| Issue |

A&A

Volume 534, October 2011

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A116 | |

| Number of page(s) | 8 | |

| Section | The Sun | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201116982 | |

| Published online | 18 October 2011 | |

Proton firehose instability in bi-Kappa distributed plasmas

1

Center for Plasma Astrophysics, Celestijnenlaan 200B,

3001

Leuven,

Belgium

e-mail: marian.lazar@wis.kuleuven.be

2

Institut für Theoretische Physik, Lehrstuhl IV: Weltraum- und

Astrophysik, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, 44780

Bochum,

Germany

Received:

30

March

2011

Accepted:

21

June

2011

Context. Protons or heavier ions with anisotropic velocity distributions and non-thermal departure from Maxwellian, are frequently reported in the magnetosphere and at different altitudes in the solar wind. These observations are sustained by an extended number of mechanisms of acceleration in any direction with respect to the interplanetary magnetic field. However, the observed anisotropy is not large and most probably constrained by the kinetic instabilities.

Aims. An excess of parallel kinetic energy, T∥/T⊥ > 1 (where ∥ and ⊥ denote directions relative to the background magnetic field) drives a proton firehose mode to grow, limiting any further increase in the anisotropy according to the observations. The effects of suprathermal populations on the principal characteristics of the proton firehose instability are investigated.

Methods. For low-collisional plasmas, the dispersion approach is based on the fundamental kinetic Vlasov-Maxwell equations. The anisotropy of plasma distributions including suprathermal populations is modeled by bi-Kappa functions, and the new dispersion relations are derived in terms of the modified plasma dispersion function (for Kappa distributions), and analytical approximations of this function.

Results. Growth rates of the proton firehose solutions and threshold conditions are provided in analytical forms for different plasma regimes. The proton firehose instability needs a larger anisotropy and a larger parameter β∥ to occur in a Kappa-distributed plasma. A precise numerical evaluation shows that the growth rates are, in general, lower and the wave frequency is only slightly affected, but the influence of suprathermal populations is essentially dependent on both the proton and electron anisotropies. Departures from the standard dispersion of a Maxwellian plasma can eventually be used to evaluate the presence of suprathermal populations in solar flares and the magnetosphere.

Key words: Sun: flares / plasmas / solar wind / instabilities / Sun: coronal mass ejections (CMEs)

© ESO, 2011

1. Introduction

Kinetic instabilities prevail in the solar wind (Cairns et al. 2000; Bale et al. 2009) as it is a dilute plasma that contains ample free energy, localized in flows, and a nonuniform heating (Marsch 2006; Bougeret & Pick 2007). In a poor-collisional plasma, these instabilities provide a plausible mechanism to prevent the development of excessive anisotropies and ensure a more fluid-like behavior (Hellinger et al. 2006; Stverak et al. 2008). Moreover, the electromagnetic wave turbulence leads to acceleration and pitch-angle scattering and diffusion, and must therefore play an important role in the evolution of plasma particles in the solar wind and the magnetosphere (Dröge 2003; Schlickeiser et al. 2010; Pierrard et al. 2011)

Measurements of the plasma parameters at high altitudes in the solar wind (≲ 1 AU) closely agree with theoretical and numerical predictions (Gary et al. 1976; Quest & Shapiro 1996; Gary et al. 1998; Hellinger & Matsumoto 2000; Matteini et al. 2006) showing that any increase in the parallel proton temperature is constrained by the proton firehose instability (PFHI) (Kasper et al. 2002; Hellinger et al. 2006; Bale et al. 2009). This instability is driven by an excess of the parallel kinetic energy, i.e. temperature Tp,∥ > Tp,⊥ or pressure p∥ > p⊥, and develops from a right-handed (RH) circularly polarized mode with a maximum growth rate at parallel propagation, i.e., k × B0 = 0. The mechanism that converts the kinetic energy of the protons and excites the firehose instability is essentially non-resonant, or fluid-like (Parker 1958; Pilipp & Völk 1971; Yoon 1995; Wang & Hau 2003). For a finite thermal spread, it has already been shown that resonant particles can also play an important role enhancing or suppressing the instability (Pilipp & Völk 1971; Gary et al. 1998), and shaping the proton distribution function to depart from the bi-Maxwellian form (Matteini et al. 2006). Resonant terms can, therefore, be considered whenever their contribution is expected to be significant.

Protons or heavier ions with suprathermal distributions have frequently been observed in the solar wind (Collier et al. 1996; Chotoo et al. 2000), the magnetosphere (Gloeckler & Hamilton 1987), or further in the heliosphere towards the termination shock (Decker et al. 2005; Fisk & Gloeckler 2007). There is abundant observational evidence indicating that particle energization and the occurrence of suprathermal populations are correlated with an enhanced activity of the waves and instabilities in space plasma. A brief description of these mechanisms of acceleration can be found in the review (referred to in Sect. 3) by Pierrard & Lazar (2010). Populations with suprathermal high-energy tails are most accurately modeled by the family of Kappa functions (Vasyliunas 1968; Summers & Thorne 1991), and may exhibit different wave dispersion and stability properties from a Maxwellian (Pierrard & Lazar 2010). Electrons with a surplus of parallel kinetic energy, Te,∥ > Te,⊥, initiate the electron firehose instability (EFHI) of the low-frequency left-handed (LH) circularly polarized modes propagating parallel to the magnetic field. Modeling the anisotropy of suprathermal electrons with a bi-Kappa distribution, Lazar & Poedts (2009) demonstrated that, compared to a bi-Mawellian, the threshold of the EFHI increases, the maximum growth rates are slightly diminished, and the instability extends to large wave numbers.

The PFHI is also a low-frequency growing mode but with a RH circular polarization, and is driven by the non-resonant protons with Tp,∥ > Tp,⊥. Under the usual convention, protons resonate more easily with LH modes driving a proton cyclotron instability if Tp,∥ < Tp,⊥. However, for an intense magnetization in low-β plasmas, the same resonant protons can also cause the instability of the RH modes to grow. In this case, the growth rates are usually much lower than the proton gyrofrequency, but they can increase (by a few orders of magnitude), approaching the proton gyrofrequency as the abundance of the suprathermal protons increases (Xue et al. 1993; Dasso et al. 2003). In addition, we consider large-β plasmas where deviations of the protons from an isotropic Maxwellian equilibrium can easily develop and drive the PFHI.

2. Parallel RH transverse modes in bi-Kappa plasmas

We start from the general dispersion relation of the transverse modes propagating

along the regular magnetic field with a RH circular polarization, e.g.,

Eq. (2) from Lazar & Poedts (2009), hereafter

called Paper I, ![\begin{eqnarray} 1 - {k^2c^2 \over \omega^2} && + {\pi \over \omega^2} \sum_a \omm_{{\rm p},a}^2 \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \, {{\rm d}v_{\parallel} \over \omm - k v_{\parallel} + \Omega_a} \notag \\ \label{e1}\times && \int_0^{\infty} \, {\rm d}v_{\perp} v_{\perp}^2 \left[(\omm - k v_{\parallel}) {\partial F_{a,\kappa} \over \partial v_{\perp}} + k v_{\perp} {\partial F_{a,\kappa} \over \partial v_{\parallel}} \right] = 0, \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2011/10/aa16982-11/aa16982-11-eq13.png) (1)where

ω and k denote the frequency and the wave number of the

plasma modes, respectively, c is the speed of light in a vacuum,

Ωa = qaB0/(mac)

is the (non-relativistic) gyrofrequency, and

ωp,a = (4πnae2/ma)1/2

is the plasma frequency for the particles of species a. We use polar

coordinates in the particle velocity space

(1)where

ω and k denote the frequency and the wave number of the

plasma modes, respectively, c is the speed of light in a vacuum,

Ωa = qaB0/(mac)

is the (non-relativistic) gyrofrequency, and

ωp,a = (4πnae2/ma)1/2

is the plasma frequency for the particles of species a. We use polar

coordinates in the particle velocity space  (2)The initial unperturbed

plasma anisotropy is modeled with a bi-Kappa velocity distribution function of plasma

particles

(2)The initial unperturbed

plasma anisotropy is modeled with a bi-Kappa velocity distribution function of plasma

particles ![\begin{equation} F_{\kappa} = {1 \over \pi^{3/2} \theta_{\perp}^2 \theta_{\parallel}} \, {\Gamma (\kappa + 1) \over \kappa^{3/2} \Gamma(\kappa -1/2)} \, \Biggl[1 + {v_{\parallel}^2 \over \kappa \theta_{\parallel}^2} + {v_{\perp}^2 \over \kappa \theta_{\perp}^2}\Biggr]^{-\kappa -1} \label{e3}, \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2011/10/aa16982-11/aa16982-11-eq21.png) (3)which is normalized by

(3)which is normalized by

. Here,

. Here,  (4)with

(4)with  (5)and

(5)and  (6)denote the

perpendicular and parallel thermal velocities, respectively. The bi-Kappa distribution

function given in Eq. (4) was introduced by

Summers & Thorne (1991) to describe

anisotropies of suprathermal populations, and it approaches a bi-Maxwellian as the spectral

index κ (<3/2) reaches very

large values κ → ∞.

(6)denote the

perpendicular and parallel thermal velocities, respectively. The bi-Kappa distribution

function given in Eq. (4) was introduced by

Summers & Thorne (1991) to describe

anisotropies of suprathermal populations, and it approaches a bi-Maxwellian as the spectral

index κ (<3/2) reaches very

large values κ → ∞.

Now we insert the distribution function in Eq. (3) into Eq. (1) and obtain the

general dispersion relation of the RH transverse modes in a bi-Kappa distributed plasma

![\begin{equation} 1- {k^2c^2 \over \omega^2} + \sum_a {\omega_{{\rm p},a}^2 \over \omega^2} \left\{ {\omega \over k \theta_{a, \parallel}}\, Z^0_{\kappa} (g_a) - A_a \, \left[1+ g_a Z^0_{\kappa} (g_a)\right] \right\} = 0. \label{e7} \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2011/10/aa16982-11/aa16982-11-eq30.png) (7)We use the modified

plasma dispersion function (Lazar et al. 2008a)

(7)We use the modified

plasma dispersion function (Lazar et al. 2008a)

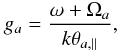

(8)with the argument

(a = e,p)

(8)with the argument

(a = e,p)  (9)and the temperature

anisotropy

(9)and the temperature

anisotropy  (10)In the limit of very large

values of κ → ∞, the modified plasma dispersion function given in Eq.

(8) converges to the standard dispersion

function of Fried & Conte (1961), and the

dispersion relation in Eq. (7) agrees exactly

with the dispersion relation derived for a Maxwellian plasma (Gary 1993).

(10)In the limit of very large

values of κ → ∞, the modified plasma dispersion function given in Eq.

(8) converges to the standard dispersion

function of Fried & Conte (1961), and the

dispersion relation in Eq. (7) agrees exactly

with the dispersion relation derived for a Maxwellian plasma (Gary 1993).

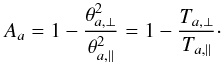

The newly modified dispersion function  was introduced by Lazar et al.

(2008a) to simplify the description of the

dispersion properties of the transverse modes and instabilities in Kappa distributed

plasmas. This function relates to the modified dispersion function

Zκ introduced by Summers & Thorne

(1991)

was introduced by Lazar et al.

(2008a) to simplify the description of the

dispersion properties of the transverse modes and instabilities in Kappa distributed

plasmas. This function relates to the modified dispersion function

Zκ introduced by Summers & Thorne

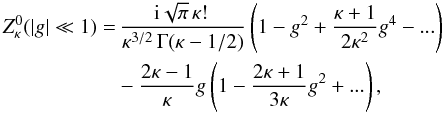

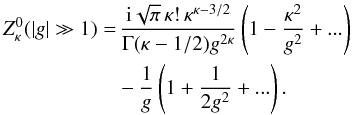

(1991)  (11)We simply use the small and

large argument expansions of Zκ (Summers

& Thorne 1991) to find for

(11)We simply use the small and

large argument expansions of Zκ (Summers

& Thorne 1991) to find for

(12)

(12) (13)Each

of the approximative forms given in Eqs. (12) and (13) of the modified

dispersion function in Eq. (8) contains a

principal part with an important contribution from the non-resonant particles, and an

imaginary part given by the analytical continuation for the resonant particles with

velocities satisfying cyclotron resonance conditions (of the first dominant order), i.e.,

|ga| ≃ 1,

a = e,p. Because the mechanism that excites the firehose

instability is essentially non-resonant, we can describe the EFHI/PFHI only by considering a

finite non-resonant contribution of the electrons/protons in the analytical approximations.

(13)Each

of the approximative forms given in Eqs. (12) and (13) of the modified

dispersion function in Eq. (8) contains a

principal part with an important contribution from the non-resonant particles, and an

imaginary part given by the analytical continuation for the resonant particles with

velocities satisfying cyclotron resonance conditions (of the first dominant order), i.e.,

|ga| ≃ 1,

a = e,p. Because the mechanism that excites the firehose

instability is essentially non-resonant, we can describe the EFHI/PFHI only by considering a

finite non-resonant contribution of the electrons/protons in the analytical approximations.

We can explicitly characterize the conditions for large or small arguments of

by restricting

ourselves to the lowest frequencies,

ωr < Ωp ≪ |Ωe|,

corresponding to modes excited by the proton firehose instability, and further simplifying

by considering two distinct cases:

by restricting

ourselves to the lowest frequencies,

ωr < Ωp ≪ |Ωe|,

corresponding to modes excited by the proton firehose instability, and further simplifying

by considering two distinct cases:

-

(a)

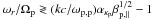

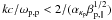

ωi < ωr (<Ωp ≪ |Ωe|) when |ge| ≷ 1 implies that kc/ωp,p ≶ (1/ακe) [mp/(meβe,∥)] 1/2, and |gp| ≷ 1 implies

. In the limit of a

small ωr < Ωp, both

arguments are large, |ge| > 1 and

|gp| > 1, only for small wave numbers

. In the limit of a

small ωr < Ωp, both

arguments are large, |ge| > 1 and

|gp| > 1, only for small wave numbers

.

Here, we introduced

.

Here, we introduced  ,

a = e,p;

,

a = e,p; -

(b)

ωr < ωi (<Ωp ≪ |Ωe|), when |ge| ≷ 1 implies the same kc/ωp,p ≶ (1/ακe) [mp/(meβe,∥)] 1/2, and |gp| ≷ 1 implies

![\hbox{$\omega_i /\Omega_{\rm p} \gtrless [(kc/\omega_{\rm p,p})^2 \alpha_{\kappa_{\rm p}}^2 \beta_{\rm p, \parallel}- 1]^{1/2}$}](/articles/aa/full_html/2011/10/aa16982-11/aa16982-11-eq60.png) . In

the limit of a small

ωi < Ωp, both

arguments are large, |ge| > 1 and

|gp| > 1, only for small wave numbers

. In

the limit of a small

ωi < Ωp, both

arguments are large, |ge| > 1 and

|gp| > 1, only for small wave numbers

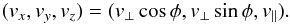

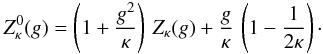

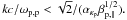

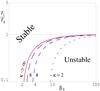

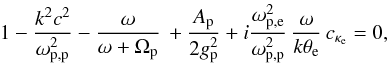

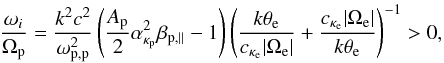

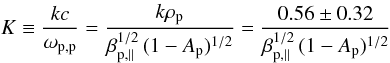

The spectral domains where the approximations given in Eqs. (12) and (13) apply are displayed in Fig. 1a and b, in a dispersion frequency versus wave number diagram. Four regions are delimited by the resonance curves shown with dashed lines for protons and dotted lines for electrons: region R1 for |gp,e| > 1, region R2 for |ge| > 1 and |gp| < 1, region R3 for |ge,p| < 1, and, finally, region R4 for |ge| < 1 and |gp| > 1.

|

Fig. 1 Spectral domains R1–R4, where the approximations given in Eqs. (12) and (13) of the modified plasma dispersion function (8) can be used. For a dominance of suprathermal populations, indices κa → 1/2, and ακa → 0 increasing (meακeβe,∥/mp)−1/2 and (ακpβp,∥)−1/2 to very large values, and also enlarging the area where the arguments |ga| > 1 are large enough to apply the approximation in Eq. (13) for both species a = e,p, (Wr,i = ωr,i/Ωp, K = kc/ωp,p). |

The suprathermal populations are in general described by small values of the index

κ → 3/2 in the distribution function in Eq. (3). In this case,

ακa → 0 also

becomes very small causing the cutoffs of the resonance conditions

and

and

to reach very

large values. The region R1, where

|ga| > 1 for both

species a = e,p, can extend considerably to dominate the

other regions, where the arguments are smaller

(| ga| < 1). This

is the first important result of the present paper proving that in Kappa-distributed

plasmas, the arguments of the modified dispersion function become sufficiently large,

|ga| > 1, for a

large variety of plasma parameters, wave numbers, and frequencies, and that the

approximation derived in Eq. (13) enables a

simple analytical description of the unstable modes.

to reach very

large values. The region R1, where

|ga| > 1 for both

species a = e,p, can extend considerably to dominate the

other regions, where the arguments are smaller

(| ga| < 1). This

is the first important result of the present paper proving that in Kappa-distributed

plasmas, the arguments of the modified dispersion function become sufficiently large,

|ga| > 1, for a

large variety of plasma parameters, wave numbers, and frequencies, and that the

approximation derived in Eq. (13) enables a

simple analytical description of the unstable modes.

3. Proton firehose instability

Additional analytical derivations of the dispersion Eq. (7) can be easily undertaken to provide a detailed characterization of the

PFHI for specific plasma regimes. Thus, it is obvious to consider either the limit of small

temperatures (or small wave-numbers) when the argument of

is large enough

(| ga| ≫ 1) for the approximation in

Eq. (13) to be applicable, or the opposite

limit of large temperatures (or large wave-numbers) when the argument becomes small

(| ga| ≪ 1) and the approximation in

Eq. (12) applies.

is large enough

(| ga| ≫ 1) for the approximation in

Eq. (13) to be applicable, or the opposite

limit of large temperatures (or large wave-numbers) when the argument becomes small

(| ga| ≪ 1) and the approximation in

Eq. (12) applies.

3.1. Cold fluid-like plasma (small wave numbers)

In this limit, both arguments are supposed to be very large, i.e.

|ga| ≫ 1 (with

a = e,p), and if we neglect the contribution of

resonant particles, the modified plasma dispersion function in the approximative form

given in Eq. (13) does not depend

explicitly on the spectral index κ (cf. Paper I), and the dispersion

relation (7) reduces to ![\begin{equation} {\omega^2 \over \Omega_{\rm p}^2} = {k^2c^2 \over \omega_{\rm p,p}^2} \left[1- {A_{\rm e} \over 2} \alpha_{\kappa_{\rm e}}^2 \beta_{{\rm e},\parallel} -{A_{\rm p} \over 2} \alpha_{\kappa_{\rm p}}^2 \beta_{{\rm p},\parallel}\right]. \label{e14} \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2011/10/aa16982-11/aa16982-11-eq82.png) (14)We have assumed that for

small wave numbers (real or imaginary) the frequencies are also sufficiently small,

ω2 ≪ k2c2

and ω ≪ Ωp ≪ |Ωe|. With

βe,∥ = (Te,∥/Tp,∥)βp,∥,

we simply find that in the limit of very large κ → ∞ (when

ακ → 1), the dispersion relation in

Eq. (14) agrees exactly with that

derived by Pilipp & Völk (1971, see

Eq. (3.3)) for a bi-Maxwellian plasma.

(14)We have assumed that for

small wave numbers (real or imaginary) the frequencies are also sufficiently small,

ω2 ≪ k2c2

and ω ≪ Ωp ≪ |Ωe|. With

βe,∥ = (Te,∥/Tp,∥)βp,∥,

we simply find that in the limit of very large κ → ∞ (when

ακ → 1), the dispersion relation in

Eq. (14) agrees exactly with that

derived by Pilipp & Völk (1971, see

Eq. (3.3)) for a bi-Maxwellian plasma.

An instability is expected to occur for  (15)i.e. when the dispersion

relation in Eq. (14) admits purely growing

solutions. This is the threshold condition of the firehose instability in the limit of

small wave numbers or a sufficiently cold, fluid-like plasma model. In this limit, the two

branches of LH and RH modes overlap, both being described by the same dispersion relation

given in Eq. (14) and the same threshold

condition in Eq. (15), and where the

non-resonant character of this instability is most clearly revealed by cumulating the

effects of both anisotropic components, electrons, and ions. Otherwise, if an instability

is resonantly growing because of the kinetic anisotropies of the plasma particles (see,

for instance, the cyclotron instabilities), the resonant enhancing effects from both

species cannot cumulate. Parker (1958) demonstrated

for the first time the existence of the firehose instability by considering a

(one-component) fluid model of anisotropic plasma with an excess of pressure parallel to

the magnetization field, and neglecting any resonances with plasma particles.

(15)i.e. when the dispersion

relation in Eq. (14) admits purely growing

solutions. This is the threshold condition of the firehose instability in the limit of

small wave numbers or a sufficiently cold, fluid-like plasma model. In this limit, the two

branches of LH and RH modes overlap, both being described by the same dispersion relation

given in Eq. (14) and the same threshold

condition in Eq. (15), and where the

non-resonant character of this instability is most clearly revealed by cumulating the

effects of both anisotropic components, electrons, and ions. Otherwise, if an instability

is resonantly growing because of the kinetic anisotropies of the plasma particles (see,

for instance, the cyclotron instabilities), the resonant enhancing effects from both

species cannot cumulate. Parker (1958) demonstrated

for the first time the existence of the firehose instability by considering a

(one-component) fluid model of anisotropic plasma with an excess of pressure parallel to

the magnetization field, and neglecting any resonances with plasma particles.

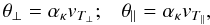

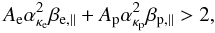

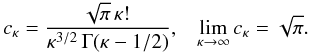

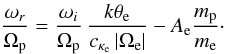

However, minimizing the role of collisions and assuming electrons and ions distributed after power laws of bi-Kappa type, here we find that both the growth rate and the threshold condition are sensitive to the shape of the distribution function exhibiting a strong dependence on the spectral index κ. The standard fluid-like model of the firehose instability is, therefore, recovered only in the Maxwellian limit of κ → ∞, when the plasma must be collisional and less tenuous. The growth rates are displayed in Fig. 2 for different values of the κ index, the temperature contrast, Te,∥/Tp,∥, and the plasma-β parameter.

|

Fig. 2 Growth rates of the firehose instability as provided by Eq. (14) for κe = 2, κp = 3 (dotted line), κe,p = 4 (dashed line), κe,p → ∞ (solid line), and plasma parameters: Te,∥/Te,⊥ = Tp,∥/Tp,⊥ = 4, a) Te,∥/Tp,∥ = 3, βe,∥ = 18; and b) Te,∥/Tp,∥ = 2, βe,∥ = 8. For a given wave-number value K = 0.03, the growth rate variation with κe and κp is shown in panel c). (Wi = ωi/Ωp, K = kc/ωp,p). |

When we compare the contributions of each species, electrons and protons, we find that

the mass contrast

me/mp (or

)

does not intervene (minimizing the contribution of the protons). It is, however, the

temperature contrast

Te,∥/Tp,∥

(<1, in the solar wind often in the favor of electrons) that

can lower the effect of protons, e.g., through

βp,∥ = (Tp,∥/Te,∥)βe, ∥ < βe,∥.

However, an important observation is that, in this limit (small wave-numbers), the effects

of both species, electrons and protons, are diminished in the presence of suprathermal

populations (small values of κe,p).

)

does not intervene (minimizing the contribution of the protons). It is, however, the

temperature contrast

Te,∥/Tp,∥

(<1, in the solar wind often in the favor of electrons) that

can lower the effect of protons, e.g., through

βp,∥ = (Tp,∥/Te,∥)βe, ∥ < βe,∥.

However, an important observation is that, in this limit (small wave-numbers), the effects

of both species, electrons and protons, are diminished in the presence of suprathermal

populations (small values of κe,p).

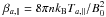

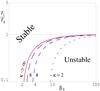

If the electrons are isotropic, i.e. Ae = 0, from the general

condition in Eq. (15) we find the

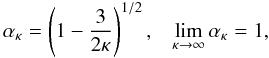

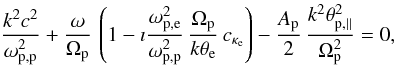

threshold condition for the PFHI  (16)where

(16)where

must be

sufficiently large. Alternatively, for isotropic protons, we substitute

Ap = 0 in Eq. (15) and find the threshold condition for the EFHI

must be

sufficiently large. Alternatively, for isotropic protons, we substitute

Ap = 0 in Eq. (15) and find the threshold condition for the EFHI  (17)assuming this time a

sufficiently large

(17)assuming this time a

sufficiently large  (for

instance, Eq. (5) provides

(for

instance, Eq. (5) provides

for

κ = 2, and

for

κ = 2, and  for

κ = 4). We note that the reproduction of Eq. (17) here corrects a typographical error in

Paper I, Eq. (22), where the threshold condition for the EFHI was derived for the first

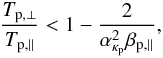

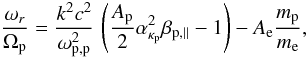

time. Both of these conditions in Eqs. (16) and (17) illustrate the need

for a larger kinetic anisotropy and a larger β∥ to produce

the instability in plasma with suprathermal populations. For comparison, the threshold

conditions for a Maxwellian plasma (κ → ∞) and different

low-κ plasmas are displayed in Fig. 3. We also note that in Fig. 2b no

instability grows for small values of κe = 1.8 and

κp = 2 because, for the given values of the plasma

parameters, the instability condition imposes a minimum limit value for the spectral index

κ (see Eq. (23) in Paper I).

for

κ = 4). We note that the reproduction of Eq. (17) here corrects a typographical error in

Paper I, Eq. (22), where the threshold condition for the EFHI was derived for the first

time. Both of these conditions in Eqs. (16) and (17) illustrate the need

for a larger kinetic anisotropy and a larger β∥ to produce

the instability in plasma with suprathermal populations. For comparison, the threshold

conditions for a Maxwellian plasma (κ → ∞) and different

low-κ plasmas are displayed in Fig. 3. We also note that in Fig. 2b no

instability grows for small values of κe = 1.8 and

κp = 2 because, for the given values of the plasma

parameters, the instability condition imposes a minimum limit value for the spectral index

κ (see Eq. (23) in Paper I).

When both species are anisotropic, i.e.

Ae,p ≠ 0, and exhibit suprathermal tails of

different shapes, (κe ≠ κp), the

general condition in Eq. (15) can be

rewritten in the same form as  (18)assuming this time a

sufficiently large

(18)assuming this time a

sufficiently large  .

.

|

Fig. 3 Threshold conditions for the EFHI (or the PFHI) as provided by Eq. (16) (or in Eq. (17)) for different

values κ. The instability occurs below the threshold lines for

|

3.2. Hot electrons – isotropic distribution, Ae = 0

Considering a plasma with anisotropic protons, Tp,∥ > Tp,⊥, and isotropic electrons, Te,⊥ = Te,∥, the dispersion relation in Eq. (7) simplifies to

![\begin{eqnarray} && 1- {k^2c^2 \over \omega^2} + {\omega_{\rm p,p}^2 \over \omega^2} \left\{ {\omega \over k \theta_{{\rm p}, \parallel}}\, Z^0_{\kappa} (g_{\rm p}) - A_{\rm p} \, \left[1+ g_{\rm p} Z^0_{\kappa} (g_{\rm p})\right] \right\} \nonumber \\ \label{e19}&& \qquad \qquad+ {\omega_{\rm p,e}^2 \over \omega^2} \, {\omega \over k \theta_{{\rm e}, \parallel}}\, Z^0_{\kappa} (g_{\rm e}) = 0. \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2011/10/aa16982-11/aa16982-11-eq133.png) (19)For

Maxwellian distributions with the same assumption of anisotropic protons and isotropic

electrons, the dispersion relation in Eq. (19) transforms, in the limit of κ → ∞, to

(19)For

Maxwellian distributions with the same assumption of anisotropic protons and isotropic

electrons, the dispersion relation in Eq. (19) transforms, in the limit of κ → ∞, to ![\begin{eqnarray} &&1- {k^2c^2 \over \omega^2} + {\omega_{\rm p,p}^2 \over \omega^2} \left\{ {\omega \over k v_{T_{{\rm p}, \parallel}}}\, Z(f_{\rm p}) - A_{\rm p} \, \left[1+ f_{\rm p} Z (f_{\rm p})\right] \right\} \nonumber \\ \label{e20} && \qquad \qquad\qquad\qquad + {\omega_{\rm p,e}^2 \over \omega^2} \, {\omega \over k v_{T_{{\rm e}, \parallel}}}\,Z (f_{\rm e}) = 0, \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2011/10/aa16982-11/aa16982-11-eq134.png) (20)where

Z(f) is the standard plasma dispersion function (Fried

& Conte 1961) with the argument

(20)where

Z(f) is the standard plasma dispersion function (Fried

& Conte 1961) with the argument

(21)If protons are still

assumed to be cold (and non-resonant), the argument in Eq. (9) of the plasma dispersion function will be large,

|gp| > 1. Here, we assume that

the electrons are hot so that the argument is

|ge| < 1, and they can resonate

with RH modes. (The non-resonant effects of the electrons are discussed in the other

sections and in Paper I). Limiting to the first order approximation of the modified plasma

dispersion function in Eqs. (12)

and (13), we obtain from Eq. (19)

(21)If protons are still

assumed to be cold (and non-resonant), the argument in Eq. (9) of the plasma dispersion function will be large,

|gp| > 1. Here, we assume that

the electrons are hot so that the argument is

|ge| < 1, and they can resonate

with RH modes. (The non-resonant effects of the electrons are discussed in the other

sections and in Paper I). Limiting to the first order approximation of the modified plasma

dispersion function in Eqs. (12)

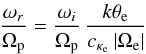

and (13), we obtain from Eq. (19)  (22)where from

Eq. (12)

(22)where from

Eq. (12)  (23)Assuming

ω2 ≪ k2c2

and ω < Ωp the dispersion Eq. (22) reduces further to

(23)Assuming

ω2 ≪ k2c2

and ω < Ωp the dispersion Eq. (22) reduces further to  (24)which admits

unstable solutions of frequency

(24)which admits

unstable solutions of frequency  (25)and

growth rate

(25)and

growth rate  (26)when the same threshold

condition in Eq. (16) for the existence of

the PFHI is fulfilled.

(26)when the same threshold

condition in Eq. (16) for the existence of

the PFHI is fulfilled.

3.3. Hot electrons – anisotropic distribution, Ae ≠ 0

Two distinct cases are found here. First, if the electrons are anisotropic with a finite

but sufficiently small anisotropy to describe an excess of parallel or perpendicular

temperature,

0 < |Ae| < 1,

the instability occurs for the same condition in Eq. (16) and has the same growth rate in Eq. (26), but only the frequency changes to  (27)Second, if the

electron anisotropy is larger,

Te,∥ ≫ Te,⊥

but still in the limit of Ae ≲ 1, or if it is provided by a

surplus of perpendicular temperature,

Te,∥ ≪ Te,⊥

(Ae < 0), the wave solution will be

described (in the same limit of a small

ω < Ωp) by the real frequency

(27)Second, if the

electron anisotropy is larger,

Te,∥ ≫ Te,⊥

but still in the limit of Ae ≲ 1, or if it is provided by a

surplus of perpendicular temperature,

Te,∥ ≪ Te,⊥

(Ae < 0), the wave solution will be

described (in the same limit of a small

ω < Ωp) by the real frequency

(28)and the imaginary

frequency

(28)and the imaginary

frequency  (29)The instability occurs

only for Ae > 0, otherwise the wave is

damped by the resonant electrons with

Te,⊥ ≫ Te,∥

(Ae < 0). As expected in this case,

if the instability occurs, it is exclusively driven by electrons (with a large excess of

the parallel temperature,

Te,⊥ ≪ Te,∥),

and it can change into an EFHI mode if the Ap is small enough

to switch the wave polarization, i.e. the sign of the wave frequency in Eq. (28). Thus, Eq. (29) describes analytically the negative-slope branch of the EFHI

growth rate displayed in Paper I, Fig. 1b: after a maximum at the saturation, the growth

rate decreases and does not vanish completely, but decreases asymptotically to zero.

(29)The instability occurs

only for Ae > 0, otherwise the wave is

damped by the resonant electrons with

Te,⊥ ≫ Te,∥

(Ae < 0). As expected in this case,

if the instability occurs, it is exclusively driven by electrons (with a large excess of

the parallel temperature,

Te,⊥ ≪ Te,∥),

and it can change into an EFHI mode if the Ap is small enough

to switch the wave polarization, i.e. the sign of the wave frequency in Eq. (28). Thus, Eq. (29) describes analytically the negative-slope branch of the EFHI

growth rate displayed in Paper I, Fig. 1b: after a maximum at the saturation, the growth

rate decreases and does not vanish completely, but decreases asymptotically to zero.

The instability of the RH modes can also be enhanced by the resonant protons (i.e. with a contribution from the imaginary residual part of the approximations in Eqs. (12) or (13)) producing ion (proton) cyclotron modes (Xue et al. 1993; Dasso et al. 2003), but this is possible only in small-β plasmas, and is not considered here.

3.4. Hot plasma (large wave numbers)

If both components, electrons and protons, are sufficiently hot, both arguments are small enough, i.e. |ge,p| ≪ 1 (region R3 in Fig. 1), and we use the approximation given in Eq. (12) for the modified plasma dispersion function. Keeping only the principal part in Eq. (12), we found no instability driven by the non-resonant particles. Some possible contribution from the resonant electrons in this case, is irrelevant for the firehose instability. The conclusion is that in this limit, the number of the non-resonant protons is not large enough to produce an instability of the firehose type. For electrons colder than protons, which is not the case in the solar wind plasma, the RH mode is damped (ωi < 0).

4. The exact numerical solutions of Eq. (7)

|

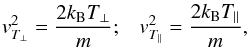

Fig. 4 The exact numerical solutions, the real frequency a) and the growth rate b), c), d) for the PFHI as provided by Eq. (7) for κp = 3 (dotted line), κp = 4 (dashed line), κp = 8 (long-dashed line), and κp → ∞ (solid line), and typical solar wind plasma parameters Te,∥/Tp,∥ = 2, βe,∥ = 8, (βp,∥ = 4), Te,⊥ = Te,∥ ≃ 106 K and different values of the proton anisotropy Tp,⊥/Tp,∥ = 0.25 a), b), 0.6 c), 0.8 d). Electrons are assumed to be isotropic and Maxwellian (κe → ∞). (Wr = ωr/Ωp, Wi = ωi/Ωp, K = kc/ωp,p). |

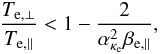

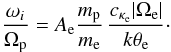

In Figs. 4–6 we plot the exact numerical solutions of Eq. (7), the real frequency Wr = ωr/Ωp, and the growth rate Wi = ωi/Ωp, and examine the influence that the Kappa index value can have on the evolution of the PFHI in different plasma regimes. Values of the plasma parameters including temperature anisotropy, are chosen from the in-situ measurements of the solar wind missions.

The three distinct cases displayed in Fig. 4 correspond to different proton anisotropies Tp,⊥/Tp,∥ = 0.25 (in panels a and b), 0.6 (c), 0.8 (d). The electrons are assumed to be isotropic (Ae = 0), and Maxwellian (κe → ∞). For comparison, the growth rates are calculated for different values of the spectral index, and their evolution depends markedly on the value of the proton anisotropy. At large anisotropies (panel b), the growth rate increases with κp reaching its maximum for Maxwellian (κp → ∞), but this tendency is restrained by decreasing the anisotropy, and for small anisotropies the growth rates show an opposite trend of variation, decreasing with κp index. If the instability suppression for small values of κp was anticipated by the more stringent threshold conditions found in Eq. (16) (and displayed in Fig. 3), the enhancement of the instability in the presence of Kappa populations with small anisotropies was unexpected. This new evolution seems to correspond to different threshold conditions that can eventually be obtained for an argument of the plasma dispersion function close to unity (| g| ~ 1). However, in the observations there is no constraint for such small anisotropies, and they are probably irrelevant. The real (oscillatory) frequency (panel a) does not change significantly with κp index in the range of unstable wave numbers. Comparing to the growth rates of the EFHI in Paper I, the maxima reached by the growth rate of the PFHI are in general lower. This also remains true for larger proton anisotropies, e.g. Tp,∥/Tp,⊥ = 20, similar to that used for electrons in Paper I. However, when assuming both components, electrons and protons, to be anisotropic, the evolution of the PFHI changes significantly.

Thus, an excess of the electron temperature perpendicular to the magnetic field, Te,⊥/Te,∥ > 1, is expected to enhance the RH polarized mode. This indeed happens, as shown in Fig. 5, but only for large wave numbers when the instability turns into the whistler instability, which is driven by electrons and is, in general, inhibited by the Kappa distributions (Lazar et al. 2008b). At small wave numbers, the PFHI is suppressed by the same anisotropy of electrons, and both the growth rate and the unstable wave numbers interval are reduced. In Kappa distributed plasmas, growth rates are further reduced (at small values of the κ index) if the electron anisotropy is sufficiently small (Fig. 5a). However, for a somewhat larger anisotropy, e.g., Te,⊥/Te,∥ = 1.5 (Fig. 5b), the evolution with κ changes again and the instability is enhanced at small values of κ. In this case, the enhancement of the PFHI occurs instead, for common values of the proton temperature anisotropy, e.g., Tp,⊥/Tp,∥ = 0.25, where the instability seems to be very effective in the observations. Moreover, the enhanced growth rates of the PFHI evolve smoothly into the whistler instability, clearly illustrating that these anisotropic distributions of bi-Kappa type tend to be highly unstable for a broadband of electromagnetic excitations.

|

Fig. 5 Growth rates for the PFHI and the whistler instability (WI) as provided by Eq. (7) for Te,∥/Tp,∥ = 2, βe,∥ = 8, (βp,∥ = 4), Te,∥ ≃ 106 K, Tp,⊥/Tp,∥ = 0.25, and electrons with a small anisotropy Te,⊥/Te,∥ = 1.2 a), 1.5 b). (Wi = ωi/Ωp, K = kc/ωp,p). |

In the opposite case, when the electrons are hotter along the magnetic field direction, the EFHI is also expected to grow and compete with the PFHI (see Fig. 6). These instabilities interplay with each other and produce two maxima in the wave spectrum (see Fig. 6, panels b, c, and d)1. The PFHI grows at smaller wave numbers, and because the two peaks lie within a narrow wavenumber interval they can overlap if plasma conditions are favorable to only one of these instabilities. Three situations displayed in Fig. 6 are representative of the case where these growing modes produce two distinct maxima. We keep the electron anisotropy fixed (Te,⊥/Te,∥ = 0.5) and vary the proton anisotropy. At small deviations from isotropy (Tp,⊥/Tp,∥ = 0.8), the EFHI instability is usually much faster than the PFHI (panel c). Large anisotropies enhance the PFHI that becomes competitive (panel b), or even faster than the EFHI (panel d). In Kappa-distributed plasma, the tendency is the same, and the growth rates are diminished and restrained to small wave numbers because, in this case, the EFHI is suppressed much faster for decreasing values of κe,p. Towards the smallest values of κe,p, as illustrated, for instance, for the growth rates corresponding to κe = 2 and κp = 3 in panels b, c, and d, the EFHI is absent and the PFHI is only slightly inhibited.

These two instabilities have magnetic helicity of opposite sign (RH for the PFHI and LH for the EFHI) and this can help us to discriminate between the peaks, or to decide on their nature when they overlap. Changing of the sign of the oscillatory frequency (and the polarization) occurs exactly at the local minimum of the growth rate, when the PFHI mode shifts to the EFHI mode. This is clearly shown in Fig. 3, panels a and b. At small values of κe,p (e.g., κe = 2 and κp = 3), the frequency does not change sign because the PFHI is dominant and the EFHI is suppressed.

|

Fig. 6 The exact numerical solutions, the real frequency a), and the growth rate b), c), d) for the PFHI (small wave-numbers) and the EFHI (large wave-numbers) as provided by Eq. (7) for different indices κe,p, and typical solar wind plasma parameters Te,∥/Tp,∥ = 2, βe,∥ = 4, (βp,∥ = 2), Te,∥ ≃ 106 K and different anisotropies Te,⊥/Te,∥ = 0.5, Tp,⊥/Tp,∥ = 0.8 a), b), 0.4 c), 0.2 d). (Wr = ωr/Ωp, Wi = ωi/Ωp, K = kc/ωp,p). |

5. Conclusions

We have studied the influence of suprathermal populations on the dispersion properties of the PFHI. The excess of parallel kinetic energy (Tp,∥ > Tp,⊥) has been modeled with an anisotropic power law distribution of bi-Kappa-type.

In Sect. 2, we have derived the general dispersion relation of the RH transverse modes in terms of the modified plasma dispersion function for Kappa distributions. In the limits of both large or small arguments, this function admits approximative analytical forms, that allows us to identify the resonant and non-resonant contributions of the plasma particles. These limits have been explicitly described showing that in a Kappa-distributed plasma, the argument of the new plasma dispersion function becomes larger than unity for a large variety of plasma parameters, wave numbers, and frequencies. Thus, the approximation of the modified dispersion function given in Eq. (13) enables a simple analytical description of the unstable solutions.

Different plasma conditions favorable to an analytical description of the PFHI have been identified in Sect. 3. First, we have derived the threshold conditions, which become more stringent in Kappa-distributed plasmas: the PFHI requires a larger anisotropy and a larger plasma-β parameter to grow. To shape suprathermal distribution functions susceptible of producing the unstable fluctuations measured in solar wind, we have to determine values of the κe,p index satisfying the same condition in Eq. (15). Secondly, we have shown that even in the limit of small wave numbers the growth rates are sensitive to the form of the distribution function: growth rates decrease for low values of the κ index. The standard fluid-like model of the firehose instability is, therefore, recovered only in the Maxwellian limit of κ → ∞.

In Sect. 4, we have examined the exact numerical solutions of the PFHI. If the electrons are isotropic their effect is unimportant, but the influence of suprathermal populations depends on how large the proton anisotropy is. Thus, at large anisotropies the instability is enhanced with κp reaching a maximum for a Maxwellian (κp → ∞), but this tendency is restrained by decreasing the anisotropy, and for small anisotropies the growth rates decrease with κp.

The influence of suprathermal populations also depends on the electron anisotropy. If the electrons exhibit an excess of perpendicular temperature (Te,⊥ > Te,∥), the PFHI growth rates are enhanced by the suprathermal populations (at small values of κe,p) leading to a smooth transition into the whistler instability at high growth rates. In the opposite case, when the electrons are hotter along the magnetic field direction (Te,⊥ < Te,∥), both plasma components drive the firehose instability, the PFHI instability at small wave numbers and the EFHI at larger wave numbers. The growth rate dispersion curve exhibits two peaks of maximum, that can be distinct (Fig. 6), or can overlap when the conditions are favorable to only one of these instabilities. The advantage is that these two instabilities have magnetic helicity of opposite sign that can eventually discriminate the origin of the peaks. Within Kappa distributions, the tendency is the same, the growth rates being reduced and restrained to small wave numbers because the EFHI is suppressed much faster with decreasing κe,p.

The new properties of the PFHI presented here are expected to provide closer agreement with

measured data in the solar flares dominated by the suprathermal populations. If we consider

the magnetic fluctuations measured near 1 AU in the solar wind (Bale et al. 2009), the data distribution corresponding to the magnetic

fluctuation power is sharply peaked in a bandwith

kρp ≃ 0.56 ± 0.32, where

ρp = vp,th, ⊥ /Ωp

is the thermal proton gyroradius. Relating to our wave number scaled by the proton inertial

length  (30)and

assuming the solar wind plasma conditions adopted in Fig. 4, e.g., Ap = 3/4 and

βp,∥ = 4, the measured fluctuations

eventually generated by the PFHI must fall into a bandwith K = 0.24−0.88

that seems to be relevant for the branch of increasing (positive slope) growth rates

displayed in Figs. 4–6. We should, however, remember that these magnetic fluctuations are frequently

attributed to the oblique firehose instability that develops in the same conditions

(T∥ > T⊥),

and seems to be faster (Hellinger et al. 2006) than

the parallel firehose. Because a kinetic analytical treatment in two (or three) dimensions

is still a difficult task, here we have limited the study by considering only the parallel

propagation that must, however, retain the new features of this instability in

Kappa-distributed plasmas. Thus, the general trend of the instability thresholds moving to

larger values of β∥ (in Fig. 3) seems to agree with observations in the solar wind.

(30)and

assuming the solar wind plasma conditions adopted in Fig. 4, e.g., Ap = 3/4 and

βp,∥ = 4, the measured fluctuations

eventually generated by the PFHI must fall into a bandwith K = 0.24−0.88

that seems to be relevant for the branch of increasing (positive slope) growth rates

displayed in Figs. 4–6. We should, however, remember that these magnetic fluctuations are frequently

attributed to the oblique firehose instability that develops in the same conditions

(T∥ > T⊥),

and seems to be faster (Hellinger et al. 2006) than

the parallel firehose. Because a kinetic analytical treatment in two (or three) dimensions

is still a difficult task, here we have limited the study by considering only the parallel

propagation that must, however, retain the new features of this instability in

Kappa-distributed plasmas. Thus, the general trend of the instability thresholds moving to

larger values of β∥ (in Fig. 3) seems to agree with observations in the solar wind.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the anonymous referee for his insightful comments and suggestions. The authors acknowledge financial support from the Research Foundation Flanders – FWO Belgium, the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, and by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), grant Schl 201/21-1. These results were obtained in the framework of the projects GOA/2009-009 (K.U. Leuven), G.0729.11 (FWO-Vlaanderen) and C 90205 (ESA Prodex 10). Financial support by the European Commission through the SOLAIRE Network (MTRN-CT-2006-035484) is gratefully acknowledged. The numerical results were obtained on the HPC cluster VIC of the K.U. Leuven.

References

- Bale, S., Kasper, J. C., Howes, G. G., et al. 2009, PRL, 103, 211101 [Google Scholar]

- Bougeret, J.-L., & Pick, M. 2007, in Handbook of Solar-Terrestrial Environment, Part 1, 133 [Google Scholar]

- Cairns, I. H., Robinson, P. A., & Zank, G. P. 2000, Publ. Astron. Soc. Aust., 17, 22 [Google Scholar]

- Chotoo, K., Schwadron, N., Mason, G., et al. 2000, J. Geophys. Res., 105, 23107 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Collier, M. R., Hamilton, D. C., Gloeckler, G., Bochsler, P., & Sheldon, R. B. 1996, Geophys. Res. Lett., 23, 1191 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Decker, D. B., Krimigis, S. M., Roelof, E. C., et al. 2005, Science, 309, 2020 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dröge, W. 2003, ApJ, 389, 1027 [Google Scholar]

- Fisk, L. A., & Gloeckler, G. 2007, Space Sci. Rev., 130, 153 [Google Scholar]

- Dasso, S., Gratton, F. T., & Farrugia, C. J. 2003, JGR, 108, 1149 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Fried, B. D., & Conte, S. D. 1961, The Plasma Dispersion Function (New York: Academic Press) [Google Scholar]

- Gary, S. P. 1993, Theory of Space Plasma Microinstabilities (Cambridge: University Press) [Google Scholar]

- Gary, S. P., Montgomery, M. D., Feldman, W. C., & Forslund, D. W. 1976, JGR, 81, 1241 [Google Scholar]

- Gary, S. P., Li, H., O’Rourke, S., & Winske, D. 1998, JGR, 103, 14567 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gloeckler, G., & Hamilton, D. C. 1987, Phys. Scripta T, 18, 73 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hellinger, P., & Matsumoto, H. 2000, JGR, 105, 10519 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hellinger, P., Travnicek, P., Kasper, J. C., & Lazarus, A. J. 2006, GRL, 33, L09101 [Google Scholar]

- Kasper, J. C., Lazarus, A. J., & Gary, S. P. 2002, GRL, 29, 1839 [Google Scholar]

- Lazar, M., & Poedts, S. 2009, A&A, 494, 311 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Lazar, M., Schlickeiser, R., & Shukla, P. K. 2008a, Phys. Plasmas, 15, 042103 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lazar, M., Schlickeiser, R., Poedts, S., & Tautz, R. C. 2008b, MNRAS, 390, 168 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Marsch, E. 2006, Liv. Rev. Sol. Phys., 3, http://www.livingreviews.org/lrsp-2006-1 [Google Scholar]

- Matteini, L., Landi, S., Hellinger, P., & Velli, M. 2006, JGR, 111, A10101 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Parker, E. N. 1958, Phys. Rev., 109, 1874 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pierrard, V., & Lazar, M. 2010, Sol. Phys., 267, 153 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pierrard, V., Lazar, M., & Schlickeiser, R. 2011, Sol. Phys. [Google Scholar]

- Pilipp, W., & Völk, H. J. 1971, J. Plasma Phys., 6, 1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Quest, K. B., & Shapiro, V. D. 1996, JGR, 101, 24457 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schlickeiser, R., Lazar, M., & Vukcevic, M. 2010, ApJ, 719, 1497 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Stverak, S., Travnicek, P., Maksimovic, M., et al. 2008, JGR, 113, A03103 [Google Scholar]

- Summers, D., & Thorne, R. M. 1991, Phys. Fluids B, 3, 1835 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Vasyliunas, V. M. 1968, JGR, 73, 2839 [Google Scholar]

- Xue, S., Thorne, R. M., & Summers, D. 1993, JGR, 98, 17475 [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, P. H. 1995, Phys. Scripta T, 60, 127 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.-J., & Hau, L. -N. 2003, JGR, 108, 1463 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Spectral domains R1–R4, where the approximations given in Eqs. (12) and (13) of the modified plasma dispersion function (8) can be used. For a dominance of suprathermal populations, indices κa → 1/2, and ακa → 0 increasing (meακeβe,∥/mp)−1/2 and (ακpβp,∥)−1/2 to very large values, and also enlarging the area where the arguments |ga| > 1 are large enough to apply the approximation in Eq. (13) for both species a = e,p, (Wr,i = ωr,i/Ωp, K = kc/ωp,p). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Growth rates of the firehose instability as provided by Eq. (14) for κe = 2, κp = 3 (dotted line), κe,p = 4 (dashed line), κe,p → ∞ (solid line), and plasma parameters: Te,∥/Te,⊥ = Tp,∥/Tp,⊥ = 4, a) Te,∥/Tp,∥ = 3, βe,∥ = 18; and b) Te,∥/Tp,∥ = 2, βe,∥ = 8. For a given wave-number value K = 0.03, the growth rate variation with κe and κp is shown in panel c). (Wi = ωi/Ωp, K = kc/ωp,p). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 Threshold conditions for the EFHI (or the PFHI) as provided by Eq. (16) (or in Eq. (17)) for different

values κ. The instability occurs below the threshold lines for

|

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4 The exact numerical solutions, the real frequency a) and the growth rate b), c), d) for the PFHI as provided by Eq. (7) for κp = 3 (dotted line), κp = 4 (dashed line), κp = 8 (long-dashed line), and κp → ∞ (solid line), and typical solar wind plasma parameters Te,∥/Tp,∥ = 2, βe,∥ = 8, (βp,∥ = 4), Te,⊥ = Te,∥ ≃ 106 K and different values of the proton anisotropy Tp,⊥/Tp,∥ = 0.25 a), b), 0.6 c), 0.8 d). Electrons are assumed to be isotropic and Maxwellian (κe → ∞). (Wr = ωr/Ωp, Wi = ωi/Ωp, K = kc/ωp,p). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5 Growth rates for the PFHI and the whistler instability (WI) as provided by Eq. (7) for Te,∥/Tp,∥ = 2, βe,∥ = 8, (βp,∥ = 4), Te,∥ ≃ 106 K, Tp,⊥/Tp,∥ = 0.25, and electrons with a small anisotropy Te,⊥/Te,∥ = 1.2 a), 1.5 b). (Wi = ωi/Ωp, K = kc/ωp,p). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 6 The exact numerical solutions, the real frequency a), and the growth rate b), c), d) for the PFHI (small wave-numbers) and the EFHI (large wave-numbers) as provided by Eq. (7) for different indices κe,p, and typical solar wind plasma parameters Te,∥/Tp,∥ = 2, βe,∥ = 4, (βp,∥ = 2), Te,∥ ≃ 106 K and different anisotropies Te,⊥/Te,∥ = 0.5, Tp,⊥/Tp,∥ = 0.8 a), b), 0.4 c), 0.2 d). (Wr = ωr/Ωp, Wi = ωi/Ωp, K = kc/ωp,p). |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.