| Issue |

A&A

Volume 519, September 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A37 | |

| Number of page(s) | 8 | |

| Section | Astrophysical processes | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200913981 | |

| Published online | 09 September 2010 | |

X-ray variation statistics and wind clumping in Vela X-1

F. Fürst1 - I. Kreykenbohm1 - K. Pottschmidt2,3 - J. Wilms1 - M. Hanke1 - R. E. Rothschild4 - P. Kretschmar5 - N. S. Schulz6 - D. P. Huenemoerder6 - D. Klochkov7 - R. Staubert7

1 - Dr. Karl Remeis-Sternwarte & ECAP, Universität

Erlangen-Nürnberg, Sternwartstr. 7, 96049 Bamberg,

Germany

2 - CRESST and NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Astrophysics Science

Division, Code 661, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA

3 - Center for Space Science and Technology, University of Maryland

Baltimore County, 1000 Hilltop Circle, Baltimore, MD 21250, USA

4 - Center for Astrophysics & Space Sciences, University of

California, San Diego, 9500 Gilman Drive, La Jolla, CA 92093, USA

5 - European Space Agency, European Space Astronomy Centre, Villafranca

del Castillo, PO Box 78, 28691 Villanueva de

la Cañada, Madrid, Spain

6 - Center for Space Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology,

77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA

7 - Kepler Center for Astro and Particle Physics, Institut für

Astronomie und Astrophysik, Universität Tübingen, Sand 1,

72076 Tübingen, Germany

Received 29 December 2009 / Accepted 19 May 2010

Abstract

We investigate the structure of the wind in the neutron star X-ray

binary system Vela X-1 by analyzing its flaring behavior.

Vela X-1 shows constant flaring, with some flares reaching

fluxes of more than 3.0 Crab between 20-60 keV for

several 100 s, while the average flux is around

250 mCrab. We analyzed all archival INTEGRAL

data, calculating the brightness distribution in the 20-60 keV

band, which, as we show, closely follows a log-normal distribution.

Orbital resolved analysis shows that the structure is strongly

variable, explainable by shocks and a fluctuating accretion wake.

Analysis of RXTE ASM data suggests a strong orbital

change of ![]() .

Accreted clump masses derived from the INTEGRAL

data are on the order of

.

Accreted clump masses derived from the INTEGRAL

data are on the order of ![]() g.

We show that the lightcurve can be described with a model of

multiplicative random numbers. In the course of the simulation we

calculate the power spectral density of the system in the

20-100 keV energy band and show that it follows a red-noise

power law. We suggest that a mixture of a clumpy wind, shocks, and

turbulence can explain the measured mass distribution. As the recently

discovered class of supergiant fast X-ray transients (SFXT) seems to

show the same parameters for the wind, the link between persistent HMXB

like Vela X-1 and SFXT is further strengthened.

g.

We show that the lightcurve can be described with a model of

multiplicative random numbers. In the course of the simulation we

calculate the power spectral density of the system in the

20-100 keV energy band and show that it follows a red-noise

power law. We suggest that a mixture of a clumpy wind, shocks, and

turbulence can explain the measured mass distribution. As the recently

discovered class of supergiant fast X-ray transients (SFXT) seems to

show the same parameters for the wind, the link between persistent HMXB

like Vela X-1 and SFXT is further strengthened.

Key words: accretion, accretion disks - X-rays: binaries - X-rays: individuals: Vela X-1 - methods: statistical

1 Introduction

The high-mass X-ray binary (HMXB) Vela X-1 was discovered in

1967 (Chodil et al. 1967)

and is today one of the best studied objects of its class hosting a

neutron star. It is a bright, eclipsing source, showing strong

pulsations with a pulse period of around 283 s (McClintock et al. 1976)

and an orbital period of 8.9 days (van

Kerkwijk et al. 1995). Quaintrell

et al. (2003) have shown that the separation

between the neutron star and its optical companion, the B0.5Ib

supergiant HD 77581, is only

1.7 stellar radii. The neutron star is thus deeply embedded in

the stellar wind of the supergiant, which has a mass loss rate of about

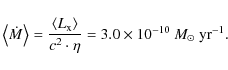

![]() (Nagase et al. 1986).

Material from the wind is accreted by the neutron star and is channeled

by its strong magnetic field onto the magnetic poles. The accretion

rate leads to an average X-ray luminosity of

(Nagase et al. 1986).

Material from the wind is accreted by the neutron star and is channeled

by its strong magnetic field onto the magnetic poles. The accretion

rate leads to an average X-ray luminosity of ![]() ,

although the luminosity is strongly variable on all time-scales,

varying up to a factor of at least 20-30 (Staubert et al. 2004;

Kreykenbohm

et al. 2008). Staubert

et al. (2004) found short, but very bright flares

reaching up to almost 7 Crab (1000 counts s-1

[cps] in the 20-40 keV band of INTEGRAL

ISGRI).

,

although the luminosity is strongly variable on all time-scales,

varying up to a factor of at least 20-30 (Staubert et al. 2004;

Kreykenbohm

et al. 2008). Staubert

et al. (2004) found short, but very bright flares

reaching up to almost 7 Crab (1000 counts s-1

[cps] in the 20-40 keV band of INTEGRAL

ISGRI).

The physical processes leading to this strong variation are unclear, however. Because the luminosity of the neutron star is proportional to the mass accretion rate, changes in the density or the effective velocity of the stellar wind directly lead to variations in the X-ray luminosity (Bondi & Hoyle 1944; Davidson & Ostriker 1973). Changes of that kind have shown up in simulations of the system (Mauche et al. 2008; Blondin et al. 1990,1991). Strong density changes have also been proposed to explain varying line strengths in high-resolution X-ray spectra (Sako et al. 1999; Watanabe et al. 2006) or were inferred via measurement of emission lines in hot, thin plasma at the same time with fluorescence lines in colder, optical thick plasma (Goldstein et al. 2004; Schulz et al. 2002).

The goal of this paper is to study the variations in the lightcurve and investigate a possible connection between the wind structure and the flaring behavior. This paper is structured as follows: in Sect. 2 we present our data and analysis method. In Sect. 3 we show an orbital phase averaged and orbital phase resolved analysis of the INTEGRAL ISGRI hard X-ray and RXTE ASM soft X-ray lightcurve. In order to constrain the physical processes leading to the observed variability we present a numerical method to simulate lightcurves in Sect. 4. For this simulation we calculate and model the power spectral density of Vela X-1. In Sect. 5 we summarize our results and discuss them in a larger context.

2 Observations and data

The ``International Gamma-Ray Astrophysics Laboratory'' (INTEGRAL,

Winkler et al. 2003)

carries three X-ray instruments: JEM-X (Lund

et al. 2003) for the soft X-rays, the spectrometer

SPI (Vedrenne et al. 2003)

and the ``Imager on Board the INTEGRAL Satellite''

(IBIS) for the hard X- and ![]() -rays

(Ubertini et al. 2003).

All these instruments are coded mask instruments (Renaud et al. 2006, and

references therein), allowing imaging of the hard X-ray sky. IBIS has a

field of view of almost

-rays

(Ubertini et al. 2003).

All these instruments are coded mask instruments (Renaud et al. 2006, and

references therein), allowing imaging of the hard X-ray sky. IBIS has a

field of view of almost ![]() and its detector consists of two planes: the bottom layer PICsIT,

sensitive in the 200 keV-10 MeV range and the top

layer ISGRI, which is sensitive between 15 keV-1 MeV (Lebrun et al. 2003).

Because of the coded mask instruments, observations with INTEGRAL

are usually carried out in a dithering mode, where the pointing of the

satellite is shifted slightly every 1800-3600 s. Each of these

pointings makes up one science window (ScW). During slews between ScWs,

taking about 150 s, no data are gathered. INTEGRAL

has provided a large fraction of the detailed hard X-ray studies of

Vela X-1, producing almost 3.6 Ms of good data

between 2003 November and 2006 May, split mainly into three large

blocks separated by some hundred days. All observations of INTEGRAL

that were public as of 2009 December 01 were used as the data basis for

this work, see Table 1.

and its detector consists of two planes: the bottom layer PICsIT,

sensitive in the 200 keV-10 MeV range and the top

layer ISGRI, which is sensitive between 15 keV-1 MeV (Lebrun et al. 2003).

Because of the coded mask instruments, observations with INTEGRAL

are usually carried out in a dithering mode, where the pointing of the

satellite is shifted slightly every 1800-3600 s. Each of these

pointings makes up one science window (ScW). During slews between ScWs,

taking about 150 s, no data are gathered. INTEGRAL

has provided a large fraction of the detailed hard X-ray studies of

Vela X-1, producing almost 3.6 Ms of good data

between 2003 November and 2006 May, split mainly into three large

blocks separated by some hundred days. All observations of INTEGRAL

that were public as of 2009 December 01 were used as the data basis for

this work, see Table 1.

Table 1: Overview of the INTEGRAL data of Vela X-1.

3 Statistical analysis

3.1 Phase averaged analysis

While data from individual observation blocks have previously been

analyzed in detail (Schanne

et al. 2007; Kreykenbohm et al. 2008),

studying all available data allowed us to carry out a deep statistical

analysis of the flaring behavior of Vela X-1. Our analysis was

performed with special regard to the giant flares with peak

luminosities of more than six times the average luminosity (Staubert

et al. 2004; Kreykenbohm et al. 2008),

i.e., more than 300 cps in ISGRI (![]() 1.3 Crab) between 20-60 keV. It

was not clear if these giant flares can be explained by the same

physical process as the other, common, flares in Vela X-1 or

if they are caused by a different mechanism.

1.3 Crab) between 20-60 keV. It

was not clear if these giant flares can be explained by the same

physical process as the other, common, flares in Vela X-1 or

if they are caused by a different mechanism.

For this work, only ISGRI data between 20-60 keV were

analyzed, because in this energy range the source is bright and the

flux is unaffected by photoabsorption, because typical values of the

equivalent hydrogen column ![]() outside the eclipse are below

outside the eclipse are below ![]() (Kreykenbohm et al. 1999).

Our analysis extends the energy range of prior observations of the

stellar wind, which used high-resolution spectra in soft X-rays to

investigate the features of the wind (Watanabe

et al. 2006, and references therein).

(Kreykenbohm et al. 1999).

Our analysis extends the energy range of prior observations of the

stellar wind, which used high-resolution spectra in soft X-rays to

investigate the features of the wind (Watanabe

et al. 2006, and references therein).

We extracted lightcurves from ISGRI using ii_light, a tool distributed as part of the Offline Scientific Analysis (OSA) 7.0 package. The time resolution was chosen to be 283.5 s to average each data-point over one pulse period to eliminate these fluctuations. The pulse period is changing in a random-walk behavior on all times scales (Deeter et al. 1989), but no long-term trend is evident, so that the chosen time resolution is sufficient for the purpose of this investigation.

As an example for the analyzed data the upper panel of Fig. 1 shows the lightcurve of the 20-60 keV band for data from revolutions 433-440 (Block 3).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{aa13981-09-fig1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa13981-09/Timg12.png)

|

Figure 1: Top: lightcurve in the 20-60 keV band. The vertical dashed lines show the start and the end of the eclipse according to the ephemeris of Kreykenbohm et al. (2008), and the dash-dotted line shows the respective center of eclipse. Bottom: simulated lightcurve with the same statistical parameters and temporal resolution as the observed lightcurve above, but without eclipses. See text for details. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{aa13981-09-fig2.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa13981-09/Timg13.png)

|

Figure 2: Histogram of the lightcurve of the 20-60 keV band, binned to 256 bins. The solid curve shows the best-fit single Gaussian, the dash-dotted one the histogram of the simulated lightcurve as described in the text. The dotted histogram to the left shows the noise level of the background. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The lightcurve data were filtered according to orbital phase ![]() ,

leaving only data of phases between

,

leaving only data of phases between ![]() ,

for which the system is out of eclipse. These data were then binned

into 256 count rate bins. The bins are spaced logarithmically between

1 cps and 1000 cps. This binning leads to a histogram

of the orbital phase averaged brightness distribution of the source,

shown in black in Fig. 2. The

distribution closely resembles a normal distribution in log-space,

i.e., a log-normal distribution (Fürst

et al. 2008). In order to quantify the shape of the

distribution we fitted a Gaussian function in log-space, i.e., a

log-normal distribution in countrate space. Following the approach by Uttley et al. (2005)

the uncertainties of the values Ni

of each histogram data bin were estimated to be

,

for which the system is out of eclipse. These data were then binned

into 256 count rate bins. The bins are spaced logarithmically between

1 cps and 1000 cps. This binning leads to a histogram

of the orbital phase averaged brightness distribution of the source,

shown in black in Fig. 2. The

distribution closely resembles a normal distribution in log-space,

i.e., a log-normal distribution (Fürst

et al. 2008). In order to quantify the shape of the

distribution we fitted a Gaussian function in log-space, i.e., a

log-normal distribution in countrate space. Following the approach by Uttley et al. (2005)

the uncertainties of the values Ni

of each histogram data bin were estimated to be ![]() ,

i.e., assuming Poisson statistics. We show that this assumption is

justified in Sect. 4.

The best-fit function, with a

,

i.e., assuming Poisson statistics. We show that this assumption is

justified in Sect. 4.

The best-fit function, with a ![]() -value of 190 for

81 degrees of freedom, is shown as solid line in Fig. 2,

where in the fit only bins with more than 20 measurements were taken

into account (see Gehrels 1986).

A Gaussian function in log-space is best characterized by its mean and

standard deviation. These values represent the median of the log-normal

function, which will be denoted as

-value of 190 for

81 degrees of freedom, is shown as solid line in Fig. 2,

where in the fit only bins with more than 20 measurements were taken

into account (see Gehrels 1986).

A Gaussian function in log-space is best characterized by its mean and

standard deviation. These values represent the median of the log-normal

function, which will be denoted as ![]() ,

and its multiplicative standard deviation,

,

and its multiplicative standard deviation, ![]() ,

i.e., 68.3% of all data points fall in the interval

,

i.e., 68.3% of all data points fall in the interval ![]() (Ahrens 1954), resulting in

asymmetric error bars according to the skewness of the distribution.

Note that consequently

(Ahrens 1954), resulting in

asymmetric error bars according to the skewness of the distribution.

Note that consequently ![]() is unitless. With these definitions, the best-fit function has a median

value of

is unitless. With these definitions, the best-fit function has a median

value of ![]() cps

and a multiplicative standard deviation of

cps

and a multiplicative standard deviation of ![]() .

Compared with that the measured count rates have a

median flux of

.

Compared with that the measured count rates have a

median flux of ![]() cps

and a multiplicative standard deviation of

cps

and a multiplicative standard deviation of ![]() ,

similar to the fit.

,

similar to the fit.

The largest cause of source-independent variation that affects

the data are background fluctuations. To obtain an estimate for the

background noise level, we extracted a lightcurve in the

20-60 keV energy band from a region in the sky without any

known X-ray source ![]() .

The brightness distribution of this background is shown with a dotted

line in Fig. 2.

The median value of the background distribution is

.

The brightness distribution of this background is shown with a dotted

line in Fig. 2.

The median value of the background distribution is ![]() cps,

which is below 99.98% of the source data. Note that the brightest data

points of the background reach values of up to 11 cps, which

is in the lower left flank of the source distribution. They do not,

however, change the overall shape and parameters of the distribution,

so that a significant background influence can be ruled out.

cps,

which is below 99.98% of the source data. Note that the brightest data

points of the background reach values of up to 11 cps, which

is in the lower left flank of the source distribution. They do not,

however, change the overall shape and parameters of the distribution,

so that a significant background influence can be ruled out.

3.2 Orbital phase resolved analysis

We have seen in the previous section that deviations from a log-normal distribution are visible. These deviations could be induced by averaging over all orbital phases, where possibly not all phases show the same statistical brightness variations. Systematic influences could be due to the complex and turbulent accretion geometry, consisting of a bow shock, an accretion wake, a possible photoionization wake or even a tidal stream (see, e.g., Mauche et al. 2008; Blondin et al. 1990,1991). An accretion wake in Vela X-1 was already postulated by Eadie et al. (1975), showing up as absorption dips in the lightcurve of the Ariel V Sky Survey Experiment.

To analyze the orbital influences, we extracted orbital phase

resolved histograms. The data set comprises ![]() 8 orbits overall, which allows us to extract

histograms with

8 orbits overall, which allows us to extract

histograms with ![]() .

We reduced the number of logarithmically spaced bins to 96 to collect

more than 20 values in most bins to satisfy the requirements for

.

We reduced the number of logarithmically spaced bins to 96 to collect

more than 20 values in most bins to satisfy the requirements for ![]() statistics. Figure 3

shows color-coded the probability of finding a datapoint in a countrate

bin for a given histogram, equivalent to the height of the histogram in

Fig. 2.

Additionally the average countrate in every bin is shown, together with

its uncertainty. As the average countrate can be calculated from a

large number of data points in the lightcurve, these uncertainties are

rather small. Significant variations from phase bin to phase bin can be

seen in the figure. Especially notable is a dip in the average

countrate around phase

statistics. Figure 3

shows color-coded the probability of finding a datapoint in a countrate

bin for a given histogram, equivalent to the height of the histogram in

Fig. 2.

Additionally the average countrate in every bin is shown, together with

its uncertainty. As the average countrate can be calculated from a

large number of data points in the lightcurve, these uncertainties are

rather small. Significant variations from phase bin to phase bin can be

seen in the figure. Especially notable is a dip in the average

countrate around phase ![]() and a sudden brightening to twice the value afterwards. Goldstein et al. (2004)

analyzed Chandra data taken at

and a sudden brightening to twice the value afterwards. Goldstein et al. (2004)

analyzed Chandra data taken at ![]() and

and ![]() of one orbit and measured a stronger absorbed spectrum in the

of one orbit and measured a stronger absorbed spectrum in the ![]() data. These authors explained the increased absorption by the accretion

wake being in the light of sight during that episode. The dip in

Fig. 3

occurs slightly before

data. These authors explained the increased absorption by the accretion

wake being in the light of sight during that episode. The dip in

Fig. 3

occurs slightly before ![]() .

If an accretion wake is responsible for this feature, it seems to have

shifted to earlier orbital phases in our data.

.

If an accretion wake is responsible for this feature, it seems to have

shifted to earlier orbital phases in our data.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{aa13981-09-fig3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa13981-09/Timg32.png)

|

Figure 3: Landscape plot of orbital phase resolved histograms of the ISGRI 20-60 keV data. Color-coded is the probability for a datapoint to fall into the respective histogram bin. The black line shows the median count rate in each phase bin. Uncertainties of that value are also plotted, but they are too small to be clearly visible in this plot. Note that the same histograms are shown twice for clarity. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

When analyzing the three data blocks (Table 1) separately an orbital modulation is also visible, although with different strength in the different blocks. This indicates a strongly variable feature rather than an orbitally stable one and suggests that the variation seen in Fig. 3 is biased by single orbits probably deviating strongly from the average orbital histogram, maybe due to a particularly active or quiet state of the system.

The influence of different ![]() values during the orbit can be investigated by analyzing data in softer

X-rays. Softer energy bands are far more affected by photoabsorption

than the ISGRI band, because the cross-section of the photoabsorption

is declining quickly with increasing energy as

values during the orbit can be investigated by analyzing data in softer

X-rays. Softer energy bands are far more affected by photoabsorption

than the ISGRI band, because the cross-section of the photoabsorption

is declining quickly with increasing energy as ![]() .

A very good data set in the soft X-rays is provided by the All-Sky

Monitor (ASM, Levine et al.

1996) aboard the ``Rossi X-Ray Timing Explorer'' (RXTE).

The ASM

performs 90 s dwells on an irregular basis onto different

sources, including Vela X-1, and thus provides good statistics

in the three energy bands between 1.5-10 keV called A

(1.5-3 keV), B (3-5 keV), and C (5-10 keV)

band.

.

A very good data set in the soft X-rays is provided by the All-Sky

Monitor (ASM, Levine et al.

1996) aboard the ``Rossi X-Ray Timing Explorer'' (RXTE).

The ASM

performs 90 s dwells on an irregular basis onto different

sources, including Vela X-1, and thus provides good statistics

in the three energy bands between 1.5-10 keV called A

(1.5-3 keV), B (3-5 keV), and C (5-10 keV)

band.

We performed a similar analysis of the ASM data as of the

ISGRI data, but binning the countrate directly to 256 bins

instead of its logarithm. The linear binning was necessary because

especially in the eclipse many data points of the lightcurve are

negative and cannot be presented on a logarithmic scale. It has

previously been shown that due to the complex accretion geometry of the

system, the absorption coefficient frequently changes dramatically over

the orbit (Haberl

& White 1990; Kretschmar et al. 2008).

Especially in the late orbital phases after ![]() ,

the accretion and photoionization wake, consisting of denser material,

are expected to be in the line of sight (Kaper

et al. 1994). To analyze the influence of the

absorption on the brightness distribution, we divided the data into the

same 20 orbital phases as the ISGRI data.

,

the accretion and photoionization wake, consisting of denser material,

are expected to be in the line of sight (Kaper

et al. 1994). To analyze the influence of the

absorption on the brightness distribution, we divided the data into the

same 20 orbital phases as the ISGRI data.

Figure 4 shows the histograms for the A+B band and for the C band. We added the narrow A and B band as both showed very similar behavior, but only low significance. By adding A and B the countrates are comparable to the C band. It is obvious that in both bands the mean luminosity is monotonically decreasing over the orbit (see also Wen et al. 2006). At the same time, the distribution narrows, meaning that strong deviations from the mean are more common in the early orbital phases than in the later ones. It is remarkable that no sudden dip structures like in the ISGRI data in Fig. 3 are visible. This could be because the ASM data stretch over more than 13 years, averaging out any individual orbit variations. As the ISGRI data comprise only eight orbits, they are strongly influenced by single outliers and do not provide a sufficient time basis for determining an average orbital profile. Nonetheless, no declining trend in the average brightness is evident in ISGRI.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{aa13981-09-fig4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa13981-09/Timg34.png)

|

Figure 4: Same as Fig. 3, but for the ASM data in the 1.5-5 keV (top) and 5-10 keV band (middle). The bottom panel shows the hardness ratio, overplotted is the median of the distribution. Data in the eclipse were ignored. A clear trend to a harder spectrum at late orbital phases is visible. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The missing trend strongly points to the explanation that the trend in the ASM is due to increasing absorption by a cold absorber. This interpretation is supported by the analysis of the hardness ratio, which is increasing with orbital phase (Fig. 4, bottom panel). The first phase bin after eclipse is also significantly harder on average, because the X-ray source is still behind the extended stellar atmosphere of the optical companion (Kretschmar et al. 2008). In contrast to the countrate histograms, the hardness ratio shows a larger variation at later orbital phases. This broadening again indicates that no persistent features are present in the wind, but that any absorbing material is only temporary and that the column density is varying from orbit to orbit.

Looking at the distribution of the ASM as data, we find that

they follow a log-normal distribution only coarsely. We ascribe this to

the strong influence of photoabsorption on the ASM lightcurve, reducing

the apparent brightness. This influence means that the observed

distribution is not only caused by flaring, i.e., changes in the mass

accretion rate, but also by varying ![]() .

This entanglement makes it impossible to infer the distribution of the

accreted masses from the measured distribution.

.

This entanglement makes it impossible to infer the distribution of the

accreted masses from the measured distribution.

4 On generating log-normal distributions

In the previous sections we have seen that the brightness distribution

above 20 keV is nearly log-normal. In the peak of the

distribution relatively large deviations are, however, visible and the

overall reduced ![]() -value

of the fit is still high. All attempts at fitting a log-normal

distribution to the rising flank up to the peak resulted in

unacceptable

-value

of the fit is still high. All attempts at fitting a log-normal

distribution to the rising flank up to the peak resulted in

unacceptable ![]() -values

only. These deviations from the log-normal distribution are a hint that

the underlying processes are not purely multiplicative (Uttley et al. 2005). As

the log-normal distribution is very well understood we demonstrate in

this section a method to simulate a lightcurve showing a log-normal

brightness distribution. These simulations illustrate the physical

processes that are at work in a system like Vela X-1.

Furthermore they help us to estimate the uncertainties in the

distributions and to separate the influence of the sampling from

intrinsic source behavior. To simulate the lightcurves we implemented

the method proposed by Uttley

et al. (2005), introducing slight modifications to

allow other mean values than 0.

-values

only. These deviations from the log-normal distribution are a hint that

the underlying processes are not purely multiplicative (Uttley et al. 2005). As

the log-normal distribution is very well understood we demonstrate in

this section a method to simulate a lightcurve showing a log-normal

brightness distribution. These simulations illustrate the physical

processes that are at work in a system like Vela X-1.

Furthermore they help us to estimate the uncertainties in the

distributions and to separate the influence of the sampling from

intrinsic source behavior. To simulate the lightcurves we implemented

the method proposed by Uttley

et al. (2005), introducing slight modifications to

allow other mean values than 0.

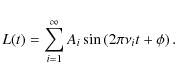

The method used is based on the fact that any linear

lightcurve L(t) can be written

according to the Fourier theorem as a linear superposition of

individual sinusoids with fixed frequencies ![]() and normalizations Ai

and phases

and normalizations Ai

and phases ![]() ,

i.e.

,

i.e.

|

(1) |

On the other hand the Fourier transform of a lightcurve can also be represented by a superposition of individual sinusoids. By drawing the amplitudes and phases of these sinusoids from a normal distribution and calculating the inverse Fourier transformation of these values, a linear, stochastic lightcurve can easily be simulated (Timmer & König 1995). To obtain a simulated lightcurve resembling observational data, randomly drawn amplitudes and phases of each frequency are weighted by a filter function that describes the frequency spectrum of the observed data. This filter function is given by the shape of the periodogram of the data, as only real values are important for the lightcurve (Uttley et al. 2005). According to the central limit theorem, the simulated lightcurve will have a normal brightness distribution, because it can be written as the sum of random numbers drawn from the same probability distribution. Uttley et al. (2005) pointed out that in much the same way, a lightcurve with a log-normal brightness distribution can be simulated by using the product instead of the sum of randomized sinusoids. This is most easily achieved by taking the exponential function of a linear lightcurve. Uttley et al. (2005) used the method by Timmer & König (1995) to obtain the linear lightcurve, an approach we also adopted for our analysis.

In order to evaluate the shape of the power spectral density

(PSD) of Vela X-1 we extracted a lightcurve with 6 s

resolution in the 20-100 keV energy range and divided it into

segments of evenly spaced data of 49 152 s (

![]() s). In order to

obtain evenly spaced lightcurves, we interpolated over small gaps

around the slew time scale of

s). In order to

obtain evenly spaced lightcurves, we interpolated over small gaps

around the slew time scale of ![]() 150 s. This interpolation reduces

spurious power on the ScW timescale. The average PSD for all segments

drawn from data of Rev. 373-383 (Block 2) is shown in

Fig. 5,

together with the best-fit model consisting of a constant plus a power

law and 6 Lorentzian lines. The Lorentzians are characterized by their

peak frequency, their width and their normalization, describing the

overall contribution to the PSD. They are necessary to model the

contribution of the strong pulse with a pulse period of

283.5 s and its harmonics, as marked in Fig. 5. The

frequencies of the Lorentzians were fixed to multiples of the pulse

frequency. The first two Lorentzians are both located at the pulse

frequency, with Lorentz # 1 modeling a broad base, while Lorentz # 2

models the narrow spike. The inclusion of the broad component

drastically improves our fit. A similar superposition of two

Lorentzians at the pulse frequency was also seen in V 0332+53

by Mowlavi et al. (2006),

who interpreted it as a quasi periodic oscillation (QPO). A detailed

analysis of this feature in Vela X-1 is, however, beyond the scope of

this paper.

150 s. This interpolation reduces

spurious power on the ScW timescale. The average PSD for all segments

drawn from data of Rev. 373-383 (Block 2) is shown in

Fig. 5,

together with the best-fit model consisting of a constant plus a power

law and 6 Lorentzian lines. The Lorentzians are characterized by their

peak frequency, their width and their normalization, describing the

overall contribution to the PSD. They are necessary to model the

contribution of the strong pulse with a pulse period of

283.5 s and its harmonics, as marked in Fig. 5. The

frequencies of the Lorentzians were fixed to multiples of the pulse

frequency. The first two Lorentzians are both located at the pulse

frequency, with Lorentz # 1 modeling a broad base, while Lorentz # 2

models the narrow spike. The inclusion of the broad component

drastically improves our fit. A similar superposition of two

Lorentzians at the pulse frequency was also seen in V 0332+53

by Mowlavi et al. (2006),

who interpreted it as a quasi periodic oscillation (QPO). A detailed

analysis of this feature in Vela X-1 is, however, beyond the scope of

this paper.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{aa13981-09-fig5.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa13981-09/Timg39.png)

|

Figure 5:

Showcase PSD of Vela X-1 from Revs 373-383 in the

20-100 keV ISGRI band. The red curve shows the best-fit model,

as described in the text. The blue power law continuum has a |

| Open with DEXTER | |

It is interesting to note that the power at half the pulse period (

![]() Hz) is more than 4

times higher than at the actual pulse period. This effect is caused by

the pulse shape in the regarded spectral energy range consisting of two

very similar pulses, which could easily be misunderstood as pulsations

with half the actual pulse period (Kreykenbohm

et al. 1999). The underlying continuum of the PSD

can be modeled accurately with the constant and the power law component

of the model, with the power law having the shape

Hz) is more than 4

times higher than at the actual pulse period. This effect is caused by

the pulse shape in the regarded spectral energy range consisting of two

very similar pulses, which could easily be misunderstood as pulsations

with half the actual pulse period (Kreykenbohm

et al. 1999). The underlying continuum of the PSD

can be modeled accurately with the constant and the power law component

of the model, with the power law having the shape ![]() ,

where

,

where ![]() .

All fit parameters are listed in Table 2.

.

All fit parameters are listed in Table 2.

Table 2: Fit parameters of the PSD (Fig. 5).

The noise level of INTEGRAL ISGRI PSDs is

poorly understood, but a comparison with RXTE PCA

PSDs shows that for instrumental reasons it is not purely Poissonian.

We are currently in the process of analyzing other INTEGRAL

data of other HMXB to investigate ISGRI's broad band timing

capabilities. For the present analysis, however, only the slope of the

power law of the PSD is important, which is independent of the overall

noise level. We compared the ISGRI result to PCA PSDs of

Vela X-1 and found a value of ![]() for the latter. The difference does not change the outcome of the

simulation. Contributions from the pulse period to the PSD can also be

neglected, as the sampling rate of the lightcurve is chosen to

eliminate them.

for the latter. The difference does not change the outcome of the

simulation. Contributions from the pulse period to the PSD can also be

neglected, as the sampling rate of the lightcurve is chosen to

eliminate them.

The simulation was then carried out using a PSD of the shape ![]() and taking care that

the emerging statistical parameters

and taking care that

the emerging statistical parameters ![]() and

and ![]() are

the same as for the input data. A part of the simulated lightcurve is

shown in the lower panel of Fig. 1. The

overall behavior of the data, showing short, strong flares can

be very well described with the model. The PSD has a relatively large

power at low frequencies, showing up in notable variations in the

statistical parameters of the emerging lightcurve between individual

runs of the simulation. To determine the size of these variations, we

simulated 250 lightcurves with the same parameters

are

the same as for the input data. A part of the simulated lightcurve is

shown in the lower panel of Fig. 1. The

overall behavior of the data, showing short, strong flares can

be very well described with the model. The PSD has a relatively large

power at low frequencies, showing up in notable variations in the

statistical parameters of the emerging lightcurve between individual

runs of the simulation. To determine the size of these variations, we

simulated 250 lightcurves with the same parameters ![]() and

and ![]() .

As the simulated lightcurve incorporates a frequency spectrum of

similar shape as the data, the uncertainty levels of the simulation can

be used to estimate the uncertainty of each histogram bin of the data.

The standard deviation in the simulation in each bin was on the order

of the Poisson statistic, justifying the Poisson approximation used in

Sect. 3.

The distribution of the simulated lightcurve describes the measured

histogram almost as well as the best-fit Gaussian (

.

As the simulated lightcurve incorporates a frequency spectrum of

similar shape as the data, the uncertainty levels of the simulation can

be used to estimate the uncertainty of each histogram bin of the data.

The standard deviation in the simulation in each bin was on the order

of the Poisson statistic, justifying the Poisson approximation used in

Sect. 3.

The distribution of the simulated lightcurve describes the measured

histogram almost as well as the best-fit Gaussian (

![]() in 84 bins, see Fig. 2).

in 84 bins, see Fig. 2).

5 Discussion and conclusion

5.1 Summary

We presented the first analysis of the statistical distribution of the brightness of Vela X-1, with special regard to the flaring behavior. Our main results are:

- The orbital phase averaged brightness distribution above 20 keV can be characterized by a log-normal distribution.

- The orbital phase resolved histograms indicate systematic variations besides the eclipse.

- The brightness distribution in the soft X-rays is strongly affected by absorption.

- Analysis of the soft X-rays confirm a decline in the average countrate with orbital phase.

- The brightness distribution of a simulated lightcurve consisting of a multiplication of individual random processes can be used to describe the data.

5.2 Giant flares

From our results obtained by analyzing 3.6 Ms of INTEGRAL

ISGRI data we can calculate the probability to measure extremely bright

flares in that time range. Extremely bright flares are defined by their

countrate being larger than 300 counts s-1

in the 20-60 keV band. The calculated probability is ![]() 0.011% for

the best-fit Gaussian, while it is

0.011% for

the best-fit Gaussian, while it is ![]() 0.023% for the simulated lightcurve. These

numbers agree well with

0.023% for the simulated lightcurve. These

numbers agree well with ![]() 0.02%

measured directly from our dataset. We conclude that bright flares are

rare, but not singular events. No separate process is required for

their explanation.

0.02%

measured directly from our dataset. We conclude that bright flares are

rare, but not singular events. No separate process is required for

their explanation.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{histo_alltimes_10_mdot.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa13981-09/Timg60.png)

|

Figure 6:

Histogram of the calculated

accretion rate |

| Open with DEXTER | |

5.3 Wind structure and accretion geometry

The origin of the constant flaring behavior lies in the accretion flow

onto the neutron star, which is obviously not smooth, but highly

structured. Neglecting any absorption and scattering effects, the

luminosity distribution gives us the opportunity of calculating the

mass distribution in this flow in units of mass per time. To calculate

the mass accretion rate it is necessary to know the absolute luminosity

of the X-ray source in the given energy band. As the luminosity is

strongly energy-dependent, we modeled the energy spectrum with a power

law with Fermi-Dirac-cutoff, using the parameters of Kreykenbohm et al. (2008),

who found these parameters for data from revolutions 137-141, which

were part of our analysis. The overall spectrum of our data could be

described with these values, too. With those parameters and a distance

of 2 kpc (Nagase

et al. 1986) the median absolute luminosity ![]() is

is ![]() .

.

During the accretion process only part of the potential energy

is converted to X-rays. We assume an accretion efficiency of ![]() and calculate the median accretion rate

and calculate the median accretion rate

The multiplicative standard deviation is

5.3.1 A clumpy wind

If we assume that the neutron stars accretes directly from the wind, we

can infer the mass distribution in the stellar wind from the accretion

rate. Strong density variations in the wind comparable to the

variations in the accretion rate can be described by a model of a

clumped stellar wind, a model based on instabilities in the the

line-driven acceleration mechanism (see, e.g., Feldmeier et al. 2003;

Dessart

& Owocki 2005; Oskinova et al. 2007).

A clumpy wind is also supported by observations. Based on ASCA

data, Sako et al. (1999)

show that the stellar wind of HD 77581 is most likely strongly

clumped by measuring line strengths in the spectra and showing that

these lines are only in accordance with a mass loss rate of ![]() when assuming a clumped wind, consisting of dense, cold clouds and a

hot, ionized surrounding medium. The clouds make up for about 90% of

the wind mass, while the hot ionized medium makes up for about 95% of

the volume, i.e., the volume filling factor of the clumps is fv=0.05.

(Sako et al. 2003).

Further evidence for clumping in the stellar wind was brought forth by

different authors using high-resolution Chandra

spectra (Goldstein

et al. 2004; Watanabe et al. 2006;

Schulz

et al. 2002). In these spectra emission lines from

H- and He-like ions indicate a hot thin gas. The spectra, however,

showed additionally strong fluorescent lines from lower ionized atoms,

e.g., of Fe, Mg, and Ne. These originate in colder, optically thick

plasma, which can be explained as clumps in the hot surrounding gas.

Additionally, if a dense clump is passing through the line of sight

between the observer and the X-ray emitting region, the absorption

coefficient will rise significantly. Clumps measured through absorption

dips (Nagase et al. 1986)

may very well be the same clumps that are accreted and are thus

directly responsible for luminosity fluctuations measurable up to at

least 100 keV (Sako

et al. 1999).

when assuming a clumped wind, consisting of dense, cold clouds and a

hot, ionized surrounding medium. The clouds make up for about 90% of

the wind mass, while the hot ionized medium makes up for about 95% of

the volume, i.e., the volume filling factor of the clumps is fv=0.05.

(Sako et al. 2003).

Further evidence for clumping in the stellar wind was brought forth by

different authors using high-resolution Chandra

spectra (Goldstein

et al. 2004; Watanabe et al. 2006;

Schulz

et al. 2002). In these spectra emission lines from

H- and He-like ions indicate a hot thin gas. The spectra, however,

showed additionally strong fluorescent lines from lower ionized atoms,

e.g., of Fe, Mg, and Ne. These originate in colder, optically thick

plasma, which can be explained as clumps in the hot surrounding gas.

Additionally, if a dense clump is passing through the line of sight

between the observer and the X-ray emitting region, the absorption

coefficient will rise significantly. Clumps measured through absorption

dips (Nagase et al. 1986)

may very well be the same clumps that are accreted and are thus

directly responsible for luminosity fluctuations measurable up to at

least 100 keV (Sako

et al. 1999).

The accretion of a clump or a similar dense feature in the

wind will lead to an increased X-ray luminosity of the source, i.e., a

flare. As the lightcurve of Vela X-1 is dominated by those

flares, which are strongly overlapping, it is hard to estimate the

length of any individual flare. Visual inspection of the lightcurve

indicates, however, that the shortest flares last around ![]() ks.

During that time

ks.

During that time ![]() g

of material will be accreted onto the neutron star, assuming the

average accretion ratio from Eq. (2). Using the

g

of material will be accreted onto the neutron star, assuming the

average accretion ratio from Eq. (2). Using the ![]() -law (Castor et al. 1975),

the average density at the neutron star orbit gives values of

-law (Castor et al. 1975),

the average density at the neutron star orbit gives values of ![]() .

In their simulations Blondin

et al. (1991,1990) showed that regions with

an overdensity of

.

In their simulations Blondin

et al. (1991,1990) showed that regions with

an overdensity of ![]() 100

are possible in the filaments of the accretion wake. Assuming a

spherical clump with such an increased density, i.e., a volume filling

factor fv=0.01

(Fullerton et al. 2006),

a radius of

100

are possible in the filaments of the accretion wake. Assuming a

spherical clump with such an increased density, i.e., a volume filling

factor fv=0.01

(Fullerton et al. 2006),

a radius of ![]() cm

is obtained. These clumps would show up in absorption with a maximal

column density of

cm

is obtained. These clumps would show up in absorption with a maximal

column density of ![]() ,

i.e., close to the observed absorption column (Kreykenbohm et al. 2008),

especially considering that more than one clump could be in the line of

sight at any given moment and that we assumed short flares, and

therefore small clumps.

,

i.e., close to the observed absorption column (Kreykenbohm et al. 2008),

especially considering that more than one clump could be in the line of

sight at any given moment and that we assumed short flares, and

therefore small clumps.

Besides the normal flares, giant flares are also visible in

the lightcurve and are more easily constrained in time. The largest

flare in the investigated lightcurve is at MJD 52 971.2,

lasting for 38 ks with an average count rate of ![]() 140 cps.

During that time

140 cps.

During that time ![]() g

were accreted, using the same conversion factor and efficiency as in

Eq. (2).

This mass is in the regime of the values given in numerous other works,

see for example Negueruela

et al. (2008) or Walter

& Zurita-Heras (2007). Note, however, that these

authors have investigated supergiant fast X-ray transients (SFXT), a

rather new class of X-ray sources. In a model proposed by Negueruela et al. (2006),

these SFXT are regarded as HMXB, similar to systems like

Vela X-1, with the orbit parameters being the major

difference. This similarity extends to similar companion stars, and

thus similar wind properties. The similar wind properties are also

evident in the irregular flaring behavior of the SFXT IGR J08408-4503,

which was explained by a clumpy wind (Leyder

et al. 2007). This explanation was also given for

the flaring behavior of ``regular'' HMXB (see, e.g., van der Meer et al. 2005)

and is supported by our analysis. We conclude that the calculated

clumpsizes and masses for SFXT can be very well compared with the

values of large clumps of Vela X-1.

g

were accreted, using the same conversion factor and efficiency as in

Eq. (2).

This mass is in the regime of the values given in numerous other works,

see for example Negueruela

et al. (2008) or Walter

& Zurita-Heras (2007). Note, however, that these

authors have investigated supergiant fast X-ray transients (SFXT), a

rather new class of X-ray sources. In a model proposed by Negueruela et al. (2006),

these SFXT are regarded as HMXB, similar to systems like

Vela X-1, with the orbit parameters being the major

difference. This similarity extends to similar companion stars, and

thus similar wind properties. The similar wind properties are also

evident in the irregular flaring behavior of the SFXT IGR J08408-4503,

which was explained by a clumpy wind (Leyder

et al. 2007). This explanation was also given for

the flaring behavior of ``regular'' HMXB (see, e.g., van der Meer et al. 2005)

and is supported by our analysis. We conclude that the calculated

clumpsizes and masses for SFXT can be very well compared with the

values of large clumps of Vela X-1.

5.3.2 Temporal smearing

In the previous section we showed that the clump distribution is probably roughly log-normal. If true, this result contradicts to typical assumptions for mass distributions in the atmospheres of high-mass stars, where power-law distributions are generally assumed (e.g., Kostenko & Kholtygin 1999). But it is unlikely that the distribution of clumps in the stellar atmosphere translates directly to a distribution of accretion rate from the wind, because temporal smearing is taking place during accretion. If the clump mass distribution in the wind would be indeed log-normal, smearing could lead to small deviations from this log-normal distribution in the measured brightness distribution. We tried to analyze the effect of smearing by folding the simulated lightcurve with an exponential function with a characteristic timescale. Due to the log-normal character of the lightcurve, strong smearing leads to a higher average countrate, which disagrees with the measured lightcurve distribution. We therefore included another fit parameter, allowing the renormalization of the simulated lightcurve. With this method we could find no reliable timescale for the smearing, because our time resolution was limited to 283.5 s and all emerging fit values were of the order of or lower than that resolution. The analysis of a lightcurve with higher time resolution of 20 s, but with a moving average of 283.5 s applied to smooth out the intrinsic pulse variations came to the same result: the smearing timescale is around the level of the time resolution and thus not significant. From this simulation we can conclude that smearing cannot account for a measurable amount of deviation from the initial distribution of the clump sizes. From the observer's point of view we note that Vela X-1 shows no evidence for an accretion disk, which would show up in the soft X-rays as a blackbody component. The spin period evolution also shows no evidence for an accretion disk, as the pulse period is changing erratically rather than with a constant trend, which would be expected from the continuous transform of angular momentum from an accretion disk (Ghosh & Lamb 1979; Deeter et al. 1989). This lack of an accretion disk supports the argument of a short smearing timescale, because the accretion timescale is also short.

5.3.3 Shock structures and grinding

We did not find in the literature any discussion covering the distribution of clump masses in these systems. Assuming that the clumps are log-normal distributed is therefore at the moment an ad hoc assumption and not explained by the models. In this section we will describe a possible mechanism to generate log-normal distributions. To do this, we will first take a closer look at the different features in the accretion region.

Simulations by Blondin et al. (1991,1990)

and recently by Mauche

et al. (2008) have shown that a shock front forms in

front of the neutron star, together with an accretion wake and a

possible photoionization wake, as the neutron star ploughs with

supersonic motion through the stellar wind of the companion star. These

features induce additional variability of the X-ray flux over the

orbit, an effect we have seen in Sect. 3.2. Even

though photoabsorption is negligible at the energies under

consideration, Thomson scattering is not. The Thomson cross section

depends only weakly on the photon energy, and Thomson scattering can

scatter a considerable amount of X-rays out of the line of sight. As

shown by Hanke et al. (2008),

deep scattering troughs can be measured in INTEGRAL

data of Cygnus X-1, which are ascribed to a large, hot clump passing

through the line of sight. From the variations of the median of the

orbital-phase-resolved histograms we can calculate the necessary

electron column to induce these changes and, assuming ISM abundances,

the corresponding ![]() value. The values obtained were on the order of

value. The values obtained were on the order of ![]() ,

depending on the energy band used. Compared to that, the average

,

depending on the energy band used. Compared to that, the average ![]() expected from the stellar wind is

expected from the stellar wind is ![]() ,

assuming a wind density profile following a

,

assuming a wind density profile following a ![]() -law (Castor

et al. 1975) with

-law (Castor

et al. 1975) with ![]() .

This result is confirmed by measurements of the X-ray spectrum, which

also give values in the regime of

.

This result is confirmed by measurements of the X-ray spectrum, which

also give values in the regime of ![]() (e.g., Kreykenbohm

et al. 1999). Assuming that the variations in our

data are solely caused by scattering, the column density must increase

up to a factor

(e.g., Kreykenbohm

et al. 1999). Assuming that the variations in our

data are solely caused by scattering, the column density must increase

up to a factor ![]() 50

compared to the average wind. In simulations by Blondin et al. (1991,1990)

regions with up to 100 times the density of the ambient wind are seen,

which would lead to clumps with radii

50

compared to the average wind. In simulations by Blondin et al. (1991,1990)

regions with up to 100 times the density of the ambient wind are seen,

which would lead to clumps with radii ![]() cm

and large masses on the order of 1024 g,

assuming spherical clumps. The donor star itself has only a radius of

cm

and large masses on the order of 1024 g,

assuming spherical clumps. The donor star itself has only a radius of ![]() cm,

making those clumps unrealistically large. The observed variations are

thus unlikely to be induced by scattering alone.

cm,

making those clumps unrealistically large. The observed variations are

thus unlikely to be induced by scattering alone.

The powerful structures in the accretion region will not only change the column density, but will also influence the mass distribution itself. All mass has to pass at least one shock wave and will be subject to strong turbulence prior to accretion. Blondin et al. (1991) have shown that Rayleigh-Taylor instabilities will rise inside the bow shock region, producing overdense eddies and vortices, e.g., structures similar to clumps. It is also very probable that the mass distribution will be changed during this shock transition, as clumps can not only be produced, but large clumps of the stellar wind will be broken up into smaller pieces. Breaking up large clumps is a multiplicative process, and thus forms a log-normal distribution, which is long known in geoscience for the distribution of rocks and sand grains (Smith & Jordan 1964, and references therein). Kevlahan & Pudritz (2009) have shown that shocks in the interstellar medium can lead to a log-normal density distribution as well.

Shock fronts and turbulence breaking up clumps can transfer

any given distribution into a log-normal like distribution. The

emerging masses of the clumps are uncertain however and need more and

detailed simulations. A clumpy wind, with huge clumps with masses of at

least 1022 g, which is subject to

shocks and turbulence grinding down these huge clumps to masses of ![]() g,

could therefore be a realistic picture of the accretion geometry. The

clump distribution in the wind, however, would be transformed to a

log-normal distribution of the accreted mass by means of the accretion

processes, which we can see in the X-ray luminosity.

g,

could therefore be a realistic picture of the accretion geometry. The

clump distribution in the wind, however, would be transformed to a

log-normal distribution of the accreted mass by means of the accretion

processes, which we can see in the X-ray luminosity.

5.3.4 Outlook

Our analysis allows us for the first time to investigate the structure of the wind in an energy band above 20 keV. This structure has not been investigated so far in this energy band in systems like Vela X-1, but shows similar results of a strongly structured wind as other investigations (e.g., Sako et al. 1999). It is remarkable that the brightness distribution of the black hole HMXB Cygnus X-1 shows a similar behavior. Although these systems produce their radiation through different processes, the emerging distribution is also log-normal, as shown for short time-scales by Uttley & McHardy (2001) and Gleissner et al. (2004). Poutanen et al. (2008) were able to extend this result to longer time-scales. While our results improve our understanding of the physical processes behind the variations of the luminosity and the structure of the accreted mass, they do not allow to infer where the structure originates from, i.e., from clumps in the stellar wind or from effects during the accretion process. Further investigations should include more detailed models of the brightness distribution and extensive magneto-hydrodynamic simulations of the accretion geometry and the influence of the neutron star on the wind. We propose that a strongly structured wind, with clumps of the masses around 1020 g is accreted onto the neutron star, and thereby subject to shocks and turbulence. These disturbances can lead to a log-normal distribution in accreted masses, which translates directly to the observed luminosity distribution.

In addition, a similar analysis should be performed for other

systems, providing more information about that class of objects and

their possible connection to SFXT. For example, a preliminary look at

4U 1909+07 (![]() X1908+07,

Wen et al. 2000) has

shown that the brightness distribution of this system is following a

roughly log-normal distribution as well.

X1908+07,

Wen et al. 2000) has

shown that the brightness distribution of this system is following a

roughly log-normal distribution as well.

This work was supported by the Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Technologie through DLR grant 50 OR 0808 and via a DAAD fellowship. This work has been partially funded by the European Commission under the 7th Framework Program under contract ITN 215212. F.F. thanks the colleagues at UCSD and GSFC for their hospitality. We thank M. A. Nowak and A. Pollock for the useful discussions. For this work we used the ISIS software package provided by MIT. We especially like to thank J. C. Houck and J. E. Davis for their restless work to improve ISIS and S-Lang. This research has made use of NASA's Astrophysics Data System. This work is based on observations with INTEGRAL, an ESA project with instruments and science data centre funded by ESA member states (especially the PI countries: Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Switzerland, Spain), Czech Republic and Poland, and with the participation of Russia and the USA. We used the archival data from the ASM Light Curve web page, developed by the ASM team at the Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. We thank the anonymous referee for her/his useful comments.

References

- Ahrens, L. H. 1954, Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 5, 49 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Blondin, J. M., Kallman, T. R., Fryxell, B. A., & Taam, R. E. 1990, ApJ, 356, 591 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Blondin, J. M., Stevens, I. R., & Kallman, T. R. 1991, ApJ, 371, 684 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bondi, H., & Hoyle, F. 1944, MNRAS, 104, 273 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Castor, J. I., Abbott, D. C., & Klein, R. I. 1975, ApJ, 195, 157 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chodil, G., Mark, H., Rodrigues, R., et al. 1967, ApJ, 150, 57 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, K., & Ostriker, J. P. 1973, ApJ, 179, 585 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Deeter, J. E., Boynton, P. E., Lamb, F. K., & Zylstra, G. 1989, ApJ, 336, 376 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dessart, L., & Owocki, S. P. 2005, A&A, 437, 657 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Eadie, G., Peacock, A., Pounds, K. A., et al. 1975, MNRAS, 172, 35P [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmeier, A., Oskinova, L., & Hamann, W. 2003, A&A, 403, 217 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton, A. W., Massa, D. L., & Prinja, R. K. 2006, ApJ, 637, 1025 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fürst, F., Kreykenbohm, I., Wilms, J., et al. 2008, in Proceedings of the 7th INTEGRAL Workshop - An INTEGRAL View of Compact Objects, ed. S. Brandt, N. J. Westergaard, & N. Lund [Google Scholar]

- Gehrels, N. 1986, ApJ, 303, 336 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, P., & Lamb, F. K. 1979, ApJ, 234, 296 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gleissner, T., Wilms, J., Pottschmidt, K., et al. 2004, A&A, 414, 1091 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, G., Huenemoerder, D. P., & Blank, D. 2004, ApJ, 127, 2310 [Google Scholar]

- Haberl, F., & White, N. E. 1990, ApJ, 361, 225 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hanke, M., Wilms, J., Boeck, M., et al. 2008, in Proceedings of the 7th Microquasar Workshop., Foça, Turkey PoS MQW7:029 [Google Scholar]

- Kaper, L., Hammerschlag-Hensberge, G., & Zuiderwijk, E. J. 1994, A&A, 289, 846 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Kevlahan, N., & Pudritz, R. E. 2009, ApJ, 702, 39 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kostenko, F. V., & Kholtygin, A. F. 1999, Astrophysics, 42, 280 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kretschmar, P., Kreykenbohm, I., Wilms, J., et al. 2008, in Proceedings of the 7th INTEGRAL Workshop - An INTEGRAL View of Compact Objects, ed. S. Brandt, N. J. Westergaard, & N. Lund [Google Scholar]

- Kreykenbohm, I., Kretschmar, P., Wilms, J., et al. 1999, A&A, 341, 141 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Kreykenbohm, I., Wilms, J., Kretschmar, P., et al. 2008, A&A, 492, 511 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Lebrun, F., Leray, J. P., Lavocat, P., et al. 2003, A&A, 411, L141 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Levine, A. M., Bradt, H., Cui, W., et al. 1996, ApJ, 469, L33 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Leyder, J. C., Walter, R., Lazos, M., et al. 2007, A&A, 465, L35 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Lund, N., Budtz-Jørgensen, C., Westergaard, N. J., et al. 2003, A&A, 411, L231 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Mauche, C. W., Liedahl, D. A., Akiyama, S., & Plewa, T. 2008, in Cool Discs, Hot Flows: The Varying Faces of Accreting Compact Objects, ed. M. Axelsson, Stockholm, Sweden, AIP Conf. Proc., 1054, 3 [Google Scholar]

- McClintock, J. E., Rappaport, S., Joss, P. C., et al. 1976, ApJ, 206, L99 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mowlavi, N., Kreykenbohm, I., Shaw, S. E., et al. 2006, A&A, 451, 187 [Google Scholar]

- Nagase, F., Hayakawa, S., Sato, N., et al. 1986, PASJ, 38, 547 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Negueruela, I., Smith, D. M., Reig, P., et al. 2006, in Proceedings of The X-ray Universe 2005, Madrid, ed. A. Wilson (Noordwijk: ESA Publ. Div), ESA-SP, 604, 165 [Google Scholar]

- Negueruela, I., Torrejon, J. M., Reig, P., et al. 2008, in A Population Explosion: The Nature & Evolution of X-ray Binaries in Diverse Environments, ed. R. Bandyopadhyay, St. Pete Beach, Florida, AIP Conf. Proc., 1010, 252 [Google Scholar]

- Oskinova, L. M., Hamann, W., & Feldmeier, A. 2007, A&A, 476, 1331 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Poutanen, J., Zdziarski, A. A., & Ibragimov, A. 2008, MNRAS, 389, 1427 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Quaintrell, H., Norton, A. J., Ash, T. D. C., et al. 2003, A&A, 401, 313 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Renaud, M., Gros, A., Lebrun, F., et al. 2006, A&A, 456, 389 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Sako, M., Liedahl, D. A., Kahn, S. M., & Paerels, F. 1999, ApJ, 525, 921 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sako, M., Kahn, S. M., Paerels, F., et al. 2003, in Proceedings of the High-resolution X-ray Spectroscopy Workshop with XMM-Newton and Chandra, MSSL, Holmbury St Mary, ed. G. Branduardi-Raymont [Google Scholar]

- Schanne, S., Gotz, D., Gerard, L., et al. 2007, in Proceedings of the 6th INTEGRAL Workshop, Moscow (Noordwijk: ESA Publ. Div.), ESA SP-622, 479 [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, N. S., Canizares, C. R., Lee, J. C., & Sako, M. 2002, ApJ, 564, L21 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J. E., & Jordan, M. L. 1964, J. Colloid Sci., 19, 549 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Staubert, R., Kreykenbohm, I., Kretschmar, P., et al. 2004, in 5th INTEGRAL Workshop on the INTEGRAL Universe, ed. V. Schönfelder, G. Lichti, C. Winkler (Noordwijk: ESA Publ. Div.), ESA-SP, 552, 259 [Google Scholar]

- Timmer, J., & König, M. 1995, A&A, 300, 707 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Ubertini, P., Lebrun, F., Di Cocco, G., et al. 2003, A&A, 411, L131 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Uttley, P., & McHardy, I. M. 2001, MNRAS, 323, L26 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Uttley, P., McHardy, I. M., & Vaughan, S. 2005, MNRAS, 359, 345 [Google Scholar]

- van der Meer, A., Kaper, L., Salvo, T. D., et al. 2005, A&A, 432, 999 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- van Kerkwijk, M. H., van Paradijs, J., Zuiderwijk, E. J., et al. 1995, A&A, 303, 483 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Vedrenne, G., Roques, J. P., Schönfelder, V., et al. 2003, A&A, 411, L63 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Walter, R., & Zurita-Heras, J. 2007, A&A, 476, 335 [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, S., Sako, M., Ishida, M., et al. 2006, ApJ, 651, 421 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wen, L., Remillard, R. A., & Bradt, H. V. 2000, ApJ, 532, 1119 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wen, L., Levine, A. M., Corbet R. H. D., & Bradt, H. V. 2006, ApJS, 163, 372 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, C., Courvoisier T. J. L., Di Cocco, G., et al. 2003, A&A, 411, L1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

All Tables

Table 1: Overview of the INTEGRAL data of Vela X-1.

Table 2: Fit parameters of the PSD (Fig. 5).

All Figures

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{aa13981-09-fig1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa13981-09/Timg12.png)

|

Figure 1: Top: lightcurve in the 20-60 keV band. The vertical dashed lines show the start and the end of the eclipse according to the ephemeris of Kreykenbohm et al. (2008), and the dash-dotted line shows the respective center of eclipse. Bottom: simulated lightcurve with the same statistical parameters and temporal resolution as the observed lightcurve above, but without eclipses. See text for details. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{aa13981-09-fig2.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa13981-09/Timg13.png)

|

Figure 2: Histogram of the lightcurve of the 20-60 keV band, binned to 256 bins. The solid curve shows the best-fit single Gaussian, the dash-dotted one the histogram of the simulated lightcurve as described in the text. The dotted histogram to the left shows the noise level of the background. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{aa13981-09-fig3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa13981-09/Timg32.png)

|

Figure 3: Landscape plot of orbital phase resolved histograms of the ISGRI 20-60 keV data. Color-coded is the probability for a datapoint to fall into the respective histogram bin. The black line shows the median count rate in each phase bin. Uncertainties of that value are also plotted, but they are too small to be clearly visible in this plot. Note that the same histograms are shown twice for clarity. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{aa13981-09-fig4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa13981-09/Timg34.png)

|

Figure 4: Same as Fig. 3, but for the ASM data in the 1.5-5 keV (top) and 5-10 keV band (middle). The bottom panel shows the hardness ratio, overplotted is the median of the distribution. Data in the eclipse were ignored. A clear trend to a harder spectrum at late orbital phases is visible. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{aa13981-09-fig5.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa13981-09/Timg39.png)

|

Figure 5:

Showcase PSD of Vela X-1 from Revs 373-383 in the

20-100 keV ISGRI band. The red curve shows the best-fit model,

as described in the text. The blue power law continuum has a |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{histo_alltimes_10_mdot.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/11/aa13981-09/Timg60.png)

|

Figure 6:

Histogram of the calculated

accretion rate |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

Copyright ESO 2010

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.