| Issue |

A&A

Volume 555, July 2013

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Article Number | A57 | |

| Number of page(s) | 17 | |

| Section | Interstellar and circumstellar matter | |

| DOI | https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201321547 | |

| Published online | 01 July 2013 | |

Mass and motion of globulettes in the Rosette Nebula⋆,⋆⋆

1

Stockholm Observatory, AlbaNova University Centre, Stockholm

University, 10691

Stockholm, Sweden

e-mail:

gahm@astro.su.se

2

Chalmers University of Technology, Department of Earth and Space

Sciences, Onsala Space Observatory, 43992

Onsala,

Sweden

3

Department of Physics, PO Box 64, 00014 University of Helsinki,

Finland

4

Finnish Centre for Astronomy with ESO (FINCA), University of

Turku, Väisäläntie

20, 21500

Piikkiö,

Finland

Received:

22

March

2013

Accepted:

30

April

2013

Context. Tiny molecular clumps are abundant in many H ii regions surrounding newborn stellar clusters. In optical images these so-called globulettes appear as dark patches against the background of bright nebulosity. The majority of the globulettes were found to be of planetary mass in a previous optical investigation, while the largest objects may contain more than half a solar mass.

Aims. We aim to clarify the physical nature of globulettes by deriving densities and masses, and to determine their velocities as a function of position over the nebula. This information will provide clues to the question of origins, evolution, and fate of globulettes. The Rosette Nebula is relatively rich in globulettes, and we selected a sample of well-confined objects of different sizes for the present investigation.

Methods. Radio observations were made of molecular line emission from 16

globulettes combined with near-infrared (NIR) broad-band

JHKs and narrow-band Paschen

β and H2 imaging. Ten objects, for which we collected

information from several transitions in  and

and

, were modelled

using a spherically symmetric model.

, were modelled

using a spherically symmetric model.

Results. Practically all globulettes were detected in our CO survey. The

observed  (3–2) and (2–1)

line temperatures range from 0.6 K to 6 K, the

(3–2) and (2–1)

line temperatures range from 0.6 K to 6 K, the  being a third of

this. As a rule, the lines are narrow, ~1.0 km s-1. The best fit to observed

line ratios and intensities was obtained by assuming a model composed of a cool and dense

centre and warm and dense surface layer. This model provides estimates of maximum and

minimum mass; the average masses range from about 50 to 500 Jupiter masses, which is

similar to earlier estimates based on extinction measures. The selected globulettes are

dense, nH ~ 104 cm-3, with very thin

layers of fluorescent H2 emission, showing that the gas is in molecular form

just below the surface. The NIR data show that several globulettes are very opaque and

contain dense cores. No infrared-excess stars in the fields are associated with

globulettes. Internal gas motions are weak, but some larger objects show velocity-shifted

components associated with tails. However, most globulettes show no signs of tails or

pronounced bright rims in contradiction to current numerical simulations of clumps exposed

to intense stellar radiation. Because of the high density encountered already at the

surface, the rims become thin, as evidenced by our Pβ images, which also

show extended emission that most likely comes from the backside of the globulettes. We

conclude that the entire complex of shells, elephant trunks, and globulettes in the

northern part of the nebula is expanding with nearly the same velocity of ~22

km s-1, and with a very small spread in velocity among the globulettes. We

note that the velocities observed for background shells do not fit into a spherically

expanding nebular complex.

being a third of

this. As a rule, the lines are narrow, ~1.0 km s-1. The best fit to observed

line ratios and intensities was obtained by assuming a model composed of a cool and dense

centre and warm and dense surface layer. This model provides estimates of maximum and

minimum mass; the average masses range from about 50 to 500 Jupiter masses, which is

similar to earlier estimates based on extinction measures. The selected globulettes are

dense, nH ~ 104 cm-3, with very thin

layers of fluorescent H2 emission, showing that the gas is in molecular form

just below the surface. The NIR data show that several globulettes are very opaque and

contain dense cores. No infrared-excess stars in the fields are associated with

globulettes. Internal gas motions are weak, but some larger objects show velocity-shifted

components associated with tails. However, most globulettes show no signs of tails or

pronounced bright rims in contradiction to current numerical simulations of clumps exposed

to intense stellar radiation. Because of the high density encountered already at the

surface, the rims become thin, as evidenced by our Pβ images, which also

show extended emission that most likely comes from the backside of the globulettes. We

conclude that the entire complex of shells, elephant trunks, and globulettes in the

northern part of the nebula is expanding with nearly the same velocity of ~22

km s-1, and with a very small spread in velocity among the globulettes. We

note that the velocities observed for background shells do not fit into a spherically

expanding nebular complex.

Conclusions. Some globulettes are in the process of detaching from elephant trunks and shells, while other more isolated objects must have detached long ago and are lagging behind in the general expansion of the molecular shell. Several globulettes are presently subject to heavy erosion from the intense radiation field from the central stars and eject gas streams (tails), while other quite isolated objects lack such signatures. We envision that after detachment, the objects erode to isolated and dense clumps. The suggestion that some globulettes might collapse to form planetary-mass objects or brown dwarfs is strengthened by our finding of dense cores in several objects. Such free-floating low-mass objects would move at high speed from the start and escape from the region.

Key words: HII regions / ISM: molecules / ISM: kinematics and dynamics / evolution / ISM: individual objects: Rosette Nebula

Based on observations collected at Onsala Space Observatory, Sweden, European Southern Observatory, Chile (084.C-0299(A) and 088.C-0630(A)) and Nordic Optical Telescope, La Palma, Spain, and with the Atacama Pathfinder Experiment (APEX), Llano Chajnantor, Chile (O-088.F-9318A).

Table 2 and Appendix A are available in electronic form at http://www.aanda.org

© ESO, 2013

1. Introduction

Young stellar clusters are surrounded by expanding H ii regions as a result of light and winds from central O and B stars that act on the ambient molecular cloud. Optical images of such magnificent nebulae show a mix of bright and dark nebulosity. The dark features mark remnants of the cold molecular cloud that have been compressed into shells and accelerated away from the central cluster. They contain dust, and are seen in silhouette against the bright background coming mainly from emission lines formed in the ionized bubble. Remarkable formations appear in these shells, such as elongated dusty pillars, the so-called elephant trunks that point like fingers to the central cluster.

A number of such H ii regions contain distinct, but very small clumps, as recognized early by Minkowski (1949) and Thakeray (1950). Herbig (1974) noted that many such cloudlets found in the Rosette Nebula have teardrop forms with bright rims facing the central cluster. More detailed studies followed, and several of these focused on the so-called proplyds, which are photoevaporating disks surrounding very young stars (Bally et al. 2000; Smith et al. 2003, and references therein). In these studies small cloudlets without any obvious central stellar objects were recognized as well.

Hester et al. (1996) drew the attention to some very tiny (photo-)evaporating gas globules (EGGs) in the Eagle Nebula, without any sign of embedded stars. Since then, such starless cloudlets have been searched for in more than 20 H ii regions in systematic studies in Reipurth et al. (1997; 2003), De Marco et al. (2006), Gahm et al. (2007, hereafter Paper I), and Ito et al. (2008). These studies show that the majority of these objects have radii <10 kAU with size distributions that typically peak at ~2.5 kAU. In Paper I, masses were derived from extinction measures, indicating that most objects have masses <13 MJ (Jupiter masses), which currently is taken to be the domain of planetary-mass objects. Hence, these tiny clouds form a distinct class of objects and are unrelated to the much larger globules spread in interstellar space. The objects have been given many names, but here we stick to the designation proposed in Paper I, namely globulettes, to distinguish them from globules and proplyds.

Most globulettes appear as dark, roundish patches in Hα images and show no traces of bright rims. Some objects are more elongated and even teardrop shaped. Only a small fraction of the globulettes have distinct bright rims or halos. Many objects are quite isolated and located far from molecular shells and elephant trunks in the regions. Others are seen clustering close to trunks or shells, and there are objects connected by thin filaments to the larger blocks, suggesting that globulettes may form as a consequence of erosion of these larger structures.

The fact that many globulettes are quite isolated from larger molecular blocks indicates that they can survive for quite some time in harsh environments. This is in accordance with the long survival times derived in Paper I, based on the analytic treatment of photoevaporating clumps by Mellema et al. (1998), and from more detailed 3D numerical simulations by Kuutmann (2007). In the latter study lifetimes of ~5 × 104 years were obtained for ~30 MJ objects, and the expected lifetime increases with mass. In these models, the globulettes are protected against immediate photodisintegration by an ionized bubble that expands like an umbrella in the direction of the cluster, and interacts with and removes impinging UV photons.

In the numerical simulations the objects develop bright rims from the ionized gas on the side facing the clusters. Moreover, the objects take teardrop forms, and eventually very long, dusty tails extend from the backside, in the opposite direction from the cluster. The cores are also accelerated through the interaction with light from central stars, known as the “rocket effect”. In the calculations by Kuutmann (2007) a globulette can reach terminal velocities of 5 to 10 km s-1 with respect to the initial rest frame. However, one expects that the globulettes move outwards from the start with the same velocity as the system of trunks and shells.

The outer pressure from the surrounding warm plasma and the radiation pressure contribute in confining the objects, and one expects that the initial penetrating shock, generated by photoionization, leads to compression of the interior. As discussed in Paper I, some of the larger globulettes may already have, or can develop, denser cores that collapse to form brown dwarfs, or planetary-mass objects, before evaporation has proceeded very far. Such objects initially have high velocities in the direction away from the cluster and will therefore eventually shoot out to the galactic environment like interstellar bullets.

Many low mass objects in interstellar space have been confirmed to be free-floating planetary-mass objects (Quanz et al. 2010, and references therein). From a more recent survey of sources of gravitational microlensing, Sumi et al. (2011) concluded that the total number of unbound planets in the Milky Way could be very large indeed, several hundred billions, or almost twice the number of main-sequence stars. It is usually assumed that such planets once formed in circumstellar protoplanetary disks, where perturbations led to ejection (e.g. Veras et al. 2009). Since there are binaries composed of very low-mass objects (e.g. Jayawardhana et al. 2006; Gelino et al. 2011; Burgasser et al. 2012), it is clear that isolated low-mass objects also form in situ from isolated small cloudlets. In Paper I it was suggested that globulettes in H ii regions could be an alternative source of feeding the galaxy with free-floating planetary-mass objects.

There are many questions concerning the nature and fate of globulettes, and it is desirable to collect more information on their physical state. A great puzzle is that the majority show no signs of bright rims, teardrop forms, or extended dusty tails, as predicted by the models. Inclination is obviously of importance, since elongated objects may appear round if they are oriented along the line-of-sight. As a consequence, bright rims on the remote side could escape detection since they suffer from extinction in the optical spectral region. Another question is whether some globulettes have denser cores or even host stars or planets. The masses derived in Paper I were based on column densities of dust and an assumed gas-to-dust ratio of 100. Complementary molecular line observations would provide independent mass estimates based on the gas content. Finally, it is of interest to find out how the globulettes move relative to adjacent trunks and shells, and if there is evidence that they have been accelerated due to the “rocket effect”.

We have conducted radio observations of molecular line emission and near-infrared (NIR) broad and narrow-band imaging to shed more light on the properties of globulettes. We have selected objects in the Rosette Nebula surrounding the cluster NGC 2244 from the sample in Paper I, and added some cloudlets of special interest in the same area.

Globulettes and shells observed with the Onsala 20-m antenna, APEX, and NTT.

For information on previous studies of the Rosette Nebula, including NIR surveys, see the review by Róman-Zúñiga (2008). Of particular relevance to our molecular line observations is the large-scale CO survey by Dent et al. (2009) and the maps in CO and CS of cloudlets by González-Alfonso & Cernicharo (1994). Elephant trunks in the area have been mapped by Schneps et al. (1980) and Gahm et al. (2006).

2. Observations, reductions, and objects

2.1. Observations at Onsala space observatory

The observations were carried out in April to June 2010, February to March 2011, and February 2012 using a 3-mm SIS receiver at the 20-m telescope at Onsala Space Observatory (OSO). We observed 12CO J = 1–0 at 115.271 GHz, and/or 13CO J = 1–0 at 110.201 GHz. A few objects were also observed in the HCO+J = 1–0 transition at 89.189 GHz. All globulettes and observed transitions in the respective object are listed in Table 1.

The observations were performed in the frequency-switching mode, using a 1600-channel hybrid digital autocorrelation spectrometer at 25 kHz channel spacing (Δv ~ 0.07 km s-1) and a bandwidth of 40 MHz. The single-sideband system temperature was typically around 1000–1400 K for 12CO, and 400–600 K for 13CO. The pointing was checked regularly, and we estimate the pointing error to be less than a few arcseconds. At 115 GHz, the full width at half maximum (FWHM) beam size of the 20 m-antenna is 33″, and the main beam efficiency ~0.30 (for an average elevation of approximately 30°). The chopper-wheel method was used for the intensity calibration. The data reduction was performed with the spectral line software package xs1.

To ensure that the observed signals originate in the selected globulette off-set positions, normally at 30″ or 45″ from the globulette, were also observed. Some globulettes are projected on a background of more extended molecular emission, and for these, and also for a few objects with complex line profiles, additional off-set positions were included.

2.2. APEX observations

Observations of two higher 12CO and 13CO transitions were carried out in September and November 2011 with the 12 m APEX2 telescope at Llano Chajnantor, Chile: 12CO J = (2–1) at 230.538 GHz, and J = (3–2) at 345.796 GHz, and 13CO J = (2–1) at 220.399 GHz, and J = (3–2) at 330.588 GHz. We used two single sideband heterodyne SIS-receivers mounted on the Nasmyth-A focus: APEX-1 and APEX-2. All observations were performed in position-switching mode. The FWHM is 27″ at 230 GHz, and 18″ at 345 GHz, and the corresponding main beam efficiencies are 0.75 and 0.73. The RPG eXtended bandwidth Fast Fourier Transform Spectrometer (XFFTS) has 32 768 channels and consists of two units with a fixed overlap region of 1.0 GHz and an instantaneous bandwidth of 2.5 GHz. The channel spacing is thus 76.3 kHz, and the velocity spacing Δv is 0.1 and 0.07 km s-1 at 230 and 345 GHz, respectively. The pointing was checked regularly, and the error is estimated to be within 2″. The data reduction of the APEX data was performed with CLASS, part of the GILDAS-package3, and also checked with xs.

Globulettes of different sizes were selected from the sample observed at OSO (see Table 1), and a few off-set positions were included in the APEX observations as well to confirm the OSO results.

2.3. NIR observations

Four fields containing radio-detected globulettes in the Rosette Nebula were imaged with

the Son of Isaac (SOFI) infrared spectrograph and imaging camera on the New Technology

Telescope (NTT) at the European Southern Observatory in Chile using the J

, H , and Ks broad-band filters, and the narrow filters

NB H2 S1, which covers the H2 1-0 S(1) 2.12 μm spectral line,

and NB 2.090, which covers the adjacent continuum. The observations were conducted during

four nights in December 2009 through January 2010. The SOFI field of view is 49, and its

pixel size 0 288. The

JHKs observations were carried out in

the on-off mode instead of in the standard jitter mode to retain the possible extended

surface brightness features. After each on-integration an off-position outside the Rosette

Nebula was observed, and jittering was performed after two on-off pairs. One-minute

integration time, which consisted of six individual 10-s integrations, was used in

JHKs. The observed on-source times

per filter were 26 min, except for one field (Field 19), which was observed for 13 min.

288. The

JHKs observations were carried out in

the on-off mode instead of in the standard jitter mode to retain the possible extended

surface brightness features. After each on-integration an off-position outside the Rosette

Nebula was observed, and jittering was performed after two on-off pairs. One-minute

integration time, which consisted of six individual 10-s integrations, was used in

JHKs. The observed on-source times

per filter were 26 min, except for one field (Field 19), which was observed for 13 min.

The H2 observations were obtained in the jitter mode, where the surface

brightness with a scale larger than the jitter box (30′′) is smeared and/or

cancelled in the data reduction. Only small-size features and gradients in the original

surface brightness structure were retained. Point-like sources and galaxies were

unaffected by the jittering. The fields have 40 frames of one-minute integrations obtained

using three 20- or two 30-s integrations. The average seeing during the observations was

~0 8. Because the

NB 2.090 is narrower than the NB H2 S1 filter, a 20% longer total integration was required

in this filter. In addition to the broad-band on-off observations, one SOFI field (Field

19) was observed in the jitter mode in

JsHKs. Complementary SOFI imaging of

several fields was performed in January 2012 through a narrow-band Paschen

β filter (at 1.28 μm) combined with a narrow-band

continuum filter.

8. Because the

NB 2.090 is narrower than the NB H2 S1 filter, a 20% longer total integration was required

in this filter. In addition to the broad-band on-off observations, one SOFI field (Field

19) was observed in the jitter mode in

JsHKs. Complementary SOFI imaging of

several fields was performed in January 2012 through a narrow-band Paschen

β filter (at 1.28 μm) combined with a narrow-band

continuum filter.

The IRAF4 external XDIMSUM package was used in the data reduction. The images were searched for cosmic rays, were sky-subtracted, flat-fielded, illumination-corrected, registered and averaged. For the JHKs observations the four off-position images nearest in time to each on-position image were used in the sky-subtraction. For the jittered images the two neighbouring images were used. An object mask was constructed for each off image. Applying these masks in the sky-subtraction produced hole-masks for each sky-subtracted image. Special dome flats and illumination-correction frames provided by the NTT team were used to flat-field and to illumination-correct the sky-subtracted images. Rejection masks combined from a bad-pixel mask and individual cosmic-ray and hole masks were used when averaging the registered images.

The Source Extractor software v.2.5.0 (Bertin & Arnouts 1996) was used to extract the photometry for each reduced SOFI field.

The steps to build the stellar photometry catalogues out of the SOFI magnitudes are the

same as in Mäkelä & Haikala (2013). Objects

within 30 pixels from the frame edges and objects with a Source Extractor star index less

than 0.9 in more than one band were discarded. After combining the catalogues for each

field, 1375 objects remain. The limiting magnitudes for a formal error of

0 15 are

J ≈ 21, H ≈ 20, Ks ≈ 19.5 except for

Field 19, where they are 0

15 are

J ≈ 21, H ≈ 20, Ks ≈ 19.5 except for

Field 19, where they are 0 5 brighter.

5 brighter.

2.4. Selected objects

The globulettes investigated in Paper I were identified from deep narrow-band Hα images collected with the 2.6 m Nordic Optical Telescope (NOT) on La Palma, Canary Islands, Spain. In the Rosette Nebula a total of 145 globulettes were listed. We have observed 16 of these at OSO and 10 with APEX. The objects were selected as to cover such broad a range in mass as possible, but objects with masses in the planetary domain could not be reached. Moreover, the selected objects are relatively dense in comparison with some more diffuse globulettes listed in Paper I.

|

Fig. 1 Cuts from Hα images presented in Paper I of different fields in the Rosette Nebula, including globulettes and positions in shells that were selected for the subsequent analysis, as numbered in Table 1. The fields all span 4.4′ × 3.4′, and are numbered as in Paper I. The bottom second panel is a blown-up Hα image of the dense globulette RN 88, diameter ~ 6 ″ in Field 15. The string of globulettes in Field 15 is connected to a long filamentary shell containing a claw-like feature. The upper part of the prominent elephant trunk “the Wrench” is seen southwest of “the Claw”. North is up and east is to the left. |

Another four globulettes located in areas outside the optical survey were observed at OSO; one of them was included in the APEX observations. In addition, four positions in molecular shells in regions adjacent to globulettes were observed at OSO. The NIR images contain several globulettes and trunks, and the results of this survey will be discussed in more detail in a follow-up paper. Ten of the radio-detected globulettes fall in the NIR fields – these data are considered in the present article as well.

The observed objects are listed in Table 1 and are identified according to their catalogue number in Table 2 of Paper I. Here RN denotes the Rosette Nebula. Central positions of our radio observations were also taken from Paper I. Then follow the objects added to this list, globulettes (marked A, B, etc.) for which central positions were selected from existing sky views of the Rosette Nebula, and shells (marked Shell A, B, etc.) with positions measured from NOT images. The object designated Claw E forms the eastern part of a yaw-like structure, composed of twisted and very thin filaments. The western part of the Claw was included in the CO survey by Gahm et al. (2006) of the adjacent “Wrench Trunk”, which also has an yaw-like end (Carlqvist et al. 2003).

Columns 2 and 3 in Table 1 list sources observed for 12CO and 13CO J = 1–0 at OSO. Objects mapped over a small area around the central position in selected lines are marked. The APEX observations marked in Col. 4 include all four observed lines. In Col. 5 objects that are included in the NIR fields are marked. In the the last column, objects also observed in HCO+(1 – 0) are marked. RN 40 is identical to TDR 10 as designated in González-Alfonso & Cernicharo (1994), and RN A is identical in position to the highly obscured X-ray source ACIS #86 listed by Wang et al. (2010). Among the CO-detected clumps and distinct objects in Dent et al. (2009), no 8, here referred to as D 8, is close in position to this X-ray source. From the same list, D 10 is identical to RN 5, and D 6 includes objects RN 35 and 38, not resolved in Dent et al. (2009). D 15 is identical to RN D (off-set by ~7″).

Figure 1 shows Hα images that were extracted from the fields in the NOT survey and include a number of globulettes listed in Paper I. The locations of the fields in the Rosette Nebula can be found in Fig. 1 of Paper I from the Field number. Objects observed in the present investigation are marked according to the designations in Table 1. Also shown is an enlargement of RN 88 in Field 15 as an example of a well-confined and dense isolated globulette. RN 88 appears to be completely dark in this high contrast image, but weak residual Hα emission covers the object. In Field 8, RN 39 is marked because it is included in the CO map of TDR 10 in González-Alfonso & Cernicharo (1994), where RN 40, separated by 24.5″, is the stronger source. However, RN 39 is outside our telescope beams.

Some globulettes are connected by very thin filaments to shell structures, as in Field 18, and others are quite isolated from trunks and shells, as in Field 19. Both round and elongated globulettes are represented. In Field 15 a remarkable string of globulettes extends to the east of the Claw.

The object RN A, centred at an X-ray source, is not a regular globulette. It is attached to the shell and has the form of a block with finger-like extensions. Our radio and NIR observations reveal that this region is highly complex and contains an outflow; this object will be analysed in more detail in a separate paper. RN A is therefore not included in the subsequent analysis of globulettes in the Rosette Nebula and is not displayed in Fig. 1. RN B and C are two distinct globulettes located in areas outside the NOT survey north of the inner molecular shell. RN D is seen projected on the central cavity not far from the central cluster. The locations of all these objects can be found in Fig. 2, where some NOT-included objects shown in Fig. 1 are marked. The Wrench is in the middle of the image with the yaw-like feature the Claw. The position of Shell A falls inside the RN A circle. The four NIR fields are also marked. Their central positions are 06:31:00.9 +05:07:03.6, 06:31:17.9 +05:08:05.0, 06:31:39.8 +05:11:16.1, and 06:32:20.8 +05:14:06.0, and cover areas in fields 7, 8, 15, and 19.

|

Fig. 2 Overview of part of the Rosette Nebula composed from images in Hα (red) and O iii (green). Objects not included in the NOT survey are marked, as are some NOT objects for orientation. The NIR fields are depicted as white boxes, covering from right to left Fields 7, 8, 15, and 19. The elephant trunk the Wrench is in the middle of the image with the Claw at its upper end (image: Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope). |

|

Fig. 3 13CO(1–0) emission towards RN 40 over the LSR velocity range –8 to +9 km s-1. The top panel shows a 10-sigma detection at the on-position, and the lower panel shows the non-detection at the off-position (30″, − 30″) with an rms of 45 mK. |

3. Results

3.1. Spectral line parameters

Molecular line emission was detected from all objects, with the exception of the small

globulettes RN 12 and C. All our APEX and Onsala spectra at on-source-positions of objects

detected in a least one transition are shown in the on-line Figs. A.1 and A.2. We are confident

that we can distinguish the targets from other sources, since no signal is detected at

off-positions. An example is shown in Fig. 3 with

13CO(1–0) spectra obtained for RN 40 at on- and off-position (0″, –30″). The

intensity scale in all spectra is expressed in terms of the antenna temperature reduced to

outside the atmosphere,  . Most objects

show distinct and narrow lines, ~1.0 km s-1. The line peak velocities agree

well for lines from various transitions with some exceptions. For several objects,

emission from shells in the background enters, but with velocities different from the

globulettes. At off-set positions, the globulette signal is gone while the background

emission remains.

. Most objects

show distinct and narrow lines, ~1.0 km s-1. The line peak velocities agree

well for lines from various transitions with some exceptions. For several objects,

emission from shells in the background enters, but with velocities different from the

globulettes. At off-set positions, the globulette signal is gone while the background

emission remains.

|

Fig. 4 Examples of spectra obtained with APEX (upper panels) and at OSO (lower panels) for globulettes of different size. From left to right: RN 9 (small), 114 (medium), and 129 (large). Upper panels: the 12CO(3–2), 13CO(3–2), 12CO(2–1), and 13CO(2–1) lines are plotted in black, green, red, and blue, respectively. Lines from (2–1) transitions are drawn as curves, and from (3–2) transitions as histograms. Lower panels: 12CO(1–0) profiles (thick); 13CO(1–0) profiles (green, thin). The 13CO(1–0) lines are multiplied by ten (RN 9) or three (RN 114 and 129). RN 9 is identified with the narrow component at ~0 km s-1, while the broader component at ~+2 km s-1 comes from more extended gas. In RN 129 a “blue” wing is present in several lines. |

In Table 2 (also available from CDS) we present line parameters derived for all objects and transitions. Objects with broad lines are so marked. The globulettes are normally well confined in the Hα images presented in Paper I, and size in Col. 2 refers to the area measured by us from the optical images, not including faint obscuring tails and plumes. The optically derived mass from Paper I expressed in Jupiter masses is listed in Col. 3. In Col. 9 velocities of the most prominent background components are given, to be discussed in Sect. 4.6. These components are as a rule strong and broad and at velocities very different from the globulettes. Column 10 gives the 13CO(1–0) velocity if observed, otherwise it is obtained from a 12CO line. In Col. 11 objects with complex profiles (com.) that may contain more than one component are noted (futher discussed in Sect. 4). Objects observed for HCO+ are indicated with integrated intensity in parenthesis.

For the subsequent discussion we divided the globulettes into three size groups depending on area according to Table 2: small (<80 arcsec2), medium (80–200 arcsec2), and large (>200 arcsec2). It should be kept in mind, though, that all selected globulettes are among the largest listed in Paper I. Examples of spectra obtained at several frequencies of globulettes of different size are shown in Fig. 4. RN 9 (left panels) is seen in projection against local extended emission responsible for the broader component at ~+2 km s-1. At on-position also the narrow component at ~0 km s-1 enters the spectra and is identified with the globulette. Some profiles obtained for RN 129 are asymmetric (right panels). Objects with pronounced line asymmetries are discussed in Sect. 4.5.

A general feature is that the  peak

intensity of the strongest component is the same, or nearly the same, in the

12CO(3–2; 2–1) and the 13CO(3–2; 2–1) transitions irrespective of

globulette size. This is surprising considering that the beam-filling in the

12CO(3–2) transition is higher by a factor 2.25 than (2–1). The only notable

exception to this is RN 40, with a 12CO(3–2) intensity of only 60% of that in

13CO(2–1). The

peak

intensity of the strongest component is the same, or nearly the same, in the

12CO(3–2; 2–1) and the 13CO(3–2; 2–1) transitions irrespective of

globulette size. This is surprising considering that the beam-filling in the

12CO(3–2) transition is higher by a factor 2.25 than (2–1). The only notable

exception to this is RN 40, with a 12CO(3–2) intensity of only 60% of that in

13CO(2–1). The  and

13CO(1–0) lines are usually very weak compared with lines from the higher

levels. When wing emission or a second velocity component is detected, the observed

and

13CO(1–0) lines are usually very weak compared with lines from the higher

levels. When wing emission or a second velocity component is detected, the observed

line ratios

varies over the line (Fig. A.1).

line ratios

varies over the line (Fig. A.1).

In the area containing the tiny globulettes RN 88, 91, 93, 94, and 95 two velocity components are detected. For these globulettes there is some confusion regarding which signal comes from the globulettes, and some lines are broad and shallow. Our identifications are based on the appearance of one off-set spectrum from 12CO(1–0), which is common to all objects. This region is discussed in Sect. 4.4.

3.2. SOFI results

|

Fig. 5 Jittered Js, H, and Ks images of an area in Field 19. The cores of RN 114, 122 and 129 are opaque in the Js filter. |

|

Fig. 6 Upper panels: continuum, H2 and the H2 – continuum difference images of an area in Field 15 where the Claw and the string of small-size globulettes are visible in the two latter images. Lower panels: difference images of areas in Fields 7, 8, and 15. The locations of some globulettes and one shell position are marked for orientation. |

|

Fig. 7 Left and middle panels: 1.26 μm continuum and Pβ images of an area in Field 15. The Claw at the centre is dark in the Pβ image, and so are some of the tiny globulettes to the east of the Claw. Right panel: the opaque cores of RN 114, 122, and 129 are distinct on this Pβ image of an area in Field 19 (see also Fig. 5). |

The jittered Js, H and Ks images of Field 19 are shown in Fig. 5. Most of the globulettes, including the very small ones, are visible. In the Ks images they appear as well-defined, faintly luminous bright-rimmed objects with sizes that match those seen in the NOT Hα images. In the Js image a few globulettes are seen as dark silhouettes, and several have bright rims as in the Ks images. The dark cores seen in the Js images of RN 122 and 129 (left panel), for instance, are about half the size of those measured in Hα and flag the presence of internal cores of higher density than traced in the optical survey. The jittering observing mode smooths out any extended surface brightness and furthermore, the data reduction forces the average background level to zero. Jittering may also smooth out to some extent the size and depth of areas of substantial extinction observed especially in the direction of the larger globulettes and shells and trunks. Therefore we cannot derive NIR extinctions and infer column densities of dust, as was done in the optical spectral region (Paper 1). Some globulettes are also seen in the H image, but they are less prominent than in the Js or Ks images.

The Ks filter contains several molecular hydrogen lines and the hydrogen Brackett γ line at 2.17 μm. The observed fields were therefore observed also with the narrow-band filters NB H2 S1 covering the H2 1-0 S(1) line at 2.12 μm, and NB 2.090, which covers the adjacent continuum. The difference between the two images contains only H2 emission, and all other features, including stars should vanish. The continuum, the H2, and the difference images of Field 15 are shown in the upper panels of Fig. 6. The Claw and the string of small-size globulettes is seen in the H2 image, but not in the neighbouring continuum image. The difference image demonstrates that the globulette rims emit brightly in the 2.12 μm line. Faint H2 surface emission inside the globulettes is seen as well. NTT is an alt-azimutal telescope, and therefore the stellar diffraction spikes rotate on the images depending on the time of observation, and residuals resulting from the incomplete subtraction can be seen in the difference images.

The lower panels in Fig. 6 shows continuum-subtracted H2 1–0 S(1) images in three areas located in Fields 7, 8, and 19. The incomplete elimination of stars in Field 8 was caused by the seeing, which varied between the continuum and H2 observations. The globulettes in these images have extremely thin bright rims, which are not resolved in the SOFI images. Bright rims also border trunks and other shell structures observed. A comparison of the H2 and the Ks images shows that the H2 2.12 μm line emission can explain approximately one third of the surface brightness observed in the Ks image. Most probably, the major part of the excess emission is due to line emission in other H2 lines and the Brackett γ line in the Ks filter. Results from the H2 imaging will be discussed in detail more in a separate paper.

Bright rims, though fainter than in the Ks images, are seen in the J and H images. These two filters also contain some rotational H2 lines and the hydrogen Paschen β line at 1.28 μm enters the J band. The 1.26 μm and Pβ narrow-band filter images of the area selected in Field 15 are shown in Fig. 7 (left and middle panels). In the Pβ image the Claw and the string of tiny globulettes are seen dark against the bright background, whereas in the continuum image the objects cannot be detected. This is also the case for some objects in Field 19 (right panel).

3.3. SOFI stellar photometry

The stars in the SOFI field, which covers parts of the NOT Fields 7 and 8 (Fig. 1), were divided into two to investigate the reddening in

the direction of the general background and in the direction of globulettes and shell

structures. The

(J − H)/(H − Ks)

colour–colour diagrams of stars in these directions are shown in Fig. 8. The panel to the right includes stars in the direction of globulettes

or shells, and the one to the left stars in surrounding areas. The arrows in the diagrams

indicate the effect of five magnitudes of visual extinction. The left panel shows a

grouping around the unreddened main-sequence, probably of unreddened or only slightly

reddened late-type stars. The stars below the unreddened late main-sequence are possibly

medium-mass stars. The uppermost grouping of stars in the left panel are stars in or

behind the nebula. The location of these stars indicates a reddening of

1 5 to

2

5 to

2 0 of visual

extinction.

0 of visual

extinction.

The number of substantially reddened stars is larger in the right panel. The grouping of stars around the unreddened main sequence is missing and only few stars fall below. The diamonds identify stars detected in the direction of globulettes in this field. Since these stars show no evidence of infrared excess emission, we conclude that they are reddened stars behind the globulettes, and not embedded very young objects. From our data we cannot conclude whether the background stars are dwarfs or giants, but assuming a normal interstellar reddening law, the total extinction towards these globulettes is in the range 3 < AV < 10 magnitudes.

|

Fig. 8 (J − H)/(H − Ks) colour–colour diagrams of stars from Fields 7 and 8. Stars outside the obscured region are plotted in the left panel, and those in the direction of shells and globulettes in the right panel. The stars detected inside globulettes are plotted as diamonds. Also plotted are the loci of unreddened giant (red, thick) and main-sequence (black, thin) stars. The direction of interstellar extinction follows the slashed lines and the vector shows a corresponding visual extinction of 5 mag. |

4. Discussion

Using the information derived in Sect. 3, we now proceed with a discussion of the physical properties of the globulettes and how their velocities are distributed across the nebula. Because most of the globulettes are smaller than the HPBW of APEX at all observed frequencies, all spectral line modelling must rely on the physical sizes derived from optical and NIR images. The various images tracing both continuum and line emission allow us to draw some conclusions on density and density structure. Similarly to Paper I, we adopt a distance of 1.40 kpc to the complex and a central velocity of +17 km s-1 (LSR) for the cluster and surrounding ionized gas in deriving physical quantities and estimates of mass.

The globulette leading edges, i.e. the sides facing the central cluster, are sharp both in the optical and NIR. Some of the larger globulettes have shining bright edges in the Hα line. However, if the background is bright, such rims may not be intense enough to be noticed. The southern edge of the Wrench and the edges of RN 73, 78–80, and 84 in Field 14 (see Paper I) are bright, but those of the globulettes in Field 15 (RN 88, 94 and 95) and Field 19 are not (see Fig. 1).

Globulettes with bright Hα rims also have bright rims in the J and Ks filters. The lack of bright rims in the narrow-band continuum images at 1.26 μm (Fig. 7) and 2.09 μm (Fig. 6) shows that the bright rims in the Js and Ks filters (Fig. 5) are not due to scattering but to line emission, as confirmed by the H2 and Pβ images (Figs. 6 and 7). The background in the Pβ image is high but the Claw shows a distinct limb brightening. The globulettes just east of the Claw are detected in the image, but only in absorption against the background. Either bright rims do not exist, or they are very thin or faint and escape detection.

The bright rims observed in Hα show that the density just above the globulette surface must be lower than that in the globulettes. Otherwise the optical depth at wavelengths below 1102 Å, where the H2 absorption takes place, would be high and the radiation would not penetrate deep enough to reach the surface. Interstellar extinction at 1.282 μm (Pβ line) is significantly lower than at 6557 Å (Hα). Furthermore, the H2 rims coincide with the Hα and Pβ rims, which shows that matter turns into molecular form close below the surface. As stated in Paper I, from the analysis in Grenman (2006) the distribution of material in globulettes is not Gaussian, and the density is high even close to the globulette surface and is very low outside. Another sign of high density is that especially the larger objects are seen as dark silhouettes against the Pβ background, which also applies to some of the smaller globulettes, such as RN 88, 91, 93, 94, and 95. We conclude that the globulettes are relatively dense and sharply bound objects consisting of molecular gas floating in a plasma of low density.

4.1. H2 column density and mass

Hydrogen is predominantly found in molecular form in the globulettes, therefore visual extinction scales directly with H2 gas column density, which can be estimated from the extinction to background stars in directions of globulettes. The NICER method presented in Lombardi & Alves (2001) and the SOFI NIR photometry can be used to estimate the large-scale visual extinction within areas imaged in JHKs. In Sect. 3.3 we found that the extinction in areas outside globulettes, elephant trunks, and shell features is low, generally lower than 2 mag. The extinction towards individual globulettes must be estimated individually, however.

A highly reddened star is seen in the direction of globulette RN 35 (Fig. 8). Since the spectral type is unknown, one can only

estimate upper and lower limits of the extinction. A star at the uppermost tip of the

giant branch in Fig. 8 would have a total visual

extinction of ~7 5. The

corresponding value for a star at the late unreddened main sequence or mid-giant branch is

10

5. The

corresponding value for a star at the late unreddened main sequence or mid-giant branch is

10 0.

0.

The interstellar extinction to the Rosette complex is

AV ≈ 1.4 (Ogura & Ishida 1981; Celnik 1986). Allowing for 2 5 of foreground

and also background extinction, the lower and upper estimates for RN 35 are 5 and 7 mag,

respectively. If the star is even earlier in spectral type, the upper limit could be

higher. Using the ratio of visual extinction to hydrogen column density given by Bohlin et

al. (1978), the extinction of

5

5 of foreground

and also background extinction, the lower and upper estimates for RN 35 are 5 and 7 mag,

respectively. If the star is even earlier in spectral type, the upper limit could be

higher. Using the ratio of visual extinction to hydrogen column density given by Bohlin et

al. (1978), the extinction of

5 0 translates

into an H2 column density of 4.7 × 1021 cm-2. RN 35 is

very symmetric in shape, and with a diameter of 18.6 kAU (Paper I) this column density

corresponds to an average density of 1.7 × 104 cm-3. With a mean

molecular mass per H2 molecule of 2.8 amu, the total mass can be estimated to

be 0.44 M⊙. This mass is about 2.5 times larger than the

optically derived mass in Paper I, and if the extinction amounts to

7

0 translates

into an H2 column density of 4.7 × 1021 cm-2. RN 35 is

very symmetric in shape, and with a diameter of 18.6 kAU (Paper I) this column density

corresponds to an average density of 1.7 × 104 cm-3. With a mean

molecular mass per H2 molecule of 2.8 amu, the total mass can be estimated to

be 0.44 M⊙. This mass is about 2.5 times larger than the

optically derived mass in Paper I, and if the extinction amounts to

7 5, the

difference is even larger. The extinction derived for the star behind RN 35 probes only

one direction through the cloud, however, and therefore the masses derived from the

optical and NIR images are not directly comparable.

5, the

difference is even larger. The extinction derived for the star behind RN 35 probes only

one direction through the cloud, however, and therefore the masses derived from the

optical and NIR images are not directly comparable.

4.2. Molecular line observations

The interpretation of the molecular line data is not straightforward because we have no a priori knowledge of the small-scale globulette density, temperature, and velocity structure. The size of most of the observed globulettes is smaller than the APEX HPBW at 345 GHz and no mapping is possible. However, the high signal-to-noise ratio and good velocity resolution in the APEX spectra gives an opportunity to draw conclusions about the physical structure of globulettes.

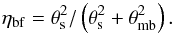

The solution of the radiative transport equation, neglecting background radiation and

with a constant source function, is  (1)where

ηmb is the main beam efficiency,

ηbf the beam-filling factor (see Eq. (3) and (4)) and

J(Tex) the radiation temperature

(1)where

ηmb is the main beam efficiency,

ηbf the beam-filling factor (see Eq. (3) and (4)) and

J(Tex) the radiation temperature

(2)where the

approximation is valid if hν ≪

kTex.

(2)where the

approximation is valid if hν ≪

kTex.

A critical value in Eq. (1) is the beam-filling factor. The optical and NIR shape of the globulettes ranges from a nearly perfect, opaque circle (RN 88, Fig. 1) to cometary-like objects with a compact head and elongated, more diffuse tail (e.g. globulettes in Field 19, Fig. 1). Besides the shape, the size also varies strongly. The cores of interstellar dark clouds and normal globules are usually surrounded by less dense, extended envelopes, but as described above, the globulettes are more compact. The beam-filling of the compact round globulettes can thus be best estimated assuming a disk with a size corresponding to the projected optical size of the globulette.

The beam-filling factor of a disk of diameter θD, a constant

brightness temperature distribution over the disk and observed with a Gaussian beam with a

half-width at half-maximum of θmb is  (3)The beam-filling

factors of symmetric, round globulettes can be estimated using the disk beam-filling

factor. For elongated globulettes this is a combination of the disk filling factor (the

leading edge) and the filling factor for a Gaussian distribution (the tail). The

beam-filling factor, ηbf, assuming that both the source

brightness distribution and the antenna response are circularly symmetric and Gaussian

with a half width of θs, is

(3)The beam-filling

factors of symmetric, round globulettes can be estimated using the disk beam-filling

factor. For elongated globulettes this is a combination of the disk filling factor (the

leading edge) and the filling factor for a Gaussian distribution (the tail). The

beam-filling factor, ηbf, assuming that both the source

brightness distribution and the antenna response are circularly symmetric and Gaussian

with a half width of θs, is  (4)The Onsala and APEX

beams at the

(4)The Onsala and APEX

beams at the  frequencies (115,

230 and 345 GHz) are 33′′, 27′′ and 18′′, respectively.

For a large-size source, filling the 345 GHz HPBW, ηbf is

0.19, 0.27 and 0.5 for a disk, and 0.23, 0.31 and 0.5 for a Gaussian distribution (Eq. (3)

and (4)). For a small-size source like RN 88 (diameter 6′′) the corresponding

values are 0.023, 0.034 and 0.075 for a disk, and 0.032, 0.047 and 0.1 for a Gaussian

distribution. For globulettes with diameters of 10′′ or less the disk

beam-filling factor is 25% smaller than for the CO(3–2) transition, and more than 30%

smaller for the (2–1) transition.

frequencies (115,

230 and 345 GHz) are 33′′, 27′′ and 18′′, respectively.

For a large-size source, filling the 345 GHz HPBW, ηbf is

0.19, 0.27 and 0.5 for a disk, and 0.23, 0.31 and 0.5 for a Gaussian distribution (Eq. (3)

and (4)). For a small-size source like RN 88 (diameter 6′′) the corresponding

values are 0.023, 0.034 and 0.075 for a disk, and 0.032, 0.047 and 0.1 for a Gaussian

distribution. For globulettes with diameters of 10′′ or less the disk

beam-filling factor is 25% smaller than for the CO(3–2) transition, and more than 30%

smaller for the (2–1) transition.

The APEX main beam efficiency at 230 GHz and 345 GHz is nearly the same (0.75 and 0.73).

Therefore, for a small size source with optically thick lines at the two frequencies the

observed  would depend

strongly on the source-filling factor. Not surprisingly, the CO signal towards small

globulettes is much weaker than towards the larger ones.

would depend

strongly on the source-filling factor. Not surprisingly, the CO signal towards small

globulettes is much weaker than towards the larger ones.

The 12CO(3–2)/13CO(3–2) and

12CO(2–1)/13CO(2–1) line ratios are approximately 1/3, irrespective

of the source size. This indicates that both the 12CO(3–2) and (2–1)

transitions are optically thick. The observed 12CO(3–2)/12CO(2–1)

and 13CO(3–2)/13CO(2–1) ratios do not depend on the source size but

are close to one with the exception of RN 40, for which the

ratio is 0.6.

ratio is 0.6.

The beam-filling factors described above assume that the source brightness temperature

has a Gaussian distribution or that the brightness temperature distribution is constant

over the visible disk and that both the  and

and

transitions probe

the same volume of gas. However, it is unlikely that either assumption is valid and other

factors have to be accounted for. In addition to the density, the CO line temperature

depends on the excitation temperature. Assuming that the surface facing the central

cluster is heated by radiation, a major part of the 12CO(3–2) emission could

come from this warmer layer, while the (2–1) emission originates mainly from the cooler

interior. The two transitions would then trace different volumes of gas, and the

beam-filling factors would be different. Such a case was indeed observed by White et al.

(1997) in a cometary globule in the southern part

of the Rosette Nebula. This type of source structure cannot be analysed using the LTE

approximation, and a radiation transfer program is needed.

transitions probe

the same volume of gas. However, it is unlikely that either assumption is valid and other

factors have to be accounted for. In addition to the density, the CO line temperature

depends on the excitation temperature. Assuming that the surface facing the central

cluster is heated by radiation, a major part of the 12CO(3–2) emission could

come from this warmer layer, while the (2–1) emission originates mainly from the cooler

interior. The two transitions would then trace different volumes of gas, and the

beam-filling factors would be different. Such a case was indeed observed by White et al.

(1997) in a cometary globule in the southern part

of the Rosette Nebula. This type of source structure cannot be analysed using the LTE

approximation, and a radiation transfer program is needed.

4.3. Globulette modelling

We have used a radiation transfer program developed by Juvela (1997). The program uses the Monte Carlo method and allows sources with arbitrary density, temperature, velocity, density structure and a value for general turbulence to be constructed. Virtual observations of this model can be made in desired molecules/transitions. A different beam size can be chosen for each transition. The program calculates the appropriate beam-filling factor for the source structure and the beam in each transition, and thus the program output corresponds to the observed spectrum corrected for atmospheric attenuation and divided by the appropriate main beam efficiency.

Test runs were made assuming a standard dense core structure with a cooler dense core

region and a warmer, less dense envelope, where the density decreases towards the edges.

The modelled  (3–2)/(2–1) line

ratios were always much higher than the observed ones. The radiation transfer program

calculates the correct beam filling factor for each line, so the bad fit is not due to the

better beam filling of the 12CO(3–2) line. Increasing the density and

temperature of the envelope did not improve the situation. However, a better match to

observed line intensities was obtained when a hot and thin dense surface layer was added

to the latter models. Different versions of this toy model were tested.

(3–2)/(2–1) line

ratios were always much higher than the observed ones. The radiation transfer program

calculates the correct beam filling factor for each line, so the bad fit is not due to the

better beam filling of the 12CO(3–2) line. Increasing the density and

temperature of the envelope did not improve the situation. However, a better match to

observed line intensities was obtained when a hot and thin dense surface layer was added

to the latter models. Different versions of this toy model were tested.

Because only unresolved single-dish globulette spectra are available most of the input parameters must be guessed at. The observed spectra are narrow, less than 1 km s-1, which strongly restricts the value for the turbulence and the internal systematic (infall) velocity field. A turbulence of 0.2 km s-1 and an infall velocity of 0.1 km s-1 were chosen as an initial guess. Higher turbulence would produce too broad lines and higher in-fall velocity would, in addition to broadening the line, also produce spectra with a strong dip at the systemic velocity. For the smaller globulettes the values for the turbulence and in-fall had to be scaled down to obtain model spectra as narrow as observed. The density/temperature values were varied to obtain spectra similar to the observed temperatures.

To obtain the high densities needed to explain the observed NIR colours of background

stars and to model the  lines, the

lines, the

emission must be

optically thick. The modelled

emission must be

optically thick. The modelled  spectra are

always strongly self-absorbed, so only lower limits for Tex

can be calculated from the observed

spectra are

always strongly self-absorbed, so only lower limits for Tex

can be calculated from the observed  . Taking into

account the APEX beam-efficiency and the beam-filling factor as well as the observed

12CO(2–1) antenna temperature of 0.6 K for RN 88, the lower limit for this

globulette would be well in excess of 15 K. For larger globulettes, such as RN 114, the

lower limit would be 20 K. However, considering the likely self-absorption, the true

Tex must be higher. This agrees with the assumption that the

globulette surface is heated by UV radiation from the central cluster. It is clear that a

range of excitation temperatures must exist within each globulette.

. Taking into

account the APEX beam-efficiency and the beam-filling factor as well as the observed

12CO(2–1) antenna temperature of 0.6 K for RN 88, the lower limit for this

globulette would be well in excess of 15 K. For larger globulettes, such as RN 114, the

lower limit would be 20 K. However, considering the likely self-absorption, the true

Tex must be higher. This agrees with the assumption that the

globulette surface is heated by UV radiation from the central cluster. It is clear that a

range of excitation temperatures must exist within each globulette.

Even though it was possible to construct models that produced line intensities and line

ratios similar to the observed  and

and

intensities and

ratios, it was not possible to do this for both isotopologues simultaneously. A model that

provides the correct

intensities and

ratios, it was not possible to do this for both isotopologues simultaneously. A model that

provides the correct  intensities

results in much too low

intensities

results in much too low  intensities, and

a model providing the correct

intensities, and

a model providing the correct  intensities fails

to explain the

intensities fails

to explain the  intensities. Two

models were constructed for each globulette observed with APEX, one giving the

intensities. Two

models were constructed for each globulette observed with APEX, one giving the

line intensities

and line ratios and another for the

line intensities

and line ratios and another for the  . The

H2 densities required to model the observed

. The

H2 densities required to model the observed

spectra are

significantly higher than those required for

spectra are

significantly higher than those required for  . The modelled

. The modelled

spectra are

strongly self-absorbed, which depends strongly on the source density and temperature

structure and the velocity field (turbulence and systematic motions).

spectra are

strongly self-absorbed, which depends strongly on the source density and temperature

structure and the velocity field (turbulence and systematic motions).

We therefore used these models to provide a plausible lower (the

model) and upper

(the

model) and upper

(the  model) limit for

the mass of each observed globulette. The adopted values for the velocity dispersion and

systematic infall are probably adequate. The line width and shape of the spectra depend

very strongly on these two parameters, and the pool of possible values is very restricted.

No model that would produce the exact, observed

model) limit for

the mass of each observed globulette. The adopted values for the velocity dispersion and

systematic infall are probably adequate. The line width and shape of the spectra depend

very strongly on these two parameters, and the pool of possible values is very restricted.

No model that would produce the exact, observed  or

or

line intensities

could be constructed, and the 12CO(3−2) line was always 10 to 15% stronger than

the (2–1) transition as were also the corresponding values for the

line intensities

could be constructed, and the 12CO(3−2) line was always 10 to 15% stronger than

the (2–1) transition as were also the corresponding values for the

transitions. For

the

transitions. For

the  this may be

explained by strong self-absorption. The upper and lower mass limits calculated from the

models should therefore be considered to be only crude estimates.

this may be

explained by strong self-absorption. The upper and lower mass limits calculated from the

models should therefore be considered to be only crude estimates.

As expected from the beam-filling argument alone, the larger the globulette, the stronger

the observed molecular lines. The line width also increases with size. The

and

and

line widths

increase from 0.9 km s-1 and 0.6 km s-1 to 1.3

km s-1 and 0.9 km s-1, respectively. The morphology changes as

well: the small-size globulettes are round and become more elongated with increasing size,

i.e. tails emerge. The leading edge remains sharp, but the tail has a more diffuse

appearance. If one assumes that the tail is formed by gas and dust flowing away from the

head, then the outflowing gas should be blue-shifted with respect to the head because of

the assumed orientation of the objects. This is indeed observed, and the more asymmetric

the shape, the more pronounced the blue-shifted wing (see Sect. 4.5).

line widths

increase from 0.9 km s-1 and 0.6 km s-1 to 1.3

km s-1 and 0.9 km s-1, respectively. The morphology changes as

well: the small-size globulettes are round and become more elongated with increasing size,

i.e. tails emerge. The leading edge remains sharp, but the tail has a more diffuse

appearance. If one assumes that the tail is formed by gas and dust flowing away from the

head, then the outflowing gas should be blue-shifted with respect to the head because of

the assumed orientation of the objects. This is indeed observed, and the more asymmetric

the shape, the more pronounced the blue-shifted wing (see Sect. 4.5).

Small-size globulettes. The physical diameters of RN 9,

88, and 95 range from 8.5 kAU (RN 88) to 14 kAU (RN 9) (Paper 1, Table 2). The maximum

H2 number densities used in the  models are around

1.1 × 104 cm-3 at the centre and 2.5 × 103

cm-3 at the compressed edge. All these globulettes are seen in absorption in

the Pβ image, which also supports the modelled high central density.

Despite this high density the masses for the three objects are low. The mass lower limits

from

models are around

1.1 × 104 cm-3 at the centre and 2.5 × 103

cm-3 at the compressed edge. All these globulettes are seen in absorption in

the Pβ image, which also supports the modelled high central density.

Despite this high density the masses for the three objects are low. The mass lower limits

from  models are 10 to

40 MJ and upper limits from

models are 10 to

40 MJ and upper limits from

models 40 to 70

MJ. The average optical masses (Table 2) range from 20 (RN 88) and 72 MJ (RN 9).

Hence, the masses derived from visual extinction and radio line data are very similar. RN

95 has a blue-shifted velocity component, but this might be because the nearby globulette

RN 94 also enters the Gaussian beams. Another two small globulettes, RN 93 and RN 122,

were detected with APEX. The line profiles of RN 93 are very broad, however, and RN 122 is

very elongated with a blue-shifted component probably related to its distinctive tail.

Neither of these objects can be modelled with the present method. Their line intensities

are similar to what is observed towards the modelled small-size globulettes, and

presumably their masses fall in the same range.

models 40 to 70

MJ. The average optical masses (Table 2) range from 20 (RN 88) and 72 MJ (RN 9).

Hence, the masses derived from visual extinction and radio line data are very similar. RN

95 has a blue-shifted velocity component, but this might be because the nearby globulette

RN 94 also enters the Gaussian beams. Another two small globulettes, RN 93 and RN 122,

were detected with APEX. The line profiles of RN 93 are very broad, however, and RN 122 is

very elongated with a blue-shifted component probably related to its distinctive tail.

Neither of these objects can be modelled with the present method. Their line intensities

are similar to what is observed towards the modelled small-size globulettes, and

presumably their masses fall in the same range.

Medium size globulettes. RN 38, 40, and 114 have diameters of 16, 17 and 22 kAU, respectively, and differ from the smaller globulettes in that they have distinctive tails in the Hα images (Fig. 1). Only the interior cores, which are round, are opaque in the Pβ images. The mass lower and upper limits derived using the spherically symmetric model are 70 and 130 MJ for RN 38 and 100 and 345 MJ for RN 114. Hence, the average masses for these objects also agree well with the values derived from optical data, namely 97 and 195 MJ.

Modelling RN 40 is problematic because the 12CO(3–2) line intensity is only 60% of the 12CO(2–1) intensity. The beam-filling factor of the 345 GHz beam for a Gaussian intensity distribution is 0.31, twice that for 230 GHz. It is impossible to construct a spherically symmetric model producing such a 12CO(3–2)/(2–1) ratio. In addition, blue-shifted wings are present (see Sect. 4.5).

RN 40 forms the head of TDR 10 observed in  and

13CO(2–1; 1–0) and CS(3–2; 2–1) by González-Alfonso & Cernicharo (1994). TDR 10 also covers RN 39 situated

25′′ NW of RN 40. Curiously, their 12CO(2–1) line integral maximum

is not observed in the head of RN 40, but in the tail just to the north. In the channel

map (Fig. 3 in their paper) 12CO(2–1) is stronger at velocities

<0.5 km s-1, i.e. on the blue-shifted side,

compared with our 13CO(3–2), (2–1) and (1–0) central velocities. The

12CO(2–1) maximum would lie at the edge of the APEX 18′′ HPBW at

245 GHz, but still in the 27′′ APEX 230 GHz and the 33′′ Onsala 115

GHz beams. If the location of the 12CO(2–1) maximum in the tail were caused by

a pointing error, correcting for such a shift would move the secondary maximum, now

coinciding with RN 39, to the south of it. Thus this pointing error is not likely.

and

13CO(2–1; 1–0) and CS(3–2; 2–1) by González-Alfonso & Cernicharo (1994). TDR 10 also covers RN 39 situated

25′′ NW of RN 40. Curiously, their 12CO(2–1) line integral maximum

is not observed in the head of RN 40, but in the tail just to the north. In the channel

map (Fig. 3 in their paper) 12CO(2–1) is stronger at velocities

<0.5 km s-1, i.e. on the blue-shifted side,

compared with our 13CO(3–2), (2–1) and (1–0) central velocities. The

12CO(2–1) maximum would lie at the edge of the APEX 18′′ HPBW at

245 GHz, but still in the 27′′ APEX 230 GHz and the 33′′ Onsala 115

GHz beams. If the location of the 12CO(2–1) maximum in the tail were caused by

a pointing error, correcting for such a shift would move the secondary maximum, now

coinciding with RN 39, to the south of it. Thus this pointing error is not likely.

The APEX observations were pointed at the RN 40 dense core, as evidenced by the

(3–2)/(2–1)

ratio. Furthermore, the velocities of all the observed

(3–2)/(2–1)

ratio. Furthermore, the velocities of all the observed

transitions

agree. The larger beams at 230 GHz, and especially at 115 GHz trace the

transitions

agree. The larger beams at 230 GHz, and especially at 115 GHz trace the

emission maximum

better than the 345 GHz beam. This brings us to the question: why the

emission maximum

better than the 345 GHz beam. This brings us to the question: why the

maximum is seen

in the RN 40 tail, which, at least in the optical Hα image, appears

diffuse and not opaque? One explanation could be that the

maximum is seen

in the RN 40 tail, which, at least in the optical Hα image, appears

diffuse and not opaque? One explanation could be that the

emission traces

warm but diffuse subthermally exited gas.

emission traces

warm but diffuse subthermally exited gas.

Large-size globulettes. Two large size-globulettes, RN 5 and 129 were

observed with APEX. Both objects are elongated, more so than the APEX HPBW at 345 GHz, and

have excess blue-shifted  emission.

Curiously, in RN 5 the central line velocities of the 12CO(3–2) and (2–1) main

line components are red-shifted compared with the

emission.

Curiously, in RN 5 the central line velocities of the 12CO(3–2) and (2–1) main

line components are red-shifted compared with the  lines. Similarly

to RN 40, the 12CO(1–0) line is broad and red-shifted compared with the higher

transitions. It is possible to obtain a tentative mass estimate for the heads of the

globulettes covered by the single-point observation, but not for the entire globulettes.

No Pβ image is available for RN 5, but in the Hα image

(Fig. 1) the head of the globulette, which possibly

contains two fragments, is most opaque. In the RN 129 Pβ image (Fig.

7) the beam covers the most obscured part of the

globulette. The upper and lower limits for the estimated masses are 368 and 788

MJ for RN 5, and 305 and 536 MJ

for RN 129. The H2 densities are similar to those needed to model the

medium-sized globulettes above, but the masses are larger because of the size. Better

beam-filling is the main reason for the higher observed antenna temperatures. The model

cannot reproduce the strong blue-shifted emission, but it it assumed that this is due to

blue-shifted gas in the more diffuse tail (Sect. 4.5). The corresponding optical masses of 665 and 691

MJ best match the maximum mass derived above, and were

derived from slightly larger areas than covered by the APEX beams.

lines. Similarly

to RN 40, the 12CO(1–0) line is broad and red-shifted compared with the higher

transitions. It is possible to obtain a tentative mass estimate for the heads of the

globulettes covered by the single-point observation, but not for the entire globulettes.

No Pβ image is available for RN 5, but in the Hα image

(Fig. 1) the head of the globulette, which possibly

contains two fragments, is most opaque. In the RN 129 Pβ image (Fig.

7) the beam covers the most obscured part of the

globulette. The upper and lower limits for the estimated masses are 368 and 788

MJ for RN 5, and 305 and 536 MJ

for RN 129. The H2 densities are similar to those needed to model the

medium-sized globulettes above, but the masses are larger because of the size. Better

beam-filling is the main reason for the higher observed antenna temperatures. The model

cannot reproduce the strong blue-shifted emission, but it it assumed that this is due to

blue-shifted gas in the more diffuse tail (Sect. 4.5). The corresponding optical masses of 665 and 691

MJ best match the maximum mass derived above, and were

derived from slightly larger areas than covered by the APEX beams.

|

Fig. 9 12CO(1–0) profile of the eastern part of the Claw, which is asymmetric, but is as a whole red-shifted relative to the western part of the Claw. A two-component Gaussian fit to the profile is also shown (details in the text). |

4.4. Global velocity pattern

The globulettes are distributed over a large area in the Rosette Nebula, spanning 1/2° (a projected distance of 13 pc) from RN 5 to RN 63. Most objects fall along the inner remnant shell, extending from west to northeast from the central cluster. As can be seen from Fig. 2, this shell forms part of a ring outside the northern part of the central cavity. The entire complex is blue-shifted relative to the centre of the Rosette complex by ~17 km s-1. (Dent et al. 2009), and with an estimated inclination to the line-of-sight to the central cluster of ~40° ± 5° (Schneps et al. 1980; Gahm et al. 2006).

The velocity pattern is remarkably smooth. The globulettes all move with similar velocities, +0.5 ± 2.1 km s-1, very close to the velocities obtained at various positions along the ring. With an inclination of 40° it follows that the system of globulettes, shells, and trunks expands at velocities of ~22 km s-1 from the central cluster. The two objects farther out from the ring, RN C and 63, have the highest positive velocities, +2.8 km s-1 and +3.4 km s-1, respectively. This is entirely consistent with an expansion velocity of 22 km s-1, since in a spherically expanding system their inclination is ≈60°. We did not consider here the geometry proposed by Dent et al. (2009), who in an attempt also to include shell structures southeast of the cluster defined an expanding molecular ring centred far south of the cluster, and inclined by ≈ 60° (or ≈30° from the sky plane). This model implies a much higher expansion velocity of ~30 km s-1. For the northwestern area, at focus of the present investigation, we note that Viner et al. (2009) obtained a line width of 22 km s-1 from the H 110α recombination line, consistent with our result. For the same area Celnik (1985) derived line widths of 15 and 31 km s-1 from the He 112α and H 112α lines, respectively.

RN D, seen in projection to the cluster, also has a comparatively large positive velocity, +2.4 km s-1, consistent with the value given in Dent et al. (2009). In this direction one expects velocities of ~–3 km s-1 for objects in the ring system. Hence, it appears that this isolated object seen against the central cavity has a different history than the ring system.

The difference in radial velocity of globulettes and adjacent shell structures rarely exceeds 2 km s-1. For example, RN 101 and 110 are moving with the most negative velocities in our sample, –2.4 km s-1 and –4.0 km s-1, but so does Shell D with –4.4 km s-1. The globulettes are connected by thin filaments to Shell D.

|

Fig. 10 13CO(1–0) spectra obtained for the tiny globulette RN 95 at on-position (above) and off-position (+30″, 0″). |

Figure 9 shows the profile obtained from the eastern part of the Claw (Claw E). A two-component Gaussian decomposition gives a narrow main component centred at +1.4 km s-1 (FWHM = 0.8 km s-1), and a weaker broader component at +0.7 km s-1 (FWHM = 2.5 km s-1). The western part of the Claw was included in the CO map of the Wrench by Gahm et al. (2006) and was found to move at ≈+0.0 km s-1. Hence, Claw E is red-shifted relative to the western part of the Claw by ~+1.2 km s-1, which shows that the Claw as a whole rotates with about the same speed and the same direction as the Wrench, which is located just south of the Claw.

RN 91, 93, 94, and 95 in the string east of the Claw (see Fig. 1) have similar velocities, ~+1.2 km s-1. RN 93 and 95 are larger than 91 and 94, respectively. Because these pairs are separated by only ≈12″, the emission from the smaller globulettes has entered the radio beams, and there is also weak extended CO-emitting gas at similar velocities in this area. However, as demonstrated from the 13CO(1–0) spectra of RN 95 in Fig. 10, there is no problem to distinguish the globulette signal, which is detected in all transitions. The isolated object RN 88, just south of the string, is slightly blue-shifted in comparison, moving at −0.3 km s-1. RN 88 is the smallest object in our survey, and the identification is tricky. However, the line ratios of the blue-shifted component are similar to the ratios observed in other globulettes, whereas the ratios in the red-shifted component are not.

4.5. Local mass motions

We now take a closer look at three objects, RN 5, 40, and 129, which show more complex line profiles, an indication that additional local gas motions are present.

|

Fig. 11 Line profiles obtained for the central position of RN 5 show a weak component, blue-shifted relative to the main component. The strongest lines are from 12CO and the weaker from 13CO. Lines from (2–1) transitions are drawn as curves, and from (3–2) transitions as histograms. |

The most prominent wing feature is observed for RN 5, and in the APEX data the

12CO(2–1) transition is strongest and the 13CO(3–2) weakest as

seen in Fig. 11. In RN 40 all

transitions have

similar intensities in the wing, while in RN 129 the two higher

transitions have

similar intensities in the wing, while in RN 129 the two higher

transitions are

of nearly the same intensity, but the (1–0) intensity is also strong. A common feature in

RN 5, 40, and 129 is that the 12CO(1–0) line is broader than that in the (3–2)

and (2–1) transitions. The velocity of the (1–0) peak intensity is also shifted towards

the wing.

transitions are