| Issue |

A&A

Volume 675, July 2023

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A92 | |

| Number of page(s) | 8 | |

| Section | Cosmology (including clusters of galaxies) | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202346429 | |

| Published online | 04 July 2023 | |

Maximum entropy distributions of dark matter in ΛCDM cosmology

Physical and Computational Sciences Directorate, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Richland, WA, 99354

USA

1

Received:

16

March

2023

Accepted:

4

May

2023

Context. Small-scale challenges to ΛCDM cosmology require a deeper understanding of dark matter physics.

Aims. This paper aims to develop the maximum entropy distributions for dark matter particle velocity (denoted by X), speed (denoted by Z), and energy (denoted by E) that are especially relevant on small scales where system approaches full virialization.

Methods. For systems involving long-range interactions, a spectrum of halos of different sizes is required to form to maximize system entropy. While the velocity in halos can be Gaussian, the velocity distribution throughout the entire system, involving all halos of different sizes, is non-Gaussian. With the virial theorem for mechanical equilibrium, we applied the maximum entropy principle to the statistical equilibrium of entire system, such that the maximum entropy distribution of velocity (the X distribution) could be analytically derived. The halo mass function was not required in this formulation, but it did indeed result from the maximum entropy.

Results. The predicted X distribution involves a shape parameter α and a velocity scale, v0. The shape parameter α reflects the nature of force (α → 0 for long-range force or α → ∞ for short-range force). Therefore, the distribution approaches Laplacian with α → 0 and Gaussian with α → ∞. For an intermediate value of α, the distribution naturally exhibits a Gaussian core for v ≪ v0 and exponential wings for v ≫ v0, as confirmed by N-body simulations. From this distribution, the mean particle energy of all dark matter particles with a given speed, v, follows a parabolic scaling for low speeds (∝v2 for v ≪ v0 in halo core region, i.e., “Newtonian”) and a linear scaling for high speeds (∝v for v ≫ v0 in halo outskirt, i.e., exhibiting “non-Newtonian” behavior due to long-range gravity). We compared our results against N-body simulations and found a good agreement.

Key words: methods: analytical / dark matter

© The Authors 2023

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Open Access article, published by EDP Sciences, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article is published in open access under the Subscribe to Open model. Subscribe to A&A to support open access publication.

1. Introduction

Over the last forty years, the standard ΛCDM model has significantly enhanced our understanding of large-scale structures, the state of early universe, and the content of different kinds of matter and energy (Peebles 1984, 2012; Spergel et al. 2003; Komatsu et al. 2011; Frenk et al. 2000). However, the theory has encountered a number of challenges on smaller scales (Bullock & Boylan-Kolchin 2017; Del Popolo & Le Delliou 2017; Perivolaropoulos & Skara 2022), where the model predictions are shown to be inconsistent with observations. The main challenges include: the cusp-core problem (Flores & Primack 1994; Moore 1994; de Blok 2010), missing satellite problem (Klypin et al. 1999; Moore et al. 1999a), “too-big-to-fail” problem (Boylan-Kolchin et al. 2011, 2012). In particular, the physics behind the tight baryonic Tully-Fisher relation and MOND (modified Newtonian dynamics) still remains unclear within the ΛCDM framework (McGaugh et al. 2000; Famaey & McGaugh 2013). These small-scale challenges require a better understanding of baryon and dark matter physics on small scales (< 1 Mpc), either within or beyond the ΛCDM cosmology.

One important aspect may be related to dark matter (DM) velocity distributions, which are also critical for the direct and indirect dark matter searches. For hydrodynamic turbulence, the velocity distribution is almost Gaussian and in equilibrium on a large scale or there is a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution in speed. This is a direct result of maximizing entropy for systems involving short-range interactions, as we have learned from the kinetic theory of gases. With kinetic energy cascading down to smaller scales, the distribution of velocity deviates from Gaussian and becomes more and more skewed, with the increasing skewness due to the viscous interactions on small scales.

The situation is quite different for the flow of dark matter, where the gravitational interaction is long-ranging and kinetic energy is cascading from small to large scales (Xu 2023). Mass and energy cascades provide non-equilibrium dark matter flow a mechanism that continuously releases energy and maximizes system entropy (Xu 2021b). Unlike the hydrodynamic turbulence, the collisionless dark matter flow should approach virial equilibrium on small scales, such that the DM velocity distribution on small scale should also approach some maximum entropy distribution (denoted by X). This paper aims to find this distribution for the flow of dark matter. With kinetic energy cascaded to larger scales, DM velocity distribution gradually deviates from the X distribution with increasing skewness (Xu 2022e).

The maximum entropy distributions of dark matter in ΛCDM cosmology concern the final stationary state after relaxation (a limiting state that can never reach). These distributions are especially relevant on small scales where system approaches full virialization. The original problem was motivated by the paradox between apparent universally stable self-gravitating structures and the extremely long, unphysical, two-body relaxation time required to form these structures. Ogorodnikov (1957) and Lynden-Bell (1967) were among the first to seek a fast relaxation mechanism to drive system toward the final equilibrium. The process of “violent relaxation” was thus introduced (Lynden-Bell 1967) to describe the fast energy exchange between the rapid fluctuation of gravitational potential and collisionless particles moving through the potential field. In the same paper, statistical mechanics subject to an exclusion principle was developed, where two parcels of phase space are precluded from superimposing. The theory predicts an isothermal sphere and Maxwellian velocity distribution as the final equilibrium state with maximum entropy.

However, that prediction is not entirely satisfactory. The predicted isothermal spheres have infinite mass even though prediction was made with apparent constraints of fixed finite energy and mass. The large scale N-body simulations (Navarro et al. 1995, 1997; Einasto & Haud 1989; Merritt et al. 2006) for structure formation have revealed a remarkably universal but non-isothermal halo density profile that cannot be explained by that theory. Therefore, to better understand small-scale challenges, a new theory on the limiting distributions of dark matter at small scales is desirable.

Despite significant progress made over the past several decades (Shu 1978; Tremaine et al. 1986; White & Narayan 1987; Kull et al. 1997; Hjorth & Williams 2010; Williams et al. 2010), the statistical mechanics of a self-gravitating collisionless system remains a long-standing puzzle. The difficulty can be partially attributed to the unshielded, long-range gravitational force, associated negative heat capacity, and lack of equivalence between canonical and microcanonical ensembles (Padmanabhan 1990). In contrast, the collisional molecular gases have short-range interactions and plasma systems have an effective short-range interaction due to Debye shielding. Because of these fundamental differences, conventional statistical mechanics for systems characterized by short-range interactions cannot be directly applied. Hence, it is also necessary to develop new theory that can handle long-range interactions, from which maximum entropy distributions of entire system can be obtained.

2. Limiting probability distributions

2.1. Statement of the problem

We considered a system of N particles interacting through a two-body power-law potential V(r) with an arbitrary exponent n, namely, V(r) ∝ rn. In particular, the case n = −1 represents the usual gravitational interaction. The spatial distribution of collisionless dark matter consists of distinct clusters (halos) of different sizes (Neyman & Scott 1952; Colberg et al. 1999; Moore et al. 1999b; Jenkins et al. 2001; Cooray & Sheth 2002). We will demonstrate that the spatial distribution of dark matter is dependent on the potential exponent, n. The formation of halo structures is essentially an intrinsic feature to maximize entropy for systems involving long-range interactions.

Figure 1 presents a schematic plot of the halo picture by sorting all halos in system according to their sizes from the smallest to the largest. Each column in Fig. 1 is a group of halos of the same size. The statistics can be defined on different levels: 1) individual halos; 2) group of halos of the same size (column outlined in Fig. 1); and 3) global system with all halos of different sizes. With the halo picture, we can describe the entire system on four different levels:

|

Fig. 1. Schematic plot of halo groups of different sizes. Halos are grouped and sorted according to the number of particles np in the halo, with increasing size shown from left to right. Every group of halos of the same size, np, is characterized by a halo virial dispersion |

First, on the particle level, every dark matter particle, characterized by a mass, mp, and a velocity vector, vp, should belong to one and only one particular (parent) halo. No free particles are allowed in the halo-based description of entire system.

Second, on the halo level, every halo is characterized by a halo size, namely the number of particles in it (np) or, equivalently, the halo mass (mh), a one-dimensional (1D) halo virial dispersion ( ), and halo mean velocity (vh). The particle velocity vp can be decomposed into

), and halo mean velocity (vh). The particle velocity vp can be decomposed into

namely, the halo mean velocity, vh, and velocity fluctuation,  . The halo virial dispersion is defined as

. The halo virial dispersion is defined as

that is, the variance of velocity fluctuation of all particles in the same halo. The viral dispersion can be related to the (local) temperature of a halo. The halo mean velocity vh = ⟨vp⟩h is the mean velocity of all particles in the same halo, where ⟨⟩h stands for the average over all particles in the same halo.

Third, on the group level (Fig. 1), the halo group can be characterized by the size of halos in that group (nh or mh), halo virial dispersion ( ), and halo velocity dispersion (

), and halo velocity dispersion ( ) that is defined as the dispersion (variance) of halo mean velocity, vh, for all halos in the same group,

) that is defined as the dispersion (variance) of halo mean velocity, vh, for all halos in the same group,

which represents the temperature of a halo group due to the motion of halos. The statistics defined on halo group level is the ensemble average for all halos of the same size. The virial dispersion ( ) of a halo group is the average of

) of a halo group is the average of  for all halos in the same group.

for all halos in the same group.

Lastly, on the system level, the entire system can be characterized by the total number of collisionless particles N and a 1D velocity dispersion  for all N particles, which is a measure of the total kinetic energy (or the system temperature) of entire system. The global system statistics can be different from the local statistics in individual halos or halo groups.

for all N particles, which is a measure of the total kinetic energy (or the system temperature) of entire system. The global system statistics can be different from the local statistics in individual halos or halo groups.

In addition, on the halo level, halos of the same size (np) can have different virial dispersions,  , and different mean velocity, vh. On the group level, a group of halos of the same size (np) have a virial dispersion

, and different mean velocity, vh. On the group level, a group of halos of the same size (np) have a virial dispersion  . The symbol ⟨⟩g stands for the average over all halos in the same group. Gaussian distribution (Maxwell-Boltzmann) is expected for velocity of all particles in the same halo group. Due to the independence among vh and

. The symbol ⟨⟩g stands for the average over all halos in the same group. Gaussian distribution (Maxwell-Boltzmann) is expected for velocity of all particles in the same halo group. Due to the independence among vh and  (Eq. (1)), the velocity dispersion in a group can be decomposed into

(Eq. (1)), the velocity dispersion in a group can be decomposed into

with two separate contributions, respectively. On the system level, the maximum entropy principle is still valid to describe the statistical equilibrium of the entire system.

2.2. Limiting probability distributions

For the problem described, four distributions were identified:

1) X(v): the distribution of 1D velocity v;

2) Z(v): the distribution of speed (magnitude of velocity);

3) E(ε): the distribution of particle energy ε;

4)  : the distribution of virial dispersion

: the distribution of virial dispersion  , namely, the fraction of particles with a virial dispersion between

, namely, the fraction of particles with a virial dispersion between ![$ \left[\sigma _{\mathrm{v}}^{2} ,\sigma _{\mathrm{v}}^{2} +d\sigma _{\mathrm{v}}^{2} \right] $](/articles/aa/full_html/2023/07/aa46429-23/aa46429-23-eq19.gif) . The particles’ virial dispersion is that of the halo group they belong to.

. The particles’ virial dispersion is that of the halo group they belong to.

A relationship between the distributions X and H can be established through an integral transformation,

where the velocity distribution, X, is expressed as a weighted average of Gaussian distribution of particle velocity in halo group. This average is weighted by the fraction of particles ( ) with a virial dispersion between

) with a virial dispersion between ![$ [\sigma _{\mathrm{v}}^{2} ,\sigma _{\mathrm{v}}^{2} +\mathrm{d}\sigma _{\mathrm{v}}^{2} ] $](/articles/aa/full_html/2023/07/aa46429-23/aa46429-23-eq22.gif) . The total particle velocity dispersion σ2 for all particles in the same group is given by Eq. (4). The H distribution is related to the halo mass function and can be obtained by the inverse transform of Eq. (5) (Xu 2021a).

. The total particle velocity dispersion σ2 for all particles in the same group is given by Eq. (4). The H distribution is related to the halo mass function and can be obtained by the inverse transform of Eq. (5) (Xu 2021a).

Similarly, the relation between Z and H distributions is expressed as:

where the term on the right hand comes from the Maxwellian distribution of particle speed for all particles from the same group.

2.3. Virial equilibrium and particle energy

The virial theorem for potential with an exponent of n requires

where ⟨KE⟩g and ⟨PE⟩g are particle kinetic and potential energy, respectively, with subscript ‘g’ denoting an average over all particles from the same halo group. For the halo group with a total dispersion σ2, the specific kinetic and potential energy (per unit mass) are:

to satisfy the virial theorem (Eq. (7)). Particles in groups of the smallest halos (mh = 0) have a maximum energy:

where  for the smallest halo group.

for the smallest halo group.

From the virial equilibrium (Eq. (8)), the average energy, εv, for all particles in all halos with the same given speed, v, can be related to the velocity distribution, X, as

where the factor of ‘2’ is due to the symmetry with respect to X(v) = X(−v). The energy per particle ε(v) with a given speed, v, should be the total energy, εv(v)dv, normalized by total number of particles Z(v)dv, namely, the fraction of particles with a speed in [v, v + dv],

This particle energy ε(v) is not the instantaneous energy of a particle with given speed v. Instead, it is the mean energy of all particles from all halos with a given speed v. Finally, a differential equation between X and Z distributions can be found from Eqs. (5) and (6),

A substitution of Eq. (12) into Eq. (11) gives the particle energy ε(v) that is dependent only on the X distribution:

2.4. Maximum entropy distribution X

The principle of maximum entropy requires velocity distribution with the largest entropy and the least prior information (Jaynes 1957a,b). On the system level, the principle of maximum entropy is applied to derive the X distribution with two constraints,

Here, Eq. (14) is the normalization constraint for probability distribution. Equation (15) is an energy constraint requiring the mean particle energy to be a fixed constant ⟨ε1⟩. The corresponding entropy functional can be constructed as:

where λ1 and λ2 are two Lagrangian multipliers to enforce two constraints. The entropy functional attains its maximum when the functional variation with respect to distribution X vanishes,

The particle energy can be further expressed as (from Eq. (17))

By equating Eq. (18) with Eq. (13), a differential equation for distribution X(v) can be obtained,

The general solution of X distribution is obtained as:

with parameters λ1, λ2 and n equivalently replaced by γ, α, and v0. To satisfy the first constraint (Eq. (14)), we have:

Finally, a family of distributions that maximize the system entropy can be obtained for the 1D particle velocity (the X-distribution) that depends on two free parameters α and v0,

where Ky(x) is a modified Bessel function of the second kind,

3. X distribution for velocity

3.1. Statistical properties of the X distribution

In an X distribution (Eq. (22)), the parameter v0 is introduced as a typical scale of velocity. The shape parameter α dominates the general shape of X distribution. The X distribution approaches a Laplace (or double-sided exponential) distribution with α → 0 and a Gaussian distribution with α → ∞, respectively. For any intermediate values of α, we can approximate the X distribution with a Gaussian distribution

and a Laplace distribution (double exponential)

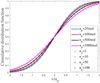

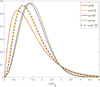

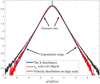

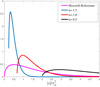

The X distribution naturally has a Gaussian core for small velocity v (with a variance of  ) and exponential wings for large velocity values (v). This is a remarkable analytical result from maximum entropy principle. Similar features are also observed from cosmological N-body simulations (Sheth & Diaferio 2001; Cooray & Sheth 2002). Figure 2 plots the X distribution for four different α = 0, 1, 10, and ∞, all with a unit variance (

) and exponential wings for large velocity values (v). This is a remarkable analytical result from maximum entropy principle. Similar features are also observed from cosmological N-body simulations (Sheth & Diaferio 2001; Cooray & Sheth 2002). Figure 2 plots the X distribution for four different α = 0, 1, 10, and ∞, all with a unit variance ( ). With decreasing α, distribution becomes sharper with a narrower peak and a broader skirt.

). With decreasing α, distribution becomes sharper with a narrower peak and a broader skirt.

|

Fig. 2. X distribution with a unit variance for four different shape parameters α. The X distribution approaches a Laplace distribution with α → 0 and a Gaussian distribution with α → ∞, respectively. For intermediate α, the X distribution has a Gaussian core for small velocity v and exponential wings for large v, in agreement with N-body simulations. |

The derivation of velocity distribution X requires the virial theorem for mechanical equilibrium (Eq. (11)), the Maxwellian velocity distribution in halo groups (Eqs. (5) and (6)), and the maximum entropy principle for statistical equilibrium of global system (Eq. (17)). We note that halo mass function is not required, which indicates that the mass function might be related to X distribution as an intrinsic result of maximum entropy. Since the X distribution does not explicitly involve parameters characterizing the system (n and  ), additional connections may be identified between α,

), additional connections may be identified between α,  , and n,

, and n,  .

.

The Gaussian core of velocity distribution X mostly comes from particles in small size halos with small viral dispersion  , where the halo velocity dispersion is much larger than the virial dispersion, namely,

, where the halo velocity dispersion is much larger than the virial dispersion, namely,  . On the other side, the exponential wing of velocity distribution is mostly due to the particles in large halos with

. On the other side, the exponential wing of velocity distribution is mostly due to the particles in large halos with  . There is a critical halo mass scale

. There is a critical halo mass scale  , where

, where  . The critical mass,

. The critical mass,  , increases with the scale factor a (or decreases with the redshift z).

, increases with the scale factor a (or decreases with the redshift z).

For small halos, the total velocity dispersion  with

with  . Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the variance of Gaussian core in Eq. (24) is comparable to the halo velocity dispersion,

. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the variance of Gaussian core in Eq. (24) is comparable to the halo velocity dispersion,  , of small halos, namely:

, of small halos, namely:

We revisit this result in Eqs. (9) and (35).

With the limiting velocity distribution explicitly derived in Eq. (22), its statistical properties can be easily obtained (listed in Table 2). More specifically, the second-order moment (variance) of X distribution should be:

which provides an additional relation between α,  and

and  .

.

3.2. Comparison with N-body simulations

The theory developed here was compared with N-body simulations carried out by the Virgo consortium. A comprehensive description of simulation data can be found in Frenk & White (2012), Jenkins et al. (1998). A friends-of-friends algorithm (FOF) was used to identify all halos from simulation data that depends only on a dimensionless parameter b, which defines the linking length b(N/V)−1/3, where V is the volume of simulation box. Halos were identified with a linking length parameter of b = 0.2. All halos were grouped into halo groups according to halo mass mh (or particle number np) (Fig. 1).

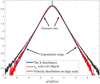

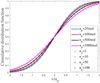

We first verified the Gaussian distribution of particle velocity in the halo groups by computing the cumulative distribution function of particle velocity for halo groups of different sizes at a redshift of z = 0. For a Gaussian distribution, the cumulative distribution is expected to be an error function. Figure 3 plots the cumulative function from N-body simulation (symbols) and the best fit of the simulation data with error functions. The cumulative distribution of particle velocity (normalized by u0 = 354.61 km s−1, i.e. 1D velocity dispersion of entire system at z = 0) was computed for halo groups of sizes np = 2, 10, 50, and 100. The simulation data confirm a Gaussian distribution of particle velocity for all particles in the same group, regardless of the halo size. However, velocity distribution for all particles (X distribution) can be non-Gaussian (Fig. 2).

|

Fig. 3. Cumulative distribution of particle velocity (normalized by u0) in halo groups of different sizes: nh = 2, 10, 50, and 100. A Gaussian distribution is expected for velocity of all particles in the same group. The cumulative distribution should be error function. Symbols plot the original data from a large-scale N-body simulation and lines plot the best fitted error function. Simulation data confirm Gaussian distribution of particle velocity in the same group, while the velocity of all the particles in all halos is non-Gaussian (i.e., the X distribution). |

Figure 4 presents a comparison of X distribution (Eq. (22)) and simulation data for the 1D velocity on a fixed small-scale value of r. We first identify pairs of particles with a given separation r = 0.1 Mpc/h at z = 0. These pairs of particles likely reside in the same halo because of the small separation r. The 1D velocity, uL, was then computed as the projection of particle velocity, u, along the direction of separation r, namely, uL = u ⋅ r. The small-scale particle velocity, uL, is finally normalized to have a unit variance and compared with the X distribution. Figure 4 demonstrates the good agreement between the simulated distribution of DM velocity on a small scale (longitudinal velocity uL) and the predicted X distribution. The noise at large velocity mostly comes from insufficient number of samples for large uL. The best fit to simulation leads to parameters α = 1.33 and  , where

, where  . The scale and redshift dependence of velocity distributions were also systematically studied in an separate paper (Xu 2022e). With kinetic energy cascaded to larger scales, the symmetric velocity distribution on a small scale (Fig. 4) gradually deviates from X distribution and becomes asymmetric with increasing skewness (Xu 2022e).

. The scale and redshift dependence of velocity distributions were also systematically studied in an separate paper (Xu 2022e). With kinetic energy cascaded to larger scales, the symmetric velocity distribution on a small scale (Fig. 4) gradually deviates from X distribution and becomes asymmetric with increasing skewness (Xu 2022e).

|

Fig. 4. X distribution with a unit variance compared against the 1D velocity uL (normalized by std(uL)) distribution on a small scale, r, from an N-body simulation. Vertical axis is plotted in the logarithmic scale (log10). The X distribution with α = 1.33 and |

In N-body simulations, small halos tend to be more virialized. The core region of large halos also tends to be more virialized than the outskirt region. Large halos are not fully virialized and the velocity distribution might not be exactly Maxwellian. Therefore, system on large scale is not fully virialized, which leads to the deviation of velocity distribution from the predicted X distribution. To illustrate this, we also present the velocity distribution of all DM particles from the same N-body simulation (black line in Fig. 4), where the deviation can be observed for velocity distribution on large scale. That deviation is mostly for large velocity in large halos and the outskirts region. The good agreement still holds for low velocity values.

4. Z and E distributions for speed and energy

With the velocity distribution (X distribution) explicitly derived in Eq. (22), the distribution of particle speed for entire system (Z distribution) can be obtained from Eq. (12),

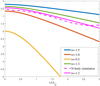

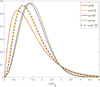

Figure 5 plots the particle speed distribution (Z distribution) for different α (α= 0, 1, 10, ∞) with  . The Z distribution approaches a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution with α → ∞. Specifically, with increasing α, Z distribution shifts towards large velocity with more particles have an intermediate speed. Statistical properties of Z distribution are also listed in Table 2.

. The Z distribution approaches a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution with α → ∞. Specifically, with increasing α, Z distribution shifts towards large velocity with more particles have an intermediate speed. Statistical properties of Z distribution are also listed in Table 2.

|

Fig. 5. Distribution of particle speed (Z distribution) for different α (α = 0.1, 1, 10, ∞). The Z distribution approaches a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution with α → ∞. With increasing α, the distribution shifts towards the large velocity with more particles exhibiting an intermediate speed and, conversely, fewer particles exhibiting a small and large speed. |

Finally, particle energy ε(v) reads (Eqs. (11), (22), and (28))

In the kinetic theory of gases, the energy of molecules is of a kinetic nature and proportional to v2, i.e. ε(v) = 3v2/2. While for collisionless dark matter particles, mean particle energy (including both kinetic and potential) for all particles with the same speed v follows a parabolic scaling when v ≪ v0 and a linear scaling when v ≫ v0,

and

This unique scaling might be critical to understand the “deep-MOND” behavior in Modified Newtonian Dynamics (MOND) theory (Xu 2022d). Particles in the outer region of halos with v ≫ v0 are more influenced by the long range gravity from other halos, which leads to the linear scaling of mean particle energy and “non-Newtonian” behavior. By contrast, particles in the inner region are less influenced and exhibit a “Newtonian” behavior.

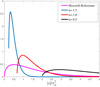

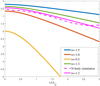

Figure 6 shows the plot of the dependence of normalized mean particle energy ε(v) on particle speed, v, for five different potential exponents n with a fixed α = 1.33. Both parabolic and linear scaling are clearly shown in Fig. 6 for small and large speeds, respectively. Dash line presents mean particle energy from the same N-body simulation. Velocity is normalized by the 1D velocity dispersion for all particles in all halos (σ0 = 395.18 km s−1). The average total energy for all particles in all halos with a given speed v is computed for each speed, v. The deviation at large velocity might be due to the insufficient sampling. Simulation matches an effective potential exponent n ≈ −1.2 ≠ −1 for virial theorem in Eq. (8).

|

Fig. 6. Dependence of normalized particle energy ε(v) (normalized by |

The mean particle energy of all particles reads

The particle energy distribution (E distribution) can be found as (with Z(v) from Eq. (28) and ε(v) from Eq. (29)):

where the dimensionless particle energy γ is defined as

With γ ≥ α, there exists a maximum particle energy (or minimum in absolute value) from Eq. (34) corresponding to particles in the smallest halo groups (Eq. (9)), where

For comparison, the energy distribution for Maxwell-Boltzmann velocity distribution is:

Figure 7 plots the energy distribution for three different potential exponents n = −1.5, −1.0, and −0.5 with a fixed α = 1.33. Compared to the Maxwell-Boltzmann, more dark matter particles have low energy and less particles have high energy.

In principle, both halo virial dispersion ( for temperature of halos) and halo velocity dispersion (

for temperature of halos) and halo velocity dispersion ( for temperature of halo groups) are functions of halo size np or mp. However, they can scale very differently with the halo size, where

for temperature of halo groups) are functions of halo size np or mp. However, they can scale very differently with the halo size, where  for massive and hot halos and

for massive and hot halos and  for small halos. The halo virial dispersion scales with the halo size as

for small halos. The halo virial dispersion scales with the halo size as  , where β = 1/(1+n/3).

, where β = 1/(1+n/3).

|

Fig. 7. Particle energy distribution, E, for three different potential exponents n = −1.5, −1.0, and −0.5 with a fixed α = 1.33. For comparison, the energy distribution of a Maxwell-Boltzmann velocity statistics is also presented in the same plot. |

The maximum entropy distributions we derived have two free parameters α and v0, while the system is fully characterized by the potential exponent, n, particle velocity dispersion,  , and the halo velocity dispersion,

, and the halo velocity dispersion,  . Equation (27) provides a connection with

. Equation (27) provides a connection with  . Another connection can be found by identifying the maximum particle energy, ε(v), at v = 0 in Eq. (35), which is the mean energy of all particles with a vanishing speed in all halos. The maximum particle energy,

. Another connection can be found by identifying the maximum particle energy, ε(v), at v = 0 in Eq. (35), which is the mean energy of all particles with a vanishing speed in all halos. The maximum particle energy,  among particles in all halos is

among particles in all halos is  with

with  for particles in the smallest halos from Eq. (9). Since most particles with small speed reside in small halos with

for particles in the smallest halos from Eq. (9). Since most particles with small speed reside in small halos with  ,

,

which is the same as we discussed in Eq. (26). With the help from Eq. (27) (the variance of X distribution), we can easily write:

from which two extremes can be confirmed, that is,  for α → 0 and

for α → 0 and  for α → ∞ (Table 1).

for α → ∞ (Table 1).

X distribution family and parameters for different potential exponents n.

Non-bonded interactions can be generally classified into two categories: short-range and long- range interactions (Cheung 2002). A force is defined to be long-range if it decreases with the distance slower than r−d, where d is the dimension of the system. Therefore, the pair interaction potential is long-range for n > −2 and short-range for n < −2 in a 3D space with d = 3. For short-range force with n < −2, we expect the system is not halo-based with α → ∞ and X distribution approaches a Gaussian for n = −2. For long-range force with n > −2, a halo-based system is expected in order to maximize system entropy. With α → 0, the X distribution approaches a Laplace distribution for n → 0. The shape parameter α reflects the nature of force (short or long range) and should be related to the potential exponent n.

5. Conclusions

The maximum entropy distributions of dark matter velocity, speed, and energy are analytically derived. They are the limiting distributions on small scales. The formation for halo structures is a direct result of entropy maximizing for systems involving long-range interactions. The virial theorem is applied for mechanical equilibrium, while the maximum entropy principle is applied for the statistical equilibrium on system level. The predicted maximum entropy distribution of velocity in entire system (X in Eq. (22)) naturally exhibits a Gaussian core at small velocity and exponential wings at large velocity. Prediction is compared with a N-body simulation with good agreement (Fig. 4). The speed (Z in Eq. (28) and Fig. 5) and energy (E in Eq. (33) and Fig. 7) distributions are also presented.

The standard kinetic energy is proportional to v2 in kinetic theory of gases with short range forces. Dark matter particles in halo-based ΛCDM cosmology with long-range interactions have a mean total energy that follows a parabolic scaling when v ≪ v0 and a linear scaling when v ≫ v0 (Eq. (29) and Fig. 6), where v0 is a typical velocity scale. The shape parameter α reflects the nature of force (long or short range) and should be related to the potential exponent n. For systems involving short-range interactions, the Gaussian is the maximum entropy distribution and no halo structures are formed. For systems with long-range interactions, we find that substructures (halos and halo groups) are required to form to maximize system entropy. Though velocity in substructure is still Gaussian, velocity in entire system can be non-Gaussian and follows a more general distribution (X distribution). Since the particle velocity must follow X distribution to maximize entropy, a broad spectrum of halos with different sizes must be formed as a direct result of entropy maximizing via mass and energy cascade. The halo mass function is given by the H distribution that is related to the X distribution via Eq. (5). In this regard, halo mass function is an intrinsic distribution to maximize the system entropy (Xu 2021a).

In Table 2, Js(x) function is defined as the integral:

Statistical properties of X and Z distributions.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Laboratory Directed Research and Development at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL). PNNL is a multiprogram national laboratory operated for the US Department of Energy (DOE) by Battelle Memorial Institute under Contract no. DE-AC05-76RL01830. Two datasets underlying this article, i.e. a halo-based and correlation-based statistics of dark matter flow, are available on Zenodo (Xu 2022b,c), along with the accompanying presentation slides “A comparative study of dark matter flow & hydrodynamic turbulence and its applications” (Xu 2022a).

References

- Boylan-Kolchin, M., Bullock, J. S., & Kaplinghat, M. 2011, MNRAS, 415, L40 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Boylan-Kolchin, M., Bullock, J. S., & Kaplinghat, M. 2012, MNRAS, 422, 1203 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock, J. S., & Boylan-Kolchin, M. 2017, ARA&A, 55, 343 [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, D. L. G. 2002, Ph.D. Thesis, Durham University, UK [Google Scholar]

- Colberg, J. M., White, S. D. M., Jenkins, A., & Pearce, F. R. 1999, MNRAS, 308, 593 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cooray, A., & Sheth, R. 2002, Phys. Rep.-Rev. Sect. Phys. Lett., 372, 1 [Google Scholar]

- de Blok, W. J. G. 2010, Adv. Astron., 2010, 789293 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Del Popolo, A., & Le Delliou, M. 2017, Galaxies, 5, 17 [Google Scholar]

- Einasto, J., & Haud, U. 1989, A&A, 223, 89 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Famaey, B., & McGaugh, S. 2013, J. Phys. Conf. Ser., 437, 012001 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Flores, R. A., & Primack, J. R. 1994, ApJ, 427, L1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Frenk, C. S., & White, S. D. M. 2012, Ann. Phys., 524, 507 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Frenk, C. S., Colberg, J. M., Couchman, H. M. P., et al. 2000, arXiv e-prints [arXiv:astro-ph/0007362v1] [Google Scholar]

- Hjorth, J., & Williams, L. L. R. 2010, ApJ, 722, 851 [Google Scholar]

- Jaynes, E. T. 1957a, Phys. Rev., 106, 620 [CrossRef] [MathSciNet] [Google Scholar]

- Jaynes, E. T. 1957b, Phys. Rev., 108, 171 [CrossRef] [MathSciNet] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, A., Frenk, C. S., Pearce, F. R., et al. 1998, ApJ, 499, 20 [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, A., Frenk, C. S., White, S. D. M., et al. 2001, MNRAS, 321, 372 [Google Scholar]

- Klypin, A., Kravtsov, A. V., Valenzuela, O., & Prada, F. 1999, ApJ, 522, 82 [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu, E., Smith, K. M., Dunkley, J., et al. 2011, ApJS, 192, 18 [Google Scholar]

- Kull, A., Treumann, R. A., & Bohringer, H. 1997, ApJ, 484, 58 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lynden-Bell, D. 1967, MNRAS, 136, 101 [Google Scholar]

- McGaugh, S. S., Schombert, J. M., Bothun, G. D., & de Blok, W. J. G. 2000, ApJ, 533, L99 [Google Scholar]

- Merritt, D., Graham, A. W., Moore, B., Diemand, J., & Terzic, B. 2006, AJ, 132, 2685 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, B. 1994, Nature, 370, 629 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, B., Ghigna, S., Governato, F., et al. 1999a, ApJ, 524, L19 [Google Scholar]

- Moore, B., Quinn, T., Governato, F., Stadel, J., & Lake, G. 1999b, MNRAS, 310, 1147 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, J. F., Frenk, C. S., & White, S. D. M. 1995, MNRAS, 275, 720 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, J. F., Frenk, C. S., & White, S. D. M. 1997, ApJ, 490, 493 [Google Scholar]

- Neyman, J., & Scott, E. L. 1952, ApJ, 116, 144 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ogorodnikov, K. F. 1957, Soviet Astron., 1, 748 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Padmanabhan, T. 1990, Phys. Rep.-Rev. Sect. Phys. Lett., 188, 285 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Peebles, P. J. E. 1984, ApJ, 284, 439 [Google Scholar]

- Peebles, P. J. E. 2012, ARA&A, 50, 1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Perivolaropoulos, L., & Skara, F. 2022, New Astron. Rev., 95, 101659 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sheth, R. K., & Diaferio, A. 2001, MNRAS, 322, 901 [Google Scholar]

- Shu, F. H. 1978, ApJ, 225, 83 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Spergel, D. N., Verde, L., Peiris, H. V., et al. 2003, ApJS, 148, 175 [Google Scholar]

- Tremaine, S., Henon, M., & Lynden-Bell, D. 1986, MNRAS, 219, 285 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- White, S. D. M., & Narayan, R. 1987, MNRAS, 229, 103 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, L. L. R., Hjorth, J., & Wojtak, R. 2010, ApJ, 725, 282 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z. 2021a, arXiv e-prints, [arXiv:2110.09676] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z. 2021b, arXiv e-prints, [arXiv:2109.09985] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z. 2022a, http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6569901 [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z. 2022b, http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6541230 [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z. 2022c, http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6569898 [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z. 2022d, arXiv e-prints, [arXiv:2203.05606] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z. 2022e, arXiv e-prints, [arXiv:2202.06515] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z. 2023, Sci. Rep., 13, 4165 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

All Tables

All Figures

|

Fig. 1. Schematic plot of halo groups of different sizes. Halos are grouped and sorted according to the number of particles np in the halo, with increasing size shown from left to right. Every group of halos of the same size, np, is characterized by a halo virial dispersion |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2. X distribution with a unit variance for four different shape parameters α. The X distribution approaches a Laplace distribution with α → 0 and a Gaussian distribution with α → ∞, respectively. For intermediate α, the X distribution has a Gaussian core for small velocity v and exponential wings for large v, in agreement with N-body simulations. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3. Cumulative distribution of particle velocity (normalized by u0) in halo groups of different sizes: nh = 2, 10, 50, and 100. A Gaussian distribution is expected for velocity of all particles in the same group. The cumulative distribution should be error function. Symbols plot the original data from a large-scale N-body simulation and lines plot the best fitted error function. Simulation data confirm Gaussian distribution of particle velocity in the same group, while the velocity of all the particles in all halos is non-Gaussian (i.e., the X distribution). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4. X distribution with a unit variance compared against the 1D velocity uL (normalized by std(uL)) distribution on a small scale, r, from an N-body simulation. Vertical axis is plotted in the logarithmic scale (log10). The X distribution with α = 1.33 and |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5. Distribution of particle speed (Z distribution) for different α (α = 0.1, 1, 10, ∞). The Z distribution approaches a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution with α → ∞. With increasing α, the distribution shifts towards the large velocity with more particles exhibiting an intermediate speed and, conversely, fewer particles exhibiting a small and large speed. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 6. Dependence of normalized particle energy ε(v) (normalized by |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 7. Particle energy distribution, E, for three different potential exponents n = −1.5, −1.0, and −0.5 with a fixed α = 1.33. For comparison, the energy distribution of a Maxwell-Boltzmann velocity statistics is also presented in the same plot. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.

![$$ \begin{aligned}&S\left[X\left(v\right)\right]=-\int _{-\infty }^{\infty }X\left(v\right)\ln X\left(v\right)\mathrm{d}v+\lambda _{1} \left(\int _{-\infty }^{\infty }X\left(v\right)\mathrm{d}v- 1\right)\nonumber \\&\qquad \qquad \ +\lambda _{2} \left(\int _{-\infty }^{\infty }X\left(v\right)\varepsilon \left(v\right)\mathrm{d}v- \left\langle \varepsilon _{1} \right\rangle \right), \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2023/07/aa46429-23/aa46429-23-eq34.gif)

![$$ \begin{aligned} J_{s} \left(x\right)&=\int _{s}^{x}e^{-t} \sqrt{t^{2} -s^{2} } \mathrm{d}t,\quad J_{s} \left(s\right)=0 \quad \mathrm{and} \quad J_{s} \left(\infty \right)=sK_{1} \left(s\right) \\ P\left(t\right)&=\int _{0}^{\infty }X\left(x\right) e^{xt} \mathrm{d}x=\frac{{v}_{0} te^{-\alpha } \left(1+\alpha \right)+J_{\alpha \sqrt{1-\left({v}_{0} t\right)^{2} } } \left(\alpha \right)}{2\alpha K_{1} \left(\alpha \right)\left[1-\left({v}_{0} t\right)^{2} \right]}\nonumber \\&\quad +\frac{K_{1} \left(\alpha \sqrt{1-\left({v}_{0} t\right)^{2} } \right)}{2K_{1} \left(\alpha \right)\sqrt{1-\left({v}_{0} t\right)^{2} } } \\ \mathrm{MGF}_{Z} \left(t\right)&=\int _{0}^{\infty }Z\left(x\right) e^{xt} \mathrm{d}x=2\left[P\left(t\right)+t\frac{\partial P}{\partial t} \right]\nonumber \end{aligned} $$](/articles/aa/full_html/2023/07/aa46429-23/aa46429-23-eq106.gif)