| Issue |

A&A

Volume 564, April 2014

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A103 | |

| Number of page(s) | 9 | |

| Section | Cosmology (including clusters of galaxies) | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201322106 | |

| Published online | 14 April 2014 | |

Source-position transformation: an approximate invariance in strong gravitational lensing

Argelander-Institut für Astronomie, Universität Bonn, auf dem Hügel 71, 53121 Bonn, Germany

e-mail: peter@astro.uni-bonn.de; dsluse@astro.uni-bonn.de

Received: 19 June 2013

Accepted: 7 November 2013

The main obstacle that gravitational lensing has in determining accurate masses of deflectors, or in determining precise estimates for the Hubble constant, is the degeneracy of lensing observables with respect to the mass-sheet transformation (MST). The MST is a global modification of the mass distribution which leaves all image positions, shapes, and flux ratios invariant, but which changes the time delay. Here we show that another global transformation of lensing mass distributions exists which leaves image positions and flux ratios almost invariant, and of which the MST is a special case. As is the case for the MST, this new transformation only applies if one considers only those source components that are at the same distance from us. Whereas for axi-symmetric lenses this source position transformation exactly reproduces all strong lensing observables, it does so only approximately for more general lens situations. We provide crude estimates for the accuracy with which the transformed mass distribution can reproduce the same image positions as the original lens model, and present an illustrative example of its performance. This new invariance transformation is most likely the reason why the same strong lensing information can be accounted for with rather different mass models.

Key words: gravitational lensing: strong / cosmological parameters

© ESO, 2014

1. Introduction

Multiple-image systems in strong gravitational lensing systems provide an invaluable tool for the determination of mass properties of cosmic objects, specifically of galaxies and galaxy clusters (see, e.g., Kochanek 2006; Bartelmann 2010, and references therein). The determination of the mass inside the Einstein radius of a multiple-image system is the most accurate mass measurement available for galaxies and cluster cores.

Mass estimates at larger and smaller radii are, however, less accurate because a given system of multiple images can be fitted by more than one mass model, i.e., the mass model is not unique. For example, a four-image system provide a total of six positional constraints on the lensing mass distribution, and many different density profiles can satisfy these constraints. The variety of mass distribution that can reproduce a set of lensed images can be seen by adding angular structures to the lens potential (Trotter et al. 2000; Evans & Witt 2003), or by modeling the mass distribution with a grid of variable pixels or a sum of basis functions (e.g. Saha & Williams 1997; Diego et al. 2005; Coe et al. 2008; Liesenborgs & De Rijcke 2012). Therefore, a finite set of individual lensed compact images clearly cannot uniquely determine the lensing mass distribution.

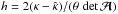

When extended source components are lensed, for example into a partial or full Einstein ring, the constraints on the lens model become considerably stronger. Here, a point-by-point modification of a mass model (like in the LensPerfect code of Coe et al. 2008) can no longer be used to fit the observed brightness profile with a lens model. However, as was pointed out first by Falco et al. (1985), even in this case the mass model is not unique; there exists a transformation of the mass distribution, called mass-sheet transformation (MST), which leaves all image positions and image flux ratios invariant. If κ(θ) denotes the dimensionless surface mass density of the lens at angular position θ, then the whole family of mass models  (1)predicts the same imaging properties as the original mass profile κ(θ). The MST keeps the mass inside the Einstein radius invariant, but changes the enclosed mass at all other radii. Furthermore, the MST changes the predicted product of time delay between images and the Hubble constant, from τ = H0 Δt to τλ = λτ, for all pairs of images. As we pointed out in Schneider & Sluse (2013; hereafter SS13), this MST may strongly affect the ability to use time-delay lens systems for accurate determinations of the Hubble constant.

(1)predicts the same imaging properties as the original mass profile κ(θ). The MST keeps the mass inside the Einstein radius invariant, but changes the enclosed mass at all other radii. Furthermore, the MST changes the predicted product of time delay between images and the Hubble constant, from τ = H0 Δt to τλ = λτ, for all pairs of images. As we pointed out in Schneider & Sluse (2013; hereafter SS13), this MST may strongly affect the ability to use time-delay lens systems for accurate determinations of the Hubble constant.

In SS13, we also considered an illustrative case where a composite lens, consisting of a Hernquist profile to resemble the distribution of stellar mass in a lens galaxy, plus a modified Navarro, Frank, and White (NFW) profile for the description of the dark matter in the inner part of the galaxy, yields almost the same imaging properties as a power-law mass profile. The relation between these two mass models is not described by a MST; in particular, we found that the time delay ratios of image pairs between these two models are not constant, as would be predicted from a MST. It thus appeared as if there were a more general transformation between lensing mass models which leaves observed image positions almost unchanged. Hints of the existence of such a transformation were pointed out earlier by several authors (Saha and Williams 2006; Read et al. 2007, their Appendix A3; Coe et al. 2008, their Sect. 3.4), but to our knowledge it has never been identified as a transformation of the source plane or derived explicitly.

In this paper, we will show the existence of a transformation of this kind, i.e., a transformation of the deflection law that leaves the strong lensing properties invariant for a finite set of source positions, and for all source positions at the same time; for reasons that will become obvious in the following, we call it the source-position transformation (SPT). The general concept of the SPT is outlined in Sect. 2. We will then show in Sect. 3 that for axi-symmetric lenses, the SPT is indeed an exact invariance transformation which leaves all relative image positions and flux ratios invariant, provided all sources, or source components, are located at the same distance, so that the transformation between physical surface mass density Σ to convergence κ is the same for all source components. Thus, there is a much larger set of mass models than described by the MST that lead to the same strong lensing predictions as the original mass distribution. We then turn to the more general case in Sect. 4 and show that the lens models obtained through an SPT in general lead to different imaging properties, but that these differences can be quite small in realistic cases. We consider the same example as that in SS13 to show how the SPT works in practice; a more detailed investigation of the SPT will be deferred to a later publication. We briefly discuss our findings and conclude in Sect. 5; in particular, we will discuss the point that the SPT only yields an approximate invariance transformation, and its relevance to applications in strong lensing systems.

2. The principle of the source position transformation

A given mass distribution κ(θ) defines a mapping from the lens plane θ to the source plane, β = θ − α(θ); throughout this paper, we use standard gravitational lensing notation (see, e.g., Schneider 2006). Provided the mass is sufficiently concentrated, there will be regions in the source plane such that if a source is located there, it has multiple images, that is, several points θi correspond to the same source position. The source position corresponding to these images is not observable; hence, the constraint imposed on the lens from observing n such multiple images is  (2)for all 1 ≤ i<j ≤ n. Hence, the constraints we obtain from observing a strong lensing system is at best a relation between points corresponding to the same source position, i.e., a mapping θi(θ1), i ≥ 2, for all images i corresponding to the same source position as θ1. Images corresponding to singly-imaged source locations carry no strong lensing information about the lens mapping.

(2)for all 1 ≤ i<j ≤ n. Hence, the constraints we obtain from observing a strong lensing system is at best a relation between points corresponding to the same source position, i.e., a mapping θi(θ1), i ≥ 2, for all images i corresponding to the same source position as θ1. Images corresponding to singly-imaged source locations carry no strong lensing information about the lens mapping.

We now ask whether there exists another deflection law  which yields exactly the same mapping θi(θ1) as the original one. If such a mass distribution exists, then the condition

which yields exactly the same mapping θi(θ1) as the original one. If such a mass distribution exists, then the condition  (3)must be satisfied, for all images i (≥2) corresponding to the same source position β as θ1.

(3)must be satisfied, for all images i (≥2) corresponding to the same source position β as θ1.

The above consideration shows that the new deflection law  provides the same mapping θi(θ1) as the original one if (1) all image pairs θ1, θ2 that belong to the same source position in the original mapping are also multiple images under the new deflection law; and (2) any two points θ1, θ2 which do not correspond to the same source position in the original mapping are also not matched by the new one. Two deflection laws which satisfy this condition are called equivalent.

provides the same mapping θi(θ1) as the original one if (1) all image pairs θ1, θ2 that belong to the same source position in the original mapping are also multiple images under the new deflection law; and (2) any two points θ1, θ2 which do not correspond to the same source position in the original mapping are also not matched by the new one. Two deflection laws which satisfy this condition are called equivalent.

If an equivalent deflection law to α indeed exists, then the new deflection  defines a new lens mapping

defines a new lens mapping  (4)from the lens plane to the source plane. The different images θi corresponding to the same source position β must also have the same source position

(4)from the lens plane to the source plane. The different images θi corresponding to the same source position β must also have the same source position  in the new mapping, according to (3). Therefore, the new deflection law

in the new mapping, according to (3). Therefore, the new deflection law  defines a mapping

defines a mapping  , implicitly given by

, implicitly given by  (5)where θ is any of the possible multiple images corresponding to the source position1β.

(5)where θ is any of the possible multiple images corresponding to the source position1β.

We can reverse the argument and consider a mapping  from the original source coordinates to the new ones; this mapping in the source plane gives rise to a modified deflection law, as seen by (5),

from the original source coordinates to the new ones; this mapping in the source plane gives rise to a modified deflection law, as seen by (5),  (6)where in the last step we inserted the original lens equation β = θ − α(θ). Therefore, any source-position transformation (SPT)

(6)where in the last step we inserted the original lens equation β = θ − α(θ). Therefore, any source-position transformation (SPT)  defines a deflection law

defines a deflection law  such that all images of the same source under the original lens mapping are also multiple images with the new lens Eq. (4). Thus, the two lens mappings caused by α and

such that all images of the same source under the original lens mapping are also multiple images with the new lens Eq. (4). Thus, the two lens mappings caused by α and  predict the same multiple images, for all source positions β (or

predict the same multiple images, for all source positions β (or  ).

).

The mass-sheet transformation (MST) is a special case of this more general SPT, obtained by setting  , which gives rise to the transformed deflection law

, which gives rise to the transformed deflection law ![\begin{equation} \hat{\vc\alpha}(\vc\theta) =\vc\theta-\lambda[\vc\theta-\vc\alpha(\vc\theta)] =\lambda\vc\alpha(\vc\theta)+(1-\lambda)\vc\theta, \label{eq:hatalphaMST} \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2014/04/aa22106-13/aa22106-13-eq32.png) (7)that we recognize to be the deflection of the mass-sheet transformed deflection α, corresponding to the transformed covergence κλ in (1).

(7)that we recognize to be the deflection of the mass-sheet transformed deflection α, corresponding to the transformed covergence κλ in (1).

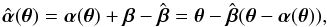

The Jacobi matrix of the new lens Eq. (4) reads  (8)where ℬ is the Jacobi matrix of the SPT and

(8)where ℬ is the Jacobi matrix of the SPT and  the Jacobi matrix of the original lens equation. This implies that

the Jacobi matrix of the original lens equation. This implies that  (9)Hence, if the SPT

(9)Hence, if the SPT  is a one-to-one mapping (with no loss of generality, we will require detℬ> 0 for all β), the critical curves of the modified lens mapping are exactly the same as those of the original lens mapping2.

is a one-to-one mapping (with no loss of generality, we will require detℬ> 0 for all β), the critical curves of the modified lens mapping are exactly the same as those of the original lens mapping2.

From (8), we infer that the relative magnification matrices between image pairs from the same source  remain unchanged,

remain unchanged,  (10)which implies that magnification ratios of image pairs are preserved, as well as their relative image shapes.

(10)which implies that magnification ratios of image pairs are preserved, as well as their relative image shapes.

To summarize this section: Any bijective SPT  (with detℬ> 0) defines an equivalent deflection law

(with detℬ> 0) defines an equivalent deflection law  given by (6), i.e., which yields the same strong lensing properties as the original lens mapping. However, this does not necessarily imply that there is a corresponding mass distribution

given by (6), i.e., which yields the same strong lensing properties as the original lens mapping. However, this does not necessarily imply that there is a corresponding mass distribution  which yields the deflection law

which yields the deflection law  , owing to the fact that in general, the Jacobian matrix

, owing to the fact that in general, the Jacobian matrix  will be non-symmetric (and thus the deflection

will be non-symmetric (and thus the deflection  cannot be derived as a gradient of a deflection potential); we will discuss this topic in more detail in Sect. 4. However, for the special case of axi-symmetric lenses, such modified mass distributions do exist, as discussed next.

cannot be derived as a gradient of a deflection potential); we will discuss this topic in more detail in Sect. 4. However, for the special case of axi-symmetric lenses, such modified mass distributions do exist, as discussed next.

3. The axi-symmetric case

We first consider the case of an axi-symmetric lens, for which the SPT yields an exact invariance transformation between different mass profiles κ(θ), which will be explicitly derived in Sect. 3.1. In Sect. 3.2, we provide a few examples of these modified density profiles.

3.1. The SPT-transformed mass profile

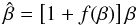

We denote by κ(θ) the radial mass profile of a lens, corresponding to the lens mapping β = θ − α(θ), and consider  (11)to describe the SPT. To preserve axi-symmetry, the deformation function f(β) must be even, f( − β) = f(β). Furthermore, we require the SPT (11) to be one-to-one, i.e.,

(11)to describe the SPT. To preserve axi-symmetry, the deformation function f(β) must be even, f( − β) = f(β). Furthermore, we require the SPT (11) to be one-to-one, i.e.,  . The modified deflection law is, according to (6),

. The modified deflection law is, according to (6), ![\begin{eqnarray} \hat\alpha(\theta)&=&\theta-\eck{1+f(\theta-\alpha(\theta))} [\theta-\alpha(\theta)]\nonumber \\ &=&\alpha(\theta)-f(\theta-\alpha(\theta))[\theta-\alpha(\theta)]. \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2014/04/aa22106-13/aa22106-13-eq48.png) (12)We will show next that this deflection can be derived from a mass profile

(12)We will show next that this deflection can be derived from a mass profile  . For this, we first write the deflection as

. For this, we first write the deflection as  , where

, where  (13)is the enclosed dimensionless mass within θ. This yields

(13)is the enclosed dimensionless mass within θ. This yields  (14)The mass profile

(14)The mass profile  is obtained from

is obtained from  through

through  ; calculating the derivative, we find

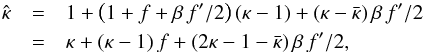

; calculating the derivative, we find  (15)where we have dropped the arguments of the functions, keeping in mind that α depends on θ and f on β = θ − α; furthermore, we used that dβ/ dθ = 1 − α′, and in the last step, we employed the relations α′ + α/θ = 2κ and

(15)where we have dropped the arguments of the functions, keeping in mind that α depends on θ and f on β = θ − α; furthermore, we used that dβ/ dθ = 1 − α′, and in the last step, we employed the relations α′ + α/θ = 2κ and  which apply for the axi-symmetric case3. Hence,

which apply for the axi-symmetric case3. Hence, ![\begin{eqnarray} \hat \kappa(\theta)={\hat m'(\theta)\over 2\theta} &=&\kappa(\theta)-[1-\kappa(\theta)]\,f(\theta-\alpha(\theta)) \nonumber \\ &&- {\theta\over 2} \det\A(\theta)\,f'(\theta-\alpha(\theta)). \label{eq:kh-axi} \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2014/04/aa22106-13/aa22106-13-eq64.png) (16)This equation now yields an explicit expression for the mass profile

(16)This equation now yields an explicit expression for the mass profile  of the transformed lens mapping, in terms of the original mass distribution κ(θ) and the source-plane deformation f(θ). The mass profiles κ(θ) and

of the transformed lens mapping, in terms of the original mass distribution κ(θ) and the source-plane deformation f(θ). The mass profiles κ(θ) and  thus predict exactly the same lensing properties concerning multiple images and flux ratios of compact images, as well as the multiple images of extended source components. Whereas the magnifications and the corresponding shapes of the sources are affected, these properties are unobservable in general in strong lensing systems.

thus predict exactly the same lensing properties concerning multiple images and flux ratios of compact images, as well as the multiple images of extended source components. Whereas the magnifications and the corresponding shapes of the sources are affected, these properties are unobservable in general in strong lensing systems.

Of course, not every combination of κ and f yields a mass distribution  that is physically meaningful. For example,

that is physically meaningful. For example,  may not be monotonically decreasing outwards, as one would expect from projecting a physically reasonable three-dimensional mass distribution, or it may even become negative for some ranges in θ. Therefore, to obtain reasonable mass models, the choice of f for a given κ is restricted. We will encounter this restriction in later examples.

may not be monotonically decreasing outwards, as one would expect from projecting a physically reasonable three-dimensional mass distribution, or it may even become negative for some ranges in θ. Therefore, to obtain reasonable mass models, the choice of f for a given κ is restricted. We will encounter this restriction in later examples.

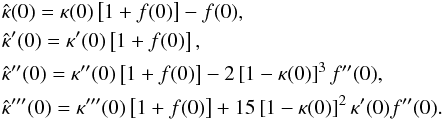

3.2. Behavior at special points

To gain more insight into this transformation, we first consider some special locations in the lens plane, starting with the tangential critical curve at θ = θE, where α(θE) = θE and thus β = 0. Writing  and using α′ = 2κ − α/θ, we find from differentiating (16) that at the Einstein radius

and using α′ = 2κ − α/θ, we find from differentiating (16) that at the Einstein radius  (17)where we also used the fact that f is an even function, i.e., its odd derivatives vanish at the origin. These relations show how the mass profile can be modified near the Einstein radius. We can choose

(17)where we also used the fact that f is an even function, i.e., its odd derivatives vanish at the origin. These relations show how the mass profile can be modified near the Einstein radius. We can choose  freely with an appropriate choice of f(0), but that fixes the slope of

freely with an appropriate choice of f(0), but that fixes the slope of  at θE, which is also determined by f(0). This connection between

at θE, which is also determined by f(0). This connection between  and

and  is the same as for the MST. The new feature of the SPT shows up for the curvature of the mass profile at θE for which we can again make a choice, but then the third derivative is fixed, and so on. The fact that f is an even function implies that we can make a choice for all even derivatives, but the odd derivatives are then tied to the former.

is the same as for the MST. The new feature of the SPT shows up for the curvature of the mass profile at θE for which we can again make a choice, but then the third derivative is fixed, and so on. The fact that f is an even function implies that we can make a choice for all even derivatives, but the odd derivatives are then tied to the former.

Choosing the derivatives of the mass profile at the Einstein radius by selecting f(0) and its even derivatives then fixes the expansion of the central surface mass density through  (18)In particular, if the mass profile is smooth at the origin, so that all odd derivatives of κ vanish there, the same property will be shared by the transformed mass distribution.

(18)In particular, if the mass profile is smooth at the origin, so that all odd derivatives of κ vanish there, the same property will be shared by the transformed mass distribution.

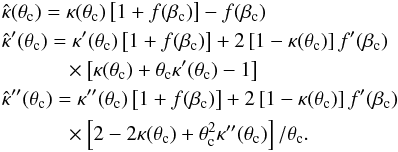

If there is a radial critical curve, which is the case if κ(θ) is a regular function, then at θc, 1 − α′(θc) = 0. The corresponding caustic in the source plane has radius βc = α(θc) − θc, with α(θc) = θc[2κ(θc) − 1]. At this location, we then obtain  (19)

(19)

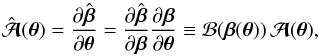

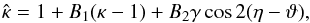

3.3. Some examples of transformed density profiles

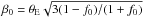

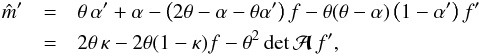

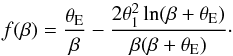

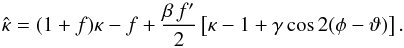

Our first set of examples of the action of the SPT is constructed such that near the tangential critical curve, the transformed mass distribution is approximately a power law,  , for θ close to θE. For this power-law distribution, one finds that

, for θ close to θE. For this power-law distribution, one finds that  (20)If we choose a singular isothermal sphere (SIS) as the original mass model, with κ = θE/ (2θ), α = θE, and use the first three relations of (17), the second equation of (20) then yields a condition for the second derivative of f at the origin,

(20)If we choose a singular isothermal sphere (SIS) as the original mass model, with κ = θE/ (2θ), α = θE, and use the first three relations of (17), the second equation of (20) then yields a condition for the second derivative of f at the origin,  (21)where f0 ≡ f(0), f2 ≡ f′′(0), and the local slope is ν = (1 + f0) / (1 − f0).

(21)where f0 ≡ f(0), f2 ≡ f′′(0), and the local slope is ν = (1 + f0) / (1 − f0).

|

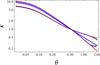

Fig. 1 Axi-symmetric example of an SPT between a non-singular isothermal sphere (solid blue curve), with core θc = 0.1θE, and other mass profiles. The other curves are transformed mass profiles, using the SPT, with different deformation functions f(β), all satisfying the power-law condition (20), and with slope ν = 0.5 (flatter curves) and ν = 1.4 (steeper curves). The dashed black curves correspond to the polynomial f(β) = f0 + f2β2/ 2, the red curves to |

In Fig. 1 we have plotted the original mass profile, where we have taken a non-singular isothermal sphere with core radius θc = 0.1θE; the introduction of a small core only affects the foregoing relations slightly, as these are obtained by considering κ(θ) at the Einstein radius. For two values of the slope ν near the Einstein radius, ν = 0.5 and ν = 1.4, we have plotted three different transformed mass profiles, where the corresponding functions f(β) are described in the figure caption. For all these cases, the local behavior near the Einstein radius is indeed well approximated by a power law. Some of the profiles become unphysical near θ ~ 2, i.e., β ~ 1, because the first derivative of f that enters (16) becomes too large there for the corresponding deformation function. As mentioned before, the transformation in the source plane is restricted by the requirement that the resulting  corresponds to the physically meaningful mass distribution. Nevertheless, these simple examples already show the range of freedom the SPT offers in the generation of axi-symmetric mass profiles with identical strong lensing behavior. We also point out that we plotted the mass profiles only up to θ = 2θE, i.e., in the angular range where multiple images occur. For larger θ, the mass profile can be chosen arbitrarily, without constraints.

corresponds to the physically meaningful mass distribution. Nevertheless, these simple examples already show the range of freedom the SPT offers in the generation of axi-symmetric mass profiles with identical strong lensing behavior. We also point out that we plotted the mass profiles only up to θ = 2θE, i.e., in the angular range where multiple images occur. For larger θ, the mass profile can be chosen arbitrarily, without constraints.

We next consider the case of large β>βc, for which no multiple images occur, so that the lens mapping becomes one-to-one there. Hence, for sufficiently large θ, the lens equation defines a mapping θ(β). We then can rewrite (16) in the form ![\begin{equation} f'(\beta)+{2[1-\kappa(\theta)]\over \theta\,\det\A(\theta)}f(\beta) ={2\eck{\kappa(\theta)-\hat\kappa(\theta)}\over \theta\,\det\A(\theta)}, \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2014/04/aa22106-13/aa22106-13-eq104.png) (22)or by using the mapping θ(β),

(22)or by using the mapping θ(β),  (23)where

(23)where  and

and  are functions of β. For a given κ and a target

are functions of β. For a given κ and a target  , the function f can be determined by solving this differential equation.

, the function f can be determined by solving this differential equation.

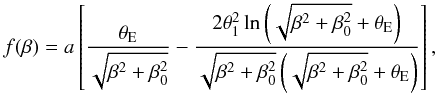

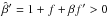

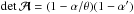

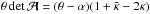

We will give a simple example of this procedure. We assume κ to describe an SIS, and choose our target density profile to be  . This yields

. This yields  for which the deformation function becomes

for which the deformation function becomes  (26)This functional form of f is, however, only a valid desciption for large arguments; in particular, f is not an even function of β. We can now modify f such that it retains the form (26) for large β, but becomes a function of β2 only. A simple way to achieve this is to replace β in (26) by

(26)This functional form of f is, however, only a valid desciption for large arguments; in particular, f is not an even function of β. We can now modify f such that it retains the form (26) for large β, but becomes a function of β2 only. A simple way to achieve this is to replace β in (26) by  , for a suitably chosen β0.

, for a suitably chosen β0.

|

Fig. 2 Second example of an SPT, in the axi-symmetric case, between an SIS with mass distribution κ(θ) and other mass distributions |

In Fig. 2, we illustrate this example, showing that by this choice of f one finds a mass distribution  which has a significantly different form from κ, nevertheless giving rise to exactly the same strong lensing properties for all source positions.

which has a significantly different form from κ, nevertheless giving rise to exactly the same strong lensing properties for all source positions.

We note that the slopes near the Einstein radius of the profiles shown in Figs. 1 and 2 are quite different, hence these mass models will give rise to very different predictions for the product of time delay and Hubble constant, τ = H0 Δt, which reinforces the point made in SS13.

4. The general case

We now drop the assumption of axi-symmetry; in this case, the matrix  in (8) will not be symmetric in general, because

in (8) will not be symmetric in general, because  is symmetric only if the directions of the eigenvectors of

is symmetric only if the directions of the eigenvectors of  and ℬ are the same. For source points that correspond to multiple images, even if we could arrange ℬ to have the same eigendirections as

and ℬ are the same. For source points that correspond to multiple images, even if we could arrange ℬ to have the same eigendirections as  , it will not have the same eigendirections as

, it will not have the same eigendirections as  for the other images θi. The only possibility to keep

for the other images θi. The only possibility to keep  symmetric for a general lens is to have ℬ proportional to the unit matrix, which is the case for

symmetric for a general lens is to have ℬ proportional to the unit matrix, which is the case for  , which recovers the MST mentioned before.

, which recovers the MST mentioned before.

The asymmetric nature of  , discussed in more detail in Sect. 4.1, implies that the deflection law

, discussed in more detail in Sect. 4.1, implies that the deflection law  , which yields exactly the same strong lensing properties as α (for all source components at the same distance) cannot be derived as the gradient of a deflection potential. Thus, in general there is no surface mass density

, which yields exactly the same strong lensing properties as α (for all source components at the same distance) cannot be derived as the gradient of a deflection potential. Thus, in general there is no surface mass density  that generates the same strong lensing properties for all source positions as κ. However, it may be possible to find a surface mass density that generates almost the same mapping for all source positions. In Sect. 4.2 we obtain a crude estimate for the amplitude of the asymmetry of

that generates the same strong lensing properties for all source positions as κ. However, it may be possible to find a surface mass density that generates almost the same mapping for all source positions. In Sect. 4.2 we obtain a crude estimate for the amplitude of the asymmetry of  , for the special case of a quadrupole lens. An illustrative example is discussed in more detail in Sect. 4.3, where we show explicitly that the impact of the asymmetry of

, for the special case of a quadrupole lens. An illustrative example is discussed in more detail in Sect. 4.3, where we show explicitly that the impact of the asymmetry of  can be very small in realistic cases.

can be very small in realistic cases.

4.1. The transformed mass profile

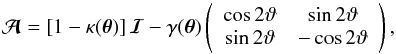

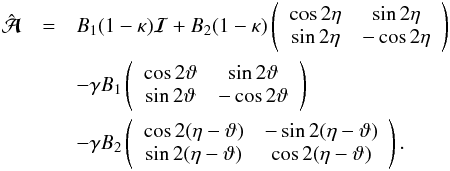

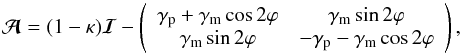

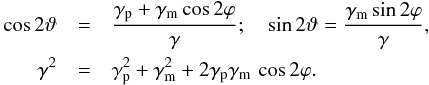

The Jacobi matrix of the original lens mapping has the form  (27)where ℐ is the unit matrix. We will write the matrix ℬ in a similar form,

(27)where ℐ is the unit matrix. We will write the matrix ℬ in a similar form,  (28)The angle ϑ is the phase of the shear of the original lens mapping; similarly, η is the phase of the shear of the mapping

(28)The angle ϑ is the phase of the shear of the original lens mapping; similarly, η is the phase of the shear of the mapping  at the position β(θ). We then obtain

at the position β(θ). We then obtain  (29)Since these two phases are different in general,

(29)Since these two phases are different in general,  is asymmetric, according to the final term in (29). As we will show below, in the axi-symmetric case, these two phases are the respective polar angles of θ and β; the fact that β and θ are collinear in the axi-symmetric case guarantees that these two angles are the same (or differ by π). This then implies the symmetry of

is asymmetric, according to the final term in (29). As we will show below, in the axi-symmetric case, these two phases are the respective polar angles of θ and β; the fact that β and θ are collinear in the axi-symmetric case guarantees that these two angles are the same (or differ by π). This then implies the symmetry of  .

.

We now define the modified surface mass density  through the trace of

through the trace of  ,

,  , i.e., in the same way as if the Jacobian

, i.e., in the same way as if the Jacobian  were derived from a deflection potential; this yields

were derived from a deflection potential; this yields  (30)where it should be kept in mind that κ, γ, and ϑ depend on θ, and that the Bi and η depend on β(θ). In addition, we characterize the asymmetry of

(30)where it should be kept in mind that κ, γ, and ϑ depend on θ, and that the Bi and η depend on β(θ). In addition, we characterize the asymmetry of  by

by  (31)We can easily show that Eq. (30) for

(31)We can easily show that Eq. (30) for  reduces to our earlier result for an axi-symmetric mass profile. From (11) in the form

reduces to our earlier result for an axi-symmetric mass profile. From (11) in the form  , we obtain

, we obtain  (32)and the phase is η = φ, where φ is the polar angle of β. The shear of the lens is

(32)and the phase is η = φ, where φ is the polar angle of β. The shear of the lens is  , and its phase agrees with the polar angle of θ, ϑ = ϕ. Here,

, and its phase agrees with the polar angle of θ, ϑ = ϕ. Here,  is the mean convergence within radius θ. Since either φ = ϕ or φ = ϕ + π, the asymmetric term in (29) vanishes, and the modified convergence becomes

is the mean convergence within radius θ. Since either φ = ϕ or φ = ϕ + π, the asymmetric term in (29) vanishes, and the modified convergence becomes  (33)which is seen to agree with (16), since

(33)which is seen to agree with (16), since  .

.

One can expect that the convergence  defined in (30) yields a deflection law which very closely resembles that of

defined in (30) yields a deflection law which very closely resembles that of  if the asymmetry of

if the asymmetry of  , as characterized by

, as characterized by  , is small compared to

, is small compared to  . This will be the case if the source plane deformation, which determines the amplitude of B2, is sufficiently small and/or if the misalignment between the shear γ of the lens mapping and that of the mapping

. This will be the case if the source plane deformation, which determines the amplitude of B2, is sufficiently small and/or if the misalignment between the shear γ of the lens mapping and that of the mapping  is small. This misalignment depends on the kind of lens mapping one is dealing with.

is small. This misalignment depends on the kind of lens mapping one is dealing with.

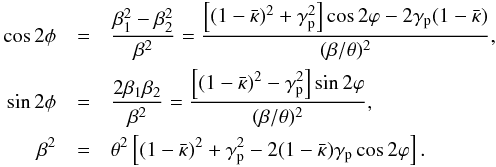

4.2. Example: the quadrupole lens

As an illustrative case, we consider a quadrupole lens, i.e., an axi-symmetric matter distribution characterized by the convergence κ( | θ |) plus some external shear, so that the lens equation becomes  (34)where γp is a constant shear caused by some external “perturbing” large-scale mass distribution4. Denoting the shear of the main lens by

(34)where γp is a constant shear caused by some external “perturbing” large-scale mass distribution4. Denoting the shear of the main lens by  , the Jacobian reads

, the Jacobian reads  (35)which can be compared with the form (27) of

(35)which can be compared with the form (27) of  ; this yields for the shear components of

; this yields for the shear components of

(36)For the SPT, we again consider a radial stretching,

(36)For the SPT, we again consider a radial stretching,  , for which the coefficients of ℬ are given in (32), and for which the phase η equals the polar angle φ. We calculate β from the lens Eq. (34), to find

, for which the coefficients of ℬ are given in (32), and for which the phase η equals the polar angle φ. We calculate β from the lens Eq. (34), to find  (37)From these relations, we can calculate the products γ cos2(η − ϑ) = γ cos2(φ − ϑ) and γ sin2(φ − ϑ), which enter the quantities (30) and (31),

(37)From these relations, we can calculate the products γ cos2(η − ϑ) = γ cos2(φ − ϑ) and γ sin2(φ − ϑ), which enter the quantities (30) and (31),  Combining (30), (32), and (38), we then obtain for the transformed surface mass density

Combining (30), (32), and (38), we then obtain for the transformed surface mass density  (40)If we now approximate the function f(β) near the origin by f(β) = f0 + f2β2/ 2, where we accounted for the fact that f is an even function, we see that βf′/ 2 = f2β2/ 2, so that

(40)If we now approximate the function f(β) near the origin by f(β) = f0 + f2β2/ 2, where we accounted for the fact that f is an even function, we see that βf′/ 2 = f2β2/ 2, so that  (41)The terms independent of f2 present just the MST (1), with λ = 1 + f0. The non-linear part of the SPT, here parametrized by f2, adds a monopole contribution to

(41)The terms independent of f2 present just the MST (1), with λ = 1 + f0. The non-linear part of the SPT, here parametrized by f2, adds a monopole contribution to  and contributions that depend on ϕ. The monopole contribution itself has two parts, the first independent of γp – which can be shown to agree with (16) – and the second ∝

and contributions that depend on ϕ. The monopole contribution itself has two parts, the first independent of γp – which can be shown to agree with (16) – and the second ∝ . This second contribution is expected to be small, for reasonably small values of the external shear. The angle-dependent contributions to

. This second contribution is expected to be small, for reasonably small values of the external shear. The angle-dependent contributions to  vanish for γp = 0. At the tangential critical curve of the axi-symmetric lens, where

vanish for γp = 0. At the tangential critical curve of the axi-symmetric lens, where  , these angle-dependent terms are at least of order

, these angle-dependent terms are at least of order  , and are again expected to be small. For locations away from the Einstein circle, the leading-order terms are ∝ γp and thus typically a factor of γp smaller than the f2-induced contributions to the monopole term.

, and are again expected to be small. For locations away from the Einstein circle, the leading-order terms are ∝ γp and thus typically a factor of γp smaller than the f2-induced contributions to the monopole term.

With the same form of f(β), the quantity (31) describing the asymmetry of  becomes

becomes  (42)From this result we see that the asymmetry vanishes if γp = 0. Furthermore, it vanishes on the axes, ϕ = nπ/ 2, n = 0,1,2,3, since points θ on the symmetry axes are mapped onto the corresponding axis in the source plane, so that the shear matrices are aligned in this case.

(42)From this result we see that the asymmetry vanishes if γp = 0. Furthermore, it vanishes on the axes, ϕ = nπ/ 2, n = 0,1,2,3, since points θ on the symmetry axes are mapped onto the corresponding axis in the source plane, so that the shear matrices are aligned in this case.

|

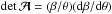

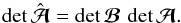

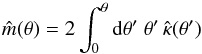

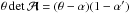

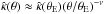

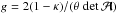

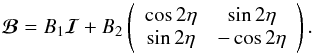

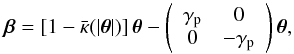

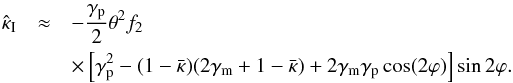

Fig. 3 Right: set of mock lensed images produced by our fiducial lens model (using a grid of source positions shown in the first quadrant of the left panel). The color-coding shows the offset in arcseconds, between the original image positions and those found with the power-law model. Left: first quadrant (upper right): grid of source positions lensed with our fiducial model to produce the images shown in the right panel. The color-coding indicates the χ2 associated with each source, assuming an astrometric uncertainty on the image position of σθx,y = 0.004′′. In the third quadrant (lower left), the sources do not have corresponding lensed images on the right panel, and are colored as a function of the ratio of their total magnification as derived with the power-law and the fiducial models (i.e., |

As expected,  is proportional to the curvature f2 of the distortion function at the origin, and in addition has as prefactor the external shear γp. Both of these are typically small; characteristic values for the external shear in strong lens systems are γp ≲ 0.1. We have seen in Sect. 2 that distortion functions with excessive curvature lead to unphysical mass distributions, so that f2θ2 will be considerably smaller than unity in the multiple-image region. Hence, the prefactor will be smaller than about 10-2. In fact, in the example considered in the following subsection, this prefactor is of order 2 × 10-4. Furthermore, we also point out that the dominant term in the bracket (the middle one) will be small near the critical curve, since this curve will be close to the radius θE of the Einstein circle of the original axi-symmetric lens model, where

is proportional to the curvature f2 of the distortion function at the origin, and in addition has as prefactor the external shear γp. Both of these are typically small; characteristic values for the external shear in strong lens systems are γp ≲ 0.1. We have seen in Sect. 2 that distortion functions with excessive curvature lead to unphysical mass distributions, so that f2θ2 will be considerably smaller than unity in the multiple-image region. Hence, the prefactor will be smaller than about 10-2. In fact, in the example considered in the following subsection, this prefactor is of order 2 × 10-4. Furthermore, we also point out that the dominant term in the bracket (the middle one) will be small near the critical curve, since this curve will be close to the radius θE of the Einstein circle of the original axi-symmetric lens model, where  . Finally, we note that the ϕ-average of

. Finally, we note that the ϕ-average of  vanishes, because of the sine-factor, so that

vanishes, because of the sine-factor, so that  will oscillate around zero as one considers circles of constant θ. Overall, we thus expect

will oscillate around zero as one considers circles of constant θ. Overall, we thus expect  to be small, so that the difference between the deflection angle

to be small, so that the difference between the deflection angle  and the one derived from the modified surface mass density (30) will be small.

and the one derived from the modified surface mass density (30) will be small.

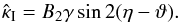

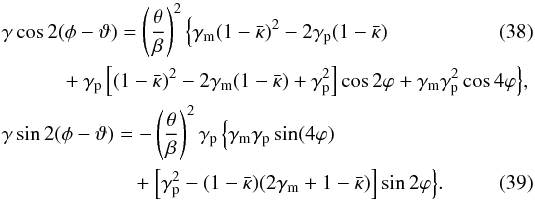

4.3. An illustrative example

Whereas a more detailed investigation of this question will be deferred to a later publication, we will illustrate the SPT with a simple example. In SS13, we found that a quadrupole lens with a mass model κ(θ) consisting of a Hernquist profile (representing the baryonic mass of a lens galaxy) and a generalized NFW profile (to approximate the central part of the dark matter halo) is almost degenerate with a model κPL(θ) corresponding to a power law with an inner core. Since the time-delay ratios do not simply scale by a constant factor, the transformation between these two mass models is not a MST. Instead, as we will show next, this transformation is an example of the SPT discussed here.

The two mass models we study hereafter are the same as in Sect. 4.2 of SS13, namely a fiducial model composed of a spherically symmetric Hernquist+generalised NFW with an external shear (γ,θγ) = (0.1,90°), and a target power-law model with a core radius θc = 0.′′1, a logarithmic (three-dimensional) slope γ′ = 2.24, and an external shear (γ,θγ) = (0.09,90°). Hereafter, we denote the lensing quantities associated to the power-law model with a hat, e.g.,  .

.

Using our fiducial mass distribution and the public lens modeling code lensmodel (v1.99; Keeton 2001), we create mock images of a uniform grid of 19 × 19 sources covering the first quadrant of the source plane from β = (βx,βy) = (0.025,0.025)″ to (βx,βy) = (0.975,0.975)″. The sources and the mock lensed images are shown in Fig. 3. As we have shown in SS13, these lensed images are also reproduced to a good accuracy with the power-law model, provided that the sources are now located at positions  . The right panel in Fig. 3 shows the offset (in arcsec) between the mock lensed images θ and the lensed images

. The right panel in Fig. 3 shows the offset (in arcsec) between the mock lensed images θ and the lensed images  corresponding to the source positions

corresponding to the source positions  . We see that the two sets of images are almost identical. Assuming an astrometric accuracy of 0.′′004 in the image plane, we have calculated an astrometric χ2 for each source, as shown in the left panel5 in Fig. 3. The two models are only approximately degenerate since χ2 deviates significantly from 0 in the vicinity of the outer caustic. The figure reveals that the degeneracy between the two models is valid for | β | ≲ 0.′′9.

. We see that the two sets of images are almost identical. Assuming an astrometric accuracy of 0.′′004 in the image plane, we have calculated an astrometric χ2 for each source, as shown in the left panel5 in Fig. 3. The two models are only approximately degenerate since χ2 deviates significantly from 0 in the vicinity of the outer caustic. The figure reveals that the degeneracy between the two models is valid for | β | ≲ 0.′′9.

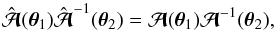

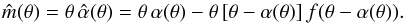

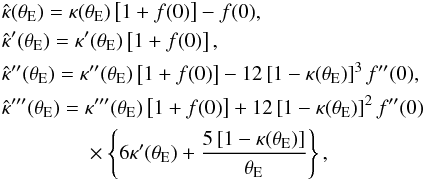

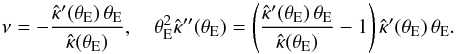

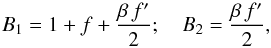

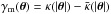

To characterize the nature of the degeneracy we first consider the relation between β and  . In case of a MST,

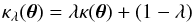

. In case of a MST,  , and λ is constant. We show in the upper panel in Fig. 4 the variation of

, and λ is constant. We show in the upper panel in Fig. 4 the variation of  with | β | and with the polar angle of the source, φ. We see that

with | β | and with the polar angle of the source, φ. We see that  at the origin, and it increases monotonically to

at the origin, and it increases monotonically to  when | β | ~ 0.′′9. This implies that for this specific example, the product θ2f2 occurring in (42) is about 4 × 10-3, yielding an asymmetry of the Jacobian

when | β | ~ 0.′′9. This implies that for this specific example, the product θ2f2 occurring in (42) is about 4 × 10-3, yielding an asymmetry of the Jacobian  of less than ~ 2 × 10-4.

of less than ~ 2 × 10-4.

The sharp decrease of the function (1 + f) for | β | ≳ 0.′′9 probably reflects the approximate character of the degeneracy between κ and  6. The change of

6. The change of  with β demonstrates that the transformation is not a MST. On the other hand, the small dependence of

with β demonstrates that the transformation is not a MST. On the other hand, the small dependence of  on φ shows that the mapping

on φ shows that the mapping  is almost isotropic, but not exactly so.

is almost isotropic, but not exactly so.

We now compare the magnification of the lensed images and the corresponding total magnification | μ | of the source. The spatial variation of the magnification ratio in the source plane is displayed in the third quadrant in Fig. 3. We see that the factor by which the magnifications are transformed is the square of the factor transforming the positions, as shown in the bottom panel in Fig. 4 which shows  normalised by

normalised by  . In other words, if

. In other words, if ![\hbox{$\hat{\vc\beta} = [1+f(\vc\beta)]\,\vc\beta$}](/articles/aa/full_html/2014/04/aa22106-13/aa22106-13-eq215.png) , the magnification has to be transformed as

, the magnification has to be transformed as ![\hbox{$\hat\mu = [1+f(\vc\beta)]^{2}\,\mu$}](/articles/aa/full_html/2014/04/aa22106-13/aa22106-13-eq216.png) . This behavior is similar to that observed for the MST, except that there is a dependence on β.

. This behavior is similar to that observed for the MST, except that there is a dependence on β.

Finally, we also display in Fig. 4 the change of the time delay  normalised by

normalised by  . While the delays should scale like the source positions in the case of a MST, they do not do so for the SPT. The ratio (

. While the delays should scale like the source positions in the case of a MST, they do not do so for the SPT. The ratio ( is almost constant but differs significantly from 1. In addition, we see that for sources interior to the inner (astroid) caustic, the time delay ratios between lensed images are not conserved. The error bars in Fig. 4 show, for each source, the spread of

is almost constant but differs significantly from 1. In addition, we see that for sources interior to the inner (astroid) caustic, the time delay ratios between lensed images are not conserved. The error bars in Fig. 4 show, for each source, the spread of  among the lensed images. This spread may reach 10% for some peculiar source positions, but generally arises from the deviation of only one of the lensed images. Owing to the accuracies on the time delays of a few percents currently achieved for quads (e.g. Fassnacht et al. 2002; Courbin et al. 2011; Tewes et al. 2013), time delay measurements in quadruply lensed systems could in the most favourable cases break the SPT independently of H0.

among the lensed images. This spread may reach 10% for some peculiar source positions, but generally arises from the deviation of only one of the lensed images. Owing to the accuracies on the time delays of a few percents currently achieved for quads (e.g. Fassnacht et al. 2002; Courbin et al. 2011; Tewes et al. 2013), time delay measurements in quadruply lensed systems could in the most favourable cases break the SPT independently of H0.

In summary, we have shown that the degeneracy between a composite and a power-law model with a finite core identified in SS13 is an example of an approximate SPT in the case of a quadrupole lens. The non-uniform rescaling of the source morphology also implies a rescaling of its surface brightness. Although this means that in principle an examination of the source should allow one to exclude some inadequate degenerate models, it is likely that, as for the example shown here, the sources corresponding to the two different models will have similarly plausible morphologies and surface brightnesses. Again, time delay ratio measurements may play a critical role in breaking the degeneracy between SPT-generated models. First, because the time delay ratios are not perfectly conserved when three time delays of the same source are observed. Second, because the time delay is not invariant under an SPT and so, if the value of the Hubble constant is assumed to be known from other observations, the degeneracy may be at least partially broken. Finally, we also note that the amplitude of the shear also gets modified by the SPT.

|

Fig. 4 Properties of an approximate SPT |

5. Discussion and conclusions

We have shown that there exists a transformation of the deflection angle in gravitational lens systems with a single source redshift which (1) leaves all strong lensing observables invariant, except the time delay; and (2) is much more general than the well-known mass-sheet transformation. For the axi-symmetric case, this new source-position transformation is exact, in the sense that there exists a surface mass density  which corresponds to the transformed deflection law

which corresponds to the transformed deflection law  . However, as mentioned before, not for every source position transformation is the resulting mass profile

. However, as mentioned before, not for every source position transformation is the resulting mass profile  physically meaningful. Nevertheless, through examples we have demonstrated that the SPT yields a great deal of freedom in obtaining transformed mass models which are monotonically decreasing and positive definite. In the general case, the transformed deflection

physically meaningful. Nevertheless, through examples we have demonstrated that the SPT yields a great deal of freedom in obtaining transformed mass models which are monotonically decreasing and positive definite. In the general case, the transformed deflection  has a curl component, which causes the resulting Jacobi matrix to attain an asymmetric contribution.

has a curl component, which causes the resulting Jacobi matrix to attain an asymmetric contribution.

We have then defined the convergence  of the transformed lens in terms of the trace of the transformed Jacobi matrix

of the transformed lens in terms of the trace of the transformed Jacobi matrix  . The deflection angle obtained from this convergence is expected to closely approximate the transformed deflection angle

. The deflection angle obtained from this convergence is expected to closely approximate the transformed deflection angle  , provided the asymmetry of

, provided the asymmetry of  is sufficiently small. Hence, in this case the mass distribution

is sufficiently small. Hence, in this case the mass distribution  will yield almost the same strong lensing predictions as the original mass profile κ.

will yield almost the same strong lensing predictions as the original mass profile κ.

An approximate agreement between the original and the transformed lensing properties is sufficient for the typical strong lens systems. These are usually modeled by simple mass profiles with a small number of parameters which fit the observed image configuration remarkably well. Exact fitting is not required, however, for at least two reasons. First, the observed image positions (and the observed brightness profile for extended images) have an observational uncertainty, which for the best optical imaging available (with HST) is on the order of ~1 / 10 of a pixel, i.e., ~5 mas, corresponding to Δθ/θE ~ 5 × 10-3 for galaxies as lenses. Higher accuracy in lens modeling is thus currently not required. Second, real mass distributions are not really smooth, but contain substructures; these substructures are almost certainly responsible for the mismatch between observed flux ratios of images, and the magnification ratios obtained from simple (i.e., smooth) lens models (e.g., Mao & Schneider 1998; Kochanek & Dalal 2004; Bradač et al. 2004; Xu et al. 2010). In addition, low-mass halos along the line-of-sight to the source may change magnifications (e.g., Metcalf 2005; Xu et al. 2012). For these reasons, flux ratios are usually not used as constraints in lens modeling. The upper mass end of the substructure can also cause positional shifts of individual images; astrometric distortions of this nature have been observed in several lens systems where the substructure was indeed identified (e.g., MG 0414+0534 – e.g., Trotter et al. 2000; Ros et al. 2000 and MG 2016+112 – e.g., Koopmans et al. 2002). Thus, independent of the accuracy of the observed image positions, for physical reasons one may not expect to reproduce the observed position to better than a few milliarcseconds with a smooth mass model. Hence, as long as the transformed deflection angle  (which yields exactly the same strong lensing properties as the original lens) and the deflection obtained from

(which yields exactly the same strong lensing properties as the original lens) and the deflection obtained from  differ by less than the smallest angular scale on which modeling by a smooth mass distribution is still meaningful, this difference is of no practical relevance.

differ by less than the smallest angular scale on which modeling by a smooth mass distribution is still meaningful, this difference is of no practical relevance.

In the near future, images of structured Einstein rings may be observed at higher resolution (i.e. 0.′′001) with ALMA (Hezaveh et al. 2013), the Extremely Large Telescope (ELT), or the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). It still has to be investigated how critical the SPT could be for sources observed at those resolutions if substructures are not explicitly included in the lens models and/or if reasonable freedom is allowed regarding the angular structure of the lens (e.g. Evans & Witt 2003; Saha & Williams 2006). Nevertheless, the expected substructure and line-of-sight inhomogeneities mentioned above will put a lower limit to the positional accuracy at which lens systems can be modeled with smooth matter distributions. In any case, since the SPT is more general than the MST, it will limit the accuracy of some applications of strong gravitational lensing such as the detection of substructures via the time-delay method (Keeton & Moustakas 2009), the estimate of H0 for systems where only one time delay is measured (Vuissoz et al. 2007; Suyu 2012), or the determination of the profile of the dark matter distribution based only on strong lensing (e.g. Cohn et al. 2001; Eichner et al. 2012). Free-form lens modeling might already give a hint of the impact of the SPT on some of these applications (Coles 2008; Paraficz & Hjorth 2010; Leier et al. 2011).

It should also be pointed out that simple mass models of strong lensing clusters typically fail to reproduce the location of multiple images at the level of ~1′′, even if the contributions of the cluster galaxies are explicitly accounted for. This level of mismatch is typically not considered to be a problem, since one expects the total mass distribution of clusters to be more complicated than that of one or a few large-scale mass components plus the mass profiles of cluster galaxies (for which simple scalings between luminosity and mass properties are employed). Here, the relative mismatch is Δθ/θE ~ 1 / 20, i.e., larger than for galaxies, and correspondingly, the required agreement between  and the deflection from

and the deflection from  is less stringent.

is less stringent.

Free-form lens models developed for studying strongly lensed sources by galaxies or clusters (e.g. Saha & Williams 2004; Diego et al. 2005; Liesenborgs et al. 2006; Coe et al. 2008) fit the lensing observables perfectly and derive ensembles of models reproducing existing data for sets of individual multiply-imaged sources. These techniques effectively explore degeneracies between lens models (Saha & Williams 2001, 2006), but with the drawback that many non-physical models (e.g., dynamically unstable or with arbitrary substructure) can be obtained. As emphasized by Coe et al. (2008), there is no unambiguous set of criteria to define a priori whether a model is physical or not. Hence, free-form modeling may sometimes worsen the impact of degeneracies by exploring a parameter space that is too large. More work is surely needed to develop schemes allowing us to explore lens degeneracies such as the SPT in a controlled way, maybe implying the combination of model-based and model-free approaches, or including perturbations around local solutions (Alard 2009).

We have illustrated the behavior of the SPT for a quadrupole lens. As an example, we have shown that in the presence of an external shear γ ~ 0.1, a mass model constituted of a baryonic component (modeled as a Hernquist profile) and of a dark matter component (modeled as a generalized NFW) can be transformed into a power-law model with a finite core. As mentioned before, this example was not constructed as an SPT, but the almost perfect degeneracy between these two mass models was found experimentally in SS13. We have shown here that this degeneracy can be traced back to the SPT; in particular, we saw that the SPT corresponding to that transformation is a spatially varying (at a level of less than one percent) and nearly isotropic contraction of the source plane positions, i.e. ![\hbox{$\hat{\vc\beta} = [1+f(\vc\beta)]\,\vc\beta$}](/articles/aa/full_html/2014/04/aa22106-13/aa22106-13-eq215.png) . We have shown that the magnifications are transformed such that

. We have shown that the magnifications are transformed such that ![\hbox{$\hat\mu = [1+f(\vc\beta)]^2\,\mu$}](/articles/aa/full_html/2014/04/aa22106-13/aa22106-13-eq237.png) , while the time delay transforms differently. In addition, the time delay ratios are not conserved when four lensed images are formed.

, while the time delay transforms differently. In addition, the time delay ratios are not conserved when four lensed images are formed.

Throughout this paper we have considered strong lensing only. The weak lensing properties are not invariant under the SPT, since it changes the weak lensing observable, i.e., the reduced shear γ/ (1 − κ), except for the special case of a MST (Schneider & Seitz 1995). Thus, the SPT is not an invariance transformation for weak lensing studies. In the strong lensing regime, if magnification information can be obtained from observations, the invariance with respect to the SPT can also be broken. The weak lensing regime is probably more relevant for clusters, where magnification can be estimated from the observed number density of background sources, though these estimates have a considerable uncertainty within the strong lensing regime of clusters.

As is the case for the MST, the degeneracy of the SPT can be broken if sources at different redshifts are lensed by the same deflector (Bradač et al. 2004), and this effect will be

stronger the more different the source redshifts are. However, the number of known galaxy-scales lens systems with multiple source redshifts is small, and it remains to be seen how well the degeneracies are broken in these cases.

In a future work, we aim to quantify the consequences of the asymmetry of  in more detail, and thus to find criteria to derive which kind of SPTs are allowed for a given tolerance in the changes of image positions.

in more detail, and thus to find criteria to derive which kind of SPTs are allowed for a given tolerance in the changes of image positions.

For any source position β, at least one image θ exists, according to the odd-number theorem (Burke 1981).

If the mapping  is not one-to-one, then there exist pairs of positions β(1) and β(2) that are mapped onto the same

is not one-to-one, then there exist pairs of positions β(1) and β(2) that are mapped onto the same  . This implies that all images

. This implies that all images  and

and  that correspond to these two different source positions are images of the same source

that correspond to these two different source positions are images of the same source  in the new mapping, modifying the pairing of images. Hence, we will assume detℬ> 0 in the following.

in the new mapping, modifying the pairing of images. Hence, we will assume detℬ> 0 in the following.

In general, such a large-scale perturber will also induce some external convergence. However, for simplicity we will neglect this effect here, since it can be easily scaled out by a mass-sheet transformation (see, e.g., Schneider 2006).

We point out here that there was no fine-tuning involved in constructing this special example, i.e., this example from SS13 turned out to be almost degenerate with a cored power-law mass profile. The fact that it almost corresponds to an SPT is accidental. Some fine-tuning of the mass profiles, equivalent to a fine-tuning of the function  , would enable an even better agreement between the lensing properties of the two models.

, would enable an even better agreement between the lensing properties of the two models.

Acknowledgments

Part of this work was supported by the German Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG project number SL172/1-1.

References

- Alard, C. 2009, A&A, 506, 609 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Bartelmann, M. 2010, Class. Quant. Grav., 27, 233001 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bradač, M., Schneider, P., Lombardi, M., et al. 2004, A&A, 423, 797 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Burke, W. L. 1981, ApJ, 244, L1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Coe, D., Fuselier, E., Benítez, N., et al. 2008, ApJ, 681, 814 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn, J. D., Kochanek, C. S., McLeod, B. A., & Keeton, C. R. 2001, ApJ, 554, 1216 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Coles, J. 2008, ApJ, 679, 17 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Courbin, F., Chantry, V., Revaz, Y., et al. 2011, A&A, 536, A53 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Diego, J. M., Sandvik, H. B., Protopapas, P., et al. 2005, MNRAS, 362, 1247 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Eichner, T., Seitz, S., & Bauer, A. 2012, MNRAS, 427, 1918 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Evans, N. W., & Witt, H. J. 2003, MNRAS, 345, 1351 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Falco, E. E., Gorenstein, M. V., & Shapiro, I. I. 1985, ApJ, 289, L1 [Google Scholar]

- Fassnacht, C. D., Xanthopoulos, E., Koopmans, L. V. E., & Rusin, D. 2002, ApJ, 581, 823 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hezaveh, Y., Dalal, N., Holder, G., et al. 2013, ApJ, 767, 9 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Keeton, C. R. 2001 [arXiv:astro-ph/0102340] [Google Scholar]

- Keeton, C. R., & Moustakas, L. A. 2009, ApJ, 699, 1720 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanek, C. S. 2006, in Saas-Fee Advanced Course 33: Gravitational Lensing: Strong, Weak and Micro, eds. G. Meylan, P. Jetzer, P. North, et al. (Berlin: Springer), 91 [Google Scholar]

- Kochanek, C. S., & Dalal, N. 2004, ApJ, 610, 69 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Koopmans, L. V. E., Garrett, M. A., Blandford, R. D., et al. 2002, MNRAS, 334, 39 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Leier, D., Ferreras, I., Saha, P., & Falco, E. E. 2011, ApJ, 740, 97 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Liesenborgs, J., & De Rijcke, S. 2012, MNRAS, 425, 1772 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Liesenborgs, J., De Rijcke, S., & Dejonghe, H. 2006, MNRAS, 367, 1209 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mao, S., & Schneider, P. 1998, MNRAS, 295, 587 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Metcalf, R. B. 2005, ApJ, 629, 673 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Paraficz, D., & Hjorth, J. 2010, ApJ, 712, 1378 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Read, J. I., Saha, P., & Macciò, A. V. 2007, ApJ, 667, 645 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ros, E., Guirado, J. C., Marcaide, J. M., et al. 2000, A&A, 362, 845 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Saha, P., & Williams, L. L. R. 1997, MNRAS, 292, 148 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Saha, P., & Williams, L. L. R. 2001, AJ, 122, 585 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Saha, P., & Williams, L. L. R. 2004, AJ, 127, 2604 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Saha, P., & Williams, L. L. R. 2006, ApJ, 653, 936 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, P. 2006, in Saas-Fee Advanced Course 33: Gravitational Lensing: Strong, Weak and Micro, eds. G. Meylan, P. Jetzer, & P. North (Berlin: Springer), 1 [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, P., & Seitz, C. 1995, A&A, 294, 411 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, P., & Sluse, D. 2013, A&A, 559, A37 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Suyu, S. H. 2012, MNRAS, 426, 868 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Suyu, S. H., Hensel, S. W., McKean, J. P., et al. 2012, ApJ, 750, 10 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tewes, M., Courbin, F., Meylan, G., et al. 2013, A&A, 556, A22 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Trotter, C. S., Winn, J. N., & Hewitt, J. N. 2000, ApJ, 535, 671 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Vuissoz, C., Courbin, F., Sluse, D., et al. 2007, A&A, 464, 845 [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D. D., Mao, S., Cooper, A. P., et al. 2010, MNRAS, 408, 1721 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D. D., Mao, S., Cooper, A. P., et al. 2012, MNRAS, 421, 2553 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Axi-symmetric example of an SPT between a non-singular isothermal sphere (solid blue curve), with core θc = 0.1θE, and other mass profiles. The other curves are transformed mass profiles, using the SPT, with different deformation functions f(β), all satisfying the power-law condition (20), and with slope ν = 0.5 (flatter curves) and ν = 1.4 (steeper curves). The dashed black curves correspond to the polynomial f(β) = f0 + f2β2/ 2, the red curves to |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Second example of an SPT, in the axi-symmetric case, between an SIS with mass distribution κ(θ) and other mass distributions |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 Right: set of mock lensed images produced by our fiducial lens model (using a grid of source positions shown in the first quadrant of the left panel). The color-coding shows the offset in arcseconds, between the original image positions and those found with the power-law model. Left: first quadrant (upper right): grid of source positions lensed with our fiducial model to produce the images shown in the right panel. The color-coding indicates the χ2 associated with each source, assuming an astrometric uncertainty on the image position of σθx,y = 0.004′′. In the third quadrant (lower left), the sources do not have corresponding lensed images on the right panel, and are colored as a function of the ratio of their total magnification as derived with the power-law and the fiducial models (i.e., |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4 Properties of an approximate SPT |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.

![\hbox{$f(\beta)=f_0+\beta_0^2 f_2 \beta^2/[2(\beta^2+\beta_0^2)]$}](/articles/aa/full_html/2014/04/aa22106-13/aa22106-13-eq94.png)