| Issue |

A&A

Volume 562, February 2014

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A76 | |

| Number of page(s) | 10 | |

| Section | Interstellar and circumstellar matter | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201322989 | |

| Published online | 07 February 2014 | |

Dust origin in late-type dwarf galaxies: ISM growth vs. type II supernovae

1

Max Planck Institute for Astronomy,

Königstuhl 17,

69117

Heidelberg,

Germany

e-mail:

zhukovska@mpia.de

2

Zentrum für Astronomie der Universität Heidelberg, Institut für

Theoretische Astrophysik, Albert-Ueberle-Str. 2, 69120

Heidelberg,

Germany

Received:

6

November

2013

Accepted:

3

January

2014

Context.

Aims. We re-evaluate the roles of different dust sources in dust production as a function of metallicity in late-type dwarf galaxies, with the goal of understanding the relation between dust content and metallicity.

Methods. The dust content of late-type dwarf galaxies with episodic star formation is studied with a multicomponent model of dust evolution, which includes dust input from AGB stars, type II SNe, and dust growth by accretion of atoms in the ISM.

Results. Dust growth in the ISM becomes an important dust source in dwarf galaxies on the timescale of 108 to a few 109 yr. It increases the dust-to-gas mass ratio (DGR) during post-burst evolution, unlike type II SNe, which eject grains into the ISM only during starbursts. Before the dust growth in the ISM overtakes the dust production, AGB stars can be major sources of dust in metal-poor dwarf galaxies. Our models reproduce the relation between the DGR and oxygen abundance, derived from observations of a large sample of dwarf galaxies. The steep decrease in the DGR at low metallicities is explained by the relatively low efficiency of dust condensation in stars. The scatter observed at higher metallicities is determined mainly by different metallicities for the transition from stardust- to ISM-growth-dominated dust production, depending on the star formation history. In galaxies with episodic star formation, additional dispersion in the DGR is introduced by grain destruction during starbursts, followed by an increase in the dust mass owing to dust growth in the ISM during post-burst evolution. We find that the carbon-to-silicate ratio changes dramatically when the ISM growth becomes the dominant dust source, therefore this ratio can be used as an indicator of the transition.

Conclusions. The observed relation of the DGR versus metallicity in dwarf galaxies favours low-condensation efficiencies in type II SNe, together with an increase in the total dust mass by means of dust growth in the ISM.

Key words: galaxies: dwarf / galaxies: ISM / dust, extinction

© ESO, 2014

1. Introduction

The origin of interstellar grains has been highly debated. Grains are formed in the stellar winds of evolved stars and expanding ejecta of supernovae, which have been considered the major sites of dust formation. However, high depletions of gas-phase element abundances in dense gas cannot be reproduced only with the stellar dust production. They require additional dust growth by accretion of gas-phase species on grain surface directly in the interstellar medium (ISM; e.g., Dwek & Scalo 1980; Weingartner & Draine 1999; Jenkins 2009). Indeed, dust growth in the ISM is considered the dominant dust source in the Milky Way (Dwek 1998; Zhukovska et al. 2008; Draine 2009). The low values of element depletions in diffuse gas indicate efficient dust destruction by supernova shocks (Draine & Salpeter 1979; Barlow 1978; Dwek & Scalo 1980; Jones et al. 1994, 1996; Jones & Nuth 2011).

Details of the dust growth in the ISM are poorly understood (Draine 2009; but see Krasnokutski et al.

2013). It clearly depends on the collision rates of dust-forming gas species with

grain surfaces, hence it strongly depends on the gas-phase element abundances, and thus on

the metallicity. In the Milky Way, the critical metallicity for the efficient dust growth by

accretion is Z ~ 0.001 for silicate and somewhat higher for carbonaceous

and iron grains, 0.004 and 0.014, respectively (Zhukovska

2008; Zhukovska & Gail 2009).

Recently, Asano et al. (2013) have studied the

critical role of metallicity for the dust growth in galaxies with the continuous star

formation rate. They find that it depends on the star formation timescales,

.

.

In the present paper, we investigate the transition from stardust-dominated to ISM growth-dominated dust production in late-type dwarf galaxies, blue compact dwarf (BCD), and dwarf irregulars. They are gas-rich, relatively unevolved systems, with the metallicities varying over a wide range down to the lowest values known in the local Universe (Z ~ 1/40 Z⊙ in BCD SBS 0335-052, Izotov et al. 1997). The upper range of metallicities in BCDs, 12 + log (O/H) ~ 8.4 (Izotov & Thuan 1999), slightly exceeds the metallicity of the Large Magellanic Cloud, where the dust growth in the ISM is expected to be important (Matsuura et al. 2009; Zhukovska & Henning 2013). Star formation in dwarf galaxies occurs in bursts separated by quiescent periods (e.g., Recchi et al. 2002; Tolstoy et al. 2009; Lanfranchi & Matteucci 2003; Yin et al. 2011; Bradamante et al. 1998), therefore they permit studying the effect of fast chemical enrichment during starbursts and slow post-burst galactic evolution on its dust content.

Despite the low metallicities, late-type dwarfs indicate the presence of substantial amounts of dust characterised by large dispersion in the dust-to-gas ratio (DGR; e.g., Lisenfeld & Ferrara 1998). The dust-to-gas ratio of a sample of galaxies plotted as a function of oxygen abundances provides an insight into the relation between dust-to-gas ratio and metallicity. This relation is crucial for detailed numerical hydrodynamical simulations of the ISM evolution, for which dust abundance is usually taken as a fixed fraction of metals. This assumption can be justified for spiral galaxies with solar and supersolar metallicities, but not for metal-poor dwarf galaxies (e.g., Dwek 1998; Lisenfeld & Ferrara 1998; Draine et al. 2007; Engelbracht et al. 2008; Galliano et al. 2005, 2011). Engelbracht et al. (2008) find that the relation between the DGR and oxygen abundance 12 + log (O/H) in dwarf galaxies flattens out at low metallicities 12 + log (O/H) < 8. However, more recent studies have shown that it actually steepens at low metallicities (Herrera-Camus et al. 2012; Galametz et al. 2011; Rémy-Ruyer et al. 2014). We will investigate how these variations in gas-to-dust ratio can be explained with the evolutionary dust models.

Dust in dwarf galaxies has been studied with the dust and gas chemical evolution models in the literature (Lisenfeld & Ferrara 1998; Hirashita 1999; Hirashita et al. 2002a,b; Calura et al. 2008b). These models ascribe the origin of interstellar dust to the SN type II (Lisenfeld & Ferrara 1998; Hirashita et al. 2002a), which require quite a high degree of condensation in dust in SN ejecta, about 10% (Hirashita 1999; Hirashita et al. 2002b). This value is significantly higher than estimates from various recent observational and theoretical studies (Bianchi & Schneider 2007; Ercolano et al. 2007; Zhukovska et al. 2008; Kozasa et al. 2009; Cherchneff & Dwek 2009, 2010; Fox et al. 2010; but see Matsuura et al. 2011; Gomez et al. 2012; Lakicevic et al. 2011). Therefore, dust growth by accretion in the ISM may be more important in dwarf galaxies than previously thought.

Our main goal is to investigate the relation between dust content and metallicity and its dependence on the dominant dust sources in late-type dwarf galaxies. Since the interstellar dust mixture is determined by the interplay of dust production by stellar sources and by dust growth and destruction in the ISM, we use a model of the lifecycle of dust species of different origins, which has been used to study the dust content in the solar neighbourhood, Milky Way disk, and Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC; Zhukovska 2008; Zhukovska et al. 2008; Zhukovska & Henning 2013). With this model modified for the evolution of dwarf galaxies, we re-evaluate the roles of individual dust sources in galaxies with various star formation histories. In particular, we establish when the dust growth in the ISM begins to dominate the dust production in model galaxies, and subsequent changes in the interstellar dust properties.

The paper is organized as follows. Evolution models of dust and gas for dwarf galaxies are described in Sect. 2. Section 3 presents the metallicity evolution in model galaxies and the resulting variations in the accretion timescales for dust growth in the ISM. In Sect. 4, we present results of calculations of the DGR evolution, verify our models by comparison with the relation between dust-to-gas ratio and oxygen abundance derived from observations, and discuss the dependence of our results on various galactic model parameters. Finally, conclusions are presented in Sect. 5.

2. Model prescriptions

2.1. Galactic evolution

A model of the chemical evolution of the main dust-forming elements provides a good basis for the dust evolution model, since it naturally includes the abundance constraints for the interstellar dust mixture (Dwek & Scalo 1980; Dwek 1998). We adopt the model of the lifecycle of dust in the ISM introduced for the solar neighbourhood in Zhukovska et al. (2008). Below we describe main modification needed for a dwarf galaxy model.

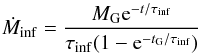

In contrast to spiral galaxies, dwarf galaxies have small sizes and no large metallicity

gradients, so they can be modelled in one-zone approximation, with all quantities averaged

for the whole galaxy. Therefore, equations of chemical evolution are solved for masses of

elements in gas and dust instead of the surface densities used in Zhukovska et al. (2008). We assume that a model galaxy is formed by gas

infall with the infall rate  (1)on

a short timescale of τinf = 0.3 Gyr;

MG is the mass of gas accreted by infall for the whole time

of galactic evolution tG, which is set to 13 Gyr in this

paper. We assume that the infalling gas has a primordial composition (zero initial

metallicity) following chemical and chemodynamical evolution models of dwarf galaxies

(e.g., Searle et al. 1973; Recchi et al. 2001, 2002; Lanfranchi & Matteucci 2003; Romano et al. 2006; Yin

et al. 2011). Alternatively, some chemical evolution models assume that the

infalling gas is pre-enriched to Z ~ 10-4−10-3

with type II SN-like enhanced [α/Fe] ratio based on

metallicities of damped Lyα systems (e.g., Bekki & Tsujimoto 2012; Tsujimoto et al.

2010). We discuss how this assumption affects the model predictions in Sect.

4.5.1.

(1)on

a short timescale of τinf = 0.3 Gyr;

MG is the mass of gas accreted by infall for the whole time

of galactic evolution tG, which is set to 13 Gyr in this

paper. We assume that the infalling gas has a primordial composition (zero initial

metallicity) following chemical and chemodynamical evolution models of dwarf galaxies

(e.g., Searle et al. 1973; Recchi et al. 2001, 2002; Lanfranchi & Matteucci 2003; Romano et al. 2006; Yin

et al. 2011). Alternatively, some chemical evolution models assume that the

infalling gas is pre-enriched to Z ~ 10-4−10-3

with type II SN-like enhanced [α/Fe] ratio based on

metallicities of damped Lyα systems (e.g., Bekki & Tsujimoto 2012; Tsujimoto et al.

2010). We discuss how this assumption affects the model predictions in Sect.

4.5.1.

Main parameters of dwarf galaxy models.

Star formation histories in late-type dwarf galaxies reconstructed from their

colour–magnitude diagrams display a number of bursts of different durations separated by

quiescent phases (Tolstoy et al. 2009; Martín-Manjón et al. 2011,and references therein).

Yin et al. (2011) find that the present-day

observational constraints for chemical evolution of late-type dwarfs can be fitted with

bursting models with no more than ten bursts and τSF ~ 2 Gyr.

BCDs with continuous star formation should not be the majority of BCD population (Yin et al. 2011). Therefore, we adopt an episodic star

formation in which long quiescent phases are separated by relatively short bursts of star

formation occurring on a much shorter timescale τSF. The

assumed star formation rate is linearly proportional to the gas mass

(2)We consider six

starburst models with episodic star formation, which differ in the number of bursts

nburst, their duration dtburst,

timescales of star formation τSF and infall

τinf (Table 1). It is

assumed that all models are entering a starburst at the present time

t = 13 Gyr. The number of past starburst experienced at evolution times

tburst is listed in Table 1. The burst duration is varied from 50 to 500 Myr. The star formation timescale

during starbursts τSF is set to 2 Gyr in all burst models,

with exception of Models 3 and 6, for which it is reduced to 0.2 Gyr to study the effect

of faster chemical enrichment. Model 3 does not represent a gas-rich starburst dwarf

galaxy because it has a too short τSF combined with a long

starburst duration, resulting in the high metallicity and low gas fractions after initial

starbursts. It is a model of evolved galaxy included for comparison. During the quiescence

phases in starburst galaxies, τSF is set to 200 Gyr. A

non-zero star formation rate between starbursts is commensurate with the star formation

histories of late-type dwarf galaxies derived from colour–magnitude diagrams (Tolstoy et al. 2009, and references therein). The

reference value for the infall timescale is 0.3 Gyr in all models except Model 7, for

which the value of 1 Gyr is taken to illustrate the effect of slower galaxy formation.

Model 4 with the continuous star formation on the timescale

τSF = 10 Gyr is only included for comparison.

(2)We consider six

starburst models with episodic star formation, which differ in the number of bursts

nburst, their duration dtburst,

timescales of star formation τSF and infall

τinf (Table 1). It is

assumed that all models are entering a starburst at the present time

t = 13 Gyr. The number of past starburst experienced at evolution times

tburst is listed in Table 1. The burst duration is varied from 50 to 500 Myr. The star formation timescale

during starbursts τSF is set to 2 Gyr in all burst models,

with exception of Models 3 and 6, for which it is reduced to 0.2 Gyr to study the effect

of faster chemical enrichment. Model 3 does not represent a gas-rich starburst dwarf

galaxy because it has a too short τSF combined with a long

starburst duration, resulting in the high metallicity and low gas fractions after initial

starbursts. It is a model of evolved galaxy included for comparison. During the quiescence

phases in starburst galaxies, τSF is set to 200 Gyr. A

non-zero star formation rate between starbursts is commensurate with the star formation

histories of late-type dwarf galaxies derived from colour–magnitude diagrams (Tolstoy et al. 2009, and references therein). The

reference value for the infall timescale is 0.3 Gyr in all models except Model 7, for

which the value of 1 Gyr is taken to illustrate the effect of slower galaxy formation.

Model 4 with the continuous star formation on the timescale

τSF = 10 Gyr is only included for comparison.

2.1.1. Galactic winds

Galactic winds drive metals from the ISM and reduce its metallicity. Owing to their shallower gravitational potential wells, dwarf galaxies often experience galactic winds triggered by energetic stellar feedback (see Recchi 2013, for a recent review). In non-selective wind models, the entire ISM is affected by winds, and the gas loss is proportional to the star formation rate (e.g., Bradamante et al. 1998; Lanfranchi & Matteucci 2003; Calura et al. 2008a). Detailed dynamical models show that freshly produced metals from SNe are expelled by galactic winds more efficiently than the rest of the ISM (differential winds, Mac Low & Ferrara 1999; Recchi et al. 2004). Metal-enhanced galactic winds are required to explain recent chemical abundance constraints derived for dwarf galaxies (Yin et al. 2011).

In addition to dependence on galactic mass (e.g., Bradamante et al. 1998), the efficiency of galactic winds depends on many

other galactic parameters, in particular, on luminosity, efficiency of thermalisation of

energy from type II and Ia SNe in the ISM, and geometry of the gas distribution (Recchi et al. 2001; Recchi & Hensler 2013). To reduce the number of free parameters, we do

not include galactic winds in the reference models and study their impact on dust

content separately in Sect. 4.5.2. We follow Bekki & Tsujimoto (2012), who adopt a

selective wind model with the fixed fraction of expelled SN II ejecta

treated as a free

parameter. Hydrodynamic simulations of dwarf galaxy evolution indicate that metals from

SN Ia are more easily removed from the galaxy, because they are ejected into a hot

rarefied bubble created by previous SNe (Recchi et al.

2001, 2002; Recchi & Hensler 2013). Therefore, in the present work,

different values of

treated as a free

parameter. Hydrodynamic simulations of dwarf galaxy evolution indicate that metals from

SN Ia are more easily removed from the galaxy, because they are ejected into a hot

rarefied bubble created by previous SNe (Recchi et al.

2001, 2002; Recchi & Hensler 2013). Therefore, in the present work,

different values of  are chosen for SN

II and SN Ia,

are chosen for SN

II and SN Ia,  and

and

, respectively.

, respectively.

2.2. Dust model

We adopt a multicomponent model following individual evolutions of grains of different origin (SNII, SNIa, AGB stars, and ISM-grown dust) (Zhukovska et al. 2008). To account for the dust condensed in stellar winds of AGB stars, the mass- and metallicity-dependent dust yields are taken from calculations performed by Ferrarotti & Gail (2006) and Zhukovska et al. (2008). Dust input from AGB stars Z ≲ Z⊙ in these models is dominated by carbonaceous dust.

For type II SNe, we adopt the condensation efficiencies (fractions of key chemical element ejected by all SNe in dust) from Zhukovska (2008), ηsil = 10-3, ηSiC = 3 × 10-4, and ηcar = 0.15 for silicate, SiC, and carbonaceous dust, respectively. These values should not be directly compared with the values derived from observations of dust condensation in SN ejecta, because the latter provides an upper value before part of dust is destroyed in reverse SN shocks. For condensation efficiencies adopted here SN dust is also dominated by carbon-rich grains, therefore the stardust mixture consists mainly of carbonaceous grains in our model. Since the efficiency of dust formation and survival in type II SNe are still being debated, we investigate how much higher values of the condensation efficiencies, ηsil = ηSiC = ηcar = 0.5 can affect the dust-to-gas ratio evolution in Sect. 4.3.2.

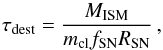

2.2.1. Dust destruction

We follow Zhukovska et al. (2008) to model the

processing of grains (destruction and mantle accretion) in the ISM. Grains are destroyed

in the ISM by SN blast waves on the timescale (McKee

1989)  (3)where

mcl is the mass of gas that is completely cleared of dust

by a single SN explosion, fSN is the fraction of all SNe

destroying dust, and RSN the total rate of SNe. In contrast

to spiral galaxies, SN Ia may be important for the dust destruction during quiescent

phases in a dwarf galaxy with episodic star formation. The

fSN is introduced to account for correlated SNe that

explode in a bubble created by previous SNe and therefore are less efficient in dust

destruction. We assume that they destroy 10% of the dust compared to a single SN (McKee 1989). We adopt the value of

fSN = 0.35 derived by Zhukovska & Henning (2013) using the observed fraction of field OB

stars in the LMC, a dwarf galaxy in the phase of active star formation. For

mcl, we adopt the values of 1300

M⊙ for carbon and iron dust and 1600

M⊙ for silicate dust, which were also estimated for the

LMC in Zhukovska & Henning (2013).

(3)where

mcl is the mass of gas that is completely cleared of dust

by a single SN explosion, fSN is the fraction of all SNe

destroying dust, and RSN the total rate of SNe. In contrast

to spiral galaxies, SN Ia may be important for the dust destruction during quiescent

phases in a dwarf galaxy with episodic star formation. The

fSN is introduced to account for correlated SNe that

explode in a bubble created by previous SNe and therefore are less efficient in dust

destruction. We assume that they destroy 10% of the dust compared to a single SN (McKee 1989). We adopt the value of

fSN = 0.35 derived by Zhukovska & Henning (2013) using the observed fraction of field OB

stars in the LMC, a dwarf galaxy in the phase of active star formation. For

mcl, we adopt the values of 1300

M⊙ for carbon and iron dust and 1600

M⊙ for silicate dust, which were also estimated for the

LMC in Zhukovska & Henning (2013).

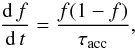

2.2.2. Dust growth in the ISM

We assume that dust growth occurs by selective accretion of gas species in dense clouds on existing grains in the sense that carbon atoms stick to the carbonaceous grains and Si, Fe, Mg, and O stick to the silicate grain surfaces (Draine 2009). A model for the dust growth adopted here is described in Zhukovska et al. (2008), and we direct the reader to the original publication for details. Dense clouds in our model are characterised by the temperature Tcl, the particle number density n, the mass fraction relatively to the total gas mass Xcl, and lifetime τexch. The τexch is also a timescale of exchange between dense and diffuse components of the ISM.

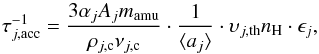

Grain growth is determined by collisions of some key element (growth species) with

grain surfaces. The equation for the condensation degree of a dust-forming species in a

dense cloud is  (4)where

τacc is the accretion timescale, and it is the key

quantity for dust growth. For the dust species of type j, it is

(4)where

τacc is the accretion timescale, and it is the key

quantity for dust growth. For the dust species of type j, it is

(5)where

αj is the sticking efficiency to the

grain surface, Aj the atomic weight of one

formula unit of the dust species, ρj,c is

the density and νj,c the number of atoms of

the key element contained in the formula unit of the condensed phase,

⟨ aj ⟩ the average grain radius,

υj,th the thermal speed of the growth

species, nH the number density of H nuclei in clouds, and

ϵj the element abundance of the key

species.

(5)where

αj is the sticking efficiency to the

grain surface, Aj the atomic weight of one

formula unit of the dust species, ρj,c is

the density and νj,c the number of atoms of

the key element contained in the formula unit of the condensed phase,

⟨ aj ⟩ the average grain radius,

υj,th the thermal speed of the growth

species, nH the number density of H nuclei in clouds, and

ϵj the element abundance of the key

species.

Because only a small fraction of the ISM resides in dense gas in dwarf galaxies (e.g.,

Leroy et al. 2005), many timescales are

required to cycle all ISM through clouds on an “effective” exchange time  (6)The dust production

rate is

(6)The dust production

rate is ![\begin{equation} G_{j,\rm d}={1\over\tau_{\rm exch,eff}}\Bigl[\,f_{j,\rm ret}M_{j,\rm d,max}- M_{j,\rm d}\,\Bigr]\cdot \label{eq:DuProdInCloud} \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2014/02/aa22989-13/aa22989-13-eq54.png) (7)where

fj,ret is the condensation degree for

growth species of kind j after cloud dispersal,

Mj,d,max is the

maximum possible dust mass assuming complete condensation, and

Mj,d the current average dust mass. For

fj,ret, we adopt an approximated formula

given by Eq. (45) in Zhukovska et al.

(2008)

(7)where

fj,ret is the condensation degree for

growth species of kind j after cloud dispersal,

Mj,d,max is the

maximum possible dust mass assuming complete condensation, and

Mj,d the current average dust mass. For

fj,ret, we adopt an approximated formula

given by Eq. (45) in Zhukovska et al.

(2008)![\begin{equation} f_{j,\rm ret}(t) =\left[ \left( f_{j,0}(t) ( 1+ \tau_{\rm exch}/ \tau_{j,{\rm acc}} ) \right)^{-2} +1 \right]^{-{1/2}}, \label{eq:fret} \end{equation}](/articles/aa/full_html/2014/02/aa22989-13/aa22989-13-eq58.png) (8)where

fj,0 is the initial degree of

condensation for species j.

(8)where

fj,0 is the initial degree of

condensation for species j.

The growth timescale τj,acc given by Eq. (5) is connected to the chemical enrichment of the cold phase through the element abundance of the key element ϵj. We consider growth in the ISM of three dust species (silicate, carbonaceous, and iron grains) and adopt the same values for the condensed phase parameters as described in Zhukovska et al. (2008).

For the grain size distribution, we assume a power-law distribution a−q with the index q = 3.5 with the minimum and maximum grain sizes amin = 0.005 μm and amax = 0.25 μm, respectively (Mathis et al. 1977, hereafter MRN), which yields ⟨ a ⟩ = 0.035 μm. Nozawa & Fukugita (2013) have recently confirmed that a simple MRN graphite-silicate grain mixture with amax = 0.24 ± 0.05 μm reproduces the extinction curves of both the Milky Way and Small Magellanic Cloud, which led the authors to suggest that the power law a-3.5 is a generic power law expected from the collisional equilibrium. Kuo & Hirashita (2012) note that variations in the grain size distribution can be important for the dust growth in the ISM. Here we do not consider the effect of these variations and restrict our study to the impact of various galactic parameters and the chemical evolution on the dust content.

Dwarf galaxies exhibit the multiphase ISM structure dominated by neutral gas. There are a few detections of molecular gas in metal-poor dwarfs, because its main tracer, the CO molecule, is very difficult to detect at low metallicities (e.g., Leroy et al. 2005, 2009; Schruba et al. 2012). For Xcl in reference models, a value of 0.10 is adopted based on the ratio of median values of H i and H2 masses in the galaxy sample in Leroy et al. (2005). However, the molecular gas fraction should be higher during a starburst and decreases afterwards due to stellar feedback (e.g., Melioli & de Gouveia Dal Pino 2004). McQuinn et al. (2012) indirectly confirm the presence of significant amounts of molecular gas in nearby starburst dwarf galaxies at the onset of the starbursts required to explain high stellar surface densities and relatively low surface densities of atomic gas. Therefore, we inspect how variations in Xcl affect the dust growth in Sect. 4.5.3, assuming that Xcl varies from 0.01 during quiescent phases up to 0.5 during starbursts. For τexch, a value of 10 Myr is adopted. Our reference value for physical conditions in clouds are 50 K for Tcl and 103 cm-3 for nH.

|

Fig. 1 Time evolution of oxygen abundance for different dwarf galaxy models (Table 1). Depending on the star formation history, the same value of O abundance can be reached at very different instants. |

3. Metallicity and accretion timescales

Oxygen is the most abundant element in galaxies after H and He, and it is the main constituent of the silicate dust. The abundance of oxygen is easier to determine than for other heavy elements, so it is commonly used as a metallicity indicator.

The results of calculations of the oxygen abundance evolution for model dwarf galaxies (Table 1) are shown in Fig. 1. The O abundance undergoes a complex evolution in galaxies with bursting star formation in contrast to Model 4 with continuous star formation. Since oxygen is mainly produced by massive stars, its abundance increases stepwise during each star formation burst. In Models 1–3, the O abundance in the ISM decreases between the first and the second bursts of star formation owing to the infall of primordial gas. In Model 7, which is identical to Model 1 with the exception of the longer infall timescale τinf, a dip in the O abundance is only 0.2 dex higher than in Model 1. This difference is reduced in later enrichment episodes, demonstrating a weak dependence of the ISM metallicity on our choice of τinf value. At later evolution times, the infall rate is negligible, and oxygen evolution is determined by the duration and strength of bursts. In Model 1, it increases between bursts owing to the quiescent star formation. Interestingly, in Model 3, 12 + log (O/H) decreases during the quiescent phases because of the mass return from metal-poor low-mass stars formed during early galactic evolution at lower metallicities. Metallicity in their envelopes is not noticeably modified by dredge-ups during post-main sequence evolution, therefore their mass loss reduces the total ISM metallicity in the presented highly evolved model. It is not the case for a typical late-type dwarf, though.

Galactic chemical evolution determines the variations in the accretion (growth) timescales

τacc controlling the dust production rates in the ISM. Time

variations of τacc for silicate and carbon dust for Models 1–3

are shown in Fig. 2a. Growth timescales for silicate

and carbonaceous grains demonstrate different behaviours:

evolution

reflects stepwise changes in metallicity with each starburst (Fig. 1), while

evolution

reflects stepwise changes in metallicity with each starburst (Fig. 1), while  decreases

smoothly on a longer timescale because of the delayed carbon production by low-mass stars.

Initially,

decreases

smoothly on a longer timescale because of the delayed carbon production by low-mass stars.

Initially,  , but after

1 Gyr in Model 1 and 2 and 300 Myr in Model 3,

, but after

1 Gyr in Model 1 and 2 and 300 Myr in Model 3,  becomes

shorter than

becomes

shorter than  . Efficient

growth in the dense clouds is expected, when τacc is smaller

than τexch,eff given by Eq. (6), which equals to 90 Myr for our reference

models.

. Efficient

growth in the dense clouds is expected, when τacc is smaller

than τexch,eff given by Eq. (6), which equals to 90 Myr for our reference

models.

Figure 3a clearly demonstrates that, in contrast to

, the growth

timescales for carbon grains vary significantly for the same values of metallicities

depending on the SFH because of the delayed enrichment of the ISM with carbon by long-lived

low-mass stars.

, the growth

timescales for carbon grains vary significantly for the same values of metallicities

depending on the SFH because of the delayed enrichment of the ISM with carbon by long-lived

low-mass stars.

|

Fig. 2 a) Time evolution of accretion time scales for silicate and carbonaceous grains (thin and thick lines) for Models 1–3 (solid, long-dashed and short-dashed lines, respectively). b) Dust-to-gas mass ratio (DGR) evolution with time from the onset of galaxy formation for Models 1–3 shown with the same line types as in the top panel. Thick and thin lines show the total DGR and the DGR calculated with only the ISM-grown dust. |

4. Results/discussion

In the following we present results of the calculations of dust evolution in the model dwarf galaxies with various star formation histories (Table 1). The dominant dust sources and corresponding values of the dust-to-gas ratio during galactic evolution are discussed in detail for Models 1 to 3, which encompass a wide range of star formation rates. Then, we compare the relation between the dust-to-gas ratio and oxygen abundance for all models with that derived from observations of a dwarf galaxy sample.

4.1. Dust-to-gas ratio evolution and dust sources

Evolution of the dust-to-gas mass ratio (DGR) with time and metallicity for Models 1 to 3 is shown in Figs. 2b and 3b, respectively. The figures display both the total DGR and the DGR due to the ISM-grown dust component.

A common feature of the models in Fig. 2b is a plateau at DGR ≲ 10-5 at early epochs (low metallicities) followed by a steep rise due to the increasing importance of dust growth in the ISM. When dust-forming elements (Si, Mg, Fe) in the ISM are almost completely condensed in dust, the growth process reaches saturation. For continuous star formation, Asano et al. (2013) points that in the saturation regime, various evolution models converge in DGR vs. Z plot to a simple linear dependence. The value of the dust-to-metal ratio is then determined by the fraction of dust-forming elements available in the ISM, which does not strongly depend on the chemical evolution and is close to the 0.4 found in spiral galaxies (Dwek 1998; Draine et al. 2007; James et al. 2002). Models of dust growth adopted here combined with bursting star formation scenarios also converge to the linear dependence of the DGR on metallicity (Fig. 3b), but the moment when it happens depends not only on the amount of metals as in models with continuous star formation (Asano et al. 2013), but also on post-burst galactic evolution.

The DGR evolution in model dwarf galaxies demonstrates stepwise changes with metallicity, most clearly seen in Model 1 representing a typical gas-rich dwarf galaxy (Fig. 3b). Horizontal steps correspond to a fast enrichment by massive stars during starbursts and vertical steps to an increase in the DGR between starbursts cause by either dust input from AGB stars or dust growth in the ISM. When the ISM dust growth saturates, the DGR increases more smoothly with Z approaching a linear relation, because most existing metals are locked up in dust and accretion of freshly produced metals by starburst does not significantly change the DGR value. Deviations of the DGR from this linear dependence in saturation regime, the most pronounced in Model 3 (Fig. 3b), are caused by efficient dust destruction during bursts. Loops in DGR vs. Z plot present in Model 3 near Z = 0.001 and Z ≳ 0.02 stem from alternated operations of dust growth in the ISM during quiescent phases and efficient dust destruction during starbursts. Such intense dust destruction is intrinsic to evolved galaxy models with low gas fraction, and is not expected for metal-poor gas-rich galaxies.

Critical metallicities for dust growth in the ISM

Figures 2b and 3b reveal that the transition from stardust- to ISM growth-dominated dust

production occurs at very different times and metallicities: at instants

t = 200 Myr in Model 3, t = 600 Myr in Model 2, and

only t = 2 Gyr in Model 1 corresponding to metallicities of

3 × 10-3, 1.6 × 10-3, and 9 × 10-4. Such differences

can be understood from analysis of the accretion timescale variations with time and

metallicity (Figs. 2a and 3a). For silicates, the value of  is very

similar for three models for a given metallicity, while the time needed for the ISM to get

enriched to this metallicity is the longest for Model 1 and the shortest for Model 3.

Thus, metals can accrete on grains during a significantly longer period until metallicity

is changed to a higher value in Model 1 compared to Model 3. As a result, the value of the

dust-to-gas ratio due to the dust growth in the ISM for a given Z value

is higher in galaxies with slower enrichment than in galaxies with more rapid enrichment.

is very

similar for three models for a given metallicity, while the time needed for the ISM to get

enriched to this metallicity is the longest for Model 1 and the shortest for Model 3.

Thus, metals can accrete on grains during a significantly longer period until metallicity

is changed to a higher value in Model 1 compared to Model 3. As a result, the value of the

dust-to-gas ratio due to the dust growth in the ISM for a given Z value

is higher in galaxies with slower enrichment than in galaxies with more rapid enrichment.

|

Fig. 4 Mass fractions of dust grown in the ISM (solid lines), dust from AGB stars (short dashed), type II SN (dot dashed), and total stardust (AGB+SNII, long-dashed) relatively to the total dust mass. Top, middle, and bottom panels show results for Models 1–3, correspondingly (Table 1). |

4.2. Roles of stellar sources

Variations in the dust mass fraction from AGB stars, type II SNe, and ISM relative to the total dust mass in Models 1–3 are shown as a function of the oxygen abundance in Fig. 4. AGB stars and SNe II play various roles in dust production for the same values of metallicities in considered models. At metallicities below the critical metallicity in Model 1, dust input is mostly dominated by AGB stars, while type II SNe are only important during the first starburst and briefly during the second (Fig. 4, top). In Models 2 and 3, the dust growth in the ISM overtakes the dust production before the moment, when the dust input from AGB stars exceeds dust input from SN II, and AGB stars never become the dominant dust sources.

Thus, AGB stars formed during starbursts become important dust factories if the accretion timescale remains longer than the effective timescale of the matter cycle between dense and diffuse gas for sufficiently long periods comparable to the lifetimes of low- and intermediate-mass stars. This can be the case in metal-poor late-type galaxies, which host underlying old stellar populations with ages of ≳1 Gyr (Tolstoy et al. 2009; Kunth & Östlin 2000).

4.3. Comparison with observations

4.3.1. Observational data

The relation between the dust-to-gas ratio and metallicity derived from observations provides a valuable test for models of dust evolution. The dust-to-gas ratio in dwarf galaxies has been studied observationally in many works over the past decades (e.g., Lisenfeld & Ferrara 1998; Walter et al. 2007; Grossi et al. 2010; James et al. 2002; Hunt et al. 2005; Fisher et al. 2013; Galametz et al. 2011; Engelbracht et al. 2008). Dust masses are usually estimated from dust emission at far-IR and/or submillimetre wavelengths. The total gas mass is calculated by adding atomic and molecular hydrogen gas masses and correcting afterwards for contributions of He and heavier elements. Mass of H i gas can be directly calculated from the intensity of the 21 cm line. The H2 mass is estimated indirectly from CO emission, which is coupled with intrinsic difficulties in low-metallicity systems (12 + log (O/H) ≲ 8.0) owing to extremely faint CO emission and uncertainties in the CO-to-H2 mass conversion (e.g., Schruba et al. 2012). Detection of dust emission is also limited by sensitivity at low metallicity (Madden et al. 2013, and references therein).

Recently, the high sensitivity of the Herschel Space Observatory has significantly improved the accuracy of DGR measurements in metal-poor dwarf galaxies and allowed to access undetected dust emission in systems within the Dwarf Galaxy Survey (DGS; Madden et al. 2013; Rémy-Ruyer et al. 2013). In the present work, we compare our models with the most recent determinations of the DGR based on the DGS sample derived by Rémy-Ruyer et al. (2014). They collected both IR and submm data from various instruments and fitted them with the dust SED model from Galliano et al. (2011) to determine the dust masses. For gas mass estimates, they compiled data from the literature with a correction for more extended H i distribution compared to the aperture that probed dust in dwarf galaxies and for undetected molecular gas.

|

Fig. 5 Variations in the dust-to-gas mass ratio with oxygen abundance for model dwarf galaxies (Table 1). Different symbols show the values derived from observations (Rémy-Ruyer et al. 2014). The grey line shows a linear relation between the DGR and O abundance derived for the solar neighbourhood. |

4.3.2. ISM growth vs. enhanced dust input from type II SNe

As discussed above, our models of dust evolution in dwarf galaxies show that dust growth in the ISM can play an important role in these objects. In these calculations, we assume relatively low efficiencies of dust condensation in type II SNe. Recent far-IR and submillimetre observations revealed, for the first time, higher masses of newly-formed dust in SN ejecta (Matsuura et al. 2011; Gomez et al. 2012; Lakicevic et al. 2011). While it is still unclear what fraction of freshly condensed dust in SN ejecta will survive the passage of reverse shock, the observed relation between DGR and metallicity can provide a test for the dominant mechanism for dust formation.

To check whether the observed variations in the DGR with metallicity can be explained without dust growth in the ISM simply by enhanced dust input from SNe II, we perform model calculations with condensation degrees of 0.5, which is much higher than the values used in the reference models described in Sect. 2.2. Results of the DGR evolution with oxygen abundance for Models 1 to 7 for the standard dust model and enhanced SN II dust production without the ISM growth are shown in Figs. 5 and 6, respectively. In both figures the model predictions are compared with the DGR values for galaxies from DGS derived by Rémy-Ruyer et al. (2014). Figure 5 also shows the DGR values calculated by Rémy-Ruyer et al. (2014) for the KINGFISH sample, which includes metal-rich galaxies (spiral, early-type, and a few irregular galaxies), for comparison.

The standard models with low condensation efficiencies in type II SNe and dust growth in the ISM reproduce the observed relation between DGR and O abundance well, from the lowest values up to 12 + log (O/H) ~ 8.4 (Fig. 5). The locations of the most metal- and dust-poor galaxies on the DGR–O plot coincide with early evolution epochs of model galaxies, when dust input is dominated by stellar sources. The most metal-poor galaxy, I Zw 18, lies slightly below the model predictions. One of possible reasons for this is the non-zero metallicity of the infalling material, resulting in somewhat lower DGR values at low metallicities than in the standard models, which will be discussed in Sect. 4.5.1. A large dispersion in the observed values of the DGR for 7.2 < 12 + log (O/H) < 8.5 can be explained by the increasing importance of dust growth by accretion in the ISM, which occurs at various critical times and metallicities depending on the SFH. For example, the most metal-poor galaxies (12 + log (O/H) < 7.5) with higher values of the DGR are described by Models 1, 5, and 7 characterised by slow chemical enrichment. They can be much older (≳1 Gyr) than galaxies with the DGR values of a few 10-6. Dust-deficient galaxies with 12 + log (O/H) ≳ 8 are best described by Model 6, with a short τSF and shorter time intervals between bursts (300 Myr) compared to other models. Model 3 with the same value of τSF and longer starburst/post-starburst durations results in an extremely fast chemical enrichment, which occurs faster than the dust growth in the ISM. Therefore, the DGR values predicted by this model are lower than values determined from observations. This model is only included for illustration purpose. At higher metallicities, our models reproduce the general trend, but cannot explain the values above the line corresponding to complete condensation, in particular for KINGFISH galaxies. These high (supersolar) values of the dust-to-metals ratio are difficult to reconcile with the present dust model, and it is beyond the scope of this paper.

|

Fig. 6 Same as in Fig. 5, but calculated with the enhanced dust input from type II SNe without dust growth in the ISM. |

In models with enhanced dust input from type II SNe and no dust growth in the ISM, the predicted DGR at low metallicities is an order of magnitude higher than the values determined from observations (Fig. 6). Moreover, the resulting slope is very similar for different models and shallower than the trend of observational data. In contrast to AGB stars, dust production in type II SN only weakly depends on metallicity. Thus, to reproduce the observed variations of the DGR–O relation without dust growth in the ISM, very high condensation efficiencies in SNe are required by the high-metallicity part of the diagram, and a very efficient mechanism of dust removal/destruction is required to describe the low-metallicity part. It is unlikely that more than 99% of grains from SN II are destroyed in starbursts at low metallicities, but they survive starbursts almost intact at higher Z. Thus, the observed DGR–O relation is best reproduced by models with a low net production by SNe type II, and an additional increase in the dust mass in the ISM.

The main difference between dust production dominated by type II SNe and ISM growth is that the latter increases dust content between the bursts, while type II SNe produce dust (and raise the DGR) only during the star-formation bursts. Grossi et al. (2010) have investigated the DGR in dwarf galaxies, which are forming stars less actively than typical BCDs, and found that it is about ten times higher than the DGR values in galaxies with active star formation. For example, the value of the DGR of 3−6 × 10-4 in the dwarf irregular galaxy NGC 1569 is indeed much lower than in the more quiescent galaxies studied by Grossi et al. (2010).

|

Fig. 7 Time variations of carbon-to-silicate dust mass ratio in model galaxies with different star formation histories. |

4.4. Carbon-to-silicate dust mass ratio

With our current assumptions for stardust input, the dust mixture from both type SNe and AGB stars is dominated by carbon-rich dust. Therefore, in early epochs, the carbon-to-silicate dust ratio is characterised by much higher values compared to the present-day value of 0.52 predicted for the solar neighbourhood (Dwek 2005). Since the ISM chemistry is O-rich, transition to the dust production by the ISM growth is marked by a strong variation in the carbon-to-silicate dust ratio in the ISM (Fig. 7). The ratio decreases from about 100 to ~0.5–1, when the ISM growth starts to dominate the dust production. This drastic change in the carbon-to-silicate ratio predicted by our model can be used as an indicator of the transition to the dust production by growth in the ISM. However, since the efficiency of dust condensation in SN type II is still debated, and SN may produce larger amounts of silicate grains than assumed in the present work, the initial ratio of carbon-to-silicate dust can be lower.

|

Fig. 8 Same as in Fig. 5, but calculated with galaxy formation by pre-enriched infall with the metallicity Z = 10-4 and SN II like element ratios. |

4.5. Dependence on galaxy parameters

4.5.1. Infall abundance

We performed model calculations for the same set of models (Table 1), but instead of primordial infall, we assumed that model galaxies are formed by infall of pre-enriched gas with Z = 10-4 (1/140 Z⊙) and element ratios as in SN II ejecta (Bekki & Tsujimoto 2012; Tsujimoto et al. 2010). Infalling gas was assumed to be dust-free. The resulting variations in the DGR with oxygen abundance are presented in Fig. 8, together with values from observations obtained by Rémy-Ruyer et al. (2014).

As expected, the difference between the pre-enriched and reference models shown in Fig. 5 appears only at low O abundances comparable to the value of 12 + log (O/H) = 6.8 in the infalling gas. Pre-enriched dust-free infall results in a steep drop in the DGR for 12 + log (O/H) ≲ 7.2, in contrast to a much flatter evolution in the models with primordial initial abundances. At later times, the impact of pre-enriched infall manifests in a shift in the DGR in Models 1 and 5 by about 0.1 dex towards higher O abundances relative to the reference models. Since dust-forming elements are initially available in the ISM, these model galaxies are enriched faster, resulting in higher critical metallicities. Thus, the DGR values are lower than in the reference models, for the same metallicities, until dust growth by accretion reaches saturation in both sets of models (Sect. 4). Metallicity in Models 6 and 3 with fast chemical enrichment rapidly exceeds the initial metallicity of the infall, therefore the DGR evolution in these models is hardly affected by the infall abundances.

It seems that a steep decrease and small scatter in the DGR at low metallicities predicted by models with pre-enriched infall reproduces the observational data better, in particular, the DGR values in two most metal-poor galaxies, I Zw 18, and SBS0335-052, derived by Rémy-Ruyer et al. (2014) (Fig. 8). However, it is hard to make the final conclusion that the observational data favour non-zero infall metallicity because of a small number of objects observed at these extremely low metallicities.

4.5.2. Galactic wind

We performed calculations of dust evolution for model galaxies listed in Table 1 with selective galactic winds, which preferentially

remove ejecta from type II and Ia SNe with the corresponding fractions

and

and

. Although some fraction of

the ambient ISM is entangled by galactic outflows and removed from the galaxy, dynamical

models show that it is relatively low (e.g., Mac Low

& Ferrara 1999). We can thus assume that only SN ejecta are expelled

from the galaxy. In this case, the effect of winds on total gas mass and SFH in galaxies

is negligible. It means that the SN rate and dust destruction timescales have the same

values as in the reference models. Dust production by type II SNe is hardly affected by

selective winds, since nucleosynthesis yields for SNe II weakly depend on metallicity.

The dust mixture from AGB stars is more sensitive to metallicity (e.g., Ferrarotti & Gail 2006). A decrease in the

ISM metallicity leads to an increase in carbon-to-silicate dust mass ratio in stellar

outflows from AGB stellar populations, although these changes will probably not be

evident at low metallicities, at which AGB stars are the dominant dust source (Sect.

4.2). Also dust growth in the ISM strongly

depends on metallicity as explained in Sect. 4. In

fact, the effect of the galactic winds on the DGR evolution due to the dust growth in

the ISM is opposite to that of the pre-enriched infall discussed above.

. Although some fraction of

the ambient ISM is entangled by galactic outflows and removed from the galaxy, dynamical

models show that it is relatively low (e.g., Mac Low

& Ferrara 1999). We can thus assume that only SN ejecta are expelled

from the galaxy. In this case, the effect of winds on total gas mass and SFH in galaxies

is negligible. It means that the SN rate and dust destruction timescales have the same

values as in the reference models. Dust production by type II SNe is hardly affected by

selective winds, since nucleosynthesis yields for SNe II weakly depend on metallicity.

The dust mixture from AGB stars is more sensitive to metallicity (e.g., Ferrarotti & Gail 2006). A decrease in the

ISM metallicity leads to an increase in carbon-to-silicate dust mass ratio in stellar

outflows from AGB stellar populations, although these changes will probably not be

evident at low metallicities, at which AGB stars are the dominant dust source (Sect.

4.2). Also dust growth in the ISM strongly

depends on metallicity as explained in Sect. 4. In

fact, the effect of the galactic winds on the DGR evolution due to the dust growth in

the ISM is opposite to that of the pre-enriched infall discussed above.

Figure 9 shows the predicted evolution of the DGR with O abundance for model galaxies with selective galactic winds. The differences with the reference models (Fig. 5) indeed become apparent with operation of the dust growth in the ISM, which happens at later times and lower metallicities in models with galactic winds. For example, in Models 1 and 7, the dust growth by accretion raises the DGR values by an order of magnitude at 12 + log (O/H) ~ 7, which is 0.2 dex lower than in the reference models (Sect. 4). Similar differences are present in other models with more intense star formation.

|

Fig. 9 Same as in Fig. 5, but calculated with selective galactic winds expelling 30% and 60% of SN II and SN Ia ejecta, respectively. |

4.5.3. Molecular gas content

Dust production rate by the ISM growth in our model depends on the molecular gas mass fraction Xcl through the effective growth timescale given by Eq. (6). Model calculations considered so far were performed with the fixed Xcl value of 0.1. We investigate how the variations in the dense gas fraction affect the dust growth in the ISM in model runs with the variable Xcl with the values of 0.1 and 0.5 during starbursts and a reduced cloud fraction Xcl = 0.01 during quiescent phases. Figure 10 shows the DGR evolution with oxygen abundance for Model 1 with variable Xcl compared to the reference model (Table 1).

In calculations with Xcl value of 0.1 during starbursts, dependence on Xcl becomes apparent after the third burst of star formation, when the dust growth becomes an important dust source. A reduced cloud fraction during the post-burst evolution leads to a slower dust mass growth and lower DGR values compared to the reference model. However, the stepwise behaviour of the DGR indicates the importance of the dust growth during quiescent epochs, even when dense clouds constitute only 1% by mass. When the dust growth process reaches saturation at ≳7.8, the DGR evolution does not depend on the dense cloud fraction, and both models predict similar DGR values. As expected, for a higher Xcl value of 0.5, saturation of the dust growth occurs earlier (Fig. 10). This is because the effective growth timescale during the fourth burst is comparable to a burst duration enabling a quick accretion of metals produced by massive stars formed in the same burst. In these calculations we neglect the delay introduced by cooling and mixing of hot supernova ejecta with dense gas before freshly synthesised metals can accrete onto grain surfaces. Hydrodynamical simulations of a gas rich dwarf galaxy with short starbursts showed that the mixing timescale of SN II ejecta with ambient gas can be very short, a few Myr (Recchi et al. 2001). A more realistic value is probably a few hundred Myr (e.g., Yang & Krumholz 2012; Recchi & Hensler 2013), which is shorter than the quiescent periods assumed here.

|

Fig. 10 Evolution of the dust-to-gas mass ratio with oxygen abundance for Models 1 and 6 with the fixed Xcl = 0.1 (solid red and blue lines, respectively), and varying Xcl values during burst and quiescent epochs, of 0.1 and 0.01 (dashed lines of the same colors as the reference models) and 0.5 and 0.01 (dotted lines), respectively. |

For comparison, we also show the same calculations for Model 6, which has more frequent and more intense starbursts during the first Gyr of evolution (Fig. 10). Dependence on the Xcl becomes evident before the third burst (12 + log (O/H) ~ 8.1) in the scatter of the DGR values. Afterwards, efficient dust growth by accretion takes place even during the starburst in the model with Xcl = 0.5. Similar to various runs for Model 1, the DGR values calculated with various Xcl for Model 6 converge towards the linear dust-to-metal scaling, but this happens after the fourth starburst at evolution time t ≳ 1 Gyr and 12 + log (O/H) = 8.4. Thus, variations in the molecular gas fraction in dwarf galaxies introduce additional scatter in the DGR values and affect both the critical metallicity for the dust growth and the metallicity, at which dust growth reaches saturation.

5. Conclusions

We studied the dust content of late-type dwarf galaxies with episodic star formation with a multicomponent model of dust evolution. Our main result is that the growth of dust by accretion in the ISM can be important in dwarf galaxies, in contrast to early studies which considered only dust input from type II SNe. This leads to several consequences for dust evolution: (i) the dust-to-gas ratio in young dwarf galaxies is determined by the dust input from stars characterised by much lower values than predicted by the linear dust-to-metal scaling; (ii) with the ISM dust growth, the dust-to-gas ratio increases between starbursts, while SNe II enrich the ISM with grains during starbursts; (iii) critical metallicities for the dust growth in dwarfs are lower than in galaxies that continuously form stars because of long quiescent phases allowing accretion of existing metals after enrichment episodes.

The timescale of dust growth in the ISM is always limited by the accretion timescales, and thus by the amount of metals produced by a starburst. In metal-poor galaxies with slow enrichment, the dust growth in the ISM starts to dominate on a timescale of ~1 Gyr, which is shorter than the ages of the old stellar populations found in many BCD galaxies. This timescale is comparable to the ages of AGB stars, therefore they are able to become the major dust sources in metal-poor galaxies with long quiescent epochs, before the growth in the ISM takes over dust production.

Our models are able to reproduce the relation between the dust-to-gas ratio and oxygen abundance derived for a large dwarf galaxy sample from recent observations. A decrease in the DGR at low metallicities is explained by the dust input dominated by stars (SN II and AGB stars) characterised by the relatively low efficiencies of dust condensation. Scatter in the dust-to-gas ratio observed at higher metallicities 7.2 < log (O/H) + 12 < 8.5 stems from the fact that transition from the stardust- to the ISM-growth-dominated dust production happens at very different metallicities, depending on the star formation history. In galaxies with short bursts of star formation, accretion of metals on grains takes place mostly during quiescent phases of star formation, thereby steadily increasing the DGR for the same value of metallicity. Additionally, scatter in the dust-to-gas ratio is enhanced by the dust destruction during starbursts, resulting in temporal decreases in the DGR values. Variations in the dense cloud fraction expected in dwarf galaxies with episodic star formation also lead to a larger scatter in DGR–O relation. Galactic winds, which are commonly invoked to explain the low metallicities of dwarf galaxies, lead to the higher DGR values compared to the models without winds.

Calculations with increased efficiencies of dust condensation in type II SNe without dust growth by accretion in the ISM can reproduce neither the slope nor the scatter in the observed DGR versus metallicity relation. We conclude that the relation between dust content and metallicity in dwarf galaxies favours low condensation efficiencies in type II SNe, together with a gradual increase in the total dust mass by means of dust growth in the ISM.

Acknowledgments

I acknowledge support by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft through SPP 1573: “Physics of the Interstellar Medium”. I thank Simone Recchi and Thomas Henning for stimulating discussions and careful reading of the manuscript. I thank the GPU Cluster Milky Way at the FZ Juelich for computational resources. Finally, I am grateful to the referee, Gustavo Lanfranchi, for his useful comments and suggestions, which helped to improve the manuscript.

References

- Asano, R. S., Takeuchi, T. T., Hirashita, H., & Inoue, A. K. 2013, Earth, Planets and Space, 65, 213 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow, M. J. 1978, MNRAS, 183, 367 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bekki, K., & Tsujimoto, T. 2012, ApJ, 761, 180 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, S., & Schneider, R. 2007, MNRAS, 378, 973 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bradamante, F., Matteucci, F., & D’ercole, A. 1998, A&A, 337, 338 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Calura, F., Lanfranchi, G. A., & Matteucci, F. 2008a, A&A, 484, 107 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Calura, F., Pipino, A., & Matteucci, F. 2008b, A&A, 479, 669 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Cherchneff, I., & Dwek, E. 2009, ApJ, 703, 642 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cherchneff, I., & Dwek, E. 2010, ApJ, 713, 1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Draine, B. T. 2009, in Cosmic Dust – Near And Far, eds. T. Henning, E. Grün, & A. Steinacker, ASP Conf. Ser., 414, 453 [Google Scholar]

- Draine, B. T., & Salpeter, E. E. 1979, ApJ, 231, 438 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Draine, B. T., Dale, D. A., Bendo, G., et al. 2007, ApJ, 663, 866 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dwek, E. 1998, ApJ, 501, 643 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dwek, E. 2005, in AIP Conf. Proc., eds. C. Popescu, & R. Tuffs, 761, 103 [Google Scholar]

- Dwek, E., & Scalo, J. M. 1980, ApJ, 239, 193 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Engelbracht, C. W., Rieke, G. H., Gordon, K. D., et al. 2008, ApJ, 678, 804 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ercolano, B., Barlow, M. J., & Sugerman, B. E. K. 2007, MNRAS, 375, 753 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrarotti, A. S., & Gail, H.-P. 2006, A&A, 447, 553 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, D. B., Bolatto, A. D., Herrera-Camus, R., et al. 2013, Nature, submitted [Google Scholar]

- Fox, O. D., Chevalier, R. A., Dwek, E., et al. 2010, ApJ, 725, 1768 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Galametz, M., Madden, S. C., Galliano, F., et al. 2011, A&A, 532, A56 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Galliano, F., Madden, S. C., Jones, A. P., Wilson, C. D., & Bernard, J.-P. 2005, A&A, 434, 867 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Galliano, F., Hony, S., Bernard, J.-P., et al. 2011, A&A, 536, A88 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, H. L., Krause, O., Barlow, M. J., et al. 2012, ApJ, 760, 96 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Grossi, M., Hunt, L. K., Madden, S., et al. 2010, A&A, 518, L52 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Camus, R., Fisher, D. B., Bolatto, A. D., et al. 2012, ApJ, 752, 112 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Hirashita, H. 1999, ApJ, 522, 220 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hirashita, H., Hunt, L., & Ferrara, A. 2002a, MNRAS, 330, L19 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Hirashita, H., Tajiri, Y. Y., & Kamaya, H. 2002b, A&A, 388, 439 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, L., Bianchi, S., & Maiolino, R. 2005, A&A, 434, 849 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Izotov, Y. I., & Thuan, T. X. 1999, ApJ, 511, 639 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Izotov, Y. I., Lipovetsky, V. A., Chaffee, F. H., et al. 1997, ApJ, 476, 698 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- James, A., Dunne, L., Eales, S., & Edmunds, M. G. 2002, MNRAS, 335, 753 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, E. B. 2009, ApJ, 700, 1299 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A. P., & Nuth, J. A. 2011, A&A, 530, A44 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A. P., Tielens, A. G. G. M., Hollenbach, D. J., & McKee, C. F. 1994, ApJ, 433, 797 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, A., Tielens, A., & Hollenbach, D. 1996, ApJ, 469, 740 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kozasa, T., Nozawa, T., Tominaga, N., et al. 2009, Cosmic Dust – Near And Far, ASP Conf. Ser., 414, 43 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Krasnokutski, S. A., Rouillé, G., Jäger, C., et al. 2013, ApJ, 782, 15 [Google Scholar]

- Kunth, D., & Östlin, G. 2000, A&ARv, 10, 1 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, T.-M., & Hirashita, H. 2012, MNRAS, 424, L34 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lakicevic, M., Van Loon, J. T., Patat, F., Staveley-Smith, L., & Zanardo, G. 2011, A&A, 532, L8 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Lanfranchi, G. A., & Matteucci, F. 2003, MNRAS, 345, 71 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Leroy, A., Bolatto, A. D., Simon, J. D., & Blitz, L. 2005, ApJ, 625, 763 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Leroy, A. K., Bolatto, A., Bot, C., et al. 2009, ApJ, 702, 352 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Lisenfeld, U., & Ferrara, A. 1998, ApJ, 496, 145 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mac Low, M.-M., & Ferrara, A. 1999, ApJ, 513, 142 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Madden, S. C., Rémy-Ruyer, A., Galametz, M., et al. 2013, PASP, 125, 600 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Martín-Manjón, M. L., Mollá, M., Díaz, A. I., & Terlevich, R. 2011, MNRAS, 420, 1294 [Google Scholar]

- Mathis, J. S., Rumpl, W., & Nordsieck, K. H. 1977, ApJ, 217, 425 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuura, M., Barlow, M. J., Zijlstra, A. A., et al. 2009, MNRAS, 396, 918 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuura, M., Dwek, E., Meixner, M., et al. 2011, Science, 333, 1258 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- McKee, C. 1989, Interstellar Dust: IAU Symp. (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers), 135, 431 [Google Scholar]

- McQuinn, K. B. W., Skillman, E. D., Dalcanton, J. J., et al. 2012, ApJ, 751, 127 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Melioli, C., & de Gouveia Dal Pino, E. M. 2004, A&A, 424, 817 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Nozawa, T., & Fukugita, M. 2013, ApJ, 770, 27 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Recchi, S. 2013, Advances in Astronomy, submitted [arXiv:1310.4932] [Google Scholar]

- Recchi, S., & Hensler, G. 2013, A&A, 551, A41 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Recchi, S., Matteucci, F., & D’Ercole, A. 2001, MNRAS, 322, 800 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Recchi, S., Matteucci, F., D’ercole, A., & Tosi, M. 2002, A&A, 384, 799 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Recchi, S., Matteucci, F., D’ercole, A., & Tosi, M. 2004, A&A, 426, 37 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Rémy-Ruyer, A., Madden, S., Galliano, F., et al. 2013, A&A, 557, A95 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Rémy-Ruyer, A., Madden, S. C., Galliano, F., et al. 2014, A&A, in press, DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201322803 [Google Scholar]

- Romano, D., Tosi, M., & Matteucci, F. 2006, MNRAS, 365, 759 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [MathSciNet] [Google Scholar]

- Schruba, A., Leroy, A. K., Walter, F., et al. 2012, A&A, 143, 138 [Google Scholar]

- Searle, L., Sargent, W. L. W., & Bagnuolo, W. G. 1973, ApJ, 179, 427 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tolstoy, E., Hill, V., & Tosi, M. 2009, ARA&A, 47, 371 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujimoto, T., Bland-Hawthorn, J., & Freeman, K. C. 2010, Publ. Astron. Soc. Japan, 62, 447 [Google Scholar]

- Walter, F., Cannon, J. M., Roussel, H., et al. 2007, ApJ, 661, 102 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Weingartner, J., & Draine, B. 1999, ApJ, 517, 292 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.-C., & Krumholz, M. 2012, ApJ, 758, 48 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Yin, J., Matteucci, F., & Vladilo, G. 2011, A&A, 531, A136 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Zhukovska, S. 2008, Ph.D. Thesis, Ruperto-Carola-Univesity, Heidelberg, Germany [Google Scholar]

- Zhukovska, S., & Gail, H.-P. 2009, ASP Conf. Ser., 414, 199 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Zhukovska, S., & Henning, T. 2013, A&A, 555, A99 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Zhukovska, S., Gail, H.-P., & Trieloff, M. 2008, A&A, 479, 453 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

All Tables

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Time evolution of oxygen abundance for different dwarf galaxy models (Table 1). Depending on the star formation history, the same value of O abundance can be reached at very different instants. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 a) Time evolution of accretion time scales for silicate and carbonaceous grains (thin and thick lines) for Models 1–3 (solid, long-dashed and short-dashed lines, respectively). b) Dust-to-gas mass ratio (DGR) evolution with time from the onset of galaxy formation for Models 1–3 shown with the same line types as in the top panel. Thick and thin lines show the total DGR and the DGR calculated with only the ISM-grown dust. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 Same as in Fig. 2 as a function of metallicity. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 4 Mass fractions of dust grown in the ISM (solid lines), dust from AGB stars (short dashed), type II SN (dot dashed), and total stardust (AGB+SNII, long-dashed) relatively to the total dust mass. Top, middle, and bottom panels show results for Models 1–3, correspondingly (Table 1). |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 5 Variations in the dust-to-gas mass ratio with oxygen abundance for model dwarf galaxies (Table 1). Different symbols show the values derived from observations (Rémy-Ruyer et al. 2014). The grey line shows a linear relation between the DGR and O abundance derived for the solar neighbourhood. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 6 Same as in Fig. 5, but calculated with the enhanced dust input from type II SNe without dust growth in the ISM. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 7 Time variations of carbon-to-silicate dust mass ratio in model galaxies with different star formation histories. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 8 Same as in Fig. 5, but calculated with galaxy formation by pre-enriched infall with the metallicity Z = 10-4 and SN II like element ratios. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 9 Same as in Fig. 5, but calculated with selective galactic winds expelling 30% and 60% of SN II and SN Ia ejecta, respectively. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 10 Evolution of the dust-to-gas mass ratio with oxygen abundance for Models 1 and 6 with the fixed Xcl = 0.1 (solid red and blue lines, respectively), and varying Xcl values during burst and quiescent epochs, of 0.1 and 0.01 (dashed lines of the same colors as the reference models) and 0.5 and 0.01 (dotted lines), respectively. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.