| Issue |

A&A

Volume 654, October 2021

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A172 | |

| Number of page(s) | 6 | |

| Section | Atomic, molecular, and nuclear data | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202141597 | |

| Published online | 27 October 2021 | |

Photoionisation of the CH radical using the B-spline R-matrix method★

School of Physics, Henan Normal University,

Xinxiang

453007,

PR China

e-mail: wangkd@htu.cn; Yangchj@hotmail.com

Received:

20

June

2021

Accepted:

23

August

2021

Aims. The primary motivation for this paper is to provide accurate data for the photoionisation of the CH radical, including the absolute total photoionisation cross-section, partial cross-sections, and photoelectron angular distribution. In addition, the near threshold features in the photoionisation curve (which are absent in previous studies) are produced with high precision.

Methods. A multichannel wavefunction based on the R-matrix approach, which uses the configuration interaction (CI) method to describe electronic correlation, is carried out in the present calculations. A set of B-spline orbitals is employed to represent the accurate continuum. The distinctive feature of the present calculations allows us to generate a more accurate description of the bound and continuum states than those employed before.

Results. Total photoionisation cross-sections from the ground state of CH radicals and partial cross-sections corresponding to 1π, 3σ, and 2σ states of CH+ ions are presented for photon energies ranging from threshold to 80 eV. Extensive resonance structures, which are absent in previous studies, are observed for the first time near the ionisation threshold. The cross-section dataset obtained from the present calculations is expected to be sufficiently accurate and comprehensive for most current modelling applications involving the photon and CH radical scattering system.

Key words: molecular data / molecular processes / methods: numerical / ultraviolet: ISM

Data tables for cross-sections are only available at the CDS via anonymous ftp to cdsarc.u-strasbg.fr (130.79.128.5) or via http://cdsarc.u-strasbg.fr/viz-bin/cat/J/A+A/654/A172

© ESO 2021

1 Introduction

The response of atomic systems to ionising radiation is a dominant process in the Universe. It involves neutral atoms, molecules, and clusters, as well as their ions, and takes place in many physical systems including a variety of astrophysical objects, the upper atmosphere, fission, and fusion plasmas, and laser-produced plasma. In many cases, the role of the photoionisation process is central in determining the overall properties of a system. CH is one of the basic components in a variety of astronomical objects, including interstellar clouds (Smith 1992), comets (Wyckoff et al. 1988), and stars (Singh & Chaturvedi 1987). Because of its special importance in these aspects, the CH radical attracts considerable astrophysical interest. Photoionisation and photodissociation of CH, together with the dissociative recombination of CH+, play an important role in modelling the relative abundances of CH+∕CH in diffuse interstellar clouds (van Dishoeck 1987; Federman & Lambert 2002; Heays et al. 2017). However, the formation mechanism of CH+ is difficult to explain. One long-running issue is that the observed interstellar medium (ISM) concentration of CH+ is persistently larger than that predicted by the theoretical models from Smith et al. (2014), Godard & Cernicharo (2013), and Myers et al. (2015). This problem was later considered in great detail by Faure et al. (2017) who showed that the proper treatment of non-local thermodynamic equilibrium effects are essential to modelling the production of CH+ ions in the ISM. Reliable cross-sections for photoionisation dynamics are therefore needed for astrophysical model calculations.

Numerous experimental techniques have been employed to study this radical and its cation: absorption (Herzberg & Johns 1969; Davidson et al. 2001; Watson 2001; Pearson & Drouin 2006) and fluorescence (Zachwieja 1997; Ghosh et al. 1999; Truppe et al. 2014) spectroscopy over an extended energy range from the millimeter wave (MW) into the vacuum ultra violet (VUV) and resonance-enhanced multiphoton ionisation (REMPI) (Chen et al. 2000). These measurements have produced very precise descriptions of CH and CH+ in their ground- and excited electronic states. Several related theoretical studies have also been carried out on the lowest electronic states of CH and CH+ (Baluja & Msezane 2001; Vázqueza et al. 2007; Hamilton et al. 2016; Chakrabarti et al. 2017, 2019).

For the ionisation process, to our knowledge, the only currently available experimental observations for photonionisation of CH radicals over the energy range from threshold to 12 eV originate from the measurements by Gans et al. (2016), who produce the radicals by successive hydrogen-atom abstractions on methane by fluorine atoms in a continuous microwave discharge flow tube. On the theoretical side, photoionisation spectra of CH radicals were reported by several groups. A study by Walker & Kelly (1972) based on many-body perturbation theory, predicted total photoionisation cross-sections of CH over a broad photoenergy range. However, these data suggested substantially larger values for the cross-sections than the later results calculated by Barsuhn & Nesbet (1978). Barsuhn & Nesbet (1978) predicted the photoionisation cross-section using the Stieltjes-imaging method and a configuration-interaction target wave function. Subsequently, based on the Schwinger variational method using multiplet-specific Hartree-Fock potentials (MSHF) and numerical continuum orbitals, Lee et al. (1990) predicted cross-sections and photoelectron angular distributions for the 3σ and 1π levels of CH. Finally,a molecular-adapted quantum defect calculation was reported by Lavín et al. (2009), who used semi-empirical model potential methods. These authors only considered photoionisation cross-sections leading to the ground state of the CH+ ion. Recently, using measured and calculated cross-sections from several different databanks, Heays et al. (2017) compiled photoabsorption and photoionisation cross-sections of CH radicals and modelled their photodissociation and photoionisation rates.

The above discussion shows that the experimental result is available in the relatively narrow range of incident energies up to 12 eV. All the calculations predicted sparse spectra, and no study provided significant details near the ionisation threshold. The goal of the present work is therefore to provide an extensive dataset of cross-sections for the photoionisation of CH radicals. The present calculations were performed with the R-matrix method (Mašín et al. 2020) employing the configuration interaction (CI) method to describe electronic correlation. The distinctive feature of the method is the use of B-spline orbitals to generate accurate descriptions of the continuum. This feature was clearly illustrated in detail in our recent benchmark calculations for photoionisation of OH radicals (Wang et al. 2021). This is very important for an accurate description of resonances and autoionisation processes, especially when they are located very close to the thresholds.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes the computational method for the structure and the photoionisation processes. This is followed by our results and their discussion in Sect. 3, and finally our conclusions in Sect. 4.

2 Computational details

2.1 Theoretical method

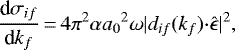

The differential cross-sections for photoionisation of a molecule in the length gauge are represented as (Tennyson et al. 1986; Harvey et al. 2014):

(1)

(1)

where α is the fine structure constant, a0 is the Bohr radius, ω is the photon energy in atomic units, ϵ is the polarisation vector of the ionising light in the molecular frame, and dif (kf) is the molecular frame transition dipole between the initial state, i, and a single continuum state, j, as a function of the ejected electron momentum, kf.

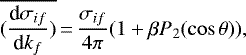

If the molecular frame cannot be recovered, Eq. (1) must be orientationally averaged and in the case of linearly polarised laser field one obtains

(2)

(2)

where β is the asymmetry parameter, σif is the partial photoionisation cross-section, P2 is the second-order legendre polynomial, and θ is the electron ejection angle between the photoelectron emission direction and photon polarisation direction in the case of linear polarisation.

In the present paper, the bound and continuum wavefunctions in Eq. (1) are presented with an R-matrix calculation. The key feature of the R-matrix method (Burke 2011) is the division of space into two separate regions in which different approximations can be made. The usual division is into an inner, outer, and asymptotic region. The boundary between the inner and outer region is defined so as to fully contain the bound wavefunctions of the molecule. In the inner region, the electron-electron effects, exchange, polarisation, and correlation are fully accounted for in a manner analogous to a quantum chemistry calculation, and a flexible basis is constructed to describe thescattering or bound wavefunction in the inner region. The R-matrix is defined on the boundary and relates the radial part of the continuum electron wavefunction to its derivative. In the outer region, exchange is neglected and the continuum electron moves in the long-range multipole potential of the molecule. The R-matrix is propagated through the outer region and matched to known asymptotic solutions, allowing for the calculation of observables and giving the expansion coefficients of the full multi-electron wavefunction in terms of the inner region basis.

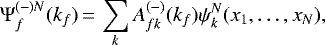

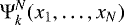

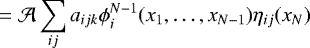

In the inner region, both the continuum and the bound-state wavefunctions are given in terms of the basis functions,  , as

, as

(3)

(3)

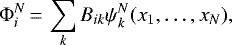

(4)

(4)

where  and Bik are energy-dependent expansion coefficients determined from matching the wavefunctions Eqs. (3) and (4) to the well-known asymptotic solutions of the system, and xi stands for the space-spin coordinates of the ith electron. The R-matrix basis functions

and Bik are energy-dependent expansion coefficients determined from matching the wavefunctions Eqs. (3) and (4) to the well-known asymptotic solutions of the system, and xi stands for the space-spin coordinates of the ith electron. The R-matrix basis functions  in turn are written in the close-coupling (CC) form

in turn are written in the close-coupling (CC) form

(5)

(5)

Here, ηij are the continuum orbitals orthogonalised with respect to the target orbitals, and  is an antisymmetrisation operator. Coefficients aijk and bkp are variational parameters determined by the matrix diagonalisation. The summation in the second term of Eq. (5) runs over configurations χp, where all electrons are placed in target-occupied and virtual molecular orbitals. The choice of appropriate χp is crucial. These are L2 configurations and are needed to account for polarisation and for correlation effects arising from excitations in the neutral molecule.

is an antisymmetrisation operator. Coefficients aijk and bkp are variational parameters determined by the matrix diagonalisation. The summation in the second term of Eq. (5) runs over configurations χp, where all electrons are placed in target-occupied and virtual molecular orbitals. The choice of appropriate χp is crucial. These are L2 configurations and are needed to account for polarisation and for correlation effects arising from excitations in the neutral molecule.

2.2 Target model

The UKRMol+ package (Mašín et al. 2020) is employed to investigate photoionisation for the ground state of CH radicals. The multichannel close coupling (CC) calculations were performed at the equilibrium geometry with RCH = 1.120 Å for the X2Π ground state (Huber & Herzberg 1979). The electronic configuration for the ground state of CH radicals is 1σ2 2σ23σ21π1. The self-consistent field Hartree-Fock molecular orbitals were generated with the 6-311G** basis set using the Molpro programs (Werner et al. 2012). The complete active space (CAS) configuration interaction (CI) method was used to deal with photoionisation of the CH radical. In the CAS-CI model, the orbitals of CH are represented as a sum of frozen and active orbitals as  and

and  , respectively. For the CH+ target, the two frozen electrons will remain in the same orbital configuration and the other four electrons are shared among 17 active orbitals.

, respectively. For the CH+ target, the two frozen electrons will remain in the same orbital configuration and the other four electrons are shared among 17 active orbitals.

The calculated vertical ionisation potentials (IPs) for the first ten low-lying states are listed in Table 1, together with the previous experimental results (Herzberg & Johns 1969; Gans et al. 2016) for comparison. As shown in the table, the IP values are in good agreement with the experimental results (Herzberg & Johns 1969; Gans et al. 2016). The principal configuration state functions (CSFs) of the ion states were also listed in Table 1. It is clearly evident that removal of a single electron gives rise to various states. Some of the configurations have the same primary configuration and differ by their spin symmetry.

Vertical ionisation potentials (in eV) for CH radicals obtained with the 6-311G** basis set.

2.3 Inner and outer regions

In the inner region, the continuum orbital is constructed from BTOs centered on the center of mass of the system. B-spline basis functions allow calculations with higher kinetic energies of the free electron and the use of greatly enlarged inner regions allowing both large targets and targets with more diffuse electronic states to be studied. The order of B-splines and the maximum number of radical B-splines were taken to be k = 6 and N = 20 in the present calculations. The first two radial B-splines are not included in the basis because these have a nonzero first derivative at the starting point. These continuum orbitals are orthogonalised to the target orbitals, and the continuum orbitals with an overlap of less than 10−5 were removed (Morgan et al. 1997). The value of the R-matrix radius taken to enclose total charges of the target inside the inner region was 15a0. The maximum angular momentum lmax = 4 was used to perform partial wave expansions.

In the present calculations, the L2 configurations in Eq. (5) can be written in two classes, (core)2(CAS)4(virtual)1 and (core)2(CAS)5. Here the active space is composed of 2σ–12σ, 1π–5π, and 1δ orbitals. The inclusion of a large number of target states is necessary to converge the close coupling expansion and to avoid any unphysical pseudoresonances that may otherwise appear at higher energies related to target states left out of the expansion. The number of target states employed in the present CC expansion is 80, which is enough to obtain the convergence of the CC expansion.

|

Fig. 1 Total photoionisation cross-sections from the X2Π ground state of CH radials calculated with our best model in the energy range (a) 10.60–11.80 eV, (b) 10-80 eV, the inset panel shows the same cross-sections for the energy range 10.50–14.0 eV. Comparison with the available results. |

3 Results and discussion

The total photoionisation cross-sections from the X2Π ground state of CH radials in the energy region between 10.60 eV and 11.80 eV are shown in Fig. 1a. We used a fine mesh for photon energies in steps of 0.04 eV to scan and properly separate the possible resonance structures. The relative photoionisation spectra of CH radials measured by Gans et al. (2016) using a double imaging photoelectron/photoion coincidence spectrometer are also shown in Fig. 1a. For comparison, the ionisation threshold has been shifted to the empirical values. Our total cross-section shows numerous sharp peaks originating from two- or many electron excited resonances as well as Rydberg resonances associated with the excited electronic states of the CH+ ion. In addition to the minimum at 11.6 eV, there are two peaks at around 10.88 and 10.96 eV, which are in good agreement with the experimental results of Gans et al. (2016). In the higher-energy region, the positions for autoionisation peaks predicted by us are slightly different from the experimental results, and the experimental results show more peaks in the cross-section. This is due to the measured results including vibrational effects which are not considered in our present calculations where the fixed-nuclei approximation is used.

In Fig. 1b we show the total photoionisation cross-sections in the energy region from 10 to 80 eV. Three theoretical studies, namely those performed by Walker & Kelly (1972) based on many-body perturbation theory, by Barsuhn & Nesbet (1978) using the Stieltjes-imaging method and a configuration-interaction target wave function, and by Lee et al. (1990) using MSHF potentials, are also plotted in Fig. 1b for comparison. With increasing photo energies, discrepancies between all these three calculations diminish. In the resonant region below 18 eV, MSHF results are clearly lower than our cross-sections. This is because the correlation is not considered in the approach and photoionisation of the 2σ is not includedin their calculations. In general, the total cross-sections obtained by Walker & Kelly (1972) are in good agreement with our results, although their results are slightly higher in the energy region from 23 to 40 eV. Below 14 eV, the theoretical results from Barsuhn & Nesbet (1978) agree with our results, but for the photon energy range from 14 to 17 eV, their cross-sections become lower. It should be noted that Barsuhn & Nesbet (1978) performed CI calculations on single excitation series and their photoionisation cross-sections are extracted from the discrete CI spectrum, whereas we used a CAS-CI package of programs.

Our calculated cross-section values are also compared to those available in databases dedicated to astrophysical models. For instance, the Leiden database (Heays et al. 2017) proposes CH photoionisation cross-section values using the results of Barsuhn & Nesbet (1978). The resulting curve is presented in Fig. 1b in orange. In general, this curve agrees with our results in the low-energy region from the threshold to 11.60 eV and in the other energy region from 11.90 to 13.70 eV. With the photon energy between 11.60 and 11.90 eV, the curve exhibits a peak centered at 12.81 eV with a width of about 0.85 eV, and is higher than our results.

Figure 2 presents the partial cross-sections and asymmetry parameters for photoionisation from the ground state of CH leading to the X1Σ+ state of CH+ ions. A comparison is made between our results and the available theoretical work of Barsuhn & Nesbet (1978), Lee et al. (1990), and Lavín et al. (2009). In general, the present cross-sections are consistent with the other theoretical results. Among these results, the data of Lavín et al. (2009) show the best agreement with our results, except for the lack of resonant structures near thresholds in their cross-section, as can be seen in the picture. Our results for the photoelectron asymmetry parameters for this channel shown in Fig. 2 are compared with the data of Lee et al. (1990). The inclusion of correlation effects causes their asymmetry parameters to show a loss of intensity at the energy below 40 eV. Similar to the cross-sections, our asymmetry parameters show numerous sharp peaks, while other available results are very smooth. With respect to the behaviour of the cross-sections, the asymmetry parameters are more affected by electron correlation effects, as can be judged from the large differences between our results and the MSHF results. The similar correlation effect on photoionisation observables was investigated in our previous paper (Wang et al. 2021).

Figure 3 shows cross-sections and asymmetry parameters for ionisation from the ground state of CH leading to the a3 Π state of CH+ ions with the previous theoretical results. The theoretical data obtained by Barsuhn & Nesbet (1978) are in agreement with those obtained here in the low-energy region below 14 eV, but are quite different from our results in the energy region between 14 and 17 eV. The results of Lee et al. (1990) display smaller cross-sections in the energy region from the threshold to 20 eV, but show good agreement with our results in the energy region between 20 and 45 eV. For the photon energy beyond 45 eV, there is no available experimental or theoretical data for comparison. In contrast with the results of Lee et al. (1990), our photoelectron asymmetry parameters in a3 Π, presented in Fig. 3, show a similar trend to those found in the X1 Σ+ channel presented in Fig. 2.

Figure 4 shows photoionisation cross-sections and asymmetry parameters for ionisation from the ground state of CH leading to the A1Π state of CH+ ions, together with other theoretical results, included for comparison. Overall, our present cross-sections are in agreement with other available theoretical data in the resonant region below 20 eV. Above 20 eV, our cross-sections are 0.5 Mb lower than those found by Lee et al. (1990). We also note that the photoelectron asymmetry parameters in A1 Π presented in Fig. 4 are almost identical to those obtained in the a3 Π channel presented in Fig. 3.

In astrochemistry, photoionisation cross-sections can be converted to photoionisation rates if the photon flux is known in a given region of space. By quantitatively constraining the rates of photoprocesses, other chemical and physical parameters can be more reliably obtained, thus facilitating the interpretation of observations. The photoionisation rate of a molecule exposed to an ultraviolet radiation fields is

(6)

(6)

where σ(λ) is the photoionisation cross-section, and I(λ) is the photon-based radiation intensity summed over all incidence angles. The rate of photoionisation of CH radicals in seven different astrophysically relevent ultraviolet radiation fields is shown in Table 2, together with the available rate values from the Leiden database (Heays et al. 2017) for comparison. Our rate is lower than those shown in the Leiden database for interstellar radiation field (ISRF) from Draine (1978), Galactic radiation field made by Mathis et al. (1983), and black-body radiation field. But in both solar (Curdt et al. 2001) and TW-Hya (France et al. 2014) radiation fields, our rate is higher. Considering the more precise photoionisation cross-sections used in our calculation, the present result should be more accurate than those found before.

|

Fig. 2 Photoionisation cross-section and asymmetry parameter for ionisation from the ground state of CH leading to the X1 Σ+ state of CH+ ions. |

|

Fig. 3 Photoionisation cross-section and asymmetry parameter for ionisaiton from the ground state of CH leading to the a3 Π state of CH+ ions. |

|

Fig. 4 Photoionisation cross-section and asymmetry parameter for ionisation from the ground state of CH leading to the A1 Π state of CH+ ions. |

Photoionisation rates (in s−1) for CH radicals in different radiation fields.

4 Summary

We describe an extensive calculation of the photoionisation of the ground state of CH radicals and present both total and partial cross-sections, as well as asymmetry parameters. The present calculations were performed with the multichannel R-matrix method, where a B-spline basis is employed to represent the continuum orbitals and the configuration interaction method is used to describe electronic correlation. This distinctive feature of the present calculations allowed us to generate a more accurate description of the bound and continuum states than those employed before.

The total photoionisation cross-sections from the ground state of CH radicals and partial cross-sections corresponding to 1π, 3σ, and 2σ states of CH+ ions are presented. The predicted photoionisation observables are compared with available results. Our experience with such calculations leads us to suggest that the present results are by far the most accurate available today. An extensive resonance structure near threshold, which is absent in previous studies, is observed for the first time.

Experimental measurements of the photoionisation dynamical parameters are challenging, in particular for free radicals. Therefore, they are often missing or are found in the literature within a wide range. This is the first theoretical calculation in such a high-energy spectral region with highly accurate values of valence state photoionisation cross-sections. We hope that the dearth of data on the photodynamics involving CH radicals encourages further experimental and theoretical investigations.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China under grant nos. U1504109 and 11604085 and of Henan Province under grant no. 212300410054, the Program for Science and Technology Innovation Talents in the Universities of Henan Province under grant no. 19HASTIT018, and the Science Foundation of Henan Normal University under grants nos. YQ201601 and 2021PL14.

References

- Baluja, K. L., & Msezane, A. Z. 2001, J. Phys. B, 34, 3157 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Barsuhn, J., & Nesbet, R. K. 1978, J. Chem. Phys., 68, 2783 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Burke, P. G. 2011, R-Matrix Theory of Atomic Collisions (Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag) [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti, K., Dora, A., Ghosh, R., Choudhury, B. S., & Tennyson, J. 2017, J. Phys. B, 50, 175202 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabarti, K., Ghosh, R., & Choudhury, B. S. 2019, J. Phys. B, 50, 105205 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y., Jin, J., Pei, L., Ma, X., & Chen C. 2000, J. Electron Spectr. Rel. Phenom., 108, 221 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Curdt, W., Brekke, P., Feldman, U., et al. 2001, A&A, 375, 591 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, S. A., Evenson, K. M., & Brown, J. M. 2001, ApJ, 546, 330 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Draine, B. T. 1978, ApJS, 36, 595 [Google Scholar]

- Faure, A., Halvick, P., Stoecklin, T., et al. 2017, MNRAS, 469, 612 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Federman, S. R., & Lambert, D. L. 2002, J. Electron Spectr. Rel. Phenom., 123, 161 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- France, K., Schindhelm E., Bergin E. A., Roueff, E., & Abgrall, H. 2014, ApJ, 784, 127 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gans, B., Holzmeier, F., Krüger, J., et al. 2016, J. Chem. Phys., 144, 204307 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, P. N., Deo, M. N., & Kawaguchi, K. 1999, ApJ, 525, 539 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Godard, B., & Cernicharo, J. 2013, A&A, 550, A8 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, J. R., Faure, A., & Tennyson, J. 2016, MNRAS, 455, 3281 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, A. G., Brambila, D. S., Morales, F., & Smirnova, O. 2014, J. Phys., B, 47, 215005 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Heays, A. N., Bosman, A. D., & van Dishoeck, E. F. 1987, J. Chem. Phys., 86, 196 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Herzberg, G., & Johns, J. W. C. 1969, ApJ, 158, 399 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Huber, K. P., & Herzberg, G. 1979, Constants of Diatomic Molecules (New York: Springer) [Google Scholar]

- Lavín, C., Velasco, A. M., & Martín, I. 2009, ApJ, 692, 1354 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M. T., Stephens, J. A., & McKoy, V. 1990, J. Chem. Phys., 92, 536 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mašín, Z., Benda, J., Gorfinkiel, J. D., Harvey, A. G., & Tennyson, J. 2020, Comput. Phys. Commun., 249, 107092 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mathis, J. S., Mezger, P. G., Panagia, N. 1983, A&A, 500, 259 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, L. A., Gillan, C. J., Tennyson, J., & Chen, X. 1997, J. Phys. B, 30, 4087 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Myers, A. T., McKee C. F., & Li, P. S. 2015, MNRAS, 453, 2747 [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, J. C., & Drouin, B. J., 2006, ApJ, 647, L83 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, M., & Chaturvedi, J. P. 2010, ApJS, 136, 231 [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D. 1992, Chem. Rev., 92, 1473 [Google Scholar]

- Smith, H. W., Liszt, H. S., & Lutz, B. L. 1973, ApJ, 183, 69 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tennyson, J., Noble, C. J., & Burke, P. G. 1986, Int. J. Quant. Chem., 29, 1033 [Google Scholar]

- Truppe, S., Hendricks, R. J., Hinds, E. A., & Tarbutt, M. R. 2014, ApJ, 780, 71 [Google Scholar]

- van Dishoeck, E. F. 1987, J. Chem. Phys., 86, 196 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Vázqueza, G. J., Amero, J. M., Liebermann, H. P., Buenker R. J., & Lefebvre-Brion, H. 2007, J. Chem. Phys., 126, 164 302 [Google Scholar]

- Walker, T. E. H., & Kelly, H. P. 1972, Chem. Phys. Lett., 16, 511 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K. D., Liu, J., Zhang, H. X., & Liu, Y. F. 2021, Phys. Rev. A., 103, 063101 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Watson, J. K. G. 2001, ApJ, 555, 472 [Google Scholar]

- Werner, H. J., Knowles, P. J., Knizia, G., Manby, F. R., & Schütz, M. 2012, WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci., 2, 242 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wyckoff, S., Tegler, S., Wehinger, P. A., Spinrad, H., & Belton, M. J. S. 1988, ApJ, 325, 927 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Zachwieja, M. 1997, J. Mol. Spectr., 182, 18 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

All Tables

Vertical ionisation potentials (in eV) for CH radicals obtained with the 6-311G** basis set.

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Total photoionisation cross-sections from the X2Π ground state of CH radials calculated with our best model in the energy range (a) 10.60–11.80 eV, (b) 10-80 eV, the inset panel shows the same cross-sections for the energy range 10.50–14.0 eV. Comparison with the available results. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Photoionisation cross-section and asymmetry parameter for ionisation from the ground state of CH leading to the X1 Σ+ state of CH+ ions. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 Photoionisation cross-section and asymmetry parameter for ionisaiton from the ground state of CH leading to the a3 Π state of CH+ ions. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4 Photoionisation cross-section and asymmetry parameter for ionisation from the ground state of CH leading to the A1 Π state of CH+ ions. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.