| Issue |

A&A

Volume 558, October 2013

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A60 | |

| Number of page(s) | 5 | |

| Section | Extragalactic astronomy | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201321599 | |

| Published online | 03 October 2013 | |

A gas-rich AGN near the centre of a galaxy cluster at z ~ 1.4⋆,⋆⋆

1 INAF – Istituto di Radioastronomia & Italian ALMA Regional Centre, via P. Gobetti 101, 40129 Bologna, Italy

e-mail: casasola@ira.inaf.it

2 INAF – Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri, Largo E. Fermi 5, 50125 Firenze, Italy

3 Observatoire de Paris, LERMA, 61 Av. de l’Observatoire, 75014 Paris, France

4 Dipartimento di Fisica e Astronomia, Università di Bologna, Viale Berti Pichat 6/2, 40127 Bologna, Italy

Received: 29 March 2013

Accepted: 12 July 2013

Context. The formation of the first virialized structures in overdensities dates back to ~9 Gyr ago, i.e. in the redshift range z ~ 1.4−1.6. Some models of structure formation predict that the star formation activity in clusters was high at that epoch, implying large reservoirs of cold molecular gas.

Aims. Aiming at finding a trace of this expected high molecular gas content in primeval clusters, we searched for the 12CO(2–1) line emission in the most luminous active galactic nucleus (AGN) of the cluster around the radio galaxy 7C 1756+6520 at z ~ 1.4, one of the farthest spectroscopic confirmed clusters. This AGN, called AGN.1317, is located in the neighbourhood of the central radio galaxy at a projected distance of ~780 kpc.

Methods. The IRAM Plateau de Bure Interferometer was used to investigate the molecular gas quantity in AGN.1317, observing the 12CO(2−1) emission line.

Results. We detect CO emission in an AGN belonging to a galaxy cluster at z ~ 1.4. We measured a molecular gas mass of 1.1 × 1010M⊙, comparable to that found in submillimeter galaxies. In optical images, AGN.1317 does not seem to be part of a galaxy interaction or merger. We also derived the nearly instantaneous star formation rate (SFR) from Hα flux obtaining a SFR ~ 65 M⊙ yr-1. This suggests that AGN.1317 is actively forming stars and will exhaust its reservoir of cold gas in ~0.2−1.0 Gyr.

Key words: galaxies: active / galaxies: individual: AGN 1317 / galaxies: clusters: individual: 7C 1756+6520 / galaxies: distances and redshifts / galaxies: high-redshift / galaxies: ISM

Based on observations carried out with the IRAM Plateau de Bure Interferometer. IRAM is supported by INSU/CNRS (France), MPG (Germany), and IGN (Spain).

Reduced IRAM data is only available at the CDS via anonymous ftp to cdsarc.u-strasbg.fr (130.79.128.5) or via http://cdsarc.u-strasbg.fr/viz-bin/qcat?J/A+A/558/A60

© ESO, 2013

1. Introduction

Galaxy clusters are the largest collapsed structures in the Universe with total masses up to 1015M⊙ (e.g. Arnaud 2009). One of the most important issues related to the study of galaxy clusters is the evolution of their star formation (SF) activity. Some models of galaxy evolution in dense environments predict that the SF in clusters was high at the epoch of the formation of galaxy clusters, i.e. z ~ 1.5, and later at z ~ 1 it was rapidly quenched (e.g. Martig & Bournaud 2008; Taranu et al. 2012; Wetzel et al. 2013). One key requirement for SF is the presence of a reservoir of dense, cold gas that can be efficiently converted into stars. This is especially crucial for galaxies in rich clusters, because they are expected to be affected by mechanisms able to remove cold gas from the haloes and discs of infalling galaxies (e.g. ram pressure stripping, Gunn & Gott 1972) or to prevent further cooling of gas within galaxies’ dark matter haloes (starvation or strangulation, e.g. Larson et al. 1980; Bekki et al. 2002). This environmental dependence profoundly influences the evolutionary histories of galaxy clusters and the star formation-galaxy density relation represents a well-established observational hallmark of how galaxies evolve as a function of environment.

|

Fig. 1 Location of the galaxies belonging to Group1 (z ~ 1.42) and Group2 (z ~ 1.44) in the B-band image (NOAO). Galaxies of Group1 are represented by red circles, while those of Group2 by blue triangles. The central radio galaxy 7C 1756+6520 is the red star and belongs to Group1. North is at the top and east to the left. The field of view is ~500′′ × 200′′ centred on the radio galaxy. 1′′ corresponds to ~8.4 kpc. |

Studies based on multi-wavelength tracers of SF activity have shown that SF decreases with increasing galaxy density at z < 1 (e.g. Hashimoto et al. 1998; Ellingson et al. 2001; Gómez et al. 2003; Patel et al. 2009). At intermediate redshift (z ~ 0.2) luminous infrared galaxies are preferentially forming stars at the outskirts of some massive clusters (e.g. Haines et al. 2010), suggesting that SF may be quenched within the central regions at these epochs. As we approach the epoch when galaxies should be forming the bulk of their stars (z > 1), there is some controversy in literature on the star formation-density relation for clusters at z > 1. Some works found that the above relation reverses at z > 1 (Elbaz et al. 2007; Cooper et al. 2008; Hilton et al. 2010; Tran et al. 2010), while others that the period between 1 < z < 2 is the one when active SF is suppressed in the very central regions of galaxy clusters (Strazzullo et al. 2010; Bauer et al. 2011; Grützbauch et al. 2012). In the first scenario, the redshift range z ~ 1.4 − 1.6 seems to correspond to the epoch in which galaxy clusters showed the highest star formation rate (SFR), especially in their central regions, in contrast to what is observed at z < 1, while in the second scenario star-forming galaxies are seen at the outskirts of the clusters. Furthermore, the number of cluster galaxies with one or more AGN has been found to increase out to redshifts z > 1, and they lie preferentially near the cluster centre (e.g. Galametz et al. 2009; Martini et al. 2009, 2013). The SF and AGN activity in high-z cluster galaxies should, therefore, both be fueled by significant reservoirs of molecular gas. Observations of this gas in high-z clusters can provide insights into the processes governing galaxy evolution in dense environments.

So far, molecular gas has been detected in distant (z > 1) galaxies in a hundred objects (see the review by Solomon & Vanden Bout 2005), but only few of them belong to clusters. The most distant detection is related to a z = 7.08 quasar host galaxy, where the fine structure line of [C ii] 158 μm and the thermal dust continuum were detected by Venemans et al. (2012). For cluster galaxies the situation is the following: at intermediate redshift, Geach et al. (2009, 2011) presented 12CO(1−0) detections in five starburst galaxies in the outskirts of the rich cluster Cl 0024+16 at z ~ 0.4, and Jablonka et al. (2013) reported CO detections in three luminous infrared galaxies belonging to the clusters CL 1416+4446 at z ~ 0.4 and CL 0926+1242 at z ~ 0.5. At higher redshift, Wagg et al. (2012a) presented 12CO(2−1) missing detections toward two dust-obscured galaxies with AGN and a serendipitous detection in an obscured AGN belonging to a cluster at z ~ 1. Very recently, Emonts et al. (2013) found a 12CO(1–0) detection in the so-called Spiderweb Galaxy at z ~ 2, one of the most massive systems in the early Universe and surrounded by a dense web of proto-cluster galaxies. The Lyα nebulae, called Lyα blobs (LABs) at z ~ 2−6, have also been the object of molecular gas observational campaigns, collecting for the moment non-detections or tentative detections (e.g. Chapman et al. 2004; Matsuda et al. 2007; Tamura et al. 2009; Yang et al. 2012; Wagg & Kanekar 2012). Their nature is at present still poorly understood, but they could represent proto-clusters hosting an AGN at their centre (e.g. Cen & Zheng 2013). Finally, using ALMA Wagg et al. (2012b) detected the [C ii] line and thermal dust emission from a pair of gas-rich galaxies at z = 4.7, BR1202-0725, a possible proto-cluster, but detected only dust continuum from a third companion whose redshift remains unknown. To summarise, the only secure CO detection in a high-z (~1) cluster AGN is, to our knowledge, that given in Wagg et al. (2012a).

In this work, we present the first observations of the 12CO(2−1) emission line toward an AGN, AGN.1317, belonging to a galaxy cluster at z ~ 1.4, obtained using the IRAM Plateau de Bure Interferometer (PdBI). This paper is structured as follows. In Sect. 2, we present the main properties of AGN.1317. In Sect. 3, we describe our CO observations, and the corresponding results are collected in Sect. 4. The discussion of results is presented in Sect. 5, and finally we summarise this work in Sect. 6. In the present paper, we adopt the following values for the cosmological constants, H0 = 70 km s-1 Mpc-1, Ωm = 0.3, and ΩΛ = 0.7 corresponding to the ΛCDM cosmology. With these values, 1′′ corresponds to ~8.4 kpc at z ~ 1.4.

Fundamental characteristics of the overdensity of galaxies associated with 7C 1756+6520 and of AGN.1317.

2. The source: AGN.1317

Galametz et al. (2009, 2010) have isolated and spectroscopically confirmed, through the optical Keck/DEep Imaging Multi-Object Spectrograph (DEIMOS), an overdensity of galaxies associated with the radio galaxy 7C 1756+6520 at z = 1.4156. In addition to the central radio galaxy, they confirmed twenty-one galaxies with spectroscopic redshifts consistent with that of 7C 1756+6520. In the field around the radio galaxy the velocity dispersion is rather large, up to ~13 000 km s-1 (Galametz et al. 2010, hereafter G10), and the ensemble has not yet relaxed into one big structure. For this reason, the overall structure is better defined as an overdensity, while two distinct smaller substructures have been identified and designated as clusters of galaxies: one of seven galaxies (Group1) with redshift similar to that of the central radio galaxy (z ~ 1.42), and a more compact one at z ~ 1.44 (Group2). Galaxies belonging both to Group1 and Group2 are within 2 Mpc from the radio galaxy, while most of other galaxies belonging to the large-scale overdensity are more than 2 Mpc away from the radio galaxy. Figure 1 shows a portion of the galaxy overdensity associated with 7C 1756+6520. In this figure, cluster galaxies belonging to Group1 and Group2 are clearly marked with different symbols and colours.

Six of the spectroscopically confirmed galaxies of the overdensity, including the central radio galaxy, are AGN, and AGN.1317 is one of them. Magrini et al. (2012, hereafter M12) have presented near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopic observations of AGN.1317, obtained with the Large Binocular Telescope (LBT). The galaxy AGN.1317 belongs to Group1 having a redshift z = 1.4162 (G10, see Table 1) and it is located in the neighbourhood of the central radio galaxy with a projected distance from it of ~780 kpc (see Fig. 1). Among the photometrically studied AGN, AGN.1317 is the brightest one (B = 20.16, G10). Its NIR spectrum shows clear broad features, such as Hα and Hβ, associated with the broad-line region, and several forbidden lines, such as the [O iii], [N ii], and [S ii] doublets, associated with the AGN narrow-line region and/or with the host star-forming galaxy. Moreover, the [O iii] lines show a clear asymmetric profile with prominent blue-shifted wings, signature of a strong gas outflow (v > 1000 km s-1) possibly driven by the AGN radiation pressure. The prominent NIR emission of AGN.1317 (FHα(narrow) = 2.8 × 10-16 erg cm-2 s and FHα(broad) = 9.7 × 10-16 erg cm-2 s, M12) makes this galaxy an excellent candidate for CO detection in a galaxy cluster at such high redshift.

The galaxy overdensity around 7C 1756+6520 was observed in radio-cm continuum (e.g., 74 MHz: Cohen et al. 2007; 1.4 GHz: Condon et al. 1998; 4.8 GHz: Becker et al. 1991), but the low spatial resolution of these observations (~45–80′′) did not allow AGN.1317 to be resolved. On the other hand, the only high spatial resolution (1 5) observations did not reach the sensitivity needed to detect AGN.1317 (4.8 GHz: Lacy et al. 1992). The main characteristics of AGN.1317 and of the overdensity of galaxies associated with 7C 1756+6520 are collected in Table 1.

5) observations did not reach the sensitivity needed to detect AGN.1317 (4.8 GHz: Lacy et al. 1992). The main characteristics of AGN.1317 and of the overdensity of galaxies associated with 7C 1756+6520 are collected in Table 1.

3. Observations

We observed AGN.1317 with the IRAM PdBI (six antennas) in the compact C configuration of the array on November 22, 23, 2012. We tuned the receivers to 95.4135 GHz (~3 mm), the frequency of the 12CO(2−1) emission line (230.538 GHz) at redshift z = 1.4162. The spectral setup used during observations provides a velocity coverage of ~3000 km s-1 (i.e. ~1 GHz). A total time of 8 hours were spent on-source and the observing conditions were excellent in terms of atmospheric phase stability (PWV < 2 mm). Typical system temperatures were around 75−110 K during the observations. The radio source 2200+420 was used for bandpass calibration, 1849+670 for flux calibration, and 1716+686 for phase and amplitude calibrations.

The data were reduced and analysed with the IRAM/GILDAS1 software (Guilloteau & Lucas 2000). Data cubes with 256 × 256 pixels (0 2 pixel-1) were created over the velocity interval of ~3000 km s-1 in bins of ~60 km s-1. The half power primary beam (field of view) is ~53′′ at the observed frequency. The image presented here was reconstructed with natural weighting and restored with a Gaussian beam of dimensions 4

2 pixel-1) were created over the velocity interval of ~3000 km s-1 in bins of ~60 km s-1. The half power primary beam (field of view) is ~53′′ at the observed frequency. The image presented here was reconstructed with natural weighting and restored with a Gaussian beam of dimensions 4 73 × 2

73 × 2 33 (~40 kpc × 20 kpc) and PA = 147°. In the cleaned map, the rms level is 0.27 mJy beam-1 at a velocity resolution of ~60 km s-1. At a level of 3σ, no 3 mm continuum was detected toward AGN.1317 down to an rms noise level of 0.04 mJy beam-1. The conversion factor between intensity and brightness temperature is 11 K (Jy beam-1)-1 at 95.4135 GHz. Since AGN.1317 is at the centre of the image, the map presented here is not corrected for primary beam attenuation.

33 (~40 kpc × 20 kpc) and PA = 147°. In the cleaned map, the rms level is 0.27 mJy beam-1 at a velocity resolution of ~60 km s-1. At a level of 3σ, no 3 mm continuum was detected toward AGN.1317 down to an rms noise level of 0.04 mJy beam-1. The conversion factor between intensity and brightness temperature is 11 K (Jy beam-1)-1 at 95.4135 GHz. Since AGN.1317 is at the centre of the image, the map presented here is not corrected for primary beam attenuation.

|

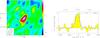

Fig. 2 Left panel: 12CO(2−1) intensity map obtained with the IRAM PdBI toward AGN.1317. The color wedge of the intensity map is in Jy beam-1 km s-1. The black cross marks the coordinates of the phase tracking centre of our observations (see Table 1). The rms noise level is σ = 0.07 Jy beam-1 km s-1 and contour levels run from 3σ to 7σ with 1σ spacing. In this map a velocity range of ~360 km s-1 is used. The beam of 4 |

Results from IRAM PdBI observations for AGN.1317.

4. Results

We clearly detected the 12CO(2−1) emission line in AGN.1317. Figure 2 shows the 12CO(2–1) intensity map (left panel) and spectrum of AGN.1317 (right panel). The intensity map was obtained by integrating the line over a velocity range of ~360 km s-1, i.e. covering the line emission at − 171 < v < 193 km s-1. The detection is at ~8σ, but the spatial resolution does not allow the galaxy CO emission to be resolved, which is therefore point-like in our observations.

Table 2 gives the main parameters derived from our 12CO(2−1) detection in AGN.1317. The Gaussian fit applied to the 12CO(2−1) spectrum (right panel of Fig. 2, blue curve) shows that the molecular gas emission is blue-shifted by ~61 km s-1 with respect to the optical emission (v = 0 km s-1 at z = 1.4162, G10). Observations from IRAM PdBI led to a redshift determination of z = 1.4161 ± 0.0001 consistent with z = 1.4162 ± 0.0005 from G10 and almost consistent with z = 1.4168 ± 0.0005 from M12 (see Tables 1 and 2). The 12CO(2–1) line width is of ~250 km s-1, in agreement both with those typical for field galaxies at redshifts similar to AGN.1317 (e.g. Daddi et al. 2010; Tacconi et al. 2010) and for intermediate redshift cluster galaxies (e.g. Geach et al. 2009, 2011; Jablonka et al. 2013).

We calculated  (=

(=  ) from the 12CO(2−1) integrated line emission according to Solomon & Vanden Bout (2005),

) from the 12CO(2−1) integrated line emission according to Solomon & Vanden Bout (2005),  SCOΔvνobs-2 (1 + z)-3

SCOΔvνobs-2 (1 + z)-3 in K km s-1 pc2, where SCOΔv is the total velocity integrated line flux in Jy km s-1, νobs the observed frequency in GHz, z the redshift of the source, and DL the luminosity distance in Mpc. To compute

in K km s-1 pc2, where SCOΔv is the total velocity integrated line flux in Jy km s-1, νobs the observed frequency in GHz, z the redshift of the source, and DL the luminosity distance in Mpc. To compute  , we assumed a ratio of 1 between the 12CO(2−1) and 12CO(1−0) luminosities, as expected for a thermalized optically thick CO emission. Based on these assumptions, AGN.1317 has

, we assumed a ratio of 1 between the 12CO(2−1) and 12CO(1−0) luminosities, as expected for a thermalized optically thick CO emission. Based on these assumptions, AGN.1317 has  K km s-1 pc2, compatible with CO luminosities of z ≳ 1 galaxies both in cluster (Wagg et al. 2012a) and in field (e.g. Daddi et al. 2010; Tacconi et al. 2010).

K km s-1 pc2, compatible with CO luminosities of z ≳ 1 galaxies both in cluster (Wagg et al. 2012a) and in field (e.g. Daddi et al. 2010; Tacconi et al. 2010).

It is well established that the CO luminosity linearly traces the molecular gas mass,  , where M(H2) is defined to include the mass of He so that M(H2) = Mgas (e.g. Young & Scoville 1991; Solomon & Vanden Bout 2005). The conversion factor α varies from α = 4.6 M⊙ (K km s-1 pc2)-1 for our Galaxy and normal spirals to α = 0.8 M⊙ (K km s-1 pc2)-1 for ultra-luminous infrared galaxies (ULIRGs, LFIR > 1012L⊙). Since LFIR of AGN.1317 is unknown, we adopted the more conservative ULIRG conversion when estimating H2 mass. We obtained a value of M(H2) ~ 1010M⊙. We notice that the α conversion factor depends on various terms, such as the excitation temperature of the CO, the density of the gas, the gas metallicity, the cosmic ray density, and the ultraviolet radiation field (e.g. Maloney & Black 1988; Boselli et al. 2002; Magrini et al. 2011). This dependence inevitably introduces a degree of uncertainty in the H2 mass estimation and therefore in all parameters involving the gas mass. The assumption of a Galactic conversion would increase our mass estimate by a factor ~6. In this sense, treating AGN.1317 as an ULIRG in terms of H2 mass, makes our H2 mass estimation a lower limit. Despite our very conservative assumption regarding the CO-to-H2 conversion factor, we found that AGN.1317 has a substantial reservoir of molecular gas. This is consistent with what has been observed in the one and only CO detection from a z ~ 1 AGN in a cluster (Wagg et al. 2012a). Similar gas contents are also found in high redshift massive objects, such as the bright, field submillimeter galaxies (SMGs) at z ~ 1−3.5 (Greve et al. 2005) and the colour-selected star-forming galaxies at z ~ 1.5−3 (see Carilli & Walter 2013, for a review).

, where M(H2) is defined to include the mass of He so that M(H2) = Mgas (e.g. Young & Scoville 1991; Solomon & Vanden Bout 2005). The conversion factor α varies from α = 4.6 M⊙ (K km s-1 pc2)-1 for our Galaxy and normal spirals to α = 0.8 M⊙ (K km s-1 pc2)-1 for ultra-luminous infrared galaxies (ULIRGs, LFIR > 1012L⊙). Since LFIR of AGN.1317 is unknown, we adopted the more conservative ULIRG conversion when estimating H2 mass. We obtained a value of M(H2) ~ 1010M⊙. We notice that the α conversion factor depends on various terms, such as the excitation temperature of the CO, the density of the gas, the gas metallicity, the cosmic ray density, and the ultraviolet radiation field (e.g. Maloney & Black 1988; Boselli et al. 2002; Magrini et al. 2011). This dependence inevitably introduces a degree of uncertainty in the H2 mass estimation and therefore in all parameters involving the gas mass. The assumption of a Galactic conversion would increase our mass estimate by a factor ~6. In this sense, treating AGN.1317 as an ULIRG in terms of H2 mass, makes our H2 mass estimation a lower limit. Despite our very conservative assumption regarding the CO-to-H2 conversion factor, we found that AGN.1317 has a substantial reservoir of molecular gas. This is consistent with what has been observed in the one and only CO detection from a z ~ 1 AGN in a cluster (Wagg et al. 2012a). Similar gas contents are also found in high redshift massive objects, such as the bright, field submillimeter galaxies (SMGs) at z ~ 1−3.5 (Greve et al. 2005) and the colour-selected star-forming galaxies at z ~ 1.5−3 (see Carilli & Walter 2013, for a review).

5. The origin and fate of molecular gas in AGN.1317

As shown in the previous section, our IRAM PdBI observations led to the finding that AGN.1317 possesses a substantial molecular gas reservoir. Using information from our new dataset and from multi-band observations of the overdensity, which were already available in the literature, we are able to make hypotheses on the origin of the gas in AGN.1317. In a dense environment, such as a galaxy cluster, a non-negligible amount of gas evokes a merging scenario where a gas fraction might originate from satellites of AGN.1317 and/or from the inter-galactic medium. However, optical images of the cluster show that AGN.1317 is apparently quite isolated within Group1 (Fig. 1) and, therefore, without nearby companions that survived and from which it could have stripped gas. Moreover, the 12CO(2–1) line width of ~250 km s-1 in AGN.1317 is narrow if compared with the broad CO profiles in high-z merging systems, with line-widths up to 1000 − 1500 km s-1 (e.g. De Breuck et al. 2005; Salomé et al. 2012; Emonts et al. 2013; Feruglio et al. 2013). Therefore, we can reasonably exclude recent episodes of merging to be the cause of the quantity of gas in AGN.1317. The substantial amount of gas is more likely an intrinsic characteristic of the AGN due to the early phase of its evolution, when most of its baryonic mass was in gas phase.

Using the spectroscopic NIR information, we are able to derive the current SFR in AGN.1317. The narrow and broad Hα fluxes are both available in M12. As a first order approximation, we have assumed that most of the narrow Hα flux is originated by SF, giving thus a probe of the young (lifetimes <20 Myr), massive (M > 10 M⊙) stellar population, instead of the AGN activity. The use of the narrow component is also supported by the location of the AGN flux ratios in the diagnostic Baldwin-Phillips-Terlevich (BPT) diagrams (Baldwin et al. 1981). Using the original spectra of AGN.1317 from M12, we measured the narrow component of [O iii]5007 and Hβ, not available in Table 2 of M12, obtaining log ([O iii]5007/Hβ) ~ 0.11. With the fluxes of the narrow Hα, [N ii]6584, and [S ii]6716,6731, we obtained log ([N ii]6584/Hα) ~ −0.48 and log ([S ii]6716,6731/Hα) ~ − 0.63. These flux ratios locate AGN.1317 in the starburst region of BPT diagrams from Wang & Wei (2008). We corrected the Hα flux for extinction using cβ = 0.58 calculated from the ratio of Hα and Hβ given in M12. Since Hβ flux is not calibrated in M12, we re-normalized the continuum of the J-band spectrum to the value of the continuum in the H-band spectrum, obtaining a narrow component of the Hβ line of ~6 × 10-17 erg cm-2 s-1. We have therefore estimated the nearly instantaneous SFR in AGN.1317 using the calibration of Kennicutt (1998), SFR[M⊙ yr-1] = 7.9 × 10-42L(Hα) [erg s-1]. We obtained a SFR ~ 65 M⊙ yr-1, comparable with the most massive galaxies in the overdensity (M12). This relatively high SFR value indicates that AGN.1317 is actively forming stars and is therefore consuming its reservoir of molecular gas.

Assuming that all H2 is available to sustain the SFR and that the SFR continues at the current rate, we derive a minimum mass depletion time-scale of tdepl = MH2/SFR ≈ 0.2 Gyr comparable to the values (~0.5 Gyr) obtained by Daddi et al. (2010) for very massive z = 1.5 disc galaxies. This tdepl is obtained treating AGN.1317 as an ULIRG, while assuming the Galactic α value in the gas mass computation tdepl is of ≈1.0 Gyr.

Summarising, AGN.1317 i) exhibits a large quantity of molecular gas; ii) has a current SFR comparable with the most massive galaxies in the overdensity; and iii) maintaining the current SFR, it will consume the molecular gas in about 0.2−1.0 Gyr.

6. Conclusions

We have presented a new IRAM PdBI CO detection in AGN.1317, a source belonging to a galaxy cluster at z ~ 1.4 and located nearby the centre of the cluster. Such CO detections in high-z clusters are rare. From the 12CO(2−1) line luminosity, we measured H2 mass of 1.1 × 1010M⊙, comparable to that in massive SMGs. The optical images of the cluster show that AGN.1317 is an isolated object, and thus its gas mass might be an intrinsic characteristic associated with its early evolutionary phase, when most of its baryonic mass was in gas phase, than due to a merger episode with nearby companions. The inferred gas mass assumes the CO-to-H2 conversion factor adapted for ULIRGs; if we adopt the Galactic conversion factor, this estimate would increase by a factor of ~6. The Hα-derived SFR is ~65 M⊙ yr-1, and so AGN.1317 would exhaust its reservoir of cold gas in ~0.2−1.0 Gyr. This relatively high molecular gas content and SFR for an AGN near the centre of a young cluster is compatible with models of evolution of galaxy clusters that predict high SFR at the epoch of their formation, i.e. z ~ 1.5. Following the predictions of these models, at z ~ 1, the SFR would rapidly be quenched through environmental effects starting from the innermost regions of clusters.

Acknowledgments

We thank the anonymous referee for useful comments and suggestions which improved the quality of the manuscript. We also thank the IRAM PdBI staff for help provided during observations and data reduction. The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Commission Seventh Framework Programme (FP/2007−2013) under grant agreement No. 283393 (RadioNet3). This research has made use of the NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database (NED). We thank A. Galametz for making available the B-band image of the field around the radio galaxy 7C 1756+6520. We particularly thank Jacopo Fritz for reading the manuscript and very useful advice.

References

- Arnaud, M. 2009, A&A, 500, 103 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, J. A., Phillips, M. M., & Terlevich, R. 1981, PASP, 93, 5 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, A. E., Grützbauch, R., Jørgensen, I., Varela, J., & Bergmann, M. 2011, MNRAS, 411, 2009 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bekki, K., Couch, W. J., & Shioya, Y. 2002, ApJ, 577, 651 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Boselli, A., Lequeux, J., & Gavazzi, G. 2002, Ap&SS, 281, 127 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Carilli, C., & Walter, F. 2013, ARA&A, 51, 105 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Cen, R., & Zheng, Z. 2013, ApJ, 775, 112 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, S. C., Scott, D., Windhorst, R. A., et al. 2004, ApJ, 606, 85 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, M. C., Newman, J. A., Weiner, B. J., et al. 2008, MNRAS, 383, 1058 [Google Scholar]

- Daddi, E., Bournaud, F., Walter, F., et al. 2010, ApJ, 713, 686 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- De Breuck, C., Downes, D., Neri, R., et al. 2005, A&A, 430, L1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Elbaz, D., Daddi, E., Le Borgne, D., et al. 2007, A&A, 468, 33 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Ellingson, E., Lin, H., Yee, H. K. C., & Carlberg, R. G. 2001, ApJ, 547, 609 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Emonts, B. H. C., Feain, I., Roettgering, H. J. A., et al. 2013, MNRAS, 430, 3465 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Feruglio, C., Fiore, F., Maiolino, R., et al. 2013, A&A, 549, A51 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Galametz, A., De Breuck, C., Vernet, J., et al. 2009, A&A, 507, 131 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Galametz, A., Stern, D., Stanford, S. A., et al. 2010, A&A, 516, A101 (G10) [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Geach, J. E., Smail, I., Coppin, K., et al. 2009, MNRAS, 395, L62 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Geach, J. E., Smail, I., Moran, S. M., et al. 2011, ApJ, 730, L19 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, P. L., Nichol, R. C., Miller, C. J., et al. 2003, ApJ, 584, 210 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Greve, T. R., Bertoldi, F., Smail, I., et al. 2005, MNRAS, 359, 1165 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Grützbauch, R., Bauer, A. E., Jørgensen, I., & Varela, J. 2012, MNRAS, 423, 3652 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Guilloteau, S., & Lucas, R. 2000, Imaging at Radio through Submillimeter Wavelengths, 217, 299 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn, J. E., & Gott, J. R., III 1972, ApJ, 176, 1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Haines, C. P., Smith, G. P., Pereira, M. J., et al. 2010, A&A, 518, L19 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto, Y., Oemler, A., Jr., Lin, H., & Tucker, D. L. 1998, ApJ, 499, 589 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton, M., Lloyd-Davies, E., Stanford, S. A., et al. 2010, ApJ, 718, 133 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Jablonka, P., Combes, F., et al. 2013, A&A, 557, A103 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Kennicutt, R. C., Jr. 1998, ApJ, 498, 541 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lacy, M., Rawlings, S., & Warner, P. J. 1992, MNRAS, 256, 404 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Larson, R. B., Tinsley, B. M., & Caldwell, C. N. 1980, ApJ, 237, 692 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Magrini, L., Bianchi, S., Corbelli, E., et al. 2011, A&A, 535, A13 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Magrini, L., Sommariva, V., Cresci, G., et al. 2012, MNRAS, 426, 1195 (M12) [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney, P., & Black, J. H. 1988, ApJ, 325, 389 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Martig, M., & Bournaud, F. 2008, MNRAS, 385, L38 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Martini, P., Sivakoff, G. R., & Mulchaey, J. S. 2009, ApJ, 701, 66 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Martini, P., Miller, E. D., Brodwin, M., et al. 2013, ApJ, 768, 1 [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda, Y., Iono, D., Ohta, K., et al. 2007, ApJ, 667, 667 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Patel, S. G., Holden, B. P., Kelson, D. D., Illingworth, G. D., & Franx, M. 2009, ApJ, 705, L67 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Salomé, P., Guélin, M., Downes, D., et al. 2012, A&A, 545, A57 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, P. M., & Van den Bout, P. A. 2005, ARA&A, 43, 677 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Strazzullo, V., Rosati, P., Pannella, M., et al. 2010, A&A, 524, A17 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Tacconi, L. J., Genzel, R., Neri, R., et al. 2010, Nature, 463, 781 [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, Y., Kohno, K., Nakanishi, K., et al. 2009, Nature, 459, 61 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taranu, D. S., Hudson, M. J., Balogh, M. L., et al. 2012, MNRAS, submitted [arXiv:1211.3411] [Google Scholar]

- Tran, K.-V. H., Papovich, C., Saintonge, A., et al. 2010, ApJ, 719, L126 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Venemans, B. P., McMahon, R. G., Walter, F., et al. 2012, ApJ, 751, L25 [Google Scholar]

- Wagg, J., & Kanekar, N. 2012, ApJ, 751, L24 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wagg, J., Pope, A., Alberts, S., et al. 2012a, ApJ, 752, 91 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wagg, J., Wiklind, T., Carilli, C. L., et al. 2012b, ApJ, 752, L30 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J., & Wei, J. Y. 2008, ApJ, 679, 86 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wetzel, A. R., Tinker, J. L., Conroy, C., & van den Bosch, F. C. 2013, MNRAS, 432, 336 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y., Decarli, R., Dannerbauer, H., et al. 2012, ApJ, 744, 178 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Young, J. S., & Scoville, N. Z. 1991, ARA&A, 29, 581 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

All Tables

Fundamental characteristics of the overdensity of galaxies associated with 7C 1756+6520 and of AGN.1317.

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Location of the galaxies belonging to Group1 (z ~ 1.42) and Group2 (z ~ 1.44) in the B-band image (NOAO). Galaxies of Group1 are represented by red circles, while those of Group2 by blue triangles. The central radio galaxy 7C 1756+6520 is the red star and belongs to Group1. North is at the top and east to the left. The field of view is ~500′′ × 200′′ centred on the radio galaxy. 1′′ corresponds to ~8.4 kpc. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Left panel: 12CO(2−1) intensity map obtained with the IRAM PdBI toward AGN.1317. The color wedge of the intensity map is in Jy beam-1 km s-1. The black cross marks the coordinates of the phase tracking centre of our observations (see Table 1). The rms noise level is σ = 0.07 Jy beam-1 km s-1 and contour levels run from 3σ to 7σ with 1σ spacing. In this map a velocity range of ~360 km s-1 is used. The beam of 4 |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.