| Issue |

A&A

Volume 521, October 2010

Herschel/HIFI: first science highlights

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | L10 | |

| Number of page(s) | 5 | |

| Section | Letters | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201015077 | |

| Published online | 01 October 2010 | |

Herschel/HIFI: first science highlights

LETTER TO THE EDITOR

Herschel/HIFI observations of interstellar OH+ and H2O+ towards W49N![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png) :

a probe of diffuse clouds with a small molecular fraction

:

a probe of diffuse clouds with a small molecular fraction

D. A. Neufeld1, J. R. Goicoechea2, P. Sonnentrucker1, J. H. Black3, J. Pearson4, S. Yu4, T. G. Phillips5, D. C. Lis5, M. De Luca6, E. Herbst7, P. Rimmer7, M. Gerin6, T. A. Bell5, F. Boulanger8, J. Cernicharo2, A. Coutens9, E. Dartois8, M. Kazmierczak10, P. Encrenaz6, E. Falgarone6, T. R. Geballe11, T. Giesen12, B. Godard6, P. F. Goldsmith4, C. Gry13, H. Gupta4, P. Hennebelle6, P. Hily-Blant14, C. Joblin9, R. Ko![]() os15, J. Kre

os15, J. Kre![]() owski10, J. Martín-Pintado2, K. M. Menten16, R. Monje5, B. Mookerjea17, M. Perault6, C. Persson3, R. Plume18, M. Salez6, S. Schlemmer12, M. Schmidt19, J. Stutzki12, D. Teyssier20, C. Vastel9, A. Cros9, K. Klein21, A. Lorenzani22, S. Philipp23, L. A. Samoska4, R. Shipman24,

A. G. G. M. Tielens25 - R. Szczerba19 - J. Zmuidzinas5

owski10, J. Martín-Pintado2, K. M. Menten16, R. Monje5, B. Mookerjea17, M. Perault6, C. Persson3, R. Plume18, M. Salez6, S. Schlemmer12, M. Schmidt19, J. Stutzki12, D. Teyssier20, C. Vastel9, A. Cros9, K. Klein21, A. Lorenzani22, S. Philipp23, L. A. Samoska4, R. Shipman24,

A. G. G. M. Tielens25 - R. Szczerba19 - J. Zmuidzinas5

1 - The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA

2 - Centro de Astrobiología, CSIC-INTA, 28850, Madrid, Spain

3 - Chalmers University of Technology, Göteborg, Sweden

4 - JPL, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, USA

5 - California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA

6 - LERMA, CNRS, Observatoire de Paris and ENS, France

7 - Depts. of Physics, Astronomy & Chemistry, Ohio State Univ., USA

8 - Institut d'Astrophysique Spatiale (IAS), Orsay, France

9 - Université Toulouse; UPS; CESR; and CNRS; UMR5187,

9 avenue du colonel Roche, 31028 Toulouse Cedex 4, France

10 - Nicolaus Copernicus University, Torun, Poland

11 - Gemini telescope, Hilo, Hawaii, USA

12 - I. Physikalisches Institut, University of Cologne, Germany

13 - LAM, OAMP, Université Aix-Marseille & CNRS, Marseille, France

14 - Laboratoire d'Astrophysique de Grenoble, France

15 - Institute of Physical Chemistry, PAS, Warsaw, Poland

16 - MPI für Radioastronomie, Bonn, Germany

17 - Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Homi Bhabha Road, Mumbai 400005, India

18 - Dept. of Physics & Astronomy, University of Calgary, Canada

19 - Nicolaus Copernicus Astronomical Center, Poland

20 - European Space Astronomy Centre, ESA, Madrid, Spain

21 - Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Waterloo, Canada

22 - Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri - INAF, Florence, Italy

23 - Deutsches Zentrum für Luft - und Raumfahrt e. V., Raumfahrt-Agentur,

Bonn, Germany

24 - SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research, The Netherlands

25 - Sterrewacht Leiden, The Netherlands

Received 28 May 2010 / Accepted 28 June 2010

Abstract

We report the detection of absorption by interstellar hydroxyl

cations and water cations, along the sight-line to the bright continuum

source W49N. We have used Herschel's HIFI instrument, in dual beam switch mode, to observe the 972 GHz N=1-0 transition of ![]() and the 1115 GHz

111-000 transition of ortho-

and the 1115 GHz

111-000 transition of ortho-

![]() .

The resultant spectra show absorption by ortho-

.

The resultant spectra show absorption by ortho-

![]() ,

and strong absorption by OH+, in foreground material at velocities in the range 0 to 70

,

and strong absorption by OH+, in foreground material at velocities in the range 0 to 70

![]() with respect to the local standard of rest. The inferred

with respect to the local standard of rest. The inferred

![]() abundance ratio ranges from

abundance ratio ranges from ![]() 3 to

3 to ![]() 15, implying that the observed OH+ arises in clouds of small molecular fraction, in the

15, implying that the observed OH+ arises in clouds of small molecular fraction, in the ![]() range.

This conclusion is confirmed by the distribution of OH+ and H2O+

in Doppler velocity space, which is similar to that of atomic hydrogen,

as observed by means of 21 cm absorption measurements, and

dissimilar from that typical of other molecular tracers. The observed

range.

This conclusion is confirmed by the distribution of OH+ and H2O+

in Doppler velocity space, which is similar to that of atomic hydrogen,

as observed by means of 21 cm absorption measurements, and

dissimilar from that typical of other molecular tracers. The observed

![]() abundance ratio of a few

abundance ratio of a few

![]() suggests a cosmic ray ionization rate for atomic hydrogen of

suggests a cosmic ray ionization rate for atomic hydrogen of

![]() ,

in good agreement with estimates inferred previously for

diffuse clouds in the Galactic disk from observations of interstellar H3+ and other species.

,

in good agreement with estimates inferred previously for

diffuse clouds in the Galactic disk from observations of interstellar H3+ and other species.

Key words: ISM: molecules - submillimeter: ISM - astrochemistry - molecular processes

1 Introduction

After hydrogen and helium, oxygen is the most abundant heavy element in the Universe, accounting for more than ![]() of the mass of baryons in the Galaxy. Of the

of the mass of baryons in the Galaxy. Of the ![]() 150

distinct molecules detected in the interstellar gas to date, more than

one-quarter contain oxygen, including many of the most widely-observed

species such as CO, OH, H2O, CH3OH, H2CO, SiO, and SO2.

Not surprisingly, the chemical processes leading to the incorporation

of interstellar oxygen atoms into oxygen-bearing molecules have been

the subject of numerous theoretical investigations. These studies have

identified three types of process that can be important in various

interstellar environments: (1) in warm regions, where the gas

temperature exceeds

150

distinct molecules detected in the interstellar gas to date, more than

one-quarter contain oxygen, including many of the most widely-observed

species such as CO, OH, H2O, CH3OH, H2CO, SiO, and SO2.

Not surprisingly, the chemical processes leading to the incorporation

of interstellar oxygen atoms into oxygen-bearing molecules have been

the subject of numerous theoretical investigations. These studies have

identified three types of process that can be important in various

interstellar environments: (1) in warm regions, where the gas

temperature exceeds ![]() 300 K

as a result of heating by shocks, by turbulent dissipation, or by

infrared or ultraviolet radiation, the oxygen chemistry can be

initiated by the endothermic reaction of atomic oxygen with H2;

(2) on grain surfaces, the formation of oxygen-bearing molecules can

occur following the adsorption of atomic oxygen; the resultant

molecules can then be released into the gas-phase by photodesorption or

evaporation if the grains are exposed to ultraviolet radiation or

heated sufficiently; and (3) in gas clouds that are irradiated by

cosmic rays or X-rays, the oxygen chemistry is controlled by a series

of ion-neutral reactions, and is initiated by the formation of the

hydroxyl cation OH+, which can react with molecular hydrogen to form H2O+ and then H3O+.

300 K

as a result of heating by shocks, by turbulent dissipation, or by

infrared or ultraviolet radiation, the oxygen chemistry can be

initiated by the endothermic reaction of atomic oxygen with H2;

(2) on grain surfaces, the formation of oxygen-bearing molecules can

occur following the adsorption of atomic oxygen; the resultant

molecules can then be released into the gas-phase by photodesorption or

evaporation if the grains are exposed to ultraviolet radiation or

heated sufficiently; and (3) in gas clouds that are irradiated by

cosmic rays or X-rays, the oxygen chemistry is controlled by a series

of ion-neutral reactions, and is initiated by the formation of the

hydroxyl cation OH+, which can react with molecular hydrogen to form H2O+ and then H3O+.

This third type of process, ion-neutral chemistry, is believed to

dominate the formation of oxygen-bearing molecules within the cold

quiescent interstellar medium (ISM). However, the detection of two key

intermediaries in this reaction sequence, the OH+ and H2O+

molecular ions, has proven elusive. Like other light hydrides with

small moments of inertia, these molecules have rotational transitions

at high frequencies that are difficult or impossible to observe from

ground-based observatories. Until very recently, neither OH+ nor H2O+ had been detected in the interstellar gas (although optical transitions of H2O+ have long been detected in comets, e.g. Wehinger et al. 1974). In the last three months, however, the observational

picture has changed rapidly. With the availability of the HIFI instrument (de Graauw et al. 2010) on Herschel (Pilbratt et al. 2010), detections of H2O+ have been reported in absorption toward DR21, Sgr B2 (M), NGC6334I (Ossenkopf et al. 2010) and G10.6-0.4 (Gerin et al. 2010).

In G10.6-0.4, which was targeted for absorption line studies as part of

the PRISMAS (``PRobing InterStellar Molecules with Absorption line

Studies'') key program, absorption by

![]() and strong absorption by OH+ were also reported. In addition, Herschel/SPIRE observations of Mrk 231 have revealed luminous OH+ emission (van der Werf et al. 2010),

while recent ground-based observations have led to detection of interstellar OH+ in the near-UV spectral region (Kre

and strong absorption by OH+ were also reported. In addition, Herschel/SPIRE observations of Mrk 231 have revealed luminous OH+ emission (van der Werf et al. 2010),

while recent ground-based observations have led to detection of interstellar OH+ in the near-UV spectral region (Kre![]() owski et al. 2010,

who used the ESO Paranal observatory to detect a weak absorption line

at 358.3769 nm) and at submillimeter wavelengths (Wyrowski

et al. 2010, who used the APEX observatory to detect OH+ in absorption toward Sgr B2).

owski et al. 2010,

who used the ESO Paranal observatory to detect a weak absorption line

at 358.3769 nm) and at submillimeter wavelengths (Wyrowski

et al. 2010, who used the APEX observatory to detect OH+ in absorption toward Sgr B2).

In this Letter, we report Herschel/HIFI observations of OH+ and ![]() O+

towards a second strong continuum source that we have targeted in the PRISMAS program, W49N.

This luminous region of star formation, lying within the W49A complex, is located at a distance

of 11.4 kpc, a value reliably determined by means of maser proper motion studies (Gwinn et al. 1992). The sight-line to W49N is known to intersect a large collection of foreground gas clouds,

with velocities relative to the local standard of rest (LSR) ranging from

O+

towards a second strong continuum source that we have targeted in the PRISMAS program, W49N.

This luminous region of star formation, lying within the W49A complex, is located at a distance

of 11.4 kpc, a value reliably determined by means of maser proper motion studies (Gwinn et al. 1992). The sight-line to W49N is known to intersect a large collection of foreground gas clouds,

with velocities relative to the local standard of rest (LSR) ranging from ![]() 0 to

0 to

![]()

![]() ;

these have been widely detected by means of absorption line spectroscopy of multiple species, including H (Brogan & Troland 2001; Fish et al. 2003), H2O, OH (Plume et al. 2004), O (Vastel et al. 2000), HCO+, HCN, HNC, and CN (Godard et al. 2010).

;

these have been widely detected by means of absorption line spectroscopy of multiple species, including H (Brogan & Troland 2001; Fish et al. 2003), H2O, OH (Plume et al. 2004), O (Vastel et al. 2000), HCO+, HCN, HNC, and CN (Godard et al. 2010).

2 Observations and data reduction

In the observations reported here, we targeted two transitions - the 972 GHz N=1-0 transition of OH+, and the 1115 GHz

111-000 transition of ortho-

![]() - in the lower sidebands of Bands 4a and 5a of the HIFI

receiver. To help determine whether any observed feature did indeed lie

in the expected sideband, three observations were carried out with

slightly different settings of the local oscillator (LO) frequency.

These observations, with on-source integration times of 59 s (OH+ line) and 89 s (

- in the lower sidebands of Bands 4a and 5a of the HIFI

receiver. To help determine whether any observed feature did indeed lie

in the expected sideband, three observations were carried out with

slightly different settings of the local oscillator (LO) frequency.

These observations, with on-source integration times of 59 s (OH+ line) and 89 s (

![]() line) each, were carried out on 2010 April 18, using the dual beam

switch (DBS) mode and the wide band spectrometer (WBS). The WBS has a

spectral resolution of 1.1 MHz, corresponding to a velocity

resolutions of

line) each, were carried out on 2010 April 18, using the dual beam

switch (DBS) mode and the wide band spectrometer (WBS). The WBS has a

spectral resolution of 1.1 MHz, corresponding to a velocity

resolutions of

![]() to

to

![]() at the frequencies of the OH+ and

at the frequencies of the OH+ and

![]() transitions. The telescope beam was centered at

transitions. The telescope beam was centered at

![]() ,

,

![]() 06

06![]() 12.0

12.0

![]() (J2000). The reference positions for these observations were located 3

(J2000). The reference positions for these observations were located 3![]() on either side of the source along an East-West axis.

on either side of the source along an East-West axis.

The spectroscopic parameters for the observed transitions have been summarized by Ossenkopf et al. (2010) and Gerin et al. (2010). Both the OH+ and H2O+

transitions exhibit hyperfine structure associated with the interaction

of the nuclear spin magnetic moment with that resulting from electronic

spin. The OH+ N=1-0 transition has three hyperfine components, at velocities of

-35.6, -0.5, and 0 km s-1

relative to the central hyperfine component, and with absorption line

strengths in the ratio 1:5:9 if the lower levels are populated in

proportion to their statistical weights. For H2O+, there are five hyperfine components; the corresponding velocity shifts are -25.5, -15.9, 0, 4.8 and 14.4 km s-1 and the ratio of line strengths is 1:8:27:8:10. Frequencies accurate to 1.5 MHz or better are available for the OH+ transition, but those for the

![]() transition have been the subject of some controversy (Ossenkopf et al. 2010). As discussed in Appendix A, we favor a frequency close to that given by Mürtz et al. (1998) for the strongest hyperfine component,

transition have been the subject of some controversy (Ossenkopf et al. 2010). As discussed in Appendix A, we favor a frequency close to that given by Mürtz et al. (1998) for the strongest hyperfine component,

![]() GHz.

GHz.

The data were processed using the standard HIFI pipeline to Level 2, providing fully calibrated spectra of the source. The Level 2 data were analysed further using the Herschel interactive processing environment (HIPE, Ott 2010), version 2.4, along with ancillary IDL routines that we have developed. For each of the target lines, the signals measured in the two orthogonal polarizations were in excellent agreement, as were spectra obtained at the three LO settings when assigned to the expected sideband. We combined the data from the three observations, and from both polarizations, to obtain an average spectrum.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,height=5.5cm,clip]{15077fg1.eps}\vspace{-3mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa15077-10/Timg25.png)

|

Figure 1:

Spectra of H2O+

111-000 (green) and OH+ N=1-0 (blue)

transitions obtained toward W49N. The velocity scale applies to the

strongest hyperfine component, with assumed frequencies of

971 803.8 MHz for OH+ and 1 115 204 MHz for

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

3 Results

Figure 1 shows the WBS spectra for the OH+ N=1-0 (blue) and ortho-H2O+ 111-000 (green) transitions, with the frequency scale expressed as Doppler velocities relative to the local standard of rest (LSR) for the strongest hyperfine component. The double sideband continuum antenna temperatures areIn fitting the observed spectra, we have assumed the absorption to

arise in a set of clouds with Gaussian opacity profiles. Moreover,

given the close chemical relationship between the two cations that we

have detected, we assumed that the OH+ and ortho-

![]() arise within the same set of clouds. Each cloud is therefore

characterized by a set of four quantities that we treat as adjustable

parameters: the centroid velocity,

arise within the same set of clouds. Each cloud is therefore

characterized by a set of four quantities that we treat as adjustable

parameters: the centroid velocity,

![]() ,

the velocity width,

,

the velocity width, ![]() (defined here as the full-width-at-half-maximum), and the OH+ and

(defined here as the full-width-at-half-maximum), and the OH+ and

![]() column densities. Here, we neglected any contribution from para-H2O+ to the total

column densities. Here, we neglected any contribution from para-H2O+ to the total

![]() column density; the

101-101 transition of para-

column density; the

101-101 transition of para-

![]() was searched for but not detected toward W49, and observations of para-

was searched for but not detected toward W49, and observations of para-

![]() toward Sgr B2 (M), reported recently by Schilke et al. (2010), imply that the ortho-to-para ratio is typically large (

toward Sgr B2 (M), reported recently by Schilke et al. (2010), imply that the ortho-to-para ratio is typically large (![]() 5) in diffuse clouds along that sight-line.

5) in diffuse clouds along that sight-line.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{15077fg2.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa15077-10/Timg31.png)

|

Figure 2:

Fit to the OH+ (top panel) and H2O+ (middle panel)

absorption spectra observed toward W49N. The black curve shows the

data, and the red curve is the fit obtained for the cloud parameters

listed in Table 1. The corresponding column densities per unit velocity

interval are shown in the bottom panel, for |

| Open with DEXTER | |

We also assumed that the population of OH+ and ortho-

![]() in excited rotational states is negligible, and that the individual

hyperfine states within the ground rotational state are populated in

proportion to their statistical weights. Our line fitting procedure

included two additional free parameters: (1) the SBR for the OH+ observations; and (2) the rest frequency of the H2O+

transition (see Appendix A). We adopted the minimum number of

absorption components needed to provide a reasonable fit to the data -

six - and obtained initial estimates of the cloud velocities and FWHM's

by eye. These estimates were then refined by using the IDL mpfitfun

routine, which implements the Levenberg-Marquardt method for obtaining

a least-squares fit.

in excited rotational states is negligible, and that the individual

hyperfine states within the ground rotational state are populated in

proportion to their statistical weights. Our line fitting procedure

included two additional free parameters: (1) the SBR for the OH+ observations; and (2) the rest frequency of the H2O+

transition (see Appendix A). We adopted the minimum number of

absorption components needed to provide a reasonable fit to the data -

six - and obtained initial estimates of the cloud velocities and FWHM's

by eye. These estimates were then refined by using the IDL mpfitfun

routine, which implements the Levenberg-Marquardt method for obtaining

a least-squares fit.

Figure 2 shows the best fit that could be obtained to the OH+ (top panel) and H2O+ (middle panel) spectra for a model with six foreground clouds. The reduced ![]() for this fit was 1.83, suggesting that the ``minimal'' absorption model

does not entirely account for the data. The best-fit cloud parameters

are given in Table 1. The best-fit line widths are moderately broad,

particularly for the 62.5 km s-1 feature, and might - in reality - represent the superposition of multiple narrower features. The SBR derived for the OH+ spectrum was 0.884 (signal sideband gain divided by image sideband gain), and the frequency derived for the strongest H2O+

hyperfine component was 1 115 209 MHz (see

Appendix A). In the bottom panel of Fig. 2, we present the OH+ (blue) and H2O+ column densities (green) obtained per unit velocity width in our best fit model. The cloud parameters in Table 1 appear to be relatively robust. Although the OH+ absorption is completely thick

for LSR velocities in the ranges 30-42 and 60-70 km s-1

(as determined for the strongest hyperfine component), the existence of

a weaker hyperfine component at an offset of -35 km s-1 means that arbitrarily large column densities of OH+ can only be accommodated within a narrow range of LSR velocities: 65-70 km s-1.

for this fit was 1.83, suggesting that the ``minimal'' absorption model

does not entirely account for the data. The best-fit cloud parameters

are given in Table 1. The best-fit line widths are moderately broad,

particularly for the 62.5 km s-1 feature, and might - in reality - represent the superposition of multiple narrower features. The SBR derived for the OH+ spectrum was 0.884 (signal sideband gain divided by image sideband gain), and the frequency derived for the strongest H2O+

hyperfine component was 1 115 209 MHz (see

Appendix A). In the bottom panel of Fig. 2, we present the OH+ (blue) and H2O+ column densities (green) obtained per unit velocity width in our best fit model. The cloud parameters in Table 1 appear to be relatively robust. Although the OH+ absorption is completely thick

for LSR velocities in the ranges 30-42 and 60-70 km s-1

(as determined for the strongest hyperfine component), the existence of

a weaker hyperfine component at an offset of -35 km s-1 means that arbitrarily large column densities of OH+ can only be accommodated within a narrow range of LSR velocities: 65-70 km s-1.

Table 1: W49N absorption line components.

4 Discussion

For diffuse molecular clouds, theoretical models (e.g. van Dishoeck & Black 1986)

have elucidated the ion-neutral chemistry that leads to the production

of oxygen-bearing molecules. The reaction network is initiated by the

cosmic-ray ionization of atomic hydrogen to form H+, which undergoes charge transfer with atomic oxygen in a reaction that is slightly endothermic by the equivalent of ![]() 230 K. The resultant O+ ions can then undergo a series of exothermic hydrogen atom abstraction reactions, leading to the OH+, H2O+ and H3O+. The latter is removed by dissociative recombination, which can be the dominant source of the neutral molecules OH and H2O. If the ratio of electron density to H2 is sufficiently large, as it is in diffuse clouds of small molecular fraction, the pipeline leading from O+ to OH+ to H2O+ to

230 K. The resultant O+ ions can then undergo a series of exothermic hydrogen atom abstraction reactions, leading to the OH+, H2O+ and H3O+. The latter is removed by dissociative recombination, which can be the dominant source of the neutral molecules OH and H2O. If the ratio of electron density to H2 is sufficiently large, as it is in diffuse clouds of small molecular fraction, the pipeline leading from O+ to OH+ to H2O+ to

![]() can be a leaky one, with the flow of ionization reduced at each step by the dissociative recombination of OH+ and

can be a leaky one, with the flow of ionization reduced at each step by the dissociative recombination of OH+ and

![]() .

In dense molecular clouds, by contrast, the atomic hydrogen abundance and temperature are both too small for O+ production to be efficient, and the dominant source of OH+ is the reaction of H3+ with O. Once again, the chemistry is driven by cosmic ray ionization - the original source of H3+ - but now the conversion of OH+ to

.

In dense molecular clouds, by contrast, the atomic hydrogen abundance and temperature are both too small for O+ production to be efficient, and the dominant source of OH+ is the reaction of H3+ with O. Once again, the chemistry is driven by cosmic ray ionization - the original source of H3+ - but now the conversion of OH+ to

![]() to

to

![]() proceeds with almost 100

proceeds with almost 100![]() efficiency.

efficiency.

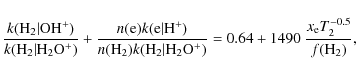

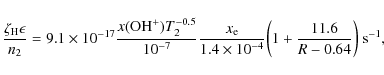

As discussed by Gerin et al. (2010), the OH+/

![]() abundance ratio provides a critical

probe of the molecular fraction. Regardless of the production mechanism for OH+,

the OH+/

abundance ratio provides a critical

probe of the molecular fraction. Regardless of the production mechanism for OH+,

the OH+/

![]() ratio is given by

ratio is given by

|

(1) |

where

This simple expression, which accounts exactly for all results that we

have obtained to date with the Meudon PDR model (Le Petit et al. 2006; Goicoechea & Le Bourlot 2007), assumes only that H2O+ is produced by reaction of OH+ with H2, is destroyed by dissociative recombination or reaction with H2, and has reached a steady-state abundance. For the six absorption components in which the OH+ and

![]() column densities are well determined, the resultant abundance ratios range from

column densities are well determined, the resultant abundance ratios range from ![]() 3-15, requiring

3-15, requiring

![]() in the range

in the range ![]() 0.02-0.08.

Since the largest plausible fractional ionization in a neutral gas cloud is

0.02-0.08.

Since the largest plausible fractional ionization in a neutral gas cloud is ![]()

![]() ,

corresponding to the complete ionization of carbon, the OH+ ions must reside primarily within clouds of low molecular fraction. The derived molecular fraction is given in Table 2 for each absorption component.

,

corresponding to the complete ionization of carbon, the OH+ ions must reside primarily within clouds of low molecular fraction. The derived molecular fraction is given in Table 2 for each absorption component.

Our conclusion that OH+ resides primarily in clouds that are predominantly atomic - a result

obtained previously by Gerin et al. (2010)

for the sight-line to G10.6-0.4 - is strongly corroborated by the

observed distribution of absorbing material in velocity space

(Fig. 2, bottom panel). The distribution of H2O+ (in green) and OH+ (blue) is similar to that of atomic hydrogen, as determined by 21 cm observations reported by Fish et al. (2003, black), (although atomic hydrogen is evidently present without accompanying OH+ and H2O+ at LSR velocities in the range -10 to 0 km s-1). The distribution of OH+ and H2O+ is strikingly dissimilar from that of para-H2O (red), which has been observed by HIFI and reported by Sonnentrucker et al. (2010).

Whereas water and other molecules detected previously toward W49N

appear to reside primarily in clouds of relatively narrow velocity

width, ![]() ,

,

![]() and H are more broadly distributed in velocity space.

and H are more broadly distributed in velocity space.

Table 2:

![]() and

and

![]() abundances.

abundances.

In Table 2, we present the abundances of ![]() and

and

![]() relative to atomic hydrogen in two velocity ranges considered previously by Godard et al. (2010). Here we adopt the estimates of

relative to atomic hydrogen in two velocity ranges considered previously by Godard et al. (2010). Here we adopt the estimates of

![]() derived by Godard et al. from the HI 21 cm spectra of Fish et al. (2003) for an assumed spin temperature,

derived by Godard et al. from the HI 21 cm spectra of Fish et al. (2003) for an assumed spin temperature, ![]() ,

of 100 K. As discussed by Gerin et al. (2010), the OH+ to atomic hydrogen ratio probes the cosmic ray ionization rate,

,

of 100 K. As discussed by Gerin et al. (2010), the OH+ to atomic hydrogen ratio probes the cosmic ray ionization rate,

![]() ,

defined here as the total rate of ionization per hydrogen atom. The presence of OH+ in clouds of small molecular fraction was anticipated by Liszt (2007), in his investigation of the time-scale for H2 formation in diffuse atomic clouds.

In his models, the hydrogen molecular fraction approaches steady state only after 107 yr. His

predicted formation rate of OH+ at

,

defined here as the total rate of ionization per hydrogen atom. The presence of OH+ in clouds of small molecular fraction was anticipated by Liszt (2007), in his investigation of the time-scale for H2 formation in diffuse atomic clouds.

In his models, the hydrogen molecular fraction approaches steady state only after 107 yr. His

predicted formation rate of OH+ at

![]() s-1 is sufficient to attain

s-1 is sufficient to attain

![]() in clouds at

in clouds at

![]() cm-3 when the cloud age is in the range 2 to 10 million yr.

cm-3 when the cloud age is in the range 2 to 10 million yr.

Defining ![]() as the ratio of the OH+ production rate to the cosmic ray ionization rate,

assuming that OH+ is destroyed by reaction with H2 and dissociative recombination at a rate

equal to its formation rate, and using Eq. (1) to relate

as the ratio of the OH+ production rate to the cosmic ray ionization rate,

assuming that OH+ is destroyed by reaction with H2 and dissociative recombination at a rate

equal to its formation rate, and using Eq. (1) to relate

![]() to the observed

to the observed

![]() ratio, we find that

ratio, we find that

|

(2) |

where

Based upon parameter studies performed with the Meudon PDR model, to be

described in detail in a future publication, we find that values of ![]() close to unity can be achieved under a wide range of conditions typical

of diffuse molecular clouds. We have computed the structure of diffuse

molecular clouds for a set of models with gas-phase carbon and oxygen

abundances of

close to unity can be achieved under a wide range of conditions typical

of diffuse molecular clouds. We have computed the structure of diffuse

molecular clouds for a set of models with gas-phase carbon and oxygen

abundances of

![]() and

and

![]() respectively with respect to H nuclei,

cosmic ray ionization rates

respectively with respect to H nuclei,

cosmic ray ionization rates

![]() of 10-17, 10-16, or

of 10-17, 10-16, or

![]() ,

density

,

density ![]() of 102 or

of 102 or

![]() ,

and UV field

,

and UV field

![]() of 1, 10, or 100

(normalized relative to the mean interstellar value). Under most of the conditions that we considered,

of 1, 10, or 100

(normalized relative to the mean interstellar value). Under most of the conditions that we considered, ![]() lies in the range 0.5-1.0 whenever R lies in the observed range of 3-15, the only exceptions being cases with (1)

lies in the range 0.5-1.0 whenever R lies in the observed range of 3-15, the only exceptions being cases with (1)

![]() and

and

![]() ,

for which

,

for which ![]() can reach values as large as 3; and (2)

can reach values as large as 3; and (2)

![]() and

and

![]() ,

for which

,

for which ![]() lies in the range

0.02 - 0.1. In the first of these exceptional cases, the temperature reaches several hundred Kelvin and the production of OH+ is enhanced by reaction of O with H2 to form OH, followed by photoionization of OH to produce OH+; in the second case, the temperature is too low to permit efficient charge exchange between O and H+.

lies in the range

0.02 - 0.1. In the first of these exceptional cases, the temperature reaches several hundred Kelvin and the production of OH+ is enhanced by reaction of O with H2 to form OH, followed by photoionization of OH to produce OH+; in the second case, the temperature is too low to permit efficient charge exchange between O and H+.

Given the temperature, 100 K, and density,

![]() ,

typical of diffuse clouds with a small molecular fraction, our results suggest that the OH+ and

,

typical of diffuse clouds with a small molecular fraction, our results suggest that the OH+ and

![]() abundances observed toward W49 imply a cosmic ray ionization rate

abundances observed toward W49 imply a cosmic ray ionization rate

![]() for atomic hydrogen. This is the total rate of ionization per hydrogen

atom, including secondary ionizations. The range given here reflects

uncertainties in

for atomic hydrogen. This is the total rate of ionization per hydrogen

atom, including secondary ionizations. The range given here reflects

uncertainties in ![]() ,

assumed to lie between 0.5 and 1, and variations in R from one component to another; for temperatures and densities different from those assumed above, the derived value of

,

assumed to lie between 0.5 and 1, and variations in R from one component to another; for temperatures and densities different from those assumed above, the derived value of

![]() would scale as

would scale as

![]() .

This estimate is in good agreement with values for the primary ionization rate per H nucleon obtained by Indriolo et al. (2007) from an analysis of H3+ abundances observed along many sight-lines intersecting diffuse clouds in the Galactic disk; these were in the range

.

This estimate is in good agreement with values for the primary ionization rate per H nucleon obtained by Indriolo et al. (2007) from an analysis of H3+ abundances observed along many sight-lines intersecting diffuse clouds in the Galactic disk; these were in the range

![]() whenever H3+ was detected (although smaller values were allowed but not required in cases where H3+ was not detected). A similar estimate (

whenever H3+ was detected (although smaller values were allowed but not required in cases where H3+ was not detected). A similar estimate (

![]() )

was inferred by Le Petit et al. (2004) from observations of H3+ and other species toward

)

was inferred by Le Petit et al. (2004) from observations of H3+ and other species toward ![]() Persei.

Persei.

HIFI has been designed and built by a consortium of institutes and university departments from across Europe, Canada and the United States under the leadership of SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research, Groningen, The Netherlands and with major contributions from Germany, France and the US. Consortium members are: Canada: CSA, U. Waterloo; France: CESR, LAB, LERMA, IRAM; Germany: KOSMA, MPIfR, MPS; Ireland, NUI Maynooth; Italy: ASI, IFSI-INAF, Osservatorio Astrofisico di Arcetri-INAF; Netherlands: SRON, TUD; Poland: CAMK, CBK; Spain: Observatorio Astronómico Nacional (IGN), Centro de Astrobiologá (CSIC-INTA). Sweden: Chalmers University of Technology - MC2, RSS & GARD;Onsala Space Observatory; Swedish National Space Board, Stockholm University - Stockholm Observatory;Switzerland: ETH Zurich, FHNW; USA: Caltech, JPL, NHSC.

This research was performed, in part, through a JPL contract funded by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. J.R.G. was supported by a Ramón y Cajal contract and by the MICINN/AYA2009-07304 grant. R.Sz. and M.Sch. acknowledge support from grant No. 203 393334 from Polish MNiSW.

Appendix A: H2O+ spectroscopy

The rest frequencies for transitions of

![]() have been the subject of some controversy

(Ossenkopf et al. 2010). The frequency given by Mürtz et al. (1998) for the strongest hyperfine component is

have been the subject of some controversy

(Ossenkopf et al. 2010). The frequency given by Mürtz et al. (1998) for the strongest hyperfine component is

![]() GHz. This value, which is based upon laser magnetic resonance (LMR) experiments, is

GHz. This value, which is based upon laser magnetic resonance (LMR) experiments, is ![]() 28 MHz higher than that predicted by Ossenkopf et al. (2010) from an analysis

of earlier LMR data (Strahan et al. 1986),

and 42 MHz higher than the ``astronomically-determined'' rest

frequency presented by Ossenkopf et al. We have investigated how

well the OH+ and H2O+ spectra obtained toward W49N can be reconciled for various assumed values of the

28 MHz higher than that predicted by Ossenkopf et al. (2010) from an analysis

of earlier LMR data (Strahan et al. 1986),

and 42 MHz higher than the ``astronomically-determined'' rest

frequency presented by Ossenkopf et al. We have investigated how

well the OH+ and H2O+ spectra obtained toward W49N can be reconciled for various assumed values of the

![]() transition frequency. We allowed the latter to vary, in performing the

spectral fitting procedure described in Sect. 3 above, but without

changing the assumed spacing of the hyperfine components. Our best fit

frequency for the strongest H2O+ hyperfine component was 1115.209 GHz, a value lying close to that given by Mürtz et al. (1998). This result would be in error if the OH+ molecules have systematic velocity shift relative to H2O+ within a given cloud. Also, insofar as the frequency scale is tied to the assumed OH+ rest frequency, the fractional error in the derived H2O+ frequency can be no smaller than that for the OH+ rest frequency. Thus, our ``astrophysical determination'' of the H2O+ rest frequency is entirely consistent with the laboratory value reported by Mürtz et al. (1998). However, it is apparently inconsistent with the significantly smaller values given by Ossenkopf et al. (2010). In Fig. A.1, we show the reduced

transition frequency. We allowed the latter to vary, in performing the

spectral fitting procedure described in Sect. 3 above, but without

changing the assumed spacing of the hyperfine components. Our best fit

frequency for the strongest H2O+ hyperfine component was 1115.209 GHz, a value lying close to that given by Mürtz et al. (1998). This result would be in error if the OH+ molecules have systematic velocity shift relative to H2O+ within a given cloud. Also, insofar as the frequency scale is tied to the assumed OH+ rest frequency, the fractional error in the derived H2O+ frequency can be no smaller than that for the OH+ rest frequency. Thus, our ``astrophysical determination'' of the H2O+ rest frequency is entirely consistent with the laboratory value reported by Mürtz et al. (1998). However, it is apparently inconsistent with the significantly smaller values given by Ossenkopf et al. (2010). In Fig. A.1, we show the reduced ![]() for the best fit that can be obtained for a given assumed H2O+ rest frequency, as a function of that frequency. The best fit shows a minimum close to the Mürtz et al. (1998) rest frequency and is significantly worse for the other values.

for the best fit that can be obtained for a given assumed H2O+ rest frequency, as a function of that frequency. The best fit shows a minimum close to the Mürtz et al. (1998) rest frequency and is significantly worse for the other values.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{15077fg3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa15077-10/Timg81.png)

|

Figure A.1:

Reduced |

| Open with DEXTER | |

References

- Brogan, C. L., & Troland, T. H. 2001, ApJ, 550, 799 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- de Graauw, Th., Helmich, F. P., Phillips, T. G., et al. 2010, A&A, 518, L6 [Google Scholar]

- Fish, V. L., Reid, M. J., Wilner, D. J., & Churchwell, E. 2003, ApJ, 587, 701 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gerin, M., de Luca, M., Black, J., et al. 2010, A&A, 518, L110 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Godard, B., Falgarone, E., Gerin, M., Hily-Blant, P., & De Luca, M. 2010, A&A, 520, A20 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Goicoechea, J. R., & Le Bourlot, J. 2007, A&A, 467, 1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Gwinn, C. R., Moran, J. M., & Reid, M. J. 1992, ApJ, 393, 149 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Indriolo, N., Geballe, T. R., Oka, T., & McCall, B. J. 2007, ApJ, 671, 1736 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kre▯owski, J., Beletsky, Y., & Galazutdinov, G. A. 2010, ApJ, 719, L20 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Le Petit, F., Roueff, E., & Herbst, E. 2004, A&A, 417, 993 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Le Petit, F., Nehmé, C., Le Bourlot, J., & Roueff, E. 2006, ApJS, 164, 506 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Liszt, H. S. 2007, A&A, 461, 205 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Mürtz, P., Zink, L. R., Evenson, K. M., & Brown, J. M. 1998, J. Chem. Phys., 109, 9744 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ossenkopf, V., Müller, H. S. P., Lis, D. C., et al. 2010, A&A, 518, L111 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Ott, S. 2010, in Astronomical Data Analysis Software and Systems XIX, ed. Y. Mizumoto, K.-I. Morita, & M. Ohishi, ASP Conf. Series [Google Scholar]

- Pilbratt, G. L., Riedinger, J. R., Passvogel, T., et al. 2010, A&A, 518, L1 [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Plume, R., Kaufman, M. J., Neufeld, D. A., et al. 2004, ApJ, 605, 247 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Strahan, S. E., Mueller, R. P., & Saykally, R. J. 1986, J. Chem. Phys., 85, 1252 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnentrucker, P., Neufeld, D. A., Phillips, T. G., et al. 2010, A&A, 521, L12 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Werf, P. P., Isaak, K. G., Meijerink, R., et al. 2010, A&A, 518, L42 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- van Dishoeck, E. F., & Black, J. H. 1986, ApJS, 62, 109 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Vastel, C., Caux, E., Ceccarelli, C., et al. 2000, A&A, 357, 994 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Wehinger, P. A., Wyckoff, S., Herbig, G. H., Herzberg, G., & Lew, H. 1974, ApJ, 190, L43 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wyrowski, F., Menten, K. M., Guesten, R., & Belloche, A. 2010, A&A, 518, A26 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

Footnotes

- ... W49N

![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

- Herschel is an ESA space observatory with science instruments provided by European-led Principal Investigator consortia and with important participation from NASA.

All Tables

Table 1: W49N absorption line components.

Table 2:

![]() and

and

![]() abundances.

abundances.

All Figures

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,height=5.5cm,clip]{15077fg1.eps}\vspace{-3mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa15077-10/Timg25.png)

|

Figure 1:

Spectra of H2O+

111-000 (green) and OH+ N=1-0 (blue)

transitions obtained toward W49N. The velocity scale applies to the

strongest hyperfine component, with assumed frequencies of

971 803.8 MHz for OH+ and 1 115 204 MHz for

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{15077fg2.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa15077-10/Timg31.png)

|

Figure 2:

Fit to the OH+ (top panel) and H2O+ (middle panel)

absorption spectra observed toward W49N. The black curve shows the

data, and the red curve is the fit obtained for the cloud parameters

listed in Table 1. The corresponding column densities per unit velocity

interval are shown in the bottom panel, for |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.5cm,clip]{15077fg3.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/13/aa15077-10/Timg81.png)

|

Figure A.1:

Reduced |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

Copyright ESO 2010

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.