| Issue |

A&A

Volume 553, May 2013

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A55 | |

| Number of page(s) | 7 | |

| Section | The Sun | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201321098 | |

| Published online | 01 May 2013 | |

Three-dimensional magnetohydrodynamic simulation of the solar magnetic flux emergence

Parametric study on the horizontal divergent flow

Department of Earth and Planetary Science, University of Tokyo, 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, 113-0033 Tokyo, Japan

e-mail: toriumi@eps.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp

Received: 14 January 2013

Accepted: 19 March 2013

Context. Solar active regions are formed through the emergence of magnetic flux from the deeper convection zone. Recent satellite observations have shown that a horizontal divergent flow (HDF) stretches out over the solar surface just before the magnetic flux appearance.

Aims. The aims of this study are to investigate the driver of the HDF and to see the dependency of the HDF on the parameters of the magnetic flux in the convection zone.

Methods. We conducted three-dimensional magnetohydrodynamic (3D MHD) numerical simulations of the magnetic flux emergence and varied the parameters in the initial conditions. An analytical approach was also taken to explain the dependency.

Results. The horizontal gas pressure gradient is found to be the main driver of the HDF. The maximum HDF speed shows positive correlations with the field strength and twist intensity. The HDF duration has a weak relation with the twist, while it shows negative dependency on the field strength only in the case of the stronger field regime.

Conclusions. Parametric dependencies analyzed in this study may allow us to probe the structure of the subsurface magnetic flux by observing properties of the HDF.

Key words: sunspots / Sun: interior / Sun: photosphere / Sun: chromosphere / Sun: corona

© ESO, 2013

1. Introduction

The dynamics of the rising magnetic flux and the formation process of solar active regions have been widely investigated through a series of analytical and numerical studies. Parker (1975) first calculated the rising speed of a flux tube in the convection zone (CZ) by considering a force balance between the magnetic buoyancy and the aerodynamic drag acting on the flux tube, while Schüssler (1979) simulated a buoyant emergence of a flux tube in the CZ in a two-dimensional (2D) scheme. Moreno-Insertis & Emonet (1996) and Emonet & Moreno-Insertis (1998) investigated the dependency of the rising tube on the initial twist intensity and found that the tube needs a certain degree of twist to hold its coherency. After Shibata et al. (1989) and Magara (2001) conducted 2D simulations of flux emergence from the surface layer into the corona, 3D simulations have been carried out by, among others, Fan (2001) and Archontis et al. (2004). Murray et al. (2006) simulated other 3D flux emergences of this kind and surveyed the tube’s dependency on the initial field strength and twist intensity.

Recently, Toriumi & Yokoyama (2010, 2011, 2012) combined the CZ, the photosphere/chromosphere, and the corona into a single computational domain and simulated magnetic flux emergence from a deeper CZ both in 2D and 3D. As a result, the initial flux placed at a depth of − 20 Mm starts its emergence in the solar interior, which then slows down gradually in the uppermost CZ. This is because the plasma pushed up by the emerging flux rises to the isothermally-stratified (i.e., convectively-stable) surface layer and is then trapped and compressed between them, which, in turn, suppresses the rising flux from below. Such compressed plasma will escape laterally around the photospheric layer from the rising flux as a horizontal divergent flow (HDF), just before the flux itself reaches the surface. Using SDO/HMI data, Toriumi et al. (2012) observed the emerging active region located away from the solar disk center and found the HDF in the Dopplergram, up to about 100 min before the start of the flux emergence.

In the present study, we report the results of the parametric survey of the 3D magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) flux emergence simulation. The aims of this study are to investigate which force drives the HDF and to observe the dependence of the HDF on the parameters in the simulation. One important feature of this HDF study is that it can be a probe for exploring the physical state of the magnetic field in the upper CZ. That is, we may be able to obtain valuable information on the subsurface layers from the direct optical observation at the surface. Therefore, in this numerical study, we vary the parameters of the initial flux tube, and then check the characteristics of the consequent HDF seen at the surface layer.

In the next section we introduce the basic setup of the numerical calculation. In Sect. 3 we show the results of the parametric survey, and in Sect. 4 we provide some analytic explanations of the results. We finally summarize the paper in Sect. 5.

2. Numerical setup

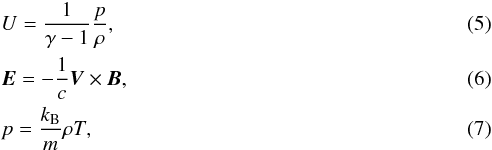

The basic MHD equations, normalizing units, computational domain size, grid spacings, boundary conditions, and background stratification are the same as those in Toriumi & Yokoyama (2012). The MHD equations in vector form are ![\begin{eqnarray} && \frac{\partial\rho}{\partial t} + \bm{\nabla} \cdot(\rho\bm{V})=0, \\ && \frac{\partial}{\partial t} (\rho\bm{V}) + \bm{\nabla}\cdot \left( \rho\bm{V}\bm{V} +p\bm{I} -\frac{\bm{BB}}{4\pi} +\frac{\bm{B}^{2}}{8\pi}\bm{I} \right) -\rho\bm{g}=0, \\ && \frac{\partial\bm{B}} {\partial t} = \bm{\nabla} \times (\bm{V}\times\bm{B}), \\ &&\frac{\partial}{\partial t} \left( \rho U + \frac{1}{2}\rho\bm{V}^{2} + \frac{\bm{B}^{2}}{8\pi} \right) \nonumber \\ &&+\bm{\nabla}\cdot \left[ \left( \rho U + p + \frac{1}{2}\rho\bm{V}^{2} \right) \bm{V} + \frac{c}{4\pi} \bm{E}\times\bm{B} \right] -\rho\bm{g}\cdot\bm{V} =0, \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/05/aa21098-13/aa21098-13-eq2.png) and

and  where ρ denotes the gas density, V velocity vector, p pressure, B magnetic field, c the speed of light, E electric field, and T temperature, while U is the internal energy per unit mass, I the unit tensor, kB the Boltzmann constant, m( =const.) the mean molecular mass, and g the uniform gravitational acceleration. We assume the medium to be an inviscid perfect gas with a specific heat ratio γ = 5/3. All the physical values are normalized by the pressure scale height H0 = 200 km for length, the sound speed Cs0 = 8 km s-1 for velocity, τ0 ≡ H0/Cs0 = 25 s for time, and ρ0 = 1.4 × 10-7 g cm-3 for density, all of which are the typical values in the photosphere. The units for pressure, temperature, and magnetic field strength are p0 = 9.0 × 104 dyn cm-2, T0 = 4000 K, and B0 = 300 G, respectively.

where ρ denotes the gas density, V velocity vector, p pressure, B magnetic field, c the speed of light, E electric field, and T temperature, while U is the internal energy per unit mass, I the unit tensor, kB the Boltzmann constant, m( =const.) the mean molecular mass, and g the uniform gravitational acceleration. We assume the medium to be an inviscid perfect gas with a specific heat ratio γ = 5/3. All the physical values are normalized by the pressure scale height H0 = 200 km for length, the sound speed Cs0 = 8 km s-1 for velocity, τ0 ≡ H0/Cs0 = 25 s for time, and ρ0 = 1.4 × 10-7 g cm-3 for density, all of which are the typical values in the photosphere. The units for pressure, temperature, and magnetic field strength are p0 = 9.0 × 104 dyn cm-2, T0 = 4000 K, and B0 = 300 G, respectively.

Here, 3D Cartesian coordinates (x,y,z) are used, where z is parallel to the gravitational acceleration vector, g, and  by definition. The simulation domain is (− 400, − 200, − 200) ≤ (x/H0,y/H0,z/H0) ≤ (400,200,250), resolved by 1602 × 256 × 1024 grids. In the x-direction, the mesh size is Δx/H0 = 0.5 (uniform). In the y-direction (z-direction), the mesh size is Δy/H0 = 0.5 (Δz/H0 = 0.2) in the central area of the domain, which gradually increases for each direction. We assume periodic boundaries for both horizontal directions and symmetric boundaries for the vertical direction.

by definition. The simulation domain is (− 400, − 200, − 200) ≤ (x/H0,y/H0,z/H0) ≤ (400,200,250), resolved by 1602 × 256 × 1024 grids. In the x-direction, the mesh size is Δx/H0 = 0.5 (uniform). In the y-direction (z-direction), the mesh size is Δy/H0 = 0.5 (Δz/H0 = 0.2) in the central area of the domain, which gradually increases for each direction. We assume periodic boundaries for both horizontal directions and symmetric boundaries for the vertical direction.

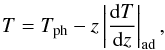

The background atmosphere consists of three different layers. From the bottom, the layers are the adiabatically stratified CZ, the cool isothermal photosphere/chromosphere, and the hot isothermal corona. The stratification in the CZ (z/H0 < 0) is given as  (8)where Tph/T0 = 1 is the respective temperature in the photosphere/chromosphere and

(8)where Tph/T0 = 1 is the respective temperature in the photosphere/chromosphere and  (9)is the adiabatic temperature gradient. The profile above the surface is

(9)is the adiabatic temperature gradient. The profile above the surface is ![\begin{eqnarray} T(z)=T_{\rm ph}+\frac{1}{2}(T_{\rm cor}-T_{\rm ph}) \left\{ \tanh{ \left[ \frac{z-z_{\rm cor}}{w_{\rm tr}} \right] +1 } \right\}, \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/05/aa21098-13/aa21098-13-eq37.png) (10)where Tcor/T0 = 100 is the temperature in the corona, zcor/H0 = 10 is the base of the corona, and wtr/H0 = 0.5 is the transition scale length. Based on the temperature distribution above, the pressure and density profiles are defined by the equation of static pressure balance

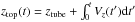

(10)where Tcor/T0 = 100 is the temperature in the corona, zcor/H0 = 10 is the base of the corona, and wtr/H0 = 0.5 is the transition scale length. Based on the temperature distribution above, the pressure and density profiles are defined by the equation of static pressure balance  (11)The initial flux tube is embedded in the CZ at ztube/H0 = −100, i.e., ztube = −20 Mm, of which the axial and azimuthal profiles are given as

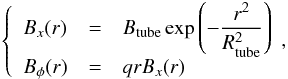

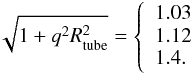

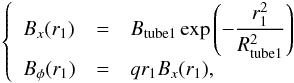

(11)The initial flux tube is embedded in the CZ at ztube/H0 = −100, i.e., ztube = −20 Mm, of which the axial and azimuthal profiles are given as  (12)respectively, where Btube is the axial field strength, r the radial distance from the tube’s center (ytube/H0,ztube/H0) = (0, − 100), Rtube the typical radial size, and q the twist intensity. For the pressure balance between the field and the plasma, the pressure distribution inside the tube is defined as pi = p(z) + δpexc (the subscript i denotes inside the tube), where the pressure excess δpexc(<0) is described as

(12)respectively, where Btube is the axial field strength, r the radial distance from the tube’s center (ytube/H0,ztube/H0) = (0, − 100), Rtube the typical radial size, and q the twist intensity. For the pressure balance between the field and the plasma, the pressure distribution inside the tube is defined as pi = p(z) + δpexc (the subscript i denotes inside the tube), where the pressure excess δpexc(<0) is described as ![\begin{eqnarray} \delta p_{\rm exc} = \frac{B_{x}^{2}(r)}{8\pi} \left[ q^{2} \left( \frac{R_{\rm tube}^{2}}{2} -r^{2} \right) -1 \right]. \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/05/aa21098-13/aa21098-13-eq52.png) (13)The density inside the tube is also defined as ρi = ρ(z) + δρexc, where

(13)The density inside the tube is also defined as ρi = ρ(z) + δρexc, where  (14)and λ is the perturbation wavelength. That is, the middle of the tube, x/H0 = 0, is in thermal equilibrium with external media and is most buoyant. The buoyancy decreases as | x | /H0 increases.

(14)and λ is the perturbation wavelength. That is, the middle of the tube, x/H0 = 0, is in thermal equilibrium with external media and is most buoyant. The buoyancy decreases as | x | /H0 increases.

Summary of the simulation cases.

The parameters we varied are the field strength Btube, the twist q, and the perturbation wavelength λ. Table 1 summarizes the cases in this study. The case simulated in Toriumi & Yokoyama (2012) is named here as case A, while cases B–F are for different field strength, twist, and wavelength from those of A. Here we fixed the tube’s radial size at Rtube/H0 = 5 for all the cases. It should be noted that the critical twist for the kink instability is qH0 = 0.2 (Linton et al. 1996). Therefore, all the tubes examined here are stable or, at least, marginally stable against the instability at the beginning of the calculation.

3. Simulation results

3.1. General evolution

|

Fig. 1 Height-time evolution of the flux tube. a) Cases for different Btube. b) Cases for different q. c) Cases for different λ. |

|

Fig. 2 Total magnetic field strength of the initial condition for case A and the final states for cases A to G, plotted over the range − 400 ≤ x/H0 ≤ 0 and 0 ≤ y/H0 ≤ 200. |

Figure 1 shows the temporal evolution of the apex of the rising tube, ztop(t). In Fig. 2, we plot the total field strength log 10( | B | /B0) of the initial condition for case A and the final states for all the cases. As can be seen in Fig. 1a, it is clear that the tubes with stronger field Btube rise faster. The rising speed of each tube in the CZ is in simple proportion to the initial field strength, which is well in accordance with Murray et al. (2006) and other previous studies. Case A, which has a middle field strength, shows deceleration just before it reaches the surface. This deceleration is the result of the plasma accumulation, which is caused by the trapping of material between the rising tube and the isothermally-stratified photosphere above the tube. After a while, the tube then starts further emergence into the atmosphere (see the top panels in Fig. 2). As for the strongest case in B, the accumulation becomes less marked, and thus the tube almost directly passes through the surface layer and expands into the higher corona, without undergoing strong deceleration (Fig. 2B). When the field is very weak, as in case C, the tube stops its emergence halfway to the surface, since the tube’s buoyancy is not strong enough to continue its emergence (Fig. 2C).

Figure 1b shows the evolution with different twist q. In this figure, all three tubes are seen to rise almost at the same rate in the CZ, which is again consistent with previous studies (e.g., Murray et al. 2006). When the twist is weak and thus cannot hold the coherency (case E), the tube expands and suffers deformation by aerodynamic drag. As a result, the tube cannot maintain a strong enough magnetic field to continue its emergence (Fig. 2E).

Figure 1c compares three cases with different wavelengths of the initial perturbation. The initial wavelength is crucial for two factors, the curvature force (magnetic tension), which pulls down the rising tube, and the drainage of the internal media due to gravity, which encourages the emergence. When the wavelength is smaller, the curvature force is expected to be stronger, while the drainage becomes more effective. In Fig. 1c the rising velocities of cases A and F are almost the same, which indicates that both effects cancel each other out. However, the shortest wavelength tube (case G) shows a much slower emergence rate in the CZ, which indicates that the curvature force is more effective and slows down the emergence. For the emergence above the surface layer, on the contrary, Fig. 1c shows an exactly opposite trend that the rising is much faster when the wavelength is shortest (case G). In Fig. 2G, one can find that the main tube remains in the CZ at around z/H0 = −50, while the upper part has been detached from the main tube and has started the second-step emergence into the atmosphere. The reason for the rapid ascent may be that, in the shortest wavelength case (i.e., in the highly curved loops), the draining of the plasma from the apex is more effective, which helps the faster emergence above the photosphere.

3.2. Driver of the HDF

|

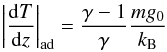

Fig. 3 a) Cross-sectional profile of the rising magnetic flux tube (case A). Plotted value is the logarithmic field strength log 10( | B | /B0) averaged over 6.5 ≤ x/H0 ≤ 13.5 at the time t/τ0 = 500. The color saturates at | B | /B0 = 1.0 (red) and − 4.0 (purple). b) Horizontal velocity Vy/Cs0 (thick solid line), pressure gradient − ∂p/∂y × (10H0/p0) (dashed line), and magnetic pressure gradient − ∂pm/∂y × (10H0/p0) (dash-dotted line), at t/τ0 = 500. c) Same as b) but for t/τ0 = 600. |

Figure 3a is the cross-sectional distribution of the field strength of Case A. The plotted value is the logarithmic field strength log 10( | B | /B0) averaged over 6.5 ≤ x/H0 ≤ 13.5, i.e., around x/H0 = 10. The reason we chose this x-range is to select one folded structure at the tube’s surface (see Fig. 3 of Toriumi & Yokoyama 2012). In this figure, there is a flow field in front of the rising flux tube, which is flowing from the apex to the flanks of the tube. One characteristic of this plasma layer is the horizontal divergent flow (HDF) that is seen at the solar surface just before the flux tube itself emerges.

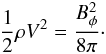

To investigate which force drives the HDF, in Figs. 3b and c, we plot the horizontal flow velocity Vy, pressure gradient − ∂p/∂y, and magnetic pressure gradient − ∂pm/∂y averaged over 6.5 ≤ x/H0 ≤ 13.5 and − 10 ≤ z/H0 ≤ 0, where pm = B2/(8π). Magnetic tension is not plotted here, since it is rather small compared to the two other forces. At t/τ0 = 500, before the tube reaches the uppermost CZ, z/H0 > − 10, the horizontal flow is clearly driven only by the gas pressure, and, of course, the magnetic pressure gradient is zero. Therefore, we can conclude that the HDF prior to the flux appearance is caused by the pressure gradient. This is consistent with other numerical simulations including thermal convection (Cheung et al. 2010). At t/τ0 = 600, the shallow layer is covered by the rising tube and the gas pressure gradient reverses its sign. Instead, the magnetic pressure gradient becomes dominant enough to drive the flow.

|

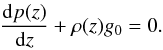

Fig. 4 a) Dependence of the HDF duration Δt on the field strength Btube, and b) on the twist q. c) Dependence of the maximum HDF speed max(Vy) on the field strength Btube, and d) on the twist q. In Panels a) and c) we also plot other field strength cases, indicated by smaller asterisks. Solid lines are the fitted curves: a) Δt/τ0 = 5.08 × 103/(Btube/B0) + 5.97 × 10, b) Δt/τ0 = −8.57 × (qH0) + 7.80 × 10; c) max(Vy)/Cs0 = 8.35 × 10-3 × (Btube/B0) − 3.26 × 10-1; and d) max(Vy)/Cs0 = 8.10 × 10-1 × (qH0) + 8.02 × 10-2. |

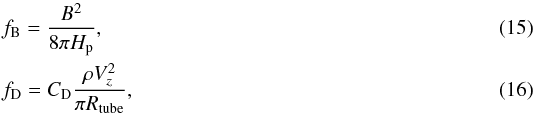

3.3. Dependence of the HDF

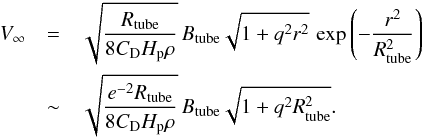

In this subsection, we show the dependence of the HDF on the initial field strength Btube and on the twist q. The investigated parameters are the duration of the HDF (from the HDF start to flux appearance) Δt/τ0 and the maximum HDF velocity max(Vy)/Cs0 during this time period. Here we defined the start time of the HDF as when the horizontal speed Vy in the horizontal range − 50 ≤ y/H0 ≤ 50, averaged over 6.5 ≤ x/H0 ≤ 13.5 and − 10 ≤ z/H0 ≤ 0, exceeds 0.06Cs( =0.5 km s-1) and the flux appearance as when the field strength | B | in this range exceeds 0.67B0( =200 G).

Figures 4a and 4b show the dependence of the duration on the field strength Btube and the twist q. Panel (a) is the comparison among the different field strength cases. A comparison of cases A and B, the middle and stronger field tubes, shows that the time duration is longer for the stronger field. If other stronger cases are considered (here we also plot two stronger tube cases other than A, B, and C), it may be found that the duration decreases with field strength. Thus, we can divide these cases into two groups, stronger cases that show a decreasing trend, which is fitted by a function of  , and a middle case that deviates from the decreasing trend. The weakest tube, case C, did not reach the surface. That is why the duration is 0 for case C. In contrast, in Panel (b), the duration is almost constant for the different twist cases.

, and a middle case that deviates from the decreasing trend. The weakest tube, case C, did not reach the surface. That is why the duration is 0 for case C. In contrast, in Panel (b), the duration is almost constant for the different twist cases.

Dependence of the maximum HDF speed max(Vy) is shown in Figs. 4c and d. Panel (c) indicates the positive linear correlation with the field strength Btube. Again, the speed of case B is plotted as zero, since it did not reach the surface. In Panel (a), we found a gap between the middle-field regime and the stronger-field regime. Thus, the linear fitting in Panel (c) might not reflect the actual trend. Nevertheless, the maximum speed basically increases with field strength. In Panel (d), we can see that the maximum HDF velocity is clearly proportional to the initial twist q.

4. Analytic explanation

In this section, the dependencies of the rising speed and of the HDF on the physical parameters obtained in Sect. 3 are analytically explained.

4.1. Rising speed

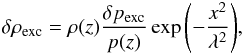

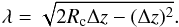

In Sect. 3.1, we found that the rising speed of the flux tube is proportional to the field strength Btube and the dependence on the twist q is significantly small. The curvature is effective for the flux tube with the shortest wavelength λ. Here we assume that the rising speed in the CZ is given as a terminal velocity where the buoyancy of the tube equals the aerodynamic drag by the surrounding flow field (Parker 1975; Moreno-Insertis & Emonet 1996) and the downward magnetic tension. Buoyancy, dynamic drag, and tension force acting on a unit cross-sectional area are written as  and

and  (17)respectively, where Hp = H0(T/T0) denotes the local pressure scale height, Vz the tube’s vertical speed, CD the drag coefficient of order unity, and Rc is the radius of curvature. The mechanical balance fB = fD + fT yields the terminal velocity

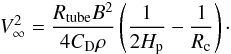

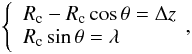

(17)respectively, where Hp = H0(T/T0) denotes the local pressure scale height, Vz the tube’s vertical speed, CD the drag coefficient of order unity, and Rc is the radius of curvature. The mechanical balance fB = fD + fT yields the terminal velocity  (18)First, let us discuss the curvature effect. In Eq. (18), the tension force is negligible for Rc → ∞, while the tension becomes effective when Rc ~ 2Hp. The relationship between the curvature radius Rc and the perturbation wavelength λ is illustrated in Fig. 5a. Here, we write the tube’s height as Δz = ztop(t) − ztube. From this figure, we have

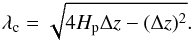

(18)First, let us discuss the curvature effect. In Eq. (18), the tension force is negligible for Rc → ∞, while the tension becomes effective when Rc ~ 2Hp. The relationship between the curvature radius Rc and the perturbation wavelength λ is illustrated in Fig. 5a. Here, we write the tube’s height as Δz = ztop(t) − ztube. From this figure, we have  (19)which gives

(19)which gives  (20)Thus, using the condition Rc ~ 2Hp, we obtain the critical wavelength for the tension to be effective

(20)Thus, using the condition Rc ~ 2Hp, we obtain the critical wavelength for the tension to be effective  (21)For instance, when the tube is halfway to the surface, i.e., ztop/H0 = −50 and thus Δz/H0 = 50, the local pressure scale height at this depth is Hp/H0 ~ 21. Therefore, the critical wavelength is evaluated to be λc ~ 41.2H0, and the flux tube with a wavelength smaller than this value will be resisted by the tension force, λ ≲ λc ~ 41.2H0. In Fig. 1c we found that only the tube with λ = 25H0 shows slower emergence because of the effective curvature force, which satisfies the condition λ ≲ λc.

(21)For instance, when the tube is halfway to the surface, i.e., ztop/H0 = −50 and thus Δz/H0 = 50, the local pressure scale height at this depth is Hp/H0 ~ 21. Therefore, the critical wavelength is evaluated to be λc ~ 41.2H0, and the flux tube with a wavelength smaller than this value will be resisted by the tension force, λ ≲ λc ~ 41.2H0. In Fig. 1c we found that only the tube with λ = 25H0 shows slower emergence because of the effective curvature force, which satisfies the condition λ ≲ λc.

Next, let us go on to the dependencies on the field strength and the twist, by considering Rc → ∞. Now Eq. (18), the terminal velocity, reduces to  (22)Here, in the first line we use Eq. (12) and in the second line we assume r ~ Rtube. From this equation we see that the rising velocity is in simple proportion to the initial field strength Btube when q is constant. If we change q considering Rtube = 5H0, for qH0 = [ 0.05,0.1,0.2 ], the third term in the right-hand side of Eq. (22) gives

(22)Here, in the first line we use Eq. (12) and in the second line we assume r ~ Rtube. From this equation we see that the rising velocity is in simple proportion to the initial field strength Btube when q is constant. If we change q considering Rtube = 5H0, for qH0 = [ 0.05,0.1,0.2 ], the third term in the right-hand side of Eq. (22) gives  (23)That is, the second term has only a weak positive correlation to the value of q. Therefore, the rising velocity of the flux tube is proportional to the field strength, while it is almost independent on the initial twist. The trend of the rising speed found in Sect. 3.1 is thus explained.

(23)That is, the second term has only a weak positive correlation to the value of q. Therefore, the rising velocity of the flux tube is proportional to the field strength, while it is almost independent on the initial twist. The trend of the rising speed found in Sect. 3.1 is thus explained.

We note here that if we substitute Hp ~ 40H0, ρ ~ 275ρ0 (values at ztube), Btube = 67B0, q = 0.1/H0, and Rtube = 5H0 (values for case A), and assume CD ~ 1 in Eq. (22), we obtain V∞ = 0.21Cs0, which is comparable to the simulation result ~0.17Cs0 (Fig. 1). This agreement indicates that Eq. (22) is a reasonable estimation of the tube’s rising speed (see also Parker 1975; Moreno-Insertis & Emonet 1996).

|

Fig. 5 a) Cross-section of the rising flux tube along the axis (in the x − z plane). b) Cross-section of the rising flux tube and the plasma layer ahead of the tube (in the y − z plane). |

4.2. Dependence on the twist

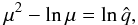

We found in Sect. 3.3 that when the twist q is varied while the field strength Btube is kept constant, the duration of the HDF Δt is almost constant while the maximum horizontal speed max(Vy) is proportional to q.

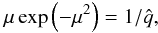

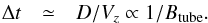

This feature can be explained by considering a simple model illustrated in Fig. 5b. Here the flux tube with a head size of 2L is rising at Vz, which pushes the plasma layer with a thickness D. The thickness D is also described as D ~ | ztop(t) |, where  . From the discussion in Sect. 4.1, Vz and thus D are independent of q, which indicates that the HDF duration Δt ≃ D/Vz is also independent of q.

. From the discussion in Sect. 4.1, Vz and thus D are independent of q, which indicates that the HDF duration Δt ≃ D/Vz is also independent of q.

If we write the outflow speed as Vy, mass flux conservation can be written as  (24)Here, Vz/D is independent of q. The head size of the tube L, however, depends on the twist q, since the aerodynamic drag peels away the tube’s outer flux and its amount depends on the twist. The head size remains larger with q, which results in the stronger HDF; Vy ∝ L(q). Thus, the maximum speed max(Vy) will also depend on q.

(24)Here, Vz/D is independent of q. The head size of the tube L, however, depends on the twist q, since the aerodynamic drag peels away the tube’s outer flux and its amount depends on the twist. The head size remains larger with q, which results in the stronger HDF; Vy ∝ L(q). Thus, the maximum speed max(Vy) will also depend on q.

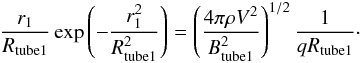

It should be noted here that L and q are not always linearly correlated. According to Moreno-Insertis & Emonet (1996), the boundary of the expanded tube is well defined by the equipartition surface, where the kinetic energy density equals the magnetic energy density of the azimuthal field  (25)On the basis of an analogy from Eq. (12), the profile of the expanded tube at the equipartition surface, where the radial distance is r1 (the subscript 1 indicates the expanded tube), is assumed to be written as

(25)On the basis of an analogy from Eq. (12), the profile of the expanded tube at the equipartition surface, where the radial distance is r1 (the subscript 1 indicates the expanded tube), is assumed to be written as  (26)where Btube1 and Rtube1 are the axial field and the typical radius, respectively. Then, Eq. (25) reduces to

(26)where Btube1 and Rtube1 are the axial field and the typical radius, respectively. Then, Eq. (25) reduces to  (27)Here we assume that V is approximate to Vz and thus V does not depend on q. Other values of Btube1, Rtube1, and ρ are also assumed to be constant for different q. Here we introduce the notation μ ≡ r1/Rtube1. Then Eq. (27) reduces to

(27)Here we assume that V is approximate to Vz and thus V does not depend on q. Other values of Btube1, Rtube1, and ρ are also assumed to be constant for different q. Here we introduce the notation μ ≡ r1/Rtube1. Then Eq. (27) reduces to  (28)or,

(28)or,  (29)where

(29)where ![\hbox{$\hat{q}\equiv qR_{\rm tube1} [ B_{\rm tube1}^{2}/(4\pi\rho V^{2})]^{1/2}$}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/05/aa21098-13/aa21098-13-eq165.png) . For a larger radial distance, r1 ≫ Rtube1, i.e., μ ≫ 1,

. For a larger radial distance, r1 ≫ Rtube1, i.e., μ ≫ 1,  (30)Then we obtain

(30)Then we obtain ![\begin{eqnarray} r_{1} \sim R_{\rm tube1} \left[ \ln{(qR_{\rm tube1})} +\frac{1}{2} \ln{ \left( \frac{B_{\rm tube1}^{2}}{4\pi\rho V^{2}} \right)} \right]^{1/2}\cdot \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/05/aa21098-13/aa21098-13-eq169.png) (31)Therefore, the effective size of the expanded tube L ~ r1 is at least positively correlated to q, but not in a linear manner.

(31)Therefore, the effective size of the expanded tube L ~ r1 is at least positively correlated to q, but not in a linear manner.

4.3. Dependence on the field strength

When the field strength at the tube’s axis Btube is varied while the twist q is fixed, the maximum HDF speed max(Vy) is found to be roughly proportional to the field strength. From Eq. (24), if we assume L/D is constant, the horizontal speed Vy and thus the maximum speed max(Vy) are proportional to the field strength Btube.

However, Fig. 4a clearly shows two regimes for the HDF duration Δt, stronger field cases that show a decreasing trend, and a middle case that deviates from this trend. Thus, we should take into account the difference between these regimes.

First, let us focus on the stronger field regime. Since the rising speed is proportional to the field strength, stronger tubes emerge faster. In this case, the accumulated plasma ahead of the tube does not drain down very much because of the short emergence period, and thus the thickness of the plasma layer becomes almost the same for these cases. That is, the thickness of the layer D is constant and is independent of the rising speed Vz. Since the rising speed is proportional to the field strength Btube, we have  (32)Hence, the HDF duration is inversely proportional to the field strength, which explains the trend in the stronger field regime of the fitted inverse function in Fig. 4a.

(32)Hence, the HDF duration is inversely proportional to the field strength, which explains the trend in the stronger field regime of the fitted inverse function in Fig. 4a.

The emergence takes longer with middle strength, and thus the drainage of the accumulated plasma becomes more effective, resulting in the much thinner layer D compared to the rising speed Vz. Therefore, the HDF duration Δt ≃ D/Vz becomes shorter and thus deviates from the inverse trend in the stronger field cases.

5. Summary

In this parametric survey, we vary the axial field strength, twist, and perturbation wavelength of the initial flux tube. As a result, we have found the following features.

The rising speed in the CZ strongly depends on the initial field strength, but its correlation with the twist is weak. The emergence is resisted by the curvature force only in the case when the perturbation wavelength is shortest. According to the analytic study, the rising rate (terminal velocity) is written as  , which indicates a strong dependence on the field strength and a weak correlation with the twist.

, which indicates a strong dependence on the field strength and a weak correlation with the twist.

As the flux tube approaches the surface, the accumulated plasma ahead of the tube escapes horizontally around the surface layer, which is called the HDF. The driver of the HDF is found to be the pressure gradient.

When the field strength increases, the maximum HDF speed becomes higher, because the rising speed mainly depends on the field strength. The HDF duration is divided into two groups. For the stronger tube regime (Btube ≳ 100B0), the duration is in simple inverse proportion to the field strength, while the weaker field regime (Btube ≲ 100B0) deviates from the trend in the stronger tube regime because the fluid draining is more effective.

The duration of the HDF is found to have no relation with the tube’s twist, since the rising speed is independent of the twist. However, the maximum HDF speed shows a positive correlation with the twist. This feature is explained by considering the head size of the main tube that remains after the aerodynamic drag peels away the tube’s outer field. The head size remains larger with the twist, which results in the stronger HDF.

If we apply the above dependencies of the HDF to the actual observations, we may be able to obtain information on the magnetic field in the subsurface layer, which we cannot observe optically.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous referee for improving the paper. S.T. is supported by Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Fellows. Numerical computations were carried out on NEC SX-9 and Cray XT4 at the Center for Computational Astrophysics, CfCA, of the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan. We are grateful to the GCOE program instructors of the University of Tokyo for proofreading/editing assistance.

References

- Archontis, V., Moreno-Insertis, F., Galsgaard, K., Hood, A., & O’Shea, E. 2004, A&A, 426, 1047 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, M. C. M., Rempel, M., Title, A. M., & Schüssler, M. 2010, ApJ, 720, 233 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Emonet, T., & Moreno-Insertis, F. 1998, ApJ, 492, 804 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Y. 2001, ApJ, 554, L111 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Linton, M. G., Longcope, D. W., & Fisher, G. H. 1996, ApJ, 469, 954 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Magara, T. 2001, ApJ, 549, 608 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Insertis, F., & Emonet, T. 1996, ApJ, 472, L53 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Murray, M. J., Hood, A. W., Moreno-Insertis, F., Galsgaard, K., & Archontis, V. 2006, A&A, 460, 909 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Parker, E. N. 1975, ApJ, 198, 205 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schüssler, M. 1979, A&A, 71, 79 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata, K., Tajima, T., Steinolfson, R. S., & Matsumoto, R. 1989, ApJ, 345, 584 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Toriumi, S., & Yokoyama, T. 2010, ApJ, 714, 505 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Toriumi, S., & Yokoyama, T. 2011, ApJ, 735, 126 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Toriumi, S., & Yokoyama, T. 2012, A&A, 539, A22 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Toriumi, S., Hayashi, K., & Yokoyama, T. 2012, ApJ, 751, 154 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

All Tables

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Height-time evolution of the flux tube. a) Cases for different Btube. b) Cases for different q. c) Cases for different λ. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Total magnetic field strength of the initial condition for case A and the final states for cases A to G, plotted over the range − 400 ≤ x/H0 ≤ 0 and 0 ≤ y/H0 ≤ 200. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 a) Cross-sectional profile of the rising magnetic flux tube (case A). Plotted value is the logarithmic field strength log 10( | B | /B0) averaged over 6.5 ≤ x/H0 ≤ 13.5 at the time t/τ0 = 500. The color saturates at | B | /B0 = 1.0 (red) and − 4.0 (purple). b) Horizontal velocity Vy/Cs0 (thick solid line), pressure gradient − ∂p/∂y × (10H0/p0) (dashed line), and magnetic pressure gradient − ∂pm/∂y × (10H0/p0) (dash-dotted line), at t/τ0 = 500. c) Same as b) but for t/τ0 = 600. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4 a) Dependence of the HDF duration Δt on the field strength Btube, and b) on the twist q. c) Dependence of the maximum HDF speed max(Vy) on the field strength Btube, and d) on the twist q. In Panels a) and c) we also plot other field strength cases, indicated by smaller asterisks. Solid lines are the fitted curves: a) Δt/τ0 = 5.08 × 103/(Btube/B0) + 5.97 × 10, b) Δt/τ0 = −8.57 × (qH0) + 7.80 × 10; c) max(Vy)/Cs0 = 8.35 × 10-3 × (Btube/B0) − 3.26 × 10-1; and d) max(Vy)/Cs0 = 8.10 × 10-1 × (qH0) + 8.02 × 10-2. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5 a) Cross-section of the rising flux tube along the axis (in the x − z plane). b) Cross-section of the rising flux tube and the plasma layer ahead of the tube (in the y − z plane). |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.