| Issue |

A&A

Volume 511, February 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A58 | |

| Number of page(s) | 15 | |

| Section | Interstellar and circumstellar matter | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200913505 | |

| Published online | 10 March 2010 | |

Radio emission from the massive stars in the galactic super star cluster Westerlund 1

S. M. Dougherty1,2 - J. S. Clark3 - I. Negueruela4 - T. Johnson1,5 - J. M. Chapman6

1 - National Research Council of Canada, Herzberg Institute for

Astrophysics, Dominion Radio Astrophysical Observatory, PO Box 248,

Penticton, British Columbia V2A 6J9, Canada

2 -

Institute for Space Imaging Science, University of Calgary, 2500

University Dr. NW., Calgary, Alberta, T2N 1N4, Canada

3 -

Department of Physics and Astronomy, The Open

University, Walton Hall, Milton Keynes, MK7 6AA, UK

4 -

Dpto. de Física, Ingeniería de Sistemas y Teoría de la

Señal, Universidad de Alicante, Apdo. 99, E03080 Alicante, Spain

5 -

Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Victoria,

3800 Finnerty Rd, Victoria, B.C., V8P 5C2, Canada

6 -

Australia National Telescope Facility, PO Box 76, Epping, NSW 2121,

Australia

Received 20 October 2009 / Accepted 16 November 2009

Abstract

Aims. Current mass-loss rate estimates imply that main

sequence line-driven winds are not sufficient to strip away the H-rich

envelope to yield Wolf-Rayet (WR) stars. The rich transitional

population of the young massive cluster Westerlund 1 (Wd 1)

provides an ideal laboratory to observe and constrain mass-loss

processes throughout the transitional phase of stellar evolution.

Methods. We present an analysis of deep radio continuum

observations of Wd 1 obtained with the Australia Telescope Compact

Array at four frequency bands that permit investigation of the

intrinsic characteristics of the radio emission.

Results. We detect 18 cluster members, a sample dominated by the

cool hypergiants, with additional detections amongst the hotter

OB supergiants and WR stars. The radio properties of the

sample are diverse, with thermal, non-thermal and composite

thermal/non-thermal sources present. Mass-loss rates determined for

stars with partially optically thick stellar winds are ![]() 10-5

10-5 ![]() yr-1

across all spectral types, insufficient to enable the formation of WRs

during a massive star lifetime, and the stars must undergo a period of

greatly enhanced mass loss. The sgB[e] star W9, the brightest

radio source in Wd 1, may provide an example, with a current

mass-loss rate an order of magnitude higher than the other cluster

members, and an extended nebula interpreted as a wind from an earlier

epoch with a density

yr-1

across all spectral types, insufficient to enable the formation of WRs

during a massive star lifetime, and the stars must undergo a period of

greatly enhanced mass loss. The sgB[e] star W9, the brightest

radio source in Wd 1, may provide an example, with a current

mass-loss rate an order of magnitude higher than the other cluster

members, and an extended nebula interpreted as a wind from an earlier

epoch with a density ![]()

![]() the current wind. Such an envelope structure in W9 is reminiscent

of luminous blue variables, and one that shows evidence of two eras of

high, possibly eruptive mass loss. Surprisingly, three of the OB

supergiants are detected, implying unusually dense winds, though they

are embedded in more extended emission regions that may influence the

derived parameters. They also may have composite spectra, suggesting

binarity, which can lead to a higher flux than expected from a stellar

wind. Spatially resolved nebulae are associated with three of the four

RSGs and three of the six YHGs in the cluster, which are due to

quiescent mass loss rather than outbursts. The extended nebulae of W20

and W26 have a cometary morphology, implying significant interaction

with either the intracluster medium or cluster wind. For some of the

cool star winds, the ionizing source may be a companion star though the

cluster radiation density is sufficiently high to provide the necessary

ionizing radiation. Five WR stars are detected with composite

spectra, interpreted as arising in colliding-wind binaries.

the current wind. Such an envelope structure in W9 is reminiscent

of luminous blue variables, and one that shows evidence of two eras of

high, possibly eruptive mass loss. Surprisingly, three of the OB

supergiants are detected, implying unusually dense winds, though they

are embedded in more extended emission regions that may influence the

derived parameters. They also may have composite spectra, suggesting

binarity, which can lead to a higher flux than expected from a stellar

wind. Spatially resolved nebulae are associated with three of the four

RSGs and three of the six YHGs in the cluster, which are due to

quiescent mass loss rather than outbursts. The extended nebulae of W20

and W26 have a cometary morphology, implying significant interaction

with either the intracluster medium or cluster wind. For some of the

cool star winds, the ionizing source may be a companion star though the

cluster radiation density is sufficiently high to provide the necessary

ionizing radiation. Five WR stars are detected with composite

spectra, interpreted as arising in colliding-wind binaries.

Key words: stars: evolution - H II regions - open clusters and associations: individual: Westerlund 1

1 Introduction

Recent work strongly suggests that canonical mass-loss rates for O stars need to be revised downwards to accommodate the effect of wind clumping (Mokiem et al. 2007; Fullerton et al. 2006). Such main sequence (MS) mass-loss rates are insufficient to remove the H-rich mantle of the star prior to it becoming a Wolf Rayet (WR), shifting the burden of mass loss onto the short lived transitional phase of stellar evolution. This phase is populated by a wide variety of highly luminous, hot supergiant B[e] and luminous blue variable (LBV) stars, and cool Yellow Hypergiant (YHG) and red supergiant (RSG) stars. However the exact path of an O star through this transitional ``zoo'' as a function of initial mass is currently poorly understood, while the short-lived epochs, and hence rarity, of such stars complicates efforts to constrain their properties such as mass-loss rate and lifetime.

A better understanding of such short-lived phases in the life cycle of

massive stars is crucial to areas of astrophysics other than just

stellar evolution. For example massive stars are thought to

predominantly form in stellar aggregates, where they drive cluster

winds, which are a major source of mechanical feedback and chemically

processed material into the wider galactic environment, in turn

driving star formation and galactic evolution. Indeed

the feedback from large populations of super star clusters (SSC;

![]()

![]() )

may drive galactic scale

outflows, which, if present in Dwarf galaxies, may be sufficient to

strip them of their interstellar medium, preventing subsequent

generations of star formation (e.g. Westmoquette et al. 2007).

)

may drive galactic scale

outflows, which, if present in Dwarf galaxies, may be sufficient to

strip them of their interstellar medium, preventing subsequent

generations of star formation (e.g. Westmoquette et al. 2007).

One such cluster in the Galaxy is Westerlund 1

(Westerlund 1961), hereafter Wd 1, for which photometric and

spectroscopic observations suggest a unique population of both cool

and hot supergiants (Borgman et al. 1970; Westerlund 1987). Recently,

detailed optical and near-IR observations have confirmed these results

and revealed Wd 1 to be even more extreme than previously anticipated,

containing a large population of post-MS stars with representative

members of all evolutionary stages: OB supergiants and hypergiants,

RSGs, YHGs and WRs (Clark & Negueruela 2002; Clark et al. 2005, henceforth C02 and C05

respectively). Indeed, Wd 1 contains 6 YHGs,

more than 50% of the currently known population in the Galaxy, as

well as one of the largest WR populations of any cluster in the Galaxy

(Crowther et al. 2006). With a cluster mass of ![]() 105

105 ![]() (C05), Wd 1 is directly comparable to the SSCs observed in external

galaxies such as M 82 and thus represents a relatively nearby example

that provides a valuable opportunity to study the properties,

evolution and interaction of massive stars in their ``natural''

environment.

(C05), Wd 1 is directly comparable to the SSCs observed in external

galaxies such as M 82 and thus represents a relatively nearby example

that provides a valuable opportunity to study the properties,

evolution and interaction of massive stars in their ``natural''

environment.

Radio continuum observations are a long established tool for estimating mass-loss rates for early-type stars. As part of a programme to accomplish this for classical Be and B[e] stars, Clark et al. (1998, hereafter C98) imaged Wd 1 at radio wavelengths and found two unusually radio luminous stars; the sgB[e] star W9 and the RSG W26. In both cases the emission was found to be spatially resolved, suggestive of recent mass-loss events. Motivated by these unusual radio properties and the possibility of detecting emission from massive post-MS stars over a broad range of evolutionary stages we carried out a more extensive radio observation of Wd 1 at four frequencies.

We present the results of this survey in this paper. The observations are described in Sect. 2, with the radio sources identified in Sect. 3. Section 4 discusses the nature of the radio sources, Sect. 5 is a brief discussion of the extended emission, and the results are summarized in Sect. 6.

2 Observations

Observation of Wd 1 have been obtained at 8640, 4800, 2496 and 1384 MHz (corresponding to 3, 6, 13 and 20 cm respectively) using the Australia Telescope Compact Array. A first epoch was obtained 1998 March 4-5 in the 6B configuration, followed by observations 2001 January 7-8 in the more compact 750C configuration and on 2002 May 18 (only 8640 and 4800 MHz) in the 6A configuration. Together, these observations ensure good coverage across the spatial frequency range observed, though do not have identical spatial frequency coverage at each frequency. Hence, caution is suggested when comparing flux measures at the different frequencies for resolved, extended emission.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=18cm,clip]{figure1.eps}

\vspace*{6mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/03/aa13505-09/Timg15.png)

|

Figure 1:

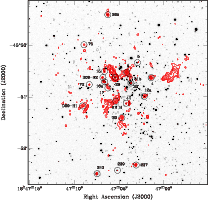

The ATCA observations of Wd 1 at 8.6 GHz ( upper left),

4.8 GHz ( upper right), 2.5 GHz ( lower left) and 1.4 GHz ( lower right). In each image, contour levels are

-3, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, 96, |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Observations of Wd 1 were interleaved with repeated

observations of the nearby bright point source 1657-56 in

order to establish the antenna-based complex gains. Initial editing

and calibration of all observations was done using the M IRIAD

data reduction package (Sault et al. 1995). The gain solutions

established using 1657-56 were subsequently ``referenced'' by

interpolation to the Wd 1 observations. The absolute flux

scale was established using the primary calibrator 1934-638,

assuming fluxes of 2.84, 5.83, 11.14 and 14.94 Jy at 8.6, 4.8, 2.5 and

1.4 GHz respectively. The fluxes derived for 1657-56 are

shown in Table 1. No significant flux variations

(>![]() of the source flux) were noted in preliminary analysis of the

fluxes of the brightest unresolved sources (>2 mJy at 8.6 GHz)

in data from each epoch. Hence, data from the three epochs were

combined into one dataset in order to improve the signal-to-noise

ratio of the data and improve our ability to detect weaker sources.

of the source flux) were noted in preliminary analysis of the

fluxes of the brightest unresolved sources (>2 mJy at 8.6 GHz)

in data from each epoch. Hence, data from the three epochs were

combined into one dataset in order to improve the signal-to-noise

ratio of the data and improve our ability to detect weaker sources.

After phase-referencing and subsequent combination of the data from each epoch, deconvolution was done through visibility model fitting, a technique widely used in VLBI image construction, rather than the commonly used CLEAN technique. This was done using an automated model-fitting routine, the MODCONS macro within the SMERF patch (Reid 2006) to the D IFMAP package (Shepherd 1997). The major advantage of the ``smear fitting'' method implemented by SMERF is that it yields higher resolution for significantly detected features than estimated by the oft-used Rayleigh criteria (Reid 2006), represented by the FWHM of the synthesized beam. A model was established for the 8.6-GHz visibilities consisting of point and Gaussian source models, using the image data to guide the modelling process. This gave a model at the highest observed frequency, and hence at the highest resolution. Once the positions of the model components had been determined, the relatively high signal-to-noise ratio of the brightest sources in the field permitted the use of phase-only self-calibration to improve the antenna gain solutions from those derived from phase referencing alone. A ``best'' model was established with a final round of model fitting, keeping the positions fixed, to refine the flux of the model components. Note that no amplitude self-calibration was carried out using these models. This ``best'' model at 8.6 GHz was then used as the input model at the other frequencies. The resulting images at the four passbands are shown in Fig. 1.

Table 1: Fluxes determined for the phase-reference 1657-56.

|

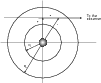

Figure 2:

8.6-GHz image overlaid on a FORS R-band image. The

limiting magnitude of the R-band image is

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Table 2: Characteristics of stellar radio sources in the Wd 1 cluster.

3 The radio sources in Wd 1

3.1 Identification of radio stars

In order to identify stellar counterparts to the radio sources in Wd 1, an R-band image (655 nm effective wavelength) of the cluster was obtained on 2004 June 13 using the FORS2 camera on the VLT. After re-projecting the optical image to the same projection as the ATCA images using the AIPS task OHGEO, the absolute position of the optical image was fixed by assuming that the position of the point source component of the 8.6-GHz emission from W9, the brightest source in the radio image, is coincident with the peak of its optical emission, as determined using AIPS routine MAXFIT. Since the position of 8.6-GHz emission components was established by phase-referencing, the absolute position accuracy of the model components is determined by the accuracy of the position of the phase-reference source 1657-56, and on the residual antenna gain phase as a result of the offset between the position of the phase-reference source and Wd 1, separated by 8.8 degrees. It is estimated this leads to an uncertainty ofThe resulting overlay of the 8.6-GHz image and the R-band image is

shown in Fig. 2. A large number of optical sources

are coincident with radio sources. Setting a ![]() point source

detection limit of

0.23, 0.43, 0.86 and 1.45 mJy beam-1 at 8.6, 4.8, 2.5 and 1.4 GHz respectively, we identify the optical

sources with associated radio emission in Table 2.

point source

detection limit of

0.23, 0.43, 0.86 and 1.45 mJy beam-1 at 8.6, 4.8, 2.5 and 1.4 GHz respectively, we identify the optical

sources with associated radio emission in Table 2.

The position of putative optical counterparts to the radio sources were

also determined using the AIPS routine MAXFIT, and an

offset between the radio and optical positions derived. The

uncertainty in the relative position of the radio and the optical

image is governed by how well the optical image is referenced to the

radio image. By inspection of the position of W9, we estimate

this to be an uncertainty of approximately ![]() 200 mas. This is the

dominant position uncertainty for the sources. Radio sources that have

a position offset from a putative optical ``counterpart'' greater than

600 mas may not be associated, and so these potential

mis-identifications are identified in Table 2.

200 mas. This is the

dominant position uncertainty for the sources. Radio sources that have

a position offset from a putative optical ``counterpart'' greater than

600 mas may not be associated, and so these potential

mis-identifications are identified in Table 2.

A total of 18 stars are identified as radio emitters, with

optical-radio positional offsets <

![]() .

We identify two objects

with associated or potentially associated radio emission for which no

designation is available in the literature. Spectroscopy that could

identify if they are bona-fide cluster members is not available for

these objects so we do not assign Westerlund numbers to them, but name

them as D09-R1 and D09-R2 following the convention used by

Clark et al. (2008, hereafter C08). Three stars are identified as possible radio

emitters (W5, W16a and D09-R2) since they are offset from the

potential radio ``counterpart'' by between 0.6 and 1.0 arcsec, and

some caution may be warranted identifying these stars with the nearby

radio emission.

.

We identify two objects

with associated or potentially associated radio emission for which no

designation is available in the literature. Spectroscopy that could

identify if they are bona-fide cluster members is not available for

these objects so we do not assign Westerlund numbers to them, but name

them as D09-R1 and D09-R2 following the convention used by

Clark et al. (2008, hereafter C08). Three stars are identified as possible radio

emitters (W5, W16a and D09-R2) since they are offset from the

potential radio ``counterpart'' by between 0.6 and 1.0 arcsec, and

some caution may be warranted identifying these stars with the nearby

radio emission.

With this many stellar radio sources, Wd 1 has the richest population of radio emitting stars known for any young massive galactic cluster (e.g. Setia Gunawan et al. 2003; Moffat et al. 2002; Lang 2003). The stellar radio sources are blue, yellow or red super- or hypergiants and WR stars, representative of different stages of massive star evolution. The supergiant B[e] star W9 is by far the brightest stellar radio emitter in the cluster, as anticipated from the ``snapshot'' observation of the cluster presented by C98. Among the other four known blue hypergiants, only the LBV W243 is detected. Wd 1 has one of the richest populations of YHGs known in the Milky Way, with six members of this group (W4, 8a, 12a, 16a, 32, and 265), all of which are detected except for W8a and possibly W16a. All four known RSGs, six of the 16 WR stars in the field-of-view (24 known currently in the cluster), and four OB supergiants, are also associated with radio emission.

A number of sources appear to consist of multiple components (W4, W9, D09-R1 and W237) with a central unresolved source surrounded by a more extended component that is often significantly larger than the synthesized beam of the array. For W4 and W9, the extended component is clearly centred on the stellar source and an association with the extended emission is strongly implied. For D09-R1, the relationship of the stellar source and the extended emission is not as clear since the extended emission is offset from the associated point source.

3.2 Radio star characteristics

The radio fluxes of the sources were deduced from the model components

derived in the model fitting process, which were then corrected for

attenuation by the primary beam of the ATCA, dependent on their

distance from the pointing centre. The FWHM of the ATCA primary beam

is

5.86, 10.06, 19.91 and 34.61 arcmin at 8.6, 4.8, 2.5 and 1.4 GHz respectively. Given the size of the field-of-view is

![]() 4 arcmin, this leads to flux corrections of up to

4 arcmin, this leads to flux corrections of up to

![]() in the outer regions of the field-of-view at 8.6 GHz. In

an attempt to allow for systematic errors, the flux uncertainties

quoted in Table 2 are taken from the maximum of the

following three values: the

in the outer regions of the field-of-view at 8.6 GHz. In

an attempt to allow for systematic errors, the flux uncertainties

quoted in Table 2 are taken from the maximum of the

following three values: the ![]() rms uncertainty in the image, 10% of the source flux, or for resolved sources the rms uncertainty

in the image multiplied by the solid angle of the source. This

represents a conservative approach to estimating the flux

uncertainties, and hence to the estimated spectral indices. However,

it presumes that the model components used to describe a source are

not influenced by other emission from the region surrounding the

source. This may be an additional complication in determining the

fluxes of several sources (WR B, W20 and W26) since they are embedded in

more extended regions of emission that may impact the accuracy of the

derived fluxes. In addition to the source flux, it is noted which sources

appear resolved from the visibility modelling directly, avoiding

the impact of visibility weighting during imaging on the CLEAN

beam size and the subsequent limitations of source modelling in the

image plane.

rms uncertainty in the image, 10% of the source flux, or for resolved sources the rms uncertainty

in the image multiplied by the solid angle of the source. This

represents a conservative approach to estimating the flux

uncertainties, and hence to the estimated spectral indices. However,

it presumes that the model components used to describe a source are

not influenced by other emission from the region surrounding the

source. This may be an additional complication in determining the

fluxes of several sources (WR B, W20 and W26) since they are embedded in

more extended regions of emission that may impact the accuracy of the

derived fluxes. In addition to the source flux, it is noted which sources

appear resolved from the visibility modelling directly, avoiding

the impact of visibility weighting during imaging on the CLEAN

beam size and the subsequent limitations of source modelling in the

image plane.

It is noted that the flux values determined in this study are

approximately 10% higher than the values previously reported by

C98. It is not clear if the apparent increase in the

flux of W9 is due to intrinsic source variations or due to the

absolute calibration scale, given that the uncertainty in the absolute

flux calibration is ![]() 5-10%. We suspect the apparent variation is

due to a combination of absolute calibration uncertainty and the fact

the data used in this study extend to lower spatial frequencies than

in the study of C98, and hence may recover flux that was

``resolved out'' in the earlier observations. We suggest a more

accurate determination of total flux is presented here than in the

previous work.

5-10%. We suspect the apparent variation is

due to a combination of absolute calibration uncertainty and the fact

the data used in this study extend to lower spatial frequencies than

in the study of C98, and hence may recover flux that was

``resolved out'' in the earlier observations. We suggest a more

accurate determination of total flux is presented here than in the

previous work.

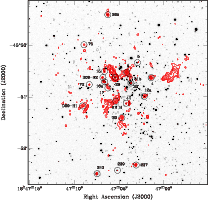

The radio spectral index ![]() ,

where

,

where

![]() ,

for each source was calculated by a weighted regression fit of a

single power-law to the fluxes. Use of a single power-law presumes

there is no curvature in the continuum spectra over the frequency

range observed. Inspection of the spectra of those sources detected at

all bands shows no compelling evidence of curvature, given the

uncertainties in the radiometry at each band. The resulting values for

spectral indices and uncertainties are given in

Table 2 and displayed in

Fig. 3. For sources with radiometry at all

frequency bands, the resulting single power-law index values are less

affected by potential systematic errors in the flux measures at each

band, compared to indices derived across a smaller frequency range

e.g. 8.6 to 4.8 GHz. For sources that are undetected at one or more

bands, and upper limits quoted, only the detected fluxes were used to

calculate spectral index, unless they helped further constrain the

spectral index value e.g. W44. It should be noted that the fluxes for

sources only detected at one or two bands are all low (<1 mJy) and

the uncertainty in the derived spectral indices is high.

,

for each source was calculated by a weighted regression fit of a

single power-law to the fluxes. Use of a single power-law presumes

there is no curvature in the continuum spectra over the frequency

range observed. Inspection of the spectra of those sources detected at

all bands shows no compelling evidence of curvature, given the

uncertainties in the radiometry at each band. The resulting values for

spectral indices and uncertainties are given in

Table 2 and displayed in

Fig. 3. For sources with radiometry at all

frequency bands, the resulting single power-law index values are less

affected by potential systematic errors in the flux measures at each

band, compared to indices derived across a smaller frequency range

e.g. 8.6 to 4.8 GHz. For sources that are undetected at one or more

bands, and upper limits quoted, only the detected fluxes were used to

calculate spectral index, unless they helped further constrain the

spectral index value e.g. W44. It should be noted that the fluxes for

sources only detected at one or two bands are all low (<1 mJy) and

the uncertainty in the derived spectral indices is high.

Table 3: Number of radio emitters of given spectral type.

None of the sources have a completely optically-thick thermal spectrum

(

![]() ), though several have spectra consistent with

), though several have spectra consistent with

![]() ,

expected for a partially optically-thick,

steady-state stellar wind e.g. the compact components in W4, 9, 44 and 243.

,

expected for a partially optically-thick,

steady-state stellar wind e.g. the compact components in W4, 9, 44 and 243.

The majority of the sources have indices that are quite shallow

compared to the expected value for a stellar wind, with many having

indices consistent with -0.1, the value for optically-thin thermal

emission. A combination of optically thick and thin emission

components can give rise to such spectra, such as clumpy stellar winds

where the clumps are optically thick

(e.g. Ignace & Churchwell 2004). Alternatively, in some of these objects

the emission may be due to a combination of thermal and non-thermal

emission forming a composite spectrum, as observed in a number of

massive stars, where the non-thermal emission is attributed to a

colliding-wind binary (CWB) (e.g. Chapman et al. 1999; van Loo et al. 2006; Dougherty & Williams 2000). Depending on the relative strength of

the two continuum components, the spectral index could lie anywhere

between ![]() +0.8 and -0.6, this latter value typical of

optically-thin synchrotron emission. This makes an unequivocal

identification of the underlying emission difficult. To compound

matters, composite spectra due to thermal+non-thermal emission may

not be well represented by a single power-law

(e.g. Pittard et al. 2006). However, identification of

CWBs is helped through observations at other

wavelengths, largely thermal X-ray emission arising from shock-heated

plasma in the wind-collision region, and/or dust emission that appears

to be a common feature in carbon-type WR star massive binaries with

non-thermal emission (Williams 1999).

+0.8 and -0.6, this latter value typical of

optically-thin synchrotron emission. This makes an unequivocal

identification of the underlying emission difficult. To compound

matters, composite spectra due to thermal+non-thermal emission may

not be well represented by a single power-law

(e.g. Pittard et al. 2006). However, identification of

CWBs is helped through observations at other

wavelengths, largely thermal X-ray emission arising from shock-heated

plasma in the wind-collision region, and/or dust emission that appears

to be a common feature in carbon-type WR star massive binaries with

non-thermal emission (Williams 1999).

There are a few sources with indices that, at face value, are more negative than -0.1, suggesting non-thermal emission e.g. W17 and the extended component associated with W4. Other potential members of this group are W16a, D09-R2 and the extended emission near D09-R1 but, as noted earlier, the association of the radio emission with the underlying stars is unclear. The derived spectral index for the extended emission in W4 is consistent with optically- thin thermal emission at the 95% confidence level. This leaves W17 as the only bona-fida non-thermal source.

Additional observations over a broader range of frequencies are required to establish more firmly the nature of the radio emission from the stars in Wd 1. Individual cases are discussed in Sect. 4 where the observations from each stellar sub-type are discussed in detail.

|

Figure 3:

The spectral indices of the stellar radio sources in Wd 1,

identified by their Westerlund numbers. The canonical spectral

indices for partially optically thick thermal emission from a stellar

wind (+0.6) and optically thin thermal emission (-0.1) are

highlighted by the dashed and dotted lines. Error bars are 1

sigma. The arrows denote lower limits to the derived spectral

index. Radio sources offset from potential optical counterparts by

more than 0.6

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Table 4: Properties of the extended radio emission regions in the cluster centre.

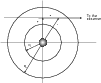

|

Figure 4:

Comparison of radio emission at 8.6 (green) and 4.8-GHz

(red) observations with |

| Open with DEXTER | |

3.3 Extended radio emission

In addition to the radio emission that is associated with stars it is clear there are a number of large, extended emission regions, distributed withinThe total radio flux from Wd 1 as measured in the interferometer

data presented here is 422, 461, 523 and 669 mJy at 8.6, 4.8, 2.2, and

1.4 GHz respectively. This is compared to an interpolation of the

single-dish fluxes reported by Kothes & Dougherty (2007), which gives fluxes

at the same frequencies of 450, 499, 560, and 620 mJy. Given that the

flux uncertainties in the single dish measures is likely ![]() 10%,

the total fluxes derived here from the ATCA data are in excellent

agreement with the single dish fluxes.

10%,

the total fluxes derived here from the ATCA data are in excellent

agreement with the single dish fluxes.

To determine the flux in extended emission, we subtract the radio

emission associated with the stellar sources as given in

Table 2 from the total flux determined by the ATCA.

This leads to fluxes of 307, 351 and 426 mJy at 8.6, 4.8 and 2.2 GHz,

with an uncertainty of ![]()

![]() . The flux at 1.4 GHz is not

quoted since it is difficult to ascertain accurately for the radio

stars, most especially for sources embedded in extended

emission. Comparing these values to those given in

Table 4 and taking into account their

uncertainty, shows good agreement, perhaps degrading toward 2.2 GHz,

which suggests there is little other extended emission in Wd 1 beyond

the regions demarked in Fig. 4.

. The flux at 1.4 GHz is not

quoted since it is difficult to ascertain accurately for the radio

stars, most especially for sources embedded in extended

emission. Comparing these values to those given in

Table 4 and taking into account their

uncertainty, shows good agreement, perhaps degrading toward 2.2 GHz,

which suggests there is little other extended emission in Wd 1 beyond

the regions demarked in Fig. 4.

Using the total fluxes above for the extended emission in Wd 1 gives a

spectral index of

![]() ,

consistent with optically-thin

thermal emission.

Following the prescription given in Sect. 4.3, an 8.6-GHz

flux of 310 mJy from a region

,

consistent with optically-thin

thermal emission.

Following the prescription given in Sect. 4.3, an 8.6-GHz

flux of 310 mJy from a region

![]() in diameter leads to an

ionized mass of 15

in diameter leads to an

ionized mass of 15 ![]() for a plasma temperature of 10 kK, in

excellent agreement with the ionized mass derived by

Kothes & Dougherty (2007).

for a plasma temperature of 10 kK, in

excellent agreement with the ionized mass derived by

Kothes & Dougherty (2007).

C98 showed that the nebular radio emission associated with the RSG W26

correlated with mid-IR emission. Figure 4 shows

an overlay of the radio emission in Wd 1 with Spitzer GLIMPSE data at

![]() m (Benjamin et al. 2003). Without being distracted by the

saturation and artefacts in the mid-IR image, it is striking that all

the extended radio emission is associated with mid-IR emission.

Additionally, note that mid-IR emission is associated with each of the

RSG and YHG stars in the cluster (Sect. 4.3). Such a close

correlation between the ionized emission evidenced in the radio and

the 8

m (Benjamin et al. 2003). Without being distracted by the

saturation and artefacts in the mid-IR image, it is striking that all

the extended radio emission is associated with mid-IR emission.

Additionally, note that mid-IR emission is associated with each of the

RSG and YHG stars in the cluster (Sect. 4.3). Such a close

correlation between the ionized emission evidenced in the radio and

the 8 ![]() m emission is well established in ultra-compact H II regions, where the 8

m emission is well established in ultra-compact H II regions, where the 8 ![]() m emission is due to excited PAH emission

(e.g. Hoare et al. 2007) whereas in more evolved H II regions

there is a clear association with hot dust, and the PAH emission

associated with the photo-dissociation region beyond the ionized gas

(e.g. Povich et al. 2007; Watson et al. 2008)

m emission is due to excited PAH emission

(e.g. Hoare et al. 2007) whereas in more evolved H II regions

there is a clear association with hot dust, and the PAH emission

associated with the photo-dissociation region beyond the ionized gas

(e.g. Povich et al. 2007; Watson et al. 2008)

4 The stellar sources

The post-MS evolution of stars with masses in excess of

![]() 30

30 ![]() is characterized by significant mass loss. While

such mass loss plays a critical role in determining the subsequent

evolution of the stars, the physical processes driving it are

currently ill-constrained, with the mass-loss rate and wind velocities

anticipated to differ by several orders of magnitude depending on the exact

evolutionary phase. Given that Wd 1 is uniquely well stocked with

examples of every known post-MS stellar type, these observations offer

the possibility of constraining this process.

is characterized by significant mass loss. While

such mass loss plays a critical role in determining the subsequent

evolution of the stars, the physical processes driving it are

currently ill-constrained, with the mass-loss rate and wind velocities

anticipated to differ by several orders of magnitude depending on the exact

evolutionary phase. Given that Wd 1 is uniquely well stocked with

examples of every known post-MS stellar type, these observations offer

the possibility of constraining this process.

Consequently, the following discussion on the nature of the radio

emission for the 18 stellar detections is presented in a likely

evolutionary sequence from OB supergiants, through cool

super-/hypergiants, early hypergiants and WN and WC Wolf-Rayet

stars. Given their comparatively weak winds

(![]() 10-7

10-7 ![]() yr-1), the mid-to-late O-type main

sequence progenitors of these stars are not detected

(Martins et al. 2005). The emission associated with the sgB[e] star W9

is discussed outside this evolutionary sequence, due to the uncertain

placement of the sgB[e] phase in the post-MS stellar zoo.

yr-1), the mid-to-late O-type main

sequence progenitors of these stars are not detected

(Martins et al. 2005). The emission associated with the sgB[e] star W9

is discussed outside this evolutionary sequence, due to the uncertain

placement of the sgB[e] phase in the post-MS stellar zoo.

Throughout the discussion it will be assumed that Wd 1 is at a

distance of 4 kpc. Recent deep-IR imaging identifies the MS and pre-MS

populations of Wd 1, leading to a photometric distance of

![]() kpc (Brandner et al. 2008), consistent with both

kpc (Brandner et al. 2008), consistent with both

![]() kpc from an analysis of near-IR photometry of the WR stars

in Wd 1 (Crowther et al. 2006), and on an atomic hydrogen absorption

distance of

kpc from an analysis of near-IR photometry of the WR stars

in Wd 1 (Crowther et al. 2006), and on an atomic hydrogen absorption

distance of ![]() kpc (Kothes & Dougherty 2007).

kpc (Kothes & Dougherty 2007).

4.1 W9 - a luminous radio source

By far the brightest radio source in Wd 1 is W9, with a total flux at 8.6 GHz of 55.4 mJy, giving an 8.6-GHz luminosity ofC98 hypothesised that W9 comprised of two components, a compact stellar wind source and an extended region. The observations presented in this paper support this model, with an unresolved source surrounded by an extended region of emission that are both detected at all four observing frequencies.

The spectral index of the unresolved source coincident with W9 is

![]() ,

consistent with thermal emission arising from a

partially optically thick, steady-state stellar wind with an r-2 radial density distribution. It is assumed this component represents

the present day stellar wind from W9. The spectral index of the

extended region is

,

consistent with thermal emission arising from a

partially optically thick, steady-state stellar wind with an r-2 radial density distribution. It is assumed this component represents

the present day stellar wind from W9. The spectral index of the

extended region is

![]() ,

which we take to be essentially

flat, and arguably consistent with optically-thin thermal

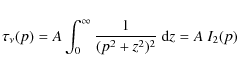

emission. Assuming the extended region has a r-2 radial ion

density distribution, similar to the stellar wind, the lack of a

turnover in its continuum spectrum to a positive spectral index

implies that the extended region is totally optically thick down

to 1.4 GHz. With the free-free opacity for an r-2 ion

distribution at frequency

,

which we take to be essentially

flat, and arguably consistent with optically-thin thermal

emission. Assuming the extended region has a r-2 radial ion

density distribution, similar to the stellar wind, the lack of a

turnover in its continuum spectrum to a positive spectral index

implies that the extended region is totally optically thick down

to 1.4 GHz. With the free-free opacity for an r-2 ion

distribution at frequency ![]() behaving as

behaving as

![]() where p is the impact parameter (see Eq. (A.2)), the lack of a

turnover implies that the extended region must have an inner radius

that is larger than the radius of the

where p is the impact parameter (see Eq. (A.2)), the lack of a

turnover implies that the extended region must have an inner radius

that is larger than the radius of the

![]() surface at 1.4 GHz. In this case, it is suggested that the extended region

represents an earlier phase of mass-loss from W9, prior to the start

of the current stellar wind phase.

surface at 1.4 GHz. In this case, it is suggested that the extended region

represents an earlier phase of mass-loss from W9, prior to the start

of the current stellar wind phase.

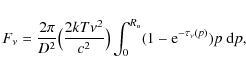

To model the continuum spectra of both the stellar wind and the

extended envelope a shell-like geometry is adopted, with outer and

inner radii ![]() and

and ![]() respectively and with a r-2 radial

ion distribution (e.g. Taylor et al. 1987). The free-free opacity at

radius p in such an envelope is determined using

Eqs. (A.2), (A.3) and (A.4). Together with Eq. (A.1), these

lead to the flux from the envelope at frequency

respectively and with a r-2 radial

ion distribution (e.g. Taylor et al. 1987). The free-free opacity at

radius p in such an envelope is determined using

Eqs. (A.2), (A.3) and (A.4). Together with Eq. (A.1), these

lead to the flux from the envelope at frequency ![]() .

Assuming an

electron temperature

.

Assuming an

electron temperature

![]() kK and an outflow velocity of

200 km s-1, a best-fit of this model to the continuum spectra of

the two components over the four observing frequencies gives the

parameters of the two components (Table 5 and

Fig. 5). The uncertainties in the fitting parameters

are derived in the standard manner of fixing all but one parameter

which is varied until

kK and an outflow velocity of

200 km s-1, a best-fit of this model to the continuum spectra of

the two components over the four observing frequencies gives the

parameters of the two components (Table 5 and

Fig. 5). The uncertainties in the fitting parameters

are derived in the standard manner of fixing all but one parameter

which is varied until ![]() changes by unity.

changes by unity.

|

Figure 5: Model fits to the continuum spectra of the unresolved partially-thick stellar wind ( top) and extended, optically-thin ( bottom) components of W9. The solid lines represent the best-fit model when the stellar wind outer radius/extended inner radii are constrained to be identical (Model 3). The dotted spectra are the best-fit models when the stellar wind outer radius and extended region inner radius are free parameters (Models 1 and 2). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Table 5: Best-fit parameters of the r-2 shell model applied to the continuum spectra of the compact and extended radio components of W9.

A total of three models were examined. Model 1 leads to a mass-loss

rate of

![]()

![]() yr-1 for

yr-1 for

![]() kK (e.g. Leitherer & Robert 1991) for a

volume filling factor for clumps f (Abbott et al. 1981). The

mass-loss rate is scaled to 200 km s-1 since the outflow

velocity in W9 is not well constrained with observed line widths that

range between 40 and 800 km s-1 (C08). Assuming the

same outflow velocity and clump structure, the derived mass-loss rate

of the extended region (Model 2) is approximately twice as high as the

current phase of mass-loss, implying an earlier era of higher

mass-loss rate

kK (e.g. Leitherer & Robert 1991) for a

volume filling factor for clumps f (Abbott et al. 1981). The

mass-loss rate is scaled to 200 km s-1 since the outflow

velocity in W9 is not well constrained with observed line widths that

range between 40 and 800 km s-1 (C08). Assuming the

same outflow velocity and clump structure, the derived mass-loss rate

of the extended region (Model 2) is approximately twice as high as the

current phase of mass-loss, implying an earlier era of higher

mass-loss rate ![]() 10-4

10-4 ![]() yr-1.

yr-1.

The model spectrum of the individual radio components established that

the best-fit outer radius of the compact component (the current

stellar wind) is greater than the inner bound of the extended region

(earlier phase of mass-loss). If the mass-loss that produced both

components is radially symmetric, it is not plausible for the inner

radius of the extended region to be smaller than the extent of the

current stellar wind. The third model (Model 3) assumed the inner

bound of the extended region is at least as large as the outer bound

of the current stellar wind. Fitting both continuum spectra

simultaneously through minimizing the total ![]() from

the two

models gives the parameters of Model 3, which supports a factor of

3 higher mass-loss rate in the earlier phase of mass-loss than in

the

current stellar wind. The resulting model fits to the data are shown

in Fig. 5.

from

the two

models gives the parameters of Model 3, which supports a factor of

3 higher mass-loss rate in the earlier phase of mass-loss than in

the

current stellar wind. The resulting model fits to the data are shown

in Fig. 5.

The derived mass-loss rate for the putative earlier mass-loss phase is

high for a massive star, being of the same order as the the current

mass-loss rate in ![]() Carina of

Carina of ![]() 10-4 - 10-3

10-4 - 10-3 ![]() yr-1 (Corcoran 2008). The inner bound

of

yr-1 (Corcoran 2008). The inner bound

of ![]() 4000 AU suggests that this mass-loss epoch would have ended

4000 AU suggests that this mass-loss epoch would have ended

![]() 200 yr ago assuming an outflow velocity of 200 km s-1,

followed subsequently by the current mass-loss phase with

200 yr ago assuming an outflow velocity of 200 km s-1,

followed subsequently by the current mass-loss phase with ![]() lower density.

lower density.

With such a model for the circumstellar environment, what does this

imply for the evolutionary status of W9? While veiling any

photospheric features, the rich optical-IR emission line spectrum and

IR excess indicate a rich circumstellar environment and permit a

formal sgB[e] star classification (C08; Ritchie et al. 2010). However

spectral peculiarities exist when compared to other examples; most

notably the unusual composite line profiles of He I 5876 and

6678 ![]() .

The X-ray emission from W9 supports a binary system, being

too hard (

.

The X-ray emission from W9 supports a binary system, being

too hard (![]() keV) and bright (

keV) and bright (

![]() erg s-1)

to arise in a single star, although it does not constrain the nature

of the components (C08; Ritchie et al. 2010). Likewise, while W9 is

found to be photometrically variable, no period has been identified

currently (Bonanos 2007). Identification of W9 as a binary

awaits further supporting observational evidence.

erg s-1)

to arise in a single star, although it does not constrain the nature

of the components (C08; Ritchie et al. 2010). Likewise, while W9 is

found to be photometrically variable, no period has been identified

currently (Bonanos 2007). Identification of W9 as a binary

awaits further supporting observational evidence.

The current mass-loss rate of W9 is approximately an order of

magnitude higher than that inferred for any of the other transitional

stars within Wd 1. It is directly comparable to those of the LBVs

AFGL 2298, AG Car, FMM 362 and the Pistol

star in quiescence with

![]()

![]() yr-1 (Najarro et al. 2009; Groh et al. 2009; Clark et al. 2009), despite being a factor of

yr-1 (Najarro et al. 2009; Groh et al. 2009; Clark et al. 2009), despite being a factor of ![]()

![]() less

luminous

less

luminous![]() . Moreover, depending on the outflow

velocity and wind-clumping factor the mass-loss rate for W9 is

uncomfortably close to the limit expected for a line-driven wind for

which Smith & Owocki (2006) estimate a maximum mass-loss rate of

. Moreover, depending on the outflow

velocity and wind-clumping factor the mass-loss rate for W9 is

uncomfortably close to the limit expected for a line-driven wind for

which Smith & Owocki (2006) estimate a maximum mass-loss rate of

Such a high mass-loss rate and the presence of a detached shell of material formed in a previous phase of enhanced mass loss is suggestive of an LBV identification, with

However, while the current observational data are consistent with the

ejecta being formed as a result of the post-MS evolution of

a single massive star, its formation in an interacting binary system

undergoing significant mass transfer, in turn leading to common

envelope evolution, also appears viable and well motivated given the

evidence of W9 being a binary. Examples of massive binaries with both

a normal and a relativistic companion are known: RY Scuti and SS433

respectively, and thus provide observational templates. As with W9,

both these systems have rich emission-line spectra and IR excesses due

to the presence of circumstellar dust (Gehrz et al. 1995; Clark et al. 2007, and references

therein). More interestingly, both are

associated with compact, bright radio nebulae with sizes and fluxes

directly comparable to W9 yet attributed to mass lost through binary

interaction (Gehrz et al. 1995; Blundell et al. 2001). The former authors

derive a mass-loss rate of the order of 10-4 ![]() yr-1from the radio observations for SS433, while the latter infer an

ionized mass of 10-3

yr-1from the radio observations for SS433, while the latter infer an

ionized mass of 10-3 ![]() for the nebula associated with

RY Scuti, with a mass-loss rate of

for the nebula associated with

RY Scuti, with a mass-loss rate of ![]() 10-4 -

10-5

10-4 -

10-5 ![]() yr-1 inferred from optical emission lines

(de Martino et al. 1992); both rates are comparable with W9.

yr-1 inferred from optical emission lines

(de Martino et al. 1992); both rates are comparable with W9.

4.2 The OB supergiants

Currently, there areConsequently, the apparent detections of W15 and W17 (O9Ib and O9Iab respectively - Negueruela et al., in prep.), D09-R1 and potentially D09-R2 (both B0I or earlier; C08) are somewhat unexpected, most especially considering that these stars are unremarkable compared with the rest of the OB stars studies spectroscopically. Of note is that W15, W17 and D09-R1 all are coincident with extended emission regions and the parameters of the unresolved radio components coincident with the underlying stars are likely influenced by this extended emission. As a result, the derived parameters may not reflect the intrinsic properties of the underlying stars, but rather the extended plasma region.

That withstanding, W17 has a spectral index marginally steeper than

-0.1, hinting at non-thermal emission and a potential CWB. However, we

note it does not have detected X-ray emission C08 and

shows no evidence of RV variations (Ritchie et al. 2009a). W15 has a

spectral index lower limit of 0.0, and it is not possible to

distinguish whether the emission is from either a stellar wind or a

non-thermal/thermal composite source. It shows no evidence for

binarity in either RV observations (Ritchie et al. 2009a) or X-ray

observations (C08), where the emission is soft

(![]() keV) and at a level expected for a single O-type star

(

keV) and at a level expected for a single O-type star

(![]()

![]() erg s-1; e.g. Berghoefer et al. 1997) as

a result of shock heating within the stellar wind. Nevertheless, if

the radio flux is attributed to thermal emission from a stellar wind,

W15 would have an unusually high mass-loss rate of

erg s-1; e.g. Berghoefer et al. 1997) as

a result of shock heating within the stellar wind. Nevertheless, if

the radio flux is attributed to thermal emission from a stellar wind,

W15 would have an unusually high mass-loss rate of

![]()

![]() yr-1 in comparison to other

late-O/early-B supergiants (Mokiem et al. 2007; Crowther et al. 2006).

The

absence of RV variations in these stars does not rule out a binary

interpretation unequivocally since the mass ratios may be extreme and

the inclination of the orbit unfavorable for ready detection of

RV variations. Furthermore, the orbital period could be

significantly in

excess of the observation timescale.

yr-1 in comparison to other

late-O/early-B supergiants (Mokiem et al. 2007; Crowther et al. 2006).

The

absence of RV variations in these stars does not rule out a binary

interpretation unequivocally since the mass ratios may be extreme and

the inclination of the orbit unfavorable for ready detection of

RV variations. Furthermore, the orbital period could be

significantly in

excess of the observation timescale.

The spectral index of the point source associated with D09-R1 is complicated by the presence of an extended component, and given the absence of both optical spectroscopy and an X-ray detection, it is simply concluded that the nature of this emission remains uncertain, and note that if it is assumed to be a stellar wind, the same problems with respect to an extreme mass-loss rate as found for W15 are encountered.

4.3 The cool super- and hypergiants

All four of the RSGs and at least four of the six YHGs in Wd 1 are radio sources. Irrespective of the uncertain identification of W16a as a radio emitter, the fraction of radio sources amongst both these classes of object is high. Of the RSGs, W75 was the weakest source detected and was unresolved at any wavelength. The other three detected RSGs (W20, 26 and 237) have extended radio emission.

For both W20 and W26 the radio emission is best characterised by two

components: a compact (![]()

![]() ), spatially resolved source

coincident with the star, and a more extended nebula

(>

), spatially resolved source

coincident with the star, and a more extended nebula

(>

![]() ). W237 is similar in structure though the inner

component coincident with the star is unresolved. In W20 and W26 the

more extended components have a distinct cometary morphology that

extends away from the central region of the cluster, while that in W237 is more elliptical.

). W237 is similar in structure though the inner

component coincident with the star is unresolved. In W20 and W26 the

more extended components have a distinct cometary morphology that

extends away from the central region of the cluster, while that in W237 is more elliptical.

The radio properties of the YHGs are more heterogeneous. W8 is not detected. W32 is associated with a weak point source, while W12 and W265 are associated with compact resolved sources, similar to the RSG radio sources. Finally, the radio emission from W4 consists of a point source at the position of the star surrounded by an extended component.

The majority of the cool super- and hypergiants have spectral

indices that are flat, within the uncertainties. Unlike OB and

WR stars, composite thermal and non-thermal spectra have not been

identified previously, and are not expected. Hence we identify these

indices with optically-thin thermal emission. For a Maxwellian plasma

at temperature T, the optically-thin radio flux density is given by

where D is the distance in kpc and EV is the emission integral

at 8.6 GHz. The total ionized mass can then be determined from

The ionized masses of the nebulae, based on the source parameters

determined at 8.6 GHz, are given in Table 6. Note

this is not the total mass since these observations are insensitive to

any neutral component. On average, the emission integral

![]() cm-3, implies an ionizing

luminosity that has to be greater than

cm-3, implies an ionizing

luminosity that has to be greater than

![]() s-1, where

s-1, where

![]() is the is the hydrogen

recombination rate to all but the ground state. Such ionizing

luminosity is not available from these relatively cool stars with

stellar effective temperatures

is the is the hydrogen

recombination rate to all but the ground state. Such ionizing

luminosity is not available from these relatively cool stars with

stellar effective temperatures ![]() 5000 K

(e.g. de Jager 1998).

5000 K

(e.g. de Jager 1998).

How are these envelopes ionized? A cluster of mass 105 ![]() and solar metallicity can easily provide such a photon luminosity and

seems the most likely source of the ionizing radiation. Taking the

cluster to be approximately 1 pc across and with

and solar metallicity can easily provide such a photon luminosity and

seems the most likely source of the ionizing radiation. Taking the

cluster to be approximately 1 pc across and with ![]() 100 OB-type

stars implies that on average each OB star occupies a volume

0.04 pc3, and is separated from the next OB star by

100 OB-type

stars implies that on average each OB star occupies a volume

0.04 pc3, and is separated from the next OB star by

![]() 0.34 pc. If each OB star provides 1048 s-1 ionizing

photons (Martins et al. 2005), with

0.34 pc. If each OB star provides 1048 s-1 ionizing

photons (Martins et al. 2005), with ![]() 1045 s-1 required to

fully ionize the cool hypergiant envelopes, suggests a radiation

dilution factor

1045 s-1 required to

fully ionize the cool hypergiant envelopes, suggests a radiation

dilution factor ![]() (R*/D)-2 less than 1000, which implies

the hypergiant envelopes are

(R*/D)-2 less than 1000, which implies

the hypergiant envelopes are ![]() 0.01 pc radius. This is closely

consistent with the sizes observed for RSG nebulae e.g. VY CMa (see

Sect. 4.3.2).

0.01 pc radius. This is closely

consistent with the sizes observed for RSG nebulae e.g. VY CMa (see

Sect. 4.3.2).

Alternatively, a hot companion star could provide the required photon flux, which at 1045-46 s-1 implies an early B-type star. The YHG HR 8752 provides a precedent for such a model: it is detected at radio wavelengths and together with [N II]-emission lines, needs a source of ionizing radiation that is provided by a putative B1 companion (Stickland & Harmer 1978). In this respect we highlight the presence of [N II]-emission lines in the optical spectra of W20, W237 and W265 (Clark et al. 2010).

If the plasma in these optically-thin nebulae is due to mass loss from the underlying stars, having optically-thin spectra down to a frequency of 1.4 GHz implies that the ionized extended envelopes have inner radii significantly larger than the stellar radii. If this is the case, two possible models for the envelope can be advanced. The mass loss from these objects could have stopped or significantly decreased at some point in the past resulting in a detached shell. Alternatively, the ionized region may only occupy the periphery of the envelope, with the interior part of the envelope being neutral. Such a geometry could result from external ionization from the cluster radiation field. High-resolution observations are required to substantiate either of these potential models.

Table 6: Ionized mass estimates for the optically-thin stellar nebulae around the YHGs (top panel) and RSGs (bottom panel) in Wd 1.

4.3.1 The yellow hypergiants

Given the rarity of YHGs and the difficulty identifying suitable

observational diagnostics, few measurements of the quiescent or

outburst wind velocities and mass-loss rates of YHGs exist in the

literature. For HD 33579 (A3Ia+) in the LMC,

Stahl et al. (1991) quote

![]() km s-1 and

km s-1 and

![]()

![]() yr-1, and Israelian et al. (1999)

report

yr-1, and Israelian et al. (1999)

report

![]() km s-1 and

km s-1 and

![]()

![]() yr-1 for HR 8752 in 1998. For the well-known example

yr-1 for HR 8752 in 1998. For the well-known example ![]() Cas, Lobel et al. (1998) find

Cas, Lobel et al. (1998) find

![]() km s-1 and

km s-1 and

![]()

![]() yr-1 in 1993, in contrast to

yr-1 in 1993, in contrast to

![]() km s-1 and

km s-1 and

![]()

![]() yr-1 during the 2000 outburst

(Lobel et al. 2003). Castro-Carrizo et al. (2007) measure outflow

velocities of 35 km s-1 and 25-37 km s-1 for the ejecta

associated with HD 179821 and IRC +10 420 (although

a priori it is not clear if they were ejected in a RSG or YHG

phase). For both these stars, variable mass-loss rates of

yr-1 during the 2000 outburst

(Lobel et al. 2003). Castro-Carrizo et al. (2007) measure outflow

velocities of 35 km s-1 and 25-37 km s-1 for the ejecta

associated with HD 179821 and IRC +10 420 (although

a priori it is not clear if they were ejected in a RSG or YHG

phase). For both these stars, variable mass-loss rates of

![]()

![]() yr-1 and

yr-1 and

![]()

![]() yr-1 were found respectively

during the nebulae formation events, with Blöcker et al. (1999) also

reporting a mass-loss rate in excess of 10-3

yr-1 were found respectively

during the nebulae formation events, with Blöcker et al. (1999) also

reporting a mass-loss rate in excess of 10-3 ![]() yr-1for IRC +10 420 in the recent past. These works all suggest that

during outburst the mass-loss rates in YHGs are higher than during

quiescence whereas the outflow velocity is lower during outburst.

yr-1for IRC +10 420 in the recent past. These works all suggest that

during outburst the mass-loss rates in YHGs are higher than during

quiescence whereas the outflow velocity is lower during outburst.

Taking a mean 8.6-GHz flux of 2.5 mJy for the YHGs, their radio

luminosity is

![]() erg s-1. The only other radio

detected YHG in the Galaxy, HR 8752, has an 8.6-GHz flux of 17 mJy

(Dougherty et al., in prep.) at a distance of 1.7 kpc, giving a

luminosity of

erg s-1. The only other radio

detected YHG in the Galaxy, HR 8752, has an 8.6-GHz flux of 17 mJy

(Dougherty et al., in prep.) at a distance of 1.7 kpc, giving a

luminosity of

![]() erg s-1, similar to the YHGs in

Wd 1. HR 8752 has been interpreted to have a stellar wind from

measured spectral indices of

erg s-1, similar to the YHGs in

Wd 1. HR 8752 has been interpreted to have a stellar wind from

measured spectral indices of

![]() (Higgs et al. 1978) and

(Higgs et al. 1978) and

![]() (Dougherty et al., in prep.). Only the compact

component in W4 appears to have a spectral index consistent with a

stellar wind (

(Dougherty et al., in prep.). Only the compact

component in W4 appears to have a spectral index consistent with a

stellar wind (

![]() ), but given the uncertainty, arguably

also consistent with optically-thin thermal emission. Assuming

), but given the uncertainty, arguably

also consistent with optically-thin thermal emission. Assuming

![]() and

and

![]() as for W9 and that the putative wind from W4

is fully ionized and smooth (f=1) gives a mass-loss rate of

as for W9 and that the putative wind from W4

is fully ionized and smooth (f=1) gives a mass-loss rate of

![]()

![]() yr-1. This is consistent within a factor

of a few with the quiescent mass-loss rates of HD 33579,

HR 8752 and

yr-1. This is consistent within a factor

of a few with the quiescent mass-loss rates of HD 33579,

HR 8752 and ![]() Cas, but significantly lower than

inferred for

Cas, but significantly lower than

inferred for ![]() Cas, HD179821 and IRC

+10 420 during outburst, especially for comparably low velocities

(<40 km s-1).

Cas, HD179821 and IRC

+10 420 during outburst, especially for comparably low velocities

(<40 km s-1).

The extended nebulae around W4, W12a and W265 have masses of

![]()

![]() and radii of

and radii of ![]() 0.02 pc (based on

the major axis size in Table 6). An assumed

outflow velocity of

0.02 pc (based on

the major axis size in Table 6). An assumed

outflow velocity of ![]() 200 km s-1 gives a flow time of

200 km s-1 gives a flow time of

![]() 100 yr, during which time mass loss at a rate of

100 yr, during which time mass loss at a rate of

![]() 10-5

10-5 ![]() yr-1, as found for W4 above, yields a

total mass loss of 10-3

yr-1, as found for W4 above, yields a

total mass loss of 10-3 ![]() .

Thus, by comparison with the

cases of

.

Thus, by comparison with the

cases of ![]() Cas,

IRC +10 420 and HR 8752, the radio

nebulae associated with the YHGs in Wd 1 may be the

result of quiescent mass loss, rather than an outburst phase.

Cas,

IRC +10 420 and HR 8752, the radio

nebulae associated with the YHGs in Wd 1 may be the

result of quiescent mass loss, rather than an outburst phase.

None of the YHGs in Wd 1 possess the old (![]() 4000 yr), massive

(M>1

4000 yr), massive

(M>1 ![]() )

ejection nebulae seen in HD 179821 and IRC +10 420

(Castro-Carrizo et al. 2007; Oudmaijer et al. 1996). We suspect that in the

extreme environment of Wd 1 such nebulae would quickly be ablated by

the cluster wind arising from the OB stars - as appears to be the case

for the RSGs W20 and W26 (see Sect. 4.3.2). However we

cannot exclude the possibility that the YHGs may be evolving to cooler

temperatures (redwards) and have yet to encounter the instabilities

leading to extreme mass-loss rates in either the RSG or post-RSG

phase. A mixture of both pre- and post-RSG objects combined with the

intrinsic variability of YHGs (Clark et al. 2010) may explain the

heterogeneous radio properties of the Wd 1 population. This argument

is supported by evidence that even the best two candidates for

post-RSG stars, HD 179821 and IRC +10 420, exhibit quite dissimilar

nebular properties (Patel et al. 2008; Oudmaijer et al. 2009).

)

ejection nebulae seen in HD 179821 and IRC +10 420

(Castro-Carrizo et al. 2007; Oudmaijer et al. 1996). We suspect that in the

extreme environment of Wd 1 such nebulae would quickly be ablated by

the cluster wind arising from the OB stars - as appears to be the case

for the RSGs W20 and W26 (see Sect. 4.3.2). However we

cannot exclude the possibility that the YHGs may be evolving to cooler

temperatures (redwards) and have yet to encounter the instabilities

leading to extreme mass-loss rates in either the RSG or post-RSG

phase. A mixture of both pre- and post-RSG objects combined with the

intrinsic variability of YHGs (Clark et al. 2010) may explain the

heterogeneous radio properties of the Wd 1 population. This argument

is supported by evidence that even the best two candidates for

post-RSG stars, HD 179821 and IRC +10 420, exhibit quite dissimilar

nebular properties (Patel et al. 2008; Oudmaijer et al. 2009).

4.3.2 The red supergiants

Given very high mass-loss rates inferred for extremely luminous RSGs

(log (

![]() ) > 5.5), it is suspected that they play an

important role in post-MS evolution of stars at the Humphreys-Davidson

limit. Consequently, they have been the subject of numerous

(multi-wavelength) studies to constrain their mass-loss histories. Of

the Galactic examples, Schuster et al. (2006) used the HST/WFPC2 to

identify compact (

) > 5.5), it is suspected that they play an

important role in post-MS evolution of stars at the Humphreys-Davidson

limit. Consequently, they have been the subject of numerous

(multi-wavelength) studies to constrain their mass-loss histories. Of

the Galactic examples, Schuster et al. (2006) used the HST/WFPC2 to

identify compact (

![]() pc) nebulae associated with NML Cyg, VX Sgr and S Per, with Morris & Jura (1983) also

associating a much larger (>1 pc) H II region with

NML Cyg. de Wit et al. (2008) report the presence a nebula

around

pc) nebulae associated with NML Cyg, VX Sgr and S Per, with Morris & Jura (1983) also

associating a much larger (>1 pc) H II region with

NML Cyg. de Wit et al. (2008) report the presence a nebula

around ![]() Cep at 25 microns (

Cep at 25 microns (

![]() pc); a comparably

sized nebulae surrounds VY CMa (

pc); a comparably

sized nebulae surrounds VY CMa (

![]() pc in

HST/WFPC2 images; Smith et al. 2001). Finally Serabyn et al. (1991) and

Yusef-Zadeh & Morris (1991) report the presence of an asymmetric nebula

(

pc in

HST/WFPC2 images; Smith et al. 2001). Finally Serabyn et al. (1991) and

Yusef-Zadeh & Morris (1991) report the presence of an asymmetric nebula

(![]() 1pc in length) around the Galactic Centre RSG IRS7 at both

near-IR and radio wavelengths.

1pc in length) around the Galactic Centre RSG IRS7 at both

near-IR and radio wavelengths.

As with these stars, the discovery of large nebulae associated with three of the 4 RSGs in Wd 1 (major axis >0.2 pc; Table 6) emphasises the role of mass loss in this evolutionary stage. NML Cyg and IRS7 are of special interest in the context of the RSGs in Wd 1, given that these stars are also located within dense stellar aggregates, namely Cyg OB2 (Morris & Jura 1983) and the Galactic Centre cluster (e.g. Yusef-Zadeh & Morris 1991) respectively. Indeed the pronounced cometary nebulae of W20 and W26 appear similar both in morphology and linear scale to that of IRS7. Consequently we attribute the shape of these nebulae to a similar physical process, namely the interaction of the ejecta/RSG stellar wind with the cluster medium/wind. Lacking dynamical information, we refrain from attempting a quantitative analysis of the nebular morphologies, but note that the unremarkable radial velocities found for these stars by Mengel & Tacconi-Garman (2007) suggest that the dominant cause of ram pressure shaping the nebulae is the expansion of the cluster wind, rather than the rapid motion of the stars through a quasi-static cluster medium. This is supported by the orientation of each of these cometary nebulae away from the cluster centre region.

The morphology of the radio nebula associated with W237 suggests it

has been less affected by the cluster wind than either W20 or W26.

Adopting an outflow velocity of 30 km s-1 for the RSG wind, the

mass of 0.07 ![]() and radius of

and radius of ![]() 0.11 pc

(Table 6) results in a kinematic age of 3600 yr

and a time averaged mass-loss rate of

0.11 pc

(Table 6) results in a kinematic age of 3600 yr

and a time averaged mass-loss rate of

![]()

![]() yr-1.

This age supports the

suggestion that the radio nebula is little affected by the cluster

wind, otherwise it likely would be ablated as observed in W20

and W26. This is consistent with its position further from the

cluster

centre than either W20 or W26. The derived mass-loss rate is

comparable to the mass-loss rates found for field RSGs, which range

from 10-6-10-4

yr-1.

This age supports the

suggestion that the radio nebula is little affected by the cluster

wind, otherwise it likely would be ablated as observed in W20

and W26. This is consistent with its position further from the

cluster

centre than either W20 or W26. The derived mass-loss rate is

comparable to the mass-loss rates found for field RSGs, which range

from 10-6-10-4 ![]() yr-1 (Jura & Kleinmann 1990; Sylvester et al. 1998), although transient rates as high as

yr-1 (Jura & Kleinmann 1990; Sylvester et al. 1998), although transient rates as high as

![]() 10-3

10-3 ![]() yr-1 are seen in NML Cyg and VY

Cma (Smith et al. 2001; Blöcker et al. 2001) and as low as a

yr-1 are seen in NML Cyg and VY

Cma (Smith et al. 2001; Blöcker et al. 2001) and as low as a ![]() few

10-7

few

10-7 ![]() in

in ![]() Cep (de Wit et al. 2008) have

been observed.

Cep (de Wit et al. 2008) have

been observed.

Moreover, both W20 and W26 have similar nebular masses to W237 and, in turn, all three are directly comparable to that of the nebula surrounding VY CMa (Smith et al. 2001). Consequently the ejecta associated with the RSGs within Wd 1 appear to be the result of similarly extreme, possibly transient mass-loss events as those that yield the nebulae around other Galactic RSGs (e.g. Smith et al. 2001). In this respect, the apparent instabilities in W26 and W237 are of interest (Clark et al. 2010).

4.4 The B hypergiants

The final subset of transitional stars to be considered are the B hypergiants, which likely represent the immediate progenitors of WN-type stars. Included in this group are the LBV W243 and the cool B-type hypergiants W7, 33 and 42. The final member is the early-B hypergiant W13, which emphasises the close physical continuity between the B hypergiants and the hydrogen-rich late-WN stars such as W44 (=WR L (WN9h); C08) detected at 8.6 GHz (Table 2 and Sect. 4.5). Of these stars, only W243 has a spectral index indicative of thermal wind emission.W243 has recently been the subject of an extensive spectroscopic study by Ritchie et al. (2009b). This confirmed the finding of C02 that W243 had substantially cooled since the previous observations (e.g. Westerlund 1987), with the stellar temperature between 2002-8 being 8-9kK, with a formal spectral classification of mid-A type and a photospheric absorption spectrum of a YHG. However, detailed non-LTE analysis were unable to simultaneously reproduce these features and the prominent H I and He I emission lines, leading Ritchie et al. (2009b) to conclude that W243 harbored a hot binary companion. Unfortunately, current spectroscopic data are unable to constrain the nature of the hot companion; nevertheless at this time W243 closely resembles the known YHG binary HR8752 (Sect. 4.3.1) and we assume that the hot companion is responsible for the ionization of its wind.

Given the current properties of W243 we adopt identical values

of Z, ![]() and

and ![]() as used for the YHG W4, leading to a

mass-loss rate of

as used for the YHG W4, leading to a

mass-loss rate of

![]() ,

which is

directly comparable to W4. This is to be expected considering their

similar radio fluxes (Table 2). This mass-loss rate

is an order of magnitude higher than that found by

Ritchie et al. (2009b), correcting for difference in assumed outflow

velocity, though it should be noted that the observed optical spectrum

is relatively insensitive to the current mass-loss rate. Assuming a

4

,

which is

directly comparable to W4. This is to be expected considering their

similar radio fluxes (Table 2). This mass-loss rate

is an order of magnitude higher than that found by

Ritchie et al. (2009b), correcting for difference in assumed outflow

velocity, though it should be noted that the observed optical spectrum

is relatively insensitive to the current mass-loss rate. Assuming a

4![]() -detection limit of 0.24 mJy for the remaining stars yields a

corresponding upper limit to the mass-loss rates of

-detection limit of 0.24 mJy for the remaining stars yields a

corresponding upper limit to the mass-loss rates of

![]() .

.

In comparison, the LBVs HR Car and HD 160529 have

mass-loss rates of ![]()

![]()

![]() yr-1determined from radio observations, with HD 80077 and

HD 168607 an

yr-1determined from radio observations, with HD 80077 and

HD 168607 an ![]() order of magnitude lower

(Leitherer et al. 1995). Therefore, we conclude that the mass-loss

behavior of the Wd 1 population of B hypergiants is consistent with

expectations drawn from the wider Galactic population. No extended