| Issue |

A&A

Volume 576, April 2015

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A60 | |

| Number of page(s) | 19 | |

| Section | Planets and planetary systems | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201424278 | |

| Published online | 27 March 2015 | |

Online material

Appendix A: Binary granular mixtures

The strong dichotomy between sizes of chondrules and matrix particles suggests the treatment of the chondritic granular mixture as a binary mixture of two granular components with significantly different sizes. The two components each are idealized as mono-sized. This case has been studied in powder technology and some general results are available (see e.g. Fiske et al. 1994,and references therein). Here we give a simplified treatment appropriate for chondritic material.

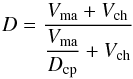

We denote the diameters of the small and large components (matrix and chondrules) as

dma and dch,

respectively, and define the size parameter

![]() (A.1)For all known meteoritic classes this size

parameter is well above the value of α ≳ 7 above which the small particles easily fit

into the interstitials between the large particles. In fact, the value of

α is at

least 102 and

probably above 103 at the early stages of planetesimal evolution before

Ostwald ripening of the matrix particulates. Then also “wall effects” are completely

negligible where the packing of matrix particles immediately adjacent to a large

particle is somewhat less dense than where small particles are only surrounded by small

particles. This allows us to treat the chondritic granular mixture as one of two

different cases:

(A.1)For all known meteoritic classes this size

parameter is well above the value of α ≳ 7 above which the small particles easily fit

into the interstitials between the large particles. In fact, the value of

α is at

least 102 and

probably above 103 at the early stages of planetesimal evolution before

Ostwald ripening of the matrix particulates. Then also “wall effects” are completely

negligible where the packing of matrix particles immediately adjacent to a large

particle is somewhat less dense than where small particles are only surrounded by small

particles. This allows us to treat the chondritic granular mixture as one of two

different cases:

-

Chondrule-dominated material. The chondrules form a closest packing and the matrix material partially or completely fills the pore space between the closely packed chondrules.

-

Matrix-dominated material. The matrix forms a close packing and rare chondrules are interspersed into the matrix material.

First consider the chondrule-dominated material. A volume V may be filled with

chondrules. The fraction of V filled by chondrules is denoted as

![]() (A.2)where Vch is the

total volume of all chondrules in V. We assume that the chondrules form a closest

packing such that the chondrules are immobile in this packing. We denote the

corresponding value of D as Dcp, which would typically be equal to

≈0.64 for a random closest

packing of spheres. The volume of interstitials (pores) between the chondrules is

(A.2)where Vch is the

total volume of all chondrules in V. We assume that the chondrules form a closest

packing such that the chondrules are immobile in this packing. We denote the

corresponding value of D as Dcp, which would typically be equal to

≈0.64 for a random closest

packing of spheres. The volume of interstitials (pores) between the chondrules is

![]() (A.3)where φ = 1 −

D is the porosity.

(A.3)where φ = 1 −

D is the porosity.

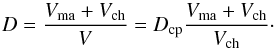

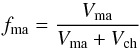

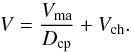

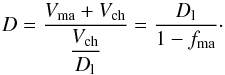

Now we assume that we have given volumes Vch and Vma of

chondrule and matrix material, where the matrix material at most fills the voids between

the chondrules. These volumes refer to the true volume filled by the corresponding

materials and does not include the voids between the particles. The total volume filled

by the granular material is determined by the volume of the chondrules and the void

space between them (which, however, is not empty in our case but is partially filled

with matrix). This volume is  (A.4)The volume filled by matrix and chondrule

material is Vma +

Vch such that the packing fraction of

the mixture is

(A.4)The volume filled by matrix and chondrule

material is Vma +

Vch such that the packing fraction of

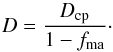

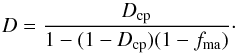

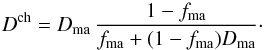

the mixture is  (A.5)We define by

(A.5)We define by  (A.6)the volume fraction of matrix to total

material. With this we can write

(A.6)the volume fraction of matrix to total

material. With this we can write  (A.7)This is the effective filling factor of the

chondrule-matrix mixture in the chondrule-dominated case.

(A.7)This is the effective filling factor of the

chondrule-matrix mixture in the chondrule-dominated case.

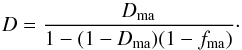

Next we consider the matrix-dominated case. The volume filled by the matrix inclusive

the void space between matrix particles is Vma/Dcp

where it is assumed that the filling factor Dcp of the porous matrix material is

the same as just before. The total volume filled by matrix and chondrules is

(A.8)The filling factor of the matrix-chondrule

mixture is

(A.8)The filling factor of the matrix-chondrule

mixture is  (A.9)and with definition (A.6) of the matrix volume fraction we

obtain

(A.9)and with definition (A.6) of the matrix volume fraction we

obtain (A.10)This is the effective filling factor of the

chondrule-matrix mixture in the matrix-dominated case.

(A.10)This is the effective filling factor of the

chondrule-matrix mixture in the matrix-dominated case.

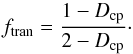

At the limit between the two cases the results for the filling factors corresponding to

the two cases have to equal each other. From this one finds a matrix volume fraction at

the transition of  (A.11)The filling factor takes at the transition

its maximum which equals

(A.11)The filling factor takes at the transition

its maximum which equals ![]() (A.12)In terms of the porosity (which is minimum

if D is

maximum) this takes the obvious form

(A.12)In terms of the porosity (which is minimum

if D is

maximum) this takes the obvious form

![]() (A.13)If it is assumed that the chondrules are

equal sized spheres, the filling factor for the random closest packing is

Dcp ≈

0.64 (e.g. Onoda & Liniger

1990; Jaeger & Nagel 1992). The

random loosest packing of spheres where the particles just resist to small external

forces has a filling factor of Dcp ≈ 0.56 (e.g. Onoda & Liniger 1990; Jaeger

& Nagel 1992; Güttler et al. 2009).

Figure A.1 shows the variation of the effective

porosity of the chondrule-matrix mixture with matrix fraction for these two cases and

Table A.1 gives some numerical values. In

principle the initial structure of the chondritic material could be somewhere in between

these two cases. Because during the growth of planetesimals by collisions with other

planetesimals the surface material is permanently gardened, we assume that the filling

factor corresponds to the closest random packing as in experiments this kind of packing

is the outcome after vigorous stirring and shaking of a granular material.

(A.13)If it is assumed that the chondrules are

equal sized spheres, the filling factor for the random closest packing is

Dcp ≈

0.64 (e.g. Onoda & Liniger

1990; Jaeger & Nagel 1992). The

random loosest packing of spheres where the particles just resist to small external

forces has a filling factor of Dcp ≈ 0.56 (e.g. Onoda & Liniger 1990; Jaeger

& Nagel 1992; Güttler et al. 2009).

Figure A.1 shows the variation of the effective

porosity of the chondrule-matrix mixture with matrix fraction for these two cases and

Table A.1 gives some numerical values. In

principle the initial structure of the chondritic material could be somewhere in between

these two cases. Because during the growth of planetesimals by collisions with other

planetesimals the surface material is permanently gardened, we assume that the filling

factor corresponds to the closest random packing as in experiments this kind of packing

is the outcome after vigorous stirring and shaking of a granular material.

|

Fig. A.1

Variation of effective porosity of a binary granular mixture of matrix and chondrules with volume fraction (with respect to matter-filled volume) of matrix. Full line: the case of random closest packing of spheres, corresponding to Dcp = 0.64. Dashed line: the case of loosest close packing of spheres, corresponding to Dcp = 0.56. Dotted line: the case of random closest packing of the matrix material where the interspersed chondrules are more densely packed than in the loose close packing. |

| Open with DEXTER | |

Some characteristic numbers for a chondrule-matrix mixture.

The experimental results shown in Fiske et al. (1994) confirm that the equations for the effective packing fraction given above are good approximations for the properties of real binary granular media.

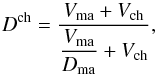

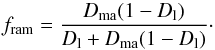

In the case of matrix-dominated material one has also to observe the filling factor of

the chondrules interspersed in the matrix ground mass. This filling factor is defined as

(A.14)where Dma is the

filling factor of the matrix ground mass. Eliminating Vma by means

of Eq. (A.6) results in

(A.14)where Dma is the

filling factor of the matrix ground mass. Eliminating Vma by means

of Eq. (A.6) results in  (A.15)This filling factor equals the loose random

closest packing Dl ≈ 0.56 where the packing of

chondrules becomes immobile for a value of the volume fraction of matrix material

(A.15)This filling factor equals the loose random

closest packing Dl ≈ 0.56 where the packing of

chondrules becomes immobile for a value of the volume fraction of matrix material

(A.16)In the incompacted state the filling factor

of the porous matrix component should equal the closest random packing Dcp ≈ 0.64.

The value of fram for this case is shown in Table

A.1. For lower filling factors the effective

filling factor of the matrix-chondrule mixture is

(A.16)In the incompacted state the filling factor

of the porous matrix component should equal the closest random packing Dcp ≈ 0.64.

The value of fram for this case is shown in Table

A.1. For lower filling factors the effective

filling factor of the matrix-chondrule mixture is

(A.17)This is also shown in Fig. A.1. For f below the limit value of ftran

corresponding to Dcp = Dl

the packing fraction coincides with the packing fraction of the loose close packing.

This type of packing in principle is unstable because the porous matrix does not

completely fill the voids between the chondrules. By shaking it would make a transition

to the case of random closest packing of both the chondrules and the matrix.

(A.17)This is also shown in Fig. A.1. For f below the limit value of ftran

corresponding to Dcp = Dl

the packing fraction coincides with the packing fraction of the loose close packing.

This type of packing in principle is unstable because the porous matrix does not

completely fill the voids between the chondrules. By shaking it would make a transition

to the case of random closest packing of both the chondrules and the matrix.

Appendix B: Hot isostatic pressing of a binary granular mixture

For hot isostatic pressing of the chondritic binary mixture one has to observe that sintering of the pure matrix material because of the smallness of the particles occurs at lower temperature by surface diffusion than sintering of the pure chondrule material by dislocation creep. This has to be observed in the modelling of the sintering process.

First we consider the case of a chondrule-dominated material. Since the matrix does not completely fill the voids between the chondrules if the matrix fraction is less than the value given by Eq. (A.11), the pressure loading rests on the contacts between the chondrules. The matrix is essentially only subject to the low gas pressure and sintering of the matrix is mainly driven by surface tension. Though the filling factor of the initially porous matrix material increases up to unity during sintering of the matrix material, the effective filling factor of the matrix-chondrule mixture given by Eq. (A.7) does not change. The only thing one has to do is to use this effective packing fraction and not Dcp as the initial value if we solve the differential equation for the time evolution of the filling factor of the chondrules.

In the case of matrix-dominated material we have to discriminate between two different

cases that are related to the filling factor of the chondrules interspersed in the

matrix ground mass. During sintering of the matrix the filling factor Dma increases

from the initial value Dcp for the closest packing of the

non-sintered material to a maximum value of unity. At the same time Dch, given by

Eq. (A.15), also increases. This filling

factor then could approach the value corresponding to the loose random closest packing

Dl ≈

0.56 where the packing of chondrules becomes immobile. If we assume

that the chondrule material is more rigid than the matrix material, the sintering of

matrix material beyond this point cannot increase the effective packing fraction of the

matrix-chondrule mixture. The further sintering of the matrix occurs under zero pressure

conditions because the still porous matrix material then incompletely fills the space

between the chondrules and therefore partially detaches from them. The condition that

Dch<Dl

at complete sintering of the matrix (Dma = 1) is

![]() (B.1)The value of this limit is higher than the

limit fram, defined by Eq. (A.16), where the filling factor of the

chondrules already equals Dl before compaction starts.

(B.1)The value of this limit is higher than the

limit fram, defined by Eq. (A.16), where the filling factor of the

chondrules already equals Dl before compaction starts.

If fma>fstop,

reducing of the distance between chondrules during sintering of the matrix ground mass

does not increase the packing fraction of the chondrules to the limit Dl. Sintering

has to be calculated in this case by solving the differential equation for the time

evolution of the filling factor of the matrix, Dma, with the

initial value Dcp. The pressure loading rests on the

contacts between the matrix particles. The effective porosity for the matrix-chondrule

mixture follows from the analogue of Eq. (A.10)  (B.2)In the case ftrans ≤

fma ≤ fstop

one also has to solve the differential equation for the time evolution of the

filling factor of the matrix, Dma, with the

initial value Dcp. The effective porosity for the

matrix-chondrule mixture is given by Eq. (B.2) as long as Dch calculated from Eq. (A.15) remains less than Dl. The

effective filling factor of the mixture at this point follows from Eq. (A.15) by letting Dch =

Dl; its value is

(B.2)In the case ftrans ≤

fma ≤ fstop

one also has to solve the differential equation for the time evolution of the

filling factor of the matrix, Dma, with the

initial value Dcp. The effective porosity for the

matrix-chondrule mixture is given by Eq. (B.2) as long as Dch calculated from Eq. (A.15) remains less than Dl. The

effective filling factor of the mixture at this point follows from Eq. (A.15) by letting Dch =

Dl; its value is

(B.3)If Dma exceeds

this value the pressure load is taken over by the chondrules and the calculation of the

matrix filling factor has to be continued with zero pressure load for the matrix

(B.3)If Dma exceeds

this value the pressure load is taken over by the chondrules and the calculation of the

matrix filling factor has to be continued with zero pressure load for the matrix

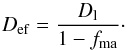

until Dma = 1. The effective filling factor of the matrix-chondrule mixture is Def and remains constant until Dma = 1. From this point on the differential equation for the time evolution of the filling factor of the chondrules has to be solved with the initial value Def.

We can thus discriminate between three different sintering modes of the binary granular mixture of chondritic material, depending on the relative abundance, fma, of matrix material:

-

1.

The chondrule-dominated case fma<ftrans where the shrinking of the material is determined by sintering of the chondrule component.

-

2.

The matrix-dominated case fstop<fma where the shrinking of the material is determined by sintering of the matrix component.

-

3.

The two-step case fma ≤ ftrans ≤ fstop where the shrinking of the material occurs in two steps, first by sintering of the matrix component and then by sintering of the chondrule component.

© ESO, 2015

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.