| Issue |

A&A

Volume 616, August 2018

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A167 | |

| Number of page(s) | 6 | |

| Section | Interstellar and circumstellar matter | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201833221 | |

| Published online | 10 September 2018 | |

Photoinduced polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon dehydrogenation

Molecular hydrogen formation in dense PDRs

1

Leiden Observatory, Leiden University,

PO Box 9513,

2300

RA Leiden,

The Netherlands

e-mail: pablo@strw.leidenuniv.nl

2

Sackler Laboratory for Astrophysics, Leiden Observatory, Leiden University, PO Box 9513,

2300

RA Leiden,

The Netherlands

3

Faculty of Aerospace Engineering, Delft University of Technology,

Kluyverweg 1,

2629

HS Delft,

The Netherlands

Received:

12

April

2018

Accepted:

3

June

2018

The physical and chemical conditions in photodissociation regions (PDRs) are largely determined by the influence of far ultraviolet radiation. Far-UV photons can efficiently dissociate molecular hydrogen, a process that must be balanced at the HI/H2 interface of the PDR. Given that reactions involving hydrogen atoms in the gas phase are highly inefficient under interstellar conditions, H2 formation models mostly rely on catalytic reactions on the surface of dust grains. Additionally, molecular hydrogen formation in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) through the Eley–Rideal mechanism has been considered as well, although it has been found to have low efficiency in PDR fronts. In a previous work, we have described the possibility of efficient H2 release from medium to large sized PAHs upon photodissociation, with the exact branching between H-/H2-loss reactions being molecule dependent. Here, we investigate the astrophysical relevance of this process, by using a model for the photofragmentation of PAHs under interstellar conditions. We focus on three PAHs cations (coronene, ovalene, and circumcoronene), which represent three possibilities in the branching of atomic and molecular hydrogen losses. We find that, for ovalene (H2-loss dominated) the rate coefficient for H2 formation reaches values of the same order as H2 formation in dust grains. This result suggests that this hitherto disregarded mechanism can account, at least partly, for the high level of molecular hydrogen formation in dense PDRs.

Key words: astrochemistry / ISM: molecules / molecular processes / photon-dominated region

© ESO 2018

1 Introduction

Photodissociation regions (PDRs) correspond to mainly neutral areas in the interstellar medium (ISM) where the physical and chemical conditions are to a large extent determined by the UV field (see Hollenbach & Tielens 1997). These include a variety of environments, from the neutral gas surrounding luminous HII regions, reflection nebulae, the galactic warm neutral medium and diffuse clouds, among others. As their name indicates, PDRs are regions where the transition from neutral, atomic gas to its molecular counterpart takes places (Sternberg et al. 2014; Bialy & Sternberg 2016). As such, the balance between formation and photodissociation of the simplest, diatomic molecules is of special interest, particularly considering that chemical reactions in the gas phase are highly unlikely. Given that H2 is the most abundant interstellar molecule, its formation mechanism is of particular importance (see Wakelam et al. 2017, for a recent review). Most works on the formation of molecular hydrogen focus on two mechanisms. On the one hand, there are Langmuir–Hinshelwood reactions, where two physisorbed H atoms migrate on a dust grain surface and, after reacting, are released as H2 (e.g., Pirronello et al. 1997; Katz et al. 1999). On the other hand, we have Eley–Rideal mechanisms, where a gas phase hydrogen atom reacts with another, chemisorbed hydrogen and both are desorbed as H2 (e.g., Duley 1996; Habart et al. 2004). The former process is known to be efficient at low dust temperatures (Td ≤ 20 K), while the latter can be effective at higher temperatures, more representative of dense PDRs.

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) emission dominates the mid-infrared spectrum of a wide variety of astronomical sources containing dust and gas, including PDRs (Tielens 2013, and reference therein). The peak emission of PAH bands is found to coincide with H2 emission lines, prompting the suggestion of a link between both species (Habart et al. 2003). This link can be due to H2 formation via H2 abstraction from superhydrogenated PAHs (Rauls & Hornekær 2008) or the H2-loss from the fragmentation of PAHs (Jochims et al. 1994). The latter mechanism is associated with the general idea of interstellar top-down chemistry with PAHs as precursors. Observations of PDRs have revealed that, as the PAH band intensity decreases, the fullerene (C60) band intensity increases (Berné & Tielens 2012; Castellanos et al. 2014). This suggests that photoprocessing of PAHs leads to their fragmentation and eventual formation of fullerenes among other intermediate species. Furthermore, several small hydrocarbons – such as C2H, C3H2, C3H+ and C4H – are known to be related to PAH mid-IR emission bands in PDRs, an association that has also been considered indicative of a top-down formation mechanism (Pety et al. 2005; Guzmán et al. 2015; Cuadrado et al. 2015). The formation of small and large hydrocarbon products through top-down photochemistry requires intense UV-fields, which is consistent with the observations of the aforementioned molecules deep within the atomic part of th PDR. However, H2 formation will be effective in slightly more shielded environments, namely, the HI/H2 transition region.

Habart et al. (2004) used the ratio of rotational to rovibrational H2 lines to determine the formation rate coefficient (R(H2)) in dense, hot PDRs. Their estimate yields values of R(H2) ~ 10−16 cm3 s−1, almost an order of magnitude higher than the standard value found in diffuse clouds, where H2 formation is expected to come exclusively from dust grains through an Eley–Rideal mechanism (3 × 10−17 cm3 s−1 Jura 1975; Gry et al. 2002). The H2 formation rate in the diffuse ISM is generally well accounted for when considering only grain surface reactions (Hollenbach & Salpeter 1971), but these reactions alone fall short at explaining the situation in dense PDRs. In order to account for this deficiency, reactions involving PAHs have been invoked as an additional mechanism leading to H2 formation. Such a connection is further supported, seeing as there is a clear spatial correlation linking H2 and PAH emission (Habart et al. 2003). The proposed routes include an Eley–Rideal mechanism analogous to that described for dust, involving the abstraction of molecular hydrogen from superhydrogenated PAHs (Rauls & Hornekær 2008; Mennella et al. 2012), and direct photodissociation of PAHs involving H2-loss (Jochims et al. 1994; Ling et al. 1995). The importance of both formation pathways has been investigated using different models for a variety of PDR conditions (e.g., Bron et al. 2014; Boschman et al. 2015; Andrews et al. 2016). These models have established that surface reactions (i.e., Eley–Rideal) on PDR fronts cannot efficiently form H2, given that under these conditions superhydrogenated PAHs make up a nearly negligible fraction of the total population. While photodissociation through H2-loss is found to be the dominant H2 formation pathway from PAHs, its rate makes a negligible contribution to the total H2 formation in PDRs. However, we note that for H2-loss from PAHs, all models rely on photodissociation parameters extrapolated from experimental and theoretical work on rather smallPAHs (up to 24 C-atoms).

On a previous work modeling the experimental dissociation pattern of PAHs, we have determined the barriers and enthalpy change required for H- and H2-loss from medium-sized PAHs (Castellanos et al. 2018). That study included an analysis on small, previously studied PAHs in order to validate our results against previous work. We found that H-hopping within PAHs is an essential part in the dehydrogenation process, creating an aliphatic-like side group (CH2), which can lead to the release of atomic or molecularhydrogen. In small PAHs, H-loss is found to be the dominant channel, in accordance with other results found in the literature (Jochims et al. 1994; Ling et al. 1995; Ling & Lifshitz 1998). Large PAHs show the predominant channel to be H2-loss, although with the caveat that solo hydrogens can only be lost in atomic form from aromatic positions.

In the present study we utilize our previously calculated rates for coronene and ovalene, and expand our calculations to circumcoronene. In Sect. 2, we discuss our model for H2 formation through photolysis of PAHs. The results are presented inSect. 3 and in Sect. 4 we discuss H2 formation in PDRs and summarize our conclusions.

2 Methods

Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations on the structures of intermediate and transition states were performed using B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) and the quantum chemistry software Gaussian 09 (Frisch et al. 2009). Transition state structures were in most cases determined with the Berny algorithm, while the Synchronous Transit-Guided Quasi-Newton (STQN) method (Peng & Schlegel 1993; Peng et al. 1996) was used in more complex cases. Reaction rates were calculated using Rice–Ramsperger–Kassel–Marcus (RRKM) theory (Baer & Hase 1996), using the sum of states for the transition state and the density of states for the parent structures. The sum and density of states were calculated using the normal vibrational modes derived from DFT, by means of the densum program from the MULTIWELL suite (Barker 2001; Barker et al. 2017).

The aforementioned methods were used to study the dehydrogenation of a series of PAHs, together with experimental and Monte Carlo techniques (Castellanos et al. 2018). The results of that work show that the fragmentation process is dominated by formation of “aliphatic” groups due to hydrogen roaming – i.e., the formation of CH2 groups on the edge of the molecule. From this point on, dehydrogenation can proceed either by atomic or molecular hydrogen loss, in a manner that is molecule dependent. In this work, we will use the results already derived for coronene and ovalene. As mentioned in Castellanos et al. (2018), in order to fit the experimental data of ovalene, the energy barriers for aliphatic H- and H2-loss had to be adjusted to match those of coronene, while keeping the values for ΔS1000 as derived from the DFT calculations. The original study did not include the circumcoronene cation and experiments on the dehydrogenation of this molecule are currently lacking. However, we have calculated the intermediate structures and transition states involved in the formation of aliphatic groups and the loss of atomic and molecular hydrogen. In order to keep consistency with the previous calculations, the energy barriers for the loss channels in circumcoronene have also been modified to match those of coronene.

We note that coronene, ovalene and circumcoronene all have duo hydrogens and, in the case of ovalene and circumcoronene, solo hydrogens with no bay-regions. Following the conclusions from Castellanos et al. (2018), we have disregarded reactions involving tertiary carbons (an edge carbon bridging two neighboring rings). Aliphatic formation is thus only possible within duos, and aromatic H-loss is the only fragmentation channel available for the solos. The isomerization rates considered in this work involve the rate of formation of an aliphatic group and its reverse. For photodissociation, both aliphatic and aromatic H- and H2-losses are calculated. All rates are based on the fully hydrogenated form of the PAH in question, with the exception of aromatic H-loss from a partially hydrogenated duo, for which the parent structure is that of the fully aromatic PAH after a single H-loss. The latter loss rate is considered separately, given that the energy barrier is ~1 eV lower than for a full duo.

In orderto assess the astronomical relevance of H2 formation, we implemented our calculated rates into the model for hydrogenation and dehydrogenation of PAHs of Andrews et al. (2016). Their model includes a variety of physical and chemical processes for PAHs in interstellar environments, including ionization, electron recombination, hydrogen attachment, photodissociation (as H- and H2-loss) and H2 formation from superhydrogenated molecules following Eley–Rideal abstraction. The focus ofthe present work is to investigate H2 formation through photodissociation on PDRs. Given that the transition from fully hydrogenated PAHs to fully dehydrogenated PAHs (the PDR front) occurs at fairly high values of UV-field intensity (G0), processes involving superhydrogenated PAHs – such as Eley–Rideal abstraction – can be disregarded. Under the same considerations, and taking into account that our DFT calculations are focused on cations, we keep electron recombination to a minimum by setting ne = 10−7 cm−3, thus ensuring that all PAHs in the model are singly ionized. While this value does not reflect the true electron density in PDRs, the efficiency of H2 formation from PAH cations is not affected by ne.

The photodissociation rates considered in the model by Andrews et al. (2016) are considered in terms of H- and H2-loss. Given that in their original formulation the formation of aliphatic groups via hydrogen hopping was not taken into account, the model receives as input a single rate for each loss. In order to work around this issue, we have calculated effective photodissociation rates. For this, the fraction of the time the PAH in question exists with an aliphatic group is calculated using

(1)

(1)

where kal(E) is the aliphatic formation rate as a function of energy, and kal,r(E) is the rate for the reverse reaction. For both rates the corresponding degeneracies are taken into account – e.g., in fully hydrogenated coronene, the twelve hydrogen atoms can hop towards the neighboring H in the same duo, while for the reverse reaction either of the two hydrogen atoms can hop back into the empty carbon. The time fraction the molecule is in a fully aromatic configuration, on the other hand, will be given by 1 − fal(E). The effective H-loss rate is calculated by multiplying the respective fractions to the corresponding photodissociation rates and adding together the contributions of aliphatic and aromatic losses. The same process is applied to H2-loss.

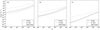

3 Results

The effective fragmentation rates, as derived from DFT calculations, are shown in Fig. 1. The three PAHs selected for this work provide examples of the three types of photofragmentation balance that can be found: H-loss dominated (coronene), H2-loss dominated (ovalene) and competitive (circumcoronene). While these rates include contributions from aromatic rates, aliphatic losses are in all cases the dominant channel for the respective loss by as much as five orders of magnitude in the relevant energy range. The only exception to this is the odd hydrogen loss, for which the aromatic H-loss dominates in all three molecules. For fragmentation to take place, the dominant loss rate must exceedthe IR photon emission rate, which is the case at 12.2, 15.5 and 25.1 eV for coronene, ovalene and circumcoronene, respectively. Considering the 13.6 eV cutoff for UV photons in the ISM, this means that, while coronene can be fragmented by single photon absorption, PAH dehydrogenation will be dominated by multiple photon absorption.

Figure 2 shows the fragmentation rates as a function of G0. These were calculated following the procedure described by Andrews et al. (2016), taking into account the temperature probability function following Bakes et al. (2001, and references therein). Such a model considers as well the possibility of multiphotonevents which, as mentioned, are needed in order to fragment larger PAHs. The effects of multiple photon absorption can be observed in Fig. 2, as deviations from a linear behavior are observed at G0 =103 in coronene, but earlier on for ovalene and circumcoronene. The three variations on the H-/H2-loss balance described before are still evident here, with odd H-losses dominating in cases where it is available. The effects of degeneracy are minor in all three PAHs, with variations due to hydrogenation level remaining below an order of magnitude in all cases.

The fragmentation of the PAHs studied here follows an established pattern under interstellar conditions. When hydrogen within duos are part of the molecule in question, these are the preferred dehydrogenation sites in all cases. Even hydrogen losses can proceed via aliphatic H- or H2-loss according to the characteristics of the PAH under consideration, as explained before. Odd hydrogen losses always occur via aromatic C–H bond cleavage with a reduced barrier. Considering that the rates involved in H-loss from the solos are exclusively aromatic and do not have the reduced barrier of partly hydrogenated duos, these are the last hydrogens to be lost in the molecule.

We have calculated the efficiency of H2 formation ( ) considering the fragmentation and hydrogen addition rates as a function of the hydrogenation state (i) using,

) considering the fragmentation and hydrogen addition rates as a function of the hydrogenation state (i) using,

(2)

(2)

where n(H) corresponds to the atomic hydrogen density, κadd is the hydrogen addition rate coefficient and f(i) corresponds to the fraction of the PAH with hydrogenation state i. For cations, we use κadd = 1.4 × 10−10, following Andrews et al. (2016). Given that in our model we only take into account a single ionization state, the following results represent the total H2 formation efficiency, based on the cations. Figure 3 presents the efficiency of coronene, ovalene and circumcoronene under different UV field intensities and atomic hydrogen densities. Coronene and circumcoronene exhibit  in the order of 1–2% under all the environmental conditions explored here. More interestingly, ovalene shows efficiencies at least one order of magnitude higher, depending on the values of G0 and n(H). However, H2 formation efficiency in ovalene does not approach one at any G0, even though one could naively expect this given that aliphatic losses are heavily dominated by H2-loss. The source of this apparent contradiction is due to the highly efficient loss from partly hydrogenated duos. Hydrogen addition cannot efficiently compete with this form of dehydrogenation, quenching the full rehydrogenation of duos which in turn prevent the formation of a new H2 unit.

in the order of 1–2% under all the environmental conditions explored here. More interestingly, ovalene shows efficiencies at least one order of magnitude higher, depending on the values of G0 and n(H). However, H2 formation efficiency in ovalene does not approach one at any G0, even though one could naively expect this given that aliphatic losses are heavily dominated by H2-loss. The source of this apparent contradiction is due to the highly efficient loss from partly hydrogenated duos. Hydrogen addition cannot efficiently compete with this form of dehydrogenation, quenching the full rehydrogenation of duos which in turn prevent the formation of a new H2 unit.

In the case of coronene, the efficiency exhibits the same behavior as a function of G0, independently of G0. This is due to fact that coronene fragmentation at these values of G0 is dominated by single photon events (Fig. 2). Ovalene and, more prominently, circumcoronene show a large spread in the peak position of  with respect to G0∕n(H) as a function of G0. This again demonstrates the degree of non-linearity of multiphoton events in PAH fragmentation. From the results presented in Fig. 1, it is evident that two-photon events will dominate the fragmentation of ovalene while, for circumcoronene, three photons are required to initiate the dehydrogenation process.

with respect to G0∕n(H) as a function of G0. This again demonstrates the degree of non-linearity of multiphoton events in PAH fragmentation. From the results presented in Fig. 1, it is evident that two-photon events will dominate the fragmentation of ovalene while, for circumcoronene, three photons are required to initiate the dehydrogenation process.

An increase in the peak value of  with G0 reflects the result of the competition between the dehydrogenation channels. Ovalene shows an evident increase in the peak value of the efficiency of molecular hydrogen formation, reflecting the increase of

with G0 reflects the result of the competition between the dehydrogenation channels. Ovalene shows an evident increase in the peak value of the efficiency of molecular hydrogen formation, reflecting the increase of  with increasing G0 and the near lack of competition with H-loss channels. In coronene, on the other hand, no such increase in

with increasing G0 and the near lack of competition with H-loss channels. In coronene, on the other hand, no such increase in  is observed, as it is to be expected considering that H-loss is the dominant channel. Unlike coronene, circumcoronene does show a slight increase in H2 formation efficiency as G0 increases, but it is nowhere near as evident as for ovalene. The fact that molecular and atomic hydrogen loss are in close competition prevents the increase of

is observed, as it is to be expected considering that H-loss is the dominant channel. Unlike coronene, circumcoronene does show a slight increase in H2 formation efficiency as G0 increases, but it is nowhere near as evident as for ovalene. The fact that molecular and atomic hydrogen loss are in close competition prevents the increase of  to the extent observed in ovalene.

to the extent observed in ovalene.

Figure 4 shows the contribution of different hydrogenation states to the total population of the molecules, at selected values of G0. The peak in the corresponding efficiency curves (Fig. 3) coincides with the value of G0 ∕n(H) that has the largest contribution from the –6H fragment in all cases. This is to be expected, given that dehydrogenation from duos is the only pathway contributing to H2 formation and coronene, ovalene and circumcoronene have the same number of duos. For PAHs with a different number of duos or other types of edge structures, this situation will vary, but in general, molecular hydrogen formation efficiency peaks at the point where half of the structures capable of producing H2 have become dehydrogenated.

The dehydrogenation pattern shows an enhancement of even hydrogen molecules with respect to odd ones, a well known experimental fact (Castellanos et al. 2018). However, the degree to which PAH fragments with an even number hydrogens dominates depends on a number of factors. Most notoriously, the dominant fragmentation channel plays a significant role. When comparing coronene and ovalene (Fig. 4a and b) it is clear that the fraction of fragments with an odd number of hydrogens in coronene has a larger contribution than that of ovalene. This is to be expected given that fragmentation from coronene is dominated by H-loss. However, there is also a dependency on how dominant the odd H-loss is over the even dehydrogenation channels. Case in point, circumcoronene has higher contributions from photoproducts with an even number of hydrogens than ovalene, although the latter is clearly dominated by H2-loss dominated, while the former shows a strong competition. Nevertheless, the odd H-loss rate in circumcoronene is faster than any of the even hydrogen loss channels, which leads to a reduced contribution of fragments with an odd hydrogenation.

The tail of  at large G0∕n(H) must be considered carefully. Once full dehydrogenation is present, the carbon skeleton can isomerize into cages and/or further fragment (Berné & Tielens 2012; Zhen et al. 2014). This will remove the carbon “flake” from the population, rendering meaningless the calculated value of

at large G0∕n(H) must be considered carefully. Once full dehydrogenation is present, the carbon skeleton can isomerize into cages and/or further fragment (Berné & Tielens 2012; Zhen et al. 2014). This will remove the carbon “flake” from the population, rendering meaningless the calculated value of  . However, the presence of solo hydrogens appears to act as a bottleneck in the fragmentation process. As seen in Fig. 4, ovalene and circumcoronene retain their last few hydrogens even at fairly large values of G0 ∕n(H). Nevertheless, one must take into account that this model does not consider isomerizations of the carbon skeleton, neither before nor after full dehydrogenation has taken place. Given that the rate of aromatic H-loss from solo hydrogens is rather slow, the internal energy of the molecule can build up further than when aliphatic losses are available. This can, in turn lead to other isomerization routes and/or fragmentation via C containing units.

. However, the presence of solo hydrogens appears to act as a bottleneck in the fragmentation process. As seen in Fig. 4, ovalene and circumcoronene retain their last few hydrogens even at fairly large values of G0 ∕n(H). Nevertheless, one must take into account that this model does not consider isomerizations of the carbon skeleton, neither before nor after full dehydrogenation has taken place. Given that the rate of aromatic H-loss from solo hydrogens is rather slow, the internal energy of the molecule can build up further than when aliphatic losses are available. This can, in turn lead to other isomerization routes and/or fragmentation via C containing units.

|

Fig. 1 Hydrogen loss rates as a function of internal energy for the coronene (panel a), ovalene (panel b) and circumcoronene (panel c) cations. H- and H2-loss are considered as from the parent molecule, while odd H-loss refers to hydrogen loss from a partly filled duo. |

|

Fig. 2 Hydrogen loss rates as a function of G0 for the coronene (panel a), ovalene (panel b) and circumcoronene (panel c) cations. H- and H2-loss are considered as from the parent molecule, while odd H-loss refers to the loss from a partly filled duo. |

|

Fig. 3 H2 formation efficiency in the photo-fragmentation of the coronene (panel a), ovalene (panel b) and circumcoronene (panel c) cations in a variety of interstellar environments. |

|

Fig. 4 Fragmentation pattern for the coronene (panel a), ovalene (panel b) and circumcoronene (panel c) cations. They are taken at 10, 100 and 1000 G0, respectively.–12H corresponds to the point in all molecules where aliphatic loss is no longer possible. Solo hydrogens are still left in the molecule at this stage in ovalene and circumcoronene (two and six, respectively). |

4 Discussion and conclusions

Using the results of the previous section, we can give a simplified expression for  . From Fig. 4 it is evident that, while the dehydrogenation process is ongoing, most of the molecules will have an even hydrogenation level. This, together with the fact that variations of

. From Fig. 4 it is evident that, while the dehydrogenation process is ongoing, most of the molecules will have an even hydrogenation level. This, together with the fact that variations of  with dehydrogenation are not very significant, leads to,

with dehydrogenation are not very significant, leads to,

(3)

(3)

This approximation is generally valid within a factor two up to the peak of the molecular hydrogen formation efficiency and will rapidly diverge from the exact value at large G0∕n(H). The values of G0 and n(H) at which  will peak are, unfortunately, more involved to calculate and a simple analytic expression valid for all PAHs cannot be derived. This is due to the effect of multiphoton absorption (a non-linear process) being an indispensable part of PAH dehydrogenation. Additionally, the dissociation parameters determined here show a wide range of variations among different PAHs, even within the same “family”, as seen for coronene and circumcoronene. The unpredictability of the peak position of H2 formation efficiency showcases how critical it is to derive accurate photodissociation parameters (in the form of energy barriers and activation enthalpies) and to have experimental confirmation of such values.

will peak are, unfortunately, more involved to calculate and a simple analytic expression valid for all PAHs cannot be derived. This is due to the effect of multiphoton absorption (a non-linear process) being an indispensable part of PAH dehydrogenation. Additionally, the dissociation parameters determined here show a wide range of variations among different PAHs, even within the same “family”, as seen for coronene and circumcoronene. The unpredictability of the peak position of H2 formation efficiency showcases how critical it is to derive accurate photodissociation parameters (in the form of energy barriers and activation enthalpies) and to have experimental confirmation of such values.

The values derived here for  at high values of G0∕n(H) have to be carefully considered. Fully dehydrogenated PAHs will rapidly undergo isomerization into fullerenes and other compounds that are not accounted for here. While the presence of solo hydrogens in PAHs appears to delay the onset of the full dehydrogenation, the high value of internal energy that the molecule can reach opens up the possibility of other unimolecular reactions not considered thus far. This caveat should not erode the fact that, in regions where partial hydrogenation makes up the larger fraction of the PAH population, the values derived here are highly accurate.

at high values of G0∕n(H) have to be carefully considered. Fully dehydrogenated PAHs will rapidly undergo isomerization into fullerenes and other compounds that are not accounted for here. While the presence of solo hydrogens in PAHs appears to delay the onset of the full dehydrogenation, the high value of internal energy that the molecule can reach opens up the possibility of other unimolecular reactions not considered thus far. This caveat should not erode the fact that, in regions where partial hydrogenation makes up the larger fraction of the PAH population, the values derived here are highly accurate.

Even though the exact extent of H2 formation through PAH fragmentation is heavily dependent on the specifics of the molecule under investigation, the current results do paint a more positive picture of the process than previous work. In a manner analogous to the formation rate in dust grains (Rd; Hollenbach & McKee 1979; Burke & Hollenbach 1983), the H2 formation rate in PAHs has been defined by Andrews et al. (2016) as,

(4)

(4)

where XPAH corresponds to the abundance of PAHs per hydrogen atom, fC is the fraction of elemental carbon locked in PAHs and NC is the number of C-atoms per PAH. Since the most favorable case within our PAH sample corresponds to ovalene, we will be basing our calculation on its results and using the physical conditions for the well studied NW PDR of NGC 7023. Following this we find RPAH(H2) ~ 10−17 cm3s−1. This is comparable to the H2 formation rate on dust grains – 1.5 × 10−17 cm3 s−1 at Tgas = 400 K and Td = 35 K – as calculated from the standard expression given by Hollenbach & McKee (1979). While the value for RPAH(H2) calculated here is about two orders of magnitude higher than the previous estimate (Andrews et al. 2016), it is nevertheless not enough to account for the disparity between the H2 formation rate in PDRs as derived from calculations and observations (Habart et al. 2004). As was recognized by Andrews et al. (2016), Eley–Rideal abstraction from superhydrogenated PAHs is not an efficient process within the photodissociation front of NGC 7023, where they note Bron et al. (2014) use a value two order of magnitude higher than the experimentally determined cross-section for coronene films (Mennella et al. 2012).

Molecular hydrogen formation from the photo-fragmentation of PAH cations can be an important process in PDRs, particularly in the region of transition between HI and H2. Although the H2 formation rate derived here is still unable to fully account for the large, observationally determined values in dense PDRs, they represent a step forward towards bridging the gap. Furthermore, these results lend further support to the case for top-down interstellar chemistry, with PAHs as a starting point, to explain the presence of molecules which are otherwise hard to account for using more traditional chemical pathways. The exact contributionto the overall H2 formation is heavily dependent on molecular properties in ways that have yet to be fully understood, and contributions from PAHs in other ionization states must be considered as well. A solution to this issue lies in close collaborations of theoretical and experimental work in order to determine the precise dissociation parameters. Nevertheless, it is evident from this work that, in molecules were the dominant dissociation channel is H2-loss,  far exceeds previous estimates. Under such conditions, molecular hydrogen formation from PAHs can be on par – and even exceed – the estimated contribution of molecular hydrogen formation from dust grains through Eley–Rideal H2 abstraction.

far exceeds previous estimates. Under such conditions, molecular hydrogen formation from PAHs can be on par – and even exceed – the estimated contribution of molecular hydrogen formation from dust grains through Eley–Rideal H2 abstraction.

Acknowledgements

Studies of interstellar chemistry at Leiden Observatory are supported through advanced-ERC grant 246976 fromthe European Research Council, through a grant by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) as part of the Dutch Astrochemistry Network, and a Spinoza premie. We acknowledge the European Union (EU) and Horizon 2020 funding awarded under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie action to the EUROPAH consortium, grant number 722346. A.C. acknowledges NWO for a VENI grant (number 639.041.543). DFT calculations were carried out on the Dutch national e-infrastructure (Cartesius) with the support of SURF Cooperative, under NWO EW projects MP-270-13 and SH-362-15.

References

- Andrews, H., Candian, A., & Tielens, A. G. G. M. 2016, A&A, 595, A23 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Baer, T., & Hase, W. L. 1996, Unimolecular Reaction Dynamics: Theory and Experiments No. 31 (Cary, NC: Oxford University Press on Demand) [Google Scholar]

- Bakes, E. L. O., Tielens, A. G. G. M., & Bauschlicher, Jr. C. W. 2001, ApJ, 556, 501 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Barker, J. R. 2001, Int. J. Chem. Kinet., 33, 232 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Barker, J. R., Nguyen, T. L., Stanton, J. F., et al. 2017, in MultiWell-2017 Software Suite, ed. j. R. Barker (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan), http://clasp-research.engin.umich.edu/multiwell/ [Google Scholar]

- Berné, O., & Tielens, A. G. G. M. 2012, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 109, 401 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bialy, S., & Sternberg, A. 2016, ApJ, 822, 83 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Boschman, L., Cazaux, S., Spaans, M., Hoekstra, R., & Schlathölter, T. 2015, A&A, 579, A72 [Google Scholar]

- Bron, E., Le Bourlot, J., & Le Petit, F. 2014, A&A, 569, A100 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Burke, J. R., & Hollenbach, D. J. 1983, ApJ, 265, 223 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos, P., Berné, O., Sheffer, Y., Wolfire, M. G., & Tielens, A. G. G. M. 2014, ApJ, 794, 83 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Castellanos, P., Candian, A., Zhen, J., Linnartz, H., & Tielens, A. G. G. M. 2018, A&A, 616, A166 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Cuadrado, S., Goicoechea, J. R., Pilleri, P., et al. 2015, A&A, 575, A82 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Duley, W. W. 1996, MNRAS, 279, 591 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch, M. J., Trucks, G. W., Schlegel, H. B., et al. 2009, Gaussian 09 Revision D.01, Gaussian Inc., Wallingford CT [Google Scholar]

- Gry, C., Boulanger, F., Nehmé, C., et al. 2002, A&A, 391, 675 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán, V. V., Pety, J., Goicoechea, J. R., et al. 2015, ApJ, 800, L33 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Habart, E., Boulanger, F., Verstraete, L., et al. 2003, A&A, 397, 623 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Habart, E., Boulanger, F., Verstraete, L., Walmsley, C. M., & Pineau des Forêts, G. 2004, A&A, 414, 531 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenbach, D., & McKee, C. F. 1979, ApJS, 41, 555 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenbach, D., & Salpeter, E. E. 1971, ApJ, 163, 155 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hollenbach, D. J., & Tielens, A. G. G. M. 1997, ARA&A, 35, 179 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Jochims, H. W., Rühl, E., Baumgärtel, H., Tobita, S., & Leach, S. 1994, ApJ, 420, 307 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Jura, M. 1975, ApJ, 197, 575 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Katz, N., Furman, I., Biham, O., Pirronello, V., & Vidali, G. 1999, ApJ, 522, 305 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ling, Y., Gotkis, Y., & Lifshitz, C. 1995, Eur. J. Mass Spectrom., 1, 41 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ling, Y., & Lifshitz, C. 1998, J. Phys. Chem. A, 102, 708 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mennella, V., Hornekær, L., Thrower, J., & Accolla, M. 2012, ApJ, 745, L2 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Peng, C., Ayala, P. Y., Schlegel, H. B., & Frisch, M. J. 1996, J. Comput. Chem., 17, 49 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Peng, C., & Schlegel, H. B. 1993, Isr. J. Chem., 33, 449 [Google Scholar]

- Pety, J., Teyssier, D., Fossé, D., et al. 2005, A&A, 435, 885 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Pirronello, V., Biham, O., Liu, C., Shen, L., & Vidali, G. 1997, ApJ, 483, L131 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Rauls, E., & Hornekær, L. 2008, ApJ, 679, 531 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, A., Le Petit, F., Roueff, E., & Le Bourlot, J. 2014, ApJ, 790, 10 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [MathSciNet] [Google Scholar]

- Tielens, A. G. G. M. 2013, Rev. Mod. Phys., 85, 1021 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Wakelam, V., Bron, E., Cazaux, S., et al. 2017, Mol. Astrophys., 9, 1 [Google Scholar]

- Zhen, J., Castellanos, P., Paardekooper, D. M., Linnartz, H., & Tielens, A. G. G. M. 2014, ApJ, 797, L30 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Hydrogen loss rates as a function of internal energy for the coronene (panel a), ovalene (panel b) and circumcoronene (panel c) cations. H- and H2-loss are considered as from the parent molecule, while odd H-loss refers to hydrogen loss from a partly filled duo. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Hydrogen loss rates as a function of G0 for the coronene (panel a), ovalene (panel b) and circumcoronene (panel c) cations. H- and H2-loss are considered as from the parent molecule, while odd H-loss refers to the loss from a partly filled duo. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 H2 formation efficiency in the photo-fragmentation of the coronene (panel a), ovalene (panel b) and circumcoronene (panel c) cations in a variety of interstellar environments. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4 Fragmentation pattern for the coronene (panel a), ovalene (panel b) and circumcoronene (panel c) cations. They are taken at 10, 100 and 1000 G0, respectively.–12H corresponds to the point in all molecules where aliphatic loss is no longer possible. Solo hydrogens are still left in the molecule at this stage in ovalene and circumcoronene (two and six, respectively). |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.