| Issue |

A&A

Volume 515, June 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A55 | |

| Number of page(s) | 18 | |

| Section | Interstellar and circumstellar matter | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200913632 | |

| Published online | 09 June 2010 | |

The earliest phases of high-mass star formation: the

NGC 6334-NGC 6357 complex![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png) ,

,![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png) ,

,![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

D. Russeil1 - A. Zavagno1 - F. Motte2 - N. Schneider2 - S. Bontemps3 - A. J. Walsh4

1 - Laboratoire d'Astrophysique de Marseille - UMR 6110, CNRS - Université de Provence, 13388 Marseille Cedex 13, France

2 - Laboratoire AIM, CEA/DSM - INSU/CNRS - Université Paris

Diderot, IRFU/Service d'Astrophysique, CEA-Saclay, 91191 Gif-sur-Yvette

Cedex, France

3 - Laboratoire d'Astrophysiaue de Bordeaux, OASU - UMR 5804, CNRS

- Université de Bordeaux 1, 2 rue de l'Observatoire, BP 89, 33270

Floirac, France

4 - Centre for Astronomy, School of Engineering and Physical Sciences, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD, 4811, Australia

Received 10 November 2009 / Accepted 11 February 2010

Abstract

Context. Our knowledge of high-mass star formation has been mainly based on follow-up studies of bright sources found by IRAS,

and has thus been incomplete for its earliest phases, which are

inconspicuous at infrared wavelengths. With a new generation of

powerful bolometer arrays, unbiased large-scale surveys of nearby

high-mass star-forming complexes now search for the high-mass analog of

low-mass cores and class 0 protostars.

Aims. Following the pioneering study of Cygnus X, we investigate the star-forming region NGC 6334-NGC 6357 (![]() 1.7 kpc).

1.7 kpc).

Methods. We study the complex NGC 6334-NGC 6357 in an

homogeneous way following the previous work of Motte and collaborators.

We used the same method to extract the densest cores which are the most

likely sites for high-mass star formation. We analyzed the SIMBA/SEST

1.2 mm data presented in Munoz and coworkers, which covers all

high-column density areas (

![]() mag)

of the NGC 6334-NGC 6357 complex and extracted dense cores

following the method used for Cygnus X. We constrain the

properties of the most massive dense cores (M > 100

mag)

of the NGC 6334-NGC 6357 complex and extracted dense cores

following the method used for Cygnus X. We constrain the

properties of the most massive dense cores (M > 100 ![]() )

using new molecular line observations (as SiO, N2H+,H13CO+, HCO+ (1-0) and CH3CN) with Mopra and a complete cross-correlation with infrared databases (MSX, GLIMPSE, MIPSGAL) and literature.

)

using new molecular line observations (as SiO, N2H+,H13CO+, HCO+ (1-0) and CH3CN) with Mopra and a complete cross-correlation with infrared databases (MSX, GLIMPSE, MIPSGAL) and literature.

Results. We extracted 163 massive dense cores of which 16 are more massive than 200 ![]() .

These high-mass dense cores have a typical FWHM size of 0.37 pc, an average mass of

.

These high-mass dense cores have a typical FWHM size of 0.37 pc, an average mass of

![]()

![]() ,

and a volume-averaged density of

,

and a volume-averaged density of ![]()

![]() cm-3.

Among these massive dense cores, 6 are good candidates for hosting

high-mass infrared-quiet protostars, 9 cores are classified as

high-luminosity infrared protostars, and we find only one high-mass

starless clump (

cm-3.

Among these massive dense cores, 6 are good candidates for hosting

high-mass infrared-quiet protostars, 9 cores are classified as

high-luminosity infrared protostars, and we find only one high-mass

starless clump (![]() 0.3 pc,

0.3 pc, ![]()

![]() cm-3) that is gravitationally bound.

cm-3) that is gravitationally bound.

Conclusions. Since our sample is derived from a single molecular

complex and covers every embedded phase of high-mass star formation, it

provides a statistical estimate of the lifetime of massive stars. In

contrast to what is found for low-mass class 0 and class I

phases, the infrared-quiet protostellar phase of high-mass stars may

last as long as their more well known high-luminosity infrared phase.

As in Cygnus X, the statistical lifetime of high-mass protostars

is shorter than found for nearby, low-mass star-forming regions which

implies that high-mass pre-stellar and protostellar cores are in a

dynamic state, as expected in a molecular cloud where turbulent and/or

dynamical processes dominate.

Key words: dust, extinction - H II regions - stars: formation - radio continuum: ISM - submillimeter: ISM - radio lines: general

1 Introduction

High-mass (O- or B-type) stars play a major role in the energy budget and enrichment of galaxies, but their formation remains poorly understood. High-mass stars probably form in massive dense cores by the powerful accretion of gas onto a protostellar embryo (e.g. Beuther & Schilke 2004). However, the physical origin of these high accretion rates remains unclear with multiple mechanisms proposed including a high degree of turbulence (McKee & Tan 2002), converging flows (Heitsch et al. 2008), cloud collisions (Bonnell & Bate 2002), and competitive accretion on large scales (Bonnell et al. 2006).

From a purely observational point of view, the evolutionary sequence leading from clouds to OB stars is far from being well constrained. For instance, the existence and lifetime of the infrared (IR)-quiet phase analog to low-mass class 0 protostars and pre-stellar cores for high-mass stars is still a matter of debate (Motte et al. 2007). Moreover, the exact ordering and overlap of the different phases/diagnostics (pre-stellar, cold/infrared-quiet protostar, hot core, OH/H2O/CH3OH masers, warm/infrared-bright sources, HMPOs, hypercompact H II, UCH II regions) needs to be fully determined. Therefore, it is of crucial importance to build representative and unbiased samples of high-mass pre-stellar and protostellar objects, in large, nearby, high-mass star formation complexes.

(Sub)millimeter continuum mapping is the perfect tool for

systematically searching the earliest phases of star formation since

dust emission is mostly optically thin and directly traces cold,

high-mass dense cores on the verge of collapse, and young protostars

already collapsing. Dust continuum surveys in the submm range are

efficient for recognizing high-mass young stellar objects if the spatial resolution

is high enough to discriminate high-mass dense cores from their

surroundings. The typical size of dense cores is 0.1-0.2 parsec (e.g. Bergin & Tafalla 2007; Zinnecker & Yorke 2007), and the typical highest spatial resolution

achievable on millimeter telescopes is of the order of 10

![]() ,

which

translates into 0.15 pc at 3 kpc. We thus propose that the massive

complexes within 3 kpc offer a unique opportunity to study the

earliest phases of high-mass stars.

,

which

translates into 0.15 pc at 3 kpc. We thus propose that the massive

complexes within 3 kpc offer a unique opportunity to study the

earliest phases of high-mass stars.

The twin molecular complex NGC 6334-NGC 6357 (distance 1.7 kpc, size

![]() 68 pc

68 pc ![]()

![]() 80 pc) is one of the most prominent of

these massive complexes since it includes high-mass star formation at

different evolutionary stages (cores, embedded compact H II regions,

evolved optical H II regions). The high-column density parts of NGC

6334-NGC 6357 were delineated using near-IR extinction maps

produced from 2MASS and CO data (Schneider et al. 2010).

The extinction map was derived from the publicly available 2MASS point

source catalog by calculating the average reddening of stars with a

method adapted from those described in Lada et al. (1994), Lombardi & Alves (2001), and Cambrésy et al. (2006). The extinction was derived from the reddening of both [J-H] and [H-K] colors. From the stellar population model of Robin et al. (2003),

a predicted density of foreground stars was obtained at the complex

distance. For each 2 arcmin size pixel of the map, this expected

number of foreground stars was removed from the least reddened 2MASS

sources before deriving the average reddening. Figure 1 (up) shows a global view of this complex

in an H

80 pc) is one of the most prominent of

these massive complexes since it includes high-mass star formation at

different evolutionary stages (cores, embedded compact H II regions,

evolved optical H II regions). The high-column density parts of NGC

6334-NGC 6357 were delineated using near-IR extinction maps

produced from 2MASS and CO data (Schneider et al. 2010).

The extinction map was derived from the publicly available 2MASS point

source catalog by calculating the average reddening of stars with a

method adapted from those described in Lada et al. (1994), Lombardi & Alves (2001), and Cambrésy et al. (2006). The extinction was derived from the reddening of both [J-H] and [H-K] colors. From the stellar population model of Robin et al. (2003),

a predicted density of foreground stars was obtained at the complex

distance. For each 2 arcmin size pixel of the map, this expected

number of foreground stars was removed from the least reddened 2MASS

sources before deriving the average reddening. Figure 1 (up) shows a global view of this complex

in an H![]() image from the AAO/UKST H

image from the AAO/UKST H![]() survey of

the southern Galactic plane (Parker et al. 2005) with the

extinction map (angular resolution of 2') superimposed. Near the

H II regions, the extinction caused by dust corresponds well to the

extinction zones seen in H

survey of

the southern Galactic plane (Parker et al. 2005) with the

extinction map (angular resolution of 2') superimposed. Near the

H II regions, the extinction caused by dust corresponds well to the

extinction zones seen in H![]() (for example, the ``elephant trunk''

features in NGC 6334 seen at the border of the H

(for example, the ``elephant trunk''

features in NGC 6334 seen at the border of the H![]() extinction

zone). Figure 1 (down) reproduces the 1.2 mm continuum map

(angular resolution 24'') obtained by Muñoz et al. (2007),

where it becomes obvious that the highest column density regions

(

Av > 30 mag equivalent to a hydrogen column density larger than

3

extinction

zone). Figure 1 (down) reproduces the 1.2 mm continuum map

(angular resolution 24'') obtained by Muñoz et al. (2007),

where it becomes obvious that the highest column density regions

(

Av > 30 mag equivalent to a hydrogen column density larger than

3![]() 1022 cm-2) correspond to peak emission in dust

continuum. Figure 2 presents zooms at 8

1022 cm-2) correspond to peak emission in dust

continuum. Figure 2 presents zooms at 8 ![]() m (mosaics

of GLIMPSE residual images produced by the GLIMPSE team) of NGC 6334

and NGC 6357. The 8

m (mosaics

of GLIMPSE residual images produced by the GLIMPSE team) of NGC 6334

and NGC 6357. The 8 ![]() m channel of the Spitzer IRAC

instrument is dominated by PAH emission, excited by nearby

ultra-violet radiation. In these images, many 1.2 mm continuum

emission peaks clearly appear in the direction to IR extinction

patches but only a few correspond to 8

m channel of the Spitzer IRAC

instrument is dominated by PAH emission, excited by nearby

ultra-violet radiation. In these images, many 1.2 mm continuum

emission peaks clearly appear in the direction to IR extinction

patches but only a few correspond to 8 ![]() m emission.

For the central part of NGC 6334, Burton et al. (2000) detected evidence of dark lanes parallel to the ridges

and loops of 3.3

m emission.

For the central part of NGC 6334, Burton et al. (2000) detected evidence of dark lanes parallel to the ridges

and loops of 3.3 ![]() m PAH emission. Because of the lower resolution of our extinction map, we cannot compare it directly with,

but, if these dark lanes correspond well to optical extinction, only those aligned along the main ridge can be related to

the 1.2 mm dust emission.

m PAH emission. Because of the lower resolution of our extinction map, we cannot compare it directly with,

but, if these dark lanes correspond well to optical extinction, only those aligned along the main ridge can be related to

the 1.2 mm dust emission.

NGC 6334 is a well studied region (as reviewed by Persi &

Tapia (2008). At 1.2 mm, the central part of NGC 6334 consists of a

10 pc long filament associated with large extinction. At least seven

sites of high-mass star formation are observed (e.g. Loghran et al. 1986), recognizable in terms of water masers, H II regions (e.g. Carral et al. 2002),

and molecular outflows. Previous (sub)millimeter continuum studies of

NGC 6334 focused mainly on the northern portion of the filament

containing sources I and I(N) (e.g. Sandell 2000). These sources exhibit outflows and have

masses of between 200 and 400 ![]() .

The molecular emission associated

with NGC 6334 has a mean velocity of -4 km s-1 with a

velocity gradient (Kraemer & Jackson 1999) from the

center (

.

The molecular emission associated

with NGC 6334 has a mean velocity of -4 km s-1 with a

velocity gradient (Kraemer & Jackson 1999) from the

center (

![]() km s-1) to the edge of the ridge

(

km s-1) to the edge of the ridge

(

![]() km s-1). In addition to the far-IR

sources, NGC 6334 is a grouping of the well-known H II regions GUM

61, GUM 62, GUM 63, and GUM 64. On the basis of the distance modulus

determined by Persi & Tapia (2008), a mean distance of

km s-1). In addition to the far-IR

sources, NGC 6334 is a grouping of the well-known H II regions GUM

61, GUM 62, GUM 63, and GUM 64. On the basis of the distance modulus

determined by Persi & Tapia (2008), a mean distance of

![]() kpc is obtained for the exciting stars of these H II regions.

kpc is obtained for the exciting stars of these H II regions.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13632fg1.ps} \includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13632fg2.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13632-09/Timg33.png)

|

Figure 1:

Top: H |

| Open with DEXTER | |

NGC 6357 is a large H II region exhibiting an annular morphology in

the radio and optical (e.g. Lortet et al. 1984). Far-IR

continuum data detected several luminous (

![]() )

embedded sources coinciding with 12CO(1-0) and radio continuum

emission peaks (McBreen et al. 1983). In contrast to NGC 6334, almost no water maser emission is found in NGC 6357 (Healy et al. 2004). The brightest H II region (G353.2+0.9) has a

sharp boundary facing the massive open cluster Pismis 24. The distance

of NGC 6357 is usually taken to be that of Pismis 24: a distance of 1.7 kpc

was determined by Neckel (1978) and Lortet et al. (1984),

a distance of 1.1 kpc is obtained by Conti & Vacca (1984) for

a Wolf-Rayet star belonging to the cluster, and Massey et al. (2001)

give a distance of 2.5 kpc.

)

embedded sources coinciding with 12CO(1-0) and radio continuum

emission peaks (McBreen et al. 1983). In contrast to NGC 6334, almost no water maser emission is found in NGC 6357 (Healy et al. 2004). The brightest H II region (G353.2+0.9) has a

sharp boundary facing the massive open cluster Pismis 24. The distance

of NGC 6357 is usually taken to be that of Pismis 24: a distance of 1.7 kpc

was determined by Neckel (1978) and Lortet et al. (1984),

a distance of 1.1 kpc is obtained by Conti & Vacca (1984) for

a Wolf-Rayet star belonging to the cluster, and Massey et al. (2001)

give a distance of 2.5 kpc.

The kinematics of NGC 6357 is around -4 km s-1 (ionized gas, Caswell & Haynes 1987), which is similar to the mean velocity of NGC 6334 and strongly suggests that both regions are at the same distance (1.7 kpc). In addition, the extinction map (Fig. 1) and the morphology of the 1.2 mm SIMBA emission tend to indicate that NGC 6334 and NGC 6357 are connected by a filamentary structure, thus again suggesting that both regions belong to the same complex. We therefore adopt a common distance for NGC 6334 and NGC 6357 of 1.7 kpc.

In this paper, we follow the approach of Motte et al. (2007)

to characterize the star formation content of this high-mass

star-forming complex and constrain the evolutionary sequence of

high-mass star formation. Motte et al. (2007) applied a specific extraction method to a 1.2 mm continuum map

of the Cygnus X complex to extract dense cores. They complemented these data with SiO(2-1)

follow-up observations of the most likely progenitors of high-mass

stars, and determined the main characteristics of the millimeter

sources by searching for signposts of protostellar activity including

SiO emission (a tracer of outflow activity). In Cygnus X, they identified

33 high-mass dense cores of mean size, mass, and density of 0.13 pc, 91 ![]() ,

and

,

and

![]() cm-3, respectively. Seventeen dense cores were found to

harbor high-mass protostars in their IR-quiet phase.

Their unbiased survey of the high-mass young stellar objects in Cygnus X demonstrates

that high-mass IR-quiet protostars do exist, and that their

lifetimes should be comparable to those of more evolved high-luminosity

IR protostars. By comparing the number of high-mass protostars

and OB stars across the entire Cygnus X complex, a statistical lifetime of

cm-3, respectively. Seventeen dense cores were found to

harbor high-mass protostars in their IR-quiet phase.

Their unbiased survey of the high-mass young stellar objects in Cygnus X demonstrates

that high-mass IR-quiet protostars do exist, and that their

lifetimes should be comparable to those of more evolved high-luminosity

IR protostars. By comparing the number of high-mass protostars

and OB stars across the entire Cygnus X complex, a statistical lifetime of

![]() yr

for high-mass protostars was estimated, which is one order of magnitude

smaller than the lifetime of nearby low-mass protostars, and in

agreement with the free-fall time of Cygnus X dense cores.

yr

for high-mass protostars was estimated, which is one order of magnitude

smaller than the lifetime of nearby low-mass protostars, and in

agreement with the free-fall time of Cygnus X dense cores.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13632fg3.ps} \includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13632fg4.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13632-09/Timg37.png)

|

Figure 2:

GLIMPSE 8 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

2 The data

2.1 Dust continuum data at 1.2 mm

The 1.2 mm (250 GHz) continuum observations of NGC 6334 and NGC 6357

and the data reduction were performed by Muñoz et al. (2007).

The observations were completed using the 37-channel SEST Imaging

Bolometer

Array (SIMBA) in the fast-mapping mode. The angular resolution is

24''(full width at half maximum) corresponding to a spatial resolution

of

0.2 pc at 1.7 kpc. The typical pointing accuracy of the SEST

telescope

is 3''-5'' and SIMBA observations usually have a relative flux

uncertainty of 20% (Faúndez et al. 2004). The 1.2 mm

mosaic has a relatively homogeneous rms noise of ![]() 25

25

![]() .

The

filamentary morphology of the emission becomes evident in

Fig. 3.

The strongest emission peaks are associated with NGC 6334 and

NGC 6357. A filamentary structure, which we call ``inter-region

filament'', is identifiable between both regions.

.

The

filamentary morphology of the emission becomes evident in

Fig. 3.

The strongest emission peaks are associated with NGC 6334 and

NGC 6357. A filamentary structure, which we call ``inter-region

filament'', is identifiable between both regions.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=-90]{13632fg5.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13632-09/Timg38.png)

|

Figure 3:

Greyscale image of the 1.2 mm continuum emission toward NGC 6334 and NGC 6357 observed by Muñoz et al. (2007) with SIMBA (SEST). The white crosses indicate the 42 dense cores we have extracted that are more massive than 100 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

2.2 Molecular line observations

We performed pointed observations toward the 42 most massive dense

cores (M > 100 ![]() )

in the SiO (v = 0, J=2-1)

transition using the

22 m Mopra telescope. The observations were performed with the

3mm receiver and the Mopra spectrometer (MOPS) in the ``zoom mode''

that allows

to observe simultaneously up to 16 different frequencies. The

pointing

was regularly checked by observing SiO masers, typical corrections

required were smaller than 5''. The typical system temperature was

190 K. The velocity

resolution is 0.12 km s-1, the beam width at 86 GHz is 36'', and a main beam efficiency

)

in the SiO (v = 0, J=2-1)

transition using the

22 m Mopra telescope. The observations were performed with the

3mm receiver and the Mopra spectrometer (MOPS) in the ``zoom mode''

that allows

to observe simultaneously up to 16 different frequencies. The

pointing

was regularly checked by observing SiO masers, typical corrections

required were smaller than 5''. The typical system temperature was

190 K. The velocity

resolution is 0.12 km s-1, the beam width at 86 GHz is 36'', and a main beam efficiency

![]() of 0.49 (Ladd et al. 2005) was adopted.

All observations were performed in position switching

mode with the off-position a few arcminutes away. A total integrated

time of 11 min on-source was used to achieve a rms of

of 0.49 (Ladd et al. 2005) was adopted.

All observations were performed in position switching

mode with the off-position a few arcminutes away. A total integrated

time of 11 min on-source was used to achieve a rms of

![]() 0.05 K. Initial spectral processing (base-removal and

calibration onto a T*A scale) was performed with the ASAP

software

0.05 K. Initial spectral processing (base-removal and

calibration onto a T*A scale) was performed with the ASAP

software![]() . In addition to the SiO line, other molecular species (N2H+ (1-0),

H13CO+ (1-0), HCN (1-0), HNC (1-0), 13CS (2-1), HCO+ (1-0), and CH3CN (5-4))

were observed simultaneously (example spectra are presented in Fig. 4).

. In addition to the SiO line, other molecular species (N2H+ (1-0),

H13CO+ (1-0), HCN (1-0), HNC (1-0), 13CS (2-1), HCO+ (1-0), and CH3CN (5-4))

were observed simultaneously (example spectra are presented in Fig. 4).

![\begin{figure}

\par\mbox{\includegraphics[width=6cm,clip,angle=-90]{13632fg6.ps}...

...fg8.ps}\includegraphics[width=6cm,clip,angle=-90]{13632fg9.ps} }

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13632-09/Timg40.png)

|

Figure 4: Example of spectra obtained for the dense core 61 (the spectra for the other dense cores are given in the Appendix). All profiles (except for N2H+) have been smoothed to a velocity resolution of 0.3 km s-1. Upper panels: SiO ( left) and N2H+ ( right). Lower panels: on the left HCO+ superimposed on H13CO+ (thick line) and on the right HNC superimposed on 13CS (thick line). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

3 Analysis and results

3.1 The compact dense cores at 1.2 mm

Muñoz et al. (2007) identified a total of 181 clumps with

sizes ranging from 0.1 to 1 pc, and a median of 0.36 pc, and masses

ranging from 3 to 6000 ![]() with a mean value of 170

with a mean value of 170 ![]() .

They

extracted these clumps from NGC 6334 and the ``inter-region filament'' using the Clumpfind algorithm (Williams et al. 1994). Clumpfind defines a source as an emission peak that extends to a defined contour level (in Muñoz et al. 2007, 3

.

They

extracted these clumps from NGC 6334 and the ``inter-region filament'' using the Clumpfind algorithm (Williams et al. 1994). Clumpfind defines a source as an emission peak that extends to a defined contour level (in Muñoz et al. 2007, 3

![]() )

and

separates it from other peaks/sources at saddle points located below a given level (here again 3

)

and

separates it from other peaks/sources at saddle points located below a given level (here again 3![]() )

from the peaks.

However, this approach is not well suited to identifying compact and

dense sources and generally identifies cloud structures with a large

variety of sizes, which could thus be progenitors of single stars, small groups, or even clusters of stars.

)

from the peaks.

However, this approach is not well suited to identifying compact and

dense sources and generally identifies cloud structures with a large

variety of sizes, which could thus be progenitors of single stars, small groups, or even clusters of stars.

To build a more homogeneous sample of cloud

fragments that would be compact enough to be called dense cores

(![]() 0.1 pc, see the terminology given in e.g. Motte et al. 2007), we use the compact source extraction method

developed by Motte et al. (2003).

0.1 pc, see the terminology given in e.g. Motte et al. 2007), we use the compact source extraction method

developed by Motte et al. (2003).

Our reason for excluding diffuse molecular cloud structures from our

analysis is to focus on the most likely sites of current intermediate- to

high-mass star formation (here called massive dense cores).

The procedure described in more detail in Motte etal. (2007)

uses a multi-resolution analysis (Starck & Murtagh

2006) and the Gaussclumps program (Stuzki & Gusten

1990; Kramer et al. 1998).

The multi-resolution

technique is based on wavelet transformations and allows us to set a

cutoff length-scale that separates sources observed on different

spatial scales of the 1.2 mm map. We choose to filter out spatial

scales larger than 1 pc, corresponding to ``clumps'' according to

the terminology of Williams et al. (2000) and

Motte et al. (2007).

The compact (![]() 1 pc) fragments are then identified above the

1 pc) fragments are then identified above the

![]() (

(![]()

![]() )

level in the filtered 1.2 mm map by a

2D-Gaussian fitting.

As a consequence, all sources are on average compact and thus dense.

We extracted 163 dense cores in total, their sizes and 1.2 mm fluxes being

given in Table 6.

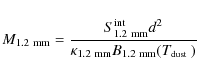

For each core, the total mass (dust + gas) was derived by assuming that

the 1.2 mm emission consists of thermal dust emission that is

largely optically

thin

)

level in the filtered 1.2 mm map by a

2D-Gaussian fitting.

As a consequence, all sources are on average compact and thus dense.

We extracted 163 dense cores in total, their sizes and 1.2 mm fluxes being

given in Table 6.

For each core, the total mass (dust + gas) was derived by assuming that

the 1.2 mm emission consists of thermal dust emission that is

largely optically

thin

|

(1) |

where

The temperature to be used in Eq. (1) is the mass-weighted dust

temperature of the cloud fragments, whose value could be determined

from gray-body fitting of their spectral energy distributions. This

measurement has been performed only for NGC 6334I(N) by Sandell (2000),

who found 30 K. In addition, Matthews et al. (2008) inferred a mean

temperature (derived from integrated flux density ratio 450 ![]() m/850

m/850 ![]() m) of

m) of ![]() 25 K for clumps in NGC 6334. This agrees

with Motte et al. (2007), who demonstrate that the temperature

generally measured in dense fragments forming high-mass stars is in

the range of 15-25 K. We then assume

25 K for clumps in NGC 6334. This agrees

with Motte et al. (2007), who demonstrate that the temperature

generally measured in dense fragments forming high-mass stars is in

the range of 15-25 K. We then assume

![]() in Eq. (1). The mass estimate is correct to within a

factor of 2 due to the uncertainty in the dust opacity, while an

uncertainty of 30% is implied by a temperature change from 15

to 25 K.

in Eq. (1). The mass estimate is correct to within a

factor of 2 due to the uncertainty in the dust opacity, while an

uncertainty of 30% is implied by a temperature change from 15

to 25 K.

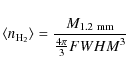

The volume-averaged densities are then estimated to be

|

(2) |

where

As no radio continuum data of sufficiently high resolution around 5 GHz is

available, the contribution of the free-free emission from the gas to

the mass calculation has been estimated from both the NVSS 1.4 GHz (beam

size

![]() )

image (Condon et al. 1998) and the 1.6

GHz (beam size

)

image (Condon et al. 1998) and the 1.6

GHz (beam size

![]() )

image (Muñoz et al. 2007). Since the 1.6 GHz image unfortunately covers only

NGC 6334, we used the NVSS 1.4 GHz for NGC 6357. We then measured the

radio flux in an aperture, convolved to the beam of the image, of the

cores. We extrapolated this flux to 1.2 mm by assuming a power law

dependence of

)

image (Muñoz et al. 2007). Since the 1.6 GHz image unfortunately covers only

NGC 6334, we used the NVSS 1.4 GHz for NGC 6357. We then measured the

radio flux in an aperture, convolved to the beam of the image, of the

cores. We extrapolated this flux to 1.2 mm by assuming a power law

dependence of

![]() ,

subtracted this flux from

,

subtracted this flux from

![]() ,

and recalculated the mass and density

(Table 6) from the corrected value of

,

and recalculated the mass and density

(Table 6) from the corrected value of

![]() .

Since the NVSS 1.4 GHz survey also covers NGC 6334, we compared the

mass obtained from the 1.4 and 1.6 GHz images and found good agreement

(the linear regression gives a slope of

.

Since the NVSS 1.4 GHz survey also covers NGC 6334, we compared the

mass obtained from the 1.4 and 1.6 GHz images and found good agreement

(the linear regression gives a slope of

![]() and constant

term of

and constant

term of

![]() ), which justifies our use of the 1.4 GHz data for

NGC 6357. The mass correction due to the free-free emission represents

on average 6% of the

), which justifies our use of the 1.4 GHz data for

NGC 6357. The mass correction due to the free-free emission represents

on average 6% of the

![]() .

However, at 1.4 GHz and 1.6 GHz

the emission is not always in the optically thin regime. This implies

that our free-free correction certainly underestimates the free-free contribution at 1.2 mm

and that in turn, the corrected masses are overestimated.

.

However, at 1.4 GHz and 1.6 GHz

the emission is not always in the optically thin regime. This implies

that our free-free correction certainly underestimates the free-free contribution at 1.2 mm

and that in turn, the corrected masses are overestimated.

Table 6 summarises the properties of the extracted cores: core number (Col. 1), core coordinates (Col. 2),

![]() (Col. 3),

the deconvolved FWHM size (Col. 4),

(Col. 3),

the deconvolved FWHM size (Col. 4),

![]() (Col. 5), free-free corrected mass (Col. 6) and free-free corrected density (Col. 7).

(Col. 5), free-free corrected mass (Col. 6) and free-free corrected density (Col. 7).

Amid the 181 clumps extracted by Muñoz et al. (2007),

68 have associations with one or several of our cores (only

11 clumps of Muñoz et al. are associated with several cores).

Our cores are all found in the most massive and densest clumps of Muñoz

et al. (2007): the mean mass and density of clumps with associated cores are 451 ![]() and

and ![]()

![]() cm-3, respectively while for clumps without associated cores they are 50

cm-3, respectively while for clumps without associated cores they are 50 ![]() and

and

![]()

![]() cm-3, respectively.

cm-3, respectively.

3.2 Molecular lines towards high-mass 1.2 mm dense cores

N2H+ is a good tracer of the highest density and cold regions of clouds because it appears to be mostly optically thin and less depleted onto dust grain surfaces than CO and other molecular species (Tafalla et al. 2002, 2004, 2006). The isolated 101-012 line width of the hyperfine structure is used to estimate the virial mass and help us to quantify infall motions by comparison with optically thick lines such as HCO+ and HNC.

The opacity and excitation temperature of the N2H+ 1![]() 0 line

was determined using the known hyperfine (HFS) structure pattern of

this transition. The 6 relative distances and intensities of HFS

components of the

0 line

was determined using the known hyperfine (HFS) structure pattern of

this transition. The 6 relative distances and intensities of HFS

components of the ![]() line were given as input to a simultaneous

Gaussian fit to all components, assuming equal excitation

temperature. For most of the sources, one velocity component, and thus

a single Gaussian HFS fit, was performed, using the ``Method HFS''

feature of GILDAS

line were given as input to a simultaneous

Gaussian fit to all components, assuming equal excitation

temperature. For most of the sources, one velocity component, and thus

a single Gaussian HFS fit, was performed, using the ``Method HFS''

feature of GILDAS![]() .

Few sources were found to have two velocity components and only one to

have three components (core 66). However, some of the densest and

most massive cores (cores 60, 61, and 63) exhibit a non-LTE HFS

pattern (the relative

intensities have not been correctly fitted) and rather broad

linewidths. These sources probably consist of several cloud fragments

along the line of sight which thus blending their N2H+ emission lines.

In Table 2,

we indicate the excitation temperature (equal for all components by

definition), the line center velocity of the molecular gas bulk emission

determined from the 123-013 (93.173.809 MHz) component of N2H+(the receiver was tuned to this frequency), the main beam temperature,

the full line width, and the opacity of the isolated 101-012 line

component. The typical uncertainty estimated for these determined parameters is 15%.

.

Few sources were found to have two velocity components and only one to

have three components (core 66). However, some of the densest and

most massive cores (cores 60, 61, and 63) exhibit a non-LTE HFS

pattern (the relative

intensities have not been correctly fitted) and rather broad

linewidths. These sources probably consist of several cloud fragments

along the line of sight which thus blending their N2H+ emission lines.

In Table 2,

we indicate the excitation temperature (equal for all components by

definition), the line center velocity of the molecular gas bulk emission

determined from the 123-013 (93.173.809 MHz) component of N2H+(the receiver was tuned to this frequency), the main beam temperature,

the full line width, and the opacity of the isolated 101-012 line

component. The typical uncertainty estimated for these determined parameters is 15%.

Table 2: Fitted parameters for the isolated N2H+ 101-012 line component using the ``method HFS'' from the GILDAS software

Both HCO+ and H13CO+ are usually used to probe the kinematics of the extended envelope and hence the bulk motion of the gas in the region. Because they are usually optically thin, 13CS and H13CO+, are often used to establish the systemic velocity of the dense cores. All the 42 high-mass dense cores observed (Table 3) were found to have velocities in agreement with the kinematics of NGC 6334 and NGC 6357.

The asymmetric rotator CH3CN is a good tracer of the conditions

in ``hot cores'' owing to its favorable abundance and excitation

in warm (![]() 100 K) and dense (

100 K) and dense (![]() 105 cm-3) regions. It

traces objects that are internally heated and its emission is more intense and more commonly

detected towards ultra-compact H II regions than towards isolated maser

sources (Purcell et al. 2006). Assuming local thermal

equilibrium and optically thin lines, the relative intensities of the

K components yield a direct measure of the kinetic temperature

(Purcell et al. 2006). Amid the 42 massive cores, 8 have well detected CH3CN, while 13 have no detectable CH3CN and

21 have barely detectable CH3CN.

From CH3CN

rotational diagrams, we can establish the temperature of the hot

component within the 8 dense cores for which several K components

of CH3CN are observed to be: 72.5 K for core 62; 62 K for core 54;

47 K for core 60;

105 cm-3) regions. It

traces objects that are internally heated and its emission is more intense and more commonly

detected towards ultra-compact H II regions than towards isolated maser

sources (Purcell et al. 2006). Assuming local thermal

equilibrium and optically thin lines, the relative intensities of the

K components yield a direct measure of the kinetic temperature

(Purcell et al. 2006). Amid the 42 massive cores, 8 have well detected CH3CN, while 13 have no detectable CH3CN and

21 have barely detectable CH3CN.

From CH3CN

rotational diagrams, we can establish the temperature of the hot

component within the 8 dense cores for which several K components

of CH3CN are observed to be: 72.5 K for core 62; 62 K for core 54;

47 K for core 60; ![]() 42 K for cores 63, 35, and 29; 31 K for core 3; and 20 K for core 61. All these dense cores are associated

with stellar activity. The temperature of the hot core inferred from CH3CN

(between 20 and 70 K) is normally higher than the dust temperature

mass-averaged over 0.2 pc. This does not contradict our assumption

that the mass-averaged temperature over cloud structures is 20 K

on average and probably slightly higher only for the above 8 sources.

42 K for cores 63, 35, and 29; 31 K for core 3; and 20 K for core 61. All these dense cores are associated

with stellar activity. The temperature of the hot core inferred from CH3CN

(between 20 and 70 K) is normally higher than the dust temperature

mass-averaged over 0.2 pc. This does not contradict our assumption

that the mass-averaged temperature over cloud structures is 20 K

on average and probably slightly higher only for the above 8 sources.

4 Origin and characteristics of high-mass dense cores

The NGC 6334 - NGC 6357 complex has already formed generations of

high-mass stars since it contains OB stars and H II regions. Here we

focus on its ability to form high-mass stars in the (near) future by

making a census of high-mass prestellar and protostellar dense cores and

comparing with the high mass star formation in Cygnus X. For Cygnus X, a

lower mass limit of 40 ![]() was adopted for dense cores to have a high

probability of forming 10-20

was adopted for dense cores to have a high

probability of forming 10-20 ![]() of stars, including at least one

high-mass star (Motte et al. 2007).

From Table 6, we note that the dense cores of NGC 6334-NGC 6357 are on average

of stars, including at least one

high-mass star (Motte et al. 2007).

From Table 6, we note that the dense cores of NGC 6334-NGC 6357 are on average ![]() 3 times larger than the dense cores found in Cygnus X by Motte et al. (2007).

This is mainly because the physical resolution is a factor of two poorer in

NGC 6334-NGC 6357 SIMBA images than in Cygnus X MAMBO2 ones, which needs to

be taken into account when adopting a low-mass limit. If we

assume

3 times larger than the dense cores found in Cygnus X by Motte et al. (2007).

This is mainly because the physical resolution is a factor of two poorer in

NGC 6334-NGC 6357 SIMBA images than in Cygnus X MAMBO2 ones, which needs to

be taken into account when adopting a low-mass limit. If we

assume![]() that the cores have a

that the cores have a

![]() density gradient, for high-mass stars

to be formed with a similar probability, the lower mass limit for the fragments extracted in NGC 6334-NGC 6357 needs

to be

density gradient, for high-mass stars

to be formed with a similar probability, the lower mass limit for the fragments extracted in NGC 6334-NGC 6357 needs

to be ![]() 3 times higher than the Cygnus X one.

We therefore choose a lower mass limit of 100

3 times higher than the Cygnus X one.

We therefore choose a lower mass limit of 100 ![]() to select a sample of high-mass

dense cores that are expected to be good candidate progenitors of high-mass stars.

to select a sample of high-mass

dense cores that are expected to be good candidate progenitors of high-mass stars.

Table 3: Turbulence support, SiO outflow, and gravitational infall of the most massive dense cores of NGC 6334 - NGC 6357.

The 42 compact cloud fragments identified in NGC 6334-NGC 6357 with

masses higher than 100 ![]() have sizes ranging from 0.16 to 0.63 pc

with a mean size of

have sizes ranging from 0.16 to 0.63 pc

with a mean size of ![]() 0.36 pc (see Table 6) and mean

volume-averaged density of

0.36 pc (see Table 6) and mean

volume-averaged density of ![]()

![]() cm-3.

After correcting for the free-free

contamination, the mass range of our sample is between 101

cm-3.

After correcting for the free-free

contamination, the mass range of our sample is between 101 ![]() and

1951

and

1951 ![]() .

The cloud structures extracted in NGC 6334-NGC 6357 are

thus slightly smaller in size and 10 times denser than

typical HMPOs (high-mass protostellar objects, Beuther et al. 2002) and IRDC (infrared dark cloud, Rathborne et al. 2006) clumps (HMPOs and IRDCs have typical sizes of 0.5 pc and their respective typical mass and density are 290

.

The cloud structures extracted in NGC 6334-NGC 6357 are

thus slightly smaller in size and 10 times denser than

typical HMPOs (high-mass protostellar objects, Beuther et al. 2002) and IRDC (infrared dark cloud, Rathborne et al. 2006) clumps (HMPOs and IRDCs have typical sizes of 0.5 pc and their respective typical mass and density are 290 ![]() and 150

and 150 ![]() and

and

![]() cm-3 and

cm-3 and

![]() cm-3; see Table 4

of Motte et al. 2007). Therefore, the NGC 6334 - NGC 6357 dense cores are on average, more likely host precursors of high-mass stars.

cm-3; see Table 4

of Motte et al. 2007). Therefore, the NGC 6334 - NGC 6357 dense cores are on average, more likely host precursors of high-mass stars.

4.1 Correlation of 1.2 mm dense cores with signposts of stellar activity

To determine the origin of the massive cores detected at 1.2 mm, we studied their spatial association with the following signposts of stellar activity.

4.1.1 Association with Spitzer/GLIMPSE

The position of sources in the [3.6]-[4.5] versus [5.8]-[8] diagram is related to the presence of circumstellar dust. The principal classification scheme for low-mass star formation is the class 0-I-II-III system, which notably characterizes objects in terms of their IR excesses or SEDs (e.g. Adams et al. 1987; André et al. 1993, 2000). Class 0 and I objects are understood to be protostars surrounded by dusty infalling envelopes, which would explain both the relatively strong far-IR emission and significant near-IR extinction from their envelopes. They are deeply embedded objects with a spectral energy distribution (SED) that peaks in the submillimeter or the far-IR, indicating that the source of emission is cold dust. Class II systems are optically visible stars with disks, and thus exhibit a smaller IR excess and near-IR extinction (unless observed edge-on). Class III objects are essentially stars without significant amounts of circumstellar dust.

To establish an association of dense cores with class I and class II objects (see Table A.1), we used the IRAC/GLIMPSE point source catalogue (http://irsa.ipac.caltech.edu/data/SPITZER/GLIMPSE/). The class is defined using [5.8]-[8.0] and [3.6]-[4.5] colors and based on models of disk or envelopes or both, Allen et al. (2004) defined the criteria:

class I: [5.8]-[8.0] ![]() 0.35 and [3.6]-[4.5] > 0.4,

0.35 and [3.6]-[4.5] > 0.4,

class II: [5.8]-[8.0] ![]() 0.35 and [3.6]-[4.5]

0.35 and [3.6]-[4.5] ![]() 0.4.

0.4.

The distribution of class II sources in the [3.6]-[4.5] color diagram depends mainly on the accretion rate, while the disk inclination and the grain properties explain the spread in the [5.8]-[8.0] color. The larger distribution spread in both colors, [3.6]-[4.5] and [5.8]-[8.0], for class I objects is due to the higher temperature and density of the envelope. However, an extinction of 30 mag causes a shift of about 0.4 mag toward redder [3.6]-[4.5] indices, implying that class II sources can fall in the class I area. Based on the mean extinction found for the dense cores (estimated from the extinction map), we can consider a source as a true class I, if its [3.6]-[4.5] color is above 0.8. Hartmann et al. (2005) confirm the criteria of Allen et al. (2004) on the basis of observations of the Taurus pre-main sequence stars.

We establish a physical association with Spitzer/GLIMPSE point sources when the Spitzer/GLIMPSE point source(s) fall within 6''(i.e. upper limit to the sum of the maximum pointing error 5'' and the typical GLIMPSE position accuracy 0.3'') of the dense core center. This is justified because high-mass protostars are expected to form at the center of the dense core. In this way, only 10 dense cores have such an association. They are all associated with true class I objects except core 152, which is associated with a class II object.

Table 4:

High-mass young stellar objects in NGC 6334-NGC 6357 (M > 200 ![]() )

compared to Cygnus X cores and HMPOs clumps.

)

compared to Cygnus X cores and HMPOs clumps.

The Spitzer/GLIMPSE point sources sample may be contaminated by galaxies. Chavarria et al. (2008) established a criterion to separate young stellar objects from galaxies, which is roughly that [4.5]< 14.5. Assuming that it can be applied to NGC 6334-NGC 6357, all of the Spitzer/GLIMPSE point sources associated with the dense massive cores have [4.5] between 6.21 and 11.44 and are thus most probably young stellar objects.

4.1.2 Association with radio sources and masers

We used the SIMBAD database![]() to look for additional signposts of stellar activity provided by centimeter free-free emission and OH, H2O, and CH3OH masers. We define an association when the object is located within the FWHM size of the core.

to look for additional signposts of stellar activity provided by centimeter free-free emission and OH, H2O, and CH3OH masers. We define an association when the object is located within the FWHM size of the core.

An association with a source of free-free emission was established by

using the 1.4 GHz SGPS survey (Haverkorn et al. 2006) and

the 843 MHz MOST survey (Green et al. 1999), which were both correlated

with the NVSS catalog given by Condon et al. (1998) and with White (2005) catalog. We

cannot check the nature of the detected cm-emission with the current

database, but it is probably caused by the emission of

H II regions. Since a systematic search for masers in the area

studied here does not exist, we checked the dense core association

with known masers in the literature. We found a correlation with maser

emission for 8 sources (e.g. Pestalozzi et al. 2005, Caswell et al. 2008, Moran et al. 1980; Caswell & Phillips 2008; Val'tts et al. 1999),

3 of which are also radio sources. The systemic velocity of the

associated maser(s) is in good agreement with the general kinematics of

NGC 6334-6357, except for core 163 (methanol and

H2O masers,

![]() km s-1). Either these masers

are caused by an outflow or core 163 is not associated with NGC 6334 - 6357.

km s-1). Either these masers

are caused by an outflow or core 163 is not associated with NGC 6334 - 6357.

4.1.3 Association with 24  m sources

m sources

Correlation with mid-IR sources was determined by using MSX-21 ![]() m, and Spitzer/MIPSGAL-24

m, and Spitzer/MIPSGAL-24 ![]() m (Carey et al. 2009) data.

For MSX we used the point-source catalogue (Egan et al. 1999), while for Spitzer/MIPSGAL we used aperture

photometry from the post-basic calibrated data available at IPAC

server

m (Carey et al. 2009) data.

For MSX we used the point-source catalogue (Egan et al. 1999), while for Spitzer/MIPSGAL we used aperture

photometry from the post-basic calibrated data available at IPAC

server![]() .

As high-mass protostars are expected to form at the center of the dense core and because little Spitzer/MIPSGAL 24

.

As high-mass protostars are expected to form at the center of the dense core and because little Spitzer/MIPSGAL 24 ![]() m or MSX-21

m or MSX-21 ![]() m

emission can be extended, we define a physical association when the

source falls within the delimitation of the core but not farther than

23'' from the dense core center. This value is adopted on the basis of

the association of core 51 with MSX 21

m

emission can be extended, we define a physical association when the

source falls within the delimitation of the core but not farther than

23'' from the dense core center. This value is adopted on the basis of

the association of core 51 with MSX 21 ![]() m extended emission

for which association is morphologicaly clear, while the MSX point-source catalogue position is at 23'' from the SIMBA peak.

m extended emission

for which association is morphologicaly clear, while the MSX point-source catalogue position is at 23'' from the SIMBA peak.

The 24 ![]() m flux was measured using SAOImage DS9 with ``funtools'',

through both a 6.5'' and 13'' circular aperture (depending on

the source size). The background correction is estimated from a 7''-13'',

20-30'', or 40-50'' annulus, depending on the background structure and

crowding. An aperture correction is applied depending on the size of

the background annulus (Engelbracht et al. 2007).

The typical uncertainty in the aperture measurement deduced from the ``funtools'' errors is 2%.

Since the uncertainty in the MIPS flux is, however, dominated by the background, we estimated a typical uncertainty of 20%

from different local background measurements.

Owing to the sensitivity of the MIPSGAL survey, the brightest areas are

saturated. For cores in these areas, we adopted the MSX-21

m flux was measured using SAOImage DS9 with ``funtools'',

through both a 6.5'' and 13'' circular aperture (depending on

the source size). The background correction is estimated from a 7''-13'',

20-30'', or 40-50'' annulus, depending on the background structure and

crowding. An aperture correction is applied depending on the size of

the background annulus (Engelbracht et al. 2007).

The typical uncertainty in the aperture measurement deduced from the ``funtools'' errors is 2%.

Since the uncertainty in the MIPS flux is, however, dominated by the background, we estimated a typical uncertainty of 20%

from different local background measurements.

Owing to the sensitivity of the MIPSGAL survey, the brightest areas are

saturated. For cores in these areas, we adopted the MSX-21 ![]() m

flux. To scale these fluxes to the 24

m

flux. To scale these fluxes to the 24 ![]() m, fluxes we measured the

24

m, fluxes we measured the

24 ![]() m flux of about 20 known MSX-21

m flux of about 20 known MSX-21 ![]() m

sources and

derived the best-fit linear regression (slope = 1.13 constant

term=-0.64). Assuming that the relation is applicable to both high

fluxes and the spectral distribution of our objects, we then multiplied

all 21

m

sources and

derived the best-fit linear regression (slope = 1.13 constant

term=-0.64). Assuming that the relation is applicable to both high

fluxes and the spectral distribution of our objects, we then multiplied

all 21 ![]() m

flux by 1.13. In this way, 51 dense cores have a 24

m

flux by 1.13. In this way, 51 dense cores have a 24 ![]() m flux (see Table A.1).

m flux (see Table A.1).

For a large sample of red sources, Robitaille et al. (2008) show that young stellar objects and AGB stars

can generally be separated using simple color-magnitude criteria, sources with [4.5]>7.8 and [8.0]-[24.0] ![]() 2.5 probably being

young stellar objects. All cores associated with Spitzer/GLIMPSE and 24

2.5 probably being

young stellar objects. All cores associated with Spitzer/GLIMPSE and 24 ![]() m fluxes (2 cores have Spitzer/GLIMPSE

but no Spitzer/MIPSGAL detection and thus cannot be classified ) follow these criteria and are probably young

stellar objects. The other cores with 24

m fluxes (2 cores have Spitzer/GLIMPSE

but no Spitzer/MIPSGAL detection and thus cannot be classified ) follow these criteria and are probably young

stellar objects. The other cores with 24 ![]() m

flux detections should only be labeled as having a high probability of

being young objects since contamination by planetary nebulae or

background galaxies represents at most 3% of all red sources

(Robitaille et al. 2008).

m

flux detections should only be labeled as having a high probability of

being young objects since contamination by planetary nebulae or

background galaxies represents at most 3% of all red sources

(Robitaille et al. 2008).

4.1.4 High-luminosity and infrared-quiet cores

Dense cores that are luminous at IR wavelengths are usually

considered to be good high-mass protostars or UCH II candidates

(e.g. Wood & Churchwell 1989). Following Motte et al. (2007), we

qualify as ''high-luminosity IR sources'' those dense cores of

bolometric luminosity higher than 10

![]() ,

which

corresponds to that of a B3 star on the main sequence. This luminosity

converts into a MIPS

,

which

corresponds to that of a B3 star on the main sequence. This luminosity

converts into a MIPS ![]() m flux of

m flux of ![]() 15 Jy, this flux being

estimated in the same way as described in Motte et al. (2007), assuming

that the luminosity of high-mass protostars is dominated by their mid-

to far-IR luminosity and that their average colors are as defined by

Wood & Churchwell (1989, see their Table 1). Following this

definition, we have 11 high-luminosity and high mass (M > 100

15 Jy, this flux being

estimated in the same way as described in Motte et al. (2007), assuming

that the luminosity of high-mass protostars is dominated by their mid-

to far-IR luminosity and that their average colors are as defined by

Wood & Churchwell (1989, see their Table 1). Following this

definition, we have 11 high-luminosity and high mass (M > 100 ![]() )

dense cores, 9 of which are associated with star formation activity

(Fig. 5). In contrast, only 3 out of 30 high mass IR-quiet dense cores exhibit

stellar activity. These 27 high-mass IR-quiet dense cores

are probably high-mass pre-stellar dense cores.

)

dense cores, 9 of which are associated with star formation activity

(Fig. 5). In contrast, only 3 out of 30 high mass IR-quiet dense cores exhibit

stellar activity. These 27 high-mass IR-quiet dense cores

are probably high-mass pre-stellar dense cores.

4.2 Turbulence level and kinematics

From molecular lines we investigate here the turbulence level and the kinematics (virial mass, infall, outflow) of the high-mass cores.

4.2.1 Turbulence

The width of emission lines in star-forming clouds are indicative

the gravitational boundness of a molecular

region. According to Goldsmith (1987), sites of high-mass star formation

are characterized by large line widths. In contrast, dark clouds which are

isolated sites of low-mass star formation, have considerably smaller

line widths. Caselli et al. (2002) derived typical line widths

of 0.33 km s-1 for clumps in which no IRAS source is

detected.

In our sample the line widths of the N2H+ isolated line vary

from 1.13 to 5.38 km s-1 (see Table 1) and are thus much larger than those in the Caselli et al. (2002) study.

In addition, the N2H+ line width is much higher than the

thermal width (0.62 km s-1 for T=20 K), emphasizing the importance of

turbulence and other non-thermal motions such as outflow, infall, and

rotation. However the relative contributions of these systematic

motions to the line width appear to be small compared to the

turbulent component (Mardones et al. 1997). Following Kirk

et al. (2007), we calculate the non-thermal component

![]() of the velocity dispersion from the width of the

isolated N2H+ line and derive the level of internal

turbulence

of the velocity dispersion from the width of the

isolated N2H+ line and derive the level of internal

turbulence

![]() defined by Kirk et al. (2007) to be the

ratio of

defined by Kirk et al. (2007) to be the

ratio of

![]() to the mean thermal velocity dispersion of the

gas (sound speed of 0.23 km s-1). We note that all cores have

to the mean thermal velocity dispersion of the

gas (sound speed of 0.23 km s-1). We note that all cores have

![]() and that on average

and that on average

![]() is slightly larger for

NGC 6334 (

is slightly larger for

NGC 6334 (

![]() )

than for NGC 6357

(

)

than for NGC 6357

(

![]() ).

).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=6.5cm,angle=-90]{13632fg10.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13632-09/Timg117.png)

|

Figure 5:

Separating the high-luminosity sources from IR-quiet dense cores on the basis of their 24 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

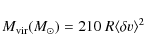

4.2.2 The virial mass

For the 42 high-mass dense cores, the virial mass was calculated to be

(e.g. Walsh et al. 2007)

|

(3) |

where R is the core radius (in pc) and

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=6.5cm,angle=-90,clip]{13632fg11.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13632-09/Timg125.png)

|

Figure 6:

Integrated intensity of SiO (2-1) detected toward the dense cores with

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

4.2.3 SiO outflow

The next step is to establish the proto-stellar status on the basis of the SiO outflow

detection. From Table 3, we note that the SiO outflow

intensity and velocity are similar to that detected in

Cygnus X and for a large sample of high-mass objects (Harju et al. 1998).

The detection rates are 67% for NGC 6334 and 25% for NGC

6357. The global detection rate is thus 49% (58% and 47% for

high-luminosity and IR-quiet objects, respectively), clearly different

from the Cygnus X value of 93%. This is probably not caused by

different instrumental sensitivities because we designed our SiO

observations to reach similar detection limits as the observation

performed for Cygnus X. In addition, the faintest Cygnus X

SiO peak intensity detected is above the faintest SiO detection of our

sample.

For a sample of H2O and OH masers sources and ultracompact H II regions, Harju et al. (1998) measured a detection rate that decreases with Galactocentric distance and

increases with FIR luminosity. They found a rate of 58% for

Galactocentric distances of between 6 and 8 kpc (the Galactocentric distance of NGC 6334 - NGC 6357 is ![]() 6.83 kpc) in agreement with our value.

6.83 kpc) in agreement with our value.

On average, we also note that the high-luminosity and IR-quiet

dense cores with SiO outflows are, respectively, 15 and 4 times denser

than those without a SiO outflow. We can estimate that the typical

density that a core should have to ensure an SiO outflow is ![]()

![]() cm-3.

This may explain why the detection rate is higher in Cygnus X,

because the Cygnus X dense cores are on average less massive but

denser (

cm-3.

This may explain why the detection rate is higher in Cygnus X,

because the Cygnus X dense cores are on average less massive but

denser (

![]() cm-3) than the NGC 6334 - NGC 6357 dense cores (

cm-3) than the NGC 6334 - NGC 6357 dense cores (

![]() cm-3). Finally, in

contrast to Motte et al. (2007) the high-mass IR-quiet dense

cores are not found to clearly exhibit brighter SiO emission than IR-bright

dense cores.

cm-3). Finally, in

contrast to Motte et al. (2007) the high-mass IR-quiet dense

cores are not found to clearly exhibit brighter SiO emission than IR-bright

dense cores.

4.2.4 Infall motions

To complete our census of high-mass prestellar and protostellar

dense cores, we now search for signposts of infall motions.

Infall motions can be studied by investigating the

profiles of optically thick molecular lines (here we use HCO+ and

HNC) that have a blue asymmetric structure, i.e. a double peak with

a brighter blue peak, or a skewed single blue peak (e.g.

Myers et al. 1996; Mardones et al. 1997).

To exclude the possibility that the profile is caused by two velocity

components along the line of sight, an optically thin line needs to

peak close to the velocity of the self-absorption dip of the optically thick

line (e.g. Zhou et al. 2003; Choi et al. 1995; Wu &

Evans 2003). By examining the line profiles of the optically thin

H13CO+ line, we identified dense cores with these multiple

emitting regions along the line of sight and find that most of them

are composed of a single broad line with a self-absorption dip.

The optically thick HNC and HCO+

lines (see Appendix B), however,

often show non-Gaussian, broad lines that are caused by several clumps

along the line-of-sight and/or bulk motions of the envelope

gas (e.g. cores 9, 28, 35, 37, 52) and outflow emission (e.g. cores

35, 37, 46, 52, 54). This is expected since the beam of around 40''is

rather large. To extract more distinctive infall profiles, higher

angular

resolution is required. However, as a first order approximation, we

can still quantify the blue asymmetry of a line by using the asymmetry

parameter ![]() V defined by Mardones et al. (1997)

V defined by Mardones et al. (1997)

![]() .

This is the difference between the peak velocities of an optically thick line

.

This is the difference between the peak velocities of an optically thick line

![]() and

an optically thin line V(thin) in units of the optically thin line

full width at half-maximum (FWHM) dV(thin). We adopt the criterion

of Mardones et al. (1997) for blue (

and

an optically thin line V(thin) in units of the optically thin line

full width at half-maximum (FWHM) dV(thin). We adopt the criterion

of Mardones et al. (1997) for blue (

![]() -0.25) and red

asymmetry (

-0.25) and red

asymmetry (

![]() ). We assume HNC and HCO+ to be optically

thick lines and the isolated component of the N2H+ hyperfine structure to be the optically thin line used to determine

). We assume HNC and HCO+ to be optically

thick lines and the isolated component of the N2H+ hyperfine structure to be the optically thin line used to determine ![]() V (see Table 3).

V (see Table 3).

Another approach to characterizing infall motion in double-peak spectra

is to measure the ratio of the blue to red peak (Wu & Evans 2003). A ``blue profile'' fulfills the criterion

![]() .

The results are given in Table 3 and line asymmetry measured from

HCO+ and HNC are presented in Fig. 7.

.

The results are given in Table 3 and line asymmetry measured from

HCO+ and HNC are presented in Fig. 7.

We now have four criteria to quantify infall and establish that infall

has been detected when two of them are fulfilled. In

this way, apart from the cores already associated with outflow

emission and those suspected to be due to two components along the

line of sight, only cores 18 and 23 have a high probability of

exclusively exhibiting infall motions. The core 18 - due to its 24 ![]() m

counterpart and its infall motion - has a high probability of being

proto-stellar in nature. For core 23, on the basis of only infall

motion, no clear decision can be made about its proto-stellar nature.

m

counterpart and its infall motion - has a high probability of being

proto-stellar in nature. For core 23, on the basis of only infall

motion, no clear decision can be made about its proto-stellar nature.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=6.5cm,angle=-90,clip]{13632fg12.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13632-09/Timg134.png)

|

Figure 7:

Comparison of the measured asymetry in HCO+ and

HNC. The dashed lines mark

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

5 Lifetime and massive star formation in NGC 6334 - NGC 6357

Table 3 summarizes the characteristics of the most massive denses cores (M > 100 ![]() ).

The cores 62 and 63 were classified as a UCH II

region and IR-quiet protostar, respectively, because they are,

respectively, the well studied regions NGC 6334I and

NGC 6334I(N), and we can compare with the literature. This agrees

with the results of Walsh et al. (2010)

and Thorwirth et al. (2003), who provide evidence, on the basis of a multi-line (around 3 mm) analysis, that NGC 6334I appears

more evolved than NGC 6334I(N).

).

The cores 62 and 63 were classified as a UCH II

region and IR-quiet protostar, respectively, because they are,

respectively, the well studied regions NGC 6334I and

NGC 6334I(N), and we can compare with the literature. This agrees

with the results of Walsh et al. (2010)

and Thorwirth et al. (2003), who provide evidence, on the basis of a multi-line (around 3 mm) analysis, that NGC 6334I appears

more evolved than NGC 6334I(N).

Since our sample is complete for embedded high-mass young stellar objects, we can statistically estimate the relative lifetime of high-mass IR-quiet and high-luminosity protostars as well as prestellar sources. To achieve this, we assume a constant star-formation rate over the past 1-2 Myr, which is justifiable because the complex exhibits sources at all stages of evolution distributed not too far apart from each other within the cloud. The lifetime estimated here is close to that found by the study in Cygnus X for which no burst of star formation had been quantitatively established (Motte et al. 2007). We also need to estimate the content of massive stars (earlier than B3) in NGC 6334 and NGC 6357, since the statistical lifetime is measured relative to the known age of OB stars. Absolute lifetimes of the different high-mass phases may also be estimated from their free-fall dynamical timescale.

In NGC 6357, two open clusters are referenced in the literature, the well known Pismis 24 and AH03J1726-34.4 (Dias et al. 2002). For Pismis 24, Wang et al. (2008) identified from X-ray studies 34 O-B3 stars, while Damke et al. (2006) estimate a density of 40 stars per arcmin2 for AH03J1726-34.4 (size 2.6 arcmin), i.e., approximately 200 stars for this cluster leading to about 60 O-B3 stars.

For NGC 6334, Neckel (1978) found 14 O-B3 stars from optical photometry and Bica et al. (2003) listed 7 embedded clusters/groups associated with radio sources. Tapia et al. (1996) estimated that the clusters towards NGC 6334I and NGC 6334E contain 93 and 12 O-B3 stars, respectively. In parallel, Bochum 13, a cluster at the north-west border of NGC 6334 contains 5 O-B3 stars (McSwain 2005), and UBV data from a field comprising NGC 6334, NGC 6357 and the inter-region filament provide an estimate of 40 O-B3 stars (Russeil et al. in preparation). We thus estimate 300 massive stars (earlier than B3) for the entire complex.

For Cygnus X and its total of 120 O stars, the expected number of massive stars (earlier than B3) can be inferred to be 660 using the mass function slope obtained and both the spectral type and mass conversion used in Knödlseder (2000).

From Fig. 5, we note that most of the cores with radio and/or maser counterparts have M > 200 ![]() .

For Cygnus X, observed with a 0.09 pc resolution, the mass selection of M > 40

.

For Cygnus X, observed with a 0.09 pc resolution, the mass selection of M > 40 ![]() allowed us to select dense cores with high-mass star activity (H II

region, strong infrared counterpart, masers, or strong SiO outflow).

This difference can be explained by our lower spatial resolution than

the observations for Cygnus X, which implies we select less dense

cores than in Cygnus X. In the case of NGC 6334 -

NGC 6357, the average density (

allowed us to select dense cores with high-mass star activity (H II

region, strong infrared counterpart, masers, or strong SiO outflow).

This difference can be explained by our lower spatial resolution than

the observations for Cygnus X, which implies we select less dense

cores than in Cygnus X. In the case of NGC 6334 -

NGC 6357, the average density (

![]() cm-3, while the average density is

cm-3, while the average density is

![]() cm-3 for M > 200

cm-3 for M > 200 ![]() cores)

and the weak stellar activity found towards starless 100

cores)

and the weak stellar activity found towards starless 100 ![]() < M < 200

< M < 200 ![]() cores suggest they are probably forming intermediate- to low-mass

stars. A large part of the IR-quiet massive cores with mass

between 100 and 200

cores suggest they are probably forming intermediate- to low-mass

stars. A large part of the IR-quiet massive cores with mass

between 100 and 200 ![]() may

therefore harbor low-mass to intermediate-mass protostars that are not

detected here, while others could be low-mass to intermediate-mass

pre-stellar cores.

This result indirectly shows that starless clumps probably have density

profiles flatter than r-2 and confirms that

resolutions of 0.1 pc are necessary to focus on sites of high-mass star formation. After selecting cores with M > 200

may

therefore harbor low-mass to intermediate-mass protostars that are not

detected here, while others could be low-mass to intermediate-mass

pre-stellar cores.

This result indirectly shows that starless clumps probably have density

profiles flatter than r-2 and confirms that

resolutions of 0.1 pc are necessary to focus on sites of high-mass star formation. After selecting cores with M > 200 ![]() ,

the number of high-mass progenitors is 16 (6 IR-quiet massive

cores, 9 high-luminosity protostars, 1 starless clump). In

addition, this new mass selection brings the SiO detection rate of the

NGC 6334-NGC 6357 massive dense cores yet closer to that of

Cygnus X (80% versus 93%, see Table 4).

,

the number of high-mass progenitors is 16 (6 IR-quiet massive

cores, 9 high-luminosity protostars, 1 starless clump). In

addition, this new mass selection brings the SiO detection rate of the

NGC 6334-NGC 6357 massive dense cores yet closer to that of

Cygnus X (80% versus 93%, see Table 4).

Table 5:

High-mass young objects in NGC 6334 - NGC 6357 (M > 200 ![]() )

at various stages of the high-mass star formation process.

)

at various stages of the high-mass star formation process.

Table 5 summarizes the number, characteristics, and lifetimes of our massive dense core sample (M > 200 ![]() )

at each evolutionary stage and compares them to those found in Cygnus X and nearby low-mass star-forming regions.

Following the definition of Motte et al. (2007), a starless clump is defined as a high-mass core without any indication of stellar activity,

an IR-quiet high-mass protostar is a high-mass core

with stellar activity (H II region, masers, or SiO outflow) but

)

at each evolutionary stage and compares them to those found in Cygnus X and nearby low-mass star-forming regions.

Following the definition of Motte et al. (2007), a starless clump is defined as a high-mass core without any indication of stellar activity,

an IR-quiet high-mass protostar is a high-mass core

with stellar activity (H II region, masers, or SiO outflow) but ![]() m flux lower than 15 Jy (see Sect. 4.1.4), and a high-luminosity IR core

is a high-mass core with stellar activity and a

m flux lower than 15 Jy (see Sect. 4.1.4), and a high-luminosity IR core

is a high-mass core with stellar activity and a ![]() m flux higher than 15 Jy.

Table 4

compares the characteristics of the high-mass protostellar dense cores

(IR-quiet and high-luminosity IR protostellar cores) of

NGC 6334-NGC 6357 to those in Cygnus X and to HMPOs. In

both tables, values given for Cygnus X and HMPOs are taken from

Motte et al. (2007).

m flux higher than 15 Jy.

Table 4

compares the characteristics of the high-mass protostellar dense cores

(IR-quiet and high-luminosity IR protostellar cores) of

NGC 6334-NGC 6357 to those in Cygnus X and to HMPOs. In

both tables, values given for Cygnus X and HMPOs are taken from

Motte et al. (2007).

On average, the size of the cores in NGC 6334-NGC 6357 are similar whatever the evolutionary stage of the core, while the mean mass, hence the mean density, increases from starless clumps to high-luminosity cores. This is consistent with the material of dense cores concentrating itself towards its center during the star formation process.

Evans et al. (2009) find median lifetimes

of

![]() yr,

yr,

![]() yr, and

yr, and

![]() yr,

respectively, for low-mass pre-stellar cores, class 0, and class I

stars. However, substantial variation in lifetime estimates from cloud

to cloud are observed. For example, Wilking et al. (1989) in

Ophiuchus and Kenyon et al. (1990) in the Taurus-Auriga region

measure for class I sources a lifetime of 2-

yr,

respectively, for low-mass pre-stellar cores, class 0, and class I

stars. However, substantial variation in lifetime estimates from cloud

to cloud are observed. For example, Wilking et al. (1989) in

Ophiuchus and Kenyon et al. (1990) in the Taurus-Auriga region

measure for class I sources a lifetime of 2-

![]() yr and

yr and

![]() yr respectively. In Ophiuchus, André & Montmerle (1994) obtain

yr respectively. In Ophiuchus, André & Montmerle (1994) obtain

![]() -

-

![]() yr for class 0

and 105 yr for class I. In this framework, the NGC 6334-NGC 6357 protostellar phase lifetime (

yr for class 0

and 105 yr for class I. In this framework, the NGC 6334-NGC 6357 protostellar phase lifetime (

![]() yr) is similar to the typical

lifetime of nearby low-mass class 0 sources, but younger than that

of class I stars. This suggests high-mass stellar formation proceeds more rapidly than for low-mass stars.

yr) is similar to the typical

lifetime of nearby low-mass class 0 sources, but younger than that

of class I stars. This suggests high-mass stellar formation proceeds more rapidly than for low-mass stars.

A high-mass pre-stellar core can be defined as a starless clump with a size of

![]() 0.1 pc and a volume-averaged density of

0.1 pc and a volume-averaged density of ![]() 105 cm-3, which is gravitationally bound (Motte et al. 2007).