amplitude self-calibration using parallel-hand visibility data: i) that Stokes V is identically zero; and ii) that amplitude calibration is completely separable from instrumental polarization calibration. The inapplicability of these assumptions when measuring non-zero fractional circular polarization mc ≲ 0.5% in compact extragalactic continuum sources is considered in detail by Homan & Wardle (1999), Homan et al. (2001), and Homan & Lister (2006). Reduction methods for spectral-line sources with non-zero mc are described by Kemball et al. (1995). As described in the latter reference, in the presence of circular polarization, independent calibration of the parallel-hand correlations rRR(u,v,ω) and rLL(u,v,ω) against a total intensity source model that assumes V = 0 will redistribute circularly-polarized emission in the image, including introducing positional offsets in the centroids of individual circularly-polarized components. As a result, Kemball et al. (1995) used only a single reference receptor polarization p ∈ {R,L} in phase-related self-calibration, and used measured R − L phase offsets to transfer solutions to the orthogonal receptor polarization. Similarly, amplitude self-calibration is avoided, for the reasons noted above.

Homan & Wardle (1999) introduced a method for calibrating continuum sources with low mc while still allowing amplitude self-calibration; their method calibrates (rRR + rLL)/2 against a common total intensity source model Imod, then solves for long-term residual differential gain errors at each antenna under the Stokes V = 0 assumption, i.e. rRR = Imod and rLL = Imod. The latter measurement of the differential polarization gain factors relies on the mean circular polarization of the observed ensemble of sources being close to zero. This approach has been demonstrated successfully at wavelengths longer than λ ≳ 1 cm (Homan et al. 2009). Simulation studies for this technique indicate a 1 − σ uncertainty in measured circular polarization of mc ~ 0.1% for source brightness values exceeding 1 Jy/beam (Homan & Lister 2006). Uncertainties in amplitude gain calibration predominate over D-term errors or thermal noise contributions in this method (Homan & Lister 2006).

The coupling of amplitude and instrumental polarization is evident in the form of Eq. (15), which contains both G and D terms. Neglecting this coupling is equivalent to linearization of Eq. (15), which truncates terms that include instrumental polarization D-terms from the parallel-hand equations (Roberts et al. 1994; Homan & Wardle 1999). This can be addressed by an iterative approach to amplitude and polarization calibration (Homan & Wardle 1999) but with a modest impact on the derived location and magnitude of circularly-polarized components (Homan & Lister 2006).

3.3.2. Spectral-line amplitude calibration

The template-fitting method derives amplitude calibration from parallel-hand

autocorrelation spectra, and was first introduced by Reid et al. (1980). The source total power spectrum usually has far greater

frequency structure than the continuum noise terms in Eq. (5), and the two can therefore be treated as sufficiently orthogonal

in functional form to allow a basis decomposition in terms of the scaled true source

spectrum and a residual continuum term varying more slowly with frequency. The basic

method derives time-variable gain normalization factors

by fitting baseline- and

bandpass-corrected parallel-hand autocorrelation spectra

by fitting baseline- and

bandpass-corrected parallel-hand autocorrelation spectra

to a well-characterized

source total power spectrum

Jpp(ω) derived from a

template scan at a single antenna; this template scan is chosen based on SNR and the

quality of available a priori SEFD calibration information for the scan. The method is

readily applied to polarization observations by fitting

to a well-characterized

source total power spectrum

Jpp(ω) derived from a

template scan at a single antenna; this template scan is chosen based on SNR and the

quality of available a priori SEFD calibration information for the scan. The method is

readily applied to polarization observations by fitting

separately in each receptor

polarization p against the associated parallel-hand template spectra

Jpp(ω) and

Jqq(ω) (Kemball et al. 1995). These authors also introduced a

robust method to fit a composite baseline during the template-fit itself, avoiding the

need for prior baseline removal in the source and template spectra individually. Given

the uncertainties in a priori SEFD calibration discussed above, a secondary correction

is needed to determine and remove the differential polarization amplitude gain

gR/L

tying the template spectra in each sense of parallel-hand receptor polarization. In the

current paper,

gR/L

is used to refer to a ratio of terms

∥ GR ∥ and

∥ GL ∥ in the Jones matrix of

Eq. (9). At centimeter wavelengths,

Kemball et al. (1995) solved for this

differential polarization gain from relative ratios of the cross-power spectral

amplitudes on continuum extragalactic calibrator sources, which were assumed to have

Stokes V ~ 0. We note that in the case of maser sources it is necessary

to account for the average antenna noise contribution from the source

separately in each receptor

polarization p against the associated parallel-hand template spectra

Jpp(ω) and

Jqq(ω) (Kemball et al. 1995). These authors also introduced a

robust method to fit a composite baseline during the template-fit itself, avoiding the

need for prior baseline removal in the source and template spectra individually. Given

the uncertainties in a priori SEFD calibration discussed above, a secondary correction

is needed to determine and remove the differential polarization amplitude gain

gR/L

tying the template spectra in each sense of parallel-hand receptor polarization. In the

current paper,

gR/L

is used to refer to a ratio of terms

∥ GR ∥ and

∥ GL ∥ in the Jones matrix of

Eq. (9). At centimeter wavelengths,

Kemball et al. (1995) solved for this

differential polarization gain from relative ratios of the cross-power spectral

amplitudes on continuum extragalactic calibrator sources, which were assumed to have

Stokes V ~ 0. We note that in the case of maser sources it is necessary

to account for the average antenna noise contribution from the source

when transferring the

continuum polarization gain ratio to the spectral-line source (Kemball et al. 1995).

when transferring the

continuum polarization gain ratio to the spectral-line source (Kemball et al. 1995).

The template fitting method has several intrinsic advantages at the wavelengths

λ = 7 mm and λ = 3 mm considered in this paper

(Kemball & Diamond 1997). The method

implicitly includes opacity corrections in the determined amplitude scaling factors, and

is therefore insensitive to systematic errors in either the opacity parametrization of

Eq. (5) or in the published a priori

antenna gain curves. In addition, the method intrinsically tracks short-term variations

in the amplitude gain in each receptor polarization at each antenna that result from

factors such as pointing errors in the presence of beam squint, or rapid changes in

atmospheric attenuation due to highly time-variable local weather conditions. Such

short-term amplitude gain fluctuations are significantly more pronounced at wavelengths

shorter than  cm.

The gain factor information is also encoded in the autocorrelation spectra sampled at

the correlator integration rate, as opposed to to a separate sampling interval for

switched-noise Tsys measurement. The template-fitting

method is more statistically robust at measuring short-term amplitude gain fluctuations,

such as those caused by pointing errors, than a method based on detecting associated

changes in the measured Tsys values, as the latter requires

separating out changes in two unknown continuum quantities,

cm.

The gain factor information is also encoded in the autocorrelation spectra sampled at

the correlator integration rate, as opposed to to a separate sampling interval for

switched-noise Tsys measurement. The template-fitting

method is more statistically robust at measuring short-term amplitude gain fluctuations,

such as those caused by pointing errors, than a method based on detecting associated

changes in the measured Tsys values, as the latter requires

separating out changes in two unknown continuum quantities,

and the baseline noise terms. The template-fitting method exploits spectral structure in

this decomposition.

and the baseline noise terms. The template-fitting method exploits spectral structure in

this decomposition.

Kemball & Diamond (1997) used two

methods at λ = 7 mm to measure the differential polarization amplitude

gain

gR/L

for the template spectra: i) comparison of amplitude self-calibration gain corrections

derived from continuum calibrators assuming Stokes

V ~ 0, obtained for the reference antenna near the

time of the template spectrum observation; and, ii) cross-fitting the template spectra

in each polarization

Jpp(ω) and

Jqq(ω) to each other

using the template-fitting algorithm to derive the relative differential polarization

amplitude gain

gR/L

directly. Method (ii) assumes that the small non-zero integrated Stokes

V component of SiO emission does not significantly bias the estimated

gR/L,

i.e. that  .

.

In this paper we introduce several refinements to the template-fitting amplitude calibration method to improve its statistical performance in the millimeter wavelength range λ = 3 mm and λ = 7 mm considered here. These modifications are described in the following section.

3.3.3. Autocorrelation polarization self-calibration

VLBA system performance degrades sharply toward λ = 3 mm, consistent with array design specifications; this requires that we consider enhancements in the statistical performance of the template-fitting method in the low-SNR regime. In addition, the high representative fractional linear polarization of SiO masers ml ~ 10−30% described earlier suggests that higher-order terms, such as O(D.(Q + jU)), that arise in the full non-linear coupling of amplitude and instrumental polarization calibration contained in Eq. (8), may need to be assessed when using the template-fitting method acting on the parallel-hand autocorrelation spectra.

To explore both concerns, we have implemented an iterative self-calibration method to

derive the amplitude gains G(t), instrumental polarization D, and the

true source correlation spectrum J(ω) from the measured un-calibrated

autocorrelation spectra R(ω,t) at all antennas. The initial estimate of

the true source spectrum J(ω) is obtained from an weighted average of

baseline-corrected autocorrelation spectra over a restricted range of low zenith angle

and over a subset of antennas with high site elevation or known low mean precipitable

atmospheric water vapor. The spectra are calibrated a priori by the measured

and

opacity-corrected gain curves

and

opacity-corrected gain curves  provided by the VLBA, and then converted to, and averaged separately in

Stokes {I,Q,U,V} form. The spectra are pre-averaged at each

antenna over a short interval before baseline subtraction, and weighted by the inverse

mean-square residual error of the baseline polynomial fit. Spectra with a completeness