| Issue |

A&A

Volume 517, July 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A96 | |

| Number of page(s) | 37 | |

| Section | Interstellar and circumstellar matter | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200913501 | |

| Published online | 17 August 2010 | |

A line confusion limited millimeter survey of Orion KL I.

Sulfur carbon chains![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

B. Tercero - J. Cernicharo - J. R. Pardo - J. R. Goicoechea

Centro de Astrobiología (CSIC-INTA), Departamento de Astrofísica Molecular, Ctra. de Aljalvir Km 4, 28850 Torrejón de Ardoz, Madrid, Spain

Received 19 October 2009 / Accepted 15 April 2010

Abstract

We perform a sensitive (line confusion limited), single-side

band spectral survey towards Orion KL with the IRAM 30 m

telescope, covering the following frequency ranges: 80-115.5 GHz,

130-178 GHz, and 197-281 GHz. We detect more than

14 400 spectral features of which 10 040 have been

identified up to date and attributed to 43 different

molecules, including 148 isotopologues and lines from

vibrationally excited

states. In this paper, we focus on the study of OCS, HCS+, H2CS, CS, CCS, C3S, and their isotopologues.

In addition, we map the OCS J=18-17 line

and complete complementary observations of several

OCS lines at selected positions around Orion IRc2 (the position

selected for the survey).

We report the first detection of

OCS ![]() and

and ![]() vibrationally

excited states in space and the first detection of C3S in warm clouds.

Most of CCS, and almost all C3S, line emission arises from

the hot core indicating an enhancement of their abundances in warm and

dense gas.

Column densities and isotopic ratios have been calculated

using a large velocity gradient (LVG) excitation and radiative transfer

code (for the low density gas components) and a local thermal equilibrium

(LTE) code (appropriate for the warm and dense hot core component), which takes

into account the different

cloud components known to exist towards Orion KL,

the extended ridge,

compact ridge, plateau, and hot

core.

The vibrational temperature derived from OCS

vibrationally

excited states in space and the first detection of C3S in warm clouds.

Most of CCS, and almost all C3S, line emission arises from

the hot core indicating an enhancement of their abundances in warm and

dense gas.

Column densities and isotopic ratios have been calculated

using a large velocity gradient (LVG) excitation and radiative transfer

code (for the low density gas components) and a local thermal equilibrium

(LTE) code (appropriate for the warm and dense hot core component), which takes

into account the different

cloud components known to exist towards Orion KL,

the extended ridge,

compact ridge, plateau, and hot

core.

The vibrational temperature derived from OCS ![]() and

and ![]() levels is

levels is ![]() 210 K, similar to the gas kinetic

temperature in the hot core. These OCS high energy levels are

probably

pumped by absorption of IR dust photons.

We derive an upper limit to the OC3S,

H2CCS, HNCS,

HOCS+, and NCS column densities.

Finally, we discuss the D/H abundance ratio and

infer the following isotopic abundances:

12C/13C =

210 K, similar to the gas kinetic

temperature in the hot core. These OCS high energy levels are

probably

pumped by absorption of IR dust photons.

We derive an upper limit to the OC3S,

H2CCS, HNCS,

HOCS+, and NCS column densities.

Finally, we discuss the D/H abundance ratio and

infer the following isotopic abundances:

12C/13C = ![]() ,

32S/34S =

,

32S/34S = ![]() ,

32S/33S =

,

32S/33S = ![]() ,

and 16O/18O =

,

and 16O/18O =

![]() .

.

Key words: surveys - stars: formation - ISM: abundances - ISM: clouds - ISM: molecules - radio lines: ISM

1 Introduction

The Orion KL (Kleinmann-Low) cloud is the closest (![]() 414 pc,

Menten et al. 2007)

and most well studied

high mass star-forming region in our Galaxy (see, e. g.,

Genzel & Stutzki 1989 for review).

The prevailing chemistry of

the cloud is particularly complex as a result of the interaction of the

newly formed protostars, outflows, and their environment. The

evaporation of dust

mantles and the high gas temperatures

produce a wide variety of molecules

in the gas phase that are responsible for a spectacularly prolific and intense

line spectrum (Blake et al. 1987; Charnley 1997; Brown et al. 1988).

414 pc,

Menten et al. 2007)

and most well studied

high mass star-forming region in our Galaxy (see, e. g.,

Genzel & Stutzki 1989 for review).

The prevailing chemistry of

the cloud is particularly complex as a result of the interaction of the

newly formed protostars, outflows, and their environment. The

evaporation of dust

mantles and the high gas temperatures

produce a wide variety of molecules

in the gas phase that are responsible for a spectacularly prolific and intense

line spectrum (Blake et al. 1987; Charnley 1997; Brown et al. 1988).

Near- and mid-IR subarcsecond

resolution imaging and (sub)millimeter interferometric

observations have identified the main sources of

luminosity, heating, and dynamics in the region.

At first, IRc2 was believed to be the responsible for

this complex environment.

However, the 8-12 ![]() m emission

peak of IRc2 is not coincident with the

the origin of the outflow(s) (and the Orion SiO maser origin),

and its intrinsic IR luminosity (

m emission

peak of IRc2 is not coincident with the

the origin of the outflow(s) (and the Orion SiO maser origin),

and its intrinsic IR luminosity (

![]() )

is only a fraction of the luminosity of the entire system (Gezari et al. 1998).

In addition,

3.6-22

)

is only a fraction of the luminosity of the entire system (Gezari et al. 1998).

In addition,

3.6-22 ![]() m images indicate that IRc2 is resolved into

four non self-luminous components.

Therefore, IRc2 is not presently the powerful engine

of Orion KL and its nature

remains unclear (Dougados et al. 1993; Greenhill et al. 2004; Shuping et al. 2004).

Menten & Reid (1995) identified

the very embedded radio continuum source I (a young star

with a very high luminosity without an infrared

counterpart,

m images indicate that IRc2 is resolved into

four non self-luminous components.

Therefore, IRc2 is not presently the powerful engine

of Orion KL and its nature

remains unclear (Dougados et al. 1993; Greenhill et al. 2004; Shuping et al. 2004).

Menten & Reid (1995) identified

the very embedded radio continuum source I (a young star

with a very high luminosity without an infrared

counterpart, ![]() 10

10

![]() ,

Greenhill et al. 2004; Gezari et al. 1998, located

,

Greenhill et al. 2004; Gezari et al. 1998, located

![]() south of IRc2) as the source coinciding with the

centroid of the SiO maser distribution (Goddi et al. 2009b; Plambeck et al. 2009; Zapata et al. 2009a).

They also detected the radio continuum emission of IR

source n, suggesting this source as another precursor

of the large-scale phenomena.

In addition, Beuther et al. (2004) detected a sub-millimeter source without

IR and centimeter counterparts, SMA1, previously predicted

by de Vicente et al. (2002), which may be the source

driving the high velocity outflow (Beuther & Nissen 2008).

Thus, the core of Orion KL

contains the compact HII regions I and n (in addition to BN,

which was resolved with high resolution at 7 mm by Rodríguez et al. 2009),

which appear to be receding from a common point,

an originally massive stellar system that

disintegrated

south of IRc2) as the source coinciding with the

centroid of the SiO maser distribution (Goddi et al. 2009b; Plambeck et al. 2009; Zapata et al. 2009a).

They also detected the radio continuum emission of IR

source n, suggesting this source as another precursor

of the large-scale phenomena.

In addition, Beuther et al. (2004) detected a sub-millimeter source without

IR and centimeter counterparts, SMA1, previously predicted

by de Vicente et al. (2002), which may be the source

driving the high velocity outflow (Beuther & Nissen 2008).

Thus, the core of Orion KL

contains the compact HII regions I and n (in addition to BN,

which was resolved with high resolution at 7 mm by Rodríguez et al. 2009),

which appear to be receding from a common point,

an originally massive stellar system that

disintegrated ![]() 500 years ago (Zapata et al. 2009b; Gómez et al. 2005).

Finally, submm aperture synthesis

line surveys provided the spatial location

and extent of many molecular species (Goddi et al. 2009b; Wright et al. 1996; Beuther et al. 2005; Plambeck et al. 2009; Liu et al. 2002; Zapata et al. 2009a; Blake et al. 1996).

500 years ago (Zapata et al. 2009b; Gómez et al. 2005).

Finally, submm aperture synthesis

line surveys provided the spatial location

and extent of many molecular species (Goddi et al. 2009b; Wright et al. 1996; Beuther et al. 2005; Plambeck et al. 2009; Liu et al. 2002; Zapata et al. 2009a; Blake et al. 1996).

The chemical complexity of Orion KL has been demonstrated by

several line surveys performed

at different frequency ranges: 72.2-91.1 GHz by Johansson et al. (1984);

215-247 GHz by Sutton et al. (1985); 247-263 GHz by Blake et al. (1986); 200.7-202.3,

203.7-205.3 and 330-360 GHz by Jewell et al. (1989); 70-115 GHz by Turner (1989);

257-273 GHz by Greaves & White (1991); 150-160 GHz by Ziurys & McGonagle (1993);

325-360 GHz by Schilke et al. (1997);

607-725 GHz by Schilke et al. (2001); 138-150 GHz by Lee et al. (2001);

159.7-164.7 GHz by

Lee & Cho (2002); 455-507 GHz by White et al. (2003); 795-903 GHz

by Comito et al. (2005); 44-188 ![]() m by Lerate et al. (2006); 486-492, 541-577 GHz by Olofsson et al. (2007) and Persson et al. (2007); and 42.3-43.6 GHz by Goddi et al. (2009a).

m by Lerate et al. (2006); 486-492, 541-577 GHz by Olofsson et al. (2007) and Persson et al. (2007); and 42.3-43.6 GHz by Goddi et al. (2009a).

In spite of this large amount of data, no line confusion limited survey

has been carried out so far with a large single dish telescope.

We performed such a line survey

towards Orion IRc2 with the IRAM 30-m

telescope at wide frequency

ranges (a total frequency coverage of ![]() 168 GHz).

Our main goal was to obtain a deep insight into the

molecular content and chemistry of Orion KL, an archetype high

mass star-forming region (SFR), and to improve our knowledge of its

prevailing physical conditions. It also allows us to search for new

molecular species and new isotopologues, as well as the rotational

emission of vibrationally excited

states of molecules already known to exist in this source. Since the

amount and complexity of the data is large, we divided

our analysis into families of molecules so that model development and discussions

could be more focused. In this paper,

we concentrate

on sulfur carbon chains, in particular carbonyl sulfide OCS

(see previous studies by Goldsmith & Linke 1981; Evans II et al. 1991;

Wright et al. 1996;

Charnley 1997), CS (previously analyzed by Hasegawa et al. 1984;

Murata et al. 1991; Zeng & Pei 1995; Wright et al. 1996;

Johnstone et al. 2003), H2CS (Minh et al. 1991; Gardner et al. 1984), HCS+,

CCS, CCCS, and their isotopologues.

168 GHz).

Our main goal was to obtain a deep insight into the

molecular content and chemistry of Orion KL, an archetype high

mass star-forming region (SFR), and to improve our knowledge of its

prevailing physical conditions. It also allows us to search for new

molecular species and new isotopologues, as well as the rotational

emission of vibrationally excited

states of molecules already known to exist in this source. Since the

amount and complexity of the data is large, we divided

our analysis into families of molecules so that model development and discussions

could be more focused. In this paper,

we concentrate

on sulfur carbon chains, in particular carbonyl sulfide OCS

(see previous studies by Goldsmith & Linke 1981; Evans II et al. 1991;

Wright et al. 1996;

Charnley 1997), CS (previously analyzed by Hasegawa et al. 1984;

Murata et al. 1991; Zeng & Pei 1995; Wright et al. 1996;

Johnstone et al. 2003), H2CS (Minh et al. 1991; Gardner et al. 1984), HCS+,

CCS, CCCS, and their isotopologues.

Column density calculations, and therefore the estimation of isotopic abundance ratios and molecular excitation, have improved, with respect to previous works, due to the much larger number of available lines, their consistent calibration across the explored frequency range, the up-to-date information about the physical properties of the region and molecular constants, and the use of a LVG radiative transfer code to derive reliable physical and chemical parameters. Modeled brightness temperatures obtained from a fit to all observed lines have been convolved with the telescope beam profile, assuming a given size for each cloud component, to provide accurate source-averaged, and not beam-averaged, molecular column densities.

After presenting the line survey (Sects. 2 and 3), this work concentrates on the detection of OCS, HCS+, H2CS, CS, CCS, and CCCS lines and their analysis, as well as providing upper limits to the abundance of several non-detected sulfur-carbon-chain bearing molecules such us OC3S, H2CCS, HNCS, HOCS+, and NCS (Sects. 4 to 7). This is the first of a series of papers dedicated to the analysis of the millimeter emission from different molecular families towards Orion KL.

2 Observations and data analysis

Table 1:

![]() and HPBW along the covered frequency range.

and HPBW along the covered frequency range.

The observations were carried out using the IRAM 30 m radiotelescope

during September 2004 (3 mm and 1.3 mm windows), March 2005 (full 2 mm

window),

April 2005 (completion of 3 mm and 1.3 mm windows), and January 2007 (maps and

pointed observations at particular positions). Four SiS receivers

operating at 3, 2, and 1.3 mm were used

simultaneously with image sideband rejections within 20-27 dB

(3 mm receivers),

12-16 dB (2 mm receivers) and ![]() 13 dB

(1.3 mm receivers). System temperatures were in the

range 100-350 K for the 3 mm receivers, 200-500 K

for the 2 mm receivers, and 200-800 K for the 1.3 mm

receivers, depending on the particular frequency, weather conditions,

and source elevation. For frequencies

in the range 172-178 GHz, the system temperature was significantly

higher, 1000-4000 K, due to proximity of the atmospheric water

line at 183.31 GHz. The intensity scale was calibrated using

two absorbers at

different temperatures and the atmospheric transmission model (ATM, Cernicharo 1985; Pardo et al. 2001). Table 1 shows the variation in the main beam efficiency (

13 dB

(1.3 mm receivers). System temperatures were in the

range 100-350 K for the 3 mm receivers, 200-500 K

for the 2 mm receivers, and 200-800 K for the 1.3 mm

receivers, depending on the particular frequency, weather conditions,

and source elevation. For frequencies

in the range 172-178 GHz, the system temperature was significantly

higher, 1000-4000 K, due to proximity of the atmospheric water

line at 183.31 GHz. The intensity scale was calibrated using

two absorbers at

different temperatures and the atmospheric transmission model (ATM, Cernicharo 1985; Pardo et al. 2001). Table 1 shows the variation in the main beam efficiency (

![]() )

and the half power beam width (HPBW)

across the covered frequency range.

The error beam contribution to the observed line intensities

is negligible for heavy polyatomic molecules because their emission

originates in a compact region. However, the error beam contribution of

the low-J line extended emission of abundant species (HCO+, HCN, CN or CS) can be significant (up to

)

and the half power beam width (HPBW)

across the covered frequency range.

The error beam contribution to the observed line intensities

is negligible for heavy polyatomic molecules because their emission

originates in a compact region. However, the error beam contribution of

the low-J line extended emission of abundant species (HCO+, HCN, CN or CS) can be significant (up to ![]() 10-20% of the observed intensities at 1 mm). Deriving the correct brightness temperature for these lines

requires large-scale mapping.

10-20% of the observed intensities at 1 mm). Deriving the correct brightness temperature for these lines

requires large-scale mapping.

Pointing and focus were regularly

checked on the nearby quasars 0420-014 and 0528+134. Observations

were made in the balanced wobbler-switching mode, with a wobbling frequency

of 0.5 Hz and a beam throw in azimuth of ![]() 240''.

No contamination from the off position affected our observations

except for a marginal one at the lowest elevations (

240''.

No contamination from the off position affected our observations

except for a marginal one at the lowest elevations (![]() 25

25![]() )

for

molecules showing low J emission along the extended ridge.

)

for

molecules showing low J emission along the extended ridge.

Two filter banks with

![]() MHz channels and a

correlator providing two 512 MHz bandwidths and

1.25 MHz resolution were used as backends. We pointed

towards IRc2 source at

MHz channels and a

correlator providing two 512 MHz bandwidths and

1.25 MHz resolution were used as backends. We pointed

towards IRc2 source at

![]() ,

,

![]() (J2000.0)

corresponding to

the ``survey position''. We observed two additional

positions to target

both the compact ridge (

(J2000.0)

corresponding to

the ``survey position''. We observed two additional

positions to target

both the compact ridge (

![]() ,

,

![]() )

and the ambient molecular cloud

(

)

and the ambient molecular cloud

(

![]() ,

,

![]() ). Figure 15 of Wright et al. (1996) shows a 3 mm dust image

depicting all positions quoted above.

). Figure 15 of Wright et al. (1996) shows a 3 mm dust image

depicting all positions quoted above.

The spectra shown in all figures are in units of antenna temperature,

![]() ,

corrected for atmospheric absorption and spillover losses. In spite of the

good receiver image-band rejection, each setting was repeated

at a slightly shifted frequency (10-20 MHz)

to manually identify and remove all features arising from the image side band.

The spectra from different frequency settings were used to identify all

potential contaminating lines from the image side band. In some

cases, it was impossible to eliminate the contribution of the image

side band and we removed the signal in those contaminated channels

leaving holes in

the data. The total frequencies blanked this way represent less than 0.5% of the total frequency coverage. Figure 1 shows our

procedure for removing the image side band lines.

We removed most of the features above a 0.05 K threshold.

,

corrected for atmospheric absorption and spillover losses. In spite of the

good receiver image-band rejection, each setting was repeated

at a slightly shifted frequency (10-20 MHz)

to manually identify and remove all features arising from the image side band.

The spectra from different frequency settings were used to identify all

potential contaminating lines from the image side band. In some

cases, it was impossible to eliminate the contribution of the image

side band and we removed the signal in those contaminated channels

leaving holes in

the data. The total frequencies blanked this way represent less than 0.5% of the total frequency coverage. Figure 1 shows our

procedure for removing the image side band lines.

We removed most of the features above a 0.05 K threshold.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13501fg01.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa13501-09/Timg28.png)

|

Figure 1: The top panel shows two superimposed spectra corresponding to different frequency settings (112 500 and 112 520 MHz). The 40 MHz displaced line is the 115.5 GHz CO line in the image side band. The bottom panel shows the final spectrum resulting from our procedure to eliminate the image side band (see text, Sect. 2). We are confident that all lines above 0.05 K have frequencies correctly assigned. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

3 The line survey

Within the 168 GHz bandwidth covered, we detected more than

14 400 spectral features of which 10 040 were already

identified and attributed to 43 molecules, including 148 different

isotopologues

and vibrationally excited states.

Any feature covering more than 3-4 channels and of intensity

greater than 0.02 K is above 3![]() and is considered to be a line

in our survey. The noise was difficult to derive

from the data because of the high density of lines. We computed it from

the

observing time and the system temperature.

In the 2 mm and 1.3 mm windows, the features weaker than

0.1 K have not yet been systematically analyzed,

except when searching for isotopic species with good

laboratory frequencies.

We thus expect to considerably increase the number of both identified

and

unidentified lines. We note that the number of U lines was

initially much larger. Identification of some isotopologues of most

abundant species (see below) allowed us to reduce the number of

U-lines at a rate of

and is considered to be a line

in our survey. The noise was difficult to derive

from the data because of the high density of lines. We computed it from

the

observing time and the system temperature.

In the 2 mm and 1.3 mm windows, the features weaker than

0.1 K have not yet been systematically analyzed,

except when searching for isotopic species with good

laboratory frequencies.

We thus expect to considerably increase the number of both identified

and

unidentified lines. We note that the number of U lines was

initially much larger. Identification of some isotopologues of most

abundant species (see below) allowed us to reduce the number of

U-lines at a rate of ![]() 500 lines per year.

We used standard procedures to identify lines above 0.2 K including

all possible contributions (taking into account the energy of the transition

and the line strength) from different species.

Thanks to the wide frequency coverage of our survey, many rotational

lines were observed for each species, hence it is possible to estimate the

contribution of a given molecule to the intensity of a spectral feature

where several lines from different species are blended.

We applied this procedure to all our previous

line surveys with the 30 m telescope (e.g., Cernicharo et al. 2000).

500 lines per year.

We used standard procedures to identify lines above 0.2 K including

all possible contributions (taking into account the energy of the transition

and the line strength) from different species.

Thanks to the wide frequency coverage of our survey, many rotational

lines were observed for each species, hence it is possible to estimate the

contribution of a given molecule to the intensity of a spectral feature

where several lines from different species are blended.

We applied this procedure to all our previous

line surveys with the 30 m telescope (e.g., Cernicharo et al. 2000).

As an example of the scope of this line survey in the field of molecular spectroscopy, Demyk et al. (2007), Margulès et al. (2009), Carvajal et al. (2009), and Margulès et al. (2010) identified more than 600, 100, 600, and 100 lines from the 13C and 15N isotopologues of CH3CH2CN, the 13C isotopologues of HCOOCH3, and CH3OCOD, respectively. Many of the remaining U-lines are certainly due to isotopologues of other abundant species.

Figures 2, 4, and 6 show the whole data set of this Orion KL line survey at 3 mm, 2 mm and 1.3 mm respectively. Figures 3, 5, and 7 show 1 GHz wide spectra as an example in each window. We have marked the identified features with labels (molecule and transition quantum numbers) and the strongest unidentified ones as ``U''. In each figure, the top panels display the total intensity range, while the middle and the bottom ones show different zoomed images of the intensity range.

Because of the large amount of line features in the spectra, and to follow the most efficient strategy for the line identification process, we decided to proceed in steps by studying the different molecular families including all possible isotopologues and vibrationally excited states. We continue to analyze our line survey data, which we expect to make public, with all line identifications, by 2011.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=270,

width=17cm,clip]{13501fg02.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa13501-09/Timg30.png)

|

Figure 2:

Molecular line survey of Orion KL at 3 mm. The top panel shows the total intensity scale; the middle and the bottom panels show a zoom of the total intensity. A

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=16cm,clip]{13501fg03n.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa13501-09/Timg31.png)

|

Figure 3: Example of Orion's KL survey at 3 mm with 1 GHz bandwidth. The top panel shows the total intensity scale; the middle and the bottom panels show a zoom of the total intensity. Detected molecules are marked with labels and some unidentified features are marked as U. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[%

width=16cm,clip]{13501fg04n.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa13501-09/Timg32.png)

|

Figure 4: Molecular line survey of Orion KL at 2 mm presented similarly to Fig. 2. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=270,width=17cm,clip]{13501fg05.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa13501-09/Timg33.png)

|

Figure 5: Example of Orion's KL survey at 2 mm with 1 GHz bandwidth. The top panel shows the total intensity scale; the middle and the bottom panels show a zoom of the total intensity. Detected molecules are marked with labels and some unidentified lines are marked as U. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=17cm,clip]{13501fg06n.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa13501-09/Timg34.png)

|

Figure 6: Molecular line survey of Orion KL at 1.3 mm presented similarly to Fig. 2. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=17cm,clip]{13501fg07n.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa13501-09/Timg35.png)

|

Figure 7: Example of the Orion KL survey at 1.3 mm with 1 GHz bandwidth. The top panel shows the total intensity scale; the middle and the bottom panels show a zoom of the total intensity. Detected molecules are labeled and some unidentified lines are marked as U. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

In agreement with previous works, four different spectral cloud components are

generally defined in the analysis of low angular resolution line

surveys where different physical components overlap in the beam. These

components are characterized by different physical and chemical conditions

(Blake et al. 1987,1996):

(i) a narrow or ``spike'' (![]() 5 km s-1 line-width)

component at

5 km s-1 line-width)

component at

![]() km s-1 delineating a north-to-south

extended ridge or ambient cloud; (ii) a compact and quiescent

region, the compact ridge, (

km s-1 delineating a north-to-south

extended ridge or ambient cloud; (ii) a compact and quiescent

region, the compact ridge, (

![]() km s-1,

km s-1,

![]() km s-1) identified for the first time by

Johansson et al. (1984); (iii) the plateau a mixture of outflows,

shocks, and interactions with the ambient cloud

(

km s-1) identified for the first time by

Johansson et al. (1984); (iii) the plateau a mixture of outflows,

shocks, and interactions with the ambient cloud

(

![]() km s-1,

km s-1,

![]() km s-1); (iv) a hot core component (

km s-1); (iv) a hot core component (

![]() km s-1,

km s-1,

![]() km s-1) first detected

in ammonia emission Morris et al. (1980). Table 2

gives the physical parameters that we obtained for each

component from the modeling of the OCS, HCS+, H2CS, CS, CCS,

and CCCS line emission

(Sect. 5). The assumption of a single gas temperature and

density for each cloud component is

the greatest simplification of our methodology.

It is clear that the source

structure identified by much higher angular resolution interferometric

observations is far more complex than assumed in Table 2.

We attempted to use more complex structures using density and temperature

gradients, but the comparison with the data indicate that we do not have enough

information to fit these physical gradients, even when we have many lines for

some species. Therefore, we fix the physical properties to be those given in

Table 2

(values derived from our data analysis) to ensure that we have only one

free parameter (the column density) when modeling the spectral lines.

Nevertheless, our multi-source excitation and radiative transfer approach

represents a major improvement on previous works based on LTE

analysis.

km s-1) first detected

in ammonia emission Morris et al. (1980). Table 2

gives the physical parameters that we obtained for each

component from the modeling of the OCS, HCS+, H2CS, CS, CCS,

and CCCS line emission

(Sect. 5). The assumption of a single gas temperature and

density for each cloud component is

the greatest simplification of our methodology.

It is clear that the source

structure identified by much higher angular resolution interferometric

observations is far more complex than assumed in Table 2.

We attempted to use more complex structures using density and temperature

gradients, but the comparison with the data indicate that we do not have enough

information to fit these physical gradients, even when we have many lines for

some species. Therefore, we fix the physical properties to be those given in

Table 2

(values derived from our data analysis) to ensure that we have only one

free parameter (the column density) when modeling the spectral lines.

Nevertheless, our multi-source excitation and radiative transfer approach

represents a major improvement on previous works based on LTE

analysis.

4 Results

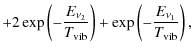

4.1 OCS

Table 2: The assumed Orion KL spectral components.

Carbonyl sulfide (OCS) has a linear structure and, because of its

rotational constant (B=5932.83 MHz for 16O12C32S),

it harbours

up to 15 transitions per vibrational state that can be observed in the

covered frequency range. Line detections in our survey include the ground

vibrational state of 6 isotopologues (OCS, OC34S, OC33S,

O13CS, 18OCS, O13C34S), plus two vibrationally

excited states of the main

isotopologue (![]() ,

,

![]() ). The last two were detected

here for the first time in space. Only a tentative detection is

presented for 17OCS and OC36S because of the

weakness of the features and/or their overlap with other spectral

lines.

). The last two were detected

here for the first time in space. Only a tentative detection is

presented for 17OCS and OC36S because of the

weakness of the features and/or their overlap with other spectral

lines.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=14cm,clip]{13501fg08.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa13501-09/Timg48.png)

|

Figure 8:

Observed (offseted histogram) and model

(thin curves) OCS, OC34S and OC33S lines.

A

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=14cm,clip]{13501fg09.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa13501-09/Timg49.png)

|

Figure 9:

Observed lines (offseted histogram) and model (thin

curves) of OCS |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The rotational constants used to derive the line frequencies

were taken from

Golubiatnikov et al. (2005) (OCS), the NIST triatomic molecules database (OC34S and

O13CS), Burenin et al. (1981b) (OC33S), Burenin et al. (1981a) (all the others OCS

isotopologues), and Morino et al. (2000) (OCS vibrationally excited states). The

OCS dipole moment (![]() = 0.7152D) was assumed to be that measured by

Tanaka et al. (1985). Observed line

parameters and intensities are given in Table 3. Figures 8, A.1 and 9 show the lines

that are not blended with features from other species and our

best-fit-model line profiles

(see Sect. 5.1). The line profiles and intensities show the

contribution from the extended and compact molecular ridges,

the plateau, and the hot core. In previous line surveys, the

extended ridge component was discarded as a significant source of OCS

line emission. However, we include it here as a requirement to reproduce the

observed intensities from J = 7-6 up to

J = 23-22 (main and rare

isotopologues).

= 0.7152D) was assumed to be that measured by

Tanaka et al. (1985). Observed line

parameters and intensities are given in Table 3. Figures 8, A.1 and 9 show the lines

that are not blended with features from other species and our

best-fit-model line profiles

(see Sect. 5.1). The line profiles and intensities show the

contribution from the extended and compact molecular ridges,

the plateau, and the hot core. In previous line surveys, the

extended ridge component was discarded as a significant source of OCS

line emission. However, we include it here as a requirement to reproduce the

observed intensities from J = 7-6 up to

J = 23-22 (main and rare

isotopologues).

To constrain the model more tightly, and determine the spatial distribution of the OCS line emission, we obtained a map of the OCS J = 18-17 line and performed sensitive observations of several lines at selected positions around Orion IRc2. Figure A.2 shows the observed line profiles and integrated line intensity spatial distribution. Figure 10 shows the line emission for different velocity ranges.

The maximum integrated intensity lies approximately 3'' southwest of IRc2 (see Fig. A.2) and is a mixture

of compact ridge and hot core components, in agreement with the

spatial distribution found by Wright et al. (1996).

The velocity structure of the OCS emission depicted in Fig. 10 shows all the cloud spectral components discussed

above. The spatial distribution of the red

wing (

![]() km s-1) of the J = 18-17 line emission is

particularly interesting. It traces an elliptical expanding shell of

gas around IRc2, the low-velocity outflow.

The front of the

shell is traced by the emission at velocities from -10 to -1 km s-1 (blue wing),

while the red part of the shell appears at 20-25 km s-1.

km s-1) of the J = 18-17 line emission is

particularly interesting. It traces an elliptical expanding shell of

gas around IRc2, the low-velocity outflow.

The front of the

shell is traced by the emission at velocities from -10 to -1 km s-1 (blue wing),

while the red part of the shell appears at 20-25 km s-1.

The observed lines at

selected positions are shown in Fig. 11. Altogether, these data

allow us to study the hot core, the compact ridge, and the extended

ridge. Sutton et al. (1995) also observed the OCS J = 28-27 line at

different positions. OCS line intensities are clearly

brighter towards the

compact ridge position than towards IRc2 (hot core).

The antenna temperature measured towards the extended ridge

position is ![]() 1 K; however, the extended ridge contribution

towards IRc2 should be larger to explain the data (see Sect. 5.1).

1 K; however, the extended ridge contribution

towards IRc2 should be larger to explain the data (see Sect. 5.1).

Table 3: OCS observed line parameters.

Table 4 gives the parameters of the OCS lines derived by fitting Gaussian profiles to all velocity components with the CLASS software![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=18cm,clip]{13501fg10n.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa13501-09/Timg57.png)

|

Figure 10: OCS J = 18-17 integrated line intensity maps at different velocity ranges (indicated at the top of each panel). The integrated intensity of the maps has been multiplied by a scale factor (indicated in the panels) to maintain the same color dynamics for all maps. The interval of contours is 10 K km s-1, the minimum contour is 30 K km s-1 for the maps with velocities between -1 and 11 km s-1 and 50 K km s-1 for the rest of the panels. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=11.5cm,clip]{13501fg11.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa13501-09/Timg58.png)

|

Figure 11:

Some lines of OCS, OC34S

and O13CS observed at different positions which correspond

with different components of Orion KL. A

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Table 4: OCS velocity components from Gaussian fits.

4.2 HCS+

Four transitions of thioformyl cation (HCS+) were detected in the

covered frequency range.

Line frequencies and observational parameters are given in Table B.2, only available online, which contains the following

information: Col. 1

gives the observed (centroid) radial velocities, Col. 2 the

peak line temperature, Col. 3 the integrated line intensity, Col.

4 the quantum numbers, Col. 5 the

assumed rest frequencies, Col. 6 the energy of the upper level, and

Col. 7 the line strength. Rotational constants were derived from the

rotational lines reported by Margulès et al. (2003).

The adopted dipole moment,

![]() D, is taken from Botschwina & Sabald (1985).

Line profiles and our best-fit models (see Sect. 5.2) are shown

in Fig. A.3.

D, is taken from Botschwina & Sabald (1985).

Line profiles and our best-fit models (see Sect. 5.2) are shown

in Fig. A.3.

The HCS+ line profiles display the four Orion's spectra components. In this case, the contribution of the extended ridge component is very weak (see Sect. 5.2).

4.3 H2CS

We detected several transitions of thioformaldehyde (45 transitions of ortho and para states). We also detected H2C34S, H213CS (both p- and o- states) and HDCS isotopologues.

Line parameters are given in Table B.3,

only available online, which contains the following

information: Col. 1 indicates the isotopologue or the vibrational

state, Col. 2

gives the observed (centroid) radial velocities, Col. 3 the

peak line temperature, Col. 4 the integrated line intensity, Col. 5 the quantum numbers, Col. 6 the

assumed rest frequencies, Col. 7 the energy of the upper level, and

Col. 8 the line strength. Figures A.4-A.7

show the lines that are

not blended with other species and our best-fit model

(see Sect. 5.3).

The rotational constants used to derive the line frequencies were

taken from the CDMS

Catalog![]() for

H2CS (Maeda et al. 2008) and H213CS.

The H2CS dipole moment,

for

H2CS (Maeda et al. 2008) and H213CS.

The H2CS dipole moment, ![]() .6491D, is the one measured by Fabricant et al. (1977).

For H2C34S (ortho and para) and HDCS, the line parameters were

fitted from all rotational lines reported by Minowa et al. (1997)

and the observed lines towards B1 dark cloud by Marcelino et al. (2005).

For HDCS, a small

.6491D, is the one measured by Fabricant et al. (1977).

For H2C34S (ortho and para) and HDCS, the line parameters were

fitted from all rotational lines reported by Minowa et al. (1997)

and the observed lines towards B1 dark cloud by Marcelino et al. (2005).

For HDCS, a small

![]() dipole moment is expected, which we

assumed to be identical to that of HDCO.

dipole moment is expected, which we

assumed to be identical to that of HDCO.

Line profiles and intensities indicate contributions from the extended ridge, compact ridge (very prominent), the plateau, and the hot core.

Table B.4, only available online, provides the parameters of selected

lines of H2CS and its isotopologues obtained assuming Gaussian

fits to the line profiles. We show only one narrow component fit

(a blend of

compact ridge, extended ridge, and hot core)

because the wide component (plateau) cannot be fitted due to blending with

other species. The main component contribution is the compact ridge.

We note that for H2CS (ortho and para),

![]() ,

and

,

and ![]() tend to values similar to these of the hot core when the

tend to values similar to these of the hot core when the ![]() quantum

number increases.

quantum

number increases.

4.4 CS

Three transitions (J = 2-1,

3-2, 5-4) of carbon monosulfide substitutions C32S, C34S,

and C33S along with four lines

of 13CS and 13C34S (J = 2-1, 3-2, 5-4, 6-5)

were detected.

For C36S, 13C33S, and vibrationally excited CS

(v=1), we present only tentative detections.

Line frequencies and observational

parameters are given in Table B.5,

only available online,

which contains the following information: Column 1 indicates the

isotopologue or the vibrational state, Col. 2 gives the observed

(centroid) radial velocities, Col. 3 the peak line temperature,

Col. 4 the integrated line intensity, Col. 5 the quantum

numbers, Col. 6 the

assumed rest frequencies, Col. 7 the energy of the upper level,

and

Col. 8 the line strength. Line profiles for transitions that are

not blended with other features

are shown in Fig. A.8. The spectroscopic constants

for CS and C34S are taken from Gottlieb et al. (2003), those of 13CS,

C33S, C36S, 13C34S, and 13C33S from

Ahrens & Winnewisser (1998), and those of CS v=1

come from Kim & Yamamoto (2003). Dipole moments (![]() .958D for CS

v=0 and

.958D for CS

v=0 and ![]() .936D for CS

v=1) were taken from Winnewisser & Cook (1968).

.936D for CS

v=1) were taken from Winnewisser & Cook (1968).

Line profiles from the most abundant isotopologues display the four Orion KL spectral components. At 3 mm and 2 mm, the ridge and the plateau emission dominate, at 1 mm the presence of the hot core component in the line profile is very significant. For the less abundant isotopologues (C36S, 13C34S and 13C33S), the compact ridge and hot core components are responsible for most of the line emission. The emission of CS vibrationally excited states comes mainly from the hot core component.

Line parameters for CS, C34S, C33S, 13CS, and 13C34S are given in Table B.6, only available online.

4.5 CCS

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=13.5cm,clip]{13501fg12.eps}\vspace*{-2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa13501-09/Timg64.png)

|

Figure 12:

Observed lines (offseted histogram) and model (thin

curves) of CCS. A

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

The CCS radical (![]() ground electronic state) has several transitions

in the surveyed frequency range. Detected lines and main spectroscopic

parameters are given in Table B.7, only available online,

containing the following information: Col. 1

gives the observed (centroid) radial velocities, Col. 2 the

peak line temperature, Col. 3 the quantum numbers, Col. 4 the

assumed rest frequencies, Col. 5 the energy of the upper level, and

Col. 6 the line strength. Rotational constants were

taken from Yamamoto et al. (1990) and the dipole moment,

ground electronic state) has several transitions

in the surveyed frequency range. Detected lines and main spectroscopic

parameters are given in Table B.7, only available online,

containing the following information: Col. 1

gives the observed (centroid) radial velocities, Col. 2 the

peak line temperature, Col. 3 the quantum numbers, Col. 4 the

assumed rest frequencies, Col. 5 the energy of the upper level, and

Col. 6 the line strength. Rotational constants were

taken from Yamamoto et al. (1990) and the dipole moment,

![]() D,

comes from Lee (1997).

Figure 12 shows the detected transitions that are unaffected by

line overlap.

D,

comes from Lee (1997).

Figure 12 shows the detected transitions that are unaffected by

line overlap.

Owing to the line emission weakness, it is difficult to

distinguish the different spectral cloud components in the observed line

profiles. To reproduce the line

intensities (see Sect. 5.5), we assumed that the hot

core component is

responsible for most of the observed emission. However, the line velocity

centroid indicates that both the extended and compact ridge components

also contribute at

the observed emission. Ziurys & McGonagle (1993) found the same

velocity components in their CCS observed lines

(one detected and two tentative).

The much lower abundances of CCS isotopologues and of

vibrationally excited CCS prevent us from detecting any of their transitions above the

line confusion limit.

4.6 C3S

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=14cm,clip]{13501fg13.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/09/aa13501-09/Timg67.png)

|

Figure 13:

Observed lines (offseted histogram) and model (thin

curves) of C3S. A

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Previously, C3S has been observed in cold dark clouds (Kaifu et al. 1987) and in the envelopes of C-rich AGB stars (Bell et al. 1993; Cernicharo et al. 1987a). Sutton et al. (1995) found a possible spectral line towards Orion hot core and compact ridge positions, but its identification as the C3S J=58-57 line was discarded because of the high energy level (475 K).

We report the first detection of C3S in warm

clouds. We clearly

identified 17 of the 29 rotational transitions covered in the survey.

The remaining transitions are blended

with lines of other species. Figure 13 shows

several C3S detected lines. Line parameters are

given in Table B.8, which is only available online, containing the

following information: Col. 1

gives the observed (centroid) radial velocities, Col. 2 the

peak line temperature, Col.

3 the quantum numbers, Col. 4 the

assumed rest frequencies, Col. 5 the energy of the upper level, and

Col. 6 the line strength. Rotational constants were taken

from Yamamoto et al. (1987) and the dipole moment (

![]() D) was assumed to be that

measured by Suenram & Lovas (1994). The line centroid velocity

indicates that the emission mainly arises from the hot core. As

for CCS, we could not detect any C3S isotopologues or vibrationally

excited states.

D) was assumed to be that

measured by Suenram & Lovas (1994). The line centroid velocity

indicates that the emission mainly arises from the hot core. As

for CCS, we could not detect any C3S isotopologues or vibrationally

excited states.

5 Determination of column densities

For all detected species column densities were calculated using an excitation and radiative transfer code developed by J. Cernicharo (Cernicharo 2010, in preparation). Depending on either the selected molecule or physical conditions, we followed either a LVG (Sobolev 1958; Sobolev 1960) or LTE approach. For each cloud component, we assumed uniform physical conditions for the kinetic temperature, density, radial velocity, and line width (Table 2). We adopted these values from the data analysis (Gaussian fits and an attempt to simulate the line widths and intensities with LTE and LVG codes) as representative parameters for the different species. When a change in these values was required (e.g. C3S analysis), we indicate this in the text. Our modeling technique also takes into account the size of each component and its offset position with respect IRc2. Corrections for beam dilution were applied to each line depending on their frequency. The only free parameter is therefore the column density of the corresponding observed species. Taking into account the compact nature of most cloud components, the contribution from the error beam is negligible except for the extended ridge, which has a small contribution for all observed lines.

In addition to line opacity effects, other sources of uncertainty are related to the following:

- adopting uniform physical conditions assumes that the physical structure of the cloud is simplified. However, parameters such as the size, kinetic temperature, and density gradients of the different components of the cloud are difficult to assess from low resolution single-dish observations. This problem can be partially overcome by analyzing many different molecular species and transitions covering a broad range of excitation conditions, as allowed by our line survey;

- the angular resolution of any single-dish line survey is modest. Therefore, the emission from different physical components is usually blended and cannot be separated. However, important efforts have been made to separate them spectrally thanks to the availability of a large number of lines from different isotopologues and vibrational states (different opacity regimes) and a wide frequency range (different source coupling regimes);

- pointing errors, as small as 2'', could introduce important changes in the contribution from each cloud component to the observed line profiles, especially at 1.3 mm. However, the modeled and observed line profiles never differ by more than 20%, which is compatible with the absolute calibration error of our line survey (estimated to be about 15%).

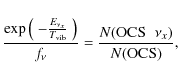

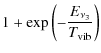

5.1 OCS

Table 5: Column densities - OCS.

Detailed multi-source LVG excitation and radiative transfer

calculations were performed to fit

the OCS line emission from the extended ridge, compact ridge, and

plateau. Given the lower density in these components

(similar or lower than the critical densities of the observed OCS transitions),

the OCS level populations should be far from LTE, thus the LVG

calculation is

much more appropriately adapted to interpreting the data correctly.

Collisional cross-sections of OCS-H2 are

taken from Green & Chapman (1978), which were calculated

for temperatures in the range 10-100 K including levels up to J=13. In addition, we included levels up to J = 40 in our models.

Collisional rates for J >13 levels

were derived using the energy sudden approximation (Goldflam et al. 1977)

and using the ![]() (

(![]() ;

;

![]() )

rates. The

LTE approximation was assumed for both the hot core and

vibrationally excited OCS.

For OCS

)

rates. The

LTE approximation was assumed for both the hot core and

vibrationally excited OCS.

For OCS ![]() = 1 and OCS

= 1 and OCS ![]() ,

we changed the velocity width parameter

for the hot core component (

,

we changed the velocity width parameter

for the hot core component (

![]() km s-1) with respect

to the value given in Table 2 to provide

a closer accurate fit to the line profiles.

km s-1) with respect

to the value given in Table 2 to provide

a closer accurate fit to the line profiles.

The beam coupling strongly affects the observed OCS lines in the

different frequency ranges. At 1.3 mm,

![]() ,

we lose most of the compact ridge

emission when pointing to IRc2.

Moreover, the different gas components are not always

centered on the beam. Our model takes into account all these spatial

structure effects. As an example, Fig. 10 shows the OCS emission at different velocities, with

the result that at velocities of between 7 and 11 km s-1, the OCS emission peak is out side the

telescope beam at 1.3 mm.

,

we lose most of the compact ridge

emission when pointing to IRc2.

Moreover, the different gas components are not always

centered on the beam. Our model takes into account all these spatial

structure effects. As an example, Fig. 10 shows the OCS emission at different velocities, with

the result that at velocities of between 7 and 11 km s-1, the OCS emission peak is out side the

telescope beam at 1.3 mm.

Although the relatively low dipole moment of OCS (0.715 D,

Tanaka et al. 1985)

helps to keep these lines optically thin, some of them, especially

at the higher end of the explored J range, may be optically thick

(Schilke et al. 1997; Ziurys & McGonagle 1993).

The opacities were taken into account

by the LVG and LTE codes. However, both LVG and LTE approximations

are more appropriate for optically thin

emission; hence, the column density for the main

isotopologue obtained with our LVG or LTE calculations should be

considered as a lower limit. The derived column densities

from the lines shown in Figs. 8, A.1, and 9 are given in Table 5. We also derived

the column density of OCS indirectly by means of the column density of its less

abundant isotopologues to assess the line opacity effect

(OC34S and O13CS assuming

isotopic abundances of 32S/34S = 20 and 12C/13C = 45;

the adopted isotopic abundances are an average of the values

obtained in this work, see

Sect. 6).

Owing to the low intensity

of the lines belonging to these other less abundant isotopologues,

implying larger overlap

problems, we can only get upper limits for their column density. We

estimate the uncertainty to be in the range 20-30% for the results of

OCS, O13CS,

OC34S, and OCS ![]() and around 50% for

OC33S, 18OCS, and OCS

and around 50% for

OC33S, 18OCS, and OCS ![]() .

.

The OCS column density derived from the isotopologue emission

in the compact ridge and the hot core

is four times higher than the column densities obtained

from the lines of the main isotopologue. It appears

that the OCS lines emerging from the hot core and the compact ridge are

saturated, this is consistent with the optical depth

estimation of Schilke et al. (1997) for the 29-28 transition of OCS

(![]() assuming 32S/34S = 22.5).

For the plateau and the extended ridge, we obtained similar

column densities using both methods indicating that the

OCS main isotopologue emission towards these components

is optically thin.

assuming 32S/34S = 22.5).

For the plateau and the extended ridge, we obtained similar

column densities using both methods indicating that the

OCS main isotopologue emission towards these components

is optically thin.

Table 6: Column densities - H2CS.

The component with the highest OCS column density corresponds to the hot core with N(OCS)We estimated a difference varying from 5% to 15%, depending on the molecule, between LTE or LVG (for molecules having collisional rates available) results.

5.2 HCS+

We determine the HCS+ column density using collisional rates HCS+-He from Monteiro (1984).

To reproduce the line profiles more accurately, we changed the

![]() of the compact ridge given in Table 2,

adopting

of the compact ridge given in Table 2,

adopting

![]() km s-1.

The modeled lines are shown in Fig. A.3 (thin curves).

We obtain the following column densities:

km s-1.

The modeled lines are shown in Fig. A.3 (thin curves).

We obtain the following column densities:

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() cm-2 for the hot core, plateau, compact ridge, and

extended ridge, respectively. To reproduce the 3 mm line of HCS+, we had to significantly reduce the

extended ridge column density with respect to the values of the other

components. The HCS+ column density towards the hot core has to be

considered with caution because of its weak line emission

contribution.

cm-2 for the hot core, plateau, compact ridge, and

extended ridge, respectively. To reproduce the 3 mm line of HCS+, we had to significantly reduce the

extended ridge column density with respect to the values of the other

components. The HCS+ column density towards the hot core has to be

considered with caution because of its weak line emission

contribution.

Based on the observed values of

![]() (

(![]() 9 km s-1)

and

9 km s-1)

and ![]() (

(![]() 4 km s-1) and the reduced fractional

ionization in the

high density gas, Johansson et al. (1984), Blake et al. (1986), and Schilke et al. (1997) exclusively

attributed the emission of

this molecule to the extended ridge. These first two sets of authors reported

beam-average column densities of

4 km s-1) and the reduced fractional

ionization in the

high density gas, Johansson et al. (1984), Blake et al. (1986), and Schilke et al. (1997) exclusively

attributed the emission of

this molecule to the extended ridge. These first two sets of authors reported

beam-average column densities of

![]() (Johansson et al. 1984) and

(Johansson et al. 1984) and

![]() cm-2 (Blake et al. 1986).

Sutton et al. (1995) found emission of HCS+ from the five positions of

their survey (extended ridge, hot core, compact ridge, northwest

plateau, and southeast plateau); they obtained beam-averaged column

densities of N(HCS

cm-2 (Blake et al. 1986).

Sutton et al. (1995) found emission of HCS+ from the five positions of

their survey (extended ridge, hot core, compact ridge, northwest

plateau, and southeast plateau); they obtained beam-averaged column

densities of N(HCS

![]() cm-2 for the extended ridge and N(HCS

cm-2 for the extended ridge and N(HCS

![]() cm-2for the remaining positions.

Schilke et al. (2001) found a questionable assignment of HCS+ J=16-15 (

cm-2for the remaining positions.

Schilke et al. (2001) found a questionable assignment of HCS+ J=16-15 (

![]() K, emission coming from the hot core).

K, emission coming from the hot core).

To compare the abundances of different molecular ions,

we calculated the column density of

H13CO+, assuming the same physical conditions we adopted

for HCS+. As a total column density (sum of all components), we derive

N(H13CO

![]() cm-2;

considering an isotopic

abundance 12C/13C = 45 (see Sect. 6), we obtain

N(HCO+)/N(HCS

cm-2;

considering an isotopic

abundance 12C/13C = 45 (see Sect. 6), we obtain

N(HCO+)/N(HCS

![]() .

A similar value was given by

Johansson et al. (1984) (in the extended ridge component), whereas Blake et al. (1986)

obtained N(HCO+)/N(HCS

.

A similar value was given by

Johansson et al. (1984) (in the extended ridge component), whereas Blake et al. (1986)

obtained N(HCO+)/N(HCS

![]() (the H13CO+ line was strongly blended with

HCOOCH3 and its

(the H13CO+ line was strongly blended with

HCOOCH3 and its ![]() * was estimated by subtracting the

contribution of methyl formate from the overall emission).

Assuming that the main production and destruction mechanisms for

HCO+ and HCS+ are the reaction of H3+ with CO and CS and

the dissociative recombination of HCO+ and HCS+ with electrons,

we deduce that in chemical equilibrium N(CS)/N(CO

* was estimated by subtracting the

contribution of methyl formate from the overall emission).

Assuming that the main production and destruction mechanisms for

HCO+ and HCS+ are the reaction of H3+ with CO and CS and

the dissociative recombination of HCO+ and HCS+ with electrons,

we deduce that in chemical equilibrium N(CS)/N(CO

![]() (HCS+)/N(HCO+)

(HCS+)/N(HCO+)

![]() (see Sect. 5.4 for the

obtained CO/CS abundance ratio).

(see Sect. 5.4 for the

obtained CO/CS abundance ratio).

5.3 H2CS

Table 7: Ortho/Para ratios - H2CS.

Owing to the lack of collisional rates for this molecule,

we assumed LTE excitation in the H2CS column density calculations. Figures A.4-A.7

show the modeled line profiles (thin curves) for selected lines of H2CS,

H2C34S, H213CS, and HDCS. Results

are given in Table 6.

The higher column densities correspond to the the compact ridge

and the hot core component (

![]() and

and

![]() ,

respectively). The hot core is primarily

responsible for the

line emission from transitions with

,

respectively). The hot core is primarily

responsible for the

line emission from transitions with

![]() .

Our column density

results agree with those

obtained in previous studies (Schilke et al. 1997; Sutton et al. 1995;

Turner 1991; Blake et al. 1987; Sutton et al. 1985).

.

Our column density

results agree with those

obtained in previous studies (Schilke et al. 1997; Sutton et al. 1995;

Turner 1991; Blake et al. 1987; Sutton et al. 1985).

Since we derived the ortho- and para- H2CS column densities

independently, we also computed the ortho-to-para ratios

of this molecule for the different components (Table 7). The hottest, densest component

(hot core)

has an ortho-to-para ratio ![]() 1.8

1.8 ![]() 0.7, whereas the extended ridge (the

coldest, least dense component) has a ratio

0.7, whereas the extended ridge (the

coldest, least dense component) has a ratio ![]() 3

3 ![]() 1. Taking

into account the uncertainties in these ratios, we conclude that the

ratio is compatible with the statistical weight of 3.

1. Taking

into account the uncertainties in these ratios, we conclude that the

ratio is compatible with the statistical weight of 3.

Assuming the same hypothesis than for H2CS, we derived a

H213CO column density of ![]()

![]() cm-2 (sum of all components). Adopting the isotopic abundance

12C/13C = 45 (see Sect. 6), we derive

N(H2CO)/N(H2CS

cm-2 (sum of all components). Adopting the isotopic abundance

12C/13C = 45 (see Sect. 6), we derive

N(H2CO)/N(H2CS

![]() ,

very close to

the ratio N(HCO+)/N(HCS+) calculated in the previous

section. Unlike H2CO, for which efficient gas-phase synthetic

pathways have been studied in the laboratory, analogous reactions

that might form thioformaldehyde do not occur. As an example, the

chemical model of

Nomura & Millar (2004) cannot reproduce, by several order of magnitudes, the

observed N(H2CO)/N(H2CS) abundance ratio in hot cores.

,

very close to

the ratio N(HCO+)/N(HCS+) calculated in the previous

section. Unlike H2CO, for which efficient gas-phase synthetic

pathways have been studied in the laboratory, analogous reactions

that might form thioformaldehyde do not occur. As an example, the

chemical model of

Nomura & Millar (2004) cannot reproduce, by several order of magnitudes, the

observed N(H2CO)/N(H2CS) abundance ratio in hot cores.

5.4 CS

Table 8: Column densities of CS, CS isotopologues, and CS vibrationally excited.

Our CS column densities were derived using collisional CS-H2 rates from Lique & Spielfiedel (2007). They are given in Table 8 and the modeled line profiles are shown in Fig. A.8.

The CS lines are optically thick and therefore the column density

for each cloud component may be significantly underestimated. Lines from

CS isotopologues

are, however, optically thin so that we can estimate the

column density of CS by assuming a value for the isotopic ratios. Assuming

32S/34S = 20 (see Sect. 6), the column density

of CS in the hot core component is

![]() cm-2.

A value 2 times larger is obtained if we assume that

12C/13C = 45 (see Sect. 6). On average, we

obtain N(CS)

cm-2.

A value 2 times larger is obtained if we assume that

12C/13C = 45 (see Sect. 6). On average, we

obtain N(CS)

![]() cm-2.

This CS column density is about 10-30 times larger than

found in many previous studies (Lee et al. 2001; Blake et al. 1987; Schilke et al. 2001).

In these earlier studies, the results were beam-averaged CS

column densities derived from a LTE

analysis. Sutton et al. (1995) obtained a corrected-source-averaged

column density of

cm-2.

This CS column density is about 10-30 times larger than

found in many previous studies (Lee et al. 2001; Blake et al. 1987; Schilke et al. 2001).

In these earlier studies, the results were beam-averaged CS

column densities derived from a LTE

analysis. Sutton et al. (1995) obtained a corrected-source-averaged

column density of

![]() cm-2 for the hot core,

in agreement with both our result and the source-averaged

CS column density obtained by Comito et al. (2005).

cm-2 for the hot core,

in agreement with both our result and the source-averaged

CS column density obtained by Comito et al. (2005).

For the less abundant isotopologues (13C33S, C36S) and for CS vibrationally excited states, we can only derive upper limits due to the weakness of the lines and the large overlap with other features (see Fig. A.8, bottom panels. Among the three lines of CS v=1, only one seems to be detected).

The components with the largest CS column density are the hot core and the plateau, the latter having the larger value. However, in the emission of the CS isotopologues the hot core dominates (in agreement with Schilke et al. 2001).

To compare the CS and CO abundances, we

calculated the column density of C18O in each component. We

obtain N(C18O) of

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() cm-2 for the

extended ridge, compact ridge, plateau, and hot core, respectively.

We have to include a

high velocity plateau component with

cm-2 for the

extended ridge, compact ridge, plateau, and hot core, respectively.

We have to include a

high velocity plateau component with

![]() ,

,

![]() km s-1, and a column density of

km s-1, and a column density of

![]() cm-2 to

reproduce the line profiles. Assuming the isotopic

abundance 16O/18O = 250 (see Sect. 6),

we determine the column density of CO in each

component to be

cm-2 to

reproduce the line profiles. Assuming the isotopic

abundance 16O/18O = 250 (see Sect. 6),

we determine the column density of CO in each

component to be

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() for the extended ridge, compact ridge, plateau, hot core, and high

velocity plateau, respectively. Therefore, the corresponding

N(CS)/N(CO) ratio is

for the extended ridge, compact ridge, plateau, hot core, and high

velocity plateau, respectively. Therefore, the corresponding

N(CS)/N(CO) ratio is

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() for the extended ridge,

the compact ridge, the plateau, and the hot core, respectively.

In all cases, this ratio is in good

agreement with the N(CS)/N(CO

for the extended ridge,

the compact ridge, the plateau, and the hot core, respectively.

In all cases, this ratio is in good

agreement with the N(CS)/N(CO

![]() ,

derived from

N(HCS+)/N(HCO+).

,

derived from

N(HCS+)/N(HCO+).

When we fitted the line emission of CS, we found that it was difficult to

distinguish the contribution of the high velocity plateau to the line profiles

from those of the other components.

Assuming N(CS)/N(CO

![]() ,

the column density of

CS in the high velocity plateau would be

,

the column density of

CS in the high velocity plateau would be ![]()

![]() (peak

(peak

![]() K).

K).

5.5 CCS

Collisional cross-sections of CCS-H2 were

extrapolated from those of OCS (Green & Chapman 1978) using the IOS

approximation for a ![]() molecule (see Corey 1984;

Corey & McCourt 1984; Fuente et al. 1990).

In this case, we changed the velocity parameters

for the hot core component with respect to the parameters given in

Table 2 to reproduce the line

profiles more accurately.

The new values are

molecule (see Corey 1984;

Corey & McCourt 1984; Fuente et al. 1990).

In this case, we changed the velocity parameters

for the hot core component with respect to the parameters given in

Table 2 to reproduce the line

profiles more accurately.

The new values are

![]() km s-1 and

km s-1 and

![]() km s-1.

km s-1.

The modeled lines are

shown in Fig. 12 (thin lines).

The values of the column densities are:

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() cm-2 for the hot core, the compact ridge, the extended ridge, and

the plateau, respectively. We note that Turner (1991) reported the

first tentative detection of CCS in this

source with a beam-averaged column density of

cm-2 for the hot core, the compact ridge, the extended ridge, and

the plateau, respectively. We note that Turner (1991) reported the

first tentative detection of CCS in this

source with a beam-averaged column density of

![]() cm-2.

cm-2.

5.6 C3S

For this molecule, we considered that only the hot core component

is responsible for the emission, hence we assume

LTE excitation. We chose the same physical conditions for this

component as in the CCS analysis.

Figure 13 shows the modeled line profiles for some

selected lines, for N(C3S

![]() cm-2. Taking into account the CCS

column density, we derive the ratio

CCS/C3S = 2.5 which is similar to the value of

cm-2. Taking into account the CCS

column density, we derive the ratio

CCS/C3S = 2.5 which is similar to the value of ![]() 3.5 found in the

dark cloud TMC-1 by Hirahara et al. (1992) and the value of

3.5 found in the

dark cloud TMC-1 by Hirahara et al. (1992) and the value of ![]() 3 found

in the envelope of the C-rich star IRC+10216 by Cernicharo et al. (1987a)

(note that we corrected this last value for the dipole moment of C3S adopted

in this study, 3.7

versus 2.6 in Cernicharo et al. 1987a).

3 found

in the envelope of the C-rich star IRC+10216 by Cernicharo et al. (1987a)

(note that we corrected this last value for the dipole moment of C3S adopted

in this study, 3.7

versus 2.6 in Cernicharo et al. 1987a).

5.7 Non-detected CS-bearing molecules

OC3S.- The molecule OC3S has not yet been detected in space.

The rotational constants used to derive the line frequencies

were taken from Winnewisser et al. (2000).

The dipole moment we used (![]() .63D) is quoted

in Matthews et al. (1987). Assuming the same

physical conditions as those derived for OCS, we obtain an

upper limit to its column density of

.63D) is quoted

in Matthews et al. (1987). Assuming the same

physical conditions as those derived for OCS, we obtain an

upper limit to its column density of

![]() cm-2.

This result provides an OCS/OC3S abundance ratio larger than 100.

cm-2.

This result provides an OCS/OC3S abundance ratio larger than 100.

H2CCS.- For this molecule, we derived its line frequencies with

the rotational constants given in Winnewisser et al. (1980); some distortion

constants were fixed to the value obtained from infrared data

by McNaughton (1996).

The dipole moment (![]() .02D) was taken from Georgiou et al. (1979).

We derive an upper limit to the column density of

thioketene of

.02D) was taken from Georgiou et al. (1979).

We derive an upper limit to the column density of

thioketene of

![]() cm-2, which infers a

H2CS/H2CCS abundance ratio near 20. This molecule has not

yet been detected in space.

cm-2, which infers a

H2CS/H2CCS abundance ratio near 20. This molecule has not

yet been detected in space.

HNCS.- Isothiocyanic acid is a pseudolinear molecule with a large A

rotational constant, similar to that of isocyanic acid, HNCO.

Only transitions up to Ka = 1 have been

observed in the interstellar medium (in SgrB2 by Frerking et al. 1979).

However, this molecule has not yet

been detected in Orion. Turner (1991) reported a tentative

detection of HNCS in Orion and listed five transitions as detected,

but three of them were not reliable. Turner derived an LTE column

density of

![]() cm-2 assuming

cm-2 assuming

![]() K

based on a single transition.

For frequency predictions, we used the rotational

constants presented by Niedenhoff (1995).

The a-dipole moment component (

K

based on a single transition.

For frequency predictions, we used the rotational

constants presented by Niedenhoff (1995).

The a-dipole moment component (

![]() .64D) was mentioned in

Szalanski et al. (1978).

We derive an upper limit to the column density of

.64D) was mentioned in

Szalanski et al. (1978).

We derive an upper limit to the column density of

![]() cm-2. Marcelino et al. (2009) calculated N(HNCO) towards Orion KL

from this survey, to be N(HNCO

cm-2. Marcelino et al. (2009) calculated N(HNCO) towards Orion KL

from this survey, to be N(HNCO

![]() cm-2; these values imply a HNCO/HNCS ratio >85.

cm-2; these values imply a HNCO/HNCS ratio >85.

HOCS+.- Spectroscopic constants are taken from Ohshima & Endo (1996).

The dipole moment (![]() .517D) was calculated by Wheeler et al. (2006).

We obtain an upper limit to the column density of this

cation of N(HOCS

.517D) was calculated by Wheeler et al. (2006).

We obtain an upper limit to the column density of this

cation of N(HOCS

![]() cm-2. This

result and the high column density of OCS may indicate

that this ion is efficiently destroyed by dissociative recombination

to produce OCS + H (Charnley 1997).

cm-2. This

result and the high column density of OCS may indicate

that this ion is efficiently destroyed by dissociative recombination

to produce OCS + H (Charnley 1997).

NCS.- Thiocyanogen has not yet been detected in space.

The rotational constants used to derive the line frequencies

were taken from CDMS Catalog. The dipole moment (![]() .45D)

is from an ab initio calculation by H. S. P. Müller (unpublished).

We derive here N(NCS

.45D)

is from an ab initio calculation by H. S. P. Müller (unpublished).

We derive here N(NCS

![]() cm-2.

cm-2.

6 Isotopic abundances