| Issue |

A&A

Volume 544, August 2012

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A16 | |

| Number of page(s) | 13 | |

| Section | Astrophysical processes | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201218967 | |

| Published online | 19 July 2012 | |

Secondary cosmic-ray nuclei from supernova remnants and constraints on the propagation parameters

1

INFN – Sezione di Perugia, 06122

Perugia,

Italy

e-mail: nicola.tomassetti@pg.infn.it

2

Physics Department, Torino University and INFN,

10125

Torino,

Italy

e-mail: fiorenza.donato@unito.it

Received:

6

February

2012

Accepted:

23

March

2012

Context. The secondary-to-primary boron-to-carbon (B/C) ratio is widely used to study the cosmic-ray (CR) propagation processes in the Galaxy. It is usually assumed that secondary nuclei such as Li-Be-B are generated entirely by collisions of heavier CR nuclei with the interstellar medium (ISM).

Aims. We study the CR propagation under a scenario where secondary nuclei can also be produced or accelerated by Galactic sources. We consider the processes of hadronic interactions inside supernova remnants (SNRs) and the re-acceleration of background CRs in strong shocks. We investigate their impact in the propagation parameter determination within present and future data.

Methods. Analytical calculations are performed in the frameworks of the diffusive shock acceleration theory and the diffusive halo model of CR transport. Statistical analyses are performed to determine the propagation parameters and their uncertainty bounds using existing data on the B/C ratio, as well as the simulated data expected from the AMS-02 experiment.

Results. The spectra of Li-Be-B nuclei emitted from SNRs are harder than those due to CR collisions with the ISM. The secondary-to-primary ratios flatten significantly at ~TeV/n energies, both from spallation and re-acceleration in the sources. The two mechanisms are complementary to each other and depend on the properties of the local ISM around the expanding remnants. The secondary production in SNRs is significant for dense background media, n1 ≳ 1 cm-3, while the amount of re-accelerated CRs is relevant to SNRs expanding into rarefied media, n1 ≲ 0.1 cm-3. Owing to these effects, the diffusion parameter δ may be underestimated by a factor of ~5–15%. Our estimations indicate that an experiment of the AMS-02 caliber can constrain the key propagation parameters, while breaking the source-transport degeneracy for a wide class of B/C-consistent models.

Conclusions. Given the precision of the data expected from ongoing experiments, the SNR production/acceleration of secondary nuclei should be considered, if any, to prevent a possible mis-determination of the CR transport parameters.

Key words: acceleration of particles / nuclear reactions, nucleosynthesis, abundances / cosmic rays / ISM: supernova remnants

© ESO, 2012

1. Introduction

The problems of the origin and propagation of the charged cosmic rays (CRs) in the Galaxy are among the major topics of resarch in modern astrophysics. It is generally accepted that primary CR nuclei such as H, He, C, N, and O, are accelerated in supernova remnants (SNRs) via diffusive shock acceleration (DSA) mechanisms, that produce power-law momentum spectra (Drury 1983). At relativistic energies, S ∝ p−ν ~ E−ν. After being accelerated, CRs are released in the circumstellar environment, where they diffuse through the turbulent magnetic fields and interact with interstellar matter (ISM) (Strong et al. 2007). Owing to diffusion, CRs stream out from the Galaxy on a characteristic timescale τesc ∝ E−δ. The spectrum of primary CR nuclei predicted at Earth is therefore Np ~ Sτesc. The collisions of these nuclei with interstellar gas are believed to be the mechanism producing the secondary CR nuclei, such as Li, Be, and B, which are under-abundant in the thermal ISM. Thus, the equilibrium spectra of secondary CRs are E−δ times softer than those of their progenitors. At energies above some tenths of GeV per nucleon, where CR nuclei reach the pure diffusive regime, this picture predicts power-law distributions such as Np ~ E−ν − δ for primary nuclei and Ns/Np ~ E−δ for secondary-to-primary ratios at Earth. These trends may be straightforwardly derived from the analytical solutions of Maurin et al. (2001). Present observations indicate that δ ~ 0.3–0.7 and ν ~ 2.0–2.4. The bulk of the data is collected at E ≲ 10 GeV nucleon-1, where the CR spectra are shaped by additional effects such as diffusive reacceleration, galactic wind convection, energy losses, and solar modulation. Since there is no firm theoretical prediction of the key parameters associated with these effects, it is very difficult to distinguish each physical component using the experimental data. The boron-to-carbon (B/C) ratio is the most robustly measured secondary-to-primary ratio and is used to constrain several model parameters. Throughout this paper, we call secondaries all CR nuclei produced by hadronic interactions, independently of their place of origin. The standard approach, hereafter reference model, assumes that the secondary nuclei are absent from the CR sources.

In this paper, we examine two mechanisms producing a source component of secondary CRs: (i)

the fragmentation of CR nuclei inside SNRs and (ii) the re-acceleration by SNRs of

pre-existing CR particles. The secondary CR production inside SNRs was studied in Berezhko et al. (2003) and subsequently reconsidered to

describe the positron fraction (Blasi 2009; Ahlers et al. 2009). Predictions of the  ratio (Blasi & Serpico 2009;

Fujita et al. 2009) and B/C ratio (Mertsch & Sarkar 2009; Thoudam & Hörandel 2011) have also been investigated. An interesting

aspect of this mechanism is that, if the secondary fragments start the DSA, the

secondary-to-primary ratios must eventually increase. Similarly, the re-acceleration of

background CRs interacting with the expanding SNR shells may induce a significant

transformation of their spectra at high energies (Berezhko

et al. 2003; Wandel et al. 1987). In

particular, the re-acceleration redistributes the spectrum of secondary nuclei to a spectrum

S ~ E−ν. The main

feature of both mechanisms is that they produce harder spectra of secondary nuclei than in

the case of their standard production from primary CR collisions in the ISM. These source

components of secondary CRs may become relevant at ~TeV energies. Thus, disregarding

these effects may lead to a mis-determination of the CR transport parameters. The aim of

this paper is to examine their impact on the CR propagation physics. This task requires a

description of the CR acceleration processes in SNRs and their interstellar propagation. In

this work, we use fully analytical calculations in the frameworks of the linear DSA theory

and the diffusion halo model (DHM) of CR transport. In Sect. 2, we present the DSA calculations for CR nuclei, including standard injection

from the thermal ISM, hadronic interactions, and re-acceleration. Section 3 outlines the basic elements of the DHM galactic

propagation. In Sect. 4, we show our model predictions

for the CR spectra and ratios at Earth, and study the impact of the secondary source

components on the determination of the CR transport parameters. In Sect. 5, we present our estimates for the Alpha Magnetic

Spectrometer (AMS). We present our conclusions in Sect. 6.

ratio (Blasi & Serpico 2009;

Fujita et al. 2009) and B/C ratio (Mertsch & Sarkar 2009; Thoudam & Hörandel 2011) have also been investigated. An interesting

aspect of this mechanism is that, if the secondary fragments start the DSA, the

secondary-to-primary ratios must eventually increase. Similarly, the re-acceleration of

background CRs interacting with the expanding SNR shells may induce a significant

transformation of their spectra at high energies (Berezhko

et al. 2003; Wandel et al. 1987). In

particular, the re-acceleration redistributes the spectrum of secondary nuclei to a spectrum

S ~ E−ν. The main

feature of both mechanisms is that they produce harder spectra of secondary nuclei than in

the case of their standard production from primary CR collisions in the ISM. These source

components of secondary CRs may become relevant at ~TeV energies. Thus, disregarding

these effects may lead to a mis-determination of the CR transport parameters. The aim of

this paper is to examine their impact on the CR propagation physics. This task requires a

description of the CR acceleration processes in SNRs and their interstellar propagation. In

this work, we use fully analytical calculations in the frameworks of the linear DSA theory

and the diffusion halo model (DHM) of CR transport. In Sect. 2, we present the DSA calculations for CR nuclei, including standard injection

from the thermal ISM, hadronic interactions, and re-acceleration. Section 3 outlines the basic elements of the DHM galactic

propagation. In Sect. 4, we show our model predictions

for the CR spectra and ratios at Earth, and study the impact of the secondary source

components on the determination of the CR transport parameters. In Sect. 5, we present our estimates for the Alpha Magnetic

Spectrometer (AMS). We present our conclusions in Sect. 6.

2. Acceleration in SNR shock waves

We compute the spectrum of CR ions accelerated in SNRs using the DSA theory (Drury 1983), including the loss and source terms and both the production and acceleration of secondary fragments. Our derivation is formally similar to that in Morlino (2011), but the physical problem is the same to that treated in Mertsch & Sarkar (2009). Within this formalism, we also compute the re-acceleration of pre-existing CR particles.

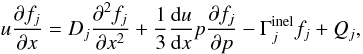

2.1. DSA calculations

We consider the case of plane shock geometry and a test-particle approximation, i.e., we

ignore the feedback of the CR pressure on the shock dynamics. The shock front is in its

rest-frame at x = 0. The un-shocked upstream plasma flows in from

x < 0 at speed u1 (density

n1) and the shocked downstream plasma flows out to

x > 0 at speed u2 (density

n2). These quantities are related by the compression ratio

r = u1/u2 = n2/n1.

The particle spectra are described by the phase space density

f(p,x). The equation that describes the diffusive

transport and convection at the shock for a j-type nucleus (charge

Zj and mass number

Aj) is given by:  (1)where Dj(p)

is the diffusion coefficient near the SNR shock, u is the fluid velocity,

(1)where Dj(p)

is the diffusion coefficient near the SNR shock, u is the fluid velocity,

is the total destruction rate for

fragmentation (see Sect. 2.3),

is the total destruction rate for

fragmentation (see Sect. 2.3),

is the cross-section for the process, and

Qj(x,p) represents the

source term. Solutions of Eq. (1) can be

found, separately, in the regions upstream (x < 0) and downstream

(x > 0) of the shock front, by requiring that

∂f/∂x = 0 for x → ∓ ∞. We drop the

label j characterizing the nuclear species, and make use of the subscript

i = 1 (i = 2) to indicate the quantities in the

upstream (downstream) region. We define the quantities

is the cross-section for the process, and

Qj(x,p) represents the

source term. Solutions of Eq. (1) can be

found, separately, in the regions upstream (x < 0) and downstream

(x > 0) of the shock front, by requiring that

∂f/∂x = 0 for x → ∓ ∞. We drop the

label j characterizing the nuclear species, and make use of the subscript

i = 1 (i = 2) to indicate the quantities in the

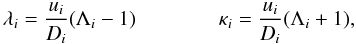

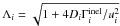

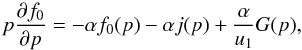

upstream (downstream) region. We define the quantities  (2)where

(2)where  . The solution can be expressed in the form

. The solution can be expressed in the form

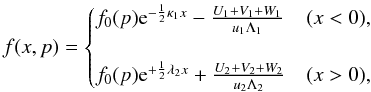

(3)where the downstream integral terms

U2, V2, and

W2 are given by:

(3)where the downstream integral terms

U2, V2, and

W2 are given by:  (4)In the upstream region,

U1, V1, and

W1 are still given by Eq. (4) after performing the substitutions 1 → 2,

κ2 → −λ1,

λ2 → −κ1, and ∞ → −∞. The

distribution function at the shock position, f0, is determined

by the matching conditions at x = 0. We integrate Eq. (1) in a thin region across the shock front.

Assuming that

D ≡ D1 = D2, we

find the equation for f0

(4)In the upstream region,

U1, V1, and

W1 are still given by Eq. (4) after performing the substitutions 1 → 2,

κ2 → −λ1,

λ2 → −κ1, and ∞ → −∞. The

distribution function at the shock position, f0, is determined

by the matching conditions at x = 0. We integrate Eq. (1) in a thin region across the shock front.

Assuming that

D ≡ D1 = D2, we

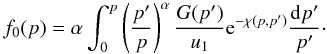

find the equation for f0 (5)where

α = 3u1/(u1 − u2)

is the known DSA spectral index. The term G denotes the sum of the

upstream and downstream source integrals

(5)where

α = 3u1/(u1 − u2)

is the known DSA spectral index. The term G denotes the sum of the

upstream and downstream source integrals

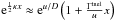

(6)The function

j(p) is linked to the destruction term

Γinel. It is defined as

(6)The function

j(p) is linked to the destruction term

Γinel. It is defined as  (7)After defining the function

(7)After defining the function  (8)the solution of Eq. (5) can be expressed in the simple form

(8)the solution of Eq. (5) can be expressed in the simple form

(9)From Eq. (3), one recovers the standard DSA solution by setting

Γinel = 0 (no interactions) and assuming that the injection occurs only at the

shock front

(Ui = Vi = Wi = 0):

one finds that f2 = f0 and

f1 = f0eu1x/D1,

while Eq. (9) gives a

spectrum p−α, provided that the source term

G(p) is softer than

p−α (see Sect. 2.4). Some simplifications can be made by analyzing the timescales of

the problem. The DSA acceleration rate for particles of momentum p in a

stationary shock is

(9)From Eq. (3), one recovers the standard DSA solution by setting

Γinel = 0 (no interactions) and assuming that the injection occurs only at the

shock front

(Ui = Vi = Wi = 0):

one finds that f2 = f0 and

f1 = f0eu1x/D1,

while Eq. (9) gives a

spectrum p−α, provided that the source term

G(p) is softer than

p−α (see Sect. 2.4). Some simplifications can be made by analyzing the timescales of

the problem. The DSA acceleration rate for particles of momentum p in a

stationary shock is  , where we assumed Bohm diffusion

(D ∝ p) and strong shocks (r ≈ 4).

For a SNR of age τsnr, the condition

, where we assumed Bohm diffusion

(D ∝ p) and strong shocks (r ≈ 4).

For a SNR of age τsnr, the condition

defines the maximum momentum

pmax attainable by DSA. In the presence of hadronic

interactions, the requirement Γinel ≪ Γacc must be fulfilled. These

relations imply that

20 ΓinelD/u2 ≪ 1 and

xΓinel/u ≪ 1 at all the energies

considered. Under these conditions, we can linearly expand

Λ ≈ 1 + 2ΓinelD/u2, so that

λ ≈ 2Γinel/u and

κ ≈ 2u/D + 2Γinel/u.

The exponential terms of Eqs. (3) and

(4) can also be expanded as

defines the maximum momentum

pmax attainable by DSA. In the presence of hadronic

interactions, the requirement Γinel ≪ Γacc must be fulfilled. These

relations imply that

20 ΓinelD/u2 ≪ 1 and

xΓinel/u ≪ 1 at all the energies

considered. Under these conditions, we can linearly expand

Λ ≈ 1 + 2ΓinelD/u2, so that

λ ≈ 2Γinel/u and

κ ≈ 2u/D + 2Γinel/u.

The exponential terms of Eqs. (3) and

(4) can also be expanded as

and

and

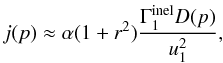

. Thus, the function

j(p) of Eq. (7) is given by

. Thus, the function

j(p) of Eq. (7) is given by  (10)and the integral of Eq. (8) by

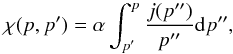

(10)and the integral of Eq. (8) by ![\begin{equation} \label{Eq::ChiApprox} \chi(p,p^{\prime}) \approx \alpha (1+r^{2}) \frac{\Gamma^{\rm inel}_{1}}{u_{1}^{2}} [ D(p) - D(p^{\prime}) ], \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2012/08/aa18967-12/aa18967-12-eq89.png) (11)which recovers the expression of Mertsch & Sarkar (2009). Below we present the DSA

solutions for primary nuclei (injected at the shock), their secondary fragments (generated

in the SNR environment), and pre-existing CR particles that undergo re-acceleration.

(11)which recovers the expression of Mertsch & Sarkar (2009). Below we present the DSA

solutions for primary nuclei (injected at the shock), their secondary fragments (generated

in the SNR environment), and pre-existing CR particles that undergo re-acceleration.

2.2. Acceleration of primary nuclei

The injection of ambient particles is assumed to occur immediately upstream from the

shock at momentum pinj. The source term for primary nuclei is

(12)Particles can be injected only when their

Larmor radius is large enough to cross the shock thickness. Thus, we

assume a reference injection rigidity for all nuclei, Rinj, so

that

pinj = ZRinj. The

constant Y reflect the particle abundances in the ISM and their injection

efficiencies. In this work, they are determined by the data. The phase space density

profile is given by

(12)Particles can be injected only when their

Larmor radius is large enough to cross the shock thickness. Thus, we

assume a reference injection rigidity for all nuclei, Rinj, so

that

pinj = ZRinj. The

constant Y reflect the particle abundances in the ISM and their injection

efficiencies. In this work, they are determined by the data. The phase space density

profile is given by  (13)The upstream profile,

~eu1x/D,

indicates that the plasma is confined near the shock within a typical distance

~D/u1. Owing to advection, the

particles are accumulated in the downstream region, where destruction processes give rise

to the term

(13)The upstream profile,

~eu1x/D,

indicates that the plasma is confined near the shock within a typical distance

~D/u1. Owing to advection, the

particles are accumulated in the downstream region, where destruction processes give rise

to the term  . The momentum spectrum at the shock

position is

f0 ∝ e−χp−α,

which is the known DSA power-law behavior times an exponential factor,

~e−χ, given by

χ ≈ αΓinel/Γacc. The condition

. The momentum spectrum at the shock

position is

f0 ∝ e−χp−α,

which is the known DSA power-law behavior times an exponential factor,

~e−χ, given by

χ ≈ αΓinel/Γacc. The condition

implies that χ ≲ 1.

implies that χ ≲ 1.

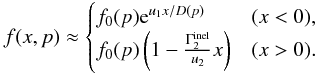

2.3. Production and acceleration of secondary nuclei

Secondary nuclei originate in the SNR environment from the spallation of heavier nuclei

on the background medium. The source term for a j-type CR species arises

from the sum of all heavier k-type nuclei,

. Each partial contribution is defined to

be:

. Each partial contribution is defined to

be:  (14)where

Nk(x, p′) = 4πp′2fk(x, p′)

is the progenitor number density and

(14)where

Nk(x, p′) = 4πp′2fk(x, p′)

is the progenitor number density and  is the

k → j fragmentation rate, which is implicitly summed

over the circumstellar abundances (the hydrogen and helium components). We have assumed

that the kinetic energy per nucleon is conserved in the process, i.e., the fragments are

ejected with momentum

ξkj = Aj/Ak

times smaller than that of their parents. The presence of short-lived isotopes

(ghost nuclei) such as 9Li or 11C is reabsorbed

in the definition of σkj, while long-lived

isotopes such as 10Be or 26Al (lifetime ~1 Myr) are considered

as stable during the acceleration process (timescale

τsnr ~10 kyr). The source spatial profile takes the form

of the progenitor nucleus of Eq. (13). In

the upstream region, one has

is the

k → j fragmentation rate, which is implicitly summed

over the circumstellar abundances (the hydrogen and helium components). We have assumed

that the kinetic energy per nucleon is conserved in the process, i.e., the fragments are

ejected with momentum

ξkj = Aj/Ak

times smaller than that of their parents. The presence of short-lived isotopes

(ghost nuclei) such as 9Li or 11C is reabsorbed

in the definition of σkj, while long-lived

isotopes such as 10Be or 26Al (lifetime ~1 Myr) are considered

as stable during the acceleration process (timescale

τsnr ~10 kyr). The source spatial profile takes the form

of the progenitor nucleus of Eq. (13). In

the upstream region, one has  , where

Dk is the diffusion coefficient of the

progenitor nucleus at the momentum

p/ξkj. For

D ∝ p/Z, one can write

Dk(p/ξkj) = ζkjDj(p),

where

, where

Dk is the diffusion coefficient of the

progenitor nucleus at the momentum

p/ξkj. For

D ∝ p/Z, one can write

Dk(p/ξkj) = ζkjDj(p),

where  . In practice,

ζkj ≈ 1 for all processes

k → j with

Zj,k > 2. The terms at the shock,

q1,jk and

q2,jk, are given by

. In practice,

ζkj ≈ 1 for all processes

k → j with

Zj,k > 2. The terms at the shock,

q1,jk and

q2,jk, are given by

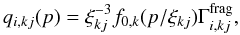

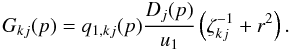

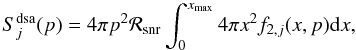

(15)and the downstream solution reads

(15)and the downstream solution reads

![\begin{equation} \label{Eq::DownStreamSecondary} f_{2,j}(x,p) = f_{0,j}(p) + \left[ \frac{q_{2,j}(p)}{u_{2}}- \Gamma^{\rm frag}_{2,j}f_{0,j}(p) \right] x, \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2012/08/aa18967-12/aa18967-12-eq128.png) (16)where

f0,j is given from Eq. (9) using G(p)

by the expression

(16)where

f0,j is given from Eq. (9) using G(p)

by the expression  (17)We solve all equations starting from the

heaviest element and proceeding downward in mass. We are interested in the total

contribution of SNRs to the Galactic CR population, which we evaluate to be the integral

of the downstream solution over the SNR volume left behind the shock

(17)We solve all equations starting from the

heaviest element and proceeding downward in mass. We are interested in the total

contribution of SNRs to the Galactic CR population, which we evaluate to be the integral

of the downstream solution over the SNR volume left behind the shock  (18)where

xmax = u2τsnr

and ℛsnr is the supernovae explosion rate per unit volume in the Galaxy.

(18)where

xmax = u2τsnr

and ℛsnr is the supernovae explosion rate per unit volume in the Galaxy.

2.4. Re-acceleration of background CR nuclei

Together with the thermal ISM particles of Sect. 2.2, SNR shock waves may also accelerate the background CRs at equilibrium (Berezhko et al. 2003; Wandel et al. 1987). We refer to this mechanism as the re-acceleration

of CRs in SNRs. For a prescribed distribution function of background CRs,

, the DSA solution at the shock is simply

, the DSA solution at the shock is simply

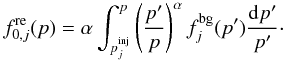

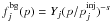

(19)Assuming, for illustrative purposes, a

power-law form

(19)Assuming, for illustrative purposes, a

power-law form  , the resulting re-acceleration spectrum is

, the resulting re-acceleration spectrum is

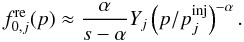

![\begin{equation} f_{0,j}^{\rm re}(p) = \frac{\alpha}{\alpha-s} \left[ 1 - (p/p^{\rm inj}_{j})^{-\alpha + s} \right]f^{\rm bg}_{j}(p). \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2012/08/aa18967-12/aa18967-12-eq137.png) (20)Since the CR equilibrium spectrum,

fbg ∝ p−s, is

softer than the test-particle one (s > α), for

(20)Since the CR equilibrium spectrum,

fbg ∝ p−s, is

softer than the test-particle one (s > α), for

one obtains

one obtains

(21)That is, the effect of re-acceleration is to

re-distribute the CR spectrum to p−α.

Interestingly, in the opposite case (s < α) the

re-accelerated spectrum maintains its spectral shape

p−s, while its normalization is amplified

by the factor α/(s − α). In our model,

however, the background spectrum fbg is computed as discussed

in Sect. 3 and takes the SNR spectra as input.

Therefore, Eq. (19) is an

integro-differential equation where the DSA-mechanism is fed by its DHM-propagated

solution and vice-versa. On the other hand, the bulk of the re-accelerated CRs come from

the low-energy part of the spectrum (below ~10 GV of rigidity), where the

equilibrium CR spectra are fixed by the observations so they cannot vary too much. It can

be safely assumed that re-accelerated CRs are a sub-dominant component of the total

(integral) flux. Hence, we proceed using an iterative method as outlined in Sect. 4.5.

(21)That is, the effect of re-acceleration is to

re-distribute the CR spectrum to p−α.

Interestingly, in the opposite case (s < α) the

re-accelerated spectrum maintains its spectral shape

p−s, while its normalization is amplified

by the factor α/(s − α). In our model,

however, the background spectrum fbg is computed as discussed

in Sect. 3 and takes the SNR spectra as input.

Therefore, Eq. (19) is an

integro-differential equation where the DSA-mechanism is fed by its DHM-propagated

solution and vice-versa. On the other hand, the bulk of the re-accelerated CRs come from

the low-energy part of the spectrum (below ~10 GV of rigidity), where the

equilibrium CR spectra are fixed by the observations so they cannot vary too much. It can

be safely assumed that re-accelerated CRs are a sub-dominant component of the total

(integral) flux. Hence, we proceed using an iterative method as outlined in Sect. 4.5.

|

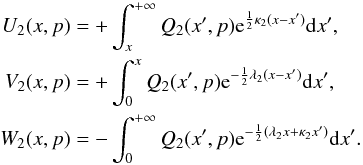

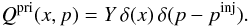

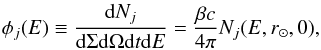

Fig. 1 Energy spectra of the CR elements Li, Be, B, C, N, O, Ne, Mg and Si. The solid lines represent the reference model prediction. The dashed lines indicate the secondary CR component arising by collisions of heavier nuclei in the ISM. The model parameters are listed in Table 1. Data are from HEAO3-C2 (Engelmann et al. 1990), CREAM (Ahn et al. 2009), AMS-01 (Aguilar et al. 2010), TRACER (Ave et al. 2008; Obermeier et al. 2011), ATIC-2 (Panov et al. 2009), CRN (Müller et al. 1991), Simon et al. (1980), Lezniak & Webber (1978) and Orth et al. (1978). The Li-Be-B data from CREAM and AMS-01 are combined with our model to obtain the spectra from their secondary-to-primary ratios. |

3. Interstellar propagation

We use a DHM to describe the CR transport and interactions in the ISM in a two-dimensional

geometry. We disregard the effects of energy losses, diffusive reacceleration, and

convection. The Galaxy is modeled as a disk of half-thickness h, containing

the gas and the CR sources. The disk is surrounded by a cylindrical diffusive halo of

half-thickness L, radius rmax, and zero matter

density. The CRs diffuse into both the disk and the halo. The diffusion coefficient is taken

to be rigidity dependent and position independent such that

K(R) = βK0(R/R0)δ.

The number density Nj of the nucleus

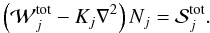

j is a function of the kinetic energy per nucleon, E,

and the position (r,z). The steady-state transport equation can be written

as  (22)The loss term,

(22)The loss term,

, describes the decay rate of unstable

nuclei,

, describes the decay rate of unstable

nuclei,  (where

γL is the usual Lorentz factor) and the

total destruction rate for collisions in the disk,

(where

γL is the usual Lorentz factor) and the

total destruction rate for collisions in the disk,  . The source term,

. The source term,

, is the sum of contributions from SNRs

(the DSA solution of Eq. (18)), and the

secondary production in the ISM from k-type progenitors

, is the sum of contributions from SNRs

(the DSA solution of Eq. (18)), and the

secondary production in the ISM from k-type progenitors  The function

s(r) expresses the SNR radial distribution in the disk,

that we assume to be uniform. For primary CRs, Sdsa is

normalized by the Y constants of Eq. (12). In our study, secondary nuclei may have a non-zero

Sdsa term. The term

The function

s(r) expresses the SNR radial distribution in the disk,

that we assume to be uniform. For primary CRs, Sdsa is

normalized by the Y constants of Eq. (12). In our study, secondary nuclei may have a non-zero

Sdsa term. The term  describe the contributions

k → j from unstable progenitors of lifetime

τkj. In Eq. (24),

describe the contributions

k → j from unstable progenitors of lifetime

τkj. In Eq. (24),  and

and  . The conditions

Nj ≡ 0 at the halo boundaries and the

continuity condition across the disk completely characterize the solution of Eq. (22). The full solution is reported in Maurin et al. (2001). We again solve the transport

equations for all the CR nuclei following their top–down fragmentation sequence, plus a

second iteration to account for the 10Be → 10B decay. The differential

fluxes as a function of kinetic energy per nucleon E are obtained from

. The conditions

Nj ≡ 0 at the halo boundaries and the

continuity condition across the disk completely characterize the solution of Eq. (22). The full solution is reported in Maurin et al. (2001). We again solve the transport

equations for all the CR nuclei following their top–down fragmentation sequence, plus a

second iteration to account for the 10Be → 10B decay. The differential

fluxes as a function of kinetic energy per nucleon E are obtained from

(25)where the equilibrium solutions are computed at

the Solar System position (r,z) = (8.5 kpc,0). The basic DHM predictions

can be seen, for illustrative purpose, in the one-dimensional limit

rmax → ∞. The solution for a pure primary CR is given by

(25)where the equilibrium solutions are computed at

the Solar System position (r,z) = (8.5 kpc,0). The basic DHM predictions

can be seen, for illustrative purpose, in the one-dimensional limit

rmax → ∞. The solution for a pure primary CR is given by

(26)where the spallation rate is neglected for

simplicity. The effect of the propagation in steepening the spectrum is clearly evident: for

a source spectrum

Sdsa(E) ∝ E−ν

and a Galactic diffusion coefficient of the type

K(E) ∝ Eδ,

the model predicts that

N(E) ∝ E−ν − δ.

To resolve the two parameters ν and δ, one has to consider

pure secondary species. The solution for a one-progenitor secondary CR is given by

Eq. (26), with the replacement of

Sdsa with

(26)where the spallation rate is neglected for

simplicity. The effect of the propagation in steepening the spectrum is clearly evident: for

a source spectrum

Sdsa(E) ∝ E−ν

and a Galactic diffusion coefficient of the type

K(E) ∝ Eδ,

the model predicts that

N(E) ∝ E−ν − δ.

To resolve the two parameters ν and δ, one has to consider

pure secondary species. The solution for a one-progenitor secondary CR is given by

Eq. (26), with the replacement of

Sdsa with  , so that the ratio

Ns/Np ∝ L/K

allows the simultaneous determination of δ and

K0/L. These simple trends are valid for the

reference model, i.e. when only primary CRs have a source term. In the

case of a secondary SNR component, depending on its intensities, the parameter determination

may be more complicated.

, so that the ratio

Ns/Np ∝ L/K

allows the simultaneous determination of δ and

K0/L. These simple trends are valid for the

reference model, i.e. when only primary CRs have a source term. In the

case of a secondary SNR component, depending on its intensities, the parameter determination

may be more complicated.

4. Analysis and results

We now review the model parameters and test the reference model setup. We then analyze the secondary CR production and re-acceleration in SNRs in some simple scenarios.

4.1. Model parameters

The DSA mechanism of Sect. 2 provides power-law

spectra

Sdsa ∝ E−ν with

a unique spectral index ν = α − 2 for all the primary

CRs, where α, in turn, is linked to the compression

ratio r, which is specified by δ and the observed

log-slope γ. To match γ ≈ 2.7 with

δ < 0.7, one has to adopt a compression factor of

r < 4, in contrast to the value r = 4 required for

strong shocks. Despite this tension between DSA and observations, we regard

r as an effective quantity describing the compression ratio actually

felt by the particles, which is not necessary related to the physical strength of the SNR

shocks (Ptuskin et al. 2010). The diffusion

coefficient around the shock is taken to be Bohm-like,

. The ambient magnetic field

B may reach ~100 μG or more, because of

amplification effects, except for the very late SNR evolutionary stages, where the

magnetic field may be damped (B ≲ μG). In our

steady-state description, the SNR parameters have to be considered as effective

time-averaged quantities representing a more complex situation where the shock structure

evolves with time and may be influenced by the back-reaction of accelerated CRs. The

average shock speed u1 is of the order of

108 cm s-1. The upstream gas density,

n1, is poorly known and may well vary from

~10-3 to ~10 cm-3, depending on the SNR progenitor

star or its local environment. The SNR explosion rate per unit volume is expressed as a

surface density, 2hℛsnr, that we fix to

25 Myr-1 kpc-2 (Grenier

2000).

. The ambient magnetic field

B may reach ~100 μG or more, because of

amplification effects, except for the very late SNR evolutionary stages, where the

magnetic field may be damped (B ≲ μG). In our

steady-state description, the SNR parameters have to be considered as effective

time-averaged quantities representing a more complex situation where the shock structure

evolves with time and may be influenced by the back-reaction of accelerated CRs. The

average shock speed u1 is of the order of

108 cm s-1. The upstream gas density,

n1, is poorly known and may well vary from

~10-3 to ~10 cm-3, depending on the SNR progenitor

star or its local environment. The SNR explosion rate per unit volume is expressed as a

surface density, 2hℛsnr, that we fix to

25 Myr-1 kpc-2 (Grenier

2000).

The parameters describing the interstellar diffusion coefficient are fixed to δ = 0.5 and K0 = 0.089 kpc2 Myr-1 (see Sect. 4.2). Below the reference rigidity, R0 = 4 GV, we set δ = 0. However our analysis is always applied to rigidities R > R0. The halo radius is rmax = 20 kpc and its half-height is L = 5 kpc. As per the propagation in the ISM, the quantity that enters the model is surface density h × nism, where we take h = 0.1 kpc and nism = 1 cm-3. We assume a composition of 90% H + 10% He for the ISM gas density, nism, and that this composition, on average, is also found in the SNR background media. In addition, we include the solar modulation effect, though it is relevant only below few GeV nucleon-1. The modulation is described in the force-field approximation (Gleeson & Axford 1968) by means of the parameter φ, taken to be 500 MV, to characterize a medium-level modulation strength. Our nuclear chain starts with Zmax = 14 and processes all the relevant isotopes down to Z = 3. Nuclei with Z > 14 do not contribute significantly to the Li-Be-B abundances. The spallation cross-sections are taken from Silberberg et al. (1998). The cross-sections on He targets are obtained by means of the algorithm presented in Ferrando et al. (1998). The reference model parameters are listed in Table 1.

Source and transport parameter sets.

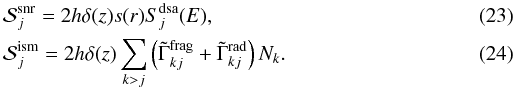

4.2. Reference model

Before analyzing the impact of SNR production and re-acceleration of secondary CRs on the parameter determination, we test the reference model predictions for the parameters in Table 1. Predictions at Earth for the CR elemental spectra Li, Be, B, C, N, O, Ne, Mg, and Si are presented in Fig. 1, where the total spectra (solid lines) are shown together their secondary component (dashed lines) arising from collisions in the ISM. The key quantities for propagation, K0 and δ, are determined from the B/C ratio above 2 GeV nucleon-1, using all the data reported in the past two decades, i.e., from the space-based experiments HEAO3-C2 (Engelmann et al. 1990), CRN (Swordy et al. 1990), and AMS-01 (Aguilar et al. 2010), and the balloon-borne projects CREAM (Ahn et al. 2009) and ATIC-2 (Panov et al. 2007). The primary nuclei spectra were normalized using data from CREAM (for C, N, O, Ne, Mg, and Si) and HEAO3-C2 (for all elements). Given the K0 − L degeneracy (see Sect. 3), in the following we adopt the quantity K0/L as the physical parameter, where the halo height L is fixed at 5 kpc.

As apparent from the figure, the reference model calculations give a good description of the CR elemental spectra within the precision of the present data. We note that, under this pure diffusion model, the B/C data between ~10 GeV and ~1 TeV per nucleon suggest that δ ~ 0.4, while the data at lower energies (~1–100 GeV nucleon-1) favor higher values (δ ~ 0.6). These uncertainties are related on both the model unknowns at ~GeV/n energies and the lack of data at ≳100 GeV nucleon-1 (Maurin et al. 2010). We also note that the reference model predictions are insensitive to the source parameters n1, u1, and B: the source spectra are specified only by the effective compression ratio r (via γ and δ) and the abundance constants Y. This setup is equivalent to that of many diffusion models, e.g. Maurin et al. (2001), that make use of rigidity power-law parameterizations as source functions.

4.3. SNR models

Similarly to Morlino (2011), we consider two ideal situations represented by Type I/a (important for fragmentation, Sect. 4.4) and core-collapse supernovae (important for re-acceleration, Sect. 4.5). In the Type I/a scenario, the supernova explodes in the regular ISM with typical density and temperature n1 ≈ 1 cm-3 and T0 = 104 K. In the core-collapse scenario, the SNR expands into a hot diluted bubble (n1 ≪ 1 cm-3 and T0 ≫ 104 K) that may be generated by either the progenitor’s wind or by previous SNR explosions that occurred in the same region. In both scenarios, the circumstellar densities are assumed to be homogeneous and constant during the SNR evolution. Two SNR evolutionary stages are relevant to our study: the ejecta-dominated (ED) phase, when the shock front expands freely and accumulates the swept-up mass in the SNR interior, and the Sedov-Taylor (ST) expansion phase, which is driven by the thermal pressure of the hot gas. The phase transition ED–ST occurs at the time τst, when the swept-up mass equals the mass of the ejecta Mej. The CR acceleration ceases at the time τsnr.

Case studies of Type I/a and core-collapse SNRs.

For all the models, we assume Esnr = 5 × 1051 erg,

Mej = 4 M⊙, and

τsnr = 20 kyr, where Esnr is the

SNR explosion energy (not converted into neutrinos) and M⊙ is

the solar mass. The cases of different τsnr values are

considered in Sect. 4.6. During the ED stage, the

SNR radius grows with a constant rate

Rsh(t) = u1t,

at the speed

u1 = (2Esnr/Mej)1/2 ~ 108 cm s-1,

until it reaches the swept-up radius

Rsw ≡ Rsh(τst).

For a given SNR model characterized by n1 and

τsnr, we parametrize the shock evolution

(Rsh and u1) using the

self-similar solutions derived in Truelove & McKee

(1999) for a remnant expanding into a homogeneous medium. These solutions connect

smoothly the ED phase (Rsh ∝ t) with the ST

stage (Rsh ∝ t2/5). The CR

acceleration ceases at time τsnr, from which we compute the

average velocity  . Thus, we use

. Thus, we use

as an input parameter for our steady-state

DSA calculations (Sect. 2.1) to compute the spectra

for all the CR elements. The SNR models considered are listed in Table 2.

as an input parameter for our steady-state

DSA calculations (Sect. 2.1) to compute the spectra

for all the CR elements. The SNR models considered are listed in Table 2.

We always assume that the total CR flux is produced by SNRs of only one type: for each SNR model, the parameters employed have to be regarded as effective ones representing the average population of CR sources. We note that this simplified breakdown is somewhat artificial, because the total CR flux may be due to a complex ensemble of contributing SNRs.

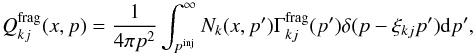

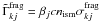

4.4. Secondary CR production in Type I/a SNRs

The secondary production of CRs is relevant for SNRs that expand into ambient densities of the order of n1 ~ 1 cm-3, where the quantity n1 represents the average SNR background density. Such a value may be higher than that of the average ISM, owing to, e.g., contributions from SNRs located in high density regions of the Galactic bulge, inside the dense cores of molecular clouds or SNRs expanding into the winds of their progenitors.

|

Fig. 2 Energy spectra of secondary elements Li, Be, and B. The source components from

fragmentation occurring inside SNRs are split into the

|

|

Fig. 3 Top: individual CR spectra of B and C. Solid lines are the model predictions for I/a #3 SNR model of Table 2. Model parameters are as in Table 1, except for δ and K0/L, which are fitted to data. The boron SNR component (dotted line) and the ISM component (dashed lines) are reported. Bottom: the B/C ratio from the above model (solid line) and when fragmentation in SNR is turned off (dashed line). Data are from HEAO3-C2 (Engelmann et al. 1990), CREAM (Ahn et al. 2009), AMS-01 (Aguilar et al. 2010), TRACER (Obermeier et al. 2011), ATIC-2 (Panov et al. 2007), CRN (Müller et al. 1991), Simon et al. (1980), Lezniak & Webber (1978), and Orth et al. (1978). |

From Eq. (16), one sees that the

secondary CR flux emitted by SNRs has two components. By analogy with Blasi & Serpico (2009) and Kachelrieß et al. (2011), these are referred to as

and ℬ. The

and ℬ. The  -term,

proportional to f0, describes the particles that are produced

within a distance ~D/u of both the sides of the

shock front and are still able to undergo DSA. From Eq. (17), the

-term,

proportional to f0, describes the particles that are produced

within a distance ~D/u of both the sides of the

shock front and are still able to undergo DSA. From Eq. (17), the  -spectrum

is f ~ p−α + 1,

reflecting the spectrum of their progenitors

(f ~ p−α) and the

momentum dependence of the diffusion coefficient, D ∝ p.

The ℬ-term, f ~ q2, describes those

secondary nuclei that, after being produced, are simply advected downstream without

experiencing further acceleration. Their spectrum maintains the same behavior as that of

their progenitors

q2 ~ p−α.

These components are illustrated in Fig. 2 for the

spectra at Earth of Li, Be, and B for a SNR with

n1 = 2 cm-3,

u1 = 5 × 107 cm s-1, and

B = 0.1 μG. The figure compares the standard ISM

components (solid lines) with the source components

-spectrum

is f ~ p−α + 1,

reflecting the spectrum of their progenitors

(f ~ p−α) and the

momentum dependence of the diffusion coefficient, D ∝ p.

The ℬ-term, f ~ q2, describes those

secondary nuclei that, after being produced, are simply advected downstream without

experiencing further acceleration. Their spectrum maintains the same behavior as that of

their progenitors

q2 ~ p−α.

These components are illustrated in Fig. 2 for the

spectra at Earth of Li, Be, and B for a SNR with

n1 = 2 cm-3,

u1 = 5 × 107 cm s-1, and

B = 0.1 μG. The figure compares the standard ISM

components (solid lines) with the source components

(short-dashed lines) and ℬ (long-dashed lines) within the same propagation parameter set.

Both the source components are harder than those expected from the standard CR production

in ISM; in particular, the

(short-dashed lines) and ℬ (long-dashed lines) within the same propagation parameter set.

Both the source components are harder than those expected from the standard CR production

in ISM; in particular, the  -term

leads to increasing secondary-to-primary ratios at high energies (Blasi 2009; Mertsch & Sarkar

2009). While the ℬ-term depends on the SNR ambient

density n1 and its age τsnr, the

-term

leads to increasing secondary-to-primary ratios at high energies (Blasi 2009; Mertsch & Sarkar

2009). While the ℬ-term depends on the SNR ambient

density n1 and its age τsnr, the

-term

also relies on the diffusion properties, as its strength is proportional to

~

-term

also relies on the diffusion properties, as its strength is proportional to

~ . However, the parameter combination

. However, the parameter combination

should be sufficiently large to ensure an

should be sufficiently large to ensure an

-term

dominance at ~TeV energies, which can be realized only in the latest evolutionary

stage of a SNR characterized by damped magnetic fields

(B ≪ 1 μG) and low shock speeds

(u1 < 108 cm s-1). On the other

hand, the local flux of stable CR nuclei depends on the large-scale structure of the

galaxy (of some kpc) and reflects the contribution of a relatively large population of

SNRs and their histories (Taillet & Maurin

2003). Furthermore, from Eqs. (9)

and (11), the

-term

dominance at ~TeV energies, which can be realized only in the latest evolutionary

stage of a SNR characterized by damped magnetic fields

(B ≪ 1 μG) and low shock speeds

(u1 < 108 cm s-1). On the other

hand, the local flux of stable CR nuclei depends on the large-scale structure of the

galaxy (of some kpc) and reflects the contribution of a relatively large population of

SNRs and their histories (Taillet & Maurin

2003). Furthermore, from Eqs. (9)

and (11), the

-term

induces an exponential cut-off at momentum pcut given by

χ(pcut) ≈ 1, which is not observed in

present data of primary or secondary CR spectra. Since our aim is to estimate these

effects when the considered SNRs produce all the observed CR flux, the associated

parameters have to be able to accelerate all CR nuclei up to, say,

pmax/Z ~ 106 GV. Thus, from

the requirement that χ ≲ 1 for any p up to

pmax (see Sect. 2.1),

the

-term

induces an exponential cut-off at momentum pcut given by

χ(pcut) ≈ 1, which is not observed in

present data of primary or secondary CR spectra. Since our aim is to estimate these

effects when the considered SNRs produce all the observed CR flux, the associated

parameters have to be able to accelerate all CR nuclei up to, say,

pmax/Z ~ 106 GV. Thus, from

the requirement that χ ≲ 1 for any p up to

pmax (see Sect. 2.1),

the  -term

is always ineffective at the energies we consider and is not discussed below. Given the

absence of a clear spectral feature in the ℬ-term, the spectral deformation induced by

interactions in SNRs may be difficult to detected ~TeV energies, because it can be

easily mimicked by a different choice of δ and

K0/L. This is illustrated in Fig. 3, where the total boron spectrum (solid line) is plotted

showing its standard component arising from ISM collisions (dashed line) and the source

component coming from hadronic interactions in SNRs (dotted line). The SNR model is the

I/a #3 of Table 2. We note that the carbon flux

also contains a small amount of secondary fragments (≲ 5%), produced in both ISM and SNRs.

The B/C ratio is also plotted for the reference model (dashed line) under

the same propagation parameter setting, i.e. when hadronic interactions in SNRs are turned

off. The effect of including secondary production in the sources translates into a slight

increase at 100 GeV nucleon-1, while it reaches a factor 2.5 at 1 TeV

nucleon-1 and one order of magnitude at 10 TeV nucleon-1.

-term

is always ineffective at the energies we consider and is not discussed below. Given the

absence of a clear spectral feature in the ℬ-term, the spectral deformation induced by

interactions in SNRs may be difficult to detected ~TeV energies, because it can be

easily mimicked by a different choice of δ and

K0/L. This is illustrated in Fig. 3, where the total boron spectrum (solid line) is plotted

showing its standard component arising from ISM collisions (dashed line) and the source

component coming from hadronic interactions in SNRs (dotted line). The SNR model is the

I/a #3 of Table 2. We note that the carbon flux

also contains a small amount of secondary fragments (≲ 5%), produced in both ISM and SNRs.

The B/C ratio is also plotted for the reference model (dashed line) under

the same propagation parameter setting, i.e. when hadronic interactions in SNRs are turned

off. The effect of including secondary production in the sources translates into a slight

increase at 100 GeV nucleon-1, while it reaches a factor 2.5 at 1 TeV

nucleon-1 and one order of magnitude at 10 TeV nucleon-1.

|

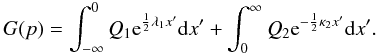

Fig. 4 Fit results for the parameters δ and K0/L of our models with fragmentation in Type I/a SNRs. Results are shown for Emin = 2, 5 and 10 GeV nucleon-1 (top to bottom), for the reference model and for the SNR models I/a # 1, # 2 and # 3 (left to right) of Table 2. The shaded areas represent the 1-, 2- and 3-σ contour limits. The markers “ × ” indicate the best-fit parameters for each configuration; the χ2/d.f. ratio is reported in each panel. |

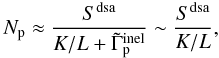

From the B/C ratio data, we determined the parameters K0/L and δ for the Type I/a SNR models of Table 2. We performed a χ2 analysis using our model interfaced with MINUIT. The data were fit above a minimal energy of Emin = 10 GeV nucleon-1, as a compromise between the diffusion–dominated regime and the availability of experimental data. We also repeated the fits down to lower Emin to test the relevance of low energy effects to our model. The results are shown in Fig. 4 for Emin = 2, 5, and 10 GeV nucleon-1 (from top to bottom), for reference model and I/a models of Table 2 (left to right). The shaded areas represent the 1-, 2-, and 3-σ contour limits of the χ2. We stress that these parameter uncertainties are those arising from the fits and that they are contextual to our models. Owing to the complexity of the physics processes involved together with the possible lack of knowledge of several astrophysical inputs, the actual parameter uncertainties may be much larger (Maurin et al. 2010). For instance, the published values of δ vary widely from ~0.3 to ~0.7. The markers describe the best-fit parameters for each configuration. The χ2 values reported in each panels are divided by the degrees of freedom d.f. = 26, 21, and 16 for the considered energy thresholds. It can be seen from Fig. 4 that the source component has a little effect for model I/a #3 (n1 = 0.5 cm-3). When denser media were considered, the secondary source component was found to flatten the B/C ratio, so that higher values of δ were required to match the data. This trend is clearly apparent in Fig. 4 (from left to right). Similar conclusions, though weaker, can be drawn for the K0/L parameter ratio. To first approximation, B/C ∝ L/K0, so that the presence of a SNR component of boron requires a larger K0/L ratio to match the data.

In summary, for the SNR models considered, the fragmentation in SNRs affects the parameter δ of ~5–15% (and K0/L of ~2–10%), but these models cannot be discriminated by present data because of the large uncertainties in the data. This n1–δ degeneracy is apparent by the χ2/d.f.-values, which are almost insensitive to the SNR properties.

|

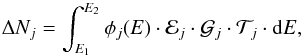

Fig. 5 Top: individual CR spectra of B and C. Solid lines are the model predictions for CC #2 SNR model of Table 2. Model parameters are as in Table 1 except for δ and K0/L, which are fitted to data. The boron SNR component (dotted line) and the ISM component (dashed lines) are reported. Bottom: the B/C ratio from the above model (solid line) and when re-acceleration is turned off (dashed line). Data as in Fig. 3. |

4.5. Re-acceleration in core-collapse SNRs

The amount of re-accelerated CRs depends on the total volume occupied by the SNRs (per

unit time) and their explosion rate (per unit volume). The fraction of re-accelerated CRs

to the total background CRs can be roughly estimated as

Nre/Nbg ~ Vsnrℛsnrτesc,

where Vsnr is the SNR volume and

τesc is the characteristic escape time of CRs in the Galaxy.

At a few GeV nucleon-1,

τesc ~ 2hL/K ~ 5 Myr.

The Vsnr is mainly determined by its expansion during the ED

phase; the SNR reaches a spherical volume  ,

where

,

where  is the mean mass of the ambient gas. Thus

Nre/Nbg ∝ 1/n1,

which is an opposite trend to that of the fragmentation scenario of Sect. 4.4. One can see that for a density

n1 ~ 1 cm-3 the re-acceleration gives a

small contribution to the total CR flux. In contrast, for

n1 ≲ 0.01 cm-3, the re-acceleration fraction

grows significantly (≳few percent). However it is also important the subsequent ST phase,

where the SNR shock expands adiabatically as

Rsh(t) ∝ t2/5,

slowing down at the rate

u1(t) = t−3/5.

is the mean mass of the ambient gas. Thus

Nre/Nbg ∝ 1/n1,

which is an opposite trend to that of the fragmentation scenario of Sect. 4.4. One can see that for a density

n1 ~ 1 cm-3 the re-acceleration gives a

small contribution to the total CR flux. In contrast, for

n1 ≲ 0.01 cm-3, the re-acceleration fraction

grows significantly (≳few percent). However it is also important the subsequent ST phase,

where the SNR shock expands adiabatically as

Rsh(t) ∝ t2/5,

slowing down at the rate

u1(t) = t−3/5.

Using the SNR parameters of Table 2, we computed

the re-accelerated CR spectra as in Sect. 2.2, using

Qreac = fbg(p)δ(x),

where  . Since CRs are already supra-thermal, we

assumed that all CR particles above pinj are suitable for

(re-)undergoing DSA. We note that N(p) is the DHM

solution of Eq. (22) that, in turn, is fed

by the total DSA spectra. Hence, we solved the DSA and DHM equation systems iteratively.

At the first iteration, only the standard injection term was considered (Eq. (12)) to compute the interstellar flux

N for all CR nuclei. The subsequent iterations made use of the previous

DHM solutions, N, to update the terms Qpri

and Qreac and to re-compute the total interstellar fluxes. The

procedure was iterated until the convergence was reached. At each iteration, the injection

constants, Y, were re-adjusted. The resulting CR flux (standard plus

re-accelerated) was therefore determined by Eq. (18) and is fully specified by the source parameters

n1 and τsnr. In practice, we

found that five iterations ensure a stable solution. The effect of re-acceleration is

shown in Fig. 5 for the SNR model CC #2 of

Table 2. At energies of

~1 TeV nucleon-1, the re-accelerated component dominates over the

ISM-induced component for secondary nuclei. It should be noted that the sources of

re-accelerated CRs may have a complex spatial distribution depending on the SNR spatial

profile. In our model, we used a uniform distribution,

s(r) ≡ 1, which does not limit the predicting power

of diffusion models as long as the key parameters are regarded as effective quantities

tuned to agree with the data (Maurin et al. 2001).

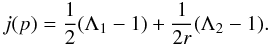

However, further elaborations would require more refined descriptions. In Fig. 6, we plot the fit results for the parameters

δ and K0/L for the

core-collapse SNR models of Table 2 and the

reference model. Compared to the scenario of Sect. 4.4, the results are less trivial to interpret because the background

CR flux that is subjected to re-acceleration itself depends on the parameters

δ and K0/L. As consequence

of this non-linearity, the K0/L best-fit

values results are less sensitive to n1. The results for

δ are qualitatively similar to those of Sect. 4.4, showing an opposite dependence on n1.

For the SNR model CC # 1 (n1 = 0.003 cm-3, left

column), the source component dominates the secondary CR flux at

~100 GeV nucleon-1, so that, at higher energies, the B/C ratio becomes

appreciably flat. The effect becomes less significant for higher background densities,

e.g., CC # 1 (n1 = 0.1 cm-3, right column) where

the best-fit parameters are close to those arising from the reference model

fit. As for the scenario of Sect. 4.4,

results are limited by the sizable uncertainties in the parameters that preclude

quantitative conclusions for

Emin = 10 GeV nucleon-1. Nonetheless, the figure

shows clear trends, especially for δ. The

χ2/d.f. values reported in each panel indicates that good fits

can be made for all the considered configurations, though they do not vary significantly

among the various SNR models.

. Since CRs are already supra-thermal, we

assumed that all CR particles above pinj are suitable for

(re-)undergoing DSA. We note that N(p) is the DHM

solution of Eq. (22) that, in turn, is fed

by the total DSA spectra. Hence, we solved the DSA and DHM equation systems iteratively.

At the first iteration, only the standard injection term was considered (Eq. (12)) to compute the interstellar flux

N for all CR nuclei. The subsequent iterations made use of the previous

DHM solutions, N, to update the terms Qpri

and Qreac and to re-compute the total interstellar fluxes. The

procedure was iterated until the convergence was reached. At each iteration, the injection

constants, Y, were re-adjusted. The resulting CR flux (standard plus

re-accelerated) was therefore determined by Eq. (18) and is fully specified by the source parameters

n1 and τsnr. In practice, we

found that five iterations ensure a stable solution. The effect of re-acceleration is

shown in Fig. 5 for the SNR model CC #2 of

Table 2. At energies of

~1 TeV nucleon-1, the re-accelerated component dominates over the

ISM-induced component for secondary nuclei. It should be noted that the sources of

re-accelerated CRs may have a complex spatial distribution depending on the SNR spatial

profile. In our model, we used a uniform distribution,

s(r) ≡ 1, which does not limit the predicting power

of diffusion models as long as the key parameters are regarded as effective quantities

tuned to agree with the data (Maurin et al. 2001).

However, further elaborations would require more refined descriptions. In Fig. 6, we plot the fit results for the parameters

δ and K0/L for the

core-collapse SNR models of Table 2 and the

reference model. Compared to the scenario of Sect. 4.4, the results are less trivial to interpret because the background

CR flux that is subjected to re-acceleration itself depends on the parameters

δ and K0/L. As consequence

of this non-linearity, the K0/L best-fit

values results are less sensitive to n1. The results for

δ are qualitatively similar to those of Sect. 4.4, showing an opposite dependence on n1.

For the SNR model CC # 1 (n1 = 0.003 cm-3, left

column), the source component dominates the secondary CR flux at

~100 GeV nucleon-1, so that, at higher energies, the B/C ratio becomes

appreciably flat. The effect becomes less significant for higher background densities,

e.g., CC # 1 (n1 = 0.1 cm-3, right column) where

the best-fit parameters are close to those arising from the reference model

fit. As for the scenario of Sect. 4.4,

results are limited by the sizable uncertainties in the parameters that preclude

quantitative conclusions for

Emin = 10 GeV nucleon-1. Nonetheless, the figure

shows clear trends, especially for δ. The

χ2/d.f. values reported in each panel indicates that good fits

can be made for all the considered configurations, though they do not vary significantly

among the various SNR models.

4.6. Summary and discussion

Our breakdown into Type I/a and core-collapse SNR scenarios is motivated by the complementary dependence of the two effects on n1. As seen in Sects. 4.4 and 4.5, the CR re-acceleration is found to be important for SNRs exploding into rarefied media, which are typical of super-bubbles (including our own local bubble), while the secondary production in SNRs is relevant for ambient densities similar to those of the regular ISM. Our calculations of the B/C ratio are in substantial agreement with the work of Berezhko et al. (2003) in the cases where the comparison can be made, though those authors used different approaches to model the acceleration as well as the interstellar propagation. The fit results for the SNR models of Table 2 and the reference model are listed in Table 3.

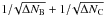

Figure 7 summarizes our findings, showing the best-fit parameters as functions of the SNR circumstellar density. The panel groups (a), (b), and (c) are referred to fits performed at different minimal energies, Emin = 10, 5, and 2 GeV nucleon-1, respectively. For each group, we report δ, K0/L, and χ2/d.f. as functions of n1 (from bottom to top, solid lines). The two mechanisms are presented separately: the sub-panels on the left-hand side show the effect of re-acceleration in CC type SNRs, while the right-hand side plots are referred to the secondary production by spallations in Type I/a SNRs. The complementarity of the two effects is apparent from the figure. In the region where they overlap, n1 ≈ 0.5 cm-3, neither is relevant. The horizontal (dotted) lines indicate the best-fit parameters for the reference model. Their dependence on Emin resembles that found in Di Bernardo et al. (2010), who also considered diffusive reacceleration models, although we note that we used a different set of data for the parameter determination. As discussed, the reference model is insensitive to either n1 or other SNR parameters. The dashed lines indicate the parameter uncertainties (at one σ of CL) arising from the fits.

|

Fig. 6 Fit results for the parameters δ and K0/L of our models with re-acceleration in core-collapse SNRs. Results are shown for Emin = 2, 5, and 10 GeV nucleon-1 (top to bottom), for the SNR models CC # 1, # 2, and # 3 of Table 2 and for the reference model (left to right). The shaded areas represent the 1-, 2-, and 3-σ contour limits. The markers “ × ” indicate the best-fit parameters for each configuration; the χ2/d.f. ratio is reported in each panel. |

|

Fig. 7 Best-fit parameters δ and K0/L and the corresponding χ2/d.f. as function of n1 (solid lines) for models with re-acceleration in core-collapse SNRs (CC, left sub-panels) and with hadronic interactions in Type I/a SNRs (I/a, right sub-panels). The panel groups a), b) and c) show the fit results for data at Emin = 1, 10, 5, and 2 GeV nucleon-1, respectively, for τsnr = 20 kyr. Panel d) shows the results for τsnr = 10, 20, 40, 60, and 80 kyr in the case of Emin = 2 GeV nucleon-1. The horizontal dotted lines indicate the reference model parameters. |

It is interesting to note the evolution of the best-χ2 structures when the minimal energy Emin is decreased from 10 GeV nucleon-1 (Fig. 7a) to 2 GeV nucleon-1 (Fig. 7c). When the low-energy B/C data are included in the fits, the χ2/d.f. distribution exhibits two minima. The B/C ratio data at low energies favor a slope (δ ~ 0.6), which is somewhat steeper than that observed in high energy data (δ ~ 0.4): these two regimes are matched by models of SNRs that emit secondary nuclei. In some previous studies, e.g. Trotta et al. (2011), it has been found that the secondary-to-primary ratios can be reproduced well at all energies using δ = 1/3 and a strong diffusive reacceleration (the interstellar Alfvénic speed is of the order of ~30 km s-1). However, this cannot be satisfactorily reconciled with the use of pure power-law functions for the CR sources. On the other hand, the trends we observe suggest a possible role of SNR-fragmentation or re-acceleration in reconciling the low-energy B/C data with those at higher energies in a pure diffusion scenario.

As we have stressed, the physical effects discussed in this work should be tested at high energies, where most of the complexity of the low-energy CR propagation can be neglected. Owing to the scarcity of CR data above 10 GeV nucleon-1, the parameter constraints reported in Fig. 7a do not allow us to make any firm discrimination among the different SNR models. However, the main trends are apparent. On the propagation side, all the non-standard scenarios point toward larger values for δ, which is in some tensions with the predictions for the interstellar turbulence (Strong et al. 2007) and with CR anisotropy studies (Ptuskin et al. 2006). On the acceleration side, large values of δ reduce the source spectral index closer to the value ν = 2, which is favored by the DSA theory for strong shocks.

In all these scenarios, the acceleration ceases at

τsnr = 20 kyr, which may not be the case given their

different SNR evolutionary properties. For instance, since the ST phase duration scales as

(Truelove

& McKee 1999), one may expect core-collapse SNRs to have longer

τsnr than Type I/a SNRs. However, the parameter

τsnr represents the time for which the SNR is active as a CR

factory and it can be extremely difficult to estimate. Thus, in Fig. 7d, we give the fit results for different values of

τsnr from 10 kyr to 80 kyr

(Emin = 2 GeV nucleon-1). The effect of using

different τsnr is clear. The longer the time for which the SNR

is active, the larger the fragments produced in its interior. In practice, the secondary

CRs production in Type I/a SNRs is characterized by the product

n1τsnr. For re-acceleration, a

longer lifetime allows the SNR to occupy larger volumes. To first approximation, the

intensity of re-accelerated nuclei increases as

~τsnr/n1. As shown in the

figure, for longer values of τsnr, the re-acceleration effect

also becomes important for relatively high density media.

(Truelove

& McKee 1999), one may expect core-collapse SNRs to have longer

τsnr than Type I/a SNRs. However, the parameter

τsnr represents the time for which the SNR is active as a CR

factory and it can be extremely difficult to estimate. Thus, in Fig. 7d, we give the fit results for different values of

τsnr from 10 kyr to 80 kyr

(Emin = 2 GeV nucleon-1). The effect of using

different τsnr is clear. The longer the time for which the SNR

is active, the larger the fragments produced in its interior. In practice, the secondary

CRs production in Type I/a SNRs is characterized by the product

n1τsnr. For re-acceleration, a

longer lifetime allows the SNR to occupy larger volumes. To first approximation, the

intensity of re-accelerated nuclei increases as

~τsnr/n1. As shown in the

figure, for longer values of τsnr, the re-acceleration effect

also becomes important for relatively high density media.

5. The projected AMS-02 sensitivity

We switch now to some estimations for the AMS experiment1, which is devoted to direct measurements of Galactic CRs across a wide range of energy.

|

Fig. 8 AMS-02 mock data for the elemental fluxes φB and φCa) and their ratio b), using the input model CC # 2 of Table 2 and assuming a detector exposure factor F = 150 m2 sr day. The error bars are only statistics. The constraints to the transport parameters provided by the AMS-02 mock data are reported by the 3-σ contour levels for exposure factors of F = 12, 36, and 150 m2 sr day in c) and d). The data are fitted within the reference model (star in panel c) and dotted line in panel b)) and within the model CC # 2 (cross in panel d) and solid line in panel b)). The AMS-02 discrimination probability between the two models as a function of the systematic error in the measurement is shown in d) for F = 12, 36, and 150 m2 sr day. The systematic errors are assumed to be energy-independent. |

The prime goals of the AMS project are the direct search for anti-nuclei and the indirect search for dark matter particles. The first version of the experiment, AMS-01, operated in a test flight on June 1998. The final version of experiment, AMS-02, was successfully installed in the International Space Station on May 2011 and will be active for at least ten years. AMS-02 is able to identify CR elements from Z = 1 to Z = 26 and to determine their energy spectra from ~0.5 GeV to ~1 TeV per nucleon with unprecedented accuracy. We estimate the AMS-02 capabilities in determining the CR propagation properties for the considered scenarios.

5.1. Projected data

The AMS-02 sensitivity to CR nuclei measurements is studied by the generation of

mock data for a given input model. The number of

j-type particles recorded by AMS-02 at the kinetic energies between

E1 and E2 is given by

(27)where

φj is the input spectrum,

(27)where

φj is the input spectrum,

is the detector geometric factor, ℰj is the detection

efficiency, and

is the detector geometric factor, ℰj is the detection

efficiency, and  is the exposure time. All of these quantities are in general energy-dependent and

particle-dependent. The relevant quantity for our estimates is the exposure factor

is the exposure time. All of these quantities are in general energy-dependent and

particle-dependent. The relevant quantity for our estimates is the exposure factor

,

which we assume to be both energy and particle independent. We consider the cases of

ℱ = 12, 36, and 150 m2 sr day. For values of, e.g.,

,

which we assume to be both energy and particle independent. We consider the cases of

ℱ = 12, 36, and 150 m2 sr day. For values of, e.g.,

0.45 m2 sr

and ℰ = 90%, our choices correspond to one month, three months and one year of time

exposures, respectively. We adopt a log-energy binning using nine bins per decade

between 10 GeV and 1 TeV per nucleon. The AMS-02 mock data for the B and C fluxes and

their ratios are shown in Figs. 8a and b. The

CR fluxes, φB and

φC, are calculated using the SNR model

CC # 2 (Table 2) as an input model. This “true”

model is characterized by the SNR parameters

n1 = 0.01 cm-3 and

τsnr = 20 kyr, and transport parameters

K0/L = 0.01847 kpc Myr-1 and

δ = 0.57. From Eq. (27), we compute the statistical error in each B/C data point as

0.45 m2 sr

and ℰ = 90%, our choices correspond to one month, three months and one year of time

exposures, respectively. We adopt a log-energy binning using nine bins per decade

between 10 GeV and 1 TeV per nucleon. The AMS-02 mock data for the B and C fluxes and

their ratios are shown in Figs. 8a and b. The

CR fluxes, φB and

φC, are calculated using the SNR model

CC # 2 (Table 2) as an input model. This “true”

model is characterized by the SNR parameters

n1 = 0.01 cm-3 and

τsnr = 20 kyr, and transport parameters

K0/L = 0.01847 kpc Myr-1 and

δ = 0.57. From Eq. (27), we compute the statistical error in each B/C data point as

. Nonetheless, CR measurements are also

affected by systematic errors, which become increasingly important as the precision

increases with the collected statistics.

. Nonetheless, CR measurements are also

affected by systematic errors, which become increasingly important as the precision

increases with the collected statistics.

5.2. Discrimination power

We fit the B/C ratio mock data leaving K0/L and δ as free parameters. These parameters are determined within both the reference model (re-acceleration off) and the “true” re-acceleration model CC # 2 of Table 2. As shown in Fig. 8b, both the models can be tuned to reproduce the AMS-02 mock data, but they exhibit different functional shapes and deviate at high energies. The contour plots in panels (c) and (d) correspond to the best-fit parameters of the two models. Contour levels are shown for 3-σ uncertainty levels corresponding to the three exposure factors ℱ. As expected, the re-acceleration model fit (d) returns the correct parameters, while the reference model fit (c) misestimates the parameters because of inaccurate assumptions about the source properties. In fact, when the reference model is forced to describe the data, the spectral distortion induced by the re-acceleration is mimicked by the use of a lower value for δ. Given the precision of the AMS-02 data, this represents the dominant “error” in the parameter determination. As apparent from the figure, the AMS-02 data place tight constraints on the propagation parameters. For instance, δ is determined to a precision better than ≲10% within a 3–σ uncertainty level. The δ–n1 degeneracy may be lifted as in Castellina & Donato (2005), i.e., by a statistical test to discriminate between the two fits. As long as only statistical errors are considered, we find that the discrimination between the two scenarios is always possible for the three considered exposures at 90% of CL. The effect of systematic errors in the data is shown in Fig. 8e, where we plot the AMS-02 discrimination probability versus the relative systematic error. Our calculation assumes constant systematic errors (added in quadrature to the statistical ones), but these considerations also hold for energy-dependent systematic errors if their energy rise is less pronounced than the statistical errors. The solid, dashed, and dotted lines represent the cases of ℱ = 12, 36, and 150 m2 sr day, respectively. To achieve a discrimination of 90% CL, the systematic error has to be smaller than ~4%, 8%, and 10% for the three considered exposures. A 95% CL requirement also needs ℱ to be larger than 12 m2 sr day. We consider these requirements as reasonable for AMS-02, because the measurements of elemental ratios are only mildly sensitive to systematic errors.

|

Fig. 9 AMS-02 discrimination power for models with secondary production in SNRs. Each point in the (n1,δ)-plane represents an input model with fragmentation inside SNRs with τsnr = 20 kyr. The parameter K0/L is taken to match the existing B/C ratio data. The shaded areas cover the parameter region where AMS-02 is sensitive at 95% CL for the exposure ℱ = 12, 36, and 150 m2 sr day. The systematic errors are assumed to be 5% of the measured B/C and constant in energy. |

Similar conclusions can be drawn for models with fragmentation in SNRs. In this case, we

have explored a large region of the parameter space

n1–δ, with δ = 0.3–0.8

and n1 = 0–5 cm-3. Our estimate was carried out as

follows. For each { n1,δ } parameter

combination, we determined K0/L from fits to

the existing B/C ratio data. Then we defined the true model

using { n1,τsnr } as source

parameters and { δ, K0/L }

as transport parameters. From the true model, we generated the AMS-02 mock data for a

given exposure factor, ℱ, and a 5% systematic error. Thus, we re-fit the mock B/C ratio,

leaving K0/L and δ as free

parameters, within both the reference model and the true SNR scenario

(fragmentation specified by n1). Finally, we estimate the

AMS-02 discrimination probability for the two models. The shaded areas of Fig. 9 indicate the parameter region where the AMS-02

discrimination succeeds at 95% CL for ℱ = 12, 36, and 150 m2 sr day. The

figure shows that AMS-02 is sensitive to a large region of the parameter space, except for

small n1 values (small secondary SNR component) and/or small

δ values (hard ISM component), when the intensity of the secondary

source component is too weak to induce appreciable biases in the propagation parameters.

This is also the case for Kolmogorov-like diffusion (δ = 1/3), which,

however, is disfavored by our analysis of the real data. These considerations can be much

strengthened if one considers the independent constraints that may be brought by other

AMS-02 data such as, for example, the ratios  , Li/C, F/Ne, or Ti/Fe. In summary, our

estimates show that AMS-02 performs wel in determining the CR transport parameters,

providing tight constraints and considerable progress in understanding the CR acceleration

and propagation processes.

, Li/C, F/Ne, or Ti/Fe. In summary, our

estimates show that AMS-02 performs wel in determining the CR transport parameters,

providing tight constraints and considerable progress in understanding the CR acceleration

and propagation processes.

6. Conclusions