| Issue |

A&A

Volume 558, October 2013

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A65 | |

| Number of page(s) | 5 | |

| Section | Planets and planetary systems | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201322337 | |

| Published online | 03 October 2013 | |

Research Note

Probing the effect of gravitational microlensing on the measurements of the Rossiter-McLaughlin effect

1 Centro de Astrofísica, Universidade do Porto, Rua das Estrelas, 4150-762 Porto, Portugal

e-mail: moshagh@astro.up.pt

2 Departamento de Física e Astronomia, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade do Porto, Rua do Campo Alegre, 4169-007 Porto, Portugal

3 Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, University of Chicago, 5640 South Ellis Avenue, Chicago, IL 60637, USA

4 Institute for Astronomy and NASA Astrobiology Institute, University of Hawaii-Manoa, 2680 Woodlawn Drive, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA

5 Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics, Department of Computational Physics, University of Tuebingen, 72076 Tuebingen, Germany

Received: 22 July 2013

Accepted: 26 August 2013

In general, in the studies of transit light-curves and the Rossiter-McLaughlin (RM) effect, the contribution of the planet’s gravitational microlensing is neglected. Theoretical studies, have, however shown that the planet’s microlensing can affect the transit light-curve and in some extreme cases cause the transit depth to vanish. In this paper, we present the results of our quantitative analysis of the contribution of microlensing on the RM effect. Results indicate that for massive planets in long-period orbits, the planet’s microlensing will have considerable contributions to the star’s RV measurements. We present the details of our study, and discuss our analysis and results.

Key words: planetary systems / techniques: spectroscopic / gravitational lensing: micro / methods: numerical

© ESO, 2013

1. Introduction

In a transiting planetary system, aside from decreasing the flux of the light received from the star, the transiting planet may focus a portion of the light that has been blocked by the planet, through the microlensing effect (Einstein 1936). In general, in studies of transit light-curves, the contribution of the planet’s gravitational microlensing is neglected. However, it has been shown that in systems with massive or long-period planets, the microlensing amplification of the stellar flux could be significant, and in the era of high precision photometric observations such as those with the Kepler, it could also be detectable (Sahu & Gilliland 2003; Agol 2003). Using an analytical approach, Sahu & Gilliland (2003) have shown that in some extreme cases, the contribution of the light from the gravitational microlensing may be even so large that the transit light-curve can vanish. This implies that in order to properly analyze the light-curve of a transiting system and derive its planetary parameters, the microlensing effect has to also be taken into account (Muirhead et al. 2013).

|

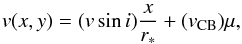

Fig. 1 Top: schematic configuration of the gravitational microlensing. Bottom: schematic view of the coordinate system used in this study. The origin of the (x,y) coordinate system is at the center of the stellar disk. The quantity rp denotes the planet radius, and r∗ is the radius of the star. |

One important characteristic of a transiting system that can be affected by planet microlensing is the Rossiter-McLaughlin effect. As a star rotates around its rotational axis, a given point on its surface will be blue-shifted when the star rotates toward the observer and red-shifted when it rotates away. During a transit, the corresponding rotational velocity of the portion of the stellar disk that is blocked by the planet is removed from the integration of the velocity over the entire star creating an anomaly in the Radial Velocity (RV) measurements of the star known as the Rossiter-McLaughlin (RM) effect (Rossiter 1924; McLaughlin 1924). This effect has been used to constrain the projected rotational velocity of a star (vsini), and the angle between the sky-projections of the stellar spin axis and the planetary orbital plane (λ) (e.g., Hébrard et al. 2008; Winn et al. 2009, 2010; Simpson et al. 2010; Hirano et al. 2011; Albrecht et al. 2012). It is important to note that the determination of vsini and λ can be influenced by second order effects such as the convective blueshift (Shporer & Brown 2011), the differential stellar rotation (Albrecht et al. 2012), and the macro-turbulence (Hirano et al. 2011).

Since the physics and geometry behind the RM effect is due to the transiting planet, they are expected to be affected by microlensing in the same way. Probing the significance of the effect of microlensing on the measurements obtained from the RM effect, and quantifying its influence is the main objective of this paper. In Sect. 2, we describe the formalism for the microlensing effect and introduce our theoretical model. In Sect. 3, we show the results of our simulations and discuss the significance of the effect of microlensing and its detectability. In Sect. 4, we conclude our study and present its future applications.

2. Model

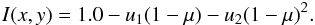

We consider a transiting planetary system and assume that the star is an extended source. The surface brightness of the star is considered to follow a quadratic limb darkening law given by  (1)In Eq. (1),

(1)In Eq. (1), ![\hbox{$\mu= \cos\theta=[1-(x^{2}+y^{2})r_{\ast}^{-2}]^{1/2}$}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/10/aa22337-13/aa22337-13-eq8.png) , and u1 and u2 are the stellar quadratic limb-darkening coefficients. We consider u1 = 0.3 and u2 = 0.35, similar to their values for the star HD 209458 in the wavelength range of 582–638 nm (Brown et al. 2001). We also assume that the lens (transiting planet) is an extended object, has zero brightness, and is spherically symmetric. We set the ratio of the planet’s radius to that of the star (rp/r∗) to 0.1, which is similar to the ratio of the radius of Jupiter or a brown dwarf to that of the Sun. The planet is assumed to be on a circular, edge-on orbit. Because the maximum RM effect occurs when the planet orbit is aligned with the stellar rotation axis, we consider the misalignment angle to be zero (λ = 0). We show the distance between the observer and the lens plane by DL, between the observer and the source plane by DS, and between the lens plane and the source plane by DLS (Fig. 1). Using these quantities, the radius of Einstein ring can be written as (Sahu & Gilliland 2003)

, and u1 and u2 are the stellar quadratic limb-darkening coefficients. We consider u1 = 0.3 and u2 = 0.35, similar to their values for the star HD 209458 in the wavelength range of 582–638 nm (Brown et al. 2001). We also assume that the lens (transiting planet) is an extended object, has zero brightness, and is spherically symmetric. We set the ratio of the planet’s radius to that of the star (rp/r∗) to 0.1, which is similar to the ratio of the radius of Jupiter or a brown dwarf to that of the Sun. The planet is assumed to be on a circular, edge-on orbit. Because the maximum RM effect occurs when the planet orbit is aligned with the stellar rotation axis, we consider the misalignment angle to be zero (λ = 0). We show the distance between the observer and the lens plane by DL, between the observer and the source plane by DS, and between the lens plane and the source plane by DLS (Fig. 1). Using these quantities, the radius of Einstein ring can be written as (Sahu & Gilliland 2003) ![\begin{eqnarray} R_{\rm E}=\Biggl[{\frac{4GM_{\rm L}D}{c^{2}}}\Biggr]^{1/2} , \,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\, D=\frac{D_{\rm LS}D_{\rm L}}{D_{\rm S}}\simeq D_{\rm LS}, \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/10/aa22337-13/aa22337-13-eq18.png) (2)where ML is the mass of the lens (planet), c is the speed of light, G is the gravitational constant, and we have considered DL ~ DS. As an example, the Einstein ring radius of a Jupiter-mass planet at 1 AU from a star is ~0.0013 RSun. For an Earth-like planet at 1 AU, this value becomes ~7.4 × 10-5 RSun.

(2)where ML is the mass of the lens (planet), c is the speed of light, G is the gravitational constant, and we have considered DL ~ DS. As an example, the Einstein ring radius of a Jupiter-mass planet at 1 AU from a star is ~0.0013 RSun. For an Earth-like planet at 1 AU, this value becomes ~7.4 × 10-5 RSun.

In a system similar to that described above, the distance between a point on the stellar disk and the projection of the center of the lens (planet) on the disk of the star can be written as ![\begin{eqnarray} d=\Bigl[(x-x_{\rm p})^{2}+(y-y_{\rm p})^{2}\Bigr]^{1/2}. \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/10/aa22337-13/aa22337-13-eq26.png) (3)The lens produces two images of the point (x,y) along the line connecting this point to the center of the projection of the planet on the star’s disk. These images are at distances

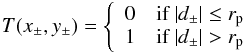

(3)The lens produces two images of the point (x,y) along the line connecting this point to the center of the projection of the planet on the star’s disk. These images are at distances ![\begin{eqnarray} d_{\pm}=0.5 \left[d\pm\left(d^{2}+4R_{\rm E}^{2}\right)^{1/2}\right] \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/10/aa22337-13/aa22337-13-eq28.png) (4)from the point of the projection of the center of the lens (planet) on the stellar disk, and are visible when they are not occulted by the planet (i.e., | d± | > rp) (Sahu & Gilliland 2003). We, therefore, define a transmission function T(x,y) as

(4)from the point of the projection of the center of the lens (planet) on the stellar disk, and are visible when they are not occulted by the planet (i.e., | d± | > rp) (Sahu & Gilliland 2003). We, therefore, define a transmission function T(x,y) as  (5)to determine when the effect of the lensed-images have to be taken into account. The amplification caused by these images is given by (Sahu & Gilliland 2003)

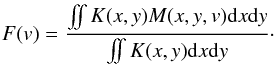

(5)to determine when the effect of the lensed-images have to be taken into account. The amplification caused by these images is given by (Sahu & Gilliland 2003) ![\begin{eqnarray} A_{\pm}(d)=\frac{1}{2}(1+2\,{\delta^{-2}}) \, \left[1+4\,{\delta^{-2}}\right]^{-1/2}\pm 0.5. \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/10/aa22337-13/aa22337-13-eq32.png) (6)where δ = d/RE. In order to incorporate the effect of microlensing in the RV measurements (obtained from the RM effect) the profile of the cross-correlation function (CCF) has to be calculated over the full stellar disk, using the integral

(6)where δ = d/RE. In order to incorporate the effect of microlensing in the RV measurements (obtained from the RM effect) the profile of the cross-correlation function (CCF) has to be calculated over the full stellar disk, using the integral  (7)In this equation,

(7)In this equation, ![\begin{eqnarray} \nonumber K(x,y) & = & \Big[A_{+}(x,y)\,T(x_{+},y_{+}) \left. \right.\\ && \left. + \, A_{-}(x,y)\, T(x_{-},y_{-})\Big] I(x,y), \right. \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/10/aa22337-13/aa22337-13-eq35.png) (8)is the modified stellar surface intensity, and

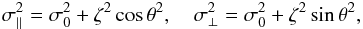

(8)is the modified stellar surface intensity, and ![\begin{eqnarray} \nonumber M(x,y,v) = \frac{1}{2\sqrt{\pi}} \!\!\! \!\! &&\left\{ \frac{1}{\sigma_{\parallel}}\, {\rm Exp}\Biggl[{-\left(\frac{v-v(x,y)}{\sigma_{\parallel}}\right)^{2}}\Biggl] \right.\\ && \left. +\frac{1}{\sigma_{\perp}}\, {\rm Exp}\Biggl[{-\left(\frac{v-v(x,y)}{\sigma_{\perp}}\right)^{2}}\Biggl] \right\}, \end{eqnarray}](/articles/aa/full_html/2013/10/aa22337-13/aa22337-13-eq36.png) (9)is the velocity profile associated with each point (x,y) due to both the stellar rotation and macro-turbulence (Gray 2005). The quantities σ∥ and σ⊥ in Eq. (9) are given by

(9)is the velocity profile associated with each point (x,y) due to both the stellar rotation and macro-turbulence (Gray 2005). The quantities σ∥ and σ⊥ in Eq. (9) are given by  (10)where ζ is the macro-turbulence velocity and is considered to have a value of ζ = 3.98 km s-1, equal to that of the Sun (Valenti & Fischer 2005). The quantity σ0 is the instrumental broadening which is set to approximately 2.2 km s-1. This is equivalent to the broadening of a typical spectrograph with a high-resolution of R ~ 110 000 similar to that of HARPS. The velocity v(x,y) in Eq. (9) is defined as

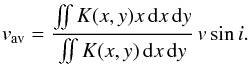

(10)where ζ is the macro-turbulence velocity and is considered to have a value of ζ = 3.98 km s-1, equal to that of the Sun (Valenti & Fischer 2005). The quantity σ0 is the instrumental broadening which is set to approximately 2.2 km s-1. This is equivalent to the broadening of a typical spectrograph with a high-resolution of R ~ 110 000 similar to that of HARPS. The velocity v(x,y) in Eq. (9) is defined as  (11)where vCB is the convective blue-shift and is set to –300 m s-1, similar to its value for the Sun (Shporer & Brown 2011).

(11)where vCB is the convective blue-shift and is set to –300 m s-1, similar to its value for the Sun (Shporer & Brown 2011).

|

Fig. 2 Top: graphs of the RM effect with and without the contribution of the planet’s microlensing. Note that the two curves are almost overlaying each other. To remove the effect of microlensing, we assume RE = 0. Bottom: graphs of residuals between the two curves shown in the top panel. The residuals demonstrate the net behavior of microlensing as a function of the planet’s position along the stellar radius. The maximum value of the of microlensing appears at 0.55 stellar radii. |

3. Calculations and results

We considered a rotating star with vsini = 10 km s-1 and a planet with a mass of 10 MJup. We set the value of DLS to 1 AU and let the position of the projection of the planet on the (x,y) plane vary from the outside of the disk of the star (1.2 r∗) to its center.

We used a grid of 4000 × 4000 cells on the (x,y) plane and calculated the integral of Eq. (7). By fitting a Gaussian function to F(v), we determined the center of CCF which corresponds to the value of RV that takes into account the combined contributions from the RM and microlensing effects. To determine the sole effect of microlensing on the value of RM, we carried out similar calculations considering the Einstein ring radius to be zero (RE = 0). By subtracting the results from the results of the previous calculations, we determined the net contribution of the microlensing effect. Figure 2 shows the results. The bottom panel of this figure shows the difference between the results of the two calculations and the contribution of microlensing effect to the RV measurements. As shown here, microlensing has its maximum contribution when the projection of the planet on the stellar disk is at a distance of 0.55 stellar radius from the center of the star. Because we are interested in the maximum effect of microlensing, in the rest of this study, we hold the position of the planet’s projection at (xp,yp) = (0.55 r∗,0).

To better understand the effects of different parameters on the results, we carried out calculations for different values of the mass and orbital separation of the planet. The mass of the planet was taken to be 0.1, 0.5, 1, 10, and 50 MJup with its lowest value corresponding to the mass of a Neptune-like object and its largest value being interpreted as the mass of a brown-dwarf. The orbital separation (DLS) was varied from 0.25 AU to 3 AU in steps of 0.25 AU. We considered the rotational velocity of the host star to be vsini = 2, 5, and 10 km s-1 (McNally 1965). We also considered three detection limits for RV measurements: 50 cm s-1 for current facilities such as HARPS, 10 cm s-1 for observational facilities in the near future such as ESPRESSO at VLT (Pepe et al. 2010), and 2 cm s-1 for instruments farther in the future such as HIRES at E-ELT. As shown in Fig. 3, when obtained from all the current and future observational facilities, the microlensing amplification will have significant contribution to the RM measurements of a massive planet in a long-period orbit (a > 2 AU). For instance, in the case of a 10 Jupiter-mass planet in a 2 AU orbit around a star with vsini = 10 km s-1, the microlensing effect is about 1 m s-1 which is comparable to the effect of macro-turbulence and convective blue-shift on RM measurements (~3 − 4 m s-1) (Albrecht et al. 2012). In the case of a massive planet on relatively short-period orbit (<1 AU), the results depend on the rate of the rotation of the star. If the star is fast rotating, the microlensing effect will be significant, otherwise for slow rotating stars, this effect will be at the detection limit of future facilities such as HIRES at E-ELT. We note that because the amplitude of the signal associated with the microlensing effect on RM measurements for a planet with a mass of 0.1 MJup and for all values of its orbital separations are smaller than 0.001 m s-1, we excluded these cases from the figure.

|

Fig. 3 Maximum contribution of microlensing to the measurements of the RM effect for different combination of planet mass and the position of the projection of the planet on the disk of the star. From top to bottom, the stellar rotational velocity is equal to 2, 5, and 10 km s-1, respectively. The detection limit of HARPS, ESPRESSO at VLT and HIRES at E-ELT are also shown for comparison. |

We also probed the impact of the microlensing on the measured values of the misalignment angle (λ), and the stellar rotation velocity (vsini) obtained from the measurements of the RM effect. Our results indicated that the misalignment angle will not be affected by microlensing. This is an expected result since the measurements of the misalignment angle are sensitive to the asymmetry of the RM signal, and the microlensing effect does not disturb the symmetry of this signal.

We would like to emphasize that in cases where the effect of microlensing is not negligible, both the light-curve of the star and the RM signal have to be modeled taking this effect into account. In such systems, when fitting the light-curve, ignoring the microlensing magnification will result in a planetary model in which the radius of the planet is smaller than its actual value. Despite such a discrepancy in the modeled radius of the planet, the vsini obtained from fitting the RM signal is only weakly affected. We note that in systems where the effect of microlensing is included in fitting the light-curve (Sahu & Gilliland 2003), this effect must also be included in the modeling of the RM signal, otherwise the value of vsini will be underestimated.

4. Analytical analysis

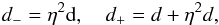

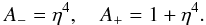

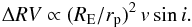

Using the formalism presented by Ohta et al. (2005), we have been able to derive an analytical formula that can roughly reproduce the results of our simulations. As shown by these authors, the averaged value of the radial velocity of the star is given by  (12)To use Eq. (12) to determine the variation in the radial velocity (i.e., Δ RV) due to the microlensing effect, we recall that the microlensing effect depends only on the value of the Einstein ring radius RE. This quantity appears in the definition of d± and A±. Taylor expanding these quantities in terms of η = RE/d, one can show that

(12)To use Eq. (12) to determine the variation in the radial velocity (i.e., Δ RV) due to the microlensing effect, we recall that the microlensing effect depends only on the value of the Einstein ring radius RE. This quantity appears in the definition of d± and A±. Taylor expanding these quantities in terms of η = RE/d, one can show that  (13)and

(13)and  (14)Equations (13) and (14) indicate that to the second order in RE, A− = 0 and A+ = 1, implying that to this order of approximation, the image at d− has no contribution to either the light-curve or the RM effect. To the lowest order in RE, the microlensing effect simply increases the fraction of the stellar disk that is seen by the observer. In fact, for all points located behind the planet and at distances between rp(1 − η2) and rp from the center of the projection of the planet on the stellar disk, d+ > rp implying that to the lowest order, the effect of microlensing is equivalent to reducing the value of the planet radius from rp to

(14)Equations (13) and (14) indicate that to the second order in RE, A− = 0 and A+ = 1, implying that to this order of approximation, the image at d− has no contribution to either the light-curve or the RM effect. To the lowest order in RE, the microlensing effect simply increases the fraction of the stellar disk that is seen by the observer. In fact, for all points located behind the planet and at distances between rp(1 − η2) and rp from the center of the projection of the planet on the stellar disk, d+ > rp implying that to the lowest order, the effect of microlensing is equivalent to reducing the value of the planet radius from rp to  . Using Eq. (12), one then obtains

. Using Eq. (12), one then obtains  (15)The coefficient of proportionality in Eq. (15) can be determined using the results of our numerical experiment. The change in the radial velocity is, therefore, given by

(15)The coefficient of proportionality in Eq. (15) can be determined using the results of our numerical experiment. The change in the radial velocity is, therefore, given by  (16)

(16)

5. Discussion and conclusion

In this study, we explored and quantified the contribution of gravitational microlensing to the measurements of the radial velocity during the transit of a planet (RM effect). We showed that the amplification of the RV signal due to the microlensing effect depends strongly on the mass of the planet and its orbital separation. Results indicated that the effect of microlensing is also significant for massive planets on long-period orbits, and is detectable with the current observational facilities. Our results showed that microlensing does not disturb the measurements of the misalignment angle caused by the RM effect. If when fitting the light-curve, this effect is taken into account, it should also be considered in the modeling of the RM signal, otherwise the value of vsini will be underestimated up to several percent for extreme cases. We note that in such cases, the underestimation of the rotational velocity will be within the observational error, and thus undetectable.

Most of the current RM surveys have been carried out on transiting systems that host planets in short period orbits. To better constrain models of planet formation, studies of the RM effect have to also include massive planets in long periods. As those planets orbit mostly fast-rotating stars [exoplanets.org], the contribution of microlensing to the measurements of their RM effect will become considerable, and detectable with future observational facilities such as ESPRESSO at VLT and HIRES at E-ELT.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank R. Alonso for useful discussions. We acknowledge the support from the European Research Council/European Community under the FP7 through Starting Grant agreement number 239953, and by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) in the form of grants reference SFRH/BD/51981/2012. NCS also acknowledges the support from FCT through program Ciência 2007 funded by FCT/MCTES (Portugal) and POPH/FSE (EC). N.H. acknowledges support from the NAI under Cooperative Agreement NNA09DA77 at the Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii, HST grant HST-GO-12548.06-A, and Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. N.H. is also thankful to the Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics/Department of Computational Physics at the University of Tuebingen, Germany for their kind hospitality during the course of this project. Support for program HST-GO-12548.06-A was provided by NASA through a grant from the Space Telescope Science Institute, which is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Incorporated, under NASA contract NAS5-26555.

References

- Agol, E. 2003, ApJ, 594, 449 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht, S., Winn, J. N., Johnson, J. A., et al. 2012, ApJ, 757, 18 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T. M., Charbonneau, D., Gilliland, R. L., Noyes, R. W., & Burrows, A. 2001, ApJ, 552, 699 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Einstein, A. 1936, Science, 84, 506 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray, D. F. 2005, The Observation and Analysis of Stellar Photospheres (Cambridge: Univeristy Press) [Google Scholar]

- Hébrard, G., Bouchy, F., Pont, F., et al. 2008, A&A, 488, 763 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [EDP Sciences] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano, T., Suto, Y., Winn, J. N., et al. 2011, ApJ, 742, 69 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, D. B. 1924, ApJ, 60, 22 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- McNally, D. 1965, The Observatory, 85, 166 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Muirhead, P. S., Vanderburg, A., Shporer, A., et al. 2013, ApJ, 767, 111 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta, Y., Taruya, A., & Suto, Y. 2005, ApJ, 622, 1118 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe, F. A., Cristiani, S., Rebolo Lopez, R., et al. 2010, in SPIE Conf. Ser., 7735 [Google Scholar]

- Rossiter, R. A. 1924, ApJ, 60, 15 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu, K. C., & Gilliland, R. L. 2003, ApJ, 584, 1042 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Shporer, A., & Brown, T. 2011, ApJ, 733, 30 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, E. K., Pollacco, D., Hébrard, G., et al. 2010, MNRAS, 405, 1867 [NASA ADS] [Google Scholar]

- Valenti, J. A., & Fischer, D. A. 2005, ApJS, 159, 141 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [MathSciNet] [Google Scholar]

- Winn, J. N., Johnson, J. A., Fabrycky, D., et al. 2009, ApJ, 700, 302 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Winn, J. N., Johnson, J. A., Howard, A. W., et al. 2010, ApJ, 723, L223 [NASA ADS] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

All Figures

|

Fig. 1 Top: schematic configuration of the gravitational microlensing. Bottom: schematic view of the coordinate system used in this study. The origin of the (x,y) coordinate system is at the center of the stellar disk. The quantity rp denotes the planet radius, and r∗ is the radius of the star. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 2 Top: graphs of the RM effect with and without the contribution of the planet’s microlensing. Note that the two curves are almost overlaying each other. To remove the effect of microlensing, we assume RE = 0. Bottom: graphs of residuals between the two curves shown in the top panel. The residuals demonstrate the net behavior of microlensing as a function of the planet’s position along the stellar radius. The maximum value of the of microlensing appears at 0.55 stellar radii. |

| In the text | |

|

Fig. 3 Maximum contribution of microlensing to the measurements of the RM effect for different combination of planet mass and the position of the projection of the planet on the disk of the star. From top to bottom, the stellar rotational velocity is equal to 2, 5, and 10 km s-1, respectively. The detection limit of HARPS, ESPRESSO at VLT and HIRES at E-ELT are also shown for comparison. |

| In the text | |

Current usage metrics show cumulative count of Article Views (full-text article views including HTML views, PDF and ePub downloads, according to the available data) and Abstracts Views on Vision4Press platform.

Data correspond to usage on the plateform after 2015. The current usage metrics is available 48-96 hours after online publication and is updated daily on week days.

Initial download of the metrics may take a while.