| Issue |

A&A

Volume 515, June 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A16 | |

| Number of page(s) | 18 | |

| Section | Catalogs and data | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200913236 | |

| Published online | 02 June 2010 | |

Photometric multi-site campaign on the open cluster NGC 884

I. Detection of the variable stars![[*]](/icons/foot_motif.png)

S. Saesen1,![]() - F. Carrier1,

- F. Carrier1,![]() - A. Pigulski2

- C. Aerts1,3 - G. Handler4

- A. Narwid2 -

J. N. Fu5 - C. Zhang5

- X. J. Jiang6 -

J. Vanautgaerden1 - G. Kopacki2

- M. Steslicki2 - B. Acke1,

- A. Pigulski2

- C. Aerts1,3 - G. Handler4

- A. Narwid2 -

J. N. Fu5 - C. Zhang5

- X. J. Jiang6 -

J. Vanautgaerden1 - G. Kopacki2

- M. Steslicki2 - B. Acke1,![]() - E. Poretti7 - K. Uytterhoeven7,8

- C. Gielen1 - R. Østensen1

- W. De Meester1 -

M. D. Reed9 - Z. Ko

- E. Poretti7 - K. Uytterhoeven7,8

- C. Gielen1 - R. Østensen1

- W. De Meester1 -

M. D. Reed9 - Z. Ko![]() aczkowski2

- G. Michalska2 - E. Schmidt4

- K. Yakut1,10,11 - A. Leitner4

- B. Kalomeni12 - M. Cherix13

- M. Spano13 - S. Prins1

- V. Van Helshoecht1 -

W. Zima1 - R. Huygen1

- B. Vandenbussche1 - P. Lenz4,14

- D. Ladjal1 -

E. Puga Antolín1 -

T. Verhoelst1,

aczkowski2

- G. Michalska2 - E. Schmidt4

- K. Yakut1,10,11 - A. Leitner4

- B. Kalomeni12 - M. Cherix13

- M. Spano13 - S. Prins1

- V. Van Helshoecht1 -

W. Zima1 - R. Huygen1

- B. Vandenbussche1 - P. Lenz4,14

- D. Ladjal1 -

E. Puga Antolín1 -

T. Verhoelst1,![]() - J. De Ridder1 -

P. Niarchos15 - A. Liakos15

- D. Lorenz4 - S. Dehaes1

- M. Reyniers1 - G. Davignon1

- S.-L. Kim16 -

D. H. Kim16 -

Y.-J. Lee16 - C.-U. Lee16

- J.-H. Kwon16 - E. Broeders1

- H. Van Winckel1 -

E. Vanhollebeke1 - C. Waelkens1

- G. Raskin1 - Y. Blom1

- J. R. Eggen9 -

P. Degroote1 - P. Beck4

- J. Puschnig4 -

L. Schmitzberger4 -

G. A. Gelven9 -

B. Steininger4 - J. Blommaert1

- R. Drummond1 - M. Briquet1,

- J. De Ridder1 -

P. Niarchos15 - A. Liakos15

- D. Lorenz4 - S. Dehaes1

- M. Reyniers1 - G. Davignon1

- S.-L. Kim16 -

D. H. Kim16 -

Y.-J. Lee16 - C.-U. Lee16

- J.-H. Kwon16 - E. Broeders1

- H. Van Winckel1 -

E. Vanhollebeke1 - C. Waelkens1

- G. Raskin1 - Y. Blom1

- J. R. Eggen9 -

P. Degroote1 - P. Beck4

- J. Puschnig4 -

L. Schmitzberger4 -

G. A. Gelven9 -

B. Steininger4 - J. Blommaert1

- R. Drummond1 - M. Briquet1,![]() - J. Debosscher1

- J. Debosscher1

1 - Instituut voor Sterrenkunde, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven,

Celestijnenlaan 200 D, 3001 Leuven, Belgium

2 - Instytut Astronomiczny Uniwersytetu Wroc![]() awskiego, Kopernika 11, 51-622 Wroc

awskiego, Kopernika 11, 51-622 Wroc![]() aw, Poland

aw, Poland

3 - Department of Astrophysics, Radboud University Nijmegen, PO Box

9010, 6500 GL Nijmegen, The Netherlands

4 - Institut für Astronomie, Universität Wien, Türkenschanzstrasse 17,

1180 Wien, Austria

5 - Department of Astronomy, Beijing Normal University, Beijing 100875,

PR China

6 - National Astronomical Observatories, Chinese Academy of Sciences,

Beijing 100012, PR China

7 - INAF - Osservatorio Astronomico di Brera, via Bianchi 46, 23807

Merate, Italy

8 - Laboratoire AIM, CEA/DSM-CNRS-Université Paris Diderot, CEA,

IRFU, SAp, Centre de Saclay, 91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France

9

- Department of Physics, Astronomy, & Materials Science,

Missouri

State University, 901 S. National, Springfield, MO 65897, USA

10 - Institute of Astronomy, University of Cambridge, Madingley Road,

Cambridge CB3 0HA, UK

11 - Department of Astronomy & Space Sciences, Ege University,

35100 Izmir, Turkey

12 - Izmir Institute of Technology, Department of Physics, 35430 Izmir,

Turkey

13 - Observatoire de Genève, Université de Genève, Chemin des

Maillettes 51, 1290 Sauverny, Switzerland

14 - Copernicus Astronomical Centre, Bartycka 18, 00-716 Warsaw, Poland

15

- Department of Astrophysics, Astronomy and Mechanics, National and

Kapodistrian University of Athens, Panepistimiopolis, 157 84 Zografos,

Athens, Greece

16 - Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute, Daejeon 305-348,

South Korea

Received 3 September 2009 / Accepted 9 December 2009

Abstract

Context. Recent progress in the seismic

interpretation of field ![]() Cep

stars has resulted in improvements of the physics in the stellar

structure and evolution models of massive stars. Further asteroseismic

constraints can be obtained from studying ensembles of stars in a young

open cluster, which all have similar age, distance and chemical

composition.

Cep

stars has resulted in improvements of the physics in the stellar

structure and evolution models of massive stars. Further asteroseismic

constraints can be obtained from studying ensembles of stars in a young

open cluster, which all have similar age, distance and chemical

composition.

Aims. To improve our comprehension of the ![]() Cep

stars, we studied the young open cluster NGC 884 to discover

new B-type pulsators, besides the two known

Cep

stars, we studied the young open cluster NGC 884 to discover

new B-type pulsators, besides the two known ![]() Cep stars, and other

variable stars.

Cep stars, and other

variable stars.

Methods. An extensive multi-site campaign was set up

to gather accurate CCD photometry time series in four

filters (U, B, V,

I)

of a field of NGC 884. Fifteen different instruments collected

almost 77 500 CCD images in 1286 h. The

images were

calibrated and reduced to transform the CCD frames into

interpretable differential light curves. Various variability indicators

and frequency analyses were applied to detect variable stars in the

field. Absolute photometry was taken to deduce some general cluster and

stellar properties.

Results. We achieved an accuracy for the brightest

stars of 5.7 mmag in V, 6.9 mmag

in B, 5.0 mmag in I

and 5.3 mmag in U. The noise level

in the amplitude spectra is 50 ![]() mag in the V band.

Our campaign confirms the previously known pulsators, and we report

more than one hundred new multi- and mono-periodic B-, A- and F-type

stars. Their interpretation in terms of classical instability domains

is not straightforward, pointing to imperfections in theoretical

instability computations. In addition, we have discovered six new

eclipsing binaries and four candidates as well as other irregular

variable stars in the observed field.

mag in the V band.

Our campaign confirms the previously known pulsators, and we report

more than one hundred new multi- and mono-periodic B-, A- and F-type

stars. Their interpretation in terms of classical instability domains

is not straightforward, pointing to imperfections in theoretical

instability computations. In addition, we have discovered six new

eclipsing binaries and four candidates as well as other irregular

variable stars in the observed field.

Key words: open clusters and associations: individual: NGC 884 - techniques: photometric - stars: variables: general - stars: oscillations - binaries: eclipsing

1 Introduction

The ![]() Cep

stars are a homogeneous group of B0-B3 stars whose pulsational

behaviour is interpreted in terms of the

Cep

stars are a homogeneous group of B0-B3 stars whose pulsational

behaviour is interpreted in terms of the ![]() mechanism activated

by the metal opacity bump. Given that mainly low-degree low-order

pressure (p-) and gravity (g-)

modes are excited, these stars are good potential targets for in-depth

seismic studies of the interior structure of massive stars.

mechanism activated

by the metal opacity bump. Given that mainly low-degree low-order

pressure (p-) and gravity (g-)

modes are excited, these stars are good potential targets for in-depth

seismic studies of the interior structure of massive stars.

The best-studied ![]() Cep

stars are V836 Cen (Aerts

et al. 2003),

Cep

stars are V836 Cen (Aerts

et al. 2003), ![]() Eridani (Pamyatnykh et al. 2004; Dziembowski

& Pamyatnykh 2008; Ausseloos et al. 2004,

and references given in these papers),

Eridani (Pamyatnykh et al. 2004; Dziembowski

& Pamyatnykh 2008; Ausseloos et al. 2004,

and references given in these papers), ![]() Ophiuchi (Handler

et al. 2005; Briquet et al. 2007,2005),

12 Lacertae (Desmet

et al. 2009; Dziembowski & Pamyatnykh 2008;

Handler

et al. 2006),

Ophiuchi (Handler

et al. 2005; Briquet et al. 2007,2005),

12 Lacertae (Desmet

et al. 2009; Dziembowski & Pamyatnykh 2008;

Handler

et al. 2006), ![]() Canis Majoris (Mazumdar et al. 2006) and

Canis Majoris (Mazumdar et al. 2006) and

![]() Peg

(Handler et al. 2009).

The detailed seismic analysis of these selected stars led to several

new insights into their internal physics. Non-rigid rotation and core

convective overshoot are needed to explain the observed pulsation

frequencies. Moreover, for some of the observed modes of

Peg

(Handler et al. 2009).

The detailed seismic analysis of these selected stars led to several

new insights into their internal physics. Non-rigid rotation and core

convective overshoot are needed to explain the observed pulsation

frequencies. Moreover, for some of the observed modes of ![]() Eridani

and 12 Lacertae excitation problems were encountered (Daszynska-Daszkiewicz et al. 2005).

Eridani

and 12 Lacertae excitation problems were encountered (Daszynska-Daszkiewicz et al. 2005).

The next challenging step in the asteroseismology of ![]() Cep

stars is to measure those stars with much higher signal-to-noise from

space (e.g., Degroote

et al. 2009b)

and to study them in

clusters. Obviously, we would greatly benefit from the fact that the

cluster members have a common origin and formation, implying much

tighter constraints when modelling their observed pulsation behaviour.

Furthermore, clusters are ideally suited for gathering

CCD photometry, providing high-accuracy measurements for

thousands

of stars simultaneously.

Cep

stars is to measure those stars with much higher signal-to-noise from

space (e.g., Degroote

et al. 2009b)

and to study them in

clusters. Obviously, we would greatly benefit from the fact that the

cluster members have a common origin and formation, implying much

tighter constraints when modelling their observed pulsation behaviour.

Furthermore, clusters are ideally suited for gathering

CCD photometry, providing high-accuracy measurements for

thousands

of stars simultaneously.

Three clusters were initially selected for this purpose:

one southern cluster, NGC 3293, which contains eleven

known ![]() Cep

stars (Balona 1994), and

two northern clusters, NGC 6910 and NGC 884, which

contain four and two bona fide

Cep

stars (Balona 1994), and

two northern clusters, NGC 6910 and NGC 884, which

contain four and two bona fide ![]() Cep stars,

respectively (Koaczkowski

et al. 2004; Krzesinski & Pigulski 1997).

Preliminary results for these multi-site cluster campaigns can be found

in Handler

et al. (2007,2008) for NGC 3293, in Pigulski et al. (2007)

and Pigulski (2008) for

NGC 6910 and in Pigulski

et al. (2007) and Saesen et al. (2009,2008)

for NGC 884. In these preliminary reports, the discovery of

some new

Cep stars,

respectively (Koaczkowski

et al. 2004; Krzesinski & Pigulski 1997).

Preliminary results for these multi-site cluster campaigns can be found

in Handler

et al. (2007,2008) for NGC 3293, in Pigulski et al. (2007)

and Pigulski (2008) for

NGC 6910 and in Pigulski

et al. (2007) and Saesen et al. (2009,2008)

for NGC 884. In these preliminary reports, the discovery of

some new ![]() Cep

and other variable stars was already announced.

Cep

and other variable stars was already announced.

This paper deals with the detailed analysis of NGC 884 and is the first in a series on this subject, presenting our data set and discussing the general variability in this cluster.

2 The target cluster NGC 884

NGC 884 (![]() Persei,

Persei,

![]() ,

,

![]() )

is a rich young open cluster located in the Perseus constellation.

Together with NGC 869 (h Persei) it forms the Perseus

double

cluster, which is well documented in the literature.

)

is a rich young open cluster located in the Perseus constellation.

Together with NGC 869 (h Persei) it forms the Perseus

double

cluster, which is well documented in the literature.

The possible co-evolution of both clusters puzzled many

researchers. Some claim that h and ![]() Persei have the same distance modulus

and age, others state that h Persei is closer and younger than

Persei have the same distance modulus

and age, others state that h Persei is closer and younger than

![]() Persei.

For an extensive overview of the photographic, photo-electric and

photometric studies on the co-evolution of the two clusters based on

the age, reddening and distance

moduli, we refer to Southworth

et al. (2004a). They conclude that the most recent

studies (Keller

et al. 2001; Slesnick et al. 2002; Marco &

Bernabeu 2001; Capilla & Fabregat 2002)

converge towards an identical distance modulus of 11.7

Persei.

For an extensive overview of the photographic, photo-electric and

photometric studies on the co-evolution of the two clusters based on

the age, reddening and distance

moduli, we refer to Southworth

et al. (2004a). They conclude that the most recent

studies (Keller

et al. 2001; Slesnick et al. 2002; Marco &

Bernabeu 2001; Capilla & Fabregat 2002)

converge towards an identical distance modulus of 11.7 ![]() 0.05 mag and a log (age/yr) of 7.10

0.05 mag and a log (age/yr) of 7.10 ![]() 0.01 dex. The average reddening of

0.01 dex. The average reddening of ![]() Persei amounts to

E(B-V)=0.56

Persei amounts to

E(B-V)=0.56 ![]() 0.05.

0.05.

Slettebak (1968)

collected rotational

velocities for luminous B giant stars located in the vicinity

of

the double cluster. He reports that the measured stellar rotation

velocities are about 50% higher than for field counterparts,

supported by his observation of an unusual high number of

Be stars in the clusters. More recent projected rotational

velocity measurements of Strom

et al. (2005) confirm that the B stars

in h and ![]() Persei

rotate on average faster than field stars of similar mass and age. More

searches for and studies of Be stars in the clusters have been

carried out, leading to the detection of 20 Be stars

in

Persei

rotate on average faster than field stars of similar mass and age. More

searches for and studies of Be stars in the clusters have been

carried out, leading to the detection of 20 Be stars

in ![]() Persei

(see Malchenko & Tarasov 2008,

and references therein).

Persei

(see Malchenko & Tarasov 2008,

and references therein).

The first variability search in the cluster NGC 884

was conducted by Percy (1972)

in the extreme nucleus of the cluster by means of photo-electric

measurements. He identified three candidate variable stars on a time

scale longer than ten hours, Oo 2088, Oo 2227 and

Oo 2262 (Oosterhoff numbers, see Oosterhoff

1937), and one on a shorter time scale of six hours,

Oo 2299. Waelkens

et al. (1990)

set up a photometric campaign spanning eight years. They report that at

least half of the brighter stars are variable and that most of them

seem to be Be stars. The time sampling of both data sets was

not

suitable to search for ![]() Cep

stars. The campaign

and analysis by Krzesinski &

Pigulski (1997)

yielded more detailed results. Based on a photometric

CCD search

in the central region of NGC 884, they discovered two

Cep

stars. The campaign

and analysis by Krzesinski &

Pigulski (1997)

yielded more detailed results. Based on a photometric

CCD search

in the central region of NGC 884, they discovered two ![]() Cep

stars, Oo 2246 and Oo 2299, showing two and one

pulsation

frequencies, respectively. Furthermore, nine other variables were

found: two eclipsing binaries (Oo 2301,

Oo 2311), three

Be stars (Oo 2088, Oo 2165,

Oo 2242), two

supergiants (Oo 2227, Oo 2417), possibly one

ellipsoidal

binary (Oo 2371), and one variable star of unknown nature

(Oo 2140). Afterwards, a larger cluster field was studied by Krzesinski (1998) and

Krzesinski & Pigulski (2000),

each of them leading to one more

Cep

stars, Oo 2246 and Oo 2299, showing two and one

pulsation

frequencies, respectively. Furthermore, nine other variables were

found: two eclipsing binaries (Oo 2301,

Oo 2311), three

Be stars (Oo 2088, Oo 2165,

Oo 2242), two

supergiants (Oo 2227, Oo 2417), possibly one

ellipsoidal

binary (Oo 2371), and one variable star of unknown nature

(Oo 2140). Afterwards, a larger cluster field was studied by Krzesinski (1998) and

Krzesinski & Pigulski (2000),

each of them leading to one more ![]() Cep candidate:

Oo 2444 and Oo 2809, but the data sets were

insufficient to

confirm their pulsational character. Finally, two papers prior to our

study are devoted to binaries: Southworth

et al. (2004b) investigated the eclipsing binary

Oo 2311 in detail and Malchenko

(2007)

the ellipsoidal variable Oo 2371. Given the

occurrence of

several variables as well as at least one eclipsing binary, we judged

Cep candidate:

Oo 2444 and Oo 2809, but the data sets were

insufficient to

confirm their pulsational character. Finally, two papers prior to our

study are devoted to binaries: Southworth

et al. (2004b) investigated the eclipsing binary

Oo 2311 in detail and Malchenko

(2007)

the ellipsoidal variable Oo 2371. Given the

occurrence of

several variables as well as at least one eclipsing binary, we judged ![]() Persei

to be well suited for our asteroseismology project.

Persei

to be well suited for our asteroseismology project.

3 Equipment and observations

In 2005, a multi-site campaign was set up to gather differential

time-resolved multi-colour CCD photometry of a field of the

cluster NGC 884 that contains the two previously known ![]() Cep

stars. The goal was to collect accurate measurements with a long time

base to make the detection of pulsation frequencies at milli-magnitude

level possible for a large number of cluster stars of the spectral

type B. The observations were taken in different filters to be

able to identify their modes.

Cep

stars. The goal was to collect accurate measurements with a long time

base to make the detection of pulsation frequencies at milli-magnitude

level possible for a large number of cluster stars of the spectral

type B. The observations were taken in different filters to be

able to identify their modes.

The entire campaign spanned 800 days spread over

three

observation seasons. During the first season

(August 2005-March 2006), four telescopes assembled

250 h of data. The main campaign took place in the second

season

(July 2006-March 2007), when nine more telescopes

joined the

project and gathered 940 h of measurements. In the third

season

(July 2007-October 2007), only the two dedicated

telescopes,

the 120-cm Mercator telescope at Observatorio del Roque de los

Muchachos (ORM) and the 60-cm at Bia![]() ków

Observatory, observed NGC 884 for 100 more hours.

In total, an international team consisting of

61 observers used 15 different instruments attached

to

13 telescopes to collect almost

77 500 CCD images

in the UBVI filters and 92 h of

photo-electric data in the ubvy and

UB1BB2V1VG filters.

ków

Observatory, observed NGC 884 for 100 more hours.

In total, an international team consisting of

61 observers used 15 different instruments attached

to

13 telescopes to collect almost

77 500 CCD images

in the UBVI filters and 92 h of

photo-electric data in the ubvy and

UB1BB2V1VG filters.

In Table 1,

an

overview of the different observing sites with their equipment

(telescope, instrument characteristics and filters) is given. Almost

all sites used CCD cameras, only Observatorio Astronómico

Nacional

de San Pedro Mártir (OAN-SPM) and ORM made use of photometers.

Simultaneous Strömgren ![]() and Geneva UB1BB2V1VG measurements

of (suspected)

and Geneva UB1BB2V1VG measurements

of (suspected) ![]() Cep

stars were collected using the Danish photometer at OAN-SPM and the

P7 photometer at ORM respectively. For both photometers,

a suitable diaphragm was used to measure the target star only

each

time. At ORM the photometer was only used from September until

October 2006, when technical problems with the Merope CCD were

encountered. The precision

of the photo-electric photometry reaches 2.5 mmag at OAN-SPM

and

10 mmag at ORM.

Cep

stars were collected using the Danish photometer at OAN-SPM and the

P7 photometer at ORM respectively. For both photometers,

a suitable diaphragm was used to measure the target star only

each

time. At ORM the photometer was only used from September until

October 2006, when technical problems with the Merope CCD were

encountered. The precision

of the photo-electric photometry reaches 2.5 mmag at OAN-SPM

and

10 mmag at ORM.

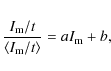

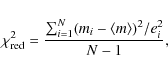

Figure 1

displays

an image with the largest field of view (FOV) of NGC 884

covered

by our campaign, denoting the FOVs of all other sites. Since the FOV at

ORM was so small, two fields of NGC 884 were observed

alternating

during the second and third season to cover all the ![]() Cep

stars known at that time. A world map indicating all the

observatories can be found in Saesen

et al. (2008).

The spread in longitude of the different sites helps to avoid daily

alias confusion in the frequency analysis. The effectiveness of this

approach is described in Saesen

et al. (2009).

Cep

stars known at that time. A world map indicating all the

observatories can be found in Saesen

et al. (2008).

The spread in longitude of the different sites helps to avoid daily

alias confusion in the frequency analysis. The effectiveness of this

approach is described in Saesen

et al. (2009).

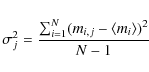

The distribution of the data in time per observing site is

shown in Fig. 2,

while Table 2

contains a summary of the observations. The noted precision indicates

the mean standard deviation of the final light curves of ten bright

stars with sufficient observations. For ORM, the first number

is

for the first season and the second number for the second and third

season, when another pointing was used. The column with

![]() denotes

the noise in the amplitude spectrum of the V light

curve and is calculated as

denotes

the noise in the amplitude spectrum of the V light

curve and is calculated as

![]() =

=

![]() ,

with

,

with

![]() the precision in the V filter

and NV

the number of V frames.

This is a measure of the relative importance of a certain site to the

frequency resolution. It can be deduced that the data from the

Bia

the precision in the V filter

and NV

the number of V frames.

This is a measure of the relative importance of a certain site to the

frequency resolution. It can be deduced that the data from the

Bia![]() ków and

Xinglong observatories are the most significant.

ków and

Xinglong observatories are the most significant.

The observing strategy was the same for all sites: exposure times were adjusted according to the observing conditions to optimise the signal-to-noise for the known B-type stars, while avoiding saturation and non-linear effects of the camera. The images were preferably taken in focus and with autoguider if present, to keep the star's image sharp to avoid contamination or confusion in the observed half-crowded field. V was the main filter, and where possible, also B, I and sometimes U were used. The observations could be taken also during nautical night, as long as the airmass of NGC 884 was below 2.5. A considerable amount of calibration frames was asked for as we were attempting precise measurements. Their description and analysis is discussed in the next section.

Table 1: Observing sites and equipment.

Table 2: Observations summary.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{13236_frame.ps} %

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13236-09/Timg35.png)

|

Figure 1:

Image of NGC 884 with the largest FOV (26 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| Figure 2: Distribution of the data in time per observing site. The list of observatories from top to bottom goes from west to east. |

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

4 Calibrations

In general, the calibration of the CCD images consisted of bias and dark subtraction, flat fielding and in some cases non-linearity and shutter corrections. They were mostly performed in standard ways and are described in more detail in the sections below.

4.1 Bias and dark subtraction

The first step in removing the bias from all images was subtracting the mean level of the overscan region, if available, and trimming this region. This corrected for the average signal introduced by reading the CCD. We tested the relation between this average overscan level and the average bias frame level. Only for one site (ORM) there was a linear dependence which we removed, for all other sites the difference was just a constant offset. After subtracting the overscan level, we corrected for the residual bias pattern, the pixel-to-pixel structure in the read noise on an image. This was mostly done on a nightly basis by taking the mean of several bias frames minus their overscan level (a so-called master bias), which was then subtracted from all other images (darks, flat fields, science frames).

What remained in the dark frames is the thermal noise, characteristic of the CCD's temperature and exposure time. We constructed a suitable master dark by averaging darks per night and with appropriate duration, and subtracted it to neutralise this effect. The CCDs were temperature controlled so as to keep the dark flux constant, and at several sites its value was even negligible due to the efficient strong cooling of the chip.

4.2 Non-linearity correction

The CCD gain can deviate from a perfectly linear reponse, especially for fluxes close to the saturation limit. Since several target stars are bright, we could end up in this non-linear regime. For CCDs where this effect was known, we kept the signal below the level where the non-linearity commences. For unexplored CCDs, we made linearity tests which consisted of flat fields with different exposure times. In most cases, a dome lamp was used with an adjusted intensity so that saturation occurred on a 30-s exposure. A flat-field sequence was then composed of 1-3, ..., 30 s exposures taken at a random order. In order to reduce uncertainties, at least four such sequences were made to average out the results. Reference images to check the stability of the light source were also collected, but the erratic order of exposure times also helped to mitigate any systematics in the lamp intensity.

As an example we describe here the analysis of the non-linear

response of the CCD at OFXB and its correction procedure. The values we

use in this description are averaged over the whole image.

In the

perfect case, the flux rate on the CCD would be constant

with

with

By further investigation of the linearity tests with corrected fluxes, we noticed a remaining spatial dependent effect that could not be attributed to the shutter (see Sect. 4.3). This was caused by a smooth pixel-to-pixel variation of the coefficients a and b in the fitted linear relation, which we did not account for. Therefore, the linearity correction was performed for every pixel separately, which improved the photometry by a factor of ten.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{13236_lintest.eps} %

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13236-09/Timg43.png)

|

Figure 3: Linearity test for the CCD of a) OFXB b) Michelbach c) SOAO and d) Vienna. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Three other cameras also reacted in a non-linear way: the ones at Michelbach Observatory and SOAO show the same discrepancy as OFXB, and the CCD at Vienna Observatory exhibits a higher order effect, but only at low fluxes. We corrected for all these CCD effects.

4.3 Shutter correction

Since the exposure times at the 1.2-m Mercator telescope (ORM) were short, we corrected the images for the shutter effect. As a mechanical shutter needs time to open and close, some regions in the CCD are exposed longer or shorter depending on their position. To quantify and correct for this unwanted effect, we took a similar series of flat fields as needed for the linearity test, only this time with shorter exposure times. If we divided one very short exposure, where the shutter opening and closing time plays an important role by one of the longer exposures, where the shutter effect is negligible, we could actually nicely see the blades of the shutter (see Fig. 4).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=5cm,clip]{13236_shutter.eps} %

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13236-09/Timg44.png)

|

Figure 4:

Image showing the calculated |

| Open with DEXTER | |

To measure this effect, we handled the problem in the same way as

before, only this time the flux rate was not the variable

parameter, but the exposure time. In the perfect case, the

flux

measured in a given pixel would be

with F again the constant flux rate and t the exposure time. Since at that pixel we have a slightly longer exposure time

By making a linear least-squares fit between this measured flux and the exposure time of the shutter test sequence, we hence obtained the

For all other observing sites except SOAO, the shutter effect was negligible or we could not quantify the effect because of a lack of calibration frames. For SOAO, the correction of the shutter effect was calculated and corrected for in the same way as described above.

4.4 Flat fielding

The final correction applied to the CCD images is flat fielding. It corrects for the pixel-to-pixel sensitivity variations. For every filter and every night, we created a master flat by scaling the flat fields to the normalised level of 1 and taking the mean image while rejecting the extreme values, after checking the flat field's stability by division of one flat by another. Finally the flat field correction was made by dividing the image to be corrected by the master flat. If possible, we took sky flats without tracking (possible stars in the field would then not fall on the same pixels), otherwise dome flats were used. Sometimes we noticed a small difference between dusk and dawn flat fields due to the telescope position. But since we did not dispose of the appropriate calibration frames to correct for it, we took a nightly average. Regions with vignetting on the CCD were trimmed off.

At some observatories, the read-out time of the CCD was very long, so that it was impossible to gather a sufficient number of flat fields in every observed filter per night. In that case, we checked over which time period the flats were stable and combined them together over several nights to construct a master flat. ORM was such an observatory, but the flats from July and August 2006 were not at all stable, caused by the installation of a heat shield in the nitrogen dewar. The flat field change was even noticeable between dusk and dawn and is spatially dependent. Therefore we made a polynomial fit over time for every pixel to interpolate the measured flux variation to gain appropriate flats throughout the night.

5 Reduction to differential light curves

The following sections report on the reduction from the calibrated CCD images to differential light curves, which was conducted for each observatory individually (Sects. 5.1-5.4) and the merging of the data of all sites (Sect. 5.5). The reduction method for the photo-electric data taken at ORM with P7 is described in Rufener (1985,1964). For the reduction of the photo-electric measurements of OAN-SPM, we refer to Poretti & Zerbi (1993) and references therein.

5.1 Flux extraction with Daophot

To extract the magnitudes of the different stars on the frames, we used the DAOPHOT II (Stetson 1987) and ALLSTAR (Stetson & Harris 1988) packages.

As a first step we made an extensive master list of 3165 stars in our total field of view by means of a deep and large frame with the best seeing. For this purpose, we utilised the subroutines FIND and PHOT to search for stars and compute their aperture photometry. Although DAOPHOT handles e.g. pixel defects and cosmic rays, the image was checked to reject false star detections. Then we performed profile photometry. The point-spread function (PSF) consisted of an analytical function (appropriate for the instrument, see Table 2) and an empirical table to adapt the PSF in the best way to the image. In general we allowed this function to vary quadratically over the field. Sufficient PSF stars were chosen with PICK for the derivation of the profile shape with the PS subroutine. Subsequently an iterative process was followed to refine this PSF by subtracting neighbouring stars with the calculated profile by ALLSTAR and generating a new PSF with less blended stars until the PSF converged. At last, ALLSTAR fitted all field stars to achieve the best determined CCD coordinates of each star and to obtain their magnitudes. In the end we subtracted all stars in the frame and inspected the resulting image visually. If we could detect any other stars not contained in our master list, we performed the described procedure again on the subtracted image to include them. In addition, a PSF star list was created by selecting isolated and bright stars uniformly spread over the image. The point-spread function calculation was based on these stars instead of further applying the PICK routine.

To convert the star list from one instrument to another, we made a cubic bivariate polynomial transformation of the CCD coordinates X and Y, based on the coordinates of 20 manually cross-identified stars that are well spread over the field. In this way, we obtained a master star list for each CCD. In order to convert an instrument star list of a certain site to each frame, taking only a shift and small rotation into account was sufficient. To do so, we searched for two pre-selected, well-separated, bright but not saturated stars on the image. As a consequence, the strategy to derive the profile photometry as described above could be automated and was used for the fainter stars. This PSF photometry also had the advantage to provide a precise measure of the FWHM (full-width at half-maximum) of the stars, of the mean sky brightness and of the position of the stars in the field.

For the brightest stars, aperture photometry yielded the most precise results. As in our cluster some stars overlap others, we used the routine NEDA to first subtract neighbour stars PSF-wise before determining the aperture photometry. Multiple apertures ranging from 1 until 4 FWHM in steps of 0.25 FWHM and several background radii were tested for every instrument, the one with the most accurate outcome was applied. We tested that using the same aperture for every star yielded best results and so no further correction is needed since the same amount of light is measured for every star.

Some instruments and telescopes dealt with technical problems resulting in distorted images, and sometimes there was bad tracking during the observations. Sporadically, condensation on the cameras occurred and glows were apparent on the images. The weather was not always ideal either. If the images looked really bad, the automatic reduction procedure failed. If the reduction procedure succeeded, but the resulting photometry was inaccurate or inconsistent, the measurements were rejected in the following stage in which we calculated the differential photometry.

5.2 Multi-differential photometry

Our aim was to quantify the relative light variations of the measured stars with high precision. In this view, multi-differential photometry, which takes advantage of the ensemble of stars in our field of view, is exactly what we needed. Comparing each star with a set of reference stars indeed reduced the effects of extinction, instrumental drifts and other non-stellar noise sources if their fluctuations in time were consistent over the full frame, but it would still contain the variability information we searched for.

For each instrument we applied an iterative algorithm to compute this relative photometry. In an outer loop, the set of reference stars was iteratively optimised, whereas in an inner loop, the light curve for a given set of reference stars was improved. As a starting point, an initial set of reference stars was extracted from a fixed list of bright stars.

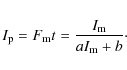

The inner loop of the iteration consisted in adapting the

light

curve of the reference stars to gain new mean and smaller standard

deviation estimates. In the first three iterations,

the zero

point for image j was calculated as the

mean of the variation of the reference stars

with

where

In the outer loop, the differential magnitudes mc,j

of all stars were computed as

with mm,j the DAOPHOT magnitude of image j and

On average, the final differential photometry was based on 25 reference stars. Images with poor results, where the photometry of the final set of reference stars was used as benchmark, were eliminated at the end. Often this represented 6 to 10% of the total amount of data, but it strongly depended on the instrument.

As a consequence of our choice for bright comparison stars, our approach is optimised for B-type cluster members since they have similar magnitudes and colours as the reference stars. Other stars are typically much fainter, so that their photon noise dominates the uncertainties of the magnitudes.

To improve the overall quality of the data, we removed some outliers with sigma clipping. We used an iterative loop which stops after points were no longer rejected. However, we never discarded several successive measurements as these could originate from an eclipse. Normally the programme converged after a few iterations. The data of the Vienna Observatory (V filter only), Baker Observatory and TUG (T40) were completely rejected since their precision was inferior to the other sites or their photometry was unreliable due to technical problems.

5.3 Error determination

As can be noticed in Table 2, we were dealing with a diverse data set concerning the accuracy. To improve the signal-to-noise (S/N) level in a frequency analysis, it was therefore essential to weight the time series (Handler 2003). In order to have appropriate weights, we aimed at getting error estimates per data point which were as realistic as possible. They had to reflect the quality of the measurements in a time series of a certain instrument and at the same time be intercomparable for the different inhomogenous data sets.

In general it is not easy to make a whole picture of the total error budget. The error derivation of DAOPHOT accounts for the readout noise, photon noise, the flat-fielding error and the interpolation error caused by calculating the aperture and PSF photometry. Besides these, there is also scintillation noise, noise caused by the zero point computation by means of the comparison stars and other CCD-related noise sources depending on the colour of the stars, their position etc. Some analytical expressions to evaluate the most important noise sources are available in the literature (e.g., Kjeldsen & Frandsen 1992).

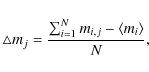

We preferred to work empirically and determined an error

approximation

together with the relative photometry. We assumed that the standard

deviation of the contribution of each reference star to the calculated

zero point of a certain image j

contained all noise sources. For the bright stars, which have a photon noise comparable to the photon noise of the reference stars, we can use this value directly as the noise estimate of image j since

where

We verified if this indeed corresponded to the intercomparable

error

determination we searched for. To this end, we used

the

relation between the noise in the time domain

![]() ,

i.e., the mean measured error of the star computed by us, and the noise

in the frequency domain

,

i.e., the mean measured error of the star computed by us, and the noise

in the frequency domain

![]() ,

i.e., the amplitude noise in the periodogram, for a given

star i, given by

,

i.e., the amplitude noise in the periodogram, for a given

star i, given by

with N the number of measurements of star i. We checked this correlation for the brightest 300 stars in the field. An example for Bia

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13236_errcomp.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13236-09/Timg60.png)

|

Figure 5:

Comparison of the mean measured error

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

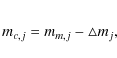

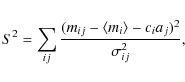

5.4 Detrending

Even after taking differential photometry, residual trends can

still

exist in the light curves, e.g. due to instrumental drifts or

changes in the atmospheric transparency. As we were also

interested in low frequencies, where the residual trends will cause

high noise levels, we wanted to correct the time series for these

trends. In order to do so, we applied the Sys-Rem algorithm by

Tamuz et al. (2005),

which was specifically

developped to remove correlated noise by searching for linear

systematic effects that are present in the data of a lot of stars. The

algorithm minimises the global expression

where mij and

Sys-Rem used the error on the measurements to downweigh bad measurements. However, we noticed that including faint stars in the sample to also correct bright stars degrades the photometric results of the latter. Hence we only used the whole set of stars to ameliorate the data of the faintest stars, and we used a sub-sample of bright stars for the application of Sys-Rem to the brightest ones. Stars showing clear long-term variability were also excluded from the sample.

The number of effects to be removed is a free parameter in the

algorithm and should be handled with care. Indeed, we wanted to

eliminate as many instrumental trends as possible, but certainly no

stellar variability. For every instrument we examined the periodograms

averaged for the 100 and 300 brightest stars to

evaluate when

sufficient trends are taken out the data. At the same time the

periodograms of the known ![]() Cep stars

were inspected to make sure the known stellar variability was not

affected. An example for Bia

Cep stars

were inspected to make sure the known stellar variability was not

affected. An example for Bia![]() ków Observatory is shown in Fig. 6,

and it can be clearly seen that the accuracy improved.

In most cases, up to three linear systematic effects

were

removed.

ków Observatory is shown in Fig. 6,

and it can be clearly seen that the accuracy improved.

In most cases, up to three linear systematic effects

were

removed.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{13236_sysrem.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13236-09/Timg63.png)

|

Figure 6:

Periodogram examples from Biaków Observatory to show the impact

of Sys-Rem. a) The average periodogram of

the 300 brightest stars in the field, left:

without detrending, right: with three effects

removed. b) Idem for the known |

| Open with DEXTER | |

5.5 Merging

At this point the individual time series were fully processed and could be joined per filter (U, B, V, I). No phase shifts nor amplitude variations were expected for the data of the various sites for the oscillating B-stars and so only a magnitude shift, which can depend on the star, was computed.

To determine this magnitude shift, we made use of overlapping

observation periods. We started with data from Bia![]() ków

Observatory, which holds the most accurate measurements, and added the

other instruments one by one, beginning with the site that had the most

intervals in common. We smoothed the light curves and interpolated the

data points before calculating the mean shift to account for variations

in the time series. If no measurements were taken at

the same

time, the light curves were just shifted by matching their mean values.

ków

Observatory, which holds the most accurate measurements, and added the

other instruments one by one, beginning with the site that had the most

intervals in common. We smoothed the light curves and interpolated the

data points before calculating the mean shift to account for variations

in the time series. If no measurements were taken at

the same

time, the light curves were just shifted by matching their mean values.

6 Time-series analysis

To obtain the final light curves, the merged data sets were once more sigma-clipped and detrended with Sys-Rem. The final precision for the brightest stars is 5.7 mmag in V, 6.9 mmag in B, 5.0 mmag in I and 5.3 mmag in U. We also eliminated the light curves of about 25% of the stars, since those stars were poorly measured.

Given the better precision in the V filter and the overwhelming number of data points, the search for variable stars and an automated frequency analysis were carried out in this filter. The U-, B-, and I-filter data will be used in subsequent papers which will present a more detailed frequency analysis of the pulsating stars and eclipsing binaries found in our data.

6.1 Detection of variable stars

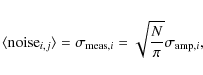

The following four tools were used to search for variability, whether

periodic or not. First, the standard deviation of the light

curve

gave an impression of the intrinsic variability. However, also the mean

magnitude of the star had to be considered, so that the bright

variable stars with low

amplitudes were selected and not the faint constant stars.

To take

the brightness of the star into account, we calculated the ``relative

standard deviation'' of the light curve, i.e.,

![]() ,

where

,

where ![]() is

the moving average of the bulk of (constant) stars over their

magnitude, as denoted by the grey line in Fig. 7a.

is

the moving average of the bulk of (constant) stars over their

magnitude, as denoted by the grey line in Fig. 7a.

The Abbé test gave another indication of variability.

It depends on the point-to-point variations and is sensible to

the

derivative of the light curve. For a particular star, its

value

was calculated as

where the sum is taken over the different data points. The value of the Abbé test is close to one for constant stars, larger than one for stars that are variable on shorter time scales than the characteristic sampling of the light curve and significantly smaller than one for variability on longer time scales.

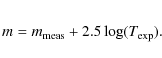

We also determined the reduced ![]() of the light curves

of the light curves

where N is the number of measurements and ei is the error on the magnitude mi, as calculated in Sect. 5.3. Its value expresses to what extent the light curve can be considered to have a constant value, the mean magnitude, and so whether there is or not noticeable variability above the noise level. Diagrams of these four indicators (

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.8cm,clip]{13236_vartest.eps}\vspace*{-3mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13236-09/Timg70.png)

|

Figure 7:

Different diagnostics to detect variability: a) the

standard deviation of the light curve, b) the

relative standard deviation, c) the Abbé

test and

d) the reduced |

| Open with DEXTER | |

A powerful tool to detect periodic variability is frequency analysis. For every star, weighted Lomb-Scargle diagrams (see Sect. 6.2) were calculated from 0 to 50 d-1. As this method assumes sinusoidal variations, phase dispersion minimisation diagrams (Stellingwerf 1978) were computed as well. In these periodograms we searched for significant frequency peaks.

In addition, we searched for variable stars by applying the automated classification software by Debosscher et al. (2007). This code was developed primarily for space data (Debosscher et al. 2009), but was previously also applied to the OGLE database of variables (Sarro et al. 2009).

Furthermore, also visual inspection of the light curves ranging over a couple to tens of days gives a strong indication of variability, especially for the brighter stars. After exploring the different diagnostics for variable star detection, we ended up with a list of about 400 stars that were selected for further analysis.

6.2 Frequency analysis

As a consequence of the large number of (candidate) variable stars, we applied an automatic procedure for the frequency analysis of the V data, which is a common procedure adopted in the classification of variable star work when treating numerous stars (e.g., Debosscher et al. 2009). This approach cannot be optimal for each individual case, and the results have to be regarded in this way. We thus limit ourselves to report on the dominant frequency only in this work (see Table A.1), even though numerous variables are multi-periodic. An optimal and detailed frequency analysis of the multi-periodic pulsators in the cluster will be the subject of a subsequent paper. For a discussion on the spectral window of the data, we refer to Saesen et al. (2009).

Due to changes in observing conditions and instrumentation with different inherent noise levels, there was a large variation in the data quality of the light curve. Following Handler (2003), it was therefore crucial to apply weights when periodograms were computed to suppress bad measurements and enhance the best observing sites. Accordingly, we used the generalised Lomb-Scargle periodogram of Zechmeister & Kürster (2009), where we gave each data point a weight inversely proportional to the square of the error of the measurement: wi=1/ei2. Moreover, this method takes also a floating mean into account besides the harmonic terms in sine and cosine when calculating the Lomb-Scargle fit (Lomb 1976; Scargle 1982). The spectra were computed from 0 d-1 to 50 d-1 in steps of 1/5T, where T is the total time span of the light curve.

In these periodograms, a frequency peak was considered as

significant

when its amplitude was above four times the noise level, i.e.,

a signal-to-noise ratio greater than 4.0 in amplitude

(Breger et al. 1993).

The noise at a certain frequency was calculated as the mean amplitude

of the

subsequent periodogram, i.e., the periodogram of the data prewhitened

for the suspected frequency. The interval over which we evaluated the

average changed according to the frequency value to account for the

increasing noise at lower frequencies: we used an interval of

1 d-1 for

![]() d-1,

of 1.9 d-1 for

d-1,

of 1.9 d-1 for

![]() d-1,

of 3.9 d-1 for

d-1,

of 3.9 d-1 for

![]() d-1

and of 5 d-1 for

d-1

and of 5 d-1 for

![]() d-1.

d-1.

Our strategy for the automatic computations was the following: subsequent frequencies were found by the standard procedure of prewhitening. In up to ten steps of prewhitening, the frequency with the highest amplitude was selected regardless of its S/N, as long as the periodogram contained at least one significant peak. In this way, also residual trends, characterised by low frequencies, and their alias frequencies were removed from the data set, and thus a lower noise level was reached. Starting from the 11th periodogram, peaks with the highest signal-to-noise level were selected. The calculations were stopped once no more significant peaks (S/N > 4) were present in the periodogram. We did not perform an optimisation of the frequency value due to the large calculation time and the excessive number of variables. This can, however, induce the effect of finding almost the same frequency value again after prewhitening.

Since some light curves were not perfectly merged, we adopted

the routine described above, excluding frequencies f=n ![]()

![]() with

with

![]() .

A constant magnitude shift was calculated to put the residuals

of

the different observing sites at the same

mean level, and this shift was then applied to the original data. Then

we repeated this process, now allowing all frequencies. After one more

frequency search, the residuals were sigma-clipped and a last frequency

analysis was carried out.

.

A constant magnitude shift was calculated to put the residuals

of

the different observing sites at the same

mean level, and this shift was then applied to the original data. Then

we repeated this process, now allowing all frequencies. After one more

frequency search, the residuals were sigma-clipped and a last frequency

analysis was carried out.

The results of this period investigation, which was carried out in the best way we could for an automated analysis, are described from Sect. 8 onward. Frequency values that will be used for stellar modelling need to be derived from a detailed, manual and multi-colour analysis of the 185 variable stars, where the frequency derivation schemes will be optimised according to the pulsator type. This will be presented in subsequent papers for the pulsators.

7 Absolute photometry

Absolute photometry of a cluster is a powerful tool to simultaneously determine general cluster parameters like the distance, reddening and age, and stellar parameters for the cluster members like their spectral type and position in the HR diagram. As pointed out in Sect. 2, NGC 884 is a well-studied cluster, but we wanted to take a homogeneous and independent data set of the observed field. As these observations were not directly part of the multi-site campaign, we describe them explicitly together with the specific data reduction and the determination of the cluster parameters. The stellar parameters like cluster membership, effective temperature and gravity, will be deduced and combined with spectroscopy in a subsequent paper.

7.1 Observations and data reduction

During seven nights in December 2008 and January 2009, absolute photometry of NGC 884 was taken with the CCD camera Merope at the Mercator telescope at ORM. Since the FoV of this CCD is small, four slightly overlapping fields were mapped to contain as many field stars observed in the multi-site campaign as possible. The seven Geneva filters U, B1, B, B2, V1, V and G were used in long and short exposures to have enough signal for the fainter stars while not saturating the bright ones. Three to four different measurements spread over different nights were carried out to average out possible variations. The calibration and reduction of these data were performed as described above in Sects. 4 and 5.

In between the measurements of the cluster, Geneva standard stars were observed to account for atmospheric changes. They were carefully chosen over different spectral types and observed at various air masses to quantify the extinction of the night. Because the standard stars were very bright and isolated, they were often defocused, and their light was measured by means of aperture photometry with a large radius. A correction factor, determined by bright isolated cluster stars, was applied to the cluster data to quantify their flux in the same way as the standard stars.

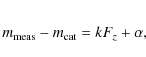

First, the measured magnitudes

![]() were corrected for the exposure time

were corrected for the exposure time

![]() with the formula

with the formula

We then determined the extinction in each night for each filter through the measured and catalogue values (Rufener 1988; Burki 2010) of the standard stars

where k is the extinction coefficient, Fz the airmass of the star and

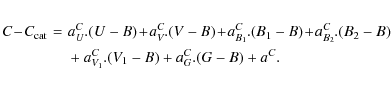

Despite the effort to match the physical passbands of the

CCD system to the reference photometric system,

a discrepancy

between the observed and catalogue values of the standard stars

emerged. It depended on the colours of the stars and was

partly

due to some flux leakage at red wavelenghts of the camera. Therefore an

additional transformation to the standard Geneva system is needed. Bratschi (1998) studied the

transformation

from the natural to the standard Geneva system based on

CCD measurements of 242 standard stars.

He remarked that

the colour-colour residuals clearly show that the connection between

these two systems is not a simple relation governed by a single colour

index, but rather a relation between the full photometric property of

the stars and residuals. Since using all colour indices may not be the

most robust and simple way for a transformation as the colour indices

are strongly related, he tested whether to use all or a subset

of

indices. Bratschi (1998)

concluded that all indices are needed to remove small local

discrepancies of

the residuals in relation to the different colours, leading to a

significant improvement of the quality of reduction. Following Bratschi (1998), we fitted the

most general linear transform to the data of the standard stars

In this expression, C stands for the six measured Geneva colours on the one hand and the measured V magnitude on the other hand, leading to seven equations in total. The different coefficients aij were determined with a linear least squares fitting and the cluster data were then transformed to the standard system.

In each step described above, we calculated the error propagation. Furthermore, a weighted mean over the different final measurements of each star was taken to average out unwanted variations, leaving us with one final value of the star in each Geneva filter.

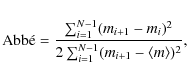

7.2 Cluster parameters

A number of photometric diagrams in the Geneva system are appropriate

to study cluster parameters. These include (X,Y),

(X,V),

(B2-V1,B2-U)

and (B2-V1,V),

where X and Y

are the so-called reddening-free parameters. For their definition and

meaning, we refer to Carrier

et al. (1999) and references therein. In Carrier et al. (1999),

the procedures to deduce the reddening, distance and age of the cluster

are explained. We checked the validity of the assumption of uniform

reddening in the cluster. For this purpose, we determined the

reddening

E(B2-V1)

of the cluster with the calibration of Cramer

(1993)

by means of selected B-type cluster members and omitting the known

Be stars, since they are additionally reddened by a

surrounding

disk. The spread in the reddening values was large, having

a peak-to-peak difference of

E(B2-V1)=0.21,

which corresponds to

![]() in the Johnson system

following the relations

in the Johnson system

following the relations

![]() and E(B2-V1)=0.75 E(B-V)

given by Cramer

(1984,1999).

Moreover, these reddening variations seemed not randomly spread over

the cluster, but show instead spatial correlations. Hence

we performed a simulation by randomly permuting the reddening

values and measuring the rate of coordinate dependence by the slopes of

a linear least-squares fit in function of the CCD X

and Y coordinates. This simulation pointed

out that the probability of the correlation to be due to

noise is smaller than 10-5 and so

proved the non-uniformity of the reddening throughout the cluster,

shown in Fig. 8.

and E(B2-V1)=0.75 E(B-V)

given by Cramer

(1984,1999).

Moreover, these reddening variations seemed not randomly spread over

the cluster, but show instead spatial correlations. Hence

we performed a simulation by randomly permuting the reddening

values and measuring the rate of coordinate dependence by the slopes of

a linear least-squares fit in function of the CCD X

and Y coordinates. This simulation pointed

out that the probability of the correlation to be due to

noise is smaller than 10-5 and so

proved the non-uniformity of the reddening throughout the cluster,

shown in Fig. 8.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[angle=270,width=8.8cm,clip]{13236_reddening.eps} %

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13236-09/Timg84.png)

|

Figure 8:

Colour-scale plot of the non-uniform reddening

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

After dereddening all stars by an interpolation of the calibrated

reddening values, we adjusted a zero-age main sequence (ZAMS) (Mermilliod 1981) to the

photometric diagrams, and this hinted at an over-estimation of the

reddening value by ![]() =

0.04

=

0.04 ![]() 0.01 in the Johnson system. The origin of this offset remains

unknown. The ZAMS fitting finally resulted in a distance

estimate

of about 2.2 kpc. To derive the age, we fitted the isochrones

of Schaller et al. (1992)

and Bertelli et al. (1994).

The models of Schaller

et al. (1992)

we used took standard overshooting, a standard mass loss and

solar

metallicity into account, and we used the models of Table 5 of

Bertelli et al. (1994),

suited for solar metallicity. The isochrone fitting lead to

a log age of 7.15

0.01 in the Johnson system. The origin of this offset remains

unknown. The ZAMS fitting finally resulted in a distance

estimate

of about 2.2 kpc. To derive the age, we fitted the isochrones

of Schaller et al. (1992)

and Bertelli et al. (1994).

The models of Schaller

et al. (1992)

we used took standard overshooting, a standard mass loss and

solar

metallicity into account, and we used the models of Table 5 of

Bertelli et al. (1994),

suited for solar metallicity. The isochrone fitting lead to

a log age of 7.15 ![]() 0.15 where part of the error is due to

systematic differences among the theoretical models. Figure 9 denotes the

dereddened and extinction corrected colour-magnitude

(B2-V1,V)-diagram,

showing a set of isochrones. All the derived values agree well with the

literature values mentioned in Sect. 2.

0.15 where part of the error is due to

systematic differences among the theoretical models. Figure 9 denotes the

dereddened and extinction corrected colour-magnitude

(B2-V1,V)-diagram,

showing a set of isochrones. All the derived values agree well with the

literature values mentioned in Sect. 2.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13236_hr.eps}\vspace*{-3mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13236-09/Timg86.png)

|

Figure 9: Dereddened and extinction corrected colour-magnitude (B2-V1,V)-diagram, showing four isochrones: two for log age = 7.1 and 7.2 from Schaller et al. (1992) in blue and two for the same age from Bertelli et al. (1994) in green. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

8 Variable stars

For the discussion below we divided the variable stars according to their spectral type, determined by the absolute photometry, which was taken for all stars in a homogeneous and consistent way. Thanks to the design of the Geneva small band filters, B2-V1 is an excellent effective temperature indicator, and the orthogonal reddening-free parameters X and Y show the spectral type of a star, whether it belongs to the cluster or not (Kunzli et al. 1997). If no absolute photometry was available for the star of interest, (V-I,V)- and (B-V,V)-diagrams based on relative photometry were inspected. We also compared literature values for spectral types with the outcome of our photometric diagrams. Further, we classify the stars by their observed variability behaviour: multi-periodic, mono-periodic (possibly with the presence of harmonics) or irregular. The eclipsing binaries are treated in a separate subsection.

All figures for the discovered variable stars can be found in the electronic Appendix A, where we show for each star the V light curve, a phase plot folded with the main frequency, the photometric diagrams, the window function and the generalised Lomb-Scargle diagrams in the different steps of subsequent prewhitening in the V-filter. Each separate category of variables will be described here with some typical and atypical examples. For an extensive overview of the properties of the known classes of pulsating stars, we refer to Chapter 2 of Aerts et al. (2009).

Below we adopted a numbering scheme to discuss the stars. Cross referencing to WEBDA numbering (http://www.univie.ac.at/webda/), which is based on the Oosterhoff (1937) numbering and extended to include additional stars coming from other studies, is available in Table A.1 in the electronic Appendix A. This table also contains an overview of the coordinates of the star, its spectral type, its mean Geneva V, B2-V1 and B2-U photometry and its main frequency and amplitude. We recall that we do not list all the frequencies found from the automated analysis in Table A.1. We will provide the final frequencies from a detailed analysis tuned to the various types of pulsators, which may be slightly different from those found here, in a follow-up paper for further use in stellar modelling.

8.1 Variable B-type stars

8.1.1 Multi-periodic B-type stars

Figures showing the multi-periodic B-type stars can be found in the

electronic Appendix A

as Figs. A.1-A.72. The

classical multi-periodic B-type stars are ![]() Cep and

SPB stars.

Cep and

SPB stars. ![]() Cep

stars are early B-type stars showing p-modes with frequency values

ranging from 3 to 12 d-1.

SPB stars are later B-type stars exciting g-modes with lower

frequencies from 0.3 to 1 d-1.

Hybrid B-pulsators, showing at the same time p- and g-modes,

also exist.

Cep

stars are early B-type stars showing p-modes with frequency values

ranging from 3 to 12 d-1.

SPB stars are later B-type stars exciting g-modes with lower

frequencies from 0.3 to 1 d-1.

Hybrid B-pulsators, showing at the same time p- and g-modes,

also exist.

A typical new ![]() Cep

star is the early-B star 00011, where we observed three

independent frequencies, f1=4.582 d-1,

f2=5.393 d-1

and f5=4.449 d-1

and one harmonic frequency, f4=2

f1

(see Figs. 10, 11). We have to

be careful with the interpretation of frequency f3=1.053 d-1:

although it deviates more than the resolution (0.001 d-1)

from 1.003 d-1, the application of

Sys-Rem can have enhanced this difference.

Cep

star is the early-B star 00011, where we observed three

independent frequencies, f1=4.582 d-1,

f2=5.393 d-1

and f5=4.449 d-1

and one harmonic frequency, f4=2

f1

(see Figs. 10, 11). We have to

be careful with the interpretation of frequency f3=1.053 d-1:

although it deviates more than the resolution (0.001 d-1)

from 1.003 d-1, the application of

Sys-Rem can have enhanced this difference.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13236_00011.lc.eps}\vspace*{...

...space*{1mm}

\includegraphics[width=8.5cm,clip]{13236_00011.abs.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13236-09/Timg87.png)

|

Figure 10: Light curve ( top), phase plot ( middle) and photometric diagrams ( bottom) of star 00011. The light curve and phase plot are made from the V-filter observations and the different colours denote the different observing sites: ORM - orange, OFXB - dark pink, Michelbach - light blue, Biaków - yellow, Athens - light pink, EUO - dark blue, TUG - brown, Xinglong - green and SOAO - purple. The phase plot is folded with the main frequency, denoted in the X-label and whose value is listed in Table A.1. The different colours in the photometric diagrams indicate the spectral types: B0-B2.5 - dark blue, B2.5-B9 - light blue, A - green, F0-F2 - yellow, F3-F5 - orange, F6-G - red, K-M - brown. The big dot with error bars shows the position of star 00011 in these figures. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{13236_00011.per.eps} %

\vspace*{-3mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/07/aa13236-09/Timg88.png)

|

Figure 11: Frequency analysis for star 00011. We show the window function ( top) and the generalised Lomb-Scargle periodograms in the different steps of subsequent prewhitening in the V-filter. The detected frequencies are marked by a yellow band, the red line corresponds to the noise level and the orange line to the S/N=4 level. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

A typical SPB star is star 02320 (Figs. A.63, A.64). This star has three significant frequencies: f1=0.883 d-1, f2=0.964 d-1 and f3=1.284 d-1.

We also found stars exciting p- and g-modes simultaneously.

For example star 00030 (Figs. A.15, A.16) has two

low frequencies f1=0.340 d-1

and f2=0.269 d-1,

which are typical values for SPB-type pulsations, and it shows one

frequency in the ![]() Cep

star range: f4=7.189 d-1,

while f3=0.994 d-1

is again too close to 1.003 d-1 to be

accepted as intrinsic to the star.

Cep

star range: f4=7.189 d-1,

while f3=0.994 d-1

is again too close to 1.003 d-1 to be

accepted as intrinsic to the star.

We also found some anomalies in the typical classification of

variable

B-stars. First of all, star 02320 is actually the only

SPB candidate in the multi-periodic B-star sample. All other

later

B-type stars exhibit pulsations with higher frequency values than

expected, e.g. the intrinsic frequencies of late-B

star 00183

(Figs. A.47, A.48) are f1=3.680 d-1

and f2=3.904 d-1,

which fall in the interval of ![]() Cep

frequencies. This can however also be a rapidly rotating

SPB star,

since rotation can induce significant frequency shifts for

low-frequency g-modes. However, it could also be a member of a

new

class of low-amplitude pulsators bridging the red edge of the

SPB strip and the blue edge of the

Cep

frequencies. This can however also be a rapidly rotating

SPB star,

since rotation can induce significant frequency shifts for

low-frequency g-modes. However, it could also be a member of a

new

class of low-amplitude pulsators bridging the red edge of the

SPB strip and the blue edge of the ![]() Sct strip,

as recently found from CoRoT data by Degroote et al. (2009a).

Sct strip,

as recently found from CoRoT data by Degroote et al. (2009a).

Another peculiar star is star 00024 (Figs. A.11, A.12),

an early Be-star that revealed two significant frequencies

that are low for classical ![]() Cep

pulsations: f1 = 1.569 d-1

and f4 = 1.777 d-1.

The frequencies are also rather high to be of the SPB class.

The

phase behaviour looks different from a simple sine wave: looking at

other known Be stars, this behaviour seems quite typical for

these

stars, since frequencies and/or amplitudes may change over time as

recently found from uninterrupted CoRoT photometry (e.g., Neiner

et al. 2009; Huat et al. 2009).

Cep

pulsations: f1 = 1.569 d-1

and f4 = 1.777 d-1.

The frequencies are also rather high to be of the SPB class.

The

phase behaviour looks different from a simple sine wave: looking at

other known Be stars, this behaviour seems quite typical for

these

stars, since frequencies and/or amplitudes may change over time as

recently found from uninterrupted CoRoT photometry (e.g., Neiner

et al. 2009; Huat et al. 2009).

Star 02451 (Figs. A.69, A.70) showed

clear variations around 25 and 29 d-1,

frequency values we would expect for ![]() Sct stars.

Because of its B-star appearance in the photometric diagrams, the star

is therefore probably no cluster member.

Sct stars.

Because of its B-star appearance in the photometric diagrams, the star

is therefore probably no cluster member.

8.1.2 Mono-periodic B-type stars

The figures of the frequency analysis for mono-periodic B-type stars can be found in the electronic Appendix A in Figs. A.73-A.150. For the mono-periodic cases, the same nature of pulsations as described above is also observed. However, because we did not find more than one independent frequency, we cannot be sure that the variations are caused by oscillations. Possibilities like spotted stars or ellipsoidal binaries cannot be ruled out, especially if we also deduce harmonics.

Star 00082 (Figs. A.95, A.96) is a typical example: f1 = 0.639 d-1 and f2 = 2 f1 and the phase plot folded with the main frequency is therefore clearly not sinusoidal. Because of the high amplitude of f1, it is possible that we are dealing with non-sinusoidal SPB-oscillations, but it could also be a spot.

In this sample we also have some B-type supergiants that vary

with SPB-type periods. These were originally discovered by Waelkens et al. (1998)

in the Hipparcos mission and were studied in detail

by Lefever et al. (2007).

For instance, star 00008 (Figs. A.75, A.76),

is listed as B2I supergiant (Slesnick

et al. 2002) and has one clear frequency at f2=0.211 d-1.

Possibly ![]() is also present, which is not so surprising since the oscillations of

supergiant stars are often non-sinusoidal.

is also present, which is not so surprising since the oscillations of

supergiant stars are often non-sinusoidal.

8.1.3 Irregular B-type stars

For some stars, the automatic frequency analysis failed, since long-term trends dominate the light curves. This is the case for Be stars that undergo an outburst. For instance, the light curve of star 00009 (Fig. 12) revealed a huge outburst in the beginning of the second observing season and a smaller one in the third observing season. Smaller variations are possibly still hidden in the time series, but a more detailed analysis should point this out.

| Figure 12: Light curve of Be-star 00009, showing outbursts. The different colours denote the different observing sites as in Fig. 10, the light brown data come from the Vienna Observatory. |

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

Other Be stars without significant frequencies do not always show an outburst, but frequency and/or amplitude changes prevented us from detecting the frequency values. Zooms of the light curve sometimes show clear periodicity on time-scales of several hours. Their light curves and some zooms are shown in Figs. A.152-A.159. Star 00003 behaves in the same way (see Fig. A.151), but is not known to be a Be star.

8.2 A- and F-type stars

8.2.1 Multi-periodic A- and F-type stars

Figures showing the multi-periodic A- and F-type stars can be found in

Figs. A.160-A.197 of the

electronic Appendix A.

These

stars are probably ![]() Sct

stars, exciting p-modes with frequencies ranging from 4 d-1

to 50 d-1 or

Sct

stars, exciting p-modes with frequencies ranging from 4 d-1

to 50 d-1 or ![]() Dor stars with

g-modes in the frequency interval from 0.2 d-1to 3 d-1.

Dor stars with

g-modes in the frequency interval from 0.2 d-1to 3 d-1.