| Issue |

A&A

Volume 529, May 2011

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A114 | |

| Number of page(s) | 10 | |

| Section | The Sun | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201015614 | |

| Published online | 14 April 2011 | |

About the relative importance of compressional heating and current dissipation for the formation of coronal X-ray bright points

1

Max-Planck-Institut für Sonnensystemforschung, 37191 Katlenburg-Lindau, Germany

e-mail: javadi@mps.mpg.de

2

Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, AK 99775, USA

Received: 19 August 2010

Accepted: 5 February 2011

Context. The solar corona is heated to high temperatures of the order of 106 K. The coronal energy budget and specifically possible mechanisms of coronal heating (wave, DC-electric fields, etc.) are poorly understood. This is particularly true for the formation of X-ray bright points (BPs) is concerned.

Aims. We aim to investigate the energy budget, particularly the relative role and contribution of adiabatic compression versus current dissipation to the formation of coronal BPs.

Methods. Our three-dimensional resistive MHD simulation starts with the extrapolation of the observed magnetic field from SOHO/MDI magnetograms, which are associated with a BP observed on 19 December 2006 by Hinode. The initial radially non-uniform plasma density and temperature distribution agrees with an equilibrium model of the chromosphere and corona. The plasma motion is included in the model as a source of energy for coronal heating.

Results. Our investigation of the energy conversion owing to Lorentz force, pressure gradient force, and Ohmic current dissipation for this bright point shows the minor effect of Joule heating compared with the work done by pressure gradient force in increasing the thermal energy by adiabatic compression. Especially at the time when the temperature enhancement above the bright point starts to form, compressional effects are quite dominant over the direct Joule heating.

Conclusions. Choosing non-realistic high resistivity in compressible MHD models for a simulation of solar corona can lead to unphysical consequences for the energy balance analysis, especially when local thermal energy enhancements are being considered.

Key words: Sun: atmosphere / Sun: magnetic topology / magnetohydrodynamics (MHD) / methods: numerical / Sun: corona

© ESO, 2011

1. Introduction

The mechanisms of coronal heating are not well understood. A particular object for studying heating processes are coronal bright points (BPs). Owing to the increasing accuracy of the observations, our knowledge about BPs has greatly advanced from the time of their discovery in soft X-ray images by Vaiana et al. (1970). According to X-ray and EUV observations, the linear size of BPs is on average about 30–40 arcsec with typically an embedded bright core of about 5–10 arcsec, see Madjarska et al. (2003). The average lifetime of X-ray BPs is about 8 h according to Golub et al. (1974) and 20 h for EUV BPs, see Zhang et al. (2001). It has been known for a long time that BPs are associated with small bipolar magnetic features in the photosphere (Krieger et al. 1971; Brown et al. 2001). About one third of the BPs lie over emerging regions of magnetic flux, while the rest of them lie above moving magnetic features. This was a base for the “cancelling magnetic feature” (CMF) model by Priest et al. (1994). Lifetime and energy release of BPs are known to be closely related to the different phases of the motion of this photospheric magnetic feature, according to Brown et al. (2001). First theories were mainly addressing the topology of the magnetic field below BPs (e.g., Parnell et al. 1994; Longcope 1998). Using higher resolution and cadence observations of the BP’s intensity and taking into account a more comprehensive patterns of motion in particular in regions with highly divergent magnetic field, Brown et al. (2001) could associate different patterns of motion of the solar photospheric magnetic features with different stages of a BP evolution. The plasma motion in the regions of strong magnetic fields was first included by Büchner (2004a,b) in his three-dimensional numerical resistive MHD model, using his 3D numerical simulation model, LINMOD3d. This considers the dissipation of currents generated by plasma motion in the photosphere on time scales longer than an Alfvén time as a one of the heating processes in the solar corona, according to Parker (1972). Caused current dissipation by anomalous resistivity in their model according to (Büchner & Elkina 2005, 2006), which causes Joule heating. Because LINMOD3d considers the compressibility of the plasma, the resulting heating could also be caused by compressional effects. Later two-dimensional MHD simulation studies were carried out by von Rekowski & Hood (2006, 2008b,a). These authors used an analytical initial equilibrium and imposed a magnetic flux footpoint motion to model the heating of coronal bright points as if they were caused by cancelling magnetic features. To obtain the desired heating rate, they used an enhanced resistivity for which the values were above the theoretically justifiable resistivity. This raises the general question of the energy budget and the energy conversion in solar flux tubes. Even with low resistivity, current simulations are unable to resolve the diffusion regions of reconnection and thus overestimate Joule heating. It is unresolved as well how much heating is caused by pressure gradient forces.

To clarify these questions we continued the work of Büchner et al. (2004b,c,a); Büchner (2006, 2007); Santos & Büchner (2007) and Santos et al. (2008). These authors demonstrated the formation of localized current sheets in and above the transition region at the position of a EUV BPs as a result of photospheric plasma motion. Our study extend their results through a systematic study of the energy conversion and budget in magnetic flux tubes. The investigation uses the 3D simulation model LINMOD3d to simulate the solar atmosphere in the region of an X-ray BP observed by the Hinode spacecraft on 19 December 2006 between 22.17 UT and 22.22 UT.

In Sect. 2 we briefly review the main features of the numerical simulation model LINMOD3d. In Sect. 3 we describe the specific simulation setup used in our study, and Sect. 4 provides some simulation results for the chosen BP data. In Sect. 5 we present the results of energy budget analysis by investigating the role of different forces and in Sect. 6 we summarize and discuss our results.

2. Simulation model

Our simulation model uses the approach of the LINMOD3d code (Büchner et al. 2004b,c,a). This means that the initial magnetic field is obtained by extrapolating the observed photospheric line-of-sight (LOS) magnetic fields. The initial plasma distribution is non-uniform, containing a dense and cool chromosphere as well as the transition to a rarefied and hot corona. The photospheric driving is switched on by coupling the chromospheric plasma with a moving background-neutral gas. Some details of our code are given briefly in the following subsection.

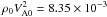

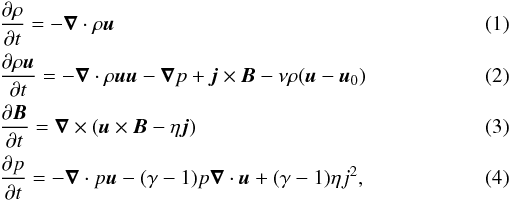

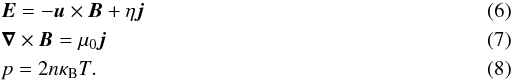

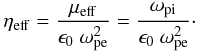

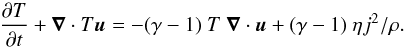

2.1. Equations

In our study we solve this set of MHD equations:  where ρ and u are plasma density and velocity, B is the magnetic field and P is the thermal pressure. A plasma-neutral gas coupling in the photosphere and the chromosphere is included through the collision term in the momentum equation, where u0 denotes the neutral gas velocity. The neutral gas serves as a frictional background to communicate photospheric footpoint motion to the plasma and magnetic field through frictional interaction. It also leads to a reflection of coronal Alfvén waves back to the corona from the transition region, so that the influence of coronal Alfvén waves can be neglected at the photospheric boundary. In order to set the plasma in motion, a number of incompressible flow eddies is used according to observed horizontal drifts in the photosphere ∇·u0 = 0 is imposed via the neutral gas, where u0 is dependent in x and y. It is constant along z and derived from a potential using u0 = ∇ × (Uez), with

where ρ and u are plasma density and velocity, B is the magnetic field and P is the thermal pressure. A plasma-neutral gas coupling in the photosphere and the chromosphere is included through the collision term in the momentum equation, where u0 denotes the neutral gas velocity. The neutral gas serves as a frictional background to communicate photospheric footpoint motion to the plasma and magnetic field through frictional interaction. It also leads to a reflection of coronal Alfvén waves back to the corona from the transition region, so that the influence of coronal Alfvén waves can be neglected at the photospheric boundary. In order to set the plasma in motion, a number of incompressible flow eddies is used according to observed horizontal drifts in the photosphere ∇·u0 = 0 is imposed via the neutral gas, where u0 is dependent in x and y. It is constant along z and derived from a potential using u0 = ∇ × (Uez), with  (5)Note that the contour lines of this function are streamlines of the flow. The magnitudes of velocity scale with u00/L0 and u00/L1, chosen in accordance with the observed plasma motion in the photosphere. In our simulation we approximated the observed motion by three vortices with amplitudes of the velocity u00 equal to 5.5, 5, and 2 km s-1, respectively. The values of c0, L0, c1, and L1 are 9, 6, 51, and 6 Mm for the first vortex 5, 6, 28, and 6 Mm for the second and 19, 7, 38, and 7 Mm for the third vortex. The height-dependent collision frequency ν is chosen to be sufficiently high only below the transition region. This way the plasma is forced to move in the chromosphere dragged by the neutral gas, but not above the transition region. This way the horizontal motion generates a Poynting flux into the corona. On the other hand the collision frequency is chosen in a way that coronal Alfvén waves are properly reflected, while the wave perturbations in the chromosphere are heavily damped by the frictional interaction with the neutral background. Our choice of equations means that in this study we do not consider energy losses caused by radiation and heat conduction, and we also excluded the action of the solar gravitation in this study. The system of equations is closed by Ohm’s and Ampère’s laws, and the temperature is defined via the ideal gas law for a fully ionized plasma:

(5)Note that the contour lines of this function are streamlines of the flow. The magnitudes of velocity scale with u00/L0 and u00/L1, chosen in accordance with the observed plasma motion in the photosphere. In our simulation we approximated the observed motion by three vortices with amplitudes of the velocity u00 equal to 5.5, 5, and 2 km s-1, respectively. The values of c0, L0, c1, and L1 are 9, 6, 51, and 6 Mm for the first vortex 5, 6, 28, and 6 Mm for the second and 19, 7, 38, and 7 Mm for the third vortex. The height-dependent collision frequency ν is chosen to be sufficiently high only below the transition region. This way the plasma is forced to move in the chromosphere dragged by the neutral gas, but not above the transition region. This way the horizontal motion generates a Poynting flux into the corona. On the other hand the collision frequency is chosen in a way that coronal Alfvén waves are properly reflected, while the wave perturbations in the chromosphere are heavily damped by the frictional interaction with the neutral background. Our choice of equations means that in this study we do not consider energy losses caused by radiation and heat conduction, and we also excluded the action of the solar gravitation in this study. The system of equations is closed by Ohm’s and Ampère’s laws, and the temperature is defined via the ideal gas law for a fully ionized plasma:  The value of the resistivity η is varied in accordance with three models described in Sect. 2.3. The MHD equations are discretized by means of a second order weakly dissipative Leapfrog scheme. Owing to stability reasons the induction equation is discretized using Dufort-Frankel scheme, according to Potter (1973).

The value of the resistivity η is varied in accordance with three models described in Sect. 2.3. The MHD equations are discretized by means of a second order weakly dissipative Leapfrog scheme. Owing to stability reasons the induction equation is discretized using Dufort-Frankel scheme, according to Potter (1973).

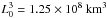

2.2. Simulation box and normalization

The lower boundary of the simulation box is a horizontal square in the photosphere sized 46.4 × 46.4 Mm2. The simulation box extends 15.45 Mm toward the corona. A nonuniform grid in the z direction supplies the proper resolution of the transition layer, where the grid distance Δz corresponds to 160 km, Büchner et al. (2004b). This corresponds to 64 grid points in z direction, while in the x, y plane a 128 × 128 grid is used. We solve for dimensionless variables that are normalized to natural scales as listed in Table 1. Note that the maximum imposed velocity of the neutral gas is lower than 5 km s-1, while the typical (normalizing) electron thermal velocity is vthe = 1470 km s-1 and the Alfvén speed is vA = 50 km s-1. Hence, one can be certain that the inserted neutral gas motion is a gentle, sub-Alfvénic and sub-slow velocity.

2.3. Resistivity models

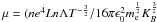

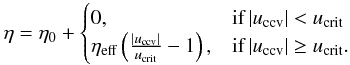

To verify the influence of different resistivity models on the BP plasma heating, we solved the equations for the same initial and boundary conditions, but varying the resistivity model. The resistivity η can be expressed via an effective collision frequency μ as  , where ωpe is the electron plasma frequency (

, where ωpe is the electron plasma frequency ( ). In our model we always applied a constant physically justified background resistivity η0, which exceeds the numerical resistivity. It is appropriate to chose for effective collision frequency of the background resistivity the Spitzer (1962) value

). In our model we always applied a constant physically justified background resistivity η0, which exceeds the numerical resistivity. It is appropriate to chose for effective collision frequency of the background resistivity the Spitzer (1962) value  ). Based on the typical plasma parameters of our model, we chose for the collision-driven background resistivity η0 = 10-4 (in normalized units). In two models we added anomalous resistivity in places where either the current density of the current carrier velocity (uccv determined as the current density divided by the charge density) exceeds a physically justified threshold of micro-instabilities.

). Based on the typical plasma parameters of our model, we chose for the collision-driven background resistivity η0 = 10-4 (in normalized units). In two models we added anomalous resistivity in places where either the current density of the current carrier velocity (uccv determined as the current density divided by the charge density) exceeds a physically justified threshold of micro-instabilities.

Normalization values.

In the first resistivity model the anomalous resistivity is added when the current carrier velocity uccv exceeds a critical velocity (Roussev et al. 2002; Büchner & Elkina 2005)

(9)A natural choice for the threshold velocity is the electron thermal velocity vthe, which corresponds to 1470 km s-1 with our normalizing quantities or to 5.8 × 10-4 in normalized units. In the first resistivity model we chose 5 × 10-2 to follow the ideal evolution of the plasma as long as possible. The additional term for resistivity can be estimated e.g., for a nonlinear ion- acoustic instability (Büchner & Elkina 2006) as

(9)A natural choice for the threshold velocity is the electron thermal velocity vthe, which corresponds to 1470 km s-1 with our normalizing quantities or to 5.8 × 10-4 in normalized units. In the first resistivity model we chose 5 × 10-2 to follow the ideal evolution of the plasma as long as possible. The additional term for resistivity can be estimated e.g., for a nonlinear ion- acoustic instability (Büchner & Elkina 2006) as

(10)Here ωpi denotes the plasma ion frequency

(10)Here ωpi denotes the plasma ion frequency  . For the typical parameters of our simulation this estimate would reveal η = 2.5, i.e. a magnetic Reynolds number of less than unity. In this case many current sheets would immediately diffuse. But because the plasma β is relatively large for our simulation parameters, obliquely propagating waves would be present in the spectrum of the micro-turbulence. Then the estimate of the effective collision frequency has to take into account lower hybrid waves (Silin et al. 2005). For our normalizing values this results in ηeff = 0.03.

. For the typical parameters of our simulation this estimate would reveal η = 2.5, i.e. a magnetic Reynolds number of less than unity. In this case many current sheets would immediately diffuse. But because the plasma β is relatively large for our simulation parameters, obliquely propagating waves would be present in the spectrum of the micro-turbulence. Then the estimate of the effective collision frequency has to take into account lower hybrid waves (Silin et al. 2005). For our normalizing values this results in ηeff = 0.03.

In a second model calculation we considered a current density-dependent resistivity used before by e.g., Neukirch et al. (1997), in which the resistivity increases even stronger (quadratic dependence) after the current density exceeds a critical value jcrit:

(11)The critical current density is related to the critical velocity via jcrit = e ne ucrit. Here we will report the results of our simulations obtained according to the second model for which we chose a threshold as low as jcrit = 0.69 to discuss the consequences of an early addition of anomalous resistivity. For comparison we solved the problem also by assuming for a third model a constant enhanced uniform resistivity, as is usually done in global MHD simulations.

(11)The critical current density is related to the critical velocity via jcrit = e ne ucrit. Here we will report the results of our simulations obtained according to the second model for which we chose a threshold as low as jcrit = 0.69 to discuss the consequences of an early addition of anomalous resistivity. For comparison we solved the problem also by assuming for a third model a constant enhanced uniform resistivity, as is usually done in global MHD simulations.

Concerning the values of the chosen ηeff, the width of the actual current sheets in which turbulence effectively operates is on the order of the ion inertial scale  . This scale cannot be resolved in any realistic 3D MHD simulation of the solar corona. In order to introduce micro-turbulent anomalous resistivity, the threshold velocity (– current density) has to be upscaled to the actual resolution of the simulation by a factor of 5 × 104. For the same reason the resistive electric field builds up in very (perhaps di-) thin current sheets. To consider the correct values of the electric field on the much coarser MHD-simulation grid, the anomalous resistivity used in the simulation has also to be scaled up by the above scaling factor. This approach allows us to consider the correct amount of Joule heating.

. This scale cannot be resolved in any realistic 3D MHD simulation of the solar corona. In order to introduce micro-turbulent anomalous resistivity, the threshold velocity (– current density) has to be upscaled to the actual resolution of the simulation by a factor of 5 × 104. For the same reason the resistive electric field builds up in very (perhaps di-) thin current sheets. To consider the correct values of the electric field on the much coarser MHD-simulation grid, the anomalous resistivity used in the simulation has also to be scaled up by the above scaling factor. This approach allows us to consider the correct amount of Joule heating.

2.4. Initial and boundary conditions

We first carried out a potential field extrapolation to the Fourier decomposed normal field component of the magnetic field taken from the MDI-observation. The resulting 3D magnetic configuration is used as the initial condition of the simulation code. In the potential field approximation the normal field component is related to (Bx,By) through ∇·B = 0 and ∇ × B = 0. The initial density and temperature height profiles for the plasma are taken in accordance with the VAL model, which assumes pressure being in a hydrostatic equilibrium. The simulation box has six boundaries: four lateral, one top and one bottom boundaries. For the side boundaries a line symmetric boundary condition is used with the line symmetry with respect to the centers of the sides of the simulation box, Otto et al. (2007). For the upper boundary the derivatives in the normal direction are put to zero. At the lower boundary the normal velocity is set to be zero, while the tangential velocity is taken from the neutral motion.

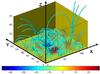

3. Simulation setup

Our study is based on an X-ray BP observed by the XRT X-ray telescope onboard the Hinode spacecraft on 19 December 2006. The corresponding X-ray image is shown in Fig. 1. For the initial magnetic field we used the observed line-of-sight (LOS) component of the photospheric magnetic field taken by the Michelson Doppler Interferometer MDI onboard the Soho spacecraft at 22:17 UT. We chose data from a field of view with the horizontal size of 64 × 64 arcsec2, which properly covers the magnetic features associated with this BP (insert in Fig. 1). We use the LOS component as the initial normal field component at the lower boundary of our simulation box, the photosphere, because the BP observation was made close to the center of the solar disk.

|

Fig. 1 X-ray image taken from XRT/Hinode on 19 December 2006 at 22:08 UT. Insert: the LOS component of the photospheric magnetic field in a 64 × 64 arcsec2 horizontal plane taken from MDI/Soho, where white (black) spots correspond to upward (downward) directed line-of-sight components of the photospheric magnetic field. The BP and the related magnetic field feature are indicated in the images. |

Fourier filtering was applied to the LOS component of the magnetic field. By taking into account only the first eight Fourier modes, details of the magnetic field structure that are smaller that 6 Mm are neglected. The extension of structures arising from smaller scale magnetic features would not extend higher up into the corona, they are dissipated at an early stage of the evolution in the highly collisional chromospheric plasma.

|

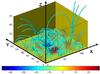

Fig. 2 Potential magnetic field extrapolated from the filtered MDI magnetograms and used as initial configuration for the magnetic field in our simulation. The blue lines show the magnetic field lines. The color code depicts the LOS component of the magnetic field. Note that axes here are in terms of grid points, 64 in z direction and 128 × 128 in x, y plane. This corresponds to 15.45 Mm at z direction and 46.4 Mm at x and y directions. |

Figure 2 shows a three-dimensional view of the magnetic field extrapolated from the photospheric boundary for the magnetic field observed at 22:17 UT on December 19, 2006. The blue lines show the magnetic field lines. The color code depicts the LOS component of the photospheric magnetic field. Magnetic fields directed upward from the photosphere are colored in red, downward directed in blue.

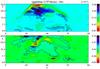

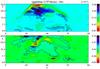

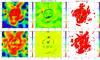

With the chosen normalization length of L0 = 500 km, the box size in x and y direction correspond to 92.8 L0 and the z direction extend to 30.9 L0. The photospheric plasma velocities are obtained by applying the local-correlation-tracking (LCT) method by November & Simon (1988) to the Fourier-filtered LOS magnetic component of the photospheric magnetic field observed between 22:17 UT and 22:22 UT. The left panel of Fig. 3 shows the velocity pattern obtained by the LCT method. For the simulation we used incompressible velocity vortices to mimic the observed velocity pattern, as shown in the right panel of Fig. 3. The interval chosen for the simulation starts a few hours after the time the BP first appeared in the X-ray images, and the bright point continues to glow a few more hours afterwards. During the whole simulation time interval the relative shear motion of the two main magnetic flux concentrations of opposite polarity is negligible.

|

Fig. 3 Horizontal plasma velocities in the photosphere. Left panel: velocities obtained by applying LCT technique to MDI magnetograms between 22:17 and 22:22 UT. The right panel shows the vortices that are used to approximate this motion in the simulation. The panels are showing the region that covers the two main magnetic flux concentrations with approximately 3.6 Mm width and 10.87 Mm height. |

4. Simulation results

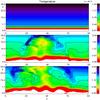

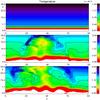

The simulation results are first shown in a plane at x = 45.7 (Fig. 2), which crossed through the center of the two main magnetic polarities. The vertical profile of the temperature is shown in Fig. 4 for t = 0 (top panel), 80 (middle panel) and 160 s (bottom panel). In t = 0 we have a height-dependent temperature as defined by the initial condition. At t = 80 s the effects of plasma compression and expansion shape the temperature profile together with Joule heating. An arc of hot plasma is formed above the two opposite magnetic polarities. The increase in temperature in this layer is approximately 0.5 in normalized units, which corresponds to 36 000 K. The region that is located just below it, however, experiences some drop in temperature. At t = 160 s the arc of hot plasma leaves the simulation box, and we are left with a corona in which the differences in temperature can reach one order of magnitudes.

|

Fig. 4 Temperature distribution in the vertical plane at x = 45.7 at the beginning (upper panel) and at t = 80 s and t = 160 s. The temperature in the color bar is presented in terms of the normalization value, T0 = 7.2 × 104 K. Spatial scale in units of L0 = 500 km. |

Figure 5 shows the parallel and perpendicular components of the current with respect to the magnetic field direction at t = 80 and t = 160 s. Obviously the enhanced current flows coincide well with the temperature increase. This would lead to an interpretation of the heating as being due to current dissipation only. However, as shown later, adiabatic heating can have an important contribution to the temperature increase.

|

Fig. 5 Parallel and perpendicular components of the electrical current at t = 80 s (upper two panels) and t = 160 s (lower two panels) in the same diagnostic plane as in Fig. 4. The enhancement in perpendicular current is located at the same place of the temperature maximum. The electrical current in the color bar is presented in units of J0 = 1.54 × 10-4 A/m2. The spatial scale is given in units of L0 = 500 km. |

|

Fig. 6 Adiabatic cooling/heating rate after 80 s and 160 s in the plane x = 45.7, according to the first term in the r.h.s. of Eq. (12) over density, (−(γ − 1)T∇·u < 0). Color bar is normalized to T0/τ0 = 7.2 × 103 K/s. Spatial scale in units of L0 = 500 km. |

5. Energy balance

Let us now diagnose the different contributions to plasma heating in the BP region. First we discuss in Sect. 5.1, the overall global heating. In Sect. 5.2 we present the dependence on the resistivity model. Finally, the flux-tube heating is analyzed in Sect. 5.3.

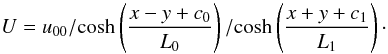

5.1. Global effect of current dissipation and compression

In order to understand the relative contribution of current dissipation and plasma compression to the coronal plasma heating in the BP region it is appropriate to analyze the pressure changes by rewriting Eq. (4) in terms of a continuity equation for the temperature evolution. This leaves two source terms on the right hand side of the equation:

(12)Let us first analyze the first case, where an anomalous resistivity is used when the current carrier velocity exceeds a critical value. Figure 6 shows the resulting distribution of − (γ − 1) T ∇·u in the vertical diagnostic plane. This way we have a proxy for temperature changes associated with pressure compression and expansion.

(12)Let us first analyze the first case, where an anomalous resistivity is used when the current carrier velocity exceeds a critical value. Figure 6 shows the resulting distribution of − (γ − 1) T ∇·u in the vertical diagnostic plane. This way we have a proxy for temperature changes associated with pressure compression and expansion.

Adiabatic heating has an important role on the formation of the high-temperature arc that propagates upward toward the top boundary. It is also because of expansion that the temperature decreases below this hot arc.

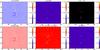

The values of the second term on the right hand side of the Eq. (11), (γ − 1) ηj2/ ρ, is shown in Fig. 7 in the plane x = 45.7 at t = 80 s and t = 160 s. Compared with the compressional part the contribution of the Joule heating appears to be negligible. For a better comparison of the contribution of the two terms on the right hand side of Eq. (11) in the temperature evaluation, the horizontal view is shown at the height of transition region in two different instance of time, t = 80 s on the left and t = 160 s on the right panel of Fig. 8.

|

Fig. 7 Joule heating rate (second term in the r.h.s. of Eq. (12), divided by density) after 80 s and 160 s in the plane x = 45.7. Physical units are the same as Fig. 6 with the same normalization for the color bar. The spatial scale is given in units of L0 = 500 km. |

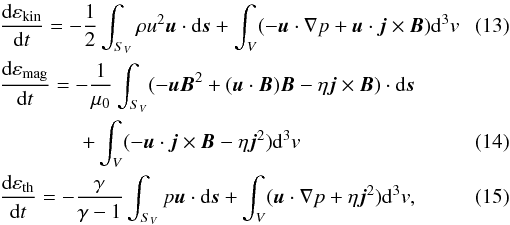

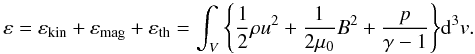

Now we analyze in more detail to which degree compression and Joule heating contribute to the evolution of the temperature. For this sake and to study the role of the forces involved in the energy conversion process, we performed a volume integration of the time rates of change of the kinetic, the magnetic, and the thermal energies in the simulation box above the chosen bright point region. Our approach is similar to that of Birn et al. (2009), who used energy transport equations to analyze the properties of energy conversions associated with a reconnection process. The contribution of different terms to the energy transport process can be studied from the following equations:  where εkin, εmag and εth denote the kinetic, ρu2/2 , the magnetic, B2/2μ0, and the thermal, P/(γ − 1), energies, respectively. The volume integrals (second term on the right-hand side) in these equations represent the energy conversion from one form into the other. These energy conversions are explicitly written in terms of the work done by the Lorentz force, the pressure gradient force, and Joule dissipation (left panel of Fig. 9). The initial spike in the Lorentz force is in part caused by numerical discretization errors and in part by the onset of photospheric footpoint motion. The initial oscillations are substantially damped during approximately two Alfvén times, followed by a state of an approximate force balance. This effect was found to be smaller in a run where footpoint motion was excluded. The initial perturbation has a minor effect on the initial extrapolated magnetic field, it does not affect the currents and Lorentz forces at later times.

where εkin, εmag and εth denote the kinetic, ρu2/2 , the magnetic, B2/2μ0, and the thermal, P/(γ − 1), energies, respectively. The volume integrals (second term on the right-hand side) in these equations represent the energy conversion from one form into the other. These energy conversions are explicitly written in terms of the work done by the Lorentz force, the pressure gradient force, and Joule dissipation (left panel of Fig. 9). The initial spike in the Lorentz force is in part caused by numerical discretization errors and in part by the onset of photospheric footpoint motion. The initial oscillations are substantially damped during approximately two Alfvén times, followed by a state of an approximate force balance. This effect was found to be smaller in a run where footpoint motion was excluded. The initial perturbation has a minor effect on the initial extrapolated magnetic field, it does not affect the currents and Lorentz forces at later times.

The surface integrals are also needed to obtain the energy rates, when they indicate the transport of each of the three forms of energies. With the chosen boundary condition however, the values of these surface integrals are zero at the lower boundary. They compensate for each other through the side boundaries of the simulation box as well. At the upper boundary however, one needs to consider the contribution of these surface integrals at the rate of energy transfer. This means E × B, Pu, and ρu2u for the transport of the magnetic, the kinetic, and the thermal energies, respectively. The values of these terms at the upper boundary are shown in Fig. 10. Evidently the contribution by these terms is insignificant, consequently it would be a good approximation to consider only the volume integrals for the change in the energy rates.

|

Fig. 8 Temperature, first, and second terms of Eq. (12) over density, in the left, middle, and right panels, respectively. The result is shown in a horizontal plane in the transition region at two instances of time, t = 80 s in top and t = 160 s in the bottom panel. The temperature is normalized to T0 = 7.2 × 104 K. The two other panels are normalized to T0/τ0 = 7.2 × 103 K/s. The spatial scale is given in units of L0 = 500 km. |

The changes in the energy rates are shown in the right panel of Fig. 9, the forces responsible for these changes are depicted in the left panel of the figure. As one can see by comparing the two panels, the magnetic energy is transferred to kinetic energy almost completely via the work done by the Lorentz force, which accelerates the plasma. It is an intermediate step however, followed by the work done by pressure gradient force, which converts the kinetic energy into thermal energy. This decelerates the plasma motion until, finally, the Lorentz force is balanced. The direct transformation of magnetic energy to thermal energy (Joule heating) is via Ohmic current dissipation, ηJ2. A comparison of the energy conversions rates (see Fig. 9, right panel) shows however that Joule dissipation plays a minor role in the energy exchange process, while the other contributions are several orders of magnitudes higher. The minor role of Joule heating compared with the adiabatic process in the increase of thermal energy was also found for a solar flare by Birn et al. (2009), who explained the compressional heating in two almost simultaneous steps: acceleration by the Lorentz force and deceleration by pressure gradients.

|

Fig. 9 The work done by the Lorentz force, the pressure gradient force, and the Joule heating power (top panel). The change of magnetic, thermal, and kinetic energy rates (bottom panel). The values are measured in units of power, |

5.2. Influence of different resistivity models

The previous calculation was based on an anomalous resistivity model with the current carrier velocity as a critical value for a local added resistivity. To better understand the influence of the resistivity, we performed the simulation also with two other resistivity models, one that uses a current density-dependent resistivity and another with constant resistivity.

Figure 11 depicts the resulting energy conversion rates and the work done by the involved forces v· J × B,v· ∇P and by η J2, for all three resistivity models by using different line styles for the results obtained by using the different resistivity model. The results obtained for the three cases show that the resistivity model influences the dynamics of the system and the thermal energy rate mainly through the pressure gradient force. While the magnetic and the kinetic energy rates of change depend only weakly on the resistivity model, the rate of the temperature change is significantly influenced. Nevertheless, independent of the used resistivity model the heating is caused mainly by the work done by the pressure gradient force. At the same time the contribution of the Joule heating is about two orders of magnitude smaller (note the scale of the plots in the top row). We conclude that the adiabatic compression is the dominant effect in increasing the temperature in the BP region in all three cases.

5.3. Flux tube heating

To locate the heating effect better, it is appropriate to determine it for individual flux tubes, integrating along the magnetic field lines instead of taking values averaged over the whole simulation box, as reported in the previous sections. In this integration one has to take into account the changing cross-section of flux tubes. This can be done by applying the concept of the differential flux tube volume  , where ds indicates the step size along the field line. This way the flux conservation in a flux tube (Φ = A × B = const.) is taken into account by the proportionally of the cross-section to B-1. Note that high flux tube volumes correspond to field line rising high into the corona or hitting regions of vanishing magnetic fields. The energy is transported in accordance with the upward directed Poynting flux E × B, enhanced magnetic tension is carried away by wave propagation.

, where ds indicates the step size along the field line. This way the flux conservation in a flux tube (Φ = A × B = const.) is taken into account by the proportionally of the cross-section to B-1. Note that high flux tube volumes correspond to field line rising high into the corona or hitting regions of vanishing magnetic fields. The energy is transported in accordance with the upward directed Poynting flux E × B, enhanced magnetic tension is carried away by wave propagation.

|

Fig. 10 First term in the right hand side of Eqs. (13)–(15), (surface integrals) is shown in the upper boundary of the simulation box after 160 s. Note that the color bars are measured in units of energy densities over normalized time, |

For the quantities described in Sect. 5.1 the resulting flux-tube-integrated values are shown in Fig. 12 in the horizontal reference plane just above the transition region. The values reached indicate once more the negligible role of Joule heating by current dissipation for the thermal energy change in the bright point region compared with the dominant role of the pressure gradient force. Please note the different range of the plots in Fig. 12 as indicated by the color bar. Evidently the locations at which this force and also maximum rates of energy changes appear coincide. Furthermore, the same pattern has formed in the integration result of v· ∇P, v· J × B and the rate of change of the different kinds of energy. This pattern can clearly be seen in the integration of total energy along the field lines (Fig. 13), which is the sum of the kinetic, the magnetic, and the thermal energies:  The left panel of Fig. 14 shows the result of this integration for the temperature and the flux tube volume. The coincidence of the temperature enhancement with the maxima obtained in the flux tube integrated energy change rates and forces shows that the heat is provided by the plasma compression because the Lorentz force.

The left panel of Fig. 14 shows the result of this integration for the temperature and the flux tube volume. The coincidence of the temperature enhancement with the maxima obtained in the flux tube integrated energy change rates and forces shows that the heat is provided by the plasma compression because the Lorentz force.

The enhanced flux tube integrated values follow the same pattern as the BP. This indicates that the regions of the enhanced temperatures correspond to the foot points of field lines leading to higher altitudes or to regions where the magnetic field vanishes. The plasma motion across these regions supplies the magnetic energy that is converted into thermal energy.

6. Summary and discussion

We have presented the results of heating processes in the region of an observed X-ray coronal bright point. In particular we have investigated the importance of the work done by adiabatic compression compared with Joule heating in the course of the dynamic evolution and heat production near the bright point.

The simulation shows that an arc-shaped structure of enhanced temperature forms that is two-four times hotter than the background plasma. This structure is located above the two main opposite photospheric magnetic flux concentrations. It coincides with the location where the electrical current densities are maximum. The structures of the temperature and the current density enhancements, indeed, coincide.

We also examined the contribution of the Lorentz force, the pressure gradient force, and Joule heating by performing volume integrals in the simulation box that determine the magnetic, the kinetic, and the thermal energy change rates for three different resistivity models. We found that independent of the resistivity model the magnetic energy is transformed to kinetic energy through the work done by Lorentz force. The kinetic energy in turn is converted to thermal energy by the pressure gradients that balance the Lorentz force.

A comparison of the effect of the three energy conversions through v· J × B, v· ∇P and η J2 showed that adiabatic compression has an important role in temperature increase in the upper corona. This does not depend on the resistivity model used in the simulation.

For a better understanding of the heating processes we utilized the concept of differential flux tube integration of the different contributions along the magnetic field lines. A quantitative comparison in the horizontal plane, from where the integration starts, shows that the energy conversion rate, the total energies and work done by Lorentz and pressure gradient forces are located in the same flux tubes, and that the temperature and flux tube volume are maximum at the same place.

|

Fig. 11 Top panels show the work done by the Lorentz force, the pressure gradient force, and the Joule heating power. The energy change rates for three different resistivity models are shown in the bottom panels. Different lines correspond to anomalous current carrier-dependent (dashed), anomalous current-dependent (dotted) and constant (solid line) resistivity models. Note that the values are measured in units of power, |

|

Fig. 12 Integration along the field lines using the differential flux tube volume concept for the work done by the Lorentz force, the pressure gradient force, and the Joule heating (top panel, from left to right), and the changes in rates of magnetic field change, the thermal and the kinetic energy (bottom panel, from left to right) at t = 160 s. The color bars are normalized by power, |

We conclude that the conversion of magnetic energy to kinetic energy via the work done by the Lorentz force and from kinetic to thermal energy due to the work done against the pressure gradient force determine the heating of this bright point. We could show that plasma compression dominates the heating of the bright point. In contrast, the role of Joule dissipation appeared to be negligibly small. The temperature enhancement follows the same pattern. That the pattern obtained by calculating flux volume integrals coincides with the one of temperature and energy change rates bring us to the conclusion that plasma motion at the footpoints of the flux tubes carries the energy upward and makes the flux tubes rise to the higher corona. The magnetic energy is converted into thermal energy until the plasma compression is balanced by the Lorentz force. In the local, flux-tube oriented consideration we could also see that the role of the Joule heating in these energy conversion processes was negligible and the heating of plasma in the bright point region is basically caused by pressure gradient force.

First, the fact that Joule heating is weak in the corona was not entirely unexpected, but it is quantitatively confirmed here. It is worth to remember that the necessary up-scaling of the resistivity and of the onset condition of micro-turbulent anomalous resistivity to the resolved by the MHD simulation grid scales does even overestimate the actual Joule heating. As a result Joule heating cannot be considered a viable process unless there is a convincing argument that the dissipation regions are volume-filling to a much larger extent than the already large one used in the present model.

Second, the results very clearly demonstrate that compression is an important processes in the energy budget. It is not clear to which extent compression can contribute to the overall coronal heating, but it is certainly important for the local heating of BPs.

|

Fig. 13 Results of integration along the magnetic field lines using the differential flux tube volume concept for the normalized total energy (top, left panel) and magnetic (top, right panel), kinetic (bottom, left panel) and thermal energies (bottom, right panel), at t = 160 s. The energies are normalized to |

|

Fig. 14 Temperature (normalized to 7.2 × 104 K) and flux tube volume (normalized to |

Third, in this context the nature and the consequences of plasma compression deserve some consideration. In ideal MHD adiabatic compression is reversible. But the consequent flux

tube heating is, however, irreversible because of magnetic reconnection and other mixing processes. Magnetic reconnection, in particular, changes flux tube identities (magnetic connectivity), while flux tube entropy conservation requires ideal MHD in addition to appropriate boundary conditions. Local adiabatic compression becomes irreversible also because of other plasma transport processes such as heat conduction and radiative cooling. These aspects will be separately investigated in a subsequent paper. Meanwhile the results presented here clearly demonstrate that in the overall energy budget plasma compression (and expansion) can play an important role in the heating of the corona.

Acknowledgments

One of the authors (S.J.) gratefully acknowledges her Max-Planck-Society PHD-stipend.

References

- Birn, J., Fletcher, L., Hesse, M., & Neukirch, T. 2009, ApJ, 695, 1151 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, D. S., Parnell, C. E., Deluca, E. E., Golub, L., & McMullen, R. A. 2001, Sol. Phys., 201, 305 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Büchner, J. 2006, Space Sci. Rev., 122, 149 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Büchner, J. 2007, in New Solar Physics with Solar-B Mission, ed. K. Shibata, S. Nagata, & T. Sakurai, ASP Conf. Ser., 369, 407 [Google Scholar]

- Büchner, J., & Elkina, N. 2005, Space Sci. Rev., 121, 237 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Büchner, J., & Elkina, N. 2006, Phys. Plasmas, 13, 082304 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Büchner, J., Nikutowski, B., & Otto, A. 2004a, in AGU momograph, Washington, in Space particle accelaration, ed. D. Gallagher, 223, 201 [Google Scholar]

- Büchner, J., Nikutowski, B., & Otto, A. 2004b, in SOHO 15 Coronal Heating, ed. R. W. Walsh, J. Ireland, D. Danesy, & B. Fleck, ESA SP, 575, 23 [Google Scholar]

- Büchner, J., Nikutowski, B., & Otto, A. 2004c, in Multi-Wavelength Investigations of Solar Activity, ed. A. V. Stepanov, E. E. Benevolenskaya, & A. G. Kosovichev, IAU Symp., 223, 353 [Google Scholar]

- Golub, L., Krieger, A. S., Silk, J. K., Timothy, A. F., & Vaiana, G. S. 1974, ApJ, 189, L93 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, A. S., Vaiana, G. S., & van Speybroeck, L. P. 1971, in Solar Magnetic Fields, ed. R. Howard, IAU Symp., 43, 397 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Longcope, D. W. 1998, ApJ, 507, 433 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Madjarska, M. S., Doyle, J. G., Teriaca, L., & Banerjee, D. 2003, A&A, 398, 775 [Google Scholar]

- Neukirch, T., Dreher, J., & Birk, T. 1997, Adv. Space Res., 19, 1861 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- November, L. J., & Simon, G. W. 1988, ApJ, 333, 427 [Google Scholar]

- Otto, A., Büchner, J., & Nikutowski, B. 2007, A&A, 468, 313 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Parker, E. N. 1972, ApJ, 174, 499 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Parnell, C. E., Priest, E. R., & Titov, V. S. 1994, Sol. Phys., 153, 217 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Potter, D. 1973, Computational Physics, ed. John Wiley and Sons [Google Scholar]

- Priest, E. R., Parnell, C. E., & Martin, S. F. 1994, ApJ, 427, 459 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Roussev, I., Galsgaard, K., & Judge, P. G. 2002, A&A, 382, 639 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Santos, J. C., & Büchner, J. 2007, Astrophys. Space Sci. Trans., 3, 29 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Santos, J. C., Büchner, J., Madjarska, M. S., & Alves, M. V. 2008, A&A, 490, 345 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Silin, I., Büchner, J., & Vaivads, A. 2005, Phys. Plasmas, 12, 062902 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer, L. 1962, Physics of Fully Ionized Gases, ed. L. Spitzer [Google Scholar]

- Vaiana, G. S., Krieger, A. S., Speybroeck, L. P., & Zehnpfennig Bul, T. 1970, Am. Phys. Soc., 15, 611 [Google Scholar]

- von Rekowski, B., & Hood, A. W. 2006, MNRAS, 369, 4356 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- von Rekowski, B., & Hood, A. W. 2008a, MNRAS, 385, 1792 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- von Rekowski, B., & Hood, A. W. 2008b, MNRAS, 384, 972 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J., Kundu, M. R., & White, S. M. 2001, Sol. Phys., 198, 347 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

All Tables

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 X-ray image taken from XRT/Hinode on 19 December 2006 at 22:08 UT. Insert: the LOS component of the photospheric magnetic field in a 64 × 64 arcsec2 horizontal plane taken from MDI/Soho, where white (black) spots correspond to upward (downward) directed line-of-sight components of the photospheric magnetic field. The BP and the related magnetic field feature are indicated in the images. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Potential magnetic field extrapolated from the filtered MDI magnetograms and used as initial configuration for the magnetic field in our simulation. The blue lines show the magnetic field lines. The color code depicts the LOS component of the magnetic field. Note that axes here are in terms of grid points, 64 in z direction and 128 × 128 in x, y plane. This corresponds to 15.45 Mm at z direction and 46.4 Mm at x and y directions. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 Horizontal plasma velocities in the photosphere. Left panel: velocities obtained by applying LCT technique to MDI magnetograms between 22:17 and 22:22 UT. The right panel shows the vortices that are used to approximate this motion in the simulation. The panels are showing the region that covers the two main magnetic flux concentrations with approximately 3.6 Mm width and 10.87 Mm height. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4 Temperature distribution in the vertical plane at x = 45.7 at the beginning (upper panel) and at t = 80 s and t = 160 s. The temperature in the color bar is presented in terms of the normalization value, T0 = 7.2 × 104 K. Spatial scale in units of L0 = 500 km. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5 Parallel and perpendicular components of the electrical current at t = 80 s (upper two panels) and t = 160 s (lower two panels) in the same diagnostic plane as in Fig. 4. The enhancement in perpendicular current is located at the same place of the temperature maximum. The electrical current in the color bar is presented in units of J0 = 1.54 × 10-4 A/m2. The spatial scale is given in units of L0 = 500 km. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 6 Adiabatic cooling/heating rate after 80 s and 160 s in the plane x = 45.7, according to the first term in the r.h.s. of Eq. (12) over density, (−(γ − 1)T∇·u < 0). Color bar is normalized to T0/τ0 = 7.2 × 103 K/s. Spatial scale in units of L0 = 500 km. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 7 Joule heating rate (second term in the r.h.s. of Eq. (12), divided by density) after 80 s and 160 s in the plane x = 45.7. Physical units are the same as Fig. 6 with the same normalization for the color bar. The spatial scale is given in units of L0 = 500 km. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 8 Temperature, first, and second terms of Eq. (12) over density, in the left, middle, and right panels, respectively. The result is shown in a horizontal plane in the transition region at two instances of time, t = 80 s in top and t = 160 s in the bottom panel. The temperature is normalized to T0 = 7.2 × 104 K. The two other panels are normalized to T0/τ0 = 7.2 × 103 K/s. The spatial scale is given in units of L0 = 500 km. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 9 The work done by the Lorentz force, the pressure gradient force, and the Joule heating power (top panel). The change of magnetic, thermal, and kinetic energy rates (bottom panel). The values are measured in units of power, |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 10 First term in the right hand side of Eqs. (13)–(15), (surface integrals) is shown in the upper boundary of the simulation box after 160 s. Note that the color bars are measured in units of energy densities over normalized time, |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 11 Top panels show the work done by the Lorentz force, the pressure gradient force, and the Joule heating power. The energy change rates for three different resistivity models are shown in the bottom panels. Different lines correspond to anomalous current carrier-dependent (dashed), anomalous current-dependent (dotted) and constant (solid line) resistivity models. Note that the values are measured in units of power, |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 12 Integration along the field lines using the differential flux tube volume concept for the work done by the Lorentz force, the pressure gradient force, and the Joule heating (top panel, from left to right), and the changes in rates of magnetic field change, the thermal and the kinetic energy (bottom panel, from left to right) at t = 160 s. The color bars are normalized by power, |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 13 Results of integration along the magnetic field lines using the differential flux tube volume concept for the normalized total energy (top, left panel) and magnetic (top, right panel), kinetic (bottom, left panel) and thermal energies (bottom, right panel), at t = 160 s. The energies are normalized to |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 14 Temperature (normalized to 7.2 × 104 K) and flux tube volume (normalized to |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.