| Issue |

A&A

Volume 515, June 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A77 | |

| Number of page(s) | 26 | |

| Section | Interstellar and circumstellar matter | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200913150 | |

| Published online | 11 June 2010 | |

Grain growth across protoplanetary discs: 10  m silicate feature versus millimetre slope

m silicate feature versus millimetre slope![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

D. J. P. Lommen1 - E. F. van Dishoeck1,2 - C. M. Wright3 - S. T. Maddison4 - M. Min5,6 - D. J. Wilner7 - D. M. Salter1 - H. J. van Langevelde8,1 - T. L. Bourke7 - R. F. J. van der Burg1 - G. A. Blake9

1 - Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, PO Box 9513, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands

2 - Max-Planck-Institut für extraterrestrische Physik, Garching, Germany

3 - School of Physical, Environmental and Mathematical Sciences, UNSW@ADFA, Canberra ACT 2600, Australia

4 - Centre for Astrophysics and Supercomputing, Swinburne University of Technology, PO Box 218, Hawthorn, VIC 3122, Australia

5 - Astronomical Institute Utrecht, Princetonplein 5, 3584 CC Utrecht, The Netherlands

6 - Astronomical institute Anton Pannekoek, University of Amsterdam, Kruislaan 403, 1098 SJ Amsterdam, The Netherlands

7 - Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden Street, 02138 Cambridge, MA, USA

8 - Joint Institute for VLBI in Europe, PO Box 2, 7990 AA Dwingeloo, The Netherlands

9 - California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA

Received 19 August 2009 / Accepted 18 March 2010

Abstract

Context. Young stars are formed with dusty discs around

them. The dust grains in the disc are originally of the same size as

interstellar dust, i.e., of the order of 0.1 ![]() m.

Models predict that these grains will grow in size through coagulation.

Observations of the silicate features around 10 and 20

m.

Models predict that these grains will grow in size through coagulation.

Observations of the silicate features around 10 and 20 ![]() m

are consistent with growth from submicron to micron sizes in selected

sources whereas the slope of the spectral energy distribution (SED)

at mm and cm wavelengths traces growth up to mm sizes

and larger.

m

are consistent with growth from submicron to micron sizes in selected

sources whereas the slope of the spectral energy distribution (SED)

at mm and cm wavelengths traces growth up to mm sizes

and larger.

Aims. We here look for a correlation between these two grain growth indicators.

Methods. A large sample of T-Tauri and Herbig-Ae/Be stars,

spread over the star-forming regions in Chamaeleon, Lupus, Serpens,

Corona Australis, and the Gum nebula in Vela, was observed with the

Spitzer Space Telescope at 5-13 ![]() m,

and a subsample was observed with the SMA, ATCA, CARMA, and VLA at

mm wavelengths. We complement this subsample with data from the

literature to maximise the overlap between

m,

and a subsample was observed with the SMA, ATCA, CARMA, and VLA at

mm wavelengths. We complement this subsample with data from the

literature to maximise the overlap between ![]() m

and mm observations and search for correlations in the grain-growth

signatures. Synthetic spectra are produced to determine which processes

may produce the dust evolution observed in protoplanetary discs.

m

and mm observations and search for correlations in the grain-growth

signatures. Synthetic spectra are produced to determine which processes

may produce the dust evolution observed in protoplanetary discs.

Results. Dust disc masses in the range <1 to 7 ![]()

![]() are obtained. The majority of the sources have a mm spectral slope

consistent with grain growth. There is a tentative correlation between

the strength and the shape of the 10-

are obtained. The majority of the sources have a mm spectral slope

consistent with grain growth. There is a tentative correlation between

the strength and the shape of the 10-![]() m

silicate feature and the slope of the SED between 1

and 3 mm. The observed sources seem to be grouped per

star-forming region in the 10-

m

silicate feature and the slope of the SED between 1

and 3 mm. The observed sources seem to be grouped per

star-forming region in the 10-![]() m-feature vs.

mm-slope diagram. The modelling results show that, if only the

maximum grain size is increased, first the 10-

m-feature vs.

mm-slope diagram. The modelling results show that, if only the

maximum grain size is increased, first the 10-![]() m

feature becomes flatter and subsequently the mm slope becomes

shallower. To explain the sources with the shallowest

mm slopes, a grain size distribution shallower than that of

the interstellar medium is required. Furthermore, the strongest 10-

m

feature becomes flatter and subsequently the mm slope becomes

shallower. To explain the sources with the shallowest

mm slopes, a grain size distribution shallower than that of

the interstellar medium is required. Furthermore, the strongest 10-![]() m features can only be explained with bright (

m features can only be explained with bright (

![]() ), hot (

), hot (

![]() K) central stars. Settling of larger grains towards the disc midplane results in a stronger 10-

K) central stars. Settling of larger grains towards the disc midplane results in a stronger 10-![]() m feature, but has a very limited effect on the mm slope.

m feature, but has a very limited effect on the mm slope.

Conclusions. A tentative correlation between the strength of the 10-![]() m

feature and the mm slope is found, which would imply that the

inner and outer disc evolve simultaneously. Dust with a mass dominated

by large,

m

feature and the mm slope is found, which would imply that the

inner and outer disc evolve simultaneously. Dust with a mass dominated

by large, ![]() mm-sized,

grains is required to explain the shallowest mm slopes. Other

processes besides grain growth, such as the clearing of an inner

disc by binary interaction, may also be responsible for the

removal of small grains. Observations with future telescopes with

larger bandwidths or collecting areas are required to provide the

necessary statistics to study these processes of disc and dust

evolution.

mm-sized,

grains is required to explain the shallowest mm slopes. Other

processes besides grain growth, such as the clearing of an inner

disc by binary interaction, may also be responsible for the

removal of small grains. Observations with future telescopes with

larger bandwidths or collecting areas are required to provide the

necessary statistics to study these processes of disc and dust

evolution.

Key words: accretion, accretion disks - circumstellar matter - stars: pre-main sequence - stars: formation

1 Introduction

A long-standing problem in planet formation is how tiny interstellar dust particles of less than a micron in size coagulate and grow to eventually form planets, thousands of kilometres in size. It is in the very nature of this field that it has to be studied at various levels, since different physical processes dominate during the various phases. The first steps, which lead to dust grains of about a decimetre in size, are studied both in the laboratory and with computer simulations (see Dominik et al. 2007; Blum & Wurm 2008 for detailed reviews). Local concentrations of boulders and subsequent gravitational collapse may then lead to the formation of planetesimals several hundreds of kilometres in size (e.g., Johansen et al. 2007). This paper focuses on the observational signatures of (sub)micron-sized grains up to centimetre-sized pebbles.

The InfraRed Spectrograph (IRS) on-board the Spitzer Space Telescope has provided a wealth of mid-infrared (5-40 ![]() m) spectra from discs around pre-main-sequence stars (e.g. Kessler-Silacci et al. 2006; Furlan et al. 2006). The spectra of these objects are often dominated by silicate emission features at 10 and 20

m) spectra from discs around pre-main-sequence stars (e.g. Kessler-Silacci et al. 2006; Furlan et al. 2006). The spectra of these objects are often dominated by silicate emission features at 10 and 20 ![]() m.

In young stellar objects, these features are formed in the upper

atmosphere of the hot inner disc. The varying strength and the shape of

these features can be naturally explained by different grain sizes in

the upper layers of the inner disc, with strong, pointed features being

representative of

m.

In young stellar objects, these features are formed in the upper

atmosphere of the hot inner disc. The varying strength and the shape of

these features can be naturally explained by different grain sizes in

the upper layers of the inner disc, with strong, pointed features being

representative of ![]() 0.1

0.1 ![]() m-sized grains and flatter features coming from dust grains of several

m-sized grains and flatter features coming from dust grains of several ![]() m in size (Kessler-Silacci et al. 2006). These results confirm earlier results from the Infrared Space Observatory (Meeus et al. 2001; Bouwman et al. 2001) and from ground-based observations (e.g., Przygodda et al. 2003). It has been suggested that crystallisation has a similar effect on the 10-

m in size (Kessler-Silacci et al. 2006). These results confirm earlier results from the Infrared Space Observatory (Meeus et al. 2001; Bouwman et al. 2001) and from ground-based observations (e.g., Przygodda et al. 2003). It has been suggested that crystallisation has a similar effect on the 10-![]() m feature as grain growth

(e.g., Meeus et al. 2003; Honda et al. 2003). However, this effect is minimal and the dominating factor

for the strength and shape of the 10-

m feature as grain growth

(e.g., Meeus et al. 2003; Honda et al. 2003). However, this effect is minimal and the dominating factor

for the strength and shape of the 10-![]() m feature is the characteristic grain size (Olofsson et al. 2009).

m feature is the characteristic grain size (Olofsson et al. 2009).

Because the 10-![]() m

feature only probes the surface layers of the inner disc,

a stronger, more peaked feature could also be due to the settling

of larger, micron-sized grains towards the mid-plane. As the

larger grains settle and the small ones remain suspended in the upper

layers, the surface becomes dominated by small grains, creating a

strong silicate band. Dullemond & Dominik (2008)

investigated this idea through theoretical models. They find that

settling can in principle explain the different shapes of the 10-

m

feature only probes the surface layers of the inner disc,

a stronger, more peaked feature could also be due to the settling

of larger, micron-sized grains towards the mid-plane. As the

larger grains settle and the small ones remain suspended in the upper

layers, the surface becomes dominated by small grains, creating a

strong silicate band. Dullemond & Dominik (2008)

investigated this idea through theoretical models. They find that

settling can in principle explain the different shapes of the 10-![]() m

feature, but only in quite specific cases, so that overall grain

growth is still the most likely explanation for the flattening of these

features. Recent interferometric observations of the 10-

m

feature, but only in quite specific cases, so that overall grain

growth is still the most likely explanation for the flattening of these

features. Recent interferometric observations of the 10-![]() m spectral region in discs around

m spectral region in discs around ![]() 1 and 2-3-

1 and 2-3-![]() objects show that the grains closer to the central star are both larger

and more crystalline than those further out in the disc (see, e.g., the

recent review by van Boekel 2008). Hence, the evolution of the 10-

objects show that the grains closer to the central star are both larger

and more crystalline than those further out in the disc (see, e.g., the

recent review by van Boekel 2008). Hence, the evolution of the 10-![]() m

feature may be caused by a combination of grain growth and

crystallisation and appears to progress from the inner disc outwards.

On the other hand, analysis of the longer wavelenth mid-infrared

crystalline features indicates significant growth and crystallisation

in the outer disc as well (Olofsson et al. 2009).

m

feature may be caused by a combination of grain growth and

crystallisation and appears to progress from the inner disc outwards.

On the other hand, analysis of the longer wavelenth mid-infrared

crystalline features indicates significant growth and crystallisation

in the outer disc as well (Olofsson et al. 2009).

Whereas the mid-infrared region potentially provides information on the

growth of grains from interstellar, submicron sizes to sizes of several

microns, the growth to larger sizes can only be probed by

submillimetre (submm), millimetre (mm), and occasionally

centimetre (cm) observations. Ground-breaking work was done by Beckwith et al. (1990) and Beckwith & Sargent (1991),

both analytically studying the emission of dust grains and obtaining

the first submm slopes by observing a large sample of young stellar

objects at mm wavelengths. More recently, Andrews & Williams (2005)

performed a sensitive single-dish submm continuum survey of

153 young stellar objects in the Taurus-Auriga star-formation

region, including a large amount of archival and literature data. They

found that the submm slope between 350 ![]() m and 1.3 mm could be well described by

m and 1.3 mm could be well described by

![]()

![]() 0.5, where

0.5, where

![]() ,

while the value for the interstellar medium is

,

while the value for the interstellar medium is

![]() (cf. Draine 2006). Andrews & Williams (2005)

interpreted this shallow slope as a combined effect of a contribution

from optically thick regions in the disc and grain growth.

It should be noted, however, that the sources in this study

were spatially unresolved, and the (sub)mm emission may have a

significant contribution from surrounding (envelope) material.

More recently, interferometric studies of several dozen T-Tauri

stars gave values of

(cf. Draine 2006). Andrews & Williams (2005)

interpreted this shallow slope as a combined effect of a contribution

from optically thick regions in the disc and grain growth.

It should be noted, however, that the sources in this study

were spatially unresolved, and the (sub)mm emission may have a

significant contribution from surrounding (envelope) material.

More recently, interferometric studies of several dozen T-Tauri

stars gave values of

![]() (Lommen et al. 2007; Andrews & Williams 2007; Rodmann et al. 2006). Similar results were found for a number of more massive Herbig-Ae/Be stars (e.g., Natta et al. 2004). From this mm slope one can estimate the opacity index

(Lommen et al. 2007; Andrews & Williams 2007; Rodmann et al. 2006). Similar results were found for a number of more massive Herbig-Ae/Be stars (e.g., Natta et al. 2004). From this mm slope one can estimate the opacity index

![]()

![]()

![]() ,

where

,

where ![]() is found to be

is found to be ![]() 0.20 (Lommen et al. 2007; Rodmann et al. 2006), and values of

0.20 (Lommen et al. 2007; Rodmann et al. 2006), and values of

![]() for

for

![]() mm

were found. Such a slope can be naturally explained by a

significant fraction of grains at least several mm in size present

in the discs (Draine 2006).

mm

were found. Such a slope can be naturally explained by a

significant fraction of grains at least several mm in size present

in the discs (Draine 2006).

A subsample of the sources observed by Lommen et al. (2007) overlapped with the Spitzer Infrared Spectrograph (IRS) observations published by Kessler-Silacci et al. (2006) and Lommen et al. (2007)

found a tentative correlation between the mm slope of the spectral

energy distribution (SED) and the strength and shape of the 10-![]() m silicate feature for these sources. Note that the 10-

m silicate feature for these sources. Note that the 10-![]() m

feature primarily probes the hot surface layers of the inner disc,

whereas the (sub)mm observations provide information of the cold

mid-plane of the outer disc. A correlation between the two is

therefore not obvious at all and a confirmation of this correlation

would give very valuable information on the processes of dust growth in

protoplanetary discs, as it would imply that grain growth from

submicron to mm sizes is both fast and occurs simultaneously throughout

the

whole disc.

m

feature primarily probes the hot surface layers of the inner disc,

whereas the (sub)mm observations provide information of the cold

mid-plane of the outer disc. A correlation between the two is

therefore not obvious at all and a confirmation of this correlation

would give very valuable information on the processes of dust growth in

protoplanetary discs, as it would imply that grain growth from

submicron to mm sizes is both fast and occurs simultaneously throughout

the

whole disc.

Acke et al. (2004) calculated the

(sub)mm spectral indices of 26 Herbig-Ae/Be stars, for which

the infrared SED could also be determined. They found a correlation

between the strength of the ratio

of the near- to mid-infrared excess and the slope of the (sub)mm energy

distribution for these sources, which they attributed to a correlation

between the disc geometry (flared versus self-shadowed) and the size of

the grains in the disc. However, the authors did not find a

correlation between the strength and the shape of the 10-![]() m silicate feature and the (sub)mm spectral index (see also Acke & van den Ancker 2004).

m silicate feature and the (sub)mm spectral index (see also Acke & van den Ancker 2004).

The aim of this paper is to investigate the tentative correlation between the strength and shape of the 10-![]() m silicate feature and the spectral slope in the (sub)mm regime, found by Lommen et al. (2007),

for a larger sample. A subsample of sources studied with

the Spitzer IRS were observed with mm and cm interferometers

(Sect. 2). Interferometers were used to ascertain that the

emission is dominated by disc emission, since extended emission from

surrounding material will be filtered out. Also, spatially resolving

the disc ensures that the emission is not optically thick

(e.g., Natta et al. 2004). The

results of the observations, including dust disc masses and

mm slopes, are shown in Sect. 3, and in Sect. 4 we

present model results for discs. The observations and models are

compared and discussed in Sect. 5; conclusions are formulated

in Sect. 6.

m silicate feature and the spectral slope in the (sub)mm regime, found by Lommen et al. (2007),

for a larger sample. A subsample of sources studied with

the Spitzer IRS were observed with mm and cm interferometers

(Sect. 2). Interferometers were used to ascertain that the

emission is dominated by disc emission, since extended emission from

surrounding material will be filtered out. Also, spatially resolving

the disc ensures that the emission is not optically thick

(e.g., Natta et al. 2004). The

results of the observations, including dust disc masses and

mm slopes, are shown in Sect. 3, and in Sect. 4 we

present model results for discs. The observations and models are

compared and discussed in Sect. 5; conclusions are formulated

in Sect. 6.

2 Observations

For this study, we compared Spitzer IRS observations covering the 10-![]() m silicate feature with mm observations from the Very Large Array (VLA, operated by NRAO

m silicate feature with mm observations from the Very Large Array (VLA, operated by NRAO![]() ), the Combined Array for Research in Millimeter-wave Astronomy (CARMA

), the Combined Array for Research in Millimeter-wave Astronomy (CARMA![]() ), the Submillimeter Array (SMA

), the Submillimeter Array (SMA![]() ), and the Australia Telescope Compact Array (ATCA

), and the Australia Telescope Compact Array (ATCA![]() ). The sources for which new observations are obtained for this work are listed in Table 2. A full log of the newly obtained mm and cm observations is listed in Appendix A. A full log of the newly obtained mm and cm results is listed in Appendix B.

). The sources for which new observations are obtained for this work are listed in Table 2. A full log of the newly obtained mm and cm observations is listed in Appendix A. A full log of the newly obtained mm and cm results is listed in Appendix B.

2.1 Source selection and Spitzer data

To look for possible environmental effects, sources in a total of

five star-forming regions were observed, spread over the constellations

Lupus, Chamaeleon, Corona Australis, Serpens, and the Gum nebula in

Vela at distances of about 150-200, 160, 130, 260, and 400 pc,

respectively. Furthermore, data from the literature for the

Taurus-Auriga star-forming region at about 140 pc were included to

improve the statistics further, see Table 1. The sources were pre-selected to have a large spread in the strengths and shapes of the 10-![]() m features from Spitzer IRS data, mainly the ``From Molecular Cores to Planet-forming Discs'' programme (c2d, Evans et al. 2003,

Program IDs 139 and 172-179), the ``The evolution of dust

mineralogy in southern star forming clouds'' programme

(C.M. Wright PI, Project ID 20611), and ``A complete

IRS survey of the evolution of circumstellar disks within

3 Myr: New clusters of sequential star formation in Serpens''

(K.M. Pontoppidan PI, Project ID 30223). The spectra from the

c2d project were previously published in Kessler-Silacci et al. (2006) and Olofsson et al. (2009).

Program P20611 includes Spitzer IRS observations from embedded

YSOs, T-Tauri stars, and Herbig/Vela-type stars. The results for the

T-Tauri stars are presented in this work.

m features from Spitzer IRS data, mainly the ``From Molecular Cores to Planet-forming Discs'' programme (c2d, Evans et al. 2003,

Program IDs 139 and 172-179), the ``The evolution of dust

mineralogy in southern star forming clouds'' programme

(C.M. Wright PI, Project ID 20611), and ``A complete

IRS survey of the evolution of circumstellar disks within

3 Myr: New clusters of sequential star formation in Serpens''

(K.M. Pontoppidan PI, Project ID 30223). The spectra from the

c2d project were previously published in Kessler-Silacci et al. (2006) and Olofsson et al. (2009).

Program P20611 includes Spitzer IRS observations from embedded

YSOs, T-Tauri stars, and Herbig/Vela-type stars. The results for the

T-Tauri stars are presented in this work.

The data from Project ID 20611 are presented here for the first time.

The data from the other programmes are re-reduced for this work using

the updated c2d IRS reduction pipeline (Lahuis et al. 2006)

for uniformity of the comparisons. Spectra were obtained both

integrated over the full aperture of the instrument as well as

convolved with the point spread function

(PSF) at each wavelength. The spectra obtained using the Full-Aperture

extraction method were used in here, unless the final spectrum quality

of the PSF extraction method was considerably better. Furthermore,

only data from the short-low module (SL, 5.2-14.5 ![]() m) were included, unless data from the short-high module (SH, 9.9-19.6

m) were included, unless data from the short-high module (SH, 9.9-19.6 ![]() m) were present and of significantly higher quality.

m) were present and of significantly higher quality.

Table 1: Distances to and ages of star-forming clouds.

In binary systems, it is possible that circumstellar discs get

truncated due to binary interaction, affecting grain growth in the

discs. To check for such effects, a number of binaries were

included in the sample. Furthermore, the sources were selected to

include so-called ``cold'' or ``transitional'' discs (e.g. Brown et al. 2007).

The cold discs show a lower flux in the mid-infrared, which can be

naturally explained by a lack of small warm dust close to the star.

Several of the cold discs were recently found to be circumbinary discs,

with a large hole or gap in the centre, e.g., CS Cha (Espaillat et al. 2007) and HH 30 (Guilloteau et al. 2008).

However, some cold discs are supposedly single stars, requiring a

different mechanism to clear the inner discs of small, hot grains

(e.g., Pontoppidan et al. 2008).

One such mechanism could be grain growth into larger particles. Another

possibility would be that a planet has cleared the inner disc from most

of the large grains, leaving behind a protoplanetary disc dominated by

small, micron-sized grains.

A number of cold discs of Brown et al. (2007) and Merín et al. (2008)

were included in the sample with the aim to explore this possibility.

A full list of the sources (35 single sources and five

binaries) is given in Table 2. As will be shown in the next section, 33 of these turn out to have a detected 10-![]() m feature and 13 yield a mm slope, more than doubling the sample of sources studied in Lommen et al. (2007).

m feature and 13 yield a mm slope, more than doubling the sample of sources studied in Lommen et al. (2007).

Table 2: List of sources observed with the SMA, ATCA, CARMA, and VLA.

2.2 SMA observations

15 single sources and one binary were observed with the SMA for the

project 2007B-S033. The observations were carried out on

14 March and 19 April 2008. The data of 14 March

were unusable due to phase instabilities and the track was reobserved

on 7 May 2009. On 19 April 2008,

the phases were stable and the zenith optical depth at

225 GHz was around

![]() all through the night. The synthesised beam was about 4.8

all through the night. The synthesised beam was about 4.8 ![]() 2.8 arcsec (natural weighting). On 7 May 2009, the phases were stable and

2.8 arcsec (natural weighting). On 7 May 2009, the phases were stable and

![]() was low with values ranging from 0.05 to 0.08. The synthesised beam was about 4.1

was low with values ranging from 0.05 to 0.08. The synthesised beam was about 4.1 ![]() 2.2 arcsec.

The two sidebands were combined into one continuum channel to improve

the signal-to-noise ratio, resulting in an effective wavelength

of 1.33 mm.

2.2 arcsec.

The two sidebands were combined into one continuum channel to improve

the signal-to-noise ratio, resulting in an effective wavelength

of 1.33 mm.

The sources VV CrA (binary), S CrA (binary), and

DG CrA (single source) were observed as part of the SMA ``filler''

project 2008A-S111 on 1 October 2008. Only six of the eight

antennas were available for this track. However,

![]() and the phases were stable, resulting in extremely good data. The synthesised beam of the resulting maps was about 5.0

and the phases were stable, resulting in extremely good data. The synthesised beam of the resulting maps was about 5.0 ![]() 2.1 arcsec

(natural weighting). The correlator was tuned to 218 and

228 GHz. Combination of the two sidebands resulted in an effective

wavelength of 1.35 mm.

2.1 arcsec

(natural weighting). The correlator was tuned to 218 and

228 GHz. Combination of the two sidebands resulted in an effective

wavelength of 1.35 mm.

The absolute flux calibration of the first track (19 April 2008) was carried out on Mars and the resulting fluxes are estimated to be accurate to about 20%. The second and third tracks (1 October 2008 and 7 May 2009) were flux calibrated on Callisto. The uncertainty in the absolute fluxes for those tracks is estimated to be 15% or better.

Hence, a total of 16 single sources and three binaries located in the Lupus star-forming region were observed with the SMA for this project. The sources are listed in Table 2, a detailed log of the observations is given in Table A.1, and detailed results are presented in Table B.1 and Fig. B.1.

2.3 ATCA observations

The data for the ATCA project C1794 were taken over the period July to August 2008 when the array was in the H214 configuration. A total of 15 sources were observed: 14 sources (including the binary IK Lup+Sz 66) were measured at 3 mm and 11 sources at 7 mm. The sources are listed in Table 2, a detailed log of the observations is given in Table A.2, and detailed results are presented in Table B.2 and Figs. B.3 and B.4. The weather changed considerably over the course of the observations. A short indication of the circumstances for each day is included in Appendix A. Physical baselines ranged from 82 to 247 m, resulting in synthesised beam sizes of about 2 arcsec at 3 mm and about 4 arcsec at 7 mm. Combining the two sidebands in the 3 mm band resulted in an effective wavelength of 3.17 mm, those taken in the 7 mm band in an effective wavelength of 6.82 mm.

The absolute flux calibration for the first track was carried out on Mars, whereas the flux calibration for the other tracks was carried out on Uranus. Only the shortest baselines were taken into account when determining the absolute gain offset so as to minimise the possible effect of the planets' being resolved. Furthermore, the planets were observed at elevations close to those at which the gain calibrators were observed. Overall, the uncertainty in the absolute fluxes is estimated to range from 15 to about 25%.

2.4 CARMA observations

For this work, eleven single sources and one binary located in

Serpens were observed with CARMA at 1 and 3 mm in the period

April to June 2008 for project c0165. The sources are listed

in Table 2, a detailed log of the observations is given in Table A.3, and detailed results are presented in Table ![]() and Figs. B.5 and B.6. Weather conditions varied over the course of the observations, with a typical water path length of 3-6 mm.

and Figs. B.5 and B.6. Weather conditions varied over the course of the observations, with a typical water path length of 3-6 mm.

The gain calibrator originally selected for the observations at

1 mm, QSO J1743-038, turned out to be too weak to perform a

decent gain calibration, rendering most of the C-configuration

observations unusable. For the second part of the observations the

telescope was in the D configuration (baselines 11-148 m),

yielding a synthesised beam of about 3 ![]() 2 arcsec at 1 mm and about 6

2 arcsec at 1 mm and about 6 ![]() 4 arcsec

at 3 mm. The effective wavelength of the 1 mm-band

observations was 1.33 mm, that of the 3 mm-band observations

3.15 mm.

4 arcsec

at 3 mm. The effective wavelength of the 1 mm-band

observations was 1.33 mm, that of the 3 mm-band observations

3.15 mm.

The absolute fluxes were calibrated on the quasars QSO J2253+161 (3c454.3), QSO J1229+020 (3c273), and QSO J1256-057 (3c279), whose fluxes were bootstrapped from planet observations on short baselines on dates as close as possible to the observation dates. The fluxes of these quasars vary considerably over the course of weeks to months at 1 and 3 mm, but day-to-day variations are usually less than 10%. Taking this into account, the effective uncertainty in the absolute fluxes for our target sources is estimated to be less than 30%.

2.5 VLA observations

Of the sources in the Serpens star-forming region observed with CARMA, seven single sources and the binary EC 90 were observed with the VLA at 7 mm and at 1.3, 3.6, and 6.3 cm under programme AL720. The sources are listed in Table 2, a detailed log of the observations is given in Table A.4, and detailed results are presented in Table B.4. The observations were carried out from 10-15 March 2008, when the array was in the C configuration, with baselines of up to 3.6 km and a synthesised beam of about 0.5 arcsec at 7 mm. All observations were performed in the default continuum mode in which, at each frequency, the full 100-MHz bandwidth was used in two adjacent 50 MHz bands. Although weather conditions were good in general, a few hours of observing time were lost at the end of the last two tracks due to high winds.

The VLA data were flux calibrated on the quasar QSO J1331+305 (3c286). The flux as a function of wavelength is modelled by the AIPS reduction package. The resulting uncertainty in the absolute flux calibration is estimated to be about 20% at 7 mm and 1.3 cm and better than 10% at 3.6 and 6.3 cm.

3 Results

3.1 Mm and cm source fluxes and dust disc masses

A full log of the results is listed in Appendix B. The results of the interferometric observations at 1, 3, and 7 mm are listed in Table 3.

Table 3: Fluxes from point-source fits in the (u, v) plane obtained from interferometric data and single-dish 1.20-1.27 mm SEST fluxes.

A total of 16 single sources and three binaries in Lupus are observed with the SMA. Nine of the single sources are detected and one of those, Sz 73, turned out to harbour two sources, with a projected separation of about 4 arcsec. It is possible that the detection of Sz 73 with SEST (Nürnberger et al. 1997) included both sources. The binaries VV CrA and S CrA are detected and unresolved. Of the binary system IK Lup (Sz 65) and Sz 66, only IK Lup is detected, although a second peak is detected at 2 arcsec from the 2MASS position of Sz 66. Sz 66 was previously detected with a S/N of almost four using the SEST bolometer. All sources in Lupus observed with the ATCA at 3.2 mm are detected; the binary system IK Lup and Sz 66 remained unresolved. Only one Lupus source, IM Lup, is detected at 6.8 mm. MY Lup would have been detected at 6.8 mm with a signal-to-noise ratio of about ten if it had a similar mm slope as IM Lup.

None of the three sources in the Gum nebula observed with the ATCA

at 3.2 and at 6.8 mm are detected at either wavelength down

to 3![]() upper limits of

upper limits of ![]() 3 mJy at 3.2 mm and of

3 mJy at 3.2 mm and of ![]() 0.5 mJy

at 6.8 mm. This can be attributed to the large distance between us

and this star-forming region. If the sources in the

Gum nebula had similar luminosities as those in the Lupus clouds,

they would have had a flux of

0.5 mJy

at 6.8 mm. This can be attributed to the large distance between us

and this star-forming region. If the sources in the

Gum nebula had similar luminosities as those in the Lupus clouds,

they would have had a flux of ![]() 0.7 mJy

at 3.2 mm, which is below the noise level. Note that,

although the Vela molecular ridge has been observed at

mm wavelengths (Massi et al. 2007,1999), no published mm continuum data of the Gum nebula exist in the literature.

0.7 mJy

at 3.2 mm, which is below the noise level. Note that,

although the Vela molecular ridge has been observed at

mm wavelengths (Massi et al. 2007,1999), no published mm continuum data of the Gum nebula exist in the literature.

The source SZ Cha is detected at 2.3 mJy at 3.2 mm. Sz 32 is not detected down to a 3![]() upper

limit of 2.9 mJy at 3.2 mm. It is, however,

detected with a flux of 0.77 mJy at 6.8 mm.

upper

limit of 2.9 mJy at 3.2 mm. It is, however,

detected with a flux of 0.77 mJy at 6.8 mm.

VV CrA and S CrA are clearly detected at 1.3 mm

with the SMA, with fluxes of 376 and 303 mJy. DG CrA,

however, is not detected, down to a 3![]() upper

limit of only 6.6 mJy. VV CrA and S CrA are also

easily detected with the ATCA at 3 and 7 mm.

upper

limit of only 6.6 mJy. VV CrA and S CrA are also

easily detected with the ATCA at 3 and 7 mm.

Of the sources in the Serpens star-forming region that were observed with the CARMA, only three are detected: the single sources SSTc2d J182900.88+002931.5 and GSC 00446-00153 and the binary system EC 90, which remained unresolved. This can in part be explained by the distance to the star-forming region in Serpens, which is larger than those in Chamaeleon, Lupus, and Corona Australis. Furthermore, some of the sources, of which six are new Spitzer sources, may have an intrinsically lower luminosity. None of the sources are detected at 6.8 mm using the VLA.

Table 4:

Spectral slopes at mm wavelengths, dust disc masses, and properties of the 10-![]() m silicate feature.

m silicate feature.

Four cold discs are observed at 1.3 and 3.2 mm for this work. Only one of those, Sz 111, is detected. Unfortunately, Sz 111 was not observed with the Spitzer IRS.

All four binaries that are observed at 1.3 and 3.2 mm are detected

at both wavelengths. However, in the case of the binary consisting

of the stars IK Lup and Sz 66, only the former is detected at

1.3 mm. EC 90 and S CrA remain unresolved. The binary

IK Lup+Sz 66 is resolved with the ATCA at 3.2 mm.

VV CrA is resolved with a binary separation of 2.0 arcsec

with the ATCA at 3.2 mm if the source is imaged using uniform

weighting (optimised for resolution). However, this binary remains

unresolved with the SMA at 1.3 mm (beam size 4.7 ![]() 1.9 arcsec) and with the ATCA at 6.8 mm (beam size 5.3

1.9 arcsec) and with the ATCA at 6.8 mm (beam size 5.3 ![]() 3.0 arcsec).

3.0 arcsec).

The detection rate of the sources observed in this study is rather low. This can in part be understood by the distance to the star-forming regions, with the Serpens star-forming region being almost twice as far away as the Taurus-Auriga star-forming region and the Gum nebula in Vela almost three times as far away. This reduces the observed flux for similar sources by a factor of about four to nine. The low detection rate for Lupus is largely a selection effect: most of the brightest sources had been observed before (Lommen et al. 2007). These previously detected sources were not reobserved for this work, but their published values will be included in the analysis below.

Dust disc masses are obtained from the fluxes at 3.2 mm under the

rather crude assumptions of an isothermal disc and a fixed opacity.

Assuming also optically thin mm emission, the dust disc mass is given

by

![]() (

(

![]() ), where D is the distance to the source,

), where D is the distance to the source,

![]() the dust opacity (taken to be 0.9 cm2 g-1, cf. Beckwith et al. 1990), and

the dust opacity (taken to be 0.9 cm2 g-1, cf. Beckwith et al. 1990), and ![]() (

(

![]() )

the brightness at the frequency

)

the brightness at the frequency ![]() GHz for a dust temperature

GHz for a dust temperature

![]() ,

as given by the Planck function. We assume a dust temperature

,

as given by the Planck function. We assume a dust temperature

![]() K and find dust disc masses ranging from

K and find dust disc masses ranging from ![]() 0.4 to

0.4 to ![]()

![]()

![]() .

The dust disc masses are presented in Table 4.

.

The dust disc masses are presented in Table 4.

3.2 Millimetre slopes

The fluxes at 1, 3, and 7 mm can be combined to obtain the spectral index ![]() ,

where

,

where

![]() .

We are interested in the emission coming from the dusty disc. However,

at 7 mm, other emission mechanisms may contribute

significantly to the flux. Sources may include an ionised wind or

chromospheric magnetic activity. Rodmann et al. (2006)

compare their fluxes at 7 mm to those at 3 and 6 cm and

claim that about 20% of the emission at 7 mm is due to

free-free emission. On the other hand, Lommen et al. (2009)

find that the emission at 7 mm can be entirely attributed to dust

emission for a small sample of three sources. It is possible that

the emission due to, e.g., an ionised wind,

is independent of the disc mass and thus the relative contribution

from such a wind will be larger for young stellar objects that are

weaker at mm wavelengths. This could explain the findings of Lommen et al. (2009),

who monitored some of the strongest pre-main-sequence mm emitters

in the southern sky. However, a larger and more sensitive survey

at mm to cm wavelengths is required before more quantitative

statements on this subject can be made. Since we do not have fluxes at

all three wavelengths for most sources, separate indices will be

obtained between 1 and 3 mm and between 3 and 7 mm.

The results are given in Table 4.

.

We are interested in the emission coming from the dusty disc. However,

at 7 mm, other emission mechanisms may contribute

significantly to the flux. Sources may include an ionised wind or

chromospheric magnetic activity. Rodmann et al. (2006)

compare their fluxes at 7 mm to those at 3 and 6 cm and

claim that about 20% of the emission at 7 mm is due to

free-free emission. On the other hand, Lommen et al. (2009)

find that the emission at 7 mm can be entirely attributed to dust

emission for a small sample of three sources. It is possible that

the emission due to, e.g., an ionised wind,

is independent of the disc mass and thus the relative contribution

from such a wind will be larger for young stellar objects that are

weaker at mm wavelengths. This could explain the findings of Lommen et al. (2009),

who monitored some of the strongest pre-main-sequence mm emitters

in the southern sky. However, a larger and more sensitive survey

at mm to cm wavelengths is required before more quantitative

statements on this subject can be made. Since we do not have fluxes at

all three wavelengths for most sources, separate indices will be

obtained between 1 and 3 mm and between 3 and 7 mm.

The results are given in Table 4.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=16.5cm,clip]{13150fi1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13150-09/Timg76.png)

|

Figure 1: Spitzer IRS spectra from the T-Tauri stars observed for Spitzer project P20611 (C.M. Wright PI). Spectra with a maximum flux below 0.1 Jy were binned four times to improve the signal-to-noise ratio. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The slopes between 1 and 3 mm lie between 2.38 ![]() 0.36 and 3.83

0.36 and 3.83 ![]() 0.46. The opacity index

0.46. The opacity index ![]() can be calculated from the mm slope

can be calculated from the mm slope ![]() through

through

![]() ,

where

,

where ![]() is the ratio of optically thick to optically

thin emission (Beckwith et al. 1990; Rodmann et al. 2006). Rodmann et al. (2006) and Lommen et al. (2007) found values of

is the ratio of optically thick to optically

thin emission (Beckwith et al. 1990; Rodmann et al. 2006). Rodmann et al. (2006) and Lommen et al. (2007) found values of

![]() for the sources in their samples. Adopting this value, opacity indices

for the sources in their samples. Adopting this value, opacity indices ![]() of about 0.5 to 2.2 are found here. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov

test gives a probability of 50% that the values from this sample

and that of Lommen et al. (2007) are drawn from

the same distribution. This rather low value is due to the steep slopes for the sources RY Lup (3.83

of about 0.5 to 2.2 are found here. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov

test gives a probability of 50% that the values from this sample

and that of Lommen et al. (2007) are drawn from

the same distribution. This rather low value is due to the steep slopes for the sources RY Lup (3.83 ![]() 0.46) and SZ Cha (3.78

0.46) and SZ Cha (3.78 ![]() 0.43). Note that the corresponding values for

0.43). Note that the corresponding values for ![]() are

are ![]() ,

whereas the value for the interstellar medium is

,

whereas the value for the interstellar medium is

![]() (e.g., Draine & Lee 1984).

(e.g., Draine & Lee 1984).

A mm slope between 3 and 7 mm could only be determined for three

sources, whereas lower limits are found for four more sources and a

strict upper limit of

![]() for Sz 32. Interestingly, a lower limit of

for Sz 32. Interestingly, a lower limit of

![]() is found for Sz 32 between 1 and 3 mm. Other

emission mechanisms (due to, e.g., a wind or chromospheric

activity) may contribute at 7 mm. Although it is found that

for most sources this contribution is only of the order of 20% (Rodmann et al. 2006),

it is possible that it is higher for Sz 32, causing the very

shallow slope between 3 and 7 mm. The slopes of

is found for Sz 32 between 1 and 3 mm. Other

emission mechanisms (due to, e.g., a wind or chromospheric

activity) may contribute at 7 mm. Although it is found that

for most sources this contribution is only of the order of 20% (Rodmann et al. 2006),

it is possible that it is higher for Sz 32, causing the very

shallow slope between 3 and 7 mm. The slopes of

![]()

![]() 0.5 and 2.5

0.5 and 2.5 ![]() 0.4 for VV CrA and S CrA are consistent with those of

0.4 for VV CrA and S CrA are consistent with those of

![]()

![]() 0.5 and 2.9

0.5 and 2.9 ![]() 0.7

and also the slopes between 3 and 7 mm found for

RY Lup (>2.0), Sz 111 (>2.9), RX J1615.3-3255

(>3.4), and MY Lup (>3.5) are consistent with the values

between 1 and 3 mm. The slope between 3

and 7 mm for IM Lup, however, is very shallow

compared to that between 1 and 3 mm:

0.7

and also the slopes between 3 and 7 mm found for

RY Lup (>2.0), Sz 111 (>2.9), RX J1615.3-3255

(>3.4), and MY Lup (>3.5) are consistent with the values

between 1 and 3 mm. The slope between 3

and 7 mm for IM Lup, however, is very shallow

compared to that between 1 and 3 mm:

![]()

![]() 0.3 vs.

0.3 vs.

![]()

![]() 0.4. Pinte et al. (2008) found a mm spectral index of 2.80

0.4. Pinte et al. (2008) found a mm spectral index of 2.80 ![]() 0.25

and their modelling results suggested that IM Lup has grains of at

least mm sizes in the disc. A shallowing of the slope beyond

3 mm may indicate the presence of at least cm-sized grains.

A similar effect on the cm SED was found for TW Hya (Wilner et al. 2005).

0.25

and their modelling results suggested that IM Lup has grains of at

least mm sizes in the disc. A shallowing of the slope beyond

3 mm may indicate the presence of at least cm-sized grains.

A similar effect on the cm SED was found for TW Hya (Wilner et al. 2005).

3.3 Results from Spitzer infrared observations

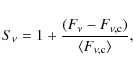

The spectra of the T-Tauri stars observed for Spitzer project P20611,

including sources in Lupus, Corona Australis, and the Gum nebula, are

published for the first time here and shown in Fig. 1. The spectrum of VV CrA is saturated below 10 ![]() m

and excluded from the sample. The spectrum of

SSTc2d J161029.57-392214.7 (P30843, B. Merín PI) will be

published in Merín et al., (2010, in prep.). The spectrum of

SSTc2d J182944.11+003356.1 (P30223, K.M. Pontoppidan PI) will

be published in Oliveira et al. (2010, in prep.).

m

and excluded from the sample. The spectrum of

SSTc2d J161029.57-392214.7 (P30843, B. Merín PI) will be

published in Merín et al., (2010, in prep.). The spectrum of

SSTc2d J182944.11+003356.1 (P30223, K.M. Pontoppidan PI) will

be published in Oliveira et al. (2010, in prep.).

The 10-![]() m silicate features were analysed in the ways of both Furlan et al. (2006) and Kessler-Silacci et al. (2006). Furlan et al. (2006) fitted a third-order polynomial to the

continuum around the 10-

m silicate features were analysed in the ways of both Furlan et al. (2006) and Kessler-Silacci et al. (2006). Furlan et al. (2006) fitted a third-order polynomial to the

continuum around the 10-![]() m feature and determined the integrated flux above and below the continuum. The strength of the 10-

m feature and determined the integrated flux above and below the continuum. The strength of the 10-![]() m

feature was then defined as the ratio of the integrated flux due to the

feature divided by the integrated flux due to the continuum, (

m

feature was then defined as the ratio of the integrated flux due to the

feature divided by the integrated flux due to the continuum, (

![]() )/

)/

![]() ,

resulting in a strength larger than 0 for a feature in emission. Kessler-Silacci et al. (2006)

determined the continuum in three different ways, depending on the full

mid-infrared SED and which data were available for each source, and

subsequently determined the normalised spectra

,

resulting in a strength larger than 0 for a feature in emission. Kessler-Silacci et al. (2006)

determined the continuum in three different ways, depending on the full

mid-infrared SED and which data were available for each source, and

subsequently determined the normalised spectra ![]() according to

according to

|

(1) |

where

For this work, the continuum was consistently chosen for all sources by

fitting a third-order polynomial to data between 5.0 and 7.5 ![]() m and between 13.0 and 16.0

m and between 13.0 and 16.0 ![]() m (cf. Furlan et al. 2006). The regular continuum was used rather than the frequency-averaged continuum, resulting in the peak strength

m (cf. Furlan et al. 2006). The regular continuum was used rather than the frequency-averaged continuum, resulting in the peak strength

![]() and the shape F11.3/F9.8. This does not change the results significantly (see Kessler-Silacci et al. 2006).

and the shape F11.3/F9.8. This does not change the results significantly (see Kessler-Silacci et al. 2006).

The results are listed in Table 4 and shown in Fig. 2. The upper panel of Fig. 2 gives (

![]() )/

)/

![]() vs.

vs.

![]() ,

showing a clear correlation between the two definitions of the strength of the 10-

,

showing a clear correlation between the two definitions of the strength of the 10-![]() m feature. The lower panel gives

m feature. The lower panel gives

![]() vs.

F11.3/F9.8, also showing a correlation, confirming the results of Kessler-Silacci et al. (2006).

This figure also confirms that our sample covers a large range in

silicate-feature characteristics. It follows that the three

methods to quantify the strength or shape of the 10-

vs.

F11.3/F9.8, also showing a correlation, confirming the results of Kessler-Silacci et al. (2006).

This figure also confirms that our sample covers a large range in

silicate-feature characteristics. It follows that the three

methods to quantify the strength or shape of the 10-![]() m feature give completely consistent results. When comparing the 10-

m feature give completely consistent results. When comparing the 10-![]() m

feature with the mm slope in Sect. 5 below, the strength defined as (

m

feature with the mm slope in Sect. 5 below, the strength defined as (

![]() )/

)/

![]() will be used. The source that lies towards the top and to the right of

the general trend in the lower panel is RX J1615.3-3255, an

isolated source slightly to the north of the Lupus star-forming clouds.

will be used. The source that lies towards the top and to the right of

the general trend in the lower panel is RX J1615.3-3255, an

isolated source slightly to the north of the Lupus star-forming clouds.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13150fi2.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13150-09/Timg95.png)

|

Figure 2:

Upper panel: the peak strength of the 10- |

| Open with DEXTER | |

3.4 10- m feature vs. mm slope

m feature vs. mm slope

Figures 3 and 4 show the mm slope ![]() ,

measured between 1 and 3 mm, as a function of the strength of the 10-

,

measured between 1 and 3 mm, as a function of the strength of the 10-![]() m feature

m feature

![]() .

Only the slope between 1 and 3 mm is used, to make the

sample as consistent as possible. However, as noted before,

the slope between 3 and 7 mm is consistent with that

between 1 and 3 mm for most sources. Included are the

sources from this study, as well as eleven sources located in the

Taurus-Auriga star-forming region discussed in Rodmann et al. (2006) and

Andrews & Williams (2007) for which the

spectral slope between 1 and 3 mm could be determined, and

the sources located in Lupus and Chamaeleon discussed in Lommen et al. (2007). The total number of sources used is 31; the complete list is given in Table 5. In Fig. 4,

the sources are sorted by their star-forming region. The smaller

symbols designate single stars and the larger symbols binaries

(or stars that are members of a multiple system). The open

symbol to the left is T Cha, an evolved system that does not

show any silicate emission and is not used in the analysis, and the

open symbol in the centre designates the ``cold disc'' CS Cha.

.

Only the slope between 1 and 3 mm is used, to make the

sample as consistent as possible. However, as noted before,

the slope between 3 and 7 mm is consistent with that

between 1 and 3 mm for most sources. Included are the

sources from this study, as well as eleven sources located in the

Taurus-Auriga star-forming region discussed in Rodmann et al. (2006) and

Andrews & Williams (2007) for which the

spectral slope between 1 and 3 mm could be determined, and

the sources located in Lupus and Chamaeleon discussed in Lommen et al. (2007). The total number of sources used is 31; the complete list is given in Table 5. In Fig. 4,

the sources are sorted by their star-forming region. The smaller

symbols designate single stars and the larger symbols binaries

(or stars that are members of a multiple system). The open

symbol to the left is T Cha, an evolved system that does not

show any silicate emission and is not used in the analysis, and the

open symbol in the centre designates the ``cold disc'' CS Cha.

Table 5: List of sources used in the analysis.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{13150fi3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13150-09/Timg96.png)

|

Figure 3:

The mm slope as measured between 1 and 3 mm as a function of the strength of the 10- |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{13150fi4.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13150-09/Timg97.png)

|

Figure 4:

Same as Fig. 3, with the different sources sorted by star-forming region: filled circles: Lupus, five-pointed stars: Chamaeleon, cross: Corona Australis, diamonds: Taurus-Auriga, and squares:

Serpens. The ellipses show the concentrations of sources located in the

Taurus-Auriga star-forming region (lower left),

the Chamaeleon I cloud (top centre), and the Lupus 1 and

Lupus 2 clouds (upper left). The remaining two Lupus sources in

the upper right are an isolated source (RX J1615-.3-3255,

right-most dot) and a source from the Lupus 3 cloud (RY Lup,

upper-most dot). The small symbols designate the single stars and the

large symbols designate multiple systems. The open five-pointed star to

the left is for T Cha, an evolved cold disc which shows no

silicate emission around 10 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The sources in the sample shown in Fig. 3 lie in a broad band roughly running from the lower left (shallow mm slope and weak 10-![]() m feature) to the upper right (steep mm slope and strong 10-

m feature) to the upper right (steep mm slope and strong 10-![]() m

feature). The sole exception is the source RY Tau, which lies

in the lower right corner. The mm slope and the strength of

the 10-

m

feature). The sole exception is the source RY Tau, which lies

in the lower right corner. The mm slope and the strength of

the 10-![]() m

feature correlate weakly for the full sample: the Spearman rank

correlation coefficient is 0.50, with a 99.5% confidence

level. However, if the point for RY Tau is excluded,

the Spearman rank coefficient becomes 0.66, with

a 99.99% confidence level. Note that RY Tau is a

peculiar source: it is found to be a rapidly rotating UX Or-type

star powering a microjet (e.g., Petrov et al. 1999; Agra-Amboage et al. 2009). A possible explanation for its location in the 10-

m

feature correlate weakly for the full sample: the Spearman rank

correlation coefficient is 0.50, with a 99.5% confidence

level. However, if the point for RY Tau is excluded,

the Spearman rank coefficient becomes 0.66, with

a 99.99% confidence level. Note that RY Tau is a

peculiar source: it is found to be a rapidly rotating UX Or-type

star powering a microjet (e.g., Petrov et al. 1999; Agra-Amboage et al. 2009). A possible explanation for its location in the 10-![]() m-feature

vs mm-slope diagram is a rather evolved disc in which a recent

collision event produced small grains. This may be similar to the

effect recently observed in EX Lup, in which a significantly

more crystalline 10-

m-feature

vs mm-slope diagram is a rather evolved disc in which a recent

collision event produced small grains. This may be similar to the

effect recently observed in EX Lup, in which a significantly

more crystalline 10-![]() m feature was observed after an outburst (Ábrahám et al. 2009). RY Tau will not be included in the further discussion.

m feature was observed after an outburst (Ábrahám et al. 2009). RY Tau will not be included in the further discussion.

Figure 4 suggests a grouping in the ![]() m-vs.-mm diagram

according to parental cloud, with the sources from the Taurus-Auriga

star-forming region more concentrated in the lower left, the Lupus

sources more to the upper left, and the Chamaeleon sources more to the

centre right. Note that the six Lupus sources that are on the left part

of the diagram (from top to bottom: IM Lup, Sz 66,

Sz 65, RU Lup, GW Lup, and HT Lup) are all located

in the Lupus 1 and Lupus 2 clouds, whereas the remaining two

Lupus sources are located in Lupus 3 (top-most source,

RY Lup) and off-cloud (RX J1615.3-3255). Larger-number

statistics are needed to confirm this grouping by star-forming region

in the

m-vs.-mm diagram

according to parental cloud, with the sources from the Taurus-Auriga

star-forming region more concentrated in the lower left, the Lupus

sources more to the upper left, and the Chamaeleon sources more to the

centre right. Note that the six Lupus sources that are on the left part

of the diagram (from top to bottom: IM Lup, Sz 66,

Sz 65, RU Lup, GW Lup, and HT Lup) are all located

in the Lupus 1 and Lupus 2 clouds, whereas the remaining two

Lupus sources are located in Lupus 3 (top-most source,

RY Lup) and off-cloud (RX J1615.3-3255). Larger-number

statistics are needed to confirm this grouping by star-forming region

in the ![]() m-vs.-mm diagram.

m-vs.-mm diagram.

Kessler-Silacci et al. (2006) found a correlation between the spectral type of a source and the strength and shape of the 10-![]() m

silicate feature, brown dwarfs having predominantly flatter and

Herbig-Ae/Be stars having more peaked features. It was found

that this is most likely due to the location of the silicate emission

region: Kessler-Silacci et al. (2007) showed that the radius of the 10-

m

silicate feature, brown dwarfs having predominantly flatter and

Herbig-Ae/Be stars having more peaked features. It was found

that this is most likely due to the location of the silicate emission

region: Kessler-Silacci et al. (2007) showed that the radius of the 10-![]() m silicate emission zone in the disc goes roughly as

m silicate emission zone in the disc goes roughly as

![]() .

Hence, the 10-

.

Hence, the 10-![]() m

feature probes a radius further from the star for early-type stars than

for late-type stars. In this context it is interesting to see whether a

correlation with spectral type is found in the 10-

m

feature probes a radius further from the star for early-type stars than

for late-type stars. In this context it is interesting to see whether a

correlation with spectral type is found in the 10-![]() m-feature vs. mm-slope diagram (Fig. 5).

The M stars in the sample presented here are concentrated to the

left, the F and G stars to the lower left, and the

K stars are found both in the lower left and in the upper right.

Hence, no clear correlation with spectral type is found here.

It is interesting to note, though, that the F and

G sources RY Tau and RY Lup show up isolated from the

other F and G sources. This may indicate that these sources

are indeed different from the other sources in the sample, justifying

the choice not to include RY Tau in the analysis.

m-feature vs. mm-slope diagram (Fig. 5).

The M stars in the sample presented here are concentrated to the

left, the F and G stars to the lower left, and the

K stars are found both in the lower left and in the upper right.

Hence, no clear correlation with spectral type is found here.

It is interesting to note, though, that the F and

G sources RY Tau and RY Lup show up isolated from the

other F and G sources. This may indicate that these sources

are indeed different from the other sources in the sample, justifying

the choice not to include RY Tau in the analysis.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13150fi5.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13150-09/Timg99.png)

|

Figure 5: Same as Fig. 3, with the different sources sorted by spectral type: orange: F and G, blue: K, and green: M. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

4 Modelling

4.1 Disk model parameters and SEDs

Variations in the strength and shape of the 10-![]() m feature (e.g., Kessler-Silacci et al. 2006) as well as in the (sub)mm slope (e.g., Beckwith et al. 1990)

can be explained by variations in the dominating grain size in the

circumstellar discs, so that one may expect a correlation between

properties of the 10-

m feature (e.g., Kessler-Silacci et al. 2006) as well as in the (sub)mm slope (e.g., Beckwith et al. 1990)

can be explained by variations in the dominating grain size in the

circumstellar discs, so that one may expect a correlation between

properties of the 10-![]() m

feature and the mm slope. Such a correlation is found

for the sample as a whole (see previous section) and this may

imply that grain growth occurs in the whole disc simultaneously, or

that grains grow in the inner disc and the new grain size distribution

is very efficiently spread to the outer disc through radial mixing.

Both processes will have the effect of a shift of dust mass from small

particles to larger grains. To study this more quantitatively, we

ran a number of models with varying grain size distributions.

m

feature and the mm slope. Such a correlation is found

for the sample as a whole (see previous section) and this may

imply that grain growth occurs in the whole disc simultaneously, or

that grains grow in the inner disc and the new grain size distribution

is very efficiently spread to the outer disc through radial mixing.

Both processes will have the effect of a shift of dust mass from small

particles to larger grains. To study this more quantitatively, we

ran a number of models with varying grain size distributions.

We use the axisymmetric radiative-transfer code RADMC, developed by Dullemond (2002) and

Dullemond & Dominik (2004). The model

consists of a flaring disc, heated passively by radiation from the

central star, and includes a hot inner wall, which is directly

irradiated by the central star (Natta et al. 2001; see also Dullemond et al. 2001). The surface density of the disc as a function of radius ![]() is defined to be:

is defined to be:

with n = -1. The total gas+dust disc mass was fixed to

For the dust opacities, we use a mixture of 80% amorphous

olivine and 20% armorphous carbon (percentages by mass). The

opacities are calculated using a Distribution of Hollow Spheres (DHS,

see Min et al. 2003). The total volume of the spheres occupied by the inclusion f is taken in the range

f = [0, 0.8]. It was found (e.g. Dullemond & Dominik 2004; D'Alessio et al. 2001; Chiang et al. 2001)

that the mm slope changes if one goes from a disc with only

``small'' particles to a disc that also contains some ``large'' grains.

Dullemond & Dominik started with a disc in which the

dust is made up of only 0.1-![]() m-sized

particles and subsequently replaced 90%, 99%, 99.9%, 99.99%,

and 99.999% of the dust by large, 2-mm-sized grains. The

mm slope changes considerably when the mass fraction in large

grains is changed from 0 to 90%, but it does not change

further if a larger fraction of the dust mass is put in large grains

(see Fig. 7 in Dullemond & Dominik 2004).

This is a result of the fact that at 1 mm the opacity is dominated

by the large grains, virtually independent of the mass fraction

(K. Pontoppidan, priv. comm.). Although it is possible that a more

gradual change in the mm slope is seen when smaller mass fractions

are put in large grains, it does seem to be more important what

the largest grain size is, rather than which fraction of the dust is

contained in such large grains. We therefore chose not to use a bimodal

dust distribution, but a distribution in which the size of the grains

ranges from a minimum value

m-sized

particles and subsequently replaced 90%, 99%, 99.9%, 99.99%,

and 99.999% of the dust by large, 2-mm-sized grains. The

mm slope changes considerably when the mass fraction in large

grains is changed from 0 to 90%, but it does not change

further if a larger fraction of the dust mass is put in large grains

(see Fig. 7 in Dullemond & Dominik 2004).

This is a result of the fact that at 1 mm the opacity is dominated

by the large grains, virtually independent of the mass fraction

(K. Pontoppidan, priv. comm.). Although it is possible that a more

gradual change in the mm slope is seen when smaller mass fractions

are put in large grains, it does seem to be more important what

the largest grain size is, rather than which fraction of the dust is

contained in such large grains. We therefore chose not to use a bimodal

dust distribution, but a distribution in which the size of the grains

ranges from a minimum value

![]() to a maximum value

to a maximum value

![]() according to

according to

|

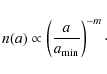

(3) |

This power-law distribution is expected on theoretical grounds whenever grain-grain collisions lead to shattering (Dohnanyi 1969). It should be noted that models which include grain growth may lead to different grain size distributions (e.g., Tanaka et al. 2005; Dullemond & Dominik 2005). The value

Table 6: Model parameters.

The resulting SEDs from six models, with

![]() varying and the other parameters kept fixed, is shown in Fig. 6. In these models,

varying and the other parameters kept fixed, is shown in Fig. 6. In these models,

![]() was

fixed to 300 AU and the scale height was kept fixed at the same

value in all models to show only the effect of varying

was

fixed to 300 AU and the scale height was kept fixed at the same

value in all models to show only the effect of varying

![]() .

Strong variations are seen in all wavelength regimes, from the near-infrared through the mm. At wavelengths

.

Strong variations are seen in all wavelength regimes, from the near-infrared through the mm. At wavelengths

![]()

![]() m, grain size distributions without grains larger than 1

m, grain size distributions without grains larger than 1 ![]() m

give such a high opacity that the central star is significantly

reddened. In the mid- and far infrared, the flux drops with

increasing maximum grain size. The (sub)mm part of the SED does

not

change appreciably unless grains with sizes of

m

give such a high opacity that the central star is significantly

reddened. In the mid- and far infrared, the flux drops with

increasing maximum grain size. The (sub)mm part of the SED does

not

change appreciably unless grains with sizes of ![]() 100

100 ![]() m or larger are included. After that, the (sub)mm slope becomes shallower quite rapidly with increasing

m or larger are included. After that, the (sub)mm slope becomes shallower quite rapidly with increasing

![]() .

This figure also demonstrates that care must be taken when estimating

the disc mass from the (sub)mm emission alone: even when the dust

composition is kept the same, assuming a different grain size

distribution may already change the opacity at 1 mm by an

order of magnitude, which will give an equally large uncertainty in the

mass estimate from an observed flux at that wavelength.

.

This figure also demonstrates that care must be taken when estimating

the disc mass from the (sub)mm emission alone: even when the dust

composition is kept the same, assuming a different grain size

distribution may already change the opacity at 1 mm by an

order of magnitude, which will give an equally large uncertainty in the

mass estimate from an observed flux at that wavelength.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13150fi6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13150-09/Timg121.png)

|

Figure 6:

Spectral energy distributions (SEDs) for models of a 5 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

4.2 10- m feature vs. mm slope

m feature vs. mm slope

In Fig. 7, we plot the strength of the 10-![]() m feature vs. the mm slope for different models. The strength of the 10-

m feature vs. the mm slope for different models. The strength of the 10-![]() m feature

m feature

![]() is defined as in Furlan et al. (2006) and the mm slope

is defined as in Furlan et al. (2006) and the mm slope ![]() is determined between 1.0 and 3.0 mm. The main aim of this figure is to show the variation of the 10-

is determined between 1.0 and 3.0 mm. The main aim of this figure is to show the variation of the 10-![]() m-feature

strength and mm slope with various parameters. While the

quantitative details will depend on the specific dust and disc

parameters used, the qualitative trends found in these figures should

be robust.

m-feature

strength and mm slope with various parameters. While the

quantitative details will depend on the specific dust and disc

parameters used, the qualitative trends found in these figures should

be robust.

In each of the panels, the results for different maximum grain

sizes are shown. The size of the triangles is an indication for the

maximum grain size under consideration. A general trend is

observed, in the sense that the models with only small grains end

up in the upper right corner of the micron-vs.-mm diagram (strong 10-![]() m

feature and steep mm slope), the models which include grains of mm

sizes or larger end up more to the lower left of the diagram (weak 10-

m

feature and steep mm slope), the models which include grains of mm

sizes or larger end up more to the lower left of the diagram (weak 10-![]() m feature and shallower mm slope), and those with grain sizes of up to 10 or 100

m feature and shallower mm slope), and those with grain sizes of up to 10 or 100 ![]() m end up towards the upper left corner of the diagram (weak 10-

m end up towards the upper left corner of the diagram (weak 10-![]() m

feature and steep mm slope). A possible evolutionary

sequence, in which the maximum grain size in the disc gradually

increases, is indicated by the arrows: first, the 10-

m

feature and steep mm slope). A possible evolutionary

sequence, in which the maximum grain size in the disc gradually

increases, is indicated by the arrows: first, the 10-![]() m feature becomes weaker and later, the mm slope becomes shallower. A test to check whether radial variation of

m feature becomes weaker and later, the mm slope becomes shallower. A test to check whether radial variation of

![]() - larger grains closer to the star, where the densities are higher - did not show any significant difference.

- larger grains closer to the star, where the densities are higher - did not show any significant difference.

The models show the effect of the temperature and luminosity of the central star on the strength of the 10-![]() m feature and the steepness of the mm slope. The left column shows the results for a central star with

m feature and the steepness of the mm slope. The left column shows the results for a central star with

![]() K and

K and

![]() and the right column for

and the right column for

![]() K and

K and

![]() .

In Figs. 7a and b, the power-law slope of the grain size distribution is varied from m = 2.5 to 3.0, 3.5, and 4.0. It appears that only grain size distributions with m = 2.5 produce completely flat 10-

.

In Figs. 7a and b, the power-law slope of the grain size distribution is varied from m = 2.5 to 3.0, 3.5, and 4.0. It appears that only grain size distributions with m = 2.5 produce completely flat 10-![]() m silicate features as well as mm slopes with

m silicate features as well as mm slopes with

![]() ,

whereas grain size distributions with m = 4.0 never produce a mm slope with

,

whereas grain size distributions with m = 4.0 never produce a mm slope with

![]() .

Furthermore, the strongest 10-

.

Furthermore, the strongest 10-![]() m features are only obtained with a central star of 4000 K and

m features are only obtained with a central star of 4000 K and

![]() .

.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=17cm,clip]{13150fi7.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13150-09/Timg126.png)

|

Figure 7:

The mm slope |

| Open with DEXTER | |

In Figs. 7c and d, the power-law slope of the grain size distribution is fixed to m = 3.5. The disc radius

![]() is varied between 100, 200, and 300 AU. This has a small effect on the strength of the 10-

is varied between 100, 200, and 300 AU. This has a small effect on the strength of the 10-![]() m feature, particularly for

m feature, particularly for

![]() K and

K and

![]()

![]() m.

This can be understood in the sense that for a smaller disc with the

same dust mass, a larger amount of mass is closer to the star and

thus radiates in the infrared. The mm slope of the SED is practically

unaffected.

m.

This can be understood in the sense that for a smaller disc with the

same dust mass, a larger amount of mass is closer to the star and

thus radiates in the infrared. The mm slope of the SED is practically

unaffected.

Figures 7e and f show the results for models in which the power-law slope of the grain size distribution was fixed to m = 3.5, the disc outer radius to

![]() AU, and for which the inclination i

under which the disc is observed is varied. In most cases,

the inclination has a limited effect on both the strength of the

10-

AU, and for which the inclination i

under which the disc is observed is varied. In most cases,

the inclination has a limited effect on both the strength of the

10-![]() m feature and the mm slope of the SED. Only under very high inclination (e.g., 75

m feature and the mm slope of the SED. Only under very high inclination (e.g., 75![]() ,

where 90

,

where 90![]() is edge-on) does the 10-

is edge-on) does the 10-![]() m