| Issue |

A&A

Volume 510, February 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A87 | |

| Number of page(s) | 12 | |

| Section | Interstellar and circumstellar matter | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200913077 | |

| Published online | 16 February 2010 | |

CHAMP+ observations of warm gas in M 17 SW

J. P. Pérez-Beaupuits1 - M. Spaans1 - M. R. Hogerheijde2 - R. Güsten3 - A. Baryshev4 - W. Boland2,5

1 - Kapteyn Astronomical Institute, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, 9747

AV Groningen, The Netherlands

2 - Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, PO Box 9513, 2300 RA,

Leiden, The Netherlands

3 - Max-Planck-Institut für Radioastronomie, Auf dem Hügel 69, 53121

Bonn, Germany

4 - SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research , PO Box 800, 9700 AV

Groningen, The Netherlands

5 - Nederlandse Onderzoeksschool Voor Astronomie (NOVA), PO Box 9513,

2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands

Received 6 August 2009 / Accepted 26 October 2009

Abstract

Context. Sub-millimeter and Far-IR observations have

shown the presence of a significant amount of warm (few

hundred K) and dense (

![]() )

gas in sources ranging from active star-forming regions to the vicinity

of the Galactic center. Since the main cooling lines of the gas phase

are important tracers of the interstellar medium in Galactic and

extragalactic sources, proper and detailed understanding of their

emission and the ambient conditions of the emitting gas, is necessary

for a robust interpretation of the observations.

)

gas in sources ranging from active star-forming regions to the vicinity

of the Galactic center. Since the main cooling lines of the gas phase

are important tracers of the interstellar medium in Galactic and

extragalactic sources, proper and detailed understanding of their

emission and the ambient conditions of the emitting gas, is necessary

for a robust interpretation of the observations.

Aims. With high resolution (7''-9'') maps (![]()

![]() pc2)

of mid-J molecular lines we aim to probe the

physical conditions and spatial distribution of the warm (50 to several

hundred K) and dense gas (

pc2)

of mid-J molecular lines we aim to probe the

physical conditions and spatial distribution of the warm (50 to several

hundred K) and dense gas (

![]() )

across the interface region of the nearly edge-on M 17 SW

nebula.

)

across the interface region of the nearly edge-on M 17 SW

nebula.

Methods. We have used the dual color multiple pixel

receiver CHAMP+ on the APEX telescope to obtain

a

![]() map

of the

map

of the ![]() and

and ![]() transitions of 12CO, the 13CO

transitions of 12CO, the 13CO

![]() line,

and the

line,

and the

![]() 370

370 ![]() m

fine-structure transition of [C I] in M 17

SW. LTE and non-LTE radiative transfer models are used to constrain the

ambient conditions.

m

fine-structure transition of [C I] in M 17

SW. LTE and non-LTE radiative transfer models are used to constrain the

ambient conditions.

Results. The warm gas extends up to a distance of ![]() 2.2 pc

from the M 17 SW ridge. The 13CO

2.2 pc

from the M 17 SW ridge. The 13CO

![]() and [C I] 370

and [C I] 370 ![]() m lines have

a narrower spatial extent of about 1.3 pc along a strip line

at

m lines have

a narrower spatial extent of about 1.3 pc along a strip line

at ![]() .

The structure and distribution of the [C I]

.

The structure and distribution of the [C I]

![]() 370

370 ![]() m map

indicate that its emission arises from the interclump medium with

densities on the order of

m map

indicate that its emission arises from the interclump medium with

densities on the order of

![]() .

.

Conclusions. The warmest gas is located along the

ridge of the cloud, close to the ionization front. An LTE approximation

indicates that the excitation temperature of the embedded clumps

reaches ![]() 120 K.

The non-LTE model suggests that the kinetic temperature at four

selected positions cannot exceed 230 K in clumps of a density

of

120 K.

The non-LTE model suggests that the kinetic temperature at four

selected positions cannot exceed 230 K in clumps of a density

of

![]() and that

the warm (

and that

the warm (

![]() K) and dense (

K) and dense (

![]() )

gas traced by the mid-J 12CO lines

represents just about 2% of the bulk of the molecular gas. The clump

volume-filling factor ranges between 0.04 and 0.11 at these positions.

)

gas traced by the mid-J 12CO lines

represents just about 2% of the bulk of the molecular gas. The clump

volume-filling factor ranges between 0.04 and 0.11 at these positions.

Key words: ISM: general - ISM: atoms - ISM: molecules

1 Introduction

The heating and cooling balance in photon-dominated regions (PDRs)

remains an active study of research.

The comprehensive understanding of PDRs requires observations of large

areas close to radiation sources and of a wide wavelength range

covering various emissions of atoms, molecules, and grains.

In particular, mid-J CO lines have been

detected in almost all known massive Galactic star forming regions

(e.g. Orion Nebula, W51, Cepheus A, NGC 2024). This

indicates that warm (

![]() K) and dense (

K) and dense (

![]() )

gas is common and probably of importance in most OB star forming

regions. The mid-J CO lines detected in

regions like e.g. M 17, Cepheus A and W51 have

relatively narrow line widths of 5-10

)

gas is common and probably of importance in most OB star forming

regions. The mid-J CO lines detected in

regions like e.g. M 17, Cepheus A and W51 have

relatively narrow line widths of 5-10

![]() ,

although not as narrow as the line widths observed in cold quiescent

cloud cores.

,

although not as narrow as the line widths observed in cold quiescent

cloud cores.

Observations of the

![]() and

and

![]() transitions of 12CO in several massive

star forming regions indicate that the warm emitting gas is confined to

narrow (<1 pc) zones close to the ionization front.

These observations favor photoelectric heating of the warm gas by UV

radiation fields outside the HII regions (e.g. Harris et al. 1987; Graf

et al. 1993;

Yamamoto et al. 2001; Kramer

et al. 2004

and 2008).

Nevertheless, shocks may also be an important source of heating in high

velocity wing sources like Orion, W51 and W49 (Jaffe et al. 1987).

transitions of 12CO in several massive

star forming regions indicate that the warm emitting gas is confined to

narrow (<1 pc) zones close to the ionization front.

These observations favor photoelectric heating of the warm gas by UV

radiation fields outside the HII regions (e.g. Harris et al. 1987; Graf

et al. 1993;

Yamamoto et al. 2001; Kramer

et al. 2004

and 2008).

Nevertheless, shocks may also be an important source of heating in high

velocity wing sources like Orion, W51 and W49 (Jaffe et al. 1987).

Because of its nearly edge-on geometry and the large amount of observational data available in the literature, M 17 SW is one of the best Galactic regions to study the entire structure of PDRs from the exciting sources to the ionization front, and the succession (or not) of H2, [C I] and CO emissions, as predicted by PDR models (Icke et al. 1980; Felli et al. 1984; Meixner et al. 1992; Meijerink & Spaans 2005). M 17 SW is also one of the few star-forming regions for which the magnetic field strength can be measured in the PDR interface and where the structure of the neutral and molecular gas seems to be dominated by magnetic pressure rather than by gas pressure (Pellegrini et al. 2007).

M 17 SW is a giant molecular cloud at a distance

of 2.2 kpc,

illuminated by a highly obscured (

![]() mag) cluster of

several OB stars (among

mag) cluster of

several OB stars (among ![]() 100 stars)

at about 1 pc to the east (Beetz et al. 1976; Hanson

et al. 1997).

It also harbours a number of candidate young stellar objects that have

recently been found (Povich et al. 2009).

Several studies of molecular emission, excitation and line profiles

(e.g. Snell et al. 1984; Martin

et al. 1984;

Stutzki & Güsten 1990)

from the M 17 SW core indicate that the structure of the gas

is highly clumped rather than homogeneous.

Emission of [C I] and [C II] was

detected more than a parsec into

the molecular cloud along cuts through the interface region (Keene

et al. 1985;

Genzel et al. 1988;

Stutzki et al. 1988).

These results, as well as those found in other star-forming regions

like S106, the Orion Molecular Cloud, and the NGC 7023 Nebula

(e.g. Gerin & Phillips 1998;

Yamamoto et al. 2001;

Schneider et al. 2002,

2003;

Mookerjea et al. 2003)

do not agree with the atomic and molecular stratification predicted by

standard steady-state PDR models.

However, the extended [C I]

100 stars)

at about 1 pc to the east (Beetz et al. 1976; Hanson

et al. 1997).

It also harbours a number of candidate young stellar objects that have

recently been found (Povich et al. 2009).

Several studies of molecular emission, excitation and line profiles

(e.g. Snell et al. 1984; Martin

et al. 1984;

Stutzki & Güsten 1990)

from the M 17 SW core indicate that the structure of the gas

is highly clumped rather than homogeneous.

Emission of [C I] and [C II] was

detected more than a parsec into

the molecular cloud along cuts through the interface region (Keene

et al. 1985;

Genzel et al. 1988;

Stutzki et al. 1988).

These results, as well as those found in other star-forming regions

like S106, the Orion Molecular Cloud, and the NGC 7023 Nebula

(e.g. Gerin & Phillips 1998;

Yamamoto et al. 2001;

Schneider et al. 2002,

2003;

Mookerjea et al. 2003)

do not agree with the atomic and molecular stratification predicted by

standard steady-state PDR models.

However, the extended [C I]

![]() and

13CO

and

13CO

![]() emissions in S140 have been

successfully explained by a stationary but

clumpy PDR model (Spaans 1996; Spaans & van Dishoeck 1997).

Hence, the lack of stratification in [C I] ,

[C II] and CO is a result

that can be expected for inhomogeneous clouds, where each clump acts

as an individual PDR. On the other hand, a partial face-on illumination

of the molecular clouds would also suppress stratification.

emissions in S140 have been

successfully explained by a stationary but

clumpy PDR model (Spaans 1996; Spaans & van Dishoeck 1997).

Hence, the lack of stratification in [C I] ,

[C II] and CO is a result

that can be expected for inhomogeneous clouds, where each clump acts

as an individual PDR. On the other hand, a partial face-on illumination

of the molecular clouds would also suppress stratification.

Based on analysis of low-J lines of 12CO,

13CO and CH3CCH

data, the temperature towards the M 17 SW cloud core has been

estimated as 50-60 K, whereas the mean cloud temperature has

been found to be about 30-35 K

(e.g. Güsten & Fiebig 1988;

Bergin et al. 1994;

Wilson et al. 1999;

Howe et al. 2000;

Snell et al. 2000).

Temperatures of ![]() 275 K

have been estimated from NH3 observations

(Güsten & Fiebig 1988)

towards the VLA continuum arc, which agrees with estimates from highly

excited 12CO transitions (Harris

et al. 1987).

Multitransition CS and HC3N observations

indicate that the density at the core region

of M 17 SW is about

275 K

have been estimated from NH3 observations

(Güsten & Fiebig 1988)

towards the VLA continuum arc, which agrees with estimates from highly

excited 12CO transitions (Harris

et al. 1987).

Multitransition CS and HC3N observations

indicate that the density at the core region

of M 17 SW is about

![]() (e.g.,

Snell et al. 1984;

Wang et al. 1993;

Bergin et al. 1996).

On the other hand, densities up to

(e.g.,

Snell et al. 1984;

Wang et al. 1993;

Bergin et al. 1996).

On the other hand, densities up to

![]() have

been estimated towards the north rim with multitransition

observations of NH3, which indicates that

ammonia is coexistent with high density material traced in CS

and HCN (Güsten & Fiebig 1988).

The UV radiation field G0

has been estimated to be on the order of 104 in

units of the ambient interstellar radiation field (

have

been estimated towards the north rim with multitransition

observations of NH3, which indicates that

ammonia is coexistent with high density material traced in CS

and HCN (Güsten & Fiebig 1988).

The UV radiation field G0

has been estimated to be on the order of 104 in

units of the ambient interstellar radiation field (

![]() ,

Habing 1968;

Meixner et al. 1992).

,

Habing 1968;

Meixner et al. 1992).

However, most of the millimeter-wave molecular observations in

M 17 SW are sensitive only to low temperatures

(<100 K),

and the few available data of mid-J CO and

[C I] lines (consisting mostly of cuts across the

ionization front and observations at a few selected positions) are

limited in spatial resolution and extent (e.g. Harris et al. 1987; Stutzki

et al. 1988;

Genzel et al. 1988;

Stutzki & Güsten 1990;

Meixner et al. 1992;

Graf et al. 1993;

Howe et al. 2000).

Therefore, in this work we present maps (![]()

![]() pc2)

of mid-J molecular (12CO and 13CO

pc2)

of mid-J molecular (12CO and 13CO ![]() )

and atomic ([C I]

)

and atomic ([C I] ![]() )

gas with an excellent

high resolution (

9.4''-7.7''), which advances

existing work in M 17 SW.

)

gas with an excellent

high resolution (

9.4''-7.7''), which advances

existing work in M 17 SW.

The observations were done with CHAMP+

(Carbon Heterodyne Array of the MPIfR) on the Atacama Pathfinder

EXperiment (APEX![]() )

(Güsten et al. 2006).

The multiple pixels at two submm frequencies of CHAMP+ allow the

efficient mapping of

)

(Güsten et al. 2006).

The multiple pixels at two submm frequencies of CHAMP+ allow the

efficient mapping of ![]() arcmin

regions, and provide the ability to observe simultaneously the emission

from the

arcmin

regions, and provide the ability to observe simultaneously the emission

from the ![]() and

and ![]() rotational transitions of 12CO at 691.473 GHz

and 806.652 GHz, respectively.

We also observed the

rotational transitions of 12CO at 691.473 GHz

and 806.652 GHz, respectively.

We also observed the ![]() transition of 13CO at

661.067 GHz and the

transition of 13CO at

661.067 GHz and the

![]() 370

370 ![]() m

(hereafter:

m

(hereafter: ![]() )

fine-structure transition of

[C I] at 809.342 GHz.

)

fine-structure transition of

[C I] at 809.342 GHz.

Since the gas phase cools mainly via the atomic fine structure

lines of [O I] ![]() ,

[C II]

,

[C II] ![]() ,

[C I] and the rotational CO lines (e.g.

Kaufman et al. 1999;

Meijerink & Spaans 2005),

these carbon bearing species presented here are very important coolants

in the interstellar medium (ISM) of a variety of sources in the

Universe, from Galactic star forming regions, the Milky Way as a

galaxy, and external galaxies up to high redshifts (e.g. Fixsen

et al. 1999;

Weiss et al. 2003;

Kramer et al. 2005;

Bayet et al. 2006;

Jakob et al. 2007).

,

[C I] and the rotational CO lines (e.g.

Kaufman et al. 1999;

Meijerink & Spaans 2005),

these carbon bearing species presented here are very important coolants

in the interstellar medium (ISM) of a variety of sources in the

Universe, from Galactic star forming regions, the Milky Way as a

galaxy, and external galaxies up to high redshifts (e.g. Fixsen

et al. 1999;

Weiss et al. 2003;

Kramer et al. 2005;

Bayet et al. 2006;

Jakob et al. 2007).

The case of M 17 SW can be considered as a proxy for

extra galactic star forming regions. M 17 SW is not special,

nor does it need to be, compared to other

massive star-forming regions like Orion, W49, Cepheus A, or

W51. Still, it does allow

feedback effects, expected to be important for starburst and active

galaxies, to be

studied in great spatial detail. A comparison of the local line ratios

to

the extra-galactic regions can then shed light on the properties of

massive

star-forming regions that drive the energetics of active galaxies.

Our results will be of great use for future high resolution

observations, since molecular clouds of the size of the maps we present

will be resolved by ALMA at the distance (![]() 14 Mpc) of galaxies like

NGC 1068.

14 Mpc) of galaxies like

NGC 1068.

The main purpose of this work is to explore the actual spatial

distribution of the mid-J 12CO

and [C I] lines in M 17 SW and to test the

ambient conditions of the warm gas.

A simple LTE model based on the ratio between the 12CO and

13CO

![]() lines is used to

probe the temperature of the warm (

lines is used to

probe the temperature of the warm (

![]() K) and dense (

K) and dense (

![]() )

molecular gas.

Then a non-LTE model is used to test the ambient conditions at four

selected positions.

In a follow-up work we will present an elaborate model of these high

resolution data.

)

molecular gas.

Then a non-LTE model is used to test the ambient conditions at four

selected positions.

In a follow-up work we will present an elaborate model of these high

resolution data.

The most frequent references to Stutzki et al. (1988), Stutzki & Güsten (1990) and Meixner et al. (1992) will be cited as S88, SG90 and M92, respectively. The organization of this article is as follows. In Sect. 2 we describe the observations. The maps of the four lines observed are presented in Sect. 3. The modeling and analysis of the ambient conditions are presented in Sect. 4, and the conclusions and final remarks are presented in Sect. 5.

2 Observations

We have used the dual color heterodyne array receiver CHAMP+

(Kasemann et al. 2006;

Güsten et al. 2008),

providing ![]() pixels,

on the APEX telescope during July 2008 to map the

pixels,

on the APEX telescope during July 2008 to map the

![]() and

and

![]() lines of 12CO simultaneously, and - in

a second coverage - the 13CO

lines of 12CO simultaneously, and - in

a second coverage - the 13CO

![]() and [C I]

and [C I]

![]() .

We observed a region of about

.

We observed a region of about

![]() (3.4 pc

(3.4 pc

![]() 3.0 pc)

in on-the-fly (OTF) slews in RA (

3.0 pc)

in on-the-fly (OTF) slews in RA (![]() 320 arcsec

long), subsequent scans spaced by 4'' in declination.

The observations were done in total power mode, nodding the antenna

prior to each OTF slew to a reference position 180'' east of the SAO

star 161357. The latter is used as a reference throughout the paper,

with RA(J2000)=18:20:27.64 and Dec(J2000)=-16:12:00.90. We used

Sgr B2(N) as a reference for continuum poiting.

Calibration measurements were performed regularly every

320 arcsec

long), subsequent scans spaced by 4'' in declination.

The observations were done in total power mode, nodding the antenna

prior to each OTF slew to a reference position 180'' east of the SAO

star 161357. The latter is used as a reference throughout the paper,

with RA(J2000)=18:20:27.64 and Dec(J2000)=-16:12:00.90. We used

Sgr B2(N) as a reference for continuum poiting.

Calibration measurements were performed regularly every ![]() 10 min

with a cold liquid nitrogen (LN2) load and an ambient temperature load.

The data were processed with the APEX real-time calibration software

(Muders et al. 2006),

assuming an image sideband suppression of 10 dB.

10 min

with a cold liquid nitrogen (LN2) load and an ambient temperature load.

The data were processed with the APEX real-time calibration software

(Muders et al. 2006),

assuming an image sideband suppression of 10 dB.

We used the Fast Fourier Transform Spectrometer (FFTS) as

backend with a fixed bandwidth of 1.5 GHz

and 1024 channels. We used the two IF groups of the

FFTS with an offset of ![]() 460 MHz between them.

The spectral resolution was smoothed to about 1

460 MHz between them.

The spectral resolution was smoothed to about 1

![]() ,

while the line widths are between 4

,

while the line widths are between 4

![]() and 9

and 9

![]() ,

so they are well resolved.

The on-source integration time per dump and pixel

was 1 s only.

However, oversampling with 4'' spacing, all the seven pixels of CHAMP+

covered a given grid position at least once. So, after adding all the

subscans from both IF channels, and after convolving the maps with the

corresponding beam size, the total integration time in the central

,

so they are well resolved.

The on-source integration time per dump and pixel

was 1 s only.

However, oversampling with 4'' spacing, all the seven pixels of CHAMP+

covered a given grid position at least once. So, after adding all the

subscans from both IF channels, and after convolving the maps with the

corresponding beam size, the total integration time in the central

![]() region

of the maps varied between about 50 and 80 s

per grid cell.

region

of the maps varied between about 50 and 80 s

per grid cell.

The SSB system temperatures are typically

about 2000 K and 6000 K

respectively for the low and high frequency bands. The spatial

resolution varies between 9.4'' for the 13CO

![]() transition

in the low frequency band (at 661 GHz - the nominal beam at

691 GHz is 8.4'') and 7.7'' for the high frequency band

(809 GHz).

All data in the paper were converted to the line brightness temperature

transition

in the low frequency band (at 661 GHz - the nominal beam at

691 GHz is 8.4'') and 7.7'' for the high frequency band

(809 GHz).

All data in the paper were converted to the line brightness temperature

![]() ,

using a forward efficiency (

,

using a forward efficiency (

![]() )

of 0.95 and beam coupling efficiencies (

)

of 0.95 and beam coupling efficiencies (

![]() )

of 0.45 and 0.43 (at 661 GHz and 809 GHz,

respectively) as determined towards Jupiter

)

of 0.45 and 0.43 (at 661 GHz and 809 GHz,

respectively) as determined towards Jupiter![]() (Güsten et al. 2008).

We assumed brightness temperatures of 150 K (at

660 GHz) and 145 (at 815 GHz) for Jupiter (Griffin

et al. 1986).

This coupling efficiency was chosen because in velocity-space (velocity

channels) the size of the M 17 clumps is Jupiter-like, which

had a size

(Güsten et al. 2008).

We assumed brightness temperatures of 150 K (at

660 GHz) and 145 (at 815 GHz) for Jupiter (Griffin

et al. 1986).

This coupling efficiency was chosen because in velocity-space (velocity

channels) the size of the M 17 clumps is Jupiter-like, which

had a size ![]() 38.7''

at the time of the observations.

The calibrated data were reduced with the GILDAS

38.7''

at the time of the observations.

The calibrated data were reduced with the GILDAS![]() package CLASS90.

package CLASS90.

3 Results

3.1 Integrated line temperature maps

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13077f1a-cmjn.eps}\par\vspace*{2mm} \includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13077f1b-cmjn.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13077-09/Timg63.png)

|

Figure 1:

Top - Color map of the integrated temperature

of 12CO

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13077f2a-cmjn.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13077-09/Timg64.png)

|

Figure 2:

Color map of the 21 cm continuum emission (Jy beam-1)

in M 17 SW with a

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{13077f3a-cmjn.eps}\par\vspace*{2mm}

\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{13077f3b-cmjn.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13077-09/Timg65.png)

|

Figure 3:

Top panel - strip lines of the velocity

integrated intensities of 12CO J=7-6

(black), 12CO J=6-5

(red), 12CO J=2-1

(green) (adapted from S88), 13CO J=6-5

(blue) and [C I] J=2-1 (cyan) at

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Figure 1

shows the maps of the temperatures, integrated between 5

![]() and 35

and 35

![]() ,

of

12CO

,

of

12CO

![]() (top) with

the contour lines of 12CO

(top) with

the contour lines of 12CO

![]() ,

and the velocity integrated temperature of 13CO

,

and the velocity integrated temperature of 13CO

![]() (bottom)

with the contour lines corresponding to [C I]

(bottom)

with the contour lines corresponding to [C I]

![]() .

All the maps were convolved to the largest beam size (9.4'') of the

13CO

.

All the maps were convolved to the largest beam size (9.4'') of the

13CO

![]() line, obtaining a grid size of

about

line, obtaining a grid size of

about ![]() .

The peak

integrated temperatures of the 12CO

.

The peak

integrated temperatures of the 12CO

![]() and

and

![]() lines

are 852 K

lines

are 852 K

![]() and 925 K

and 925 K

![]() respectively. These lines follow a similar spatial distribution.

The peak integrated temperatures of 13CO

respectively. These lines follow a similar spatial distribution.

The peak integrated temperatures of 13CO

![]() and

[C I]

and

[C I]

![]() are 420 K

and 282 K.

respectively, and the peak of [C I] is shifted

towards the inner side of the interface region at

about 0.55 pc (

are 420 K

and 282 K.

respectively, and the peak of [C I] is shifted

towards the inner side of the interface region at

about 0.55 pc (![]() 50'').

The ionization front traced by the high resolution (

50'').

The ionization front traced by the high resolution (

![]() )

map of the 21 cm continuum emission (Brogan & Troland 2001) as well as

the ionizing stars identified by Beetz et al. (1976) and Hanson

et al. (1997)

are shown in Fig. 2,

with 12CO

)

map of the 21 cm continuum emission (Brogan & Troland 2001) as well as

the ionizing stars identified by Beetz et al. (1976) and Hanson

et al. (1997)

are shown in Fig. 2,

with 12CO

![]() (white contour lines) and

[C I]

(white contour lines) and

[C I]

![]() (green contour lines)

overlaid. The transition between the hot (

(green contour lines)

overlaid. The transition between the hot (

![]() K) atomic gas and

the warm (

K) atomic gas and

the warm (

![]() K) molecular gas can

be seen due to the almost edge-on geometry of M 17 SW.

K) molecular gas can

be seen due to the almost edge-on geometry of M 17 SW.

The top panel of Fig. 3 shows the

variation of the integrated temperature of all the lines across the

ionization front (strip line at

![]() in

Fig. 1).

Due to the limited S/N the 12CO

in

Fig. 1).

Due to the limited S/N the 12CO

![]() and [C I]

and [C I]

![]() strip lines have been smoothed

spatially with respect to the strip

direction.

The [C I]

strip lines have been smoothed

spatially with respect to the strip

direction.

The [C I]

![]() line

starts peaking up at about 0.1 pc (

line

starts peaking up at about 0.1 pc (![]() 10'') after

the molecular lines and presents a smooth transition towards the inner

part of the cloud, forming a plateau at about

10'') after

the molecular lines and presents a smooth transition towards the inner

part of the cloud, forming a plateau at about

![]() ,

from where it increases its emission until the peak is reached at about

,

from where it increases its emission until the peak is reached at about

![]() .

The peak of [C I] correlates with a secondary peak

seen in 13CO. However, the main peak emission

of the latter correlates with the peak of the 12CO

lines along this strip line.

.

The peak of [C I] correlates with a secondary peak

seen in 13CO. However, the main peak emission

of the latter correlates with the peak of the 12CO

lines along this strip line.

The strip line at

![]() (bottom

panel of Fig. 3) can be

compared with Fig. 5 in M92, and Fig. 2 in S88. At

this position angle, there is no marked plateau in the

[C I] emission, and the peak of the

[C I] line is closer to the peaks of the 12CO

and 13CO lines. The dip in 12CO

(bottom

panel of Fig. 3) can be

compared with Fig. 5 in M92, and Fig. 2 in S88. At

this position angle, there is no marked plateau in the

[C I] emission, and the peak of the

[C I] line is closer to the peaks of the 12CO

and 13CO lines. The dip in 12CO

![]() at

about

at

about ![]() is an artifact.

The integrated temperature of the 12CO

is an artifact.

The integrated temperature of the 12CO

![]() ,

,

![]() and

and

![]() lines have a comparable strength deep (

lines have a comparable strength deep (

![]() )

into the M 17 SW complex.

)

into the M 17 SW complex.

3.2 The complex internal structure of M 17 SW

Figure 4

shows the spectra at selected positions along the NE-SW strip

line at PA

![]() .

The main-beam temperature of the spectra is shifted

by 70 K at each offset position.

This set of spectra can be compared with the 12CO

and C18O

.

The main-beam temperature of the spectra is shifted

by 70 K at each offset position.

This set of spectra can be compared with the 12CO

and C18O

![]() spectra along the same strip

line of Fig. 8 in S88. The warm

gas (

spectra along the same strip

line of Fig. 8 in S88. The warm

gas (

![]() K), traced by the

mid-J 12CO lines,

is as extended as the cold gas (

K), traced by the

mid-J 12CO lines,

is as extended as the cold gas (

![]() K) traced by the 12CO

K) traced by the 12CO

![]() line

deeper into the cloud. On the other hand, the 13CO

line

deeper into the cloud. On the other hand, the 13CO

![]() and [C I]

and [C I]

![]() lines

are strongly detected in a narrower spatial extent of about

1.3 pc, similar to the extent of the C18O

lines

are strongly detected in a narrower spatial extent of about

1.3 pc, similar to the extent of the C18O

![]() emission.

emission.

![\begin{figure}

\par\mbox{\includegraphics[height=14cm,angle=0]{13077f4a.eps}\hsp...

...ce{-0.2cm}

\includegraphics[height=14cm,angle=0]{13077f4d.eps} }

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13077-09/Timg73.png)

|

Figure 4:

Selected spectra of 12CO

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Multilevel molecular line observations in CS, 12CO,

13CO and C18O

and in several fine structure lines ([C I], [C II],

[Si II], [O I]) indicate that M 17 SW

consists of numerous high density clumps (

![]() )

from which the [O I], [Si II] and mid-J

CO lines emanate. This dense gas is found within a relatively

warm (

)

from which the [O I], [Si II] and mid-J

CO lines emanate. This dense gas is found within a relatively

warm (![]() 50 K)

and less dense (

50 K)

and less dense (

![]() )

molecular gas (interclump medium), which in turn is surrounded by a

diffuse halo (

)

molecular gas (interclump medium), which in turn is surrounded by a

diffuse halo (

![]() )

which is the source of the very extended [C I] and

[C II] emission (Snell et al. 1984, 1986; Evans

et al. 1987;

S88; SG90; M92).

)

which is the source of the very extended [C I] and

[C II] emission (Snell et al. 1984, 1986; Evans

et al. 1987;

S88; SG90; M92).

From the C18O observations in

M 17 SW a beam-averaged (13'') column density of ![]()

![]() has

been estimated for the cloud core and masses in the range

has

been estimated for the cloud core and masses in the range ![]()

![]() for the CO clumps

(SG90). A comparable mass range (

for the CO clumps

(SG90). A comparable mass range (![]()

![]() )

was lately estimated from submillimeter continuum observations in the

northern part of M 17 (Reid & Wilson 2006), although

the region mapped by Reid & Wilson (2006) adjoins, but

does not overlap with M 17 SW.

)

was lately estimated from submillimeter continuum observations in the

northern part of M 17 (Reid & Wilson 2006), although

the region mapped by Reid & Wilson (2006) adjoins, but

does not overlap with M 17 SW.

Figure 5

shows representative velocity channel maps of the 12CO

![]() (top

left) and

(top

left) and ![]() (top right) lines in M 17 SW. These are the

main-beam brightness temperatures averaged over two and three velocity

channels between 18.2

(top right) lines in M 17 SW. These are the

main-beam brightness temperatures averaged over two and three velocity

channels between 18.2

![]() and 19.9

and 19.9

![]() .

These are similar to the velocity channels shown in Fig. 3 by

SG90. The fact that the C18O

.

These are similar to the velocity channels shown in Fig. 3 by

SG90. The fact that the C18O

![]() line traces colder (

line traces colder (

![]() K) and less dense (

K) and less dense (

![]() )

gas than the 12CO lines is reflected

in the different velocity integrated maps (Fig. 1) and in the

channel maps of these lines. In theory the critical densities (at

)

gas than the 12CO lines is reflected

in the different velocity integrated maps (Fig. 1) and in the

channel maps of these lines. In theory the critical densities (at

![]() K)

of the 12CO

K)

of the 12CO

![]() and

and

![]() lines

are

lines

are

![]() and

and

![]() ,

respectively, which corresponds to a difference of a factor

,

respectively, which corresponds to a difference of a factor ![]() 1.6.

However, this difference is not directly translated into a different

clumpyness. This is reflected in the similar clumpy structure seen in

the channel maps of these mid-J 12CO lines.

1.6.

However, this difference is not directly translated into a different

clumpyness. This is reflected in the similar clumpy structure seen in

the channel maps of these mid-J 12CO lines.

Even though the critical density of the 13CO

![]() line

is similar to that of the 12CO (

line

is similar to that of the 12CO (

![]() )

the south-east region of its channel map (bottom left)

differs from that seen with the 12CO lines.

This could be due to a change in the temperature of the gas, or to a

variation in the 13CO column density

in that region. Since 13CO is much

more optically thin than 12CO (abundance

ratio of about 50-70), this difference in the map can be expected. In

Sects. 4.2 and 4.3 we discuss the optical depths.

)

the south-east region of its channel map (bottom left)

differs from that seen with the 12CO lines.

This could be due to a change in the temperature of the gas, or to a

variation in the 13CO column density

in that region. Since 13CO is much

more optically thin than 12CO (abundance

ratio of about 50-70), this difference in the map can be expected. In

Sects. 4.2 and 4.3 we discuss the optical depths.

On the other hand, the [C I]

![]() channel map (bottom

right) shows a completely

different structure and distribution than the 12CO and

the isotope lines. Since the critical density of this line is about

channel map (bottom

right) shows a completely

different structure and distribution than the 12CO and

the isotope lines. Since the critical density of this line is about

![]() ,

its emission is likely emerging partly from the interclump medium

mentioned above.

,

its emission is likely emerging partly from the interclump medium

mentioned above.

![\begin{figure}

\par\mbox{\includegraphics[width=4.1cm]{13077f5a-cmjn.eps} \hspac...

...\hspace*{6mm}\includegraphics[width=4.1cm]{13077f5d-cmjn.eps} }

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13077-09/Timg87.png)

|

Figure 5:

Top panel - Channel maps of the main-beam

brightness temperature of 12CO

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

4 Discussion

4.1 Self-absorption in the mid-J 12CO lines?

The complex structure of the 12CO

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and

,

and ![]() line profiles has been attributed to strong self-absorption effects

(e.g. Rainey et al. 1987;

Stutzki et al. 1988).

Martin et al. (1984)

also reported a flat topped spectrum of 12CO

line profiles has been attributed to strong self-absorption effects

(e.g. Rainey et al. 1987;

Stutzki et al. 1988).

Martin et al. (1984)

also reported a flat topped spectrum of 12CO

![]() ,

attributed to self-absorption or saturation at velocities near the line

center and gave details about the effects of macroturbulent clumpy

medium in the line profiles.

,

attributed to self-absorption or saturation at velocities near the line

center and gave details about the effects of macroturbulent clumpy

medium in the line profiles.

A double peaked structure in the 13CO

![]() line

was also reported by Lada (1976).

Rainey et al. considered that this double peaked structure in 13CO suggests

that either this line is optically thick or that the double peaked

structure is due to more than one cloud component. The latter is the

interpretation favored by Rainey et al. in view of the

available data at that time.

line

was also reported by Lada (1976).

Rainey et al. considered that this double peaked structure in 13CO suggests

that either this line is optically thick or that the double peaked

structure is due to more than one cloud component. The latter is the

interpretation favored by Rainey et al. in view of the

available data at that time.

Phillips et al. (1981)

presented a self-absorption LTE model that considers a 12CO

cloud of uniform temperature ![]() in front of a hot background source of a temperature

in front of a hot background source of a temperature

![]() ,

at the same central velocity. The velocity dispersion of the background

cloud is considered to be larger than that of the foreground cloud,

so the self-absorption effect is seen mostly at the line center.

This model indicates that, depending on the total column density of 12CO,

the self-absorption effect will be stronger in the

,

at the same central velocity. The velocity dispersion of the background

cloud is considered to be larger than that of the foreground cloud,

so the self-absorption effect is seen mostly at the line center.

This model indicates that, depending on the total column density of 12CO,

the self-absorption effect will be stronger in the

![]() and

and

![]() lines than in the

lines than in the ![]() line, with decreasing intensity as the transition number J

increases. This is indeed observed in Fig. 12 of S88

for the 12CO

line, with decreasing intensity as the transition number J

increases. This is indeed observed in Fig. 12 of S88

for the 12CO

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

and

,

and ![]() lines.

lines.

We reproduced the model by Phillips et al.

including the higher-J lines of 12CO.

The top panel of Fig. 6 shows

the model with the same background and foreground temperatures used by

Phillips et al.This model implies that, for a background

temperature ![]() K

and a foreground kinetic temperature

K

and a foreground kinetic temperature

![]() K,

the lower-J lines (J=1, 2, 3, 4)

of the background cloud start showing self-absorption at the line

center for lower column densities (

K,

the lower-J lines (J=1, 2, 3, 4)

of the background cloud start showing self-absorption at the line

center for lower column densities (

![]() cm-2 km s-1).

Instead, the higher-J lines (J=5, 6, 7) need larger

columns (

cm-2 km s-1).

Instead, the higher-J lines (J=5, 6, 7) need larger

columns (

![]() cm-2 km s-1)

in order to be affected by self-absorption. For a velocity dispersion

of

cm-2 km s-1)

in order to be affected by self-absorption. For a velocity dispersion

of ![]()

![]() ,

the upper limits of these 12CO

columns would correspond to extinctions

,

the upper limits of these 12CO

columns would correspond to extinctions ![]() of

of ![]() 0.1 mag

and

0.1 mag

and ![]() 10 mag,

respectively.

10 mag,

respectively.

The bottom panel of of Fig. 6 shows

the model for a background temperature

![]() K

and a foreground temperature

K

and a foreground temperature ![]() K

(from S88). In this case the lower-J lines show

self-absorption at the same range of columns as before, while the

higher-J lines start showing self-absorption at a

narrower range of columns (

K

(from S88). In this case the lower-J lines show

self-absorption at the same range of columns as before, while the

higher-J lines start showing self-absorption at a

narrower range of columns (

![]() cm-2 km s-1).

A remarkable characteristic of these models (top and bottom panels of

Fig. 6)

is that all the J lines are expected to be strongly

self-absorbed at columns larger than 1018 cm-2 km s-1,

which is similar to the column density estimated by S88. Another

characteristic is that the 12CO emission

of the higher-J lines are also expected to decrease

with the transition number J, and be weaker than

the low-J lines. However, the 12CO

cm-2 km s-1).

A remarkable characteristic of these models (top and bottom panels of

Fig. 6)

is that all the J lines are expected to be strongly

self-absorbed at columns larger than 1018 cm-2 km s-1,

which is similar to the column density estimated by S88. Another

characteristic is that the 12CO emission

of the higher-J lines are also expected to decrease

with the transition number J, and be weaker than

the low-J lines. However, the 12CO

![]() line

seems to break this rule, as can be seen in Fig. 12 of S88.

The high peak temperature observed in the 12CO

line

seems to break this rule, as can be seen in Fig. 12 of S88.

The high peak temperature observed in the 12CO

![]() line

is missing in the lower-J lines. Even considering a

calibration uncertainty of 20%, the 12CO

line

is missing in the lower-J lines. Even considering a

calibration uncertainty of 20%, the 12CO

![]() line

(observed at offset position

(-100'',0''), bottom panel of Fig. 12 in S88) will be as

strong as the

line

(observed at offset position

(-100'',0''), bottom panel of Fig. 12 in S88) will be as

strong as the ![]() line (at least at the peak intensity) but still stronger than the

line (at least at the peak intensity) but still stronger than the

![]() line.

line.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7cm]{13077f6a-cmjn.eps}\par\vspace{2mm}

\includegraphics[width=7cm]{13077f6b-cmjn.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13077-09/Timg99.png)

|

Figure 6:

Top panel - expected brightness temperature at

the center of the 12CO lines for a

warm background cloud with a temperature

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

On the other hand, the 12CO

![]() line seems to be asymmetric,

with a left shoulder

weaker than the

right shoulder, which may be due to self-absorption

produced by a colder foreground cloud with slightly lower center

velocity than the warmer clump traced by the

line seems to be asymmetric,

with a left shoulder

weaker than the

right shoulder, which may be due to self-absorption

produced by a colder foreground cloud with slightly lower center

velocity than the warmer clump traced by the

![]() line.

However, that weaker left shoulder of the mid-J

line is still brighter than the corresponding shoulder of the

lower-J lines, in most of the velocity range and in

both positions (-100'',0'')

and (-60'',-30'') - assuming

a low (<10%) uncertainty in the calibration of the data. This is

not what would be expected in the self-absorption scenario proposed by

Phillips et al. (1981).

line.

However, that weaker left shoulder of the mid-J

line is still brighter than the corresponding shoulder of the

lower-J lines, in most of the velocity range and in

both positions (-100'',0'')

and (-60'',-30'') - assuming

a low (<10%) uncertainty in the calibration of the data. This is

not what would be expected in the self-absorption scenario proposed by

Phillips et al. (1981).

Figure 4

shows that the 13CO

![]() line has a similar asymmetry

as the 12CO lines,

at positions (-45'',-23'')

and (-60'',-30''). But it

shows only one component

at the other positions. This difference may be related to a gradient in

the temperature (or total column density) of the foreground cloud that

produces self-absorption in the first two positions, but not in the

others.

Instead, [C I]

line has a similar asymmetry

as the 12CO lines,

at positions (-45'',-23'')

and (-60'',-30''). But it

shows only one component

at the other positions. This difference may be related to a gradient in

the temperature (or total column density) of the foreground cloud that

produces self-absorption in the first two positions, but not in the

others.

Instead, [C I]

![]() shows

similar asymmetry as 12CO at

positions (-45'',-23''),

(-150'',-75'') and

(-180'',-90''), and an opposite asymmetry at position

(-75'',-38''). Given that there is no strong evidence for

self-absorption in neither the 13CO

lines nor in the [C I] lines and that the 13CO lines

are mostly optically thin, it is unlikely that the observed asymmetries

of the 13CO and

[C I] lines are produced by self-absorption. Hence,

we agree with Rainey et al. (1987) in that

this complex structure is more likely due to more than one kinematical

component along the line of sight. And this could also be the case for

the mid-J 12CO lines.

shows

similar asymmetry as 12CO at

positions (-45'',-23''),

(-150'',-75'') and

(-180'',-90''), and an opposite asymmetry at position

(-75'',-38''). Given that there is no strong evidence for

self-absorption in neither the 13CO

lines nor in the [C I] lines and that the 13CO lines

are mostly optically thin, it is unlikely that the observed asymmetries

of the 13CO and

[C I] lines are produced by self-absorption. Hence,

we agree with Rainey et al. (1987) in that

this complex structure is more likely due to more than one kinematical

component along the line of sight. And this could also be the case for

the mid-J 12CO lines.

Therefore, the observational facts and the models suggest that

the self absorption effect, if present, should have little impact on

the mid-J lines, and a few cloud components at

different central velocities could also explain the complex structure

of the line profiles. The asymmetry of the profiles suggests that

self-absorption affects mostly one wing of the line profile, while the

peak temperatures seems to be the least affected velocity channel in

the mid-J lines.

Hence, in the following sections we test the ambient conditions of the

warm gas based on the ratios between the peak main-beam temperatures of

the 12CO and 13CO

![]() and

and

![]() lines.

lines.

4.2 Optical depth and excitation temperature (LTE)

Since we have the maps of the 12CO and

the 13CO

![]() lines, we can estimate the

optical depth and the excitation temperature

of these lines, assuming local thermal equilibrium (LTE), from the

ratio between their peak main-beam temperature

lines, we can estimate the

optical depth and the excitation temperature

of these lines, assuming local thermal equilibrium (LTE), from the

ratio between their peak main-beam temperature

![]() observed

between the 5

observed

between the 5

![]() and 35

and 35

![]() velocity channels. This will

provide at least a lower limit for the kinetic temperature in

M 17 SW. Then we will estimate the ambient conditions at two

selected positions based on a non-LTE model of the ratio between the

peak

velocity channels. This will

provide at least a lower limit for the kinetic temperature in

M 17 SW. Then we will estimate the ambient conditions at two

selected positions based on a non-LTE model of the ratio between the

peak ![]() temperatures of the 12CO

temperatures of the 12CO

![]() and

and

![]() lines

(hereafter referred as 12CO

lines

(hereafter referred as 12CO

![]() line ratio). The temperature

and densities obtained in this way will be

compared to those values estimated in previous work.

line ratio). The temperature

and densities obtained in this way will be

compared to those values estimated in previous work.

In LTE the radiation temperature can be approximated

(e.g. Kutner 1984;

Bergin et al. 1994)

by the expression:

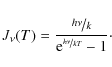

![\begin{displaymath}T_{\rm R}=[J_{\nu}(T_{\rm ex})-J_{\rm bg}][1-{\rm e}^{-\tau_{\nu}}] ,

\end{displaymath}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13077-09/img101.png)

|

(1) |

where the term

|

(2) |

We use the full

The background radiation

![]() is a

composite between the cosmic microwave background radiation (CMB),

as a blackbody function at 2.73 K, and the diluted

infrared radiation remitted by dust. That is:

is a

composite between the cosmic microwave background radiation (CMB),

as a blackbody function at 2.73 K, and the diluted

infrared radiation remitted by dust. That is:

|

(3) |

where

For extended (resolved) sources like the clumps in

M 17 SW, the radiation temperature is well estimated by the

observed main-beam brightness temperature

![]() .

Hence, we use that quantity in the following analysis. From the LTE

approximation we can assume that the excitation temperatures

.

Hence, we use that quantity in the following analysis. From the LTE

approximation we can assume that the excitation temperatures

![]() of 12CO and

13CO

of 12CO and

13CO

![]() are

the same, although the terms

are

the same, although the terms

![]() are

not exactly the same because of the slightly (

are

not exactly the same because of the slightly (![]() 4%)

different frequencies of the 12CO and 13CO lines.

So, from Eq. (1) the ratio between 12CO and

13CO can be approximated as:

4%)

different frequencies of the 12CO and 13CO lines.

So, from Eq. (1) the ratio between 12CO and

13CO can be approximated as:

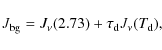

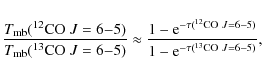

|

(4) |

Following the work by Wilson et al. (1999), we adopt a constant [12CO /13CO

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13077f7a-cmjn.eps}\par\vspace*{2mm}

\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13077f7b-cmjn.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13077-09/Timg119.png)

|

Figure 7:

LTE approximation of the optical depth (top) of the 13CO

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

The top panel in Fig. 7 shows the

![]() map.

The 13CO

line is optically thin in most of the region, with some optically thick

spots (e.g.,

map.

The 13CO

line is optically thin in most of the region, with some optically thick

spots (e.g.,

![]() ). Knowing

). Knowing

![]() we can estimate

we can estimate ![]() from Eq. (2) using either tracer, considering that the

from Eq. (2) using either tracer, considering that the

![]() estimated

using 12CO is just

estimated

using 12CO is just ![]() 0.6% higher

than that estimated using 13CO. The

0.6% higher

than that estimated using 13CO. The

![]() map is shown

in the bottom panel of Fig. 7. This map

indicates

that the warmest gas is located along the ridge of the cloud, close to

the ionization front.

The temperature in this region ranges between 40

and 120 K, and the peak temperature is located at

around (

map is shown

in the bottom panel of Fig. 7. This map

indicates

that the warmest gas is located along the ridge of the cloud, close to

the ionization front.

The temperature in this region ranges between 40

and 120 K, and the peak temperature is located at

around (

![]() ).

If we consider only the gas with temperatures

).

If we consider only the gas with temperatures ![]() 80 K,

the warm gas would be confined to a zone of

about 40'' (

80 K,

the warm gas would be confined to a zone of

about 40'' (![]() 0.44 pc) next to, and along, the HII

region, which agrees with previous results found by Graf

et al. (1993).

If the gas were thermalized, this could be the actual

map of the kinetic temperature of the gas. Otherwise, the

0.44 pc) next to, and along, the HII

region, which agrees with previous results found by Graf

et al. (1993).

If the gas were thermalized, this could be the actual

map of the kinetic temperature of the gas. Otherwise, the

![]() map can be

considered as a lower limit of

map can be

considered as a lower limit of ![]() .

Since in velocity space the clumps cover the whole beam, this would

imply that the 12CO and 13CO molecules

are subthermal in the

.

Since in velocity space the clumps cover the whole beam, this would

imply that the 12CO and 13CO molecules

are subthermal in the ![]() transition. That is, the density of the gas and the column density of 12CO and

13CO may be insufficient to thermalize

these transitions. A more detailed analysis is presented in the next

section.

transition. That is, the density of the gas and the column density of 12CO and

13CO may be insufficient to thermalize

these transitions. A more detailed analysis is presented in the next

section.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm]{13077f8a-cmjn.eps}\par\vspace*{1m...

...\par\vspace*{1mm}

\includegraphics[width=8cm]{13077f8d-cmjn.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13077-09/Timg123.png)

|

Figure 8:

Top - spectra of the four lines observed in

M 17 SW at position A (

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

4.3 Ambient condition at selected positions (non-LTE)

Figure 8

shows the spectra of all the observed lines extracted at four different

positions in the map. The top panel shows the

spectra observed at position A (

![]() ),

close to the peak emission of the 12CO lines.

All the lines show a double component structure with the secondary

component peaking at

),

close to the peak emission of the 12CO lines.

All the lines show a double component structure with the secondary

component peaking at ![]() 25

25

![]() .

The middle top panel shows the spectra at

position B (

.

The middle top panel shows the spectra at

position B (

![]() ),

where the velocity-integrated temperature corresponds to

about 50% of the peak emission. Here only the 12CO

),

where the velocity-integrated temperature corresponds to

about 50% of the peak emission. Here only the 12CO

![]() line

seems to have a dip at the line center. However, because of the low S/N

in the high frequency band, this dip may be likely due to noise.

The middle bottom panel shows the spectra at

position C (

line

seems to have a dip at the line center. However, because of the low S/N

in the high frequency band, this dip may be likely due to noise.

The middle bottom panel shows the spectra at

position C (

![]() ),

which corresponds to the peak of the NE-SW strip scan reported in S88

and Graf et al. (1993),

with beams of 40'' and 8'', respectively. The bottom panel

shows the spectra at position D (

),

which corresponds to the peak of the NE-SW strip scan reported in S88

and Graf et al. (1993),

with beams of 40'' and 8'', respectively. The bottom panel

shows the spectra at position D (

![]() ), which is

close to the continuum far-IR peak, also reported in S88.

Since we do not have dedicated observations at these positions, we

extracted the spectra from the nearest pixels in our maps, convolved to

the largest beam (9.4'') of the 13CO

), which is

close to the continuum far-IR peak, also reported in S88.

Since we do not have dedicated observations at these positions, we

extracted the spectra from the nearest pixels in our maps, convolved to

the largest beam (9.4'') of the 13CO

![]() line. So the spectra shown in

Fig. 8

are the

convolved spectra centered within

line. So the spectra shown in

Fig. 8

are the

convolved spectra centered within ![]() 1'' of the indicated coordinates. This is

justified because we have oversampled data.

1'' of the indicated coordinates. This is

justified because we have oversampled data.

Table 1

shows the Gaussian fits of the spectra obtained at the four selected

positions. Two Gaussian components were needed to fit the lines, except

at position B, where only one component was used. The main

components of the 12CO lines have a

line width that is about 8-9

![]() at position A, while the 13CO has

a

line width of about 3

at position A, while the 13CO has

a

line width of about 3

![]() narrower. The

[C I] line is the narrowest line, with

a line width of

narrower. The

[C I] line is the narrowest line, with

a line width of ![]() 4

4

![]() .

At position B, the 12CO lines

are the widest of the four lines with about 8

.

At position B, the 12CO lines

are the widest of the four lines with about 8

![]() and the 13CO and

[C I] lines have about half the line width of the 12CO lines.

At position C and D the Gaussian parameters of the 12CO

and the 13CO and

[C I] lines have about half the line width of the 12CO lines.

At position C and D the Gaussian parameters of the 12CO

![]() presented

uncertainties of

presented

uncertainties of ![]()

![]() when let free in the fitting. However, because the line shape of the 12CO

when let free in the fitting. However, because the line shape of the 12CO

![]() and

and

![]() transitions are very similar, we set the line width of the

transitions are very similar, we set the line width of the

![]() transition

to the value found for the

transition

to the value found for the

![]() line.

The line width of the main components of the 12CO lines

at position C and D are

line.

The line width of the main components of the 12CO lines

at position C and D are ![]() 6

6

![]() ,

that is about 2

,

that is about 2

![]() narrower than the lines

observed at positions A

and B. This difference can be due to a higher optical depth

towards the latter positions or to the contribution of a few

fast-moving cloudlets (Martin et al. 1984; Graf

et al. 1993).

narrower than the lines

observed at positions A

and B. This difference can be due to a higher optical depth

towards the latter positions or to the contribution of a few

fast-moving cloudlets (Martin et al. 1984; Graf

et al. 1993).

The 12CO

![]() line ratio between the peak

main-beam temperatures

line ratio between the peak

main-beam temperatures ![]() obtained from the Gaussian fit of the main components is

obtained from the Gaussian fit of the main components is

![]() at

position A,

at

position A, ![]() at position B,

at position B, ![]() at position C, and

at position C, and ![]() at position D.

From these line ratios we can estimate the ambient conditions for these

particular positions. We have used the non-LTE radiative transfer code

RADEX

at position D.

From these line ratios we can estimate the ambient conditions for these

particular positions. We have used the non-LTE radiative transfer code

RADEX![]() (Van der Tak et al. 2007) to estimate

the average ambient conditions (kinetic temperature, density and column

density) of the molecular gas. We assumed collisional excitation by

molecular hydrogen. We also assumed an homogeneous spherical symmetry

in the clumps for the escape-probability formalism. The collision rates

between 12CO and ortho- and para-H2

are taken from Wernli et al. (2006), and can

be found in the LAMDA database (Schöier et al. 2005).

As in the LTE case, we used the cosmic microwave background radiation

at 2.73 K, and we also tested the non-LTE model with and

without the infrared radiation remitted by dust (Eq. (3)) as

the background source. It was found also for this case that the dust

continuum emission produces a negligible effect in the non-LTE model at

the frequencies of the 12CO

(Van der Tak et al. 2007) to estimate

the average ambient conditions (kinetic temperature, density and column

density) of the molecular gas. We assumed collisional excitation by

molecular hydrogen. We also assumed an homogeneous spherical symmetry

in the clumps for the escape-probability formalism. The collision rates

between 12CO and ortho- and para-H2

are taken from Wernli et al. (2006), and can

be found in the LAMDA database (Schöier et al. 2005).

As in the LTE case, we used the cosmic microwave background radiation

at 2.73 K, and we also tested the non-LTE model with and

without the infrared radiation remitted by dust (Eq. (3)) as

the background source. It was found also for this case that the dust

continuum emission produces a negligible effect in the non-LTE model at

the frequencies of the 12CO

![]() and

and

![]() lines.

We explored molecular hydrogen densities between

lines.

We explored molecular hydrogen densities between

![]() and

and

![]() ,

temperatures between 5 K and 500 K, and 12CO column

densities between

,

temperatures between 5 K and 500 K, and 12CO column

densities between ![]() and

and ![]() .

.

Figure 9

shows the possible ambient conditions required to reproduce the 12CO

![]() line

ratios, and the peak

line

ratios, and the peak ![]() of the 12CO

of the 12CO

![]() line observed at position A (top

panel) and B (bottom

panel). A wide range of temperatures (100-450 K) and

densities (>

line observed at position A (top

panel) and B (bottom

panel). A wide range of temperatures (100-450 K) and

densities (>

![]() )

are possible solutions for a 12CO column

density per line width

)

are possible solutions for a 12CO column

density per line width

![]()

![]() .

.

Table 1: M 17 SW line parameters derived from Gaussian fits, at four selected positions.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13077f9a.eps}\par\vspace*{2mm}

\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13077f9b.eps} \end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13077-09/Timg140.png)

|

Figure 9:

Top - the gray scale and contours represent

the average ( |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13077f9c.eps}\par\vspace*{2mm}

\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13077f9d.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/02/aa13077-09/Timg141.png)

|

Figure 10:

Top - the gray scale and contours represent

the average ( |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Figure 10 shows the possible ambient conditions estimated for position C (top panel) and D (bottom panel). The combinations of temperatures and densities required to reproduce the line ratios and peak temperatures are similar to those found for position A and B, although the range of possible temperatures (for a given density) at position D is larger than at the other positions. The column densities differ due to the different line strengths observed at the four positions (Table 1).

In order to constrain the range of solutions we can adopt the

average ![]() density estimated by M92, which is also similar to the mean density of

the clumps estimated by SG90. This is a sensitive assumption for a

collision dominated scenario since this density is larger than the

critical density of both 12CO lines

for

density estimated by M92, which is also similar to the mean density of

the clumps estimated by SG90. This is a sensitive assumption for a

collision dominated scenario since this density is larger than the

critical density of both 12CO lines

for ![]() K.

However, at this density (

K.

However, at this density (

![]() )

the temperature cannot be higher than 230 K in order to

reproduce the line ratio and the peak

)

the temperature cannot be higher than 230 K in order to

reproduce the line ratio and the peak

![]() of the 12CO

of the 12CO

![]() line observed at position A.

And it cannot be higher than

150 K at position B. At position C the limit is about

220 K, and at position D it is

about 200 K.

These are lower kinetic temperatures than the 1000 K estimated

for the dense clumps in the three-component model proposed by M92. Our

upper limits for the kinetic temperature agree with the results

reported in previous work (e.g Harris et al. 1987; S88;

SG90).

From the map of the excitation temperature

line observed at position A.

And it cannot be higher than

150 K at position B. At position C the limit is about

220 K, and at position D it is

about 200 K.

These are lower kinetic temperatures than the 1000 K estimated

for the dense clumps in the three-component model proposed by M92. Our

upper limits for the kinetic temperature agree with the results

reported in previous work (e.g Harris et al. 1987; S88;

SG90).

From the map of the excitation temperature

![]() estimated

from the LTE model (Fig. 7), the lower

limits for

estimated

from the LTE model (Fig. 7), the lower

limits for ![]() would be

would be ![]() 110 K

and

110 K

and ![]() 80 K

at position A & C and B & D, respectively. These are

similar (within 30%) to the lowest temperatures obtained with the

non-LTE models (Figs. 9 and 10).

80 K

at position A & C and B & D, respectively. These are

similar (within 30%) to the lowest temperatures obtained with the

non-LTE models (Figs. 9 and 10).

According to the radiative transfer model, temperatures up to

400 K and higher are also possible, but they require densities

of <

![]() in order to reproduce the

observed line ratios and peak temperatures.

These densities and temperatures are consistent with the estimates made

based on previous observations of the 12CO

in order to reproduce the

observed line ratios and peak temperatures.

These densities and temperatures are consistent with the estimates made

based on previous observations of the 12CO

![]() and

and

![]() lines (Harris et al. 1987;

SG90). On the other hand, clumps with densities of >

lines (Harris et al. 1987;

SG90). On the other hand, clumps with densities of >

![]() could also reproduce the

observed ratios and peak

could also reproduce the

observed ratios and peak ![]() in all the positions at temperatures

in all the positions at temperatures ![]() 200 K. However, these would be at the

lower limit of the temperature range estimated in Harris

et al. (1987)

and SG90. The densities and temperatures found for M 17 SW are

similar to those found in W3 Main (Kramer et al. 2004), but

higher (although compatible) than the kinetic temperatures found in

Carina, where lower limits between 30 K and 50 K were

estimated (Kramer et al. 2008).

200 K. However, these would be at the

lower limit of the temperature range estimated in Harris

et al. (1987)

and SG90. The densities and temperatures found for M 17 SW are

similar to those found in W3 Main (Kramer et al. 2004), but

higher (although compatible) than the kinetic temperatures found in

Carina, where lower limits between 30 K and 50 K were

estimated (Kramer et al. 2008).

4.3.1 Column densities at selected positions

The column density per line width

![]() at

position A varies over a small range of

at

position A varies over a small range of

![]() .

If we consider an average line width of 8.7

.

If we consider an average line width of 8.7

![]() estimated for the 12CO

estimated for the 12CO

![]() and

and ![]() lines (Table 1)

and the average

lines (Table 1)

and the average

![]() ,

we have a total column density of

,

we have a total column density of

![]() .

.

The model indicates that at position B the 12CO column

density per line width would be ![]()

![]() .

The average line width of the lines at position B is

.

The average line width of the lines at position B is ![]() 7.7

7.7

![]() (Table 1), which

gives a total column density of

(Table 1), which

gives a total column density of

![]() ,

similar to the column found at position A. At positions C and D the

average column densities per line width are

,

similar to the column found at position A. At positions C and D the

average column densities per line width are ![]()

![]() and

and

![]()

![]() ,

respectively. Considering a line width of

,

respectively. Considering a line width of ![]() 6

6

![]() we obtain similar column

densities as in the previous two positions.

That is

we obtain similar column

densities as in the previous two positions.

That is

![]() and

and

![]() for

positions C and D, respectively. At positions A

and C the lines are optically thin, with

for

positions C and D, respectively. At positions A

and C the lines are optically thin, with ![]() ranging from about 0.6 to 1 for

ranging from about 0.6 to 1 for

![]() K.

At temperatures of

K.

At temperatures of ![]() K,

the lines become optically thick (

K,

the lines become optically thick (

![]() ). The optically thin limit at

positions B and D is reached at

). The optically thin limit at

positions B and D is reached at

![]() K,

with about the same ranges of optical depths as before, for

temperatures higher or lower than 120 K.

K,

with about the same ranges of optical depths as before, for

temperatures higher or lower than 120 K.

Assuming a density of

![]() and

average temperatures of 200 K at position A and

150 K at position B, the non-LTE model indicates that

13CO column densities of

and

average temperatures of 200 K at position A and

150 K at position B, the non-LTE model indicates that

13CO column densities of ![]()

![]() and

and

![]()

![]() would be required to reproduce the observed strength (Table 1) of the 13CO

would be required to reproduce the observed strength (Table 1) of the 13CO

![]() line

at these positions, respectively. For a temperature of 200 K,

the 13CO column density at position C

and D would be

line

at these positions, respectively. For a temperature of 200 K,

the 13CO column density at position C

and D would be ![]()

![]() .

And the excitation temperatures would be

.

And the excitation temperatures would be ![]() 180 K at position A, C and D, and

180 K at position A, C and D, and ![]() 140 K

at position B, which are higher temperatures than estimated

with the LTE approximation. However, these excitation temperatures are

just between 10 and 20 K lower than the assumed kinetic

temperatures, which indicates that these lines are close

(within 10%) to the thermal equilibrium.

140 K

at position B, which are higher temperatures than estimated

with the LTE approximation. However, these excitation temperatures are

just between 10 and 20 K lower than the assumed kinetic

temperatures, which indicates that these lines are close

(within 10%) to the thermal equilibrium.

From their C18O

![]() observations, S88 estimated a 12CO beam-averaged

column density of

observations, S88 estimated a 12CO beam-averaged