| Issue |

A&A

Volume 531, July 2011

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A19 | |

| Number of page(s) | 13 | |

| Section | Extragalactic astronomy | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201016336 | |

| Published online | 01 June 2011 | |

C+ emission from the Magellanic Clouds

II. [C II] maps of star-forming regions LMC-N 11, SMC-N 66, and several others

1

Sterrewacht Leiden, Leiden University, PO Box 9513, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands

e-mail: israel@strw.leidenuniv.nl

2

Center for Astrophysics and Space Astronomy, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80303, USA

Received: 15 December 2010

Accepted: 18 March 2011

Context. We study the λ 158 μm [C II] fine-structure line emission from star-forming regions as a function of metallicity.

Aims. We have measured and mapped the [C II] emission from the very bright HII region complexes N 11 in the LMC and N 66 in the SMC; as well as the SMC H II regions N 25, N 27, N 83/N 84, and N 88 with the FIFI instrument on the Kuiper Airborne Observatory.

Methods. In both LMC and SMC, the ratio of [C II] line to CO line and to the far-infrared continuum emission is much higher than seen almost anywhere else, including Milky Way star-forming regions, and whole galaxies.

Results. In the low metallicity, low dust-abundance environment of the LMC and the SMC UV mean free path lengths are much greater than those in the higher-metallicity Milky Way. The increased photoelectric heating efficiencies cause significantly greater relative [C II] line emission strengths. At the same time, similar decreases in PAH abundances have the opposite effect by diminishing photoelectric heating rates. Consequently, in low-metallicity environments relative [C II] strengths are high but exhibit little further dependence on actual metallicity. Relative [C II] strengths are slightly higher in the LMC than in the SMC which has both lower dust and lower PAH abundances.

Key words: ISM: clouds / galaxies: ISM / Magellanic Clouds / infrared: ISM / dust, extinction

© ESO, 2011

1. Introduction

Emission lines from carbon and carbon monoxide provide almost all the cooling of dense neutral gas in the interstellar medium. With a critical density for excitation ~3 × 103 cm-3, the  fine-structure line of singly ionised carbon (C + ) at 157.7 μm is a major cooling line for regions exposed to significant FUV photon fluxes (photon-dominated regions or PDRs: Tielens & Hollenbach 1985a,b). In Galactic H II regions as well as in the central regions of external galaxies (for instance Howe et al. 1991; Stacey et al. 1991; Jaffe et al. 1994; Malhotra et al. 2001; Negishi et al. 2001) the luminosity of the [C II] line is typically ~0.05−0.5% of the far-infrared luminosity (FIR) and correlates well with CO line intensities. For the Milky Way as a whole, the COBE measurements published by Wright et al. (1991) correspond to IC II/FIR = 0.1 − 0.2%. Substantially higher [C II] to far-infrared ratios I [C II] /FIR = 1.6 − 3.4% occur in high-latitude translucent clouds in the Milky Way (Ingalls et al. 2002).

fine-structure line of singly ionised carbon (C + ) at 157.7 μm is a major cooling line for regions exposed to significant FUV photon fluxes (photon-dominated regions or PDRs: Tielens & Hollenbach 1985a,b). In Galactic H II regions as well as in the central regions of external galaxies (for instance Howe et al. 1991; Stacey et al. 1991; Jaffe et al. 1994; Malhotra et al. 2001; Negishi et al. 2001) the luminosity of the [C II] line is typically ~0.05−0.5% of the far-infrared luminosity (FIR) and correlates well with CO line intensities. For the Milky Way as a whole, the COBE measurements published by Wright et al. (1991) correspond to IC II/FIR = 0.1 − 0.2%. Substantially higher [C II] to far-infrared ratios I [C II] /FIR = 1.6 − 3.4% occur in high-latitude translucent clouds in the Milky Way (Ingalls et al. 2002).

[C II] observations.

LMC-N 11 objects in [C II] map.

LMC-N 11 [C II] data.

Most of the 158 μm observations published to date have sampled objects with metal abundances similar to or greater than those in the Solar Neighbourhood. Moreover, they have usually sampled either relatively small regions of space in our own Galaxy, or very large volumes in other galaxies (typically the inner few kpc). The nearby Magellanic Clouds (LMC: 50 kpc, Schaefer 2008; SMC: 61 kpc, Szewczyk et al. 2009) provide an ideal opportunity to study objects with abundances significantly below solar, and at the same time study intermediate spatial scales. They are rich in interstellar gas and young, luminous stars, but carbon abundances are particularly low. The data reviewed by Pagel (2003) show that LMC and SMC HII regions have abundances (12 + lg[C]/[H] = 7.9 and 7.5, respectively) so that compared to the Milky Way, the LMC is under-abundant in C by a factor of four and the SMC by a factor ten. Due to its reduced metallicity and dust content, the neutral gas in the Clouds is substantially less shielded from UV continuum radiation long-ward of the Lyman limit than the gas in our own Galaxy. Because of its low ionisation potential of 11.3 eV, neutral carbon is the most abundant heavy element that can be ionised by the relatively unobstructed far-ultraviolet (FUV) radiation.

Mochizuki et al. (1994) have surveyed the whole LMC in the [C II] line at a relatively low resolution of 12.4′ (corresponding to a linear resolution of 194 pc) with the balloon-borne facility BICE. Their survey reveals a number of bright, discrete [C II] sources in addition to extended emission. The two brightest sources coincide with the very bright LMC H II region 30 Doradus and the N 160/N 159 H II complex to the south of it. These have been mapped in [C II] at much higher resolution by Poglitsch et al. (1995) and Israel et al. (1996, Paper I), respectively. The study of these very bright LMC H II region complexes has shown that they resemble Galactic translucent clouds, with [C II] line luminosities being a similarly large fraction of the total far-infrared luminosity, typically ~1−3%. The [C II] emission exhibits a poor correlation with CO line intensities on the relevant 10 pc scales: the local FCII/FCO ratios vary from 400 (N159S) to 113 000 (30 Dor).

We have shown in Paper I that at low to moderate densities (n ≈ 102 − 104 cm-3), the [C II] 158 μm line intensity varies roughly with the incident far-UV radiation field for Go = 1−1001. The intensity of the J = 1−0 12CO line varies much more slowly with Go, but at higher values of Go the [C II] line intensity saturates. In this paper, we pursue these conclusions and present results obtained towards N 11, the fourth brightest [C II] source in the LMC (after N 44), as well as a dozen H II regions in the lower-metallicity SMC, including the brightest SMC H II region, N 66 (Henize 1956).

2. Observations

The [C II] 158 μm maps presented in this paper were made with the MPE/UCB Far-Infrared Imaging Fabry-Perot Interferometer (FIFI, Poglitsch et al. 1991) during several flights of the NASA Kuiper Airborne Observatory (KAO) out of Christchurch (New Zealand) in April 1992. FIFI had a 5 × 5 focal plane array with detectors spaced by 40′′ (Stacey et al. 1992). Each detector had a FWHM of 55′′ corresponding to 14.3 pc on the LMC and 16.2 pc on the SMC. The beam shape was approximately Gaussian (68′′ equivalent disk; beam solid angle ΩB = 8.3 × 10-8 sr). The Lorentzian instrumental profile gave a 50 km s-1 spectral resolution. To optimise our sensitivity to extended low level emission, we observed in “stare” mode, by setting the bandpass of the Fabry-Perot to the line-center at the object velocity. To eliminate telescope offset and drift, all observations were chopped at 23 Hz and beam-switched once a minute against two reference positions about 6′ away. IRAS maps were used to verify that the reference positions were devoid of strong discrete far-infrared sources and therefore could reasonably be expected to be also free from discrete sources of contaminating line emission. The data were calibrated by observing an internal black-body source. The calibration uncertainty is of order 30% and the absolute pointing uncertainty is well below 15′′. The observed fields are summarised in Table 1, and the maps are shown in Figs. 1 through 4.

In Table 1, we list the position used as (0,0) reference in the maps (Cols. 2 and 3), the integration time for each array pointing (Col. 4), the resulting noise level in the maps (Col. 5), the number of separate array pointings used in constructing the maps (Col. 6), and the most prominent H II region in the field (Col. 7). In all maps, the array pointings were adjacent to one another. In SMC fields 3 and 4, we obtained additional array pointings on the strongest [C II] emission regions corresponding to the location of the H II regions SMC N 66, SMC N 83, and SMC N 84 in such a way as to obtain effective detector separations of 30′′ on those regions. The central part of the LMC N 11 complex was covered by 18 different, partially overlapping array pointings. The central 3′ × 3′ centered on LH 10 (N 11A and N 11B) was also observed with two different array pointings, offset from one another by half a beam separation on both the N-S and E-W directions. This field was therefore fully sampled, in contrast with the rest of the map which is slightly under-sampled.

All maps contain one or more peaks of [C II] emission. In Tables 2 and 4 we provide information on the objects included in the fields mapped, and their association with [C II] peaks in the maps. In Table 2, Cols. 2 through 4 provide the Henize (1956) object name, the associated CO cloud from Israel et al. (2003a), and the CO cloud offset position with respect to the reference position in Table 1. Columns 5 through 7 give the Lucke Hodge (1970) OB association number, the IRAS source name and position taken from Schwering Israel (1990), while Cols. 8 and 9 give the H II region Hα line flux (Caplan et al. 1996) and the 4750 MHz radio continuum flux density (Filipović et al. 1998). In Table 4, Cols. 2 through 4 provide the Henize (1956), Davies et al. (1976), and NGC object names. Column 5 lists the H II region position from Davies et al. with respect to the reference position in Table 1. Columns 6 and 7 give the corresponding IRAS source name and offset position taken from Schwering Israel (1990), while Cols. 8 and 9 give the H II region Hα line flux (Caplan et al. 1996; Cornett et al. 1997) and the 843 MHz radio continuum flux density (Ye et al. 1991). Detailed information for the [C II] peaks themselves is given in Tables 3 and 5.

3. Results and analysis

3.1. LMC

3.1.1. The N 11 field

|

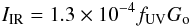

Fig. 1 Map of the central part of LMC-N 11. [C II] contours are linear at multiples of 2.125 × 10-5 erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1. Integrated J = 1−0 12CO emission is represented by grayscales in the range 1−10 K km s-1. Small dots mark the grid points sampled in [C II]. The locations of the major H II region components N 11A through N 11F are schematically indicated. All [C II] peaks (marked by their number from Tables 2 and 3) are associated with a CO cloud. The lack of CO emission near [C II] cloud 4 may reflect poor sampling of the CO map at this position. |

The third most luminous star-forming complex in the LMC, N 11, is located opposite 30 Doradus at the northwestern edge of the galaxy. Unlike the highly centralised 30 Doradus region, N 11 is an extended complex of individual OB associations catalogued by Lucke Hodge (1970). These illuminate a variety of discrete H II and CO clouds (Israel et al. 1993; Mac Low et al. 1998). A striking feature of N 11 is the super-bubble (Meaburn et al. 1989) formed by the action of stellar winds from the OB association LH 9 (NGC 1760; age 7 Myr, Mokiem et al. 2007) at its center. The bubble is a prominent source of soft X-rays (Mac Low et al. 1998; Nazé et al. 2004; Maddox et al. 2009) implying significant interaction between the stars and the surrounding gas. At the northern edge of the bubble is the much younger OB association LH 10 (NGC 1763; 3 Myr, Mokiem et al. 2007) which is still embedded in the bright nebula N 11B (cf. Heydari-Malayeri & Testor 1983). Three O3 stars have been identified in the LH 10 association (Parker et al. 1992). An even younger compact object, N 11A (IC 2116, Mac Low et al. 1998; Nazé et al. 2001; Heydari-Malayeri et al. 2001), occurs in the same area. The location and apparent age difference of LH 10 and LH 9, as well as the gas kinematics, have led to the suggestion that the formation of LH 10 and other stellar groups was triggered by the expanding shells emanating from LH 9 (Walborn Parker 1992; Rosado et al. 1996; Barba et al. 2003; Hatano et al. 2006; Mokiem et al. 2007).

The OB association LH 13 (NGC 1769), to the east of the bubble, appears to be younger than 5 Myr and excites the bright H II region N 11C/D, an ionised region seemingly divided in two by a dust band crossing in front (Heidari-Malayeri et al. 1987). The association LH 14 (NGC 1773), northeast of the bubble, excites the H II region N 11E and should also be young as it contains an O4-5V star (Heidari-Malayeri et al. 1987).

Much of N 11 was surveyed in the J = 1−0 transition of 12CO as part of an ESO-Swedish Key Programme; more limited mapping of the central part was conducted in the J = 2−1 transition (Israel et al. 2003a). The N 11 molecular clouds are quite warm, with kinetic temperatures of 60−150 K. This is higher than expected for clouds heated by stellar UV photons only. The CO clouds are also quite distinct, i.e. there is almost no diffuse CO emission between the bright clouds. Both aspects suggest a strong influence of the ambient radiation field (UV, X-rays) on the molecular gas including processing of the diffuse gas.

Our [C II] line observations, although not fully covering the large N 11 complex, have a spatial resolution similar to that of the 12CO maps of Israel et al. (2003a). In Fig. 1 contours trace the distribution of [C II] emission, and shades of gray represent the J = 1−0 CO distribution (cf. Fig. 1 of Israel et al. 2003a). Peak and integrated [C II] intensities of the various clouds detected are listed in Table 3, Cols. 2 and 4 respectively.

The CO and the [C II] distributions are roughly similar. Both trace the circumference of the super-bubble and follow the distribution of the OB associations and H II regions. Bright [C II] emission is associated with bright CO emission and vice versa. The highest surface brightnesses in the map are found towards N 11AB, containing LH 10 ([C II] peak surface brightness of 2.2 × 10-4erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1). This is also the brightest H II region, with half to two thirds of the Hα and thermal radio flux of the complex (cf. Table 2). Less intense diffuse emission is present over a large part of the area mapped. Both the intensity (1.0 ± 0.3 × 10-4erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1) measured by Boreiko & Betz (1991) towards N11 B(CO) and their upper limit for N11 B(H2) are in rather good agreement with our map results. Mochizuki et al. (1994) measured a beam-averaged intensity 0.6 × 10-4erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1 in a 12.4′ beam, roughly corresponding to the area mapped and shown in Fig. 1.

Two [C II] clouds are associated with the second-brightest H II region complex N 11C and N 11D (illuminated by LH 13) but the brightest of the two [C II] clouds (peak surface brightness 1.7 × 10-4erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1) occurs towards the weaker CO cloud. There are other significant differences. Figure 1 shows that the [C II] emission extends far beyond the boundaries of the CO clouds, and that it is largely continuous unlike the highly fragmented CO emission. The contrast between [C II] peaks and inter-cloud regions is much less in [C II] than in CO. [C II] peaks are displaced from CO peaks in the direction of the ionising OB stars. The shape of the extended [C II] emission in Fig. 1 strongly suggests large-scale dissociation of CO and subsequent ionisation of the resulting neutral carbon.

The offset between peak CO and peak [C II] emission is particularly clear in N 11C, N 11D, and N 11E. The Hα emission regions N 11B, N 11C, N 11D, and N 11E are centered on the brightest stars of their respective OB associations. These stars occur in the gaps between [C II] clouds 4 and 5, clouds 9 and 10, and to the southeast of cloud 11, respectively. In all cases, the lines of sight towards the stars and their HII regions show relatively little CO and [C II] emission, which suggests that in those directions most carbon is multiply ionised. The far-infrared emission from hot dust peaks at these same positions consistent with the expected intense irradiation. The association of emission from ionised carbon and hydrogen, molecular gas, and warm dust is characteristic of PDRs (Kaufman et al. 1999).

3.2. SMC

3.2.1. The N 66 field

|

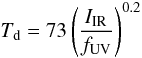

Fig. 2 Map of SMC-N 66. [C II] contours are linear at multiples of 1.0 × 10-5 erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1. Integrated J = 2 − 1 12CO emission is represented by grayscales in the range 0.5 − 5.0 K km s-1. The locations of the N 66 bar, the bright H II component N 66A, and the CO “plume” are indicated. Brightest [C II] and CO emission occurs just off N 66A near position (0, 0). |

N 66, excited by the OB association NGC 346, is the largest and brightest H II region in the SMC. It is located about midway in the main body of the SMC Bar and extends over an area of 3′ × 6′ (linear size 50 × 110 pc). NGC 346 is a young cluster of age about 3 Myr, and it contains several O stars among which are O3–O5 stars (Walborn & Blades 1986; Evans et al. 2006, and references therein). Star formation has occurred in this region for much longer, up to 10 Myr, and must be ongoing as N 66 contains numerous pre-main-sequence objects (Sabbi et al. 2007; Simon et al. 2007; Hennekemper et al. 2008; Gouliermis et al. 2006, 2008, 2009) as well as a supernova remnant (Ye et al. 1991). Although the nebula shows considerable structure, there are no strong peaks in either line or continuum emission from gas and dust. The H II region proper consists of an extended envelope of diffuse ionised gas in which a bright bar-like structure (southeast to northwest) is embedded. A bright region (N 66A) occurs just off the Bar to the northeast. Much of the mid-infrared line and continuum emission exhibit the same structure (Rubio et al. 2000; Contursi et al. 2000), as indeed does the distribution of the bright stars themselves (cf. Gouliermis et al. 2006; Hennekemper et al. 2008) as illustrated very nicely by public HST images. Recent star formation along the N 66 Bar may have been triggered by expanding windblown shells (Gouliermis et al. 2008).

Rubio et al. (2000) mapped carbon monoxide in N 66 in the J = 1 − 0 and J = 2 − 1 transitions at resolutions of 43′′ and 21′′, respectively. The CO maps resemble the general picture seen at other wavelengths. Much of the CO follows the N 66 Bar (as does hot H2 also observed by Rubio et al. 2000), but much stronger CO emission occurs in a linear “plume” pointing northeast at right angles to the N 66 Bar. It almost appears as if N 66A is the “burning” end of the feature. The distribution of [C II] in N 66 closely resembles the Hα and CO distributions shown by Ye et al. (1991) and Rubio et al. (2000). The lowest contour in our map (Fig. 2) roughly follows the contour of 15 − 20% of the Hα peak brightness. The highest [C II] intensities occur in the N 66 Bar where the presence of near-infrared K-band H2 emission suggests strong irradiation of the ambient ISM. A secondary [C II] maximum is to the northeast of the bar, almost precisely adjacent to the strong CO “plume”. This [C II] maximum is relatively weak with respect to the adjacent CO, but relatively strong with respect to the almost coincident Hα peak (cf. Fig. 3 by Ye et al. 1991). It suggests a PDR seen from the side. Apart from scale, N 66 is similar to the LMC H II region complexes 30 Doradus and N 160 which combine relatively small CO clouds with rather extended [C II] emission (Johansson et al. 1998; Poglitsch et al. 1995; Israel et al. 1996). Like these sources, N 66 appears to be a relatively evolved object in which most of the original molecular gas has been consumed by star formation or processed by irradiation. Much of the remaining CO has been photo-dissociated, and much of the resulting C° has been turned into the extended cloud of C+ shown in Fig. 2. Clearly, this process is still actively going on near N 66A.

3.2.2. The N 83/N 84 field

|

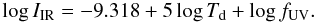

Fig. 3 Map of SMC-N 83/N 84/N 85. [C II] contours are linear at multiples of 1.0 × 10-5 erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1. Integrated J = 1−0 12CO emission is represented by grayscales in the range 0.5−4.5 K km s-1. The positions of the (mostly compact) H II regions in the complex are marked. |

|

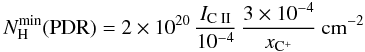

Fig. 4 Left: [C II] Map of SMC-N 25 field. Contours are linear at multiples of 0.72 × 10-5 erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1. Integrated J = 1−0 12CO emission is represented by grayscales in the range 0.5−5.0 K km s-1. Center: [C II] Map of SMC-N 27 field. Contours are linear at multiples of 1.35 × 10-5 erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1. The positions of the H II regions N27, N27-S, and N 19 are indicated. Integrated J = 1−0 12CO emission is represented by grayscales in the range 1.0−13.0 K km s-1. Right: [C II] map of SMC-N 88 field. Contours are linear at multiples of 0.72 × 10-5 erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1. Integrated J = 1−0 12CO emission is represented by grayscales in the range 0.2−2.4 K km s-1. |

The SMC Wing has a much lower stellar and gaseous surface density than the SMC Bar, but nevertheless contains a number of mostly compact but intense H II regions. Most prominent is the N 83/N 84/N 85 complex (DEM 147-152) which consists of several small nebulae each excited by a single star or a tight group of stars (Testor & Lortet 1987) in the NGC 456 and NGC 460 associations. The spectral type of the ionising stars ranges from O4 to O9, the associated H II mass is only ~5000 M⊙, and typical visual extinctions are between 0.5 and 1.0 mag (Copetti 1990; Caplan et al. 1996). Relatively bright far-IR emission coincides with the complex (LI-SMC 199-202, Schwering & Israel 1990). SEST CO observations of this field have been discussed by Israel et al. (2003b), Bolatto et al. (2003), and Leroy et al. (2009). Figure 3 shows contours of the widespread [C II] emission and the CO map from Israel et al. (2003b) in shades of grey. For a map of the CO emission superposed on a red optical image, identifying the various H II regions in more detail, we refer to Bolatto et al. (2003).

Again, we find [C II] and CO to be loosely correlated. There is an extended [C II] cloud (dimensions of 2.6′ × 4.6′, i.e. 45 × 80 pc; peak surface brightness about 7 × 10-5 erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1) in the same direction as the large nebula N 83, suspected by Bolatto et al. (2003) to be a supernova remnant. The brightest CO cloud appears to embrace the northeastern boundary of N 83 and contains the compact objects N 83B and N 83C. The [C II] emission is mostly adjacent to the CO cloud and coincident with N 83 and its brightest part, N 83A, and wraps around the CO cloud in the north. The strong infrared counterpart, LI-SMC 199/200, is offset to the north by 14 pc from the [C II] peak.

The small H II region N 84C is associated with a distinct but minor CO cloud. There is no corresponding [C II] peak; rather it is on a [C II] gradient. N 84A is an extended H II region on the surface of a large shell (55 pc) of CO emission. Much of the complex is at a minimum in [C II] emission. The infrared counterpart LI-SMC 201 is 17 pc north of the H II region N 84A and its associated [C II] peak. This [C II] peak is part of a ridge of ionised carbon (peak surface brightness about 6 × 10-5 erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1) that starts at the eastern edge of the CO shell and extends southwards to the compact H II regions N 84B and N 84D in the lower left corner of Fig. 3. The [C II] maximum associated with N 84 has an elongated shape of about 1.3′ × 3.5′ (23 × 61 pc). The compact objects N 84 B and N84 C are embedded in a distinct but not very bright CO cloud. As the map shows, the [C II] emission is mostly adjacent to this CO cloud. It overlaps with the extended Hα emission seen in optical images but its maximum is just south of the ionised gas and about 8 pc east of the CO cloud. The infrared peak LI-SMC 202 occurs between the [C II] emission peaks from N 84A and N 84B and is about 12 pc north from the CO peak. Finally, there is an extended region of diffuse [C II] emission with a surface brightness of 2 × 10-5 erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1 (2σ) covering the area east of N 83 and north of N 84 (upper right in Fig. 3). It has only a very weak CO counterpart.

3.2.3. Other fields: N 22/N 25/N 26, N 19/N 27, and N 88

SMC objects in [C II] maps.

SMC [C II] data.

The N 22/N 25/N 26 field (Fig. 4, left) contains a single [C II] source of diameter 1.3′ × 2.1′ (23 × 36 pc), located between the H II regions N 25/N 26 and N 22 (NGC 267), but closest to the former. The largest H II region N 22 (DEM 37: 2′) is located 98′′ (28 pc) south from the [C II] peak, marking the southern edge of the [C II] source. The brighter and more compact H II regions N 25 and N 26 (DEM 38: 1′) are located 33′′ (10 pc) north of the [C II] peak (see Fig. 1 by Testor 2001) and mark the northern edge of the source. Both N 25/N 26 and N 22 are relatively strong 843 MHz radio continuum sources (Mills & Turtle 1984) in the populated southern half of the SMC Bar. N 25 and N 26 coincide with the infrared source LI-SMC 45. Diffuse [C II] emission, at a typical level of 2.7 × 10-5 erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1 (i.e. 3σ), extends beyond the map boundaries. All three H II regions appear to be excited by single O-stars (Hutchings & Thompson 1988; Testor 2001). As Fig. 4 illustrates, the [C II] emission is very nearly coincident with the CO cloud (SMC-B2 No. 3) mapped by Rubio et al. (1993) just south of N 25 and N 26. The H II region N 22 appears to fill a hole in the CO distribution. Thus, the observed [C II] emission closely follows the CO distribution, and its major source of excitation are N 25 and N 26 (LI-SMC 45) at a nominal projected distance of 34′′ or 9.5 pc.

The N 19/N 27 field (Fig. 4, center) contains a bright [C II] source of diameter 1.9′ (33 pc) offset to the north by about 5′′ from the compact H II region N 27 (DEM 40: 0.8′). N 27 has a strong counterpart in the 843 MHz radio continuum map by Mills & Turtle (1984). It is located at the southern edge of a relatively bright and compact CO cloud of diameter 1.4′ (deconvolved linear size of 21 pc). As Fig. 4 shows, the CO peak is offset from the [C II] source by 25′′ to the northwest. The higher-resolution J = 2−1 12CO map published by Rubio et al. (1996) shows the bulk of the CO emission to be in a curved ridge actually adjacent to the [C II] peak (projected peak-to-peak separation 6 pc). The strong infrared source LI-SMC 49 is very close to the [C II] peak. Thus, both FIR and [C II] peak in between the H II region and the CO cloud, at about 5 pc projected distance from either.

|

Fig. 5 Diagrams illustrating the various ratios of [C II], CO and FIR emission for sources in the LMC (filled triangles, data from this paper, Israel et al. 1998; and Poglitsch et al. 1995), the SMC (filled circles, data from this paper), IC 10 (open triangles, data from Madden et al. 1997), and the Milky Way (open squares, data from Table 5 in Stacey et al. 1991). The shift of sources in the low-metallicity galaxies LMC, SMC, and IC 10 with respect to those in the Milky Way is very clear and due to relatively brighter [C II] emission caused by greater UV mean free path lengths in the low metallicities of the Magellanic Clouds and IC 10. One might expect the low-metallicity SMC sources to be shifted even more than the intermediate-metallicity LMC sources, but the opposite is true. The lesser SMC shift reflects lower [C II] photo-electric heating due to the depletion of PAHs in that galaxy. See Sect. 4 for further details. |

At a level of 3.3 × 10-5erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1 (i.e. 4σ), diffuse emission extends to the west. One of the minor maxima in this emission appears to be associated with the diffuse H II region N 19 (DEM 31: 1.8′). The eastern boundary of the [C II] emission is sharply defined, but weak diffuse [C II] emission also extends southwards towards the compact H II region DEM 39 (0.5′) which is off the map. To the east and north of DEM 39, relatively weak CO clouds are found (see Fig. 3 in Rubio et al. 1993). Further comparison shows that the [C II] emission appears to skirt the radio emission from a complex of sources southwest of N 27, containing at least one extended supernova remnant.

The N 88 field (Fig. 4, right) contains a single [C II] source with a deconvolved diameter of 1′ (17 pc). The very bright and compact HII region N 88A/N 88B (Testor & Pakull 1985; Testor et al. 2010) are located 23′′ (7 pc) south of the [C II] peak and coincides with the infrared source LI-SMC 215. The 12CO and [C II] peaks almost coincide (see Fig. 4), but the CO extends to the north, whereas the [C II] has an extension to the south, encompassing the HII region. In the compilation by Caplan et al. (1996), N88 has the largest extinction,  mag, of all three dozen H II regions listed (mean value 0.50 mag). As in previous cases, the [C II] emission extends well beyond the CO boundaries.

mag, of all three dozen H II regions listed (mean value 0.50 mag). As in previous cases, the [C II] emission extends well beyond the CO boundaries.

3.3. Fluxes and luminosities

All [C II] results are summarised in Tables 3 and 5, along with the relevant infrared and CO data. Peak intensities and positions with respect to the reference position from Table 1 are given in Cols. 2 and 3; the integrated [C II] intensity is listed in Col. 4. Two SMC H II regions (DEM 39, DEM 150) do not coincide with a peak in the [C II] emission: here we have taken the actual [C II] intensity at the position listed; their estimated integrated [C II] intensities are uncertain. No [C II] emission was detected towards DEM 154; we calculate an upper limit to the luminosity assuming a source size of 1′. In the next section we make quantitative estimates of the physical conditions characterising the emitting regions; however, some important inferences can be drawn simply from examination of the data given in Tables 3 and 5. The various ratios of [C II], CO and far-infrared emission listed in those Tables are illustrated in Fig. 5. For comparison, we have also included the relevant ratios for sources in the Milky Way (taken from Stacey et al. 1991) and in the dwarf irregular galaxy IC 10 (Madden et al. 1997).

The peak intensities observed in the 158 μm line in the N 11 clouds are typically IC II ≈ 1−2 × 10-4erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1, very similar to the values measured elsewhere in the LMC by Poglitsch et al. (1995) and Israel et al. (1996): in 30 Doradus, in N 159, and in N 160. In contrast, the peak intensities of the SMC clouds are lower by a factor of ~3. Only the highest measured value, that of N 27, just exceeds 10-4erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1. N 27 (LI-SMC 49, also known as LIRS-49) is an unusually bright object for the SMC. It is also the second brightest CO cloud in the SMC. The integrated fluxes in the 158 μm line and the infrared continuum2 are smaller than those in the observed LMC regions by a similar factor. The ratios of the 158 μm line to far-infrared continuum fluxes for the SMC sources are about half those seen in the LMC, at 0.7−1.7%, but still well above those of comparable Galactic sources. Similarly high values are seen in the nearby, low-metallicity irregular galaxy IC 10 (Madden et al. 1997). As we discuss below, this ratio has important implications for the efficiency of grain photoelectric heating and the typical FUV radiation field characterising PDRs in the SMC.

One of the characteristics that has also emerged from the study of C + 158 μm line emission from low-metallicity galaxies (Poglitsch et al. 1995; Israel et al. 1996; Madden et al. 1997) is a high ratio of the 158 μm line flux to that of 12CO J = 1−0 line. The typical value seen in “warm dust” galactic nuclei or Galactic H II regions is FCII/FCO ≈ 4000 − 6000, while in “cool dust” galaxies and Galactic giant molecular clouds (GMCs) the ratio is approximately 1500 (Stacey et al. 1991). In contrast, the ratio observed in the infrared-luminous regions of the N159 and N160 complex range from 5600 to 34 000 (Israel et al. 1996), while it is approximately 105 in the massive star-forming complex 30 Doradus (Poglitsch et al. 1995). Table 3 gives equally high ratios FCII/FCO ≈ 20 000−26 000 for the clouds in N 11. In the SMC regions, where we have relevant CO intensities for about half the C + sample, we calculate similar ratios, ranging from 15 000 to 83 000. Three out of the six regions with CO data exhibit ratios FCII/FCO ≥ 60 000. Similar behavior of the LMC and SMC [OI]63 μm/FIR line ratios has been noted by van Loon et al. (2010). As we will discuss in Sect. 4.1, such large ratios are a direct consequence of the reduced metallicity and dust-to-gas ratios in the Magellanic clouds.

We also note that most of the regions observed in the LMC have FIR/FCO ratios comparable to Galactic GMCs or IR-bright galactic nuclei, but substantially below the value seen in Galactic H II regions (see the discussion in Paper I). Only 30 Doradus approaches the typical H II region value. In contrast, half of the SMC sample (the regions with the highest FCII/FCO ratios) show FIR/FCO ratios similar to the Galactic H II region value. However, as we discuss below, the similarity of this ratio is misleading, because the physical conditions in the SMC regions are markedly different from those in Galactic H II regions (as evidenced by the order-of-magnitude larger values of both FCII/FCO and FCII/FIR in the SMC regions).

4. Physical conditions and PDR parameters

As first demonstrated by Crawford et al. (1985) and Stacey et al. (1991), much of the 158 μm line emission of C + originates in PDRs: the interfaces between dense molecular clouds and the H II regions surrounding luminous, early-type stars. Theoretical studies of high-density, high-UV flux PDRs were pioneered by Tielens & Hollenbach (1985a,b). A summary of both theory and observation is given in Hollenbach & Tielens (1997). PDRs are luminous sources of 158 μm line emission because there is an extensive zone in which carbon is kept largely in the form of C + through ionisation by FUV photons, and the gas temperature is kept high enough (relative to the line energy above ground of 91 K) that the 158 μm transition is easily excited. The extent of the C + zone is determined by attenuation of the FUV photons by dust. As we will show below, this leads to a crucial scaling: if the dust-to-gas ratio and the gas-phase carbon abundance are varied by the same factor, the column density of singly-ionised carbon will remain essentially constant. This has profound implications for the nature of PDRs and the interstellar medium in low-metallicity galaxies.

In all cases we are assuming that all of the C + emission arises from PDRs, and we have ignored any contribution from the H II regions themselves. Although this is not strictly correct, it is unlikely that this assumption has any significant impact on the analysis, for two reasons. (1) In Galactic star-forming complexes, the contribution from the H II regions to the total C + emission is minor, ~10% or less (e.g., Stacey et al 1991), since much of the carbon is more highly ionised than C + . Theoretical models (Kaufman et al. 2006; Abel et al. 2005) of H II region/PDR complexes predict ratios of this order for Solar metallicity gas. In our observations, the PDR origin of the C + emission is directly seen, for example, in the map of LMC N 11, which shows that the C + emission is correlated with the CO emission, tracing the remnant molecular gas and not the H II regions. (2) The volume of H II regions is set by the attenuation of Lyman continuum photons by absorption by neutral hydrogen, and is independent of the metallicity. Hence the H II region contribution in low-metallicity galaxies such as the LMC and the SMC will be less important than it is in Galactic star-forming regions: the C + column in the H II region will decline with metallicity Z, while the C + column in a PDR is nearly independent of Z (Maloney & Wolfire 1997). As shown by Kaufman et al. (2006), the ratio of the PDR to H II region contributions is expected to scale as 1/Z. Hence we can safely assume that any H II region contribution is minor.

4.1. Estimates of Go

As in our previous studies of C+ emission from the Large Magellanic Cloud, we have the advantage of much higher spatial resolution (1′ = 15−17 pc for assumed LMC and SMC distances of 50 and 60 kpc respectively) than is generally possible for extragalactic observations. This is especially important since the most important parameter controlling the physical and thermal structure of a PDR, Go/n (where Go is the flux over the range 6 − 13.6 eV, normalised to 1.6 × 10-3 erg cm-2 s-1, and n is the gas density), can ordinarily only be estimated indirectly (e.g., Wolfire et al. 1989, 1990). For the LMC and the SMC, however, as we showed in our previous study of the N 159 and N 160 regions (Paper I), we can obtain much more direct estimates of Go using observations of the 158 μm line-emitting regions at other wavelengths.

We do this in two different ways. In the first, we obtain an estimate of the Lyman continuum photon flux from observations of either extinction-corrected Hα fluxes or radio continuum observations (Caplan et al. 1996; Ye et al. 1991; Filipović et al. 1998). There is no indication that the IMF’s of ionizing star clusters in the SMC, the LMC and the Milky Way are grossly different; minor differences do not influence our conclusions. We assume a point source for the ionising radiation and an average distance which is based on the extent of the 158 μm emission. For an assumed black-body temperature TBB, comparison of the theoretical and observed Lyman continuum photon luminosities then gives the scaling factor to obtain the 6 − 13.6 eV flux for the observed regions. As we have seen, N 11 is excited by very luminous O stars, as are also the SMC clouds (N66: Walborn & Blades 1986; Massey et al. 1989; N83-N84: Testor & Lortet 1987; for the other H II regions, the ionisation parameter as derived from the radio continuum observations also indicates that the exciting stars are O stars), hence we assumed a temperature TBB = 50 000 K. The derived values of Go (for all sources for which Hα and/or radio continuum data are available) are given in Table 6.

Since the emitting regions are spatially resolved in the infrared, we can also use the far-infrared surface brightness to estimate Go. If we assume that all of the incident FUV radiation is absorbed by dust within a cloud and re-radiated in the far-infrared, then the IR surface brightness is simply related to Go:  (1)where fUV = 2 for B stars (which emit approximately half of their flux between 6 and 13.6 eV, and the other half at energies E < 6 eV, so that the total flux absorbed by the dust is about twice that in the 6 − 13.6 eV band), and fUV = 1 for O stars (which also emit about half their total flux in the 6 − 13.6 eV band, but emit the other half at energies E > 13.6 eV; these photons are all absorbed within the H II region – see Hollenbach et al. 1991, hereafter HTT). The values of Go derived from the infrared surface brightness (with fUV = 1 since, as noted earlier, all of these regions are powered by O stars) are also given in Table 6. The uncertainties in these estimates of Go are probably about a factor of 3.

(1)where fUV = 2 for B stars (which emit approximately half of their flux between 6 and 13.6 eV, and the other half at energies E < 6 eV, so that the total flux absorbed by the dust is about twice that in the 6 − 13.6 eV band), and fUV = 1 for O stars (which also emit about half their total flux in the 6 − 13.6 eV band, but emit the other half at energies E > 13.6 eV; these photons are all absorbed within the H II region – see Hollenbach et al. 1991, hereafter HTT). The values of Go derived from the infrared surface brightness (with fUV = 1 since, as noted earlier, all of these regions are powered by O stars) are also given in Table 6. The uncertainties in these estimates of Go are probably about a factor of 3.

PDR parameters, masses, and luminosities.

In N 11, the two methods yield modest radiation field strengths (except for the very bright N11AB complex) that are in good agreement with each other. In the SMC objects we get much higher radiation field estimates from the Lyman continuum flux than from the far-infrared surface brightness. The IR surface brightnesses in the SMC are anomalous in another respect as well. Simply from energy balance considerations, it is possible to derive an equation relating the dust temperature to Go (HTT):  . Inverting Eq. (1) to an expression for Go and substitution into the expression for Td then gives a relation between Td and the infrared surface brightness:

. Inverting Eq. (1) to an expression for Go and substitution into the expression for Td then gives a relation between Td and the infrared surface brightness:  (2)where IIR is in erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1; this can be rearranged to an expression for the expected IR surface brightness as a function of dust temperature:

(2)where IIR is in erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1; this can be rearranged to an expression for the expected IR surface brightness as a function of dust temperature:  (3)Pak et al. (1998) derived an analogous expression (assuming fUV = 2) and argued that it is obeyed by Galactic PDRs (specifically, Orion and NGC 2024), but substantially violated in both the LMC and the SMC, indicating that the beam filling factors in the clouds are of order 0.1. However, the data plotted in Pak et al. (their Fig. 7) do not really support this interpretation. If the SMC points are excluded, the mean value of the ratio of the observed IR surface brightness to that predicted using Eq. (3) (with fUV = 1, as appropriate for both the LMC and SMC) is 0.7. The mean value for the SMC points is only 0.05. This is completely inconsistent with beam filling factor arguments unless clouds in the SMC are much smaller than those in the LMC, as the expected decrease for the SMC would be only a factor of (50/60)2 ≈ 0.7, whereas the observed decrease is an order of magnitude greater. In fact, the mean cloud sizes in the SMC are not different from those in the LMC (cf. Table 6).

(3)Pak et al. (1998) derived an analogous expression (assuming fUV = 2) and argued that it is obeyed by Galactic PDRs (specifically, Orion and NGC 2024), but substantially violated in both the LMC and the SMC, indicating that the beam filling factors in the clouds are of order 0.1. However, the data plotted in Pak et al. (their Fig. 7) do not really support this interpretation. If the SMC points are excluded, the mean value of the ratio of the observed IR surface brightness to that predicted using Eq. (3) (with fUV = 1, as appropriate for both the LMC and SMC) is 0.7. The mean value for the SMC points is only 0.05. This is completely inconsistent with beam filling factor arguments unless clouds in the SMC are much smaller than those in the LMC, as the expected decrease for the SMC would be only a factor of (50/60)2 ≈ 0.7, whereas the observed decrease is an order of magnitude greater. In fact, the mean cloud sizes in the SMC are not different from those in the LMC (cf. Table 6).

It is quite likely, therefore, that in both the LMC and the SMC the beam filling factor is generally close to unity (for the LMC, this interpretation is supported by the generally good [~ factor of two] agreement between the values of Go estimated from the IR surface brightness and those estimated from alternative methods (Paper I and this paper), and that the discrepancy between the observed and expected Td − IIR relation has another cause. This is almost certainly the reduced dust-to-gas ratio in the Magellanic Clouds, especially the SMC. The ratio of (total) hydrogen column NH to visual extinction AV for the (Solar neighborhood) Milky Way, the LMC, and the SMC are NH/AV = 1.9 × 1021, 8.0 × 1021, and (1.7 − 6.7) × 1022cm-2 mag-1, where the Galactic value is from Bohlin et al. (1978), the LMC value is from Fitzpatrick (1985), and the lower and upper ends of the SMC range are from Bouchet et al. (1985) and Schwering (1988), respectively. A cloud of nominal column NH = 2 × 1022cm-2 in the SMC therefore has a visual extinction Av ~ 1, so that the PDR (whose extent is determined by the absorption of the FUV photons by dust) may occupy the entire column, and some fraction of the incident FUV photons will pass through the entire column without absorption and escape the galaxy entirely. The dramatic overall decrease in IR surface brightness in the SMC (for a fixed dust temperature) even compared to most of the LMC points suggests that this is in fact the case; as we show below, quantitative analysis of the C + 158 μm emission from the SMC lends further support to this argument.

4.2. PDR parameters

The [C II] 158 μm line intensity is directly proportional to the C + column density if the emission is optically thin. The minimum value for this column follows from the assumption that the emission occurs in the high-density (n ≫ ncr ≈ 3000cm-3), high-temperature (T ≫ 91 K) limit. For a resolved source we find: ![\begin{equation} \Icii = 5\times10^{-4} N(\cp)[17.5]\; \ergsr \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2011/07/aa16336-10/aa16336-10-eq178.png) (4)and

(4)and ![\begin{equation} \taucii = 0.163 N(\cp)[17.5] \Delta V_{5}^{-1} (91/T) \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2011/07/aa16336-10/aa16336-10-eq179.png) (5)where N(C + ) [17.5] is the C + column density in units of 3 × 1017cm-2, and ΔV5 is the line FWHM in units of 5 km s-1. In LMC [C II] clouds, ΔV5 = 2 (Boreiko & Betz 1991). From this we obtain the minimum hydrogen PDR column density

(5)where N(C + ) [17.5] is the C + column density in units of 3 × 1017cm-2, and ΔV5 is the line FWHM in units of 5 km s-1. In LMC [C II] clouds, ΔV5 = 2 (Boreiko & Betz 1991). From this we obtain the minimum hydrogen PDR column density  (PDR):

(PDR):  (6)where ICII is in units of erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1, and xC + is the gas-phase C+ abundance relative to hydrogen. We assume that in a PDR the C+ abundance equals the total gas-phase carbon abundance, and we assume carbon locked up in dust to be a negligible amount. The gas-phase carbon abundances are xC = 8 × 10-5 and xC = 3 × 10-5 for the LMC and SMC respectively, factors of about four and ten below the Solar Neighbourhood carbon abundance (see Pagel 2003). Thus, for LMC conditions, Eq. (3) becomes:

(6)where ICII is in units of erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1, and xC + is the gas-phase C+ abundance relative to hydrogen. We assume that in a PDR the C+ abundance equals the total gas-phase carbon abundance, and we assume carbon locked up in dust to be a negligible amount. The gas-phase carbon abundances are xC = 8 × 10-5 and xC = 3 × 10-5 for the LMC and SMC respectively, factors of about four and ten below the Solar Neighbourhood carbon abundance (see Pagel 2003). Thus, for LMC conditions, Eq. (3) becomes:  (7a)whereas for SMC conditions we should take

(7a)whereas for SMC conditions we should take  (7b)Both the N 11 results presented here as well as the N 159/N 160 (Paper I) and 30 Dor (Poglitsch et al. 1995) results show that in the LMC [C II] clouds, the detected 158 μm emission ranges from about 7 × 10-5erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1 up to about 4 × 10-4erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1, so that the PDR column densities range from NH = 6 × 1020cm-2 up to (beam-averaged) peaks of NH = 3 × 1021cm-2. Although the 158 μm emission detected from the SMC is about three times weaker, the lower carbon abundance compensates for this, and beam-averaged PDR column densities are NH = 0.5 − 4 × 1021cm-2, essentially identical to the LMC results.

(7b)Both the N 11 results presented here as well as the N 159/N 160 (Paper I) and 30 Dor (Poglitsch et al. 1995) results show that in the LMC [C II] clouds, the detected 158 μm emission ranges from about 7 × 10-5erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1 up to about 4 × 10-4erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1, so that the PDR column densities range from NH = 6 × 1020cm-2 up to (beam-averaged) peaks of NH = 3 × 1021cm-2. Although the 158 μm emission detected from the SMC is about three times weaker, the lower carbon abundance compensates for this, and beam-averaged PDR column densities are NH = 0.5 − 4 × 1021cm-2, essentially identical to the LMC results.

Under realistic conditions of finite density and temperature, the true column densities are typically double these values (Stacey et al. 1991), a conclusion which is supported by our estimate in Sect. 3.4.3. The minimum PDR masses are calculated from the integrated 158 μm emission, assuming that the emission is optically thin, an assumption which we have shown to be correct in Paper I. The procedure is as follows. We obtain the effective emitting area Aeff by dividing the integrated 158 μm emission by the observed peak intensity. This peak intensity is inserted in Eqs. (7) to yield  . We then convert

. We then convert  into a gas mass

into a gas mass  , including a factor 1.3 to correct for helium. The results are given in Table 6. Again, the actual PDR masses may be a factor of two or more higher than the calculated

, including a factor 1.3 to correct for helium. The results are given in Table 6. Again, the actual PDR masses may be a factor of two or more higher than the calculated  in the more realistic case of finite temperature and density.

in the more realistic case of finite temperature and density.

In Table 6, we have also included the “virial mass”, calculated from the Galactic relation  (Solomon et al. 1987; but see also Maloney 1990). We find that the PDR masses suggested by the [C II] luminosities are very similar to these MVT masses (derived under the assumption of Milky Way conditions) in the case of the LMC, whereas they significantly exceed these CO-based masses in the SMC. In addition, this effect is most pronounced, in either Magellanic Cloud, for the very brightest H II regions: 30 Doradus in the LMC (MPDR/MVT = 2.8) and N 66 in the SMC (MPDR/MVT = 5.7). This is in striking contrast to the extragalactic sample of Stacey et al. (1991), where the derived ratios of

(Solomon et al. 1987; but see also Maloney 1990). We find that the PDR masses suggested by the [C II] luminosities are very similar to these MVT masses (derived under the assumption of Milky Way conditions) in the case of the LMC, whereas they significantly exceed these CO-based masses in the SMC. In addition, this effect is most pronounced, in either Magellanic Cloud, for the very brightest H II regions: 30 Doradus in the LMC (MPDR/MVT = 2.8) and N 66 in the SMC (MPDR/MVT = 5.7). This is in striking contrast to the extragalactic sample of Stacey et al. (1991), where the derived ratios of  (obtained using a “standard” conversion factor for CO, and are equivalent to our MPDR/MVT) are typically a few %, with a maximum of about 0.1. The LMC and SMC clouds observed with the KAO all exceed these values by one to two orders of magnitude. This remarkable difference suggests that in the LMC and the SMC molecular clouds are considerably under-luminous in CO for their masses, and that in addition in the brightest H II regions (30 Doradus, N66) a rather large fraction of the original molecular cloud mass has already been converted into a PDR (cf. Poglitsch et al. 1995). Indeed, in the LMC CO appears to be under-luminous by a factor of 3 − 6, and in the SMC by a factor of 15 − 60 (Israel et al. 1993; Israel 1997) so that actual molecular gas masses are expected to exceed the CO-derived “virial masses” by a similar factor. Thus, the KAO [C II] measurements indicate the presence of significant amounts of hydrogen, most likely in the form of H2, not traced by CO. A similar situation has been noted to occur in the magellanic irregular dwarf galaxy IC 10, where [C II] observations likewise points at such an H2 reservoir (Madden et al. 1997). The [C II] results confirm those derived by using thermal continuum emission from dust grains as a tracer for total (atomic + molecular) gas masses in the Magellanic Clouds (Israel 1997; Leroy et al. 2007, 2009).

(obtained using a “standard” conversion factor for CO, and are equivalent to our MPDR/MVT) are typically a few %, with a maximum of about 0.1. The LMC and SMC clouds observed with the KAO all exceed these values by one to two orders of magnitude. This remarkable difference suggests that in the LMC and the SMC molecular clouds are considerably under-luminous in CO for their masses, and that in addition in the brightest H II regions (30 Doradus, N66) a rather large fraction of the original molecular cloud mass has already been converted into a PDR (cf. Poglitsch et al. 1995). Indeed, in the LMC CO appears to be under-luminous by a factor of 3 − 6, and in the SMC by a factor of 15 − 60 (Israel et al. 1993; Israel 1997) so that actual molecular gas masses are expected to exceed the CO-derived “virial masses” by a similar factor. Thus, the KAO [C II] measurements indicate the presence of significant amounts of hydrogen, most likely in the form of H2, not traced by CO. A similar situation has been noted to occur in the magellanic irregular dwarf galaxy IC 10, where [C II] observations likewise points at such an H2 reservoir (Madden et al. 1997). The [C II] results confirm those derived by using thermal continuum emission from dust grains as a tracer for total (atomic + molecular) gas masses in the Magellanic Clouds (Israel 1997; Leroy et al. 2007, 2009).

In Paper I, we have shown that for all temperatures T > 11 K, the [C II] emission from the observed LMC sources is optically thin (τCII ≪ 1). By the same reasoning, this is also true for N 11 as well as the SMC clouds discussed in this paper. We also derived a lower limit to the [C II] excitation temperature by assuming the [C II] emission to be optically thick instead: ![\begin{equation} \texc=91.2\left[\ln\left({19.2\Delta V_5\over I_{-4}}+1\right)\right]^{-1}\; {\rm K} \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2011/07/aa16336-10/aa16336-10-eq208.png) (8)where 10-4I-4 erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1 is the integrated intensity of the 158 μm line. The peak intensities in N 11 and the SMC clouds are I-4 = 0.3 − 2.2, and so, with Δ5 ≈ 2 (Boreiko & Betz 1991), Eq. (8) gives Tex = 20 − 25 K. Again, these are lower limits to the actual gas kinetic temperature for two reasons: (a) the line is actually optically thin, and (b) the line may be sub-thermally excited. The densities in the emitting regions are probably high enough that the C + fine-structure levels are close to thermal equilibrium.

(8)where 10-4I-4 erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1 is the integrated intensity of the 158 μm line. The peak intensities in N 11 and the SMC clouds are I-4 = 0.3 − 2.2, and so, with Δ5 ≈ 2 (Boreiko & Betz 1991), Eq. (8) gives Tex = 20 − 25 K. Again, these are lower limits to the actual gas kinetic temperature for two reasons: (a) the line is actually optically thin, and (b) the line may be sub-thermally excited. The densities in the emitting regions are probably high enough that the C + fine-structure levels are close to thermal equilibrium.

4.3. Photoelectric heating efficiencies

The results presented in this paper confirm the conclusion from Paper I that the efficiency of grain photoelectric heating, as inferred from the measured values of FCII/FIR (Tables 3 and 5) is remarkably high for the observed LMC objects, with typical values of 1 − 5%, and somewhat lower but still high in the SMC, with typical values of 0.5 − 2%. We may use the inferred heating efficiency together with our earlier estimates of Go to estimate the gas densities in the emitting regions. In Paper I we have shown that the idealised analytical fit for the photoelectric heating efficiency ϵ as a function of Go, electron density ne, and gas temperature T given by Bakes & Tielens (1994),  (9)may be rewritten as an expression for the total hydrogen density, no:

(9)may be rewritten as an expression for the total hydrogen density, no:  (10)where ϵ-2 = ϵ/10-2, xC is the carbon abundance, and T2 = T/100, assuming that all electrons are supplied by carbon, and all carbon in the PDR zone is ionised. After substitution of the actual values of Go, xC, and ϵ-2, this simple model yields large values

(10)where ϵ-2 = ϵ/10-2, xC is the carbon abundance, and T2 = T/100, assuming that all electrons are supplied by carbon, and all carbon in the PDR zone is ionised. After substitution of the actual values of Go, xC, and ϵ-2, this simple model yields large values  K−1/2 for N159E, N159W. Significantly lower values

K−1/2 for N159E, N159W. Significantly lower values  K−1/2 are found for N160 and the N11 clouds. The Go values derived for the SMC have a large spread which is reflected by

K−1/2 are found for N160 and the N11 clouds. The Go values derived for the SMC have a large spread which is reflected by  ranging from 800 cm-3 K−1/2 to ≈ 20 000 cm-3 K−1/2 with a mean of ~ 4000 cm-3 K−1/2. As T2 is probably within a factor of two of unity, the implied range of gas densities is reasonable. In the case of N 159 we can verify this because Pineda et al. (2008) have also observed the region in various (sub)millimeter emission lines. Their detailed PDR modelling has yielded temperatures of ~ 80 K and densities of 104 cm-3, very close to the more crude estimate we have presented above.

ranging from 800 cm-3 K−1/2 to ≈ 20 000 cm-3 K−1/2 with a mean of ~ 4000 cm-3 K−1/2. As T2 is probably within a factor of two of unity, the implied range of gas densities is reasonable. In the case of N 159 we can verify this because Pineda et al. (2008) have also observed the region in various (sub)millimeter emission lines. Their detailed PDR modelling has yielded temperatures of ~ 80 K and densities of 104 cm-3, very close to the more crude estimate we have presented above.

Thus, there is no need to invoke the actually-existing differences in grain properties between the LMC, the SMC, and the Galaxy in order to explain the high photoelectric heating efficiencies. We note that some of our LMC FCII/FIR values exceed the maximum ϵ = 0.03 implied by Eq. (8). This is not a problem, as Bakes & Tielens (1994) show that more realistic models including small grains and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) allow higher heating efficiencies ≥ 0.05 for low values of Go (cf. their Fig. 13). The primary reason for the exceptionally large values of ϵ observed in the SMC and especially in the LMC is the relatively low values of Go characterising the emitting regions.

5. Discussion and conclusions

The Large and Small Magellanic Clouds present unique opportunities for studying star formation and the interstellar medium in environments very different from our own, with reasonably high spatial resolution. The observations presented here and in Paper I of a sample of bright H II regions in the LMC and the SMC highlight marked differences in the properties of the interstellar medium associated with these star-forming complexes. These differences result primarily from the lower metal abundances and dust-to-gas ratios of the SMC and the LMC with respect to the Galaxy and to each other.

All of the star-forming regions observed in the Magellanic Clouds show 158 μm line emission significantly enhanced relative to CO J = 1−0 emission (IC II/ICO = 1.5−10 × 104) as compared to the emission arising from star-forming molecular clouds in our own Galaxy (IC II/ICO = 0.1−1.4 × 104), or in the nuclei of IR-bright galaxies (IC II/ICO = 0.1−0.8 × 104 – see Stacey et al. 1991; Fixsen et al. 1999). There appears to be no significant difference between the LMC and the SMC in this respect. This behavior is caused by the relative constancy of the total C + column in a PDR if both the gas-phase carbon abundance and the dust-to-gas ratio are varied in the same way (e.g., van Dishoeck & Black 1988; Boreiko & Betz 1991; Maloney & Wolfire 1997), in contrast to a decrease in the CO column density when self-shielding is important (Maloney & Black 1988; van Dishoeck & Black 1988; Maloney & Wolfire 1997). In effect, in a low-metallicity molecular cloud the size of the CO-emitting core will shrink, so that the PDR will occupy a larger fraction of the total cloud volume (cf. Israel et al. 1986; Israel 1988; Bolatto et al. 1999; Röllig et al. 2006; Shetty et al. 2010). This is illustrated by the fact that the minimum masses in the PDR (calculated in the high-density, high-temperature limit) are a much larger fraction, by an order of magnitude, of the associated molecular gas mass (as inferred from CO) for the Magellanic Cloud regions than in Galactic star-forming regions. Thus, either these clouds are very under-luminous in CO compared to Galactic molecular clouds, or a much larger fraction of the mass of the molecular cloud has been photo-dissociated. The observation that the most intense H II regions in either Cloud (30 Doradus, N66) exhibit this effect most strongly suggests that both effects occur in tandem.

We have also established that the ratios of the 158 μm line to the far-infrared continuum – a measure of the efficiency of grain photoelectric heating – in the LMC and the SMC are unique in the sense that they are consistently higher than those seen elsewhere. They exceed, again by an order of magnitude, the FCII/FIR ratios seen in the star-forming regions of the Milky Way and M 33 (Higdon et al. 2003), although we should note that some star-forming regions in M 51 (Nikola et al. 2001) and M 31 (Rodriguez-Fernandez et al. 2006) have ratios (FCII/FIR = 1−2%) similar to those in the SMC. The global FCII/FIR ratios of the Milky Way (Fixsen et al. 1999) and indeed those of some 60 other galaxies observed by ISO (Malhotra et al. 2004; Negishi et al. 2004) are much lower, with FCII/FIR = 0.2−0.8 %. The large implied efficiencies, of the order of 1−2%, can be understood as the result of relatively normal PDR gas densities (no ~ 103−104) combined with unusually low values of the ambient FUV photon flux, Go = 30−350. The underlying cause of such low values of Go again is low metallicity and dust content of the Clouds, which provides UV photons with a relatively long mean free path length. In such environments, the sphere of influence of an FUV photon source is much larger than in environments with solar metallicities, and the geometric dilution of the radiation field is correspondingly larger.

Although one might expect that the more metal-poor SMC would have even higher FCII/FIR ratios than the LMC, this is not the case; they are on average a factor of 2−3 lower. We also note that the Go values derived for the SMC from emission by ionised gas are a factor of 3−4 higher than those derived from emission by dust whereas the two are essentially the same for the LMC. As the [C II] heating appears to be dominated by PAH particles (Helou et al. 2001; Rubin et al. 2009), we ascribe these differences to the combined effect of greater geometric dilution of the radiation field which increases gas heating efficiencies, and at the same time lower gas heating rates by the very low PAH abundances in the SMC (Sandstrom et al. 2010). The galaxy IC 10 has metallicities and PAH abundances in between those of the LMC and SMC (see Wiebe et al. 2011). Its [C II]-related ratios (Madden et al. 1997) are indistinguishable from those of the LMC and SMC (Fig. 5). This suggests that the combined effects of dust and PAH abundances cause low-metallicity galaxies to have rather similar [C II] , CO and FIR ratios largely independent of actual metallicity.

Go is the radiation field intensity in units of 1.6 × 10-3 erg cm-2 s-1 (i.e., the strength of the Solar Neighbourhood interstellar radiation field: Habing 1968).

Acknowledgments

It is a pleasure to thank the MPE FIFI personnel, notably Sue Madden, Albrecht Poglitsch and Gordon Stacey, without whose generous help and support the observations described in this paper could not have been obtained. We also thank the KAO crew for their unfailing support under sometimes difficult flight conditions. P.R.M. acknowledges support through the NASA Long Term Astrophysics Program under grant NAGW-4454, support from the NSF through grant AST-0705157 and support from NASA through grant 1394366. He would also like to thank the Netherlands Organisation for Pure Research (N.W.O.) for support for visits to Leiden to work on this project.

References

- Abel, N. P., Ferland, G. J., Shaw, G., & van Hoof, P. A. M. 2005, ApJS, 161, 65 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bakes, E. L. O., & Tielens, A. G. G. M. 1994, ApJ, 427, 822 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Barbá, R. H., Rubio, M., Roth, M. R., & García, J. 2003, AJ, 125, 1940 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlin, R. C., Savage, B. D., & Drake, J. F. 1978, ApJ, 224, 132 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bolatto, A. D., Jackson, J. M., & Ingalls, J. G. 1999, ApJ, 513, 275 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bolatto, A. D., Leroy, A., Israel, F. P., & Jackson, J. M. 2003, ApJ, 595, 167 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Boreiko, R. T., & Betz, A. L. 1991, ApJ, 380, L27 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchet, P., Lequeux, J., Maurice, E., Prevot, L., & Prevot-Burnichon, M. L. 1985, A&A, 149, 330 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan, J., Ye, T., Deharveng, L., Turtle, A. J., & Kennicutt, R. C. 1996, A&A, 307, 403 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Contursi, A., Lequeux, J., Cesarsky, D., et al. 2000, A&A, 362, 310 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Copetti, M. V. F. 1990, A&A, 229, 533 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Cornett, R. H., Greason, M. R., Hill, J. K., et al. 1997, AJ, 113, 1011 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, M. K., Genzel, R., Townes, C. H., & Watson, D. M. 1985, ApJ, 291, 755 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, R. D., Elliott, K. H., & Meaburn, J. 1976, MmRAS, 81, 89 [Google Scholar]

- Evans, C. J., Lennon, D. J., Smartt, S. J., & Trundle, C. 2006, A&A, 456, 623 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Filipović, M. D., Jones, P. A., White, G. L., & Haynes, R. F. 1998, A&AS, 130, 441 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick, E. L. 1985, ApJ, 299, 219 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen, D. J., Bennett, C. L., & Mather, J. C. 1999, ApJ, 526, 207 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gouliermis, D. A., Dolphin, A. E., Brandner, W., & Henning, Th. 2006, ApJS, 166, 549 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gouliermis, D. A., Chu, Y.-H., Henning, Th., et al. 2008, ApJ, 688, 1050 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gouliermis, D. A., Bestenlehner, J. M., Brandner, W., & Thenning, Th. 2010, A&A, 515, 56 [Google Scholar]

- Habing, H. J. 1968, BAN, 19, 421 [Google Scholar]

- Hatano, H., Kadowaki, R., Nakajima, Y., et al. 2006, AJ, 132, 2653 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Henize, K. G. 1956, ApJS, 2, 315 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hennekemper, E., Gouliermis, D. A., Henning, Th., & Brandner, W. 2008, ApJ, 672, 914 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Heydari-Malayeri, M., & Testor, G. 1983, A&A, 118, 116 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Heydari-Malayeri, M., Niemela, V. S., & Testor, G. 1987, A&A, 184, 300 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Heydari-Malayeri, M., Charmandaris, V., Deharveng, L., et al. 2001, A&A, 372, 527 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Higdon, S. J. U., Higdon, J. L., van der Hulst, J. M., & Stacey, G. J. 2003, ApJ, 592, 161 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenbach, D. J., & Tielens, A. G. G. M. 1997, ARA&A, 35, 179 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenbach, D. J., Takahashi, T., & Tielens, A. G. G. M. 1991, ApJ, 377, 192 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Howe, J. E., Jaffe, D. T., Genzel, R., & Stacey, G. J. 1991, ApJ, 373, 158 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchings, J. B., & Thompson, I. B. 1988, ApJ, 331, 294 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ingalls, J. G., Reach, W. T., & Bania, T. M. 2002, ApJ, 579, 289 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [MathSciNet] [Google Scholar]

- Israel, F. P. 1997, A&A, 328, 471 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Israel, F. P. 1988, in Millimetre and Submillimetre Astronomy, ed. R. D. Wollstencroft, & W. B. Burton (Dordrecht: Kluwer), 281 [Google Scholar]

- Israel, F. P., de Graauw, Th., Lidholm, S., van de Stadt, H., & de Vries, C. P. 1986, ApJ, 304, 86 [Google Scholar]

- Israel, F. P., Johansson, L. E. B., Lequeux, J., et al. 1993, A&A, 276, 25 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Israel, F. P., Maloney, P. R., Geis, N., et al. 1996, ApJ, 465, 738 (Paper I) [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Israel, F. P., de Graauw, Th., Johansson, L. E. B., et al. 2003a, A&A, 401, 99 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Israel, F. P., Johansson, L. E. B., Rubio, M., et al. 2003b, A&A, 406, 817 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe, D. T., Zhou, S., Howe, J. E., et al. 1994, ApJ, 436, 203 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, L. E. B., Greve, A., Booth, R. S., et al. 1998, A&A, 331, 857 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, M. J., Wolfire, M. G., Hollenbach, D. J., & Luhman, M. L. 1999, ApJ, 527, 795 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, M. J., Wolfire, M. G., & Hollenbach, D. J. 2006, ApJ, 644, 283 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Leroy, A., Bolatto, A., Stanimirovic, S., et al. 2007, ApJ, 658, 1027 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Leroy, A., Bolatto, A., Bot, C., et al. 2009, ApJ, 702, 352 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lucke, P. B., & Hodge, P. W. 1970, AJ, 75, 171 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mac Low, M.-M., Chang, T. H., Chu, Y.-H., et al. 1998, ApJ, 493, 260 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Madden, S. C., Poglitsch, A., Geis, N., Stacey, G. J., & Townes, C. H. 1997, ApJ, 483, 200 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [MathSciNet] [Google Scholar]

- Maddox, L. A., Williams, R. M., Dunne, B. C., & Chu, Y.-H. 2009, ApJ, 699, 911 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, S., Kaufman, M. J., Hollenbach, D., et al. 2001, ApJ, 561, 766 [Google Scholar]

- Maloney, P. R. 1990, ApJ, 348, L9 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney, P. R., & Black, J. H. 1988, ApJ, 325, 389 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney, P. R., & Wolfire, M. G. 1997, in CO: Twenty-Five Years of Millimeter-Wave Spectroscopy, ed. W.B. Latter, S. J. E. Radford, P. R. Jewell, J. G. Mangum, & J. Bally (Dordrecht: Reidel), IAU Symp., 170, 299 [Google Scholar]

- Massey, P., Parker, J. W., & Garmany, C. D. 1989, AJ, 98, 1305 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Meaburn, J., Solomos, S., Laspias, V., & Goudis, C. 1989, A&A, 225, 497 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Mills, B. Y., & Turtle, A. J. 1984, in Structure and Evolution of the Magellanic Clouds, ed. S. van den Bergh, & K. S. de Boer (Dordrecht: Reidel), IAU Symp., 108, 283 [Google Scholar]

- Mochizuki, K., Nakagawa, T., Doi, Y., et al. 1994, ApJ, 430, L37 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mokiem, M. R., de Koter, A., Evans, C. J., et al. 2007, A&A, 465, 1039 [Google Scholar]

- Nazé, Y., Chu, Y.-H., Points, S. D., et al. 2001, AJ, 122, 921 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nazé, Y., Antokhin, I. I., Rauw, G., et al. 2004, A&A, 424, 727 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Negishi, T., Onaka, T., Chan, K.-W., & Röllig, T. L. 2001, A&A, 375, 566 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Nikola, T., Geis, N., Herrmann, F., et al. 2001, ApJ, 561, 203 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pagel, B. E. J. 2003, in CNO in the universe, ed. C. Charbonnel, D. Schaerer, & G. Meynet, ASP Conf. Ser., 304, 187 [Google Scholar]

- Pak, S., Jaffe, D. T., van Dishoeck, E. F., Johansson, L. E. B., & Booth, R. S. 1998, ApJ, 498, 735 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Parker, J. W., Garmany, C. D., Massey, P., & Walborn, N. R. 1992, AJ, 103, 1205 [Google Scholar]

- Pineda, J. L., Mizuno, N., Stutzki, J., et al. 2008, A&A, 482, 197 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Poglitsch, A., Beeman, J. W., Geis, N., et al. 1991, Int. J. Infrared Millimeter Waves, 12, 859 [Google Scholar]

- Poglitsch, A., Krabbe, A., Madden, S. C., et al. 1995, ApJ, 454, 293 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Fernandez, N. J., Braine, J., Brouillet, N., & Combes, F. 2006, A&A, 453, 77 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Röllig, M., Ossenkopf, V., Jeyakumar, S., Stutzki, J., & Sternberg, A. 2006, A&A, 451, 917 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Rosado, M., Laval, A., Le Coarer, E., et al. 1996, A&A, 308, 588 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, D., Hony, S., Madden, S. C., et al. 2009, A&A, 494, 647 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, M., Lequeux, J., Boulanger, F., et al. 1993, A&A, 271, 1 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, M., Lequeux, J., Boulanger, F., et al. 1996, A&AS, 118, 263 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, M., Contursi, A., Lequeux, J., et al. 2000, A&A, 359, 1139 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbi, E., Sirianni, M., Nota, A., et al. 2007, AJ, 133, 44 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sandstrom, K. M., Bolatto, A. D., Draine, B. T., Bot, C., & Stanimirović, S. 2010, ApJ, 715, 701 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [MathSciNet] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer, B. E. 2008, AJ, 135, 112 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schwering, P. B. W. 1988, Ph.D. Thesis Leiden University [Google Scholar]

- Schwering, P. B. W., & Israel, F. P. 1990, Atlas and Catalogue of Infrared Sources in the Magellanic Clouds (Dordrecht: Kluwer) [Google Scholar]

- Shetty, R., Glover, S. C., Dullemond, C., & Klessen R. S. 2011 MNRAS, 412, 1686 [Google Scholar]

- Simon, J. D., Bolatto, A. D., Whitney, B. A., et al. 2007, ApJ, 669, 327 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey, G. J., Geis, N., Genzel, R., et al. 1991, ApJ, 373, 423 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey, G. J., Beeman, J. W., Haller, E. E., et al. 1992, Int. J. Infrared Millimeter Waves, 13, 1689 [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, P. M., Rivolo, A. R., Barrett, J. W., & Yahill, A. M. 1987, ApJ, 319, 730 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Szewczyk, O., Pietrzyński, G., Gieren, W., et al. 2009, AJ, 138, 1661 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Testor, G. 2001, A&A, 372, 667 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Testor, G., & Lortet, M.-C. 1987, A&A, 178, 25 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Testor, G., & Pakull, M. 1985, A&A, 145, 170 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Testor, G., Lemaire, J. L., Heydari-Malayeri, M., et al. 2010, A&A, 510, 95 [Google Scholar]

- Tielens, A. G. G. M., & Hollenbach, D. J. 1985a, ApJ, 291, 722 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tielens, A. G. G. M., & Hollenbach, D. J. 1985b, ApJ, 291, 747 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- van Dishoeck, E. F., & Black, J. H. 1988, ApJ, 334, 771 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- van Loon, J. Th., Oliveira, J. M., Gordon, K. D., Sloan, G. C., & Engelbracht, C. W. 2010, ApJ, 139, 1553 [Google Scholar]

- Walborn, N. R., & Blades, J. C. 1986, ApJ, 304, L17 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Walborn, N. R., & Parker, J. W. 1992, ApJ, 399, L87 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wiebe, D. S., Egorov, O. V., & Lozinskaya, T. A. 2011, Astron. Rep., accepted [arXiv:1102.1060] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfire, M. G., Hollenbach, D., & Tielens, A. G. G. M. 1989, ApJ, 344, 770 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfire, M. G., Tielens, A. G. G. M., & Hollenbach, D. 1990, ApJ, 358, 116 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wright, E. L., Mather, J. C., Bennett, C. L., et al. 1991, ApJ, 381, 200 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ye, T., Turtle, A. J., & Kennicutt, R. C. 1991, MNRAS, 249, 722 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

All Tables

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Map of the central part of LMC-N 11. [C II] contours are linear at multiples of 2.125 × 10-5 erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1. Integrated J = 1−0 12CO emission is represented by grayscales in the range 1−10 K km s-1. Small dots mark the grid points sampled in [C II]. The locations of the major H II region components N 11A through N 11F are schematically indicated. All [C II] peaks (marked by their number from Tables 2 and 3) are associated with a CO cloud. The lack of CO emission near [C II] cloud 4 may reflect poor sampling of the CO map at this position. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Map of SMC-N 66. [C II] contours are linear at multiples of 1.0 × 10-5 erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1. Integrated J = 2 − 1 12CO emission is represented by grayscales in the range 0.5 − 5.0 K km s-1. The locations of the N 66 bar, the bright H II component N 66A, and the CO “plume” are indicated. Brightest [C II] and CO emission occurs just off N 66A near position (0, 0). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 Map of SMC-N 83/N 84/N 85. [C II] contours are linear at multiples of 1.0 × 10-5 erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1. Integrated J = 1−0 12CO emission is represented by grayscales in the range 0.5−4.5 K km s-1. The positions of the (mostly compact) H II regions in the complex are marked. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4 Left: [C II] Map of SMC-N 25 field. Contours are linear at multiples of 0.72 × 10-5 erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1. Integrated J = 1−0 12CO emission is represented by grayscales in the range 0.5−5.0 K km s-1. Center: [C II] Map of SMC-N 27 field. Contours are linear at multiples of 1.35 × 10-5 erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1. The positions of the H II regions N27, N27-S, and N 19 are indicated. Integrated J = 1−0 12CO emission is represented by grayscales in the range 1.0−13.0 K km s-1. Right: [C II] map of SMC-N 88 field. Contours are linear at multiples of 0.72 × 10-5 erg cm-2 s-1 sr-1. Integrated J = 1−0 12CO emission is represented by grayscales in the range 0.2−2.4 K km s-1. |

| In the text | |

|