| Issue |

A&A

Volume 513, April 2010

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A49 | |

| Number of page(s) | 8 | |

| Section | Stellar structure and evolution | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200911862 | |

| Published online | 23 April 2010 | |

New seismic analysis of the exoplanet-host star  Arae

Arae

M. Soriano - S. Vauclair

Laboratoire d'Astrophysique de Toulouse-Tarbes - UMR 5572 - Université de Toulouse - CNRS, 14 Av. E. Belin, 31400 Toulouse, France

Received 17 February 2009 / Accepted 15 January 2010

Abstract

Aims. We present detailed modelling of the exoplanet-host star ![]() Arae, using a new method for the asteroseismic analysis, and taking

into account the new value recently derived for the Hipparcos parallax.

The aim is to obtain precise parameters for this star and its internal

structure, including constraints on the core overshooting.

Arae, using a new method for the asteroseismic analysis, and taking

into account the new value recently derived for the Hipparcos parallax.

The aim is to obtain precise parameters for this star and its internal

structure, including constraints on the core overshooting.

Methods. We computed new stellar models in a wider range than

Bazot et al. (2005, A&A, 440, 615), with various chemical

compositions ([Fe/H] and Y), with or without overshooting at

the edge of the core. We computed their adiabatic oscillation

frequencies and compared them to the seismic observations. For each set

of chemical parameters, we kept the model which represented the best

fit to the echelle diagram. Then, by comparing the effective

temperatures, gravities and luminosities of these models with the

spectroscopic error boxes, we were able to derive precise parameters

for this star.

Results. First we find that all the models which correctly fit

the echelle diagram have the same mass and radius, with an uncertainty

of the order of one percent. Second, the final comparison with

spectroscopic observations leads to the conclusion that besides its

high metallicity, ![]() Arae has a high helium abundance of the order of Y = 0.3. Knowing this allows finding precise values for all the other parameters, mass, radius and age.

Arae has a high helium abundance of the order of Y = 0.3. Knowing this allows finding precise values for all the other parameters, mass, radius and age.

Arg5.

Key words: stars: oscillations - stars: interiors - stars: individual: ![]() Arae - planetary systems - stars: evolution - stars: abundances

Arae - planetary systems - stars: evolution - stars: abundances

1 Introduction

Asteroseismology of solar type stars is a powerful tool which can lead

to the precise determination of the stellar parameters when associated

with spectroscopic observations. Special tools have been developped for

this purpose, which help constraining the internal structure of the

stars from the observable acoustic frequencies. In previous papers

(e.g. Vauclair et al. 2008),

we developped a systematic way of comparing models with observations.

First, for each set of chemical composition [Fe/H] and Y,

we compute evolutionary tracks and for each mass the model which best

fits the observed large separation is derived. Then we keep only the

model that also best fits the observed echelle diagram. We finally have

a set of models correctly fitting the seismic data, with different

abundances. Interestingly enough, all these models have the same mass

and radius, and of course the same log g (see Vauclair et al. 2008, for the star ![]() Hor). All these models are placed in a log g - log

Hor). All these models are placed in a log g - log

![]() diagram,

together with the observed spectroscopic boxes. Finally we only keep

the models which satisfy all the constraints, including seismology and

spectroscopy. In this way, precise values of the stellar parameters are

found.

diagram,

together with the observed spectroscopic boxes. Finally we only keep

the models which satisfy all the constraints, including seismology and

spectroscopy. In this way, precise values of the stellar parameters are

found.

Here we test this method on the exoplanet-host star ![]() Arae (HD 160691). This G3 IV-V type star is at the centre of a four-planets system:

Arae (HD 160691). This G3 IV-V type star is at the centre of a four-planets system:

Arae b, a 1.7

Arae b, a 1.7  planet with an eccentric orbit (e = 0.31) and a period

planet with an eccentric orbit (e = 0.31) and a period

days (Butler et al. 2000; Jones et al. 2002);

days (Butler et al. 2000; Jones et al. 2002);

Arae c, a 14

Arae c, a 14

planet with

planet with

days. (Santos et al. 2004b);

days. (Santos et al. 2004b);

Arae d, recently discovered by Pepe et al. (2007), with a period

Arae d, recently discovered by Pepe et al. (2007), with a period

days and a mass of 0.52

days and a mass of 0.52  ;

;

Arae e, a long period planet (

Arae e, a long period planet (

years) with a mass of 1.81

years) with a mass of 1.81  (Jones et al. 2002; McCarthy et al. 2004; Pepe et al. 2007).

(Jones et al. 2002; McCarthy et al. 2004; Pepe et al. 2007).

The star's overmetallicity has been established by many groups of observers: Bensby et al. (2003), Laws et al. (2003), Santos et al. (2004a), Santos et al. (2004b) and Fischer & Valenti (2005) (see Table 1).

![]() Arae

was observed with the HARPS spectrometer at La Silla Observatory during

eight nights in June 2004 to obtain radial velocity time series. The

analysis of these data led to the discovery of up to 43 frequencies

that could be identified with p-modes of degrees

Arae

was observed with the HARPS spectrometer at La Silla Observatory during

eight nights in June 2004 to obtain radial velocity time series. The

analysis of these data led to the discovery of up to 43 frequencies

that could be identified with p-modes of degrees ![]() to 3 (Bouchy et al. 2005). A detailed modelling was given by Bazot et al. (2005).

They computed models with two different assumptions that could explain

the observed overmetallicity: overabundance of metals in the original

interstellar cloud or accretion of planetary material onto the star.

They tried to obtain evidence of the origin of

to 3 (Bouchy et al. 2005). A detailed modelling was given by Bazot et al. (2005).

They computed models with two different assumptions that could explain

the observed overmetallicity: overabundance of metals in the original

interstellar cloud or accretion of planetary material onto the star.

They tried to obtain evidence of the origin of ![]() Arae's overmetallicity. The results were not conclusive in that

respect, as the differences were not large enough to decide between the

two scenarii. Later on, other evidences were obtained that the observed

overmetallicity in exoplanet host stars must be original, not due to

accretion (see Castro et al. 2009).

Arae's overmetallicity. The results were not conclusive in that

respect, as the differences were not large enough to decide between the

two scenarii. Later on, other evidences were obtained that the observed

overmetallicity in exoplanet host stars must be original, not due to

accretion (see Castro et al. 2009).

We computed new models, testing various values of the original

metallicity and helium abundance. We compared the parameters of these

models with those obtained from spectroscopy, and introduced the new

value of the Hipparcos parallax, as given by van Leeuwen (2007).

We also analysed models with overshooting at the edge of the stellar

core. In some of these models, negative small separations appear so

that there is a crossing point in the echelle diagram for the lines

![]() .

This effect was specially discussed in Soriano & Vauclair (2008),

who showed that all solar type stars go through a stage where the small

separations become negative in the observable range of frequencies.

Here, we present a direct application of this theoretical effect, which

is used to constrain core overshooting.

.

This effect was specially discussed in Soriano & Vauclair (2008),

who showed that all solar type stars go through a stage where the small

separations become negative in the observable range of frequencies.

Here, we present a direct application of this theoretical effect, which

is used to constrain core overshooting.

Table 1:

Effective temperatures, gravities, and metal abundances observed for ![]() Arae. [Fe/H] ratios are given in dex.

Arae. [Fe/H] ratios are given in dex.

2 Stellar parameters

2.1 Spectroscopic constraints

In Bazot et al. (2005),

the effective temperatures and luminosities of the models were the

first parameters used for comparisons with the observations. We now

prefer to compare the models with the spectroscopic observations in a

more consistent way, by using the ``triplets''

![]() ,

log g

and [Fe/H]. These three parameters are indeed consistently given be the

same observers, while the luminosities are obtained in a different way,

using Hipparcos parallaxes. Here we compare the luminosities as a

second step. For this reason, we do not use exactly the same set of

references as given by Bazot et al. (2005), as we only keep those which give constraints on the surface gravity (see Table 1).

,

log g

and [Fe/H]. These three parameters are indeed consistently given be the

same observers, while the luminosities are obtained in a different way,

using Hipparcos parallaxes. Here we compare the luminosities as a

second step. For this reason, we do not use exactly the same set of

references as given by Bazot et al. (2005), as we only keep those which give constraints on the surface gravity (see Table 1).

2.2 The luminosity of  Arae

Arae

The visual magnitude of ![]() Arae is V=5.15 (SIMBAD Astronomical data base). Van Leeuwen (2007) carried out a new analysis of the Hipparcos data. He derived a new value of the parallax of

Arae is V=5.15 (SIMBAD Astronomical data base). Van Leeuwen (2007) carried out a new analysis of the Hipparcos data. He derived a new value of the parallax of ![]() Arae:

Arae:

![]() mas, which is lower than the first one derived by Perryman et al. (1997) and has a reduced error. Using this new value, we deduced an absolute magnitude of

mas, which is lower than the first one derived by Perryman et al. (1997) and has a reduced error. Using this new value, we deduced an absolute magnitude of

![]() .

.

From Table 1, we have an average value of effective temperature for ![]() Arae of

Arae of

![]() = 5800

= 5800 ![]() 100 K. Using the tables of Flower (1996), we obtained

100 K. Using the tables of Flower (1996), we obtained

![]() for the bolometric correction.

With a solar absolute magnitude of

for the bolometric correction.

With a solar absolute magnitude of

![]() (Lejeune et al. 1998), we deduced for

(Lejeune et al. 1998), we deduced for ![]() Arae a luminosity of log (L/

Arae a luminosity of log (L/![]()

![]() .

This value is lower than the one derived by Bazot et al. (2005) in their analysis of this star, namely log (L/

.

This value is lower than the one derived by Bazot et al. (2005) in their analysis of this star, namely log (L/![]()

![]() .

.

2.3 Seismic constraints

The star ![]() Arae was observed with the HARPS spectrograph, dedicated to the search

for exoplanets by the means of precise radial velocity measurements.

HARPS is installed on the 3.6 m-ESO telescope at la Silla

Observatory, Chile.

Arae was observed with the HARPS spectrograph, dedicated to the search

for exoplanets by the means of precise radial velocity measurements.

HARPS is installed on the 3.6 m-ESO telescope at la Silla

Observatory, Chile.

These measurements led to the identification of 43 p-modes of degrees ![]() to

to ![]() with frequencies between 1.3 and 2.6 mHz (Bouchy et al. 2005). The frequency resolution of the time-series was 1.56

with frequencies between 1.3 and 2.6 mHz (Bouchy et al. 2005). The frequency resolution of the time-series was 1.56 ![]() Hz, and the uncertainty on the oscillation modes has been evaluated to 0.78

Hz, and the uncertainty on the oscillation modes has been evaluated to 0.78 ![]() Hz. The mean large separation between two modes of consecutive order, computed in the observed range of frequencies, is

Hz. The mean large separation between two modes of consecutive order, computed in the observed range of frequencies, is

![]() 90

90 ![]() Hz, with an uncertainty of 1.1

Hz, with an uncertainty of 1.1 ![]() Hz.

The small separations present variations which are clearly visible in

the echelle diagram. Their average value in the observed range of

frequencies is

Hz.

The small separations present variations which are clearly visible in

the echelle diagram. Their average value in the observed range of

frequencies is

![]() Hz.

Hz.

3 Evolutionary tracks and models

We computed evolutionary tracks with the TGEC code (Hui Bon Hoa 2008; Richard et al. 1996), with the OPAL equations of state and opacities (Rogers & Nayfonov 2002; Iglesias & Rogers 1996) and the NACRE nuclear reaction rates (Angulo et al. 1999). For all models, the microscopic diffusion was included as in Paquette et al. (1986) and Michaud et al. (2004).

The treatment of the convection is done in the framework of the mixing

length theory and the mixing length parameter is adjusted as in the

Sun:

![]() (Richard et al. 2004). We also computed cases with

(Richard et al. 2004). We also computed cases with

![]() and

and

![]() to test the corresponding uncertainties. We found that for 1.10

to test the corresponding uncertainties. We found that for 1.10 ![]() and

and

![]() ,

the track is very close to that of 1.12

,

the track is very close to that of 1.12 ![]() and

and

![]() .

On the other side, the 1.10

.

On the other side, the 1.10 ![]() and

and

![]() track is close to the 1.08

track is close to the 1.08 ![]() and

and

![]() one. This was taken into account in the determination of the uncertainties on the final results (Sect. 5).

one. This was taken into account in the determination of the uncertainties on the final results (Sect. 5).

From the literature, we found two values for the metallicity of ![]() Arae: [Fe/H] = 0.29 (Laws et al. 2003, Fischer & Valenti 2005) and [Fe/H] = 0.32 (Bensby et al. 2003;

Santos et al. 2004a, b). For each value of [Fe/H], we first

computed two series of evolutionary tracks for two different values of

the helium abundance:

Arae: [Fe/H] = 0.29 (Laws et al. 2003, Fischer & Valenti 2005) and [Fe/H] = 0.32 (Bensby et al. 2003;

Santos et al. 2004a, b). For each value of [Fe/H], we first

computed two series of evolutionary tracks for two different values of

the helium abundance:

- a helium abundance increasing with Z as given by the Isotov & Thuan (2004) law for the chemical evolution of the galaxies: we label this value

;

;

- a solar helium abundance

= 0.2714.

= 0.2714.

The results obtained in the log g - log

![]() and log (L/

and log (L/![]() ) - log

) - log

![]() planes are displayed in Fig. 1.

Each graph corresponds to one value of the metallicity. On each graph,

the five error boxes are plotted, but those that correspond to the same

value of [Fe/H] as given by the groups of observers are drawn in

thicker lines.

planes are displayed in Fig. 1.

Each graph corresponds to one value of the metallicity. On each graph,

the five error boxes are plotted, but those that correspond to the same

value of [Fe/H] as given by the groups of observers are drawn in

thicker lines.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=12cm,clip]{aa11862-fig1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa11862-09/Timg37.png)

|

Figure 1:

Evolutionary tracks in the log g - log

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

We then computed two similar series including overshooting at the edge

of the convective core. Here overshooting is simply described as an

extension of the convective core by a length

![]()

![]() ,

where

,

where

![]() is the overshooting parameter, and

is the overshooting parameter, and ![]() the pressure scale height. In these two series, the overshooting parameter is fixed at

the pressure scale height. In these two series, the overshooting parameter is fixed at

![]() = 0.2 (Fig. 6). Finally, we tested more precisely the seismic constraints on overshooting by varying

= 0.2 (Fig. 6). Finally, we tested more precisely the seismic constraints on overshooting by varying

![]() in small steps between 0.0 and 0.2 for models of masses 1.1

in small steps between 0.0 and 0.2 for models of masses 1.1 ![]() (Fig. 7).

(Fig. 7).

4 Seismic tests and results

4.1 Models without overshooting

We computed the adiabatic oscillation frequencies for a large number of

models along each evolutionary track with the PULSE code (Brassard

& Charpinet 2008). These frequencies were computed for degrees ![]() to

to ![]() ,

and for radial orders typically ranging from 4 to 100. For each

track, we selected the model that has a mean large separation of

90

,

and for radial orders typically ranging from 4 to 100. For each

track, we selected the model that has a mean large separation of

90 ![]() Hz, computed in the same frequency range as the observed one. We plotted on each graph (Fig. 1) the corresponding iso-

Hz, computed in the same frequency range as the observed one. We plotted on each graph (Fig. 1) the corresponding iso-

![]() 90

90 ![]() Hz line. The parameters of these models are given in Tables 2 to 5. We can check that all the models that fit the same large separation present the same value of the parameter g/R or M/R3 where g, M and R are respectively the gravity, mass and radius of the star.

Hz line. The parameters of these models are given in Tables 2 to 5. We can check that all the models that fit the same large separation present the same value of the parameter g/R or M/R3 where g, M and R are respectively the gravity, mass and radius of the star.

This is because the large separation approximately varies like c/R, where c represents the mean sound velocity in the star, which itself approximately varies like

![]() .

With the usual scaling for the stellar temperature

.

With the usual scaling for the stellar temperature

![]() ,

we obtain that (c/R)2 varies like M/R3, independently of the chemical composition.

,

we obtain that (c/R)2 varies like M/R3, independently of the chemical composition.

Note in Fig. 1 that the iso-

![]() 90

90 ![]() Hz lines never cross Laws et al. (2003) or Santos et al. (2004a) error boxes. Models with

Hz lines never cross Laws et al. (2003) or Santos et al. (2004a) error boxes. Models with ![]() = 90

= 90 ![]() Hz have a value of log g much lower than the one derived by these two groups of observers.

Hz have a value of log g much lower than the one derived by these two groups of observers.

Table 2:

Characteristics of some overmetallic models with [Fe/H] = 0.32 and ![]() .

.

Kjeldsen et al. (2008)

discussed possible corrections on the frequencies due to near-surface

effects. They gave a parametrisation formula including three

parameters, in which two of them can be deduced from the third one. As

this parameter is unknown, they suggest using the same value for all

solar type stars as deduced for the Sun in a first approximation. They

find that the induced shifts increase with the frequency values, so

that it can slightly modify the computed mean large separation,

according to the frequency range. In our echelle diagrams for ![]() Arae, the models and the observations correctly fit when we do detailed mode to mode comparisons (Fig. 4).

We conclude that these near-surface effects are negligible in the

observed range of frequencies, i.e. at least up to 2.3 mHz.

Arae, the models and the observations correctly fit when we do detailed mode to mode comparisons (Fig. 4).

We conclude that these near-surface effects are negligible in the

observed range of frequencies, i.e. at least up to 2.3 mHz.

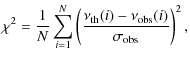

For each value of [Fe/H] and Y we searched, among the models which fit a mean large separation of 90 ![]() Hz,

the one which also gives the best fit to the observational echelle

diagram. In order to find this ``best model'', we performed a

Hz,

the one which also gives the best fit to the observational echelle

diagram. In order to find this ``best model'', we performed a ![]() minimization for the echelle diagram of the models. Tables 2 to 5 show the parameters of some models close to the minimum of

minimization for the echelle diagram of the models. Tables 2 to 5 show the parameters of some models close to the minimum of ![]() .

We used the expression

.

We used the expression

|

(1) |

where

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7cm,clip]{11862f2a.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa11862-09/Timg46.png)

|

Figure 2:

Evolution of the |

| Open with DEXTER | |

For all sets of chemical composition, the ![]() values present a minimum for models of mass M = 1.10

values present a minimum for models of mass M = 1.10 ![]() ,

radius

,

radius

![]() cm, and gravity log g = 4.21 (Fig. 2). These models represent the four ``best models'', one for each couple ([Fe/H], Y). Their echelle diagrams are displayed in Fig. 3.

For a better visibility of the figures, we give the observed mode

frequencies separately and the modelled ones as lines. It is remarkable

that their masses, radii and thus gravities are identical and has

important consequences, which will be discussed below.

cm, and gravity log g = 4.21 (Fig. 2). These models represent the four ``best models'', one for each couple ([Fe/H], Y). Their echelle diagrams are displayed in Fig. 3.

For a better visibility of the figures, we give the observed mode

frequencies separately and the modelled ones as lines. It is remarkable

that their masses, radii and thus gravities are identical and has

important consequences, which will be discussed below.

Table 3:

Characteristics of some overmetallic models with [Fe/H] = 0.29 and ![]() .

.

Table 4:

Characteristics of some overmetallic models with [Fe/H] = 0.32 and ![]() .

.

Table 5:

Characteristics of some overmetallic models with [Fe/H] = 0.29 and ![]() .

.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=12cm,clip]{aa11862-fig3.eps}\vspace*{-2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa11862-09/Timg48.png)

|

Figure 3:

Echelle diagrams for the best models with a metallicity of [Fe/H] = 0.29 ( upper panels) and [Fe/H] = 0.32 ( lower panels), and an helium abundance |

| Open with DEXTER | |

They all lie at the beginning of the subgiant branch. For ![]() ,

for both values of the metallicity, the models computed along the

evolutionay track have a convective core during the main sequence phase

which disappears at the present stage, leaving a helium core with sharp

edges. Models with a solar helium abundance

,

for both values of the metallicity, the models computed along the

evolutionay track have a convective core during the main sequence phase

which disappears at the present stage, leaving a helium core with sharp

edges. Models with a solar helium abundance ![]() do not develop a convective core during their evolution, they have a helium core with sharp boundaries.

do not develop a convective core during their evolution, they have a helium core with sharp boundaries.

For a fixed value of [Fe/H], the age of the best model decreases when the helium abundance increases (compare respectively Tables 2 and 4 and Tables 3 and 5). This is due to the difference in the evolutionary time scales according to the value of Y. The main sequence time scale increases for increasing helium abundance. As can be seen in Fig. 1, for a given value of [Fe/H] the effect of a smaller helium abundance is to move the models to lower effective temperatures. For a given value of Y, the models are cooler for a higher metallicity.

We plotted these four models in a log g - log

![]() plane, together with the spectroscopic error boxes (Fig. 5). We clearly see that models with the lower helium abundance

plane, together with the spectroscopic error boxes (Fig. 5). We clearly see that models with the lower helium abundance ![]() (models 2

and 4) lie outside the spectroscopic error boxes. Their effective

temperatures are too low compared to the values derived by the

spectroscopists. On the other hand, the models computed with a high

helium content (models 1 and 3) lie right inside the error

boxes: their external parameters correspond to those derived by

spectroscopy. These are also the models with the lowest

(models 2

and 4) lie outside the spectroscopic error boxes. Their effective

temperatures are too low compared to the values derived by the

spectroscopists. On the other hand, the models computed with a high

helium content (models 1 and 3) lie right inside the error

boxes: their external parameters correspond to those derived by

spectroscopy. These are also the models with the lowest ![]() (see Tables 2 to 5). The luminosities of all these models agree with that derived from the Hipparcos parallax, namely log (L/

(see Tables 2 to 5). The luminosities of all these models agree with that derived from the Hipparcos parallax, namely log (L/![]() )

)

![]() (Sect. 2.2). The echelle diagram for the best model 3 is also presented in Fig. 4 in more detail, with all the observed and modelled oscillation modes given separately.

(Sect. 2.2). The echelle diagram for the best model 3 is also presented in Fig. 4 in more detail, with all the observed and modelled oscillation modes given separately.

These models differ from the overmetallic model proposed by Bazot et al. (2005), which corresponded to a more massive star (1.18 ![]() )

on the main sequence. One of the reasons for this difference is related to the fact that in Bazot et al. (2005)

the luminosity was the basic parameter used for comparisons, and that

its value has been modified. The present analysis is more precise and

consistent in the comparison with the observations.

)

on the main sequence. One of the reasons for this difference is related to the fact that in Bazot et al. (2005)

the luminosity was the basic parameter used for comparisons, and that

its value has been modified. The present analysis is more precise and

consistent in the comparison with the observations.

Another reason for the different results obtained here is related to the helium content of the star. We find that only models with a high helium value (Y = 0.30) correctly reproduce all the observations. The helium abundance, which was kept as a free parameter by Bazot et al. (2005), is now well constrained. This determination of Y represents an important improvement.

Interestingly enough the case of ![]() Arae is different from that of

Arae is different from that of ![]() Hor, discussed by Vauclair et al. (2008). The asteroseismic study of

Hor, discussed by Vauclair et al. (2008). The asteroseismic study of ![]() Hor showed that its helium abundance was low (Y = 0.255), contrary to that of

Hor showed that its helium abundance was low (Y = 0.255), contrary to that of ![]() Arae.

These two different results have interesting implications for the

details of the nuclear processes which lead to the observed

overmetallicity. This will be discussed in the conclusion.

Arae.

These two different results have interesting implications for the

details of the nuclear processes which lead to the observed

overmetallicity. This will be discussed in the conclusion.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7cm,clip]{11862f4a.ps}\vspace*{-2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa11862-09/Timg50.png)

|

Figure 4:

Echelle diagram for the best model with a metallicity of [Fe/H] = 0.32 and a helium abundance |

| Open with DEXTER | |

4.2 Constraints on core overshooting

4.2.1 Models with

= 0.20

= 0.20

The observational echelle diagram presents characteristic variations

in the small separations. We were particularly interested in the fact

that around ![]() mHz the lines

mHz the lines ![]() and

and ![]() come close to each other, so that the small separation is smaller than average. In a previous paper (Soriano & Vauclair 2008) we noticed that the small separations between

come close to each other, so that the small separation is smaller than average. In a previous paper (Soriano & Vauclair 2008) we noticed that the small separations between ![]() and

and ![]() may vanish and become negative in stars at the end of the main sequence

phase due to their helium cores. In this case there is a crossing point

in the echelle diagram, with an inversion between

may vanish and become negative in stars at the end of the main sequence

phase due to their helium cores. In this case there is a crossing point

in the echelle diagram, with an inversion between ![]() and

and ![]() modes at high frequencies.

modes at high frequencies.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7cm,clip]{11862f5a.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa11862-09/Timg52.png)

|

Figure 5:

Representation of the five spectroscopic error boxes presented in Table 1 for the two values of metallicity: [Fe/H] = 0.29 (filled circles): Laws et al. (2003), Fischer & Valenti (2005); and [Fe/H] = 0.32 (filled triangles): Bensby et al. (2003), Santos et al. (2004a,b). The open symbols represent the four best models described in Table 2. They correspond to the two values of metallicities given above and to two different values of helium abundances: |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Here we wanted to check whether adding an overshooting layer at the

edge of the convective core could lead to such an effect and reproduce

the observed echelle diagram in a different way.

We tried to find a model that could fit the observational echelle

diagram and present a crossing point between the lines ![]() -

- ![]() at a frequency close to 2 mHz.

at a frequency close to 2 mHz.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=12cm,clip]{aa11862-fig6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa11862-09/Timg53.png)

|

Figure 6:

Evolutionary tracks in the log g - log

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

We computed evolutionary tracks with an overshooting parameter

![]() = 0.20 for the two values of metallicity: [Fe/H] = 0.29 and 0.32, the two values of helium abundance:

= 0.20 for the two values of metallicity: [Fe/H] = 0.29 and 0.32, the two values of helium abundance: ![]() and

and ![]() ,

and for masses ranging from 1.06 to 1.20

,

and for masses ranging from 1.06 to 1.20 ![]() (Fig. 6). As for the cases without overshooting, we picked up the models with a large separation of 90

(Fig. 6). As for the cases without overshooting, we picked up the models with a large separation of 90 ![]() Hz and draw curves of iso large separations.

Hz and draw curves of iso large separations.

In all these models, a convective core develops, even for masses smaller than 1.10 ![]() .

Models with masses ranging from 1.06 to 1.14

.

Models with masses ranging from 1.06 to 1.14 ![]() lie at the end of the main sequence. They have a high central helium abundance

lie at the end of the main sequence. They have a high central helium abundance ![]() ,

between 0.8 and 0.9. Most of these models present a crossing point between the

,

between 0.8 and 0.9. Most of these models present a crossing point between the ![]() and

and ![]() curves in the observed frequency range. However, as can be seen on the example shown in Fig. 8 (upper-left panel), the computed lines do not reproduce the observed ones.

curves in the observed frequency range. However, as can be seen on the example shown in Fig. 8 (upper-left panel), the computed lines do not reproduce the observed ones.

Models with masses higher than 1.14 ![]() correspond

to younger stars, still on the main sequence. Their convective core is

well developped, but their helium-content

correspond

to younger stars, still on the main sequence. Their convective core is

well developped, but their helium-content ![]() is not high enough to induce a discontinuity in the sound speed profile

and so to obtain negative small separations in the considered range of

frequencies. There is no crossing point in their echelle diagram. These

models do not fit the observational echelle diagram either, as can be

seen in the example in Fig. 8 (upper-right panel).

is not high enough to induce a discontinuity in the sound speed profile

and so to obtain negative small separations in the considered range of

frequencies. There is no crossing point in their echelle diagram. These

models do not fit the observational echelle diagram either, as can be

seen in the example in Fig. 8 (upper-right panel).

These results show that the observed frequencies in ![]() Arae cannot be interpreted in terms of a crossing point between the

Arae cannot be interpreted in terms of a crossing point between the ![]() and

and ![]() curves. This is consistent with the interpretation of the doublets observed in the

curves. This is consistent with the interpretation of the doublets observed in the ![]() curve in terms of rotational splitting (Bouchy et al. 2005). In this framework, the upper part of this curve could not be misinterpreted as

curve in terms of rotational splitting (Bouchy et al. 2005). In this framework, the upper part of this curve could not be misinterpreted as ![]() frequencies.

frequencies.

As overshooting with

![]() = 0.20

is excluded, we decided to test smaller overshooting parameters to

obtain a strong constraint on the possibility of overshooting in this

star.

= 0.20

is excluded, we decided to test smaller overshooting parameters to

obtain a strong constraint on the possibility of overshooting in this

star.

4.2.2 Constraints on the overshoot parameter

We computed new evolutionary tracks for models with 1.10![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7cm,clip]{11862f7a.ps}\vspace*{-2mm}\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa11862-09/Timg55.png)

|

Figure 7:

Evolutionary tracks for models of 1.10 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The more overshooting is added at the edge of the stellar core, the

more the evolutionary time scales are increased, as can be seen in

Fig. 7.

The developpement of the convective core is increased during a longer

main sequence phase. The models that have a mean large separation of

90 ![]() Hz are not in the same evolutionary stage, depending on the value of

Hz are not in the same evolutionary stage, depending on the value of

![]() ,

and they do not have the same internal structure. Models with

,

and they do not have the same internal structure. Models with

![]() < 0.002 are at the beginning of the subgiant branch, as are models without overshooting. When

< 0.002 are at the beginning of the subgiant branch, as are models without overshooting. When

![]() increases,

with a value between 0.002 and 0.10, the models are in the phase of

contraction of the convective core. And finally, for

increases,

with a value between 0.002 and 0.10, the models are in the phase of

contraction of the convective core. And finally, for

![]() >

0.10, the models are at the end of the main sequence. This difference

of evolutionary stages explains that the central helium abundance is

lower for models with a higher overshooting parameter.

>

0.10, the models are at the end of the main sequence. This difference

of evolutionary stages explains that the central helium abundance is

lower for models with a higher overshooting parameter.

Table 6:

Characteristics of the overmetallic models of 1.10 ![]() ,

[Fe/H] = 0.32, for several values of the oovershooting parameter.

,

[Fe/H] = 0.32, for several values of the oovershooting parameter.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=12cm,clip]{aa11862-fig8.eps} %

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa11862-09/Timg57.png)

|

Figure 8:

Echelle diagram for overmetallic models with overshooting: 1.06 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

We studied the evolution of the oscillation frequencies when

![]() increases. For small values of overshooting (

increases. For small values of overshooting (

![]() = 0.001 and

= 0.001 and

![]() = 0.002), there is no visible influence on the oscillations frequencies.

For

= 0.002), there is no visible influence on the oscillations frequencies.

For

![]() = 0.005, the reduced

= 0.005, the reduced ![]() is a little higher (

is a little higher (

![]() )

than for the model without overshooting. We can see on the echelle diagram (Fig. 8, middle-left panel) that the lines

)

than for the model without overshooting. We can see on the echelle diagram (Fig. 8, middle-left panel) that the lines ![]() -

- ![]() are closer for high frequencies. For

are closer for high frequencies. For

![]() = 0.01, these lines cross at

= 0.01, these lines cross at ![]() = 2.6 mHz, as can be seen in the echelle diagram (Fig. 8, middle-right panel). The

= 2.6 mHz, as can be seen in the echelle diagram (Fig. 8, middle-right panel). The ![]() has increased: 1.73.

For higher values of

has increased: 1.73.

For higher values of

![]() (

(

![]() > 0.01), the crossing point appears for lower frequencies decreasing for increasing

> 0.01), the crossing point appears for lower frequencies decreasing for increasing

![]() (Fig. 8, lower panels). Their

(Fig. 8, lower panels). Their ![]() value

is high (2.45 and 3.04, respectively). These models do not fit the

observations. We conclude from these computations that the overshooting

parameter is small in

value

is high (2.45 and 3.04, respectively). These models do not fit the

observations. We conclude from these computations that the overshooting

parameter is small in ![]() Arae, less than 0.01.

Arae, less than 0.01.

Let us recall however that in these computations overshooting is simply treated as an extension of the convective core. We have demonstrated that the seismic analysis of stars is able to give precise constraints on their central mixed zone. This does not exclude other kinds of mild macroscopic motions, plumes for instance, provided they do not lead to complete mixing.

5 Summary and discussion

This new analysis of the starThe procedure we use may be summarized as follows.

- We need at least the identification of

,

1 and 2 observational modes, and hopefully also

,

1 and 2 observational modes, and hopefully also  as in the present paper.

as in the present paper.

- Detailed comparisons of observed and computed modes are necessary. Global values of the so-called large and small separations are not precise enough to derive these parameters. The comparisons of detailed frequencies are needed to take into account the fluctuations and modulations induced by the internal structure of the star, in particular by the central mixed zone.

- In this framework, we first compare models and observations in the log g - log

plane.

We may check that whatever the chemical composition, models with the

same large separation have the same value of the M/R3 ratio, as predicted by the asymptotic theory.

plane.

We may check that whatever the chemical composition, models with the

same large separation have the same value of the M/R3 ratio, as predicted by the asymptotic theory.

- We then go further, by computing for various chemical compositions (Y, [Fe/H]) the model which fits the best the observed echelle diagram, using a

minimization process.

minimization process.

- One of the most important results at this stage, which was already pointed out for the case of the star

Hor by Vauclair et al. (2008),

is that these best models, obtained for various chemical compositions,

all have the same mass, radius, and thus gravity. With this method,

mass and radius are obtained with one percent uncertainty. On the other

hand, the age of the star still depends on the chemical composition,

basically the helium value.

Hor by Vauclair et al. (2008),

is that these best models, obtained for various chemical compositions,

all have the same mass, radius, and thus gravity. With this method,

mass and radius are obtained with one percent uncertainty. On the other

hand, the age of the star still depends on the chemical composition,

basically the helium value.

- Then we compare the position of these best models with the spectroscopic error boxes in the log g - log

diagram. This leads to the best choice of the chemical composition. In particular, we now constrain the Y value, which represents an important improvement compared to previous studies.

diagram. This leads to the best choice of the chemical composition. In particular, we now constrain the Y value, which represents an important improvement compared to previous studies.

- Finally we check that the luminosity of the best of all models is compatible with that derived from the apparent magnitude and the Hipparcos parallax.

The parameters found for ![]() Arae are given in Table 7. The uncertainties have been tentatively evaluated by allowing a possible

Arae are given in Table 7. The uncertainties have been tentatively evaluated by allowing a possible ![]() increase

of 0.1 for each set of models and an uncertainty of 0.1 on the mixing

length parameter. They take into account that all computations done

with various sets of chemical parameters converge on the same model

values. One must keep in mind however that these uncertainties do not

include systematic effects which would occur if stellar physics was

strongly modified (new opacities, new nuclear reaction rates, new

equation of state, etc.).

increase

of 0.1 for each set of models and an uncertainty of 0.1 on the mixing

length parameter. They take into account that all computations done

with various sets of chemical parameters converge on the same model

values. One must keep in mind however that these uncertainties do not

include systematic effects which would occur if stellar physics was

strongly modified (new opacities, new nuclear reaction rates, new

equation of state, etc.).

Table 7:

Parameters of ![]() Arae.

Arae.

The new model is different from that given in Bazot et al. (2005). Apart from the constraint on the Y

value, the basic reason is that in this previous paper the comparisons

were only based on the stellar luminosity, which was misleading due to

the Hipparcos parallax, which was later modified. Also the method used

at that time was not as precise as the one we now use. Note that the

scaling of parameters may lead to wrong results for stars in which the

seismic modes cannot be precisely identified . This is the case for

example for the mass proposed by Kallinger et al. (2010) for the star ![]() Arae, which is much too large (1.23

Arae, which is much too large (1.23 ![]() ).

).

We also performed an analysis of the size of the mixed core by testing the implications of overshooting on the mode frequencies. We found a strong constraint on the possibility of core overshooting, treated as an extension of convection: the size of this extension must be less than 0.5% of the pressure scale height (overshooting parameter). This does not exclude other kinds of mild boundary effects at the edge of the core, provided that they do not lead to strong mixing.

At the present time, we were able to perform this deep seismic

analysis on two solar type stars hosting planets, both with a large

metallicity (about twice solar): ![]() Hor (Vauclair et al. 2008) and

Hor (Vauclair et al. 2008) and ![]() Arae (this paper). In both cases, precise stellar parameters could be

obtained. We found however an important difference between these two

overmetallic stars.

Arae (this paper). In both cases, precise stellar parameters could be

obtained. We found however an important difference between these two

overmetallic stars.

In ![]() Hor,

the helium abundance is low, even lower than the solar value, in

accordance with the helium value determined forthe Hyades stellar

cluster. As other observational parameters also coincide, we concluded

that

Hor,

the helium abundance is low, even lower than the solar value, in

accordance with the helium value determined forthe Hyades stellar

cluster. As other observational parameters also coincide, we concluded

that ![]() Hor

is an ejected member of the Hyades. The reason why the helium abundance

is so low in these stars while the metallicity is high is still a

mystery, although it certainly depends on the mass of the stars that

polluted the original nebula.

Hor

is an ejected member of the Hyades. The reason why the helium abundance

is so low in these stars while the metallicity is high is still a

mystery, although it certainly depends on the mass of the stars that

polluted the original nebula.

In ![]() Arae,

on the other hand, the helium abundance is large, as expected from the

usual laws for the chemical evolution of galaxies (Isotov & Thuan 2004). This star was formed in a nebula which suffered normal pollution from stars with proportional yields of helium and metals.

Arae,

on the other hand, the helium abundance is large, as expected from the

usual laws for the chemical evolution of galaxies (Isotov & Thuan 2004). This star was formed in a nebula which suffered normal pollution from stars with proportional yields of helium and metals.

Seismology can lead to precise values of helium abundances in solar type stars, where helium cannot be directly derived from spectroscopy. This represents a success, quite apart from all other results and constraints, and will be of importance for the study of the chemical evolution of our Galaxy.

References

- Angulo C., Arnould M., Rayet M., et al. 1999, Nuclear Physics A, 656, 3 http://pntpm.ulb.ac.be/Nacre/nacre.htm [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bazot, M., Vauclair, S., Bouchy, F., & Santos, N. C. 2005, A&A, 440, 615 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bensby, T., Feltzing, S., & Lundström, I. 2003, A&A, 410, 527 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchy, F., Bazot, M., Santos, N. C., Vauclair, S., & Sosnowska, D. 2005, A&A, 440, 609 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Brassard, P., & Charpinet, S. 2008, Ap&SS, 316, 107 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R. P., Tinney, C. G., Marcy, G. W., et al. 2001, ApJ, 555, 410 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Castro, M., Vauclair, S., Richard, O., & Santos, N. C. 2009, A&A, 494, 663 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, D. A., & Valenti, J. A. 2005, ApJ, 622, 1102 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Flower, P. J. 1996, ApJ, 469, 355 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hui-Bon-Hoa, A. 2008, Ap&SS, 316, 55 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias, C. A., & Rogers, F. J. 1996, ApJ, 464, 943 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Isotov, Y. I., & Thuan, T. X. 2004, ApJ, 602, 200 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, H. R. A., Butler, R. P., Marcy, G. W., et al. 2002, MNRAS, 337, 1170 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kallinger, T., Weiss, W. W., Barban C., et al. 2010, A&A, 509, A77 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Kjeldsen, H., Bedding, T. R., & Christensen-Dalsgaard, J. 2008, ApJ, 683, L175 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Laws, C., Gonzalez, G., Walker, K. M., et al. 2003, AJ, 125, 2664 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lejeune, T., Cuisinier, F., & Buser, R. 1998, A&AS, 130, 65 [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, C., Butler, R. P., Tinney, C. G., et al. 2004, ApJ, 617, 575 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Michaud, G., Richard, O, Richer, J., & VandenBerg, D. 2004, ApJ, 606, 452 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Paquette, C., Pelletier, C., Fontaine, G., & Michaud, G. 1986, ApJS, 61, 177 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe, F., Correia, A. C. M., Mayor, M., et al. 2007, A&A, 462, 769 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Perryman, M. A. C., Lindegren, L., Kovalevsky, J., et al. 1997, A&A, 323, L49 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Richard, O., Vauclair, S., Charbonnel, C., & Dziembowski, W. A. 1996, A&A, 312, 1000 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Richard, O., Théado, S., & Vauclair, S. 2004, Sol. Phys., 220, 243 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [MathSciNet] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, F. J., & Nayfonov, A. 2002, ApJ, 576, 1064 [Google Scholar]

- Santos, N. C., Israelian, G., & Mayor, M. 2004a, A&A, 415, 1153 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Santos, N. C., Bouchy, F., Mayor, M., et al. 2004b, A&A, 426, 19 [Google Scholar]

- Simbad Astronomical Database, http://simbad.u-strasbg.fr [Google Scholar]

- Soriano, M., & Vauclair, S. 2008, A&A, 488, 975 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano, M., Vauclair, S., Vauclair, G., & Laymand, M. 2007, A&A, 471, 885 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [MathSciNet] [Google Scholar]

- Tassoul, M. 1980, ApJS, 43, 469 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen, F., ed. 2007, Hipparcos, the New Reduction of the Raw Data, (Astrophysics and Space Science Library), 350 [Google Scholar]

- Vauclair, S., Laymand, M., Bouchy, F., et al. 2008, A&A, 482, L5 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

All Tables

Table 1:

Effective temperatures, gravities, and metal abundances observed for ![]() Arae. [Fe/H] ratios are given in dex.

Arae. [Fe/H] ratios are given in dex.

Table 2:

Characteristics of some overmetallic models with [Fe/H] = 0.32 and ![]() .

.

Table 3:

Characteristics of some overmetallic models with [Fe/H] = 0.29 and ![]() .

.

Table 4:

Characteristics of some overmetallic models with [Fe/H] = 0.32 and ![]() .

.

Table 5:

Characteristics of some overmetallic models with [Fe/H] = 0.29 and ![]() .

.

Table 6:

Characteristics of the overmetallic models of 1.10 ![]() ,

[Fe/H] = 0.32, for several values of the oovershooting parameter.

,

[Fe/H] = 0.32, for several values of the oovershooting parameter.

Table 7:

Parameters of ![]() Arae.

Arae.

All Figures

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=12cm,clip]{aa11862-fig1.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa11862-09/Timg37.png)

|

Figure 1:

Evolutionary tracks in the log g - log

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7cm,clip]{11862f2a.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa11862-09/Timg46.png)

|

Figure 2:

Evolution of the |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=12cm,clip]{aa11862-fig3.eps}\vspace*{-2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa11862-09/Timg48.png)

|

Figure 3:

Echelle diagrams for the best models with a metallicity of [Fe/H] = 0.29 ( upper panels) and [Fe/H] = 0.32 ( lower panels), and an helium abundance |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7cm,clip]{11862f4a.ps}\vspace*{-2mm}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa11862-09/Timg50.png)

|

Figure 4:

Echelle diagram for the best model with a metallicity of [Fe/H] = 0.32 and a helium abundance |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7cm,clip]{11862f5a.ps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa11862-09/Timg52.png)

|

Figure 5:

Representation of the five spectroscopic error boxes presented in Table 1 for the two values of metallicity: [Fe/H] = 0.29 (filled circles): Laws et al. (2003), Fischer & Valenti (2005); and [Fe/H] = 0.32 (filled triangles): Bensby et al. (2003), Santos et al. (2004a,b). The open symbols represent the four best models described in Table 2. They correspond to the two values of metallicities given above and to two different values of helium abundances: |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=12cm,clip]{aa11862-fig6.eps}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa11862-09/Timg53.png)

|

Figure 6:

Evolutionary tracks in the log g - log

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7cm,clip]{11862f7a.ps}\vspace*{-2mm}\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa11862-09/Timg55.png)

|

Figure 7:

Evolutionary tracks for models of 1.10 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=12cm,clip]{aa11862-fig8.eps} %

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2010/05/aa11862-09/Timg57.png)

|

Figure 8:

Echelle diagram for overmetallic models with overshooting: 1.06 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| In the text | |

Copyright ESO 2010

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.