| Issue |

A&A

Volume 502, Number 1, July IV 2009

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Page(s) | 175 - 187 | |

| Section | Interstellar and circumstellar matter | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/200911820 | |

| Published online | 27 May 2009 | |

A spatial study of the mid-IR emission features in four Herbig Ae/Be stars

C. Boersma1 - E. Peeters2,3,4 - N. L. Martín-Hernández5 - G. van der Wolk1 - A. P. Verhoeff6 - A. G. G. M. Tielens7 - L. B. F. M. Waters6 - J. W. Pel1

1 - Kapteyn Astronomical Institute, PO Box 800, 9700 AV, Groningen, The Netherlands

2 - Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Western Ontario, London, ON N6A 3K7, Canada

3 - SETI Institute, 515 N. Whisman Road, Mountain View, CA 94043, USA

4 - NASA-Ames Research Center, Mail Stop 245-6, Moffet Field, CA 94035, USA

5 - Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, vía Láctea s/n, E38205 La Laguna, Spain

6 - Astronomical Institute ``Anton Pannekoek'', University of Amsterdam, Kruislaan 403, 1098 SJ Amsterdam, The Netherlands

7 - NASA-Ames Research Center, Mail Stop 245-3, Moffet Field, CA 94035, USA

Received 10 February 2009 / Accepted 9 May 2009

Abstract

Context. Infrared (IR) spectroscopy and imaging provide a prime tool to study the characteristics of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) molecules and the mineralogy in regions of star formation. Herbig Ae/Be stars are known to have varying amounts of natal cloud material present in their vicinity.

Aims. Our aim is to study the characteristics of the mid-IR emission originating in Herbig Ae/Be stars, especially the extent of the emission and how this relates to the (proto-)stellar characteristics.

Methods. Today's powerful ground- and space-based telescopes provide images and spectra at unprecedented spectral and spatial resolution. We analyse the images and spectra from four Herbig Ae/Be stars (IRAS 06084-0611, CD-42 11721, TY CrA, and HD 176386), as obtained with TIMMI2 on the ESO 3.6 m telescope and VISIR on the VLT. These observations are supplemented with data from ISO-SWS and Spitzer-IRAC.

Results. We find evidence for large-scale structure and extended emission in all four sources, except for HD 176386, which only shows silicate emission, all sources show PAH emission in their spectra. In addition, a spatially resolved silicate and PAH spectrum could be extracted for TY CrA.

Conclusions. The variety in emission scales distinguishes two classes. In the first, the morphology and spectral characteristics resemble those of reflection nebulae. In the second, the characteristics are in-line with Herbig A stars. This separation simply reflects a difference in stellar characteristics (e.g. luminosity). In Herbig B stars, dust emission from the surroundings dominates, where for Herbig A stars, the disk dominates the emission. In this scheme, IRAS 06084-0611 and CD-42 11721 resemble reflection nebulae and HD 176386 a more typical Herbig Ae/Be star. TY CrA shows characteristics common to both genuine reflection nebulae and Herbig B stars. We propose a geometry for TY CrA, with most notably, a ![]() 70 AU inner gap in the 340 AU circumtertiary disk cleared by a fourth stellar companion.

70 AU inner gap in the 340 AU circumtertiary disk cleared by a fourth stellar companion.

Key words: techniques: spectroscopic - infrared: ISM - ISM: molecules - astrochemistry

1 Introduction

Herbig Ae/Be stars are pre-main sequence stars of intermediate mass and spectral class A or B that exhibit emission lines and have associated nebulosities. Many Herbig Ae/Be stars show an infrared excess of thermal origin and non-zero polarisation at optical wavelengths. These are signs for circumstellar material, possibly distributed in a proto-planetary disk (Herbig 1960). Often, Herbig Ae/Be stars are considered as the younger/heavier counterparts of T Tauri stars (Waters & Waelkens 1998).

Herbig Ae/Be stars form in large molecular clouds, which initially can obscure them from sight. When the stellar light is able to break through, the star starts to illuminate its surroundings. Continuing their pre-main sequence evolution, the star will evacuate a cavity in the surrounding medium (e.g. NGC 2023 and NGC 7023). The (proto-)stellar mass determines the total luminosity and the number of ionising photons. More massive stars can clear out their direct surroundings more rapidly than less massive stars. Moreover, they provide stronger illumination, therefore, the neutral natal cloud material located far away will then become a reflection nebula. For less massive stars, hence less luminous, only their direct environment (e.g. circumstellar envelope) will be illuminated. In the final stages of the star's pre-main sequence evolution, the newly formed star will have removed most of its surrounding envelope, leaving only the remnant, dusty, accretion disk. These objects are known collectively as ``isolated'' Herbig Ae/Be stars (Waelkens & Waters 1997).

The infrared spectra of Herbig Ae/Be stars reveal a wide variety of

dust particles, including carbonaceous and (crystalline) silicate

grains (van den Ancker et al. 2000; Bouwman et al. 2000;

Waelkens et al. 1996). Specifically, many sources show IR

emission around 3.3, 6.2, 7.6, 7.8, 11.2, and 12.7 ![]() m, attributed

to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), i.e. large molecules of

many fused aromatic rings (Leger & Puget 1984;

Cohen et al. 1985; Allamandola et al. 1989).

m, attributed

to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), i.e. large molecules of

many fused aromatic rings (Leger & Puget 1984;

Cohen et al. 1985; Allamandola et al. 1989).

Isolated Herbig Ae/Be stars often show evidence for the onset of planet formation (dust coagulation, settling) and even planet formation itself (in a few cases, Reipurth et al. 2007).

Table 1: Stellar data.

Based on the size of the infrared excess and where in the spectrum it starts to dominate, a sub-division is made in Group I and II sources (Meeus et al. 2001). In the latter case, the infrared emission is more modest. This difference has been attributed to differences in disk geometry (Meeus et al. 2001): Group I sources have flaring disks and Group II sources have more flattened disks with a shadowed region. PAHs are a good diagnostic for this geometry, as they emit through UV-pumped fluorescence. Flaring disks subtend a larger solid angle viewed from the star and are thus able to reprocess more stellar light than flat disks.

The observed spectra reveal that PAHs undergo considerable processing during the early evolution of the YSO. Specifically, embedded object show a PAH spectrum resembling that of the ISM. More isolated Herbig Ae/Be stars show a more processed spectrum. These spectral variations imply considerable chemical changes, likely driven by the strong radiation field in the YSO's environment (Sloan et al. 2007; Boersma et al. 2008; Keller et al. 2008). Many aspects behind the processing, e.g. in what way the PAHs are modified, what process drives it, and when it commences, are not yet well understood. In this paper we compare spectra and images of four Herbig Ae/Be stars and speculate on the influence of stellar characteristics on the dust and morphology.

The paper has been organised as follows. In Sect. 2, the sources are introduced. In Sect. 3, the observations and data reduction are discussed. In Sect. 4 we describe our analysis and results. Subsequently, Sect. 5 presents a discussion and highlights the astronomical implications. Section 6 summarises our main conclusions.

2 The sources

CD-42 11721 is a southern galactic star embedded in a small and extremely thick dark cloud. While it has been suggested that CD-42 11721 possibly is an evolved B[e] super-giant (e.g. Borges Fernandes et al. 2007, and references therein), its association with a star forming region as well as more general characteristics, e.g. its luminosity class (IV), establishes it in our view as a young stellar object.

IRAS 06084-0611 is a red nebulous object embedded in the Monoceros molecular cloud. Two bright mid-infrared sources are seen in the mid-IR images from Persi & Tapia (2003) and are identified with the cometary H II region VLA1 (IRS 4) and the faint compact radio continuum source VLA4 (IRS 2). Persi & Tapia (2003) suggest the latter is probably a Herbig Ae/Be star.

TY CrA is a multiple star-system consisting of at least four

stars. Three stars are within 1.5 AU of each other, of which one is a

Herbig Ae/Be star. The fourth star is located at a projected distance

of ![]() 0.3

0.3

![]() (40 AU) from the compact tertiary

system. The three companions of the Herbig Ae/Be star are of later

M-type (Chauvin et al. 2003). TY CrA is located near one of the

densest parts of the R Corona Australis star-forming region, embedded

in the bright reflection nebula NGC 6726/6727.

(40 AU) from the compact tertiary

system. The three companions of the Herbig Ae/Be star are of later

M-type (Chauvin et al. 2003). TY CrA is located near one of the

densest parts of the R Corona Australis star-forming region, embedded

in the bright reflection nebula NGC 6726/6727.

HD 176386 is an optically detected pre-main sequence star with a

companion at ![]()

![]() (i.e. CCDM

J19017-3653B, Jeffers et al. 1963). The companion is likely a

low-mass star (Turon et al. 1993). Also, signs of ongoing

accretion have been reported (Grady et al. 2001). HD 176386 is

located in the R Corona Australis star-forming region,

(i.e. CCDM

J19017-3653B, Jeffers et al. 1963). The companion is likely a

low-mass star (Turon et al. 1993). Also, signs of ongoing

accretion have been reported (Grady et al. 2001). HD 176386 is

located in the R Corona Australis star-forming region,

![]()

![]() from TY CrA.

from TY CrA.

The stellar characteristics of the four objects considered here are summarised in Table 1.

3 Observations and reduction

We have performed a 10 ![]() m spectral imaging study of the four

Herbig Ae/Be stars introduced in Sect. 2. The Thermal

Infrared MultiMode Instrument (TIMMI2) at the ESO 3.6 m telescope

(Reimann et al. 2000) was used to obtain N-band imaging and

spectroscopy of CD-42 11721 and the two bright mid-IR positions in

IRAS 06084-0611 (VLA1 and VLA4). The Very large Imager and

Spectrometer for the mid-IR (VISIR, Lagage et al. 2004)

instrument at the Very Large Telescope (VLT) was used to obtain

imaging and spectra of HD 176386 and TY CrA. The data are supplemented

with data from the Short Wavelength Spectrometer

(SWS, de Graauw et al. 1996) on board ESA's Infrared Space

Observatory (ISO, Kessler et al. 1996) and from the InfraRed

Array Camera (IRAC, Fazio et al. 2004) on board NASA's

Spitzer space telescope. Table 2 summarises the data

obtained for each target. The ground-based observation log is shown in

Table 3.

m spectral imaging study of the four

Herbig Ae/Be stars introduced in Sect. 2. The Thermal

Infrared MultiMode Instrument (TIMMI2) at the ESO 3.6 m telescope

(Reimann et al. 2000) was used to obtain N-band imaging and

spectroscopy of CD-42 11721 and the two bright mid-IR positions in

IRAS 06084-0611 (VLA1 and VLA4). The Very large Imager and

Spectrometer for the mid-IR (VISIR, Lagage et al. 2004)

instrument at the Very Large Telescope (VLT) was used to obtain

imaging and spectra of HD 176386 and TY CrA. The data are supplemented

with data from the Short Wavelength Spectrometer

(SWS, de Graauw et al. 1996) on board ESA's Infrared Space

Observatory (ISO, Kessler et al. 1996) and from the InfraRed

Array Camera (IRAC, Fazio et al. 2004) on board NASA's

Spitzer space telescope. Table 2 summarises the data

obtained for each target. The ground-based observation log is shown in

Table 3.

Table 2: Collected data.

Table 3: Observation log of the TIMMI2 and VISIR data.

3.1 IRAC

The InfraRed Array Camera (IRAC, Fazio et al. 2004) is a

four channel camera providing simultaneous

![]() images at 3.6, 4.5, 5.8 and 8.0

images at 3.6, 4.5, 5.8 and 8.0 ![]() m. The detectors are 256

m. The detectors are 256![]() 256 pixels in size, giving a

pixel scale of

256 pixels in size, giving a

pixel scale of ![]() 1.2

1.2

![]() .

.

A large portion of the R Corona Australis star-forming region and the

Monoceros molecular cloud have been observed in the programme entitled

``Structure and Incidence of Young Embedded Clusters'' (PID 6). We

retrieved the post-Basic Calibrated Data (bcd; data that went through

the extended pipeline) for these regions from the Spitzer Science

Center (SSC) where it has been processed with pipeline version

S14.0.0. From the High-Dynamical-Range (hdr; short exposure) mosaic, a

![]() pixel sub-image was extracted around TY CrA and

HD 176386. For IRAS 06084-0611, a

pixel sub-image was extracted around TY CrA and

HD 176386. For IRAS 06084-0611, a

![]() pixel sub-image was

extracted around the positions of VLA1 and VLA4.

pixel sub-image was

extracted around the positions of VLA1 and VLA4.

CD-42 11721 has been observed by the Spitzer Legacy programme

GLIMPSE-Galactic Plane Survey (PID 192). Enhanced data products, made

available by the GLIMPSE team, were retrieved and from the mosaics, a

![]() pixel sub-image was extracted around CD-42 11721. Near

the centre, the image appears saturated in two distinct peaks.

pixel sub-image was extracted around CD-42 11721. Near

the centre, the image appears saturated in two distinct peaks.

For each source, the 3.6, 5.8 and 8.0 ![]() m maps were combined into a

single RGB-colour image, with the blue, green, and blue channel

representing 3.6, 5.8, and 8.0

m maps were combined into a

single RGB-colour image, with the blue, green, and blue channel

representing 3.6, 5.8, and 8.0 ![]() m, respectively. The resulting

images are presented in Fig. 1.

m, respectively. The resulting

images are presented in Fig. 1.

![\begin{figure}

\par\mbox{\includegraphics[height=75mm]{11820f01} \includegraphic...

...ight=75mm]{11820f02} }

\par\includegraphics[height=75mm]{11820f03}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/28/aa11820-09/Timg42.png) |

Figure 1:

Three colour composite IRAC images (red: 8.0, green: 5.8 and blue: 3.6 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

3.2 TIMMI2

TIMMI2 has a camera that uses a

![]() pixel Raytheon Si:As

array. In imaging, the N11.9-OCLI filter was selected and a pixel

scale of 0.2

pixel Raytheon Si:As

array. In imaging, the N11.9-OCLI filter was selected and a pixel

scale of 0.2

![]() ,

providing a total field of view of

,

providing a total field of view of

![]() .

For long-slit

spectroscopy, the 10

.

For long-slit

spectroscopy, the 10 ![]() m low-resolution grism was used. The grism

covers wavelengths from 7.5 to 13.9

m low-resolution grism was used. The grism

covers wavelengths from 7.5 to 13.9 ![]() m and provides a spectral

resolving power

m and provides a spectral

resolving power

![]() .

The slit was

.

The slit was

![]() in size and the pixel

scale,

in size and the pixel

scale,

![]() .

At the time of the observation, the slit

could only be oriented North-South.

.

At the time of the observation, the slit

could only be oriented North-South.

The slit was positioned across the two bright mid-IR components of

IRAS 06084-0611, VLA1 and VLA4, and across the central star of CD-42

11721 (see Fig. 1). In order to correct for background

emission from the sky, the observations were performed using a

standard North-South chopping/nodding technique. The applied nod

amplitude was the same as the chop amplitude, and the telescope nodded

opposite to the chopping direction of the secondary mirror. The

amplitude was

![]() for IRAS 06084-0611 and

for IRAS 06084-0611 and

![]() for CD-42 11721. These chop throws were large

enough to avoid confusion.

for CD-42 11721. These chop throws were large

enough to avoid confusion.

The N-band imaging of the standard stars were performed in the same filter as the target and used for photometric flux conversion from photon count rates (ADU/s) into astronomical units (Jy), for atmospheric corrections and for establishing the point spread function (PSF). To minimise residuals of the telluric line cancellation, the standard star and the target were observed at similar air masses. A flux correction provided by the TIMMI2 instrument team takes care of the (small) differential air mass between the target and the standard star that remains. The synthetic calibrated spectra for the standard stars are taken from Cohen et al. (1999).

Data processing included the removal of bad frames and summing of all

good chopping and nodding pairs. This procedure is applied to

both target and calibrator star. For each pixel, the uncertainty,

dominated by variations of the sky transparency, was propagated along

each step of the processing. However, the chop amplitude of

![]() used for CD-42 11721 turned out to be too large

for the telescope mechanics. This resulted in a varying chop amplitude

that introduced shifts of several pixels between the central position

of the source on each frame, producing a chopping smearing along the

North-South direction. This problem was solved by summing only the

chopping and nodding pairs with a shift

used for CD-42 11721 turned out to be too large

for the telescope mechanics. This resulted in a varying chop amplitude

that introduced shifts of several pixels between the central position

of the source on each frame, producing a chopping smearing along the

North-South direction. This problem was solved by summing only the

chopping and nodding pairs with a shift ![]() 1 pixel. For imaging and

spectroscopy this was 4 out of 48 and 196 out of 320 frames,

respectively.

1 pixel. For imaging and

spectroscopy this was 4 out of 48 and 196 out of 320 frames,

respectively.

The spectra were extracted over apertures of 1.5 times the (average)

full-width-at-half-maximum (FWHM) measured along the spatial

direction, where the FWHM for VLA1 and VLA4 are 4.7 and

3.6

![]() ,

respectively. The source profile of CD-42 11721

along the slit shows three emission peaks (see Figs. 1

and 2). Each of these peaks has been fitted

with a Gaussian. These were then used to extract the spectrum of each

component. In particular, the corresponding FWHM of the central peak

is 1.8

,

respectively. The source profile of CD-42 11721

along the slit shows three emission peaks (see Figs. 1

and 2). Each of these peaks has been fitted

with a Gaussian. These were then used to extract the spectrum of each

component. In particular, the corresponding FWHM of the central peak

is 1.8

![]() and 4.7

and 4.7

![]() for both the

bracketing peaks. The pixel-to-wavelength correspondence provided by

the TIMMI2 support team is applied for wavelength calibration. The

fully reduced spectra are presented in Figs. 3 and 4.

for both the

bracketing peaks. The pixel-to-wavelength correspondence provided by

the TIMMI2 support team is applied for wavelength calibration. The

fully reduced spectra are presented in Figs. 3 and 4.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm]{11820f04}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/28/aa11820-09/Timg51.png) |

Figure 2:

Two spatial cross-cuts of the TIMMI2 spectra of CD-42 11721. The top panel plots the continuum between 9.7 and 10.9 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{11820f05} \end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/28/aa11820-09/Timg52.png) |

Figure 3:

The top two panels show the TIMMI2 spectra of IRAS 06084-0611 VLA1 and VLA4. A comparison between the ISO-SWS spectrum and the TIMMI2 spectra of IRAS 06084-0611 VLA4 (see Fig. 1 for the apertures) is plotted in the middle panel. The lower two panels shows the FWHM of both sources as a function of wavelength (black diamonds), the FWHM of the sources in the 11.9 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8.9cm,clip]{11820f06}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/28/aa11820-09/Timg54.png) |

Figure 4:

The TIMMI2 spectra of the three components of CD-42 11721 (see Figs. 1 and 2, and Sect. 3.2) are shown in the top three panels. The fourth panel shows a comparison of the TIMMI2 spectrum of the four emission peaks combined with the ISO-SWS spectrum. The dashed lines show the fit made to the star (

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

3.3 VISIR

VISIR has two DRS, former Boeing,

![]() BIB detectors. In

spectroscopy the pixel scale was set to 0.127

BIB detectors. In

spectroscopy the pixel scale was set to 0.127

![]() .

The

low resolution (

.

The

low resolution (

![]() -390) configuration

with a 1

-390) configuration

with a 1

![]() slit was chosen to obtain spectra in the

8.8, 9.8, 11.4 and 12.2

slit was chosen to obtain spectra in the

8.8, 9.8, 11.4 and 12.2 ![]() m wavelength settings. A standard

chop-nodding along the slit was applied to correct for background

emission. The orientation of the slit was chosen such that, for TY

CrA, both the ``bar'' and the central star are probed (see

Fig. 1). For HD 17386 the orientation was chosen such that

it encompasses the two emission sources visible in the K-band (2.2

m wavelength settings. A standard

chop-nodding along the slit was applied to correct for background

emission. The orientation of the slit was chosen such that, for TY

CrA, both the ``bar'' and the central star are probed (see

Fig. 1). For HD 17386 the orientation was chosen such that

it encompasses the two emission sources visible in the K-band (2.2 ![]() m) acquisition image (see Fig. 1). Due to the extent

of TY CrA and HD 176386 and their direct surroundings, chopping was

done off the detector. Standard calibration has been done with

calibrators with similar air masses at the time of

observation. Detector Integration Times (DITs) were 0.0625 s for

both the 8.8 and 9.8

m) acquisition image (see Fig. 1). Due to the extent

of TY CrA and HD 176386 and their direct surroundings, chopping was

done off the detector. Standard calibration has been done with

calibrators with similar air masses at the time of

observation. Detector Integration Times (DITs) were 0.0625 s for

both the 8.8 and 9.8 ![]() m wavelength settings and 0.05 and 0.04 s for the 11.4 and 12.2

m wavelength settings and 0.05 and 0.04 s for the 11.4 and 12.2 ![]() m wavelength settings,

respectively. To improve the signal-to-noise, all four wavelength

settings were observed two times 10 min for TY CrA, and four times

10 min for HD 176386.

m wavelength settings,

respectively. To improve the signal-to-noise, all four wavelength

settings were observed two times 10 min for TY CrA, and four times

10 min for HD 176386.

The initial reduction steps are performed by the standard ESO reduction pipeline software, making use of the graphical user interface to the pipeline, GASGANO. Pipeline products include the final, summed, distortion-corrected 2D spectrum for each wavelength setting, a pixel-to-wavelength map and a synthetic spectrum of the calibrator. The following reduction steps, are applied to the 2D spectra.

The residual background is corrected by fitting, ignoring the target's

dispersion profile, each pixel row with a second order polynomial and

subtracting it. Weight maps are constructed from the 2D spectra by

collapsing them into the wavelength direction and forcing the area

underneath the resulting spatial profile to one. The next step is

multiplying the weight maps with the 2D spectra and collapsing the

results in the spatial direction. The obtained 1D spectra are

wavelength calibrated using the earlier obtained pixel-to-wavelength

mapping. The target is flux calibrated by multiplying the target

spectra by the synthetic spectra and dividing by the calibrator's

spectra. Also, in view of the difference in chopping technique (off

and on the slit), the number of beams on the detector is taken into

account: two for the off-source chopped target and four for the

calibrators. The four different wavelength settings are spliced to the

mean of the overlapping area by multiplication by a factor, keeping

the 9.8 ![]() m wavelength setting constant. In the final reduction

steps, all observations are combined. A correction for any uniform

differences in flux is made by multiplying by a factor that brings the

separate observations to the mean. The uncertainties are constructed

by taking the statistical difference between all observations.

m wavelength setting constant. In the final reduction

steps, all observations are combined. A correction for any uniform

differences in flux is made by multiplying by a factor that brings the

separate observations to the mean. The uncertainties are constructed

by taking the statistical difference between all observations.

On top of the general reduction scheme described above, additional

steps were required for TY CrA and HD 176386. Inspection of the

(wavelength collapsed) spatial emission profile of TY CrA reveals two

blended components in the source profile.

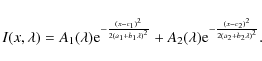

To disentangle both components we fit a function described by Eq. (1), where each diffraction pattern is assumed Gaussian and the wavelength dependent FWHM of the pattern is taken linear (

The 2D spectral images of HD 176386 display two spatially separated sources. Hereafter these sources are referred to as Position 1 and Position 2. Position 1 corresponds to HD 176386 itself. For some observations, some wavelength settings show a strong varying background. Therefore, the Position 1 and 2 spectra are extracted by masking out the emission from the other position and following the reduction steps described above, but disregarding the wavelength settings where the background turns out to be too unstable for a proper extraction. Fortunately, for each wavelength setting there were at least two good observations, allowing for the construction of a complete spectrum. Figure 7 presents the spectrum of Position 1, median smoothed over 5 resolution elements.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm]{11820f07}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/28/aa11820-09/Timg62.png) |

Figure 5: Spectra for the total, amorphous silicate and PAH component of TY CrA when integrating the area underneath the Gaussians fitted to the spatial profile (see text for details). |

| Open with DEXTER | |

| |

Figure 6: FWHM as a function of wavelength of the amorphous silicate and PAH components in TY CrA. Also shown is the FWHM of the calibrator as a function of wavelength. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm]{11820f09}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/28/aa11820-09/Timg64.png) |

Figure 7: VISIR spectrum of HD 176386 Position 1, median smoothed over 5 elements. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

3.4 ISO-SWS

ISO's SWS instrument provided medium and high spectral resolution in

the wavelength region from 2.38 to 45.2 ![]() m. For wavelengths

smaller than 12

m. For wavelengths

smaller than 12 ![]() m, the aperture on the sky was

m, the aperture on the sky was

![]() in size, for wavelengths

between 12 and 27.5

in size, for wavelengths

between 12 and 27.5 ![]() m

m

![]() .

These apertures are

indicated in Fig. 1.

.

These apertures are

indicated in Fig. 1.

All data were processed with IA3, the SWS Interactive Analysis package, using calibration files and procedures equivalent with pipeline version 10.1. A detailed account of the reduction can be found in Peeters et al. (2002b). Table 4 summarises the observations and the fully reduced spectra are presented in Fig. 8.

4 Analysis and results

For ISO-SWS data, PAH bands strengths are taken from Hony et al. (2001), van Diedenhoven et al. (2004) and Hony et al. (2001). When unavailable, these were calculated directly from the ISO-SWS spectrum following the procedures outlined by these authors. The PAH band strengths are presented in Table 5.

The IRAC images display a wealth of structure (Fig. 1). Therefore, some confusion is likely present in the spectra from these sources. In the following subsections the extent of the different sources and emission components are determined. The results have been summarised in Table 6.

4.1 IRAS 06084-0611

The 3-colour IRAC image shows a nebulous region encompassing both VLA1 and VLA4, with an arm stretching towards the North-Eastern direction (Fig. 1).

The TIMMI2 spectra show for both sources quite different behaviour

(top two panels of Fig. 3). VLA1's spectral shape

resembles that of an embedded YSO, whereas VLA4 shows a far richer

spectrum with strong PAH features at 8.6, 11.2 and 12.7 ![]() m. The

ISO-SWS spectrum also shows these PAH features, in addition to those

at 3.3, 6.2 and ``7.7''

m. The

ISO-SWS spectrum also shows these PAH features, in addition to those

at 3.3, 6.2 and ``7.7'' ![]() m (Fig. 8).

m (Fig. 8).

The short wavelength ISO-SWS aperture only covers VLA4, while the long wavelength ISO-SWS aperture encompasses both VLA1 and VLA4. Comparison of the ISO-SWS observations with the TIMMI2 observations centred on VLA4 is done in the third panel of Fig. 3. The apparent flux difference reflects the extent of the emission and the difference in aperture/slit size between TIMMI2 and ISO-SWS. The similarity between the continuum in the ISO-SWS spectrum and the TIMMI2 spectrum of VLA1 is striking and suggests a contribution of VLA1 to the ISO-SWS spectrum of VLA4 (Fig. 3).

The ISO-SWS spectrum also shows the 15.25 ![]() m CO

m CO![]() -ice feature,

which we attribute to absorption by ice grains along the line of sight

towards the deeply embedded and very red object VLA1. Figure 9 presents the absorption profile in detail. Following the

procedure outlined by Boogert (1999, Chapter 5 of his thesis), we obtain an ice temperature of 100-110 K, typical for an

embedded YSO.

-ice feature,

which we attribute to absorption by ice grains along the line of sight

towards the deeply embedded and very red object VLA1. Figure 9 presents the absorption profile in detail. Following the

procedure outlined by Boogert (1999, Chapter 5 of his thesis), we obtain an ice temperature of 100-110 K, typical for an

embedded YSO.

Table 4: Summary of the ISO-SWS observations.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm]{11820f10}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/28/aa11820-09/Timg71.png) |

Figure 8:

ISO-SWS spectra of IRAS 06084-0611, CD-42 11721 and TY CrA. Indicated are the 3.3, 6.2, ``7.7'', 8.6, 11.2, 12.7, 16.4 and 17.4 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

To investigate the extent of the 10 ![]() m emission, the FWHM as a

function of wavelength is determined by fitting Gaussians to the

spatial profiles on the calibrated 2D spectral images at every

wavelength bin. The results are presented in the bottom two panels of

Fig. 3 and are compared to the FWHM of the

calibrator. VLA1 is resolved and has a size of about

2.8

m emission, the FWHM as a

function of wavelength is determined by fitting Gaussians to the

spatial profiles on the calibrated 2D spectral images at every

wavelength bin. The results are presented in the bottom two panels of

Fig. 3 and are compared to the FWHM of the

calibrator. VLA1 is resolved and has a size of about

2.8

![]() (2800 AU). VLA4 is also resolved and is more

extended in the PAH bands (

(2800 AU). VLA4 is also resolved and is more

extended in the PAH bands (![]() 2.2

2.2

![]() ;

2200 AU) than

in the continuum (

;

2200 AU) than

in the continuum (![]() 1.2

1.2

![]() ;

1300 AU). From the 11.9

;

1300 AU). From the 11.9

![]() m TIMMI2 image, a FWHM of

m TIMMI2 image, a FWHM of

![]() (2900 AU) and

(2900 AU) and

![]() (2000 AU) is derived for VLA1 and VLA4,

respectively. The sizes obtained from the images and spectra are in

reasonable agreement.

(2000 AU) is derived for VLA1 and VLA4,

respectively. The sizes obtained from the images and spectra are in

reasonable agreement.

In Fig. 10, the 11.2 and 10.5 ![]() m spatial profiles

of VLA4 are compared to the 11.2

m spatial profiles

of VLA4 are compared to the 11.2 ![]() m spatial profile from the

calibrator. Both the continuum (9.7-10.9

m spatial profile from the

calibrator. Both the continuum (9.7-10.9 ![]() m) and the PAH

emission (11.1-11.31

m) and the PAH

emission (11.1-11.31 ![]() m) are resolved and show a skewed

profile. The continuum has an extent of 1700 AU (non-Gaussian FWHM is

1.6

m) are resolved and show a skewed

profile. The continuum has an extent of 1700 AU (non-Gaussian FWHM is

1.6

![]() )

and the PAH emission extends over 2000 AU

(non-Gaussian

)

and the PAH emission extends over 2000 AU

(non-Gaussian

![]() ). The small difference in

the extent between here and in Fig. 3 is likely

due to the profile's deviation from a Gaussian.

). The small difference in

the extent between here and in Fig. 3 is likely

due to the profile's deviation from a Gaussian.

Table 5: PAH band strengths determined from the ISO-SWS spectra.

4.2 CD-42 11721

The 3-colour IRAC image shows a nebulous region

(Fig. 1). Although the centre of the image is saturated,

there appear two distinct emission peaks. One is the star, the other a

close-by patch. Both peaks are separated by 4.3

![]() (1700 AU). Additionally, an arc stretching towards the South-East is

visible, which is also seen in the 11.9

(1700 AU). Additionally, an arc stretching towards the South-East is

visible, which is also seen in the 11.9 ![]() m TIMMI2 and the 8.0

m TIMMI2 and the 8.0 ![]() m IRAC images. It is evident from the good agreement between the

TIMMI2 and IRAC contours that the problems introduced by the varying

chop throw (see Sect. 3) have been largely

corrected for by our applied reduction steps (see

Sect. 3.2). Note how the TIMMI2 slit cuts through both

distinct emission peaks and the arc. These three components are also

identifiable in the wavelength collapsed spatial cross-cuts of the

TIMMI2 spectra, Fig. 2. The separation between

the central two emission peaks in the cross-cut

(

m IRAC images. It is evident from the good agreement between the

TIMMI2 and IRAC contours that the problems introduced by the varying

chop throw (see Sect. 3) have been largely

corrected for by our applied reduction steps (see

Sect. 3.2). Note how the TIMMI2 slit cuts through both

distinct emission peaks and the arc. These three components are also

identifiable in the wavelength collapsed spatial cross-cuts of the

TIMMI2 spectra, Fig. 2. The separation between

the central two emission peaks in the cross-cut

(![]() 4.0

4.0

![]() )

and the images are in reasonable

agreement. Additionally, Fig. 2 possibly shows

the arc extending onto larger scales, with its centre on the star and

a projected radius of

)

and the images are in reasonable

agreement. Additionally, Fig. 2 possibly shows

the arc extending onto larger scales, with its centre on the star and

a projected radius of ![]() 11

11

![]() .

.

Summing all frames for the 11.9 ![]() m image obtained with TIMMI2,

including those having shifts introduced by the chopping problem (see

Sect. 3.2), the spatial FWHM of the star is

m image obtained with TIMMI2,

including those having shifts introduced by the chopping problem (see

Sect. 3.2), the spatial FWHM of the star is ![]() 4.7 pixels (0.94

4.7 pixels (0.94

![]() ). When only frames with a shift in

pixels

). When only frames with a shift in

pixels ![]() 1 are considered, this FWHM decreases to

1 are considered, this FWHM decreases to ![]() 3.9 pixels (0.78

3.9 pixels (0.78

![]() ), closer to the FWHM of the standard

stars (i.e. 2.9 pixels; 0.58

), closer to the FWHM of the standard

stars (i.e. 2.9 pixels; 0.58

![]() )

and therefore likely

unresolved. The peaks of PAH emission are smeared out when all the

frames are summed.

)

and therefore likely

unresolved. The peaks of PAH emission are smeared out when all the

frames are summed.

Table 6: Gaussian FWHM of the different objects and emission components studied here (still convolved).

The ISO-SWS spectrum shows the prominent PAH features at 3.3, 6.2,

``7.7'', 11.2, 12.7 and 16.4 ![]() m (Fig. 8). The

strengths of most of these bands are listed in Table 5. The TIMMI2 spectra for the four individual emission

peaks are plotted in Fig. 4. The spectra of the

PAH peaks are very similar, all showing the 8.6, 11.2 and 12.7

m (Fig. 8). The

strengths of most of these bands are listed in Table 5. The TIMMI2 spectra for the four individual emission

peaks are plotted in Fig. 4. The spectra of the

PAH peaks are very similar, all showing the 8.6, 11.2 and 12.7 ![]() m

PAH bands. In the fourth panel of Fig. 4, a

scaled version of the ISO-SWS spectrum is compared to the total

combined TIMMI2 spectrum (i.e. star + PAH components). The higher flux

levels reflect the larger aperture of ISO-SWS and the extent of the

PAH emission. The similar shaped spectrum of the arc and the nearby

peak suggests that the same kind of material is radiating. As

expected, the central star shows an almost featureless spectrum.

m

PAH bands. In the fourth panel of Fig. 4, a

scaled version of the ISO-SWS spectrum is compared to the total

combined TIMMI2 spectrum (i.e. star + PAH components). The higher flux

levels reflect the larger aperture of ISO-SWS and the extent of the

PAH emission. The similar shaped spectrum of the arc and the nearby

peak suggests that the same kind of material is radiating. As

expected, the central star shows an almost featureless spectrum.

4.3 TY CrA

The 3-colour IRAC image shows a nebulous region surrounding TY CrA and a ``bar'' like structure to the South-East (Fig. 1).

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm,clip]{11820f11}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/28/aa11820-09/Timg77.png) |

Figure 9:

15.25 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=8cm]{11820f12}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/28/aa11820-09/Timg78.png) |

Figure 10:

Spatial distribution of IRAS 06084-0611 VLA4 (solid line) and the calibration star (dotted line) from TIMMI2 at 11.22 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

From the VISIR 2D image we were able to decompose the central source

profile into two components (see Sect. 3.3), separated

by ![]() 2.5 pixels (0.32

2.5 pixels (0.32

![]() ). The two spectra extracted

are shown in Fig. 5: a PAH spectrum and an

amorphous silicate spectrum. The PAH spectrum, shown in the panel

labelled PAHs of Fig. 5, clearly shows strong

PAH bands at 8.6, 11.2 and 12.7

). The two spectra extracted

are shown in Fig. 5: a PAH spectrum and an

amorphous silicate spectrum. The PAH spectrum, shown in the panel

labelled PAHs of Fig. 5, clearly shows strong

PAH bands at 8.6, 11.2 and 12.7 ![]() m. Additionally, the shoulder of

the ``7.7''

m. Additionally, the shoulder of

the ``7.7'' ![]() m PAH band at the blue edge of the spectrum and the

minor PAH features at 11.0 and

m PAH band at the blue edge of the spectrum and the

minor PAH features at 11.0 and ![]() 12

12 ![]() m are present. The

ISO-SWS spectrum also shows these PAH bands, in addition to bands at

3.3, 6.2, ``7.7'', and 16.4

m are present. The

ISO-SWS spectrum also shows these PAH bands, in addition to bands at

3.3, 6.2, ``7.7'', and 16.4 ![]() m (Fig. 8). The

strengths of most of these bands are listed in Table 5. The amorphous silicate spectrum peaks near 9.8

m (Fig. 8). The

strengths of most of these bands are listed in Table 5. The amorphous silicate spectrum peaks near 9.8 ![]() m, indicative of the Si-O stretch in amorphous

silicate. Following van Boekel et al. (2005), the ratio of the

silicate feature peak/continuum is

m, indicative of the Si-O stretch in amorphous

silicate. Following van Boekel et al. (2005), the ratio of the

silicate feature peak/continuum is ![]() 3.26 and the 11.3/9.8

3.26 and the 11.3/9.8 ![]() m

ratio

m

ratio ![]() 0.74.

0.74.

The FWHM as a function of wavelength shows that both components are

resolved and extended, Fig. 6. The PAH component

extends over ![]()

![]() (

(![]() 390 AU) and the amorphous

silicate component over

390 AU) and the amorphous

silicate component over ![]()

![]() (

(![]() 130 AU) in the

spectra. On a larger scale, the spatial extent of the emission coming

from TY CrA is studied by constructing a calibrated 2D spectrum. The

different wavelength settings have been shifted, spliced and merged to

form a continuous 2D spectrum. The results are shown in

Fig. 11. Note that close to the blue and red cut-off

wavelengths of the grating, the terrestrial background varies strongly

with ambient conditions and atmospheric corrections are more

difficult. The same holds for the wavelength regions of strong

telluric lines near 9.58, 11.73 and 12.55

130 AU) in the

spectra. On a larger scale, the spatial extent of the emission coming

from TY CrA is studied by constructing a calibrated 2D spectrum. The

different wavelength settings have been shifted, spliced and merged to

form a continuous 2D spectrum. The results are shown in

Fig. 11. Note that close to the blue and red cut-off

wavelengths of the grating, the terrestrial background varies strongly

with ambient conditions and atmospheric corrections are more

difficult. The same holds for the wavelength regions of strong

telluric lines near 9.58, 11.73 and 12.55 ![]() m. Therefore, the

quality of the 2D spectrum is lower in those regions. At

m. Therefore, the

quality of the 2D spectrum is lower in those regions. At

![]() 11

11

![]() from TY CrA, the 11.2

from TY CrA, the 11.2 ![]() m PAH emission

from the ``bar'' to the South-East, is detected. The zoom-in (lower

panel) reveals particularly well the extended nature of the 11.0 and

11.2

m PAH emission

from the ``bar'' to the South-East, is detected. The zoom-in (lower

panel) reveals particularly well the extended nature of the 11.0 and

11.2 ![]() m PAH features.

m PAH features.

Given the extended nature of the mid-IR emission, spectra have been

extracted using the PSF, determined from the 12.2 ![]() m wavelength

setting, as extraction profile at positions along the slit, separated

by half the PSF's FWHM. Zero is at the centre position of the slit,

positions increase into the South-Eastern direction, see

Fig. 1. At each position, the continuum is established by

linear interpolation and subtracted from the PAH bands. For the 8.6

m wavelength

setting, as extraction profile at positions along the slit, separated

by half the PSF's FWHM. Zero is at the centre position of the slit,

positions increase into the South-Eastern direction, see

Fig. 1. At each position, the continuum is established by

linear interpolation and subtracted from the PAH bands. For the 8.6 ![]() m band, the resulting profile is fitted with a single

Lorentzian. The 11.0 and 11.2

m band, the resulting profile is fitted with a single

Lorentzian. The 11.0 and 11.2 ![]() m bands are decoupled by

simultaneously fitting a Gaussian for the 11.0

m bands are decoupled by

simultaneously fitting a Gaussian for the 11.0 ![]() m profile and a

Lorentzian for the 11.2

m profile and a

Lorentzian for the 11.2 ![]() m profile. This combination of

Lorentzians and Gaussians was chosen because it provided the best fit

with respect to the other possible combinations. The centres and

widths of the profiles are allowed to vary marginally. The fit is

assumed to be of intrinsically good quality. Therefore, uncertainties

have been established by multiplying the diagonal co-variance matrix

elements by the reduced

m profile. This combination of

Lorentzians and Gaussians was chosen because it provided the best fit

with respect to the other possible combinations. The centres and

widths of the profiles are allowed to vary marginally. The fit is

assumed to be of intrinsically good quality. Therefore, uncertainties

have been established by multiplying the diagonal co-variance matrix

elements by the reduced ![]() .

We expect that relative variations

along the slit are not much affected by systematic uncertainties

introduced by the fitting procedure. The strength of the

dust/continuum at each position is determined by integrating the

emission between 9.7 and 10.6

.

We expect that relative variations

along the slit are not much affected by systematic uncertainties

introduced by the fitting procedure. The strength of the

dust/continuum at each position is determined by integrating the

emission between 9.7 and 10.6 ![]() m. Here no error analysis has been

performed. The results are presented in Fig. 12.

m. Here no error analysis has been

performed. The results are presented in Fig. 12.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm]{11820f13} \includegraphics[width=9cm]{11820f14}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/28/aa11820-09/Timg82.png) |

Figure 11:

2D spectral image of TY CrA. Top: entire field of view (note the 11.2 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=7.1cm]{11820f15} \includegraphics[widt...

...ics[width=7.1cm]{11820f17} \includegraphics[width=7.1cm]{11820f18}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/28/aa11820-09/Timg83.png) |

Figure 12:

Integrated band strength as a function of position for the 8.6, 11.0 and 11.2 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

The spatial distribution of the individual components mostly differ

from each other, but do also show some common characteristics. All

spatial profiles show a higher flux level after the peak than before

and an asymmetric flank to the right of it. The 8.6 and 11.0 ![]() m

profiles are double peaked, whereas the 11.2

m

profiles are double peaked, whereas the 11.2 ![]() m and continuum

profiles are single peaked. Individual peaks show a slight

displacement from each other, traced out by the dashed lines in

Fig. 12. The (non-Gaussian) FWHM varies as

4.8

m and continuum

profiles are single peaked. Individual peaks show a slight

displacement from each other, traced out by the dashed lines in

Fig. 12. The (non-Gaussian) FWHM varies as

4.8

![]() ,

2.9

,

2.9

![]() ,

3.8

,

3.8

![]() ,

2.7

,

2.7

![]() and 1.4

and 1.4

![]() for the 8.6, 11.0, 11.2,

8.2

for the 8.6, 11.0, 11.2,

8.2 ![]() m and continuum profiles, respectively. These are in

reasonable agreement with Fig. 6 (specially

considering that the double peaked and asymmetric shape of the

profiles are not well defined by a single Gaussian FWHM). The 11.2

m and continuum profiles, respectively. These are in

reasonable agreement with Fig. 6 (specially

considering that the double peaked and asymmetric shape of the

profiles are not well defined by a single Gaussian FWHM). The 11.2 ![]() m flux is particularly interesting in that it stays at a

significant higher flux after peaking and coming down at

m flux is particularly interesting in that it stays at a

significant higher flux after peaking and coming down at

![]() 5

5

![]() ,

and rising again to form a double peak

around 12.5

,

and rising again to form a double peak

around 12.5

![]() ,

the position of the TY CrA ``bar''.

,

the position of the TY CrA ``bar''.

The varying 11.0/11.2 ![]() m band strength ratio as a function of

position is taken and presented in Fig. 13. The

ratio rises steeply and peaks around 2

m band strength ratio as a function of

position is taken and presented in Fig. 13. The

ratio rises steeply and peaks around 2

![]() ,

after which

it drops sharply and continues dropping steadily until reaching zero

around 7

,

after which

it drops sharply and continues dropping steadily until reaching zero

around 7

![]() .

The interpretation of these spatial

distributions will be addressed in Sect. 5.

.

The interpretation of these spatial

distributions will be addressed in Sect. 5.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=9cm,clip]{11820f19}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/28/aa11820-09/Timg84.png) |

Figure 13:

11.0/11.2 |

| Open with DEXTER | |

4.4 HD 176386

The 3-colour IRAC image presented in Fig. 1 shows a

nebulous region surrounding HD 176386. The 8.0 ![]() m IRAC contours are

in good agreement with the VISIR K-band contours.

m IRAC contours are

in good agreement with the VISIR K-band contours.

Position 2 is a star identified as CCDM J19017-3653B; its featureless

spectrum is not shown and/or discussed here. The spectrum of Position 1, shown in Fig. 7, has some ozone

residuals. However, an amorphous silicate feature can clearly be

seen. Following van Boekel et al. (2005), we find a value of about

2.47 for the peak/continuum ratio, and about 1 for the 11.3/9.8 ![]() m

ratio.

m

ratio.

Concerning the extent of the emission, Position 1 and Position 2 are

not resolved with VISIR in spectroscopy. On the K-band acquisition

image, both sources have a FWHM of about 0.52

![]() (68 AU). Due to the unavailability of a K-band image of a point source calibrator we are unable to state whether the source is resolved. With spectroscopy, we derive an upper limit of 0.3

(68 AU). Due to the unavailability of a K-band image of a point source calibrator we are unable to state whether the source is resolved. With spectroscopy, we derive an upper limit of 0.3

![]() (40 AU), which is the FWHM of the calibrator.

(40 AU), which is the FWHM of the calibrator.

5 Discussion and astronomical implications

5.1 Silicate dust

The shape of the silicate feature is a measure of the amount of

processing that the material has undergone

(Bouwman et al. 2001). van Boekel et al. (2005) show that the

amount of crystallisation can be obtained from the 11.3/9.8 ![]() m

peak ratio. The peak/continuum ratio measures the feature's strength

and correlates with the 11.3/9.8

m

peak ratio. The peak/continuum ratio measures the feature's strength

and correlates with the 11.3/9.8 ![]() m peak ratio. This correlation

is interpreted as a relation between grain growth and crystallisation,

which assesses the amount of processing the material has

undergone. The values found for TY CrA and HD 176386 fall on the

correlation these authors present. Both these sources show silicate

emission originating from a disk; this is not the case for IRAS

06084-0611 VLA4 and CD-42 11721. The resulting 11.3/9.8

m peak ratio. This correlation

is interpreted as a relation between grain growth and crystallisation,

which assesses the amount of processing the material has

undergone. The values found for TY CrA and HD 176386 fall on the

correlation these authors present. Both these sources show silicate

emission originating from a disk; this is not the case for IRAS

06084-0611 VLA4 and CD-42 11721. The resulting 11.3/9.8 ![]() m peak

ratios indicate that TY CrA and HD 176386 have slightly processed

dust. The slightly higher value found for HD 176386 indicates more

extensive processing. Assuming similar systems, this might suggest

that HD 176386 is older. However, this is not really justified given

that TY CrA is a complex multiple star system. Furthermore, the

detailed evolutionary scenario involved in dust settling, grain growth

and crystallisation is not yet fully understood. A mineralogical

decomposition, which is beyond the scope of this paper, might provide

further insight.

m peak

ratios indicate that TY CrA and HD 176386 have slightly processed

dust. The slightly higher value found for HD 176386 indicates more

extensive processing. Assuming similar systems, this might suggest

that HD 176386 is older. However, this is not really justified given

that TY CrA is a complex multiple star system. Furthermore, the

detailed evolutionary scenario involved in dust settling, grain growth

and crystallisation is not yet fully understood. A mineralogical

decomposition, which is beyond the scope of this paper, might provide

further insight.

5.2 PAHs

Three out of the four Herbig Ae/Be stars studied here show PAH

emission. The PAH profiles peak near 6.2, 7.6, and 11.2 ![]() m,

referred to by Peeters et al. (2003,2002a) as

class A, and are consistent with non-isolated Herbig Ae/Be stars

(Peeters et al. 2002a). Class B profiles, with the PAH bands

peaking closer to 6.3, 7.8 and 11.3

m,

referred to by Peeters et al. (2003,2002a) as

class A, and are consistent with non-isolated Herbig Ae/Be stars

(Peeters et al. 2002a). Class B profiles, with the PAH bands

peaking closer to 6.3, 7.8 and 11.3 ![]() m, are associated with

isolated Herbig Ae/Be stars and are thought to probe directly the

circumstellar disk (Van Kerckhoven 2002; Boersma et al. 2008). Using the long-slit data, the measured extent

(FWHM) of the PAH emission is

m, are associated with

isolated Herbig Ae/Be stars and are thought to probe directly the

circumstellar disk (Van Kerckhoven 2002; Boersma et al. 2008). Using the long-slit data, the measured extent

(FWHM) of the PAH emission is ![]() 2

2

![]() (2100 AU) for

VLA4 in IRAS06084-0611,

(2100 AU) for

VLA4 in IRAS06084-0611, ![]() 1

1

![]() and

5

and

5

![]() (400 AU and 2000 AU, respectively) for the patch

near the star and arc components in CD-42 11721, and

(400 AU and 2000 AU, respectively) for the patch

near the star and arc components in CD-42 11721, and

![]() 3

3

![]() (390 AU) for TY CrA. Given these sizes, it is

clear that for VLA4 and CD-42 11721, the PAH emission from the

surroundings is dominating the spectrum. For TY CrA, the emission

associated with the central object likely originates from a large disk

(scale size

(390 AU) for TY CrA. Given these sizes, it is

clear that for VLA4 and CD-42 11721, the PAH emission from the

surroundings is dominating the spectrum. For TY CrA, the emission

associated with the central object likely originates from a large disk

(scale size ![]() 170 AU), while the more extended emission such, as

the bar to the South-East, represents surrounding molecular cloud

material set aglow by the radiation from the Herbig Ae/Be star.

170 AU), while the more extended emission such, as

the bar to the South-East, represents surrounding molecular cloud

material set aglow by the radiation from the Herbig Ae/Be star.

![\begin{figure}

\par\includegraphics[width=16.5cm]{11820f20}

\end{figure}](/articles/aa/full_html/2009/28/aa11820-09/Timg85.png) |

Figure 14: Cartoon of the proposed morphology for TY CrA depicting the different emission zones. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

5.3 Morphology

For HD 176386 (Position 1) we detect only silicate emission. This

emission is not spatially resolved and therefore, given the scale,

likely linked to a disk. The absence of PAH emission suggests a

self-shadowed Group II disk. The fact that we do not detect any PAH

emission, even at significant distances away from HD 176386, but do see

it on the IRAC images is due to the limited sensitivity of VISIR

compared to Spitzer. The estimated upper limit of the PAH emission

from the IRAC 8.0 ![]() m image is

m image is

![]() Jy

(IRAC

Jy

(IRAC

![]() [MJy/sr]

[MJy/sr] ![]() PSF

PSF

![]() [

[

![]() ]

]

![]() pixel

pixel

![]() [

[

![]() ]

]

![]()

![]() sr),

which is similar to the noise (see

Fig. 7). Siebenmorgen et al. (2000),

using ISOCAM, do detect PAH emission from HD 176386 and also from a

nearby ``bar''-like component. Due to the orientation of the VISIR slit,

the ``bar''-like component is not present in our data. Given the large

aperture of ISOCAM, the PAH emission Siebenmorgen et al. (2000) see

must be originating from the surrounding area.

sr),

which is similar to the noise (see

Fig. 7). Siebenmorgen et al. (2000),

using ISOCAM, do detect PAH emission from HD 176386 and also from a

nearby ``bar''-like component. Due to the orientation of the VISIR slit,

the ``bar''-like component is not present in our data. Given the large

aperture of ISOCAM, the PAH emission Siebenmorgen et al. (2000) see

must be originating from the surrounding area.

The difference in spatial distribution of the 8.6, 11.0 and 11.2 ![]() m features in the spectra of TY CrA (Fig. 12) point towards three distinct carriers

for these bands. The 8.6

m features in the spectra of TY CrA (Fig. 12) point towards three distinct carriers

for these bands. The 8.6 ![]() m PAH band has recently been attributed

to very large, compact and highly symmetric PAH cations (and

anions, Bauschlicher et al. 2008). The 11.0

m PAH band has recently been attributed

to very large, compact and highly symmetric PAH cations (and

anions, Bauschlicher et al. 2008). The 11.0 ![]() m band has been

assigned to the out-of-plane bending mode in solo C-H cationic PAHs,

while the 11.2

m band has been

assigned to the out-of-plane bending mode in solo C-H cationic PAHs,

while the 11.2 ![]() m band has been assigned to the out-of-plane

bending mode in solo C-H of neutral PAHs (Hudgins & Allamandola 1999; Hony et al. 2001). Although, recently this assignments has met

some opposition (Povich et al. 2007).

m band has been assigned to the out-of-plane

bending mode in solo C-H of neutral PAHs (Hudgins & Allamandola 1999; Hony et al. 2001). Although, recently this assignments has met

some opposition (Povich et al. 2007).

Attributing the PAH emission originating from a flaring disk, the

spatial distribution can be explained within the context of these

assignments. The proposed morphology of TY CrA is presented in

Fig. 14, where the quaternary star system is

surrounded by a single flaring disk. An inner gap beyond the orbit of

the fourth stellar component is inferred from the double peaked

spatial profiles of the 8.6 and 11.0 ![]() m PAH bands. The 11.0/11.2 ratio - and thus the ions to neutrals - peaks to the right, away from

the star and only to one side. This can be understood in the context

of a flaring disk seen under an angle, where the near side is

foreshortened and therefore unobserved. The 11.2

m PAH bands. The 11.0/11.2 ratio - and thus the ions to neutrals - peaks to the right, away from

the star and only to one side. This can be understood in the context

of a flaring disk seen under an angle, where the near side is

foreshortened and therefore unobserved. The 11.2 ![]() m emission

originates from the bulk of the disk. Both the neutral and

intrinsically stronger nature of the 11.2

m emission

originates from the bulk of the disk. Both the neutral and

intrinsically stronger nature of the 11.2 ![]() m PAH band allows for

this. The emission can even be traced all the way down to the TY CrA

``bar'', which we suspect to be the limb-brightened edge of a bowl where

the photo dissociation front is eating its way into the molecular

cloud. This in-between material is the non-limb brightened inside of

the bowl. The PAHs will be more easily ionised close to the star. In

agreement, the 8.6 and 11.0

m PAH band allows for

this. The emission can even be traced all the way down to the TY CrA

``bar'', which we suspect to be the limb-brightened edge of a bowl where

the photo dissociation front is eating its way into the molecular

cloud. This in-between material is the non-limb brightened inside of

the bowl. The PAHs will be more easily ionised close to the star. In

agreement, the 8.6 and 11.0 ![]() m PAH band emission is originating

from a narrow region at the inner disk. Furthermore, recent analysis

by Bauschlicher et al. (2008) suggest larger PAHs dominating the 11.0

m PAH band emission is originating

from a narrow region at the inner disk. Furthermore, recent analysis

by Bauschlicher et al. (2008) suggest larger PAHs dominating the 11.0 ![]() m emission than those dominating that at 8.6

m emission than those dominating that at 8.6 ![]() m. Hence, the

11.0

m. Hence, the

11.0 ![]() m emission should be more confined since only large PAHs are

able to survive close to the star, and this is what is

seen. Geers et al. (2007) measured the radial extent of the 3.3

m emission should be more confined since only large PAHs are

able to survive close to the star, and this is what is

seen. Geers et al. (2007) measured the radial extent of the 3.3 ![]() m PAH band emission to be 54 AU, which fits well within the

proposed morphology.

m PAH band emission to be 54 AU, which fits well within the

proposed morphology.

Interestingly, the fourth stellar component is separated

![]() 0.3

0.3

![]() (40 AU) from the central tertiary system,

which is similar to the separation of the dust and PAH component in

the VISIR spectrum. It is tempting to speculate that the fourth

companion, at a projected distance of 40 AU, is dynamically related to

the inferred large inner radius of the circumquartery disk. That would

imply that the actual distance of this star is some 70 AU from TY CrA

itself. It is tempting to conclude that the fourth companion is

inducing the dust emission. However, at this distance, the central

Herbig Ae/Be star still dominates the dust temperature (

(40 AU) from the central tertiary system,

which is similar to the separation of the dust and PAH component in

the VISIR spectrum. It is tempting to speculate that the fourth

companion, at a projected distance of 40 AU, is dynamically related to

the inferred large inner radius of the circumquartery disk. That would

imply that the actual distance of this star is some 70 AU from TY CrA

itself. It is tempting to conclude that the fourth companion is

inducing the dust emission. However, at this distance, the central

Herbig Ae/Be star still dominates the dust temperature (![]() 300 Kelvin, assuming LTE and an emissivity of 0.05). Furthermore, the M4 star is unable to heat the dust up to the scale of the observed distance (

300 Kelvin, assuming LTE and an emissivity of 0.05). Furthermore, the M4 star is unable to heat the dust up to the scale of the observed distance (![]() 65 AU). Therefore, the central Herbig Ae/Be star must

be responsible for heating the dust.

65 AU). Therefore, the central Herbig Ae/Be star must

be responsible for heating the dust.

5.4 Band strengths

Following Hony et al. (2001) and Galliano et al. (2008),

we have investigated the correlations between the strength of the PAH

bands presented in Table 5. The 6.2/11.2 ![]() m band

shows little variations, implying very similar physical conditions. In

contrast, other studies (Lebouteiller et al. 2008; Galliano et al. 2008) report little variation in the 7.7/6.2 ratios

with a typical value of 2.5, where most of the Herbig stars fall

(Fig. 15). There is no indication that this ratio

correlates with object type (e.g. isolated Herbig stars versus

reflection nebula). The origin of this variation may well provide

interesting insight in the chemical make-up of the emitting PAHs, for example the difference in photochemical activity.

m band

shows little variations, implying very similar physical conditions. In

contrast, other studies (Lebouteiller et al. 2008; Galliano et al. 2008) report little variation in the 7.7/6.2 ratios

with a typical value of 2.5, where most of the Herbig stars fall

(Fig. 15). There is no indication that this ratio

correlates with object type (e.g. isolated Herbig stars versus

reflection nebula). The origin of this variation may well provide

interesting insight in the chemical make-up of the emitting PAHs, for example the difference in photochemical activity.

| |

Figure 15:

Left:

|

| Open with DEXTER | |

The 11.2/6.2 versus 7.7/6.2 ![]() m band strength ratios have been

plotted in Fig. 15. Along with the ratios for two

reflection nebulae, NGC 7023 and NGC 2023, and two non-isolated Herbig

Ae/Be stars, HD 97048 and BD+40 4124 (Hony et al. 2001; van Diedenhoven et al. 2004). These band ratios may be

influenced by the physical conditions (e.g. charge) or by the chemical

history (e.g. difference in illuminating spectrum may control

photochemistry).

m band strength ratios have been

plotted in Fig. 15. Along with the ratios for two

reflection nebulae, NGC 7023 and NGC 2023, and two non-isolated Herbig

Ae/Be stars, HD 97048 and BD+40 4124 (Hony et al. 2001; van Diedenhoven et al. 2004). These band ratios may be

influenced by the physical conditions (e.g. charge) or by the chemical

history (e.g. difference in illuminating spectrum may control

photochemistry).

The ratio of the C-C to C-H modes (6.2/11.2 ![]() m band strength

ratio) is generally thought to reflect the degree of ionisation of the

emitting PAHs (Tielens 2008). Typically, these ratios

vary with a factor of

m band strength

ratio) is generally thought to reflect the degree of ionisation of the

emitting PAHs (Tielens 2008). Typically, these ratios

vary with a factor of ![]() 5 between sources and within sources

(Galliano et al. 2008). However as a class, these Herbig Ae/Be

stars reveal very similar values (Fig. 15), indicating

that the physical conditions (e.g. G0/

5 between sources and within sources

(Galliano et al. 2008). However as a class, these Herbig Ae/Be

stars reveal very similar values (Fig. 15), indicating

that the physical conditions (e.g. G0/![]() ,

where G0 is

the UV intensity and

,

where G0 is

the UV intensity and ![]() the electron density) in the emission

zone are much the same. Curiously in the same data, in terms of the

7.7/6.2 versus 11.2/6.2 band ratios, a larger variation is apparent

(Fig. 15). In particular, the sources HD 97048 and NGC 2023

have a 7.7/6.2 ratio which is almost a factor 2 higher than in the

other sources.

the electron density) in the emission

zone are much the same. Curiously in the same data, in terms of the

7.7/6.2 versus 11.2/6.2 band ratios, a larger variation is apparent

(Fig. 15). In particular, the sources HD 97048 and NGC 2023

have a 7.7/6.2 ratio which is almost a factor 2 higher than in the

other sources.

5.5 PAH emission from Herbig A vs Herbig B stars

The (proto-) stellar mass determines the total luminosity and the number of ionising photons. Heavier stars, and therefor more luminous, should be able to light up more of their surroundings than there less massive counterparts. At the same time the number of available ionising photons is larger for the heavier stars. Alterations to the silicates and PAH family, driven by photo-chemistry, should be sensitive to the spectral shape of the irradiating source and show up as variations in the band shapes.

Herbig B stars are more luminous analogs of the Herbig A stars. The

earliest B star, which are powering prominent reflection nebulae

(e.g. NGC 2023 and NGC 7023), have about a hundred times higher

luminosity at 6 eV than the later type Herbig B stars (e.g. TY CrA),

while mid A stars are another 100 times weaker yet. Hence, typical

spatial scales for the PAH emission will be ten times larger for early

B stars than later Herbig B stars and a hundred times larger than mid

Herbig A stars. Indeed, for reflection nebula spatial scales for PAH

emission are ![]() 0.1 pc, whereas for Herbig A stars only the

circumstellar disk re-radiates PAH emission (

0.1 pc, whereas for Herbig A stars only the

circumstellar disk re-radiates PAH emission (![]() 200 AU). In this

context, IRAS 06084-0611 VLA4 and CD-42 11721 are placed in the RNe

class and indeed their emission scale is large and consistent with

surrounding molecular cloud material illuminated by the star, but not

associated with it. TY CrA is possibly a transition object between the

Herbig A and genuine reflection nebulae. The reflection nebula

characteristics dominate on larger scales, while the disk and envelope

of TY CrA dominate on smaller scales.

200 AU). In this

context, IRAS 06084-0611 VLA4 and CD-42 11721 are placed in the RNe

class and indeed their emission scale is large and consistent with

surrounding molecular cloud material illuminated by the star, but not

associated with it. TY CrA is possibly a transition object between the

Herbig A and genuine reflection nebulae. The reflection nebula

characteristics dominate on larger scales, while the disk and envelope

of TY CrA dominate on smaller scales.

6 Summary and conclusions

The mid-IR images and spectra of four Herbig Ae/Be stars have been investigated in order to study the variation in the dust and PAH characteristics and hence, the processing of material in star and planet forming environments. We find evidence for large scale structure and extended emission in all four sources. Except for HD 176386, all sources show PAH emission in their TIMMI2/VISIR spectrum. Both HD 176386 and TY CrA show silicate emission. The scales on which these dust components emit varies significantly. The PAHs are detected from 390 AU up to 5700 AU. The silicate emission observed in HD 176386 is spatially unresolved, providing an upper limit of 40 AU. In TY CrA, the silicates are seen up to 130 AU. The extent of the continuum emission is similar to that of the silicates.

Following Hony et al. (2001) and Galliano et al. (2008),

we have investigated the correlation of the strength of the PAH

bands. The 6.2/11.2 ![]() m PAH band ratio shows little variation,

implying very similar physical conditions. In contrast to previous

studies, we find more variation in the 7.7/6.2

m PAH band ratio shows little variation,

implying very similar physical conditions. In contrast to previous

studies, we find more variation in the 7.7/6.2 ![]() m band strength

ratio within our sample. However there does not seem to be a

relationship with object type.

m band strength

ratio within our sample. However there does not seem to be a

relationship with object type.

For the individual objects we infer the following:

- IRAS 06084-0611: The two bright IR sources VLA1 and VLA4 have

been studied, where the spectrum of VLA1 resembles that of a YSO. For

this source, we were able to deduce a CO

temperature of 100-110 K, consistent with an embedded YSO. VLA4 shows a far richer

spectrum. The PAH and continuum emission is extended on scales of 2800

and 2200 AU, respectively.

temperature of 100-110 K, consistent with an embedded YSO. VLA4 shows a far richer

spectrum. The PAH and continuum emission is extended on scales of 2800

and 2200 AU, respectively.

- CD-42 11721: We find evidence for several distinct emission

components. First, there is evidence for a PAH peak close to the

star. Second, an arc of PAH emission partially encompasses the star

and the nearby emission peak (``patch''). The nearby PAH peak and PAH

arc have both an emission scale of 1900 AU.

- TY CrA: Our analysis was particularly successful given our

ability to separate an amorphous silicate and PAH spectrum. The

silicates and PAHs are seen up to scales of 130 and 390 AU,

respectively. Extracting spectra separated 1 PSF over the source

profile allowed us to infer the morphology of TY CrA. The TY CrA

system is seen under an angle and includes a large circum-quaternary

disk with a inner gap of

70 AU. Analyses of the 10

70 AU. Analyses of the 10  m

feature given the paradigm of van Boekel et al. (2005) suggests the

presence of rather pristine silicates.

m

feature given the paradigm of van Boekel et al. (2005) suggests the

presence of rather pristine silicates.

- HD 176386: Spectra of two positions were acquired. One of them

was identified as CCDM J19017-3653B and has a stellar spectrum. At the

other position, a 10

m feature was detected. Following the

analysis of van Boekel et al. (2005), pristine silicate were

identified, but more processed than those of TY CrA. The absence of

PAH emission is consistent with a self-shadowed Group II disk.

m feature was detected. Following the

analysis of van Boekel et al. (2005), pristine silicate were

identified, but more processed than those of TY CrA. The absence of

PAH emission is consistent with a self-shadowed Group II disk.

A consistent large sample of high-spatial observations of reflection nebula and Herbig Ae/Be stars will help pin down the validity of our proposed connection between Herbig A and B stars and reflection nebulae and determine how smooth the transitions actually are. Such a study could form the basis for our understanding of the evolution of PAHs in regions of star and planet formation.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the staff at the European Southern Observatory in La Silla and Paranal for assisting with the observations. We would also like to extend our gratitude to Mario van den Ancker for providing an overview of the stellar data. We also thank Carsten Dominik for insights concerning disk geometry.

References

- Allamandola, L. J., Tielens, G. G. M., & Barker, J. R. 1989, ApJS, 71, 733 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Bauschlicher, Jr., C. W., Peeters, E., & Allamandola, L. J. 2008, ApJ, 678, 316 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Boersma, C., Bouwman, J., Lahuis, F., et al. 2008, A&A, 484, 241 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences]

- Boogert, A. C. A. 1999, Ph.D. Thesis, AA (In the text)

- Borges Fernandes, M., Kraus, M., Lorenz Martins, S., & de Araújo, F. X. 2007, MNRAS, 377, 1343 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] (In the text)

- Bouwman, J., de Koter, A., van den Ancker, M. E., & Waters, L. B. F. M. 2000, A&A, 360, 213 [NASA ADS] (In the text)

- Bouwman, J., Meeus, G., de Koter, A., et al. 2001, A&A, 375, 950 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)

- Casey, B. W., Mathieu, R. D., Vaz, L. P. R., Andersen, J., & Suntzeff, N. B. 1998, AJ, 115, 1617 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef]

- Chauvin, G., Lagrange, A.-M., Beust, H., et al. 2003, A&A, 406, L51 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] (In the text)